In the summer of 2007, while singer and guitarist Tony Melendez was in South Texas for a pair of performances, a promoter filmed and quickly posted a video on YouTube entitled “Tony Melendez plays ‘Let It Be’ on South Padre Island.” The video shows Melendez seated next to a kitchen table as he plays his arrangement of the Beatles’ classic. After a shorter, more propulsive introduction than the original, Melendez launches into an energetic verse as he accompanies himself on his guitar. Listening to the clip, it would be easy to locate its appeal in the streamlined arrangement, the more thoroughly syncopated melody, or Melendez's impassioned vocal delivery. Over the last decade, however, commenters have primarily focused on Melendez's skill as a guitarist. Some need only a single word to express their reactions. “Amazing,” reads one. “Respect,” states another.Footnote 1 And lest we assume that such comments come only from non-musicians with no real knowledge of the object of their praise, many viewers write from a place of personal comparison. “This guy can play better than I can,” writes one, and another declares: “I'm a musician . . . and I feel so not worthy.”Footnote 2

Most guitar performances that sound similar to Melendez's—neither particularly fast nor loud, making use of common harmonies as part of a background accompaniment—do not draw attention to their skillful execution. Listeners, however, do not encounter Melendez's performance as abstract, disembodied sound. Instead, both the text and the visuals foreground his body as the music's source, for just as the clip begins, the words “Toe Jam” appear at the top of the screen along with the explanation, “musician Tony Melendez was born in Nicaragua without any arms.”Footnote 3 The video quickly drives the pun home: Melendez plays guitar with his feet, fretting strings with his left foot while his right heel rests on the guitar's lower bout to facilitate his strumming. Although his music is not outwardly flashy, his method of playing the instrument leads audiences to engage his performances as virtuosic display.

If Melendez's performances of pop classics, Catholic devotional songs, and contemporary Christian music lack the typical sonic markers of virtuosity, his sincere stage persona is even further from the archetypal figure of the virtuoso. The canonic iteration of the self-promotional, nearly omnipotent virtuoso comes in the form of nineteenth-century pianist Franz Liszt, whose prominence within theorizations of virtuosity has given rise to what James Deaville has dubbed the “Liszt problem.” Despite nuanced scholarly arguments that stress the historical and cultural specificity of Liszt, he continues to serve as the implicit template for interpreting virtuosity.Footnote 4 Even discussions that never mention the famous pianist—covering genres from jazz to heavy metal—are largely consistent with his precedent in their emphasis on technical innovation, speed, masculinized (and often sexualized) power, and overwhelming display.Footnote 5

In this article, I explore Tony Melendez's example in order to rethink the phenomenon of virtuosity and the potential meanings of musical skill. In particular, I take into account someone whose body is treated as simultaneously virtuosic and disabled in order to foreground the social construction of both virtuosity and disability. In addition to the extensive literature in disability studies, my account is indebted to a wealth of previous scholarship that emphasizes the sociality of virtuosity. Jim Samson, for example, argues that audiences shape virtuosity “almost as much as performers; they mould it to their own needs.”Footnote 6 Dana Gooley similarly writes that Liszt's displays of pianistic power made him “the carte blanche on which the world of the 1830s and 1840s wrote itself.”Footnote 7 And likewise, Robert Walser's landmark study of heavy metal describes virtuosity as a “musical technique” that “functions socially.”Footnote 8 All these voices affirm that the virtuoso is deeply social—a point I echo heartily. Yet in all these accounts virtuosity itself remains (at least initially) individual, most often denoting a particular type or degree of skill that the virtuoso possesses and then publicly displays or enacts.Footnote 9 Such a concept of virtuosity is operative far beyond these three authors; everyday references to virtuosity as something that belongs to the performer (as Liszt's or Melendez's virtuosity) provides linguistic evidence of this widespread, implicit conceptualization. The individualist concept of virtuosity ultimately goes hand-in-hand with the Liszt problem: when we focus on musicians whom we readily assume to possess virtuosity, sociality enters late. Its role can only be to provide context for the performance and subsequent interpretation of virtuosity, which remains prior.

By considering Melendez's embodied musicality within the frame of disability studies, I want to suggest a shift in the location of virtuosity away from individual bodies and their particular degrees of skill. Such a project requires a more general definition of virtuosity than that usually employed (or implied). Throughout this article, then, I use virtuosity to designate a social phenomenon in which skill is made apparent and socially meaningful through the discursive, musical, and perceptual practices of performers, promoters, and audiences. The distinguishing feature of my account lies in its insistence that sociality is central not just to virtuosity's interpretation but to its very constitution: virtuosity is social from the very beginning. It is neither individual excellence nor external judgment but skill made apparent—an intentionally passive construction that highlights the dispersed agency at work within it. This positions sociality as a structural part of the phenomenon itself, not as mere context in which pre-existing virtuosity takes on new meanings. Put more concretely, Tony Melendez is not an isolated body imbued with virtuosity that then bursts into the social world through performance, but one whose embodied skill becomes virtuosity precisely through the socially structured cultural and material world in which he is always already embedded.Footnote 10

This article begins by focusing on the similarities and tensions between virtuosity and disability, drawing on recent work in music and disability studies that demonstrates how agency and bodily limits are constructed in discursive and material ways. I then turn to Melendez's performances as an example of the complex intersection of virtuosity and disability, with particular attention to his landmark performance for Pope John Paul II in 1987 and to my own ethnographic analysis of three of his performances in 2014 and 2019. I conclude by discussing issues of merit, identity, and power, posing in earnest a question more often used as a dismissive rejoinder: who cares? Melendez's example shows how bodily difference and the complex subject positions of both performers and audiences contribute to what counts as skill, creative labor, and agency within a particular context.

Intersections of Disability and Virtuosity

In everyday usage, disability and virtuosity are regularly opposed, with the former indicating deficiency and the latter denoting superabundance. Yet the potential affinities between musical skill and disability were pointed out in the earliest iterations of musicology's interaction with disability studies. Alex Lubet demonstrates that musicality is not universally celebrated, and that in some contexts, such as under Taliban rule, it may even function as disability.Footnote 11 Joseph Straus connects disability with the display of musical skill, noting that “the extraordinary, prodigious, even monstrous bodies” of musicians mean that musical performance bears some similarities to “a freak show: audiences pay to see and hear figures whose appearance and ability deviate far from the norm.”Footnote 12 Scholars within disability studies, conversely, have been less eager to draw such comparisons. This reluctance likely stems in part from a suspicion of the ways that other fields—particularly media studies and science and technology studies—employ metaphors of prosthesis and disability without attending to actual experiences of either.Footnote 13 Similarly, the practices of virtuosity have utilized disability in problematic ways. One of the longstanding strategies for making skill conspicuous is playing an instrument in an unusual manner, often to comic effect. Performing with a “blindfold” or an arm behind the back draws attention to the ability of the performer's body to adapt and display marked skill. Even the term “blindfold” reveals the ways that such practices approach what Tobin Siebers calls “disability drag.”Footnote 14

A further tension between music studies and disability studies is that, as William Cheng contends, most musical scholarship could be construed as “ability studies”—concerned with the remarkable achievements of musicians.Footnote 15 Yet “ability studies” is not simply the opposite of disability studies, for, as Alex Lubet argues, degrees of impairment and capacity are “universal human qualities.”Footnote 16 Instead, it is the centrality of ability to musical scholarship that makes engaging with disability so crucial; the two concepts, as Dan Goodley argues, “can only ever be understood simultaneously in relation to one another.”Footnote 17 Disability is not simply the opposite or absence of ability, as the widespread practice of interrupting the word with some form of punctuation—dis/ability or (dis)ability—acknowledges. The term simultaneously invokes and problematizes the very concept it appears to negate, identifying disability as “the invisible center around which our contradictory ideology about human ability revolves.”Footnote 18 Considered in this light, virtuosity and disability are more similar than they might first appear. They are not individual facts about isolated bodies but ways of interpreting the material reality of bodies interacting with their social and physical environments. Both are understood as meaningful variations of human embodiment that give (supposedly) private bodies public meaning. Both remain intensely personal but irreducibly social. The difference between them is not simply one of valence but how each configures agency in their social and musical worlds.Footnote 19

The historical development of attitudes towards disability can be instructive here. Prior to the nineteenth century, disability within Western thought was regularly linked to the divine. In the words of Joseph Straus, it was either “affliction” or “afflatus”—judgment for some sin or divinely endowed “transcendent vision.”Footnote 20 Roddy Slorach further notes that these ideas were often combined in discourses that framed “impaired individuals as cursed but also blessed, feared but also revered, not quite human (monstrous) but also more than human (associated with divinity).”Footnote 21 Despite the application of these attitudes to specific impairments and bodily variations for much of human history, disability was not operative as a general category until the nineteenth century, precisely because there was no imagined “center” from which to deviate. The divine was posited as ideal, meaning normality was hardly an intelligible concept—everyone differed from divine perfection in some way.Footnote 22 The words relating to normality did not even enter European languages until the nineteenth century, but the ascendancy of the concept transformed how people conceptualized of their own bodies and those of others. Lennard Davis points to the disciplinary development of statistics as a particular discursive field in which concepts like “norm” and “average” became not only intelligible but “imperative.”Footnote 23 No longer a society of human beings who varied in innumerable ways, people could be organized in terms of statistical measurement.

Within music, this statistical approach to human variation produces a linear model of embodied capacity that ranks skill on a simple continuum: in the middle stands an imagined normative average with degrees of virtuosity and lack of ability departing from the center in unequivocally opposite directions. Attempting to apply such a model to Tony Melendez demonstrates its inadequacy, for it prompts questions that are at best unproductive: does he play guitar well enough for it to count as virtuosity? Is he better than most? The fact that his audiences find his display of skill impressive and meaningful demonstrates that virtuosity happens in his performances, regardless of whether his playing meets a specific set of necessary and sufficient criteria. Despite the simplistic allure of the linear model of embodied capacity, forms of human embodiment do not move along straight lines through neatly defined, two-dimensional space; they follow multiple axes and create constellations of difference. Whereas the single continuum of inability-normativity-virtuosity suggests a straightforward measuring or comparison of bodies, the question of meaning within such constellations of difference is contested, and the bodies involved always exceed their categorization. Rather than representing different steps on a linear scale, “virtuosity, ability, and disability are interlocking corporeal performances.”Footnote 24 The trope of virtuosity as “excess” may imply a simple exceeding of the norm—far to one side of the continuum—but I would suggest virtuosity is excessive in the sense that it overflows the linear model of embodied capacity altogether. The potential skills involved in musical labor are too numerous, the subject positions of performers and audiences too complex, and the values involved in the phenomenon of virtuosity too interdependent to be mapped so easily. The challenge, then—which I take up in the following section—is to theorize the thoroughgoing sociality of virtuosity without diminishing or misconstruing its fundamental embodiment.

The Social Model of Disability and the Complex Embodiment of Virtuosity

The linear model of embodied skill bears remarkable similarities to the medical model of disability, and disability studies’ critique of that model can further provide a path forward in thinking about virtuosity. Although there have always been people with physical impairments, it was the rise of industrial capitalism during the nineteenth century that produced a need to distinguish between bodies based on their capacity for what was considered productive labor.Footnote 25 The body's potential for labor helps explain why the meaning of disability remains so mutable; it regularly denotes an imperiled relation to some central form of culturally meaningful labor. During the US Civil War, for example, disability denoted a lack of “capacity to serve in the armed forces” precisely because this was the most salient form of labor.Footnote 26 Thus the type of labor expected of a subject often determines what counts as a disability and what is simply difference.

Within the frame of the “normal” and the focus on the (temporarily) able-bodied worker, the dominant conceptual approach to disability became the medical model. This model offers a highly “individualist” account of disability that defines it first and foremost “in terms of biological deficit.”Footnote 27 From this standpoint, disability might have social effects or meanings within a family or community, but it remains at root an individual condition. Sociality enters at the end when an ostensibly separate society reacts to the individual who was already disabled. Yet even as the medical model attempts to isolate disability within the individual, it elevates the medical practitioner as an outside authority who names the disability through diagnosis. Although some forms of disability may be stigmatized from the beginning, bodily difference can also officially become disability through the pronouncement of such a diagnosis.

The parallels between the medical model of disability and the critic-centered model of virtuosity forwarded by scholars like V. A. Howard and Philip Auslander are striking.Footnote 28 The common use of superlatives to describe performers—as the best, the fastest, the most gifted—regularly implies measurable excess situated within the performer's body. In this understanding, virtuosity is “a surfeit of ability, a mastery over the human body and all its pesky deficiencies.”Footnote 29 This bodily difference—in this case, the presence of great skill—is a fact about a body. It may have social consequences and meanings, but it is, at base, an individual quality. Yet this model also places great emphasis on naming, because, as Philip Auslander argues, the virtuoso cannot confer the title on him or herself.Footnote 30 Thus the critic/expert stands in the same role as the medical practitioner, supposedly separate from the phenomenon under question but uniquely empowered to name it.

Pushing back against the medicalization of disability, activists in Great Britain in the 1970s began advocating for a social model that distinguishes between impairments, which are “individual and private,” and disability, which is “structural and public.”Footnote 31 Within such a model, as Sayantani DasGupta explains, “an individual with Down syndrome having cardiac issues” is an impairment, whereas “the prejudice and discrimination preventing the woman with Down syndrome from accessing appropriate educational or work opportunities” is a disability.Footnote 32 The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS), a pioneering disability rights organization in the United Kingdom, presented the social model in these terms: “it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments, by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society.”Footnote 33 This social model was designed to motivate political action; it was a “practical tool” used to communicate to a wide array of stakeholders, and not, as Michael Oliver writes, “a theory, an idea or a concept.”Footnote 34 Subsequent scholars like Lennard Davis have pointed out that while carrying out its political critique, the social model also “relies heavily on a medical model for the diagnosis of the impairment.”Footnote 35 Even the example above takes the medical diagnosis of Down syndrome as its starting point. As an approach designed to undergird social organizing around disability rights, its application of strategic essentialism is understandable. Yet as many subsequent scholars of disability have noted, the model continues to locate impairment in isolated individuals, treating it as prior to and separate from disability, which is given over entirely to oppressive outside forces.

Against this tendency to think of impairment as preexisting, Tobin Siebers insists that sociality and bodily difference must be conceptualized together, although he has concerns about constructionist thinking regarding bodies. For Siebers, a “weak” social constructionism sees ideas, attitudes, and discourses as simply influencing the perception of bodies, whereas “strong” constructionism “posits that the body does not determine its own representation in any way because the sign precedes the body in the hierarchy of signification.”Footnote 36 Neither is adequate, as the former attempts a “common sense” approach that can be insufficiently critical, whereas the latter erases bodies in favor of a web of signification. Siebers's solution is to insist that social construction itself is always “complexly embodied.” By this he means that constructions possess “both social and physical form,” and that “both sides push back in the construction of reality.”Footnote 37 Siebers's theory of complex embodiment embraces the reality of disabled bodies without naturalizing that reality. It takes the two social constructionist approaches that sociologist Scott Harris locates on opposite ends of a continuum—“objective” attention to the construction of “real states of affairs” through social forces and “interpretive” arguments about the meanings that people experience within those circumstances—as recursively related.Footnote 38 Individual impairments, social attitudes, and built environments always feed back into each other within actual social worlds. Interpretations arise in relation to socially and historically constructed “real states of affairs,” and these in turn shape the bodies and phenomena that they interpret without straightforwardly determining them.

In this formulation, there is no need to posit bodies or discourse as prior to one another, for rather than dissolving impairment entirely into a strong (i.e., reductively discursive) constructionism, impairment is, as Tom Shakespeare argues, “always already social.”Footnote 39 It is shot through with cultural attitudes and lived within material, social, and cultural environments. Locating the relationship between impairment and disability is then an ongoing interpretive dialectic rather than a one-time act of contextualization or focus. Impairments are lived within a shared world, and disability does indeed reference bodily difference that often takes the form of impairment, but these are not inherent to bodies themselves. Both “impairment” and “limits” arise through “a hypothetical set of guidelines” partially based on the physiology of typical human embodiment, but whose “sociopolitical meanings and consequences are entirely culturally determined.”Footnote 40 Furthermore, these meanings are often concretized within the built environment. Stairs serve to disable those in wheelchairs whereas ramps do not. The disabling impact of other objects is less clear: guitar necks seem to disable those without arms or hands—unless, of course, they can learn to play with their feet. In any case, such limits are relative, not essential.

Likewise, embodied capacity is just as thoroughly social and complexly embodied as impairment. Framing embodied capacity in terms of skill rather than ability can clarify this point. Whereas ableist ideology may construe ability as a sort of ever-ready potency applicable in any circumstance, skill is a thoroughly situated and social phenomenon. As Tim Ingold argues, skills are “capabilities of action and perception of the whole organic being (indissolubly mind and body) situated in a richly structured environment.”Footnote 41 Rather than imagining skill as endless capacity that transcends the world through its power, the embodied practice of skill is, as Richard Dreyfus argues, a matter of “skillful coping” with that world.Footnote 42 Skill is at once environmental, social, and embodied, and the cultivation and practice of any skill depends upon its relation to the social and material world in which the embodied subject undertakes it, as Melendez demonstrates.

Accommodation and the Normal Performance Body

Another way of defining skill that brings it into closer conversation with disability studies is to say that skills arise as a result of the accommodations between the embodied subject and the environment. Whereas Ingold's description of a “richly structured environment” suggests a productive and positive relationship with the embodied subject, disability scholars and activists have consistently pointed to the ways that practices of exclusion and segregation are concretized into built environments and cultural objects. In a statement that is axiomatic in disability studies, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson declares that “printed information accommodates the sighted but ‘limits’ blind persons.”Footnote 43 Her specific use of language is important—the printed word accommodates the sighted—as it challenges the common understanding of accommodation as the way “normal” technologies are altered for use by those with extraordinary bodies and instead posits accommodation as a basic feature of tools and technologies. It is an affordance that allows but does not determine a particular action, and in fact all human-produced physical objects are made in some way to accommodate human use.Footnote 44 Accommodation does not remove individual effort or action; it provides the very structures through which people encounter their capacity to act.

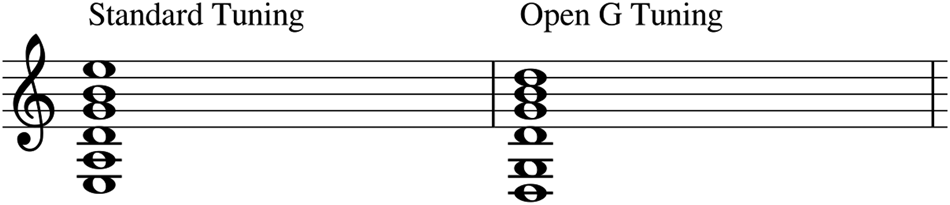

If this discussion frames accommodation as an expansive component of our embodied engagement with the world, Melendez shows that aspects of it can also be rather straightforward. Placing the guitar on the ground is simple, and the lower bout easily supports his right heel (although Melendez has had to seek out sturdier instruments and have some repaired that did not structurally support the added weight). Melendez further utilizes an open tuning, meaning a tuning that produces a recognizable chord without fretting any strings. Many non-disabled guitarists use open or alternate tunings that differ from the fourths-based “standard” tuning, and Melendez was by no means the first or only musician to use them in order to accommodate bodily difference. Joni Mitchell, for example, tells the story of turning to alternate tunings because her left-hand had become “somewhat clumsy because of polio.”Footnote 45 If this change was originally conceived as a physically required accommodation, it came to be heard as a mark of originality.Footnote 46 Open tunings reduce the demand of forming complex shapes that stretch across multiple frets, and it was seeing someone perform in open G tuning that first allowed Melendez to imagine taking the guitar up in earnest (Figure 1). Whereas playing a C major chord in standard tuning requires fretting a string in each of the first three frets, the same chord (in a different voicing) can be achieved in open G tuning by fretting all the strings within the fifth fret. Melendez can thus utilize his left big toe to compress several strings at once within a single fret, and he often plays in the keys of D or G so that he can make use of the open top string as a drone on the first or fifth scale degrees of the key.

Figure 1. The fourths-based “standard” tuning compared to the open G tuning Melendez uses.

Despite Melendez's description of the tuning as the “secret” to his playing, it is not the only way to play guitar with the feet. Melendez himself sometimes uses other tunings, and other guitarists like Mark Goffeney and George Dennehy both play with their feet in standard tuning. Furthermore, Goffeney and Dennehy play in more blues- and rock-infused styles, providing proof that playing the guitar with one's feet does not necessitate a singular technique or stylistic approach. Melendez's tuning accommodates his aesthetics as well as his body.Footnote 47

Instruments, repertoires, and interpretive practices vary widely in their capacity to accommodate different forms of embodiment. As Alex Lubet notes, forms of bodily difference that may be disabling in one tradition may be “little or no impairment, no impediment to function” in different musical worlds.Footnote 48 Yet both instruments and repertoires often imply what Blake Howe calls the “normal performance body,” which can take advantage of the accommodations already built into the standard technology or piece of music:

For example, musical instruments and scores—plus the cultural expectation that they should be performed in a particular way—work together to imply the bodily shape of their intended performer. This normal performance body usually possesses all limbs, with above-average hand and finger size, lung capacity, and strength, among other qualities. Most violin designs imply a two-handed, two-armed, and multi-fingered performer with a flexible neck. Brass instruments similarly imply a one- or two-handed, multi-fingered performer, whose mouth is capable of forming a strong, effective embouchure; tubists must also have the strength to lift their heavy instrument.Footnote 49

The interplay between the normal performance body and the particular affordances of an instrument determines to a large degree what counts as virtuosity. An amazing polyphonic display on one instrument (for example, the classical guitar) may be underwhelming when played on another with more extensive range and polyphonic potential (such as the piano); what is impressive as a solo piece is likely pleasant but unremarkable as a piano four-hands arrangement. Likewise, a piece may be an astounding feat when played by a five-year-old child but represent only expected progress for the conservatory student in her twenties. Even a showpiece as canonical as the third of Liszt's Trois études de concert is impressive not simply because of the extensive hand-crossings it requires, but because those techniques are necessary to create a texture that seems best suited to a pianist with three hands and the normal performance body has only two.

Without the key components of the implied normal performance body of the guitar, Melendez's playing becomes an amazing feat. Indeed, his body is so radically different from the one presumed necessary to play guitar that, before he began his performing career, people often expressed disbelief that he played at all:

When it came to the music, people didn't believe it. Tony play the guitar? It was always that question, “really?” To the point where they would come, maybe like my mom's friends, they knew or heard that maybe I played but it's always that big question mark. Then they come to the house and they're asking, “Well, who's playing the guitar?” because I'm in my bedroom. “Tony.” “No way.” It was always like that, “no way.” They'd have to literally walk in and see it. So there had to be that sense of reality, that sense of “no way, this can't be real” until they step in and see it, and then it became music to them.Footnote 50

Having seen him play, his visitors gained a basic understanding of how he manipulated the guitar, which in turn transformed their experience of his playing. Although vision is not always necessary to understand or experience virtuosity, it continues to be particularly important as a way of unsettling the assumptions that people have about how music-making must be accomplished. If Melendez's skill might hover as a question that potentially distracts from his music—as it did for the friends who visited his childhood home—visual confirmation allows the basic knowledge of his approach to drift between foreground and background in individuals’ musical experience.

In performance or video, Melendez's bodily difference is decidedly visible, and as Blake Howe argues, such “external and exposed” bodily difference “may immediately engulf a disabled person's public identity.”Footnote 51 Yet, as Howe points out, the question of audibility in musical practice is a different matter. It is a point of pride for Melendez that, although there are certain harmonic extensions that he has to have his band fill in, there is no obvious limitation in his sound as a guitarist. He is invested in sonically passing as a competent and therefore unremarkable rhythm guitarist within his particular musical idiom; he is not “audibly disabled.” Although many scholars look to disabled artists and musicians as sources of potentially resistant or even revolutionary aesthetic models, Melendez does not challenge widespread expectations of how a guitar or singer-songwriter should sound. As far as it pertains to virtuosity, this is for the best; his passing is what makes his ability all the more impressive for his audience.

Melendez employs this language of passing in describing his own skill: “I'm not the greatest guitarist in the world, but if you put me behind the curtain and it's kinda like a common player, not a super excellent player, kinda in between, and you put me behind a curtain and he's singing [and] I'm singing: who's playing with their feet? Unless you knew my voice or knew me, then I don't think you'd know.”Footnote 52 Whereas Melendez earlier described vision as essential to people's acceptance of his skill, his point here is that the absence of the visual might make audiences appreciate his playing apart from his physical difference. In actual practice, however, Melendez does not attempt in any way to hide how he plays; he often plays on a platform raised even further above the stage, cameras regularly zoom in on his feet (sometimes at his own request, at least in the case of our first interview), and his promotional materials—with references to the “toe Jam band” and pictures of his playing—tend to draw attention to it. Whether or not Melendez is visually present, his sound remains unmarked even as his mode of sonic production is definitively marked.

Media elements serve to further emphasize the role of Melendez's body in producing virtuosity, as even his smaller performances feature projected close-ups and topical slide shows that his brother José runs from the sound booth. More elaborate settings, like Melendez's 1987 performance for Pope John Paul II, utilize media even further. The 1987 Catholic youth rally in Los Angeles was simulcast to gatherings in three other US cities, allowing crowds to participate in real-time without actual bodily co-presence. And the experience of those in the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles was highly mediatized, with screens projecting close-ups of the Pope and Melendez in ways familiar to anyone who has attended a large concert or sporting event in the age of electronic media. Media theorist Philip Auslander identifies these elements of the “simulcast and the close-up” as aspects that were once “secondary elaborations” of an essentially “live event” that have now become key media elements of “the live event itself.”Footnote 53 Melendez's body clearly matters for his audience, but even in “live” performance it is not straightforwardly present. In many ways, it is hyper-present, as regular split screen close-ups (Figure 2) help maintain multiple points of emphasis: on one side his singing and facial expressions convey devout religiosity as on the other his feet display unlikely virtuosity.

Figure 2. Split Screen Shot during Melendez's Performance for the Pope, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlZPYGBXQ44.

Listeners, then, must take Melendez's body into account in order to experience his performances as virtuosic, but this does not suggest a sort of qualified approach to “disabled virtuosity” that treats him as an exception to normal judgments. Instead, Melendez shows that there is no such thing as unqualified virtuosity. The reaction, “I can't believe he did that with his feet!” is similar to reactions to other guitarists in which the exclamation “I can't believe she did that,” leaves off the assumed phrase, “with her hands!” The presumed limitations and possibilities of bodies, instruments, and repertoires always inform our understandings of skill, but we are not always explicitly aware of them.

The Papal Kiss and the Overcoming Narrative

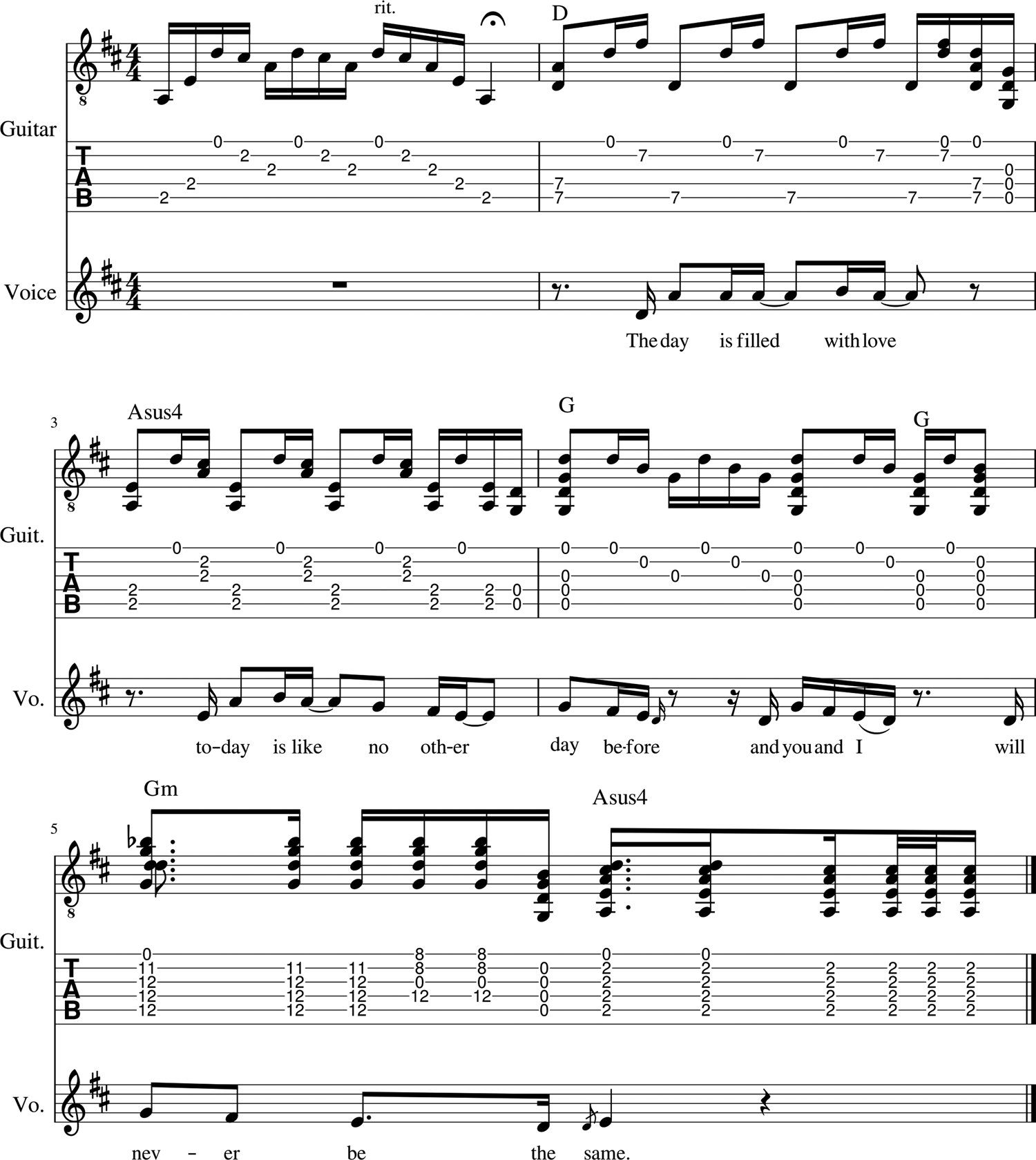

Prior to 1987, Tony Melendez was not widely known outside his direct social circle of family, friends, and members of the Catholic church that he attended in Los Angeles. But, on September 15, 1987, Melendez sat on a small stage with his guitar at a Catholic youth rally held for Pope John Paul II's visit to Los Angeles. “Holy Father,” a young man declared, “we now have a special gift that we would like to present to you. Our gift represents courage, the courage of self-motivation and family support. Our gift is music and a performer that says, ‘when I sing, I hear the Lord.’ Holy Father, we are proud to present to you Tony Melendez.”Footnote 54 At this, the Pope turned towards Melendez, who sat with his guitar on the floor in front of him. As the crowd cheered, Melendez began to play a cascading arpeggio before launching into the song's simple progression. He played adeptly, alternating picking and strumming to build momentum through the opening measures.

The song he played for the Pope was a wedding ballad by Ron Griffen called “Never be the Same” (Figure 3). Over his guitar accompaniment, Melendez sang out in a full tenor: “today is like no other day before, and you and I will never be the same.” This song was likely chosen because of Pope John Paul II's extensive theological teachings on marriage as a reflection of God, but the lyrics also describe the impact of the performance on Melendez's own life.Footnote 55 As the song concluded, the Pope rose to his feet and leapt from the stage. To the roar of the crowd, he approached the young guitarist and kissed him. The Pope then addressed Melendez, and instead of praising the song's theological message or its aesthetic impact, he spoke of the guitarist's character.Footnote 56 “You are truly a courageous young man, a courageous young man,” declared the Pope. “You are giving hope to all of us. My wish to you is to continue giving this hope to all the people.”Footnote 57 The performance, the kiss, and finally the Pope's words launched Melendez's performance career, fusing his various social identities in the public eye: he was a person with a disability, a devout Catholic, and a musician whose stirring performance had quite literally moved the pontiff to make physical contact with this extraordinary body.Footnote 58

Figure 3. Opening to “Never Be the Same.”

As this pivotal event makes clear, the relationship between Melendez's disability and his display of musical skill is regularly cast in the common disability narrative of overcoming. This was the clear subtext of the Pope's words: Melendez is “courageous” because he has done something out of the ordinary, something that the Pope and everyone else likely would not have considered possible—up to the very moment that they witnessed it. Jay Dolmage identifies this narrative as the myth of “overcoming or compensation”:

In this myth, the person with a disability overcomes their impairment through hard work or has some special talent that offsets their deficiencies. … [T]he connection between disability and compensatory ability is intentional and required. The audience does not have to focus on the disability, or challenge the stigma that this disability entails, but instead refocuses attention toward the “gift.” This works as a management of the fears of the temporarily able-bodied (if and when I become disabled, I will compensate or overcome), and it acts as a demand upon disabled bodies (you had better be very good at something).Footnote 59

Overcoming narratives are widely (and duly) critiqued in disability studies as distracting, dehumanizing, and even dangerous. So-called “human interest” stories on television news programs are particularly prone toward facile versions of the overcoming narrative that celebrate the supposed negation of disability through individual effort while ignoring the social and structural injustices that people with disabilities face.Footnote 60 Furthermore, they often take on a patronizing tone of pity for the disabled person and the “tragedy of their fate.”Footnote 61 Perhaps most insidiously, they broadcast the implicit message that disabled people must be inspiring or invisible.

Beyond these broad political critiques, the overcoming narrative may even fail to challenge the prejudice and negative assumptions regarding the disabled person at the center of the narrative. As my conversations with concert attendees demonstrate, audiences may assume Melendez's facility is somehow distinctly musical and thus limited entirely to performance. A concert organizer remarked to me that the most impressive thing he saw at the performance was Melendez texting beforehand, and a colleague, when told about Melendez's playing responded, “ok, but how does he tune?”Footnote 62 The apparent danger of displays of agency within relatively bounded performance events is that audiences may readily assume that such agency is contained entirely within that context.

Despite its pervasiveness, I would argue that the overcoming narrative in this instance is less totalizing than both celebrations and critiques of it tend to allow. For although Melendez has actively embraced the Pope's call to bring hope and the overcoming myth embedded within it, there are important places where the narrative breaks down and fails to describe the lived reality of the situation for both Melendez and his audience.Footnote 63 First, although Melendez's exhortations to audiences regularly emphasize personal motivation and hard work, his story also conveys the more realistic experience of interconnected beings caring for one another.Footnote 64 Speaking of the daily tasks made more difficult or impossible by his lack of arms, Melendez admits, “I don't have 100 percent freedom.” But, he adds, “I don't think anybody does.”Footnote 65 This notion of agency and interdependence was present even in his initial introduction to the Pope, which described his courage both in terms of “self-motivation” as well as “family support.” Such a small fact is noteworthy, considering the tendency to portray the disabled person in “inspirational” stories as either isolated hero or helpless beneficiary of others’ kindness. Second, Melendez's body is not strictly speaking “overcome” through his performance of musical skill. Rather than occluding it through his remarkable achievements, his body remains central, and he even seeks to undercut the ways that he is marked as “extraordinary.” In performance, he tells the story of a child asking what it feels like to have no arms. His answer: “human.” He goes on to state matter-of-factly, “I've lived in this body all my life.” It is important that Melendez includes his body within this assertion of a shared humanity rather than using such claims to suppress his bodily difference, as is often the case within overcoming narratives. Rather than erasing his physical difference, it is a legitimate part of his human experience that need not be corrected or overcome. In a context where Melendez is almost constantly required to be, as Tobin Siebers puts it, both “cripple” and “super-cripple,” such leveling comments work to subvert these expectations, even if Melendez also actively plays upon them.Footnote 66

Exceptional Skill, Relatability, and Religious Belief

Although some scholars like Elisabeth Le Guin and Edward Said claim virtuosity creates an unavoidable gulf between the exceptional performer and the audience member, Melendez's relatability is key to his reception.Footnote 67 This notion of relatability is closely related to the function of the overcoming narrative: rather than demonstrating the inability of others, his performances are largely meant to provide an avenue through which audiences imagine their own potential actions. In some ways, Melendez's performances are thus open to critiques from recent disability activists and scholars who refer to representations of disabled people meant for the voyeuristic pleasure of others as “inspiration porn.”Footnote 68 In other ways, however, the term does not fit. Although individuals might attend to Melendez's performances in a way consistent with the practices of inspiration porn, Melendez is more personally invested and engaged in the process of his own self-presentation than the term implies. Furthermore, virtuosity, as Richard Leppert argues, often includes some form of voyeurism, such that spectators’ desires are both cultivated and “simultaneously transferred onto the spectacle of the Other” who “enacts the desires imagined.”Footnote 69 Thus whatever degree of voyeurism occurs in Melendez's performances is inflected by disability but not wholly resulting from it. Furthermore, Melendez at times directly invites his audiences to participate in this way. Towards the end of a small 2019 concert in northern Colorado he stated outright the implicit message of much of the performance: “If I can do this with my toes, just imagine what you can do.”

One way that Melendez maintains his relatability is by regularly downplaying his exceptional status. He rejects the idea that he is either particularly limited or gifted, admonishing in his book, “You could play the guitar with your feet if you were willing to practice hard enough.”Footnote 70 After all, it is not as if Melendez's lack of arms somehow produced his musical skill. The primary relationship between those two aspects of his embodiment is that Melendez's non-normative body socially sanctions his non-normative technique. In other words, his physical difference allows audiences to value his unusual skill as legitimate, impressive, and musically meaningful. If a musician with arms were to play with Melendez's technique, audiences would almost certainly see it as a shallow gimmick.

Melendez further secures his relatability by emphasizing the straightforward means by which he acquired his musical skill. Even if audiences insist that his playing is exceptional, Melendez is just as insistent that it came through ordinary means: “The other side of what I'm doing with the guitar with the toes, there still has to be the time, the practice. It's not like overnight I could just do it—No way. I had to take the time to learn the instrument, practice it.”Footnote 71 Such statements demonstrate a work ethic that is often central not just to the cultivation of skill but to the construction of virtuosity and its ethical undertones.Footnote 72 His audiences value his skill as unique and amazing, yet also as the result of dedicated, everyday labor.

Given the importance of religious identity and belief to Melendez and much of his audience, it might be surprising that he seems to take credit for his skill rather than directly attributing it to God. The narrative surrounding his skill, however, is a nuanced combination of what Peter Kivy outlines as the “myth of the possessor” and the “myth of the possessed.” In Kivy's account, the possessor claims greatness for himself—this myth is almost always masculinized—while the possessed is the vessel of some higher power, bestowed with greatness by God, nature, or the muses.Footnote 73 At the same 2019 performance referenced above, Melendez's brother and manager José took the stage to provide a Christian take on the myth of the possessed, telling the audience “when he started, it was awful. It was terrible . . . and then one day he started praying, and that's truly when the music came. I believe that the Holy Spirit came upon him and gave him this gift.” Tony Melendez's own emphasis on his hard work and everyday dedication seems difficult to square with such a narrative. When I asked him to clarify the relationship between God's work and his own labor, he simultaneously cited the necessity of his effort while crediting divine providence for the basic physiological structures of his left foot that allow him to play. Melendez was born with a clubbed left foot that required surgery, and after the procedure he found his second toe was longer than the first—a common variation in the foot's bone structure found in twenty to twenty-five percent of people.Footnote 74 Perhaps Melendez could have found other techniques without this feature of his left foot, but he describes it as “the only reason [he] can do minors and major sevenths.”Footnote 75 In this understanding, Melendez is both possessor and possessed; his hard work was possible because of God's providence, and he further implied that it was only fruitful because of God's presence. “I don't feel my craft, my music is that exciting,” he told me. “I'm not a flamenco guitarist. I'm just an armless guitarist. . . . But to be able to share [with] over a million people in front of you, not once but up to five or six times. How do you even get a gig like that? It's beyond my comprehension.”Footnote 76 Melendez's playing, then, is not a miracle in the sense of a temporally-bound divine act that alters the natural course of affairs, but as José Melendez told the audience: “We believe in providence in our faith. You're seeing a miracle tonight.”

Another aspect of Catholic belief and practice that can help clarify this particular interpretation of Melendez as both possessor and possessed is the concept of sacramentality, which theologian Richard McBrien considers “the major theological, pastoral and even aesthetical characteristic of Catholicism.”Footnote 77 The word sacrament likely calls to mind the seven official sacraments of the Catholic Church, which outsiders might simply think of as rituals. The Catholic understanding of a sacrament, however, is far more expansive. Augustine defined it as “a visible sign of an invisible grace,” and during the Vatican II council Pope Paul VI described it as “a reality imbued with the hidden presence of God.”Footnote 78 These descriptions certainly fit formal sacraments such as baptism and the Eucharist, but sacramentality extends to all life, such that “the Catholic sees God in and through all things: other people, communities, movements, events, . . . the world at large, the whole cosmos.”Footnote 79 A Catholic theological perspective views all these things—and Melendez's story—as instruments of grace. Interpreted in this way, the very human aspects of Melendez's story—the medical care, his father's guitar, the family support, the hours of practice—are not a mundane reality lacking evidence of the divine. They are constant, visceral evidence of God's presence, and Melendez's performances can be at once (and without paradox) an impressive show of attained skill and a moving example of God's grace.

Identity and Otherness, Merit and Power

Many aspects of Melendez's reception have remained consistent since the start of his career. Although he has written new songs and released multiple recordings, audiences still want to see the man who plays guitar with his feet so well as to move a Pope (who has now become a Saint). However, one aspect that has become far more prominent than it was in 1987 is the issue of ethnicity. The concert I attended in 2014 was put on by the leaders of the Spanish-language youth group of a local Catholic parish. When I asked one of the concert organizers why he had wanted to bring Melendez to their church, he referenced the story of him playing for the Pope and emphasized how important it was for Melendez to perform at an event that was first and foremost for the Spanish-speaking youth. He further explained how easy it was for the youth to feel like they were marginal to everything that happened in their broader community and even in their church. Melendez's personal narrative—emigrating to the United States from Nicaragua as a child, acquiring skill as a musician, and eventually playing for the Pope—made him a particularly potent model of agency for the youth who were given the best seats in the large sanctuary.

For those in attendance, Latinx identity was clearly based on shared language and ties to homelands in Latin America. Prior to the concert, one of the youth organizers called out the names of countries in South and Central America as people from those countries cheered to identify themselves. In this context, the overcoming narrative common to much of Melendez's reception took on more specific significance. The tickets to the event prominently featured the quote “no me digas que no puedes”—don't tell me that you can't—and early on in the concert, Melendez himself led a chant of “sí yo puedo!”—“yes I can!” Because, as David Mitchel and Sharon Snyder point out, disability so often serves as “the master trope of human disqualification,” the overcoming narrative becomes its mirror image as the master trope of human accomplishment.Footnote 80 Melendez's refusal to accept the social construction of his body as a fixed, wholly natural site of absence is a powerful performance of agency that maps onto other identities—of the first or second generation immigrant, of those for whom English is not their first language—that might be used to disempower them within the United States. None of this bypasses critiques of overcoming narratives. Indeed, it demonstrates how such narratives persist in demanding more from marginalized groups by prescribing individual improvement and effort rather than social and political change.Footnote 81

Shared ethnic identity and religious affiliation are important to much of Melendez's reception—he estimates that roughly 80 percent of his performances are for Catholic churches or organizations, and many of these request a bilingual program. However, these are certainly not the only avenues to recognizing and valuing Melendez's skill, and the degree of identification is flexible. Early in his career he played a great deal for evangelical Christians (largely because their worship format could more easily accommodate his performances than a Catholic mass), and he still plays in secular and corporate settings when invited. Even without taking online listeners into account, Melendez almost always appears at events to which he is invited, which means that his message and its interpretation gets shifted to a variety of contexts. As one example, when Melendez appeared as part of a fundraiser for a Denver-based Catholic volunteer organization in 2019, the message of service and outreach based on faith convictions overshadowed other potential meanings or points of shared identity. Regardless of the specifics of each context, however, audiences must find some balance between likeness and difference in order for the display of skill to be meaningful as a form of virtuosity. Religion and ethnicity can be grounds for empathy, but if nothing else, the performer must be perceived as a legitimate fellow subject in order for their performance to be moving. On the other side, the performer's persona must also display some form of otherness, which often takes the form of skill itself, but it can also be augmented through other forms of identity, as seen in Melendez's case.

Critic-centered discourses of virtuosity often make comparisons and expert opinions central to virtuosity, but the most fundamental comparison—and one rarely made explicitly—is with one's own experience of embodied subjectivity. As sociologists Schutz and Luckman argue: “The experience of the Other rests on the perception of the typical shape of a body, but it is not exhausted by that. The body I perceive refers to something I cannot perceive, but which I ‘know’ is co-present: an inwardness. . . . The Other person, whose body I perceive in experience, is from the first ‘like me’.”Footnote 82 From the critical perspective of disability studies, the potential problem of intersubjectivity is its basis in a presumed likeness. I encounter the other as another subject—always, inevitably—“like me.” Of course, the degree of divergence allowable in order to still be “like me” varies widely. Especially when working from a position of privilege and concomitant power in relation to others, gender or race alone can be enough to reduce this sense of intersubjectivity within a patriarchal or racist society. What virtuosity shares with the “freak show” practices of the twentieth century, as Straus outlines, is that both maintain this tension between likeness and difference, never fully resolving one into the other: “in exchange for the price of a ticket, audience members can stare (and listen intently), indulging in the simultaneously disquieting and reassuring contemplation of a human embodiment so like and yet unlike their own.”Footnote 83 For the most calloused observers, the different bodies presented on stage or via media might represent only an external object rather than a lived body. For others, however, much of the fascination stems from finding intersubjectivity—someone “like me” in some way or another—where the presence of bodily difference might otherwise lead them to dismiss or diminish such intersubjective connections.

When I asked Melendez whether it bothered him that audiences are fascinated with his basic approach to the instrument, he was matter-of-fact:

I would say every artist has his niche. That would be my niche. The shock of “he's using his feet!” I don't know if I'd be as popular or as well-received if I played with my arms. If I had the arms and I just played, I think music would have been harder. I don't know if I would have had a moment to sing for the Pope. I don't know if the Pope would have jumped off the stage to come and kiss me if it wasn't a guy with no arms playing the guitar with his feet. It's hard to really know, I really don't know, but I would say it would be different than it was, if I had arms standing up playing the guitar, singing. I think he would receive it, yes. Enjoy it, maybe? But a guy playing the guitar with his feet, it's like, “no way, that can't be happening.”Footnote 84

Defenders of meritocratic evaluation might argue that Melendez is selling himself short, or that people should appreciate his music purely for its sonic qualities and willfully ignore how he plays the instrument. But that is simply not what his audiences do. The feet and the music, the aesthetics of sound, the Papal kiss, the ethics of human effort, and the sincerity of religious commitment are all productive aspects of the experience that carry correlate forms of value for Melendez and his audience.

The potential importance of multiple aspects of identity to virtuosity—being disabled, or Catholic, or Latinx—strikes at the heart of the myth of meritocracy by undermining the presumed chasm separating identity and skill. The myth of meritocracy holds that “individuals get ahead and earn rewards in direct proportion to their individual efforts and abilities.”Footnote 85 The prevalence and pull of this myth can hardly be overemphasized; William Cheng describes it as an “American power ballad” that “implicitly poses as the rule of law in employment, academia, popular culture, and everyday life.”Footnote 86 Within this hegemonic discourse, identity and skill emerge as distinct or even opposed concepts: whoever plays best is (or at least ought to be) revered, regardless of who they are. One has nothing do with the other. This ignores real structures of prejudice and unequal access to resources while also obscuring the actual social nature of merit. For although we may imagine it as something adhering to people regardless of their identities, merit is not so anonymous or impartial. In general, the quality, legitimacy, and ultimate meaning assigned to any skillful act correlates to those same aspects of a particular identity in a given time or place. Not only do audiences care about the composite subject position from which Melendez displays his skill, but skills quite literally “embody a whole cultural interpretation of what it means to be a human being.”Footnote 87

This is not to say that Melendez's identity and skill can be collapsed into one another, but that they cannot be considered in isolation. Attempting to foreground skill over identity ends up covertly addressing both, as in the current US administration's claims that most (implicitly Latinx) immigrants lack the skills to live in the United States.Footnote 88 Melendez's performance of legitimate, valuable skill—especially when combined with his insistence that he is not exceptional—can counter those who would deny the legitimacy and value of various aspects of his identity. The relationship between skill and identity is neither one of simple dichotomy nor straightforward equivalence, but completely separating the two remains impossible, because discourses and practices of skill and subjectivity each subtend the other.

This connection between skill and identity is one reason why the display of skill provides such a powerful opportunity for the exercise of social power. The anthropologist David Graeber identifies the two basic types of social power as “the power to act directly on others”—which is often coded as masculine—and “the power to define oneself in such a way as to convince others how they should act toward you,” which is often coded as feminine. In virtuosity, both these forms of power are at play, although one may predominate. The actions of musicians move audiences while simultaneously performing a persona that influences the actions and attitudes taken towards those musicians. The first type of power “tends to be attributed to the hidden capacities of the actor,” whereas the second results from “visible forms of display,” and this is ultimately the source of their gendered associations.Footnote 89 The presumed agent behind such “hidden capacities” is the ideological construct that Judith Butler identifies as “disembodied ‘man.’” Locating masculinity outside the sphere of embodiment promotes it as unmarked and universal, while also positing its opposite: “the corporeally determined ‘woman.’” The second form of power is thus feminized because the corporally determined woman is constantly visible—she can do nothing but display her body. Within this ideology, women are precluded from utilizing the first type of power because “women are their bodies,” which, as Butler notes, is distinct from “living one's body as a project and a bearer of created meanings.”Footnote 90

Melendez's gender would appear to sanction his exercise of the first type of power, but disabled people are often treated as “ungendered and asexual,” and the social construction of disability enacts a similar tendency to reduce one to one's body.Footnote 91 Just as women are rendered almost constantly visible through the emphasis on their bodies, people with disabilities are rarely allowed to choose the contexts and terms of visual display. They regularly become objects of the normative “stare,” which Rosemarie Garland-Thomson defines as “an urgent effort to explain the unexpected, to make sense of the unanticipated and inexplicable.”Footnote 92 Yet if staring is persistent and even unavoidable, Garland-Thomson suggests that it may also be productive. Instead of avoiding stares, we should reflect on how we might use them: “the question for starers is not whether we should stare, but rather how we should stare. The question for starees is not whether we will be stared at, but rather how we will be stared at.”Footnote 93 For Melendez, musical performance provides multiple ways of putting audiences’ stares to use, conveying his religious convictions and partially disrupting the ideologies that would divide forms of power along neatly gendered or ableist lines. He does not overcome or transcend his body in an act of masculine disembodiment, but neither is he reduced to it. Instead, he lives his body, publicly undertaking musical labor that enacts both forms of power, acting on others and projecting a complex social identity that is inseparable from religion, ethnicity, and disability without being reducible to them. Performance allows him to present a view of human creative agency—mediated through his faith that his acts may serve as instruments of divine grace—and to negotiate the public meaning of his bodily difference. Contrary to the representational practices that code disability as passivity or absence, Melendez exercises musical agency not as entirely free and unfettered but as complexly embodied virtuosity: skill made apparent and socially meaningful for both himself and his audiences.