In 2002 composer William Banfield issued a call to preserve and research the works of African American composers; in doing so, he explained, scholars, performers, and educators would be “expanding and gently challenging the institutional organizations and educational systems that perpetuate and inform American artistic culture.”Footnote 1 Although the work of African American composers has been documented by way of bibliographies and recordings, the volume of scholarship in this area is minute in comparison to the growing numbers of books and articles on black popular music; clearly, more is needed to answer Banfield's call.Footnote 2 Deeper engagement with the concert music of African American composers to analyze compositional structures and to discover how they express meaning is essential to this endeavor. Toward that end, I will explore issues of musical structure and expressivity in two works by David N. Baker (b. 1931): his Sonata for Cello and Piano (1973) and Sonata I for Piano (1969). That Baker utilizes elements of jazz and other vernacular music in these “formal” works is noteworthy, but how does he deploy them? In what ways do the vernacular emblems interact with structural elements and, perhaps, expectations inherent within Western conventions (and vice versa)? A variety of approaches and ideas will be called upon to address these questions. Historical and cultural considerations will be combined with conventional analytical methods and readings of referential symbols in the service of interpretations that address both the structural and expressive domains. This approach not only allows more comprehensive readings of Baker's work, but also offers a way to move beyond surface-level descriptions of black vernacular musical emblems in the concert music of African American composers more generally. I note here that the expressive domain in black music (in terms of musical tropes, signification, topoi, etc.) has been explored by other scholars; those studies will serve as points of departure for many ideas that will be addressed in this essay.Footnote 3

David N. Baker's compositional aesthetic demonstrates an allegiance to the African American vernacular, embracing the musical and cultural experiences of his life. A true eclectic, he combines disparate genres and styles ranging from work songs and jazz to concerti and sonatas with an expressive voice that is both progressive and historically aware. His various jazz encounters have shaped his compositional aesthetic, but he also counts Béla Bartók and Charles Ives among his primary influences, and blends a number of sources, ranging from spirituals to serialism, into a style that boasts European classical and American vernacular sensibilities. The expressive character of his music, however, grows from African American roots; Baker incorporates numerous cultural emblems and folk traditions into his works. Because of his dedication to African American musical traditions, themes of reverence and remembrance saturate Baker's compositional output. Works such as The Black Experience (1973), and Singers of Songs/Weavers of Dreams (1980) embody those themes.Footnote 4The Black Experience is a song cycle that sets texts from Mari Evans's collection, I Am A Black Woman (1970); one encounters in it a number of African American musical emblems such as blues forms, R&B grooves, and jazzy chordal constructs that “complement the attitudes expressed in the text, attitudes which help shape the ‘Black Renaissance’ at the turn of the twentieth century right up to 1971.”Footnote 5Singers of Songs/Weavers of Dreams (for cello and seventeen percussion instruments) pays tribute to influential African American musicians of the twentieth century—among them John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Sonny Rollins—through inventive portrayals of each one's distinctive qualities.Footnote 6 Baker describes the piece as an “homage to my friends.”Footnote 7

Baker's craft, particularly during the time he composed the piano and cello sonatas, reflected personal philosophies regarding cultural experience and its correlation with musical expression. In a mid-1970s interview recorded in The Black Composer Speaks, Baker explained:

I try not to let anything get between me and what I have to say. I use craft and all those things as a means of expressing what it is I feel about life. I think the fact that I work with all available forms (irrespective of genre, origin, etc.) and the fact that many of my works have been devoted to, dedicated to, and are about Black people says, I think, something about what I feel philosophically, politically, and socially about my music. . . . Essentially the role of any artist vis-à-vis his own ethnic background . . . is to somehow crystallize and project those things which are unique to his particular ethnic background to other people—to somehow or another take something very specific, like the things that form his life, and translate them into universal terms so that they then have some meaning to everybody.Footnote 8

Among Baker's prolific output, we find works and movements written for or dedicated to black historical figures and black music icons. In addition to those mentioned earlier, representative works include Black America: To the Memory of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1968), Ellingtones: Fantasy for Saxophone and Orchestra (1987), and “A Song-After Paul Lawrence Dunbar” from the Sonata I for Piano (1969). Baker has also written many works where such attributions are not readily apparent, yet which still draw inspiration from his heroes:

Even when I haven't been so consciously about the business of writing to a specific person, I think that one can trace elements even in just specific movements of my works. I've felt that very often a particular movement of a particular work was inspired primarily by what I feel about my heroes. I think my choice of materials is a reflection on what my personal philosophy is, the fact that I draw heavily on jazz components in my writing.Footnote 9

Baker's Sonata for Cello and Piano (1973) reflects this heroic inspiration. The sonata is in three movements. The outer movements, consisting of a lively first movement and a spirited finale, display the thematic and structural characteristics of sonata form along with traits from the African American vernacular. Between the outer movements is an expressive slow movement that reflects the core of Baker's homage aesthetic. No specific jazz hero is named and there are no spaces for improvising; however, Baker's “drawing” upon jazz is clearly present.Footnote 10 Throughout the sonata, one encounters jazz harmony, scales, and rhythmic patterns, and in the contemplative slow movement the composer's respect for a departed friend and jazz giant, John Coltrane, emanates with clarity.

Sonata for Cello and Piano (Second Movement)

In the liner notes to the Black Composer Series recording, Dominique-René de Lerma states that the second movement is “intentionally reminiscent of John Coltrane.”Footnote 11 The following analysis explores the melodic and harmonic details of the movement and how they might imply a connection to John Coltrane. In addition to demonstrating a general affinity to jazz in this movement, I draw attention to motifs and related tunes that suggest Coltrane's presence. The worlds of jazz and concert music continuously mix throughout. Extended harmonies and other characteristic jazz nuances merge with emblems of the Baroque era, such as the passages for unaccompanied cello (including an extensive cadenza) and contrapuntal episodes. Although Baker is stylistically deferential when referring to Baroque practice, a sense of play emerges from the strident jazz inflections. Certain contrapuntal episodes are treated with strict canonic writing, and the florid cadenza, complete with octatonic collections and blues gestures, leads to the dominant harmony that prepares the final statement of the main theme. Jazz saturates the fabric of the movement, but never overshadows the formal surface. This commingling of jazz and neo-Baroque styles suggests a synthesis that, I would argue, engages the concept of musical signifyin(g). Introduced by Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., musical signifyin(g) is an extension of literary theories developed by Henry Louis Gates. Floyd defines musical signifyin(g) as “troping: the transformation of preexisting musical material by trifling with it, teasing it, or censuring it.”Footnote 12 The notion of creative play on or with established styles, emblems, and gestures is at the core of this concept, and Floyd suggests that effective critiques and interpretations of African American music should meaningfully engage with both the signifier and the signified. In other words, in the case of this movement, one should be fairly acquainted with both Baroque and jazz, or perhaps Bach and Coltrane.

Viewing the pianist and cellist as characters in this field of play orients the movement as a whole, as Baker's signifyin(g) posture features a constant juxtaposition of jazz and Western voices. Within the ternary design, Baker allows each player to express multiple voices, creating a complex dialogue. (Table 1 outlines the movement's form.) Throughout the movement both players take on jazz and Baroque styles by way of distinctive symbols and musical textures, but by the end the players present the main theme together as if their differences were resolved. The A section opens with unaccompanied cello (mm. 1–21), whose polyphonic melody and quasi-gavotte rhythm immediately identify the Baroque voice. Even though Baker evokes the genre of Bach's unaccompanied cello suites, certain rhythmic and harmonic elements of jazz pervade the texture. The systematic incorporation of chromaticism and various other jazz elements slowly move the cello from the eighteenth century to the twentieth, and the cello ultimately assumes a pizzicato vamp at m. 20. After two measures of this vamp, the piano enters. The jazz voice is paramount in this section as the accompanying cello simulates a plucked string bass. The piano states an E Dorian theme in octaves throughout most of this section (mm. 22–34). This section features a dramatic change in mood as Baker shifts from Baroque to jazz, complete with characteristic progressions and idiomatic piano voicings. A transitional passage (mm. 35–41) reengages the Baroque style. Imitative contrapuntal textures replace the jazzy piano/bass texture, and the piano harmonically prepares the ensuing section.

Table 1. Form in David N. Baker, Sonata for Cello and Piano (1973), second movement.

The B section begins with an imitative statement of the primary theme in E![]() minor. Continuing the imitative texture, Baker offers a few measures of the primary theme before digressing to unfamiliar territory. The composer explores registral extremes in both instruments, and another contrapuntal passage (m. 49) ensues. A solo piano interlude (mm. 50–58) invokes the jazz subject directly. Idiomatic chord voicings and progressions, performed with a quasi-rubato feel, recall a number of unmetered solo introductions by great jazz pianists.Footnote 13 Highlighting another shift in texture, the ensuing cello cadenza (mm. 59–69) addresses both the jazz and Baroque practice. Octatonic and whole-tone pitch collections and harmonies associated with jazz invade the cadenza and enrich its improvisatory aura. The final statement of the primary theme (mm. 70–81) features yet another expressive change in texture, as the cello and piano present a few measures of the main theme in parallel thirds. Following this recapitulation, the cello and piano assume the orthodox roles of solo and accompaniment instruments, respectively. Neo-Baroque and jazz influence mingle in this closing, as ornamental trills and turns in the cello are coupled with an evocative vamp and jazz voicings in the piano. Baker closes this movement with a gradual thinning of texture and a dramatically delayed melodic resolution.

minor. Continuing the imitative texture, Baker offers a few measures of the primary theme before digressing to unfamiliar territory. The composer explores registral extremes in both instruments, and another contrapuntal passage (m. 49) ensues. A solo piano interlude (mm. 50–58) invokes the jazz subject directly. Idiomatic chord voicings and progressions, performed with a quasi-rubato feel, recall a number of unmetered solo introductions by great jazz pianists.Footnote 13 Highlighting another shift in texture, the ensuing cello cadenza (mm. 59–69) addresses both the jazz and Baroque practice. Octatonic and whole-tone pitch collections and harmonies associated with jazz invade the cadenza and enrich its improvisatory aura. The final statement of the primary theme (mm. 70–81) features yet another expressive change in texture, as the cello and piano present a few measures of the main theme in parallel thirds. Following this recapitulation, the cello and piano assume the orthodox roles of solo and accompaniment instruments, respectively. Neo-Baroque and jazz influence mingle in this closing, as ornamental trills and turns in the cello are coupled with an evocative vamp and jazz voicings in the piano. Baker closes this movement with a gradual thinning of texture and a dramatically delayed melodic resolution.

A Closer Look: Theme and Harmony

Baker treats each of the three main thematic statements in this movement differently, although all three share the same pitch center, approximate length, and overall contour. I focus on the opening thematic statements because details of the composer's musical homage first appear in those measures. Example 1 illustrates the theme as stated by the piano in mm. 22–32. When creating melodies, Baker prefers to “think in terms of lyrical and flowing lines,” and has asserted that “the second movement of the cello sonata is an excellent example of how I feel about the lines should move.”Footnote 14 The asymmetrical theme is eleven measures long with strong modal inflections (E Dorian) in its opening. During the late 1950s, many jazz compositions and improvisational methods relied heavily on modal concepts, and Miles Davis's landmark recordings, Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959), were among the first experiments in modal jazz.Footnote 15 John Coltrane, tenor saxophonist on the latter recording, was deeply influenced by Davis's tunes and modal concepts, as they quickly affected Coltrane's outlook on improvisation.Footnote 16

Example 1. David N. Baker, Sonata for Cello and Piano (1973), second movement (mm. 22–32). Copyright © 1978 Associated Music Publishers, Inc. (BMI).

Example 2 aligns the opening of Baker's theme with the beginning of Coltrane's 1961 composition “Impressions.”Footnote 17 “Impressions” is one of Coltrane's earlier explorations with modal composition and improvisation, and was recorded about a year after Baker and Coltrane encountered each other at New York's Five Spot. The similarities between the melodies are quite suggestive. Both highlight descending minor sixth leaps from the seventh degree to the second, but whereas Baker's leap preserves the solemn mood of the theme, Coltrane's leap creates a melodic disjunction between the climax of the phrase and its cadence. Both melodies also feature the melodic contour of an ascending minor third followed by a descending perfect fourth. In the Coltrane tune, this figure is cadential; Baker, however, introduces the gesture at the beginning of the theme and utilizes it as a key motivic figure throughout the movement. In addition to these Dorian inflections, Baker's theme shares other similarities with Coltrane's tune. Pentatonic subsets are prominent in both melodies, as shown in Example 3. Although Baker and Coltrane both employ the third and seventh degrees of the Dorian mode, these pitches are somewhat less salient than the pentatonic pitches. The similarities of these themes suggest that de Lerma's assertion of “intentional reminiscence” offers more than what may appear as an attachment of a jazz figure to stylistic attributes—after all, Miles Davis would have been a more standard choice for modal jazz attributes. Modal ambiguity is yet another expressive attribute of Baker's theme as expectations initiated by the Dorian mode are thwarted at the conclusion of the thematic statement. Baker's theme begins with a strong emphasis on E Dorian, but he shifts modal inflections by replacing C![]() with C

with C![]() at m. 27 (Example 1). From m. 27 to the end of the theme, C

at m. 27 (Example 1). From m. 27 to the end of the theme, C![]() is the inflection of choice for Baker. This sophisticated modal ambivalence even permeates harmonic dimensions, adding colorful chord extensions throughout the movement.

is the inflection of choice for Baker. This sophisticated modal ambivalence even permeates harmonic dimensions, adding colorful chord extensions throughout the movement.

Example 2. Comparison of Baker's theme and Coltrane's “Impressions.” (Impulse AS 42, 1963, Universal Music Group)

Example 3. Baker's theme and Coltrane's “Impressions” (Impulse AS 42, 1963, Universal Music Group), [0, 2, 5] trichord comparison.

Extended tertian constructs (ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths) and chords with added or altered members appear throughout the movement as colorful emblems borrowed from jazz practice. Harmonies in the solo cello introduction are relatively sparse, and when the piano enters, it begins by stating the main theme in octaves (Example 1). When chords do appear, they demonstrate jazz voicings. The tightly blocked chord at the end of the first phrase is somewhat ambiguous in function, but the C![]() reinstates and continues the alternation of C

reinstates and continues the alternation of C![]() and C

and C![]() first heard in the cello vamp and, later, in the theme itself. The A minor chord at m. 26 is an example of a cluster or “crunched” voicing; it is followed by a wider voiced F

first heard in the cello vamp and, later, in the theme itself. The A minor chord at m. 26 is an example of a cluster or “crunched” voicing; it is followed by a wider voiced F![]() chord in m. 27. The fifth of this harmony restores the Dorian C

chord in m. 27. The fifth of this harmony restores the Dorian C![]() , but an eloquent C

, but an eloquent C![]() in the melodic line follows immediately. The expansion of the chord voicing in m. 27 and climactic dissonances created by the melodic G (the flat ninth) and C

in the melodic line follows immediately. The expansion of the chord voicing in m. 27 and climactic dissonances created by the melodic G (the flat ninth) and C![]() (the flat fifth) increase the emotive charge of this portion of the phrase. Stride piano treatments in m. 28 further enhance the jazz presence, as the left hand of the piano renders an open voicing of a complex dominant harmony. Enharmonic equivalence explains the odd spelling, as A

(the flat fifth) increase the emotive charge of this portion of the phrase. Stride piano treatments in m. 28 further enhance the jazz presence, as the left hand of the piano renders an open voicing of a complex dominant harmony. Enharmonic equivalence explains the odd spelling, as A![]() functions as G

functions as G![]() (the thirteenth) and E

(the thirteenth) and E![]() as D

as D![]() (the third). Baker's alternation of dense closed positions and open voicings of chords creates an effective harmonic accompaniment for the plaintive theme and suggests the variety of colors and textures a jazz pianist might explore with this tune.

(the third). Baker's alternation of dense closed positions and open voicings of chords creates an effective harmonic accompaniment for the plaintive theme and suggests the variety of colors and textures a jazz pianist might explore with this tune.

Certain chord progressions within this movement identify both blues and jazz subjects. Two of the three primary thematic statements, for example, highlight strong subdominant emphasis at the fifth measure (see m. 26), suggesting the characteristic placement of the IV chord in 12-bar blues.Footnote 18 Thus, a blues emblem resides within this jazzy, signified context. Other typifying progressions, such as pedal harmonies and tritone substitutions, also occur. Example 1 illustrates Baker's use of pedal harmonies to evoke jazz (see mm. 22–24). Each thematic statement begins with three or four measures of harmonies floating over an E pedal. The E pedal is also implied in the unaccompanied cello statement, as recurring E![]() s in the lower voice of the polyphonic texture indicate E centricity. Subsequent thematic statements that feature E-centered vamping patterns are more explicit regarding the pedal harmonies. The use of this device, in conjunction with the distinctive modal treatments, recalls a jazz voice in general, and John Coltrane in particular.Footnote 19Example 4 offers a hypothetical lead sheet harmonization of Baker's theme compared to John Coltrane's tune, “Naima,” which uses the pedal device to a great extent. The melodic leaps of Baker's theme, although not as dramatic, are also reminiscent of Coltrane's ballad. Tritone substitutions are hallmarks of jazz compositional and performance practice.Footnote 20Example 1 shows this harmonic feature at the cadence of the piano's thematic statement (mm. 30–31). One hears the harmony on the first two beats of m. 31 as an altered V chord, and although Baker colors this harmony with added notes on beat two, its cadential properties are clear. Baker substitutes an F13 (sharp 11) chord for the dominant on beats three and four. The pizzicato cello doubles the root motion in this measure emphasizing the tritone substitution, and magnifying the dominance of the jazz voice in both instrumental characters. Many other referential emblems emerge in transitional episodes, the cadenza, and motivic figures. Throughout this second movement, inflections in thematic and harmonic structures strongly signal a jazz presence, but more specifically the influence of John Coltrane. Even if Coltrane is not directly quoted, similarities in melodic contours and harmonic treatments signify correlations between the two figures, as the late 1950s and early 1960s constitute the years of their meeting and the beginning of Coltrane's experiments with modal jazz.

s in the lower voice of the polyphonic texture indicate E centricity. Subsequent thematic statements that feature E-centered vamping patterns are more explicit regarding the pedal harmonies. The use of this device, in conjunction with the distinctive modal treatments, recalls a jazz voice in general, and John Coltrane in particular.Footnote 19Example 4 offers a hypothetical lead sheet harmonization of Baker's theme compared to John Coltrane's tune, “Naima,” which uses the pedal device to a great extent. The melodic leaps of Baker's theme, although not as dramatic, are also reminiscent of Coltrane's ballad. Tritone substitutions are hallmarks of jazz compositional and performance practice.Footnote 20Example 1 shows this harmonic feature at the cadence of the piano's thematic statement (mm. 30–31). One hears the harmony on the first two beats of m. 31 as an altered V chord, and although Baker colors this harmony with added notes on beat two, its cadential properties are clear. Baker substitutes an F13 (sharp 11) chord for the dominant on beats three and four. The pizzicato cello doubles the root motion in this measure emphasizing the tritone substitution, and magnifying the dominance of the jazz voice in both instrumental characters. Many other referential emblems emerge in transitional episodes, the cadenza, and motivic figures. Throughout this second movement, inflections in thematic and harmonic structures strongly signal a jazz presence, but more specifically the influence of John Coltrane. Even if Coltrane is not directly quoted, similarities in melodic contours and harmonic treatments signify correlations between the two figures, as the late 1950s and early 1960s constitute the years of their meeting and the beginning of Coltrane's experiments with modal jazz.

Example 4. Comparison of Baker's theme and Coltrane's “Naima.” (Atlantic Records, 1960)

Sonata I for Piano, Quoting Coltrane

The composer's homage to John Coltrane in Sonata I for Piano moves well beyond suggestion and implication, evoking the jazz giant through quotation. Completed in 1969, Baker began composing the work in 1968, in the wake of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination and a meeting of the Black Composers Symposium in Bloomington, Indiana.Footnote 21 King's death served as inspiration for the second movement of this sonata and Baker's cantata, Black America: To the Memory of Martin Luther King (1968), as the impact of this tragedy prompted compositional responses from a number of African American composers.Footnote 22 In addition, during the time that the piano sonata was composed the Black Arts Movement was flowering. Larry Neal and other leaders of the movement viewed it as the “aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept,” proposing “a radical reordering of the Western cultural aesthetic.”Footnote 23 Participants in the movement exalted the role and place of music in the black community, celebrating blues and jazz as music of the folk and as liberated responses to the challenges of the black experience in the United States. These events and movements help shed some critical light on Baker's subtitles for the movements in the sonata. The first movement, entitled “Black Art,” is all the more intriguing when one considers Neal's proposed “radical reordering” of Western aesthetic ideals and the potential counterpoints with what might be expected within the first movement of a sonata. Subtitled, “A Song—After Paul Laurence Dunbar,” the sonata's second movement is directly linked to one of the first African American authors of critical acclaim known for the use of black dialect in his writings. Baker's treatment of the theme and variations motif in the second movement explores the limits of harmonic and motivic development. Inspired by Dunbar's poem, “A Song,” the second movement employs a potent lyricism while also making use of a densely chromatic harmonic palette. These and other unifying elements that occur throughout the sonata, but the focus here is on the third movement, “Coltrane.”Footnote 24

Music critic Donald Rosenberg referred to Baker's piano sonata as a “densely packed opus . . . which suggests affection for traditional architectures, but adds contemporary ideas to the mix.” The third and final movement exhibits all of the jazz vocabulary found in the cello sonata but takes those emblems “many steps further.”Footnote 25 Baker was deeply familiar with the music and style of Coltrane's playing, and Coltrane's death in 1967 must have also been an impetus for Baker because they were friends as well.Footnote 26 This technically demanding movement “portrays” the jazz giant through episodes of virtuosic fantasy, intense lyricism, and mixed-metered ostinato patterns over which the composer states angular melodic lines and gestures that suggest Coltrane and other jazz musicians of the late 1950s and early 1960s. The large-scale articulations of the movement's arch form move the listener from contemporary treatments of motive with loose pitch centers to a bona fide blues in F. Table 2 provides a form outline for this movement.

Table 2. Form in David N. Baker, Sonata I for Piano (1969), third movement.

In the A section, Baker attempted, as Santander suggests, “to integrate a saxophone technique used by Coltrane into pianistic language.”Footnote 27 This section contains multiple statements of single pitches presented in rapid succession and is suggestive of the uses of alternative fingerings that saxophonists use for various timbral effects. The composer develops this monophonic idea by interpolating different pitches into the single-note figures, ultimately presenting the rapid gesture with major triads with roots a tritone apart. A lyrical interlude follows (m. 12) and features a dramatic shift in texture. Metrical and tonal ambiguity characterize this melodic jaunt, as mixed meters and angular lines are accompanied with chord complexes and contrapuntal lines that do not employ a pitch center. The repeated sixteenth-note gestures return (m. 34) and now incorporate arpeggios that outline quartal harmonies and hybrid scalar passages based on octatonic and whole-tone collections. The B section is based on a six-measure ostinato figure that changes meter five times. This ostinato/groove is loosely based on F when it begins in m. 54. F is repeated as the first note of the ostinato seven times before Baker begins to drastically alter the pitch content of the underlying pattern. Although the composer plays with the pitch and rhythmic content within the ostinato later in the section, the metrical pattern remains consistent until the beginning of the C section. Coltrane's presence is merely suggested in the A and B sections, but he takes center stage at m. 126. Here is where we encounter an extensive quote from the saxophone solo in “Blue Train.”Footnote 28 Abbreviated statements from the opening sections round out this expressive arch, and the final utterance is the rapidly repeated, single-note figure that began the movement.

Heroes and influences from both Western and vernacular styles converge in this evocative movement. Baker once named Charles Ives and Béla Bartók as “specific influences” and I contend that if they were not direct influences, their impact on the structure and expressive profiles of the movement is highly suggestive.Footnote 29 Bartók is revered as one who studied and analyzed folk music, but he also explored the vast possibilities of arch form. Paul Wilson views the arch form as a “large symmetrical design” that “engenders specific expressive possibilities that would otherwise be unavailable for the work as a whole.”Footnote 30 Whereas Wilson makes reference to the larger, global form of Bartók's fifth string quartet in his study, the implications for smaller works or movements that employ the same form are intriguing—particularly in this piece. Amid the A and B sections that feature loose pitch centers and complex rhythms, Baker quotes a blues in F in common meter as the defining moment of the arch—the C section. Although the treatment of the quotation moves from jazz conventions to more modernist revisions over the course of four solo choruses, the quotation is introduced with standard jazz piano voicings and bass notes in root position. Thus, the structural highpoint and focal point of the movement is Coltrane's twelve-bar blues, and the composer provides profound clarity by preparing such a dynamic statement with tonally and metrically ambiguous episodes. Baker certainly knew many other tunes written by Coltrane, so why did he choose “Blue Train”? Perhaps it was a personal favorite of Baker's; Coltrane named “Blue Train” “as favorite among his own records” in 1960.Footnote 31 Baker's choice to use the blues at that particular moment in the movement, however, signifies much more. Jazz saxophonist and scholar Leonard Brown states that Coltrane had a “deep understanding of the blues” and wrote “over thirty [compositions] that either use the term ‘blues’ in the title or are harmonically and melodically based on the blues form with some variations.”Footnote 32 Baker also has a serious connection to the blues. His jazz compositions and arrangements utilize the blues form in conventional and imaginative ways. Jazz trombonist and pedagogue Brent Wallarab states, “The blues is Baker's music and an obvious choice for him to revisit whether it be for intense abstract experimentation of an expression of his swinging, soulful roots.”Footnote 33 The “roots” to which Wallarab refers are essential to our interpretation of timing and tone of the blues statement in this piano sonata. Recall the socio-political and personal circumstances surrounding Baker during the time this piece was composed. One reading of the blues in the overarching modernist compositional context might be a homecoming of sorts or a “roots” moment, interpreted by this author as a culturally grounded resolution in the middle of the relatively discordant and disjunct framings of the A and B sections. When defining the blues, James H. Cone states, “The blues express a black perspective on the incongruity of life and the attempt to achieve meaning in a situation fraught with contradictions.”Footnote 34 This “meaning” to which Cone refers is multidimensional, as the blues is a music of “experience”—of good and bad times. When considering this movement and the factors surrounding it, the expressive power of the blues is not only reflective of or reactive to protest and suffering but also projective of hope and revival. Baker's structural treatment of the blues quotation situates blues and Coltrane as heroes. Therefore, the statement of the “Blue Train” quotation as the centerpiece of the movement can be read as signifying the central (or fundamental) impact of Coltrane on Baker. The entire movement is indeed inspired by the work and style of John Coltrane, but the structural weight and saliency of the quotation depicts the profundity of Baker's homage.

The use of literal musical quotations suggests an influence of Charles Ives. Musicologist J. Peter Burkholder, in “‘Quotation’ and Emulation: Charles Ives's Use of His Models,” refocuses the argument about quotation in the music of Ives and describes a number of processes and techniques behind the use of preexisting material in the composer's output. Many of the processes he presents share commonalities with Floyd's concept of musical signifyin(g). For example, “quoting” is “a kind of oratorical gesture, a ‘quotation’ in the strict sense, which Ives uses most often for illustrating part of a text or fulfilling an extramusical program.”Footnote 35 Given the title of the movement, its historical context, and Baker's respect for his heroes, it is not difficult to see extramusical associations. Indeed, Baker's use of the improvised solo is “the use of preexisting material as a means for demonstrating respect for” John Coltrane.Footnote 36 I also note Burkholder's category of “paraphrasing,” which in some settings “form[s] a new melody, theme, countertheme, or principle motive” and “. . . most often involves incorporative some structural aspects of the source as well as melodic shape and details.”Footnote 37 Both of the movements discussed in this essay incorporate this type of paraphrase: the theme of the cello sonata involves melodic contours and harmonic structures attributed to Coltrane compositions, and certain sections of the “Blue Train” quote integrate contrapuntal lines modeled on the solo as accompaniment figures. Floyd's defining “trifling and teasing” is a conceptual parallel. These and other signifyin(g) properties and can be seen in Example 5, which offers the first solo chorus within Baker's quote. The parenthetical chord symbols show the harmonic structure of the twelve-bar blues form.

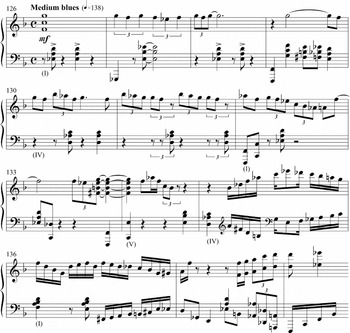

Example 5. David N. Baker, Sonata I for Piano (1969), third movement (mm. 122–34). Copyright © 1968 David Baker. Copyright assigned 2008 to Keiser Classical (BMI). All rights reserved. International Copyright Secured.

As mentioned earlier, these opening measures of the quotation feature devices that are standard to jazz performance practice. The left-hand voicing of the chord in m. 126 is typical of what a jazz pianist would play for an F13 chord—or for a richer, thicker rendition of F7. This voicing and subsequent voicings of B![]() 9 and C9 chords in mm. 130 and 133, respectively, verify the prominence of jazz performance conventions, tonal implications, and Baker's blues agenda. These treatments, including the cascading quartal lick in m. 129, are the predominant accompaniment figures in this first chorus and assist in providing the strongest sense of pitch centricity (key) of the entire movement. Although Baker offers a momentary slide upward to a G

9 and C9 chords in mm. 130 and 133, respectively, verify the prominence of jazz performance conventions, tonal implications, and Baker's blues agenda. These treatments, including the cascading quartal lick in m. 129, are the predominant accompaniment figures in this first chorus and assist in providing the strongest sense of pitch centricity (key) of the entire movement. Although Baker offers a momentary slide upward to a G![]() 13 chord in m. 127, exploring the tritone relationship with the dominant (C), the more noteworthy play with or signifyin(g) on Coltrane's solo in this chorus begins in m. 133. Again, the tritone relationship is highlighted as the F in the bass (beat 4) is set against the B major triad in the right hand. The significance of this moment, however, is in the use of texture. Baker harmonizes the G in the melodic line, marking the first truly pianistic (or non-idiomatic) treatment of Coltrane's saxophone solo.Footnote 38 Signifyin(g) continues in mm. 135 and 136 when the composer sets portions of the solo line with invertible counterpoint. These episodes are, for the most part, literal inversions, creating distant and striking contrasts to the jazz voice that has been primary up to this point. This brief excursion and the subsequent, but less literal, contrapuntal episode that concludes the first chorus (m. 137, beat 4) foreshadows the types of techniques and dissonant departures that Baker incorporates in the following choruses. Other modern techniques, such as the use of cluster chords, occur during this long quotation but most of Baker's play on and with Coltrane involves contrapuntal devices. Following the statement of four choruses of the “Blue Train” solo, Baker continues with various abstract ideas borrowed from the solo and admits that there may be other “unintentional” quotations.Footnote 39

13 chord in m. 127, exploring the tritone relationship with the dominant (C), the more noteworthy play with or signifyin(g) on Coltrane's solo in this chorus begins in m. 133. Again, the tritone relationship is highlighted as the F in the bass (beat 4) is set against the B major triad in the right hand. The significance of this moment, however, is in the use of texture. Baker harmonizes the G in the melodic line, marking the first truly pianistic (or non-idiomatic) treatment of Coltrane's saxophone solo.Footnote 38 Signifyin(g) continues in mm. 135 and 136 when the composer sets portions of the solo line with invertible counterpoint. These episodes are, for the most part, literal inversions, creating distant and striking contrasts to the jazz voice that has been primary up to this point. This brief excursion and the subsequent, but less literal, contrapuntal episode that concludes the first chorus (m. 137, beat 4) foreshadows the types of techniques and dissonant departures that Baker incorporates in the following choruses. Other modern techniques, such as the use of cluster chords, occur during this long quotation but most of Baker's play on and with Coltrane involves contrapuntal devices. Following the statement of four choruses of the “Blue Train” solo, Baker continues with various abstract ideas borrowed from the solo and admits that there may be other “unintentional” quotations.Footnote 39

The depth of David Baker's reverence to African American musical traditions resonates throughout the second movement of his Sonata for Cello and Piano and the “Coltrane” movement in the piano sonata. Translating some traits of his musical culture into a more universal musical expression, the cello and piano present distinctive voices that signal both jazz and Baroque practices. Emblems from the vernacular (modal jazz, jazz harmonies, blues symbols, etc.) emerge in Baker's hip thematic and harmonic constructs, but the formal character of the unaccompanied cello and learned contrapuntal textures balance the complex discourse. John Coltrane steps to center stage in the piano sonata, as Baker's signifyin(g) position shifts from one of inference to one of direct engagement with the music of the legendary saxophonist. Baker's compelling play with implication and quotation in these movements provides fertile ground for continuing studies on the variety of African American composers’ signifyin(g) positions and the resulting implications upon the local and global structures of the works they produce.