On 28 February 1984, Michael Jackson stood at the pinnacle of his success. That night he won a record eight Grammy awards, including Album of the Year for Thriller and Record of the Year for “Beat It.”Footnote 1 Jackson was also recognized for his mastery in a variety of musical styles, taking home awards for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance (“Billie Jean”); Best Male Rock Vocal Performance (“Beat It”); and Best Pop Vocal Performance (“Thriller”). But arguably the most groundbreaking event of the evening happened between Jackson's repeated trips to the stage: during the commercial breaks Pepsi-Cola unveiled its latest attempt to win its decades long battle to beat Coca-Cola with a pair of television commercials, titled “The Concert” and “Street.” The commercials featured Jackson and his brothers singing the praises of Pepsi over an edited version of the instrumental backing track to “Billie Jean.” Months of media hype turned the unveiling of the commercials into an “event” not to be missed by Grammy viewers and fans—all eighty-three million of them.Footnote 2 Earlier that week, MTV contributed to the excitement by devoting a half-hour special to the premiere of the now infamous “Concert” commercial.Footnote 3 The craze for all things Michael Jackson had also been fueled by heavy rotation of his music videos on MTV and his riveting performance of “Billie Jean” less than a year earlier during the Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, and Forever television special.Footnote 4

Pepsi unveiled its new campaign at the precise moment when fans could not get enough of their favorite pop star. The 1984 “Choice of a New Generation” campaign became the first set of television commercials to successfully co-brand a musician's current album and upcoming tour with a household product.Footnote 5 Prior to this deal, specially composed jingles and the occasional “classic rock” song had dominated advertising soundtracks. Rejecting prevailing rock ideologies that made the use of current hit songs in commercials unappealing, Jackson's “Choice of a New Generation” commercials became so popular that according to Roger Enrico, Pepsi's CEO at the time, a year after their premiere ninety-seven percent of the American population had seen the commercials more than a dozen times.Footnote 6 In less than a month, Pepsi's sales had climbed high enough to make their product the fastest-growing regular cola on the market and the most purchased soft drink from grocery retailers.Footnote 7 The campaigns were also notable accomplishments in the advertising world: Barton Batten Durstine & Osborn (BBD&O) garnered seventy-four creative awards for the spots.Footnote 8 The venture paid off handsomely for Michael Jackson, too: Thriller stayed on the charts for more than two years, spent thirty-seven weeks in the number one spot, and became what is still the bestselling album of all time.Footnote 9 The buzz generated by the campaign was unmatched as networks begged for small clips of the commercials to air before their premieres at the Grammys and on MTV. Phil Dusenberry, the campaign's creative and musical director, believed it was “perhaps the first time in history when a commercial was more anticipated than the television show surrounding it.”Footnote 10 In Jackson's own words, the deal was “magic.”Footnote 11

According to memoirs, interviews, and media reports, Michael Jackson's savvy business skills and creative insight made the campaign successful.Footnote 12 First and foremost, his demand for $5 million significantly raised the going rate for celebrity endorsements, making future co-branding deals between musicians and corporate brands lucrative and desirable.Footnote 13 Second, Jackson refused to perform the jingle Pepsi's marketers had created for him and instead offered them the use of “Billie Jean.”Footnote 14 And despite the fact that marketers changed Jackson's lyrics for the spots, the inclusion of material from “Billie Jean's” instrumental backing tracks made Pepsi's version of the song familiar enough for fans to enjoy it. Third, Jackson claimed he was worried about overexposure and challenged Pepsi to represent him as an icon and performer rather than showing clichéd close-ups of him “enjoying” the product. Instead, the pop star allowed Pepsi to use his “symbols”—the iconic glove, red jacket, spats, and shoes made famous in his performances and MTV videos—in exchange for four total seconds of face time, one close-up, and only one of his iconic dance spins.Footnote 15 Finally, these commercials set a new modern marketing precedent because Jackson never actually touches a Pepsi: his endorsement of the soft drink is merely implied. The result was a campaign that appealed not only to the soda giant's targeted youth demographic but to Jackson fans of all ages by interweaving iconic visual and musical tropes that depicted the superstar doing what he did best: entertaining audiences.

Music and Meaning in Advertising

Current discussions about the appropriation of pre-existing popular music in American advertising are perhaps best summed up by Timothy D. Taylor's hypothesis that advertising had essentially “conquered” American musical culture by the twenty-first century. He and others critical of the industry no longer find a separation between the practices of creating popular music and the business of advertising.Footnote 16 Questions raised in contemporary conversations among music critics, scholars, and cultural theorists include: When and how did the inclusion of popular music in advertising become commonplace? For what reasons did advertising become involved in the creation, production, and dissemination of popular music? And what does this change mean for the future of popular music?

With regard to Pepsi's “The Choice of a New Generation” campaign, Taylor's work, along with that of sociologist Bethany Klein, investigates these questions through the study of branding and licensing practices.Footnote 17 Both authors posit that Pepsi's innovative appeal to youth through the employment of MTV sounds and images created lasting relationships between the music and advertising industries.Footnote 18 Klein situates these spots with subsequent pop star cola campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s and raises reservations about advertising's appropriation of pre-existing popular music. She worries that the ever-increasing influence of branding values on the music industry may have a detrimental impact on future cultural production.Footnote 19 Taylor frames the commercials within music's historical role in American advertising, arguing that what he views as the “conquest” of musical aesthetics and ideologies by today's advertising is a result of the gradual “convergence” of the two industries over the course of the twentieth century.Footnote 20

This essay expands on these accounts by performing a close reading that considers how the aesthetic reworking of Jackson's musical track and image proved essential to the success of Pepsi's campaign. Because Jackson offered Pepsi “Billie Jean” in exchange for limiting his face-time onscreen, the music was the central force for communicating the campaign's message. Historical accounts further confirm that it was the campaign's music and images that made it appealing to audiences and resulted in increased soda sales. Consequently, an investigation of how the music was appropriated into Pepsi's commercials and why it proved so convincing for audiences allows us to better understand critics’ concerns about American advertising's appropriation of pre-existing popular music. As the analysis below will show, it was marketers’ ability to get inside the musical text itself that allowed “Billie Jean's” backing track to successfully represent the brand's aims. In this way, this article addresses key questions about musical co-branding, including: What happens to pre-existing popular music and its meaning(s) for audiences when it is incorporated into commercials? And how does advertising change musical texts to serve branding agendas?

This essay seeks to bridge important conversations among disciplines about pre-existing popular music's role in commercials by using musicological inquiry to sharpen the critical tools established by leading advertising and cultural scholars. The pages below employ an interdisciplinary approach that incorporates formal musical analysis with formative cultural theory on advertising, MTV, and musical meaning in multimedia to investigate how Pepsi-Cola successfully spun Jackson's taboo tale of promiscuity, paternity, and betrayal into something considerably more innocuous that aligned with its family-friendly image.

My analyses are informed by seminal scholarship on American advertising's appropriation of cultural art forms. Studies of American popular music's role in commercials prove scarce when compared to the well-established body of literature available on representations of visual art and other cultural iconography in advertising. Disciplines such as sociology, psychology, and media studies have developed and circulated a substantial body of critical analysis on advertising practices since the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 21 In 1978, sociologist Judith Williamson demonstrated just how skillful marketers had become at spinning culturally constructed signs and signifiers to fit branding agendas. She argued that “advertisements use ‘meanings’ as a currency and signification as market . . . they can always exchange them, take anything out of its context and replace it: re-presentation.”Footnote 22 Her ideas prove useful here and are extended to an analysis of musical signifiers in Pepsi's commercials. They support a close examination of the ways in which Pepsi's campaign skillfully “re-presented” not only Jackson's celebrity image, but also significantly reformed the musical structures to allow “Billie Jean” to take on very different “‘meanings’ as a currency” from the ones carried by the original single.

This article also extends work done by sociologist Michael Schudson. In the same year that Pepsi's Michael Jackson commercials were aired, Schudson theorized that American advertising borrowed visual art and other cultural forms to abstract and redirect previously formed aesthetic meanings in order to fit branded contexts. His analysis demonstrated how marketers re-worked iconic images, including those of celebrities, to “simplify” and “typify” (break down and type cast) their signifiers to appeal to the widest possible audience.Footnote 23 Schudson's hypotheses are expanded here to demonstrate how marketers “simplified” and “typified” Jackson's music and star image in Pepsi's spots.

Williamson's and Schudson's theories pair well with formative inquiries into the semiotics of musical meaning in advertising.Footnote 24 Leading music scholars have argued that the transfer of meanings between music and images is a two-way street, whereby the music brings outside associations to the images, and the images have the potential to give new meanings to the music. In particular, Lawrence Kramer argues that how much and what meaning the music contributes to the reception of what he calls an “imagetext” depends both on how much prior experience the listener has with the music and how subordinate the soundtrack is to the visual elements.Footnote 25 He posits that music and images have the potential to bring various signifiers into an “imagetext” and that when taken together, these signifiers affect how each might be perceived.Footnote 26 Anders Bonde has more recently asserted that audience interpretations of pre-existing music in television commercials are made through “multimodal interactions” among various types of audio-visual texts to which the music has been re-contextualized (music video, film, commercials, etc.).Footnote 27 He further suggests the term “meaning potentials” as a means to examine the modification and negotiation of pre-existing music in various audio-visual contexts.Footnote 28 Taking these ideas together, the pages below perform a “multimodal” analysis of the “meaning potentials” for audiences who encountered “Billie Jean” both outside and inside Pepsi's campaign.

Michael Jackson's “Billie Jean”

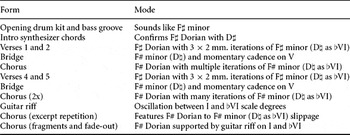

In his late-1980s memoir, Moonwalk, Jackson claims that he wrote “Billie Jean” to reflect the awkward situations his brothers found themselves in during their fame as the Jackson 5.Footnote 29 The lyrics lay out the scenario of a lover causing a “scene” (i.e., court battle) when she tracks down a former flame to tell him he is the father of her child. The song is the clichéd tale of the celebrity who falls prey to a dissatisfied ex- or “wannabe” lover, which evokes betrayal and lies through a skillful pairing of poetic lyrics with harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic instabilities. As the story unfolds, Jackson shifts the narrative among his past experience, flashbacks to his encounters with Billie Jean, and the story's moral lesson. The music emphasizes the seriousness of the storyline: the backing track continually gravitates toward the ♭VI to subvert desired or expected cadential closure; the ♭VI (represented by D♮) frequently disrupts sections in the F♯ Dorian mode, causing a strong pull toward F♯ natural minor; and the precariousness of the half-step oscillation of the sixth degree makes both modes unstable. As Table 1 illustrates, the constant slippage between D# and D♮ constantly redirects the harmonic movement, placing the mode in flux. Frequent moves to the ♭VI thus seem to work metaphorically to cast doubt on Jackson's claims of innocence by appearing at critical points in the story and subverting resolutions. In fact, resolution is something that the song never attains; the storyline is left open-ended and the harmonies never reach a satisfying cadence on a tonic.Footnote 30

Table 1: “Billie Jean” Form and Harmony Diagram. Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP. As the table demonstrates, the song generally follows an AABA format.

The “Billie Jean” story opens slowly, with a synthesized-sounding drum kit rock groove followed by a bass line that winds around what, at first, sounds like the tonic and fifth degrees of F♯ minor (Table 1).Footnote 31 When inverted synthesized F♯ minor and G♯ minor chords enter eight bars later, the introduction of the D♯ indicates that the bass line's hint at F♯ minor was misleading and that F♯ Dorian is actually the correct mode for this section (Example 1).Footnote 32 These chords build nervous energy as the top voices move up and down on a major second and pause precariously off the second beat of each measure. The careful addition of new timbral, melodic, and rhythmic layers over the course of the extended opening groove indicates that these individual textural elements are to be structurally important for setting up and supporting the song's tenuous storyline.

Example 1: Opening bass and synthesizer groove. Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP. Transcription by author.

As the verses unfold, Jackson interrupts testimony about his relationship with Billie Jean with brief metaphorical visions of “dancing” around her desires and accusations. These memories mysteriously float among past, present, and future encounters with her. The song's tension comes to the fore during these refrain-like interruptions by halting the tonal progression in favor of dark B minor-seventh chords that introduce the flat-sixth scale degree (D♮) and momentarily subvert the Dorian mode (Example 2, mm. 2–3). During these harmonic shifts, the bass line abandons its smooth eighth-note pattern by jumping over beat three to land safely on the familiar F♯—a move that seems rhetorically to “dance around” the B minor-seventh intrusion. These interruptions happen regularly in each verse (six in total) (Table 1). I would argue that the ♭VI works in conjunction with Jackson's narrative asides to cast doubt on and displace the Dorian mode, and further, that these visions of dancing around the antagonist can be interpreted as either a euphemism for their past sexual encounters, or simply as contradicting testimonies between Jackson and his accuser. Structurally speaking, these harmonic deviations foreshadow an upcoming move to F♯ minor in the bridge.

Example 2: Dancing around the ♭VI and the bridge shift to F# minor. Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP. Transcription by author.

The D♮ makes its most intrusive appearance on the downbeat of the bridge, where Jackson tells the moral of his story (Example 2, mm. 6). Here the groove drops out and the ♭VI becomes the root of D-Major chords that trick us into hearing it as a temporary tonic. However, the motion here actually changes the mode from Dorian to F♯ minor. Up to this point Jackson's voice has remained in a comfortable middle range, but here he highlights the tension in the lyrics by driving his voice into the upper octave and changing the metric accent from off-beats to the downbeats as sustained block chords support his warning against playing lovers’ games. Jackson's vocal line creates even more tension by singing the word “careful” on the intrusive sixth degree (Example 3). The D♮ acts deceptively throughout the bridge as the VI chords resist cadencing through the dominant until the last possible moment. Once the C♯ major chord finally appears in the last measure of the bridge, it heightens the dramatic action by illuminating cautionary words about the nature of lies and sexual advances. These two assertions of the dominant provide the only “true” cadential points in the song. The resistance to authentic harmonic resolution here thus aurally supports the deception described in the storyline.

Example 3: ♭VI warning and half-cadence on C#. Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP. Transcription by author.

At the arrival of the chorus, the opening groove is reinstated to push the song back into F♯ Dorian, making the bridge sound like a temporary detour (Table 1). The decision not to stay in F♯ minor renders the song's turmoil irresolvable because the ♭VI continues to reappear and be suppressed. In fact, the unstable harmonic motion from the verses returns here to alternate between the F# Dorian and F# minor modes with intrusions of the D♮ in the synthesizer (similar to Example 2, mm. 2–3). During these minor-mode passages, Jackson repeatedly denies paternity, despite the lack of an alibi. However, the vocal line complicates the lyrics here as he sings in a highly syncopated fashion and lands squarely on D♮ on the possessive pronoun “my” (Example 4). Jackson thus takes brief ownership of the ♭VI, alluding either to the extent of Billie Jean's betrayal or his own guilt.

Example 4: Jackson sings the ♭VI (D♮) to assert his position as “the accused.” Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP. Transcription by author.

Further adding to the precariousness of the storyline, dreamy-sounding synthesizer flourishes interject to dance once more around D♮ (Example 5). The falling F# minor arpeggio (which never stops to rest on the C#) repeats several times, seeming to question Jackson's declaration of innocence. These little melodic frills act as musical echoes of the protagonist's struggle to deny the opening Dorian mode and therefore help to keep the song's modal center—and thus its overall “truths” or “meanings”—unclear.

Example 5: Synthesizer flourish. Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP. Transcription by author.

We are left guessing how the story ends as the song fades out on Jackson's famous denial of any romantic relationship with his accuser. A guitar riff accompanies the line by moving between the tonic and ♭6 scale degrees. The ability of “Billie Jean” to maintain harmonic tension throughout thus effectively supports the anxiety and uncertainty fundamental to its storyline.

Jackson's music video for “Billie Jean” notably does little to resolve the questions raised by the song. If anything, the video heightens uncertainty by depicting the pop star as a mysterious yet magical man who is impossible to pin down. The final scenes of the video even seem to call Jackson's proclaimed innocence into question by showing him getting into bed with an unknown person and disappearing. He eventually emerges as a tiger, enacting the metaphor of a man's sexual appetite being like that of a wild beast, and then vanishes into the night.Footnote 33

When considering the implications of the messages conveyed in the original song and video, it is highly unlikely that Pepsi would ever be willing to associate its brand with these sordid situations. It is not surprising then that Pepsi would decide to go in a dramatically different direction with the song. As the following sections demonstrate, in addition to changing Jackson's lyrics to “Billie Jean,” Pepsi's marketers were able to eliminate much of the musical tension and ambiguity built into the single by cutting out volatile structural moments.

MTV Aesthetics and Michael Jackson's Iconicity

The soda giant made two commercials that captured only the positive aspects of Jackson's celebrity image and the catchiest sections from the backing track to “Billie Jean.” Memoirs by Roger Enrico (Pepsi's CEO) and Phil Dusenberry (Creative and Musical Director for BBD&O) as well as my interview with Bob Giraldi, the director of the spots, substantiate that Pepsi banked on the fact that much of its national audience would recognize “Billie Jean.” Marketers therefore attempted to encapsulate the “essence” of Jackson's superstar persona by co-opting and controlling as many of his musical and visual signifiers as they could. These sources also indicate that the soda giant was clever to pick up on a trend, later noted by musicologist Andrew Goodwin and sociologist Jaap Kooijman, that mid-1980s audiences favored performances and texts that re-created music video imagery.Footnote 34 In fact, Pepsi's marketing team strategically hired Giraldi, then a top music video director, to film the campaign in a way that embraced the facets of performance spectacle most important to the emerging aesthetic of MTV.Footnote 35

Goodwin argues that musical aesthetics in the 1980s became increasingly dependent on images after MTV and other video formats redefined the matrix of meaning in popular music from the sounds alone to include the visual aspects of an artist's image and performance.Footnote 36 As a defining characteristic of MTV programming, this change was fostered by the increasing reliance on the pairing of visual iconography with recorded sound. Although it is debatable how novel this “imagetext” for pop music was (Kramer traces its roots back into the history of opera), Goodwin is right that new music-making technologies helped redefine 1980s musical performance as a visual experience that centered on image.Footnote 37 Kooijman echoes Goodwin in his analysis of Jackson's Motown 25 performance and subsequent re-enactments of that night. He argues that Jackson's performance marked a turning point in popular music aesthetics, in which the audience was fascinated not by Jackson's musical skills (considering that he lip-synced his hit song), but by the way he looked and moved onstage.Footnote 38 Eighties pop was then realized and experienced more than ever before through the onstage spectacle of costuming, elaborate sets, and dancing.Footnote 39

Jackson's appearance as the performer therefore added an important level of signification to his music. Pepsi, however, faced a considerable challenge when Jackson instructed the soda giant to use as few camera shots of his face as possible to represent him. Luckily for the corporation, Jackson's music had become an aural representation of the spectacle of his performances to many fans, which allowed his images and sounds to mutually refer to one another. Similar to the way scholars have discussed Hollywood icon Fred Astaire (to whom Jackson has often been compared), both Kooijman and historian Kobena Mercer note that isolated aspects of Jackson's appearance (his costuming in particular) and his bodily movements and gestures (especially the moonwalk) work even today to signify him.Footnote 40 Kooijman argues that in the years following Thriller’s release, the pop star himself became a “postmodernist sign, a visual representation.”Footnote 41 He concludes by saying that the pop star's visual signifiers had the ability to work separately from his voice and music to act as representations of his performances and/or performing self.Footnote 42 Due to the fluidity of his signifiers, it would make sense then that any of Jackson's three primary areas of signification—his physical appearance, dancing, and music—could effectively stand in for and/or represent the other aspects of his performing persona.Footnote 43 This point is supported by the fact that Jackson openly acknowledged to Pepsi that his “symbols” could stand in for him (i.e., his costuming and signature moves), making it obvious that he knowingly and carefully crafted these signifiers to become representational parts of his pop-star image.Footnote 44

Pepsi's “Choice of a New Generation” campaign certainly exemplified MTV's musical and visual aesthetics. In both “The Concert” and “Street” commercials, Jackson's presence is largely implied as the camera focuses on his “symbols” while portions of his musical track work to fill in the visual gaps. The analysis below will show how, as Michael Schudson would put it, “simplified” and “typified” musical fragments of “Billie Jean” are paired with Jackson's images to allow the commercials to be accepted as featuring the “King of Pop” despite the fact that his face was only on screen for a few brief seconds.Footnote 45

Pepsi's “Billie Jean”—“The Concert” CommercialFootnote 46

In his autobiography, Enrico described how Pepsi and BBD&O designed the first spot, “The Concert,” to look:

The commercial starts with the Jacksons—but not Michael—drinking Pepsi and relaxing in their dressing room before a concert. There's a flash of Michael in front of the makeup mirror, and then we move behind the stage, where Michael's about to make his entrance, and we are tantalized anew with glimpses of Michael's look—his symbols. Then the set opens, and with a flash of fireworks, Michael dances and spins into a full-fledged concert, singing the reworded “Billie Jean” to a mob of screaming kids in the audience.Footnote 47

Enrico's account captures the commercial's attention to spectacle and movement. As a whole, the spot cultivates excitement by rapidly progressing through a montage of frames that depict a youthful audience gearing up for a concert, the Jacksons getting ready to perform, and Michael Jackson's “symbols” interspersed with Pepsi's. The camera works to keep the images moving at a pace equal to that of the music's soundtrack by cutting sporadically among the bustle backstage, screaming fans, and the staged excitement of the concert. The piecemeal style of editing used here is similar to that of music videos: the cinematography never focuses on any one scene for more than a few seconds as it works to manipulate the viewer's sense of moving through time.Footnote 48

The commercial opens with a panning shot over a sea of spectators. A pared-down version of “Billie Jean's” opening groove begins the soundtrack. Here the aggressive synthesized backbeats heard the original are replaced with a much lighter snare figure that gently accents beats one and three (Table 2). The song's distinctive bass riff, which is noticeably more prominent in this arrangement, enters next to accompany the bustle backstage and glimpses of Michael Jackson's white glove and sparkly jacket, reminiscent of his already famous Motown 25 costume (Figure 1).Footnote 49 At the entrance of the Dorian-inflected synthesizer chords (Example 1), quick cuts to Jackson's other iconic “symbols” are woven between clips of his brothers sipping from Pepsi bottles and cups. In the original track, these synthesizer chords set up the song's tonal tension, but here the imagetext clearly gives them a positive connotation, complementing the anticipation and energy displayed by the performers and the crowd.

Table 2: Original “Billie Jean” and Pepsi Commercial Comparison. Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP. “The Concert,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984.

Figure 1: Commercial still: Michael Jackson's iconic glove. “The Concert,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984.

The first two stanzas of Pepsi's slogan enter two measures later and are mapped onto the bridge of “Billie Jean” (Table 2). Departing from traditional marketing practices where the slogan material is intended to be remembered, Pepsi mixed the instrumental track at a higher volume than its new lyrics to increase the likelihood that audiences familiar with Jackson's music could easily recognize the tune and make the association with the hit single. Although the slogan played a lesser role in hooking viewers than Jackson's re-mixed track, marketing executives worked diligently with the superstar to ensure that the commercial's new words complemented the company's long-standing history of lifestyle advertising.Footnote 50 The verbs used—dancing, grabbing, lovin’, etc.—evoked the vitality that Pepsi ascribed to their “New Generation” of consumers. When substituted over the backing track of “Billie Jean,” their poetic meter lines up perfectly with the harmonic changes on the downbeats to highlight key action words and the product name. In the original version, Jackson shifted the metric accents in this bridge section to give weight to the story's stern moral lesson. But in the Pepsi spot, they emphasize the carefree, positive message of the brand.

To make “Billie Jean” fit within the confines of a sixty-second ad, Pepsi simply cut out the song's verses. This move is not only practical and efficient (the song's most identifying features are notably the riff and the chorus hook), it is also aesthetically pleasing because it effectively eliminates the tension created in the verses by removing the struggle between the D# and D♮ (the Dorian mode and an intrusive ♭VI). The resulting splice from the opening groove to the bridge causes the prominent D major chord (♭VI in the original song) to sound unambiguously “major” and exciting, especially in the context of the images and Pepsi's re-worked lyrics (Table 2). It is here where Schudson's, Williamson's, and Bonde's theories can work together to illuminate how the “simplified” and re-arranged musical fragments “re-present” the song's signifiers in a way that creates new “meaning potentials” for the commercial version of the track.

Visually mimicking the commercial's slogan, Michael Jackson acts out the phrase “Put a Pepsi in the motion.” As a tracking shot follows his sparkly white socks and black loafers, he dances through a tunnel of backstage fans holding Pepsi cups (Figure 2).Footnote 51 The camera then cuts to images of his brothers running onstage. Just before the stars come into view, an announcer's voice cuts through the music to introduce them, causing the crowd to go wild.

Figure 2: Commercial stills: Michael Jackson's iconic socks and loafers; Pepsi's “New Generation.” “The Concert,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984.

Jackson's recognizable sequined jacket finally comes into focus on the key phrase of Pepsi's newly re-worked lyrics, which encourage viewers to choose Pepsi (Example 6). This phrase is harmonically highlighted by the first and only time that the aurally and structurally satisfying C# dominant chord is heard in the commercial. By minimizing the Dorian vs. minor harmonic uncertainty and putting musical and visual emphasis on a strong structural dominant, Pepsi and Jackson musically encourage their target demographic, represented in the diverse faces of the onscreen audience, to take action and buy their product. At this point Pepsi's slogan conspicuously replaces Jackson's lines about deceit and sexual advances with an encouraging slogan about drinking its soda (Example 6). This moment thus stands as one of the most emblematic examples of the way advertising can effectively forge new contexts for familiar musical signifiers.

Example 6: Jackson’s ♭VI warning (top) is replaced with an innocuous slogan about soda (bottom). Michael Jackson, Thriller, Epic, EK 38112, 1982, LP and “The Concert,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984. Transcriptions by author.

Another substantial difference between the original song and the commercial's version is brought out when the postponed dominant in the bridge now moves to an exciting climax at the downbeat of the commercial's chorus (Example 7, mm. 1–2). Pepsi's rousing images and welcoming slogan work to downplay the precarious alteration between minor and Dorian modes (Table 2). At this climactic moment in the spot, the onscreen audience members jump to their feet as they finally get a clear view of Michael Jackson, who hails them as the “Pepsi Generation.”

Example 7: Dominant C# in bridge sets up Pepsi’s chorus slogan. “The Concert,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984. Transcription by author.

Amid the pandemonium and pyrotechnics, the music becomes fully diegetic as the Jackson brothers entice fans to drink Pepsi (Figure 3). The word “thrill” is syncopated and sung on the highest note heard thus far, aurally elevating the excitement for the product and subtly reminding viewers of Jackson's hit album, Thriller (Example 8). In the original song, this passage falls on the accusation: “She says that I am the one.” The commercial version changes the meaning potential of the original song even further by diffusing the ♭VI on the second syllable of the product name, allowing the precarious note to highlight the brand instead of bearing the weight of Jackson's denial of paternity (compare Example 8, mm. 2–3 with Example 4). Further, the synthesizer motives that “danced around” the deceptive ♭VI are typified and lose the rhetorical function they had in the original track, now acting as merely recognizable, glittery ornaments, much like the sequins on Jackson's costume.

Example 8: Jackson’s hook is re-worked into Pepsi’s slogan. “The Concert,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984. Transcription by author.

Figure 3: Commercial still: Michael Jackson enters the stage and sings with his brothers. “The Concert,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984.

Finally, following a close-up of each performer, the vocal line loops back to the opening measures of the chorus to reiterate the viewers’ position as targeted consumers. The music decrescendos while the commercial's slogan, “Pepsi. The Choice of a New Generation,” slides to the center of the screen over a sea of screaming fans. The commercial's soundtrack ends the same way as the album version of “Billie Jean,” fading out on the repetition of the hook, underpinned by the rhythmic guitar vamp that oscillates between the F♯ tonic and ♭VI.

“The Concert” operates like MTV fictionalized performance videos that use close-ups and tracking shots of backstage footage to put the viewer on a more personal level with the musicians.Footnote 52 Pepsi's concept of youthfulness is also displayed onscreen in the faces of the concertgoers and performers and perpetuated by the energy expressed in the lyrics and musical track. By ending on a shot of a pumped-up crowd, the images leave viewers hanging in suspense, unable to experience the entirety of the performance that is presumed to continue after the camera stops rolling.

Pepsi's “Billie Jean”—“Street” Commercial

Pepsi's second commercial, “Street,” offers yet another interpretation of “Billie Jean” and Michael Jackson's iconicity by placing him and his brothers in an urban neighborhood. This spot mimics music videos in which audience members embody the personas of their favorite performers.Footnote 53 Much of the music in “Street” is the same as “The Concert,” except for an extension of the opening groove that gives the camera more time to set the scene. Prior to the groove's entrance, extramusical sounds such as car horns and video arcade noises sonically place the action in a busy city street.

Pepsi's version of the opening groove of “Billie Jean” (Table 2) then gives way to a glimpse of Michael Jackson once again wearing his iconic “symbols” as he stands just behind Pepsi's logo in the window of a pizza place. A quick cut to his sparkling white socks and black loafers sets off the re-worked groove to promote an energetic pace for the ensuing bass riff (Example 1). At the entrance of the bass line, a dozen children happily bounce into the street wearing outfits resembling those worn by the rival gangs in Jackson's “Beat It” video (Figure 4). One of them carries a boom box, suggesting that the music in the scene is diegetic and that the children are dancing to the original version of “Billie Jean.” Multiple shot-reverse-shots create an eye-line connection between images of the Jackson brothers hanging out and images of the kids drinking soda while they dance. Jackson's glove comes into focus the moment the groove's synthesizer chords enter the soundtrack (Example 1 and Figure 4). The linkage of his most famous symbol with the opening Dorian riff perfectly pairs Jackson's typified musical and visual signifiers. This moment solidifies his iconicity and confirms for the viewer that the song is indeed “Billie Jean.”

Figure 4: Commercial stills: Kids listening to “Billie Jean” while drinking Pepsi; A glimpse of Jackson's glove. “Street,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984.

A boy then slides out of a doorway dressed identically to Jackson's character in the video for “Beat It” (Figure 5).Footnote 54 As the child makes his way into the street, he performs all of the pop star's signature moves. Michael Jackson's voice enters at this point with the first phrase of Pepsi's slogan placed over the bridge to “Billie Jean” (Table 2). Direct word painting occurs when the children's dancing onscreen is synced with this re-worked bridge phrase.Footnote 55 After one of the Jackson brothers spots them, the Jackson 5 walks out to join in on the fun. Just before the two groups collide Michael Jackson sings, “Put a Pepsi in the motion.” At that same moment, the boy begins to moonwalk as he dramatically gulps from a Pepsi can. The impersonator's reward for literally putting his Pepsi into “motion” is that he unknowingly slides into his idol. The boy turns around on the dominant C# to see Michael Jackson. The “King of Pop” then sings the chorus directly to the astonished children, identifying them as Pepsi's new generation (Example 7, mm. 2–3).

Figure 5: Commercial stills: Michael Jackson meets his impersonator and the Jacksons dance with their admirers. “Street,” PepsiCo. Inc., 1984.

For the remainder of the chorus, the boy and his friends eagerly perform side by side with the famous brothers (Figure 5). It is no coincidence that the performance here resembles the final dance number in “Beat It,” because the commercial's director and choreographer had also worked with Jackson on the music video.Footnote 56 What is obviously different is Pepsi's replacement of violent street gangs with children and the Jacksons—one of America's most friendly family acts. And much like the conclusion of “The Concert” spot, the concluding guitar riff and final images suggest that the Jacksons serve as a guide for future Pepsi consumption.

Taking the two commercials together, it is clear that Pepsi distanced itself from implications of adultery, deceit, and legal obligations laid out in Jackson's version of “Billie Jean” by showing only positive images and rewriting the lyrics. More importantly, marketers isolated the song's most distinguishing musical features, including the opening bass riff and synthesizer chords, bridge, and chorus because they knew experienced audiences would recognize them. The analysis above demonstrates how “Billie Jean's” track was disassembled, simplified, and typified—the parts were separated from the whole—and arranged in a way that re-presented their structure and, as Williamson and Schudson remind us, their meanings.

To summarize, marketers created a positive version of the song by re-arranging these snippets in a way that did not allow harmonic or melodic subversions from the original to function in the same way. The transformation was achieved first by re-working the opening groove, which included shifting the metric accent to make the drums sound less aggressive (i.e., more friendly) and increasing the prominence of the recognizable bass line (Table 2). Second, the tension set up in the original with the careful unfolding of the opening groove and intrusive synthesizer flourishes during the chorus merely functioned in the commercials as short, isolated, and typified sound bytes, causing them to lose their rhetorical functions (Examples 1 and 5). Most prominently, the commercials simply lacked the original verses, eliminating the immanent conflict created by the opposition between the natural minor and Dorian modes (Table 2). And because Pepsi's version left out the verses, the tension in the new track is understated from the very beginning: the introduction of the major ♭VI chord on the downbeat of the bridge does not sound strikingly volatile, but instead exciting and positive when paired with the onscreen images (Table 2). Even though some harmonic tension and ambiguity is preserved in the sections left intact, in its new context, the pivotal ♭VI actually works to delay gratification for Pepsi's product instead of manifesting unresolved anxiety. Finally, the subsequent bridge arrival on the dominant achieves at least a partial resolution as viewers finally get a good glimpse of Michael Jackson and learn the “moral” of both commercials: to drink Pepsi (and not Coke). Pepsi therefore cleverly combined its friendly slogan and exciting onscreen images with pieces of the song's most memorable moments to promote an excited energy for the product and performers rather than an anxious stewing about deception and illegitimacy. The soda giant's ability to pick “Billie Jean” apart, simplify and typify its themes, stitch them back together, and re-present a new version to audiences altered the song's original meaning potentials and suggested that Pepsi was as hip to MTV and the latest youthful trends as to its superstar endorser and his fans.

Capitalist Realism and “The Choice of a New Generation”

Cultural theorists Stephen Goldman and Robert Papson hypothesize that viewers of television commercials decipher meaning based on what they call “alreadyness”—the previous knowledge brought to a commercial's sounds and images.Footnote 57 When extended to the analysis above, it would seem then that the soda giant assumed that experienced viewers’ “alreadyness” of Jackson's hit song would make the campaign's soundtrack readily identifiable. Hearing snippets of “Billie Jean's” catchiest tropes thus presumably allowed audiences to bring what they knew about it into the context of the campaign, giving them the potential to simultaneously recognize portions of the original song and make new connections with it in the branded context. The success of these efforts are validated by the fact that 1980s media accounts of the campaign did not seem to notice (or at least comment) that Pepsi had changed the words, despite the fact that viewers admitted to knowing Jackson's original track.Footnote 58

The overwhelming popularity of the campaign and the increase in Pepsi sales indicate that the presence of both the visual and musical elements of Jackson's persona in Pepsi's commercials offered audiences a convincing and entertaining depiction of the star. What remains puzzling, however, is that well-informed audiences—i.e., fans familiar with “Billie Jean's” original storyline and mysterious video—did not ridicule the song's placement in the spot, but seemed to willingly reconcile the contradictory meaning potentials created by Pepsi's re-presentation of Jackson and his music with their knowledge of the song in other contexts.Footnote 59 Even if the campaign was received purely as entertainment, how was it that the appearance of Jackson and portions of his backing track fostered acceptance of Pepsi's reconstruction of the pop star with its product: i.e., how did audiences accept that the soda giant twisted Jackson's celebrity by showing him as an endorser of a product he did not drink and changed his cautionary lyrics about the risks of fame to a more blandly inclusive message about an ideologically constructed “generation” of consumers? More specifically, how were viewers persuaded to literally buy into Pepsi's claims by such a substantially redacted and reconstructed version of the original “Billie Jean”?

I would argue that these discrepancies were reconciled in the fabricated worlds created by advertising under what Schudson called “capitalist realism.”Footnote 60 Schudson viewed the practices of American advertising as similar to those of Soviet socialists, where cultural art forms and ideas were simplified and typified into propaganda that supported government agendas. His notion of “capitalist realism” therefore suggested that late-twentieth century advertising also worked to strip down the complexities of American art to propagate streamlined messages to consumers about corporate products. When extending Schudson's argument to pre-existing popular music's role in advertising we can see how marketers were able to strip a complex, modern song down to its most recognizable, generic bits and rearrange them to fit sixty- to ninety-second spots. The success of Pepsi's commercials thus suggests that viewers accepted what was presented to them on the terms of capitalist realism, knowing on some level that the scenes of Jackson performing were not real, that his life as an entertainer was itself fabricated, and even that the song in the commercial was not “Billie Jean.” And by further expanding Williamson's theories about signifiers in visual advertising, it is clear that a generic re-presentation reconfigured “Billie Jean's” most recognizable sonic signifiers to make a version that celebrated passive consumerism. Thus, Pepsi and Jackson created a new and striking example of capitalist realism that fit well within the constructed fantasy world of youthfulness, soda, and pop music. In this way, “Billie Jean's” tale of betrayal was made suitable and appealing to cater to both Jackson's and Pepsi's core audiences through a careful manipulation of the original musical text.

Pepsi's Legacy

Pepsi's “Choice of a New Generation” campaign with Michael Jackson created a template for a new kind of celebrity endorsement—one that featured top performers singing new and current hit songs to endorse their recordings alongside corporate products. These co-branding efforts proved for the first time that musical celebrity endorsements could be lucrative for sales in both industries, and their overwhelming success indicated that consumer sentiment about musicians appearing in commercial contexts had begun to shift. It was obvious that teenage MTV viewers were not only eager to consume music and material goods together, but also that they offered notably fewer criticisms of these endorsements than previous generations had showered on past artists and marketers who had similarly “sold out” iconic images and music to promote goods.Footnote 61 Additionally, Pepsi's decision to hire the star for an extraordinary fee significantly increased the amount of publicity, money, and potential record sales for endorsements and sponsorships by big name musicians. In the desire to match the quality of advertising Pepsi had financed, other companies rushed to pour more money into their own advertising budgets.Footnote 62 Many corporations (including Pepsi's rival, Coca-Cola) scrambled to hire well-known musicians for their campaigns, and some offered two to three times what Pepsi had paid Jackson in an attempt to gain the same level of notoriety.Footnote 63 The increase in cash flow resulted in good press for highly paid musicians and corporations that could shell out millions to hire them, allowing brands that offered the right deal at the right price to attract top musicians.

Perhaps most importantly, Pepsi changed the way that the advertising industry did business by working as diligently to (re-)present Michael Jackson and his music as much as their own product. The level of control Jackson maintained in the production allowed future stars to have more input in the creative aspects of the spots in which they appeared. By forcing Pepsi to work harder than ever to please their star, Jackson persuaded marketers to be more imaginative and proved that celebrities did not even have to touch a product to represent it well. This new marketing style gradually replaced older unnatural and staged endorsement techniques.

Finally, the attention that Jackson's sponsorship attracted indicates that his commercials were not viewed simply as product endorsements, but as highly efficient mini-music videos. BBD&O's creative director reflects:

Critics say that when an ad agency resorts to celebrity advertising, it's a sign that the agency is out of ideas. That's true if you're still locked into the 1950s, plunking a familiar face . . . in front of the camera to read provocative lines. . . . But we . . . [used] the biggest one we could find and put him . . . in a carefully scripted scenario that functions like a mini-movie, with a beginning, middle, and end.Footnote 64

Indeed, the costuming, sets, dancing, and performance of a hit song by a young star all helped these commercials look like music videos. Furthermore, the energy evoked by the melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and new lyrics coupled with the fast-paced editing, enthusiasm of the performers, and excitement of the onscreen audiences and actors emulated the very essence of MTV programming.

“The Choice of a New Generation” created new possibilities for incorporating pre-existing popular music in television commercials and solidified relationships between the American music and advertising industries. The precedents set by this campaign have continued well into the twenty-first century as evidenced by the fact that musical co-branding has become the norm for corporate commercials. Twenty-seven years after its premiere, Pepsi re-invoked the campaign's significance by featuring clips of both commercials during a promo for its sponsorship of the inaugural 2011 season of the X Factor singing reality show. Glimpses of Jackson's sparkly socks and black loafers from “The Concert” (Figure 2) led viewers through three subsequent decades of the soda giant's musical endorsements by young talents like Britney Spears and Kanye West, whom it dubbed Pepsi's “Music Icons.”Footnote 65 The commercial not only confirmed the degree to which Pepsi's 1984 campaign with Michael Jackson had influenced the sights and sounds of American corporate advertising, but also opened the door for advertising's increased stake in the promotion of pop music's biggest stars in the new millennium.