Comic blackface minstrelsy appeared in theaters during the 1820s and 1830s as entr'actes or as the featured songs and dances of individual performers. Arising from folk theater, such as callithumpian festivals, these early performances often functioned as carnivalesque and potentially subversive expressions of white working-class engagement with black culture.1

Dale Cockrell, Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), chaps. 1–3; W. T. Lhamon Jr., Jump Jim Crow: Lost Plays, Lyrics, and Street Prose of the First Atlantic Popular Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), Introduction; W. T. Lhamon Jr., Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), chap. 1.

William J. Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 9.

This (or any) list of minstrel show troupes should be understood as fluid, as troupe names and personnel changed with staggering frequency. “Representative Minstrel Companies and Personnel in Playbills and Newspaper Advertisements, 1843–60,” Appendix A, in Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, 355–63, is quite helpful in this regard.

See Hans Nathan, Dan Emmett and the Rise of Early Negro Minstrelsy (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1962), chap. 11, for a discussion of the competition between the Virginia Minstrels and Christy's Minstrels for the title of “originator of negro minstrelsy.” Christy's Minstrels disbanded in July 1854, primarily because of the departure in 1853 of George Christy (1827–1868, né George Harrington), who went on to form George Christy and Wood's Minstrels.

Lhamon, Jump Jim Crow, Introduction. Rice is best known as creator of the “Jim Crow” character.

Cockrell, Demons of Disorder, provides a comprehensive biography of Dixon.

Minstrels' mainstreaming efforts were facilitated by their borrowings from established tropes and genres, including opera. English opera had been popular with antebellum audiences since the 1820s, and in 1847, foreign language opera had gained a permanent foothold in the United States, because the previous pattern of intermittent appearances of Italian opera troupes was replaced with a consistent presence of multiple troupes each year.7

Katherine K. Preston, Opera on the Road: Traveling Opera Troupes in the United States, 1825–60 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 100, 141.

“Songsters” are pocket-sized books that normally publish only song texts. In this article, parody refers to a literary imitation of a previously existing text, and burlesque refers to theatrical works that use comic mimicry to lampoon their subjects. Opera parody songs may have been performed as mini-burlesques, but as they are extant only as texts, and because these texts are drawn directly from their subjects, it seems most appropriate to refer to them as parodies.

Frank Dumont, The Witmark Amateur Minstrel Guide and Burnt Cork Encyclopedia, rev. edn. (New York: M. Witmark & Sons, 1927). Little has been published on postbellum minstrels' interactions with opera, so it is difficult to state with certainty that the 1850s had the greatest concentration of blackface opera burlesque. Several postbellum plays that use operatic burlesque are reprinted in This Grotesque Essence: Plays from the American Minstrel Stage, ed. Gary Engle (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978).

The success of blackface opera burlesque challenges received notions about the statuses of minstrelsy and opera. Several valuable studies of minstrelsy place it as a working class genre, and theatrical histories describe the rise of elitist entertainment (most notably, foreign language opera) at mid-century.10

Studies that describe minstrelsy as a working-class genre include Cockrell, Demons of Disorder; Lhamon, Jump Jim Crow; Lhamon, Raising Cain; Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); and Robert Toll, Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974). Cockrell and Lhamon deal primarily with early or folk types of minstrelsy, and although Lott's central argument is the use of minstrelsy in the formation of working-class culture, he allows for a middle-class presence by positioning minstrelsy's racism as a means for white community building across class lines: “The minstrel show…brought various classes and class fractions together, here through a common racial hostility” (154–55). The rise of elite entertainments is found in Lawrence Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988); Bruce McConachie, “New York Operagoing, 1825–50: Creating an Elite Social Ritual,” American Music 6/2 (Summer 1988): 181–92.

“The Great Theatres—Opera Excitement,” New York Herald, 13 December 1847; “Theatricals, Murder, and Ruin,” New York Herald, 17 December 1847. See also Vera Brodsky Lawrence, Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong, vol. 1, Resonances, 1836–1849 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 457–66.

Minstrels' burlesques were not anomalous. In the picturesque words of historian Constance Rourke, “Through the '40s and '50s the spirit of burlesque was abroad in the land like a powerful genie let out of a windbag, finding a wealth of yielding subjects.”12

Constance Rourke, American Humor: A Study of the National Character (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1931), 101.

According to his unpublished memoirs, minstrel troupe manager Samuel S. Sanford (1821–1905) saw English opera star Anna Bishop (1810–84) perform in a burlesque of La sonnambula titled Lossnomula Poor House in Liverpool in 1847. See Jimmy Dalton Baines, “Samuel S. Sanford and Negro Minstrelsy” (Ph.D. diss., Tulane University, 1967), 32. Later, during a tour of the United States, Bishop performed in a “musical frolic” in San Francisco. The frolic included a burlesque of the first act of Norma in which Bishop took the male role of Pollio and performed it flirtatiously, “à la Don Giovanni,” while the role of Norma was performed by the baritone Herr Mengis. See George Martin, Verdi at the Golden Gate: Opera in San Francisco in the Gold Rush Years (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 85.

The performance history of La sonnambula in the United States is well documented by Preston, Opera on the Road, 19, 85–94; and Katherine K. Preston, “Between the Cracks: The Performance of English-Language Opera in Late Nineteenth-Century America,” American Music 21/3 (Fall 2003): 354.

Other examples of genre-crossing among theatrical performers are found in Katherine K. Preston, “‘Dear Miss Ober’: Music Management and the Interconnections of Musical Culture in the United States, 1876–1883,” in European Music and Musicians in New York City, 1840–1900, ed. John Graziano, 273–98 (Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester Press, 2006).

Information on performances at the Olympic is from David L. Rinear, The Temple of Momus: Mitchell's Olympic Theater (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1987), 15, 28–29; and Rourke, American Humor, 120.

Po-ca-hon-tas remained a regular part of the repertory until the 1880s. It is reprinted in Dramas from the American Theatre 1762–1909, ed. Richard Moody (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1966), 403–21. For examples of the events listed here, see 408–11. Analyses are provided by William Brooks, “Pocahontas: Her Life and Times,” American Music 2/4 (Winter 1984): 19–20, 28–29, 34; and Deane Root, “Music Research in Nineteenth-Century Theater: or, The Case of a Burlesquer, a Baker, and a Pantomime Maker,” in Vistas of American Music: Essays and Compositions in Honor of William K. Kearns, ed. Susan L. Porter and John Graziano (Warren, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 1999), 187. Levine's Highbrow/Lowbrow discusses the popularity of Shakespeare's plays during the antebellum period (chap. 1). See Robert C. Allen, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 54, for this interpretation of “fashionables.”

Such American pieces as Po-ca-hon-tas were part of a British theatrical tradition that was at least a century old. Ballad operas, for example, used many of the same transformation methods found in American burlesques, including song parodies.18

An early example is “My Heart Was So Free,” a parody of Baroque simile arias, from John Gay's The Beggar's Opera (1728). The Beggar's Opera was the most famous of ballad operas, and it was performed in the United States through the middle of the nineteenth century. Harold Gene Moss, in “Popular Music and the Ballad Opera,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 26/3 (Fall 1973): 365–82, provides a detailed study of “Sally in Our Alley,” a song with many incarnations during the eighteenth century.

Rinear, The Temple of Momus, 3–4, 8–10; Rita M. Plotnicki, “John Brougham: The Aristophanes of American Burlesque,” Journal of Popular Culture 12/3 (Winter 1978): 422; Brooks, Pochahontas, 20.

As theater historian Peter Buckley points out, “The lack of international copyright law enabled easy adaptations of British vehicles to local [i.e., American] humor.” See Peter G. Buckley, “Paratheatricals and Popular Stage Entertainment,” in The Cambridge History of American Theatre, ed. Don B. Wilmeth and Christopher Bigsby (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 1:458.

The techniques of British burlesque (such as song parody and an unpredictable mingling of timely subjects) were used extensively in blackface opera burlesque. But the familiarity of burlesque for antebellum audiences does not in itself explain the commercial success of opera in blackface. There were other ways in which minstrels engaged with the mainstream of popular culture, including the establishment of a standardized blackface context, a European-based repertory, advertising that mimicked the promotional language of legitimate entertainments, and the manipulation of sentimentality and nationalism, both important themes of antebellum popular culture. Each of these is exemplified by blackface opera parodies, and each merits further explanation.

“Blackface context” refers not only to the use of facial makeup but also to other standard features of minstrel show performance. These include language devices such as an invented theatrical dialect, malapropism, and nonsense; the visual spectacle of the mask and of slapstick physical comedy; and bodily transformation via primitivism and grotesquerie.21

“Grotesquerie” is described in Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Helene Iswolsky (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1968), 316–20. Bakhtin's work in grotesquerie is influential in recent minstrel show scholarship; see Cockrell, Demons of Disorder, xiii.

Minstrelsy has been variously described as educator, social inverter, provider of a national art, a definer of class structures, object of desire and of disgust, and inventor of whiteness (through its invention of blackness). All of these explanations are valuable, even as they sometimes contradict one another. See Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, 268, 353; Lott, Love and Theft, 68, 149–56; and David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991), 115–16.

Quoted in Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, 106.

Lhamon, Jump Jim Crow, 15–19.

Minstrels used the conventionalized blackface context to present a great variety of subjects, including European musical forms.25

Similarly, Eric Lott refers to “white ventriloquism through black art forms” in his discussion of the use of blackface to represent various ethnicities, particularly Irish. Lott, Love and Theft, 94–95.

Nathan, Dan Emmett, chap. 12, provides an exhaustive survey of the roots of early minstrel show songs, tracing many of them to the folk music of the British Isles. Dena Epstein's Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977) briefly explains and debunks the belief held by many nineteenth-century observers that slaves created minstrel show songs (241–42). Charles Hamm, in Music in the New World (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), states, “The minstrel show was created by white Americans…for the amusement of other white Americans…the songs they sang and danced to had little to do with the music of black Americans of the day” (183).

Carl Wittke, Tambo and Bones: A History of the American Minstrel Stage (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1930), 39–40, reprints a list from The New York Clipper from 1858 providing the “leading companies in existence at the close of the 'fifties” (57). The list includes Buckley's Serenaders and other troupes known for their opera parodies. The fact that not all minstrel troupes carried similar repertories is illustrated by Charley Fox's Ethiopian Songster (1858), which contains no opera parodies.

“The Trovatore Buckleyfied,” reprinted from the New Orleans Picayune in Dwight's Journal of Music, 22 October 1859. See also Vera Brodsky Lawrence, Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong, vol. 2, Reverberations, 1850–1856 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 545.

Minstrels' mainstream status is further suggested by the language of their advertisements. A performance early in 1843 by a group of four previously unattached performers, renamed the Virginia Minstrels, was promoted as follows:

First Night of the novel, grotesque, original, and surprisingly melodious Ethiopian band…being an exclusively musical entertainment…entirely exempt from the vulgarities and other objectionable features which have hitherto characterized negro extravaganzas.29

“Amusements: Bowery Amphitheater,” New York Herald, 6 February 1843.

The language of this advertisement attempts to separate this new kind of minstrelsy—the concert troupe—from the previous entr'actes and circus acts. A few years later, performances by Kneass's Band of Musicians, who presented blackface operatic parodies at Palmo's Opera House, are described as “amusing and chaste” and their audiences as “numerous and respectable.”30

“Amusements,” New York Herald, 17 February 1845; “Palmo's Theatre,” New York Herald, 26 February 1845.

Advertisements section of the New York Herald in autumn 1847.

Playbill for Christy's Minstrels, Mechanics' Hall, 26 February 1849.

A similar argument, but with a focus on sheet music, is found in Stephanie Elaine Dunson, “The Minstrel in the Parlor: Nineteenth-Century Sheet Music and the Domestication of Blackface Minstrelsy” (Ph.D. diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2004).

Sentimentality was part of the fabric of antebellum popular culture. Songs, poems, operatic plots, and melodramas were replete with nostalgia (for a place or a person), pain of separation (via death or geographic distance), and a desire for the simple comforts of home and the familiar.34

Charles Hamm, Yesterdays: Popular Song in America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1979), 54, 182.

Information on blackface characters is from Toll, Blacking Up, 29, 37, 53–54, 75–76, 140.

Robert B. Winans, “Early Minstrel Show Music,” in Musical Theater in America, ed. Glenn Loney (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1984), 83.

Nationalism was of primary importance to many antebellum performers and commentators. Discussions of the relationships between the United States and Europe appear regularly in antebellum newspapers. European performances were widely advertised, and articles appear relatively frequently on the condition of the arts in the United States as compared with Europe.37

Many issues of The Spirit of the Times, a popular New York paper, ran a “Foreign Theatrical Intelligence” (or some similar title) column.

For some examples of this attitude and its ramifications, see “Is America a Musical Country at Present? And Why Is it Not?,” New York Herald, 28 November 1844; Karen Ahlquist, Democracy at the Opera: Music, Theater, and Culture in New York City, 1815–60 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 63–64; David Grimsted, Melodrama Unveiled: American Theater and Culture, 1800–1850 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), 68–73, 138–39; Hamm, Yesterdays, 157–58; Preston, Opera on the Road, 140; and Toll, Blacking Up, 108.

Quoted in Lawrence, Strong on Music: Resonances, 343.

After our country men had, by force of native genius in the arts, arms, science, philosophy and poetry, &c, &c, confuted the stale cant of our European detractors that nothing original could emanate from Americans—the next cry was, that we have no NATIVE MUSIC;…until our countrymen found a triumphant vindicating APOLLO in the genius of E. P. Christy, who…was the first to catch our native airs as they floated wildly, or hummed in the balmy breezes of the sunny south.

“Negro Minstrelsy—Ancient and Modern,” Putnam's Monthly 5/15 (January 1855): 73, 75.

By the late 1840s, minstrel troupes could enter the mainstream of antebellum entertainments. This move was accomplished in part by the establishment of a standardized blackface context, the adoption of a European repertory, the utilization of advertising that appropriated the moral language of the burgeoning middle class, and the manipulation of sentimentality and nationalism. Blackface opera burlesques exemplify these, and they also demonstrate that minstrels used many of the same methods as the burlesque tradition inherited from England and continued in the United States by artists such as Mitchell and Brougham.

Most full-length blackface opera burlesques do not survive, but individual song parodies provide considerable insight into minstrels' use of opera as part of the mainstreaming process.41

Musical notation for antebellum burlesqued operas usually was not published, and manuscripts, or even prompt books or outlines, are elusive. Root, “Music Research in Nineteenth-Century Theater,” 185, provides a convincing explanation—the nature of burlesque itself, with its collage approach to already published subjects—for the lack of published musical burlesques.

For more information on the popularity and performance history of The Bohemian Girl and the popularity of “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls,” see Lawrence, Strong on Music: Resonances, 267–29, 524; Preston, Opera on the Road, 221, 228–29; and Preston, “Between the Cracks,” 354.

“I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” may have been created by Nelson Kneass (1823–68).43

“I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” and variants are in the songsters My Old Dad's Woolly Headed Screamer (1844), Christy's Nigga Songster (n.d.), The Forget Me Not Songster (1847), and Nigger Melodies (n.d.).

“Amusements,”New York Herald, 7 February and 20 February 1845.

Renee Lapp Norris, “‘Black Opera’: Antebellum Blackface Minstrelsy and European Opera” (Ph.D. diss., University of Maryland at College Park, 2001), 34–35, 74–75. See also Ernest C. Krohn, “Nelson Kneass: Minstrel Singer and Composer,” Yearbook for Inter-American Musical Research 7 (1971): 19–21.

See Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, 53–54.

The text for “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls” is provided under the text of “I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls.”

Example 1. “I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” from the songster My Old Dad's Woolly Headed Screamer (c.1844) set to the music of “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls” (New York:Atwill, n.d.).

Confirming the text setting of Example 1, extant musical publications of “I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” use the melody of “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls.”48

“I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” is in musical score in two publications. One lacks any publication information, although it is within a collection, housed at Duke University, of songs that can be dated between 1827 and the mid-1840s. The second is The Ethiopian Glee Book, vol. 1 (Boston: Elias Howe, 1847), which places the melody in the treble part of a four-part arrangement.

Fidelity to the music of the original allowed an easy parody of the soprano Anne Seguin and her role of Arline. In The Bohemian Girl, Arline, a Count's daughter, is kidnapped by gypsies as a child. She is raised by the gypsies, and as she grows up she has flashbacks of her former privileged life. The plot builds to Arline's realization of her noble birth, and the story's happy ending is created by Arline's marriage to her gypsy lover, who, fortuitously, also is revealed to be a member of the nobility. In contrast to the opera's Arline (who dreams of marble halls, servants, and a noble family) is the female character in the parody (who aspires to work in a hotel kitchen, have abundant and varied food, and to be with “Coon”); Figure 1 provides a text comparison.

Comparison of the first verse of “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls” (New York: Atwill, n.d.) and the first two stanzas of “De Nigga Gal's Dream; Or, I Loved Coon Still de Same,” My Old Dad's Woolly Headed Screamer (ca. 1844).

Personal fulfillment—which audiences knew was consummated for Arline in Balfe's opera—was, for “De Nigga Gal,” to be a kitchen servant. This debasement is reinforced by a lyric that replaces riches with “wittals ob all kinds.” Minstrel show texts are replete with food references that enforce the primitiveness of blackface characters (especially when the protagonists catch and prepare their own food).49

Indeed, food-based texts are on adjacent pages to “De Nigga Gal's Dream” in the songster, My Old Dad's Wooly Headed Screamer: “Tis Sad to Leabe Our Tater Land” and “De Old Roast Possum.” The former is a parody of another aria from Balfe's Bohemian Girl, “Tis Sad to Leave Our Fatherland.”

The racist language of this lyric is not unusual for the time period; see Roediger, Wages of Whiteness, 98–99, for the evolution of terms such as “buck” and “coon” from non-black-identifying to clearly anti-black during the nineteenth century. It is not clear why some words, such as dreamed, are consistently italicized in nearly every text source for this parody.

“I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” illustrates many of the elements of antebellum theatrical parody. Performed soon after the original was premiered, it was timely and easily parodied the opera's characters and the performers. The parody maintains the framework (in this case, the music and poetic structure) of the original but places it in a new guise (a blackface context featuring low social status and primitivistic food references). “I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” manipulated sentimentality via a singing female character. She was a contradiction: although a low, comic wench, her story maintains the “we were meant for each other” romance of the original. This commingling of sentimentality and comedy allowed for diverse interpretations of “De Nigga Gal” (pathetic, laughable, erotic), which in turn allowed minstrels to draw larger and more varied audiences.

Another opera parody song, “See! Sir, See!,” uses similar methods as “I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” but is musically more complex. “See! Sir, See!” is based on “Vi ravviso o luoghi ameni” (“As I View These Scenes So Charming” in English-language publications) from the first act of La sonnambula, where it is sung as a cavatina by Count Rodolpho. In this aria, Rodolpho nostalgically describes his childhood home and his long-lost love. Such stories met antebellum Americans' expectations for sentimental song, and numerous extant antebellum piano/vocal sheet music publications of “As I View These Scenes So Charming” attest to its popularity.51

This study employs two of these publications: “As I View These Scenes So Charming, Sung with Great Applause by Mr. Brough, in Bellini's Celebrated Opera La Sonnambula, Composed by V. Bellini” (Boston: C. Bradlee, n.d.) and “As I View These Scenes So Charming, Vi ravviso o luoghi amenir [sic] Air in the celebrated Opera La Sonnambula, Composed by Bellini” (Philadelphia: Fiot, Meignen & Co., n.d.), as well as a complete piano/vocal score for La sonnambula published in the nineteenth century: Vincenzo Bellini, La Sonnambula, with Italian and English Words (Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co., n.d.).

“See! Sir, See!” is extant only in songsters, two of which attribute it to Kneass.52

Songsters providing texts for “See! Sir, See!” include Christy's Plantation Melodies (1854), George Christy & Wood's Melodies (1854), The Ethiopian Serenaders' Own Book (1857), Wood's New Plantation Melodies (1862), and White's New Ethiopian Song Book (n.d.). Two of these songsters, George Christy & Wood's Melodies and White's New Ethiopian Song Book, were reprinted in Christy's and White's Ethiopian Melodies, a compilation of five songsters (n.d.). The attributions to Kneass as arranger for “See! Sir, See!” are from White's New Ethiopian Song Book and Wood's New Plantation Melodies. Baines, in “Samuel S. Sanford and Negro Minstrelsy,” states that a published program for an 1853 afterpiece, La Sonnambula, performed by Sanford's Minstrels (also known as the New Orleans Opera Troupe), lists Kneass as arranger and that he based La Sonnambula on a script used by the Seguins (120).

Lo! Som am de Beauties was performed at Palmo's (where the original Italian La sonnambula was premiered in 1844) and Som-Am-Bull-Ole (a title with reference to the famous touring Norwegian violinist Ole Bull) was performed with E. P. Christy, founder of Christy's Minstrels, at the Alhambra in New York. “Amusements,”New York Herald, 23 February 1845; “Palmo's Theatre” (a review of Lo! Som am de Beauties), New York Herald, 26 February 1845; Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, 12.

In my research at the Harvard Theatre Collection, “See! Sir, See!” was on 6 percent of the playbills I surveyed. Mahar located it on 16 percent of the playbills he surveyed (“‘Sing, Darkies, Sing’: The Real Vs. Imagined Repertoires of Early Blackface Minstrelsy,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the Sonneck Society for American Music, Washington, D.C., March 1996); and Winans, “Early Minstrel Show Music,” found it on 11 percent and lists it as a “minstrel show hit” (81). Another well-known opera parody song from La sonnambula is “The Phantom Chorus,” performed with some frequency by Christy's Minstrels at midcentury. “The Phantom Chorus” is analyzed in Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, 119–26.

Most opera parody songs, including “I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls,” simply borrow the music of an opera aria and parody its text. “See! Sir, See!” surpasses such pieces, as well as sheet music publications of “As I View These Scenes So Charming,” in its comprehensiveness. Sheet music for “As I View These Scenes So Charming” typically includes only the cantabile and cabaletta of the aria. The formatting and abnormally long length of the songster text for “See! Sir, See!” suggest that Kneass used the structure of the entire number (scena, cantabile, tempo di mezzo, and cabaletta) to create “See! Sir, See!,” and that he superimposed some popular minstrel show tunes onto the operatic form. Although the music for “See! Sir, See!” apparently never was published, its text suggests some possibilities for reconstruction, which are realized here.

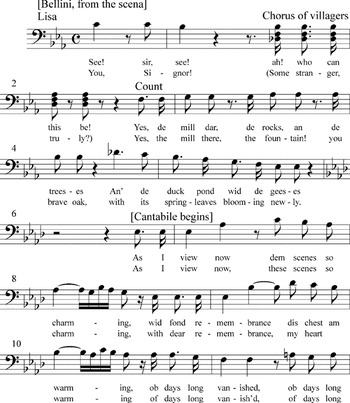

“See! Sir, See!” begins with an excerpt from the end of Bellini's scena followed by a parody of the Count's cantabile, “As I View These Scenes So Charming.” The text for the “cantabile” of “See! Sir, See!” is an obvious parody of “As I View These Scenes So Charming,” and it is easily set to the operatic melody. The music shown in Example 2 was written by Bellini, and the text is taken from “See! Sir, See!” with the English translation of the operatic text underneath.55

The English translation of the opera's text, which is under the text from “See! Sir, See!,” is taken from a nineteenth-century piano/vocal score for the entire opera and from sheet music for “As I View These Scenes So Charming.”

Example 2. Opening of “See! Sir, See!” set to music of “Vi ravviso, o luoghi ameni” from Bellini's La sonnambula. (Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co., n.d.)

At the end of the cantabile, “See! Sir, See!” retains the structure of Bellini's aria by continuing with a quasi “tempo di mezzo” that incorporates a chorus and duet (mimicking the villagers in the original opera) with the Count's solo. The text in this section of “See! Sir, See!” alludes to two well-known minstrel show songs: “Whar Did You Come From” and “Lucy Neal.”56

Winans, “Early Minstrel Show Music,” found “Where Did You Come From” on 17 percent and “Lucy Neal” on 34 percent of playbills between 1843 and 1847 (82). According to S. Foster Damon, Series of Old American Songs (Providence: Brown University Library, 1936), #28, and Jon W. Finson, The Voices That Are Gone: Themes in Nineteenth-Century American Popular Song (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 178, “Whar Did You Come From” was published in 1840 and attributed to the banjoist Joel Walker Sweeney (ca. 1810–60). “Lucy Neal” is recorded on The Early Minstrel Show (New World Records 80338–2, 1998). The liner notes to this recording attribute the tune to J. P. Carter. According to Damon, “Miss Lucy Neale” was written by Jim Sanford and published in 1844. Lucy Neal was popular enough to be mentioned in other songs, such as “Picayune Butler” (Baltimore: F. D. Bentenn, 1847; accessed from the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, http://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/otcgi/llscgi60), where her death was caused by a “bulgine,” and the song also existed in instrumental dance versions. For an interpretation of “Lucy Neal” that connects sentimentality and abolitionism, see Hamm, Yesterdays, 136–67.

Because there was no obvious continuous melodic source for the operatic material of Examples 3 and 4 in the complete score for La sonnambula, these examples piece several of Bellini's melodies with the minstrel show songs.

Example 3. Opening of “tempo di mezzo” of “See! Sir, See!” set to music from “Vi ravviso, o luoghi ameni” from Bellini's La sonnambula and “Whar Did You Come From.”

Example 4. Continuation of “tempo di mezzo” of “See! Sir, See!” set to music from “Vi ravviso, o luoghi ameni” from Bellini's La sonnambula and “Lucy Neal.”

Example 4 begins with the last measure of “Whar Did You Come From” and continues with a solo by the Count.58

The English translation of the opera's text, which is under the text from “See! Sir, See!,” is from a nineteenth-century piano/vocal score for the entire opera.

The cabaletta, published as “Maid, those bright eyes” in English translation, is reworked as “Yes, dem dark eyes” in “See! Sir, See!” as shown in Example 5.59

The English translation of the opera's text, which is under the text from “See! Sir, See!,” is from sheet music for “As I View These Scenes So Charming.”

Example 5. Cabaletta of “Vi ravviso, o luoghi ameni” set to text from “See! Sir, See!”

Musically, the minstrel show songs and Bellini's aria are similar: both have relatively narrow ranges, frequently outline triads, use quickly repeating pitches, and, most important, feature long-short beat subdivisions, which for Bellini's aria are most striking in the cabaletta. Kneass's apparently keen ear for the stylistic similarities of “Vi ravviso, o luoghi ameni” and minstrel show melodies enabled him to combine these pieces into a musically comprehensible whole.

The texts of the minstrel show songs also are congruous with the text of the opera aria. In this scene in La sonnambula, Count Rodolpho returns to a country village he remembers from childhood. His arrival causes a stir among the villagers, who wonder why this stranger knows their village so well. Their consternation provides a ready justification for the integration of “Whar Did You Come From,” and this song's “rig-a-jig” refrain imbues “See! Sir, See!” with characteristic nonsense. The text of the next section continues to burlesque the sentimentality of the original by substituting Lucy Neal, a sentimental character on the minstrel show stage, for Amina, the opera's innocent sleepwalking heroine. Most versions of the song “Lucy Neal” were sung by Lucy Neal's husband, a slave who describes their separation when one of them was “sold away.” In some versions, Lucy dies. But it is also a comic song, because the musical style was more rhythmically energized than was typical for sentimental parlor songs, and some versions make fun of women's bodies in typical blackface fashion:

Miss Lucy dress'd in satin,

Its oh, she looked so sweet

I nebber should hab known her,

I soon cognized her feet.

Of course, the parody was not only musical and textual: the blackface context could have been manipulated in any number of ways to add humor and pathos. Mahar in Behind the Burnt Cork Mask proposes that Lucy Neal was dramatized by George Christy, one of the leading blackface female impersonators of the 1850s, in Christy's Minstrels performances of “See! Sir, See!” (112).

For explanation of the Astor Place riot, see Peter G. Buckley, “To the Opera House: Culture and Society in New York City, 1820–1860” (Ph.D. diss., State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1984); Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow, 64–66; Grimsted, Melodrama Unveiled, 68–73; and New York Herald, 8, 11, and 12 May 1849.

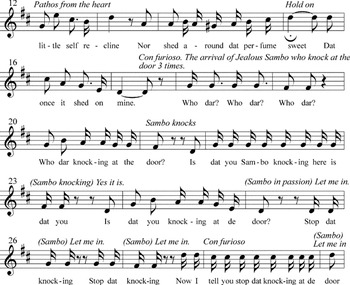

Most opera parody songs demonstrate minstrels' adaptive skills and suggest parity by creating contrafacta of operatic excerpts. The song “Stop Dat Knocking” also suggests skill and parity, but in a different manner than “I Dreamed Dat I Libed in Hotel Halls” and “See! Sir, See!” Instead of being a textual parody set to the music of opera arias, “Stop Dat Knocking” burlesques general Italian operatic musical gestures, which had themselves become stereotypical by midcentury. Because the burlesque of operatic conventions requires more intimate stylistic knowledge than a simple text parody, “Stop Dat Knocking” is particularly effective as a piece demonstrating minstrels' familiarity with European music.

“Stop Dat Knocking” was exceptionally popular, and it exists in several variants.62

“Stop Dat Knocking” was listed on nearly 25 percent of midcentury playbills. Winans, “Early Minstrel Show Music,” 91; Mahar, “Sing,” 11. As sheet music for piano and voice, “Stop Dat Knocking” was published in Boston by G. P. Reed in 1843 and in a revised version in 1847, in New York and Chicago by Richard A. Saalfield (n.d.), in New York by Vanderbeek (n.d.), and in the Ethiopian Glee Book, vol. 2 (1848). “Stop Dat Knocking” also was published in dance arrangements, usually quadrilles for piano solo. Its text is in the songsters White's New Illustrated Melodeon Song Book (1851), Christy's Plantation Melodies #1 (1851), The Ethiopian Serenaders Own Book (1854), and The Ethiopian Serenaders' Own Book (1857). “Stop Dat Knocking” was sometimes published as “Suzy Brown.” Norris, “‘Black Opera,’” 187–90.

Little is known of Winnemore other than his appearances with the Boston Minstrels and the Virginia Serenaders. His affiliations with these troupes began in 1843 and continued with apparently varying levels of activity through 1850. Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, 22, 355–56.

McConachie, “New York Operagoing, 1825–50,” 187.

Example 6. Excerpt from A. F. Winnemore, “Stop Dat Knocking” (Boston: Geo. P. Reed, 1843).

One of the primary differences between the 1843 and 1847 versions is the addition of multiple voice parts to the latter. In the 1847 version, instead of a “duett sung by one,” the voice parts increase from solo to duet to chorus. This type of increasingly thick vocal texture, although not unique to opera, is fundamental to many of its scenes. Many times such scenes in Italian opera accumulate with a “Rossini crescendo,” which is created through a series of repeated phrases that use not only a dynamic crescendo but also rhythmic subdivisions, higher pitches, and an increasingly dense texture to create a grand rush to the finish.65

J. Peter Burkholder, Donald Jay Grout, and Claude V. Palisca, A History of Western Music, 7th edn. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), 662.

The tempo and dynamic markings are not included in the G. P. Reed publication of the 1847 version; they are printed in an undated version arranged by one William Clifton and published by Vanderbeek. It is this version of the sheet music that was used in the recording of “Stop Dat Knocking” on The Early Minstrel Show.

Example 7. Excerpt from A. F. Winnemore, “Stop Dat Knocking at My Door” (Boston: G. P. Reed, 1847).

The text of “Stop Dat Knocking” appears to borrow from Thomas Dartmouth Rice's play Oh! Hush! Or, The Virginny Cupids! that dates from the 1830s.67

A full script for this play is found in Lhamon, Jump Jim Crow, 148–58. Oh Hush!, in turn, draws its situation from “Coal Black Rose,” one of the earliest known comic blackface songs. Damon, Series of Old American Songs, #13.

Cuff and Sam fall into two typical blackface characterizations: Cuff (or Gumbo or Jim Crow) represents poor, crippled characters who dressed in rags, and Sam (or Sambo or Zip Coon) is a dandy, an upper-class pretender. Unlike Sam, Cuff suffers no delusions regarding his low social status and is thus frequently given advantage over the dandy. For more information on blackface characterization, see Toll Blacking Up, chaps. 2–3.

Lhamon, Jump Jim Crow, 157.

Oh! take dat coon you gave me lub;

I'll hab it now no more

To one it now can only prove,

My days ob peace are o'er

Ibid., 425.

The fact that Rose is spurned in the 1843 version of “Stop Dat Knocking” suggests that she was a “funny old gal” character (i.e., she was comic, not sentimental). She is unattractive (“its head is like a dinner pot”) and unfaithful. In the 1847 version, Rose is replaced by the sentimental Suzy Brown, who is physically attractive and faithful. Yet both female characters, like Lucy Neal in “See! Sir, See!,” are silent objects of voyeurism and ownership; they are sung about, and perhaps sung to, but they do not sing.71

Misogyny on the minstrel show stage is comprehensively discussed in Mahar, Behind the Burnt Cork Mask, chap. 6; see also Lott, Love and Theft, 25–28, 177.

Although at present there is scant supporting data, it seems likely that opera parody songs spurred the trend of blackface female impersonators that culminated in the postwar period with the spectacular careers of performers such as Francis Leon. During the antebellum period, George Christy was one of the most well known female impersonators; he particularly is remembered for his performances of the “wench” song “Lucy Long.” An earlier and lesser known female impersonator, Maximilian Zorer, had clearer connections to opera. Zorer emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1848 with a choral group called the Moravian Singers. Within two years of arriving, he began to work with minstrel troupes, including Christy's Minstrels and the New Orleans Serenaders. He was known for his falsetto, which he used to imitate famous operatic sopranos. Zorer authored “Hither We Come” (New York: Vanderbeek, 1850), a parody song based on the popular “Pirate's Chorus” from Balfe's opera The Enchantress. See Toll, Blacking Up, 139-145; Annemarie Bean, “Transgressing the Gender Divide: The Female Impersonator in Nineteenth-Century Blackface Minstrelsy,” in Inside the Minstrel Mask: Readings in Nineteenth-Century Blackface Minstrelsy, ed. Annemarie Bean, James V. Hatch, and Brooks McNamara, 247 (Hanover, N.H.: Wesleyan University Press, 1996); Lawrence, Strong on Music: Resonances, 539–40; Lawrence, Strong on Music: Reverberations, 125; New York Herald, 9 September 1850.

In 1849, a reviewer of a performance by the New Orleans Serenaders wrote:

In looking at [publications of] the so-called Negro music, we have often thought of the peculiar taste of this country in patronizing Negro minstrelsy to such an extent, while in reality the music is of the same character as all the other ballads. We were forcibly reminded of this while we attended a performance of the New Orleans Serenaders at the Philadelphia Melodeon. The program announced to us Negro melodies of various characters; but to our astonishment, we were regaled with the all-popular ballad of “Jeannette and Jeannot,” Vi ravviso from La sonnambula, and several other gems of operas. The audience consisted of the very elite of Philadelphia society and could not have numbered less than a thousand. The different pieces were performed with a precision and taste which would not have shamed performers of different color, and very naturally suggested the question, why, since there was so much talent in that little band, the performers preferred not to exhibit their own natural color? One of the artists, for they really deserve that name, replied: “We have tried several times to give concerts as white folks, and the consequence was empty benches and light pockets.”73

This review of the New Orleans Serenaders, published in the Musical Times, 13 October 1849, is quoted in Lawrence, Strong on Music: Resonances, 590–91. Lawrence suggests that this article was written by Saroni, editor of the Musical Times.

Minstrelsy was not monolithic: it attracted both the middle class and the working class, and its repertory included sophisticated burlesques of opera as well as comic songs. As the opera parody songs suggest, the work of commercialized minstrelsy generally lay in reinterpreting existing works rather than in creating new ones, and the flattened yet flexible blackface context—sinister, tenacious, and yet innocuous in its familiarity—could support multiple layers of burlesque. The operatic layer in particular helped to facilitate the mainstreaming of minstrelsy. Its simultaneous engagement with antebellum popular culture and representation of a foreign, sophisticated genre made possible its remarkable success in attracting new and larger audiences to the minstrel show.

I am grateful to Susan Aungst and Donna Miller of the Bishop Library at Lebanon Valley College for their research assistance and to Katherine K. Preston and Jeffrey Snyder for their suggestions on earlier drafts of this essay.