Walter Damrosch . . . conducts like a business man; that is, in his interpretations he never has been able to convince the expert reviewers . . . that he is actually more concerned with the reading of a symphony than with the number of seats sold in the first balcony.Footnote 1

During the summer of 1909, New York Symphony Orchestra (NYSO) conductor Walter Damrosch (1862–1950) was in frequent contact with the modern dancer Isadora Duncan (1877–1927). Damrosch had entered an unusual collaboration with the native San Franciscan the year before, and was eager to feature her barefoot solo dancing to Gluck's Iphigenia in Aulis and Beethoven's Seventh Symphony on his upcoming concert tour of the Midwest. He wrote in July to her European manager, Wilhelm Schultz, with the assurance of hefty profits: “I believe you will be very satisfied with the results, which will be A great deal of Money!!”Footnote 2 This outburst, underlined twice in English in the otherwise German Sütterlin hand, points obviously to the financial motive for Damrosch's peculiar ambition to engage a “barefoot dancer” at a time when lowbrow vaudeville dance entertainments posed an alarmingly popular alternative to the vaunted virtues of the concert hall. Damrosch nods to this uncomfortable paradox when he grumbles to Herr Schultz that his own New York agent, R. E. Johnston, has engaged the vaudeville dancer Maud Allan (1873–1956)—the notorious “Salomé” dancer—and asked him to conduct for her upcoming tour. “How insulting!” Damrosch scoffs. “You can imagine that I declined this offer.” Neatly confronting the social space between vaudeville and the concert hall, this communication centers Damrosch's interest in Duncan along fault lines of high and low, sacred and profane, and makes an apt starting point for this study of the commercial pressures elite orchestras faced in the vaudeville age (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. “Isadora Duncan.” Photograph by Paul Berger, 1908. Bibliothèque national de France.

Figure 2. Maud Allan as Salomé in “The Vision of Salome” published by J. Beagles & Co., 1908. Bromide postcard print. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Coming from a respected guardian of an ostensibly sacralized musical culture, Damrosch's disdain for “Salomé Dancers” is not surprising; in 1908 their lurid stage and film enactments of St. John the Baptist's beheading had aroused a frenzy of public curiosity and critical contempt. His equal confidence in a commercial triumph with Duncan, however, and his determination to lend the might and reputation of his orchestra to another skimpily dressed dancer, is more difficult to understand. Numerous dance scholars mention Damrosch in the context of Duncan's first appearances in the United States.Footnote 3 But the tangle of colliding convictions their tours provoked has not been analyzed, nor has what they reveal of compromises between high art music, commercial entertainment, Puritan morality, and shifting patterns of devotion to each at the century's turn. In order to situate the Duncan-Damrosch collaboration—and the desecration of symphonic music it suggested—within a wider frame of “the sacred” in the United States, I look to similar processes of cultural compromise unfolding in American Protestantism by comparing Damrosch's turn to Duncan with contemporary evangelical preachers’ recourse to popular “profanities” in big tent revivalism, particularly to Billy Sunday's aggressively pantomimic preaching. I examine the Duncan-Damrosch tours, their managers, and a cast of their most vocal critics, with a threefold purpose: first, to gauge Damrosch's motivation for engaging a dancer; second, to weigh the objections he aroused on a scale that measures both musical and religious faith against the ostensibly profane counterweight of commercial dance entertainments; and, finally, to consider conducting, preaching, and dancing as culturally coded movement practices, each shaping the sacred in relation to the profane. With these relationships in view, we can situate the Duncan-Damrosch tours within dual conceptions of “sanctity”—musical and religious—to better see how elite institutions like the NYSO adapted to market pressures from an entertainment industry giddy for dance, and how US American audiences and critics made sense of music, dance, and gesture as intersecting forms of cultural capital.

Between Sacred and Profane

Faith, whether in God or in music, serves this study as a fulcrum upon which perceptions of popular entertainment and elite music tipped. The secularized Kunstreligion (“art religion”) of immigrant German musicians who proselytized its higher truths to the New World was still a powerful selling point for orchestral music in the United States at the turn of the century. Karen Leistra-Jones has shown that for many German-American musicians like Damrosch and his father Leopold (1832–1885), Beethoven's symphonies anchored Kunstreligion as a social practice in which the concert became a ritualized devotional activity, a form of public worship giving spiritual nourishment to an educated class increasingly distanced from traditional religion.Footnote 4 With his German upbringing in the company of such musical giants as Johannes Brahms and Franz Liszt, Walter Damrosch had impeccable credentials as a priest of high musical culture, and a sincere wish to bring its redemptive benefits to US American audiences.Footnote 5

Damrosch's foreign training further advanced his musical evangelism. Unprepared when the death of his father in 1885 put him (at age twenty-five) in line to conduct the NYSO, he turned to an intense course of private study with Hans von Bülow, a zealous disciple of Beethoven's musical revelations.Footnote 6 Damrosch absorbed and emulated Bülow's ardor, eventually programming his own complete cycle of the Beethoven symphonies with the NYSO, including repeating the Ninth in one evening.Footnote 7 Reflecting on this novel practice, Damrosch declared that at certain ecstatic moments of his music, Beethoven “saw God face to face and the Almighty touched his hand with divine fire.”Footnote 8 Forty years of conducting confirmed Damrosch's belief that Beethoven, Mozart, and Brahms “smile upon us serenely and eternally from the heavens in which they dwell as gods among the gods.”Footnote 9 For many in the United States, Damrosch himself approached sacred status as an anointed messenger of music. According to music critic W. J. Henderson, Damrosch's touring festivals, pre-concert lectures, and work in radio made him “an invisible preacher of the gospel of musical beauty.”Footnote 10

Damrosch's transgression with Duncan is all the more puzzling given that the contemplative listening required of the sanctified German symphonic repertoire necessarily positioned dancing as a frivolous, feminine, and profane counter-influence, pulling the mind to a debased manner of musical enjoyment.Footnote 11 Over the course of the nineteenth century, the erasure of functional social dance from German high art music became a tacit condition of its sacralization; it became a key means, in other words, of separating a “serious,” sanctified concert repertoire from the sensuous, feminine frivolity associated with French culture.Footnote 12 Symphonic music's distance from the lower orders of US dance entertainment further legitimized a physical culture of reverent stillness in the concert hall.

The introduction of highbrow European orchestral music to US American audiences invites a tangle of questions about class, commerce, and religion. The United States’ belated raising of the brow in Lawrence Levine's rendering has been richly elaborated, such that we now have a more nuanced picture of a variegated and culturally mobile nineteenth-century US American public.Footnote 13 Yet as late as 1915, Van Wyck Brooks asserted that antithetical “twin values” of “highbrow” and “lowbrow” still divided every aspect of US life. Between them, there was “no genial middle ground.”Footnote 14 The public record on the Duncan-Damrosch tours confirms that many US Americans’ reverent attitude to orchestral music demanded its seclusion from the explosion of dance entertainment in the United States’ rapidly growing urban-industrial centers.

Some music critics accused Damrosch of patent profiteering. One reporter commented that with Duncan he was “pandering to the morbid and sensual, in order to fatten the box office receipts.”Footnote 15 The weekly Musical Courier complained of a “commercial aggrandizement” that distinguished Damrosch from his eminent peers who more fittingly devote themselves “to art and its dignified propagation.”Footnote 16 According to this report, Damrosch's “itinerant organization” is inferior to all other permanent US symphony orchestras (all led by artistically impassioned foreign conductors) for its excessive touring, playing at festivals and amusement parks, and “tours with a gifted dancer, for whose fine terpsichorean exhibition the orchestra plays obligatos [sic] of Beethoven symphonies.” It is all “an extremely clever business” that makes Damrosch alone the leader of a mere “business orchestra.”

Such chasing after money requires very little musical talent, but a plenteous supply of the . . . ability necessary to make a coal mine pay dividends. . . . A conductor blessed with that knowledge gives the impression that during some resounding climax of Beethoven, . . . he may have screamed to the librarian: “Don't forget to telegraph the change of program to Huckleberryville.” Or that by holding up his left hand with the fingers spread out he was signaling to his secretary beyond the stage door: “Don't take less than fifty percent of the gross in Oatmealtown.Footnote 17

In this critique and many others, Damrosch's engagement of a dancer was merely symptomatic of a broader apostasy driven by his capitulation to the tastes of a mass public.

Who then was this renegade dancer Damrosch saw fit for the concert hall? Breaking with typical dance-hall productions that featured elaborately costumed women dancing to second-rate music, Duncan danced her plotless, solo choreographies to classical music in loose linen draperies and bare feet. Along with the corset and point shoe, she rejected mechanical combinations of ballet steps as empty technical exercises.Footnote 18 Instead, her interest in ancient Greek sculpture, Darwin, and Monism led Duncan to a movement style based in nature, her entire body responding to a “universal rhythm.”Footnote 19 Dancing, she writes in her 1904 manifesto, “is a soul we see moving. . . . Each movement reaches in long undulations to the heavens and becomes a part of the eternal rhythm of the spheres.”Footnote 20 Emulating the movement of animals, waves, and clouds, her gestures flowed organically one from the next. Greek poses and attitudes connected walks and runs in a succession of ethereal movements, rippling from torso to limbs as a symbol of eternal life.Footnote 21

After failing to interest US American audiences in her early dance experiments, Duncan launched her career among German artists and intellectuals. By 1904 she had established a home and school in Berlin and achieved a stunning public success across Germany. Like many of her fellow Americans at the turn of the century, Duncan admired German culture as the pinnacle of philosophical, scholarly, and musical achievement.Footnote 22 Believing her dances to be the physical counterparts of the classical masterworks, Duncan helped herself to German concert music and believed its veneration among educated German listeners would accrue to her dances as well.Footnote 23 Though she was a runaway hit with audiences, German music critics bristled at her bold appropriation of Bach, Gluck, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Wagner, and, most troubling, Beethoven's Seventh Symphony.

News of German critics’ response to Duncan reached US American readers, creating a wave of curiosity about their native ambassador of “barefoot dance.” The Columbus Journal reported, for instance, that while the German public “fairly wept to think that Beethoven himself could not have seen this fulfillment of his music,” professional musicians and critics greeted Duncan's performances with “a long critical groan” at the “insolence” of Duncan's musical “desecrations.”Footnote 24 Set in terms of the sacred and profane, these critiques are key to understanding the US uproar over Damrosch and Duncan, for both factions objecting to Damrosch's experiment did so in the name of something sacred: music critics defending the sanctity of the concert hall, and clergymen saving souls from the evils of dancing.

Firm categories of high and low like Van Wyck Brooks's bore a strong resemblance to turn-of-the-century religious constructs of the sacred and profane. In 1915, social scientist Emile Durkheim famously theorized that religious belief is fundamentally characterized by a division of the world into two distinct domains, “which are translated well enough by the words profane and sacred.”Footnote 25 What distinguishes the sacred so absolutely from the profane, he says, is that the mind “irresistibly refuses to allow the two corresponding things to be confounded, or even to be merely put in contact with each other.”Footnote 26 These mutually exclusive categories also found expression in urban preachers’ realization of heaven and hell. Revivalist Billy Sunday's soul saving, for instance, offered a simple choice: “You are going to live forever in heaven or you are going to live forever in hell. There's no other place—just the two.”Footnote 27

Durkheim's exclusive ordering of the sacred and profane stands as a conceptual ideal from which we may also consider cultural manipulations of sanctity and profanity in the negotiation of high and low culture, particularly in the relation of art music and entertainment, and their competing claims on devotion in a modern consumer society. Yet in the cultural distance between Damrosch and the Salomé dancers he openly despised, Duncan occupied a bewildering middle ground, precisely the medial space that makes Lawrence Moore's account of US religiosity an attractive alternative to Durkheim's exclusive dichotomy. In Selling God: American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture, Moore asserts that the impenetrable categories of sacred and profane were a mere illusion in the 1880s and 1890s, when the success of urban US entertainment gradually forced those in the high arts to concede ground to the profane for their own survival. By degrees, according to Moore, “religion itself took on the shape of a commodity” looking for ways “to appeal to all consumers, using the techniques of advertising and publicity employed by other merchants.”Footnote 28 Kathryn Oberdeck further describes the spiritual appropriation of popular culture as part of “a longer history of compromise between piety and pleasure.”Footnote 29 In many respects, Duncan was a brilliant choice for Damrosch's spiritual-commercial compromise. She had become the figurehead of a dance rebellion that Edward Ross Dickinson argues targeted two key points of vulnerability in modern European culture: “the modern market, and the modern soul.”Footnote 30 Claiming herself that art devoid of religion “is mere merchandise,” Duncan was nonetheless a savvy manipulator of the restless relationship between religion and commerce; her universal spiritual message enacted an alternative to traditional religion for a mass audience, hybridizing popularity with respectability in the process.Footnote 31

Similar crossings of faith and commerce were occurring in US Protestantism as well. The Old-World model of sacralization based on a mystifying, ritualizing, and thus exclusive mechanism of uplift breaks down when we consider the crowded and very popular nature of the United States’ Third Great Awakening (1855–1930)—a mingling of big tent expressions of faith with big top commercial entertainment.Footnote 32 In this revival movement, a new form of sacralization was underway that in fact demystified, democratized, and popularized US religion. The same renovation of the sacred could be said to shape Damrosch's attempt to popularize orchestral music with a dancer whose movement practice brought a modern message of spiritual redemption to a mass audience.

Reciprocal Rescue

Despite her brilliant success in Europe, Duncan returned to the United States in August 1908 with justifiable trepidation. The results of her youthful rebellion against ballet a decade earlier had earned more derision than praise. Curiosity about her return ran high, yet Duncan's fears were at first confirmed. Her manager, Charles Frohman, unwisely booked her in his own Criterion Theater on Broadway for a series of concerts under the musical direction of Gustav Saenger. Duncan recalls the fiasco: “He presented me in the heat of August, and as a Broadway attraction, with a small and insufficient orchestra.”Footnote 33 The result was, according to Duncan herself, “a flat failure.” Most critics agreed that she was in the wrong place at the wrong time. The New York Sun reported that audiences for her Beethoven program were “disappointed in not seeing a Salomé.”Footnote 34 Variety concluded that Duncan's “long evening of classic dances” was lost on a summertime Broadway audience.Footnote 35 After concerts in Philadelphia, Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse, she broke her contract with Frohman, who recommended she return to Europe.Footnote 36 Duncan as well had come to regard her return to the United States as “a great mistake.”Footnote 37 At this low point, Damrosch, having seen Duncan at the Criterion, ventured to her loft in the Beaux Arts building and persuaded her to try again with his orchestra.Footnote 38 The visit concluded with a contract, which Damrosch “probably then and there, wrote out in longhand” (Figures 3a and 3b; see Appendix 1 for a transcription).Footnote 39

Figures 3a–b Contract dated October 10, 1908, written by Walter Damrosch, engaging Isadora Duncan to dance with the New York Symphony Orchestra. Box 25, folder 3, Walter Damrosch Papers, Music Division, New York Public Library.

Damrosch hastily booked the Metropolitan Opera House for their first concerts on November 6–7, 1908. Fearing another failure, Duncan arranged preemptive passage to Europe for the following day, later writing that she had decided to flee if she did not succeed.Footnote 40 Instead, she received the ovations of a sold-out house and the satisfaction “of winning the approval of my own people at last.” “I think I convinced them I was not a Salomé dancer or a barefoot-dancer or anything of that kind.”Footnote 41 Heartened by this success, Duncan traveled with the NYSO to Boston on November 11 and then on to fifteen concerts in eight other cities, finishing in Hartford on December 30. The artistic and financial success of this tour gave Duncan a foothold in the United States and brought wide-eyed new audiences to the NYSO (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Advertisement for Duncan-Damrosch concert in Musical America, November 14, 1908.

Figure 5. Program booklet for Duncan-Damrosch performance at the Metropolitan Opera House, undated. Dance Clipping File, box 1, folder 1, Irma Duncan Collection of Isadora Duncan Materials, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library.

Aside from their commercial potential, the Duncan-Damrosch tours fit a pattern of steps Damrosch proudly took to support art forms struggling for status in the development of US culture.Footnote 42 A 1911 press release edited in Damrosch's hand advertises his plan for Duncan in tones of unabashed heroism. New Yorkers, he says, had “rubbed their eyes with astonishment” two years earlier when he offered “to give the support of his name and orchestra to combine with a dancer.”Footnote 43 His support for Duncan has added “another debt of gratitude to the many which the American public owes him for increasing their perception of art in its many phases.” Another press release announces their collaboration as “a daring but magnificent effort to raise the art of dance to the highest level and on a plane with music and sculpture.”Footnote 44

Some critics applauded Damrosch's courage. Distant San Franciscans read that the Metropolitan Opera House was packed for Duncan when “ten years ago you couldn't have persuaded a ‘corporal's guard’” to attend such an event.Footnote 45 And the reason for this “apparent mystery?” Walter Damrosch had “expressed his approval of the idea . . . by consenting to direct the music.” If Mr. Damrosch “did not think it blasphemy to play Beethoven for her, possibly there was something in the idea of treating a thing like dancing as if it also were an art.”Footnote 46 The reviewer for a concert in Philadelphia declared that here “was the real opportunity for setting dancing to music, and both were of the exquisite sort calculated to carry the soul beyond the human realm.”Footnote 47 Indeed, for Duncan, the opportunity to work with Damrosch was, as Martin writes, “a sudden benediction.”Footnote 48 Duncan openly credits her initial success in the United States to Damrosch, fondly recalling their meeting after he had seen her dance at the Criterion, and his vision for her dancing “when inspired by his own fine orchestra and glorious conducting.”Footnote 49

Yet the rescue went both ways. As a champion of women's rights, the physical culture movement, and the validity of dance as a serious art, Duncan helped shape a revolution that transformed the landscape of opportunities for future generations of dancers and composers. Particularly her insistence on dancing to concert masterworks cleared a path for the remarkable output of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and its offshoots. The explosion of modern dance and choreography in the twenties and thirties all owed a more serious artistic and especially musical footing to Duncan's innovations.Footnote 50

A Calculated Risk

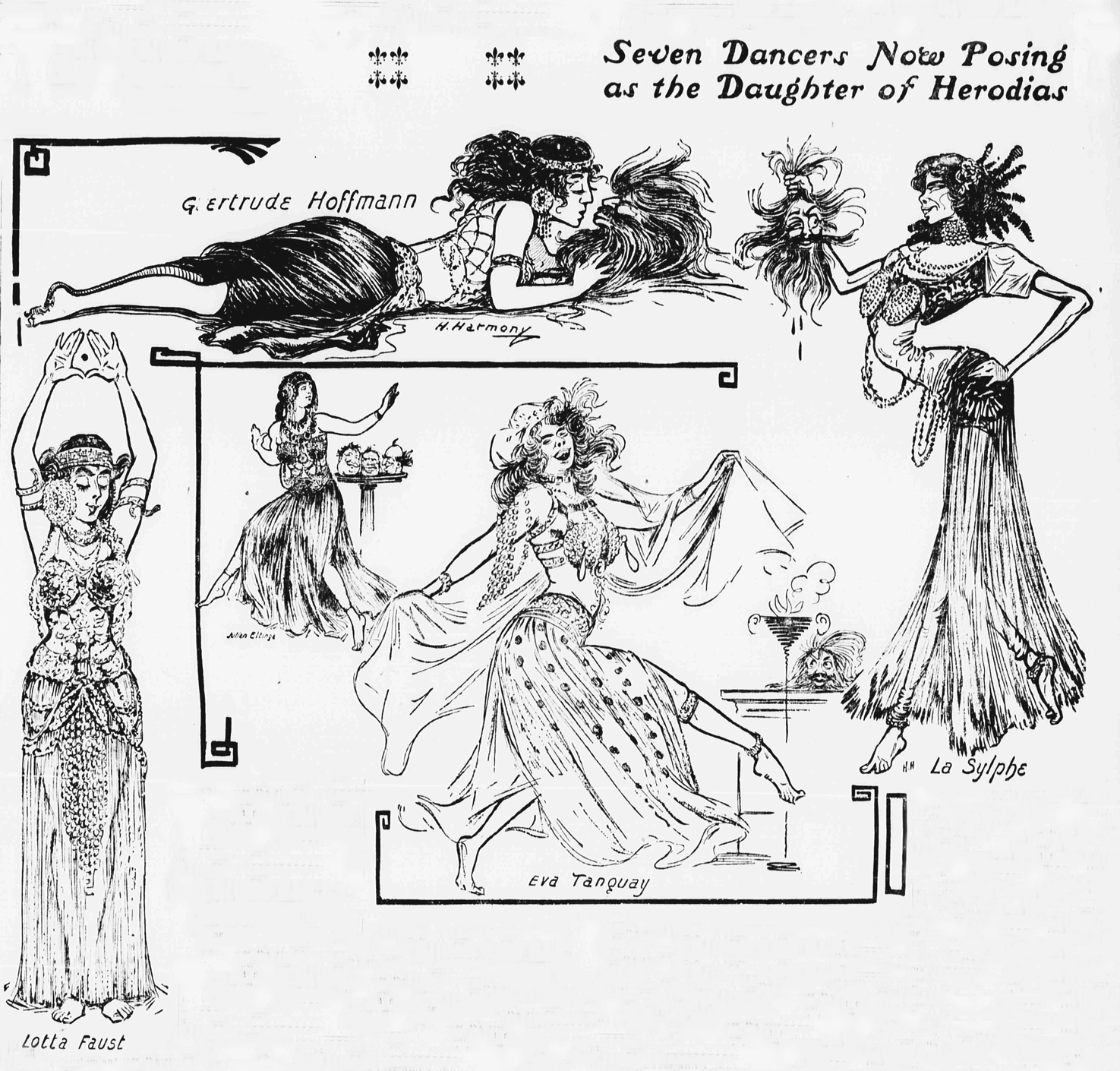

Despite his record of innovative programming and his confidence in Duncan's promise of increased earnings, Damrosch had the most to lose in the gamble. “A failure would bring out in force all his enemies,” according to his biographer George Martin, “and even a success would mean controversy, for . . . many musicians and music lovers abhorred the idea of using Schubert or Beethoven to accompany dance.”Footnote 51 Damrosch received praise in some quarters for being, as one reviewer put it, “the first musician of note to give substantial proof of his interest in Miss Duncan's genius.”Footnote 52 Yet many critics dreaded the effects of such an alliance, especially in the midst of the Salomé craze. Whether remarking on their differences or similarities, countless comparisons of Duncan and the Salomé dancers securely bound them as a dual phenomenon and cast an ominous shadow over Damrosch's high-minded experiment. As the profane counterpart to Duncan's chaste, healthy, natural style of dance, a proliferation of Salomé dancers instead represented, as Mary Simonson has noted, “a (foreign) transmittable disease that threatens American ‘values’ and traditions” (Figure 6).Footnote 53

Figure 6. “Seven Dancers Now Posing as the Daughter of Herodias,” Evening World, August 8, 1908. Caricatured are Gertrude Hoffmann, La Sylphe, Eva Tanguay, Julian Eltinge, and Lotta Faust.

Dangerous and deviant on multiple levels, Salomé's veil of literary respectability joined the seven she flung off as she wriggled her way from the high arts to vaudeville to become a symbol of perversion and sexual pathology.Footnote 54 Indulging popular tastes for the risqué that Duncan refused to countenance, Maud Allan's pantomimic enactment of Salomé's lust for the severed head of John the Baptist pulled all the ghastly, vivid stunts the public clamored for. The same New York that had “raised its hands in holy horror” over the Met's opera production of Salome was now, as critic Charles Darnton writes, clamoring for this “unblushing sisterhood” managed by high priests of sensationalism who “know how to minister to the needs of the box-office” in the name of “a little capital A talk about Art” (Figure 7).Footnote 55 Indeed, a cautionary tale from Columbus warns that “Salomé dancers have had their day in this city,” and while audiences “made the excuse” that they wanted to hear Damrosch's music, “as a matter of fact Isadora Duncan . . . was the real drawing card.”Footnote 56 A New York Sun reviewer ominously asks how long it will take “for this public to become so interested in the interpretation of Beethoven . . . by a dancer that the efforts of a mere conductor and his orchestra will not appeal to them?”Footnote 57 Damrosch's contribution to the concerts often appears a mere closing afterthought: “Mr. Damrosch and his orchestra . . . were delightful throughout”; the beautiful tones of the orchestra “added much to the enjoyment of the evening”; Mr. Damrosch and his orchestra “are again the accompanying body.”Footnote 58

Figure 7. The Boston Herald caricatures a censor banning Richard Strauss's Salomé for stodgy opera-goers as a lower class crowd rounds the corner to see a Salomé dancer at the 10-20-30 Burlesque, a venue named for its range of low ticket prices. “The ‘Salomé’ Situation in Boston,” Musical America, April 10, 1909.

Critics also came to Beethoven's defense. A St. Louis reporter complained that Damrosch's orchestra was “futilely dominated” and made “pitifully subordinate” by “an irrelevant and impertinent dancing girl,” such that “we lose our Beethoven in order to gain our Isadora Duncan.”Footnote 59 Pittsburghers read that “the great master of all the symphonic writers was forgotten last evening, while the eye was enchanted. . . . It was Miss Duncan, not Beethoven, in whom they were interested.”Footnote 60 Even Damrosch was piqued by Duncan's popularity, as we read in his correspondence with Wynn Coman, who was to manage the spring 1910 tour that Duncan ultimately cancelled. Strongly emphasizing demand for Duncan in the south and northwest and the lucrative bookings already secured there, Coman consoles Damrosch on being “the tail to Duncan's comet,” yet reminds him of previous engagements where “it took something sensational to make the house go big.”Footnote 61

Damrosch was apparently of two minds about Duncan. His daughter Gretchen relates that “he would watch her across the footlights, enraptured, and then she would come to the house and he and my mother would become rapidly unenraptured, almost frantic,” for although the dancer was a formidable artist, as a person “she was a goose,” and her manner of speaking was “almost idiotic.”Footnote 62 A further picture of awkward intimacy emerges in the biography of Damrosch's concertmaster and brother-in-law, David Mannes, who recalls Damrosch reluctantly accompanying at the piano while Duncan danced for dinner guests at his home with the furniture removed, lights dimmed, and fascinated guests seated on the floor.Footnote 63

Despite any private reservations, Damrosch produced a campaign of public admiration for Duncan. His affable reply to a patron who objected to Duncan's Seventh Symphony claims that each repetition of her performance only served to deepen his convictions about Duncan. He considers the daring nature of his experiment with Duncan a complete success, “fitting and beautiful. . . . The stage should be filled with twenty Duncans, but alas, so far our age has produced only one.”Footnote 64 His public statements were no different. If the Minneapolis Star Tribune can be believed, Damrosch disembarked from the tour train to exclaim that Duncan's dancing “is the most intensely interesting thing in art that it has ever been my good fortune to witness.”Footnote 65 In Pittsburgh, Damrosch again assured skeptics: Her interpretation of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony is “a revelation” and “as exquisite as the symphony itself.”Footnote 66 Genuine or not, his public stance on Duncan seems designed to distance her from Salomé dancers like Maud Allan, whose enviable earning power he nonetheless coveted.Footnote 67

Managers and Profits

Damrosch's reach for new audiences becomes clear in his dealings with the concert mangers he relied on. Pleased with the success of their 1908 concerts, Damrosch arranged for Duncan to return to the United States in 1909, anticipating, as he wrote to her agent in Europe, that it would generate a windfall of profits.Footnote 68 They presented several concerts in New York before embarking on another tour of the Midwest with bookings entrusted to R. E. Johnston, who traveled to Europe in June 1909 to make business arrangements “with a number of his old stars and make contracts with new ones.”Footnote 69 Johnston auditioned more than sixty new vocalists and instrumentalists, and met with Duncan to settle details of her engagements with Damrosch.Footnote 70 He also visited Maud Allan to draw up a contract for her US tour the following year—the one Damrosch scornfully refused to conduct.Footnote 71 As the middle man for a vaudeville dancer, numerous star soloists, and two orchestras, Johnston intervened in several overlapping categories of US artistic life, making clear the role these managers played in the creation of middlebrow US culture and the hand of business in bringing “sacred” art to a mass public.Footnote 72 According to a feature article in Musical America, Johnston and his fellow New York managers, following a business model devised by the captains of the vaudeville circuit, were “the happiest and at the same time the busiest” of New Yorkers as they prepared to “sell concert stars” to local musical enterprises “from one end of the country to the other.”Footnote 73 While Loudon Charlton was “up to his ears” booking a ninety-concert tour for soprano Marcella Sembrich (gross receipts of $300,000 expected), and Haensel and Jones managed the NYSO's spring tour and a stable of star soloists, R. E. Johnston readied his new Broadway office suite to manage “three concert companies, two orchestral tours, ten singers, four violinists and three pianists.”Footnote 74

Where Damrosch put his faith in music, Johnston put his in the box office, declaring it “the only thing that counts in this country.”Footnote 75 No matter how great the artist, “if he doesn't draw the money then he is no good, and vice versa. First it's the advertisement, then the artist must ‘make good,’ then the public will flock to hear him.” As for Duncan, Johnston believes her popularity rests on her novelty, “and that is what people want.”Footnote 76 Like a midway huckster, Johnston brashly affirms his commercial interest in the Duncan-Damrosch tour. “I am in the business to make money, so I have to have something different, and Miss Duncan gives it to them.” Having filled every date for their fall tour, Johnston believes Duncan will “make a bigger success than last year even, for now people are talking about her.”Footnote 77 His brazen entrepreneurialism easily matches Damrosch's anticipation of “A Great Deal of Money!” but conspicuously lacks the conductor's show of respect for Duncan's art. Any effort to balance profits with Kunstreligion fell solely to Damrosch.

The 1909 tour began October 8 in Albany and concluded in Providence on December 4, stopping in twenty-two cities in the East and Midwest. Damrosch expressed optimism at the outset, particularly in regard to potential earnings. He wrote to his wife that “staid old Toronto woke up” for Duncan's beautiful dancing. So far, the profits were fair, and he expected “much bigger receipts” to come.Footnote 78 But tensions quickly arose. Duncan was pregnant with her second child, fathered by Paris Singer, and had backed out of her commitment for a spring tour of the western states.Footnote 79 Furthermore, the success of the previous year's concerts had emboldened Duncan, whose increasingly capricious demands began to wear on Damrosch. In Columbus, for example, Duncan balked at the looks of the stage at Memorial Hall and refused to dance. With four thousand seats sold to capacity, managerial pleas and even threats were to no avail, and a hasty relocation to the Southern Theatre ensued. “One thousand five hundred people saw Isadora do the Grecian ‘pas-ma-la’ and 2,500 got their money back.”Footnote 80 A week later, Damrosch wrote to his wife that he was “tired of the whole thing” and would be “quite happy when Dec. 2 comes around.”Footnote 81 By the end of October 1909, he admitted that he was “thoroughly disgusted” not only with Duncan but with Johnston as well. “He is an absolute incompetent. Our profits on this tour should have been $5000 more but for his negligence and ignorance.”Footnote 82

Music Critics

To make matters worse, Damrosch endured a barrage of criticism over Duncan. Certainly aware of her “profanation” of Beethoven in Germany, Damrosch expected trouble, writing to his wife just weeks before the 1908 tour began with thanks for her optimism. “I am much relieved at what you write about Duncan. I was getting a little nervous at my own ‘courage.’”Footnote 83 The New York Times captured critics’ general contempt for Duncan's dancing to the Seventh Symphony, citing her failure to demonstrate “that the music has spoken insufficiently for itself during the hundred years or so of its existence.”Footnote 84 Another reviewer concluded that “anyone may girate [sic] to Beethoven's music,” but her aim to interpret Beethoven invited “serious consideration of the question.”Footnote 85 Dancing to Chopin may be tolerable, he writes, “But dancing Beethoven! Hardly.”Footnote 86 In 1909, Carl Van Vechten protested “the perverted use of the Seventh Symphony,”Footnote 87 while a St. Louis critic called it an “overwhelming example of feminine vanity and insolence.”Footnote 88 The world's “craze for something new” can never justify “such an act of artistic sacrilege. It is a sin.”Footnote 89 Yet while critics grumbled, audiences roared for more. A reported thousand people were turned away from a concert in Philadelphia's Academy of Music.Footnote 90 In Washington, with President and Mrs. Roosevelt in a private box, Duncan and Damrosch received “one of the biggest ovations that has been accorded an artist in the National Capital for a long time.”Footnote 91

Whether reviews were friendly or hostile, they sold tickets, and Damrosch wagered on another tour in 1911—their last—that brought him face to face with an especially zealous opponent in New York Tribune music critic Henry Krehbiel. Rivaling von Bülow as a musical purist, Krehbiel had no sympathy for Duncan's reach “outside her province,” and seized an opportunity to harass Damrosch over his bungled introduction to Duncan's new Wagner program.Footnote 92 Damrosch had planned to perform the Finale from Tristan and Isolde (Liebestod) without Duncan. At their opening concert, however, he took the stage to explain a program change. First hailing Duncan's role in a “long leap upward and forward” for the art of dance, he then announced that she had modestly requested just the day before to show him her studies to Wagner's Liebestod, and that he believed them worthy of a chance to be seen.Footnote 93 Next came a startling caveat. “As there are probably a great many people here to whom the idea of fitting pantomimic expression to the Liebestod would be horrifying, I am putting it last on the programme, so that those who do not wish to see it may leave.”Footnote 94

This announcement produced an embarrassing uproar that spilled to the Evening Sun and Evening Post.Footnote 95 Krehbiel accused Damrosch of an underhanded publicity stunt, for news of Duncan's plan to dance the Liebestod had in fact been leaked days earlier. The ploy, Krehbiel wrote, could not have been “more deftly devised to pique curiosity and compel everybody to stay.”Footnote 96 The public scolding from Krehbiel likely brought Damrosch to the limit of his interest in Duncan, for he never engaged her again and makes no mention of her in his memoires.Footnote 97 Furthermore, by 1911 he had also weathered a series of attacks from a second group of opponents to his work with Duncan: more traditional spokesmen for the sacred who manned the pulpits of US Protestant churches.

Damrosch and the Social Gospel

The clergy's objections to Duncan came from both sides of what Martin Marty has called “two-party Protestantism,” which divided on whether salvation was best carried out on a social or personal basis.Footnote 98 On one hand, educated liberal proponents of the social gospel railed against Damrosch's failure of artistic faith. On the other, the itinerant revivalist Billy Sunday entered the fray to attack dancing in general and Duncan in particular. Both branches of Protestantism ironically adopted promotional tactics familiar to Damrosch as they too struggled to adjust their own sacred missions to a new age of consumerism and popular entertainment.

Seminary-educated proponents of social reform—influenced by Charles Darwin and the progress of science—responded to the plight of the urban working class in what became known as the social gospel movement. Leading social gospel exponent Walter Rauschenbusch insisted that the internal crisis of the individual must be seen in connection with the rampant industrialism and commerce that had obliterated old forms of communal organization.Footnote 99 “The dominant concern is to get profit, and to invest it to get more profit. In its main riverbed the current of business has become a torrent.”Footnote 100 In this line of Protestant liberalism, the Methodists’ 1907 Social Creed of the Churches aimed to temper personal vice, including dancing, by attacking the “practical industrial problems” of the modern city.Footnote 101

Yet rather than the urban laborer championed by Rauschenbusch, Damrosch directed his Kunstreligion to the spiritual deficit of the laborer's capitalist exploiter, deftly turning the social gospel to the upper class victims of the United States’ “most sacred shrine of business.”Footnote 102 In a 1910 address titled “Music and the Americans,” he considers the effect of Progressive Era business practices on men “overcome by the race to develop the resources of America.”Footnote 103 The pressure of competition, “the perpetual harping on the one idea of business, of desire for wealth, or feverishly developing the resources of this country, has gradually become that dreadful modern product, ‘The Tired American Business Man.’” For his “salvation,” Damrosch exhorts wives to revive their husbands’ flagging spirits with chamber music.Footnote 104 After the performance of a Beethoven trio in his quiet home, Damrosch predicts, the “T.B.M.” will see the world in a new light. To better reach those worn down by industry on their day of rest, Damrosch publicly opposed Sunday Blue Laws, arguing for legislation to legalize concerts on Sundays. He “held the vast crowd spellbound” in his 1907 appeal to the New York Aldermanic Committee, declaring, “It is given to none to encompass God. . . . There are those who seek their God in Shakespeare, and others who see him in the sonatas of Beethoven. . . . We claim the right as American citizens to celebrate our Sunday as we wish.”Footnote 105 The Sunday afternoon concerts that he instituted proved a vindication: “[M]y faith was justified, as not only were these concerts attended by huge audiences, but the percentage of men was greater than had ever been seen at symphony concerts before.”Footnote 106

Trouble in St. Louis

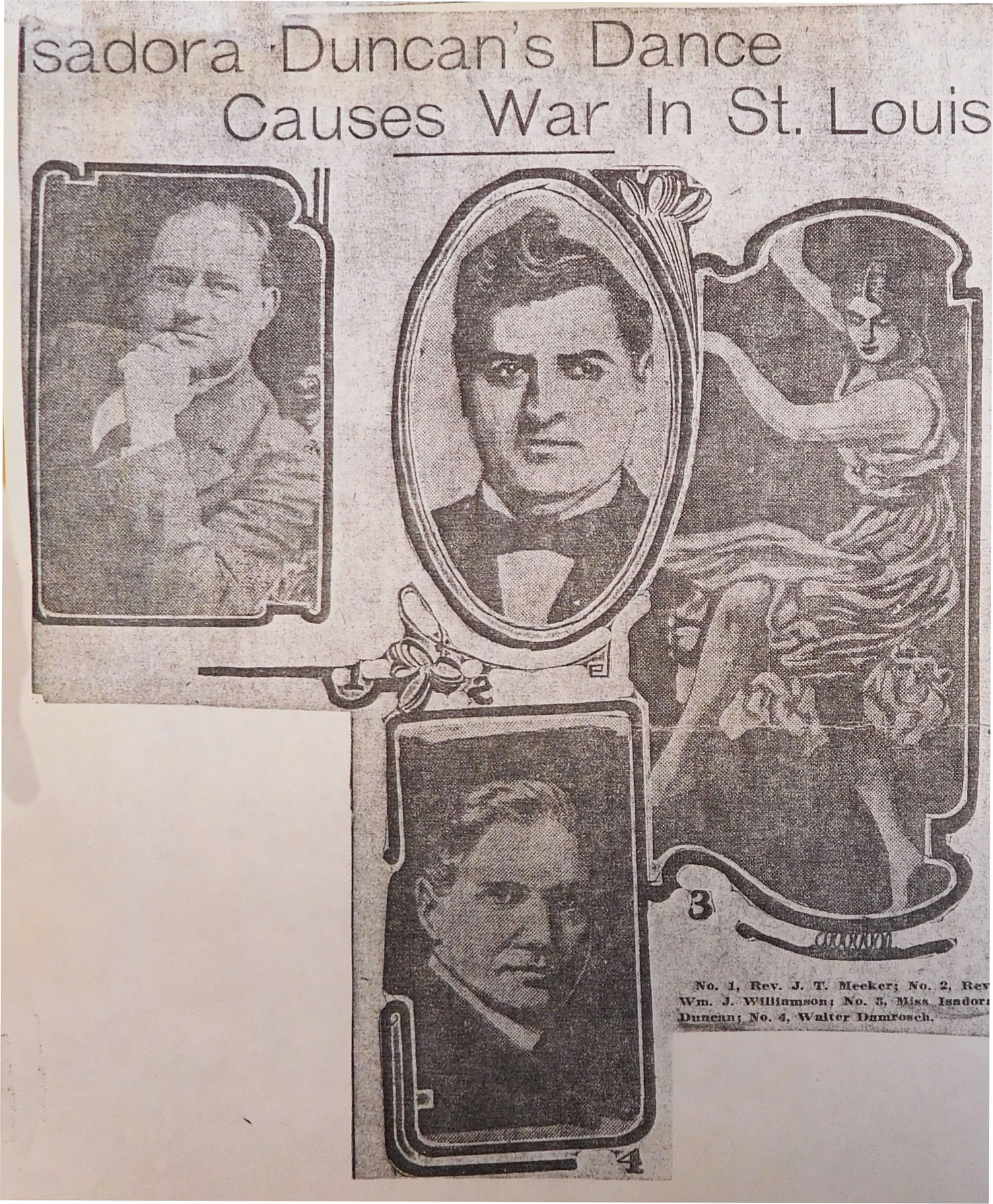

The message of social redemption that Damrosch loosely shared with mainstream Protestant clergymen unraveled over Duncan's dancing on the 1909 tour stop in St. Louis, where the audience “was wrought to a high pitch.”Footnote 107 One account notes that the Coliseum “rang with cheers and ‘bravos,’ which Miss Duncan and the orchestra shared alike.”Footnote 108 Yet in a vesper service the next day, the Rev. Dr. Fayette L. Thompson, pastor of the Lindell Ave. Methodist Episcopal Church, responded with a “scathing denunciation,” in which he “heaped coals of fire” on Damrosch for presenting dancing as “high art.”Footnote 109 Duncan's shameful exhibition was all the worse, Thompson cries, because “the excuse for it all is art, high art; as though art could consecrate nastiness.” Thompson demands a more vigorous protest of Duncan's bare legs. If the “good women and clean men” of his congregation fail to “stamp such an exhibition with utter and absolute condemnation,” what will become of the more common folk “who throng . . . the cheaper theaters and places of amusement” to their “perpetual and mortal moral peril?”Footnote 110 Such concern for the fate of the “common folk” places the burden of salvation on those in a position to provide moral guidance, Damrosch included. Damrosch replied to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, defending Duncan's Seventh Symphony as “a valuable and noble experiment.”Footnote 111 Yet his rebuttal sat atop a lengthy article quoting the many letters and telephone calls Thompson had received praising his stand against Duncan. One writer recounts that he was enticed to see Duncan only because she appeared under the auspices of the Damrosch Orchestra. Instead, he observed “an insult to all civilization.”Footnote 112 Others saw “a fearful menace to society” and “a pollution of all concerned.”Footnote 113

Churches across the country joined the St. Louis campaign against Damrosch and Duncan. A report from the Boston Herald tells of a further twenty-four pastors of the Methodist Episcopal Church who adopted a resolution against Duncan. It begins,

Resolved—It is a matter of exceeding regret that in the name of charity and before an audience of character and culture, and excused only by being high art, a woman clad only in a kirtle, slitted to the belt, of a fabric so diaphanous that to certain changing phases she was virtually naked, . . . has been permitted to appear. Such a performance, whatever the motive, is the grossest violation of the proprieties of life.Footnote 114

In Pittsburg, “a protesting bevy of Sunday-School teachers” out to safeguard a “morally lethargic world” demanded to know if Duncan would appear in bare feet.Footnote 115 In response, an Iowa reporter noted the irony of this prudery “worth thousands as a well written advertisement.”Footnote 116 Owing to the moralist's outrage, “no room in that big city” was large enough to hold the Duncan throngs (Figure 8).

Figure 8. “Isadora Duncan's Dance Causes War in St. Louis,” Kansas City Post, November 5, 1909. Isadora Duncan Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library. Pictured are the Reverends J. T. Meeker and Wm. J. Williamson along with Duncan and Damrosch.

The controversy gathered more steam when a band of nineteen St. Louis society women rallied for Duncan. The Post-Dispatch printed their opinions, each defending the purity of Duncan's beautiful dancing.Footnote 117 Yet Thompson persisted, arguing that on the low variety stage or in the St. Louis Coliseum, “vice is vice” with only one difference, “that the more pernicious of the two is that in the more influential place.”Footnote 118 He assigns Damrosch, a trusted figurehead of that “influential place,” equal blame for this collapse of common decency.Footnote 119 Thompson further folds Beethoven's music into the moral failure. It is a shame on St. Louis, he writes, that in its midst an elite orchestra “should consent to be merely a background for plain and ill-disguised nudity; that Beethoven's stately symphony should be so degraded.”Footnote 120 Thompson's response makes clear the bonds of art and religion that allowed mainstream clergymen to fuse high art to scripture as a bulwark against the brothel, the bar room, and the gaming table.Footnote 121 Whether such uplift could include dancing was the question Damrosch posed with Duncan. In St. Louis, the answer was a resounding no.

Billy Sunday, Itinerant Preacher

In his mission to bring concert music to the rural United States, Damrosch also shared a spiritual affinity with the second broad strain of Protestantism advanced by itinerant evangelists who rejected the social gospel, preferring instead to go straight to the sinning soul. These wandering preachers took the work of frontier evangelists from the Second Great Awakening into the modern city in a third wave of Protestant conversion. Damrosch's determination to penetrate “into regions where symphonic music was not yet known” had an equally fervent mission of conversion.Footnote 122 Emulating von Bülow's ambitious touring, and following Theodore Thomas's business model, Damrosch crisscrossed the United States with his orchestra to bring the “revelation” of symphonic music to small midwestern towns that would rarely have heard it otherwise.Footnote 123 He ministered tirelessly to remote communities as he penetrated “deep into musically virgin territory, playing Beethoven in the provinces, Mozart in mining camps and Wagner in the wilderness.”Footnote 124 The exuberant exclamations of a Fargo cowboy who wandered into a concert, the humble thanks of a sheepherder “from nowhere”: these were the testimonials that made Damrosch most proud of his musical pioneering.Footnote 125

Damrosch parted with the revivalists, however, on the matter of dancing, which exemplified for them the moral crisis threatening small town and modern city alike. Preachers wary of the newly unchaperoned working woman, free to spend her leisure hours in popular amusement, honed what Ann Wagner calls “a rhetoric of moral panic” to denounce “the new woman, the new dances, and the new dance institutions of the era.”Footnote 126 Revivalist Samuel Porter Jones, for instance, warned that a lady could not be a Christian and dance any more than a man could be a Christian and play cards.Footnote 127 A tract by “fervent exhorter” Milan Bertrand Williams, titled Where Satan Sows his Seed, issued “Plain Talks” about the evils of modern amusements, especially dancing. “The most accomplished and most perfect dancers are to be found among the abandoned women. Why? Because they are graduates of dancing schools.”Footnote 128 Of two hundred women he spoke to in brothels, Williams claims that 163 of them were ruined by dancing.

Among the most dramatic and celebrated of the urban revivalists was preacher Billy Sunday (1862–1935), who came to figure in the St. Louis uproar over Duncan. The hardscrabble orphaned son of a Union soldier, Billy Sunday played outfielder for the Chicago “White-stockings” before turning to the pulpit. Drawn to the church by a Chicago rescue mission band, he quickly moved from sporting star to full-time preacher by way of the YMCA, leading prayer meetings for the urbanites he had once entertained on the ballfield. By 1901 he could afford to have enormous wooden tabernacles constructed to seat thousands wherever he went, and by 1906 pictures of Sunday in “striking attitudes” appeared regularly in the press.Footnote 129 A brash figure in the Third Great Awakening, Sunday railed against Darwinism, scientists, intellectuals, and the liberal Protestants whose “new naturalism” led them to tolerate the New Woman's love of the Charleston. Sunday peppered his sermons with dire warnings about dancing: “The dance is the moral graveyard of more girls than anything else in the world.”Footnote 130 Worse yet, “Seven million girls go wrong in a century in this country, and three fourths of them are ruined by the dance.” Even more damning, “Sisters! If you countenance the dance you are your sister's murderess.”

Selling tickets to a mass audience by fostering an air of celebrity while simultaneously promoting himself as an agent of salvation, Sunday embodied another twist in the thread of mass entertainment that laced spiritual uplift into commerce and marketing. As Scott Anderson has shown, Sunday capitalized brilliantly on the “gross materialism of [his] day . . . and the pleasure-seeking mania of all classes of society,” using promotional gimmicks and personal magnetism to bring individual sinners to salvation.Footnote 131 His outlandish preaching style, aggressive business practices, and attacks on a “feminized” Victorian ministry for its weak response to sin made him a regular feature in the press. With the skill of a P. T. Barnum, Sunday made God a mere “silent partner in the big evangelistic corporation of which ‘Billy’ is boss and manager.”Footnote 132 Indeed, with a former Barnum and Bailey circus giant acting as chief usher in his tabernacle, Sunday's openly theatrical revival meetings became “a powerful competitor of secular amusements even in the largest cities.”Footnote 133 The Atlanta Constitution reported that twelve thousand people at a Billy Sunday revival “enjoyed one of the most sensational entertainments ever given . . . as they listened to Billy Sunday denounce the amusements of the day.”Footnote 134 One critic called his preaching “the most brazen-faced commercialization of religion the world has ever known,” a charge Damrosch also faced, albeit in subtler tones, from the likes of Henry Krehbiel.Footnote 135

Conducting, Preaching, Dancing

Not surprisingly, Sunday and Damrosch courted similar audiences and resorted to similar tactics in the process. Both employed the theatrical syndicate's business model to organize and consolidate opportunities at each tour stop. On Damrosch's tours, the general plan was to have the press agent and advance man organize three-day festivals with a local chorus taking part in oratorio or opera excerpts, thus boosting ticket sales. On a grander scale, Sunday's advance men spent months preparing a city for his arrival. Sunday and Damrosch also mobilized their personal charisma with the captains of capitalism. Sunday's outspoken support of industrial progress in the United States and his disdain for social reforms benefiting workers earned him the endorsement of John M. Studebaker and John D. Rockefeller, Jr., among many others.Footnote 136 Damrosch likewise devoted tremendous energy to the same small group of industrialists in a relentless effort to balance his ledger.Footnote 137

The web of similarities grows from there. In language typical of its time, both Sunday and Damrosch warned of feminine influence over their respective endeavors. Sunday's Muscular Christianity pugnaciously battered a feeble Victorian Protestantism within the broader YMCA movement in order to realign rugged character with moral and spiritual righteousness. A Christian, he railed, cannot be “some sort of dishrag proposition, a wishy-washy, sissified sort of galoot, that lets everybody make a doormat out of him.” Instead he must be “the manliest man” who will acknowledge the kind of Jesus Christ who could “go like a six-cylinder engine.”Footnote 138 Damrosch, despite his advocacy for women's suffrage, complained that the art of music in the United States was overrun by women. If the four million inhabitants of New York include only a paltry fifty thousand who may be considered musical, he wrote, and at least forty thousand of these are women, “we can hardly claim as yet to be a musical people.”Footnote 139 The American man looks on music “as something foreign, something like an accomplishment, which his wife and daughters can acquire . . . but too effeminate for his sons.”

Most ironic of the similarities between Damrosch and Sunday was the masculine physical exhibition each employed to advance their cause. As male public figures, Sunday and Damrosch had privileged access to a culturally sanctioned gestural vocabulary appropriate for rhetorical delivery in the masculine sphere. Along with lawyers and politicians, ministers were trained in a “male-coded” tradition of oratory, employing the rigorous gesturing of actio considered unbecoming of women.Footnote 140 Sunday punctuated his preaching with a melodramatic movement repertoire—popularized in the very entertainment venues he loathed—in order to draw lost souls into his revival meetings and down the “sawdust trail” to redemption and the offering plate.Footnote 141 His theatrical charades rivaled those of Maud Allan in entertainment value. Yet in the rhetorical sphere he shared with Damrosch, Sunday's spiritual gymnastics were interpreted as a passionate display of religious fervor.

The same could also be said for the gesticulations employed in conducting. Despite his studied reserve on the podium and his public portraiture of contemplative calm (Figure 9), Damrosch's cultural authority was visible to the public in a movement practice that had little to separate it from Duncan's dancing, putting him at but one remove from the suspicions she provoked, yet still confirming the irreproachably masculine, generative nature of his work. Indeed, Damrosch's position as a quasi-spiritual agent of musical sound gave him a cultural status very different from that of a dancer, whose more reactive relationship to music accorded well with notions of female passivity and sensuality.Footnote 142 Furthermore, the transcendent inwardness engendered by an implicitly intellectual and patriarchal Kunstreligion shielded him from the suggestion of feminine sensuality, and thus immorality, faced by Duncan. Lindal Buchanan has shown how a “feminine” delivery style required Victorian-era women to employ indirect influence through “conversation” rather than oratory, and to seek access to the public domain through their husbands and fathers.Footnote 143 Within these social norms dictating verbal and physical restraint for women outside the domestic realm, Duncan's gestural art had the advantage of silence, but needed the imprimatur of Damrosch's protection to authorize her respectable visibility in public, and especially in the concert hall.

Figure 9. “Walter Damrosch, 43 years ago,” George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

As Damrosch's conducting guided a male-centered sacred repertoire, Sunday's dramatically animated showmanship and stage calisthenics exemplified the Muscular Christianity that aimed to revitalize the fight against all manner of sins.Footnote 144 In this new vein of Protestantism, Sunday disrupted more genteel conceptions of the sacred to reach a wider and more spiritually imperiled audience. Vivid enactments of stories from scripture gave his sermons a respectably male mimetic kinship to vaudeville pantomime and melodrama. “He skipped, ran, walked, bounced, slid and gyrated on the platform.”Footnote 145 And despite his railings against scantily clad dancers, his own sensationally dramatized sermons included a renunciation of garments not so different from Salomé's fabled shedding of the seven veils.

Gradually, he would shed his coat, then his vest, then his tie, and finally roll up his sleeves as he whipped back and forth, crouching, shaking his fist, springing, leaping and falling in an endless series of imitations. He would impersonate a sinner trying to reach heaven like a ball player sliding for home. . . . Every story was a pantomime performance. Naaman the leper, washing himself in the Jordan to cleanse away his sores, was reproduced with extravagant vitality by the evangelist, who would stand shivering on the bank, stub his toe on a rock, slap sand fleas, shriek with cold at the first plunge, and blow and sputter as he emerged from each healing dip.Footnote 146

By 1909, Sunday's “Corybantic Christianity” was legendary (Figure 10).Footnote 147 “He ‘snuffs the coke’ or ‘jabs the needle’ and lops over the pulpit. . . . He gulps poison, writhes in agony and stiffens out dead on the floor. Up he springs, . . . one foot on the chair and the other on the pulpit. . . . No posture is impossible for this versatile go-getting Gospel gymnast.”Footnote 148 Sunday's music director Homer Rodeheaver describes one of his sermons: “To the more than 25,000 persons [in attendance] Billy Sunday was a whirling dervish that pranced and cavorted . . . and left them thrilled and bewildered as they have never been before. Sensational? Of course.”Footnote 149

Figure 10. Billy Sunday, as featured in the Billy Sunday Revival Supplement of the Richmond Palladium. “Noted Evangelist Snapped to Show Poses When in Action in His Campaign to Save Souls,” Richmond Palladium, April 25, 1922.

With these accounts in mind, we can plausibly link Sunday's outlandish stage antics to those of Maud Allan and perhaps even Duncan, for dancer and preacher alike had introduced the exposed moving body into social spaces of reverence that previously commanded stillness. And indeed, papers across the United States ran reports linking the St. Louis outcry over Duncan and Damrosch to the activities of Billy Sunday. The story began with the St. Louis ministers debating whether their womenfolk would be offended by “Billy's way of getting fresh air.”Footnote 150 The Rev. S. E. Betts gleefully argued that if the ladies enjoyed and approved “the dancing of Isadora Duncan in a curtain only,” they should not object “to looking upon the Rev. Billy Sunday in negligée.”Footnote 151 He is, after all, “a well set up man” with “fine artistic proportions” better enjoyed with his coat off. Perhaps if he could be induced to appear in a curtain, “he would ravish the sense of the ultra-artistic.”Footnote 152 A further editorial titled “Isadora Duncan as a Teacher” mockingly credits her for liberal progress in the Methodist ministry, claiming that though their aims are only remotely related, “Billy Sunday is an artist in his line, as is Isadora Duncan in hers.”Footnote 153 Deeply implicated in the raillery, Damrosch thus found himself at the center of a ruckus in which preachers, dancers, strippers, and hucksters all traded places, and the pleasure-seeking masses drove any bargains made in the process.Footnote 154

Sunday and Damrosch were both shrewd managers of their respective spiritual enterprises, strategically borrowing elements of popular entertainment to attract and hold new adherents. Apropos of their differing motives and messages, their opinions of dancing went in dramatically different directions. Where Damrosch coveted the public's interest in dance and banked on its potential as an art form of uplift, Sunday howled against it. Yet if we accept Moore's precept that secularization “has to do not with the disappearance of religion but its commodification,” the kinship between Damrosch and Sunday becomes yet more focused.Footnote 155 Both, with the help of their managers, sold “religion” to the broadest possible audience with innovations that did not so much desacralize as resacralize their message for a mass public. Whether from the podium or the pulpit, each shrewdly sacrificed Durkheim's exclusive conception of the sacred in order to entice the modern consumer.

The commercial incentives for hiring a dancer are clear in Damrosch's 1909 missive to Schultz. Yet his persistent effort to feature a dancer in the face of equally persistent criticism suggests he also had motives less tied to the market. We see these reprised in a massive pageant—quietly acknowledged as a final tribute to Duncan—that Damrosch organized in the newly constructed Madison Square Garden in 1933 for the Musician's Emergency Fund.Footnote 156 This project began in November 1932, five years after Duncan's tragic early death, when Damrosch sought out her adopted daughter Irma to choreograph a “Pantomimic Pageant” to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.Footnote 157 Irma recalls Damrosch's conviction that her mother's dancing twenty-five years earlier “helped to open [his] eyes and mind to the significant connection between the art[s] of music and dance.”Footnote 158 In the end, whether his motives for the Duncan-Damrosch tours were mercenary or artistic, profane or sacred, his age made their mingling inevitable. In a thoroughly modern business move, Damrosch reoriented the sanctity of his concert organization to the tastes of a wider audience, wedding the popular dance craze to his high musical purpose to make orchestral music a more lucrative, yet still sacred force in the modern vaudeville age.

Appendix

Oct. 10/1908

Miss Isadora Duncan and Mr. Walter Damrosch hereby agree to give jointly at least two performances in New York.

I. All expenses are to be jointly born by the two parties including orchestra, hall rent, advertising, management.

II. All profits after deduction of all expenses are to be divided equally between the two parties.

III. Miss Duncan agrees to dance and Mr. Damrosch agrees to conduct the orchestra.

IV. Miss Duncan agrees to advance the sum of $150.00 towards expenses on or before Oct. 26th.

V. The dates of the performances are to be fixed by Mr. Damrosch between Nov. 6th and 18th 1908.