Two titles: one concerto

There cannot be many individually published concertos from the eighteenth century for which no composer is named in the title, but the British Library possesses a particularly interesting example that – uniquely in the eighteenth-century English concerto repertory – makes systematic use of material taken from traditional music. This consists of a set of nine engraved partbooks (not ten as stated in the library catalogue) in upright format, each of which comprises a bifolio containing music only on the inner pages (numbered 2 and 3), the outer pages remaining blank.Footnote 1 The names of the parts are: violino primo concertino; violino primo ripieno; violino secondo concertino; violino secondo ripieno; alto viola; violoncello; basso continuo; corno primo; corno secondo. Exceptionally, the basso continuo part, which was evidently intended to serve as a folder for the rest, has a title engraved in a framed box on its otherwise void opening page. This reads: ‘A | CONCERTO | Principally form'd upon subjects | taken from three Country Dances, | accompanied by a first & second Horn. | London | Printed by John Johnson in Cheapside’.

Johnson was continuously active as a music dealer and publisher between 1740 and the year of his death (1761), and his widow, Ruth, appears occasionally to have continued to use his imprint up to her own death in 1777. No catalogue raisonné of his productions yet exists, and estimated dates for them (the British Library has ‘1745?’ for the present concerto) vary widely and fairly arbitrarily. Around 1754, Johnson issued a catalogue of his publications.Footnote 2 This does not list the ‘country dance’ concerto, a fact that gives us at least a working terminus post quem.

For a first mention of the concerto, we must go to an advertisement in the London Chronicle of 9–11 November 1762. In it, Johnson's widow announced publication of the arias from the third act of Thomas Arne's Artaxerxes, but also took the opportunity to list several other items from her current stock, among which we find ‘A Concerto from three Country Dances’. The significance of this mention is twofold: it shows that there was already a move to condense the title, and it provides a terminus ad quem. Catalogues issued by Ruth in her late husband's name in 1764 and 1770 list the work under the same title, priced at 2s.Footnote 3

Much later, around 1782, the music dealer and publisher Robert Bremner issued what he called an Additional Catalogue listing items acquired, via their respective widows, from the stocks of Peter Welcker and John Johnson. He introduced the catalogue with this notice:

The following, among which are many valuable and classical Works, were formerly the Property of the late Mrs. Johnson of Cheapside, Mrs. Welcker, of Gerrard-street, Soho, and others; and are now to be had at Mr. Bremner's, he having purchased the Plates and Copies. Those who have seen the Catalogues of the original Publishers, will discover that the Articles are, in general, greatly reduced from their former Prices. The Reduction will continue 'till the remaining Copies are sold.Footnote 4

Under the rubric ‘Concerts’ (meaning ‘Concertos’) Bremner lists no concerto based on country dances, but an item entitled simply ‘A Medley Concerto —’, priced at 1s 6d, catches the eye.Footnote 5 A sequence of three country dances, presumably independent of each other in their original state, self-evidently constitutes a ‘medley’, so this altered title could plausibly be an alternative description of the same concerto that had either gained a certain currency in concert life or was coined especially for the Bremner catalogue.

When one considers the output of eighteenth-century London publishers, it always pays to study the preposition before the name on the imprint. ‘By’ implies that the publisher is executing the task of engraving and printing on behalf of someone else, usually the author, whereas ‘for’ implies that he is acting on his own behalf. In the first case, the publisher is generally the chief financial beneficiary of the edition, although the author may recoup his costs via subsidy from a patron, from subscribers or from acting himself as a stockist and seller of the publication. In the second case, the publisher bears all the costs, relying on sales alone to recoup his outlay.Footnote 6 So it is fairly clear that the author decided on and financed the publication of the parts for this concerto ‘printed by John Johnson’. Presumably he also proofread them, which may account for their high level of accuracy by contemporary standards.

Less accurate, however, was an anonymous keyboard arrangement of the same concerto published around the same time or a little later by Johnson.Footnote 7 Headed ‘A Concerto, the subjects taken from 3 Country Dances’, with ‘LONDON. Printed for J. Johnson in Cheapside’ appearing at the foot of the same opening page of music (there are five pages in all), this is a piece of hackwork that can hardly have involved the composer. It belongs to the vast corpus of such arrangements down the ages that are just about adequate to remind players of music heard by them earlier in its original state but not imaginative or skilful enough to be either musically effective or technically well fitted to the instrument. However, the fact that the arrangement was made at all tells us something important: the concerto must have ranked as – employing the jargon of the time – a ‘favourite’ work, frequently heard in public performance at theatres, pleasure gardens or concert rooms.Footnote 8

From the records of London theatrical life, as reported in contemporary press notices, we are able to establish with some degree of certainty both the period and the context of the Medley Concerto. On 6 December 1752, the London Daily Advertiser announced a forthcoming season of ‘M. Midnight's Medley Concert and Oratory’ at the New Theatre in the Haymarket (the ‘Little Haymarket’). The named impresario was the eccentric poet, cleric and former academic Christopher Smart, using his favourite pseudonym of ‘Mother [Mary] Midnight’. The Little Haymarket, not being one of the two licensed patent theatres (these were Covent Garden and Drury Lane), was not permitted to present spoken drama ‘neat’: there needed to be an admixture of other kinds of entertainment – principally music, which was variously supplemented by dancing, pantomime, comic orations, conjuring, acrobatics, novelty acts of any kind and even mock auctions.Footnote 9 In this instance, the result was something resembling a modern variety show.

On Smart's possibly abortive venture in 1752 there is little information, but the format of a medley concert was revived successfully at the same theatre in the second half of 1757 by the actor-manager Theophilus Cibber (son of the playwright and actor Colley Cibber). Cibber retained the character of ‘Mother Midnight’ and even introduced a ‘daughter’ for her, ‘Dorothy Midnight’, played by the eminent comic actor Samuel Foote. Bills and press advertisements for the early shows shed little light on the identity of the music performed (all of which seems, however, to have featured some kind of comic or novelty element), but a notice placed in the Public Advertiser for 11 August 1757 takes the form of a full programme for the evening's entertainment. This is transcribed below:

The presence in the programme of a ‘Comic Medley Overture’ deserves comment. The medley overture took the form of a piece introducing in succession various popular tunes generally familiar to the audience. It was a characteristically English and highly popular genre that had taken root during the 1730s in the wake of its prototype, Johann Christoph Pepusch's overture to The Beggar's Opera (1728). Notable contributors to the genre in its early phase were two brothers-in-law of Theophilus Cibber (Richard Charke, who died c.1738, and Thomas Arne), as well as Arne's brother-in-law John Frederick Lampe and Peter Prelleur.Footnote 10 In contrast, there was no parallel tradition of a ‘medley concerto’, a term that gained currency as a title only towards the end of the century. It is our belief that the ‘grand Concerto for French Horns’ performed earlier in the programme was the concerto based on three country dances that we have been discussing. (‘Grand’ is a standard reference to concerto grosso instrumentation with differentiated concertino and ripieno violin and cello parts, and the mention of horn parts also fits.) If we are right (and the circumstantial evidence all points in the same direction), the attribute ‘medley’ refers not only to the structure and thematic basis of the concerto itself but also to its customization for a medley concert that made a special feature of containing elements of a humorous or popular kind. The composer may indeed have intended the concerto's incorporation of country dances to be the aspect brought to the fore in the work's original title, but perhaps its alternative, and in the end more widely circulated, description as a ‘medley concerto’ was the one preferred by the vox populi.

The ‘grand Concerto for French Horns’ remained on the programme, to judge from the press notices, up to 5 September 1757. It then appears to have been dropped. The Medley Concerts themselves came to an end on 7 November,Footnote 11 just over a month before Cibber died (on 11 December 1757). An attempt was made to revive them after Christmas as the ‘New Medley Concerts’, but this initiative quickly fizzled out. It is probable that Johnson, following normal publishing practice, brought out the concerto in both its versions (ensemble and keyboard) while it still remained fresh in the public's mind, thus in late 1757 or 1758.

The identity of the composers of the pieces performed at Cibber's Medley Concerts, Handel excepted, is well hidden – very likely in order to safeguard the reputation of musicians for whom anonymity was the necessary price to pay for letting their hair down so brazenly in public. However, one only slightly later source appears to disclose the name of the author of the Medley Concerto. The last two entries for the letter ‘M’ in the manuscript catalogue of the Oxford Musical Society (compiled c.1770) are ‘Mudge's 6 Concertos. One of them for the Harpsichord or Organ’ and ‘Mudge's Medley Concerto, with Horns’.Footnote 12

Those who have more recently investigated Richard Mudge's life and music, in particular his most assiduous champion, Richard Platt (1928–2013), have always listed this concerto among his works, believing it to be lost. Assuming that we have now correctly identified the piece in question (as seems likely, since there is no hint that more than one concerto was similarly labelled at the time), we need to assess the strength of the evidence that Mudge was indeed its composer.

Richard Mudge and his music

English musical life of the mid-eighteenth century boasted a small number of active composers among the Anglican parish clergy, among whom Mudge (1718–63) was perhaps the most talented.Footnote 13 Born in Bideford in north Devon, he was the son of Zachariah Mudge (1694–1769), headmaster of the local free grammar school and later to become a well-regarded churchman (vicar of St Andrew's, Plymouth, from 1732 and prebendary of Exeter Cathedral from 1736). All of Zachariah's sons distinguished themselves. His homonymous eldest son (1714–53) became a surgeon and apothecary at Tiverton before taking to the seas as a naval doctor and ending his days in Canton (now Guangzhou, China). Thomas (1715–94), the second son, was a leading horologist who was appointed King's Watchmaker in 1776. John (1721–92), the youngest, practised as a surgeon and apothecary at Plymouth before moving over to the profession of general physician. Richard was the only one of the sons to attend university.Footnote 14 In 1734 he went up to Pembroke College, Oxford, obtaining his BA in 1738 and his MA in 1741.Footnote 15 Like so many other university students, he opted for a clerical career. He was ordained priest on 23 February 1743, but even before then, in 1741, he had obtained curacies at Little Packington and Great Packington near Birmingham, thanks to the patronage of the music-loving Lord Guernsey (Heneage Finch, later to become third Earl of Aylesford). Guernsey was a friend and relative of the librettist and musical connoisseur Charles Jennens, who lived at nearby Gopsall, and through these men Mudge gained access at least to the outer periphery of Handel's circle.Footnote 16 As a performer, Mudge distinguished himself mainly as a harpsichordist: Platt relates an anecdote from the historian of the Mudge family Stamford Raffles Flint, according to which Handel, entering a room in which Mudge was playing one of the great man's compositions, is supposed to have exclaimed, ‘That must be Mudge for no other man could play my pieces so.’Footnote 17 That this compliment was not merely ironic is suggested by a further alleged comment by Handel, not reported by Platt, that Mudge was ‘second only to himself’ as a harpsichordist.Footnote 18

In 1745, Mudge was elevated to the rectorate of Little Packington, a living he continued to hold until 1757; but the remoteness of his location was irksome to him, and in 1750 he sought and obtained a curacy at St Bartholomew's chapel of ease in Digbeth, Birmingham.Footnote 19 This brought him close to his friend John Pixell, who was vicar of the church of the same dedication in Edgbaston. Mudge gave up this curacy in 1758, having finally obtained, in 1756, a post in which he could see out his days in material comfort: as rector of Bedworth in Warwickshire, another living of which Lord Guernsey was patron.

Ever since Gerald Finzi discovered their virtues in the 1950s, the centrepiece of Mudge's reputation as a composer has always been the Six Concertos in Seven Parts […], To which is added, Non Nobis Domine, in 8 Parts, brought out by John Walsh in 1749. The concertos stand very much in the tradition of the similarly scored ones by Handel and Geminiani, except that the first adds a solo trumpet and the last a solo harpsichord. Critical reception was very favourable at the time, to judge from the number of surviving copies and the frequent appearance of the concertos in inventories and catalogues.Footnote 20 Modern reception, leaving aside the passionate advocacy of Finzi and Platt, has been more nuanced. Arthur Hutchings's influential study of the Baroque concerto reproached Mudge for conservatism, especially in comparison with his imitator Capel Bond, and for a certain lack of vitality.Footnote 21 But a very good recent recording of the set makes these reservations seem misplaced:Footnote 22 the works are revealed as sophisticated, well constructed and inventive, with touches of real power and originality.

At some point, probably after the composer's death, Guernsey, now Earl of Aylesford, appears to have come into possession of a large portion of Mudge's collection of music, including numerous autograph compositions and preparatory sketches. As a result of the dispersal of the Aylesford manuscripts following their auction in 1918, the known Mudge manuscripts are today divided between two locations: the Henry Watson Music Library in Manchester and the Gerald Coke Handel Collection at the Foundling Museum, London.Footnote 23 Most of the longer and more complete pieces are early or alternative versions of the Six Concertos and Non nobis, domine. Their chronology and interrelationship is extremely complex, to judge from the brief descriptions of individual items given by Platt. However, it does certainly appear that the manuscripts belong in the main to the pre-Birmingham period in Mudge's life, when he was active with music-making at Packington and Gopsall. There is no item among these manuscripts that obviously connects in any direct way with the Medley Concerto, although a violin part in Manchester for a ‘Sonata Cômposta a la gusto del Seign.or Bombardini’, related by material to the second published concerto, is of interest for revealing the same partiality for humour that informs the composition under discussion.Footnote 24

Before we proceed to a closer examination of the Medley Concerto, it is worth pausing for a moment to consider, in the light of Mudge's authenticated compositions, how supportive its general stylistic features are towards the hypothesis of his authorship. Leaving aside those portions of the first and fourth movements that are not merely based on dance material but also treat it in a manner close to the practices of traditional music (an absolute novelty in a concerto), it is fair to claim that the basic ingredients of Mudge's orchestral style as we know it from elsewhere – rich, often chromatic harmony; contrapuntal interest of a self-consciously ‘learned’ kind; robust but rarely ornate melody, with a generally simple (that is, pre-galant) rhythmic profile; a keyboard player's typical fondness for bass pedals with complex, shifting harmonies above – are abundantly present in this concerto. The idea of introducing familiar ‘popular’ material but flanking it with more orthodox material that subtly paraphrases it thematically, as seen in the first and fourth movements of the Medley Concerto, is strikingly prefigured in Mudge's Non nobis, domine setting. In that work, the first 86 bars are all ‘prelude’, adumbrating the canon with rising and falling scale-based figures, before the canon itself finally makes its triumphant appearance in bar 87, continuing (with optional ‘circular’ repeats) up to the notated bar 109.Footnote 25 The climactic effect reminds one of the long-delayed arrival of Gaudeamus igitur in Brahms's Academic Festival Overture.Footnote 26

But oddly enough the strongest argument in favour of Mudge's authorship of the Medley Concerto is not stylistic but notational. A preliminary explanation is required. Leaving aside the special case of repeated notes, eighteenth-century notation follows the general principle that chromatic inflections indicated by an accidental automatically lapse (without the need for any cancelling accidental) after the move to a new beat. Nineteenth-century and subsequent notation places the point of ‘automatic lapse’ after the barline following the original accidental. Naturally, both old and new systems allow the use of precautionary accidentals to make the cancellation more explicit, but the general principle is that the greater the distance from the original accidental, the less the need for a precautionary, cancelling one.

In Mudge's autograph score of the Six Concertos,Footnote 27 Walsh's print of the same works and Johnson's two editions of the Medley Concerto we find the same, almost pedantic idiosyncrasy: an insistence on cancelling all chromatic inflections with a new accidental, regardless of context or of the distance from the original accidental. Some instances are shown as Example 1 (all accidentals are given as in the source: ‘remote’ precautionary accidentals are indicated by an asterisk). To anyone familiar with mid-eighteenth-century notation, this compulsive insertion of unnecessary cancelling accidentals has the appearance of a private, self-imposed rule.Footnote 28 If Mudge shared it with someone else, that person remains to be identified, but even if not unique to Mudge, this strikingly similar use of precautionary accidentals in the Medley Concerto and Mudge's concertos is unusual enough to hint strongly at common authorship.

Example 1. (a) Medley Concerto, movement II, violino primo concertino, bars 4–6; (b) Medley Concerto, movement II, violino secondo concertino, bars 53–5; (c) Concerto I (1749), movement I, violino primo concertino, bars 43–6; (d) Concerto VI (1749), movement II, violoncello, bars 4–8. © British Library Board, h.1568.f.(1.).

The Medley Concerto described

The scoring of the Medley Concerto for seven-part strings (including the continuo part) and two French horns is absolutely typical for its time and place. Francesco Geminiani's edition (1726) of his arrangements of the first six of Arcangelo Corelli's op. 5 violin sonatas, followed soon afterwards by his own opp. 2 and 3 (1732), inaugurated a fashion – one should rather describe it as a standard layout – for the provision of ripieno in addition to concertino violin parts plus a separate cello part that could, if desired, emancipate itself from, or play without the support of, the continuo bass. The distinction between concertino and ripieno, inherited from the Roman tradition exemplified by Corelli, was particularly suited to British conditions, where professional musicians so often played alongside amateurs. Long after the seven-part concerto grosso layout had been abandoned on the Continent (Pietro Antonio Locatelli's op. 4 of 1736 is the last example to spring to mind), it remained the norm in Britain. As late as 1785 it was still being used by Charles Wesley. The great virtue of the seven-part format was that it provided a catch-all receptacle for orchestral string music: it could accommodate equally well solo violin concertos, concertos for two violins and (as in Handel's op. 6 no. 7) ripieno concertos without soloist.Footnote 29 It was also well suited to chamber-style performance (one instrument to a part), since the omission of either or both of the ripieno violins and sometimes even of the viola could often be undertaken without noticeably damaging the music.

The addition of two French horns to this ensemble had become by the 1750s a popular, albeit not indispensable, feature of British orchestral writing for ‘public’ venues such as theatres, pleasure gardens and concert halls. Restricting our remarks to the concerto genre (horns had appeared slightly earlier in overtures), we find mention of concertos including them as early as 1723 (Handel's ‘New Concerto for the French Horns’, HWV 331, and a ‘Grand Concerto’ by Vivaldi with oboes and horns performed at the New Theatre in the Haymarket).Footnote 30 There then appears to be a short lull in the appearance of horns in concertos, but the momentum picks up again in 1740 with the publication of Johann Adolph Hasse's op. 4 concertos (actually a collection of six two- or three-movement overtures written in a concerto-like manner). Francesco Barsanti uses a pair of horns in five of his op. 3 Concerti grossi (1742); Handel includes horns in his Concerto a due cori, HWV 333 (1748); and by the 1750s concertos ‘with’ or ‘for’ French horns are all the rage: the near-interchangeability of the two prepositions in titles expresses the great variability of the instruments’ treatment, which ranges from the ostentatiously concertante to the modestly accompanimental. The ambitious and taxing horn parts in the Medley Concerto constitute a veritable recipe book of the many possibilities: indeed, the slipping in and out of melodic prominence by the two horns is a major contributor to the work's musical vitality. As he had done earlier in the concerto with trumpet which heads his Six Concertos, Mudge shows great skill in his handling of the natural brass instruments, turning their limited choice of available notes into an asset feeding his imagination.Footnote 31

In the Medley Concerto, as in his other published concertos, Mudge employs the standard four-movement plan (Slow–Fast–Slow–Fast) taken over, like the seven-part string scoring layout, from the Roman concerto tradition as exemplified by Corelli and popularized in Britain by Geminiani, which in its turn went back to sonata models of the late seventeenth century. Likewise inherited from this tradition is the concentration of the contrapuntal and structural heft in the first of the two quick movements (II) and the use of the internal slow movement (III) for tonal and modal contrast.

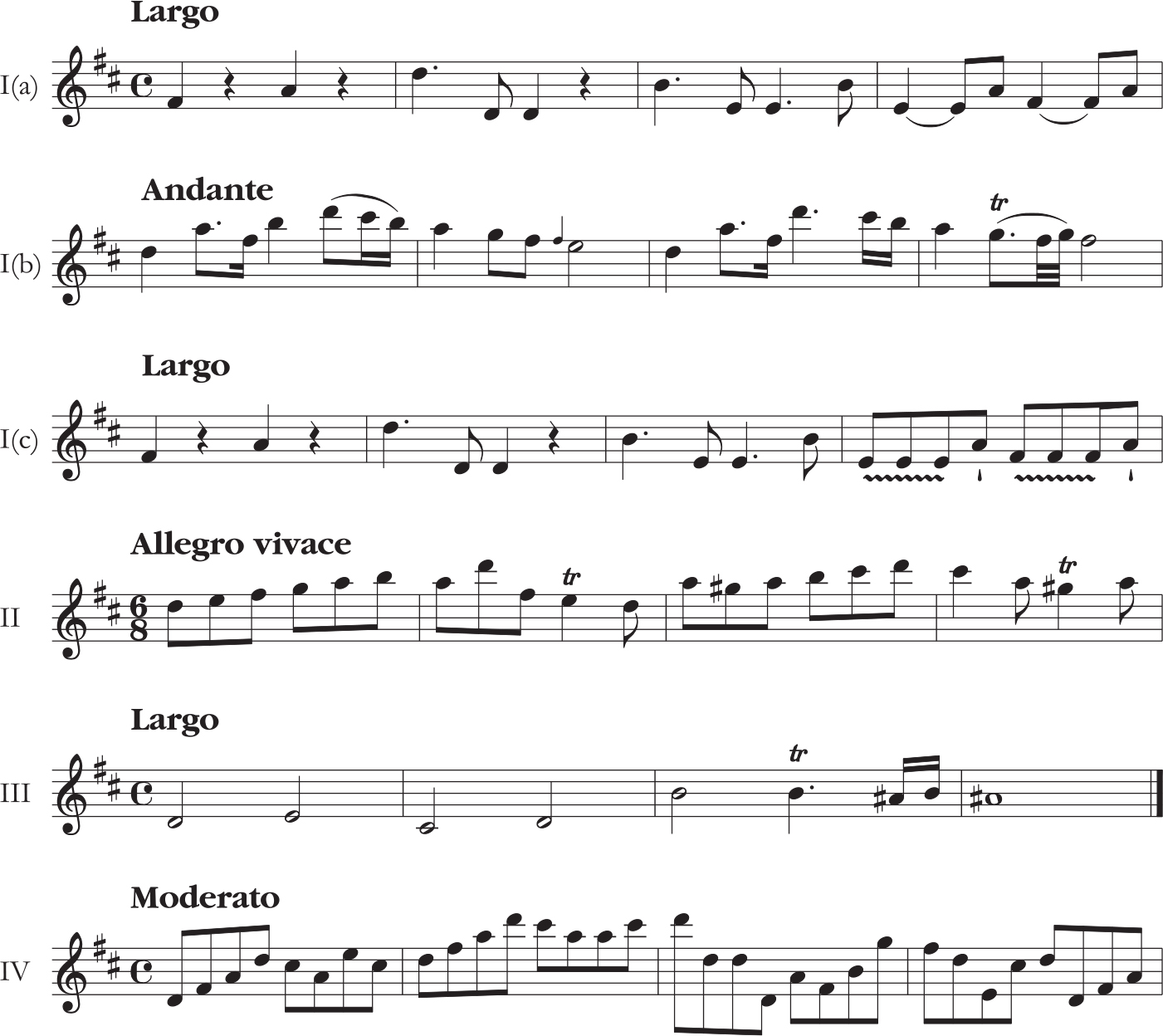

In schematic outline, the four movements, of which the incipits (all taken from the violino primo concertino part) appear as Example 2, are as follows:

I D major, Largo–Andante–Largo, C, 40 (6 + 28 + 6) bars, ending on V

II D major, Allegro vivace, 6/8, 107 bars

III B minor, Largo, C, 4 bars, ending on V (Phrygian cadence)

IV D major, Moderato, C, 92 bars.

The design and character of each movement will now be described.

Example 2. Medley Concerto, movement incipits (with sectional incipits for movement I). © British Library Board, h.1568.f.(1.).

Movement I

This movement employs the popular device of a frame enclosing the main, essentially lyrical, section.Footnote 32 This six-bar frame, which is virtually identical on its two appearances (Mudge slightly elaborates the fourth and fifth bar the second time) has a conventionally dramatic character, opening with breathless chords separated by rests. The emphatic imperfect cadence with which it ends serves the first time to introduce the main section, the second time to introduce the next movement. No inkling of the ‘country dance’ nature of the principal material is given.Footnote 33

The main section, making up bars 7–34, comprises seven consecutive statements of the four-bar Scottish dance tune best known today from its later use as an American revolutionary song by the name of ‘Roxbury Reel’ (its provenance and history will be discussed in the next section). For each statement, Mudge adopts a technique of variation characteristic of traditional music rather than art music: instead of fixing the identity of each variation by constructing it around a distinctive and consistently maintained ‘idea’ (rhythmic, figurational, textural, harmonic and so on), he allows the variations to evolve through free paraphrase around the more or less fixed harmonic scheme based on primary triads. Statements 1, 4 and 7, in which the melody is carried by the first violins, coax it into different patterns that one could almost encounter in an ordinary concerto Andante, complete with appoggiaturas and trills (although the naive symmetry of the phrase structure is a little at odds with the melodic polish); the two pairs of statements (2–3 and 5–6) where the first horn has the melody present it in a more traditional guise, albeit each time with small, playful alterations (and matching variations in the accompanying parts). Example 3 shows the initial entry of the horns.

Example 3. Medley Concerto, movement I, bars 11–14 (bass figures omitted). © British Library Board, h.1568.f.(1.).

Movement II

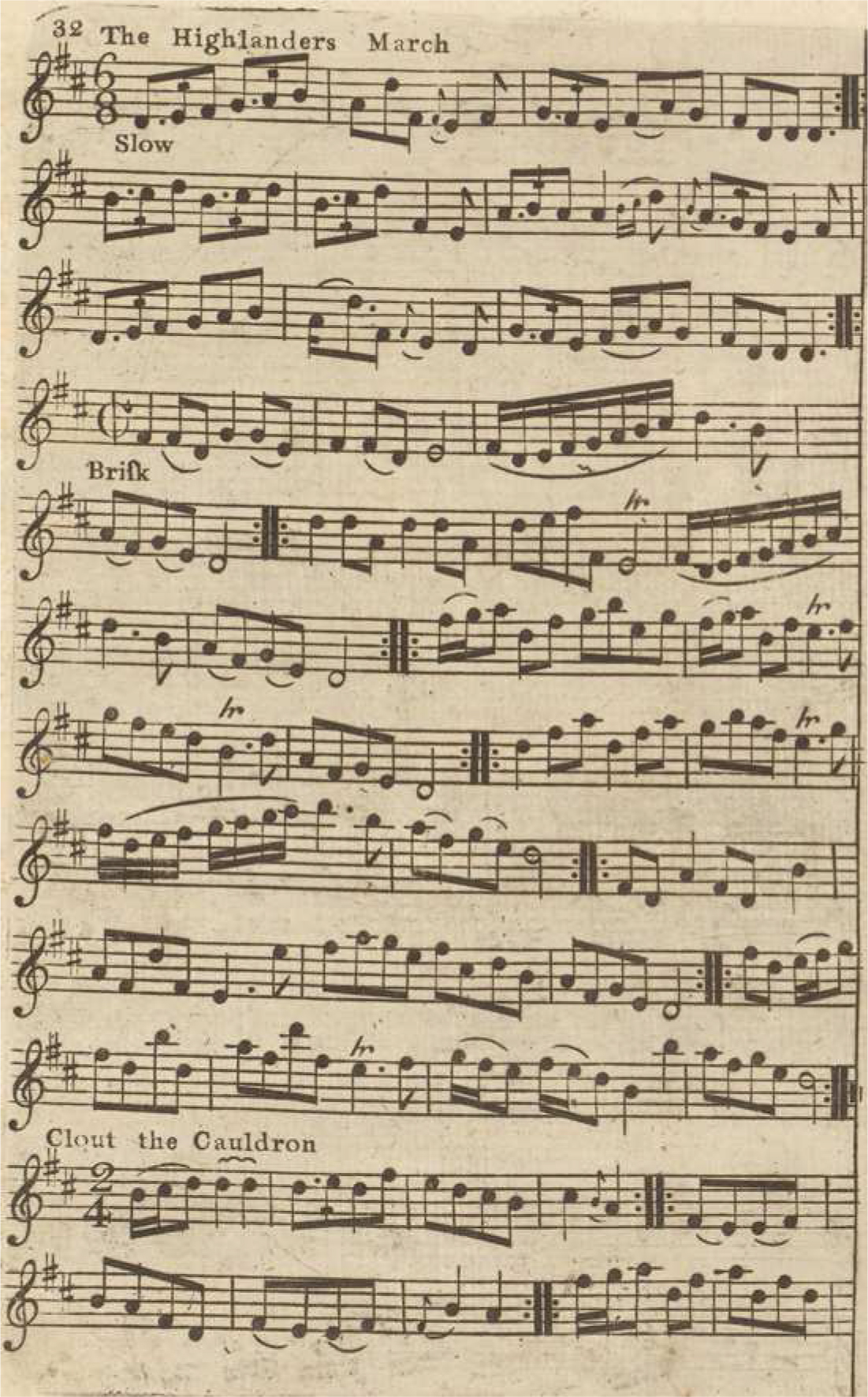

This is a complex and fairly lengthy fugue that utilizes practically the entirety of a Scottish traditional melody in the course of its fugal expositions, intervening episodes and final peroration.Footnote 34 The melody is given as Example 4 in the version that Mudge is most likely to have used. Entitled ‘The Highlanders’ March’, the tune appears in a monophonic setting (for flute or violin) in book 7 of James Oswald's multi-volume collection The Caledonian Pocket Companion (hereafter CPC).Footnote 35 Cast in rounded binary form with twin repeats (A:BA:), it comprises six segments, identified in Example 4 as A–D, followed by AA and BB (the segments with duplicated letters are variants belonging to the ‘free paraphrase’ type mentioned above). To the student of fugue and the devotee of thematic economy alike, this movement is an impressive compositional achievement in which erudition and humour support and actually intensify each other.

Example 4. ‘The Highlanders’ March’ (The Caledonian Pocket Companion, vol. ii, book 7 (London: James Oswald, c.1756), 32). National Library of Scotland, Ing.86.(7).

The first exposition occupies bars 1–18. The subject, identical to segment A (except for the evening out of the dotted rhythm), is presented successively in D (violin 1, bar 1), A (violin 2, bar 3), D (united basses, bar 5), A (viola, bar 11) and D (horns, bar 17).Footnote 36 There is no regular countersubject, but Mudge uses the codettas between the last three entries to quote material from segments B, C, D (in both plain and elaborated form) and BB.

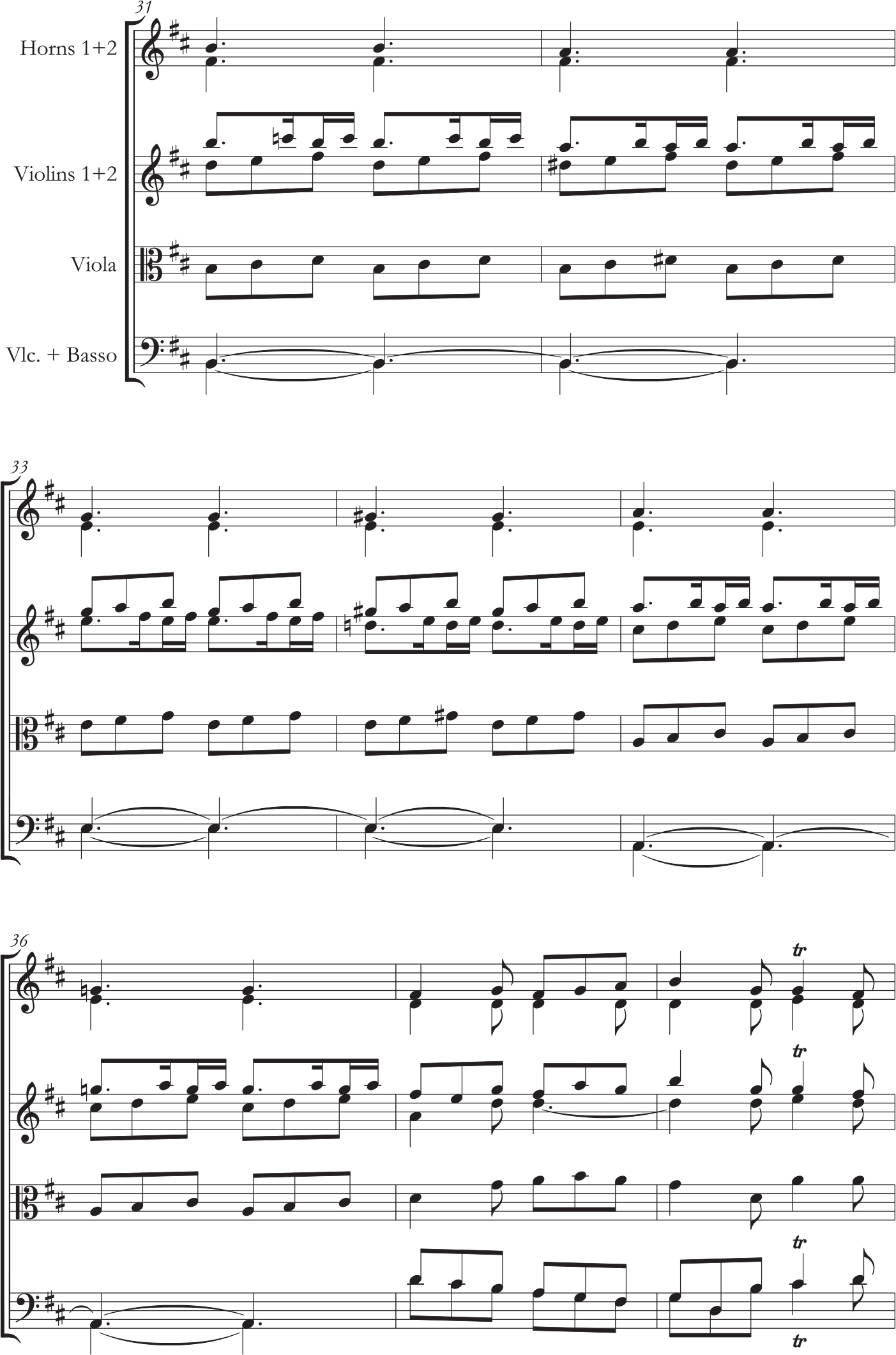

The first episode, comprising bars 19–28, travels via E minor to B minor, utilizing material from the same five segments in repetition, juxtaposition and contrapuntal combination. Bars 29–30, a single entry of a truncated and freely continued version of the subject in the bass, bring the period to a close. Immediately, a complementary second episode (bars 31–6) takes over, returning the music to D major. This develops the material of segments C and D intensively. Once again, an isolated entry of the subject in the bass – this time in complete, but cunningly inverted, form – underpins the close of the period in bars 37–8. Bars 31–8 are shown as Example 5.

Example 5. Medley Concerto, movement II, bars 31–8 (bass figures omitted). © British Library Board, h.1568.f.(1.).

The third episode (bars 39–44) is a brief interlude in lightened texture (horns and ripieno violins drop out) based entirely on sequential reiteration of segment C. Bars 45–8 are a canonic restatement of the subject in D major, proposed in successive bars (thus in stretto) by violin 1, violin 2 and united basses, with viola doubling the last two entries. Bars 49–52 bring the fourth episode, based on segments C and D, which is rounded off in bars 53–4 by another ‘altered’ entry of the subject in the bass, this time cadencing in F♯ minor. The complementary fifth episode returning the music to D major (bars 55–8), which has the character of a retransition, is based mainly on the first bar of segment BB. It, too, is rounded off by a single statement of the subject – this time, unexpectedly, on unaccompanied unison violins, as if in the manner of traditional fiddlers. The longer sixth episode (bars 59–74) begins by intensively repeating the second bar of the subject sequentially, before coming to rest, in bar 67, on a bass pedal, over which versions of the first bar of segment BB are repetitively hammered out.

Bars 75–80 are a new exposition with three entries (violin 1 in A; unison violins in D; united basses in D). This exposition is orthodox in employing the cherished device of rovescio (‘reversal’: the announcement of the subject in its ‘answer’ form before it is restated at the original pitch), but less so in once again making both entries monophonic (the bass entry, however, is accompanied by the full ensemble). Bars 81–107 constitute what we have termed the final peroration, in which all the segments of the original tune are at some point revisited. In bars 80–1 the horns blast out a monotone in alternation, hunting-style. Bars 87–9 give the concertino violins a touch of arpeggiated bravura in accompaniment to motivic play in the other parts. From bar 94 onwards Mudge reintroduces the characteristic motif of a ‘drooping’ third (as found in the second bar of segments B and BB), which has been strangely – but, in the event, certainly not accidentally – absent since bar 8. With extended forms of this exuberant material, the whooping horns, abetted by their partners, bring this movement to a not exactly fugal close.

There is a close precedent for this type of movement in three of the Nove overture a quattro, op. 4, published privately by subscription in London around 1750 by Barsanti, who had settled in Britain in the early 1720s. The fugal sections of the initial movements of Barsanti's first, sixth and ninth overtures all have subjects based on popular melodies; that of the ninth overture is in fact a country dance known in Scotland as ‘Babbity Bowster’ (and various other names besides), although Barsanti captions it with its English name of ‘Country Bumpkin’. Mudge was not among the subscribers to Barsanti's collection, but he could very well have known it and set out to imitate the half-learned, half-jocular character of its fugal writing.Footnote 37

Movement III

The most familiar suitable comparator for this movement is the two-chord central movement of Bach's Third Brandenburg Concerto. Its sole function is to act as a parenthesis between the two faster movements, clearing the air with a switch to the relative minor key and a few seconds of slow tempo. Even under these limitations, Mudge shows a touch of class with his expressive rising major sixth (see above, Example 2), which restores the first violin to its natural position as the highest voice.

Movement IV

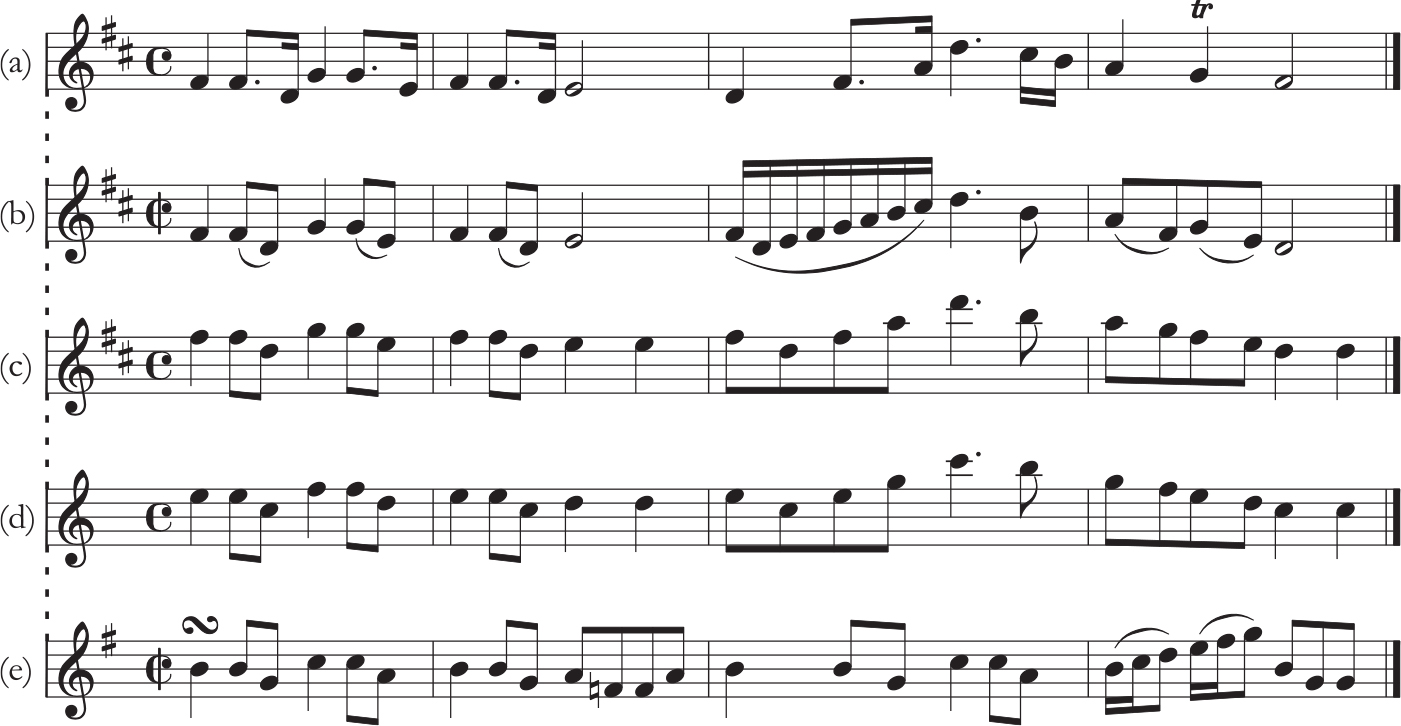

As the basis of his final movement Mudge chose the tune opening the sixth book of CPC, entitled there ‘The Old Highland Laddie’ (‘old’ referring to the tune rather than to the laddie!).Footnote 38 Like the ‘Roxbury Reel’, it comprises 12 bars in rounded binary form (A:BA:), each component having four bars. Oswald's starting version of the tune is already fairly ornate; Mudge's starting version (occupying bars 5–28, the repeats being fully written out) is by comparison rather skeletal. Whether this was a deliberate compositional modification or arose simply from the fact that Mudge quoted the tune by ear or from a different written source is not possible to say.Footnote 39 The two versions are compared in Example 6.

Example 6. ‘The Old Highland Laddie’, bars 1–12 (The Caledonian Pocket Companion, vol. i, book 6 (London: James Oswald, c.1755), 1, transposed from G major to D major; National Library of Scotland, Ing.68(6)), compared with Mudge, Medley Concerto, movement IV, horn 1, bars 5–28 (notated with the use of repeat signs; © British Library Board, h.1568.f.(1.)).

The form of the movement is articulated in six sections as follows:

bars 1– 4: introduction loosely paraphrasing bars 1–4 of the tune; melody on unison violins.

bars 5–28: statement 1 of the tune; melody on horn 1.

bars 29–36: episode 1, scored for unaccompanied concertino violins; modulates from B minor to F♯ minor.

bars 37– 60: statement 2 of the tune; melody as before on horn 1, but this time with elaborate and varied figurations on horn 2 and the accompanying strings (introducing some semiquaver motion and double-stopping). The tension is ratcheted up further by use of a ‘drum’ bass.

bars 61–8: episode 2, scored for concertino violins and cello; in B minor, cadencing on the dominant.

bars 69–92: statement 3 of the tune; melody on violin 1, with assorted concertante figurations in the upper and middle parts.

The insertion of episodes resembling the couplets of French-style rondos is a feature very popular in the British music of the time, not excepting movements otherwise very Italianate in style. Here, their role is to offer tonal and textural contrast between the successive statements of the tune.Footnote 40 What the tabulation above does not show is the considerable amount of ‘microvariation’ between sections and their immediate repetitions: Mudge truly enters into the spirit of traditional music, seeking ever new inflections of the original melody and its accompaniment.

The Medley Concerto resists easy categorization: quite simply, it is sui generis. But it is important to view it not merely through the lens of the concerto but also in the context of the dances and their melodies that make up most of its raw material. To this subject we now turn.

The three country dances

The challenge of identifying the melodies chosen by Mudge as the basis for the Medley Concerto was lessened considerably by Charles Gore's Scottish Fiddle Music Index. That work lists the titles and ‘tune codes’ (numerical sequences derived from the on-beat pitches of the opening two bars) of tunes from printed collections of Scottish dance music published from 1700 to 1900.Footnote 41 ‘The Old Highland Laddie’ and ‘The Highlanders’ March’ were easily identifiable on the strength of their tune codes and located to books 6 and 7 respectively of CPC.Footnote 42 CPC is the only known source for the latter tune, but the former is found in many later sources, and remains in the repertoire of Scottish dance-band musicians to this day under the new title of ‘Kate Dalrymple’. In the nineteenth century, a tune of the same name (‘The Old Highland Laddie’) was among those set by Haydn in a commission from the Scottish music publisher George Thomson, and Ferdinand Ries chose it as his theme for an air with variations for piano.Footnote 43 However, this is different from the tune included by Mudge. Thomas Arne composed a setting of ‘The [New] Highland Laddie’ that was published as a broadside in the same period, but its melody bears no similarity to that of ‘The Old Highland Laddie’.Footnote 44

The tune we are referring to as ‘Roxbury Reel’ proved more problematic to identify, its ‘tune code’ most closely resembling a tune called ‘Ambelree’ that was first published well after Mudge composed the concerto.Footnote 45 However, an examination of book 7 of CPC revealed the tune, seemingly untitled but marked ‘Brisk’, on the same page as and immediately following ‘The Highlanders’ March’ (which is marked ‘Slow’), and followed by five variations (see Figure 1, where the contiguous repeat marks between the slow and brisk sections imply a single, multi-sectioned tune rather than two autonomous tunes). John Purser claims that the melody of the slow section is an adaptation of ‘A Rock and a wi Pickle Tow’ from book 1 of CPC, with the brisk section a set of ‘three variations in reel time’.Footnote 46 Example 7 highlights the commonalities between ‘The Highlanders’ March (Slow)’ and the ‘Gig’ variation from ‘A Rock and a wi Pickle Tow’. Alternatively, it is possible that the brisk section was intended as an autonomous tune, its title omitted in error. This would better explain its inclusion in Mudge's concerto, as his decision to base separate movements on two sections of a tune seems incongruous. However, the connective repeat marks and commonality of key strongly support its interpretation as a single, multi-sectional tune. Further, Oswald went on to publish a larger-scale multi-section work in book 9, ‘A Highland Battle’, for which ‘The Highlanders’ March’ may have been a prototype.Footnote 47

Figure 1. ‘The Highlanders’ March’ (The Caledonian Pocket Companion, vol. ii, book 7 (London: James Oswald, c.1756), 32). National Library of Scotland, Ing.68(7). Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Example 7. (a) ‘A Rock and a wi Pickle Tow (Gig)’ (The Caledonian Pocket Companion, vol. i, book 1 (London: James Oswald, c.1745), 8); National Library of Scotland, Ing.68(1). (b) ‘The Highlanders’ March (Slow)’ (ibid., vol. ii, book 7 (London: James Oswald, c.1756), 32), transposed from D major to G major; National Library of Scotland, Ing.68(7).

The similarity between ‘The Highlanders’ March (Brisk)’ and ‘Ambelree’ is unlikely to be coincidental, the collector of the latter tune, Nathaniel Gow, probably having ‘borrowed’ the seemingly untitled tune from CPC and updated it to suit the preferences of his early nineteenth-century market.Footnote 48 ‘Roxbury Reel’ was identified via a RISM incipit search, its opening bars bearing a strong resemblance to the ‘brisk’ section of ‘The Highlanders’ March’. The tune was published under the latter title in The Fifer's Companion (1805), and it is included in William A. Brown's untitled manuscript book for clarinet (c.1840) together with other traditional melodies and rudimentary pedagogical material.Footnote 49 As is common in the transmission of traditional music, the tune was renamed when exported to North America, Roxbury being a former municipality of Boston, Massachusetts, and a place of strategic significance in the Siege of Boston, which marked the start of the War of American Independence.

The four settings of the tune thus identified are given alongside Mudge's setting in Example 8. Oswald's setting (Example 8b) was probably Mudge's source of the melody, no earlier or contemporaneous setting having been found. Mudge's adaptation reflects both his stylistic preference (the dotted rhythms and Andante marking) and the need for instrumentally idiomatic figurations (the slurred semiquavers in CPC bar 3, which are idiomatic for performance on the flute, are adapted to suit the natural horn). The f ♮′s in bar 2 of Gow's setting of ‘Ambelree’ (Example 8e) highlight a potential ‘Scoticism’ of the tune not exploited by Mudge, which is described rather imperfectly by Francis Collinson as the double tonic.Footnote 50 The term refers to the perceived harmonic basis of many traditional Scottish melodies that consists of an alternation between chords I and ♭VII. Taking the Oswald setting as our example, the minim e′ in bar 2 could be taken to imply a double tonic rather than dominant harmony (in this case, a chord of C rather than A).Footnote 51 ‘Roxbury Reel’ (Examples 8c and d), while clearly belonging to the same tune family as Oswald's setting, was either copied from an unidentified (later) source or transcribed from performance.Footnote 52

Example 8. (a) Medley Concerto, movement I, bars 11–14 (horn I); © British Library Board, h.1568.f.(1.). (b) ‘The Highlanders’ March (Brisk)’, bars 1–4 (The Caledonian Pocket Companion, vol. ii, book 7 (London: James Oswald, c.1756), 32); National Library of Scotland, Ing.68(7). (c) ‘Roxbury Reel’, bars 1–4 (The Fifer's Companion No 1, ed. Joshua Cushing (Salem: Cushing & Appleton, 1805), 21); original time signature 2/4, note values doubled. (d) ‘Roxbury Reel’, bars 1–4 (William A. Brown, [Marches, Dance Music, Duets in Treble Clef. Includes ‘A Plain Scale for the Clarionette’, ‘Scale of Flats and Sharps’. Inscribed ‘William A. Brown’], Peabody and Essex Museums, James Duncan Phillips Library (US-SA), MSS 475, box 4, folder 5, fol. 7v); original time signature 2/4, note values doubled. (e) ‘Ambelree’, bars 1–4 (Part Third of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys, and Dances (Edinburgh: Gow & Shepherd, c.1806), 18; opening quaver anacrusis omitted); Brigham Young University Library, M0525.

Interestingly, Mudge's source seems most likely to have been books 6 and 7 of CPC, which Purser dates to c.1755 and c.1756 respectively.Footnote 53 The designation of the melodies as ‘three country dances’ implies that each had an accompanying choreography, but none has been identified. Mudge's choice of ‘The Highlanders’ March (Slow)’ which, unlike the other melodies, is not a dance tune, suggests that the term may have been used loosely for marketing purposes and to imply a general repertory rather than anything more specific. Both ‘The Old Highland Laddie’ and ‘The Highlanders’ March (Brisk)’ are reels, as is reflected in their shared tempo marking, but their presentation in a series such as CPC is more indicative of domestic performance as chamber music by amateur music-makers than of performance by professional dance-band musicians at an assembly.Footnote 54

Scottish traditional music in London

London was an attractive destination to musicians from throughout Europe and the British Isles in the eighteenth century, and Scottish musicians were no exception. Scottish song and dance music were already familiar to many Londoners from the performances of servants attached to noble Scottish households that were in town to attend court, and from publications such as The English Dancing Master and A Collection of Original Scots Tunes, (Full of the Highland Humours).Footnote 55 However, the emergence of new fashions and performance contexts in the course of the eighteenth century raised the status of Scottish music and musicians. By mid-century, ‘Scotch song’ was a regular entertainment on the theatre stage, and Walsh's series Caledonian Country Dances exemplifies the enthusiasm for Scottish country dances in the capital throughout the period.Footnote 56 However, as George Emmerson writes of the choreography at the time:

It is likely that a number of the dances emanated from Scotland, but it is not possible to distinguish these from the English dances except, perhaps, where they contain the figures reel of three at the sides and set to and turn corners, figures which became popular in Scotland.Footnote 57

The same was true of the music, with many of the melodies newly composed to satisfy demand. Writing in 1822 or 1823, Thomson gave an account of earlier practices among English composers that Claire Nelson interprets as distinguishing between a non-original ‘Scottish style’ and a native ‘Scottish character’:

A short time before the publication of the Tea-Table Miscellany, it had become very much the fashion in London to write and compose songs and tunes in the Scottish style, for the theatres and public gardens. Some of these were adopted by Ramsay; and, by this means, have obtained a place among our popular airs, though they possess very little of the Scottish character. The composers of those airs, from Dr Green down to Dr Arne, seem to have adopted a kind of conventional style, which they chose to call Scottish; and a good many of their airs having found their way into Scotland, have become naturalized among us.Footnote 58 Indeed, Roger Fiske highlights how lyrics were often more important than the music in defining the style of a ‘Scotch song’.Footnote 59

The Jacobite campaign of 1745–6 stimulated a renewed interest in Scottish music, with Highland culture perceived as ‘exotic’ once the threat posed by Prince Charles Edward Stuart had been neutralized. The vogue achieved its most infamous manifestation in James Macpherson's Ossianic poetry from around 1760, but Oswald had been publishing music since about 1745 that propagated a ‘Highland’ topos. Tunes with ‘Highland’ titles pervade the 12 books of his CPC (the series from which Mudge selected the melodies for his Medley Concerto), where Scottish-cum-Highland musical features (such as the implication of a ‘double-tonic’ tonality, pentatonicism and the rhythmic profile of a Scottish dance type) were also widely used. Indeed, Mary Anne Alburger notes that the series is a collection of ‘traditional Scottish and Scottish Gaelic music’, Highland culture being synonymous with Gaelic culture at this time.Footnote 60 Of particular interest are the variation sets composed by Oswald to many popular tunes, in addition to melodies of his own composition (identifiable as those marked by a cross on the original contents pages).

Oswald was one of several Scottish musicians active in London in the eighteenth century, and had the biggest impact on the popularization of Scottish music there.Footnote 61 He was born in Crail on the East Neuk of Fife, and was a dancing-master in the area before moving to Edinburgh by 1736, where his earliest compositions were published. He moved to London in 1741, and by 1747 had established a music-publishing firm at St Martin's Church Yard in the Strand.Footnote 62 Notable among his compositions are two sets of 48 sonatas in which each sonata is named after a flower, a shrub or a tree, and they are grouped according to the seasons.Footnote 63

Oswald's reception in the twentieth century has been made problematic by the seemingly incongruous combination of ‘classical’ and ‘folk’ works in his oeuvre. Modern attitudes towards music categorization are marked by a stark divide between the two, but, as Matthew Gelbart explains, ideas about musical categorization were different in the eighteenth century:

Back before the folk–art split, a composer such as Oswald could straddle Scottish and international styles without worrying about being a ‘folk composer’ or an ‘art composer’, he was just a composer […] but by the time the Scottish Fiddler Niel Gow (1727–1807) was flourishing, to be a great Scottish musician meant to be a great ‘folk’ musician.Footnote 64

In a similar vein, David Johnson discusses the ‘cross currents’ in Scottish music at this time, namely those between art music and folk music, whether in the setting of traditional dance melodies as chamber music with ‘tasteful’ ornamentation, or in the composition of chamber music with identifiably Scottish musical characteristics.Footnote 65 However, this frame of reference is made problematic by the historical contingency of these musical categories, with ideas about folk music and art music emerging only in the course of the eighteenth century and not becoming established in common use until late in the nineteenth century. As Gelbart explains, music was more readily categorized according to its function in the eighteenth century – as dance music or concert music, for instance.Footnote 66 Thus the identification of traditional music at this time is complicated by modern attitudes that place significantly more value on authorship and recognize a sharp divide between ‘folk music’ and ‘art music’. Oswald's duality as a composer of chamber music and ‘traditional’ variations on popular dance tunes therefore seems incongruous.

Viewing Mudge's Medley Concerto in this context, his choice of Scottish themes followed the precedent set by Geminiani in his arrangements of Scots songs in his Treatise of Good Taste in the Art of Musick.Footnote 67 More than two decades later, J. C. Bach also derived inspiration from Scottish tunes, for example in his use of the popular Scottish air ‘The Yellow Hair'd Laddie’ for a theme and variations finale to his keyboard concerto op. 13 no. 4 in 1777. What had begun as a trickle in the second half of the eighteenth century was to become a flood in the nineteenth century, when Scottish (or other ‘national’) melodies sometimes came to permeate the entire substance of a potpourri-like composition. This occurs with high artistic effect in Ignaz Moscheles's Anticipations of Scotland, op. 75 (1828), for piano and orchestra and Max Bruch's better-known Scottish Fantasy, op. 46 (1880), for violin and orchestra. As in Mudge's prototype (as one might term it), the favoured structural vehicle always remains variation form, with occasional ventures into fugal texture. Constant Lambert's strident insistence on an ‘obvious technical conflict between the folk song and classical form’ was unquestionably a considerable overstatement,Footnote 68 but it does correctly recognize that orthodox developmental processes, such as are inherent in sonata form, often sound forced when applied to folk material. In contrast, variation form, which is at root only a sophisticated type of strophic form, is common to traditional music and art music and therefore an ideal bridge between them. In all the quoted instances, the melodies, popularized through song or dance, were abstracted from their original performance context and arranged to suit contemporary tastes and fashions in the sure knowledge that they would appeal to the public.

Conclusion

Mudge's Medley Concerto is a historically significant work in the canon of British compositions from the eighteenth century, being unique in form for its time and demonstrating the composer's ability in the concerto grosso genre. Indeed, the attribution to Mudge contributes an important new work to his small oeuvre, placing on show his assured writing for horns and successfully taking over modalities of melodic variation more closely associated today with traditional music.

Even if Mudge's Medley Concerto has more the character of an ephemeral novelty than that of a work conceived by its creator as pioneering in the sense of inviting successors, it nevertheless deserves to be seen as a straw in the wind. One might have imagined that the eighteenth century, with its rigid social hierarchies and extreme inequalities, would have been unsympathetic to the idea of joining art music to folk music, but the reverse turned out to be the case. Crucial was the fact that in British urban and rural society as a whole the different social classes lived in close proximity to one another, servants next to masters and tenants next to landlords, making inevitable the mingling of ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures within the everyday soundscape. Moreover, in a period, the 1750s, when national cohesion in the face of foreign threats (or in support of fresh imperial adventures) was universally sensed as a necessity, an overt cultural gesture towards the populace at large, and especially towards the ‘North Britons’, not long since welcomed into the fold (as southerners would see it) and not yet fully integrated politically, would be more likely than ever to win approval among the London theatre-goers or members of music clubs who first heard this concerto. In this respect, the Medley Concerto goes beyond its genre and function to throw a revealing spotlight on its time and place.