In the closing moments of Cool Hand Luke (Jalem Productions and Warner Bros., 1967), the title character crouches by a lake, furiously filing his ankle irons. He has escaped from prison yet again and with him is Dragline, a fellow inmate who joined in the breakout. Dragline idolizes Luke and praises him for concocting such an ingenious plan to fool the guards. But Luke laughs and retorts, “I never planned anything in my life.” This statement from Luke is fitting, as he demonstrates repeatedly throughout the film that he thrives in the moment, unafraid of consequences.

While Luke's line captures one of Cool Hand Luke’s larger themes, it also serves as a useful introduction to the film's intriguing music. The soundtrack features traditional American music selected by director Stuart Rosenberg (1927–2007) and original music composed by Lalo Schifrin (b. 1932), and it emerged over an intense nine-month span in 1966–67, during which time ideas flowed freely and original plans changed significantly. Rosenberg and Schifrin were the primary musical architects, although others contributed along the way, including screenwriters, actors, producers, folk music experts, and a trio of banjo players. The entire project was a testament to collaboration and to Rosenberg and Schifrin's willingness to recognize and seize artistic opportunities. More importantly, the resulting soundtrack, much like Luke's character, had depth. It complemented the film in powerful ways through a clever balance of tradition and innovation. Schifrin's portion even earned an Oscar nomination for best original score.

Cool Hand Luke appeared at an interesting moment in American film music history, when the options for film scoring were particularly broad. On the one hand, the classic scoring model (neo-Romantic, orchestral underscoring) continued to have a presence. But more significantly, a tremendous diversification in scoring techniques had been unfolding since the late 1950s, as jazz, pop, folk, and electronic music worked their way into scoring strategies.Footnote 1 The reasons for this development were complex and tied to shifting aesthetics of the period, an enormous emerging teen market, and larger institutional changes. The collapse of the studio system had produced a new reliance in Hollywood on freelance directors, composers, and instrumentalists—many of whom had strong ties to commercial and concert music. Meanwhile, the sixties saw the bond tighten between the film industry and the record business. All of the major film studios owned record labels, which meant catchy theme songs, links to recording artists, and soundtrack albums had a continuous presence in film scores throughout the decade.Footnote 2 These conditions, along with advances in sound technology, would eventually yield the compilation score, a model based solely on the use of previously recorded music.Footnote 3

Cool Hand Luke was created in the thick of this period of musical diversity. In fact, its release coincided with the release of The Graduate (Embassy Pictures, 1967), a film now considered seminal in the era's more progressive trends.Footnote 4 The Graduate’s specific novelty was the manner in which it used music by the folk duo Simon and Garfunkel to depict the inner psychology of the film's lead character.Footnote 5 Cool Hand Luke was in production at the same time as The Graduate and exhibited similar creative tendencies. Its initial musical plan focused on securing a contemporary folk artist to write and record an original song for the film.Footnote 6 A comprehensive list of candidates was compiled, and Canadian folk star Gordon Lightfoot was selected. Lightfoot delivered his song to Warner Bros. in the fall of 1966; however, unlike in The Graduate’s case, Cool Hand Luke’s connection to hip young recording artists did not come to be. Soon after shooting began in September 1966, Rosenberg abandoned the Lightfoot song in favor of other musical ideas more organic to the production. Some of those ideas came from Schifrin, whom Rosenberg had brought into the fold in August. Others came from within the shooting process itself, from the actors and the crew. This dynamic situation forced Rosenberg and Schifrin to reckon with how these various ideas might add up to something meaningful. This line of thinking ultimately shifted the film's music in a more conservative direction.

The soundtrack Rosenberg and Schifrin created has received little attention, a surprising fact given the film's popularity and music's importance within it. Cool Hand Luke ranked among the 1967–68 season's most successful movies, earning four Oscar nominations (Newman for Best Actor, George Kennedy for Best Supporting Actor, Pierson for Best Script, and Schifrin for Best Original Score). It remained in movie theaters for nearly five years after its release and then transitioned seamlessly to television as a popular movie of the week. By all accounts, it spoke to a broad audience. John Allen of the Christian Science Monitor aptly summarized its effect when he described the film as “an assertion of a certain basic dignity in man, a certain spirit which cannot be broken, no matter what the circumstances.”Footnote 7 Luke's unorthodox rebelliousness particularly resonated with young audiences, and reports surfaced within a year of the film's release of students in the United States and servicemen in Vietnam imitating the famous “egg-eating scene.”Footnote 8 The film's dialogue even seeped into the American lexicon. As early as 1971, sportswriters adopted the phrase “Cool Hand Luke” to describe a particularly gutsy performance by an underdog athlete, a reference that continues today often untethered from its original reference point.Footnote 9 The signature line, “What we've got here is failure to communicate,” has had a similar fate.Footnote 10 As time passed, the film also drew the attention of scholars from a range of disciplines, who analyzed the film's religious symbolism, political relevance, commentary on the penal system, and psychological insights.Footnote 11 Yet these many articles, popular and scholarly, are largely silent about the music, this despite music's role in the plot. Luke is an amateur musician, his most prized possession is a banjo, and his fellow inmates often turn to music. The film includes several extended musical scenes, highlighted by Rosenberg's direction and expertly shot by cinematographer Conrad Hall.Footnote 12

This study offers the first detailed inquiry into the Cool Hand Luke soundtrack: its features, its origins, and its creative gestation. My research is drawn from a wide range of primary sources, including documents and correspondence in the Warner Bros. archive at the University of Southern California, interviews with individuals involved in the production, the voluminous popular press about the film and its creative principals, and the film itself. Along the way, I examine the larger issues that came to influence the music as it moved from concept to final recording, particularly the thorny concept of authenticity, which served as a backdrop for many of the initial behind-the-scenes musical discussions. I also provide insights into the working methods and innovations of Rosenberg and Schifrin, two sharp young Hollywood minds in the mid-1960s who deserve more attention in the scholarly literature.

Preliminary Plans: Rosenberg's Inspiration and Schifrin's Pitch

In late summer 1965, Rosenberg stumbled upon a recent novel, entitled Cool Hand Luke, by a former chain gang prisoner, Donn Pearce.Footnote 13 The book told the fictional tale of an American war hero named Lukas Jackson, who commits an act of petty vandalism and is sentenced to two years on a brutal Florida chain gang. Luke refuses to conform to the prison rules, and his actions ultimately cost him his life. But along the way he fights the system in clever ways and becomes a folk hero to his fellow inmates. Rosenberg was an avid reader and student of literature, and the novel captivated him. He later reflected, “It was the first time I had come across an existentialist hero—not an anti-hero—in American literature. Here was a man not so much a rebel as a nonconformist, a man who didn't belong, committed to no external idea, but to himself, and desperately concerned to express that commitment.”Footnote 14

At the time, Rosenberg was thirty-eight and a successful television director, due to his work with the hard-hitting crime series The Defenders (CBS), Naked City (ABC), and The Untouchables (ABC). He was itching to direct a feature film, however, and Pearce's book seemed the perfect vehicle. Rosenberg sketched a plan and shopped the idea to a few actor friends. One was Felicia Farr, whose husband, famed actor Jack Lemmon, had a small production company (Jalem Productions). Lemmon liked the idea, and Jalem Productions quickly bought the rights to Pearce's novel in August 1965.Footnote 15 Within a few months, a talented young television writer, Frank Pierson, was hired to write the screenplay.Footnote 16 But the project's real turning point came in May 1966, when actor Paul Newman agreed to the title role. Warner Bros. soon after bought the distribution rights, and the production moved forward swiftly.Footnote 17

Music was clearly on Rosenberg's mind from the outset of the project. Pearce's novel was rich in musical imagery and references to American folk music, and indeed the early correspondence at Warner Bros. suggests that folk music was initially the only kind of music being considered for the film.Footnote 18 As the script took shape in late summer 1966, however, Rosenberg wondered if that concept was too narrow. He began considering other musical options. It was this process that brought Schifrin to his attention. Like Rosenberg, Schifrin was in the formative stages of his Hollywood career in 1966, and in many ways his star was ascending at a faster rate. Schifrin had come to California a few years earlier from New York City, where he had had significant success as a jazz pianist and arranger. His jazz training extended back to his native Argentina and to Paris, where he gigged in jazz clubs by night and studied classical composition at the Paris Conservatory by day. Schifrin worked with the biggest jazz musicians of the late 1950s, most notably Dizzy Gillespie, who hired him in 1956 as pianist and arranger for his big band. Schifrin also played in Gillespie's quintet in the early 1960s. During this same span, Schifrin recorded several solo jazz albums on various labels (Epic, Roulette, Verve, and MGM). The close alignment between MGM Records and MGM Studios led to Schifrin's first Hollywood scoring opportunity: in 1963 MGM offered Schifrin a contract to score the film Rhino!.Footnote 19 He moved to California and soon found other scoring jobs. Within two years his musical credits included several hit TV shows (e.g., Man From U.N.C.L.E., Big Valley, and Mission Impossible) and a handful of big budget films (e.g., The Cincinnati Kid, Once a Thief, and Murderers’ Row). Schifrin's jazz-infused style, most popularly captured in his 1966 theme for Mission Impossible, even gained him national radio airplay and an eventual Grammy.Footnote 20 Meanwhile he also had an impressive classical music résumé. He had studied composition with Charles Koechlin and Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatory, and by the mid-1960s he had several published works. The same month as his interview for the Cool Hand Luke job, in fact, he conducted the premiere of one of his works at the Hollywood Bowl.Footnote 21 Rosenberg was aware of Schifrin's diverse skills and requested that the young composer be added to the list of interviewees for the Cool Hand Luke score.

To prepare for the interview, Schifrin did some research and learned that Rosenberg was considering a wide range of options, from folk singers to country songwriters to traditional film composers.Footnote 22 After reading the script, he understood why. Cool Hand Luke had clear references to the American South and American folk music, but it also presented universal themes of non-conformity, perseverance, and individual freedom. Schifrin considered whom he was competing against for the job and decided to pitch the idea of a middle path. He later recalled, “I said [to Rosenberg,] you have three possibilities here. One is to hire a folk musician or somebody who is into the country bluegrass style. Or you could go to the other side, very, very Americana and symphonic, like Copland. But I propose a third possibility, which is a combination of both.”Footnote 23

He assured Rosenberg that he could compose a score for Cool Hand Luke that “blended” folk, country, and orchestral music in a fresh and artful way. Rosenberg liked the concept and soon after the interview Schifrin was hired to score the film. Both men understood that they would have to work together to make the idea a success. After all, Rosenberg had already identified several pieces of traditional American music to use diegetically.

Phase One: Musical Adaptation, from Novel to Shooting Script

It is not surprising that traditional American music was Rosenberg's first inclination for Cool Hand Luke’s music because the material clearly pointed in that direction. Pearce's book, for example, was steeped in folk music references. A vivid example occurs in chapter 12, when Luke's dying mother (Arletta) visits Luke in prison. Arletta brings Luke a few objects from home, including an old banjo. As the chapter unfolds, Luke's fellow inmates are stunned to learn that Luke can actually play the instrument, apparently quite well:

[Luke sat] on the floor cross-legged by his bunk, his feet and his chest both bare, his eyes closed and his head tilted backwards, a tiny smile on his lips which were parted just enough to reveal the white of his teeth. And as Luke fondled those vibrant threads his face underwent a transformation, his hard and youthful handsomeness beginning to assume a glow. Slowly he became two selves, his hands undertaking a life of their own while the rest of him drifted away.Footnote 24

Up to this point in the novel, Luke's inner thoughts—particularly his reasons for his run-ins with the law and his inability to conform to society's rules—have remained largely hidden. But with the banjo in his hand, Luke opens up:

And he would sing, his voice droning as if inspired by some distant source, his flying fingers going on with their melody. Then he might repeat what he just said. Or make noises, throw in odd words which were not meant to be sentences but which kept up the syncopated rhythm of his voice, half-talking in a mocking chant that alternated in pitch and intensity and became a king of song, a kind of Talking Blues of a style and nature all his own.Footnote 25

What follows is a detailed description of Luke performing a sprawling “talkin’ blues.” This particular genre had deep American roots and was perhaps most closely associated with Woody Guthrie, who used it extensively in the 1940s. But in 1965, Pearce was likely angling for a more contemporary parallel: Bob Dylan, who had revived the talkin’ blues form on his debut album Bob Dylan (Columbia, 1962) and his highly successful follow-up album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (Columbia, 1963).Footnote 26

The talkin’ blues form—which consists of rhythmically spoken lyrics over a simple, repeating chord progression—presented Pearce with a useful literary device because of its text-driven nature. The form's ultimate punch occurs when its simple lyrical patterns are disrupted or extended, typically at the end of a verse while the harmony lingers on the progression's penultimate chord. In the novel, Pearce made no references to the chords Luke may have been strumming, but the notion of stretching the lyrical patterns was quite apparent. The talkin’ blues extends for multiple verses, as Luke reflects on his troubled family life, the horrors he experienced in the military, and hypocrisy in religion and society. His dark message, however, is sarcastically upbeat, true to the form's tradition of what Alan Lomax called “cynical humor.”Footnote 27 Each verse concludes with a refrain about “playing it cool.”

Come on you little fellas and gather around and your Uncle Luke will tell you all about the war. The big war. When everything went boom boom. And it also went—bang bang. And sometimes even—ka-zowie!

But just remember. You gotta play it cool.

Course I had to kill a couple fellas here and there. Killin’ was my job. And my daddy always used to tell me to do a real good job. Him bein’ a preacher and all, carryin’ the Word, I always did what my daddy said. Got to be pretty good at it. Got promoted. Got to be a corporal.

But you gotta be cool. That's part of the job.Footnote 28

The talkin’ blues passage lasts for nearly ten pages and is some of Pearce's strongest writing in the novel. It was likely the portion that got Rosenberg thinking about incorporating authentic folk music into the script.Footnote 29

Another important musical factor emanating from Pearce's novel was the story's setting. Prisons in the United States the first half of the twentieth century, particularly the chain gang camps of the South, teemed with musical tradition. Prisoners used songs to pace their backbreaking labor, often drawing upon work songs laborers and slaves had sung for decades. Music also had a presence in the prison barracks. As the Lomax field recordings of the 1930s and 1940s documented, prisoners sang everything from folk ballads to spirituals to country blues.Footnote 30 Pearce referenced this rich musical context throughout the novel—a timely tactic for 1965. Folk music had been experiencing a booming popular revival since the late 1950s, and prison music specifically was widely collected, recorded, and performed by a host of artists from Pete Seeger to the Kingston Trio to Peter, Paul, and Mary. In 1960, Harry Belafonte earned a Grammy for his recording of chain gang songs: Swing Dat Hammer (RCA Victor, 1960). Josh White had similar success with his album Chain Gang Songs (Elektra, 1958), which was rereleased several times in the 1960s.

Prison music also had a history on the big screen. Hollywood had been making prison movies since the 1930s, ranging from Disney's Mickey Mouse short The Chain Gang (1930) to John Frankenheimer's Birdman of Alcatraz (1962). Work songs were frequently included, such as in Mervyn LeRoy's hard-hitting I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), in which amidst the pounding hammers in a rock quarry a prisoner sings out the opening phrase of “Raise ’Em High, Workin’ All the Live-Long Day” and is answered by his fellow inmates as they swing their hammers in unison. Prison films also showed inmates using music in other, more personal, ways. In Jules Dassin's tragic film noir Brute Force (1947), for example, a lonely prisoner from Trinidad sings calypso songs to ease his homesickness. Similarly, in Stanley Cramer's The Defiant Ones (1958), Noah Cullen (played Sidney Poitier) quietly hums W. C. Handy's blues “Long Gone” after Cullen and fellow inmate Joker Jackson (played by Tony Curtis) have successfully eluded their prison captors. These kinds of musical references enhanced the believability of the setting and the characters, but they needed to be treated carefully. Music was a tightly controlled privilege in prisons, therefore too much music could easily undermine the film's realism.

Rosenberg and the writers who adapted Pearce's novel understood this razor's edge. The best record of their thinking is captured in an important document in the film's production history: the shooting script, a copy of which survives in the Claire T. Carney Library at the University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth. A shooting script is a detailed production plan, which includes all of the actors’ lines and blocking as well as technical details about each shot, camera angles, shot types, and a shooting schedule. The Cool Hand Luke shooting script was a collaborative effort among Rosenberg, screenwriter Frank Pierson, and several other writers, including the novel's author, Donn Pearce.Footnote 31 It was completed on 29 September 1966, a week before rehearsals began on 3 October. It was revised twice mid-production (18 November and 2 December)—an important reminder that the creative process was ongoing.

Compared with the novel, the Cool Hand Luke shooting script has far fewer musical references. No talkin’ blues appear, nor is music mentioned in the lengthy explanatory paragraphs about Luke's character at the start of the script. The banjo remains an important prop, but the script only asks Luke to play it once (calling for an unspecified “slow hymn” in the scene following his mother's death).Footnote 32 Luke's only other musical direction is the scene of his solitary confinement, which calls for him to sing a “protest song.” Similar musical restraint is applied to the rest of the prisoners. Only one scene calls for the chain gang to sing a work song. This relatively conservative musical plan is a distinct departure from the novel. Yet at the same time, the shooting script reveals that the writers had identified one particular moment in the film that was musically significant. For the scene of Luke's unconventional protest during the tarring of a road, the shooting script calls for a “song on the soundtrack” to accompany the action.Footnote 33

According to correspondence in the Warner Bros. archives, Rosenberg and Carroll had already planned to commission a contemporary folk song for this scene before the initial draft of the shooting script was completed in September 1966. The August correspondence discusses a short list of songwriters under consideration—Gordon Lightfoot, Jack Elliott, John Hammond, Jr., and Pete Seeger—all prominent folk artists at that time. The Warner Bros. Music Department weighed in on the choice, and Lightfoot, a young Canadian who had released a highly successful debut album (Lightfoot!) in January, was selected.Footnote 34 The idea of a folksinger contributing to the soundtrack was not necessarily a novel move. Title songs were practically standard practice in Hollywood in the mid-1960s, and there was a long tradition of using folk and country singers to sing the title songs of westerns.Footnote 35 But this particular “Song on the Soundtrack” was not necessarily in the same vein as a title song. It was slated for an internal scene and for use as non-diegetic music. Given the folksingers on the short list, the hope may have been for a song that had a political or social edge to it.Footnote 36

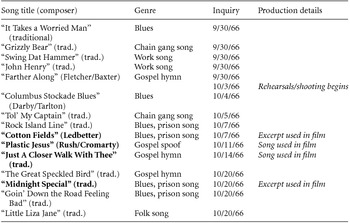

In mid-August 1966, Carroll finalized the Lightfoot commission and sent him a contract. Several weeks later (after shooting had begun), Lightfoot sent Warner Bros. a newly composed song entitled “Too Much To Lose.” The song never made it into the film, however, because in the intervening weeks the musical landscape of the Cool Hand Luke project shifted.Footnote 37 In part, the shift was likely fueled by indecision on Rosenberg's part. In October, he sent a flurry of requests to the Warner Bros. Music Department seeking copyright clearances for a variety of traditional American music (Table 1). The list consisted solely of American blues, prison songs, and gospel songs. The songs indicated in bold were ultimately used in the film. In addition, once rehearsals and shooting began, Rosenberg discovered new musical ideas within the project itself. He learned that one of his actors, Harry Dean Stanton (cast as Tramp), was also an accomplished singer and guitarist who had gospel music experience.Footnote 38 Rosenberg contemplated how he might insert Stanton's skills into the production. Also on the set during rehearsals, Rosenberg overheard a humorous song, “Plastic Jesus,” which struck him as ideally suited for the film.

Table 1. Initial copyright inquiries for songs for Cool Hand Luke, September–October 1966.

More importantly, Rosenberg had his first opportunity in these early days of rehearsal to interact directly with Schifrin. He invited the composer to the set, and the two watched the daily rushes together and discussed ideas for the score. They developed a strong personal rapport and an understanding of each other's vision for the film. They also discussed how Schifrin might blend the traditional American music Rosenberg was now considering into the score. Schifrin was so inspired that he even composed a melody on the set, notably the tune that would later become Luke's principal theme (Example 1).Footnote 39 The discussions also yielded a more clearly defined division of labor. Schifrin naturally assumed the lion's share of the musical responsibilities (all of the underscoring and source music as needed). He returned to his studio in Los Angeles in mid-October 1966 with a good sense of the kind of music he wanted to compose.Footnote 40

Example 1. Opening bars of Schifrin's melody (Luke's Theme) composed on the set in October 1966. Transcription by author.

With Schifrin's responsibilities in place, Rosenberg now narrowed his musical focus to just a handful of scenes in which he wanted the actors to hum, play, or sing music. He soon encountered a legal snag, however, as well as a few new options.

Phase Two: Copyright, Authenticity, and “Plastic Jesus”

All copyright inquiries for the Cool Hand Luke project went through a central office in the Warner Bros. Music Department, a division called the Music Publishers Holding Corporation (MPHC), which secured clearances and negotiated any necessary fees. Rosenberg submitted most of his musical suggestions to the MPHC in September and October 1966, and because most of the songs were traditional in origin, the hope was that most—if not all—were in the public domain. But complications emerged. The crux of the problem was documented in an October 1966 memo between Warner Bros. employees Helen Schoen and Lois McGrew, who worked on the copyright issue for the Cool Hand Luke project. Schoen wrote in response to Rosenberg's requests for clearances for “The Great Speckled Bird,” “Grizzly Bear,” “Midnight Special,” “Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad,” and “Rock Island Line,” and explained that the searches were proving to be problematic: “[T]he current folk song fad has brought out dozens of versions of each of the[se] compositions and in checking one against the other we find there have been some changes musically and lyrically on each of these copies and we have been unable to pinpoint one old enough to authorize its use[.]”Footnote 41 According to Schoen, this problem was a rising challenge in the industry. She noted that the MPHC had encountered it from the other side of the equation as the publisher for Warner Bros. Records (another Warner Bros. subsidiary whose signature act was Peter, Paul and Mary) and commented, “We have published quite a number of folk songs and have had quite a number of lawsuits. This also holds true of practically every publisher in this field.” Schoen suggested that the only real solution to the problem in the short term was to hire an outside folk music expert.Footnote 42

Producer Gordon Carroll learned of this thorny issue in mid-October and in consultation with Rosenberg contacted Ed Kahn (1938–2009), young professor at UCLA and a respected scholar of American folk songs and country music. Kahn had co-founded the John Edwards Memorial Foundation (JEMF), a pioneering organization dedicated to the study of twentieth-century American folk music.Footnote 43 Before soliciting Kahn's help, however, Carroll learned that Rosenberg had three specific needs for Kahn to research: 1) a song for Luke to sing in the opening moments of the film as he commits the act of vandalism that lands him in prison; 2) a protest song for Luke to sing in solitary confinement; and 3) a song for the chain gang to sing while working on the road. Carroll wrote to Kahn, asking if Kahn could recommend public domain songs that would be “appropriate” for these scenes.Footnote 44

Kahn agreed to serve as a consultant for the film, and his inclusion in the project was a notable attempt by Rosenberg and Carroll to be attentive to the authenticity of the story they were telling (although likely the Warner Bros. legal department was pleased as well). Kahn's input did not necessarily simplify the problem, however. While only a few letters from Kahn survive in the Warner Bros. archives, relevant content is preserved in the office correspondence such as a note from Kahn to associate producer Carter DeHaven, Jr., about the film's opening song. Kahn had sent Rosenberg several recordings of suggested songs that were “traditional, acceptable, and appropriate for the time and setting.”Footnote 45 But in his note, Kahn also emphasized that the lyrics sung on those recordings must not be used; instead, he provided alternative, public domain lyrics. Kahn's message was clear: using traditional music required careful planning and detailed research. This requirement in turn meant time, something Rosenberg did not have in abundance now that shooting had begun.

As the rehearsals and shooting unfolded, this concept of authenticity continued to gnaw away at Rosenberg. After all, it was a central aesthetic issue in Luke's story. Luke was an “existential hero,” a man struggling to persevere as a free individual in an indifferent, brutal society. In order to communicate that concept effectively on screen, Rosenberg needed Luke's words, his actions, and even the music around him to be understood by the viewer as honest, as real, and as authentic. Yet, as the MPHC's copyright inquiries illustrated, authenticity could be a slippery concept.

Numerous scholars have examined the question of authenticity, particularly as it pertains to American roots music, and it is clear that the quest to articulate authenticity often says more about the power structures surrounding the music than it says about the music itself.Footnote 46 As Richard Peterson notes, authenticity is “a socially agreed upon construct.”Footnote 47 Moreover, it often carries with it a power dynamic, as Joli Jensen points out: “Invoking the concept of authentic or real or genuine anoints some things as good, pure, and true, while denigrating others as bad, corrupt, and false. It offers a way of bestowing virtue on some forms while denying it to others.”Footnote 48 But who decides? What makes this issue so relevant for Cool Hand Luke is that this sort of debate fit neatly with Luke's character. Luke was someone who questioned the rules, particularly ones he considered arbitrary. His whole life had been spent on the run largely because the institutions around him (his family, religion, the military, the justice system, the inmate hierarchy) had used the rules to control him. Yet he refused to be broken by the system. He had become so used to this pattern that he seemed to make a game of thwarting the rules.

During rehearsals, Rosenberg stumbled upon a musical way to show this rebellious side of Luke's character. It came in the form of an irreverent gospel spoof, “Plastic Jesus,” which Rosenberg had overheard a crewmember singing on the set. The song was an up-tempo parody of a revivalist praise song, touting the value of plastic icons for one's car. The song had multiple verses, but the two that caught Rosenberg's attention were about Jesus and the Virgin Mary:

Rosenberg quickly sent a request to the MPHC for clearance to use the song in the film. It took several months to secure, primarily because the MPHC struggled to find the correct author. The search was complicated by the fact that there were at least three different versions of “Plastic Jesus” in circulation. Bruce “Utah” Phillips, Ernie Marrs, and the folk duo the Gold Coast Singers had all claimed it.Footnote 50 The MPHC eventually determined that the version in question was from the Gold Coast Singers 1962 comedy album: Here They Are! (World Pacific Records). “Plastic Jesus” was part of a skit the group created about a radio evangelist. The song was a jingle for a fake company selling affordable (and practical!) religious icons for your vehicle.

Once Rosenberg discovered “Plastic Jesus,” the question then became what to do with it. The shooting script had originally called for just two musical moments for Luke to perform—a protest song during his solitary confinement and a hymn for him to play on his banjo following his mother's death.Footnote 51 Rosenberg decided to modify this plan and make “Plastic Jesus” Luke's sole musical performance in the film. He scrapped the protest song entirely and inserted “Plastic Jesus” into the scene when Luke learns of his mother's death.

In the scene, Luke hears the news and silently walks back to his bunk, takes up his banjo and starts to sing slowly. In the final version of the film, Newman delivers a compelling, although slightly confusing, version of the song. “Plastic Jesus” seems at first to be a distant memory for Luke, which he struggles to remember as tears well up in his eyes. After the first verse, he pauses briefly then dives into the second verse with great energy. His performance suggests that a grieving Luke is seeking spiritual solace by turning to a meaningful song from his past—in some ways, not a particularly surprising action. But it is important to note that up until this point, Luke has not played the banjo in the film. In fact, the viewer has been given no indication that the instrument is anything other than a prized possession from his past. Moreover, the choice of “Plastic Jesus” as Luke's vehicle of expression raises many questions. Is Luke earnestly seeking comfort in a satirical song? Or is he tossing a barb at religion? To the viewer knowledgeable of the Gold Coast Singers version, the meaning is even more contorted. Here is Luke in his hour of utmost need passionately singing a song that is a fake!

Actor George Kennedy (who played Dragline and was in the scene) added yet another complicating layer to the song. In a 2008 interview, Kennedy recalled that part of the raw power of Newman's performance came from Newman's own frustration with the banjo. He explained, “Paul knew as much about playing a banjo as I know about making cakes, which means very, very little. But he wanted to play his own accompaniment, and director Stuart Rosenberg and everybody else said, ‘You don't learn to play banjo that easily.’ And he said, ‘No, I'm going to try.’” Newman struggled to master the instrument and, according to Kennedy, it was frustration, not necessarily Rosenberg's direction, that shaped the “Plastic Jesus” performance: “[In] the scene you see, Paul makes an error [on the banjo]. He wasn't doing it the way he wanted and became madder and madder . . . although you can only [tell] by the increase of the pace of his picking the banjo. When it was over, it was magnificent. Rosenberg said, ‘Print.’ Paul said, ‘I could do it better.’ Rosenberg said, ‘Nobody can do it better.’ And that's the way that came off. True story.”Footnote 52 This raw, organic musical performance aptly captured Luke's authentic spirit.

This kind of organic musical expression was something Rosenberg sought to include in other parts of the film as well. For example, while rehearsing the scene of Arletta's visit, Rosenberg discovered that the scene presented a good opportunity to incorporate Harry Dean Stanton's musical skills. In the original script, no music had been slated for the scene and for good reasons: it was a dialogue-driven scene, perhaps the most powerful in the entire film—Arletta's emotional farewell to her son. Terminally ill, she arrives at the prison in a makeshift hospital bed in the back of a pick-up truck. Luke comes to her side, and they talk of his struggles to find his way in life and his run-ins with the law and society. Arletta is pained by her son's troubles and blames herself, but Luke warmly absolves her of any guilt. He simply doesn't fit in, he explains. Musical underscoring might overdramatize this kind of scene, but Rosenberg decided on the set that diegetic music from Stanton could be an effective complement.

The scene is set on a Sunday, when the inmates could rest and were allowed to entertain themselves. Rosenberg placed Stanton's character (Tramp) in the prison yard, strumming his guitar and ostensibly singing a hymn for his own edification. The gospel hymn “Just A Closer Walk With Thee” was selected, and it may have been Stanton's choice. Given the time constraints, Rosenberg certainly needed something Stanton could perform with little rehearsal. Whatever the reasoning, Rosenberg quickly submitted “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” to MPHC for clearance. He also sent a makeshift recording to the MPHC of Stanton singing it on the set, and sent a copy of that recording to Kahn as well.Footnote 53 Kahn subsequently approved Rosenberg's intended use of the song.

The inclusion of “Just A Closer Walk with Thee” in this scene proved to be a clever move. It not only framed the important dialogue, but it also added thoughtful counterpoint. The hymn's refrain and second verse are heard most clearly, and the initial implication is that religion might be the solution for a lost soul like Luke:

And yet, as the scene concludes, the hymn's sentiments ring hollow. None of the dialogue suggests that religion is the answer for Luke or Arletta. In fact, readers of Pearce's book would have noticed a stinging contradiction because in the novel Luke's father was a crooked evangelical preacher. The film's script avoids this backstory, but organized religion is a frequent target. The characters who call on God for help are often left without answers. Likewise, those who espouse deep religious beliefs, such as the guards assigned to punish Luke, are painted as hypocrites. In the Arletta scene, Rosenberg underlines this theme by concluding the scene with an uncomfortably tight close-up of Tramp singing the final strains of “Just A Closer Walk With Thee.” The smothering image of Tramp's mouth mapped onto the hymn's message of salvation captures the tensions that undergird the scene (and the entire film)—tensions between individuals and institutions, rebels and followers, and freedom and constraint.

In part, Rosenberg's insertion of “A Closer Walk With Thee” worked so effectively because the song and the actor performing it were believable from both a historical and a contextual perspective. Believability was crucial to the story he was telling. The characters may have been fictional, but the novel had been inspired by Donn Pearce's experiences on a real chain gang. The film's power hinged the verisimilitude of that context. The production history of Cool Hand Luke, in fact, showed an ongoing attention to this notion. The film's detailed set, for example, in California's rural San Joaquin County just north of Stockton, was so convincing that all twelve of its buildings were mistakenly condemned before shooting began—a local building inspector thought the fake prison was an abandoned migrant worker camp. In the same spirit, the studio brought in Spanish moss from Louisiana to help transform the California trees into plausible Deep South vegetation.Footnote 54 Similarly, when Paul Newman learned that he had to play the banjo in the film, he hired banjoist Dave Sear, a regular at the hootenannies in Washington Square Park, to teach him. Sear's selection was serendipitous: his cousin worked for Newman's agent.Footnote 55 But Sear's involvement in the project is significant because he was a respected player in the folk revival and an active performer and participant in the folk music field. Newman even attempted to have Sear hired by Warner Bros. as a folk music consultant for the film, but Kahn already had that job.Footnote 56 Regardless, in the end Sear's advice and lessons helped establish the believability of Newman's character.

In addition to the insertions of “Plastic Jesus” and “Just A Closer Walk With Thee,” Rosenberg made four more musical additions before shooting was complete in December 1966. All four were for Tramp, and none had been planned in the shooting script. More than likely, Rosenberg incorporated the songs (in each case just a phrase or two) to establish Tramp's character as a singer and guitarist and also to give music a regular presence on Sundays in the prison camp. The additional songs were “Camptown Races” (Stephen Foster), “Midnight Special” (Huddie Ledbetter), “Cotton Fields” (Ledbetter), and “Ain't No Grave” (Claude Ely). “Camptown Races” and “Ain't No Grave” have the longest durations in the film. The former is sung by Tramp while Luke trains in the prison yard for his egg-eating challenge. The latter appears during the sequence when Luke is tasked with digging and re-digging a ditch, and the prisoners watch him work from the barracks. As a sign of solidarity with Luke, Tramp starts singing “Ain't No Grave,” and the other inmates clap along. The ditch that Luke digs resembles a grave, but the song is abruptly cut short when Luke collapses.

For all of his concern about finding the right music for the film's context, Rosenberg surprisingly never found an appropriate tune for the chain gang to sing as they worked. The reason for this omission are not documented. The copyright requests show that he was still contemplating adding a song for the chain gang as late as February 1967 when the film was being edited. The requests suggest Rosenberg was considering pop music rather than traditional music (Table 2).

Table 2. Songs considered for Cool Hand Luke after shooting was complete.

By spring 1967, Rosenberg's involvement in the musical soundtrack had waned. An edited version of the film was delivered to Schifrin in March 1967, and the composer was given roughly six weeks to complete the score. He was not starting from scratch, however. In addition to having composed the opening theme on the set back in October, he had been kept abreast of Rosenberg's musical insertions. He had also been sketching ideas in preparation for the final edit. Schifrin's central challenge was making good on his proposal to create a score that blended American traditional music (folk, country, blues) with American orchestral music. He needed to find a link between those genres and his own compositional voice.

Phase Three: Schifrin, the Banjo, and the Blend

As Schifrin prepared, he pondered what to do with the banjo, an instrument with which he had little experience. Reaching out to the film's musical consultant, Ed Kahn, he asked for recordings of the best banjo players working in the United States at that time.Footnote 57 Kahn sent Schifrin several records, and one player immediately rose to the top: Earl Scruggs. Schifrin decided he wanted Scruggs as the principal banjo player for the score. The studio supported the idea, but Scruggs, who was arguably at the peak of his career in 1966, was unavailable. Schifrin returned to the recordings and zeroed in on a 1963 Elektra album entitled Folk Banjo Styles, featuring Eric Weissberg, Marshall Brickman, Tom Paley, and Art Rosenbaum. From that group, Kahn recommended the accomplished Rosenbaum (b. 1938), who was deeply involved in the folk revival and an active collector of banjo field recordings. Based in New York, he was a regular on the Washington Square Park scene.Footnote 58 Schifrin asked for Rosenbaum to send him some recent recordings, and he essentially auditioned Rosenbaum by mail.Footnote 59 Schifrin liked what he heard and told the studio to send a contract. Rosenbaum accepted the Cool Hand Luke offer at Kahn's urging, even though he was not entirely sure what to expect. Rosenbaum and Schifrin would not meet until a week before the recording sessions in May 1967.Footnote 60

To those familiar with banjoists of this era, this selection process is interesting because Scruggs and Rosenbaum represented two distinctly different styles. Scruggs was a bluegrass trailblazer, known for his speed and innovative picking patterns. Rosenbaum, on the other hand, played in the old-timey style, using a clawhammer approach. To Schifrin, this distinction was unimportant. He was interested in the banjo's compositional potential, especially the timbres it could generate and the complicated rhythmic patterns it could realize.Footnote 61 But the banjo also had some cultural baggage in the mid 1960s.Footnote 62 Two stereotypes predominated. The first was as the instrument of country comedy. The Beverly Hillbillies, a top-rated situation comedy from 1962 to 1971, was largely responsible for this image, along with two similarly themed shows, Petticoat Junction (1963–1970) and Green Acres (1965–1971). All three were popular in 1966–67, and all featured the banjo. The second stereotype was the banjo as the instrument of left-leaning folk singers. Pete Seeger had been the most visible example since the 1950s, and perhaps this was a connection Rosenberg and Carroll had hoped to exploit—after all, Seeger had been on their short list of folk musicians for the film. Schifrin made no mention of these stereotypes in my interview with him. His compositional focus at the time was on the scoring challenges, not the cultural context of the banjo. Yet in fact, the path he ultimately chose utilized the banjo in a novel way and departed significantly from these stereotypes.

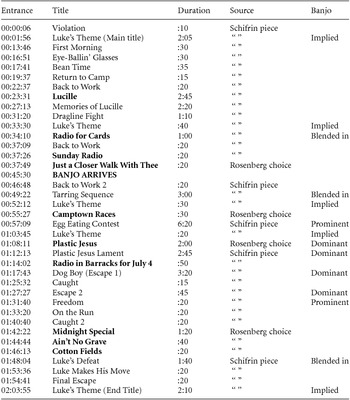

In the end, Schifrin made good on his proposal to use a blended approach, and his final score for Cool Hand Luke was neatly interwoven with Rosenberg's musical selections. In total, Schifrin composed thirty-one discrete cues of varying lengths, several of which had recurring elements. The complete cue list is provided in Table 3.Footnote 63

Table 3. Music in Cool Hand Luke, in order of appearance. Bolded titles are diegetic.

The most prominent cue is Luke's Theme, which Schifrin based on the melody he wrote during his October 1966 visit to the Stockton set. Schifrin scored the cue for two nylon-stringed guitars, one playing the melody and the other a beautifully syncopated countermelody (Example 2). The cue begins with the countermelody alone. The theme is first heard in the main title and is then reprised four times in the film. In each case its return marks an unconventional victory, always due to Luke's relentless perseverance against the odds, e.g., outlasting Dragline in a brutal fight, joyously tarring a road at breakneck speed, devouring fifty hardboiled eggs in an hour. The final occurrence of Luke's Theme is after Luke's murder, as the inmates fondly recall his antics and immortalize his memory. In each use of this cue, Luke's Theme enters at the end of the scene, after Luke's actions have spoken. This placement reinforced an idea Rosenberg articulated many years later about Luke's character: “If you want to judge Luke, you have to judge him by what he does, not by what he says.”Footnote 64

Example 2. Luke's theme countermelody. Transcription by author.

Luke's Theme marked a particular kind of recurring circumstance in the film (i.e., his unconventional victories), and a similar line of thinking informed two other groupings of cues: the transportation cues (First Morning, Eye-Ballin’ Glasses, Return to Camp, Back to Work) and the escape cues (Dog Boy, Escape 2, On the Run, Final Escape). In these two sets of cues, Schifrin created linkages not through thematic unity, but rather through common orchestration and rhythmic gestures. Yet the connections within each group are unmistakable. In the transportation cues, for example, which accompany the scenes showing the prison trucks carting the chain gang to their brutal work, Schifrin relied heavily on strident lower brass that sputtered in jagged rhythms, layered with a string ostinato. Similarly, the three escape cues share many distinct colors, particularly the snare drum, an angular, driving piano bass line, and thick orchestral chords strummed like a guitar (and based on the instrument's open strings, E–A–D–G–B–E). Another instrument that appears in multiple escape cues is the harmonica, usually providing a brief reference to the blues. Schifrin's handling of these various timbres throughout the score showed his talent for orchestration, a trait that he described later as central to his compositional process: “I'm not the kind of painter who first makes a sketch in black and white and then puts in the colors. I do the painting directly.”Footnote 65

In fact, it was Schifrin's sensitivity to instrumental color that ultimately enabled him to determine how best to integrate the banjo into the score. In a 1969 interview in Downbeat, Schifrin commented that the banjo was in many ways the underlying inspiration for the Cool Hand Luke score. It was an instrument that he wanted to understand better, particularly how it was used in improvised contexts like bluegrass to render complex rhythmic lines: “[N]ow I had the chance to discover the intricate lines—I went inside the banjo. A good banjo player gets those intricate lines . . . the way an African drummer plays polyrhythmically. They are asymmetrical, irregular, and very angular. And this triggered my score.”Footnote 66 Schifrin approached this compositional challenge, along with any others in the film, without a hard and fast plan. When interviewed in 2002 about the score, he stated that his compositional process largely unfolded by “instinct.” Clearly his training and experience informed that instinct, but he could not necessarily articulate why he chose one note over another. He mentioned that in general when he concentrated too much on process, the resulting music sounded too “academic.”Footnote 67

Yet even though Schifrin had no preconceived plan for how to deal with the banjo, a close analysis of the Cool Hand Luke score shows an underlying coherence in its presentation. The complete cue list in Table 3 includes a column that charts all of the banjo-related cues in their order in the film and places them in the framework of Rosenberg's final edit. The column shows that Schifrin created a subtle arc of exposure for the banjo. Its presence begins with only a hint of the instrument, in a gentle rhythm embedded in the countermelody of Luke's Theme. Schifrin noted that the cue's countermelody was inspired by a slowed-down version of a common banjo rhythm, what banjo players might call the “bum-ditty” (essentially a quarter note and two eighth notes, Examples 3a and 3b).Footnote 68 Because the cue's tempo is so slow, this banjo reference is not obvious—the ear is drawn instead to the main melody that works against this rhythm. In addition, soon after the rhythm begins, Schifrin develops it through syncopation. But the banjo seed is planted in Luke's Theme in the main title and again when it returns a few scenes later following Luke's fight with Dragline.

Example 3a. Bum-ditty-bum.

Example 3b. Luke's Theme countermelody.

After these two initial statements of Luke's Theme in the non-diegetic score, Schifrin gradually builds on the banjo reference in the diegetic space. The first gesture in this direction immediately follows the Dragline fight, as the chain gang plays poker, and Luke bluffs his way to a winning hand (thus earning his nickname “Cool Hand”). In the background, a radio softly plays old-timey country music (composed by Schifrin): the cue features a banjo paired with a fiddle. The music is barely audible, and in fact quickly disappears when the drama of the game intensifies. This brief diegetic reference, however, is a clever sonic segue to the literal banjo's appearance as a prop in the next scene: Arletta's visit. At the visit's conclusion, Luke's brother pulls a banjo out of the pick-up truck and hands it to Luke, saying, “Now there ain't nothing to come back for.” Luke's attachment to the instrument is not explained, but clearly it has significance. This banjo appearance, coupled with the card scene preceding it, effectively prepares the way for the instrument proper to enter the non-diegetic score.

The banjo's non-diegetic entrance happens in the scene immediately following Arletta's visit, when the inmates face the punishing task of tarring a road in the hot sun. The prisoners begin their work slowly, hoping to save their energy for the long afternoon ahead. Luke, however, starts shoveling at double the pace of the others. His energy catches on and soon the entire chain gang is working as hard and as fast as it can. Schifrin's non-diegetic music for this scene enters after the tarring process begins and emerges out of the task's diegetic sounds: clanking shovels, the hiss of the tarring truck, and the sounds of sand hitting the road. Multiple rhythms, each one out of phase with the others, are heard. Schifrin quietly introduces non-diegetic music into the midst of the sonic fabric, initially via a chromatically circular figure in the strings. Within that musical blur, he adds the banjo playing a modified version of the string figure. The musical blur underscores the chain gang's flurry of activity, which has confounded the guards. As the chain gang joyously tars the road, Schifrin's cue develops from a chromatic blur into a lively mixed-meter orchestral dance, akin to Aaron Copland's Hoe-Down” in Rodeo, and the banjo becomes one of many orchestral colors incorporated into the joyous, bouncing rhythms. The dance captures the blend of American traditional and American symphonic music that Schifrin had promised Rosenberg.

The film's next sequence—the egg-eating contest—gives the banjo even more prominence. The scene begins in the barracks, where Luke is on his bunk fumbling with his instrument. In a clever twist, the notes Luke struggles to play are actually the opening phrase of his own theme! Precisely whose idea this was is not recorded, but it marks an intriguing (although fleeting) real-time connection to the non-diegetic score via the banjo. Regardless, Luke is simply killing time as his fellow inmates argue about who can eat the most. Seemingly half-listening, he suddenly has a thought: “I can eat fifty eggs.” The statement stuns the others, and moments later Luke admits that he just made it up (“seemed like a nice round number”). In the scene immediately following, he meets this challenge spectacularly and again becomes the prison hero. The egg-eating scene lasts over six minutes and has musical accompaniment throughout. It begins with fiddle references over a playful string bass solo and commentary from the winds and brass. But the cue's most distinct and pronounced timbre is the banjo, which enters at the precise moment Luke begins eating the eggs, playing in an energetic three-finger style. This overt use of the banjo during the egg-eating scene also effectively prepares the viewer for Luke's banjo performance of “Plastic Jesus.”

The banjo's prominence in the egg-eating scene and in the subsequent “Plastic Jesus” performance has an unmistakable musical consequence in Schifrin's score. For the remainder of the film, the banjo becomes a vivid, non-diegetic symbol of Luke's free spirit. For example, the banjo dominates the underscoring for Luke's stint in solitary confinement, which immediately follows the “Plastic Jesus” scene. The solitary confinement sequence is a montage, and for it Schifrin crafted an instrumental ballad based on “Plastic Jesus,” giving the slow melody to the banjo—a novel use of such a percussive instrument. The banjoist for this specific cue was not Art Rosenbaum, but rather either Howard Roberts or Tommy Tedesco, the two guitarists whom Schifrin used for the recording sessions.Footnote 69 This decision was not a slap in the face to Rosenbaum, but rather a necessary adjustment. When Rosenbaum arrived in Los Angeles a week prior to the recording sessions, Schifrin learned that he was not fully fluent in reading music. The discovery surprised Schifrin at first, but he was quickly put at ease by Rosenbaum's musical abilities. The two met frequently at Schifrin's home in Beverly Hills in the days prior to the sessions to determine how best to use Rosenbaum's skills. Schifrin reassured Rosenbaum that the reading issue was not a problem. Schifrin had worked with improvising musicians in jazz for years, so he knew how to communicate his ideas in ways other than notation. In the end, his primary interest in Rosenbaum's skills was to tap into those fast, polyrhythmic, asymmetrical rhythmic lines that the banjo could produce so effectively. For those passages, Schifrin and Rosenbaum worked out the musical parameters in the days before the recording sessions began. When they got to the sessions, Schifrin trusted Rosenbaum's abilities and got out of the way. He told him, “Don't worry. When I tell you to start playing, you just go. And when I tell you stop, you stop.”Footnote 70

Schifrin gives the banjo more prominence in the second half of the film, notably in the escape sequences. For example, during Luke's first escape, Schifrin layers an extended banjo solo for Rosenbaum on top of the orchestral accompaniment at the precise moment Luke's running feet hit the train tracks—a musical gesture that freedom had been obtained. The freedom is fleeting, for Luke is soon captured, but within a few days he escapes a second time. Again, Schifrin uses the banjo to articulate Luke's brief stint on the outside. As this cue develops, the banjo acquires even greater meaning because in the latter part of the scene, the banjo track is manipulated through overdubbing. This distorted banjo foreshadows Luke's capture just moments later.

Luke's two escape attempts make him the target of abuse by the prison bosses. They engage in a conscious and vicious effort to “get his mind right” by beating him, placing him in solitary confinement, and subjecting him to backbreaking labor intended to kill him from exhaustion. The tactics eventually work. Luke weeps at the feet of the bosses and pleads for mercy. The idea that the guards could break Luke crushes his fellow inmates, who have come to see him as invincible. The chain gang responds by shunning their hero; and during this portion of the film the banjo disappears entirely—it has no role during Luke's physical and psychological torture, it has no presence as a prop, it is not heard in either the diegetic or the non-diegetic score.

The banjo's link to Luke's free spirit, however, does return one last time. As night falls during his third (and final) escape, Schifrin incorporates a soft melody that pairs the banjo in unison with the guitar. The blending of the two instruments is fleeting but significant because it weds the two musical symbols of Luke used throughout the score. Following this cue, the banjo disappears completely from the score, presaging Luke's death. When Luke's Theme returns for a final time in the film's last minutes, Schifrin's banjo–inspired rhythm carries even more meaning. The film's message—that Luke's legacy will persevere—has a sonic corollary in the gentle “bum-ditty” rhythm first heard in the opening moments of the film. It has sustained a twisted journey, but it remains a beautiful and poignant constant.

Conclusion

Rosenberg and Schifrin would work together on several more projects in the course of their long careers, including WUSA (Paramount, 1970), Voyage of the Damned (AGF, 1976), The Amityville Horror (AIP, 1979), and another prison film, Brubaker (20th Century Fox, 1980).Footnote 71 But Cool Hand Luke stands as the highpoint of their collaboration. Innovative and highly effective, the soundtrack pulled from a deep pool of musical resources, some old and some new. In that sense, its musical variety (i.e., its references to folk, country, bluegrass, and American symphonic music) was indicative of the musical diversification that was transpiring in Hollywood in the mid- and late 1960s.Footnote 72

The creative process surrounding the Cool Hand Luke soundtrack was complex. It is interesting to consider how different the music might have been if Warner Bros. had forced Rosenberg to keep the Lightfoot song, or Paul Newman had refused to play the banjo, or the various copyright challenges had been easily solved. Those hypotheticals are reminders of the role outside forces can have in forging a film's musical path. They also reflect the instability that is inherent in the filmmaking process. It is an art form that requires teams of individuals to come together and exchange ideas. Something unexpected is bound to happen, and Cool Hand Luke showed that to be true in each phase of its production.

Rosenberg held significant power in this creative process, but Schifrin's input cannot be overemphasized. It was his proposal—the blending of orchestral music with folk, country, and bluegrass elements—that provided Rosenberg with the conceptual framework for the entire soundtrack. In addition, it was Schifrin's skills as a composer that also helped resolve the difficult issues surrounding authenticity. Schifrin took the time to study the genres and instruments that formed the core of the musical traditions Rosenberg wanted to include and then integrated what he had learned into the larger score. What he created had its own logic and integrity, but at the same time paid homage to the musical traditions that were so closely tied to the context and plot of the Cool Hand Luke story. It supported Luke's actions in meaningful and thought-provoking ways, and by doing so communicated authenticity of its own kind.

The Cool Hand Luke soundtrack is a compelling piece of musical rhetoric. Its strategies are subtle, and in that respect it makes sense that the music has evaded serious commentary for fifty years. But it deserves attention because its quality and diversity reflect what can happen when a director and a composer have trust for one another and are open to the musical opportunities that come their way. Its creative process also lays bare the pressures and tensions that existed within the American film industry in the mid- and late 1960s. Those conditions would soon shift, as the prevailing winds in Hollywood pushed more strongly toward soundtrack strategies that valued previously recorded music over original music.Footnote 73 Cool Hand Luke stands as a testament in those changing times to the artistry that a strong director-composer relationship can produce. It also shows how intention and planning are not always the most important components of the creative process. Like Luke's improvised victories throughout the film, Rosenberg and Schifrin demonstrated in this project how fodder for artistic success comes from bantering ideas around, listening to others, and creating a context in which all parties are unafraid to take a risk.

In the end, the music of Cool Hand Luke captures the spirit of the existentialist hero that Rosenberg became so enamored with in the summer of 1965. Luke's music and the music that envelops his world speaks with honesty, bolsters Luke's impact, and most importantly, subtly encourages us to look and listen more deeply.