By the 1910s, large segments of urban America had fully embraced modernism. Primarily because of Alfred Stieglitz and his large circle of artist, writer, and critic followers, modernism had been part of the New York art world since the beginning of the twentieth century, and American artistic modernism had assumed its own unique shape.1

We use the term modernism here to refer to movements in the various arts in the early twentieth century characterized principally by a break or an attempt to break away from nineteenth-century conventions. As with any cultural movement, defining modernism is not easy, but for a general summary of what it means, see William R. Everdell's “What Modernism Is and What It Probably Isn't,” and “Discontinuous Epilogues,” in The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 1–13 and 346–60. Stressing the difficulty of applying any umbrella definition of modernism, Everdell discusses five concepts that are “among its ingredients”: “self-reference and recursion, radical subjectivity, multiple perspectives, statistics and stochastics, and discontinuity” (346–60).

Recent studies have discussed other types of modernisms that will not be treated here, such as the Harlem Renaissance. See Houston A. Baker Jr., Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987) and Jayna Jennifer Brown's excellent “Babylon Girls: African American Women Performers and the Making of the Modern” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 2001). It should be noted that these modernist developments occurred mainly in the 1920s, later than the period we are investigating.

In an interview with R. Allen Lott, Louise Varèse stated that Varèse was “amazed” at the absence of musical modernism when he arrived. In 1919 he commented about the organizations that sponsored concerts: “Too many musical organizations are Bourbons who learn nothing and forget nothing. They are mausoleums—mortuaries for musical reminiscences. “Edgard Varèse is a True Modernist,” New York Morning Telegraph, 20 April 1919, sec. 4, 4. Both references quoted in R. Allen Lott, “‘New Music for New Ears’: The International Composers' Guild,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 36/2 (Summer 1983): 267.

As late as 1918, Frederick Martens used as an example of a modernist piece César Franck's Sonata for Violin and Piano. See Frederick H. Martens, Leo Ornstein, The Man—His Ideas—His Work (New York: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1918), 16. With few exceptions, and Ornstein's will be among them, most concerts in the early 1910s could just as well have been given in the 1880s.

Ultramodern was the term used to distinguish a group of radical composers, including Varèse, Charles Ives, Carl Ruggles, Henry Cowell, Dane Rudhyar, and Ruth Crawford from forward-looking but less radical ones, such as George Gershwin, Roger Sessions, and Virgil Thomson. Some composers, such as Aaron Copland, seemed to straddle the two camps. The term became common only around 1920. Before then, ultramodern artists were referred to as futurists, cubists, anarchists, modernists—terms used with little specificity or definition.

In this article we wish to challenge two fundamental assumptions about American musical modernism, embodied in the first paragraph: that its establishment on American soil lagged behind that of the other arts, and that it was relatively isolated from the other arts. We will argue that 1) a burgeoning modernist musical culture was in place by 1915; 2) it extended far beyond individual efforts of a few isolated composers; 3) it was led by many of the same persons who would play important roles in the 1920s, by Claire Reis and Paul Rosenfeld, for instance, and in particular by Leo Ornstein, who was the fulcrum upon which much of this activity depended; and 4) American musical modernism from the beginning had strong ties to the other arts.

Many scholars agree that American musical modernism began with Charles Ives and Leo Ornstein, both of whom amassed a body of dense, complex, challenging works well before 1920. Beyond that, however, the story becomes more complicated, as the distance between creation and acceptance was great, at least for Ives, and additionally there were other composers active, namely Henry Cowell, Carl Ruggles, and Edgard Varèse. Charles Ives's story is well known, that he balanced his compositional life with an insurance career, and made only occasional, sporadic, and mostly futile attempts to get his music before the public before 1921, when he began an ultimately successful campaign to interest musicians in his work. Like Ives, neither Cowell nor Ruggles made a significant impact on American music before 1922. Cowell became known only after his return from Europe in 1924 and Ruggles struggled to find his compositional voice, which the public did not hear until the first concert of the International Composers' Guild in 1922.

Varèse's failures in the 1910s are central to the current reigning narrative of American modernism. Varèse attempted to stir up interest in musical modernism from the moment he arrived in the United States in December 1915. His most concerted effort to convert the American musical public to modernism occurred in 1919 when he founded the New Symphony Orchestra, with the specific purpose of introducing new music to American audiences. At that time he considered himself primarily a conductor. The endeavor was well funded by a group of patrons led by Gertrude Vanderbilt; the first concert featured music by Debussy, Alfredo Casella, Bartók, and Gabriel Dupont. According to Varèse's biographer Fernand Ouellette, critical reception was so negative that the orchestra refused to continue performing unless Varèse programmed more traditional works. Varèse held fast, and the orchestra disbanded.6

Fernand Ouellette, Edgard Varèse, trans. Derek Coltman (New York: Orion Press, 1968), 53.

James Gibbons Huneker, “Music,” New York Times, 12 April 1919, 12. This concert was not the first time Varèse's conducting met with critical disapproval. For Varèse's conducting debut, in a heavily promoted performance of Berlioz's Requiem at the Hippodrome Theater in New York on 1 April, 1917, much of the same criticism resulted.

Concurrently Varèse also envisioned a “League of Nations of Art.” Whether this was more than an effort designed to capitalize on the intense discussion surrounding the formation of a League of Nations that was omnipresent in newspapers of the time, or whether it was a serious proposal is not known. Other than a visionary letter Varèse wrote to the New York Times, nothing came of it.8

Varèse, “A League of Art, A Free Interchange to Make the Nations Acquainted,” New York Times, 23 March 1919, 1:7, quoted in Olivia Mattis, “Edgard Varèse and the Visual Arts” (Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1992), 120.

In a 1934 interview, Varèse offered his own explanation for what he perceived as the failure of the American musical world to embrace modernism in the 1910s: “In the visual and plastic arts … there was change—witness Cezanne and Picasso—but in the art of the ear there were obstacles of the virtuosos and the conductors, men like Toscanini who used music simply as a means of self-glorification. It was in their power to decide what to play and how to play it—always with an eye to showing themselves off to the best light, regardless of the intention of the music.”9

In Michael Sperline, “Varèse and Contemporary Music,” Trend 2/3 (May–June 1934): 125, quoted in Felix Meyer, “‘The Exhilarating Atmosphere of Struggle’: Varèse as a Communicator of Modern Music in the 1920s,” in Edgard Varèse: Composer, Sound Sculptor, Visionary, ed. Felix Meyer and Heidy Zimmermann (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2006), 82.

In Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), Carol J. Oja calls the 1910s the “mysterious Paleolithic period of American modernist music,” where “[o]ccasional glints of activity were overshadowed by a new single-minded focus on historical European repertories. Concert-goers were far more likely to hear Schubert than Stravinsky, and they had little chance of encountering music by a forward-looking composer born in America” (11). See also Michael Broyles, Mavericks and Other Traditions in American Music (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 98–101, for a discussion of the conservative nature of the American musical world in the 1910s.

One composer, however, was active, successful, and well known in the 1910s: Leo Ornstein. Ornstein had trained for a career as a concert pianist, when suddenly in 1913 he discovered his own modernist compositional idiom. He first performed some of his new works in London in 1914 and created a sensation. Returning to the United States, he gave a series of four recitals in New York in early 1915 (four years before Varèse's efforts), which consisted of all modern music, virtually unknown to American audiences. The latest works of Schoenberg, Scriabin, Ravel, Grainger, and Cyril Scott were first heard by American audiences at these concerts.

Ornstein toured widely for the next six years. He constantly performed before packed halls, of often more than 2,000 people, in many places drawing the “largest audience of the season.”11

“Leo Ornstein at Detroit,” Musical Courier 25/21 (22 November 1917): 47; “Ornstein's Los Angeles Recital,” Musical Courier 25/21 (22 November 1917): 52.

“Huneker's Description of Ornstein Recital,” Musical Courier 78/6 (6 February 1919): 43.

Treble Clef, “Age of Miracles Still Here for Atlanta Actually Crowds to Ornstein Recital,” Atlanta Georgian, 3 November 1916, 7.

By 1918, Ornstein was possibly the most notorious musician in America. In 1916, Waldo Frank prophesized that of Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Ornstein, “Ornstein, the youngest of these, gives promise to be the greatest.” That same year Charles Buchanan claimed that “potentially, he [Ornstein] is the most significant figure in today's music.” Two years later the “potentially” was gone: Ornstein was “the most salient musical phenomenon of our time.” The year before, Herbert F. Peyser observed that “the world has indeed moved between the epoch of Beethoven and of Leo Ornstein.” Grenville Vernon claimed that “Schoenberg, Strawinsky and Ornstein are truly the prophets of the New Evangel.” James Huneker found Ornstein the only “true-blue, genuine, futurist” composer alive,” and in London, an anonymous critic for the London Observer, dubbed Ornstein “the sum of Schoenberg and Scriabine squared.”14

Waldo Frank, typescript for an article “Leo Ornstein and the Emancipated Music,” to appear in The Onlooker (1915), in Ornstein Collection, Yale Music Library, quoted in Vivian Perlis, “The Futurist Music of Leo Ornstein,” Notes 31/4 (June 1975): 741; Charles L. Buchanan, “Futurist Music,” Independent, 31 July 1916, 160; “Ornstein and Modern Music,” The Musical Quarterly 4/2 (April 1918): 176; Herbert F. Peyser, “Inverted Philistinism of Futurism's Defenders,” Musical America 24/24, (16 October 1915): 15; James Grenville, “The Musical Futurist and His Sophisticated Discords,” New York Tribune, 5 March 1916, 7; James Huneker, Columbus (Ohio)Sunday Dispatch, 7 January 1917, magazine section, 3; Observer (London), quoted in Martens, Leo Ornstein, 24–25.

Ornstein succeeded in part because he was his own performer. He did not depend on others to get his music before the public, but only had to satisfy his manager, Martin H. Hanson. Although there was constant tension between the two—Hanson wanted Ornstein to program more traditional works—as long as Ornstein drew the crowds, his manager was perfectly willing to allow him his musical preferences.

In spite of Ornstein's success, historians consider him a momentary and isolated phenomenon who created a stir wherever he went but left no real legacy and had little impact on later modernist developments. Ornstein's role is considered at best prophetic, at worst tangential. Carol Oja, who provides what is still the most detailed and vivid portrait of Leo Ornstein in the scholarly literature as well as the most important study of musical modernism in the 1920s, finds that beyond limited connections with several emerging modernist composers in the late teens, Ornstein had little impact on the musical events of the 1920s. David Joel Metzer considers Ornstein something of a father figure, whose advocacy of modern music helped prepare the way for its later acceptance, but who had little influence beyond that. Other scholars have come to similar conclusions. Broyles draws on the complexity theory concept of fitness landscapes, as used in evolutionary biology, where populations move along a smooth continuum but sometimes leap to different areas, either to succeed or die out. He portrays Ornstein as an isolated phenomenon who leapt to another metaphorical mountain but found himself alone and isolated there.15

Oja, Making Music Modern, 24; David Joel Metzer, “The Ascendancy of Musical Modernism in New York City, 1915–1929” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1993), 129–30; Broyles, Mavericks, 91.

The portrayal of Ives and Ornstein as lone voices that the public either did not want to hear (Ives) or that flocked to his efforts (Ornstein) as some sort of circus act, has much resonance in today's musical scholarship.16

This is not to say that Ives was isolated in the sense that he was unaware of new developments in Europe—on the contrary he was well informed of them—but that the public was unaware of him.

Efforts toward the establishment of American modernism were more widespread than generally believed, and those attempting to implant modernism were not just autodidactic teenagers, angry immigrants, isolated insurance agents, or quirky pianists—that is, Cowell, Varèse, Ives, and Ornstein. Further the musical world was not isolated from modernistic activity in the other arts. Musical modernism was not a “thing-in-itself,” but was closely tied to events in literature and the visual arts. Ornstein, himself, enjoyed close connections with important figures in art and literature, many of whom would later play critical roles in the more well known events of the 1920s. While Charles Ives remained almost completely unknown, Leo Ornstein, rather than being a lone voice in the wilderness, was the center and focal point of a complex network of advocates for modernism, which embraced the most important modernist circles of the time. The networks around him both advanced his career and prepared those involved for modernism's later success.17

An alternative title for this article might be “Circles and Triangles and Networks.”

In an interview, Ornstein recalled, “At one time I was very interested in experimentation, and I got a coterie around me of young people.”18

Leo Ornstein, interview with the authors, Green Bay, Wisconsin, 26 June 1998.

Most of those who gathered around Ornstein were not professional musicians: they were either interested in supporting new developments in music because of Ornstein or they were already active in the other arts. In the former category are Claire Reis (née Raphael), A. Walter Kramer, and Paul Rosenfeld, all close to Ornstein, and all, in response to Ornstein's work, planning for new organizations supporting modern music as early as 1914. In the latter circle were John Marin, William Zorach, Waldo Frank, and Rosenfeld again. More than an isolated figure, Ornstein formed a musical bridge to the other arts, later helping to move music out of its cultural isolation.

Ornstein was at the center of at least three groups or circles in the 1910s, the first in Europe and the others in the United States. He had been taken to Europe in 1913 by Bertha Feiring Tapper, his teacher, mentor, and surrogate mother.19

Bertha Feiring Tapper, Norwegian pianist, taught at the Institute of Musical Arts, which in 1926 became the Juilliard School of Music. Ornstein studied with her there until 1910, when he graduated and she left to teach privately.

“First Futurist Concert in City Has Great Value,” Montreal Daily Star, 14 February 1916, 2.

Leo Ornstein, “How My Music Should Be Played,” part 2, Musical Observer 13/1 (January 1916): 10.

It should be noted that Ornstein later dedicated Impressions de la Tamise (Impressions of the Thames) to Leschetizky.

After Vienna he traveled to Norway, homeland of Mrs. Tapper, and made his debut in Christiania as a concert pianist with a group of Chopin pieces and the Liszt E-flat major concerto. For the first time, he also played some of his own newer compositions, likely the Two Impressions of Notre Dame and perhaps even Danse Sauvage. The confusion and incredulity of the Christiana critics foreshadowed the reactions he would face once back in America: “[I]t was amazing that Mr. Ornstein should have decided to play a little joke on the public and transfer it from the concert hall to the dental parlor.” They concluded that he was “a young man temporarily insane.”23

Martens, Leo Ornstein,20.

During the trip, Ornstein went to Berlin and met Busoni, and visited Denmark briefly. He then went to Paris, where he met Harold Bauer, the internationally famous piano virtuoso. Although Bauer expressed confusion about Ornstein's original compositions, he acknowledged the younger pianist “as a composer with a new and important message to deliver, one which deserved hearing.” Frederick Martens, who wrote the first biography of Ornstein in 1918, characterized this encounter as marking “an epoch in Ornstein's career.”24

Ibid. Though trained initially as a violinist, Bauer was an English-born musician, who after studying with Paderewski devoted himself to the piano and enjoyed a worldwide reputation for his technical abilities and extraordinary interpretive gifts. Starting in 1892 he based himself in Paris. As a result of his international fame, Bauer knew Europe's most important musicians. Charles Hopkins, “Harold Bauer,” Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (accessed 12 July 2005), http://www.grovemusic.com.

Bauer, whose path would cross with Ornstein's over the years, was indeed a seminal force in getting the visitor known in Europe; he introduced Ornstein to Walter Morse Rummel, who provided the young pianist-composer with an entrée into Parisian musical society. Rummel (1887–1953) was also a pianist-composer, and a close friend and champion of Claude Debussy, premiering many of Debussy's piano works. Upon returning to the United States, Ornstein became one of Debussy's most ardent proponents and programmed his works on dozens of concerts.25

See Charles Timbrell, “Walter Morse Rummel,” Grove Music Online, ed. L Macy (accessed 12 July 2005), http://www.grovemusic.com.

In addition, Rummel was a friend of the American dancer Isadora Duncan (1878–1927), who had established a thriving dance school just six miles outside of Paris. It is possible that Rummel (re)introduced Ornstein and Duncan, who three years earlier had given concerts within a couple of days of each other in New York.26

Ibid.

Given that Ornstein's father, Abraham, was an extremely conservative Old World Orthodox Jewish cantor, this scene, if it occurred, must have sent shivers down Abraham's spine.

Rummel provided Ornstein with a letter of introduction to the poet, music critic, translator, and Ravel confidant Michel Dimitri Calvocoressi (1877–1944). Calvocoressi was a member of Les Apaches, a group of avant-garde artists, poets, and musicians in Paris who regularly met to discuss all matters pertaining to the arts.28

Members of Les Apaches included “the Catalan pianist Ricardo Vines … writers Tristan Klingsor and Léon-Paul Fargue, the painter Paul Sordes, the conductor Désiré-Emile Inghelbrecht, and composers André Caplet, Maurice Delage, Manuel de Falla, Florent Schmitt, and Déodat de Severac. … It was in this circle of artistic acceptance that [Ravel] tried out some of his first masterworks.” Regarding Ravel's involvement with this group, see “Shéhérazade, Three Poems of Tristan Klingsor for Voice and Orchestra,” New York Philharmonic, http://newyorkphilharmonic.org/programNotes/0304_Ravel_Sheherazade3Poems.pdf.

Martens included Ornstein's first-person account of his time in Paris. It is among Ornstein's very few personal statements from this period, and so is worth reproducing in its entirety:

I went with my letter to Calvocoressi's apartment; he had a suite of rooms some three flights up in the Rue de Caroussel, and a blind woman—his mother—opened the door in answer to my ring. I was ushered into his studio, a pleasant room, its walls covered with books and pictures, with a grand piano littered with manuscripts, and a tall dark man, with a slight stoop, rose from his desk to receive me. He had a gentle voice and sympathetic manner and, after reading my letter, asked me in Russian—and it was a great pleasure to hear the accents of my mother-tongue again—whether I composed or merely played modern music.29

Calvocoressi was an extremely talented linguist and translator. In addition to English and French, he also read and spoke Greek and Russian.

It may or may not be telling that in this account Ornstein refers to Danse Sauvage as Wild Men's Dance, the more likely title he would have given the piece had it been composed in New York prior to his visit to Paris. He may have also employed the English title commonly used by then when talking to Martens.

It is likely he drew from his acquaintances among Les Apaches.

This remark may indicate that Ornstein was more interested in composing than performing.

Though I was too busy with my lessons and work to meet many people, I made the acquaintance of the Roumanian Princess de Brancovan and the gifted music-lover and musician, Mme. Landsberg—she sang very well—wife of the Brazilian banker of the same name, to each of whom I ascribed one of my Preludes, and for both of whom I played; as well as the American-born Princess de Polignac, who has taken such an interest in Stravinsky's music, and at whose musicales I also appeared.33

Although Ornstein does not specify, it is likely he is referring to two works from a set of three preludes that he wrote while in Europe and played at public appearances in London and Paris in the spring of 1914. They were eventually published by Schott. The three works—“Andantino,” “Moderato,” and “Allegro”—are written in a dissonant idiom similar to Impressions of Notre Dame and other of his modernist style works.

During February and March of 1914, Calvocoressi gave a series of lecture-recitals, two of them devoted to the Géographie Musicale de l'Europe, with musical illustrations drawn entirely from works of modernist composers. In the first lecture were represented Richard Strauss songs, piano pieces by Bela [sic] Bartók, Zoltan Kodaly, Vilmos-Geza Zagon, Serge Liapounov, and Cyril Scott's “Jungle Book” pieces, which last I played. At the second lecture-recital I played my own Impressions de la Tamise and Danse Sauvage and piano pieces (Op. 11 and 19), by Arnold Schönberg. Stravinsky's interesting Melodies Japonaises were also sung at this recital.34

See Martens, Leo Ornstein,20–22. Bartók's groundbreaking Allegro Barbaro (1911) may have been one of these piano pieces. Its newly percussive treatment of the piano made it a noteworthy example of that which was most modern. In 1927, Ornstein labeled the first movement of his Piano Quintette, “Allegro barbaro.” Selections from Scott's “Jungle Book” regularly appeared on Ornstein's recitals once he was back in the US.

Ibid., 22.

In the late 1890s, Quilter, like many English-speaking music students, attended the Frankfurt Conservatory where he pursued piano and composition. There he fell in with four other students who together became known as the Frankfurt Five or Frankfurt Group: Roger Quilter, Balfour Gardiner, Percy Grainger, Norman O'Neill, and Cyril Scott.36

As Valerie Langfield states in Roger Quilter: His Life and Music (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2002), in 1907 Percy Grainger traveled to Norway and met Edvard Grieg, a composer he idolized. While there he “played and sang some of Quilter's songs … which pleased Grieg greatly. [Upon] Grainger's suggestion, Quilter promised to send Grieg some of his music” (27). Quilter's connection to Grieg, and Ornstein's own through Mrs. Tapper gave the two men an important musical link.

The Frankfurt Group shared little by way of a solid aesthetic agenda other than to maintain their individuality. As Valerie Langfield explains: “What common factor there was—and Grainger was vocal in talking and writing about this—was harmonic: he wrote of the importance to them of ‘the chord’ and their compositions tended to be ‘vertical’ rather than ‘horizontal’, and so the more telling on the rare occasions when contrapuntal techniques were used.”37

Ibid., 16.

Stephen Lloyd, “Grainger and the ‘Frankfurt Group,”’ in Percy Aldridge Grainger Symposium, ed. Frank Calloway et al. (Nedlands: University of Western Australia, 1982), 112–13. The harmony to which Lloyd refers is basically quartal harmony. Scriabin's “mystic” or Prometheus chord consisted of a series of augmented, diminished, and perfect fourths: C–F-sharp–B-flat–A–D.

Much the same can be said of Ornstein's most dissonant, futurist music, which is noteworthy for its coloristic chords built on fourths, or dense, highly chromatic chords that span a seventh, and for its avoidance of extended counterpoint. When counterpoint is hinted at—usually some kind of distant, short-lived echo-like passage—it assumes special significance. Ornstein's tendencies towards verticality and away from polyphony, his preference for irregular barring, his avoidance of key signatures, and focus on rhythmic energy would all have been reinforced rather than challenged by his association with the Frankfurt Five.39

Ornstein's Lyric Fancies and Miniatures, pieces written prior to his second trip to Europe, are melodically driven and not primarily focused on vertical sonorities. See Lloyd, “Grainger and the ‘Frankfurt Group,”’ 115–16, for a discussion of these qualities in the music of the Frankfurt Group in general and Cyril Scott in particular.

Quilter performed a role for Ornstein in London similar to that of Calvocoressi in Paris, introducing him to a wide circle of interesting people in positions to help.40

Langfield, Roger Quilter, 20.

Martens, Leo Ornstein,23. The identity of the precise Arthur Shattuck referred to in this passage has not been determined.

Ibid. Given Quilter's long list of friends and associates it is not possible to definitively identify the painter to whom Martens alludes. Based, however, upon Langfield's description of Major Benton Fletcher, “a noted artist and author” who was also “a popular guest at dinner parties, interesting, witty, [and] good-looking,” he is a likely candidate. See Langfield, Roger Quilter,28.

The Grave was written by the British poet and Scottish minister Robert Blair (1699–1746), one of the more prominent members of the graveyard school of English poetry. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is a poem by Blake.

Ibid. The immediate transferral of idea or image to sound would be the composer's analogous experience. Ornstein appears to have worked very much this way.

Example 1. Leo Ornstein, Sonata for violin and piano, op. 31, beginning.

Through the influence of Quilter, Ornstein had the opportunity to give two recitals of modern music at Steinway Hall in London in March and April of 1914.45

No accounts exist of how this came about. A letter from Ornstein to Quilter dated 14 February 1914 clearly indicates that Quilter was responsible for arranging the concert (personal correspondence with Valerie Langfield, October 1999). We want to thank Valerie Langfield for sharing information on these letters.

Critics were alternately amused, offended, and confused. Richard Capell, of the Daily Mail, wrote of the “Wild Outbreak at Steinway Hall,” and described “a pale and frenzied youth, dressed in velvet, crouched over the instrument in an attitude all his own, and for all the apparent frailty of his form, dealt it the most ferocious punishment.” The Times reviewer referred to the “violent—one might almost say brutal—assaults as Mr. Ornstein made on the piano,” but did concede that Danse Sauvage was “something, moreover that brought vividly to the mind a picture of primordial beings in all the savage abandonment of the wildest of corybantic revels.”46

R. C. [Richard Capell], “Futurist Music: Wild Outbreak at Steinway Hall: Pale and Frenzied Youth,” Daily Mail, 28 March 1914, 1a; “A ‘Futurist’ at the Piano,” Times (London), 28 March 1914, 6; U. A., “Steinway Hall,” Daily Telegraph (London), 8 April 1914, 8.

The second recital, on 7 April, consisted of only Ornstein's music. Both the critics and the crowd were ready for him. According to Capell, “The gallery hissed, booed, groaned, and guffawed with derision, and someone felt impelled to supply the missing melodic element in M. Ornstein's music with more tuneful whistling. In fact no London concert-giver in recent years has had such harsh treatment.”47

R. C. [Richard Capell], “Futurist Music Hissed: Hostile & Derisive Audience,” Daily Mail (London), 8 April 1914, 3.

Carl Van Vechten, Music and Bad Manners (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1916), 238.

Soon after his second London recital, Ornstein sailed back to the United States. During the summer of 1914, Ornstein corresponded with those who had made his stay there so enjoyable; the letters reveal deepening friendships and a desire to return to Europe. A note from Ornstein to Quilter sent in May of that year reflects a more informal relationship than had existed between them in February. Ornstein addresses “Dear Roger” from Blue Hill, Maine, where he is “very hard at work on my Quartette,” signs “With love, Yours, Leo” and asks Quilter to “Please give my kindest/regards to your mother.”49

Note from Ornstein to Quilter, 18 May 1914. We are grateful to Valerie Langfield for calling our attention to the Quilter-Ornstein correspondence and making it available to us.

Another letter from Blue Hill, dated just eleven days later, tells something of Ornstein's summer work habits, his musical preferences, and his plans for a return trip to Europe in the fall. It is no wonder he wished to return. He had been asked to compose an original symphonic work by the conductor Sir Henry J. Wood in London; he had endeared himself to some of the most powerful musicians both there and in Paris, and he had gained entrée to important circles of patronage. A forty-concert trip to Norway was set for the fall of 1914, probably through the efforts of Bertha Feiring Tapper, and further concerts in England, France, and elsewhere were either planned or being discussed.

The outbreak of World War I in July of 1914, however, dashed any hope of going back to Europe. We can only speculate what tack Ornstein's career would have taken had he returned, fresh after his attention-grabbing London and Paris debuts, for an extended concert tour, and perhaps to reside. In Les Apaches and the Frankfurt Group, Ornstein had found a large number of friends who were equally committed to the modernist idiom. He had also established a circle of supporters among patronesses and the society set who had taken him in, and he could anticipate more opportunities to build upon his newly won fame.

The eruption of war and the resulting cancellation of his plans meant that Ornstein was left in the United States with no immediate likelihood of getting back to Europe, and no recital or concert engagements for the upcoming season. It quickly became clear that to have any prospects at all, Ornstein would have to give up the idea of a European career and devote his energies to building one elsewhere, primarily in the United States.

In very real ways, the war also cost Ornstein proximity to his first circle of friends, which he had only just found. Although a few letters written by his English acquaintances suggest attempts on their part to maintain contact with Ornstein, after the spring of 1915 he assessed the situation, cut his losses, and focused his energies on what was more likely to produce results. His career became exclusively American; he never again went to Europe as a performing artist. With no ready-made group to embrace him on this side of the Atlantic, Ornstein had to create one of his own. He did, and it included Claire Reis, Paul Rosenfeld, A. Walter Kramer, and Waldo Frank. The situation became even more urgent when in September 1915 Bertha Feiring Tapper unexpectedly died. Her efforts to get her favorite pupil before the public eye, however, were not forgotten.

Prior to Tapper's death, Claire Reis, a former student in Mrs. Tapper's studio at the Institute of Musical Arts, had already begun her own campaign to champion her classmate Leo Ornstein: first because, like her teacher, she believed in his music and his pianistic talents, and second because she saw him as a potential lightning rod for the modernist cause to which she was committed and with which she would later become identified.50

The precise years of Raphael Reis's work with Tapper are uncertain. In an article that appeared in Eolian Review 2/2 (March 1923), Reis states that she worked with Tapper between 1908 and 1910 (28). These years would coincide with Ornstein's last two years of study at the Institute and concur with Reis's own remarks in her book Composers, Conductors, and Critics, that she “spent the next two years at the Institute of Musical Art” (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), 21. But as Carol Oja has observed, “[A]mong Reis's papers is a photograph of Tapper, stating on the back that Reis studied with her from 1906 to 1913.” See Oja, “Women Patrons and Crusaders for Modern Music: New York in the 1920s,” in Cultivating Music in America: Women Patrons and Activists since 1860, ed. Ralph P. Locke and Cyrilla Barr (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 258 n. 42. Reis may very well have studied privately with Tapper after 1910, when Tapper left the Institute. The only question is when she began study. If it was as early as 1906, she would have known Leo from the time of his arrival in the country, making her one of his very earliest acquaintances.

Claire R. Reis, Composers, Conductors, and Critics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), 35.

In the fall of 1914, Reis invited her close friend Waldo Frank (1889–1967) and a new acquaintance, Paul Rosenfeld (1890–1946), to accompany her to an informal recital given by Ornstein at Tapper's home at 362 Riverside Drive.52

That Waldo Frank was an accomplished amateur cellist would have been known to Ornstein over their many years of friendship. What is not known is whether any of Ornstein's many cello pieces were written with Frank in mind. Certainly Ornstein developed into a sensitive writer for the instrument. Correspondence with Leo's son Severo Ornstein clarifies that during Waldo's visits to the family compound in New Hampshire in the 1930s and 1940s, Waldo Frank did not play cello either for or with Ornstein: “I would have known and been stunned if he had. Dad never played when the family had visitors—unless he went up to his studio to practice.” Correspondence with the authors, 13 September 2005.

Reis, Composers, Conductors, and Critics, 21.

The long room with a façade of windows giving on the Hudson was astir like a convention of birds with the elegant gentlemen and ladies perched on their camp stools, and facing their twitter stood the silent black Steinway grand. Now a youth, not much over five foot, in his late teens, sidled past the rows of seats; and as he came close to the piano his head seemed to sink into his shoulders. He crouched rather than sat on the piano stool and placed his large, beautiful hands on the keyboard. The noise lessened. His long head rose, and his body straightened; he seemed suddenly a foot taller. With a single finger he struck a single note; and as if it were a signal, the silence became perfect.

He played a Debussy Prelude, making the music an overtone of his own strong seclusion. The music died, the applause burst, and the pianist took it as an almost unbearable invasion of the music. As if to stop it, he touched the keys again and played a piece by Ravel, whose wavery arabesques he hardened into springs of steel. When the applause came now, he faced it, turning his head barely, his body not at all, and continued at once with a composition by Albéniz.

Mrs. Tapper stood up and announced to her guests that Leo would now play some of his own music. Leo responded with a voluminous, cacophonous broadside of chords that seemed about to blow the instrument in the air and break the windows. Chaos spoke. Ladies laughed hysterically. The music growled like a beast, clanged like metal on metal, smoldered before it burst again, and suddenly subsided. Leo drooped over the keys, like a spent male after coitus, his head down as if he were praying. The audience shot to their feet, unconsciously determined perhaps that the ordeal be over and they need hear no more horrors. Claire and I shouldered through the throng to the piano which might have been a guillotine. I noted that there was blood on the keys. I looked close at the small ghetto-bred body … the strong masculine head, and threw my arms about Leo Ornstein, loving him at once because I loved the music.54

See Memoirs of Waldo Frank, ed. Alan Trachtenberg, introduction by Lewis Mumford (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1973), 65. In the fall of 1914, Ornstein would have been twenty years old. The Institute provided Ornstein with important contacts, not only with well-placed faculty, but with peers who would, like Reis, assume pivotal positions in New York's modern music scene in the twenties. Reis's relationship to the International Composers' Guild likely explains Ornstein later being named a member of that society's advisory board.

Ibid., xxiii. Ten years later Aaron Copland would return from three years of study in France with a similar goal in mind.

Rosenfeld spent most of the months of July and August 1915 and 1916 in Blue Hill.

I've been discussing with Leo his plans for the winter and we've decided to consult you. The project under consideration is a series of six Sunday night recitals—at $10 the series, to be given during the months of December [1915], January, and February [1916]. Leo thinks he can get Steinway Hall for very little. I suggested giving a comprehensive course in modern piano music, semi-private, the audience limited to sixty or seventy.57

It is likely that this comprehensive course morphed into a series of articles titled “How My Music Should be Played and Sung: A Series of Papers Devoted to the Character and Idiom of My Latest Works, Describing Essential Requirements for Their Adequate Understanding and Providing Suggestions for Mastery of Their Technical Difficulties.” See The Musical Observer, January 1916, 9–11, for the first of these articles. It contains an explanation regarding Ornstein's stylistic epiphany, which he refers to as “My Musical Awakening.”

Of course it's rather late in the year to talk of forming a club of that sort for this winter season, but the Leo-audience would be a step in the same direction, which gives us something to think about with you for next year—don't you agree? You remember speaking of a similar matter, don't you, during one of our talks last Spring?58

Letter from Paul Rosenfeld to Claire Raphael, 6 August 1915, Claire Reis Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Research Division. A typed transcription of this letter in the collection has incorrectly transcribed the date as 16 August 1915. One wonders whether Ornstein really envisioned Steinway Hall for this event intended to attract an audience of sixty or seventy. The main auditorium of Steinway Hall, then on Fourteenth Street, had 2,000 seats. (Steinway Hall moved to its current location at 109 West Fifty-seventh Street in 1922.) It had been the home of the New York Philharmonic until Carnegie Hall was built in 1891. Perhaps Ornstein planned to use one of the smaller rooms where pianists tried out instruments. It is possible that he assumed his infamous concerts at Steinway Hall in London would provide some kind of entry into the related facility in New York.

In addition to being a violinist, chamber musician, and composer, Kramer was a writer, and would eventually become editor of Musical America. It is no coincidence that many extended pieces on Ornstein were published in that widely circulating music magazine.

In reference to the latter, Kramer explains, “Let us understand that Mr. Ornstein's purpose is not to discover harmonies that are new, or that are altered in the manner of the modern Frenchmen. The opening group of notes in his “First Impression of Notre-Dame” … does not claim to be an altered 13th or anything of the kind.” A few bars of the introductory measure of this work and of his third prelude from “Three Preludes,” op. 20 adorn the top of the article for readers to consult.60

Just a month after Kramer's article appeared, Thomas Vincent Cator responded with a letter to Musical America 21/92 (January 1915): 24–25. In it he proposed a reharmonization of Ornstein's Impressions “according to the best principles … with chords that are logically related to one another.” Needless to say, Cator's suggestions eliminated the very qualities of Ornstein's music that made it distinctive. Kramer's allusions to modern French composers is curious given Ornstein's regular programming of Debussy and his avowed respect for Ravel. Perhaps Kramer heard a resemblance between Ornstein's music and theirs and felt compelled to claim no influence of the French masters upon his young friend.

A. Walter Kramer, “Has Leo Ornstein discovered a new Musical Style?” Musical America 21/6 (12 December 1914): 5–6.

Whether Kramer had a hand in the actual arrangements for the upcoming so-called Bandbox Concerts,62

The four Bandbox Concerts that Ornstein gave in January through March 1915, at the Bandbox Theatre in New York, introduced many modernist piano works to American audiences.

Beyond his cooperative efforts with Kramer and Reis, a letter of 7 December 1914 shows Ornstein agreeing to meet with Waldo Frank, at that time an aspiring, unpublished author.63

Letter from Leo Ornstein to Waldo Frank, 7 December 1914. Ornstein invites Frank to “come up on Sunday at five in the afternoon to 85 West 87th Street room 14. (Mr. Jewett's Studio).” Clearly the men were in the earliest stages of their friendship. The letter is addressed to “My dear Mr. Frank” and signed “With kind regards, Leo Ornstein.” Waldo Frank Papers, Annenberg Rare Book and Manuscript Library Collection, University of Pennsylvania. Letters between Waldo Frank and both Leo and Pauline Ornstein are in Correspondence folders, Box 21.

Frank records this information in one of his many notebooks. This notebook contains titles of articles, dates of completion, numbers of words, and information on if and when a piece was published. If published, Frank provides the name and date of the publication. See Waldo Frank Collection, University of Pennsylvania Rare Books Collection, Restricted, Box 47.

Letter from Leo Ornstein to Waldo Frank, 25 February 1915.

Letter from Pauline Ornstein to Peter Ornstein, n.d., written in the 1970s (private letter in possession of Peter Ornstein's daughter, Holly Carter). We want to thank Holly Carter for sharing this correspondence with us.

In 1926, Frank published a detailed portrait of Ornstein in an unusual book with the unwieldy title Time exposures, by Search-light: being portraits of twenty men and women famous in our day, together with caricatures of the same by divers artists, to which is appended an account of a joint report made to Jehovah on the condition of man in the city of New York (1926), by Julius Caesar, Aristotle and a third individual of less importance.67

Waldo Frank, Time exposures, by Search-Light (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1926).

By 1926, Ornstein had significantly reduced his concertizing schedule and was teaching in Philadelphia. Frank's chapter in the book was an attempt to explain why he did that. It is a hagiographic account, pitting Ornstein as “Music” against the concert world of managers, critics, and press, labeled the “Machine,” in which the Machine ground down Music. Frank's first encounter with Ornstein, taken from this book, has already been quoted. The rest of Frank's chapter has the same allegorical tone. Frank makes Ornstein a martyr to his art: “And the rite began in which was sacrificed the circus-performer, the Pullman-jumper, the darling of thrilled ladies—in which was produced the scarce known Ornstein of to-day.” Given Ornstein's continuing presence in the New York and Philadelphia music scenes throughout the 1920s and '30s, Frank's remarks are dramatically overstated. Ornstein certainly pulled back from the near maniacal schedule he had kept between 1916 and 1920, but he did not disappear from the scene altogether. He continued to perform, and his name was still known and used to endorse many musical projects. As with much of Frank's writing, the author appears to get caught up in his own emotional creations without letting facts check his prose.68

Frank, Time Exposures, by Search-light, 144–46. Frank's connections with the Stieglitz Group and the famed photographer may well have informed the title of his book.

Ornstein collaborated in two artistic projects with Frank. The first was the Poems of 1917, published in 1918. With a prose poem “Prelude” by Frank and ten programmatically titled solo piano pieces by Ornstein, the two men crafted a joint artistic response to the world war. Ornstein's piano poems appeared as musical analogues of the works of the soldier-poets Wilfrid Owen, Ivor Guerney, Issac Rosenberg, and Siegfried Sassoon, whose heartrending verses brought the inhumanity of war home on both sides of the Atlantic. Later, in 1927, they collaborated again on a set of five songs, Ornstein's Five Songs, op. 17. While these songs had nowhere near the impact of the Poems of 1917, Leopold Stokowski was sufficiently interested in them to request an orchestral version, which Ornstein provided. To our knowledge this version was never performed.

Starting in 1916, Paul Rosenfeld began a thirty-year career of arts criticism that resulted in 196 articles and four books devoted exclusively to music, as well as others that touched upon the subject. Four of his articles focused on Ornstein, three of the books had lengthy passages on the composer, and another was dedicated to him.69

See Charles L. P. Silet, The Writings of Paul Rosenfeld: An Annotated Bibliography (New York: Garland Publishing, 1981) for the most thorough listing of Rosenfeld's critical works. Rosenfeld dedicated his 1924 book Port of New York to Leo Ornstein.

What became of the plans for Steinway Hall is not known. It is likely that given the late date of the initial discussions, the hall had already been booked. The Reis recitals took place on four Sunday evenings: March 5 and 19, and April 2 and 16. See Metzer, “The Ascendancy of Musical Modernism in New York City, 1915–1929,” 352.

For a time, Paul Rosenfeld, Waldo Frank, and Ornstein were all close. Over the years they developed a complex triangle of relationships colored in part by the petty jealousies that attend many group friendships, and Rosenfeld's tendency to ignore personal feelings or notions of loyalty when it came to his published criticisms. After Ornstein moved away from radical modernism in his compositions, Rosenfeld moved on to champion other composers, but Waldo Frank remained Ornstein's closest friend for at least the next forty years. The exact relationship between Frank and Ornstein, Rosenfeld and Ornstein, and Frank and Rosenfeld is not clear. Although letters from Ornstein and some tantalizing albeit ambiguous comments in Frank's diaries regarding Rosenfeld suggest a degree of intimacy, there is no doubt that for a period of time Frank, Rosenfeld, and Ornstein formed a tight triangle.

When Ornstein was at the peak of his fame, numerous others wrote articles, reviews, and chapters on the pianist/composer, including some of the most famous names in modernist literary and artistic circles: Lawrence Gilman, Carl Van Vechten, Charles L. Buchanan, Winthrop Parkhurst, William J. Henderson, Gdal Saleski, and Margaret C. Anderson. Ornstein became both a cause célèbre and whipping boy. While Reis, Rosenfeld, Frank, and Kramer formed one circle pushing modernism, they were part of a much larger and more established circle. Photographer Alfred Stieglitz's “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue,” known as “the 291,” had been a meeting place and focal point for artistic activity and discussion since 1905. The Stieglitz Group, as they became known, included photographer and cofounder Edward Steichen and a roster of artists and writers whose names would soon become synonymous with American modernism: Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Alfred Maurer, Georgia O'Keeffe, Abraham Walkowitz, and Max Weber, to name a few. Participants of a more literary bent included Hart Crane, Edmund Wilson, and Ornstein's close friends Waldo Frank and Paul Rosenfeld.

As Ornstein's inner circle became wider and better placed, opportunities were presented to collaborate with still more and different people across the arts. It is likely that through his friendship with Waldo Frank, Ornstein was mentioned to the up-and-coming writer and critic Edmund Wilson who needed a composer-collaborator on a new project he was imagining, and who would become yet another important associate of Ornstein's.

In 1923, Wilson and Ornstein collaborated on a major theatrical project, “Cronkhite's Clocks,” for the Ballets Suédois, a dance group formed in Paris in 1920 as an alternative to the by then famous and entrenched Ballets Russes. Its multidisciplinary approach, which often relegated dance to a status secondary to drama, painting, film, or acrobatics caused the company to be viewed by many as even more adventurous than the Russian troupe. As Nancy Van Norman Baer has observed, “The Ballets Suédois would come to be identified as much with the dynamic interpretation of visual arts as it was with dance…. it willingly ceded control of production aspects to the visual arts it employed.”71

See Nancy Van Norman Baer, “The Ballet Suédois: A Synthesis of Modernist Trends in Art,” in Paris Modern: The Swedish Ballet 1920–1925, ed. Nancy Van Norman Baer (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1995; distributed by the University of Washington Press), 10–37. Baer points out that given Rolf de Maré's interests, “the intentional pictorial emphasis of Ballets Suédois productions is hardly surprising” (12).

A similar situation existed early in Meredith Monk's career. The discipline-bending work of Ms. Monk meant multiple critics attended her performances.

The Ballets Suédois made its American debut in New York in November 1923. Edmund Wilson was hired as the American press agent for the company, and after seeing the success of it debut work, the satirical “Within the Quota,” which surprisingly had music by Cole Porter, Wilson was inspired to create his own Ballets Suédois story-scene; by December 1923 he had started writing “Cronkhite's Clocks.” Like many of his contemporaries, Wilson was a fan of Charlie Chaplin. As early as 1919, Waldo Frank had spoken enthusiastically of Chaplin as the nation's “most significant and most authentic dramatic figure.” Frank explained why he felt so strongly: “Within the cultural limitations imposed upon him by his public, he is a perfect artist. Inimitably graceful, mobile of body and feature, capable of a kaleidoscopic scale of feeling from tears to laughter, from ‘rough-house’ to the most delicate mimic dance, where is his equal in our dramatic world?”73

Waldo Frank, Our America (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1919), 214.

In January 1924, Wilson wrote to his friend John Peale Bishop, a former Princeton classmate, describing his dramatic project as “a great super-ballet of New York.” He enthusiastically explained that “it would include a section of movie film in the middle, for which Ornstein is composing the music and in which we hope to get Chaplin to act. It is positively the most titanic thing of the kind ever projected and will make the productions of Milhaud and Cocteau sound like folk-song recitals.” Wilson described the dramatis personae and sounds: “It is written for Chaplin, a Negro comedian, and seventeen other characters, full orchestra, movie machine, typewriters, radio, phonograph, riveter; electromagnet, alarm clocks, telephone bells and jazz band.”74

Edmund Wilson, The Twenties, 153; excerpts of Wilson to John Peale Bishop, 15 January 1924, Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries, quoted in Gail Levin, “The Ballets Suédois and American Culture,” in Baer, Paris Modern: The Swedish Ballet, 1920–1925, 124.

Chaplin did not consent to the Wilson-Ornstein project, preferring instead to appear only “in shows that he himself created.”75

Levin, “The Ballets Suédois and American Culture,” 124.

Reis, Frank, and Rosenfeld represented the nexus between the Bertha Feiring Tapper circle and the Stieglitz Group. With feet in both camps and Ornstein an enthusiastic participant, they were perfectly poised to bring music into the modernist mainstream. When Ornstein married Pauline Mallet-Prevost on 13 December 1918, Rosenfeld, as a gift for the occasion, presented Ornstein with a painting by John Marin, an important Stieglitz acolyte, and a close friend of Rosenfeld's. The extent of Ornstein's relationship with Marin or the precise circumstances of their first meeting is undocumented, although members of both Ornstein's and Marin's surviving families agree the two men knew each other. In both temperament and experience they would have had much in common. The Ornstein family also remembers that Ornstein was relatively close to Georgia O'Keeffe, who married Stieglitz, although we have found no corroborating evidence for that assertion.

It was likely Marin who introduced Ornstein to the artists William Zorach (1887–1966) and Marguerite Zorach (1887–1968). Marin had exhibited at a number of shows with the Zorachs. They were successful and well known in New York modern art circles and friends with not just Marin, but also Abraham Walkowitz and Max Weber of the Stieglitz Group.

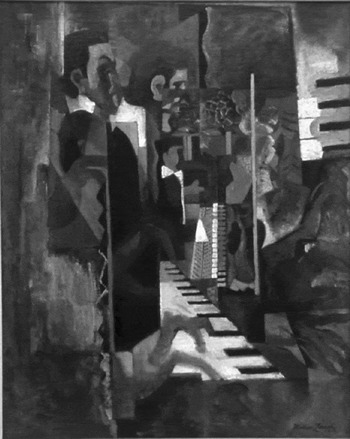

Just before William Zorach turned from painting to devote himself almost exclusively to sculpture he created one of the most striking portraits of Ornstein that exists, Leo Ornstein, Piano Concert, 1918.

The futurist painting vibrates with the energy and excitement regularly ascribed to Ornstein's concerts. One can feel the momentum of Ornstein's hammering hands. Zorach was taken with the raw power of the young pianist, and according to one account later regularly bemoaned the disappearance from the arts scene of one so promising. According to John Marin's daughter-in-law Norma Marin, who knew the Zorach family well, “Bill Zorach told of Leo Ornstein all the time. How very gifted he was, how he led an unfortunate life. So much talent and then he disappeared.”76

We are grateful to Ms. Marin for her gracious hospitality and many insights regarding the Marin and Zorach friendship. She shared these with memories us in an interview on 16 July 2004 at Cape Split in Addison, Maine at John Marin's former home, which she now owns.

William Zorach was born 28 February 1887 in Eurburg, Lithuania. The Zorachs came to the United States in 1891 as one of many Russian-Jewish families who escaped an inhospitable environment. Ornstein's family did the same in 1906 for similar reasons. The Zorachs settled in Port Clinton, Ohio, just outside of Cleveland. Between 1910 and 1911 Zorach traveled to Paris to study art. In December 1912, he married Marguerite Thompson, whom he met in Paris, and in 1913, they both had paintings in the Armory Show in New York, the city in which they settled.

Plate 1. William Zorach, Leo Ornstein, Piano Concert, 1918. Reprinted with permission of The Zorach Collection, L.L.C.

Plate 2. Leon Kroll, The Musician—Leo Ornstein. Reprinted with permission of The Art Institute of Chicago.

Zorach's portrait might be the most famous of Ornstein, but he was the subject of many other renderings. Had no written artifacts detailing Ornstein's importance to America's early modernist culture survived, the number of paintings, drawings, and sculptures that were made would prove his centrality to the movement. His youth, his notoriety, and his aesthetic mien made him an ideal object for artists attracted to his music. Leon Kroll, at one time the president of the Society of Painters, Sculptors and Graveurs, chairman of the art committee of the Academy of Arts and Letters, winner of numerous awards at major art shows, and cousin of William Kroll, violinist of the Kroll Quartet, painted his own portrait of Ornstein in 1917, The Musician—Leo Ornstein.78

In the 1920s, William Kroll taught at the Institute of Musical Art, the same institution from which Ornstein graduated in 1910.

The painting projects a different Ornstein. As Leon Kroll explained in his memoirs, his father had played both the cello and bass viol: “I was brought up knowing something about music.” Kroll's comfort around musicians informs the work. The dramatically simple portrait in shades of blue and brown captured the twenty-four-year-old from the perspective of the painter, seated close by, viewing him through the raised lid of the grand piano as he played. The lack of distracting detail conveys an architectural clarity and modernity to the work. Ornstein's open-collared shirt and loose-fitting jacket suggest an intimate, private moment. His eyes are closed, his head is tilted just slightly downward; his graceful left hand is raised and hovers over the keyboard as if he is divining the sounds. Kroll caught the artist in a moment of mystic communion with his music.79

The painting by Kroll is owned by the University of Virginia Art Museum. For information on it and on Leon Kroll see Nancy Hale and Fredson Bowers, eds., Leon Kroll: A Spoken Memoir (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983).

While these artists did not specifically promote Ornstein in a way that the Reis–Rosenfeld–Frank circle did, it is clear that they were taken with him as an artist and as one they considered important to emerging modernism. The existence of the paintings testify not only to their interest in Ornstein but in music as part of the modernist movement.

Yet if Ornstein's relationships with Marin, Kroll, and the Zorachs were occasional, his associations with Rosenfeld and Frank were central. Ornstein's personal interactions with Rosenfeld reached their peak prior to his marriage in 1918, with the two men summering in Maine in 1915 and 1916. A letter Rosenfeld wrote to Reis in July 1915 expressed the many reasons Rosenfeld was drawn to Ornstein. After reporting on “how very sick and feeble Mrs. Tapper had been feeling all summer,” Rosenfeld launched into what became a homily on the conjoined relationship of art and life, and Ornstein's embodiment of their unity: “I needn't protest to you that I love art, I consider it one of Life's greatest privileges to serve her. But—how does art that [is] warm-hearted, impure, behave? How does the art that comes from fear and cowardice and self-intoxication react to life? Quite in the manner of Tristan and Isolde in offering a substitute for some of the grand emotions…. And I contend that it is important to give their emotion back to life and to draw them away. For we want fuel to heighten that imagery that seeks to transform matter into spirit, and that fuel can only be given the world by artists of grand and lofty impulse, free and brave and glorious. Don't you agree.” Rosenfeld's aspirations for a transcendent art are already evident, as is his tendency toward emotional prose.

At this point in the letter, Rosenfeld refers back to earlier conversations with Waldo Frank when the two men had discussed similar ideas: “And that is why I feel that life and art go hand in hand. For both aspire alike…. Waldo explains [that] my attitude is a realization that I will never be a first-rate artist and his own is a realization that we have to give up life in order to be a first-rate artist. And there it stands. The question that only time can decide.”80

Letter from Paul Rosenfeld to Claire Reis, 25 July 1915, Claire Reis Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Research Division.

As the letter draws to a close, Rosenfeld imagines his hopes for the fully integrated art-life realized in Leo Ornstein: “I think Leo is on the same track. For he's thrown ‘art’ over, and gives back to life, and to nature, and the song of the winds and the birds and the beating of his own heart, as the only truth. Energy, energy, is his continual cry. And so his hatred of concerts and so much art, and his own desire to awake the spirit of individual expression, and to seeing the world through his own eyes. I think for Leo the creation of beauty is far less important than the sensing of that beauty, and that his art aspires not to the making of fine music but to the making of fine people. Only in that sense does ‘all service rank the same with God’ if I have love at heart. And that love casts itself in the artist, too.”81

Rosenfeld's citing of Ornstein's cry of “energy, energy” recalls Stephen Lloyd's discussion in “Grainger and the ‘Frankfurt Group”’: “In one respect ‘energy’ was a musical characteristic of the Group (especially with Grainger at the fore). Its symbolic manifestation was in the ‘English Dance,’ a title shared by Grainger, Scott, Gardiner and Quilter” (115). Ornstein's most famous piece, Danse Sauvage, was a dance as well.

Rosenfeld does not question whether Ornstein had any such lofty aspirations for himself or his music. He pins his hopes on Ornstein as a musical artist capable of real transcendence, and in the process he transports himself with his own prose. Catching himself, Rosenfeld apologizes to Reis: “Pray forgive me if I've preached, I've been priggish. I know you'll understand.”82

Ibid.

In the nine-year period beginning in 1913 and lasting to 1922, when the International Composers' Guild was launched, three circles of musicians, writers, artists, and promoters actively influenced American musical culture. The first, the Frankfurt Group in England, had only an indirect influence on Ornstein, though an important one. They provided the forum for Ornstein's first modernist public outings, reinforced Ornstein's own compositional preferences, and bolstered his belief in the cause he would champion in the United States. The second, the Tapper–Reis–Rosenfeld–Frank circle, included individuals whose activities in the 1920s would be essential in disseminating modernism on American shores. That circle revolved around Ornstein, whom they used (and who used them) to advance personal and artistic agendas.

Third is the much broader Stieglitz Group, which for at least a time was the locus of modernism in the United States. Many of the people around Ornstein had specific links to this circle, and Ornstein soon developed his own ties to its members. Later, as the small literary magazines became a force in their own right, they formed their own circle. But during the late teens, their writers were as much at home in the Stieglitz Group as were artists.

Thus as early as 1915 writers, artists, and other musicians formed a coterie to advance a modernist agenda, with Ornstein as one of the central orbs around which people in many different spheres circled. Ornstein sought and maintained contacts, and actively promoted himself and musical modernism. Contrary to received wisdom, musical modernism did not stand apart from the broader modernist movement sweeping America in the 1910s. In large part, through Ornstein modernism acquired its public sound and its public face, and in what may be Ornstein's greatest contribution, modernists began to pay attention to music. Artists embraced music, and modernist writers began to write about music in their journals and books, such that when the movement finally flourished in the 1920s, music already had an accepted place in the literary journals of the time.

Prior to 1922, musical modernism was alive and well; it did not take Varèse and later Copland to imprint it upon the American artistic world. They opened shops, which prospered, but a clientele was already in place. Ornstein was a focal point around which an active modernist movement began to unfold in the United States well before the 1920s. To return to the image of the fitness landscape, Ornstein did more than leap by himself to a new mountain; he brought much of the intellectual and artistic world of the 1910s with him.