“Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” has mysterious beginnings. No composer has ever been identified, and the dates of either composition or initial collection of this famous sorrow song elude discovery. Anonymity and vague origins are not unusual for spirituals, but despite its legacy, “Motherless Child” is conspicuously absent from the documented history of spirituals until almost the turn of the twentieth century. The tune does not appear in the earliest collections of spirituals,Footnote 1 and whereas the Fisk Jubilee Singers brought the spiritual as a genre and any number of popular Negro spirituals to the public's attention in the 1870s, “Motherless Child” does not seem to have been part of their repertoire.

However, the song's history is wrapped up in the legacy of another performing group: the Hampton Students, an ensemble at Hampton InstituteFootnote 2 (in Virginia's Tidewater region) modeled after the Fisk Jubilee Singers. It is through this performing group and prominent figures associated with Hampton that “Motherless Child” achieved lasting renown. “Motherless Child's” inclusion in the 1901 edition of Cabin and Plantation Songs as Sung by the Hampton Students solidified its place in the growing canon of spirituals. The tune remained in Hampton Institute's repertoire through subsequent printings of Cabin and Plantation Songs (later published under the title Religious Folk-Songs of the Negro as Sung on the Plantations) and entered the art music world soon thereafter in settings by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Harry T. Burleigh, and Clarence Cameron White, among others. However, even as the tune journeyed away from Hampton, it remained tightly bound to composers, performers, and choir directors affiliated with or connected to the historically black institution of higher learning, founded in 1868 and now known as Hampton University.

The story of “Motherless Child's” entrance into Hampton's repertoire around the turn of the twentieth century, its move beyond Hampton, and its later return is the story of the complex racial, cultural, and geographical relationships that have characterized the Institute's history. The telling of this story reveals a networked cast of characters, all invested in the health and growth of African American music in the early twentieth century, crossing paths in Tennessee, Mississippi, Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut, London, and of course, Virginia.

Early Versions

The 1901 edition of Cabin and Plantation Songs in which “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” first appears was published under the aegis of Ms. Bessie Cleaveland, who led Hampton's choir from 1892 to 1903.Footnote 3 Several editions of Cabin and Plantation Songs had already been printed. To this impressive collection Cleaveland added more than forty new songs. New tunes made their way into the Cabin and Plantation Songs collection via the singers themselves, who collected songs from their elders and communities and brought them back to Hampton.Footnote 4 The introduction to the 1891 edition explains this process:

Ever since the publication of the first edition in 1874, when the band of Hampton Student Singers were helping to raise the walls of Virginia Hall by its concerts in the North, there have been frequent requests for their music. Meanwhile, though the old favorites have not been neglected, many more melodies, striking and beautiful, have been brought in by students from various parts of the South. The field seems almost inexhaustible. Their origin no one knows.Footnote 5

One might logically conclude that a Hampton student brought “Motherless Child” to Cleaveland's attention. At this point in Hampton's history, plantation songs were primarily sung during Sunday evening chapel times. These were informal worship sessions; no records exist of the tunes sung each week. Students could have brought new tunes with them to introduce to the rest of the student body, and Ms. Cleaveland could have learned the tune in that fashion. However, several factors suggest that this process may not be how “Motherless Child” entered Hampton's repertoire.

Contemporary accounts of chapel singing describe four- to eight-part improvised harmonies. Ethnologist Natalie Curtis Burlin recalled such singing in a 1919 essay published in Musical Quarterly:

These nine hundred boys and girls at Hampton whose chorus singing is so “marvelous” are not divided and seated according to “parts” like the usual white chorus: indeed, technically speaking, this is no “chorus” at all,—only a group of students at the Hampton Institute who sing because music is a part of their very souls. And so in chapel, where the old “plantations” are sung, the boys sit together at the sides, and the girls sit together in the middle, each singing any part that happens to lie easily within the range of his or her voice, harmonizing the slave-songs as they sing. A first alto may be wedged between two sopranos with a second alto directly in front of her. A boy singing high tenor may have a second tenor on one side of him and a second bass on the other. But the wonderful inspirational singing of this great choir is sustained without a flaw or single deviation in pitch through song after song, absolutely without accompaniment.Footnote 6

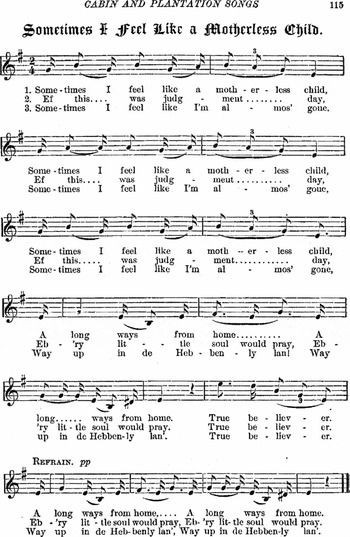

Therefore, one might expect the arrangements in Cabin and Plantation Songs to visually represent the multipart harmony of chapel singing, and indeed, the vast majority of tunes in the collection are set in four-part harmony, consistent with Burlin's performance descriptions. Cleaveland's arrangement of “Motherless Child” is, however, monophonic (Figure 1), marking it as relatively unusual for this collection. Whereas numerous songs in this edition of Cabin and Plantation Songs (including “The Downward Road Is Crowded” and “Ride On”) begin in unison and move to octaves in the choral sections, only five plantation songs are set monophonically, representing slightly more than four percent of the spirituals in this collection.Footnote 7 Furthermore, emphasis on multipart harmonic settings in this collection was not specific to Cleaveland's edition. In the first edition of Cabin and Plantation Songs, Thomas Fenner (Hampton's first choir director) had identified two primary means of legitimate treatment of spirituals: leaving them in a state of “rude simplicity” or developing the spirituals with harmony without destroying their “original characteristics.”Footnote 8 Nevertheless, his collection, first printed in 1874, turns far more often to multipart harmony than to monophony, an imbalance that continued long into the twentieth century and later printings of the Hampton songs.

Figure 1. “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” as printed in Cabin and Plantation Songs as Sung by the Hampton Students, 3rd. ed. (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1901).

In short, the 1901 setting of “Motherless Child” is inconsistent with both contemporaneous singing practice at Hampton and with comparable publications in the Hampton collections.Footnote 9 It is certainly possible that a student collector with limited musical training transcribed only a single melodic line, but Cleaveland surely had the ability to harmonize a new tune. For reasons unknown, she chose not to. A different collection scenario for “Motherless Child” thus seems more likely: that Cleaveland either heard a monophonic version elsewhere or used another version—already in print—as her source.

In fact, Cleaveland's publication of “Motherless Child” was not the song's first appearance in print. In 1899 it was printed twice by the Reverend William Eleazar Barton (1861–1930), a noted theologian and Abraham Lincoln scholar.Footnote 10 In the late 1890s, Barton published recollections of his time as a circuit-riding minister in the South in a series of three essays (“Old Plantation Hymns,” “Hymns of the Slave and the Freedman,” and “Recent Negro Melodies”) published in New England Magazine.Footnote 11 In the same year he bound the three essays together as a book under the title Old Plantation Hymns.Footnote 12 The second of these essays, “Hymns of the Slave and the Freedman,” contains the earliest known description and transcription of “Motherless Child.” Unfortunately for historians, Barton is not clear about the origins of the songs he collected. In the first essay he mentions a collection of songs particular to the Cumberland Mountain region in northern Tennessee, where he and his wife lived in the mid-1880s, and he also writes of Alabama. Most of his geographic references, however, are to a vague “South,” frustrating any attempt to identify a clear origin point for these tunes.

Barton draws upon the power of informants, “older people who knew old songs.” He transcribed songs as he listened, often asking his subjects to sing a particular tune over and over again until he could fix the tune to paper.Footnote 13 He identifies his informants by name: Aunt Dinah, for example, and Sister Bemaugh, who introduced him to “Motherless Child,” which he described as “one of the most pathetic songs I ever heard.”Footnote 14 Given that this is the first printed instance of “Motherless Child,” Barton's recollection is presented here at length:

Not very long ago I attended a concert given by a troupe of Jubilee singers, whose leader was a member of the original Fisk company. Toward the end of the programme he announced that a recently arrived singer in his troupe from Mississippi had brought a song that her grandparents sang in slave times, which he counted the saddest and most beautiful of the songs of slavery. It was a mutilated version of Aunt Dinah's song; and it lacked the climax of the hymn as I have it, —the “Gi’ down on my knees and pray, PRAY!” The swell on these words is indescribable. Its effect is almost physical. From the utter dejection of the first part it rises with a sustained, clear faith. It expresses more than the sorrows of slavery; it also has the deep religious nature of the slave, and the consolation afforded him in faith and prayer.Footnote 15

In other words, Barton claims to have had two sources for this song: the first, his local informants, presumably in northern Tennessee or southern Kentucky where he lived between 1885 and 1887; and the second, a different version of the tune (reportedly collected in Mississippi) by a troupe of Jubilee singers loosely affiliated with Fisk, performed perhaps sometime in the 1890s as he prepared the manuscript for his book.Footnote 16

Barton's transcription of the version he heard from Aunt Dinah is simple, monophonic, and repetitive. He includes four verses of text and is careful to render the text in dialect (Figure 2). Barton's description of the Fisk performance as a “mutilated version of Aunt Dinah's song” is significant: Aunt Dinah's version differs dramatically from every subsequent published version of the song. Whereas all other early published versions of this tune are in duple meter, Barton renders her song in triple meter, moving to 4/4 for the “Git down on my knees and pray” phrases, phrases that are unique to this version. He sets the tune in F mixolydian, the only modal setting of this tune in early printings. Much of the text, too, is idiomatic only to Barton's version: The second half of each verse (“O, I wonder where my mother's done gone,” etc.) has no equivalent in other versions. Barton's adherence to rough-hewn language set in a modal scale with shifting, unstable meters all collectively suggest that his transcription represents a version particular to the area where he worked in the mid-1880s: the Cumberland mountain region of northern Tennessee and southern Kentucky.Footnote 17

Figure 2. “Motherless Child” as transcribed by William E. Barton in Old Plantation Hymns: A Collection of Hitherto Unpublished Melodies of the Slave and the Freedman, with Historical and Descriptive Notes (Boston: Lamson, Wolffe and Company, 1899).

How, then, did Bessie Cleaveland learn “Motherless Child”? Unfortunately, very little documentation is available on the lives of Hampton's many teachers. This is particularly true for Hampton's female teachers.Footnote 18 Cleaveland's biography is largely undocumented, but her obituary identifies Danvers, Massachusetts—a small town approximately twenty-seven miles northeast of Boston—as the city of her death and place of residence for the final thirty-seven years of her life.Footnote 19 Genealogy records locate her place of birth (and that of her five siblings) in Boxford, located in Essex County, Massachusetts, about nine miles from Danvers.Footnote 20 By the time of the 1910 U.S. census, Cleaveland was back with her family in Essex County: She is listed in residence with her mother (as head of household), two sisters, a sister-in-law, and a hired man.Footnote 21 Moreover, one of her elder sisters died in Hampton in 1902 while Cleaveland was still overseeing Hampton's choir. In light of Cleaveland's strong family connection to Essex County, Massachusetts, it is reasonable to extrapolate that Cleaveland may have visited her family during school vacations, a typical practice for northern-born teachers. Given that William E. Barton lived in Boston from 1893 to 1902 and reports a Jubilee choir performance of this tune sometime prior to his publication in 1899, the performance he heard may very well have taken place in the Boston area in the mid-1890s.Footnote 22 Perhaps Cleaveland—home on vacation—also learned this tune from the same performance and published what she heard, rather than being influenced by Barton's 1899 publication, which differs so dramatically from her own. In other words, the version of “Motherless Child” that Cleaveland printed in 1901 may well be the “mutilated” version from Mississippi to which Barton refers.

Ultimately, how Barton and Cleaveland may have heard this tune still remains a mystery; the full extent of spin-off Jubilee choirs has yet to be documented. What is certain is that Cleaveland's published version seems to be the inspiration for later choral and art music arrangements of this tune. For many decades thereafter, the song's history weaves around and through Hampton's history.

Atlantic Exchange: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's Visits to America

“Motherless Child's” next print appearance is dramatically different yet again, and its historical circumstances both deepen the mystery of its transmission and speak to the larger context of the spiritual's move out of the folk realm and into the art music realm. In 1905 the Afro-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor published piano variations on numerous Negro and Creole melodies, including “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child.”Footnote 23 Because Coleridge-Taylor was British, and not American, his very familiarity with the tune (and other spirituals) needs explanation. A protégé of Edward Elgar, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912) garnered national attention in his native England with the performance of his choral work Hiawatha's Wedding Feast in 1898.Footnote 24 His resultant quick rise to fame inspired him to compose two additional movements; together these three choral movements became known as his Hiawatha Trilogy. Success in the United States quickly followed. Hiawatha made its American debut in Brooklyn as early as 23 March 1899, and a string of performances in the Northeast, Midwest, and as far south as Nashville followed.Footnote 25 Coleridge-Taylor also associated with American artists in London. He had given a joint recital with poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar in 1897, and in 1899 he met and began a deep and lasting friendship with Frederick Loudin, director of the Fisk Jubilee troupe then touring throughout London.Footnote 26

Coleridge-Taylor's biographer Ellsworth Jannifer counts this latter relationship as a key moment in the composer's developing awareness of spirituals, a claim Coleridge-Taylor makes himself in the foreword to his Negro Melodies Transcribed for the Piano (published in 1905 by Oliver Ditson).Footnote 27 Acknowledging influences for his knowledge of African music, Coleridge-Taylor ends his foreword by eulogizing Loudin, who had died in 1903: “Nor must I forget the late world-renowned and deeply lamented Frederick F. Loudin, manager of the famous Fisk Jubilee Singers, through whom I first learned to appreciate the beautiful folk-music of my race, and who did so much to make it known the world over.”Footnote 28 Given that this collection contains “Motherless Child,” it stands to reason that Coleridge-Taylor may have learned the song from Fisk (if the tune was, indeed, part of Fisk's repertoire). But various events between 1899 and the publication of Negro Melodies in 1905 complicate this potentiality.

Coleridge-Taylor's meteoric rise to fame caught the attention of African Americans who recognized the symbolic value the Afro-British composer could have in an America so divided by race. In 1901 a small group of African American intellectuals—led by Mrs. A. F. Hilyer, who had been introduced to Coleridge-Taylor in London by Loudin—formed a choral society in Washington, D.C., dedicated to the performance of Coleridge-Taylor's music.Footnote 29 The founding members committed to the society only after they had invited Coleridge-Taylor to Washington for performances of his music and received affirmation that he would come. The group incorporated in 1903 and performed his Trilogy on 23 April of that year in preparation for the composer's visit. Harry T. Burleigh, friend and associate of Antonín Dvořák and rising composer in his own right, distinguished himself as the baritone soloist in the choral society's performance.Footnote 30 Coleridge-Taylor's much anticipated visit to Washington was brief but eventful. He arrived in early November 1904, conducted three performances of his Trilogy, and then moved on to a handful of other cities before returning to London.

Members of the Hampton community could certainly have been aware of Coleridge-Taylor's visit if only because of a review of the choral society's 1903 Trilogy performance published in Hampton's long-established periodical Southern Workman.Footnote 31 The review, written by former Hampton teacher and Washington socialite Frances E. Chickering, not only describes the performance, but also offers a biographical sketch of the composer and information about the choral society.Footnote 32 Chickering ends her luminous review with the following comment: “It is interesting to know that the S. Coleridge-Taylor Society was formed under the stimulus of a proposed visit to this country of the composer himself.”Footnote 33 Hamptonians who kept up with Southern Workman were thus served notice of the composer's impending visit.

A brief review in Southern Workman just after the composer's visit to Washington lauded the choral society's success under the composer's direction and made special mention of Coleridge-Taylor's interest in both Negro and Indian musics. For an Afro-British composer, both musical traditions were foreign, yet the reviewer (perhaps Chickering again) found his approach sympathetic and appropriate:

It is interesting that the son of a native African should have obtained so high a position in the musical world as to be chosen leader of the largest choral society of London, his home, but there is peculiar interest attached to his . . . sympathy with the pathos of the Indian tragedy which he interprets so well in his “Hiawatha.” In his other compositions he shows a warm sympathy with the people of his own race, though he has had as little personal contact with them as with the more alien people.Footnote 34

The review ends with a wish that highlights Hampton's long interest in both Native American and African American musical traditions: “It is hoped that [Coleridge-Taylor] will visit Hampton in December and here meet the two races he has already interpreted so well.”Footnote 35 If such a visit took place, no records remain to mark the occasion.Footnote 36

Chickering provided a more thorough review of the two 1904 Coleridge-Taylor concerts in January of the following year.Footnote 37 The first evening featured another performance (the Choral Society's third) of the Hiawatha Trilogy, this time conducted by the composer himself. The second evening presented new music (much of it again by Coleridge-Taylor) including “choral ballads on Negro slavery” and settings of poems by Walt Whitman and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Baritone Harry T. Burleigh and violinist Clarence Cameron White, who both had connections to Coleridge-Taylor, performed. Overall, Chickering counted the concerts (which she reports filled the 3,500-seat hall) a huge success for all involved, despite a national aura of racial tension. She finishes her review with the following plea: “It is hoped that [Coleridge-Taylor's] memories of his first visit to Washington will be so pleasant that he will brave the dangers of the deep again in a not too remote future.”Footnote 38

Clearly Coleridge-Taylor's visit inspired the next generation of African American composers. But as Jannifer points out, his presence in Washington also had the effect of bringing American racial prejudice into national conversation. In late November 1904, just two weeks after Coleridge-Taylor's concerts, an unidentified editor at the New York Times tried to square Coleridge-Taylor's obvious gifts with America's halting progress in race relations.Footnote 39 The beginnings of the S. Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society are recounted here again, as are the circumstances of their performances under Coleridge-Taylor's baton earlier that month. But the editorialist—clearly sympathetic to African American concerns—takes care to frame these concerts and their public reception within a racialized context, notably by praising the “Negro” musicians and demeaning the white musicians:

What happened was rather curious for students of the many-sided and yet hitherto one-sided thing known as “the race problem.” These colored people, by common consent and common admission, managed the Coleridge-Taylor festival better than anything in the musical line has been managed in Washington for years. The musical critics of the Washington papers, mostly Southerners, conceded that the chorus of negroes was one of the best managed, best drilled, and most successful choruses that had ever appeared in Washington. The one weak point in the performance, according to the critics, was the orchestra. And the orchestra, alone of the component parts of the festival, was made up of white men.Footnote 40

Coleridge-Taylor's demeanor (“stiffly, calmly English,” “gentle”) and physical appearance (“light complexioned,” “small, delicate featured”) further complicated expectations of a Negro composer: To many observers in the United States he appeared neither exceedingly African in physical features, nor American in gestures. Indeed, the editorialist positions Coleridge-Taylor as the very antithesis of racialized American expectations: “If he had designed himself as the stumbling block and staggerer for the know-it-all judges of ‘the race problem,’ he would not have made his own character and appearance any different.”Footnote 41

Coleridge-Taylor returned to London in late November 1904. Perhaps inspired by both his previous association with Loudin and the Fisk Jubilee troupe and his time in America, Coleridge-Taylor published his collection Negro Melodies Transcribed for the Piano early the next year. American reviewers quickly brought this widely anticipated publication to the public's attention, but in general seemed perplexed by the collection. The New York Times offered a sympathetic but rather tepid review: “He has produced many effective pieces [through theme and variation technique], and displayed ingenuity and fertility of invention, but he does not seem to have been really inspired by his subject and, while we feel the skill and sincerity of the music, it is not often that there is the truly creative and enkindling touch.”Footnote 42 The review nevertheless places him in the company of highly regarded “art” music composers, making clear the seriousness of this collection: This is art music, created from the building blocks of various folk musics. Chickering's review of the collection for Southern Workman is more generous, but she, too, marks the uniqueness of this collection:

It is interesting that this able Negro musician should seek in this way to popularize and make permanent the folk music of his people. Though it hardly seems on first thought that variations on “Steal Away” and “My Lord Delivered Daniel” would add anything to the sweetness and pathos of these plantation melodies, and although primitive music does not appear to lend itself to elaborate settings, it is nevertheless true that composers are constantly finding inspiration for their greatest works in the fragments of just such music.Footnote 43

Settings of folk music were certainly known to American critics, particularly after Dvořák's tenure in America, but reviewers clearly struggled with this sort of setting for African American folk tunes, even though the results were deemed beautiful and inventive. Perhaps anticipating resistance to his approach, Coleridge-Taylor emphasizes in his preface to the collection that his versions of the spirituals are not mere arrangements: “[The Negro melodies] have been amplified, harmonized and altered in other respects to suit the purpose of the book.”Footnote 44 He justifies his reworkings of the tunes by arguing “however beautiful the actual melodies are in themselves, there can be no doubt that much of their value is lost on account of their extreme brevity and unsuitability for the ordinary amateur.”Footnote 45 His collection seems to be one part uplift and one part preservation.

“Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” appears near the end of this collection (no. 22 of 24). Above the arrangement, Coleridge-Taylor provides the monophonic tune (see Example 1). No publication source for the monophonic tune is given, but the setting itself suggests that Coleridge-Taylor likely used Hampton's 1901 published version as his source material.Footnote 46 He retains the home key of E minor, the 2/4 meter, and characteristic “motherless” triplet figure, all identical to Hampton's 1901 version, and all far removed from Barton's 1899 imprints. The arrangement includes three variations of the tune, each of a different character and linked by modulatory interludes. He moves the tune up through the registers, beginning with a middle voice in tenor range (beginning on g), another setting in a middle voice of alto range (beginning on g’), and a final setting in dramatic block chords set around octave Gs in the treble clef. Coleridge-Taylor essentially realizes in print what Hampton students had been doing extemporaneously for years: weaving a fantasy of harmony around a fixed tune.

Example 1. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” from Twenty-Four Negro Melodies Transcribed for the Piano (Bryn Mawr, PA: Oliver Ditson, 1905).

Coleridge-Taylor returned to the United States in 1906 for an extended tour that commenced in New York City's Mendelssohn Hall on 16 November and continued on to Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit, Toronto, Philadelphia, Boston, and Washington.Footnote 47 Most of these concerts featured the composer's chamber works and songs. Burleigh sang again, this time to the composer's accompaniment.Footnote 48 Coleridge-Taylor also performed a handful of tunes from his newest publication, Negro Melodies, including at least one performance of “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child.”Footnote 49 It is impossible to determine who and how many people heard his setting in these venues, but by the end of his 1906 tour, Coleridge-Taylor had contributed two strands to “Motherless Child's” history: an art-music arrangement for piano and public memory of him playing his arrangement.

The impact of Coleridge-Taylor's 1904 and 1906 visits to America cannot be overemphasized. As Jannifer argues,

Coleridge-Taylor helped break down long standing racial barriers with regards to the acceptance of Negroes as composers and performers of serious music by white Americans. Also, the unqualified acceptance and success of his music in this country opened the way for Negro Americans, such as Harry T. Burleigh, Clarence Cameron White, and Robert Nathaniel Dett, to make their mark as composers in the years following World War I.Footnote 50

Coleridge-Taylor provided a model for African American composers to succeed in art music. Further, he inspired an entire generation of African American composers to turn their own folk music—spirituals—into art music. Significantly, all three composers Jannifer mentions above would later set “Motherless Child.” Coleridge-Taylor's setting (clearly related to, if not drawn directly from Hampton's 1901 songbook) establishes the canonic version of the melody that art music composers—many of whom were in some way affiliated with Hampton—would later follow when setting this song.

Back to Hampton

A new edition of Hampton's songbook appeared in 1909, this time with an updated title: Religious Folk Songs of the Negro: As Sung on the Plantations. Hampton's choir was then under the leadership of Ms. Bessie L. Drew (1876–1934), who had taken over in 1904 after Bessie Cleaveland's departure and led the choir until the arrival of R. Nathaniel Dett in 1913.Footnote 51 A new introduction appears before this edition's first tune, written by Major Robert R. Moton, Commandant of Hampton Institute and a key member of Hampton's plantation song community.

Robert Russa Moton was himself a graduate of Hampton (class of 1890) and went on to become the second president of Tuskegee Institute, taking over after Booker T. Washington's death in 1915. Major Moton was apparently a tenor of some skill. During Drew's tenure as director, Moton concertized with Drew and participated in the Glee Club, singing the lead tenor solo parts.Footnote 52 Most importantly, Moton was deeply tied to the tradition of spiritual singing at Hampton, as he explains in his introduction: “For nearly a score of years I have led the plantation songs at Hampton Institute, and while in a general way we adhere to the music as notated in this book, we find that the best results are usually obtained by allowing the students, after they have once caught the air, to sing as seems to them most easy and natural.”Footnote 53 Even as late as this printing, students extemporaneously embellished the songs and were encouraged to do so as the spirit moved them.

This 1909 edition includes twenty-five new songs, freshly gathered from Fisk, Tuskegee, the Calhoun Colored School (in Calhoun, Alabama), and the Penn School (St. Helena Island, South Carolina).Footnote 54 “Motherless Child” retained its place in this edition. It does not appear to have been reengraved for either the 1909 or the subsequent 1916 edition: the typeface, rhythmic setting, key, indeed all musical and typographical elements, are unchanged between these editions. Although many new tunes—most set in harmony—made their way into Hampton's repertoire, “Motherless Child” retained its simple, monophonic essence well after the arrival in 1913 of R. Nathaniel Dett, the most celebrated of Hampton's musical directors.

R. Nathaniel Dett

R. Nathaniel Dett, director of music at Hampton from 1913 until 1931, nearly always takes center stage in narratives of Hampton's musical history. Under Dett the choir grew in size, fame, and repertoire, but Dett's vision of music at Hampton extended beyond the choir. As soon as he arrived, Dett began pushing for the establishment of a Music Trade School at Hampton. Prior to Dett's arrival, all Hampton graduates were assumed to have the necessary skills to teach music upon graduation: Music courses in vocal training and instrumental music were part of the basic curriculum.Footnote 55 Dett insisted, however, that not all students were sufficiently trained to be music teachers. In a 1914 report to Hampton President H. B. Frissell, Dett invoked Hampton's rhetoric of excellence to make his point:

Music is acknowledged as the most refining of the sciences; why not, then, enlist its ennobling influence in the Hampton idea of racial uplift? Would Hampton say that music is an art not worthy to be well done? Would Hampton say that her students are not worthy to do it well, when by their songs their fathers came from bondage to freedom? Why not, then, to the trades which are to make men more useful and better at music which, besides its contribution of utility, will make for greater happiness, greater refinement, and have a tendency to bind people together by the indisputable persuasion of its universal appeal. Why not a MUSIC TRADE SCHOOL, whose graduates shall be prepared to lead community choirs, teach music in the public schools, and play at the church services? Why not a MUSIC TRADE SCHOOL in which Negroes learn WHY their songs should be sung and preserved? The deplorable distaste on the part of so many Negroes for their own songs is not surprising, as it comes through ignorance.Footnote 56

Dett also points to Hampton's legacy of spiritual singing as a dubious success, arguing that students forget the songs after leaving Hampton because they lack sufficient training to keep the tradition alive:

One large reason why students lose interest in folk-songs when they leave the school where they are sung, and do not after leaving take a more active part in perpetuating them, is because they lack the courage of conviction which comes as a result of intelligent study. If the folk-songs were studied and taught with the same earnestness and intelligence that characterizes the learning of any other piece of music or literature, and their points of excellence shown by actual comparisons with the music of other races, the deeper appreciation thus established could not help but be permanently effective.Footnote 57

By the time of his 1919 annual report on the state of the music department, Dett had a new concern: that authentic singing of plantation songs was on the verge of being lost. Dett blamed the decline on the students’ increasing ambivalence about singing plantation melodies at Hampton. He was not the only observer to notice their lack of enthusiasm:

No end of criticisms have been heaped upon the music director's head whenever the plantation singing has failed to come up to what was felt to be the desired standard. As we have had no really satisfactory leader, since Dr. Moton's time, these times have been rather frequent and the criticism has increased proportionately. [Moton had moved to Tuskegee in 1915.] Yet every obstacle has been put in the way of my having anything to do with the Plantation Singing. In fact, I have never been allowed to direct it. In instances, with about five minutes warning, I have been called upon to lead the songs. These are about all the Hampton honors that I can claim in this direction. . . . [Plantation Singing] is something which, since lacking Dr. Moton's leadership, has gone on rather perfunctorily. . . . What I feel has been most lacking has been the spirit of the songs, without which the songs are but little. We have had leaders with good enough voices, in some instances, but lacking in spirit, they have failed to obtain the real results.Footnote 58

Clearly the lack of an experienced and fervent lead tenor had taken its toll on plantation singing at Hampton. Dett's prose suggests his willingness—but lack of availability or, perhaps, permission—to lead the singing, and frustration that this tradition was suffering. But Hampton's students passed on the blame for their lack of enthusiasm, pointing to constant pressure to sing under white gaze during the evening chapel hours. As Dett continued in his 1919 report, “There has been an increasing feeling on the part of the student body that the songs are sung merely for show, ‘because white people like them’.”Footnote 59

Dett advocated a twofold strategy to save these melodies. First, remove the songs from public gaze by letting the students choose where and when to sing them. Second, study this music as intensely as other repertoires, so that the students might gain an increased respect for the tradition they were about to lose. In Dett's words, “serious study of the Songs would create a greater respect for them, I believe. Whatever is worth doing is worth doing well.”Footnote 60

Dett applied his second strategy—serious study of the songs—to his own reworking of Religious Folk-Songs of the Negro, published in 1927, the year Hampton's School of Music was finally established.Footnote 61 The songs are now graced with expressive markings in Italian, clear tempo directions, and delicate dynamic shadings. Dett's version of “Motherless Child” (Figure 3), marked lento dolente and molto espressivo, is not so much an arrangement as it is a softening of the song's rustic edges, rendering invisible the song's oral traditions in favor of tuning in to its inherent artistic qualities. Hairpin dynamics shade the still-monophonic E minor tutti melody, giving way to a solo line (“True believer”) marked a piacere. If Hampton's ensemble sang from this score, they would indeed have needed intensive study to learn the written performance directives, missing from previous Hampton collections. But the melody itself is otherwise unchanged, preserving the spiritual in this new, serious setting, as was Dett's goal.Footnote 62

Figure 3. “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” as printed in Religious Folk-Songs of the Negro, ed. R. Nathaniel Dett (Hampton, VA: Hampton Institute Press, 1927). From the collections of the Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee State University.

Dett's stylized, updated version of Religious Folk-Songs of the Negro, though representative of Hampton's repertoire, is also a snapshot of contemporary trends. Increasingly throughout the 1920s, the spiritual as a genre would transcend from the folk sphere into the art sphere, aided both by additional arrangements and by the increasing popularity of sound recordings. Indeed, the first recording of “Motherless Child,” sung by Paul Robeson, had appeared in 1926, only a year before Dett's publication.

Spirituals as Art Songs

Several other published versions of “Motherless Child” appeared in the years between the 1916 edition of Hampton's songbook and Dett's 1927 version. Many of these arrangements were inspired by Coleridge-Taylor's artistic rendering of spirituals in his 1905 collection. The first, in 1917, was by none other than Harry T. Burleigh (1866–1949), the famous baritone who had performed Coleridge-Taylor's music during the latter's residence in the United States. Burleigh's arrangement of “Motherless Child” is all the more interesting given his connections to Dvořák, Coleridge-Taylor, and Hampton itself.Footnote 63

Burleigh was undoubtedly well known to the Hampton community, perhaps first through his concertizing with the Washington, D.C., Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society and then with Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. As discussed earlier, Chickering's reviews of the Coleridge-Taylor concerts in 1903 and 1904 singled Burleigh out for high praise.Footnote 64 Burleigh also visited Hampton's campus at least once. In May 1914, The Hampton Student excitedly reported an imminent recital by Burleigh.Footnote 65 The recital, held on 20 May 1914, was later reviewed in Southern Workman. Deemed “one of the most successful in years,” the recital included plantation songs, operatic selections, and Burleigh's own arrangements. The review especially praises Burleigh's own compositions: “in his rendition of his own arrangement of the Indian and Negro melodies, the artist carried his audience on the top wave of enthusiasm.”Footnote 66 The Hampton choir sang for Burleigh, too, presenting (among other numbers) Dett's famous choral anthem “Listen to the Lambs.”Footnote 67 Dett later programmed Burleigh's arrangements of spirituals: Throughout Dett's tenure as director Hampton's choir regularly performed Burleigh's “Deep River” and “Were You There.”

By 1911 Burleigh had secured a position as a music editor in New York with G. Ricordi, a position he held for nearly forty years.Footnote 68 Burleigh took advantage of his position, publishing several sets of songs with Ricordi in the late 1910s alone. His 1917 collection, Album of Negro Spirituals, was a watershed moment in the history of Negro spirituals. Until this publication, spirituals were typically sung by choirs or ensembles. Burleigh transformed these spirituals into art songs for solo voice and piano accompaniment, thus making them suitable for solo recitals.Footnote 69 Replete with Italian performance directions such as lamentoso, ben sostenuto, and a tempo, his arrangement of “Motherless Child” is built from only two verses, compared to three in the Hampton songbook (Example 2). Burleigh simply excised the middle verse—arguably the most awkward in terms of text setting, and least likely to sound graceful in an “art” music setting—from Hampton's version. His arrangement contains only slight nods to dialect: “motherless chile” instead of “motherless child,” and “almos'” rather than “almost.” Gone are the dramatic descending “true believer” sections, instead replaced by extra iterations of “a long ways from home.” He also smoothes out triplets from the original “in order to facilitate vocalization,”Footnote 70 resulting in a sped-up descending figure on “Motherless chile.” Burleigh preserves the song's melodic contour of previous publications, sustained by a piano accompaniment that takes the spotlight only between the verses.Footnote 71

Example 2. Harry T. Burleigh, “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” as printed in Album of Negro Spirituals (New York: G. Ricordi, 1917). Burleigh reset his arrangements to be suitable for different vocal ranges. His version of “Motherless Child” is available in F minor for low voice (1917) and A minor for high voice.

Purists dismissed the elegance of Burleigh's solo arrangements as inappropriate for folk music, but others insisted that such criticism missed the point.Footnote 72 Noted choral music composer Randall Thompson, for example, has called Burleigh's arrangements “a kind of idealized spiritual, a transformation of the melodies into art songs very much in the manner of the Brahms Deutsche Volkslieder.”Footnote 73 Perhaps a more appropriate comparison would be to the folk settings of Burleigh's mentor and friend, Antonín Dvořák. Burleigh himself admitted: “Under the inspiration of Dvořák, I became convinced that the spirituals were not meant for the colored people, but for all people.”Footnote 74 Burleigh's time with Dvořák in New York not only influenced his compositional style, but also likely opened Burleigh's eyes to another of America's musical riches, Native American melodies, which he also arranged. Given his association with Dvořák, Burleigh may have felt a special connection with Hampton, where Native American music and African American music were both celebrated.

Less than a decade after Burleigh's publication the brothers J. Rosamond Johnson and James Weldon Johnson published a version of “Motherless Child” in their famous collection The Book of American Negro Spirituals. The Johnson brothers followed in Burleigh's footsteps, treating the spiritual as art song. Writing in the 1925 introduction, J. Rosamond was clear about his debt to Burleigh: “Mr. Burleigh was the pioneer in making arrangements for the spirituals that widened their appeal and extended their use to singers and the general music public.”Footnote 75 Like Burleigh's settings, these are intended for solo voice and piano accompaniment: They are art songs, not choral chants. The Johnsons’ collection was immediately successful, and a second book was issued in the following year. “Motherless Child,” which they describe as “poignantly sad,” appears in the 1926 volume.Footnote 76

The Johnson brothers, too, had Hampton connections. From 1914 to 1919, J. Rosamond Johnson directed the Music School Settlement for Colored People in New York City. Musical dignitaries lectured and performed at this school, including celebrities such as Harry Burleigh, Clarence Cameron White, Emma Azalia Hackley, and the Hampton Quartet, all names that already were or would be associated with Hampton.Footnote 77 James Weldon Johnson, Executive Secretary of the NAACP from 1920 to 1930, visited Hampton at least once in order to give Hampton's 1923 commencement address. His speech, very much in keeping with the spirit of uplift, exhortation, and calls for race pride characteristic of the Harlem Renaissance, was later printed in Southern Workman.Footnote 78 Johnson took great care to mention Hampton's role in the preservation of spirituals in his address:

[The American Negro] has given to America her only great body of folklore and he has likewise given to her her only great body of folk music, that wonderful mass of music which will some day furnish material to Negro composers through which they will voice, not only the soul of their race, but the soul of America. I have always been glad of the fact that Hampton has made itself the home of that music, that here it has been nurtured and taught and spread.Footnote 79

By this date the Johnson brothers could easily have used a non-Hampton-affiliated print source for their rendition of “Motherless Child.” But given their respect for the preservation work at Hampton, it is not surprising that the Johnsons reached back to Hampton's versions for inspiration. As Example 3 reveals, they return the tune to the E minor key of Hampton's arrangements, restore the triplets of the “motherless child” phrase, and reinsert the “true believer” refrain between verses. There is far more repetition in their arrangement of “Motherless Child,” resulting in a loose, slowly unfolding, but almost static form. Indeed, Ann Sears points to uses of repetition as a key difference between arrangements by Burleigh and those of the Johnson brothers. Comparing their versions of “Deep River,” Sears notes that the repetition creates an aura of improvisation, returning the spiritual to its “original” form: “A recitalist would find a concert performance of that version challenging, because the repeated phrases serve a very different function in the improvisatory tradition, where repetition may pace a worker's task, assist spiritual concentration in a religious service, or give voice to a community's feelings. Burleigh uses repetition, too, but with a structured goal.”Footnote 80

Example 3. “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” as printed in The Book of American Negro Spirituals (New York: Viking, 1925; 1926; reprint, New York: Da Capo, 1977). Copyright © 2002 James Weldon Johnson, J. Rosamond Johnson. Reprinted by permission of Da Capo Press, a member of the Perseus Book Group. From the collections of the Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee State University.

The arrangements in The Book of American Negro Spirituals were quite popular, perhaps in part because of their closer connections with “authentic” spiritual singing practice. Yet this collection did not please all critics. Dett himself was quick to offer a review for Southern Workman. Allowing for the Johnson brothers’ obvious respect for their material (as outlined in detail in a lengthy preface), Dett nevertheless found problems, chiefly with harmonic considerations:

At first glance, . . . “The Book of American Negro Spirituals” is a perfect work and if a study of it went no further, one would be inclined to unconditional and enthusiastic praise. But if, as the Preface tells us, the singing of Negroes is nearly always in parts, then it seems a mistake not to have included in the volume at least a few spirituals locally harmonized; and one feels in trying over the songs that the use of jazz, the “Charleston,” and other dance-like motives in the accompaniment threatens seriously the spirit of nobility and dignity of which the Preface assures us.Footnote 81

Dett takes the Johnsons to task for not setting the tunes “authentically,” that is, in multipart harmony.Footnote 82 (Given his preference for settings in harmony, his monophonic rendering of “Motherless Child,” published the following year, is again noteworthy.) Dett also complains that the Johnsons renege on their promise not to change the songs, pointing out places in several songs that have clearly been manipulated.Footnote 83 Nevertheless, Dett does allow that this is a “valuable book, throwing light, as all such efforts must, on the present-day tendency of Negro thought and illustrating something of the progress of the race's artistic achievement.”Footnote 84 Despite Dett's reservations, it is to this version that later scholars would refer, time and time again. As Floyd notes, the Johnsons’ collection “to some degree superseded Burleigh's arrangements and may have become the primary source for spirituals in the Harlem Renaissance period.”Footnote 85

The rhetorical battle Dett waged with the Johnson brothers over their interpretation of spirituals was hardly an isolated incident. Dett here (and elsewhere) reveals some of the tensions typical of the Harlem Renaissance, a period during which binaries such as art versus folk, tradition versus innovation, atavism versus refinement, and separation versus assimilation were daily topics for African American intellectuals and those whites who supported the movement. Intellectuals variously embraced the spiritual as a “natural” birthright, as evidence of native intelligence, and as the music most representative of an entire “race.” W. E. B. DuBois, an elder in this movement, rhapsodized at length about this music's value long before the Harlem Renaissance began:

By fateful chance the Negro folk-song—the rhythmic cry of the slave—stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side of the seas. It has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.Footnote 86

Alain Locke, one of the most respected leaders of the movement, glorified spirituals as “really the most characteristic product of the race genius as yet in America.”Footnote 87 The Johnson brothers in turn called the spiritual “noble,” “majestic,” and “exalted.” They claim “never does their philosophy fall below the highest and purest motives of the heart” and “all the true spirituals possess dignity.”Footnote 88 Such statements are easy to find: Each intellectual offered an ever-more glorious opinion of the spiritual's worth, and all of these descriptors in turn celebrated the artistic legacy of a marginalized people. What was in disagreement, however, was the future of the spiritual, and the most appropriate means of preservation. For all of Dett's complaints about the loss of authentic singing practices at Hampton, he was nevertheless consistent that black music would only be useful and used if refined and uplifted. The practicality of Hampton's Normal curriculum (and that of other Normal schools) peeks from behind Dett's mantra: preserve and protect, but do so in a practical, useful manner.

(Almost) Back to Hampton

The Johnson brothers’ two-volume collection opened a floodgate of spiritual arrangements. Two arrangements of “Motherless Child” were published in 1927: one by Dett (discussed earlier) and the other by multitalented Clarence Cameron White (1880–1960), yet another composer with ties to Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Harry T. Burleigh, and Hampton.

A familiar cast of characters populated his life from an early age. At sixteen (1896), White began studying at Oberlin Conservatory. While at Oberlin, White began corresponding with Coleridge-Taylor, a connection made possible by Frederick Loudin.Footnote 89 White and his family visited Coleridge-Taylor in London during the summer of 1906, and when Coleridge-Taylor came to America later that year he invited White to join his 1906 tour. White and his family returned to England in 1908 and remained there until 1911.Footnote 90 White had also studied violin at the Hartford School in Connecticut and while in residence (in 1901 or 1902) made his first concert appearance; Harry T. Burleigh was also on this program.Footnote 91

After his return from England, White held various positions, including Director of Music at Hampton from 1932 to 1935. In 1927, while Director of Music at West Virginia State College, White published his own take on spirituals, printed under the title Forty Negro Spirituals.Footnote 92 Like the arrangements by Burleigh and the Johnson brothers, White's arrangement of “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Chile” is set for solo voice and piano (Figure 4). White's F-minor version grants the piano more independence, framing the song with Schumannesque prelude and interludes. White, too, limits his use of dialect to only a few, token words: “chile,” almos’,” and “moanin’.” Unlike Burleigh's version, White's arrangement gives extra emphasis to the “true believer” text, with two statements after each of his three verses. Notably, White adds a textual variant for the third verse not found in other contemporary arrangements: “Sometimes I feel like a moanin’ dove.” But even with new text, the same melodic contour is preserved, again in 2/4 time, and again replete with the characteristic “motherless child” triplets.

Figure 4. Clarence Cameron White, “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” from Forty Negro Spirituals Compiled and Arranged for Solo Voice (New York: Theodore Presser, 1927). From the collections of the Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee State University.

Artistic license aside, the textual differences among these “art” scores by Burleigh, the Johnsons, and White document the likelihood of a lively oral tradition for this song. Some of the textual elements are fixed—they all begin with the same text, are all set strophically, all include the “almost gone” verse, and are all built on trifold repetition of the first line of each verse. Other aspects are variable—additional verses in some, fewer in others, ambivalence about the “true believer” text, and varying song endings. Indeed, with the proliferation of sound recordings, multiple variants of “Motherless Child” came to public attention beginning in the late 1920s. As mentioned above, Paul Robeson's iconic recording of “Motherless Child” (arranged by Lawrence Brown) appeared in 1926.Footnote 93 An early blues version of this tune, performed by Piedmont blues guitarist Barbecue Bob, was recorded the following year.Footnote 94 Recordings produced under the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s document further variants.Footnote 95 Furthermore, gospel quartets, including the famous Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet, added their voices (and additional variants) to the song's recorded history throughout the 1930s and 1940s.Footnote 96 Burleigh's wish, that spirituals become music for all people, appears to have been realized in the age of mechanical reproduction.Footnote 97 Hampton's influence on the shape and structure of “Motherless Child” seems to wane in these decades as a new crop of performers, composers, and arrangers relied less on printed versions of the tune and more on recordings. Nevertheless, Hampton's legacy extends at least into the 1950s, if in somewhat unexpected ways.

The Glee Club Connection

In 1957 the director of the Yale Glee Club, Fenno Follansbee Heath, Jr. (1926–2008), published a new four-part arrangement of “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child.”Footnote 98 Heath arranged this tune for his own Glee Club, which he began directing in 1953 and led until 1992. Like many of his other arrangements for Yale, Heath's “Motherless Child” is for only male voices.Footnote 99 His simple, three-verse arrangement of “Motherless Child” begins with the standard first-verse text (“Sometimes I feel like a motherless child, a long ways from home) in unison (see Example 4). The second verse, in dramatic a cappella TTBB harmony, offers a textual variant: “Sometimes I feel like I've never been born,” while the third verse for tenor solo and background choral “oohs” returns to a familiar text: “Sometimes I feel like I'm almost gone,” ending with “a long ways from home.” Echoes of Hampton abound. Heath chooses E minor, retains the characteristic major third interval, and uses the first and third verses of Hampton's version, long since canonized as the two most popular verses. He does not include the “true believer” section of text or the refrain, instead choosing strophic variations, putting more emphasis on choral textural variety than on complex formal devices.

Example 4. Fenno Follansbee Heath, Jr., “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” from Yale Glee Club Series (1957). Music by Marshall Bartholomew. Arranged and edited by Fenno Heath. Copyright © 1934 (renewed) by G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP). International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

One could argue that Heath inherited this song from a choral tradition well established by the 1950s, or from a tradition of singing spirituals already established at Yale. Indeed, as Sandra Graham has documented, college glee clubs—Yale's among them—were singing spirituals and contrafacts of spirituals as early as the 1870s.Footnote 100 But the influence of Hampton is part of Heath's backstory, an example of what George Lipsitz has called “the long fetch of history.”Footnote 101 Fenno Heath was the son of another Fenno Heath, a draftsman, who taught drawing at Hampton Institute from 1913 until he enlisted in the army in 1918.Footnote 102 Upon his return to the United States, Heath resettled in Hampton, married former Hampton Institute teacher Dorothy Louise Jones, and took a job as a draftsman at Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock company where he remained until his retirement in 1958.Footnote 103

Fenno Jr. was raised in Hampton and, like his father, graduated from Newport News High School. He left Virginia to attend the Loomis School in Connecticut before matriculating to Yale, where he sang in the Glee Club then led by Dr. Marshall Bartholomew, whom Heath would later replace. Perhaps Fenno Jr. was familiar with spirituals as sung by the Hampton choir: Certainly his parents, both former Hampton teachers, must have known about the school's musical traditions. Perhaps he heard “Motherless Child” as a youth and brought the tune into his adulthood to arrange for his Glee Club at a later date.

But Yale and Hampton had deeper ties. In late 1933, Bartholomew wrote to Hampton regarding a possible visit of Yale's Glee Club to Hampton's campus. (Given that Hampton's president at this time, Dr. Arthur Howe, was a Yale alumnus, the contact between the two schools was perhaps predictable.) As plans for the April 1934 visit solidified, it became less of an exhibition of Yale's skills in a concert setting, and more of a shared musical experience between the two bodies of experienced singers. On 20 February 1934, Hampton's secretary, William Scoville, wrote to Bartholomew: “It was suggested by [Clarence Cameron] White [then director of Hampton's Music Department] that in one or two intermissions of your program the School as a body, might be called upon to sing plantation songs.”Footnote 104 Bartholomew's reply on 1 March was eager and generous: “The members of the club are very anxious to hear the Hampton students sing; in fact that is one of our big reasons for coming to Hampton, and so by all means we hope Mr. White's suggestion is adopted.”Footnote 105 In the end, a joint concert was arranged for 5 April 1934, each choir singing its specialties.Footnote 106

Whether or not Fenno Heath, an eight-year-old child at the time of this concert, attended this event, Yale's Glee Club—led by Bartholomew, who would later mentor Heath—heard spirituals sung at and by Hampton. Fenno Jr. inherited not only the deep traditions of Hampton's musical environment but also the rich legacy of Yale's Glee Club, itself in turn also influenced by Hampton. For this son of Hampton living “a long ways from home,” arranging a song sung for so long by Hampton must have felt like coming home.

Although “Motherless Child” enjoyed a healthy publication history in the 1920s and beyond, we must not forget that it also was heard in rural communities, in concert, over radio broadcasts, and on recordings. The differences among versions—and there are many—are certainly worthy of note, but what is more remarkable is the similarity of these arrangements as “Motherless Child” transformed from spiritual, to choral staple, to art song, and beyond. Even more remarkably, the song's transformation depends on a path through and around Hampton. Fisk has long been recognized as a key institution for both the preservation and performance of spirituals, and New York City has been given its due as a locus of intellectual, cultural, and artistic renaissance in the 1920s. But as the history of “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” reveals, Hampton Institute boasted a shifting roster of key intellectuals and cultural leaders. As early as the 1890s and well into the twentieth century, Hampton's musical directors were at the forefront of musical trends in the United States, tackling first the issue of the worth of Native American and African American musical traditions as source music for new compositions, and later providing leadership in preserving and protecting spirituals. In a July 1918 essay in Musical America about R. Nathaniel Dett and the future of black music, May Stanley quipped: “many are the roads which lead to Hampton these days and many people travel them.”Footnote 107 Stanley's words remind us of Hampton Institute's significance as a nexus of musical activities, a center of stimulating intellectual debate, and a repository of the spiritual tradition in the first half of the twentieth century.