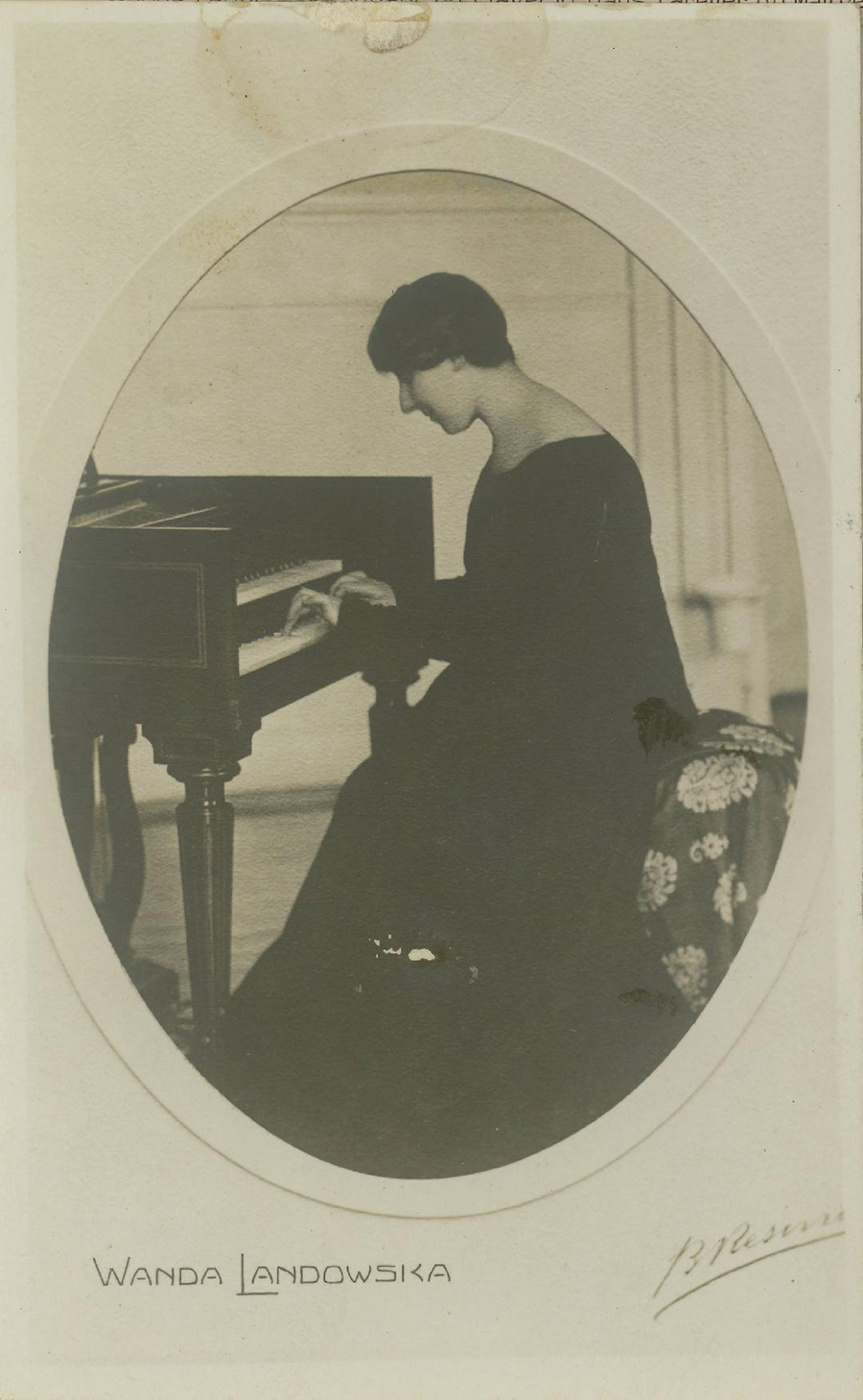

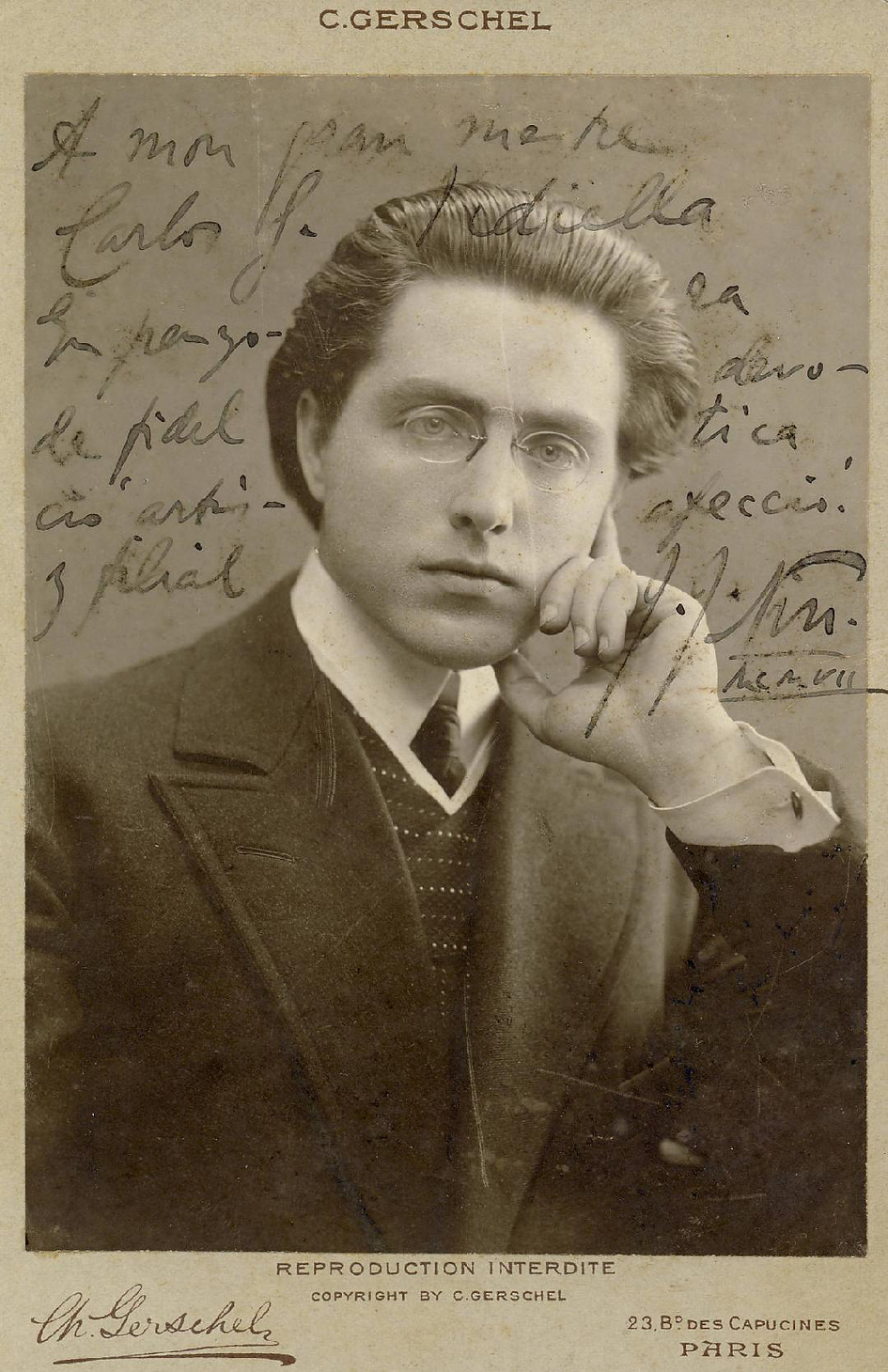

Wanda Landowska (1879–1959) and Joaquín Nin y Castellanos (1879–1949) were, in the context of the Parisian Schola Cantorum during the first decade of the twentieth century, two of the leading artists performing and disseminating the keyboard repertoire, especially that of the French harpsichord school. Georges Jean-Aubry stated in 1909 that of ‘all our seventeenth- and eighteenth-century harpsichordists’ Nin and Landowska were the only honest performers.Footnote 1 But their careers had already diverged. Landowska (see Figure 1) was established as a solo recitalist implementing a revolutionary interpretative proposal and exhibiting an exotic stage persona that featured the harpsichord as a concert instrument to suit her own vision of the music of the past.Footnote 2 Nin (see Figure 2) employed the concert-lecture as his favoured format to promote his ambition as a scholar-performer. Appointed an honorary professor at the Schola Cantorum in 1906 and at the Université Nouvelle de Bruxelles in 1909, he contributed greatly to the uncovering of eighteenth-century Spanish music during the 1920s through his pioneering keyboard music editions and concert programmes (always played on the piano), as well as his own compositions.Footnote 3 Furthermore, their critical reception has had very different results. Landowska has become a legend, an ‘uncommon visionary’ who has attracted hundreds of reviews, exhibitions and documentaries encompassing her impact on the early music revival,Footnote 4 whereas Nin has remained virtually unknown until very recently.Footnote 5

Figure 1 Wanda Landowska, 1905. Barcelona, Centre de Documentació de l’Orfeó Català, Fons Fotografic de l’Orfeó Català, F_LANDOWSKA05.

Figure 2 Joaquín Nin, 1907. Barcelona, Centre de Documentació de l’Orfeó Català, Fons Fotografic de l’Orfeó Català, F_NIN01. The inscription reads ‘A mon gran mestre Carlos G. Vidiella. En penyora de fidel devoció artística y filial afecció. J. J. Nin MCMVII.’

Back in 1909, and within the context of the historical concert understood as a programming strategy that crystallized in the late nineteenth century,Footnote 6 Landowska advocated the revival of the harpsichord as the instrument leading to what is now called historically informed performance practice; Nin, rejecting Landowska’s supposed historicism, supported an ‘updated’ performance on the piano. This difference resulted in a fierce controversy conducted between November 1911 and October 1912 simultaneously in French and Spanish journals, specifically the Revue musicale S.I.M. of Paris (hereafter RMSIM), the Revista musical of Bilbao (RM) and the Revista musical catalana (RMC), the journal of the Orfeó Català in Barcelona.Footnote 7 This personal feud between the two competing artists is essential to the understanding of their different approaches to performance and the irreconcilable attitudes towards the appreciation of early keyboard repertoires that was to extend beyond French and Spanish boundaries.Footnote 8 For this purpose, a large quantity of unedited correspondence preserved in the Biblioteca de Catalunya (Barcelona) and in Landowska’s papers at the Library of Congress (Washington DC) has been studied and compared with the relevant press articles in the context of the performers’ agendas. Orchestrated by Nin against Landowska, the controversy was used as an aggressive marketing strategy initiated at precisely the time Nin was about to make his début in his former home country, Spain. The unforeseen consequences lasted for decades.

‘La voilà bien la polémique des Revues!’

Nin’s soirée dedicated to the music of J. S. Bach at the Parisian Salle Aeolian on 21 March 1906 was reviewed in Le courrier musical. Footnote 9 This concert was the second in Nin’s ambitious series ‘Étude des formes musicales au piano depuis le XVIe siècle jusqu’à nos jours’, originally programmed as a 12-concert series, though only five of the concerts actually took place.Footnote 10 This review echoed Nin’s artistic choice to play Bach on the modern piano, as explained in the introduction to his concert, in direct opposition to Landowska’s preference for the harpsichord, as advocated in her article ‘Bach et ses interprètes’:Footnote 11

In addition, the very interesting preface, in which Mr Nin introduces us to his ideas and his artistic intentions ahead of his programme, shows that this is not a random choice. It is necessary that we pay particular attention to this manifesto, since it will, undoubtedly, meet some opponents. It claims that the piano has an absolute right to appropriate the music written for the different keyboard instruments in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. We believe we remember that a booklet published under the signature of Mrs Wanda Landowska last year in the Mercure du France expressed a completely opposite opinion. Such is the controversy in journals! Only Mrs Landowska is a harpsichordist: she too opposes the ‘propaganda of the deed’.Footnote 12

Nin, like many others, regarded the harpsichord as a ‘sonically weak and mechanically imperfect instrument, poorly suited for the works of the master’, in the words Edward L. Kottick used to describe the early twentieth-century general view of the harpsichord.Footnote 13 Nin justified his use of the piano in the performance of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century keyboard literature on the basis of the commonplace, ‘Had Bach only known of the modern piano …’.

In addition to his unfinished series ‘Étude des formes musicales au piano’ (1904–7), Nin was involved between 1906 and 1910 in concert-lectures across Europe alongside Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi (1877–1944) and Jean-Aubry (1882–1950) promoting French, Italian and German eighteenth-century music played on the piano.Footnote 14 He also took his vision of performing early repertoires to Havana (Cuba), performing some historical concerts there in 1905 and founding the Sociedad Filarmónica in 1910. But on his return to Europe in summer that year, Nin had neither yet made his début in Spain – leaving aside a couple of concerts in 1897 and 1899 when he was still a student of Carles Vidiella in Barcelona – nor established a successful career as a performer, despite his two honorary professorships at the Parisian Schola Cantorum and the Université Nouvelle de Bruxelles. By contrast, Landowska was a successful performer, frequently invited to the major European capitals and well received in Spain, particularly in the context of the Orfeó Català in Barcelona: she débuted at the Palau de la Música Catalana in December 1909 and represented the sonorous counterpart of the antiquarian aesthetics supporting Catalan modernism.Footnote 15

Moreover, Landowska’s participation from 1908 in the Bach Festival (Bachfest) established her as the foremost advocate of the harpsichord as the instrument on which Bach’s works should be performed.Footnote 16 In 1910, at the Duisburg Bach Festival, she challenged those who maintained that Bach’s works were written for the clavichord. She proposed that her opponents play the Italian Concerto, BWV 971 (specifically written for a two-manual harpsichord), the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue in D minor, BWV 903 (already established in the piano repertoire) and any toccata or fugue on a ‘Silbermann clavichord from Bach’s time’ that she brought with her, which had been lent by her friend the French critic and director of the RMSIM Jules Écorcheville.Footnote 17 This was, according to Arnold Dolmetsch (1858–1940), a ‘small “gebunden” [fretted] instrument, in bad condition’, and her conclusions were thus drawn upon ‘her own unskilled playing upon an unplayable instrument’, as he wrote to the harpsichordist Violet Gordon-Woodhouse (1872–1948) a year later.Footnote 18 But Landowska was determined, first, to demonstrate how Bach’s music could not have been meant to be played that way or, by extension, on the piano (a ‘perfected clavichord’),Footnote 19 and secondly, to solve the dilemma ‘harpsichord or piano’ by posing the question, ‘For which instrument did Bach write his keyboard works, for the harpsichord or for the clavichord?’Footnote 20

To further her argument, Landowska carried out a practical ‘tournament’ at the ‘kleine’ Eisenach Bach Festival in September 1911. She played some works by Bach on the harpsichord, after which the pianists Bruno Hinze-Reinhold (1877–1964) and Friz von Bose (1865–1945) repeated them on the piano. According to the RMSIM, she succeeded in converting the sceptics.Footnote 21 The German press offered a more neutral judgment. Alfred Heuß wrote in the German journal of the International Musical Society that both harpsichord and clavichord were instruments used by Bach and noted that Landowska’s success was due to the irrelevance of her opponents.Footnote 22 Max Schneider stated in Die Musik that if audiences had the chance to hear and compare, nobody would reject the modern piano in favour of the harpsichord.Footnote 23 However, as Harry Haskell rightly stated years later, Landowska had successfully made her point: ‘No longer could the harpsichord be regarded as a mere antiquarian curio.’Footnote 24 Not only was it established as an appropriate set dressing when early music was the subject, but its new sonority attracted avant-garde composers who helped to establish the instrument as a valid means of expression in its own right in the years to come.

On 11 April 1911, Nin addressed a letter to his friend the Spanish violinist Joan Manén (1883–1971), with whom he had toured Germany and the Netherlands in 1909 and 1910. In it, Nin expressed his antipathy towards Landowska’s interpretative approach:

I am outraged that the Orfeó [Català] has hired L… again, and she talks already about coming next year. Provincials to the end. The ‘cage for flies’ (as Gauthier-Villars describes the harpsichord) and the tricks from that pair of Jews conning them like the Chinese.Footnote 25

He then makes clear that his intention is to ‘fight the wandalism’ (‘combatre el wandalisme’), to which end he is writing a book that will bury the harpsichord once and for all. These and many other scornful references to Landowska in the correspondence between Nin and Manén make it possible to assert that Nin was interested not only in debating an aesthetic and performance approach but also, and more importantly, in establishing a personal controversy based on anti-Semitic and misogynist prejudices and on his jealousy of Landowska’s success, achieved through years of careful programming across Europe in a profitable association with the Maison Pleyel and the impresario Gabriel Astruc.Footnote 26 In July 1911, Nin began to compile documents to oppose the harpsichord affair, as ‘it had done very well in disappearing once … only snobbism could have resurrected it … I do not say Judaism I do not know why, but this is it in the end’.Footnote 27 And, as he confessed to Manén in September, the two essays on the topic ‘Clavecin ou piano?’ that he added as footnotes to two of the articles compiled in his promotional brochure Huit années d’action musicale, released in October 1911 in Brussels,Footnote 28 were a clear provocation to Landowska, and were calculated to start a controversy.Footnote 29

These two essays are indeed his statement of intent and a summary of the arguments he displayed in the forthcoming ‘beating’ of those ‘wandals who thought that the faked resurrection of this infected cage of flies that we call the harpsichord would be useful for the Art’.Footnote 30 At that time, October 1911, Nin was about to publish his book Idées et commentaires,Footnote 31 and to tour southern France and Spain alongside the Spanish violinist Joaquín Blanco-Recio (1884–1913). This tour, on which he performed eighteenth-century repertoire on the piano, took place between January and March 1912 and involved his débuts at several Spanish philharmonic societies: Bilbao, Vitoria, Oviedo, Santander and Madrid.Footnote 32 Nin thus devised the controversy, the arguments of which would inevitably connect his name with that of Landowska, in a desperate attempt to find a niche for himself among her followers. Nin’s propaganda strategy, carefully wrapped as an aesthetic discussion supported on the authority of musical criticism, is not alien to the eyes of the contemporary reader familiar with twenty-first-century social media stirring.

Piano versus harpsichord: from Paris to Bilbao

In November 1911, Carlos Gortázar issued, under his pen name Ignazio Zubialde, an article entitled ‘¿Piano o clave?’ in the RM. Footnote 33 He translated into Spanish Nin’s first essay from Huit années d’action musicale and quoted fragments from Landowska’s ‘Bach et ses interprètes’.Footnote 34 Gortázar believed that the question at issue – ‘Should the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries be played on the piano or on the harpsichord?’ – was ‘insoluble’,Footnote 35 and that it positioned Landowska and Nin as the leaders of two different interpretative approaches.

Huit années d’action musicale and Gortázar’s article mark the public opening round of the controversy between the pianist and the harpsichordist. As Nin himself admitted to Manén on 25 November 1911: ‘The battle has started between W. C. and me on this matter.’Footnote 36 His several references to Landowska as ‘vandal’ and ‘W.C.’ represent not so much a play on her name as the fact that Nin regarded not just the harpsichord but the harpsichordist as the opponent to be eliminated. Nin maintained that several European journals – French, Belgian and Swiss – were ‘interested in the matter’,Footnote 37 but the controversy found a triple perspective only in the RM, the RMSIM and (from July 1912) the RMC.Footnote 38 Adding further fuel to the fire, he also signed in November 1911 an article entitled ‘À propos du Festival Bach à Eisenbach [sic]’, published in Paris in December 1911, attributing the success of Landowska’s harpsichord to its picturesque quality despite its lack of expression.Footnote 39 This article coincided with the aforementioned letter to Gordon-Woodhouse in which Dolmetsch questioned Landowska’s expertise on the subject of early music (see above, note 18).

The controversy took off following Nin’s ‘À propos du Festival Bach’ and reached its climax in July 1912. Landowska maintained, in a letter sent to Nin from Kharkov (Ukraine) on 22 February 1912, that ‘a controversy on the subject of the harpsichord is always excellent to support my cause’,Footnote 40 but in a reply to Nin published in March 1912 in the RMSIM, she complained that it was a bad moment to start a controversy since she was ‘touring and overworking’.Footnote 41 Several retorts from one to the other, spiced with some more sour private correspondence, followed until they concluded their contributions in Paris in July 1912.Footnote 42 Landowska took the opportunity to challenge Nin to a piano–harpsichord ‘match’ to prove the arguments that Nin was intending to compile in a book.

Simultaneously, from February 1912, Nin was in discussion with his friend Eduardo López-Chávarri in the RM following the latter’s support for Landowska in translating into Spanish some excerpts from her Musique ancienne in December 1911.Footnote 43 The conclusion, ‘We certainly can play Bach on the piano, but we should play it on the harpsichord,’Footnote 44 taken from ‘Le clavecin chez Bach’, was in clear opposition to Nin’s approach. In visual terms, it was as if Landowska preferred ‘to contemplate an eighteenth-century etching in its modest frame of the period rather than in the most splendid modern frame’.Footnote 45 In other words, eighteenth-century music should be played on a ‘harpsichord-frame’ in order to contextualize the repertoire. Whereas Nin, following his idea that ‘music is above all an art of expression’, ‘put musical truth over historical truth by playing these works on a simple piano, that is to say, on the most expressive and perfect of all keyboard instruments’, as he claimed in the programme notes for his concert in Brussels on 31 January 1912.Footnote 46 To Nin, the piano was ‘an aesthetic successor to the clavichord and a historical successor to the harpsichord’.Footnote 47 Accordingly, Díaz Pérez de Alejo concludes in her analysis of the controversy that, whereas Nin based his approach ‘on the idea that music is expressive in itself, taking advantage of the progress in instrument manufacturing, Landowska established a correspondence between repertoires and the historical instrument upon which they should be played, so that her interpretations correspond to the periods in which works were written’.Footnote 48

This last statement is not completely accurate, since Landowska benefited from the progress in piano manufacturing as applied to modern Pleyel harpsichords. And this was Nin’s second argument against the harpsichord, and against Landowska too.Footnote 49 Nin pointed out that ‘concert harpsichords are larger than concert grand pianos’, especially those of the Maison Pleyel.Footnote 50 Pleyel harpsichords were, indeed, a wonder of piano manufacture, as Jean-Claude Battault claimed when he compared Pleyel, Érard and Gaveau instruments,Footnote 51 and as Martin Elste recently stated, ‘Their harpsichords combined nostalgia with mechanical progress.’Footnote 52 Nin continued that it was the ‘new’ sonority of the harpsichord and not its pretended historicism that accounted for its success: ‘Only the curiosity attached to every new means of expression, to every unknown or unfamiliar sonorous subject, could thus make the current resurrection of the harpsichord seem attractive.’Footnote 53 Regardless of his real intention, Nin was something of a visionary. As Richard Taruskin judged in the 1980s, after several decades of revival, ‘The historical hardware has won its wide acceptance and above all its commercial viability precisely by virtue of its novelty, not its antiquity.’Footnote 54 And it all began with Landowska.

The issue ‘piano ou clavecin?’ was, by summer 1912, a ‘matter of taste’ and, as Écorcheville, echoing Gortázar, claimed, both ‘insoluble and badly formulated’.Footnote 55 It was at this point that Nin developed his propaganda strategy, disguised as an aesthetic discussion, into a vicious attack against the ‘snob’ Polish harpsichordist and all her flatterers.

Nin versus Landowska: Barcelona and the Pleyel prototypes

Nin’s extensive articles published in July 1912 in both the RM and the RMC are clearly fed by his antipathy towards Landowska.Footnote 56 They were, respectively, an attack on López-Chávarri in his role of Landowska’s ‘thurifer’Footnote 57 and a clear provocation of Landowska through the Orfeó Català’s journal. Nin emphasized the idea that the harpsichord was condemned ‘by the harpsichordists themselves’Footnote 58 and underlined that, ‘Bach’s praises for Silbermann’s pianos in 1747 could be considered the greatest victory of the piano in all ages.’Footnote 59 These arguments, displayed among a handful of (sometimes distorted) historical quotations led to the conclusion that,

Those who, eager for new sensations, for fake historical reconstructions, for snobbism à outrance, reject the piano and accuse it of deforming Bach’s ideal, ignore the fact that geniuses such as that inaccessible sovereign write neither for a period nor for an instrument: they write with their soul, for the soul and eternity […] The voice of the harpsichord does not transcend our ears, because it is voice without soul.Footnote 60

In other words, the harpsichord was a superficial apparatus. This is indeed a well-founded aesthetic opinion: not only Landowska when playing Bach on the piano, but several performers or connoisseurs had to agree with the fact that Bach’s and other eighteenth-century composers’ music could be played on the piano, thus siding with the ‘traditional’ mode in performance – as defined by Hermann DanuserFootnote 61 – and according, nonetheless, with historical evidence, as Nin himself pointed out. However, Nin’s most controversial contribution was addressed specifically to the alleged authenticity of Landowska’s so-called harpsichord, the Pleyel Grand Modèle de Concert, a few weeks after she premièred it at the Breslau Bach Festival in June 1912. This instrument was a technically improved Pleyel harpsichord which included a 16-foot stop operated by a seventh pedal.Footnote 62

Nin stated in the RM that, ‘There is an abyss between the harpsichord that Ms Landowska plays and Bach’s instrument because, in the latter, strings were plucked by quill plectra and in that [of Landowska] they are plucked by leather plectra, which completely modifies the sonority, removes a great part of its sharpness and provides it with apocryphal colour and timbre,’ and moreover, ‘Bach’s harpsichord had manual registers’ – hence, the pedal registers in Landowska’s were anachronistic.Footnote 63 In reality, as Battault remarked, during the early twentieth century, harpsichord manufacturers other than Pleyel (with the collaboration of Landowska) – Gaveau, for instance – incorporated leather plectra based on some late eighteenth-century French models.Footnote 64 It was the French harpsichord manufacturer Pascal Taskin (1723–93) who adapted, in the 1760s, a fourth-register peau de buffle. Kottick maintains that this register – the ‘quietest’ on the instrument because of its plucking deep into the string and because the plectra were wider and softer – allowed ‘small dynamic changes through finger velocity’ and was usually found together with a mechanism of knee levers or pommels to operate the registers.Footnote 65 Needless to say, Bach would not have used these prototypes, but Pleyel and other manufacturers took their inspiration from the restored 1769 Taskin prototype. Their harpsichords appeared as a marvel of piano manufacturing inserted into Watteau-inspired external cases. The ephemeral bird-quill plectra were replaced by thicker leather plectra that would last longer in these modern instruments, which were intended for use in a different environment: the public concert.Footnote 66

Nin’s second argument published in the RMC ran as follows:

I do not deny this spell, in the same way that I do not deny that of the pianola, because I have for a long time known that it is very easy to seduce the human ear with new impressions […] It is, however, curious that, despite Ms Landowska’s pro-harpsichord propaganda, spread over the last 10 or 12 years [and] supported by the tireless generosity of the Maison Pleyel of Paris (who spare no expense on advertising), and despite her undeniable talent, the movement has caught on very little. The piano, on the other hand, has established itself in less than 50 years.Footnote 67

Nin persisted in the idea that the harpsichord success was a fad and focused his attack on Landowska as a mere commercial tool of Pleyel. As Elste recently wrote, ‘Hearing Wanda Landowska meant hearing a Pleyel harpsichord with two keyboards and a variety of different sounds,’ because she had entered into a contract with Gustave Lyon, then managing director of the Pleyel firm, according to which she would perform only on a Pleyel harpsichord, loaned to her free of charge.Footnote 68 But Nin had also intended to champion early repertoires on the harpsichord, as Landowska pointed out in a letter addressed to Nin himself. It was only when Pleyel refused to provide him with a harpsichord and Steinway provided him with the instrument for his recitals that he became a harpsichord antagonist.Footnote 69

These two articles of July 1912 mark the turning point of the controversy. Well aware of Nin’s interest in maintaining ‘a controversy with me at any price […] to promote himself at the expense of another’s success’,Footnote 70 as Landowska told her student and López-Chávarri’s protégé, the Spanish pianist José Iturbi (1895–1980), she and her husband, Henri Lew, decided to break into the Spanish side of the controversy. Landowska never signed a contribution to the RM, but she published an article in the August–September 1912 issue of the RMC supported by two members of its editorial board.Footnote 71 The correspondence between López-Chávarri and Lew, dated between August and September 1912, reveals a series of arguments that Lew provided and López-Chávarri published,Footnote 72 these eventually leading to the termination of the latter’s friendship with Nin.Footnote 73

With regard to refuting Nin’s arguments about the harpsichord’s lack of expression (a matter which exposed López-Chávarri’s ignorance concerning technical aspects of the instrument), López-Chávarri was particularly interested in knowing whether or not it was possible to obtain crescendos and diminuendos on the harpsichord. Lew informed him that the harpsichord could obtain some dynamics either by ‘sophistication in the touch’ or by adding and decreasing the registers,Footnote 74 and, as expected, Nin responded:

I indicated to him [López-Chávarri], through data, dates and arguments a thousand times proved, the historical, aesthetic and musical reasons that opposed the revival of the harpsichord as proposed by Ms Landowska and as sanctioned and even praised by Chávarri. It was preferable, especially with regard to [López-Chávarri’s] honour, to assume that he either ignored or neglected the information I presented; if he knew or remembered it otherwise, it would be foolish to insist on the supposed advantages of the revival of the harpsichord as being the only instrument capable of providing us with a clear and exact impression of the sixteenth-, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century keyboard literature.Footnote 75

The ‘to be continued’ stamped at the end of the article and Nin’s persistence in considering Landowska’s harpsichord ‘a mystification’ made López-Chávarri suggest bringing the Pleyel engineer and director Lyon into the controversy. Lew, of course, considered this disproportionate,Footnote 76 and lectured him about historical harpsichords featuring either manual or pedal mechanisms to operate registers,Footnote 77 hoping for this to be published. Three days later, on 27 August, Lew confirmed that the instrument played by Landowska in Valencia in May 1912 was ‘an exact copy of Silbermann’s instruments’:

With regard to the registers, it possesses two made of quill and two of leather […] Ms Landowska has given a recital, in the Musical Instruments Museum in Berlin, in which she played successively on historical harpsichords, among them a prototype that belonged to Bach, and on her modern harpsichord, in order to prove the differences of sonority.Footnote 78

López-Chávarri did not mention any of these arguments in the October issue of the RM, but following Lew’s indications, in a clear attempt to jeopardize the publication of the Spanish translation of Idées et commentaires in the same journal, he accused Nin of ‘arriving late’, since he had published ‘Anciens et modernes’ after Landowska’s ‘Mépris pour les Anciens’, and ‘La raison du plus fort’ after she had published ‘Les transcriptions’.Footnote 79 López-Chávarri also quoted some lines from Nin’s article published in Le monde musical in 1909 praising Landowska’s performance. Nin had written:

Wanda Landowska made us hear, sometimes on the harpsichord, sometimes on the piano, music by Bull, Purcell, Chambonnières, Couperin, Rameau, Scarlatti, Pachelbel, Bach and Mozart finely, simply, with no boasting, with sonorities that affected but did not knock us out, with a very pure musicality […] We should thank Wanda Landowska for not playing early music with the impertinent correctness that some scholars are still claiming, but with the fierce conviction of a very modern, very sensitive and very strong soul, which have found in those pages all the life our ancestors left in them, with all their expression and their nuances.Footnote 80

When López-Chávarri’s article was released, Lew suggested to Lyon that he should not meet the request to take part in the controversy: ‘It is not necessary that the Maison Pleyel take Joaquín Nin seriously and give him the honour of an answer […] He is going to receive in the next issue of the Revista catalana of Barcelona a beating from Wanda that will keep him quiet for a while.’Footnote 81 In her contribution to the Catalan journal, Landowska once more challenged Nin to compete with her in a practical match and persisted with the idea that Bach’s works were not intended to be played on the clavichord. She referred to her demonstration in the 1910 Duisburg Bach Festival and to her article ‘Für welches Instrument hat Bach sein “Wohltemperiertes Klavier” geschrieben?’Footnote 82 to conclude that:

Clavichords in Johann Sebastian Bach’s era were gebunden, that is to say, one string was assigned to two or three keys and was hit in two or three different places. It seems that Daniel Faber started building unfretted clavichords in the first half of the eighteenth century, but they were very rare, and all unfretted clavichords found in collections date from the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote 83

Landowska’s student Juana Barceló stated in 1969 that she ‘carefully specified [to her students] which pieces belonged to each instrument’,Footnote 84 which – considering that the inventory of Landowska’s possessions made by the Nazis when they entered St Leu-la-Forêt in February 1941 listed three clavichords – may support her arguments.Footnote 85 Nevertheless, Dolmetsch and Ralph Kirkpatrick (1911–84) pointed out Landowska’s biased ‘opposition’ to the clavichord, both of them referring to the controversial article ‘Für welches Instrument hat Bach sein “Wohltemperiertes Klavier” geschrieben?’ Dolmetsch, a clavichord and harpsichord maker, commented to Gordon-Woodhouse in 1911 that Landowska ‘has written many articles in French and German, misquoting texts, giving out wild statements, drawing illogical conclusions with such apparent authority, persuasive eloquence and cleverness that many people believe it’.Footnote 86 It is also worth mentioning here the meeting between Landowska and Dolmetsch in 1927, when she visited Haslemere with some of her students. She addressed him as ‘Le Maître’ and expressed admiration of his instruments. Dolmetsch nonetheless refused to give her one of them, saying that she knew nothing about harpsichord playing.Footnote 87 In 1981, Kirkpatrick remembered:

On arriving in Paris in the autumn of 1931 to study with Landowska, I encountered an attitude towards the clavichord that ranged from considerable opposition on her part to total ignorance on the part of most of her students. She even made some attempt to counteract my leanings towards the clavichord by causing me to read a translation of her polemical article of 1911 ‘Für welches Instrument hat Bach sein “Wohltemperiertes Klavier” geschrieben?’Footnote 88

These facts clearly suggest how Landowska’s many articles and writings in defence of the harpsichord responded not only to the dissemination of her aesthetic credo but also to the promotional campaign that she started in 1904, when entering the contract with Pleyel, to become the ‘high priestess of the harpsichord’. Nin’s claim that Landowska was the commercial face of the Maison Pleyel was not completely unfounded.

Epilogue

To sum up, following a brief and direct debate between Nin and Landowska in the RMSIM, the controversy became a hot topic in the Spanish musical press. Landowska remarked in 1953 that she was aggressive because ‘pianists [such as Nin] were against the harpsichord, probably against me too […] They were against because [of] the idea of interpretation, and [because] the sound was so different from the piano, and they were enemies, immediately. And imagine how hard I had to fight with them.’Footnote 89 This undoubtedly refers to those years of the controversy in which she wrote articles profusely, published Musique ancienne and developed several propaganda strategies that would eventually market her as the unique artist able to perform Bach and his contemporaries in their authentic way – on the harpsichord. In 1913, her appointment as professor of harpsichord at the Königliche Hochschule in Berlin created the first generation of German harpsichordists, including names such as Alice Elhers (1887–1981) and Gertrud Wertheim (1890–?), and the movement spread through her teaching at the École de Musique Ancienne in St Leu-la-Forêt. But this inevitably created some competition too. Ruggero Gerlin (1899–1993) and Kirkpatrick were known worldwide in the 1930s. After meeting Landowska in Lisbon before she departed for the USA in late 1941, the musicologist and harpsichord and clavichord player Santiago Kastner (1908–92) wrote to her Spanish pupil Joan Gibert Camins (1890–1966):

She talks very well about you, but badly about all other harpsichordists. And many of them worked with her. I finally told Wanda: ‘You must be a bad teacher and pedagogue because everybody who worked with you is a bad player.’ She changed the subject […] I would never play for her, so she cannot tell if I play well or badly. We discussed several topics on early music, but, sometimes, she claims things that do not harmonize with modern musicology and I cannot agree with Wanda’s statement attributing all Bach’s (keyboard) output to the harpsichord.Footnote 90

On his return from Havana in 1910, Nin had the same need of promotion as Landowska, and this accounts for his attempt to write a book in opposition to but at the same time benefiting from Landowska’s success in playing the harpsichord. This idea came from a conversation with Evelina Pairamall (1870–?), a pupil of Heinrich Schenker, that took place in Vienna in November 1910 at a soirée in honour of Landowska. Pairamall addressed a long letter to López-Chávarri, dated Vienna 19 April 1913, to apologize for the ‘acute controversy between you and Mr Nin on the topic Piano or Harpsichord’ in the RM. Footnote 91 She describes how, having received some lessons with Landowska in Vienna and Munich, she met Nin and they engaged in a conversation about the harpsichord:

Mr Nin told me that he was about to write a book on this topic. He asked me, as he did not know the German language at all, to work with him – in an impartial way, of course! – and share my research, done (in order to save him time and money) on German books that contain information regarding the harpsichord.Footnote 92

The original handwritten letter was sent by López-Chávarri to Lew and Landowska. It is preserved, together with a set of three copies of a typewritten edited version (presumably made by Lew), in the folder entitled ‘Contre le clavecin – Histoire Nin’ in Landowska’s papers. The edited version of the letter is very relevant because some fragments included in the original were consciously deleted, including the following: ‘The more I advanced in this research that I had begun in order to enlighten myself about the harpsichord, the more I reached different results from those Ms. Landowska had obtained from her research on German sources.’Footnote 93 Nonetheless, the edited version retained the following: ‘I sent these comments, these arguments, with the translations to Mr Nin, who, in turn, has been very careful to have them verified, sometimes polished, by musicologists in Brussels.’Footnote 94 According to the correspondence between Lew and López-Chávarri, these three copies were intended to be sent to Écorcheville (at the RMSIM), to Pujol and Lliurat (at the RMC) and to Gortázar (at the RM),Footnote 95 although it seems that Lew did not in the end send them.Footnote 96 A year later, in early summer 1914, Nin confessed to Lew that he had launched the controversy in order to gain publicity but that it had also benefited Landowska, as Lew reported in a letter to López-Chávarri:

‘I do not know German,’ he [Nin] said, ‘and I did not have enough money to provide myself with the necessary books, but she [Pairamall] took care of it. You should not blame me,’ he said; ‘it was publicity for both of us.’ ‘We do not need it, dear Sir,’ I said. ‘We always need publicity,’ he replied to me, sneering.Footnote 97

At this point, there is no doubt that both performers made biased use of the sources at hand in order to support their own cause in a media stir triggered by Nin, and that the consequences lasted for decades. In 1965, Denise Restout added a note to the folder ‘Contre le clavecin – Histoire Nin’ which reads:

Myron Wood at his visit July 31, 65 told me that he was a friend of Joachim Nin’s daughter Anaïs, a writer living in New York. Her father, who abandoned his family and was a terrible egocentric[,] towards the end of his life said to her that he regretted the feud he had with WL and would like to apologize but was too proud to do it.Footnote 98

Looking beyond the personal aspect of their confrontation, it has to be recognized that the Nin–Landowska controversy encouraged an unprecedented and renewed interest in early repertoires and instruments in the Spanish context. One immediate example is Joan Salvat’s concert at the Palau de la Música Catalana in Barcelona on 21 December 1913. The programme featured pieces from Landowska’s and Nin’s repertoires, such as Rameau’s Le rappel des oiseaux and a minuet from Bach’s Notenbüchlein für Anna Magdalena Bachin, and Salvat performed it on a restored clavichord built in Barcelona in 1801 by Josephus Alsina.Footnote 99 In the pre-concert talk he asserted that,

The repeat visit of Ms Landowska, together with the controversy caused by Mr Nin’s article in our Revista 102–103, has awoken the curiosity of many music-lovers interested in early music; they are seeking everywhere strange specimens that look like Landowska’s harpsichord (despite the fact that we know now that this was a reproduction of models carefully preserved in foreign museums).Footnote 100

The impact of the controversy was such that the correspondent in Brussels for the RMC, A. M., summarized in September 1912 that,

It is evident (and also understandable!) that we cannot go back to early art, to early music, without thinking, at the same time, about the instruments upon which that music was played […] How could we not dream of […] listening again, not only to early music, but also to early sonorities?Footnote 101

Conclusion

The controversy between Nin and Landowska should therefore be regarded as a milestone in the revival of early music. It showcases a public confrontation between two performers who supported antagonistic performance approaches with regard to their organological choices for the same eighteenth-century keyboard repertoire, rooted in Bach and the French harpsichordists. Both employed a biased interpretation of historical sources in the media to champion their unique interpretative truth and to gain their audiences’ support.

More than anything else, the controversy was a marketing strategy orchestrated by Nin in order to take advantage of Landowska’s success by discrediting her favoured instrument, the harpsichord. However, the outcome of nearly a year of incendiary penmanship was quite the opposite: Landowska secured her position, while Nin was obliged to reformulate his agenda, championing from the late 1910s eighteenth-century Spanish keyboard literature in order to secure his niche in the growing early music market. This led to the publication of the first two anthologies of eighteenth-century Spanish keyboard music, the Classiques espagnols du piano.

In the end, the controversy represents two contemporary and valid interpretative proposals, both of which improved the understanding and appreciation of the music of the past and contributed to the further development of the early music revival in Spain and beyond. The arguments and concerns that sustained this feud still persist in the early music market, leading to a great variety of performance approaches, from the choice of instrument to the application of historically informed performative criteria. As has been argued, Landowska emerged as the winner, and the harpsichord was to become the standard instrument for the performance of early keyboard music by virtue of its exotic uniqueness and its ability to connect the present with a distant past. The harpsichord played an incontestable role in the various steps of the historically informed performance movement and, paradoxically, assumed the role Nin had once given to the piano: it became established as the instrument able to encompass all keyboard literature prior to the nineteenth century. Perhaps Landowska might in the end have thanked Nin for bringing this unexpected media interest to her cause and for engineering her elevation to the status of ‘high priestess of the harpsichord’.