Locating a composer's notebooks or sketchbooks remains among the most thrilling discoveries for scholars interested in tracing the genesis of a particular work or the development of a compositional style. The importance of such a finding increases when it also allows for the reconsideration of larger historical narratives. Henry Cowell's notebook devoted to “dissonant governed counterpoint” is one of eleven counterpoint notebooks contained in Box 31 of the Henry Cowell Papers at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Although the discovery of this source is significant for many reasons, four in particular stand out. First, it provides information about the compositional method known as “dissonant counterpoint” (hereafter DC) during the earliest stage of its development in 1914–17, when Cowell studied at the University of California, Berkeley.Footnote 1 Second, the notebook confirms Cowell's active involvement in the early development of a technique that has heretofore been exclusively attributed to Charles Seeger.Footnote 2 Third, the document reveals Cowell to be a systematic thinker, which challenges existing biographical narratives of the composer as scattered and undisciplined. Finally, Cowell's notebook is situated at the beginning of his work with DC, which he also disseminated to others for nearly fifty years through his compositions, writings, and teaching. Thus, the Cowell archive, which was made available to the public in 2000, becomes a source for rewriting the historical record about both DC and Henry Cowell.

Dissonant Counterpoint: Definition, Development, and Legacy

The development of DC, a systematic approach to using dissonance based on subverting conventional contrapuntal methods, primarily involved the efforts of Charles Seeger, Henry Cowell, and Ruth Crawford. The compositional technique was one of many created during the early twentieth century, as composers searched for new musical resources. As a “reversal” of traditional contrapuntal methods, Cowell's and Seeger's descriptions of DC prescribed the use of chiefly dissonant intervals (seconds, sevenths, and the tritone); although consonant intervals were allowed, they should be preceded and followed by dissonances. In New Musical Resources (completed around 1919 and published in 1930) Cowell asserted,

The rules of Bach would seem to have been reversed, not with the result of substituting chaos, but with that of substituting a new order. The first and last chords would be now not consonant, but dissonant; and although consonant chords were admitted, it would be found that conditions were in turn applied to them, on the basis of the essential legitimacy of dissonances as independent intervals.Footnote 3

In the article “On Dissonant Counterpoint” (published in the same year as Cowell's book), Seeger explained,

The octave, fifth, fourth, thirds, and sixths were regarded as consonant and the tritone, seconds, sevenths and ninths, as dissonant. The species were as in the old counterpoint. The essential departure was the establishment of dissonance, rather than consonance, as the rule.Footnote 4

Although Seeger and Cowell participated in the initial development of DC from 1914 to 1917, Cowell's personal notebook devoted to “dissonant governed counterpoint” and a single loose-leaf sheet with the heading “Exercizes for Seeger” provide the only known manuscript evidence that documents the early development of the compositional method.Footnote 5 (In quotations throughout this article, Cowell's original, and rather idiosyncratic, spellings, punctuation, and abbreviations are preserved without repeated [sic] indications.) In the 1933 book American Composers on American Music, Cowell reported that Seeger had written “Studies in single, unaccompanied melody and in two-line dissonant counterpoint.”Footnote 6 The Charles Seeger collection at the Library of Congress, however, does not contain any manuscripts in Seeger's hand related to the early development of DC.Footnote 7 In Reminiscences of an American Musicologist (1972) Seeger referred to a syllabus he had written for his course in DC, which was destroyed in a fire:

I had a syllabus for this course, but unfortunately, all copies were burned up in the big fire in Berkeley, which burned up all my records of the Berkeley period, for I had left them in a small house down on Euclid Avenue and the flames burned everything within blocks of it. Later on, in his studies abroad, Henry Cowell swears that he saw a copy on the desks of both Schoenberg and Hindemith. I know I sent copies to them, but that they were on the piano or desk of Schoenberg of Hindemith we have to leave to Henry Cowell.Footnote 8

David Nicholls has speculated that Seeger's manuscripts related to the early development of DC may have perished in the Berkeley fire of 1926, although it is not clear why Seeger would have left any important belongings in California.Footnote 9 He was essentially forced out of his job at Berkeley because of his pacifist political beliefs, and he moved back east to Patterson, New York, in October 1918.Footnote 10 From the evidence that remains, it appears that Seeger composed one polyphonic work that used the technique, The Letter (1931), and one monophonic piece, Psalm 137 (1923), in which he explored the idea of writing a “dissonated” melody.Footnote 11

The only other surviving source that discusses the early development of the compositional method is Cowell's New Musical Resources, which he began in 1916, completed around 1919 (two years after his work with Seeger had ended), and published in 1930.Footnote 12 It offers a prose description of the method on pages 35–42 and one musical example of DC on page 119 in the section devoted to tone clusters.Footnote 13 The first typescript draft for New Musical Resources, housed in the Cowell Papers, includes an additional musical exercise on page 13(b) titled “Ex. 4. Stretto in dissonant counterpoint,” which was not included in the published version of the book.Footnote 14

As Judith Tick clarified in her biography of Ruth Crawford, Charles Seeger left Berkeley in 1918 and abandoned his work with DC.Footnote 15 Henry Cowell, however, continued to work on the method during the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, and he even disseminated it to other composers. Cowell continued teaching DC throughout the remainder of his career. In addition to private composition lessons he included the technique in his 1934 “Appreciation of Modern Music” course at Stanford University and in two courses offered at the New School for Social Research: “Advanced Music Theory” (1949–52) and “Materials of Modern Music” (1952–55).Footnote 16 Cowell's institutionalization of DC reflects a much wider dissemination than previously assumed.

It was not until 1929 that Seeger revisited the technique with Ruth Crawford at the insistence of Cowell, who had taught it to Crawford during the mid-1920s.Footnote 17 Crawford also probably shared with Seeger what she had learned about DC from Cowell. The collaborative efforts of Seeger and Crawford resulted in two documents, although only Seeger's name appears on them: a brief article published in 1930 in Modern Music titled “On Dissonant Counterpoint” and the larger “Manual of Dissonant Counterpoint,” the second part of the book Tradition and Experiment in (the New) Music, which was not published until 1994 by Seeger's biographer Ann Pescatello.Footnote 18 These sources describe the technique after this later stage of development involving Seeger and Crawford. Among their innovations was the application of the idea of “dissonance” to musical elements other than pitch. Crawford and Seeger also devised procedures to compose “neumes” (short melodic fragments), phrases, and melodies using dissonant leaps and complex, irregular rhythms, and addressed guidelines for combining properly “dissonated” melodies into two- and three-voice DC.Footnote 19

In addition to participating in the development of the technique, Cowell and Crawford shared it with their colleagues in the ultra-modern network, many of whom used the method in their compositions and advocated on its behalf.Footnote 20 Notable among the composers who made use of DC are José Ardévol, John J. Becker, Johanna Beyer, Vivian Fine, Lou Harrison, Wallingford Riegger, Carl Ruggles, Gerald Strang, and James Tenney, to name but a few (see Appendix A). In a letter to her student Vivian Fine, Crawford asked, “Would you be intrigued by the idea of writing counterpoint, not in an idiom which you will never use, but in an idiom which seems to be your spontaneous mode of expression?”Footnote 21 Crawford's comment suggests that she herself felt free to employ DC in a way that was distinctly her own. Indeed, the adaptability of the technique to an individual composer's aesthetic is likely responsible for its wide reception. As various composers employed the method idiosyncratically, they also participated in its development, and their works provided a continuing life for DC. Due to the efforts of Cowell, Crawford, and other composers associated with the ultra-modern network, the technique became a vital thread in American musical culture from the 1910s to the early 2000s.

Cowell's Studies at Berkeley

It is difficult to pin down a precise timeline of Cowell's activities at Berkeley; however, Seeger's recollections provide insight into Cowell's studies and the nature of their professional interaction while they worked on the early development of DC. Seeger and Cowell agreed on a course of study that involved the “concurrent but entirely separate pursuit of free composition and academic disciplines.”Footnote 22 To this end, Seeger reported, “I arranged special status at the University of California where [Cowell] took courses in harmony and counterpoint under E. G. Stricklen, then on my staff. One afternoon a week was given to exploring the resources of twentieth-century music with me.”Footnote 23 Regarding Cowell's counterpoint lessons, Seeger added, “An Englishman in town [organist and composer Wallace Sabin] . . . took Henry over for just the strict counterpoint. I could teach the freer counterpoint and so could my assistant Stricklen, which was then in vogue in Harvard where I had studied and as far as I could find out pretty much throughout the country. They didn't begin to study strict counterpoint until some years afterwards in American universities.”Footnote 24

Seeger recalled that he offered a course in DC in 1916, in which Cowell was an active participant. “I was in [1916] giving my first rather tentative course in dissonant counterpoint to a senior class. It apparently impelled Glen Haydon into a life of almost ultra-conservatism. But Cowell outstripped us all in quantity of work and went off on a tangent to develop a system of his own which differed from mine.”Footnote 25

Seeger provided a detailed description of his experience teaching Cowell in a 1940 article for the Magazine of Art, from which we learn something of their student-teacher relationship. Seeger observed that Cowell “became, by sixteen the most self-sure autodidact I ever met.”Footnote 26 Further down the page Seeger noted,

The confirmed autodidact won't take or give anything on authority. Nor anything which seems suggested from without. Collaboration is fine. So you speculate, plan, and in general improvise upon the potentialities in (and out of) sight. An idea may appear from anywhere. After it has been knocked around for a while it either disappears for good or turns into something interesting, and lord knows whose it was in the first place. . . . Before long, no one can tell which is learning the most, the autodidact or the autodidactor.Footnote 27

According to Seeger, their work was a collaborative act in which both teacher and student learned from one another. In addition, notes Ann Pescatello, “Cowell's work with Seeger from 1914 to 1916 revolved around Seeger's making his first tentative approaches toward a systematic use of dissonance.”Footnote 28 Because Seeger was just beginning to work out a system of DC, his collegial relationship with Cowell likely led to their working together on the earliest thinking about the method.

Seeger's recollections in the 1970s continue to confirm that both he and Cowell were involved in the development of DC, and that Seeger's own work with the idea was in its very early stages. In a 1974 interview with Rita H. Mead, Seeger said,

You see, I'd had a class in dissonant counterpoint at the University of California in which you had to prepare consonance and resolve it. The first species didn't allow any consonance; the augmented fourths and diminished fifths took the place of the unison and the octave together. The octave was forbidden. And Henry had taken that and then worked out his own system, because my system was not really well-developed then.Footnote 29

Seeger made a similar observation in an interview with Andrea Olmstead in July 1977:

I had just evolved a theory of dissonant counterpoint and Henry just jumped on that. He went ahead and developed it faster than I did. I didn't get it fully developed until 1930 when I taught my wife Ruth. That combined with the musical logic made a composition which is since called serial composition. And I worked on that in a desultory way—I had so many other things to do—up to about 1918. Then I gave up composition. I didn't think about it anymore until '30 again when I gave it a rethinking and Ruth and I wrote a book which has never been published, but I still have it.Footnote 30

Despite the differences in their educational background and the fact that Cowell came to Berkeley to study with Seeger, Seeger's own recollections thus credit Cowell as an active participant in the early development of DC. Archival sources corroborate Cowell's contribution.

Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint Notebook

A published score and a separate archival document anecdotally refer to Cowell's writing musical exercises in personal notebooks during his collaboration with Seeger. Possibly written by Sidney Cowell, the introductory note to the 1965 publication of Henry Cowell's String Quartet No. 1, which the composer completed in 1916, acknowledges his work with Seeger on DC and states, “Cowell filled several notebooks with exercises he devised for himself and then attacked the present piece.”Footnote 31 A document housed in the Seeger archive at the Library of Congress, labeled “A note for Charles Seeger's biographer, set down by Sidney Cowell in 1966,” also refers to Cowell's work at Berkeley with Seeger. Sidney Robertson Cowell recalled,

[Henry Cowell] had used a kind of chordal dissonant counterpoint in some of his compositions and had always been free of any preconceived notions about resolving dissonances. The suggestion of a theoretical “system” of dissonant counterpoint set him off into several notebooks of exercises, in the earliest of which he arrived at his “rules” by the literal opposite of those for sixteenth century counterpoint [i.e., the counterpoint chiefly uses dissonant intervals, and consonant intervals should be preceded and followed by dissonant ones].Footnote 32

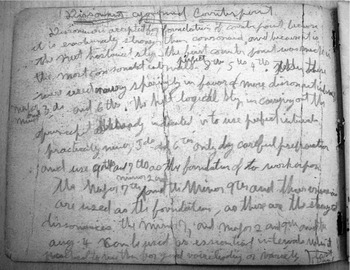

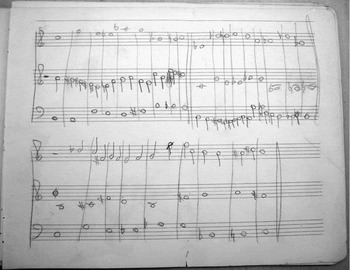

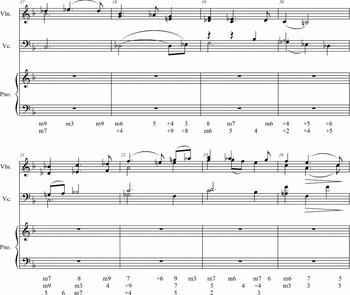

Ten of the eleven extant counterpoint notebooks in Box 31 of the Cowell archive are filled with exercises that employ traditional contrapuntal practices. The eleventh notebook, identified on the front cover only by the number 15, contains instructions for using DC, written primarily on the inside of the front and back covers, as well as forty-three exercises exploring the method written on eight of the seventeen available pages; the other pages are blank (see complete transcription in Appendix B). The exercises use three different cantus firmi and employ the five species associated with Fuxian counterpoint pedagogy. (Figure 1 displays a photograph of Cowell's handwritten instructions on the inside cover.) The notebook begins with twenty-six two-voice exercises, which progress in order from the first through the fifth species. (The photograph of Cowell's notebook in Figure 2 features two-voice exercises on page 1 recto.) These are followed by seventeen three-voice exercises, which also follow the same systematic progression through the five species. (Figure 3 shows three-voice exercises on page 5 recto of the notebook.)

Figure 1. Henry Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint Notebook: inside of the front cover. The Henry Cowell Papers, box 31, folder 5, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Reproduced by permission of The David & Sylvia Teitelbaum Fund, Inc.

Figure 2. Henry Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint Notebook: page 1 recto. The Henry Cowell Papers, box 31, folder 5, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Reproduced by permission of The David & Sylvia Teitelbaum Fund, Inc.

Figure 3. Henry Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint Notebook: page 5 recto. The Henry Cowell Papers, box 31, folder 5, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Reproduced by permission of The David & Sylvia Teitelbaum Fund, Inc.

Cowell's handwritten discussion of DC begins with a rationale for the technique, followed by guidelines addressing the use of intervals, motion from note to note, textures of three or more voices, and specific rules for the species exercises. Cowell justifies the compositional practice by asserting,

Dissonance is accepted for [the] foundation of counterpoint because it is emotionally stronger than consonance and because it is the next historical step. The first counterpoint was made in the most consonant intervals: perfect 8ths, 5ths, 4ths. Next these were used very sparingly in favor of more dissonant intervals: major and minor 3ds and 6ths.Footnote 33

Cowell continues by enumerating the appropriate use of intervals for the new method:

The next logical step in carrying out the principal [sic] already indicated is to use perfect intervals practically never, 3ds and 6ths only by careful preparation and use 9ths and 7ths as the foundation to work upon. . . . The major 7th[,] minor 2nd[,] and the minor 9th and their inversions are used as the foundation, as these are the strongest dissonances. The minor 7, and major 2 and 9th[,] and the aug. 4 can be used as essential intervals when it [is] practical to use them for good voice leading or variety. . . .Footnote 34 Aug. and dim. intervals enharmonically the same as consonances had better not be used as essential dissonances because although in reality dissonant, they are apt to be mistaken remind[ing] th[e] listener of their enharmonic equivalent, unless used in just the right surroundings to bring out their true character.Footnote 35

Cowell outlines different procedures concerning the proper motion from note to note, including voice leading, contrary motion, the consecutive use of intervals, and voice crossing:

The voice leading of strict counterpoint [i.e., primarily conjunct voice leading], which is based on vocal difficultys, is preferable only with the full addition of chrom. semitones and an occasional use of augmented intervals and minor 7ths if in good melodic curves.Footnote 36

Because it is a strong diss and the extreme compass of the chrom scale before a repition is started, the maj 7th is a very good interval to start on. The minor 9th is also a possibility. . . . Contrary motion is desirable. . . . Only 3 consecutives are allowed of any kind. Only 7ths and 9ths may be written consecutively, occasionly aug. 4. Consec. 2nds are muddy and blur the clarity of the parts. . . .Footnote 37 For the sake of clarity crossed and overlapped parts are only used in emergencies.Footnote 38

Cowell provides additional guidelines for exercises with more than two voices as follows:

In three or more parts the aim is to have all parts in dissonance to each other. Between an inner and top part may be consonance if there is somewhere a diss. preferably from the bass. If weak dissonance only is used all parts should be dissonant to each other. Only intervals and melody are considered to the exclusion of Durch Harmonie principals.Footnote 39

In addition to containing valuable information about DC, Cowell's notebook provides crucial evidence that nuances our understanding of his work habits. Some of his writings, especially his letters, show Cowell to be somewhat scattered, jumping from one idea to the next and juggling many ideas at once without fully exploring them. His DC notebook, however, presents Cowell as a systematic and tenacious worker, who revered tradition as well as experimental techniques and placed a strong emphasis on the practical application of new ideas in addition to their theoretical development.Footnote 40 These traits made Cowell the ideal disseminator of the compositional practice from the late 1910s through the mid-1960s.

The layout of the exercises in his notebook reveals a disciplined approach to an investigation of the new idea. Table 1 details the arrangement of the exercises in the notebook. These exercises are not numbered in the original; they are presented in full in Appendix B, to which the reader should refer during the ensuing discussion. On page 1 recto Cowell created five two-voice first-species exercises, three with melodies written in dissonant intervals above the cantus firmus (labeled here as cantus firmus 1), and two with melodies below the cantus firmus. On the reverse side of the first page he composed note-against-note DC above and below a new cantus firmus (labeled here as cantus firmus 2). On page 2 recto Cowell wrote four second-species exercises. For the third-species exercises on page 2 verso Cowell established a pattern that he continued to use with the fourth- and fifth-species exercises: They all employ cantus firmi 1 and 2 in both the top and bottom voices. Having completed two-voice exercises in all five species, on page 4 recto Cowell examined the application of DC in three-voice writing. These exercises include four respectively in the first and second species and three in the third, fourth, and fifth species. For every species Cowell placed a cantus firmus in each of the available voices and wrote a melody using the given species either above or below the cantus firmus. The remaining voice was always written in first-species DC against the cantus firmus.

Table 1. Layout of Henry Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint Notebook and Arrangement of the Exercises

An incomplete exercise on page 7 recto sheds light on the procedure that Cowell likely used for writing the three-voice exercises (see Exercise 39 in Appendix B). The top voice features a cantus firmus, the middle voice contains a fifth-species melody, and the bottom voice is empty. It appears that after Cowell copied the cantus firmus into one of the voices, he wrote a melody using the specific species either above or below it and then composed the remaining voice in first-species counterpoint.

In addition to the disciplined practices evident in the notebook, other sources point to the young Cowell as a systematic thinker. For example, Lewis Terman, a psychology professor at Stanford who developed the Stanford-Binet IQ test, had conducted an analysis of Cowell's intellect at age fourteen and included the case study in his 1919 book The Intelligence of Schoolchildren.Footnote 41 He noted the following:

As the result of many hours of conversation with the boy, over a period of many months, we are convinced that his ability in science was almost as great as in music. Before the age of 12 he had read university textbooks in botany. His knowledge of California wild flowers at this age was remarkable. He had studied seriously the principles of plant breeding, and for a time, when it seemed impossible to realize his musical ambitions, he considered botanical science for his life-work. . . . If he attains fame as a musician, his biographer is almost certain to describe his musical genius as natural and inevitable, and to ignore the scientist that he might have been.Footnote 42

In New Musical Resources Cowell presented a new notation system using different shapes for complex subdivided rhythms and discussed “scales of rhythms,” a rhythmic system based on the ratios of the overtone series.Footnote 43 During his incarceration in San Quentin (1936–40), Cowell wrote The Nature of Melody, which includes (in addition to many other subjects) a thorough investigation of sliding tones and a system for classifying them.Footnote 44 Cowell's private composition lessons for Lou Harrison revealed systematic pedagogical approaches to counterpoint and the manipulation of small motivic cells.Footnote 45 Additionally, in his 1951 “Advanced Music Theory” course at the New School for Social Research Cowell presented a systematic method for writing polychordal harmonies based on the use of both traditional counterpoint and DC exercises as a framework.Footnote 46

Cowell's tenacious exploration of DC resulted in multiple exercises for each species, totaling over forty. Another example of his focus and determination is found in the careful treatment of melody in nine two-voice first-species exercises. Eight are written on both sides of page 1, and the ninth is found on page 17 verso. Perhaps Cowell wrote so many more two-voice first-species exercises than any other type because they represented the beginning of his endeavor and the foundation for understanding how to use the technique. Based on Cowell's identification and discussion of intervals in the description of DC in his notebook, in my analytical discussions I have disregarded octave expansions beyond ninths.Footnote 47

In exercises 1–3 Cowell composes three distinct melodies above the same cantus firmus, presumably to examine the various shapes of melodies that could be written while still maintaining dissonant intervals. Upon closer examination, the upper voice in the second exercise appears to be a variant of the melody in the first one; only three of the pitch classes in exercise 2 differ from those in exercise 1. In m. 2 of exercise 2 Cowell replaces the F-sharp from exercise 1 with C-sharp, which results in an augmented fourth between the two voices instead of a major seventh. In m. 5 Cowell writes a G instead of a D, which replaces the augmented fourth with a major seventh. Finally, in m. 6 Cowell changes the F-sharp, a major seventh above the bass note, to a G-sharp, an augmented octave above it. These changes result in a more conjunct melody in the upper voice of exercise 2.Footnote 48 In addition, the alterations to the melody provide variety from the consecutive sevenths in mm. 1–3 and 6–7 in exercise 1. The upper voice in exercise 3 may also be a variant of the upper voice in exercise 1; Cowell maintains the same pitch classes in mm. 2, 4–6, and 9. The upper voice in exercise 3 differs from the upper voices in the previous two exercises because the melody does not begin and end on the same pitch.

Cowell's regard for tradition can be seen in the use of the counterpoint species and cadential formulas, the structure of cantus firmus 1, and the balanced melodic motion in the melodies he added to the cantus firmi. The picture of Cowell that emerges from his notebook differs from characterizations that focus on him as a bold iconoclast with little use for musical tradition. Cowell uses the five species associated with Fuxian contrapuntal pedagogy to guide his practical application of the principles laid out for DC. Just as in Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum, Cowell begins by writing two-voice exercises and then moves on to those in three voices. Furthermore, the ten other counterpoint notebooks in box 31 of the Cowell archive are filled with exercises that demonstrate his dedication to mastering conventional compositional techniques.

In the course of writing the two-voice first-species exercises, Cowell explores the use of cadential formulas, a technique that is an essential part of traditional contrapuntal practice. These exercises feature two different cadential formulas, each of which has a variant. The first, used in mm. 8–9 of exercises 1 and 2, contracts from a minor ninth to a major seventh. A variant of this cadence is found in mm. 8–9 of exercise 3, in which C-sharp is substituted for C; the cadence begins on a major ninth and contracts to a major seventh. The second formula, found in mm. 8–9 of exercise 4, involves the expansion of a major seventh to a minor ninth. Cowell employs a variant of cadence 2 in mm. 8–9 of exercise 5. C-sharp is substituted for C, which results in a minor seventh expanding to a minor ninth. Whereas Cowell uses these cadences exclusively in the two-voice first-species exercises, the rest of the notebook shows more varied cadential structures.

The melodic structure of cantus firmus 1, featured in the bottom voice of exercise 1, provides another example of Cowell's acknowledgment of tradition. The melody begins with a stock figure from traditional counterpoint, the leap of a perfect fifth, and then outlines prominent tones suggestive of both C major and C minor, including E, E-flat, A-flat, B-flat, and B. The leap to A-flat, followed by the stepwise descent to G, emphasizing scale degree 5, is a gesture reminiscent of eighteenth-century melodic structures, especially in contrapuntal subjects (Examples 1a and 1b show two well-known instances). Melodic movement atypical of traditional contrapuntal practice includes the descending leap of a major sixth from G to B-flat (especially because it follows the descending motion from A-flat to G) and the ascending stepwise chromatic motion from B-flat to B to C.

Example 1a. J. S. Bach, Well Tempered Clavier, Book 1, Fugue in B Minor, m. 1.

Example 1b. G. F. Handel, The Messiah, “And with His Stripes We Are Healed,” mm. 1–5.

The aspect of balance that characterizes traditional contrapuntal practice—for example, following an ascending leap by a leap or substantial stepwise motion in the opposite direction—is manifest in Cowell's two-voice first-species exercises as well. One of his marginal annotations shows his awareness of this practice: “A return is made to the same point for the sake of balance,” he notes.Footnote 49

The contents of Cowell's notebook underscore the importance that he placed on developing new methods “in practice” as opposed to solely “in theory.” Rather than engaging exclusively in theoretical musings about DC, Cowell created musical exercises to examine the ways in which these principles actually work themselves out during the compositional process. The practical application, in turn, allowed Cowell to further refine the method. For example, Cowell wrote several newly developed rules in the margins of the two-voice fourth-species exercises on page 3 recto that appear to be the result of his experience gleaned from writing fourth-species exercises in DC. “Owing to [difficulty?] of getting this species the opening often must begin on a weak dissonance. An enharmonic dissonance may be skipped from in cases of emergency. Notes may be enharmonically changed over the bar if convenient so as to keep concord moving. In preparing the tied over notes, try to get the strongest common dissonance.”Footnote 50

The forty-three counterpoint exercises in Cowell's notebook provide examples of his practical application of the principles outlined in the prose description of “dissonant governed counterpoint.” They also provide additional insights into DC beyond that which is indicated by the written guidelines on the inside of the front and back covers of the notebook.

Cowell's Use of the Guidelines in Two-Voice Exercises

An examination of Cowell's two-voice exercises, along with his various marginalia, demonstrate his application of DC to the five species and the various issues that arise in the process. The treatment of consonant intervals often emerges as a concern.Footnote 51 For example, on page 1 recto, Cowell notes, “no consonance possible in first species, except rarely an enharmonic cons[onance].”Footnote 52 This guideline is manifest in Exercise 7; all intervals between the cantus firmus and the added upper voice are dissonant. This exercise aptly demonstrates as well Cowell's principles of dissonance and consonance treatment, his recommended rules for consecutive intervals, and his voice leading guidelines. The example begins and ends on a major seventh; predominantly contrary motion is mixed with parallel motion; the exercise features only two consecutive minor ninths (mm. 10–11); there is no voice crossing; and the melody moves primarily stepwise, with the use of an occasional augmented interval or wide leap for melodic variety.Footnote 53

Cowell's written instructions among the third-species exercises on page 2 verso provide insight about the technique as applied to the second through fifth species. Below exercise 16 he writes, “Skip to consonance justifiable as changing notes.”Footnote 54 This statement refers to m. 7 of exercise 16, in which the melody skips from A-sharp, an augmented octave above the bass, to F, a minor sixth above the bass. Cowell's rationalization of the melodic skip to an interval that is consonant above the bass note suggests that the “careful preparation of consonance” mentioned in his guidelines should otherwise involve stepwise motion, as is usual in traditional contrapuntal methods.

In other two-voice exercises contained in the notebook, consonant intervals are approached and left by stepwise motion; melodic leaps usually occur when leading toward and away from dissonant intervals. In exercise 9, for instance, the major third in m. 3 is approached and left by stepwise melodic motion in the upper voice. All the leaps in the upper voice occur as the melody moves from one dissonant interval to another. For example, in m. 4 the melody leaps from F, a major ninth above the bass note E-flat, to D, a major seventh above the bass note, to A, an augmented octave above the new bass note A-flat.

The same observations hold true in exercise 19. Stepwise melodic motion is used to accompany the consonant intervals in mm. 7–8, and melodic leaps occur in conjunction with dissonant intervals. Cowell's additional guidelines in the margins on page 3 recto demonstrate his concern for the careful treatment of consonant and dissonant intervals in the fourth species exercises. He states, “Only a tied over [i.e., suspended] dissonance may skip, but a consonance may be tied over [i.e., suspended over the bar line] enharmonically to make a dissonance in cases of need. The consonance should resolve by falling.”Footnote 55 Furthermore, in order to understand the C-sharp tied to D-flat in mm. 10–11, one must defer to another recommendation made by the composer, which is likely informed by his experience writing suspensions according to the guidelines of DC. Cowell comments, “Notes may be enharmonically changed over the bar if convenient so as to keep concord moving.”Footnote 56

Exercise 22 demonstrates Cowell's careful handling of consonance. Here the consonant intervals between the two voices in mm. 2 and 6 are approached by step (or suspension) and resolved by stepwise melodic motion. The melody in the upper voice comprises primarily conjunct motion with the exception of two leaps, both of which coincide with dissonant intervals. Between mm. 4 and 5 the melody skips from D, a major seventh above the bass note E-flat, down to G, a major seventh above the new bass note A-flat. In m. 7 the A in the upper voice, a suspended note that forms a major seventh against the B-flat in the lower voice, leaps to a C, a major ninth above the bass note.

Whereas the first-, second-, fourth-, and fifth-species exercises are more consistent in their adherence to the guidelines, the third-species exercises feature instances that both confirm and contradict the written guidelines for DC. In exercise 15 most occurrences of consonant intervals between the two voices are prepared and resolved by stepwise motion in the upper voice. An exception is found in m. 10, where the melody skips to a minor third below the cantus firmus and is then followed by a perfect fourth. (Although in traditional two-voice part writing a perfect fourth is treated as a dissonance, Cowell, in his guidelines, includes it among “the most consonant intervals.”)Footnote 57 This melodic gesture presents two problems: a melodic leap to a consonance, and the consecutive movement from one consonant interval to another (referred to hereafter as consecutive consonances) rather than the proper resolution to a dissonant interval. Because the idea of DC is based on the reversal of traditional counterpoint, it follows that the careful preparation and resolution of a consonant interval should involve both stepwise motion in the added melody and the occurrence of a dissonant interval before and after the consonant interval. However, Cowell never directly stipulated in the notebook that consonant intervals should always be preceded and followed by dissonant intervals, suggesting that he conceived of these ideas more as flexible guidelines than as fixed rules.

Although m. 10 of exercise 15 contains the only occurrence among the third-species exercises of a melodic leap to a consonant interval, it is worth noting that all the two-voice third-species exercises feature instances of consecutive consonances. For example, in m. 8 of exercise 16, the primarily stepwise melodic motion in the upper voice results in three adjacent consonant intervals: a major third, perfect fourth, and perfect fifth. Exercise 16 also features melodic movement inconsistent with Cowell's guidelines for the treatment of consonance, located between mm. 2 and 3 and in m. 7. He explains that the leap to a minor sixth in m. 7 is justified because of changing tones, but he does not address the gesture in the upper voice in m. 3. The minor third in m. 3 is approached by stepwise melodic motion but is not left by step; instead, the melody leaps down a major third. Also, the minor third is not preceded by a dissonant interval, but instead by a consonant interval in the previous measure. The occurrence of consonant intervals in strong metrical positions presents another possible deviation from a strict application of the guidelines among the two-voice third-species exercises. For example, exercise 16 features a major third on the third beat of m. 1, a minor third on the downbeat of m. 3, and a perfect fourth on the third beat of 8. Generally in traditional counterpoint dissonance is reserved for the metrically weak positions; therefore in DC we would expect consonant intervals to be found on the second and fourth beats in third-species counterpoint.

Cowell's Use of the Guidelines in Three-Voice Exercises

The three-voice exercises, which were also written in all five species, present further insight into Cowell's practical application of his written guidelines for DC. The composer uses more dissonant intervals than consonant intervals and perfect intervals “practically never”; however, some exercises test the guidelines, particularly with regard to voice leading and the careful treatment of consonant intervals, and reveal both strict and flexible approaches to the guidelines. It also appears that some of Cowell's additional written guidelines for three or more voices do not actually work in practice.

The additional melodies in the three-voice examples are primarily conjunct, as in the two-voice exercises. The third voice, which is always written in note-against-note counterpoint, features many leaps, rather than stepwise motion; the primarily disjunct melody likely results from choosing tones that are dissonant against at least one of the other parts, if not both. In exercise 36, a three-voice fourth-species exercise, the third melody, here in the top voice, is written in 1:1 counterpoint against the cantus firmus and comprises mostly disjunct motion. Likewise, the middle voice in exercise 31, a three-voice second-species exercise, features quite a few leaps in the melody.

Considering Cowell's guidelines for DC, exercise 31 exhibits both stringent adherence and flexible approaches to the suggested treatment of consonant intervals. Instances of Cowell's strict handling of consonances are found in mm. 3 and 7. The downbeat of measure 3 features a minor third between the top and bottom voices. The melody moves by step from F-sharp in the preceding measure to G, a minor third above the bass note, E, and then to F. Also the consonant interval between the two voices is preceded by a major seventh and followed by a minor ninth. In m. 7 the G in the middle voice is a major sixth above the B-flat in the bottom voice. The occurrence of a consonant interval between the two voices is preceded by a major seventh in m. 6 and followed by a minor seventh in m. 8; furthermore, the major sixth is accompanied by stepwise melodic motion in the middle voice.

Examples of Cowell's flexible approach to the guidelines for consonant intervals are found in mm. 2 and 6 of exercise 31. In m. 2 the C in the top voice is a perfect fourth above G in the bottom voice. The C is approached by step from D-flat, but then the melody leaps from C down to F-sharp, instead of leaving the consonant interval by conjunct motion. On the second beat of m. 6, the C in the top voice is a perfect fourth above G in the bottom voice. The C, however, is approached by a leap from F above it, rather than by stepwise motion.

Exercise 33, a three-voice third-species exercise, includes a number of instances that contradict the careful handling of consonance prescribed by Cowell's guidelines. First, in mm. 3, 5, 7, and 8 consonant intervals fall on the strong beats of the measures. Also, the primarily stepwise motion in the middle voice results in several instances where a consonant interval is followed by another consonant interval instead of a dissonant interval. For example, in m. 4 the melody moves from A, a major third above F in the bass, to B, a perfect fourth above the new bass note, F-sharp. Also, in m. 5 the melodic progression from D to D-sharp in the middle voice results in a minor sixth followed by a major sixth against the bass note. In m. 7 not only are there two consecutive consonant intervals, but the melody in the middle voice also leaps from one consonance to the other, in this case from C, a perfect fifth above the bass, to A, a major third above the bass note. Finally, in mm. 8–9 four consecutive consonances are located between the middle and bass voice: a minor sixth, a perfect fifth, and two perfect fourths, the last of which is part of the final cadence in m. 9.

As part of his additional guidelines for three or more voices Cowell notes, “The aim is to have all parts in dissonance to each other.”Footnote 58 Although some exercises feature individual sonorities in which all parts are dissonant, no three-voice exercise in the notebook actually achieves the goal of exclusively dissonant intervals throughout. (In fact, this goal would be incredibly difficult to sustain in a three-part texture, especially if any measure of stepwise motion is also desired. The three parts can be dissonant to each other only when all three simultaneous pitch classes are chromatically adjacent.) For example, in exercise 25, a three-voice first-species exercise, seven measures (mm. 4, 6, and 8–12) contain sonorities with dissonant relationships between all three parts. The other five measures (1–3, 5, and 7) include a consonance somewhere in the vertical sonority.

Cowell's goal of complete dissonance undermines his initial allowance of consonant intervals, provided they are handled carefully. In his prose description of the technique he stated, “The next logical step in carrying out the principal already indicated is to use perfect intervals practically never, 3ds and 6ths only by careful preparation and use 9ths and 7ths as the foundation to work upon.”Footnote 59 In the two-voice exercises carefully handled consonant intervals are allowed in the second through fifth species. It may have been truer to actual practice had Cowell stipulated that for three or more voices there should always be a dissonant interval between at least two of the voices in any given vertical sonority.

Perhaps in an effort to address the issue that consonant intervals are allowed in DC, Cowell writes, “Between an inner and top part may be consonance if there is somewhere a diss. preferably from the bass.”Footnote 60 This rule suggests that consonance is not allowed between the bass part and any other voice, but the rule is widely contradicted by the examples. In fact, every three-voice exercise in the notebook contains at least one instance of a melody with a tone that is consonant against the bass voice. Exercise 25 begins with a major sixth between the top and bottom voices. The final sonority in exercise 33 includes a perfect fourth between the bottom and middle voices. In some cases, both the middle and upper voices simultaneously feature tones that are consonant with the bass voice, although these voices are dissonant with each other: Examples include exercise 33 on beat 4 of m. 4, where A and A-flat in the upper voices against F in the bottom voice, and the final measure of exercise 29, in which C and C-sharp in the upper voices sound against A in the bottom voice.

Beyond the Notebook: Cowell's Works

In addition to creating didactic exercises and participating in the early development of DC, Cowell used the technique in compositions that span nearly fifty years of his career and encompass a variety of genres.Footnote 61 (See Cowell's works listed in Appendix A.) A survey of five works dating from 1916 to 1965 demonstrates that in actual compositions Cowell did not feel bound to the principles of DC as orthodox rules; in fact, the technique could be adapted in many ways within his compositional aesthetic. Cowell's flexible application of the compositional method should come as no surprise considering two statements he made in New Musical Resources. In the preface Cowell asserted, “The aim of any technique is to perfect the means of expression. If a technique serves to dry up and inhibit the expression, it is useless as a technique.”Footnote 62 Recognizing the need for flexibility in the application of any rules he added, “The detailed manner in which each material may be handled is hardly a matter to be decided beforehand and forced upon composers; each one has the right and desire to manage his own materials in such a fashion that they become the best vehicle for his own musical expression.”Footnote 63

Cowell's flexible use of DC, however, should not be mistaken for a consistent chronological trend of “tempering” the compositional technique as posited by Bruce Saylor in his article “The Tempering of Henry Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint.”Footnote 64 The five examples below demonstrate that throughout his career, in addition to his varying approaches to the technique, Cowell continued to use practices that were influenced by his early work on DC, notably (1) mostly conjunct melodies, (2) both dissonant and consonant intervals between the voices, though primarily dissonances, and (3) varying degrees of strict and flexible handling of consonant intervals, the strictest of which would entail having every consonant interval preceded and followed by a dissonant one and approached and left by stepwise melodic motion. Thus, each piece represents an example on a continuum that ranges from Cowell's most exact to most flexible application of the guidelines associated with DC.

Cowell wrote the String Quartet No. 1, L. 197, in 1916 shortly after beginning his work on DC. The introductory note to the published score discusses the relationship between the musical style, DC, and Cowell's original name for the work: “Henry Cowell's First String Quartet was originally called the Pedantic because in 1916 dissonance and even counterpoint in contemporary composition were regarded with severity as ‘uninspired’ and were relegated strictly to the world of academic theory.”Footnote 65 In addition to recounting Cowell's work with Seeger on DC, the note also provides a description of each movement in the piece:Footnote 66

The work is in two movements of which the first is the longest, and written in the first systematically dissonant style Cowell evolved, a style that was in rather literal contradiction to convention: consonance was reserved for passing tones and resolved into dissonance. The second movement is homophonic and comparatively short. Chords are usually in five parts; their basis is consonant but each includes one or two dissonant tones that are not resolved.Footnote 67

Finally, the introduction provides a rough chronological distinction between the String Quartet No. 1 and the other two quartets that he was writing during (and shortly after) his time at Berkeley, the Quartet Romantic and the Quartet Euphometric. It states, “after finishing this piece Cowell went to work, in the same year, on the two so-called ‘rhythm-harmony’ quartets, the Romantic and the Euphometric.”Footnote 68

The first movement of the String Quartet No. 1 can be divided into two distinct sections, and in each Cowell investigates the application of contrapuntal techniques within the framework of DC. The A section (mm. 1–43) opens with free counterpoint in all four voices in mm. 1–2. In m. 3 a motive arises in the cello part from the sustained note E in m. 2 (Example 2a). It is accompanied by whole notes in the other three parts; the lack of rhythmic activity in the other parts calls attention to the cello motive. The melodic motion is primarily disjunct; it begins on an E, descends a minor second and then an octave, ascends by a leap of a major seventh, and skips down a minor third. This motive is repeated in m. 5 of the cello part on G and then imitated by the first violin in m. 6 on B, and by the second violin beginning on the last beat of m. 6 on B-flat (Example 2b). (The numerals below the staff indicate the intervals above the lowest voice.) As the motive is imitated in the different voices, Cowell uses free counterpoint in the remaining three voices to weave vertical dissonant intervals around the melody.

Example 2a. Henry Cowell, String Quartet No. 1 (1916), mvt. 1, m. 3, motive in the cello part. Copyright © 1964 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Example 2b. Henry Cowell, String Quartet No. 1 (1916), mvt. 1, mm. 5–7. Copyright © 1964 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

The B section of the first movement (mm. 44–79) looks as if it could have been a separate movement; the beginning is preceded by three measures of rest in all the parts, and it is labeled with a different tempo marking (quarter note = 112) and the instruction Allegro non troppo. In this section imitation pervades all four voices (Example 3). The opening motive in the viola primarily comprises disjunct melodic motion in consonant intervals: a perfect fourth, followed by a minor third, a perfect fifth, and a minor third, after which the motive moves by a step, a major third, and two more steps. Despite the consonant intervals involved in the melodic motion of the motive, Cowell maintains a dissonant relationship between the voices by stating the motive in the viola on F-sharp, then on F in the cello, C-sharp in the second violin, and finally on B-flat in the first violin. The B section strongly resembles a canon, although it is not a pure example of the form; as each voice progresses it departs at several points from either the original durations or intervallic motion from note to note.

Example 3. Henry Cowell, String Quartet No. 1 (1916), mvt. 1, mm. 44–49. Copyright © 1964 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

The second movement of the String Quartet No. 1 features sustained dissonant sonorities moving primarily homorhythmically and melodic motion that is mostly conjunct. For these reasons, the second movement has the character of a five-voice study in first-species DC, despite the description in the introduction cited above, which refers to these sonorities as consonant chords with unresolved dissonances. Example 4 shows the vertical sonorities from mm. 1–4 condensed onto a grand staff with figures below the staff that indicate the intervals above the bass. Cowell chose the traditional genre to explore an in-depth application of DC over a sustained period of time, using various polyphonic textures and methods, including imitative and familiar-style polyphony, and the canon.Footnote 69

Example 4. Henry Cowell, String Quartet No. 1 (1916), mvt. 2, sonorities from mm. 1–4. Copyright © 1964 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Cowell composed the string trio Seven Paragraphs, L. 408, in 1925; all seven brief movements are written in a polyphonic texture. This piece was featured on Cowell's 1926 concert in New York as “Chapter in Seven Paragraphs for Violin, Viola, and ‘Cello.”Footnote 70 In the program notes the composer identifies the work as an example of “sonant counterpoint,” about which Cowell explained, “Following the development of dissonant counterpoint, I began utilizing it with consonant counterpoint, welding them together in a new polyphony in which the consideration was no longer dissonance or consonance, either one being used according to the demand of the melodic outline.”Footnote 71 Although Cowell did not enumerate specific rules for “sonant counterpoint,” his description demonstrates that he had given further thought to a freer application of DC in order to allow for more artistic flexibility. Rather than strictly adhering to the rules of DC in any given composition, he allowed himself to write in a new polyphonic style (“sonant counterpoint”) that was not encumbered by considerations regarding the intervals produced by the various melodies but allowed for more focus on the structure of the melodies themselves. All seven movements present different approaches to writing three-voice counterpoint using this new polyphonic approach. The opening of the fifth movement demonstrates the influence of Cowell's ideas associated with sonant counterpoint (see Example 5). Most notable is the high ratio of consonant to dissonant intervals; some vertical sonorities in Seven Paragraphs comprise entirely consonant intervals, including triads, for example, the B-flat minor chord on the downbeat of m. 2.

Example 5. Henry Cowell, Seven Paragraphs (1925), mvt. 5, mm. 1–8. Copyright © 1966 by C. F. Peters Corporation. All rights reserved. Used by kind permission.

Despite the overwhelming presence of consonant intervals in this piece, each vertical sonority often includes at least one dissonant interval. Because dissonant and consonant intervals are freely used according to the dictates of the melodic lines, it follows that strict specifications cannot be prescribed for the preparation or resolution of consonant or dissonant intervals. Consonant intervals are no longer required to be preceded and followed by dissonant intervals using stepwise motion in both voices. Thus, it would not be uncommon to find a lengthy passage of consecutive consonances such as that in mm. 5–7, where the viola and cello parts feature eight consecutive thirds. In this passage numerous dissonant relationships exist between the three voices, and there are only three purely consonant vertical sonorities: on the second beats of mm. 5 and 6 and the downbeat of m. 7.

Cowell's relaxed application of the guidelines for DC (via “sonant counterpoint”) found in Seven Paragraphs demonstrates another possible way that he used the technique, but this usage should not be confused with a consistent tempering of DC; a case in point is the later work Suite for Woodwind Quintet, L. 491b (1934), which features more overall dissonance than Seven Paragraphs. The four movements of this work are arrangements of movements 2, 4, 5, and 6 of Six Casual Developments for Clarinet and Piano, written a year earlier.Footnote 72 In the introductory note to the published score, Richard Franko Goldman referred to the third movement as a chorale characterized by “extended lines in slow, irregular meter, with a touching and sustained piquancy of harmony.”Footnote 73 The discordant harmonic effect described by Goldman as “piquancy of harmony” results from the influence of DC on Cowell's compositional style. The irregular meter adds a sense of metrical dissonance to reinforce the counterpoint (Example 6).Footnote 74 Each measure in the third movement constitutes a phrase of the chorale, which is supported by the phrasing marks and the longer duration demarcating the beginning and ending of each measure. Within a given phrase, the melodic lines in all five parts are primarily conjunct with some disjunct motion for balance. The counterpoint results in primarily dissonant intervals with a few consonances as well. Examining the vertical sonorities, in most cases the tones in the upper voices that are consonant against the lowest voice share a dissonant relationship among themselves. (The clarinet and horn parts in Example 6 have been transposed to reflect the sounding pitches.) For example, on beat 2 of m. 1 the tones above G in the bassoon include E-flat, A, E, and C-sharp. The E-flat in the flute and E in the clarinet are a minor sixth and major sixth, respectively, above G, but they are a diminished octave apart from each other. Also, the E-flat in the flute is a diminished fifth above A in the oboe.

Example 6. Henry Cowell, Suite for Woodwind Quintet (1933–34), mvt. 3, mm. 1–4. (The clarinet and horn parts have been transposed to reflect the sounding pitches.) Copyright © 1949 by Merrymount Music Press. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Overall Cowell treats consonance flexibly, although some examples of a stricter handling remain. For example, in m. 2 on beat 3 the flute melody moves down by step from G, a diminished octave above G-sharp in the bassoon, to G-flat, while the bassoon part ascends by step to A forming a diminished seventh, which sounds as a major sixth. The consonant interval is followed by a diminished fifth; this dissonance results from the melody in the flute stepping down from G-flat to F while the melody in the bassoon ascends by step from A to B.

Varying degrees of Cowell's flexible approach to consonance are found in the excerpt (Example 6). In m. 3 the melody in the flute skips from F, a diminished octave above F-sharp in the bassoon, up to A, a minor third above it. The consonance resolves by step down to G, a minor ninth above F-sharp. At the beginning of m. 1 Cowell accompanies consecutive consonant intervals with disjunct motion. The melody in the flute, which begins on C, a minor third above A in the bassoon, leaps up to E-flat as the bassoon part steps down to G forming a minor sixth. The flute leaps back down to C, a fourth above G, and both parts move in contrary stepwise motion to B and G-sharp respectively, which results in a minor third. The excerpt features multiple instances of consecutive consonances between the upper parts and the melody in the bassoon.

Cowell also employed DC in a multimovement symphonic work that referenced America's musical heritage, notably eighteenth-century hymnody. He wrote Symphony No. 12, L. 830, for Leopold Stokowski over a two-year period from 1955 to 1956. Hugo Weisgall identified the first movement of the work as a hymn and compared its style to Cowell's Movement for String Quartet (1928); he also noted that the fourth movement is a hymn and fuguing tune, “remarkable for the chromatic character of its fuguing theme.”Footnote 75 The early American fuging tune, a genre most commonly associated with William Billings (1746–1800), has two distinct sections; the first is homorhythmic, and the second presents a theme that is imitated in all of the voices.Footnote 76 Referring to Cowell's entire twelfth symphony, Weisgall wrote: “It solves faultlessly the problems of applying chromatic dissonance techniques to the hymn-and-fuguing-tune genre.”Footnote 77

The first movement comprises a ternary form according to the plan outlined in Table 2. The A section includes two identical statements of a fifteen-measure passage, labeled in Table 2 as “subsection a,” which are played exclusively by the string section, including divisi first violins, second violins, viola, and cello; the bass enters in m. 12 and doubles the cello part an octave lower. In the repeat of “subsection a” (mm. 16–30) all parts are transposed a half-step lower. The B section is in a triple meter, which contrasts with the quadruple meter of the A sections, and the orchestration includes the woodwind and brass sections.

Table 2. Form of the First Movement in Henry Cowell's Symphony No. 12

The A section, of which mm. 1–8 are a representative sample, demonstrates Cowell's application of DC to a five-voice nonimitative polyphonic texture (Example 7). The melody in each part includes a balance of conjunct and disjunct motion, and the combination of all five parts results in dissonant and consonant relationships among the voices. Each vertical sonority features at least one tone that is dissonant against the bottom voice, and often other dissonant relationships exist within the sonority. For example, on the downbeat of m. 3, only the G in the viola is dissonant against A in the cello. The upper three parts include the tones C-sharp, C, and D, which produce a major third, minor third, and perfect fourth, respectively. However, C-sharp in the second violin is an augmented fourth above G in the viola; C in the first violin is a diminished octave above the C-sharp in the second violin; and D in the first violin is a major second above C and a minor ninth above C-sharp.

Example 7. Henry Cowell, Symphony No. 12 (1955–56), mvt. 1, mm. 1–8. Copyright © 1960 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

In the first movement, Cowell handles some consonant intervals with strictest adherence to the guidelines, (i.e., they are preceded and followed by dissonant intervals and accompanied by stepwise melodic motion). For example, in m. 1 the lower first violin part begins on A, a minor sixth above C-sharp in the cello, and the consonance is followed by a diminished fifth, which is approached by step as the violin moves from A down to G. The melodies in both voices move down a half-step in parallel motion to G-flat and C, respectively, which creates a diminished fifth, and the melody in the lower first violin steps down to F, a perfect fourth above C. The consonance proceeds to a diminished fifth formed by F being suspended over the bar line, while the melody in the cello moves down by step to B.

Overall Cowell's treatment of consonance in the first movement of Symphony No. 12 is flexible. Disjunct melodic motion is used to approach and/or leave a tone that is consonant against the bottom voice. For example, in m. 1 the melody in the upper first violin part begins on E, a minor third above C-sharp in the cello, and then leaps away from the consonant interval down to C-sharp, an augmented octave above the new tone in the cello, C. On beat 2 of m. 2 the major seventh created by A in the upper first violin and B-flat in the cello leads to a consonant interval; however, the melody in the first violin leaps from A up to D, a perfect fourth above the new bass note A. Many instances of consecutive consonant intervals occur within one of the upper melodies in relationship to the bass voice, and they range in length from two to five consonances: In m. 4 the melody in the lower first violin part proceeds from a perfect fifth to a major third, a minor third, and a perfect fourth. The melody in the viola part in m. 5 moves in consecutive parallel minor thirds against the cello; this succession of five total consonances begins with a major sixth between the viola and cello parts on the last beat of m. 4. Consecutive consonances also occur simultaneously. For example, the melody in the viola part in mm.1–2 features four consonant intervals against the cello comprising alternating minor and major thirds. Overlapping this series of consecutive consonances is the melody in the second violin, which beginning on beat 3 of m. 1 features three consecutive consonant intervals against the bass voice: a major sixth, minor sixth, and perfect fifth. The consecutive consonances and disjunct melodic motion accompanying consonant intervals probably resulted from Cowell focusing primarily on writing independent melodic lines.Footnote 78

In addition to using DC in his symphonic works, Cowell continued to employ the method in chamber genres, more specifically in the classical piano trio. He wrote Trio in Nine Short Movements, L. 941, in 1965 for the Hans J. Cohn Music Foundation.Footnote 79 Most of the movements betray the influence of DC, demonstrating that even at the end of his life Cowell still valued the technique as a viable option to suit his compositional aesthetic.

An excerpt from the fifth movement (Example 8) features the influence of DC in the violin and cello parts; the piano is tacit. The melodies comprise both conjunct and disjunct motion. The intervals between the voices include consonance and dissonance; each vertical sonority usually includes at least one dissonant interval, although there are some exceptions. For example, in m. 19 the downbeat comprises a perfect octave and minor sixth above F in the cello, and beat 3 features a minor sixth and perfect fourth above F. In m. 24 the downbeat includes a minor sixth and minor third above the bass note, A, and the second half of beat 3 features a perfect fifth and major third above F.

Example 8. Henry Cowell, Trio in Nine Short Movements (1965), mvt. 5, mm. 17–24. Copyright © 1968 by C. F. Peters Corporation. All rights reserved. Used by kind permission.

Cowell does occasionally handle consonant intervals strictly: They are preceded and followed by dissonant intervals and accompanied by stepwise melodic motion. For example, in m. 21, the top voice moves by step from B-flat, a minor seventh above C, to C, a perfect octave above the bass note, to D-flat, a minor ninth above C. More often, though, consonances are not approached or left by conjunct motion; consecutive consonances also exist within the various parts. Such flexibility likely resulted from Cowell's focusing on writing independent melodies rather than focusing exclusively on the intervals and voice leading produced by the counterpoint.

Summary

As the preceding discussion demonstrates, Cowell's personal notebook dating from his studies at Berkeley (1914–17) exemplifies his active role in the early development of DC and reveals him to be a systematic and tenacious theorist and composer, who valued tradition and advocated the practical application of new theoretical ideas. He laid out principles for a compositional practice that subverted traditional counterpoint, and he explored their application in forty-three didactic exercises; this practical experience revealed various issues associated with the guidelines. In addition to his academic inquiries into DC, Cowell utilized the method in compositions that date from 1916 to 1965, which suggests the high regard in which he held the technique throughout his career. Cowell felt free to use the guidelines he helped develop in a flexible manner that was informed by his personal compositional aesthetic—not unlike the way in which Schoenberg employed the twelve-tone method. In March 1935 Cowell told a San Francisco concert audience that he considered Schoenberg “the most noted composer since Beethoven.”Footnote 80 Perhaps Schoenberg's flexible use of the twelve-tone system served Cowell as a model for his own application of the guidelines that he created for DC. Furthermore, Cowell's dissemination of DC in private lessons and classroom teaching provided a life for the compositional method that extended well beyond his own work with it.

Several examples of other composers' interactions with DC illustrate the widespread influence of the ideas in Cowell's notebook. Crawford disseminated the technique to some of her composition students, including Vivian Fine and Johanna Beyer, who studied with her in the early 1930s, and Chuck Miller, who studied with her during the mid- to late 1940s.Footnote 81 Additionally, Tick has established that Crawford shared the technique in her discussions with various composers she met while in Europe in 1931 on a Guggenheim Fellowship, including Josef Rufer, Alban Berg, Josef Hauer, Tibor Harsányi, and Imre Weisshaus.Footnote 82 Although Fine used DC in several works, it was her Four Pieces for Two Flutes (1930) that won the praise of Wallingford Riegger in his 1958 article for the Bulletin for the American Composers' Alliance; he stated, “At the age of seventeen she already showed her mastery of dissonant counterpoint in her charming Four Pieces for Two Flutes.”Footnote 83 Gerald Strang used DC along with tone clusters in Eleven (1931), which was not only dedicated to Cowell but also published by Cowell in New Music Quarterly.Footnote 84 In addition to Beyer's use of the technique in various compositions, she also wrote about DC in her program notes for two Composers' Forum Laboratory concerts presented under the aegis of the Works Progress Administration's Federal Music Project. In the notes for a concert on 20 May 1936, Beyer discussed her use of the compositional method in Excerpts from Piano Suites (1930–35), Suite for Soprano and Clarinet (1934), and String Quartet (1933–34).Footnote 85 Beyer's program notes for a concert held on 19 May 1937 describe her application of DC in the Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1936), Excerpts from Piano Suites (1930–36), and Quintet for Woodwinds (1933).Footnote 86 Beyer also taught piano lessons, which provided her with another forum to disseminate DC; she used the technique in two of her own pieces labeled “Lento” and “half note = 56” that she included in her Piano Book: Classic – Romantic – Modern.”Footnote 87 Frank Wigglesworth, who studied with Cowell in 1940 and used DC in some of his works, taught Cowell's “Materials of Modern Music” class at the New School for Social Research for three consecutive semesters: Spring 1956, Fall 1956, and Spring 1957.Footnote 88 The description in the New School Bulletin lists DC as one of the topics covered in the course. Finally during the late-1990s and early-2000s James Tenney not only used DC in several works whose titles pay tribute to Crawford and Seeger (Diaphonic Study and Seegersong #1), but he also taught the compositional technique in his courses at York University in Toronto and the California Institute of the Arts.Footnote 89

This reassessment of DC and Henry Cowell challenges us to acknowledge the gaps present in our conceptualization of twentieth-century Western, and more specifically American, musical culture. History is complicated, and there remains a richness of archival material to be investigated, evaluated, interpreted, and discussed. In this case study, the evidence compels us to continue searching through the archives for new documents that invite a richer, more nuanced view of history and those who have made it.

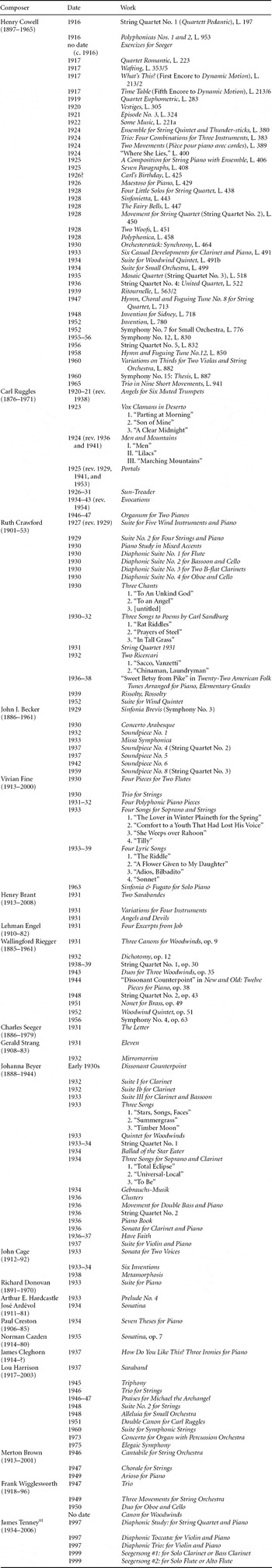

Appendix A: Works Employing Dissonant Counterpoint TechniquesFootnote 90

Appendix B: Henry Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint Notebook

[Inside of the Front Cover]

Dissonant governed counterpointFootnote 92

Dissonance is accepted for foundation of counterpoint because it is emotionally stronger than consonance and because it is the next historical step. the first counter point was made in the most consonant intervals perfect 8ths, 5ths, 4ths. ThenFootnote 93 these were used very sparingly in favor of more dissonant intervals major and minor 3ds and 6ths. the next logical step in carrying out the principal already indicated is to use perfect intervals practically never, 3ds and 6ths only by careful preparation and use 9ths and 7ths as the foundation of to work upon the major 7th minor 2nd and the minor 9th and their inversions are used as the foundation, as these are the strongest dissonances. the minor 7, and major 2 and 9th and the aug. 4 can be used as essential intervals when it [is] practical to use them for good voice leading or variety [continued on] last pageFootnote 94

[Page 1 recto]

[Exercise 1]

[Exercise 2]

[Exercise 3]

[Exercise 4]

[Exercise 5]

[Page 1 verso]

[Exercise 6]

[Exercise 7]

[Exercise 8]

[Page 2 recto]

[Exercise 9]

[Exercise 10]

[Exercise 11]

[Exercise 12]

[Page 2 verso]

[Exercise 13]

[Exercise 14]

[Exercise 15]

[Exercise 16]

[Page 3 recto]

[Exercise 17]

[Exercise 18]

[Exercise 19]

[Page 3 verso]

[Exercise 20]

[Exercise 21]

[Exercise 22]

[Exercise 23]

[Page 4 recto]

[Exercise 24]

[Exercise 25]

[Page 4 verso]

[Exercise 26]

[Exercise 27]

[Exercise 28]

[Page 5 recto]

[Exercise 29]

[Exercise 30]

[Exercise 31]

[Page 5 verso]

[Exercise 32]

[Exercise 33]

[Page 6 recto]

[Exercise 34]

[Exercise 35]

[Exercise 36]

[Page 6 verso]

[Exercise 37]

[Exercise 38]

[Page 7 recto]

[Exercise 39]

[Exercise 40]

[Page 7 verso]

[Exercise 41]

[Page 17 verso]

[Exercise 42]

[Exercise 43]

[Inside of the Back Cover]

aug. and dim. intervals enharmonically the same as consonances had better not be used as essential dissonances because although in reality dissonant, they are apt to be mistaken remind[ing] th[e] listener of their enharmonic equivalent, unless used in just the right surroundings to bring out their true character. The chromatic scale is used because it is the only scale in which –––Footnote 95 has more varied possibility than any other scale, and is one of the few scales in which dissonant counterpoint is practical. Because the voice is the foundation of all music, and the only instrument which will inevitably last, we will consider our work as being written for voices. the voice leading of strict counterpoint, which is based on vocal difficultys, is preferable only with the full addition of chrom. semitones and an occasionalFootnote 96 use of augmented intervals and minor 7ths if in good melodic curves. In three or more parts the aim is to have all parts in dissonance to each other. between an inner and top part may be consonance if there is somewhere a diss. preferably from the bass. If weak dissonance only is used all parts should be dissonant to each other. only intervals and melody are considered to the exclusion of Durch Harmonie principals. for the sake of clarity crossed and over lapped parts are only used in emergencies.Footnote 97

Critical Apparatus for Henry Cowell's Dissonant Counterpoint Notebook

The source for the edition is a single notebook with writing in pencil; it is contained in box 31, folder 4 of the Henry Cowell Archive at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In my report all passages in quotation marks constitute marginalia written in Cowell's handwriting.

Page 1 recto

Above Ex. 1 – “Because it is a strong diss and the extreme compass of the chrom. scale before a repetition is started, the maj 7th is a very good interval to start on. the minor 9th is also a possibility”

Ex. 1 – In m. 7, the upper voice, there is also E written a perfect fourth below the A, but it is crossed out.

Between the staves of Ex. 1 – “a return is made to the same point for the sake of balance.” Down the right side of the margin that occupies the space after Ex. 1 and Ex. 2: “contrary motion is desirable only 3 consecutive are allowed of any kind only 7ths and 9ths may be written consecutively occasionly aug. 4., consec. 2nds are muddy and blur the clarity of the parts 7ths in 2 moves sometimes 7ths more rarely as the smoothness is____.” The last two words are indecipherable.

Between Ex. 1 and Ex. 2 – “no consonance possible in first species, except rarely an enharmonic cons.”

Ex. 2 – In m. 1, the upper voice, a whole-note C-sharp and whole-note D are written an octave and ninth, respectively, above the middle C-sharp. The two higher tones are both crossed out.

Ex. 2 and Ex. 3 are next to each other in the same system in the original source.

Ex. 4 and Ex. 5 are also next to each other in the same system in the original source.

Ex. 4 – In m. 8, the top voice, it appears that the whole-note B-natural is written over the top of a whole-note C-natural, a minor second above it; the B-natural note head is darker.

Ex. 5 – In m. 7, the bottom voice, the whole-note A is written over the top of a whole-note B, a major second above it; the A note head is larger and darker.

Page 1 verso

Ex. 7 – “C.F.” is written and then crossed out above the top staff. In m. 8, the bottom voice, a whole-note G is written over a whole-note F, a major second below it. In m. 12, the bottom voice, a whole-note C is written over a whole-note B, a minor second below it. The exercise does not conclude with a double bar line.

Page 2 recto

In the original source Ex. 9 and Ex. 10 are next to each other in the same system.

Page 2 verso

In the original source Ex. 13 and Ex. 14 are next to each other in the same system. Ex. 15 and Ex. 16 each fit into their own single system in the original source. Below Ex. 16 – “skip to consonance justifiable as changing notes”

Page 3 recto

Above Ex. 17 and continuing along the right side of the exercise – “owing to difficult[y] of getting this species the opening often must begin on a weak dissonance - an enharmonic dissonance may be skipped from in cases of emergency notes may be enharmonically changed over the bar if convenient so as to keep concord moving.”

Ex. 17 – In m. 7, the top voice, underneath the half-note D-flat was written a half-note C; the half-note C was erased.

Ex. 18 – In mm. 1–2, the bottom voice, underneath the half-note G-flat tied to a half-note G-flat was written half-note F tied to half-note F; both tied half-note F's are erased. In m. 5, the upper voice, a whole-note A-flat is written over a whole-note B, an augmented second above it; the A- flat note-head is larger. In m. 8, the bottom voice, there are erased notes under the half-note C and half-note D-flat, but I cannot make out what was written there previously. In m. 9, the bottom voice, underneath the whole-note C-flat was written whole-note B-flat, a minor second below it; the B-flat was erased.

All measures of Ex. 19 fit into a single system on the page.