In a 1946 article in the New York Times, the violinist Jascha Heifetz (1901–87) characterized his musical taste as broad minded, professing his dedication to the folk and popular song of his adopted home in the United States:

I have never hesitated to play Stephen Foster's “Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair”. . . It's a fine song, American to the core. Why should I go hunting for its Viennese or Parisian equivalent and try to palm that off as art because it has a foreign name? Foster's tune is art in its class. So are the songs of Kern, Gershwin and Berlin. I think Irving Berlin's “White Christmas” is a grand tune, and it pleases me to play it in concert or on the radio.Footnote 1

The diversity of interests and influences that Heifetz described was reflected in the works that he performed, published as arranger and editor, and taught to the pupils in his studio. Throughout his career, Heifetz promoted a modern brand of musical eclecticism. Like many of the violinists of his and the preceding generation, he recorded and performed adaptations for violin of songs and dances associated with so-called “folk” and “popular” traditions, while always remaining dedicated to the standard works of the violin repertoire and the compositions of his contemporaries. He edited arrangements of folk songs and dances by composers including Isaac Albéniz, Alexander Krein, and Joseph Achron, as well as original settings of Stephen Foster's “Old Folks at Home” and “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair,” numbers from George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, and the African American spiritual “Deep River.” He also made recordings with Bing Crosby of Irving Berlin's “White Christmas” and Edward Teschemacher and Hermann Löhr's “Where My Caravan Has Rested.”

Heifetz enjoyed performing such short musical works, which he called “itsy-bitsies,” and used them in his teaching.Footnote 2 He characterized these miniatures as both challenging and rewarding because they afforded the violinist only three or four minutes in which to evoke the wide range of expressive modes and technical virtuosity that are more dispersed in genres such as the sonata and concerto.Footnote 3 Between the 1910s and 1930s, Heifetz typically divided his concert programs into four sections, almost always incorporating a number of “itsy-bitsies.” The first two sections of his programs included movements from concertos, sonatas, and other canonic works for violin in large-scale genres, and the third section typically consisted of an eclectic selection of three or four miniatures, including adaptations of folk songs and dances and brief arrangements of nineteenth-century pieces originally for keyboard. The fourth section incorporated one or two longer virtuosic one-movement works, such as Pablo de Sarasate's “Zigeunerweisen” (“Gypsy Airs”), “Habanera,” or “Malaguena,” Leopold Auer's arrangement of Nicolò Paganini's Caprice No. 24, or a showstopper by Jenő Hubay or Henryk Wieniawsky.Footnote 4

Heifetz was not alone among contemporary violinists in developing a reputation for borrowing from European and American folk and popular music. Newspaper critics often commented on violinists’ musical eclecticism. One article noted that the Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti, “A representative of all that is austere and classical in music, . . . is far from being scornful of swing.”Footnote 5 In 1942, Szigeti's manager Herbert Barrett aimed to garner interest in a new album, Joseph Szigeti in Gypsy Melodies, by announcing, “Though he ranks as one of the world's foremost violinists, Szigeti is no highbrow. His name has always been synonymous with great art, but also with all music which is a vital expression of the people. He likes nothing better than a night club where good swing is featured.” Barrett wrote that Szigeti played on the record “with true Gypsy abandon.”Footnote 6 Mischa Elman, Heifetz's fellow student in Leopold Auer's studio at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, also edited and performed settings of folk songs and dances, and professed his interest in popular music. “I hope that jazz will never die,” he said to a reporter in 1923. “The greatest think [sic] in life is to feel that one is really alive, that one is full of spirit and vitality. What accomplishes that purpose more than jazz? Why, if jazz were to be taken out of American life, many people would become mummified as this King Tutankhamen, who has just been excavated after being buried 3,000 years.”Footnote 7 In the manner of Heifetz and Szigeti, Elman addressed jazz as an authentic form of musical expression, and even a life force for U.S. listeners.

Although Szigeti, Elman, and other violinists expressed admiration for popular music and arranged miniatures based on folk genres, Heifetz's eclecticism stands out as particularly remarkable because of his extensive list of arrangements, editions, and recordings of this repertoire, his collaborations with musicians active in popular culture such as Crosby, and his dabbling in Hollywood cinema. His wide-ranging repertoire exhibited a stylistic fluidity and intertextuality that is best understood through the concept of hybridity.Footnote 8 His arrangements borrowed from a variety of cross-cultural musical idioms, employing a diversity of musical techniques, melodies, gestures, tropes, and styles. In this way they created a kind of musical “heteroglossia” analogous to the multiplicity of speech types characterized by Russian philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin. Bakhtin's notion of hybridity and intertextuality, which he explored in literary genres, also proves useful as applied to an examination of Heifetz's eclectic musical mixture and self-conscious layering of idioms from a variety of sources. Bakhtin describes hybridity as “a mixture of two social languages within the limits of a single utterance, an encounter, within the area of an utterance, between two different linguistic consciousnesses, separated from one another by an epoch, by social differentiation or by some other factor.”Footnote 9 He continues, “the novelistic hybrid is an artistically organized system for bringing different languages in contact with one another, a system having as its goal the illumination of one language by means of another, the carving-out of a living image of another language.”Footnote 10 Heifetz's “itsy-bitsies,” and the concert programs on which he juxtaposed works representing the musical traditions of a variety of geographic locations and cultures, display a similar sort of hybrid intermixture of musical influences. In his performances, Heifetz used the “voice” of the violin, the medium of notation, and the contexts of recital programs and sound recordings to merge and juxtapose musical styles in order to create a new idiom that was informed by both classical and popular music cultures.

Many of the works in this genre of virtuosic musical miniatures traded on tropes associated with nineteenth- and twentieth-century musical exoticism—augmented seconds, dance meters, and other stereotypical elements of folk music—to entice turn-of-the-century audiences with glimpses of the “foreign” and “primitive.” It is valuable, however, to look beyond the exoticizing impact of these techniques, and examine the important roles of ethnographic research in providing the musical source material on which such works were often based.Footnote 11 The concept of hybridity allows for a reading of the intertextuality evident in the composition, performance, and reception of Heifetz's cross-cultural miniatures. It also informs an understanding of this genre as a product of both the quest to rediscover folk music cultures and the desire to assimilate contemporary genres and styles of classical and popular music with traditional melodies.

This article examines the hybridity of Heifetz's recital repertoire and the miniatures he arranged. It describes the diverse reception his musical eclecticism inspired in the critical press, and the ways his miniatures were adapted by other musicians in the Jewish immigrant community in New York. In particular, it examines the complex influences of his displacement from Eastern Europe and assimilation to the culture of the United States on both the hybridity of his repertoire and the critical reception he received in his new home. It takes as its case study Heifetz's composition of the virtuosic showpiece “Hora Staccato,” based on a Romany violin performance he heard in Bucharest, and his later adaptation of the music into an American swing hit he titled “Hora Swing-cato.” Finally, the essay turns to the field of popular song to consider how two of the works Heifetz performed most frequently, “Hebrew Melody” and “Zigeunerweisen,” were adapted as Tin Pan Alley–style songs whose Yiddish lyrics narrate the early twentieth-century immigrant experience. The history of the reception of Heifetz and his music, as evidenced in newspaper criticism as well as in song lyrics, film, sheet music paratexts, and other varied sources, demonstrates the fragility of the barriers between conceptions of classical, folk, and popular music in the United States of the early twentieth century. The performance and arrangement history of many of Heifetz's miniatures reveals the multivalent ways in which his music, and Heifetz himself, were reinterpreted, adapted, and assimilated into American culture.

Heifetz's Eclecticism Expressed in Journalism and Popular Song

In the interpretations of some critics and listeners, Heifetz's eclectic repertoire and his approach to stylistically hybrid works were products of the violinist's background and signs of his personal identity, as a displaced Eastern European Jewish immigrant assimilating to his cultural surroundings in the United States. A Gramophone review of Heifetz's 1917 recording of the miniature “Hebrew Melody,” by the Russian Jewish composer Joseph Achron, asserted that Heifetz's interpretation of this work was shaped by his Jewish heritage.Footnote 12 Referring to Heifetz's famously still posture and inscrutable, stoic demeanor as a performer, he writes that Heifetz's playing is generally “cold, calm, [and] dispassionate,” and asks, “do we not feel slightly chilled, anxious perhaps for less mastery and more humanity[?]”Footnote 13 He continues,

Heifetz does once give us a glimpse of his real self in the Hebrew Melody by Achron . . . In the writer's opinion this is easily the most beautiful of his records, both from the interpretive and recording points of view. The tune, supported by an orchestral accompaniment is surely an old Hebrew one; appealing, therefore, to immemorial racial instincts and traditions in the Jew. It does seem to have penetrated beneath the outer shell of this curious personality.Footnote 14

According to this critic, the barrier Heifetz had constructed against emotional expression in his performances is broken down by Achron's work, and Heifetz, confronted directly with an artifact of his own tradition, cannot help but be moved and convey his sentiment in his playing.

The review attributes the qualities of passion and authenticity in performance to the unique resonance between the repertoire and the violinist's ethnic identity. The critic's interpretation of this recording of course relies on a number of unverified assumptions about both the work and its performer. He asserts that Achron's composition is “surely an old Hebrew one,” though it is in fact a contemporary setting of an unidentified melody that Achron claimed to recall from a childhood visit to a Warsaw synagogue. And on the basis of Heifetz's geographical origins and his family's Jewish ethnicity, the critic assumes that Heifetz must respond in a different and more personal way to a work based on Jewish music traditions than he does to any other piece in his repertoire.Footnote 15

The claim that Heifetz's playing style was “cold” and “stoic” was not uncommon in critical reviews during his life; Nicholas Slonimsky called Heifetz the “celebrated child prodigy and violin virtuoso of the new school of ‘cold tonal beauty.’”Footnote 16 The realization of a performance on violin that listeners consider “expressive,” “emotive,” or “fiery” typically involves the production of particular combinations of sonic tropes—rhythmic, timbral, and intonational—in the interpretation of a work, and Heifetz's recordings reveal such gestures in abundance. Spectators viewing performances live and onscreen are also apt to interpret expressiveness from visual cues, such as facial contortions and physical movements of the body, and it is in this respect that Heifetz's performances were notably more reserved. Heifetz considered such movements as extraneous, even detrimental to successful performance, viewing them as unnecessary theatrics. He explained that in performance, “[t]he music will speak for itself.”Footnote 17 It seems that the critic for Gramophone based his assessment of Heifetz's playing on the violinist's physical appearance in performance and his popular reputation, rather than on the sound he produced.Footnote 18 But the critic's description of the recording of “Hebrew Melody” indicates a belief that Heifetz's Jewish identity provoked an emotional reaction that broke through his austere veneer when he performed Achron's setting of a Jewish prayer.

The notions that Heifetz's stoic exterior hid a deeper attachment to Jewish culture and that his career in classical music gave cover to a natural propensity toward vernacular forms of music were expressed in the 1921 song “Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha,” by George and Ira Gershwin.Footnote 19 The lyrics about the Russian Jewish violinists Mischa Elman, Jascha Heifetz, Toscha Seidel, and Sascha Jacobsen weave a satirical narrative about their personal identities, which are described in the text as being defined by their Jewish ethnicity and geographic origins in Eastern Europe, as well as by the processes of assimilation to the culture of their new home in America. The Gershwins penned this number to be performed at parties for the amusement of their friends, possibly including the four eponymous violinists, all of whom had studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory under Auer and were by this time living and working in the United States.Footnote 20 “Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha” was published in 1932, and recorded as a comic novelty by the Funnyboners (1933) and as a swing hit by the Modernaires with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra (1938).Footnote 21

Written from the point of view of the four violinists, the song depicts the Eastern European background of these musicians as an exotic attribute of their identities: “Temp'ramental Oriental gentlemen are we,” they sing in the refrain. In the first verse they explain, “We really think you ought to know/ That we were born right in the middle/ Of Darkest Russia/ When we were three years old or so/ We all began to play the fiddle/ In Darkest Russia.”Footnote 22 In a later verse, Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, and Sascha sing about how they have been able to capitalize on the exotic sound of their names to appeal to listeners when building their careers in the United States, rather than adopting new, more American-sounding pseudonyms: “Shakespeare says ‘What's in a name?’/ With him we disagree/ Names like Sammy, Max, or Moe/ Never bring the heavy dough/ Like Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha/ Fiddle-lee diddle-lee dee.”Footnote 23 But according to the Gershwins, underneath the façade these violinists present to their audiences lurks a love for American popular music: the quartet sings,

This stanza explains that despite the sense of foreignness and taste for “high” art signified by their concert demeanor, Eastern European accents, and classical repertoire, these violinists are Americans like “everyone” else, with a hankering for jazz. The two thematic strains of the song—the association of these violinists with both far-off Russian culture and America's home-grown popular music—are joined when the quartet sings that their Jewish heritage eclipses the kinds of music they play as the key element of their public identities: “We're not highbrows, we're not lowbrows, anyone can see/ You don't have to use a chart/ To see we're He-brows from the start.”Footnote 24 Thus these famous violinists, invoked as signifiers of both the differences and similarities between classical and popular musical styles and immigrant and American identities during this period, are depicted as, first and foremost, members of the transnational Jewish diaspora. Their appeal comes in part from the exoticism of their names and origins in “Darkest Russia,” but they also represent the beginnings of the assimilation of European and American cultures by bringing together the repertoires of the classical virtuoso recital and the jazz band.

In the recording of “Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha” by the Funnyboners, the song's jaunty and humorously simple melody is preceded by a comical sound montage that signifies classical music pedagogy and performance. The disc opens with a quotation of Antonín Dvořák's “Humoresque,” a standard work in the solo violin canon that both Heifetz and Elman recorded in their youth. It continues with the sound of the open strings of an out-of-tune violin, played in pairs from the highest strings to the lowest and back up again. After the piano plays a simplified rendition of the melody to Felix Mendelssohn's Song without Words Op. 62, no. 6 (“Frühlingslied”), and following a brief vamp in the piano, the Funnyboners begin to sing. At the conclusion of the disc, they sing a final “fiddle-lee diddle-lee dee” as a violinist plays a scratchy rendition of the melody of the “Morning” prelude to Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt. The sounds of both the unsuccessful efforts at tuning the violin and the references to standard recital works in the context of the melodies and accompaniment in the style of Tin Pan Alley gently mock the popular regard for these musicians and general impressions of “high-brow” music.

The opening sequence plays on a preexisting vaudeville routine in which a violinist juxtaposes excerpts of works in the repertoire with popular melodies, played out of tune with faux virtuosity. Jack Benny was a master of this comic act, and later performed it on radio and television and in films including the 1944 Hollywood Canteen, in which he plays a duet with Szigeti. Another number in this style can be found in King of Jazz, a 1930 musical film in which Paul Whiteman narrates a history of jazz. In a comedic sequence, Wilbur Hall, a musician in Whiteman's orchestra, busks with his violin on a dark street, dressed as a hobo and wearing slapshoes like the earlier vaudevillian Little Tich. His playing is scratchy, jerky, and out of tune as he performs phrases from well-known melodies including Kreisler's “Liebesfreud” and the song “Pop Goes the Weasel.” The music is repeatedly interspersed with abrupt attempts to check the intonation of his instrument, as he plays his open strings in the manner of the beginning of “Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha.” In the field of American popular song, the reference to “Frühlingslied” in Hall's performance has a precedent in Irving Berlin's 1909 “That Mesmerizing Mendelssohn Tune,” in which the refrain quotes a fragment of Mendelssohn's principal phrase, to the lyrics “Love me to the ever lovin’ Spring Song Melody.” In this song's sheet music, published by Ted Snyder Co. in New York, the piano repeatedly plays a scalar gesture that imitates the patterns found in pedagogical violin studies.

“Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha,” then, interprets the careers of these violinists by emphasizing their national and ethnic identities as a justification for their musical tastes, whereas the Funnyboners’ recording satirizes “high-brow” culture by incorporating stock tropes from vaudevillian musical humor. The lyrics assert that these musicians in fact identify less with the canonic works of classical violin repertoire than with U.S. popular genres that provoke in them an enthusiastic, spontaneous, and authentic mode of expression. The tendency to associate Heifetz's musical eclecticism with his presumed identity—itself personal, private, and perpetually in flux as he moved throughout the world during his career—links his taste in repertoire to his origins and his displacement and characterizes the musician's task in general as a search for authenticity, that is, for a musical expression of the true inner self.

Jascha Heifetz's Amateur Ethnography and “Hora Staccato”

Heifetz himself helped forge his reputation as an austere and forbidding personality, while professing his love for American popular music. His performance style, statements in interviews, and choice of repertoire fundamentally shaped his public image as an exotic figure and a European immigrant to the United States reinvented as a new American. His performance of folk music arrangements and his support of popular song aided his acceptance as a displaced as well as assimilated artist. The history of Heifetz's famous “itsy-bitsy” showstopper “Hora Staccato” demonstrates the ways in which critics and performers conceived of the hybridity of influences in his music and highlights how Heifetz responded to this reception in his performances and adaptations of the work.

In 1929 Heifetz visited a Bucharest café, where he heard a performance by the Romany violinist Grigoraş Dinicu, a student of the violin pedagogue Carl Flesch and graduate of the Bucharest Conservatory. Dinicu played “Hora Staccato,” which he had arranged in 1906 based on the melody of a Romanian hora, a genre of circle dance.Footnote 25 Heifetz saw the potential to adapt, publish, and perform a new version of this showpiece, and signed a contract with Dinicu to buy publication rights to the music for 16,000 Romanian lei, on the agreement that their names would appear together as coauthors.Footnote 26 Heifetz's arrangement was distributed by Carl Fischer.

Early editions of the work emphasized its origins in an act of amateur ethnographic collecting, presenting it as a product of transnational encounter and discovery in order to attract the interest of American listeners. Although Heifetz never received formal training in ethnography or wrote about folk music, he does appear to have had early exposure to the methods and goals of the field. During his studies with Auer at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Heifetz had become a friend and collaborator of several members of the Society for Jewish Folk Music, an organization founded in 1908 by composers and ethnographers who promoted the study of Jewish traditional musics and the development of a new idiom of Jewish art music.Footnote 27 Heifetz was likely aware of the accomplishments of the Society. He owned a copy of the Lieder-Sammelbuch für die jüdische Schule und Familie (Song Anthology for the Jewish School and Family), a collection of Jewish traditional melodies compiled by ethnographer Susman Kiselgof, published in 1912 by the Society's printing house.Footnote 28 Kiselgof signed the front page of Heifetz's copy in January 1914, personalizing it with the words, “My modest work, to the master and commander of the violin, my dear pupil Jascha, for his thirteenth birthday.”Footnote 29 Although it is not certain whether Kiselgof is indicating that Heifetz studied with him directly, Kiselgof apparently served in some way as a mentor to Heifetz during the early 1910s. It seems, therefore, that the young Heifetz was exposed to the work of the ethnographers of music affiliated with the Society for Jewish Folk Music.

Heifetz wished for certain details of the origin of “Hora Staccato” to be apparent to the work's performers and listeners, in keeping with the increasing vogue for ethnography during the early twentieth century. Developments in this field were spurred by the invention and improvement of technologies of sound recording, photography, and film that could be used in the study and documentation of the world's cultures.Footnote 30 Folklore became the subject of increasing popular interest as modernity, the influx of populations to cities, and the growth of nationalist movements provoked ethnographers to study rural communities in order to expand their knowledge of ethnic traditions and salvage cultures viewed to be in danger of disappearance.Footnote 31 In an early handwritten manuscript copy dated 29 March 1930, Heifetz settled for the first time on the final title: his piece was to be called “Hora Staccato,” followed by the parenthetical attribution, “(Roumanian).”Footnote 32 This title—adhered to for years in reprints of the score, sheet music catalogues, concert programs, and sound recordings—identifies a folk genre, a performance technique, and the genre's regional and cultural origins. Published editions of “Hora Staccato” were attributed to both Dinicu and Heifetz.

Heifetz's arrangement of “Hora Staccato” is in the 2/4 time signature of many Romanian horas, with a generally consistent “oom-pah” pattern of alternating eighth notes between the left and right hands in the piano part accompanying the violin line. The main focus of the solo part, and the feature that gives the work the other half of its name, are the recurring passages of slurred staccato sixteenth notes, written to be performed at a fast pace with long down-bows and up-bows. This is difficult to play crisply and precisely, especially on the down-bow, but Heifetz could execute this virtuosic technique masterfully, and no doubt chose to arrange Dinicu's melody in part to provide himself the opportunity to show off his skill. The structure of the work is characteristically simple and highly repetitive, divided into the following sections: A (mm. 1–24); A’ (mm. 24–44); B (mm. 44–88); B’ (mm. 88–130); A” (mm. 130–50). There are frequent passages of pedal tones, and the majority of the piece is in E-flat major, with only one brief modulation to A-flat major, beginning when the tonic chord with added flat 7th scale degree, which first appears in m. 92, takes on the role of the dominant V7 of A-flat major, resolving in m. 101. The tonality begins to shift back to the original tonic in m. 111.

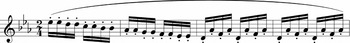

Harmonic irregularities and the evocation of foreign modality are produced by the use of the octatonic scale. Heifetz and Dinicu frequently juxtapose E-flat major tonic chords with an oscillating pattern that conforms to the octatonic scale on E-flat, but without the F-flat: E-flat–F-sharp–G–A-natural–B-flat–C–D-flat. This scale appears in the piano in mm. 1–2 and in the violin throughout sections B and B’ (Examples 1a and 1b). The scale incorporates an augmented second between the first and second scale degrees; this interval is a common trope in Romany music as well as a recurring signifier of the exotic in Western art music. Additional non-chord tones create surprising, off-kilter dissonances elsewhere, especially in the piano on every second beat in mm. 119–29 (Example 2). Other evocative gestures include grace notes, trills, heavily accented downbeats (e.g. mm. 13–15, 22–24, 33–35, and 42–45), chromatic scales (e.g. mm. 44 and 88), slides (mm. 65, 87–88, and 101), and triplets that jauntily contrast with the otherwise consistent duple rhythms (mm. 59, 67, 71, 83, 87, 113, and 129).

Example 1a. Jascha Heifetz and Grigoraş Dinicu, “Hora Staccato,” mm. 1–3.

Example 1b. Jascha Heifetz and Grigoraş Dinicu, “Hora Staccato,” mm. 45–48.

Example 2. Jascha Heifetz and Grigoraş Dinicu, “Hora Staccato,” mm. 119–29.

Heifetz's version of “Hora Staccato” was arranged in a variety of instrumentations and musical idioms. New editions appeared for cello, viola, B-flat clarinet or tenor saxophone, E-flat alto saxophone, accordion solo and duet, piano solo and duet, and other combinations of instruments. In 1938 Carl Fischer published arrangements for orchestras increasing in size from small to “full” and “symphonic,” by Adolf Schmid, an orchestrator who worked at the National Broadcasting Company. Schmid's editions featured an explanatory blurb that told the story of Heifetz's initial composition of the piece:

This brilliant work has the most romantic origin that may be imagined. Its discovery illustrates Mr. Heifetz's acute sensitivity to outstanding materials which, when transcribed will enrich violin literature. One evening, while in a café in Bucharest, Roumania, Mr. Heifetz was suddenly aware of a strangely exciting melody played by a young gipsy violinist. He was intrigued by the unusual character and rhythm of the piece, and upon inquiry, learned that it was the player's own composition. The performer's name was Dinicu, who, astonished at the great virtuoso's interest in his work, seized a napkin and quickly produced on the linen, a rough sketch of his composition. This was presented to Mr. Heifetz, and out of this source was developed the transcription known as “Hora Staccato,” a virtuoso number of bewildering effects and surprises, demanding technical left-hand ability of the highest order and unusual skill in staccato bowing.Footnote 33

This tale casts Heifetz's work as emerging from an unexpected ethnographic encounter during a trip abroad. Dinicu's formal training and identity are reduced to the descriptive phrase “young gipsy violinist,” apparently aimed to conjure for U.S. audiences the stereotype of an untrained Romany fiddler who plays energetic music in public settings. Dinicu wrote a rough transcription of the music on a napkin, which, this account implies, Heifetz transported on the journey west, to present it to new audiences as a souvenir of his travels.

“Hora Staccato” continued to meet with tremendous success. In 1939 Heifetz performed the work in the Samuel Goldwyn film “They Shall Have Music,” in which he starred as himself, helping to protect a music school that offers free lessons to disadvantaged children in New York City. Led by Frankie (Gene Reynolds), a young violinist brought in from living on the streets by the school's director, the students meet Heifetz in front of Carnegie Hall, where they are busking to raise money for the indebted school, and Heifetz agrees to send the students a film reel of his performances. Heifetz is seen in this reel playing the opening of “Hora Staccato” in a shot of the projector's lens, and his performance continues in a new shot of the screen in the front of the room where the student body and their teachers look on enthralled (Figure 1). In images of the school audience, Frankie's eyes are glued to the screen in admiration, his mouth agape, and even his rough, streetwise sidekick Limey, smacking his chewing gum, begins to smile. A couple of young violinists imitate Heifetz's fingering on the necks of their instruments as they listen.

Figure 1. Scene from They Shall Have Music. Directed by Archie Mayo. Samuel Goldwyn Company, 1939. New York: HBO Video, 1992.

In his performance, Heifetz, with his back straight and sporting a stiff tuxedo, barely moves, apart from some minimal rocking back and forth. His face remains still and stoic throughout, and his technique is precise and clean. The students onscreen are no doubt amazed, along with much of the film's audience, by his technical ability, and particularly his fast and flawless performance of the slurred staccato passages. Indeed in the context of the speed and virtuosity required by the composition, Heifetz's demeanor makes his technique appear all the more effortless and impressive.

At the time They Shall Have Music was released, the published editions of “Hora Staccato” still credited Heifetz and Dinicu and mentioned Romania as the work's original geographic location of reference, but as time progressed, the piece gradually shed its associations with Eastern European Romany culture, appearing with increasing frequency in the context of U.S. jazz and swing. It was scored for trumpet and piano in 1944; in a dance arrangement for piano, strings, brass, and percussion by Paul Weirick in 1945; and for xylophone and piano in 1947. In some of these later editions, the word “Roumanian” was eliminated for the first time.

In the 1944 film Bathing Beauty, a vehicle for the comedian Red Skelton and swimming champion turned film star Esther Williams, the trumpeter Harry James performs “Hora Staccato” in a nightclub with his band. Prior to the performance, as guests enter the hall and mingle on the dance floor, the lights go dim and the emcee, a New York producer played by Basil Rathbone, emerges to introduce the performance with a description that refers back to the work's Romanian origins:

Ladies and gentlemen, next we present a musical phenomenon: some years ago, in a little café in Romania, Jascha Heifetz, the famous violinist, heard a Gypsy fiddler play a selection that made such an indelible impression on his mind that later, he wrote a brilliant adaptation of it. Tonight, for the first time, we present these—uh—violin fireworks as transcribed for the trumpet by Harry James. Ladies and Gentlemen, “Hora Staccato.”

The performance that follows opens with a brief introduction in the brass section, after which the strings play a descending scalar lick. The lighting highlights the violins and violas while mostly hiding the performer's bodies in shadow (Figure 2). Although this is an arrangement for the trumpet, the origin of the work in violin performance is thus implied at the start by the row of glowing violins, manipulated by disembodied hands. Harry James's performance of the solo, which alternates with recurring phrases in the strings, generally follows Heifetz's violin part, as James plays at a rapid pace, vibrating on longer notes and adding glissandi up to some of the higher pitches (Figure 3). At the conclusion of the performance, in an original coda that does not appear in Heifetz's score, the lights go on as James plays a long slide up to the dominant followed by the tonic in a high tessitura, below which members of the brass section hold a blue note on the lowered 7th scale degree.

Figure 2. Scene from Bathing Beauty. Directed by Sidney George. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1944. Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2007.

Figure 3. Scene from Bathing Beauty. Directed by Sidney George. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1944. Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2007.

The emcee's introduction to this swing performance of “Hora Staccato” suggests that Heifetz's composition is particularly valuable because he discovered the authentic melody at its distant source, in a “little café in Romania.” At the same time, however, the performance's immediate success had the effect of further severing new versions of the piece from its source. The 1944 trumpet arrangement was published without reference to Heifetz's discovery, instead simply identifying the music with the advertisement, “As Featured by Harry James in the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Picture ‘Bathing Beauty.’”Footnote 34

In 1947, a band arrangement by David Bennett was published with a new blurb:

“Hora Staccato” achieved instant success in its original form as an arrangement for violin and piano. While it is not, in its entirety, a “tune for humming,” the unusual treatment of the scale as a subject and the exotic style of the motifs in the second part make it “catchy” and hence easily remembered. It has appeared in many versions, including accordion solo, trumpet (featured by Harry James), viola, cello, saxophone, clarinet (featured by Benny Goodman), piano solo, and two pianos, and has now been issued as a popular song under the title “Hora Swing-cato.”Footnote 35

The piece's origins in Bucharest and the earlier implications of authenticity derived from the description of Heifetz's foreign musical encounter are here reduced to the words “exotic style of the motifs.” This introduction omits any details of the work's history, focusing instead on recent adaptations in the performances of Harry James and Benny Goodman, and the song “Hora Swing-cato.”

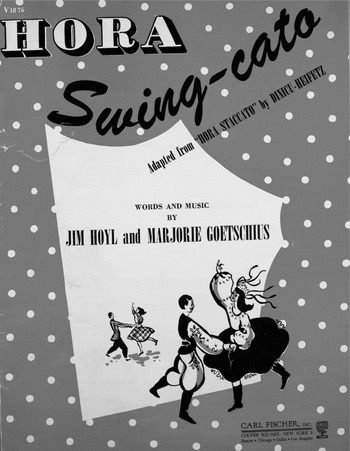

“Hora Swing-cato” had been published in 1946 by Carl Fischer. Its title was a hybrid of the original genre “hora” and the new genre “swing,” although the manuscript score of this new version shows that an initial experimental title was “The Horrible Staccato,” a name by which Heifetz was known to have called “Hora Staccato” because of its difficulty and ubiquity.Footnote 36 The title “Hora Swing-cato” is mimicked by the illustration on the polka-dotted cover of the sheet music showing two dancing couples, one in embroidered, ruffled representations of Romany traditional costume, the other in 1940s swing-dance garb (Figure 4). The song is attributed to Jim Hoyl and lyricist Marjorie Goetschius, who together had published two other songs in the same year, “So Much In Love,” and “When You Make Love To Me (Don't Make Believe),” which was recorded by Bing Crosby and also in a solo piano version by Heifetz himself. The daughter of music theorist and composer Percy Goetschius, Marjorie Goetschius was a known lyricist; Hoyl, by contrast, was new on the scene, and his identity remained a mystery until October 1946, when Heifetz revealed in Hollywood that he was the composer, using the name “Jim Hoyl” as a pseudonym, or, as one critic put it, a “nom de swing.”Footnote 37 Heifetz had written these songs, according to an article in Time magazine, “to prove how easy it was.”Footnote 38

Figure 4. “Hora Swing-cato.” Lyrics by Marjorie Goetschius, arr. Jim Hoyl. Adapted from “Hora Staccato” by Dinicu & Jascha Heifetz. Copyright © 1945 Carl Fischer, Inc. All rights assigned to Carl Fischer LLC. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used with permission. Cover image from The Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music at Johns Hopkins University.

The octatonic scales and evocative dissonances of “Hora Staccato” are replaced in this arrangement for piano and voice by swing chords and blue notes, forming the backdrop to the following lyrics:

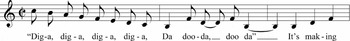

The perpetual motion of the violin part in Heifetz's score is condensed in “Hora Swing-cato” to a simpler, syncopated melody sung to scat-like nonsense vocables (Examples 3a and 3b).

Example 3a. Recurrent violin theme in Jascha Heifetz and Grigoras Dinicu, “Hora Staccato,” first heard in mm. 9–12.

Example 3b. Adaptation of violin theme in Jim Hoyl and Marjorie Goetschius, “Hora Swing-cato,” first heard in mm. 7–9.

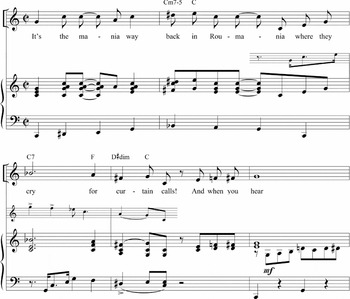

The initial selling point of “Hora Staccato” as a work derived from quasi-ethnographic research has been reduced here to the mere mention of Romania. In the bridge of the song, Goetschius's lyrics list people who have performed the melody, omitting Dinicu completely and giving Heifetz third billing, after Tommy and Sammy, presumably references to bandleaders Tommy Dorsey and Sammy Kaye. On the words “Where they cry for curtain calls,” Heifetz introduces a brief ossia staff that creates jazzy syncopated cross-rhythms with the other voices, perhaps a loose evocation of the patterns of Romany music (Example 4). Dissonances between the piano and ossia lines in m. 27, caused by the juxtaposition of F, E, and E-flat, produce the blue notes of swing music and refer obliquely to the modality of Romany numbers. In the text of “Hora Swing-cato,” the role of Romania is equally understated, reduced from the source of the melody to a far-away setting where the swing version of “Hora Staccato” also happens to be popular.

Example 4. Jim Hoyl and Marjorie Goetschius, “Hora Swing-cato,” excerpt of bridge.

Heifetz's most famous foray into composition was thus recast over time, as it became known in many circles as a swing melody, and was gradually divorced in numerous new editions and performances from the initially popular story of its origins as a representation of an ethnographic discovery abroad. At first, “Hora Staccato” was often interpreted as offering an accurate evocation of traditional Eastern European music, in performance through the display of virtuosity associated with Romany music making, and in print through its tale of origins as a composition borne of a personal cross-cultural encounter between musicians trained in Western classical and Romany popular idioms. As swing became popular and Heifetz and many of his listeners grew increasingly deracinated from European cultural origins in the United States, Heifetz's adoptive home, the adaptation of “Hora Staccato” to swing instruments and tropes perhaps seemed a logical course of development.Footnote 40 The successive versions of “Hora Staccato” show the evidence of increasingly hybridizing, fractured musical perspectives, as these renditions of the work gesture towards the nostalgia or exoticism associated with its Romany origins, and the assimilation, modernity, and cosmopolitanism believed to be embodied by U.S. popular music and the African American genres it incorporated.

Seymour Rechtzeit and the Yiddish “Swinging” of Heifetz's Repertoire

The notion that Heifetz and his music were caught between Eastern European roots and a new U.S. identity influenced the reception of his “itsy-bitsy” repertoire as well, as at least three miniatures based on Eastern European traditional music that Heifetz performed with particular frequency were transformed into popular arrangements in the 1940s in the context of Yiddish radio and sound recording. The Yiddish radio in New York, which first emerged in 1926 and remained active into the 1950s, was a quintessential product of the Jewish diaspora in the United States, representing in its intermixture of Yiddish- and English-language broadcasting and in the subject matter of its programming the foreign roots and new American identities of its multilingual and multigenerational Jewish audiences.Footnote 41 It appears that the miniatures in Heifetz's repertoire were sufficiently familiar to, or at least suited to the tastes of, Yiddish radio listenership to inspire their adaptation to the sounds of Eastern European folk music, klezmer, Yiddish musical theater, and jazz and swing.Footnote 42

On Yiddish radio, one of the most popular of these hybrid musical forms was known by the phrase “Yiddish Melodies in Swing,” a genre that typically involved the arrangement of Yiddish folk, theater, and religious songs as upbeat works in the style of American swing.Footnote 43 This resembled the common exercise among bands of the 1930s and 1940s of recreating classical works as swing hits, or “swinging the classics,” as well-known compositions by prominent composers entered the repertoire of band leaders including Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman.Footnote 44 “Hora Staccato” became just such a crossover tune, as heard in Harry James's rendition in Bathing Beauty, as well as in a unique arrangement for instruments and vocal ensemble by Fred Waring and His Concert Vochestra. In this version, recorded in 1945, the chorus sings sliding, syncopated hums and vocables in close harmonies as the violin section plays the solo part in unison, interrupted occasionally by a jazzy, rasping muted trumpet and a piano playing fast-paced riffs reminiscent of the sound of the cimbalom, the hammered dulcimer common in Romany ensembles.Footnote 45

Another innovative “swinging” of “Hora Staccato,” can be heard in a recording by clarinetist Dave Tarras and Abe Ellstein's Orchestra.Footnote 46 Abraham Ellstein was a Jewish American composer of Yiddish songs and scoring for Yiddish theater and cinema, including the soundtrack of the 1936 Yiddish hit film Yidl mitn fidl (Yiddle with His Fiddle), starring the popular singer, actor, and vaudevillian Molly Picon. Tarras, trained in his native Ukraine as a klezmer musician, gained fame after immigrating to New York in 1921, and incorporated Polish, Romanian, and Greek melodies, as well as swing techniques, into his klezmer performances.Footnote 47 In this recording, which produces a compelling hybrid synthesis between European classical, U.S. popular, and Eastern European traditional music styles, the small orchestra features prominent roles for piano and accordion playing off-beat rhythms that resemble both the syncopations of swing and the 3+3+2 rhythmic patterns associated with the klezmer dance genre of the bulgar, for which Tarras became known in America.Footnote 48 Tarras adds turns and trills to the solo part, and plays several long upward slides on his instrument, in a style that recalls both common klezmer technique and the opening gesture of George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue.Footnote 49

A number of the singers popular on Yiddish radio took up this practice of recreating classical works in the swing style with sentimental lyrics in Yiddish. The crooner Seymour Rechtzeit recorded and broadcast versions of Achron's “Hebrew Melody” and Sarasate's “Zigeunerweisen” with new lyrics in Yiddish by Rechtzeit's wife, Miriam Kressyn.Footnote 50 Rechtzeit's “Hebrew Melody” and “Zigeunerweisen,” released together on a 78-rpm disc in the mid-1940s, reconfigure these classical violin works—themselves arrangements of folk and religious melodies of European Jewish and Romany communities—into stylistic hybrids exhibiting characteristics of jazzy Tin Pan Alley numbers.Footnote 51 Even as these songs appear forward looking in their conversion of classical works into swing, their texts express diasporic nostalgia for the Old Country, and for a way of life that was lost in the displacement of Eastern European Jews across the Atlantic. Thus, while Heifetz's multiple versions of “Hora Staccato” appear to be an exercise in progressive Americanization, as the melody's Romany origins were gradually marginalized in order to reach a larger audience, Rechtzeit's arrangements of “Hebrew Melody” and “Zigeunerweisen” targeted a narrower listenership, turning wordless melodies into Yiddish-language anthems of diaspora.

In his arrangement of “Hebrew Melody,” Rechtzeit offers a text about an exile's longing for what he refers to as the “far-off East”: “Sounds are heard/ From far-off East, there/ Sounds enveloped in yearning/ With love from a heart that yearns/ An echo is heard/ Come back from that time/ When the ancestors from once-upon-a-time/ Gave us their treasures.”Footnote 52 The Hebrew melody of the title emanates from this distant space, and embodies the artistic theme of Jewish yearning for a distant homeland, referred to as the bride the singer left behind when he was displaced in exile. The song's accompaniment, performed by Abe Ellstein's Orchestra, features piano, strings, winds, and percussion playing gestures imported from Achron's composition as well as original material featuring instruments commonly heard in jazz and swing, such as the muted trumpet and glockenspiel, which alternately follow and diverge from the vocal line, punctuating transitions with diminished chords and arpeggios.

The muted trumpet plays the melodic line at the opening of the recording, and returns to perform in unison with the singer in several passages. The violinist, playing a version of the original violin part, performs a solo line above the orchestra later in the recording; when the instrument first emerges, it plays a solo riff on a descending diminished chord that resembles both figuration heard in recordings of sentimental American song and the augmented seconds common in klezmer's traditional modes.Footnote 53 At the end of this phrase, Rechtzeit enters again as the violin plays along with his singing, with both newly composed gestures and references to the solo part of Achron's original. Rechtzeit's coda, sung wistfully to the repeated syllable “Ah” followed by a final reiteration of the refrain “beautiful bride of Israel,” is accompanied by sparkling arpeggios on the glockenspiel. Achron's work, based on a melody he claimed to recall from a turn-of-the-century Polish synagogue, is adapted here for a Yiddish crooner with dance band accompaniment, and becomes assimilated to its new musical context, with the incorporation of elements—instruments, melodic and harmonic gestures, and performance styles—associated with popular music of the United States. Rechtzeit's song is a nostalgic emblem of the idealized Jewish past that is made also to embody the change, social assimilation, and cultural appropriation that were experienced by many Jews throughout the processes of emigration, displacement, and resettlement in the diaspora.

Sarasate's “Zigeunerweisen” was one of the best-known works in the genre of virtuosic violin arrangements of Romany melodies, often featuring as the final number on Heifetz's international recital programs. Here it is adapted as a song about love for a tsigayner meydl, or Romany girl.Footnote 54 Kressyn's lyrics open with the words, “When I overhear a Gypsy melody/ A song of love presses into my heart,” reflecting and perpetuating associations of Romany performance with passionate emotion.Footnote 55 Rechtzeit sings that when he plays his love song to his distant beloved, the strings of the violin cry from his heart, and he asks her, “Give me love, if for one minute/ Because with you it is so sincerely good.”Footnote 56 In the fast second half of the number, the singer describes his impassioned dance with the Romany girl, reflecting the age-old stereotype of the sensual dancing of Romany women: “Dance for me, my girl/ wildly let's dance . . ./ Two hearts, they pound without stopping/ Turn, girl, turn faster/ . . . Sing, Gypsy, jump, Gypsy/ Dance to my song.”Footnote 57

As in “Hebrew Melody,” the orchestration features the violin—the instrument associated with the original composition—and the muted trumpet, an instrument commonly associated with jazz and swing. Violins and trumpet play together in the brief introduction to the song based on Sarasate's original, and return between verses and sometimes at the same time as Rechtzeit's singing. Throughout the recording, the solo violin plays virtuosic runs from Sarasate's composition. In the middle portion of the song, based on the fast second half of “Zigeunerweisen,” the violin section plays fast virtuosic figurations in unison, calling to mind the violin parts in the versions of “Hora Staccato” by both Harry James and Fred Waring. Ellstein's band imitates the Romany ensemble, as filtered through Sarasate's nineteenth-century orchestration, but with instruments and harmonies associated with Tin Pan Alley. And as in Rechtzeit's “Hebrew Melody,” a downward solo lick on a diminished scale in the violin part interrupts all other voices at the climax of the performance, and links to the recapitulation of the opening material, with featured parts for violin, trumpet, and glockenspiel. In the final strains of the song, the glockenspiel plays a blue note over the minor tonic chord in the form of the sixth scale degree.

Although the songs addressed in this article call on different images and languages, they employ a similar metaphor, that of sound as the bridge linking new Americans back to Eastern Europe.Footnote 58 Rechtzeit's “Hebrew Melody” opens with the words “Sounds are heard/ From far-off East/ . . . An echo is heard,” and “Zigeunerweisen” with the line “When I overhear the Gypsy melody.” “Hora Swing-cato” begins, “It goes like this/ Diga-diga-diga-diga/ Da-do-da-do-da”; and in “Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha” Gershwin follows the violinists’ names with the words “fiddle-lee diddle-lee dee,” which, in addition to imitating the sound of the violin, and being an American nonsense phrase, plays on the Yiddish diminutive form of the word for violin, “fidele.”Footnote 59 By invoking the sounds of the violinist in Eastern Europe, these songs suggest that Old World melodies have found their place in a new musical context. The hybrid strains played in the styles of classical, klezmer, and Romany violinists become a metaphor for human displacement and assimilation. Like these song texts, a considerable component of Heifetz's reception history in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century embodied both orientalist nostalgia for the old country and enthusiasm for an innovative cultural hybridity in a new homeland. It also relied on the assumption that expression in performance resides in breaking through the façade of classical music's “highbrow” respectability to find an authentic, private core in which the performer's identity resonates uniquely with the musical material. This conception of performance stipulated that listeners could accurately conceive of the personal identity of a musician they encountered in recordings and live performances. The history of “Hora Staccato” and Rechtzeit's adaptions of miniatures in Heifetz's repertoire illuminate the ways in which the social processes of displacement and assimilation can lead to a particularly rich and complex form of musical adaptation and innovation.