Jazz historical narratives frequently frame Benny Goodman and Chick Webb's 1937 battle of music as a mythic event, enshrining it as a moment of central symbolic importance in the history of swing music and as one of the Savoy Ballroom's most unique spectacles.Footnote 1 George T. Simon's tome of swing-era bandleader biographies The Big Bands opens its piece on Webb with a thick description of this battle. Referencing his contemporaneous writeup in Metronome, Simon writes that,

According to my report, Benny's band played first and made a great impression. Then ‘the Men of Webb came right back and blew the roof off the Savoy. The crowd screamed, yelled and whistled with delirium. From then on the Webb band led the way, and, according to most people there that night, truly topped the Goodman gang.Footnote 2

Most contemporary sources more or less reproduce this account, highlighting the special significance of the country's most popular swing band leader's defeat at the hands of Harlem's local favorite. Scott DeVeaux and Gary Giddins's textbook Jazz describes the battle as a “trouncing” and notes that Goodman's celebrated drummer Gene Krupa “bowed down in respect.”Footnote 3 Henry Martin and Keith Waters's Jazz: The First Hundred Years similarly acknowledges Webb's victories over Goodman's and Count Basie's bands, noting he was awarded these wins by his “loyal audience.”Footnote 4 Such accounts correspond with themes in the white jazz press’ writeups from 1937. Commentary in Downbeat, Metronome, and Melody Maker began by emphasizing the massive crowd assembled for the event: roughly 4,000 inside the ballroom and another 5,000 outside, and each acknowledged that Webb's band was the consensus victor.

The Webb/Goodman battle also receives extensive treatment in Ken Burns's episodic documentary Jazz. The film's treatment of the event begins with a reminiscence by Simon about the plethora of great bands and venues in New York during the late 1930s. With Webb's recording of “Stompin’ at the Savoy” playing in the background, the disembodied voice of Simon's interlocutor rattles off a string of bands and venues one could experience—all of them white and segregated, respectively—before closing with “and then, there were the ballrooms, the Roseland with Woody Herman, and the Savoy with Chick Webb.”Footnote 5 The scene shifts to Harlem where the film's narrator, Keith David, introduces Webb by tying him firmly to the Savoy Ballroom. As David explains, “The Savoy was still Harlem's hottest spot, and Chick Webb, who had been one of the first bandleaders to play swing, was still in charge.” Critic Gary Giddins then frames Webb as a “unique” figure by juxtaposing the powerful sound of his drumming with his diminutive stature and physical ailments. As the lens focuses on the battle, David announces that, “On May 11, 1937, Benny Goodman ventured uptown to challenge Webb in what was billed as the music battle of the century.”Footnote 6 As the film begins to portray the battle itself, the narrative voice switches to, at the time of filming, the two most famous living African American lindy hoppers—Frankie Manning and Norma Miller—who narrate the battle, claiming that in their opinion, Webb's band outswung Goodman's. As the pair narrate the battle's events from their perspectives, Burns recreates the battle in miniature by compressing it to a single tune, switching back and forth between Webb's and Goodman's commercial recordings of Edgar Sampson's “Don't Be That Way,” synched with alternating photos of the two bands. In the film's narrative assessment, “the Goodman band was routed,” a position it emphasizes by playing loud cheering crowd noise alongside the Webb recording.

Burns's cinematic representation highlights two critically important aspects of the event: its atmosphere of large-scale spectacle and its signifying potential in broader conversations about race and difference. However, Burns's presentation frames these aspects of the battle as exceptional when they were actually typical qualities of the “battle of music,” which was a specific presentational genre for swing music in predominantly black venues during the 1920s and 1930s. Within African American communities, battles of music re-staged ballrooms as symbolically loaded representational spaces where dueling bands regularly served as oppositional totems that indexed differences of locality (e.g., Chicago vs. New York), gender (men vs. women), ethnicity (Anglo or African American vs. Latin), or race (black vs. white). Different discursive framings and contexts featured different axes of difference or layered them to effectively form concentric circles of identity formation.Footnote 7 Accounting for the significance of this performance context, this article explores the disconnect between the Webb/Goodman battle's relatively standard use of a well-established set of performative conventions and its subsequent enshrinement as a uniquely significant event. I argue that this disconnect has occurred because of the highly specific confluence of circumstances in the mid-1930s that shaped the battle's immediate reception and its subsequent legacy: Goodman's emergence as the “King of Swing” during a new period of massive mainstream popularity for swing music, a coterminous vigilance among both white and black jazz writers to credit black artists as jazz's originators and best practitioners, and the emergence of athletes Jesse Owens and Joe Louis as popular black champions capable of symbolically conquering white supremacy at home and abroad.

“War Declared!”: Battles of Music as Representations of Difference

By the time Benny Goodman and Chick Webb battled in 1937, their contest had been underwritten by layers of signification and performance convention formed through roughly a decade of “battle of music” contests at Harlem's Savoy Ballroom and many other predominantly African American venues. Such battles had come to function as spectacles where specific spatial practices marked the events as exceptional spaces of elevated musical and rhetorical intensity.Footnote 8 Somewhat ironically, it is this very framing as unique or exceptional that united battles of music as a presentational genre; it is, ultimately, what made each of them typical within it. Battles of music were fueled by discourses of competition and difference through which bands came to symbolize styles, regions, genders, and races. This dynamic affirms Andrew Berish's broader argument that 1930s dance band music provided audiences “models of personal and national self-understanding” specifically by articulating the spatialized politics of shifting racial geographies and power structures during periods of migration and demographic change.Footnote 9 As champions for specific identities along various axes of difference, bands who battled each other rendered ballrooms representational spaces where musical conflicts spoke to broader social debates.

The concept of jazz battles can be traced to the informal contests between New Orleans combos battling in the street from carts and wagons as they advertised their evening performances, yet the specific formation of the jazz “battle of music” likely dates to the mid-1920s. Duke Ellington's band engaged in multiple battles, some of them against white bands, during its 1926 and 1927 summer tours of New England.Footnote 10 The term “battle of music” first appears in black newspapers in May 1927, almost ten years to the day before the Webb/Goodman battle, when the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem began promoting battles as part of a broader strategy to emphasize the grandiose scale of its offerings.Footnote 11 In the Savoy's first major battle of music, Webb's band and Fess Williams's Royal Flush Orchestra, another local favorite and Savoy mainstay, battled the visiting Joe “King” Oliver's band from Chicago. The battle was part of an attempt to capitalize on the Savoy management's significant financial investment in a two-week residency for Oliver's band. To mark the battle as a significant Harlem event, the Savoy billed it as a gala spectacle, emphasizing to the New York Amsterdam News that “such celebrities as Paul Whiteman, Vincent Lopez, Ted Lewis, Ray Miller, George Olsen, Ben Bernie and countless others have all signified their intention of welcoming the King of Jazz to New York on his first visit.”Footnote 12 The plan succeeded as the ballroom reportedly sold out and had to turn people away, a pattern that would repeat at subsequent events at the Savoy and elsewhere throughout the 1930s.Footnote 13

Indeed, though a central point of the Webb/Goodman battle's lore is that it sold out the ballroom and flooded the surrounding streets with thousands of fans, this level of audience interest in battles of music was certainly not without precedent. Inspired by the Savoy's model, battles held in 1929 in Baltimore's New Albert Hall drew audiences that more than doubled the building's official capacity of 2,000.Footnote 14 A 1931 Detroit battle held Christmas week between Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, and McKinney's Cotton Pickers at the city's newly constructed naval armory reportedly drew 7,100, a figure exceeding the crowd present for Webb and Goodman.Footnote 15 In 1936, north Philadelphia's Nixon Grand Theater held a battle for which the hall was reportedly “packed to overflowing.”Footnote 16 Drawing these kinds of crowds relied on an assemblage of spatial practices through which promoters, audiences, and bands enacted battle spaces as spectacular. This heightened sense of place was further bolstered by the physical extremes to which the battle format pushed both dancing and musicking participants in the space. The battle environment broke the normal ebb and flow of a ballroom setting in favor of the escalating excitement of a singular, spectacular event. Battles featured continuous dancing as bands would play sets one after the other or trade off individual songs. As such, the crowd participated in the heightened energy, pushing the outer limits of their stamina. The dialogic nature of a battle between two bands, with audience applause judging the winner, created a musical space that foregrounded communicative dynamics and necessitated active engagement.

Promoters contributed to a battle of music's sense of spectacle through decoration, promotion, and rhetoric that marked such events as representations of military space—of battles and battlefields. The Savoy's aforementioned first major battle was billed as “Jazz Warfare” between Webb, Williams, and Oliver's bands. The press and advertisements for this event employed military rhetoric to frame it as a regional contest between Chicago and New York. “War is Declared,” claimed an advertisement in the New York Amsterdam News, as Oliver “marches on New York with his vast army of syncopators.” The ad continues: bolstered by “reinforcements … on hand to bolster up the defense” in the form of Webb's band, as Fess Williams “prepares to defend his native land, ‘Savoy’.”Footnote 17

Such regionalism also drove a “North vs. South” battle at the Savoy in 1929, featuring bands from Richmond and Baltimore against Harlem staples Duke Ellington and Fess Williams. Press coverage promised that the invading bands would “defend the southern laurels” and were “ready to blow their last note in the claim that they are the better orchestras,” while both Williams and Ellington were reportedly “ready to do or die in defense of their city and have musical bars in readiness with which to smite.”Footnote 18

Ballrooms also crafted an atmosphere of spectacle through decoration and costuming. For the Savoy's 1927 July 4th–battle, management promised the Ballroom would be “dolled up in appropriate style” to “commemorate the ‘Spirit of 1776’” through a twelve-hour battle featuring four bands and the debut of Fess Williams's new composition: “Red, White, and Blues.”Footnote 19 In 1934, Pittsburgh's McKeesport Park Pavilion further extended the concept by offering an all-night July 4th–battle outdoors. As the Pittsburgh Courier explained,

Battles are supposed to take place in the wide, open spaces where the war generals declare the shot and shell can do the most damage…to the warriors. BUT in battles of music, the wide open spaces contribute to the pleasure of the listeners and dancers. The cool invigorating breezes … the close-to-nature feel of the grass, trees, and flowers … the splashing, sparkling springs of water! That's when a battle of music takes on new dangers for romantic hearts.Footnote 20

As this event attracted a significant crowd, another battle was scheduled for the following month, and it promised to feature “2,500 dancers and rides and concessions. And thousands of myriad electric lights.”Footnote 21 Thus, the physical transformation of ballrooms into warzones and the exaggerated rhetoric of musical warfare were spatial practices that re-rendered ballrooms as representations of military space. However, the particular military construction they indexed was a nostalgic one: not the immediate horror of the Great War's trenches but the romanticized battles of centuries past, which members of the aristocratic classes could consume from afar as thrilling entertainment. Like the benefit parties of Harlem social clubs, battles could thus also offer African American audiences access to performative signifiers of Euro-American class privilege. Battles could also be intra-city contests designed to settle issues of local dominance as in a 1931 battle seeking “to find best band in Pittsburgh to put Pitt on map.”Footnote 22 In such contests, bands became totemic symbols whose regional identities formed concentric circles. When battling King Oliver, Fess Williams and Webb represented their “home turf” at the Savoy, the neighborhood of Harlem, and the whole of New York City.

Although battles in the late 1920s and early 1930s most commonly focused on regional conflict, the battle format was ideal for indexing bands’ identities along multiple axes of difference. The rhetoric surrounding band battles tended to highlight the most obvious identity-based distinction between the two bands as both the central point of conflict and the novelty that merited a special event. As such, band battles became sites for epic clashes between bands themselves but also between the concentric circles of identity the bands represented in different contexts. Throughout the thirties, regional clashes were joined by battles about nationality, ethnicity, gender, and race. National identity became relevant in the early 1930s when battles began featuring Latin bands. Gus Martel's Cuban Orchestra battled Claude Hopkins, Luis Russell (who was himself Panamanian), and Rex Stewart in 1933. In 1934, the Apollo Theatre rendered the concept theatrically, featuring a battle between Willie Bryant's band and Alberto Socarras's Cubanacan Orchestra as part of the stage revue “Harlem vs. Cuba.”Footnote 23

There were also clashes between male and female orchestras, playing upon the novelty or “freak show” element of a battle of the sexes. In summer 1934, the Sunset Royal Entertainers (an all-male ensemble) battled Gertrude Long's orchestra twice in Pittsburgh. The previous year, the city's Pythian Temple hosted a contest between Stony Gloster's Eleven Clouds of Joy and the Rhythm Queens Orchestra. The Pittsburgh Courier reported that the Rhythm Queens had responded to an open challenge and that Gloster “says that such nerve on the part of a few femmes is too much for musical men to endure, and while it may not be considered nice to beat a lady, anything is fair in love or war—and folks—this is going to be war. A battle. a real battle. a battle of music.”Footnote 24 His attitude illustrates the air of the grotesque or the freakish that could accompany such a spectacle, for a battle must be a special occasion if it suddenly made the public beatings of women not just socially permissible but a featured element of the event's publicity. Gloster's aggressive rhetoric, however, also reveals the danger such battles posed to those holding positions of privilege, because they functioned symbolically as a kind of meritocratic proving ground. In band battles, musical articulations of broader regional, gender, and race hierarchies could be objectively tested via “fair” sonic combat. As such, battles were not only carnival spectacles, but also ostensibly impartial public contests, like sporting events, where marginalized groups could demonstrate their merit unencumbered by socially imposed restrictions.

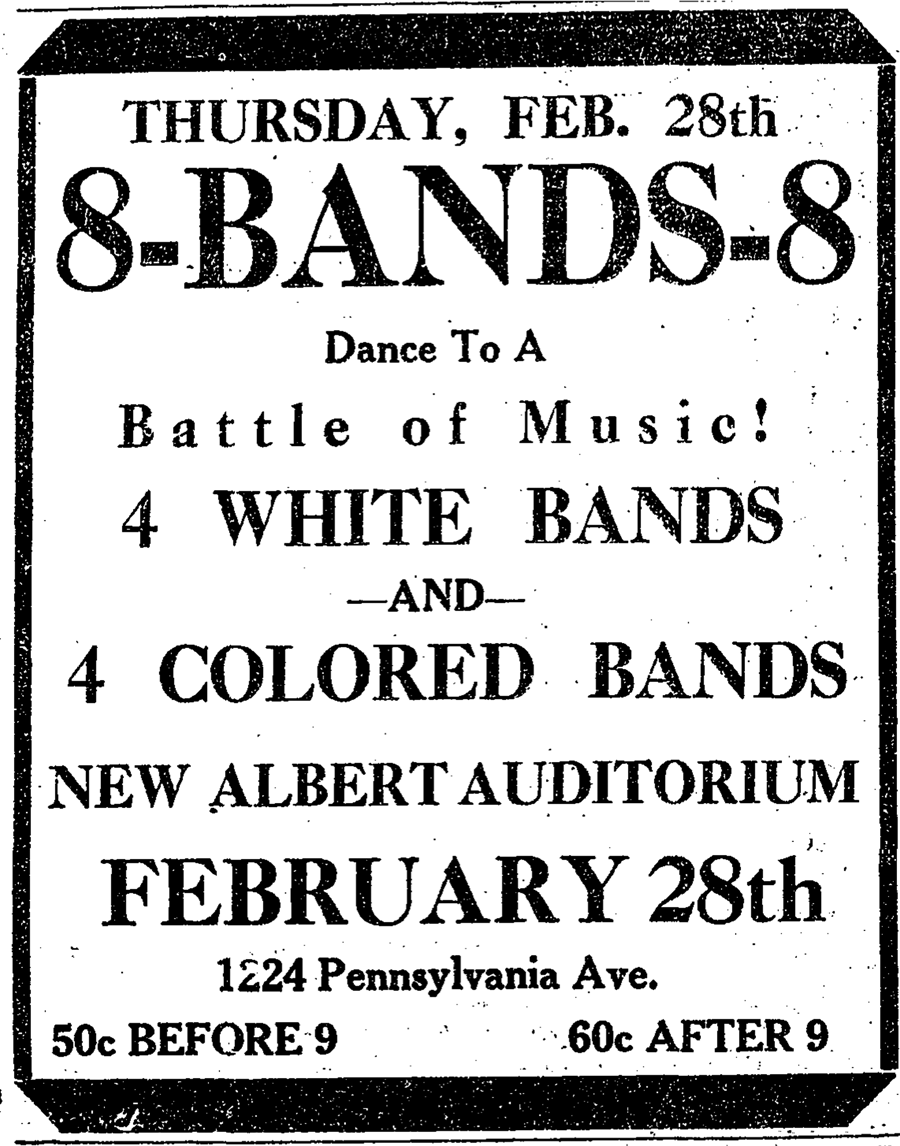

The framing of battles as racial contests expanded throughout the late 1920s into the 1930s, and Webb's battle with Goodman was far from the first to feature black musicians playing against whites. Such events date back as early as 1928, when Fess Williams and Dave Peyton, a prominent black bandleader and columnist for the Chicago Defender, participated in a four way battle at Chicago's Regal Theatre with white bandleaders Abe Lyman and Paul Ash for a special program memorializing black actress and Shuffle Along star Florence Mills.Footnote 25 The following year, Ike Dixon, a black bandleader in Webb's native Baltimore, partnered with promoter Lew Goldberg to stage a massive battle between four black orchestras and four white orchestras at Baltimore's New Albert Hall. Through warfare rhetoric, the event's advertising situated this racial clash as spectacular, novelty excitement.

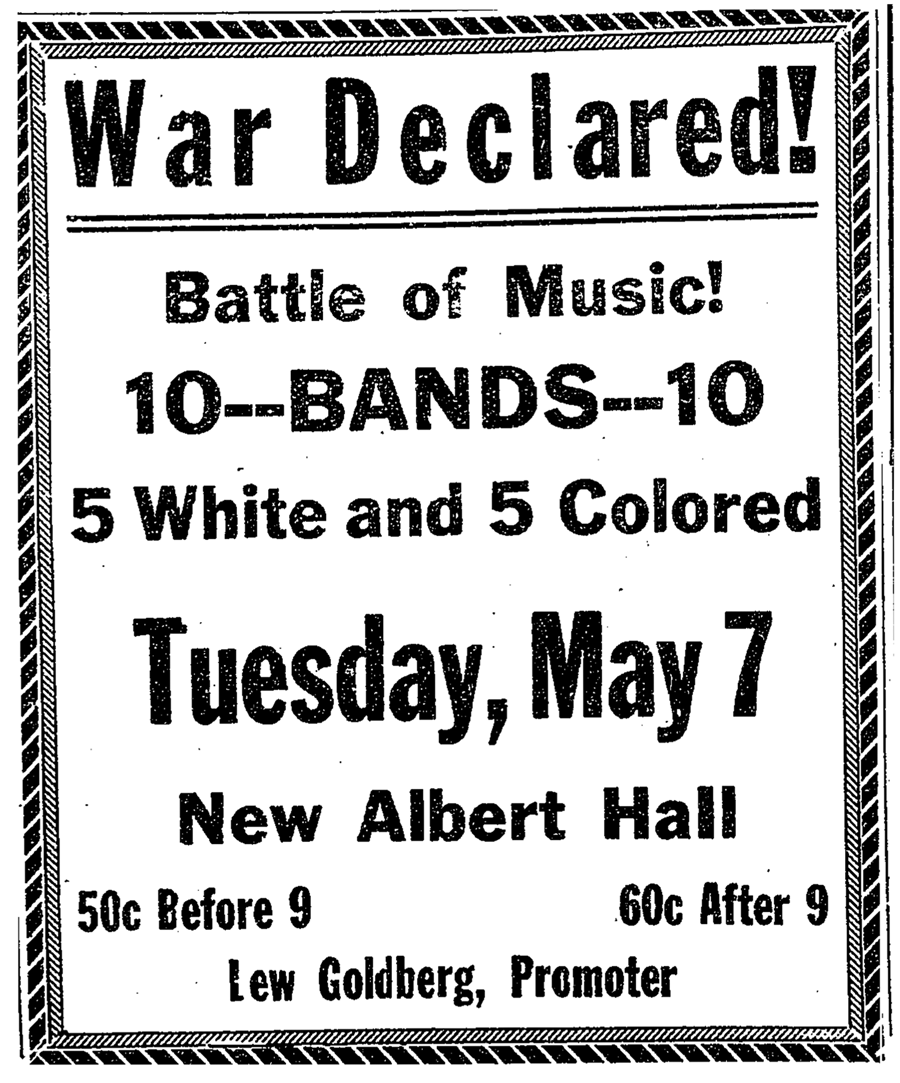

This martial rhetoric was amplified in a Baltimore Afro-American story, which described the contest as “really a mob war and a race riot.” Dixon, according to the report, was ultimately triumphant and crowned Baltimore's “King of Jazz.”Footnote 26 Like the Webb/Goodman battle, this event reportedly packed the ballroom well past capacity as “4,200 persons crowded into a hall that has the capacity of 2,000 persons.”Footnote 27 This event was successful enough that the battle was scaled up and restaged with ten bands just months later. The promise of interracial warfare was again made explicit in the advertising.

Both these events were advertised only in the black press, thus suggesting that the spectacle of interracial battles held especially strong symbolic capital for African American audiences. Harlem ballrooms began hosting interracial battles of music in the early 1930s. In 1933, Fess Williams and Noble Sissle battled white bandleaders Paul Tremaine and Tommy Morton at the Rockland Palace for its New Year's Eve gala.Footnote 28 Later that year, the Harlem Opera House billed a battle between the black Hardy Brothers Band and the white Don Gregory and his Novelty Orchestra as “The Most Unique Entertainment Ever Presented on Any Stage in Harlem—A Black and White Battle of Music.”Footnote 29

Figure 1. Interracial band battle advertisement, Baltimore Afro-American, February 23, 1929. Courtesy of the AFRO American Newspapers Archives.

The contests moved away from this air of friendly novelty spectacle in the mid-1930s as white bandleaders, seeking legitimacy as proponents of “hot” swing music, began explicitly challenging black bands to demonstrate their equal or superior facility. In 1934, white Pittsburgh bandleader Lee Rivers sought a black challenger for a battle at the Pythian Temple. As the Pittsburgh Courier explained,

Unlike some white aggregations, Lee Rivers is anxious to compete with the best colored orchestra in this section. A battle which ordinarily would be won by a colored orchestra on ‘hot’ numbers and by whites on ‘sweet’ numbers, finds in this attraction a different situation. The Deep River lads are said to be able to take care of themselves on both brands of syncopation and it is left to the Sepias [African Americans] to show their best—and it had better be good!Footnote 30

More famous white orchestras would follow this trend, most notably Glen Gray and the Casa Loma Orchestra. Before Goodman's explosion in popularity, Gray's Casa Loma band was widely regarded as the top white exponent of hot swing music. Just a month after Rivers's open challenge, Gray battled Noble Sissle's band before a crowd of University of Pennsylvania undergraduates, who declared Sissle the winner in this “war with the hottest ofay [white] band in America.”Footnote 31 Also eager to test his mettle against black competitors, Tommy Dorsey battled the Sunrise Royal Entertainers at Philadelphia's Nixon Grand Ballroom in 1936 after Dorsey had “boasted that his band would outplay any aggregation of musicians, white or colored.”Footnote 32

Figure 2. Interracial band battle advertisement, Baltimore Afro-American, May 4, 1929. Courtesy of the AFRO American Newspapers Archives.

As interracial band battles became more commonplace during the mid-1930s, Webb began taking part in such contests. In fact, his battle with Goodman was not his first with a white band; it was his fourth. In the two years before his 1937 battle with Goodman, he battled Tommy Dorsey once and Glen Gray twice. His first tangle with Gray in 1935 was part of his participation in a citywide Musicians’ Union Benefit in New York where the Kansas City Plaindealer reported Webb “sailed into the competition ‘four sheets to the wind’ and emerged victorious.”Footnote 33 When the two bands met again the following year, the New York Amsterdam News declared Webb victorious once again based on audience applause but argued that the two bands played vastly different styles, praising Webb's sense of swing and Gray's “mechanical perfection.”Footnote 34 While Goodman lacked Webb's prolific experience in battles, he too participated in a handful of interracial battles before tangling with Webb. In 1935, Goodman battled with two black ensembles—Walter Barnes's Royal Creolians and the Wildcats Orchestra—in a midnight benefit for the Royal Theatre sponsored by the Chicago Defender.Footnote 35 The following year, he battled Noble Sissle during a social event at the University of Virginia; the two bands were packaged together because both were represented by the Music Corporation of America.Footnote 36 While it is unclear why, Goodman was apparently reticent to face Webb's band initially as he reportedly turned down an offer to battle him in 1936, the year before their battle finally took place.Footnote 37 Though it is impossible to know Goodman's mindset, he may have been well aware of the Savoy Ballroom's potent symbolic capital and the thick representational politics involved in battling the most popular black band in Harlem.

Battles were spaces not only to perform such modes of difference, but also to test the social assumptions they triggered. As battles’ rhetoric positioned them as events to “settle the argument once and for all,” when infused with race and gender politics they became laboratories to test social hypotheses. Are women truly capable of doing “men's work?” Are black people naturally deserving of their inferior opportunities? These were the types of broad questions that underwrote the rhetoric of battles of music. When featuring racial difference, battles activated the ideology of racial uplift and its emphasis on meritocracy and fair play. Absent the segregationist hierarchies that bolstered white bands’ professional success, battles became spaces where racial essentialism was confronted within a setting that would ostensibly yield a meritocratic result.

This history makes clear that Webb and Goodman's 1937 battle functioned within a specific discursive tradition built over time within African American ballroom culture. Their battle thus made two simultaneous, though perhaps conflicting, promises. First, it promised a night of musical extremes where massive crowds and a “main event fight” atmosphere would create an elevated sense of excitement and intrigue. Second, it offered a musical format through which to enact and potentially settle broader debates about racial difference and local supremacy. Through a foe like Goodman, who represented both whiteness and a nationally successful brand of swing music, Webb's band symbolically represented the Savoy Ballroom, the neighborhood of Harlem, and black people as a race.Footnote 38

The Rhetorical Makings of a Mythic Clash: Racialized Discursive Confluences in 1937

While battles of music were far from novel by the time of Chick Webb and Benny Goodman's 1937 clash, the Webb/Goodman battle's symbolic resonance has clearly proven especially potent and far-reaching. While jazz musicians and critics engaged in robust and at times vitriolic discussions of race, authenticity, and talent before the mid-1930s, swing music's rapid emergence as a nationally dominant form of popular culture increased the stakes of these discourses. Here, I identify three specific factors that converged to drastically amplify this event's discursive power: Goodman's singular status as the white musician whose success most iconically represents “the swing era,” an active and increasingly explicit debate over the racial ownership of jazz music, and the emergent significance of “black champions” as politically significant cultural symbols.

Goodman was part of a wave of white bandleaders in the early 1930s who moved toward playing in the “hot” style they admired among leading black orchestras, but in 1935 he achieved a level of success that set him apart from his contemporaries. It was in this year when Goodman began receiving regular national radio play on the “Let's Dance” program and when he gave a now famous performance at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles that is widely credited as marking the emergence of swing music as the United States’ dominant genre of popular music.Footnote 39 Lewis Erenberg, who notably identifies 1935 as the beginning of “the swing era” as a mass cultural phenomenon, credits Goodman as “instrumental in bringing jazz from the margins to the center of American culture.”Footnote 40 Stylistically, Goodman set himself apart from his white peers in part through commissioning work from top black arrangers, most notably Fletcher Henderson. Jeffrey Magee goes as far as to claim that “Goodman and Henderson built the Kingdom of Swing from recycled shards of earlier black jazz and dance music.”Footnote 41 While Goodman's collaboration with Henderson is cited most frequently, Goodman also worked with Webb's principal arranger Edgar Sampson. Webb's band was also connected with Goodman's through a highly publicized controversy over Goodman's reported attempt to “poach” singer Ella Fitzgerald from Webb's band.Footnote 42

Goodman occupied a particular space in the late 1930s as he was simultaneously massively successful commercially and overwhelmingly lauded by jazz critics. Musically, Goodman was part of, in Elijah Wald's words, “an elite clique of high end New York players” who balanced their dedication to “hot” rhythm and African American innovations with a musical versatility that made them comfortable playing in a range of commercially popular styles.Footnote 43 Goodman was thus able to balance the sometimes competing demands of popular audiences and an emergent group of “elite” white jazz critics dedicated simultaneously to affirming the authenticity of “hot” jazz and to the anti-commercialism this soundscape's articulations with blackness symbolized.Footnote 44 Critics and audiences were, by 1935, far more receptive to understanding jazz as, fundamentally, a form of black music.Footnote 45 While white desire for closeness with black musical production certainly existed long before the swing era, in the 1930s an emergent discourse community of predominantly white jazz critics increasingly associated their own appreciation for what they saw as authentic black music with a political commitment to racial justice and anti-capitalism. Association with, and appreciation of, jazz as black music increasingly symbolized a social and political commitment to freedom and racial justice while still offering the same seductive lure of the other that defined white “slumming” culture in the late 1920s. That Goodman was, in Erenberg's words, “able to bring that African American sense of Freedom to the larger white world” positions him squarely within a dynamic of appropriation wherein white audiences seek white purveyors of African American culture.Footnote 46 Goodman was thus particularly well positioned to satisfy what Greg Tate has identified as the white-dominated popular music industry's perpetual desire for sufficiently convincing white facsimiles of African American culture bearers.Footnote 47

Goodman owed much of his success to his connection with John Hammond, who repeatedly acted on Goodman's behalf in his roles as both critic and impresario. Throughout the mid- and late 1930s, Hammond consistently aided Goodman in finding opportunities, advised the bandleader on style and personnel, and wrote enthusiastically about him in various magazines. Hammond was particularly instrumental in steering Goodman toward black arrangers, including both Henderson and Sampson.Footnote 48 A major aspect of Hammond's interest in Goodman was their mutual admiration for black jazz musicians and Hammond's conviction that Goodman's success could be a vehicle for racial justice. Gennari goes so far as to describe Hammond's investment in Goodman's career as “an act of black folk reclamation that infused one of his most blatantly commercial endeavors.”Footnote 49

Goodman's value to, and relationship with, this emergent “mainstream” of white jazz critics was such that after his battle with Webb, white critics tended to focus less on Webb's victory than on explaining and justifying Goodman's loss. When reporting on the battle, white critics focused significant attention on the less-than-ideal circumstances under which the two bands, and especially Goodman's, were expected to perform. Explanations ranged from technical difficulties to strong police presence to a hostile and biased crowd. From accounts in the white jazz press, the bands were difficult to hear due to the massive crowd, the ballroom's acoustics, and a malfunctioning PA system.Footnote 50 Hammond was particularly outspoken, complaining that, among other things, “the noise level was so high that none but the brass soloists was even audible.”Footnote 51 A reporter for The Melody Maker echoed Hammond's complaint, observing that “it was impossible to hear the music over the dance floor, and only spasmodically did the staccato notes of the brass sections or the accented beats of the rhythm batteries ring clear enough through the hall.”Footnote 52 Whatever the case, these critics commonly emphasized this night's singularity and used its ostensibly unique characteristics as a means to dismiss its validity as anything more than a single event, effectively a fluke. This framing emphasized the impossible, unwinnable situation in which Goodman found himself and thus his grace and courage at even making the attempt.

Goodman and Krupa's sustained public graciousness helped to maintain what Magee has described as the “delicate consensus” of interracial fan and critic support that sustained Goodman's popularity throughout the late 1930s.Footnote 53 The band's position, I argue, is highly related to the phenomenon of “immersion” through which Mickey Hess and Loren Kajikawa have explained the balance of commercial success and cultural acceptance attained by exceptional white hip-hop artists during the 1980s. Hess argues that white rappers felt “a need to acknowledge their place as outsiders, as if to anticipate criticisms that they are treading on black turf.”Footnote 54 Beyond simple acknowledgement, immersion requires white artists to demonstrate substantial respect for African American artists and active engagement in anti-racist work to support them.Footnote 55 For white bands, battles were thus one part of enacting this immersion. Goodman, whose visible anti-racism also included his groundbreaking public performances with an interracial trio and quartet, effectively won by losing as he made a good showing “on black turf” in Harlem's most iconic ballroom yet still showed deference to that ballroom's African American house band. Even explicitly endorsing a black band's superiority itself represented the kind of insider knowledge and commitment to racial progress that endeared white bandleaders to members of the emerging jazz press who held similar values.

Indeed, Goodman's rise to popularity and his reputation as a supporter of black musicians were largely underwritten by a significant coterminous shift in jazz critical discourse: an increasingly explicit acknowledgement among both white and black critics that jazz was predominantly an African American form of music. A new generation of white jazz critics emerged in the early 1930s from international circles of “hot” (read: “black”) record collectors who aligned with the political left wing's “popular front” movement to form a jazz critical discourse that centered blackness and antiracism.Footnote 56 Writers such as John Hammond and Marshall Stearns in the United States, Leonard Feather in Great Britain, and Hughes Pannasié in France drew from contemporaneous trends in folklore and anthropology to craft a discourse that disputed what was at the time a prevailing narrative: that white artists such as the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and Paul Whiteman were jazz's originators and highest quality contributors.Footnote 57 This rhetoric, however, presented a fairly obvious contradiction within white jazz magazines as it escalated around the same time they introduced “all-star” band polls. Such band polls, despite escalating acknowledgement of African Americans’ central contributions to jazz, frequently featured majority-white lineups.Footnote 58 African American jazz critics were quick to acknowledge this disparity with straightforward and aggressive critiques that reflected the black press’ mid-1930s popular front–inspired escalation of both explicit advocacy for collective action and topical emphasis on popular culture.Footnote 59 Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere, attributing jazz criticism's anti-racist shift exclusively to this emergent and predominantly white jazz critical apparatus erases the pivotal role of entertainment writers in the black press, whose own popular front–informed anti-racism was coterminous with, or even anticipated and informed, white jazz critics’ new-found progressivism.Footnote 60

Arguably the most outspoken African American critic on this subject was Pittsburgh Courier columnist Porter Roberts, who used Webb's victory over Goodman to validate his claims of widespread racism in the national reception of swing bands. Highlighting the incongruity between the battle's result and the two musicians’ performance opportunities, Roberts suggested that NBC radio should feature Webb immediately before CBS's Goodman broadcasts. Roberts felt this would productively contest CBS's continued insistence on billing Goodman as “the King of Swing,” by effectively reproducing the Savoy Battle via the airwaves for a majority white audience nationwide.Footnote 61 He drew upon the battle to specifically challenge black bands’ marginal positions within various predominantly white jazz periodicals’ yearly ranking polls. In December 1937, he made clear his indignance at the results of Downbeat's 1937 list of top bands:

Now, I feel sure that the famous colored musicians who have become the ‘goats’ of ‘Down Beat's’ contest, do not mind forgiving the prejudice that has been shown by most of the white voters for [illegible word in document] is their privilege! Now to some, the ‘RATINGS’ and another hearty laugh, won't you join me? Quick look at this: In the swing band section. Benny Goodman, Bob Crosby, Tommy Dorsey, and Casa Loma (white) bands are voted ABOVE Jimmy Lunceford, Chick Webb, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie!! Which ain't true. Chick Webb out-played’ Benny Goodman in Harlem a few months ago. And I don't believe you could pay the other three to play a battle of music with Jimmie, Duke, and Count. Haw! (How much do you want to bet?)Footnote 62

For Roberts, the idea that victory in a battle of music was proof of musical superiority became a tool to name and to dispute the systematic racism through which black bands were both underrated and denied better opportunities.

Recognizing the potency of battles’ racial signification, Roberts called on black bands to continue fighting and winning interracial contests as a means of combating racial inequality. Roberts even questioned the utility of black bands engaging in battles of music that did not include white bands and thus did not explicitly contest racism, arguing in advance of Duke Ellington's 1938 battle with Jimmie Lunceford that he, “Just can't see any real advantage in it, can you? I really think they could bring more credit to the colored band world if they would concern themselves with battles of music with some of the white ham bands that are being rated over them!”Footnote 63 Through this criticism, Roberts articulated an explicit critique of racism within the world of popular music that challenged both structural racism and appropriation within the music industry. Without mentioning Webb and Goodman specifically, other African American critics seized upon the battle format to offer new possibilities for race-based musical spectacle. In the fall of 1938, the Courier's Billy Rowe proposed an “All-American Swing Battle” at Carnegie Hall featuring an all-star group of black musicians, which he would select, against a select group of white players to be chosen by white bandleader Paul Whiteman. More interested in dialogue than conflict, Rowe intended that “this would not be a battle to prove the superiority of either musician but to forever stamp into the minds of critics and public the difference in style of white and colored swingsters which makes past comparison so out of place.”Footnote 64 Perhaps seeking to capitalize on the success of Goodman's now-famous concert, Rowe envisioned the battle taking place in Carnegie Hall as a benefit for the blind musicians’ fund. Webb was reportedly among the black bandleaders who knew about and supported Rowe's vision. While the Courier reported that “It is the first time in the history of jazz or swing music that such a thing has been attempted,” such a statement in fact recapitulated the rhetoric of novelty and spectacle that had driven battles of music for years.

Roberts and other black critics’ strategic use of the Webb/Goodman battle functioned within a broader paradigm of demonstrating black excellence through fair, public competition that traded on specific mid-1930s developments in media discourse surrounding two African American athletes: track & field star Jesse Owens and boxer Joe Louis. Owens won four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, making him the most successful American athlete in that year's games. In concentric circles of totemic identity, Owens became a potent symbol both of black excellence and of American excellence, two framings that worked in tandem to contest the Nazi regime's narrative of Aryan genetic supremacy and the increasingly militant Germanic ethnic nationalism that narrative supported.Footnote 65 In June 1937, just weeks after Webb's battle with Goodman, Louis became world heavyweight boxing champion by knocking out the defending champion, white boxer James Braddock. By the time of his 1937 heavyweight title fight, Louis was already among the most visible African Americans in the United States, and his ubiquitous appearances in black newspapers was a substantial factor in the black press’ explosive circulation growth during the mid-1930s as he provided African Americans, in Anthony Foy's words, “a vicarious outlet for their hostility to Jim Crow.”Footnote 66 As Erenberg explicates Louis's symbolic power within black communities, “when Louis beat white fighters, black Americans took vicarious pleasure in the defeat of a symbolic aspect of white supremacy.”Footnote 67 The black press in particular leveraged the idea that Owens's and Louis's victories offered evidence that absent segregation and structural disadvantage—when given a level playing field— African Americans could succeed in any area.

The “vicarious outlet” Louis, and certainly Owens, provided African Americans functioned as a form of what Kenneth Burke has termed “symbolic boasting.” Applying Burke's work to Owens's Olympic success, Mike Milford explains that, “Symbolic boasting, the celebration of another's accomplishments as one's own for ideological purposes, is the means by which a community asserts its principles through a hero's actions.”Footnote 68 Louis and Owens were the two most iconic members of a generation of publicly successful black athletes in the 1930s who, Erenberg claims, “contributed to a dream of the future that included strong black men on the public stage fighting back against white supremacy in athletics and everyday life.”Footnote 69 The concept of symbolic boasting helps make apparent that just as Owens served to repudiate the concept of German superiority and Louis of white supremacy more broadly, Webb's victory over Goodman was a vehicle through which the African American community could dismiss any white claim to originary credit for, cultural ownership of, or superior musicianship within the now nationally hypervisible arena of swing music.

To be sure, one-to-one comparison between Goodman's battle with Webb and Louis's championship fight with the Irish-American Braddock does not hold to say nothing of Louis's still more famous bout with Max Schmeling the following year, especially given Goodman's Jewishness and Schmeling's growing role in the late 1930s as a symbol of Nazism. Nevertheless, Goodman could coherently symbolize whiteness as the antithesis of Webb's blackness while simultaneously reading as part of the white—and specifically Jewish—anti-racist jazz critical apparatus standing in explicit solidarity with African Americans.Footnote 70 Indeed, just a month after his battle with Webb, Goodman performed in Chicago with his interracial quartet immediately following the Louis–Braddock fight, a gesture many whites and African Americans alike took as directly reflective of the racial progress Louis's victory represented.Footnote 71 Such dual signification was legible in a climate where, as Erenberg argues, white people sympathetic to the cause of integration could understand Louis's fights with white opponents as “the staging of a theatrical race war in the ring” without Louis's victories provoking any subsequent racial animosity in them.Footnote 72 This discourse was not, however, exclusive to the black press; it was strongly reinforced by white leftists as well. The “popular front” turn in US and international socialist movements during the 1930s resulted in both stronger anti-racist solidarity with African Americans and a greater emphasis on popular culture as a subject of, and vehicle for, political discourse. Communist publications like the Daily Worker, one early source of the jazz criticism that would later appear in publications like Downbeat and Metronome, celebrated Louis's victories with language that both informed and reinforced the explicit racial allegories forwarded in the black press. This solidarity and discursive alignment was bolstered by the strong Jewish motivation to see Owens's triumph in Berlin and Louis's position as a worthier championship opponent than German boxer Max Schmeling as explicit repudiations of Hitler and the Nazi party's rapidly escalating anti-Semitism.

It was through this specific confluence of events and perspectives that discursive strategies highlighting black excellence flowed between sports and entertainment writing and between the black press and predominantly white specialty publications for jazz criticism. The specificity of this conjuncture bolsters Milford's observation regarding Jesse Owens that, “in order for his victory to carry ideological weight, it had to occur in an ideological environment that would lend it rhetorical power.”Footnote 73 Given post-1935 discourse regarding the so-called “swing-era,” and specifically black critical pushback against white colonization of black popular music, Webb's public contest with white swing music's hypervisible “king” offered a nearly perfect set of conditions within which to map the emergent discursive logics totemizing black male athletes onto Webb as a defender of black superiority in the field of jazz. For African American audiences, the Webb/Goodman battle's symbolism was legible simultaneously within the black press’ dominant and increasingly radical paradigm for routing anti-racism through male icons in popular culture and also the African American tradition of band battles as spectacular indexers of difference dating to at least the mid-1920s. In emphasizing Goodman's humble, if temporary and commercially inconsequential, deference to Webb, white critics and historians—both at the time and subsequently—have used this battle as a vehicle to bolster their positioning of jazz as a form of African American music while also centering the skill, graciousness, and proximity to blackness of ostensibly anti-racist white protagonists.

Conclusion

By emphasizing war imagery and boxing rhetoric, battles placed swing musicians in the two identity categories in which black American men had successfully disrupted narratives of black inferiority: as athletes and as soldiers. While battling was a playful mode of communication, it could also become a powerful symbolic discourse about racialized narratives of superiority or inferiority, especially when interracial battles evoked the same signifying capacities through which Joe Louis and Jesse Owens had emerged as heroes both within the black community and nationally. As musicologist Ken McLeod has argued, African American sports culture and musical battles became thoroughly intertwined in the 1930s as African American musicians and audiences assimilated the rhythms of symbolic competition into modes of musical play.Footnote 74 Routed through a press apparatus already hypervigilant in emphasizing black cultural ownership and combatting the unfair advantages white artists enjoyed, the rhetorical logics that shaped battles of music found in Benny Goodman and Chick Webb a near-perfect set of foils through which to do this symbolic work.

More broadly, this analysis of the Webb/Goodman battle offers us important interdisciplinary insight into the concept of spectacle. The field of film studies has put forth two assumptions about spectacle: that it is a principally visual phenomenon and that it exists apart from or in opposition to narrative.Footnote 75 First, battles of music offer a clear instance of multisensory, rather than exclusively visual, spectacle as the experience relied as much, if not more so on the auditory and haptic experiences of dancing audiences in black ballrooms. Second, the Webb/Goodman battle's historiographic life certainly disrupts the dichotomization of spectacle and narrative. Rather, it largely affirms the position taken by Bruce Magnusson and Zahi Zalloua, who argue in the introduction to their volume on mass mediated political spectacles that, “what makes an event a spectacle—an image that takes on its own life—has everything to do with the reception of the event.”Footnote 76 The Webb/Goodman battle's historiographic enshrinement largely affirms their claim that a spectacle “demands coproducers of knowledge”: participants, spectators, journalists, mass media outlets.Footnote 77 However, where Magnusson and Zalloua see this is an emergent dynamic of spectacle made possible by contemporary social media technologies, the performative dynamics of battles of music and the narratives surrounding the Webb/Goodman battle in specific suggest that the phenomenon of spectacle as collective, participatory narrativization through online social media platforms is but the most recent iteration of a dynamic that has long been central to popular culture.

In the case of Webb and Goodman's clash, it is critical to understand how the specific discursive conditions of jazz criticism in the late 1930s interacted with the battle's decade of pre-history to yield the conditions of possibility for such an enduring spectacular narrative. The existing framework of battles of music as symbolic displays of difference traded on an intersection of military rhetoric and black masculinity simultaneously legible within and amplified by specific developments: Goodman's emergence as the so-called “king” of swing music during a period of rapidly escalating mainstream popularity, an increasingly sharp critique of both white supremacy and white appropriation among black and white writers in the newly forming discursive world of “jazz criticism,” and specific developments in geopolitics and international sports that drastically heightened the rhetorical stakes of black victory in competitive environments. Indeed, the Webb/Goodman battle was uniquely important precisely because it was simultaneously typical and exceptional. Because it was typical, its spatial rhetoric was legible to African American audiences within an established tradition of spectacular performance, and this legibility informed its subsequent critical reception. It became exceptional through its relationship with a specific discursive moment that catalyzed and amplified its signifying potential, cementing this battle of music's legacy as enduring and significant, if not entirely unique.