Cornerstone Festival was an annual four-day-long Christian rock festival in Illinois that ran from 1984 until 2012, first in Chicago's northern suburbs and then, from 1991 onwards, on a former farm in the rural western part of the state, near Macomb. The event was organized by members of Jesus People, U.S.A., or JPUSA, a Chicago-based Christian intentional community (or commune) with roots in the Jesus People Movement, an evangelical counterculture that emerged in California in the late 1960s. Cornerstone's organizers marketed it as a sober, family-friendly festival, presenting self-identifying Christian musicians to a primarily Christian audience. Cornerstone reflected the values of JPUSA's members, particularly those of John Herrin, the festival's former director and, as a founding member of the long-running Christian rock group Resurrection Band, a former professional musician himself. An ethos of interdependence—necessary for the long-term sustainability of communal living—permeated Cornerstone. By “interdependence” I mean the need and the privilege to rely on one another, cooperating intentionally and joyfully in many aspects of life, including labor, leisure, and homemaking. Festival staff and volunteers articulated and enacted JPUSA's particular interdependence before and during the event itself, as they prepared the festival grounds for an influx of up to 25,000 paying attendees and 300 bands. Attendees and bands experienced Cornerstone's interdependence most directly through the “generator stages”: unofficial, attendee-operated venues throughout the festival site whose unofficial programming complemented the event's official schedule of events (which included concerts, crafts, seminars, sports, and worship services every day). Most attendees camped on-site, and many arrived one or two days early before official programming started, when the campgrounds opened. Although attendees were able to leave and re-enter the grounds at will, in practice Cornerstone was relatively isolated from the surrounding towns and communities.Footnote 1 Like many contemporary multi-day festivals in relatively rural or remote locations, Cornerstone's festival grounds and campsites functioned as an ephemeral village. In many ways, Cornerstone was similar to other music festivals and Christian events. Interdependence is key, for example, to the success of Burning Man, a festival in northwest Nevada whose organizers provide only minimal infrastructure and programming, as well as campsites at Christian festivals (such as Creation) and non-Christian festivals (such as Coachella).Footnote 2 But Cornerstone's mix of official and unofficial programming is relatively unique: its performance contexts are not quite as participatory as Burning Man, but also not as presentational as most other music festivals.Footnote 3

In the United States, Christian conventions and retreats have long provided sites of religious education, reflection, and renewal (and also recreation) far from attendees’ homes and the routines of their daily lives. Cornerstone thus participated in a longer tradition of Christian events, including Explo ’72, the high-water mark of the Jesus People Movement and the first major event to bring together Christian rock with more traditional seminars on religious topics and evangelism.Footnote 4 But Cornerstone's organizers also intentionally set it apart from other Christian events. As Shawn David Young has described, “the JPUSA community felt the need to offer a venue where Christian musicians felt free to perform music typically not accepted by the Christian mainstream (whether due to style or to lyrical content). … Cornerstone highlighted a subcultural aesthetic often absent from gatherings sponsored by the gatekeepers of establishment evangelicalism.”Footnote 5 At Cornerstone, subcultural musical aesthetics were valued over “mainstream” contemporary Christian music (or CCM). Indeed, the festival provided a liminal space that inverted genre hierarchies and subverted genre conventions, like opera at Stratford and Banff, orchestral music in the early years of Chicago's Grant Park Music Festival, as well as jazz at Havana Jazz Plaza. In an interview, John Herrin, Cornerstone's former director, described the festival's origin in 1984 as an alternative event that would feature music that other Christian festivals were ignoring. At that time, he said, “there were more and more independent, really creative [Christian] artists that were … a little too wild to play a part of the fairly conservative Christian music scene. … We felt from the beginning that Cornerstone needed to feature the artistic end of the Christian music world.”Footnote 6 As you walked through the event, this goal was obvious and audible: Cornerstone privileged peripheral, youth-oriented music genres and styles over mainstream Christian recording artists. Instead of CCM, gospel, hymnody, praise and worship, or other sacred musics, the festival's ideological and stylistic elements had more in common with contemporaneous emo, goth, hardcore, indie rock, metal, and punk rock, relatively marginal genres that have been supported by passionate local and trans-local scenes in the United States and elsewhere.

In this article, I use examples from my ethnographic fieldwork at Cornerstone Festival to consider what the interdependence I observed and experienced there might contribute to scene theory.Footnote 7 What do we gain by studying annual festivals as scenes? What can music festival research contribute to scene theory? It seems obvious that music festivals can be analyzed as scenes, inasmuch as spatial proximity (both physical and virtual) is a key characteristic of scenes.Footnote 8 But doing so necessarily expands scene theory as a framework that has long privileged the consistent interpersonal and social interactions that spatial proximity benefits, because most festival attendees do not interact as a community outside of the intense period of the event itself. Herrin told me that many attendees find Cornerstone to be an essential community that validates their interests and values in ways they do not find in their daily lives: “A lot of these folks live all over the country … and interact everyday with people that are not like-minded. This [Cornerstone] is a chance to come together.”Footnote 9 If scenes are valuable in part because they bring people together to celebrate shared affinities, experiences, and values, then Cornerstone is an obvious fit; but if scenes are also valuable because their sociality and spatiality are consistent and ever-present, then how do we account for scenes that are ephemeral or inactive for most of the year?

My research into Cornerstone Festival demonstrates that the intersecting relationships between place, space, and values (both communal and individual) at music festivals are uniquely tied to festivals’ limited duration. That is, festival research makes valuable contributions to scene theory not despite festivals’ ephemerality but because of it. This is possible because attendees and bands count on annual festivals returning every year—they may be ephemeral but they are also stable. As physical sites, festivals substantiate imagined communities that might otherwise lack a local, material infrastructure.Footnote 10 In general, imagined communities and scenes are not interchangeable: while the latter describe proximal collectives in which social interactions are essential to communal identity, the former describe collectives in which shared affinities are themselves sufficient social bonds, particularly when they are made accessible and intelligible through mass media. Festivals bridge these two frameworks, granting their imagined communities a more tangible sociality, even if only for a few days every year, and granting their scenes a permanent presence in attendees’ daily lives outside of festival season, when their proximal spatiality obviates this need.

I first attended Cornerstone for ethnographic fieldwork in 2009, and I returned in 2010 and 2012 (the event's final year) to volunteer. In both 2010 and 2012 I worked as a stagehand at the Gallery Stage, one of Cornerstone's many official venues. Additionally, in 2010, I arrived a week early and stayed several days late to work on the festival's setup and teardown crews. I also interviewed Herrin and conducted ethnographic fieldwork at JPUSA, whose members organized and operated Cornerstone for twenty-nine years. Through this unique access, I came to understand Cornerstone not (only) as the four–day–long festival that attendees experienced but also as an event through which its organizers, staff, and volunteers articulated, embodied, practiced, and reaffirmed their own values. As Timothy Storhoff describes further in this issue of JSAM, festivals serve as sites of ritual and pilgrimage.Footnote 11 This insight is multivalent for Christian festivals like Cornerstone, which often function as religious journeys and places that enable spiritual reflection, renewal, and transcendence separate from the routines of daily life. Even preparing the grounds and producing the event carried ritual significance for festival staff and volunteers. If Cornerstone was indeed a scene, it was one that reflected the goals of all involved in its creation, year after year.

Music Festivals as Scenes

In a now-classic article, Will Straw wrote of scenes as “cultural space[s] in which a range of musical practices coexist, interacting with each other within a variety of processes of differentiation, and according to widely varying trajectories of change and cross-fertilization.”Footnote 12 In a more recent article, Straw expanded this definition and argued that observers might consider scenes to encompass some or all of the following:

as collectivities marked by some form of proximity; as spaces of assembly engaged in pulling together the varieties of cultural phenomena; as workplaces engaged (explicitly or implicitly) in the transformation of materials; as ethical worlds shaped by the working out and maintenance of behavioural protocols; as spaces of traversal and preservation through which cultural energies and practices pass at particular speeds and as spaces of mediation which regulate the visibility and invisibility of cultural life and the extent of its intelligibility to others.Footnote 13

Lawrence Grossberg clarified that Straw's discussion of scenes allowed for their relative impermanence and for the inclusion of distinct musical genres and styles.Footnote 14 In other words, scenes are not necessarily tied to a particular style of music or a specific musical community, nor are they permanent features of a cultural landscape. Despite this flexibility, however, music scenes have frequently been examined as cultural spaces in which a limited set of related musical practices exist: scenes are often defined by a set of unified aesthetic approaches. Indeed, participants and observers alike often explain the emergence of new (or newly divergent) aesthetics as products of social and spatial relationships unique to particular scenes; consider, for example, the association of punk rock with New York City's CBGBs scene in the 1970s, house music with Chicago in the 1980s, and grunge with Seattle in the 1990s. A scene's impermanence enables its critical assessment: the relationships that ground its most significant contributions are rooted in particular places and times, beyond which its influences and legacies continue to echo and reverberate. No scene is permanent; even if a scene's material conditions remain unchanged over an extended period of time, its social conditions do not: scenes age, mature, and reinvent themselves as old participants leave and new participants join, bringing with them new affinities, influences, and networks.

Festivals are less permanent than most scenes, existing for a short time every year. As Timothy Dowd, Kathleen Liddle, and Jenna Nelson argued, however, festivals pack a lot of experience into a short amount of time and a small amount of space: their intensity compensates for their infrequency.Footnote 15 Like more traditional scenes, festivals are bounded, with all activity taking place within a proscribed set of boundaries. But, as Dowd et al. explained, these boundaries are defined not by the organic growth and development of a traditional scene but rather by the festival's organizers, who make decisions about where to hold the event, which musicians to book, and what audiences to target—thus setting the festival scene's geographic, aesthetic, and social boundaries. Finally, they argued that “music festivals often create change beyond their own borders,” impacting other music scenes far away as well as the surrounding local economies and ecologies.Footnote 16

Cornerstone exemplified these characteristics: following Straw, it existed as a collectivity and a space of assembly; for its staff, volunteers, speakers, and performers it was also a workplace; in curating “independent, really creative [Christian] artists” it functioned as a space of traversal, preservation, and mediation; and it was also an ethical world that articulated the particular values of its organizers. The event's intensity was heightened by the dozens of sessions available to attendees every day, compressing an entire year's worth of concerts, seminars, and social activities into less than one week. The site's remoteness and the forced intimacy of camping also played a role. Most campsites consisted of a large tent or a circle of small tents facing a common area with camp chairs and cooking equipment; parked cars bounded each space. Elaborate sites included an open-sided shelter for the common area, improvised clotheslines for laundry and cooking utensils to dry, old furniture, recreation and sports equipment, and tables. Simpler sites had a single-person tent or lean-to against a car with no visible cooking equipment. While some attendees arranged their vehicles to provide a degree of privacy, most sites faced the road: campers often paused conversations to greet passers-by, children and teenagers came and went with frequency, and adults chatted with neighboring camps. Friendships blossomed on the campgrounds, with many attendees camping in the same area every year, connecting again with their “Cornerstone family.”

Cornerstone's social and aesthetic boundaries were related; as Herrin explained, he designed the festival to appeal to “people that are either Christians or have some connection to the Christian faith who are more interested in discussion, the arts, I think creative music, fellowship.”Footnote 17 In practice, at Cornerstone this meant booking artists and musicians relatively marginal to the Nashville-based CCM mainstream from the festival's inception, instead privileging styles such as Christian hardcore, metal, and punk bands. This approach meant that the event was less appealing to attendees who were not fans of those genres. Herrin told me that by prioritizing youth-oriented aggressive rock styles, he alienated long-time attendees with different tastes. But these choices also solidified Cornerstone's status as the central physical node that connected several smaller local scenes. John J. Thompson, a Christian music industry executive and former Cornerstone staff member, explained to me in an interview, “Cornerstone was the mothership, it was exclusive, you couldn't find those bands anywhere else. Most of those bands didn't ever tour, there wasn't enough places for them to play to do a tour. … [But] they played at Cornerstone. That was their tour. They could hit all of the interested people in one week. Those people could go out and tell their story and spread the word.”Footnote 18 For these bands and their fans, Cornerstone sustained musicians’ careers and attendees’ fandom, creating change beyond its borders.

The “Cornerstone Experience”

The first time I attended Cornerstone, I was struck by the event's geographic specificity and also by its community's commitment to the event: in many ways, this festival achieved its greatest potential through the engagement and interdependence of its attendees. In her study of the indie rock scene in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, Holly Kruse wrote that music scenes “are best understood as being constituted through the practices and relationships that are enacted within the social and geographic spaces they occupy.”Footnote 19 For Kruse's scene participants, one's subjective positioning within the scene was tied both to social status (for example, as a record store clerk, college radio DJ, or member of a local band) and to specific places: public locations such as record stores and music venues; semi-public or professional places such as college radio stations, record label offices, and recording studios; and even private areas such as rehearsal spaces and scene members’ homes.Footnote 20 She concluded that the viability of a music scene within a particular geographic area or region depended on the availability and affordability of these places, many of which were businesses that had to cater, at least in part, to the demands and expectations of their markets. In Barry Shank's analysis of the rock ’n’ roll scene in Austin, Texas, he argued that these specific places—indeed, the scene itself—enabled and encouraged participants to explore and perform new identities.Footnote 21 These practices took place within specific cultural and economic contexts, and the entire first chapter of his book Dissonant Identities offered a virtual walking tour of Austin's scene that necessarily contextualized his ethnographic present within a longer historical context.

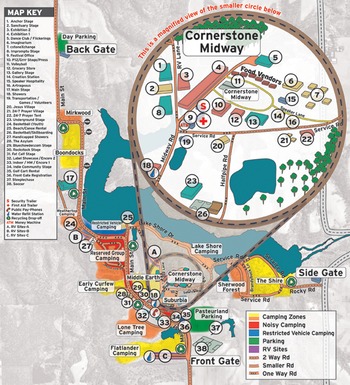

In 2009, I embarked on a walking tour of Cornerstone myself soon after I arrived at 11:00 a.m., just in time for the first day of the festival's official programming. I parked in a pasture just inside the front gate. The gravel road was lined with large circus tents and open-air stages, which were in turn surrounded by campsites. There were no cars on the road; instead, festival attendees were everywhere: on bicycles, driving golf carts, but mostly walking. Some were headed to the showers with towels and toiletries, and many were leaving a centrally-located food vendor with plates of pancakes. I saw people at their campsites sitting in circles, heads bowed for prayer; others prepared breakfast over camp stoves. I wandered into a Bible study at the Impromptu Stage (Figure 1, #8) where most of the crowd was sitting in their own folding camp chairs. After watching a band at the nearby Anchor Stage (#1) play a couple of songs, I browsed the two merchandise tents (#3 and #4), which were populated mostly by record labels and t-shirt vendors. I explored the festival's Midway and located the Gallery Stage (#13), seminar tents (#7), and food vendors. I also found an on-site convenience store (#2) and the press tent (#10). Later in the day, following an afternoon of concert-hopping, I joined the nightly migration to Cornerstone's Main Stage (#17), which was about a twenty-minute walk from the Midway. Main Stage was a big production, complete with a professional stage, PA, spotlights, and giant video screen similar to what I had seen at other music festivals but in stark contrast to the small stages and five-hundred-person tents of the other venues scattered throughout Cornerstone, which were modest in comparison. The stage itself was at the bottom of a natural bowl; fans crowded the stage on foot, sat in camp chairs further away and on the grass hill that rose up from the stage, or observed from the access roads that border it. Close to the stage were permanent structures that housed merchandise and concession sales.

Figure 1. Cornerstone Festival 2009 grounds, reprinted by permission of Jesus People, U.S.A.

As I discovered on my walking tour, Cornerstone's geographic layout lent itself to the serendipitous discovery of music, games, seminars, and more spontaneous events throughout the day. Music venues were close enough to each other that it was an easy (and short) walk from one to the next to hear several different bands within the span of an hour or so.Footnote 22 In contrast to many other camping music festivals, the campsites were more integrated into the festival's performative spaces: you often walked through the campsites while heading from one concert to the next. Doing so made it more likely to meet and befriend new acquaintances, or to stop by your own camp and grab a friend to come with you to the next performance. Following Kruse, Cornerstone's geographic places were not only available and accessible to all attendees, lacking the VIP areas common to many festivals, but aggressively so, as private, semi-public, and public spaces overlapped. The grounds’ compressed geography and campsites’ proximity also encouraged word-of-mouth among the festival's attendees. News and hype about popular bands spread quickly and was relatively easy for attendees to act on. Furthermore, a sense of urgency permeated the festival—if you somehow missed seeing your favorite musicians or a new artist who could have become your favorite band at Cornerstone, you might have had to wait an entire year for the opportunity to see them perform again. Thus, attendees often heeded their friends’ recommendations and spent their afternoons and evenings attending successive (and often overlapping) performances with little downtime. In other words, the event's sociality and spatiality were interrelated and also intensified by its limited duration.

Leaving your everyday identity and routine at home was part of the point of attending Cornerstone: at no other place would you have had the opportunity to camp, swim in a lake, attend a Bible study, play volleyball, eat a funnel cake, listen to a seminar speaker, and attend five or six concerts in a single day. Both Kruse and Shank emphasized the importance of locality to scenes: in their analyses, the relationships between music communities and the geographic places in which their participants circulated were so strong and multiple that the two were essentially co-constitutive. The same was true at Cornerstone: the name of the festival itself became synonymous with its scene, the styles of music encountered there, the bands who played that music, and the fans who listened to those bands. Face-to-face interaction was also an important component of Kruse's and Shank's local scenes, enabled and encouraged by physical infrastructures, social networks, and geographic boundaries. At Cornerstone, as I have already described, the grounds’ spatial layout enabled and encouraged its social and cultural experiences.

Some writers have noted that strong local scenes often participate together in trans-local networks. For example, Alan O'Connor demonstrated that vibrant punk scenes in Toronto, Ontario, Washington, D.C., Austin, and Mexico City were frequently inspired by and dependent upon trans-local mediascapes.Footnote 23 Kruse, writing elsewhere, noted that trans-local networks of social and cultural exchange “brought institutions and people in disparate local scenes together in broader systems of cultural production and dissemination,” essentially building a trans-local scene greater than the sum of its parts and enhancing local scenes.Footnote 24 For much of Herrin's tenure as director, his vision of Cornerstone as the only major festival that booked “independent, really creative [Christian] artists” meant that it had an outsized influence on smaller, local scenes around the United States. As Thompson recalled in an interview, “Cornerstone was just so radical compared to most Christian music back when I was a kid. Not only could you not see those bands at other festivals, but those other festivals wouldn't even think the Cornerstone stuff was Christian. There was no comparison.”Footnote 25 Bands would travel to Cornerstone, perform for “all the interested people,” and make enough money selling merchandise (cassettes, CDs, t-shirts, posters) to sustain themselves until the following summer.

Others have argued that scenes’ virtual spaces can serve functions similar to their physical ones. In their relative permanence they provide spaces where scene participants regularly gather and perform their identities: in the pages of fanzines, online message boards, email discussion lists, the comments sections of websites like Stereogum and The Onion AV Club, and (increasingly) social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.Footnote 26 For many scenes, online and virtual media frequently replace face-to-face interaction, enabling fans, cultural intermediaries, and musicians to participate daily in imagined communities united by shared tastes and affinities despite being geographically disbursed.Footnote 27 For example, Diane Cormany observed posts on Coachella's official message board in 2011, where she learned that online interaction outside of the festival itself “sustains relationships between dedicated festival fans and thereby actual [sic] constructs their scene.”Footnote 28 During Cornerstone's peak years in the late 1990s through the early 2000s, however, those virtual spaces were not very important components of its scene. Fans discussed Cornerstone in a variety of forums: a Usenet group (rec.music.christian), LiveJournal, MySpace, and a message board on Cornerstone's website, but none of these provided a lasting central location where a plurality of Cornerstone fans constructed their scene.Footnote 29 Herrin told me that, outside the festival, participants’ musical lives might be curbed by family, professional obligations, geographic separateness, or cultural stratification. Musicians and fans often found themselves doubly marginalized: ostracized from their local hardcore, metal, and punk scenes because of their sincere faith identities yet also ill-fitting within their church communities due to their musical tastes and personal styles. Attendees often spoke of their “Cornerstone family”: they encountered and constructed a sense of belongingness that accumulated over time, centered at the festival itself and anchored by fellow long-time festival goers.

For many years, the nightly gatherings at Cornerstone's Main Stage served as a central gathering point. From my vantage point near the top of the hill at Main Stage in 2009, I was able to gauge the audience's anticipation for each upcoming band based on the changing size of the crowd at the bottom and the number of people walking past me—an embodied barometer of the scene's judgement. All of the official stages and some of the unofficial generator stages also held concerts throughout the evening, so attendees had plenty of choices. In 2009, Wednesday night's final band, a pop/punk group named Relient K, was the most popular: fans rushed down the hill on either side of me, and the crowd at the stage nearly doubled in size. After Relient K finished performing, I walked back to the central area of the festival with the rest of the crowd. For those who had the energy, there were still more bands to see: both Encore Stages (Figure 1, #32 and #33) hosted concerts until 1:30 a.m., and a dance tent (#5) hosted DJs until 1:00 a.m. or later. During this first visit to Cornerstone I had been overwhelmed all day by the number of concerts from which to choose, so I was somewhat grateful to have had limited options as my energy waned. I decided to check out Copeland at Encore 2. When I arrived, the tent was full and the mood was anticipatory. Copeland played mellow, piano-based indie rock, perfectly suited to end the first long day of the festival. Many fans were sitting on the grass, relaxing, nodding appreciatively, and cheering politely after songs. At quiet moments during the concert we could hear the thrash metal of Austrian Death Machine's performance at the nearby Encore 1 Stage, but the Copeland audience seemed content to enjoy the music leisurely and passively, as they were presumably done rocking out for the night.

Space, Place, and Scenes at Music Festivals

Throughout my fieldwork, many attendees told me that Cornerstone provided their only in-person contact with the music they liked, with very few (if any) opportunities to attend Christian rock concerts (including the diametrically opposed Copeland and Austrian Death Machine) and network with other fans the rest of the year. While Christian rock artists do perform and tour regularly, they usually do not play as often as their counterparts in the general (or non-Christian) market. This is partly because the market is simply not as big: there are not enough Christian rock fans and concert venues to sustain a long, large, cross-country tour. As a result, bands play fewer shows that are further between, and many fans would have to drive several hours to attend. Not all fans can afford the time and cost to travel that far for a concert. But the music they heard and the bands they saw perform every summer at Cornerstone became central to their tastes and musical lives. Cornerstone was significant to participants not only as a festival but as a lived community: a space of assembly. When they listened to CDs and revisited their memories of the event, often prompted by photo albums and mementos (like festival wristbands), they reinforced their identities as fans of Cornerstone bands. As Thompson explained, Christian bands simply tour less; thus, performing at Cornerstone and other Christian festivals have become important aspects of these artists’ careers. They spend much of the summer playing the “festival circuit,” performing at events throughout the season instead of touring for several months in a row. Festivals pay more than concerts, which means musicians can afford to spend more time at home; flying to events every weekend is more comfortable than driving in a tour bus or van; audiences are larger, and artists often perceive festivals as an exposure opportunity to perform for new listeners in addition to their existing fans. Festivals themselves, both in the Christian and general markets, have become “destination” events for attendees: because they are multi–day immersive environments, they stand out as special experiences more than a single night out at a concert.

The specificity of a festival's place is essential to its attendees’ lived experiences. Whether festival organizers design their sites strategically (proscribing their scene's boundaries, as Dowd et al. argued) or they emerge more organically, a festival's infrastructure resembles that of the local scenes that Straw, Kruse, Shank, and others described. These physical places are designed and assembled whole by production teams with specific goals and objectives in mind, as opposed to the more gradual development of otherwise disparate places that make up local and trans-local scenes. At Cornerstone, that vision was designed by Herrin's team and executed by another team largely comprised of JPUSA members who supplemented Cornerstone's year-round staff in the weeks leading up to and during the event itself. Outside of the festival, members worked at one of JPUSA's many businesses and missions in and around Chicago; during the festival, they cleaned the showers, cooked for artists and bands, coordinated traffic, documented the event online, kept attendees safe as members of security staff, managed stages, organized sporting events (such as volleyball and soccer tournaments), picked up the garbage, and staffed the front gate, among other responsibilities. The involvement of the entire JPUSA community in running Cornerstone differentiated it from most other festivals, which usually rely on contracted third-party business and volunteers to staff the event. One significant result of the community's involvement is that Cornerstone reflected not only the values of its director and staff but also those of the entire community. Members of JPUSA were invested in the event and committed to its success because it reflected their values as a church (JPUSA is a member of the Evangelical Covenant Church denomination) and as an intentional community that often functioned like a very large family.

My experiences volunteering for the festival's setup crew in 2010 demonstrated that concepts of family and congregational identity—in particular, those central to the intentionally communal identity of JPUSA—can also bleed into the social infrastructures and workplaces of music scenes, complicating them further. My fieldnotes (below) document the timeline of a typical day of work preparing for the festival, several days before Cornerstone's campgrounds opened. John Herrin, his staff, and everyone on Cornerstone's setup crew knew that I was there for research purposes, and they all agreed to be identified by their real names. I witnessed the ways in which work, faith, family, and friendship tightly intertwined and overlapped as, together, we prepared for an influx of thousands of festival attendees and musicians.

Friday, 7:30 a.m.: While volunteering on Cornerstone's setup crew, I stay in the cabin (an old mobile home) of a JPUSA member named Ted. Along with two other JPUSA members, Ted runs the merchandise tents during the festival. Earlier that week, we spent time marking the perimeter of those tents with rolls of bright orange safety fencing and unloading tables and chairs for the vendors. This morning, I enjoy a leisurely coffee with Ted before walking over to Big House, the screened pavilion where we eat communal meals, for breakfast and work assignments. Tom, the grounds manager during festival setup, lead us all in a Bible reading and prayer after we eat.

8:15 a.m.: We split into crews. This morning I am assigned to work with a group of JPUSA teenagers to unload a truck of PA and lighting equipment at Gallery Stage (see Figure 2), where I later volunteer as a stagehand during the festival. Someone gets a forklift stuck in the mud, and we wait for the bulldozer to come haul it out. Although there is still a lot of work that needs to be done before the campgrounds open three days later, we tend not to work efficiently; on this day, we relax, chat, and enjoy the weather while waiting for additional direction instead of asking for new tasks.

Figure 2. PA and lighting equipment at Gallery Stage, Cornerstone Festival 2010, photograph by the author.

12:00 p.m.: Later in the morning, we drive around the grounds, most of us standing in the rear of one of JPUSA's flatbed trucks, looking for large garbage items to take to the dumpster. Lunch back at Big House is leftovers from the prior day's lunch and dinner.

1:15 p.m.: Eric, a JPUSA member who lead one of the commune's head families, asks me and two others to work with him and his son on a small afternoon work crew at the Rec Hall. JPUSA use this permanent building for year-round storage, and we have been hauling materials out of it all week. Now the five of us spend the afternoon cleaning it out: when the rest of the community arrive the next day to finish preparing for the festival, we will eat here instead of at Big House. During the festival itself, this building functions as the artist hospitality area. We work all afternoon, only breaking once to enjoy some lemonade at Eric's cabin, where I meet his wife. We get more work accomplished as a small group with Eric's oversight that afternoon than the comparatively disorganized (but larger) morning crew.

5:00 p.m.: My crew works with Eric right up until dinnertime, and other groups work even later, not arriving at Big House until dinner is well underway. During dinner I sit with Neil and Joey, the only other non-JPUSA members who volunteer during setup week. After dinner the three of us chat with Rich, a JPUSA member who manages the community's skate shop in Chicago and Cornerstone's Underground Stage. He tells us his testimony of recovering from drug and alcohol addiction and arriving at JPUSA three years prior: he only intended to visit for three days but has not yet left.

7:00 p.m.: I take some time in the evening to claim a campsite near the merchandise area, pitch my tent, and unload the rest of my supplies. The rest of the community will arrive the next day in a caravan of JPUSA-owned cars, vans, and buses, and I have one more night to shower at Ted's cabin and sleep in a real bed before moving to my campsite. After my shower, Ted and I chat some more about JPUSA's history; he has been a member for decades and raised a family in the community. He presents me with an amazing gift: copies of ten years’ worth of old Cornerstone program booklets. After we talk I go to bed around 10:00 p.m., ready to get up and work some more the next day.

The leisurely pace of work that I experienced while helping setup Cornerstone in 2010 was possible partly because the festival hired outside vendors to assemble the tents, concessions, sound, and lighting systems. It was also possible because, for many years, the festival grounds doubled as JPUSA's vacation property. Many members, including Ted, had permanent and semi-permanent residences on the grounds as converted trailers, mobile homes, old RVs made stationary, and purpose-built cabins. Other permanent structures such as Big House, the Rec Hall, the showers, and the merchandise booths near Main Stage enabled festival organizers such as Tom to assign work crews (including the one in which I worked) to manual labor jobs without worrying too much about needing specific skills for the bulk of the work. Working together built camaraderie and interdependence among community members, teaching them to cooperate and rely on each other—but also, importantly, to enjoy each other's company and time spent outside instead of rushing to complete job after job on a never-ending to-do list. If the festival was a pilgrimage destination for attendees, for whom their preparations and travel comprised rituals that helped set Cornerstone aside from the routines of daily life, then setting it up and tearing it down was also a ritual process for JPUSA community members, many of whom were responsible for the same tasks year after year. Ted, for example, co-organized the merchandise tents; his neighbor Karl coordinated the art installations and workshops; his son-in-law Thor managed the organized sports; their friend and fellow JPUSA member Glen managed Gallery Stage, where I worked as a stagehand during the festival. Like many other Christian intentional communities, JPUSA was founded in part so that members could pursue their religious callings collectively, relying on each other in all aspects of their lives.Footnote 30 At JPUSA, that calling has long included ministering to the needs of Chicago's homeless population, which they prioritize in part by living more economically as a commune. Not every action at a Christian festival is imbued with religious intent, but at Cornerstone every job and responsibility reinforced the social bonds that held the community together—a community whose togetherness carried religious significance.

Interdependence and Ethics at Cornerstone

At the end of this article I turn to consider Cornerstone's generator stages, demonstrating how scene theory provides a unique analytical lens for this festival. In addition to the hundreds of bands that Cornerstone's staff booked to perform at the event, they also sanctioned attendees to setup their own stages, power their own PAs with portable generators, and independently book bands to perform at Cornerstone. The operators of these generator stages were not JPUSA members or Cornerstone staff, although many of them had long friendships with Herrin and his staff. Cornerstone regulated these stages with permits, assigned locations, overseeing merchandise sales, and restricted operating hours. While some generator stages booked all of their bands in advance of the festival, others openly solicited performers at the festival. Bands would often arrive at Cornerstone as paying attendees, not yet having booked any performances, and quickly network with generator stage operators. Many bands played multiple generator stage concerts throughout the festival. Thirty-one generator stages registered for Cornerstone 2009, including the Face the Music (Figure 3), Fat Calf (Figure 1, #31), Indie Community (#34), and Rockstock (#30) Stages.

Figure 3. Face the Music generator stage at Cornerstone Festival 2009, photograph by the author.

The generator stages were a popular component of Cornerstone during the years I attended. They were busy: you could spend all day at generator stage concerts without stepping foot inside an official festival venue. Walking through the festival the first time I attended, in 2009, I passed generator stage after generator stage. The sounds of so many generator stage performances overlapped, and I could hear a dozen different bands playing at once. The crowds ranged from a dozen to a hundred or more, though most were fewer than fifty listeners. Generator stages tended to host young bands trying to engage new fans: many band members offered to hang out after the performance, promoted other generator stage concerts later in the week, and gave away CDs. Later at Cornerstone, I heard artists reminisce about playing generator stages early in their careers before “graduating” to the festival's official stages after building their audience and attracting the organizers’ attention. If the Banff Centre provided a literal training program for aspiring opera professionals, as Colleen Renihan describes in this issue of JSAM, then Cornerstone's generator stages, too, enabled young bands to hone their craft on festival grounds performing for paying attendees.

One way to analyze the generator stages is as a form of charity that JPUSA, through Cornerstone, granted to musicians and promoters who otherwise would not have had access to the festival's crowds. As Herrin explained, “You do your own thing, all we provide is a plot of ground, this is not a money thing. No exchanging money, don't charge the bands, the bands don't pay to play.”Footnote 31 Considering the generator stages as a form of charity aligns them with other aspects of JPUSA's mission, which includes caring for others outside of the community (through the homeless shelter they operate, also named Cornerstone), opening their home (a large apartment building in Chicago's Uptown neighborhood) to performances, and also empowering members’ entrepreneurship within particular parameters (JPUSA has supported many members’ start-up businesses and creative projects).Footnote 32

But if we instead analyze Cornerstone as a music scene, it is clear that generator stages play integral roles. For example, the relationships between generator stages and official venues at Cornerstone were similar to those between smaller and larger venues in other scenes: smaller venues may be more willing to book newer or younger artists; as artists gain more fans they perform in progressively larger venues. Sometimes touring artists will precede or follow large arena concerts with “secret” performances at smaller venues; in a similar manner, at Cornerstone bands may play a smaller generator stage concert before or after a higher-profile performance at an official stage. Also, generator stages expanded the event's overall diversity, ceded a degree of control to attendees, and actively encouraged and empowered amateur, semi-professional, and professional participation in the scene by maintaining a relatively low entry cost to access Cornerstone's attendees (and potential new fans). Generator stages, which were relatively unique to Cornerstone in contrast to the heavily planned and regulated performances at most other music festivals, added another layer to the event's sociality and spatiality. While it certainly would have been a scene without them, as decentralized components of the festival the generator stages contributed to the event's overall identity as a place that valued the contributions of as many participants as possible. In contrast to the observations about festivals by Dowd et al., Cornerstone's generator stages demonstrated that Herrin and his staff were not interested in fully defining their scene's boundaries but were instead open to the contributions of others. In this way, not only did Cornerstone create change beyond its own borders, but it was changed from beyond its own borders. In many scenes, participants’ roles blur the divisions between artists, cultural intermediators, and audience members; this was also true at Cornerstone, where many bands stayed throughout the festival as fans, staff, and volunteers oscillated between work shifts and free time to attend concerts and seminars, and where generator stages exemplified Herrin's interest in keeping the festival relevant to its attendees. Interdependence is a defining feature of many other music scenes, too, but the interdependence I witnessed at Cornerstone was enacted more intentionally and more thoroughly than at other music festivals, thus aligning it more closely with other music scenes.

As I have described in this article, festivals like Cornerstone construct a geographic infrastructure that largely mirrors what Kruse, Shank, and others have described in local scenes: a mix of private, semi-public, and public spaces that enable geographically dispersed participants to participate in real-life musical events for a few days every year, even if they cannot (or do not) participate in a local scene outside of the event. At festivals, these places are physically impermanent by design, and this ephemerality problematizes claims that these events are equivalent to traditional scenes. Yet the fact that they re-emerge and rebuild in the same location at the same time, year after year, cements them as permanent features in participants’ lives. Festivals are not permanent in the way that a physical music venue is, but neither are they strictly temporary or fleeting experiences. For long-time, regular Cornerstone attendees, the festival became an annual ritual where they resumed their friendships with their Cornerstone family, saw concerts they could not attend closer to home, and encountered new musicians and scene friends every year. Even the preparations, road trips, camp showers, porta-potties, and unpredictable weather became familiar, routinized, and tolerated, if not necessarily enjoyed. Herrin described the festival as an “annual renewal” for these attendees; they left Cornerstone refreshed in their faith, drawing upon their memories and anticipations of the summer to sustain them through other periods during the year when they felt the lack of a “like-minded” community particularly acutely. Outside of the festival's temporal period, Cornerstone's remembered and expected presence permitted participants to imagine themselves as part of a larger community of Cornerstone attendees whom they did not normally expect to encounter in daily life. For festival staff and JPUSA members, Cornerstone's workplace enabled them to articulate, celebrate, and embody their ideals of artistic creativity, family and community, and interdependence in a concentrated environment and intensified time period separate from other ritual events on the Christian liturgical calendar. The festival's official programming secured its reputation as a respected space of assembly and mediation, but to many attendees its generator stages embodied its identity as a collectivity and ethical world.

Cornerstone was ultimately a victim of its own success. As the genres that Herrin and his staff prioritized became increasingly popular, more and more festivals (both new and old) booked Cornerstone bands. Artists and fans thus had more choices when planning their summers. Many attendees chose to go to festivals closer to their homes instead of traveling long distances to western Illinois for Cornerstone. As the audiences shrank, bands saw Cornerstone as less relevant to their careers and increasingly booked longer tours and more festivals, both in the Christian market and at secular events and venues. If festivals are institutions with co-dependent artistic, financial, and social components, as Katherine Brucher argues in this issue of JSAM, then the relative instability of Cornerstone's finances was bound to impact its other elements negatively. In part to minimize the financial impact of declining audiences and maximize the event's remaining resources, in 2010 Herrin decided to move Main Stage from its traditional location (see Figure 1) to a more centrally-located place (the grounds’ former Midway). The audience's negative response was unsurprising and underscored how significant the festival's physical site was to attendees’ experiences. As intense, artificially bounded scenes, Cornerstone and other music festivals complicate our understanding of scenes. Festivals provide active sites for the performance not only of music but also of musical identities. Their infrastructures are designed and built intentionally, providing the geographic frameworks that scenes require. Their social networks are informed and influenced by values and practices present in the daily lives of all participants, including those of their organizers. They are ephemeral and annual; physically present for only a short period but anticipated online and relived in participants’ memories and photographs. The products of Cornerstone's unique sociality and spatiality continue to echo and reverberate in the lives of its attendees, many years after its gates closed for good.