Introduction

On the night of 13–14 February 1945, the British and American air forces dropped nearly 4,000 tons of ammunition on Dresden. Their target was a city in the eastern reaches of Germany, known since the 1700s on account of its Baroque skyline and cultural riches – including world-famous musical institutions such as the Dresdner Kreuzchor (the choir of the Church of the Holy Cross in Dresden), the Semper Opera and the Dresden Philharmonic – as ‘Florence on the Elbe’. The Royal Air Force's two-round bombing strategy left some parts of the city completely destroyed and between 18,000 and 25,000 people dead (estimates varied throughout the post-war years).Footnote 1 The most concentrated damage occurred in the city's historical centre, the Baroque Altstadt, where 80–90 per cent of the buildings were damaged.Footnote 2 The local photographer Richard Peter captured the desecrated Altstadt in his now-famous photographs taken in autumn 1945, later published as a largely wordless photobook provocatively entitled Dresden: Eine Kamera klagt an (Dresden: A Camera Accuses, first printed in 1949). Sparsely captioned and largely devoid of human life, these images not only conveyed the extent of the destruction but also transformed the city into an icon for German suffering in the Second World War (see Figure 1).Footnote 3

Figure 1. Photograph of the Altstadt (sometimes given the title ‘An Angel over Dresden’) taken by Dresden-based photographer Richard Peter in September 1945 and published in the photo-essay Dresden: Eine Kamera klagt an (Dresden: Dresdener Verlagsgesellschaft, 1949), 5. Reproduced by kind permission of the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden.

The aerial bombing of urban centres was a strategy used by both sides in the war. Between 1939 and 1945, an estimated 600,000 civilians – approximately 465,000 of whom were Germans – died in bombing campaigns that targeted hundreds of European cities and towns.Footnote 4 Twenty-five cities across the German Reich were bombed, some repeatedly, as part of an Allied effort to cripple civilian morale as much as military infrastructure.Footnote 5 Even with this nationwide knowledge of the air war, the attack on Dresden still took Germans by surprise. Many of the city's residents mistakenly believed that the Saxon capital would not be targeted, and this view was widespread throughout the country.Footnote 6 The bombing seemed pernicious to foreign observers as well. It took place at a time when Allied victory looked increasingly certain: the Yalta conference, where Allied leaders had met to discuss plans for the division of Europe, concluded days earlier, on 11 February; and the Wehrmacht (the armed forces in Nazi Germany) would surrender less than three months later, on 8 May 1945. The intensity and timing of the attack led to immediate accusations from the Nazis that the Dresden firebombing was a barbaric attack on a city of civilian victims.Footnote 7

Dresden's cityscape and citizens were drastically reshaped by the devastating effects of this late wartime bombing. Music played a significant role in the city's post-traumatic refashioning, which began in the early post-war months and continues to the present day. On the evening of 4 August 1945, the Dresdner Kreuzchor performed one of the first musical responses to the attack at their first post-war Vespers service in the Altstadt. Amid the ruins of the Kreuzkirche, the city's oldest church, they led a 1,000-strong congregation in a commemorative service to honour those who had lost their lives. The last work performed was Kreuzkantor Rudolf Mauersberger's mourning motet Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst (How Deserted Lies the City), a setting of ten lines from the Lamentations of Jeremiah completed on 30 March 1945. This was Mauersberger's first musical response to the firebombing – a topic he returned to repeatedly as he worked through this traumatic event in music.Footnote 8

Mauersberger's motet and its première offer a lens through which to examine the role that music played in formulating the earliest articulations of Dresden's post-catastrophic identity. This is an important augmentation of recent research on the aftermath of the Dresden attack, which has focused on the ways in which the city's post-war identity was shaped by the competing demands of cold war politics.Footnote 9 As cooperation between the Allies disintegrated and the map of occupied Germany became a hardened geopolitical division between western and eastern Europe, Dresden became an ideological battleground.Footnote 10 In the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ), later the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Allied attack on a German city during the Third Reich was recast as an offence against a city in the future Soviet bloc. Dresden became a central location for articulating East German identity around an emerging conception of anti-fascist victimhood.Footnote 11 Annual commemorations of the firebombing played a central part in this process: city officials have marked its anniversary each year since 13 February 1949. The Dresdner Kreuzchor participated in these initial commemorative activities and have continued to play a central role in the city's ritual of remembrance. They have performed a commemorative service on 13 February every year since the attack, and have been part of the city's official commemorations since the Kreuzkirche reopened in 1955. Other pieces on their programmes have varied, but Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst remains a staple of these services.

The Kreuzchor's involvement in Dresden's post-war reinvention is integral to understanding how Mauersberger's motet circulated in cold war contexts. Yet cold war politics do not account for the choir's activities in the immediate aftermath of the firebombing, and an exclusively political framework for understanding the choir's development following the Second World War has, on occasion, produced striking errors in accounting for the music used for remembrance of the Dresden event.Footnote 12 Mauersberger's first musical responses to it took place before the post-war political alliances were firmly in place. Furthermore, they were performed by and for local residents in response to the city's devastation at a time when many factors that defined the period were still in a state of flux. As these citizens sought to make sense of their experiences, the city around them became increasingly politicized in official narratives of the past in the SBZ and then the GDR. By the time of the first anniversary of the attack in 1946, the Soviet Occupation authorities actively discouraged mourning, and there were no official events held in 1947 or 1948 to provide a public outlet for grief.Footnote 13 Returning to Mauersberger's earliest response to the firebombing offers us access to this significant yet often misrepresented period in German history. Rather than position the Kreuzchor's responses to the attack within a cold war context, I contextualize Mauersberger's motet and its première within the long-standing customs of the Kreuzchor that began with the church's consecration in 1236 and extended into the Third Reich. In doing so, I demonstrate how the customs that had provided comfort to choristers and congregation during the wartime years continued to serve this purpose after the war. A better understanding of the choir's late wartime and immediate post-war activities can not only reveal the uses of music in the wake of this traumatic experience, but also inform recent efforts to write more nuanced histories of the shifts in discourse surrounding the Dresden firebombing.Footnote 14

Alongside these political considerations, Mauersberger participates in an aesthetic current known as the Trümmerkünste (‘rubble arts’) – a term used to describe a preoccupation across multiple artistic genres in the late wartime and early post-war period with Germany's physical and moral debris. Scholarship on these artistic developments has recently flourished in German studies, but these issues are less often discussed in relation to music.Footnote 15 A close analysis of Mauersberger's motet, contextualized within its site of production using archival documents emanating from the composer, choristers and members of the first post-war congregation, reveals that both the compositional process and the Vespers service at which this work was premièred aestheticized the cityscape following the war. In doing so, this work transformed the firebombing from a senseless attack into an event imbued with liturgical meaning and historical associations. Composition offered Mauersberger expressive possibilities in the immediate post-war moment at a time when he found formulating verbal responses difficult. In Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst the composer combined an Old Testament text with the long-standing practices of the Lutheran ars moriendi (the ‘art of dying’) to navigate through the new and incomprehensible post-traumatic circumstances following the bombing. Mourning could therefore take place through allegory rather than testimony, as Mauersberger mapped the Dresden attack onto pre-existing religious narratives of loss. The Vespers service further enhanced these compositional choices by reinforcing the Baroque Lutheran practices of allegorical mourning.Footnote 16 Particularly because the Altmarkt (the market square where the church is located) was the locus of efforts to clear the necropolis created by the firebombing in a sanitary manner, the Vespers service allowed the surviving population to reclaim the city centre as a space for remembrance. In this way, Mauersberger's motet was part of an initial effort to make sense of the attack by transforming the ‘rubble’ (or wartime debris) into a ‘ruin’ (an aesthetic object). This process took place through composition (as the composer adapted lines from the Lamentations of Jeremiah to form a descriptive account of the cityscape) and through performance (as the first Vespers service returned composer, choir and congregation to a significant site of destruction, transforming the Kreuzkirche into a space of contemplation). Assessing Mauersberger's motet and its post-war première with an ear to both its emotional surplus and its interlocking webs of meaning draws attention to broader concerns about the ethics and aesthetics of Trümmermusik (‘rubble music’) in the immediate post-war period, and places music in dialogue with other artistic responses to Germany's aerial destruction during the Second World War.

Dresden's Altstadt, 4 August 1945

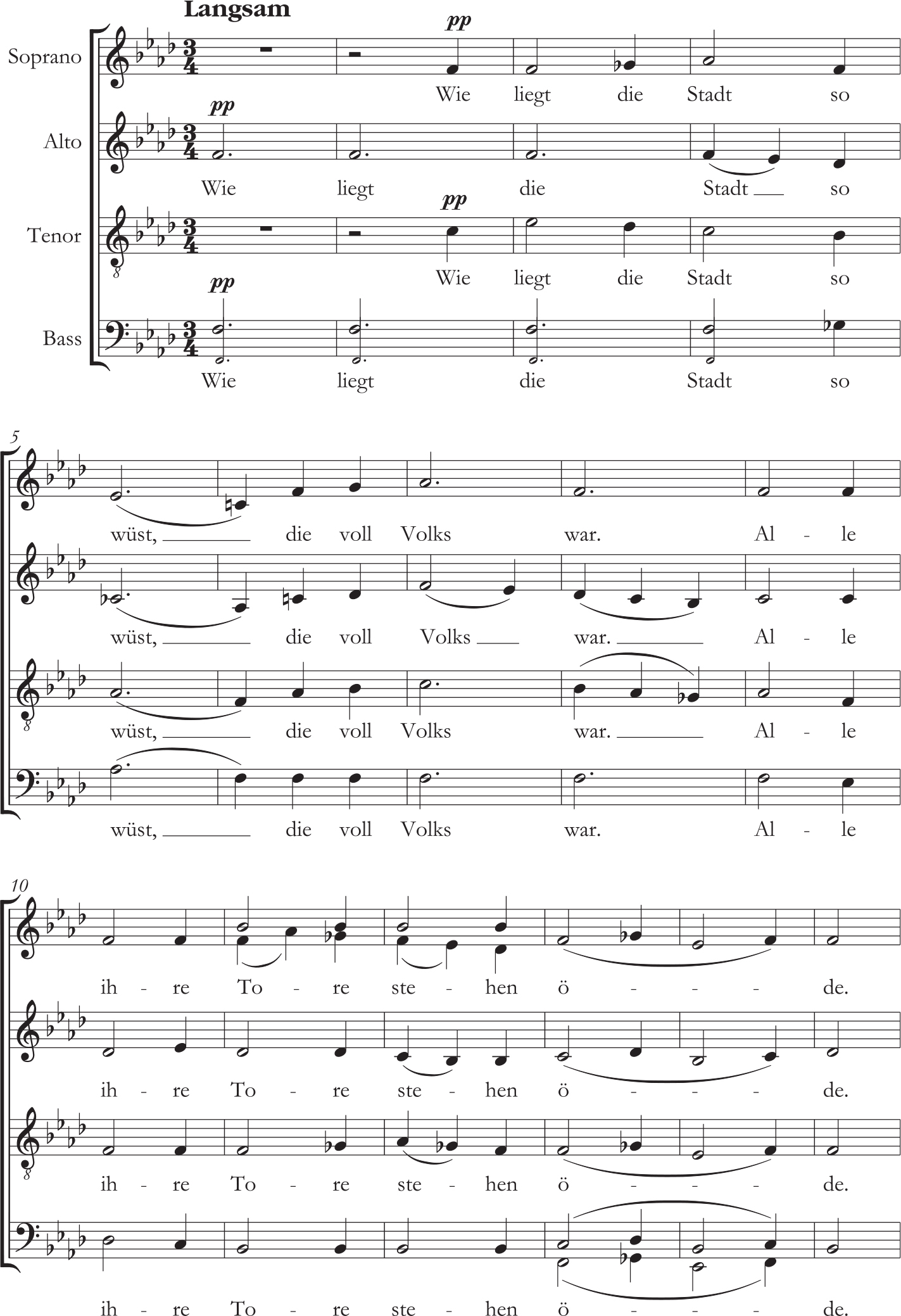

The iconic photograph shown in Figure 2, which is thought to be of the memorial service at the Kreuzkirche in 1945, captures some of the tensions that lie at the heart of Mauersberger's motet and its première. Footnote 17 Much like Peter's cityscapes, this image became part of the city's ‘visual archive’ of destruction: a series of images that were regularly reprinted in literature on the Kreuzchor, including articles about the choir's wartime activities published on anniversaries of the attack.Footnote 18 The photograph offers a microcosm of Dresden's two interlocking post-war reputations: as a Kulturstadt (‘culture city’) and an Opferstadt (‘victim city’).Footnote 19

Figure 2. Probably the first post-war Vespers service held in the Kreuzkirche, Dresden, on 4 August 1945 (though possibly a later service held on 11 May 1946). Photograph from the Kreuzkirche's community archive. Photographer unknown, reproduced from the private collection of Matthias Hermann, with his kind permission.

More pertinently, the image stages the disjuncture between the traumatic rupture caused by the firebombing and a desire to return to normality that characterizes the choir's late wartime and early post-war activities. Taken from the right balcony of the church, the photographer has provided an elevated view of the scene below. Congregants stand on the main floor, their attention drawn to the choir in front of the altar. Take in the scene as a whole and the city's destruction is self-evident. The open sidewalls leave the congregation unprotected from the elements, while the lack of pews indicates the extensive damage to the church interior, and probably a missing roof.Footnote 20 Focus in on the choir itself and the scene becomes more mundane. Gathering before the altar, Mauersberger and the Kreuzchor are re-enacting a centuries-old ritual that attracted large audiences of local congregants and curious visitors most Saturday evenings throughout the school year. The order of service (shown in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 1) bore the title Gedenkvesper in den Mauern der Kreuzkirche zu Dresden (Commemorative Vespers in the Walls of the Dresden Church of the Holy Cross), refracting the traumatic rupture of the February firebombing through the liturgical custom of holding public Vespers services on Saturday evenings that dates back to the church's early history. The musical and liturgical selections included works with long-standing associations with Lutheran funerary rites, performed alongside new pieces that Mauersberger wrote as a response to the disaster, concluding with Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst. Commemorating the attack in this way attempted to make sense of the post-war present by returning to the musical and liturgical customs of the choir's past.

Figure 3. Gedenkvesper in den Mauern der Kreuzkirche zu Dresden, 4 August 1945. Order of Service. From the private collection of Matthias Herrmann, reproduced with his kind permission.

TABLE 1 order of service for the commemorative vespers in the walls of the dresden church of the holy cross, 4 august 1945Footnote a

| 1. memorial words: Ihr wart wie wir (You Were Like Us), 1945 (première) |

Music: Rudolf Mauersberger (1889–1971)Text: Paul Dittrich |

| in remembrance of the deceased minister of the kreuzkirche: | |

| 2. Ecce, quomodo moritur iustus (Behold How the Righteous Man Dies), 1587 | Jacobus Gallus (1550–91) |

| in remembrance of all the deceased: | |

| 3. Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden (When Once I Must Depart from the St Matthew Passion), 1727 | Paul Gerhardt (1607–76), adapted by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) |

| scripture reading | |

| 4. sung by the whole congregation: Chorale: verses 7 and 8 of Die güldene Sonne (The Golden Sun), 1666 |

Gerhardt |

| prayers and blessing | |

| 5. Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst (How Deserted Lies the City), 1945 (première) | Music: MauersbergerText: from the Lamentations of Jeremiah |

a Adapted from the Order of Service for the Gedenkvesper in den Mauern der Kreuzkirche zu Dresden, 4 August 1945 (see Figure 3).

The service was typical in length and format, including five pieces of music with brief readings and prayers, though the circumstances by which the choir acquired these works bore the scars of the bombing's aftermath. The choice of repertory was limited owing to the fact that the Kreuzchor's library had been destroyed, and many choristers – as well as Mauersberger himself – had suffered vocal injuries from the smoke. Mauersberger spent the months following the firebombing in his home town of Mauersberg, a village in the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains), about 50 miles south-west of Dresden near the Czech border. When he returned to the Saxon capital at the end of the war, he brought music back with him from his own library.Footnote 21 Some choristers even recall the cantor transcribing works from memory in the early post-war months.Footnote 22 Traces of the Dresden attack also permeate the individual works: three of the five performed were dedicated to specific members or groups of the Kreuzkirche community who had lost their lives that night in 1945. These dedications seem to reclaim and honour the memory of the deceased.

The service was framed by Mauersberger's original compositions. He wrote the first piece, Ihr wart wie wir, in honour of the choristers who died in the firebombing.Footnote 23 The first of the three pre-existing works performed at the memorial Vespers service was Ecce, quomodo moritur iustus by Jacobus Gallus (or Handl, 1550–91), from his four-volume Opum musicum, a collection of 374 motets for the liturgical feasts of the Catholic Church year.Footnote 24 Ecce, quomodo moritur iustus is a setting of a Tenebrae text from the Book of Isaiah (chapter 57, verses 1–2) originally intended for Holy Week, although it has also been used in Catholic and Protestant burial services since the sixteenth century.Footnote 25 Notably, Gallus changed the final line of the text to evoke Jerusalem as a final resting place, calling on a site-specific practice of memory and remembrance that also permeates Mauersberger's own responses to the firebombing. By dedicating this work to the memory of the deceased minister of the Kreuzkirche, the service evoked the burial practices of central Europe and redeployed this old music in a new context that served a similar expressive purpose.

Two works from the German Protestant funerary repertory next served to commemorate ‘all the deceased’. Both date from the golden age of Lutheran church music, and from a period in which Dresden was at the heart of this practice. First the Kreuzchor performed the Saxon minister Paul Gerhardt's chorale Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden as adapted by Bach in his St Matthew Passion (1727). Drawing on Bach's Passion setting of this chorale called on paschal repertories that enhanced the associations with Christian sacrifice. These connections also permeated Mauersberger's own mourning motet, Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst. More generally, as Walter Frisch has noted, Bach's music had consistently been considered synonymous with health and healing in Austro-German contexts since the late nineteenth century.Footnote 26 In the aftermath of the Dresden firebombing and during the early months of the Soviet Occupation, a familiar mourning repertory might have provided a structured expression of grief that offered a temporary therapeutic outlet for those present at the service.

After a reading from scripture, the whole congregation sang the seventh and eighth verses of another Gerhardt chorale, Die güldene Sonne (1666). The inclusion of a congregational hymn was typical of Vespers at the Kreuzkirche, but in this context communal singing could have more specific associations with early Lutheran funeral practices. As Craig Koslofsky describes in his history of the development of these practices from the Reformation to the early eighteenth century, ‘honorable’ Lutheran funerals ‘required the participation of the community; both normative and descriptive accounts refer to this participation as the basis of the ritual’.Footnote 27 This is no doubt in keeping with other aspects of Lutheran theology, but it is important to note that the Lutheran burial ritual was focused on offering comfort to the living rather than to the deceased.

In choosing music that had specific mourning associations in overwhelmingly Protestant Saxony, the Kreuzchor's performance captured the present moment in a musical language to which both the performers and their audience were accustomed. This repertory attempted to provide consolation through long-standing liturgical and musical customs, and would also have had strong associations with the immediate past. As Pamela Potter and Erik Levi have shown in their work on musicology and musical institutions in the Third Reich, Nazi organizations cultivated early-music repertories that could demonstrate the cultural superiority of the German Volk.Footnote 28 In keeping with a focus on amateur choral societies (which were already popular in the Weimar Republic), musicologists who had worked before 1933 on editions of Renaissance and Baroque music continued to do so in the Third Reich, subtly shifting their activities to cater more to performance than to historical editing.Footnote 29 When he became Kreuzkantor in 1930, Mauersberger cultivated the stile antico (and a cappella sixteenth-century-style counterpoint more broadly) as the choir's hallmark sound in both live performance and on recordings.Footnote 30 During the Third Reich, the choir began disseminating this style to an audience beyond Dresden, releasing recordings of sacred works by Bach, Brahms, Bruckner and Schütz, and secular music drawn primarily from folk repertories, including works by Isaac, Mendelssohn and Schumann.Footnote 31 Mendelssohn stands out in this list for the anti-Semitic attacks launched against his music in the Third Reich.Footnote 32 Yet some accounts of Mauersberger's activities in the Third Reich draw attention to the choir's performance of Mendelssohn's music on a tour to the USA in 1938,Footnote 33 confirming the work of recent musicological studies suggesting that musical life in the Nazi state was significantly more complicated than official decrees and propaganda tracts would suggest.Footnote 34 Mauersberger's penchant for promoting earlier repertories continued into the post-war period. In the GDR, he spearheaded a commemorative festival in honour of Schütz, which included recording the composer's complete works with the Kreuzchor.Footnote 35 His attention to Schütz is significant beyond the Renaissance composer's local reputation, because Schütz made significant contributions to the Protestant funerary repertory that had subsequently influenced Bach and were later adopted in the liturgical music of Brahms.Footnote 36

The genres and musical styles included in the Vespers programme were those to which Mauersberger turned in formulating his own compositional response to the firebombing. While his musical responses to the attack are undoubtedly expressions of trauma, this service cannot be detached from the local customs, the informal alliances formed between Church and State while the National Socialists were in power, the support for cultural institutions and individual artists during the Third Reich and the overarching lack of attention to specific musical customs and aesthetics by members of the Nazi Party. In placing himself within a musical lineage that had both local and national resonance and calling on the liturgical customs associated with a historicist musical style, Mauersberger both formulated a response to the Dresden firebombing and participated in the cultural continuities that had allowed him to maintain his position as Kreuzkantor during the most tumultuous political regimes of the German twentieth century.

The visual rhetoric of ruins

The musical scene at the Kreuzkirche on the evening of 4 August 1945 was not unusual in post-war Europe. The historians Celia Applegate and Elizabeth Janik have drawn attention to the persistent custom of cultural institutions performing in ruins across German cities during the late wartime and early post-war years.Footnote 37 The choir's performance thus connects Dresden – a city that is often regarded as exceptional in the history of the air war – to other German cities and their performances in the early years after the war. This provides a lens through which to consider some of the possible qualities of Trümmermusik as both a therapeutic and an aesthetic activity. Rubble was a prominent trope across the arts in the years 1943–50, as photography, memoir, literature and film served as expressive outlets for artists and citizens to confront the damage wreaked by total war. Artists used these genres to document destroyed German cities in vivid and highly realistic detail. Julia Hell notes how a focus on description seen across the so-called Trümmerkünste creates ‘scopic scenarios’ that transform rubble, or the aftermath of destruction, into ruin, or an aesthetic arena of contemplation.Footnote 38 Andreas Huyssen concurs, remarking that ‘bombings are not about producing ruins. They produce rubble. But the market has recently been saturated with stunning picture books and films […] of the ruins of World War II. In them, rubble is indeed transformed, even aestheticized, into ruin.’Footnote 39 Performing music amid the ruins intensifies the encounter with rubblescapes by bringing audience members into these damaged spaces. These concerts frame the encounter with rubble highly selectively, conveying a sense of resilience in the face of extensive suffering. Many orchestral institutions drew repertory almost exclusively from the nineteenth-century Austro-German canon, synchronizing what Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann calls the ‘visual experience of defeat’ with overtly expressive music, and thus romanticizing destruction itself.Footnote 40 The traces of these events are often captured visually in photographs or descriptively in rubble literature: music was not only a rubble art in its own right, but also manifested in other representations of rubble.Footnote 41 Yet as Toby Thacker observes, because such ‘powerful images of musicians performing in ruined buildings, for rapt but subdued audiences, have taken on an iconic role in our imaginings of postwar Germany’ they have also served as a mechanism for avoiding a discussion of musicians’ involvement in the Nazi Party.Footnote 42 Instead, these concerts serve as a wordless shorthand for German suffering, covering up the connections between musical activities in the Third Reich and the years of occupation. One of Thacker's examples for this argument is the Kreuzchor service on 4 August 1945, where choristers who would have been wearing the uniform of the Hitler Jugend (the youth organization of the Nazi Party) three months earlier now continued their musical activities in the post-war period with the support of the Soviet Occupation forces.Footnote 43

Despite the trope of ruin concerts in rubble films and literature, new musical works have not yet been a prominent focus in the study of Trümmerkünste. Concerts performed in damaged concert halls have captured the attention of musicologists, but they are typically taken as markers of melancholy nostalgia and avoidance.Footnote 44 Abby Anderton demonstrates in the context of post-war Berlin, however, that performances in ruins are but one form of engagement that musicians had with their desecrated cityscapes.Footnote 45 Focusing on the multiple ways in which musicians engaged with the air war lends a different perspective to the realities facing musicians in the early post-war months. Pieces such as Mauersberger's Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst reveal how the rubble-to-ruin transformation could take place in real time through musical performance, indicating that such aesthetic transformations offered one way to navigate through the initial stages of the traumatic experience of the air war. While critiques of early post-war music-making rightly draw attention to the ways in which music served as an avoidance mechanism for confronting the national past, it is problematic to oversimplify the music at the heart of such performances. Despite all efforts to avoid the surrounding difficulties, these performances inevitably served as manifestations of, and outlets for confronting, the various crises facing German citizens in the first months following the war. In the photograph of the Vespers service, for example, the scars of the physical space make the uneasy juxtaposition between normalization and exception plain, and these tensions manifest in the choir's musical choices. These works seem to reflect a similar tension between the need for a new musical language to account for this scale of loss in the firebombing and the desire to return to the familiar in the face of an immense and incomprehensible traumatic moment. At the same time, the Vespers programme reveals how the choir's position during the Third Reich played a significant part in their experiences of the attack and efforts to confront its aftermath.

The Kreuzchor at the end of the Second World War

Mauersberger and the Kreuzchor were living in the Altstadt at the time of the firebombing, having been an active performing force in the Third Reich and throughout the war. Choristers (known as Kruzianer) were between the ages of nine and 18, and drawn from across Saxony: locals would have lived with their families and attended the Kreuzschule (the school of the church of the Holy Cross), while more distant members (Alumnat) boarded at the Kreuzschule, where they were under the care of Mauersberger and other pastoral staff.Footnote 46 Mauersberger joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and the choir he led participated in the cultural life of the Third Reich.Footnote 47 Former choristers and church staff made posthumous claims of ‘inner emigration’,Footnote 48 yet some choristers defend Mauersberger's career choices by insisting that he cared ‘only for the Kreuzchor’, which led him to adopt an apolitical lifestyle in a politically charged era.Footnote 49 There are scholars who note that compromise with the National Socialists would have been unavoidable, and was widespread in musical institutions during the Third Reich.Footnote 50 The narrative of inner emigration fits within what the historian Neil Gregor describes (in relation to Wilhelm Furtwängler) as ‘an image of art in the service of humanity and against dictatorship which suggested that culture had been both victim and agent of resistance under the Third Reich’.Footnote 51 Indeed, Mauersberger has been described as ‘Furtwängler unter den Kirchenmusikern’ (‘Furtwängler among the church musicians’), a point noted by the former chorister and Mauersberger scholar Matthias Herrmann in his biography of the composer (although the source from which he is quoting dates from 1939, which gives the turn of phrase a slightly different meaning from that which it acquired in the post-war period).Footnote 52 The influence of the Nazi Party extended to the choir as well.Footnote 53 Upon the amalgamation of church youth groups and Nazi youth organizations in 1933, choristers became members of the Hitler Jugend.Footnote 54 These activities are not exceptional, but fit within a pattern that Michael Kater describes as a ‘silent alliance between National Socialism and Protestant Christianity’ that was disseminated through ‘the medium of church music’.Footnote 55

As the Allies did not target the eastern reaches of the Reich until the final year of the Second World War, the choir's direct experience with the war effort prior to the firebombing was through older members enlisting in the Wehrmacht, and the swelling number of refugees around the city. Their musical activities nevertheless remained relatively stable. Even after the Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels declared a nationwide ban on formal concerts as part of the total war effort in August 1944, music during Vespers and other religious services was exempt.Footnote 56 In other words, the history of the Kreuzchor in the twentieth century is marked by what Gregor calls ‘deeper associations’ that connect their pre-war, wartime and post-war values and activities.Footnote 57 This period of the institution's history is often dealt with indirectly in histories of the choir, but it is essential to an understanding of the Kreuzchor's experience of the firebombing, the wartime years and the aftermath of total defeat.

The choir suffered significant losses on the night of 13–14 February 1945. Eleven choristers died in the firebomb attack. Kruzianer testimonies indicate that other members escaped from their makeshift cellar shelter to wander the desecrated streets of the city in small groups.Footnote 58 With their boarding school and church destroyed, surviving choristers spent the final months of the year in Meissen – a medieval town to the west of the city renowned for its production of porcelain (or ‘Dresden China’) – under the care of pastoral staff. Mauersberger also relocated, spending the remaining months of the war in his home town. During these months in rural Saxony he penned Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst. Mauersberger's correspondence with choristers and staff in Meissen during this period reveals the slow pace of clearing through the rubble and disseminating information to those who had lived in the city centre prior to the attack. A letter to the chorister Klaus Zimmermann dated 3 March 1945 is Mauersberger's earliest written reflection on Dresden's destruction:

It was a sincere joy [sic] in my great sorrow about everything we have lost: the six [sic] dead alumni, our beloved Kreuzschule, the beautiful singing hall, the Kreuzkirche! How can one endure something so terrible! Writing this causes me great difficulty. I am still suffering from the paralysis in my fingers that appeared after the terrible second attack, which I experienced, lying in the Bürgerwiese park, not far from the Kreuzschule. As if through a miracle, I remained alive. […] The smoke poisoning has completely ruined my voice. Student Councillor Richter is suffering from the same problem. […] Oh, what would I give for us to have no dead among the choir! I cannot escape thinking about them and the other dead we have seen.Footnote 59

Even though this letter is not an overt testimony of the firebombing, there are traces of the emotional blockages and incomplete thoughts that have been considered common markers in the early aftermath of a traumatic experience. In her study of literature about the air war, Susanne Vees-Gulani interprets many of the texts she discusses symptomatically, drawing out moments at which the authors exhibit symptoms of psychological distress, particularly Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).Footnote 60 A similar argument can be made for Mauersberger's writing in the wake of the Dresden firebombing. His correspondence with Zimmermann reveals an emotional surplus that comes through most immediately in his lack of fully formed thoughts. The tone of his letter is split between his account of the effects of the bombing and his own responses to the devastation. He itemizes his losses, any single one of which would be cause for grief, yet he attributes expressive blockages to physical rather than mental ailments. Writing is difficult, for example, because he suffers from paralysis in his hands, and he goes on to note that the smoke has completely ruined his voice. In her landmark study of trauma and its aftermath, the psychiatrist Judith Herman notes that a focus on physical ailments is common in testimonial accounts written during the early stages of grief and traumatic recovery.Footnote 61 In another parallel with Herman's research, Mauersberger juxtaposes wishful thinking with the acknowledgement that he cannot escape the traumatic aftermath of the attack.

This letter also reveals the difficulties the composer had in accessing accurate information about the extent of the damage caused by the firebombing. At the time of writing, he knows that six choristers have died, which means that the other five victims must not yet have been found. On 9 April 1945, a letter sent to choristers’ parents by pastoral staff in Meissen reported only seven deceased members of the choir.Footnote 62 Clearing the destruction and accounting for the deceased after aerial bombing attacks was an uneven process across war-torn Germany. In many cities targeted in the air war, accounting for the deceased was often a task taken on by local community organizations, including churches and the Red Cross.Footnote 63 The Kreuzchor took on similar tasks for their own community in the months after the firebombing. While in Meissen, members of the school's administration installed a makeshift operational framework for the Kreuzchor. Remnants of this framework survive in the form of monthly letters sent out to the parents of choristers who had resided in the boarding school, apprising them of the latest developments from their temporary location. In the letter sent to parents on 9 April, the principal of the Kreuzschule issued a statement on the bombings that voiced collective grief, speaking of the devastation and loss the school had experienced as a community. He offered consolation and reassurance in the form of concrete actions that the Kreuzchor were taking in the wake of the bombings, most notably recommencing rehearsals at their temporary location and continuing to keep parents informed about missing students and events unfolding in the capital.Footnote 64 By disseminating information about choristers to parents and the Kreuzkantor himself, the choir forged new kinship bonds, forming what historian James Winter has called ‘communities of the bereaved’ to make sense of the chaos.Footnote 65 Already a tight-knit community prior to the firebombing, the Kreuzchor performed a similar task in the wake of their own catastrophe, connecting biological relatives and strengthening social bonds as well.

Mauersberger's musical testimony

Several members of the Kreuzchor wrote accounts of 13–14 February 1945, which are now housed in the choir's archive.Footnote 66 Mauersberger did not contribute to this testimonial collection, though brief reports of his experiences of the firebombing were printed in the official national newspapers of the ruling Socialist Unity Party (Neues Deutschland) and the Christian Democratic Union (Neue Zeit) on the tenth anniversary of the attack in 1955.Footnote 67 Music offered the composer an alternative outlet for processing this event, beginning in the immediate aftermath of the firebombing and continuing well into the post-war era. On Saturday of Holy Week (30 March 1945), less than a month after he had written to Zimmermann and a month before the end of the war, Mauersberger completed Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst. The motet was composed in four days,Footnote 68 with his chosen lines from the Lamentations of Jeremiah set stile antico and a cappella – stylistic choices that were intimately familiar to the composer from his professional obligations and religious commitments. In the post-war period he wrote several works that took Dresden and the firebombing as their subject,Footnote 69 including the Dresdner Requiem (1947–8, revised until 1960), which became part of annual commemorations of the attack.

In analysing the first of Mauersberger's musical responses to the firebombing, I proceed from a definition of trauma as an incident that cripples a person's cognitive, psychic and physical capacities.Footnote 70 Metaphors of silence circulate in both clinical and academic variants of trauma studies, where recovery typically entails finding ways to make sense of a traumatic incident and its effect on the traumatized subject. Earlier theorists tried to reconnect common and traumatic memories through narration or re-enactment of the event, as is seen most notably in Sigmund Freud's distinction between pathological ‘repetition’ and its counterpart, ‘working through’.Footnote 71 Later developments in trauma therapy have shifted the focus towards making sense of the post-traumatic subject, particularly as a means of returning agency to the survivor of a traumatic event.Footnote 72 In his 2008 survey of developments in trauma studies, Roger Luckhurst notes the increasing split between clinical and academic approaches to the topic: while trauma therapy has moved away from Freudian approaches to recovery in favour of neurobiology and cognitive behavioural therapy, literary theory remains marked by Freudian and post-Freudian imprints, which continue to privilege trauma as a crisis of representation.Footnote 73 One of the most prominent models in cultural theories of trauma is that proposed by Cathy Caruth, who adopts a Freudian framework to describe trauma as the ‘narrative of a belated experience’. From this perspective, the force of a traumatic incident is often so strong that it does not immediately register for those who have experienced it, and instead needs to be recovered and reconstructed in later testimonies, in a process known in psychoanalysis as the ‘talking cure’.Footnote 74 Recent musicological engagements with trauma studies have incorporated some clinical developments. Maria Cizmic, for example, combines approaches from ‘psychological, sociological, and constructivist approaches to trauma’ to analyse music's ‘multiple functions’ as a form of witness to both trauma and the process of recovery in eastern European contexts. One of her aims in adopting these pluralistic methodologies is to divert ‘some attention away from the primacy of language in trauma theory’.Footnote 75 In his study of music in wartime Iraq, J. Martin Daughtry draws attention to the violence that sound itself can inflict, noting military situations where the sonic force can produce traumatic effects on those who experience it.Footnote 76 Both approaches turn away from logocentric models of understanding traumatic experience and towards theories of embodiment, affect and cognition.

Mauersberger's response to the firebombing indicates that music offered something of a performing cure for coming to terms with its aftermath and the Second World War. While the composer incorporates elements of a psychoanalytic model of talking through a traumatic event and creating a narrative for oneself that integrates the traumatic memory into life experience, he does so through allegory rather than testimony. Part of his compositional process is a substitution of one form of textual expression for another, but an equally important dimension of Mauersberger's music is the way in which it allows for the composer to process the firebombing by recasting it in a familiar musical language. This has parallels to Herman's argument that recovering from a traumatic experience requires the establishment of safety before recounting the traumatic experience can begin.Footnote 77 Moreover, performances of the motet heighten the temporal dimension of the narrative, facilitating expression and reaction without requiring a direct form of testimony.

Mauersberger's setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah reframes the original meaning of his chosen lines. The Lamentations of Jeremiah's five chapters recount the destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BC. The chapters contain 154 verses in total, ten lines of which Mauersberger chose to use in his motet. Table 2 provides the complete text of Mauersberger's motet, with details of the original chapter and verse from the Lamentations for each line, as well as an English translation.Footnote 78 There are several similarities to the scopic scenarios that Hell and Hoffmann consider central to Trümmerkünste in Mauersberger's chosen fragments. Just as authors, photographers, diarists and film-makers responded to Germany's destruction by documenting it in striking detail, Mauersberger has selected lines from the Lamentations of Jeremiah that perform a similarly descriptive task, which he then further enhances through musical word-painting. The opening two lines of the motet, for example, ‘How deserted lies the city, that once was full of people. / All her gates are desolate’, echo the photographs of German cities reduced to charred buildings and devoid of human life.

TABLE 2 lines selected from the lamentations of jeremiah to create mauersberger's mourning motet wie liegt die stadt so wüst

| Chapter/verse/line | Text | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1/1/a | Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst, die voll Volks war. | How deserted lies the city, that once was full of people. |

| 1/4/b | Alle ihre Tore stehen öde. | All her gates are desolate. |

| 4/1/b | Wie liegen die Steine des Heiligtums vorn auf allen Gassen zerstreut. | The stones of the sanctuary are scattered about at the sides of the street. |

| 1/13/a | Er hat ein Feuer aus der Höhe in meine Gebeine gesandt und es lassen walten. | From on high he hath sent fire into my bones, and hath let it happen. |

| 2/15/c | Ist das die Stadt, von der man sagt, sie sei die allerschönste, der sich das ganze Land freuet. | Is this the city that men called the perfection of beauty, the joy of the whole country? |

| 1/9/b | Sie hätte nicht gedacht, daß es ihr zuletzt so gehen würde; sie ist ja zu greulich herunter gestoßen und hat dazu niemand, der sie tröstet. | She would not have thought that in the end this would happen to her: she has been too horribly brought down and also has no one to comfort her. |

| 5/17 | Darum ist unser Herz betrübt und uns're Augen sind finster geworden. | Therefore our heart is sorrowful and our eyes have become dim. |

| 5/20 | Warum willst du unser so gar vergessen und uns lebenslang so gar verlassen? | Wherefore dost thou forget us forever, and forsake us for our entire life? |

| 5/21 | Bringe uns, Herr, wieder zu dir, daß wir wieder heim kommen! Erneue uns're Tage wie vor alters. | Turn thou us unto thee, O Lord, so that we return home! Renew our days of old. |

| 1/20/a | Ach, Herr, siehe an mein Elend! | Behold, O Jehovah; for I am in distress! |

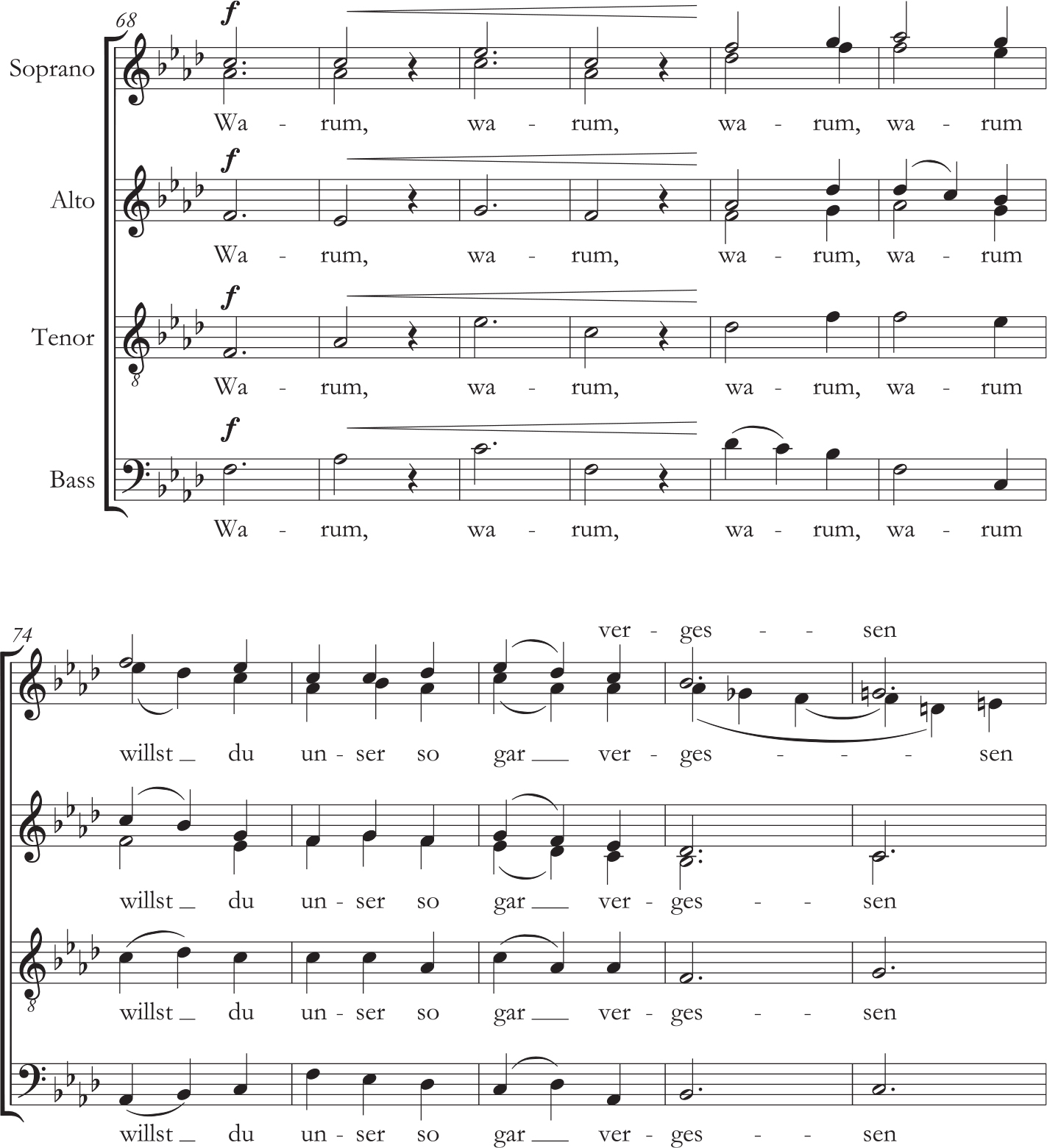

In the musical setting, the beginning of which is shown in Example 1, the harmonic and melodic motion is weighted down by pedal notes and repeatedly thwarted by word-painting. A sense of catastrophic stupor manifests in narrowly voiced chords, the downward trajectory of the vocal line and the low range of the upper voices. Set in F Phrygian mode, the vocal parts rise slowly out of silence, with the alto and bass providing a pedal note to support the conjunct, contrary-motion lines of the soprano and tenor. Moments where cadences might be expected are thwarted in favour of progressions to closer chords on the word ‘wüst’ (‘deserted’, set as a minor mediant chord in bar 5) and chains of bare fifths on the word ‘öde’ (‘desolate’, bars 13–15). By drawing attention to individual words, Mauersberger crushes the harmonic direction of the vocal lines under the weight of destruction conveyed in the Lamentation fragments.

Example 1. Opening of Mauersberger's Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst, bars 1–15. Text translation: ‘How deserted lies the city, that once was full of people / All her gates are desolate.’

In responding to the firebombing by using the Lamentations of Jeremiah, Mauersberger maps the destruction of Dresden in 1945 onto one of the most historic sites of urban destruction in the Judeo-Christian tradition, participating in a long-standing custom of depicting fallen cities in Jewish and Christian contexts across the West and near East.Footnote 79 Jan Assmann dates the origins of the city lament to the Sumerian civilization (third millennium BC), making it one of the oldest literary genres, and cites the Lamentations of Jeremiah as one of the most familiar examples of it.Footnote 80 Lamentations are also one of the earliest forms of public commemoration.Footnote 81 This ancient lineage had been repeatedly used to make sense of destruction in both Judaic and Christian faiths – a practice that continued into the Second World War. In his comparative study of experiences of the air war in England and Germany, Dietmar Süss describes how some German parishioners found the Lamentations of Jeremiah useful as an ‘interpretive and semantic frame of reference in which what was inconceivable, the rejection of religion amid a homeland in ruins, could nevertheless be captured in words’.Footnote 82 A cardinal in Munich, for example, attempted ‘to place the bombing of cities in the biblical tradition of the destruction of Jerusalem, as in the Lamentations of Jeremiah, which […] acquired “particular resonance” in view of the bombed-out churches’.Footnote 83 There were thus many precedents – historical and contemporary – for Mauersberger's textual choices.

At the same time, the Lamentations were not a straightforward text within Mauersberger's own denomination of Christianity. Martin Luther did not write a commentary on the Lamentations, which were not a central part of German Protestant worship. Nevertheless, two musical uses of the Lamentations had become standard and were probably familiar to Mauersberger from organizing weekly services at the Kreuzkirche since his appointment as Kreuzkantor in 1930.Footnote 84 These were Matthias Weckmann's 1663 setting of the Lamentations as a spiritual concerto in response to the plague in Hamburg and Bach's use of verse 12 of chapter 1 in his cantata Schauet doch und sehet, ob irgendein Schmerz sei (Behold and See, Should There Be Sorrow, Cantata 46), written in 1723 for the Tenth Sunday after Trinity, when the readings for the Gospel are taken from Luke, chapter 19, verse 41, in which Christ weeps over Jerusalem.Footnote 85

Perhaps the most significant association of the Lamentations for understanding Mauersberger's motet is their use during Holy Week. In the only sketch for the piece, the beginning of which is shown in Figure 4, Mauersberger marks Karsamstag (Holy Saturday) as the date of composition, situating his response to Dresden's destruction within the rhetoric of sacrifice and resurrection that accompanies the Easter season. Lutherans use selections from the Lamentations on Good Friday – a departure from Catholic traditions where recitations of the Lamentations are split over Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday. These associations in the liturgical calendar are further intensified by the date of Dresden's destruction: in 1945, Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday fell on 13 and 14 February respectively. By writing this motet at the end of Lent, the sacrifice of Easter accrues a host of associations that are never directly voiced, but nevertheless linger for congregants of a predominantly Lutheran city. Mapped so directly onto the Christian calendar, the firebombing takes on an aura of sacrifice.

Figure 4. Rudolf Mauersberger, first system of manuscript score of Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst. The term ‘Karsamstag’ can be seen under Mauersberger's name above the first stave on the right-hand side. Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Mus 11302–C–500, 1. Reproduced by the kind permission of the Music Department of the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden. Also available <http://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/71262/1/>.

These problematic associations place Mauersberger in dialogue with the ethical complexities of confronting German guilt in the aftermath of the Second World War and the Holocaust. The Lamentations of Jeremiah recount the destruction of Jerusalem, a Jewish city, at the hands of pagan Babylonians. Adapting this text to the Dresden firebombing produces an unsettling revision of victimhood that was all too common during the transition from war to peace around 1945.Footnote 86 In their original form, the Lamentations of Jeremiah engage deeply with topics of sin, punishment and guilt. But in using this text, is Mauersberger recognizing his own culpability, seeking absolution or appropriating the affective charge of the Old Testament text for his own representation of grief after the bombings? An answer could lie in the fact that Mauersberger entirely omits chapter 3 of the Lamentations from his motet, drawing lines only from the other four. The missing chapter catalogues Jerusalem's crimes, while the others describe the city's falsehoods and God's wrath, which could have provoked more overt associations with the culpability of German citizens in the Third Reich. Moreover, looking through the motet's text as a whole, Mauersberger's chosen lines are relatively passive. There are interrogations, accusations and pleas, but attribution of blame or lines that might suggest causes are avoided entirely. If the composer was using the Lamentations to express his guilt, it remains a spectre accessible only to those deeply familiar with the original text.

Such avoidance was common in the immediate post-war period, as writers of ‘rubble literature’ focused instead on the immense devastation they saw around them rather than the larger implications of moral destruction. This microscopic focus on physical debris was not lost on returning exiles such as Hannah Arendt, who observed many Germans exchanging postcards of damaged cities while ignoring mounting evidence of Nazi crimes, and accused them of ‘a half-conscious refusal to yield to grief or a genuine inability to feel’.Footnote 87 More recent scholarship on artistic production in these harrowing post-war years has been careful not to equate the lack of expression of guilt with its complete absence. Closer engagements with the Trümmerkünste often critique what Anke Pinkert regards as the ‘conventional discussions that have described early postwar memory culture in terms of silence, repression, or amnesia’ by offering analysis of artistic production ‘that accounts for the range of ways in which feelings, or structures of affects, related to grief, sadness, shame, or depression, were central to early postwar life and the Germans’ difficulty to come to terms with the Nazi past’.Footnote 88 Vees-Gulani argues along similar lines for a closer consideration of sentiments that were not directly expressed immediately after the war but manifested beneath the surface of verbal expression. To avoid ‘misreadings’ of German writings about the air bombings, she argues, ‘German guilt must serve as an underlying current for literary production.’Footnote 89 These considerations can also inform Mauersberger's creative choices, as the composer calls on musical and liturgical symbols to put forward multiple allegorical interpretations of the firebombing.

Mauersberger's inclusion of a line from chapter 2, verse 15 (‘Is this the city that men called the perfection of beauty, the joy of the whole country?’) echoes Dresden's reputation as ‘Florence on the Elbe’, which became a refrain in early discourse emphasizing Dresden's cultural prowess. Throughout the war, Nazi officials and the city's residents upheld the view that the city's Baroque architecture and cultural heritage would exempt it from a bombing attack.Footnote 90 Mauersberger's musical setting of these lines gestures towards the rhetorical context of the original Lamentations, where this line is declared by Babylonians who are mocking Jerusalem's vanity as they destroy its buildings. Two common features of the biblical lament are contained in this single line: it draws on what Edward L. Greenstein describes as ‘a stark contrast between the present tragedy and the once-glorious past’, while the declaration of this line by Babylonians indicates that it is in fact ‘rejoicing at an enemy's downfall’.Footnote 91 In Mauersberger's motet the text is cast both harmonically and through vocal forces as an interrogation and response (bars 31–45 are shown in Example 2). The words ‘Is this the city that men called … ’ are sung by soloists, gradually moving the tonal centre towards D♭ major to set up the full choir's response. The second half of this verse (the words ‘the perfection of beauty, the joy of the whole country’) is one of the longest stretches of the motet in a major key. A D♭ pedal in the bass voice in bars 36–9 supports the choir's responses to the soloist's question, and during the repetition of the word ‘allerschönste’ (‘the perfection of beauty’) in bars 38–41, a perfect cadence in D♭ further establishes this as the temporary tonal centre of the motet.

Example 2. Setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah, chapter 2, verse 15, in Mauersberger's Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst, bars 31–45. Text translation: ‘Is this the city that men called the perfection of beauty, the joy of the whole country?’

In his musical setting Mauersberger evokes mortuary customs from the Renaissance, placing himself directly in a long-standing lineage of using the stile antico for funeral music in the Lutheran church.Footnote 92 He references one predecessor in this lineage specifically: Brahms. These connections resonate in several of Mauersberger's musical responses to the Dresden firebombing. Both composers realized complete versions of a Protestant Requiem Mass in addition to stand-alone mourning motets: Brahms's grief-ridden motet Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen? (Wherefore Is Light Given to Him That Is in Misery?, op. 74 no. 1, completed in 1877) postdates his Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem, op. 45, written between 1865 and 1868), while Mauersberger captured his raw emotional distress in Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst in 1945 before formulating a more structured response to the firebombing in the Dresdner Requiem.

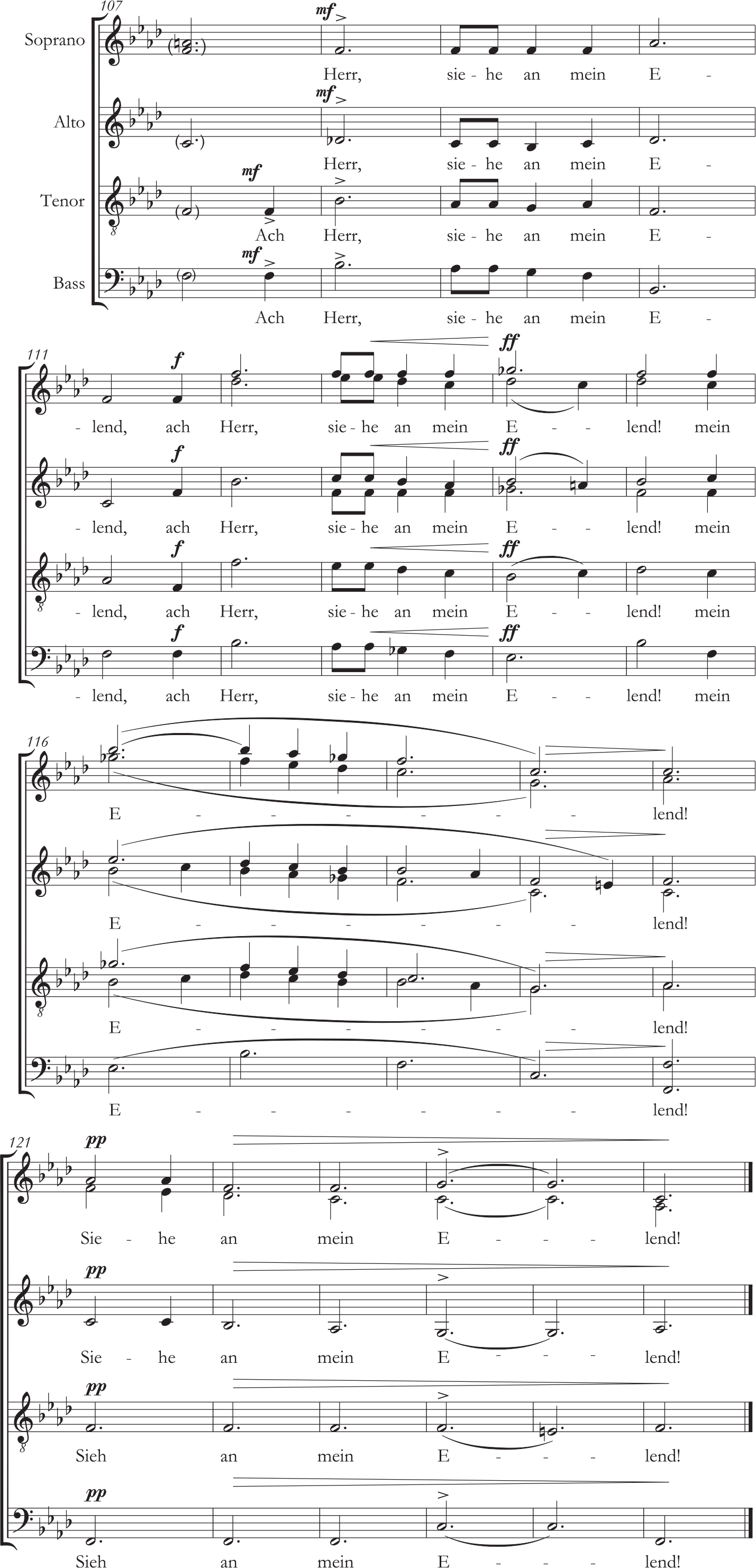

There are strong structural and musical parallels between Mauersberger's and Brahms's mourning motets, particularly in their respective treatments of the text. Through his study of Brahms's notebooks and annotations of his copy of the Lutheran bible, Daniel Beller-McKenna has shown that Brahms sutured together the text for Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen? from liturgical texts that conveyed similar themes. The motet incorporates textual fragments from the Book of Job, the Lamentations of Jeremiah and the Epistle of James. Beller-McKenna observes that the text of the resultant work shifts from Job's questioning to Luther's consolation.Footnote 93 Lamentations have a similar trajectory as a genre, and this is seen in the Lamentations of Jeremiah: the book proceeds from the primal outrage of chapter 1; passes through various stages of negotiation, disbelief and sin in chapters 2 and 3; offers an in-depth description of Jerusalem in chapter 4; and concludes in a mode of collective prayer in chapter 5.Footnote 94 In addition to using individual lines of this text to recount the firebombing, Mauersberger also adapted and repurposed the liturgical structure as a whole to formulate a response that resonates with different stages of grief expressed in each chapter of the Lamentations. Brahms did something similar in Warum ist das Licht gegeben? Both composers evoke this progression from interrogation to acceptance by drawing texts from this tradition, but also circumvent a progression from isolation to consolation through their musical settings. For his part, Brahms transforms Job's relentless question ‘Warum?’ into a refrain heard throughout his work (see Example 3a). Instead of a linear trajectory leading towards consolation, these interjections create a cyclic expression of grief and concern.Footnote 95

Example 3a. Johannes Brahms, Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen? (Zwei Motetten, op. 74), bars 1–6: ‘Warum?’ refrain.

Mauersberger directly evokes this moment of Brahms's motet at the zenith of Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst. Bars 68–78 (shown in Example 3b) are a setting of verse 20 from the fifth chapter of the Lamentations, ‘Warum willst du unser so gar vergessen?’ (‘Wherefore dost thou forget us forever?’). In a rare moment of text repetition, the word ‘Warum’ is heard four times (bars 68–73). Each declaration increases in speed and rises in pitch before finally propelling forwards into a complete phrase. The first two utterances share the same harmonic rhythm and pacing as the refrain of Brahms's motet, and the second echoes Brahms's voice-leading in the upper voice, which falls a major third. In the late wartime and immediate post-war context in which this motet was composed and performed, Mauersberger's isolated instance of text repetition on the word ‘Warum’ might also have echoed a common refrain of disbelief heard across Germany as a first response to the Holocaust and in the aftermath of total defeat.Footnote 96

Example 3b. Mauersberger's Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst, bars 68–78. Text translation: ‘Wherefore dost thou forget us forever, and forsake us for our entire life?’

Rather than progressing from isolation to consolation, both Mauersberger's and Brahms's mourning motets continually circle around the confusion that accompanies loss and grief. The first column of Table 2 above (p. 103) shows that Mauersberger uses the first chapter of the Lamentations most frequently, followed closely by chapter 5. Chapters 1 and 5 are at the extremes in rhetorical and liturgical purpose across the Lamentations as a whole. Mauersberger groups his three complete verses from the fifth chapter together, placing them towards the end of the piece. But he does not conclude his work with the collective expression of consolation of the Lamentation's final chapter. The closing line of Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst returns to the emotional pathos and change expressed in the opening chapter, unravelling the healing trajectory of the Lamentations and returning to a state of distress. Even those who do not know the Lamentation texts and their emotional arch can hear the lack of closure in the musical setting (see Example 4). Mauersberger marks the shift from chapter 5 verse 21 to chapter 1 verse 20 in bars 107–8 with a move from F major to F phrygian, the mode of the opening. He then emphasizes this mode through a series of three plagal cadences in bars 108–18 (first on the tonic, then in the subdominant and again on the tonic). The word ‘distress’ (‘Elend’) is emphasized through four repetitions, drawn out through melismas and cast a full octave in range above the first iteration of the line. The piece concludes with the final line of text repeated in F minor (bars 121–6). Any relief that may have been provided through the Lamentations is temporary, as Mauersberger returns to a musical and liturgical state of distress in the closing bars of the work. Yet here, too, is a crucial final omission from the original text of the Lamentations: chapter 5, verse 22, is also a statement of pain, but one that indicates that God's wrath could be justified.Footnote 97 By closing instead with chapter 1, verse 20, Mauersberger's motet remains focused on individual pity rather than a consideration of consequences.

Example 4: Ending of Mauersberger's Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst, bars 107–26. Text translation: ‘Behold, O Jehovah; for I am in distress!’

The descriptive potential and interlocking associations of Mauersberger's chosen lines indicate a deep familiarity with the text of the Lamentations and speak to a type of Trauerarbeit (‘work of mourning’) that manifests through artistic labour rather than as direct testimony. These associations are further enhanced by Mauersberger's evocations of specific works and practices of funerary music from the Lutheran church. Most notably, Mauersberger represents the firebombing through allegorical associations, a practice seen in the seventeenth-century funerary repertories that the composer both evoked in his compositional practice and performed at the Vespers service. His approach to text and traumatic representation offers a counter-narrative to one of the most prominent and enduring arguments about Germany's response to the air war: W. G. Sebald's Zurich lectures, Luftkrieg und Literatur (Air War and Literature, published in 1999 and translated under the English title On the Natural History of Destruction in 2003).Footnote 98 Sebald's central claim was that Germans had never spoken publicly about the experience of the air war in the wake of the Holocaust and the defeat of the Third Reich. One of the main reasons for this reticence, he argued, was that the air war was considered just punishment for a nation that had facilitated the Nazi's rise to power and did not resist the political party that perpetrated the Holocaust.Footnote 99 Sebald's claims have subsequently been challenged for their historical accuracy,Footnote 100 though his influence on the study of German victimhood has remained significant.Footnote 101 His arguments about expressive blockages can be further nuanced through a focus on music. For while Sebald called attention to the lack of ‘verbal expression’ in response to the air war,Footnote 102 Mauersberger's motet hints at other expressive forms that gave voice to the effects of the firebombing on the post-war population.

The examples I have discussed suggest that the liturgical exegesis of Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst requires a degree of familiarity not only with the Lamentations but also with the Christian calendar. Mauersberger's traumatic allegories trade on veiled associations, some evoked and some strikingly absent, in his musical and liturgical texts. Yet these symbolic meanings were probably beyond the grasp of some, if not many, of the Kreuzkirche's congregants during the Vespers service. By the 1930s, Vespers was as much a sacred music concert as a religious service.Footnote 103 Nevertheless, even if the liturgical polysemy of Mauersberger's text selections did not register among the whole congregation, the local associations certainly resonated in accounts by those present at the 4 August service in 1945. Choristers and congregation alike would have been struck by the parallels between the personal and physical destruction depicted in the Lamentations and the situation that befell Dresden's citizens at the end of the Second World War. With this text, Mauersberger positions himself within a centuries-long lineage of using the Lamentations to ascribe meaning and significance to contemporary catastrophe. These associations were enhanced by Mauersberger's historicist aesthetic, continuing a nineteenth-century custom of ‘historicist modernism’ heard in church music across central Europe in both Catholic and Protestant faiths.Footnote 104 Beyond the rich associations that Mauersberger created between Dresden and Jerusalem in his selected text fragments, his recourse to stile antico, refracted through a late-Romantic lens, positioned the motet in a soundscape that was familiar to the congregation through the Kreuzchor's regular performances. Even though the text expresses a heightened degree of distress, the overall musical setting might have offered the congregation a temporary sense of security in an environment of traumatic disarray.

Returning to the Altstadt

With a deeper understanding in mind of Mauersberger's musical rubble-to-ruin transformation of the firebombing created in Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst, I now return to the site of performance to consider how the multiple associations heard in Mauersberger's motet were enhanced within the space of the Kreuzkirche. Mauersberger's text is already visual in nature: several lines of the Lamentations have been repurposed to describe the desolate cityscape available to us through ruin photography collections such as Peter's Dresden: Eine Kamera klagt an.Footnote 105 The ‘visual experience’ of the firebombing is intensified as the imagery in Mauersberger's motet, performed in a heavily damaged space, takes on concrete form amid the remains of the church. This was not lost on congregants at the première. One member of the congregation was Karl Laux (1896–1978), a music critic who spent most of his career in Dresden, facing problems during the Third Reich for not joining the Nazi Party. He quickly professed his support for the Soviet authorities after the Second World War and went on to have a successful career in the GDR.Footnote 106 Laux reflected on the première in his 1977 autobiography, noting that the Lamentations were so pertinent to the present moment that ‘they could have been written in 1945’.Footnote 107 Yet the première transformed both piece and setting in a crucial way. In contrast to the ‘deserted city’ in the opening lines of the Lamentations (and, by extension, in the opening of Mauersberger's motet), the first post-war Vespers service brought a large congregation back into a building that stood on the south-west corner of the Altstadt. The music and its liturgical context provided one of the first opportunities to mourn the firebombing collectively within a space that held many markers of this traumatic event. Performed to a congregation that Laux calculated to be around 3,000, the première actually reversed the desolate scene in the opening lines of Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst.Footnote 108

This transformation is particularly important when considered in the light of the specific activities that took place in the Altstadt in the late wartime and early post-war months. Reports from cross-sections of the city's population indicate that survivors were continuing to find bodies of the deceased amid the damaged buildings for months after the attack.Footnote 109 To avoid a sanitary crisis, city officials brought in a commander of the Schutzstaffel (or the SS, the paramilitary organization in the Third Reich primarily responsible for enforcing racial policies), who had experience in organizing the disposal of human remains at Nazi concentration camps, to coordinate the removal of human and physical waste left in the wake of the aerial bombing.Footnote 110 Beginning two weeks after the bombing, a funeral pyre was erected in the Altmarkt to clear the debris, which burnt for a week in April 1945. The decision to conduct this mass cremation left a deep emotional scar on Dresden's cityscape, seen in the number of references to this event in literature of the post-war years. Thomas C. Fox, for example, notes the recurring reference to the Altmarkt burnings in both official newspapers and literature beginning in 1949 and continuing into the 1950s and 1960s. This evidence often displays problematic elisions between victims of the Holocaust and victims of the air war in local discourse, echoing a larger concern with issues of German victimhood following the war.Footnote 111

The Holocaust was not discussed openly in the early post-war months, but it inflected the non-verbal ways in which Dresden's citizens responded to the firebombing in the wake of the war. The Altmarkt's associations with mass death made it a particularly difficult space for musical performance, and singing within this space further contorted Dresden's ruin iconography. Süss describes how the escalating sanitary crisis left ‘no room for mourning’ in the city, because the priority was to find and dispose of the deceased.Footnote 112 His comments on the situation in Dresden draw attention to the lack of space for grief in the aftermath of the firebombing, particularly as information about German concentration camps was becoming increasingly public at the end of the war. Across Germany towards the end of the war, mass burials presented a challenge to traditional death rituals and the desires of survivors to bury their family members in individual ceremonies.Footnote 113 In her study of mortuary practices in Berlin, for example, Monica Black describes a post-war burial crisis of insurmountable proportions, noting the anxieties that emerged around anonymous burial rituals.Footnote 114 Anonymous death went against many prior models of grieving practised in Germany since the Reformation. Most immediately, it was anathema to the conceptions of ‘proper burial’ during the Third Reich, where anonymous death was reserved for those excluded from the Volksgemeinschaft. Footnote 115 In Dresden these associations were even more powerful and direct because the city authorities had brought in an SS commander precisely on account of his experience in coordinating mass burials in these spaces of Nazi discrimination and exclusion.

Mass burials also challenged the visual ruin code of distanced sorrow that was central to Dresden's post-war reputation as ‘a city of civilian victims’. In Peter's Dresden: Eine Kamera klagt an, for example, images of the Altmarkt mark a dramatic departure from the wordless before-and-after ruin aesthetic that runs throughout most of the photobook. Rather than uncaptioned empty spaces and destroyed buildings, the photographs of the Altmarkt that Peter presents in his essay are of deceased bodies piled on the funeral pyre with the caption ‘Altmarkt – Wochenlang wurden Tote gestapelt und verbrannt’ (‘The Old Market Square – for weeks the dead were piled up and burnt’).Footnote 116 Far from a distant ruin aesthetic that removes the causes of the destruction and focuses on its effects, the photographs of the Altmarkt in Dresden: Eine Kamera klagt an echo a different mode of representation that German citizens were attempting to avoid confronting entirely: pictures of Nazi concentration camps released on accusatory posters by occupying forces in an effort to force Germans to acknowledge their guilt for the Holocaust.Footnote 117

Within this complex emotional environment of the immediate post-war months, the Kreuzchor's Vespers service was one of the first efforts spatially to reclaim a site that had been doubly cast as a space of catastrophe in the firebombing: first through the intensive attack on the Altstadt on 13–14 February, and then by being used almost two months later for gathering and cremating the bodies of those who had died. The situation in Dresden mirrored that in other cities firebombed earlier in the war, where local officials had encountered considerable resistance to non-normative burial practices. Süss describes how ‘many relatives looked for a way of making up for the absence of a grave’. He draws attention to the situation in Würzburg, where:

There was much dispute over whether the authorities were allowing private citizens to bury their relatives in individual graves after the severe bombing of 16 March 1945. […] While families insisted on their right to decide on the form the funeral was to take, the authorities, mindful of the need for rapid burial and the threat of disease, imposed restrictions.Footnote 118

As we have seen, the situation in Dresden was even more acute, and such decisions were immediately taken out of the hands of individual residents.

Nevertheless, some dimensions of honourable funerary rituals could be adapted to the contemporary conditions, and it seems that the organizing forces behind the Gedenkvesper service made sure these elements were performed on the night of 4 August 1945. Looking back at the musical choices (shown in Table 1 above, p. 91), the fact that most of the works performed were dedicated to a specific section of the Kreuzkirche community suggests a desire to honour the dead by collective if not individual name. In lieu of a proper burial, those who lost their lives in the Dresden firebombing were commemorated through music. Here, too, there are historical and locally significant precedents from prior traumatic events. As Bettina Varwig has demonstrated in her work on Schütz, the Thirty Years War had a significant effect on Lutheran understandings of the ars moriendi, as musical dedications served in some contexts to mitigate the anonymity of death induced by war or plague. ‘Musical and verbal tributes to a deceased person’, Varwig argues, ‘set their body and soul apart from the mass of corpses on battlefields and graveyards.’Footnote 119 As a historic point of national tragedy, the Thirty Years War was evoked in wartime sermons to create allegories with which religious figureheads could make sense of the current situation through a pre-existing frame of reference.Footnote 120 In a parallel to these early modern precedents, the order of service for Vespers on 4 August 1945 countered the anonymity of death to the extent that it was possible by dedicating individual musical works to specific communities of the deceased.

Conclusion

Amid the precariousness of the early months following the war, Mauersberger's motet provided an aesthetic frame for confronting the circumstances of the post-war world for the composer, choir and congregation alike. Performing this piece within the context of a liturgical service in Dresden's Altstadt produced ambiguous and often questionable overlaps between sorrow, guilt, punishment and victimhood that echoed through Dresden's rubblescape, picking up on the multilayered memories that saturated this space. Through music, Mauersberger voiced multiple, but by no means comprehensive, responses to the moral and physical ruin facing German citizens at the end of the Second World War. Both Mauersberger's motet and the circumstances surrounding its première are steeped in musically, liturgically and geographically long-established codes of mourning. This repurposing of local conventions participates in a mode of responding to the war that relies heavily on adapting long-standing customs to confront the present catastrophe. My analysis of Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst reveals how Mauersberger participates in the scopic fascination seen in other artistic media in his compositional process, while avoiding possible associations with German guilt that were starting to surface in 1945. Examining Mauersberger's artistic response to the firebombing within the context of the Kreuzchor's wartime activities illustrates the ways in which his musical and liturgical allegories functioned in both therapeutic and ethically questionable ways, often at the same time. When performed amid the ruins of the Kreuzkirche, Mauserberger's motet enhanced the temporal aspect of the rubble-to-ruin transformation seen across responses to Dresden's desecrated landscape.

By examining a single work and its first performance, I have suggested some correctives to current scholarship on national memory of the Dresden firebombing. Too frequently, scholars have drawn attention to the monolithic propaganda of the SBZ and later the GDR, rather than accounting for how discourse surrounding the firebombing was fundamentally shaped by human experiences of the wartime years, and how it changed throughout the 40-year history of the GDR. A focus on musical activities that took place before the onset of the cold war demonstrates the ways in which this medium could provide a temporary anchor for expressing reactions to the firebombing, even if those responses were difficult to formulate verbally. Mauersberger's motet and its first post-war performance reveal the unique ways in which music participated in the artistic trends that flourished in the early post-war months. By understanding ways in which artistic expression served as an outlet for the shifting emotional surplus of the immediate post-war period we can also nuance our understanding of the more overtly political uses of this music during the cold war. The tension between selective confrontation and selective concealment that takes place in this motet had implications for how the piece and its performance space functioned in the years after the firebombing. It took significantly longer to clear wartime rubble in East Germany than in West German cities, and in the case of Dresden's Altstadt some sites were not cleared until after reunification. Instead of the complete reconstruction carried out in some cities in the West, Dresden's ruin became highly charged ideologically, with spaces of the Altstadt serving in the GDR as a Mahnmal (‘warning monument’) for Allied barbarity. But as Mauersberger's motet and its first performance suggest, before rubble could be ideological, it had to be functional. The aesthetic frame and selective engagement with Dresden's destruction created in Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst reveals that music was a key medium in which this transformation could take place.

Acknowledgements