In October 1923, the recent Russian émigré and future New York big band leader Basil Fomeen (1902–1983) played Russian folk songs on his accordion for the opening night of Manhattan's Club Petroushka. Located off of Park Avenue along a fashionable stretch of East Fiftieth Street in Midtown, Manhattan, the club had been transformed from an old mansion into one of the numerous nocturnal playgrounds then proliferating throughout the Prohibition-evading city. Past the double doors of the stately stone façade, one entered another world: adorning the walls were larger than life murals of Russian merchants eating and drinking, beckoning guests to likewise indulge; on one side of the club stood a floor to ceiling tiled stove, decorated with embroidered cloths and a tall samovar; while in another corner, musicians in white caftans, colorful skirts, and woven birch-bark shoes sang Russian folk songs as guests dined beneath the scenes of jovial merchants. With its depictions of the “grotesquerie of the Great Steppes,” the main dining room undoubtedly impressed patrons. However, it was the so-called “Gypsy Room” that completed what onlookers described as the “exotic” experience.Footnote 1 Decorated with colorful tapestries, an artificial campfire, and a wagon, the Gypsy Room featured nightly entertainment by a “troupe of Russian Gipsys” [sic] whose performance, according to one newspaper report, provided the “seeker after unique things something to go home and talk about.”Footnote 2 In its total experience, Club Petroushka hence presented New York patrons with the Russian exotica then in vogue—an encounter with an amalgamated Otherness associated with a mythologized Imperial Russia, enacted by refugees from the recent Bolshevik Revolution (1917) and ensuing civil war (1918–1922).

The fantastical experience offered by the Club Petroushka immediately enthralled New York socialites and notables such as George and Ira Gershwin, Jascha Heifetz, Charlie Chaplin, and Harpo Marx. Yet the draw of Club Petroushka—though specific in form—was not unique in Prohibition-era Manhattan. Instead, it served as part of a broader trend among New York elites for spaces that transcended the mundane and cast their occupants into worlds of fancy. Describing the transformative potential of Manhattan's nightclubs, Stephen Graham wrote the following in 1927: “You take a step to one side, pass a doorway, and you are in a different world. . . . Inside all is unreality, sentiment, indulgence and relaxation. New York has been banished. . . . In [its] place is dreamland . . .”Footnote 3

It is this transformative process at work in New York's 1920s nightclubs—the metamorphosis into “dreamland”—and music's central role in it that I explore in this essay.Footnote 4 In particular, I demonstrate the salience of so-called “Russian Gypsy” music in constructing this “different world.” Focusing on Club Petroushka as a notable case study, I examine the music, memoirs, and performance practice of the club's musicians; material detailing the club's conception and interior; and reviews and advertisements in Russian American and other newspapers and magazines to document a largely forgotten trend in New York's nightlife—that of the Russian émigré nightclub—and to unpack the complex negotiations at work in the performance of Russian Gypsy music within the context of the multifaceted first wave Russian diaspora, a group consisting of the approximately one and a half million people who fled Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution and whose ethnic makeup included Russians, Roma, Jews, Ukrainians, Kalmyks, Georgians, and other ethnicities comprising the cultural tapestry that had made up Imperial Russia.Footnote 5

Indeed, Russian Gypsy music has had a tangled and complex history since its emergence on Russia's stages in the late eighteenth century. While Roma had lived in what would become the Russian Empire since at least the sixteenth century, it was not until the establishment of the first known “Gypsy Choir” by Count Aleksei Orloff (1737–1807) in 1774 that Romani musicians had an increased presence in Russian culture, instigating a love of Romani music that culminated in a “Gypsy mania” (tsyganshchina) that dominated popular culture through the early twentieth century. It must be noted, however, that Roma in Russia did not constitute a homogenous group, but rather, were made up of different Romani populations who came to Russia from various countries and at various times.Footnote 6 The Roma most closely associated with tsyganshchina were primarily part of Russia's Romani elite made up of the Russka (or Khaladytka) Rom who migrated to Russia from Germany and Poland from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries and eventually settled in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Many spoke Russian fluently, led the sought-after “Gypsy” entertainment, and took pride in their “ostensible cultural difference” from Roma less integrated into Russian society.Footnote 7

Although the music of Roma in Russia included itinerant and camp songs (polevye and tabornye pesni) as well as all-choral “Road House” music, it was the “Gypsy romance” (tsyganskii romans) that would inform and become emblematic of tsyganshchina and that would later make up a significant part of the repertoire in émigré cabarets.Footnote 8 While the origin of the Russian Gypsy romance is imprecise at best (with a complex history of mutual borrowing between Russian urban, folk, and Romani idioms to illustrate what Carol Silverman has called “coterritorial musical traffic”), as is the origin of collaboration between Romani and Russian musicians and poets with regard to this genre, by the mid-nineteenth century, a recognized repertoire of “Gypsy” romances could be found in Russian songbooks, in the salons of the nobility, and at the lively shows of Romani choirs in urban restaurants.Footnote 9 It is this repertoire, which includes such standards as “Dve gitary” (Two guitars) and “Ochi chernye” (Dark eyes), that served as a significant means among the émigrés of upholding and recreating prerevolutionary Russian culture and that would predominate in Russian restaurants throughout the diaspora.

The complex positioning of the “Russian Gypsy” genre was only heightened within the diasporic context, however, with both Romani and non-Romani musicians—all recent exiles who had fled Bolshevik Russia—now performing an amalgamated Otherness for the dollar-paying New York public. This essay examines the cultural and musical trope of the “Russian Gypsy” as it was performed on the stages of New York and the cultural entanglements at work in these enactments. I begin with an overview of the Russian nightclub scene in 1920s New York before examining the conceptualization (including interior and musical entertainment) of the Club Petroushka in particular. I then delve into the specific visual and musical characteristics of Russian Gypsy performance at the Club Petroushka, integrating into my analysis contemporary newspaper accounts to gauge the music's reception and dominant discourses surrounding Russian Gypsy music. At the essay's center lies a close analysis of extant recordings of Russian Gypsy music by artists affiliated with Club Petroushka. This analysis reveals a common performance practice, with two traits in particular that I argue were vital in creating a transformative experience for listeners as echoed in contemporary accounts: heightened emotionality and a rhythmic timelessness—a quality I call achronality. Finally, I examine the performative aspect of the Russian Gypsy trope as it was enacted at Club Petroushka, looking specifically at questions of cultural cooptation and appropriation within the Russian Gypsy music genre in situ and as a whole.

Ultimately, this essay illuminates the multivalent function of Russian Gypsy music for the different constituencies comprising Club Petroushka—from the exotic sounds that ushered in a dreamland for patrons to a marketable, self-aware trope for its recently exiled performers—illustrating what historian Burton Peretti has described as the delicate balance between meticulous calculations of Prohibition-era club owners (a “somewhat rationalized business”) and the patrons’ desire to be whisked away into a world of rebelliousness, a dynamic only further complicated by the dominant ethos of nostalgia underlying first wave émigré cultural production as a whole.Footnote 10 Exploring this balance as it materialized at the Club Petroushka, this essay documents a vibrant yet little examined topic within New York nightlife and within the emergent field of Russian émigré music studies: namely, Russian émigré musical entertainment within Gotham's Roaring Twenties.

New York's Russian Nightclubs

When Basil Fomeen began his studies as a young cadet in Kharkov, Russia (now Ukraine), little did he know that he would soon be living in New York City, working sundry jobs very different from the officer's position indicated by his schooling. And yet, fate dealt Fomeen a different hand. In 1917, Russia became enmeshed in revolution, and Fomeen was forced to escape, cutting off his epaulets (“the dreams of youngsters”) and dodging Bolshevik supporters.Footnote 11 Making his way to Belgorod to join the anti-Bolshevik White Army, Fomeen eventually evacuated Russia for Gallipoli, Turkey, where tens of thousands of members of the White Army lived in camps and aspired toward the never-realized goal of ultimately defeating the Bolshevik government.Footnote 12 Fomeen soon left Turkey for Greece, where he got a taste of playing music in restaurants before making his way to New York City onboard the SS Constantinople. Upon his arrival in December 1922, Fomeen found his way to the prominent St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral in the Upper East Side, where he was given two dollars and instructed to go to the Russian Immigration Society in Harlem, which was then receiving the newly arrived refugees from war-torn Russia.

It was in Harlem that Fomeen discovered a burgeoning enclave of fellow exiles. Refugees from the recent revolution and civil war, the émigrés quickly established a vibrant community of approximately three thousand people around Mount Morris (now Marcus Garvey) Park, complete with Russian shops, restaurants, and a church.Footnote 13 Like Fomeen, many of the men had fought in the White Army and had made their way through Gallipoli or Constantinople to the United States. Among the group were also numerous musicians ranging from singers of Russian folk music to classically trained artists eager to continue making music in their new domicile, New York City.

Hoping to leave the free lodging initially offered by Russian Immigration Society for his own living quarters, Fomeen accepted any work he was offered. Among Fomeen's first jobs in New York were bouncer at a speakeasy, an elevator operator at the Times Square building, and a musician at a Greek restaurant.Footnote 14 After a short series of odds and ends jobs, Fomeen was invited to join a Russian Gypsy choir then being formed by the émigré singer, Anna Shishkina (dates unknown), most likely a descendent of the renowned family of Romani musicians from Moscow and St. Petersburg.Footnote 15 Reflecting the important role played by social networks within diasporas, the non-Romani Fomeen found this job through his émigré connections—in this case, a cellist with whom he had performed while in Greece and who was a close friend of Shishkina's.Footnote 16 Further attesting to the émigré alliance at work, Shishkina—or “Annushka,” as Fomeen affectionately called her—immediately took Fomeen under her wing and invited him to stay temporarily at her apartment (which she shared with fellow émigré singer Inna Miraeva).

One of numerous Russian Gypsy choirs established by the recent exiles and cropping up throughout Manhattan, Shishkina's ensemble was part of the soon to open Club Petroushka, a high-class nightclub in Midtown conceived and designed by the modernist Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) artist and now émigré, Nikolai Remisoff (1884–1975).Footnote 17 Indeed, Gypsy choirs were a staple of the Russian restaurants then proliferating in New York City, a trend instigated by the newly arrived émigrés. Reflecting the public's interest in Russian nightclubs, the Club Peroushka immediately reaped success—the ripple effects of which were no less felt by the club's musicians, as they received steady salaries; frequently went home with cans of caviar; and, unashamedly defying the law imposed by the Eighteenth Amendment, regularly sent glasses of vodka to the club's head chef in exchange for appetizers during shows.

Here a word of clarification is in order, for the story of the Russian restaurant in Gotham is by no means limited to Club Petroushka. For one thing, restaurants run primarily by and for immigrants from the Russian Empire had existed in New York since the large migration of Russian Jews between the early 1880s and the eruption of the First World War.Footnote 18 With the arrival of the post–Bolshevik Revolution émigrés in the early 1920s, these quaint places continued to proliferate (primarily in the East Village and Harlem). Unlike their upscale Midtown counterparts (e.g., Club Petroushka), the establishments catering to émigrés themselves typically lacked plush amenities and overt displays of an exotic Other, functioning instead as local gathering spots.Footnote 19 The restaurant, Sibir [Siberia] (257 E. 10th Street), for example, doubled as a community center, providing recent émigrés with a site to locate one another. An advertisement for the restaurant from July 1923, for example, states, “For those Russians recently arrived from Constantinople! Are you seeking your fellow émigrés, yet do not know their address? You can meet them each day at the restaurant.”Footnote 20 The restaurant also offered to receive letters from the new arrivals. In addition to delineating such practical functions, advertisements for these restaurants tended to stress their affordability, authenticity of cuisine, and homely atmosphere, a quality signaled by such words as “uiut,” which has no direct translation into English, but which approximates the idea of comfort, coziness, and something familiar. The insider knowledge on which many of these restaurants operated is reflected further in their folksy names—“Russkaia Izbushka” (Russian hut) and “Russkii Ugolok” (The little Russian corner)—and slogans, including “zdes’ rus'iu pakhnet,” part of the saying commonly included in Russian fairy tales that literally translates into “it smells of Rus’ here” or “the Russian spirit is here,” as well as the predominant placement of their advertisements in New York's Russian language newspapers.Footnote 21

Although this kind of modest restaurant had a place in the lives of the recent émigrés, New York's more widely-recognized Russian establishments were those geared toward the US public and that operated on an overt and self-conscious presentation of a mythologized Imperial Russia. Concentrated in Midtown Manhattan, these clubs included the Troika (117 W. 48th Street), which featured a “Gypsy” ensemble with the ethnically Russian, émigré singer Inna Miraeva at the helm. Advertised in the New York Times with the slogan, “A bit of Old Moscow in the Heart of Broadway,” the club also included an all-female dance orchestra as well as other forms of “unique Russian entertainment.”Footnote 22 Another popular restaurant was the Russian Eagle (36 E. 57th Street), whose fame as an establishment unsuccessfully raided by Prohibition agents in April 1923 was only surpassed by its notoriety as an elite enterprise (“a fashionable restaurant patronized by persons prominent in society”).Footnote 23 Of the Russian Eagle's major selling points were its owner (General Feodor Ladizensky, a former commander of the Tsar's army), the colorful Russian costumes, and the alleged aristocratic ancestry of its wait staff (“men and women of noble birth, impoverished since Bolshevism took the reins in their native country”).Footnote 24

As these descriptions suggest, the advertisements for Midtown's Russian restaurants in the 1920s tend to highlight an exotic and exclusive appeal as well as a connection to a bygone, tsarist Russia. Advertisements for Kazbek (7th Avenue and 49th Street) in the New Yorker, for example, feature the silhouette of a sword dancer, flanked on one side by what appears to be an elongated hookah and a curvaceous teapot on the other (Figure 1). Below the image read the words: “Russian Arabic room, one of the smartest places in town frequented by the elite who know. Cuisine royale prepared by Mr. S. Ignatoff, chef to the late Czar of Russia . . .”Footnote 25 Collapsing conventional Middle Eastern signifiers (hookah, “Arabic” room) with those of prerevolutionary Russia (in this case, consumption of tsarist Russia), the advertisement operates on selling an exclusive object swathed in Orientalist imagery. It is possible, of course, that the advertiser's reference to an “Arabic room” was an attempt to transform the club's less familiar Caucasian character (Mount Kazbek; dagger dancing) into something more recognizable to contemporary New Yorkers. Regardless, the hodgepodge of signifiers—from the Tsar's chef to the “tsyganne jazz” entertainment sandwiched between “Martynoff the dagger dancer” and the Apache Tango—demonstrates a deliberate synthesis of exotic tropes all within the framework of an elite, Russian restaurant.Footnote 26

Figure 1. Advertisement for the Kazbek Restaurant, New Yorker, December 26, 1925.

In part, the interest in Russian restaurants can be explained by the Russian vogue then taking New York by storm. Instigated by Nikita Balieff's Chauve-Souris revue that came to Broadway in February 1922 and by the newly established presence of the exiles more broadly, the style russe trend rapidly manifest itself in such spheres of cultural production as nightclubs, sheet music, society balls, and fashion.Footnote 27 Describing the wild success of the style russe within the nightclub circuit in particular, Basil Fomeen wrote, “This was really the time [ca. 1923] when the Russian influence was at its height in New York. Besides the ‘Petrushka’ [sic] there was ‘The Russian Eagle’ opened by General Lodijensky. . . . They were competitors but we were both doing a terrific business.”Footnote 28 Echoing Fomeen's assertion, a short article from October 1923 in the Russian language daily Novoe Russkoe Slovo likewise notes the trend, deploying prototypical Russian symbology in its description: “Russian restaurants in New York are multiplying like mushrooms after a rain storm.”Footnote 29 Less than two years later, the very first issue of the New Yorker (February 21, 1925) featured an advertisement for “The Russian Inn” (touting the requisite Russian cuisine and “Gypsy” chorus) followed by advertisements for numerous Midtown Russian spots in subsequent issues. And, as late as 1927, Stephen Graham attested to the continued interest in Russian haunts, stating that, “The Russians have the most enchanting foreign resorts in New York.”Footnote 30

To limit the trend of nightclubs a la russe to the 1920s Russian vogue, however, would be to overlook their place within the carousing impulse then defining New York's nightlife. Larry Fay's notorious El Fey, the lively parties hosted by Texas Guinan (who regularly invited Basil Fomeen and other Russian émigrés to perform at her shows at the Beaux Arts Café), and the seductively chilled air at the Club Mirador lured thrill-seeking socialites into all-night affairs of hedonist leisure.Footnote 31 The clubs in Midtown Manhattan in particular became emblematic of the spirited scene. As Burton Peretti writes, “[Midtown's] boisterous rooms filled with illegal liquor, female dancers, well-heeled revelers, and multiethnic employees, surrounded by a nightlife environment of speakeasies, Broadway street life, taxicabs, dance halls, and all-night restaurants, exerted a pull on the national imagination.”Footnote 32

Beyond the hedonistic streak driving “well-heeled revelers” to nightclubs, the clubs also offered an especially liberating social experience for certain segments of the New York public. Young society women in particular valued these newfound sites of freedom. Ardently defended by Ellin Mackay, prominent New York heiress and soon-to-be wife of Irving Berlin, for example, Manhattan's nightclubs presented an alternative to staid society parties and the pedantic, self-satisfied bores (“extremely unalluring specimens”) found therein.Footnote 33 Most importantly, nightclubs gave women like Mackay a sense of agency: “At last, tired of fruitless struggles to remember half familiar faces, tired of vainly trying to avoid unwelcome dances, tired of crowds, we go to a cabaret. . . . We go with people whom we find attractive. . . . We go because, like our Elders, we are fastidious.”Footnote 34 Whether with regard to their progressive gender mores or their novel attractions, Prohibition-era nightclubs presented New York with something new and exciting.

A “Fantastical” Vision: Midtown's Club Petroushka

It was in the midst of this booming environment that Nikolai Remisoff created the Club Petroushka. Having come to New York in 1922 as one of the primary stage designers for Balieff's Chauve-Souris, Remisoff soon undertook his own style russe project. Responding to an alleged absence in Gotham of any club with “individuality or character distinct from all others,” Remisoff envisioned a club that would be decorated “fantastically, whimsically” and in which “the wearied and worried might be seduced into forgetfulness of the day's turmoil.”Footnote 35 With this idea in mind, Remisoff opened the Russian-themed club on 50 East 50th Street in October 1923.

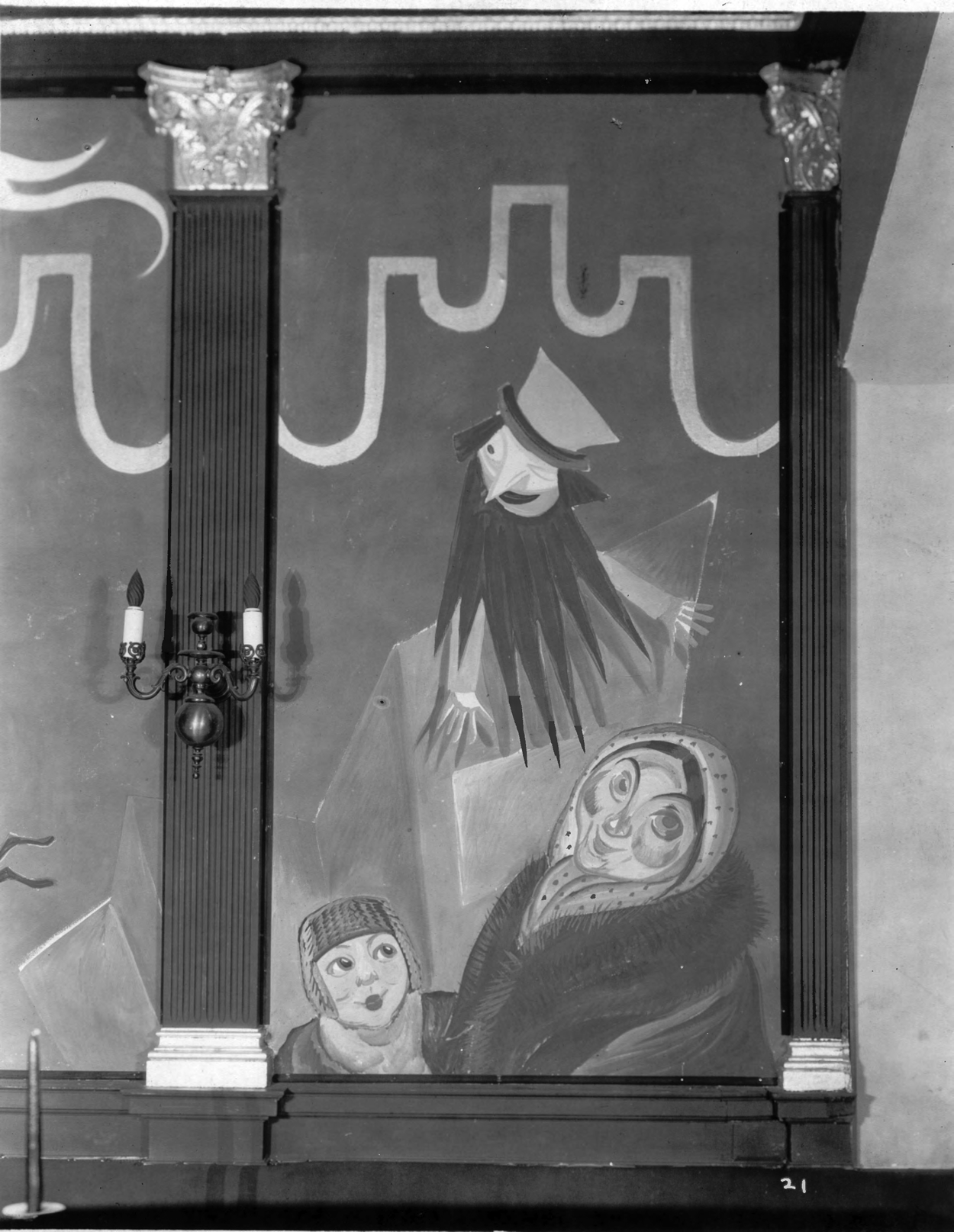

Upon checking one's coat and ascending the stairs to the main dining room, one was greeted with a mélange of vibrant murals. Echoing Remisoff's stage designs for the Chauve-Souris, the paintings featured fantastic figures, grotesque in their style and stature. Directly across the entrance stood an impish Petrushka—the Russian folk puppet after which the restaurant was named—whose mischievous smile and squinting eyes suggest those of a rascally, if not unsettling, host (Figure 2). Another wall featured a doting mother and angular father in furs and wraps with their apple-cheeked son at their side (Figure 3). The majority of the wall space was devoted to the gargantuan merchants and coachmen heartily enjoying themselves at a traktir (tavern). While some of the men eagerly consume food and drink, others, enlivened by their stay, dance with gusto (Figure 4).

Figure 2. Petrushka mural from the Club Petroushka. Box 16, Folder 3, Nicolas Remisoff papers, Collection no. 0199, Special Collections, University of Southern California Libraries.

Figure 3. Mural of a family from the Club Petroushka. Box 16, Folder 3, Nicolas Remisoff papers, Collection no. 0199, Special Collections, University of Southern California Libraries.

Figure 4. Dancing coachmen mural from the Club Petroushka. Box 16, Folder 3, Nicolas Remisoff papers, Collection no. 0199, Special Collections, University of Southern California Libraries.

Remisoff's wit permeated nearly every inch of the club. Peeping around a corner of a coachmen's table was the emblematic figure of Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837), casting a knowing glance onto the club's patrons. Another mural featured a sign in Russian strictly prohibiting the sale of alcohol and hanging next to an inebriated coachman enjoying a stack of bliny and vodka. And a publicity shot featured Remisoff himself in a glaring standoff with one of his figures (Figure 5). With their hovering presence practically enveloping the club's patrons, the murals served a metonymic function, as guests imbibed alongside the painted representations of Russian indulgence and festivity.

Figure 5. Nikolai Remisoff facing off with one of his coachmen. Box 16, Folder 3, Nicolas Remisoff papers, Collection no. 0199, Special Collections, University of Southern California Libraries.

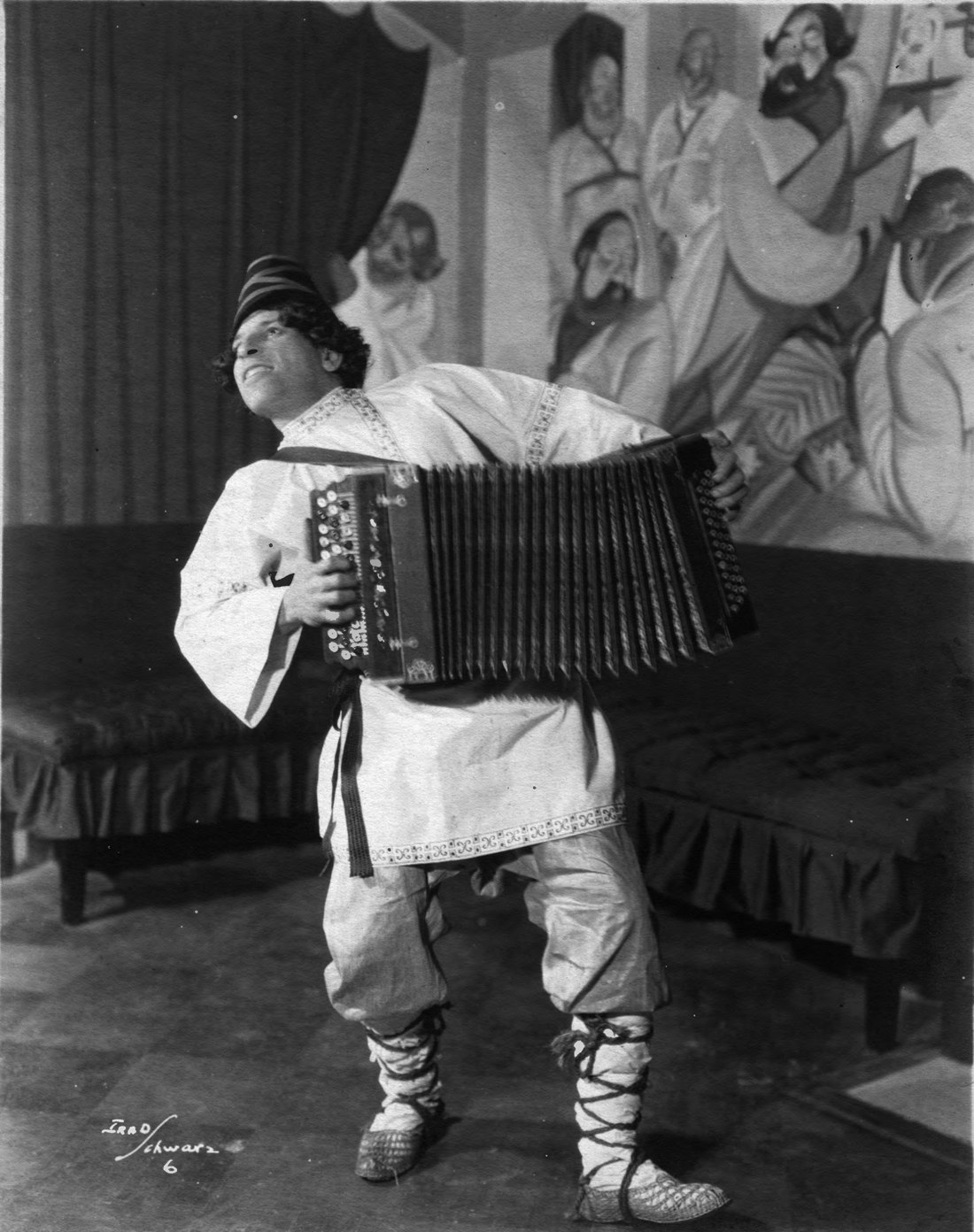

Remisoff extended the stylized approach of the club's decoration to its musical entertainment. The club was to have “Russian folk songs” as well as “gypsy music,” and boasted a balalaika orchestra (with Alex Kiriloff as its conductor) and a “Gypsy” orchestra (led by Harry Horlick, who soon after the club's closing started the renowned A+P Gypsies ensemble).Footnote 36 Musicians on the dining room floor wore folk costumes, birch bark shoes, and uniform hats (kokoshnik-like headdresses for the women and conical hats with curls emerging from their edges for the men) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Members of Club Petroushka's folk choir: Basil Fomeen (accordion), Natasha Meleshev, and Alexandre Meleshev. Basil Fomeen Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress.

Careful attention was likewise given to the instruments featured by the musicians. When listening to the folk choir rehearse for the club's opening night, for example, Remisoff determined that it would be better to present the group with an accordionist rather than simply a cappella. Here, too, Remisoff had a specific idea behind his “fantastica[l]” vision.Footnote 37 Instead of a keyboard accordion, Remisoff insisted on a button rendition (an instrument resembling the Russian folk bayan) (Figure 7), a fact unhappily discovered by Fomeen after purchasing a keyboarded instrument for the gig. Whether in displaying the button accordion, birch-bark lapti, or murals of gregarious coachmen dancing a la russe, Remisoff's meticulous planning suggests the crafting of a deliberate product intended to provide guests with the exotic experience then sought by New York's nightclub patrons.

Figure 7. Club Petroushka button accordion player (unidentified). Box 16, Folder 3, Nicolas Remisoff papers, Collection no. 0199, Special Collections, University of Southern California Libraries.

Russian Gypsy Music at the Club Petroushka

Of all the exotic amenities at Club Petroushka, the club's most distinctive feature was the so-called “Gypsy Room” and its associated choir. Located on the third floor of the building, the Gypsy Room required an additional five-dollar fee to enter. Upon walking into the room, all senses were stimulated: on the walls hung beautiful tapestries, silk cloths, and carpets; the scent of Turkish coffee (the only provision served in the space) permeated the air; and in one corner stood a wagon from which silk-costumed choir members emerged to serenade guests.Footnote 38

Perhaps the most prominent sensation upon entering the Gypsy Room was the sound of the choir, which quickly became a high point for visitors and, according to Fomeen, “the talk of the town.”Footnote 39 Critical to the choir's popularity was the perceived authenticity of the ensemble and its music. A newspaper write-up from 1923, for example, describes the ensemble in the following way:

A troupe of Russian Gipsys [sic] from the Great Steppes made their American debut [at the Club Petroushka]. The ensemble singing of these sixteen men and women, their weird chants, their passionate songs and dances, accompanied as they are on the almost obsolete seven-stringed Russian guitar, gives the seeker after unique things something to go home and talk about. From their “Tabor” (a Tzigane camp as realistic as if it had been brought over bodily from its native environment) these strange people descend the stairs to the “Tracktier” singing melodies of exquisite beauty vibrating with that indefinable spirit of Russia.Footnote 40

Deploying such signifiers as the seven stringed guitar (whose value is enhanced by its positioning as an antiquated instrument), a simulacra Tabor, the ensemble's alleged origin in the Steppe as well as the surmised Romani background of its singers, and the nebulous Russian “spirit,” the article simultaneously authenticates the choir while collapsing “Gypsy” and “Russian” into a singular, exotic trope. Utilizing the words “weird” and “strange,” moreover, only furthers the Othering underlying the review and, as David Garcia notes in his analysis of the reception of late 1940s Afro-Caribbean recordings, increases the perceived distance between the reader/listener and the exotic Others embodied by the music in question.Footnote 41 The performance of Russian Gypsy within the context of the New York nightclub, then, signals a double Orientalism at play, with the presentation of an imagined “Gypsy” culture by predominantly non-Romani actors followed by the integration of Russian and Gypsy into a single cultural Other for and by New York spectators. Like other Orientalist practices, the performance of Gypsy music at Club Petroushka thus engages with what Derek Scott describes as an impulse to “represent” rather than to “imitate,” a process that rests on “culturally learned recognition” of these various Others as they are construed in the Western imagination.Footnote 42

While there is no doubt that the vision of silk-clad “Gipsys” descending from their Tabor contributed to this powerful effect, it was the sonic execution of this Otherness that completed this “recognition.” This recognition, in part, rested on the music's formal characteristics—including, commonly, the minor key, a reliance on diminished seventh harmonies, and a call and response between soloist and choir or accompanying ensemble—that tend to predominate in the Russian Gypsy repertoire. Yet the most notable element in defining the Russian Gypsy genre as it has been described in sources ranging from Nikolai L'vov and Ivan Prach's influential 1806 collection of Russian folk songs to accounts detailing Russian Gypsy music in New York newspapers from the 1920s has been its distinct performance practice.Footnote 43

Before looking at such accounts in detail, I turn to a brief description of the Russian Gypsy music performance practice and its execution by New York's émigré artists. A practice established in Russia at least since the early nineteenth century, Russian Gypsy romances tend to begin slowly, employing significant amounts of rubato and frequent pauses. The melody is usually executed by a soloist (whether instrumental or vocal), whose expressive calls are responded to by flourishes of fast arpeggios and seemingly improvised runs by instruments or by the wide harmonies of a choir. After an extended back and forth between soloist and accompanying instruments or voices, the songs accelerate to a grand climax. Sudden changes in tempo contribute to the songs’ dramatic effect, and the common inclusion of vocables only furthers the sense of heightened emotion central to creating the genre's defining aesthetic of impassioned abandon and toska, or the longing for someone or something gone or far away.Footnote 44

As an established practice, the specific manner of performing Russian Gypsy romances was carried on by artists in the diaspora, including those artists associated with Club Petroushka. While recordings of Club Petroushka's Gypsy choir have not survived, one can get an idea of the style in which the choir performed based on descriptions in newspapers of the choir's performances, recordings of Russian Gypsy songs made by the choir's members and by ensembles from other Russian restaurants of the time, and recordings of Russian Gypsy music composed by its choir members.Footnote 45 Many of these musical traits, for example, can be heard on a 1927 Columbia recording of the standard “Ochi chernye” made by Anna Shishkina, lead singer and head of Petroushka's Gypsy choir. The piece begins with a string ensemble (the “Gypsy Orchestra”) playing the first two notes of the piece with a loud upward gesture, pausing expectantly on each note. This dramatic opening gives way to a thudding down beat that becomes the first pulse of a regular three-beat waltz. As soon as a sense of time is established, the ensemble pauses mid-phrase only to complete the opening phrase just as abruptly with the pounding waltz. The second phrase shifts in texture to an intimate back and forth between Shishkina and a seven-string guitar, another hallmark of the genre. Shishkina's husky alto voice opens each phrase, which is smoothly completed by the guitar's spiraling apreggios. Moments of rubato dot every turn of Shishkina's execution, as she inserts vibrato-filled pauses throughout the text and teasingly comes back to the main melody with the requisite “da-ri-dai” vocables.

The lyrics of Shishkina's “Ochi chernye” (Dark Eyes) further the impassioned effect. Shishkina sings intensely of “dark eyes” that are at once “passionate,” “burning,” and “beautiful.” These eyes fill the narrator with “love” and “fear,” appearing in her dreams to give her hope only dashed by her awaking alone in darkness (“But I wake up, the night is dark around me, No one is here to pity me”). On the words “pity me,” Shishkina adds an extended rubato, sliding down the end of each word with a wailing glissando. In a spirited final verse not found in the original nineteenth-century composition, Shishkina throws in a plug for Gypsy music and for alcoholic imbibement, as she sings, “Live, we cannot, without our champagne and without our Gypsy singing,” executing the word “champagne” with a seductive roll and emphatically elongating the word “Gypsy.”Footnote 46 Once Shishkina utters her last phrase, the ensemble closes the piece, racing to the last cadence at a frenzied pace.

As the lyrics of these songs would have held little meaning to the majority of Club Petroushka's patrons, the sonic dimension, and performance practice in particular, was critical in conveying the Russian Gypsy idiom to its New York public. It is not surprising, then, that the musical conventions executed by Shishkina and other singers were upheld in purely instrumental versions of the Russian Gypsy repertoire. The 1923 recording of “Ochi chernye” made by the Russian Eagle Orchestra, Club Petroushka's close rival, mirrors many of the effects found in Shishkina's later recording. Opening similarly with a pause on the song's first two notes, the string ensemble plunges into a fast-paced waltz, whose downbeats are punctuated by the percussive sounds of a piano. Similar to Shishkina's rendition, the song is replete with dramatic pauses and rubati. Instead of a woman's voice in the solo role, however, the Russian Eagle Orchestra presents the opening call with a violin. The violin's expressive pleas are answered by the piano with seemingly improvised chords, downward scalar gestures, and upward arpeggios. Throughout the song's chorus, the soloists continue to riff on the melody with each repeating phrase including a greater number of instruments. With tighter ensemble work than that presented by Shishkina's recording, The Russian Eagle Orchestra closes its version of “Ochi chernye” with a prominent accelerando marked by a dramatic last pause before completing its final phrase.

On occasion, the émigrés themselves composed Russian Gypsy romances, which typically aligned in content and execution with the established tradition. Fomeen, for example, wrote thirty-six “Russian Gypsy Songs,” eight of which were recorded in 1942 for Decca Records by his close friend and fellow émigré, Adia Kuznetzoff (1889–1954). Kuznetzoff's delivery of the songs closely follows the conventions of the Russian Gypsy romance, as exemplified by his performance of “Ekh, rodnye!” (Oh, my dear ones!). Opening with a violin supported by piano and guitar, the song's introduction reaches a dramatic pause before giving way to a sudden cadence, a gesture later executed by Kuznetzoff that becomes the climactic motive of the piece. Kuznetzoff then enters, singing with his rich bass, “There is no need for tears, tears will not help you, for in tears you will not drown out your aching longing [toska].” Each subphrase is dovetailed with an elaborate arpeggio on the guitar, creating an impassioned call and response that reinforces the affective character of the text. The absence of a regular meter in the verses as well as frequent rubati contributes further to this emotive feel. The listener is suddenly thrust out of this rhythmic limbo with the regular beat introduced in the chorus section, which begins with the words, “Oh my dear ones, sing to me a song and let me forget my sorrow” (which is translated in the sheet music into English as “Gypsy, gypsy, sing a song for me”). The violin spirals in and out of Kuznetzoff's lines as a steady accelerando leads to the high point of the song. At this moment, Kuznetzoff sings, “May all my troubles pass before me as in a dream; I want to live, and love without stopping,” at the top of his range and employs dramatic pauses, vibrato, and glissandi. Kuznetzoff then repeats the phrase, but this time, starts out with vocables (“dai-dai-dai-dai”), which further adds an affective dimension to the work and marks the last words of the song (“I want to live . . .”) with heartfelt poignancy.

Like other examples of Romani music traditions, the performance practice exhibited by Kuznetzoff, Shishkina, and others rests on what Carol Silverman has called the “performance of emotion,” the musical specifics of which I address in the following section.Footnote 47 Far from necessarily constituting innate expression, this performance can stand as a deliberate strategy, presenting a “saleable commodit[y]” that operates on the entrenched connection between “emotion” and “Gypsy ethnicity.”Footnote 48 As Silverman notes, music itself serves as a primary medium for conveying affect within this nexus, with the performance style in particular (including “cries,” “yelps,” and “wails”) signaling the requisite emotions.Footnote 49 Thus, the long-established correlation between emotion and “Gypsiness” and the role of music in giving voice to and facilitating this dynamic points to the centrality of music as a site for the public presentation, circulation, and selling of affect on which would rest the success of Russian Gypsy performance in Manhattan's nightclubs.

Club Petroushka as “Dreamland”

The distinctive performance practice as executed by émigré artists in New York and associated with Russian Gypsy music as a whole was not lost on Club Petroushka's patrons. Take, for example, the following newspaper description of a performance by the Club's choir:

The tempo quickens and by the time [the choir members] reach their platform at the head of the room, their song changes into a wild passionate air, which in its finale reaches a triumph of indescribable beauty and expression.

These songs of the Tziganes are of a rhapsodical strain highly expressive of various moods. They have a distinct rhythm without bar measure or symmetry of musical phrases and are striking in their defiance of form known to the musicians of the Western World.Footnote 50

Two overarching elements found in this description serve as the basis for Russian Gypsy music performance at the Club Petroushka and elucidate how this music operated in creating a “dreamland” for New York's nightclub patrons: heightened emotionality and a deliberate play with a sense of time.

The emotive nature long associated with Russian Gypsy music and referenced in the above passage is signaled through such musical conventions as expressive vibrato, emphatic slides in pitch, husky vocal timbres, and capricious melodic runs. These qualities helped create the semblance of “wild passionate air[s]” and “rhapsodical strain[s] highly expressive of various moods” described in the review. Like other musical practices correlated with heightened emotional states, Russian Gypsy music aligns with what Eckehard Pistrick (following Denise Gill-Gürtan) calls “cultivated emotionality,” in which certain emotional states can be “embedded in ideologies of music-making and listening.”Footnote 51 In the case of Russian Gypsy music, this “cultivated emotionality” can refer to the specific mood of longing (toska) for insiders or to a more general expressivity for less indoctrinated listeners. In each case, the prescribed response indexes deep emotion that surpasses the linguistic sphere (for example, reaching a climax of “indescribable beauty” as stated in the review).

Furthering a transformative experience for listeners is the playing with time (achronality) ubiquitous to the performance of Russian Gypsy music and noted also in the review. The frequent and unexpected changes in tempo, weighty rubati, and dizzying accelerandi typical of the repertoire create a kind of sonic-temporal disorientation, offering music of “distinct rhythm without bar measure or symmetry” that is “striking in [its] defiance of form.” The shifts in rhythm found in Russian Gypsy music mirror a cultural association of timelessness with Gypsies as a whole as they are often presented in Western literature. In her work on Roma in Russia as well as in the Russian imagination, Alaina Lemon describes this association in literature as the proclivity of the literary trope of the Gypsy to “trigger narrative time to switch its flow from normal history into a suspended, vertiginously timeless present that melts with the past.”Footnote 52 Simultaneously here and there, now and then, the Gypsy as imagined in Western literature and projected onto Russian Gypsy music is rooted in an expectation of transcending conventions of time and space. Indeed, casting non-Western Others into a non-linear time frame has presented a common means for the construction of difference among Western actors (whether scholars, activists, or the general public).Footnote 53

The temporal disorientation precipitated through Russian Gypsy music as it was perceived in New York's nightclubs simultaneously engages a broader achronality generated by the nocturnal setting of its performance. As Bryan Palmer writes in his study of night cultures: “Nighttime—its clock is different. . . . This is a matter not simply of hours and minutes . . . but of the tyrannies of time defied, if not displaced.”Footnote 54 Palmer connects these “tyrannies of time” to the teleological pragmatism imposed by capitalism and presents night spaces as alternative sites that can liberate participants from the “drudgeries of day.”Footnote 55 In this way, night spaces operate by transcending normative modes of time and space to present sites primed for “ambiguity and transgression” and “acts of rebellious alternative.”Footnote 56

The temporal slippage characteristic of night spaces as a whole can be found in contemporary descriptions of the Prohibition-era nightclub. In his 1927 essay, Stephen Graham emphasizes this play with time in constructing wholly new realms: “[Inside the nightclub] [t]ime and money and news have slipped away, and their urgencies become forgotten. . . . New York is not America, but it is New York. New York night life is not even New York. It is a hidden chamber in the kingdom of the heart. Draw the blinds! Light the lamps!”Footnote 57 Graham's “hidden chamber” mirrors Palmer's liberating possibilities of the self's “realization in acts of rebellion,” thus pointing to the role of Gotham's nightclubs in enabling experiences far from the quotidian and mundane. “Gypsy” music in particular was positioned as an effective entry point to this “hidden chamber.” In describing his experience hearing Hungarian Gypsy music at a nightclub, Graham writes: “the dulcimers are sounding, the people are singing, yes, even the gipsies who have stepped out of the pictures on the walls are singing the choruses outside their tents. It is two in the morning. It is Hungary. Brazen New York has dissolved in a cocktail. The unreal has become the real . . .”Footnote 58

Contemporary descriptions of Russian Gypsy performances similarly position the Gypsy repertoire, and its performance style in particular, as triggering a transformative experience for listeners. A 1930 New York Times review of a concert of Russian Gypsy music performed by émigré and Romani singer Nastia Poliakova (1877–1947) at the Bijou Theatre articulates the potential of Poliakova's music in bringing the “listener on foreign shores” to a Russia defined by the “post-war period of gayety and song and romance.”Footnote 59 Citing the songs’ “sentiment, their picturesque melancholy, their semi-Oriental lamentation or sudden wild gayety” as well as Poliakova's distinct execution of the music, the review echoes other writings in its emphasis on the performance practice of the Russian Gypsy repertoire for eliciting a powerful effect on listeners. Indeed, Poliakova's review similarly underscores the particular execution of the music as the defining and enlivening feature of the genre: “Some of the songs, known through collections, do not strike the music lover who reads them at the piano. It is when the melody is intoned in a way that has not to do with conventional methods of singing or style that the same song which looked uneventful on paper comes to life and takes on intense human meanings” (italics added).Footnote 60 Oliver Saylor's 1922 program for the Chauve-Souris features a much earlier description of Russian Gypsy music, which likely could have set the tone for the genre's reception in New York. In this work, Saylor emphasizes the “wild” association with Russian Gypsy music, juxtaposing the genre against the more genteel and self-possessed traditions of Russian romances and ballet while simultaneously subsuming “Gypsy” music under a broader umbrella of Russian culture: “[The production's] purely Russian numbers run the range from the quaintly sentimental ballades of Glinka and the aristocratic restrain of the Ballets Russes to the wild Romany abandon of gypsy melodies . . .”Footnote 61

Hence, by the time Charlie Chaplin, the Gershwin brothers, and others became spectators of the exotics displayed at Club Petroushka, the correlation between Russian Gypsy music and a “wild Romany abandon” had been clearly established in public discourse. Indeed, the entire enterprise of Club Petroushka rested on a suspension of reality ushered through the club's decor and entertainment. Experiencing the club's vibrant murals, folk-clad musicians, and, above all, the Russian Gypsy music, with its temporal malleability and enhanced emotionality, within a space primed for an encounter with the “unreal” allowed patrons to enter a wholly different realm of an imagined, bygone Russia, complete with dancing coachmen, cheerful peasants, and singing “Tziganes,” straight from the Russian steppe.

Club Petroushka as Performance

Central to the ideas of Palmer and Graham in explaining the efficacy of night spaces is the seeming aversion to the pragmatic, utilitarian impulse driving the capitalist sphere, the rejection of which opens up possibilities for alternative and potentially transgressive modes of being. Although helpful in understanding the appeal Club Petroushka held for its patrons, this model of night cultures overlooks the deliberately crafted and self-aware side of the nightclub. Like other cabarets founded by émigrés following the Bolshevik Revolution, Club Petroushka rested on a carefully managed presentation of Otherness framed by a mythologized, prerevolutionary Russia. Regarding the appeal this staged Otherness held for Western audiences, Mark Konecny writes: “Russia exported its unique brand of cabaret to Europe and America, where romanticized notions of the country's past were popular. Cabaret directors welcomed eager crowds who sought a glimpse of a land they believed to be far more exotic than their own. . . . Russian Cabarets in exile played to the stereotypes that Americans and Europeans held about Russia . . . Balalaikas, nesting dolls, dancing gypsies and joyful peasants could be found in abundance in every Russian establishment.”Footnote 62 It was this deliberate presentation of an exoticized Russia around which the Club Petroushka was conceived. With its gargantuan merchants, impeccably-clad peasants playing button accordions, and meandering “Gypsies” holding the seven-stringed guitar, every corner of the club resonated with an air of self-aware intent.

The deliberate presentation of “Gypsy” by the majority non-Romani choir in particular contributed to the performative undercurrent of Club Petroushka's operation. Some members of the choir traveled to work in their silk garments, a point that caught the attention of onlookers along the streets of Manhattan.Footnote 63 Others noted the artificial nature of their undertaking. In his autobiography, for example, Fomeen includes a photograph of himself alongside Anna Shishkina and other members of the club's Gypsy choir adorned with colorful scarves, shirts, and necklaces. The formal presentation of the choir, however, is complicated by the remark typed by Fomeen next to the photograph: “Anna Shishkina the GYPSY and some of the ‘gypsies’” (Figure 8).Footnote 64 Fomeen's use of all caps in designating Shishkina's ethnic legitimacy amplifies the self-awareness signaled by the use of quotes around the word “gypsies” in reference to himself and the other non-Romani members of the choir, and it further underscores the performative nature of the act itself.

Figure 8. Anna Shishkina, Basil Fomeen, and other members of Club Petroushka's Gypsy choir, with typed caption. Basil Fomeen Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress.

Fomeen's typed note echoes a long-standing dualism in Russian culture of simultaneously subsuming and opposing the Gypsy Other to the Russian Self.Footnote 65 Driven by Russian national ideology, this dualist tendency helped define musical practices in Russia that were then carried on in the diaspora. For one, Russian Gypsy music became increasingly executed by non-Romani practitioners over the course of the nineteenth century, a trend reflective of the same “orientalist fantasies” located in fictional and actual accounts of Russian-Roma intermarriage in which, as Alaina Lemon describes, “fascination hoped to subsume, even become a Gypsy.”Footnote 66 Although a number of Romani musicians were adored and elevated to the status of musical stars, for every Varia Panina in prerevolutionary Russia and Anna Shishkina in the diaspora, there stood Anastasia Vial'tsevas and Basil Fomeens who performed Russian Gypsy music with simultaneous commitment and distance. This kind of cultural appropriation, in turn, was facilitated by the stylistic amalgamation that had generated the Gypsy romance to begin with, allowing for an “exoticism ‘light’” music that eased the integration of this repertoire into a broader idea of “our” (i.e., Russian) music.Footnote 67

The duality suggested by this analysis is only complicated by the imperial context out of which the Russian Gypsy romance emerged. Indeed, rather than simply reifying Russian superiority or an Us/Them dichotomy, the Gypsy romance (as part of the broader nineteenth-century salon repertoire) allowed for an expression of what Julia Mannherz has described as an “imperial identity,” which musically encompassed the various Others subsumed within Russia's geo-political borders.Footnote 68 The engagement with musical Orientalism through the consumption and performance of this repertoire enabled a “combination” rather than “juxtaposition” of national, imperial, and cosmopolitan sentiments—a grouping of identities to which “diasporic” can be added within the context of the post-Bolshevik emigration.Footnote 69 This duality is further complicated by the assertion of a common bond between Russian and Romani people that has been articulated by members of both groups. As Alaina Lemon has discussed, Russian and Romani actors have at various times highlighted such a bond, whether through, for example, a perceived mutual engagement with nostalgia (an “agentive emotion linking Russian to Gypsies”), especially as it has been voiced musically, or through a shared positioning against the “‘coldness’ of the West” (a point that underlies a “subtle difference” between Western and Russian conceptions about “Gypsies” as a whole).Footnote 70

Yet the occasional discursive bonding between Russians and Roma and the imperial identity generated through the performance and consumption of Gypsy romances did not counter the unequal undercurrent of Russian-Roma cultural interaction as a whole. This very performance of Gypsy was made up of practices (musical and otherwise) in part crafted in response to Russian expectations of the Gypsy Other as they were delineated in Russian literature, romances, and on the cabaret stage. Reflecting a long-held fascination with the Gypsy that had been articulated by such iconic Russian writers as Alexander Pushkin, Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), and Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), Russian Gypsy music likewise operated on tropes that associated Roma with “sensuality, wild emotionality, ‘inborn’ and bountiful musical talent, love of freedom, and fierce independence.”Footnote 71 Indeed, the performance of Russian Gypsy romances only reified these ideas; while in prerevolutionary Russia, a combination of lyrics and stylistic execution helped inform the Gypsy trope, the genre's efficacy in 1920s Manhattan rested on its specific performance practice for furthering such stereotypes to its Anglophone listeners. In her work on popular entertainment in prerevolutionary Russia, Louise McReynolds underscores the inequitable nature of these enactments. Stating, “Russia's gypsy culture reflected its own desires rather than those of the ethnic group whose life story Russian consumers were rewriting to respond to their own cultural needs,” McReyonold's point can be extended to New York audiences seeking a fantastical, exotic experience and to the émigrés performing this Otherness.Footnote 72

The performance of Russian Gypsy music in prerevolutionary Russia and later in New York City is further problematized by the difficulty, historically, in gauging the extent of the input and agency of Roma in these enactments. While the role of Romani musicians in establishing and maintaining the Russian Gypsy genre is undeniable, the extent to which Roma had a say in creating and managing the Gypsy trope is often obscured by the numerous forces at work—cultural, political, economic—in informing the “Gypsy” genre at any given time for the various stakeholders involved.Footnote 73 As Susan Tebbutt and Nicholas Saul note, Romani cultural representation as a whole is a complex concept, as, in many cases, the “weft threads of role-playing cross over and under, and back again,” until it becomes “harder and harder to see where the images end and the counter-images begin, where the Romanies are playing a role imposed by the gadzo and where they have a role to play in their own right.”Footnote 74 The fact that Roma themselves took part in Russian Gypsy entertainment did not counter the harmful potential of these enactments, a point that Thomas Acton has deemed an “infuriating paradox” as “the more authentic the Roma involved in the performance, the more powerfully dangerous is the stereotyping.”Footnote 75

The troubling aspects of Russian Gypsy music performance took on another dimension in the diaspora, as “Gypsy” and “Russian” were collapsed into a Russo-centric entity and marketed as a single exotic trope to the Western public. The common designation of restaurants as “Russian” in which Gypsy music performances took place point to the subsuming impulse present within the history of the genre. The easy collapse between Russian and Gypsy likewise extended into Western descriptions of Russian Gypsy entertainment, including the review of Club Petroushka's Gypsy choir, which describes the ensemble's power, for example, to elicit the “indefinable Russian spirit.” Through such discourses, “Gypsy” performers thus became affiliated with a bygone, tsarist Russia, a conflation that persisted both in the emigration as well as in Soviet (and later, post-Soviet) Russia.Footnote 76 Ultimately, the efficacy of the performance of Russian Gypsy music in New York rests on what Michael Taussig has described as the “wonder” of mimesis, which “lies in the copy drawing on the character and power of the original, to the point whereby the representations may even assume that character and power,” an interplay between Self and Other drawing on “occidental sympathies which kept the magical economy of mimesis and alterity in some sort of imperial balance.”Footnote 77 Indeed, the success of the Russian Gypsy act lay in the perceived “character and power” elicited through and conferred onto this performance, with Russian Gypsy music making up a significant part of New York's Russian vogue and soon making its way beyond the restaurant stage and into the realm of sheet music, society balls, films, and cartoons as part of a broader image of a lost, prerevolutionary Russia.

Conclusion

On January 31, 1924, less than four months after Club Petroushka opened, an unexpected fire destroyed the interior of the restaurant, and with it, the entire Petroushka enterprise. The fire originated in the Gypsy Room, with an explosion emanating from one of the lamps in the back of the room that instantly ignited the silk costumes and tapestries hanging on the walls, and quickly consumed the third floor before spreading throughout the rest of the building.Footnote 78

Foreshadowing the eventual decline of Russian themed restaurant-cabarets in New York, the demise of Club Petroushka was an early harbinger of the gradual devolution of the Russian vogue into mere cliché. By the mid- to late 1930s, the Russian émigré nightclub emerged as a ready trope in Hollywood films as it was in public writings.Footnote 79 A New York Times article describing the Soviet Pavilion's restaurant at the 1939 World's Fair, for example, contrasts the streamlined, modern establishment with its nostalgic forbearers. Relying on what was by then formulaic images of the Russian émigré restaurant, the article states, “New Yorkers have come to expect Russian restaurants to be dark, with a sinister air, and half expect to overhear plottings of counter-revolution from once-titled White Russian waiters. The long slender blue and yellow flame of the shashlik skewered on swords pierces the gloom, and everybody is bravely gay.”Footnote 80 Countering the worn experience with the new Soviet model, the article goes on to proclaim, “There is none of this sort of thing at the very modern Russian restaurant in the Soviet Pavilion. It is a bright, cheerful place with no dark corners where daydreams or nostalgia might grow.” Relegated to the “corners” of public discourse, the restaurants associated with and presented by the post-Bolshevik émigrés had become passé.

Despite its eventual decline, the Russian nightclub had a central place in the Roaring Twenties. Filling the demand for an exotic experience and, more specifically, for an encounter with a mythologized Russia of the prerevolutionary variety, Russian nightclubs became a staple of Prohibition-era New York. The Russian Gypsy music typically featured in these establishments played a crucial part in enabling this encounter and in creating a “dreamland” for the New York public. The performance practice associated with this genre in particular helped enable this transformative experience, with heightened emotionality and a semblance of achronality characterizing Russian Gypsy music performances in nightclubs, concerts, and on recordings of the time. The efficacy of this performance was only bolstered by the seemingly natural connection between emotion and the “Gypsy” trope, a correlation that was reinforced in contemporary accounts of these musical performances. The positioning of Russian Gypsy music was further complicated within the diasporic context, moreover, with both Romani and non-Romani musicians—all fellow first wave émigrés—performing their much-beloved Russian Gypsy romances for New York's well-heeled elite while simultaneously presenting a profitable product. Like its Midtown counterparts, Club Petroushka ultimately succeeded, if but for a short-lived time, precisely through managing the delicate balance between craft and art, pragmatism and fancy, ushering in a dreamland—however fantastical—momentarily to 1923 New York City through the “wild passionate air . . . of indescribable beauty and expression.”Footnote 81