Before Caruso came I never heard a voice that even remotely resembled his. Since he came I have heard voice after voice, big and small, high and low, that suggested his, reminded me of it at times even forcibly.Footnote 1

With these poignant words, the American composer Sidney Homer sums up the contribution of Enrico Caruso (1873–1921) to the development of an innovative type of vocalism. But however remarkable Caruso’s achievement may have been, it was not an isolated phenomenon. He was both the figurehead and the paradigm of that profound transformation through which the Italian tradition of operatic singing became ‘modern’. In what follows, I seek to identify and explore the formative elements of this multifaceted ‘modernity’, a phenomenon that formed the basis for the way in which operatic singing has been understood and judged ever since.

The new aural dimension which Homer perceived in Caruso’s sound depends on a novel conceptualization of the operatic voice. Roger Freitas has clearly shown that a move towards darker and heavier systems of singing in contrast with a previous ‘timbral ideal […] substantially brighter and thinner’ started in the final decades of the nineteenth century.Footnote 2 In his exploration of essential technical and expressive procedures of Verdian singing style including timbre, agility, pronunciation and vibrato, Freitas was building on the groundbreaking work of Will Crutchfield, who in the 1980s first brought to the attention of scholars the profound differences between the performance practices of singers in Verdi’s time, as revealed in early recordings, and those of today’s singers.Footnote 3 In the present article I argue that the changing aural conception of the operatic sound, as perceived by Homer in the voice of Caruso, was more significant than is generally thought.

My contention is that at the turn of the twentieth century operatic voices lost the bel canto ideal of ‘pure’ tone quality and took on an irreversible gendered connotation and an erotically charged expressive force. In this connection I also put forward the hypothesis that pivotal to all these changes (in terms of both the aural conception of the operatic voice and performance practices) was the preservation of the same timbral quality from the top to the bottom of a singer’s range (which I define as ‘total timbral consistency’). I suggest that all these elements in combination elicited those impressions of ‘naturalness’ and ‘spontaneity’ that were attributed to the singing of Caruso from the beginning. Although opera-goers today may not be aware of it, these are the criteria by which they judge a voice every time they visit the opera house. And yet before this transformation, different criteria of vocal production held sway. As my close reading of a large number of late nineteenth-century vocal treatises suggests, a timbral divide between the different vocal registers was considered not only unavoidable but also desirable. In line with this conviction, early recordings evince that singers deployed a technique of different timbres for different registers, supporting the idea that audiences would regard the registral timbral divide as an ordinary feature of singers’ performance.Footnote 4

This whole transformative process is entangled with the rise of verismo, which redefined the operatic and, more generally, the cultural landscape of fin-de-siècle Italy. The ‘new’ characters of verismo operas (a wide array of types, from the peasants of Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana to the intrinsically bourgeois artists of Puccini’s La bohème) differ from their Romantic counterparts in every possible way. Whereas the personages of melodramma were caught in a continuous tension between moral values and personal desires, with the ‘true-to-life’ psychologies of verismo this conflictual dynamic disappears. The space left empty by lofty ethical ideals is filled with sensual love and brutal violence in the highly sexualized environment of verismo operas. These feelings cannot be expressed either through the florid style of singing or through the ‘pure’ tone quality in which singers of Caruso’s generation were trained. In order to portray credibly on stage the new dramatis personae, turn-of-the-century singers needed to design an entirely new set of skills.

The collective efforts made by many prominent Italian singers of the period to achieve the ‘modern shift’ have long been overlooked by scholars. With this article I make a first attempt at filling this lacuna, which is a disabling limitation not only for musicologists with a specific interest in vocalism but also for historians who read musical events as ‘signifiers’ of a wider cultural context (and vice versa). I have reconstructed the journey of these turn-of-the-century singers by following the paradigmatic vocal evolution of Caruso, as revealed in his impressive recording legacy, critical reception and the various opinions expressed by his singer colleagues. In order to put this material into its historical context, I have both considered the role that verismo played in this important transition of Italian operatic singing and compared Caruso with two other outstanding Italian tenors of the period, Alessandro Bonci (1870–1940) and Giovanni Zenatello (1876–1949). Finally, because the availability of a specialized and agreed lexicon is a precondition of any discourse of vocal performance, I have throughout interwoven ideas from historical treatises with those of modern voice science, in order to provide a set of reasonably consistent terms for the analysis of those aspects of the recorded performance which are essential to this discussion.Footnote 5

The ‘natural’ singing of Caruso: some evidence

From the beginning of his career, Caruso’s singing was frequently described with words such as ‘spontaneous’ and ‘natural’. Giovanni Battista Nappi, a writer for the newspaper La perseveranza, commented, after Caruso’s début in Massenet’s La Navarraise (1897) at the Teatro Lirico Internazionale in Milan, on the tenor’s ‘homogeneous voice’ and his ‘penetrating, full and spontaneous timbre’.Footnote 6 His interpretation of the role of Cavaradossi (in Puccini’s Tosca) was welcomed for his ‘marvellous voice, spontaneous, mellow yet powerful throughout his entire range’.Footnote 7 The distinct nature of Caruso’s singing did not escape the critic of Il gazzettino, who commented on the ‘new creation he made of the character of Cavaradossi’, a fact that was ‘realized by those who had heard Tosca sung by other tenors, such as Borgatti and Giraud’.Footnote 8 Towards the end of 1899, the newspaper Italia compiled a detailed commentary on the characteristics that distinguished Caruso’s ‘natural’ and ‘modern’ vocalism from that of two other outstanding tenors of the era: the older Fernando De Lucia (1860–1925), who was by then something of a living myth, well known to contemporary audiences for both his bel canto and his verismo performances, and the young Giuseppe Borgatti (1871–1950), who was making a name for himself as a Wagnerian singer.Footnote 9 Reviewing Caruso in the role of Osaka in Mascagni’s Iris, the journalist of Italia, after praising his voice as ideally suited to modern operas, compared De Lucia and Borgatti in the same role:

The declamation of De Lucia – too mawkish to be suave, exaggerated in its affectation, making excessive use of falsetto, and creating explosive unbalanced effects in the middle range – recalled the other Osaka, that of Borgatti, to whom the part is so little suited because of the nature of his vocal organ, and who overplays the effects of falsetto and mixed voice.Footnote 10

The image that these and many other reviews of the early Caruso might suggest is of a singer who may have been seeking a more chest-orientated way of uniting the lower and upper ranges of his voice. This tendency, however, could already be detected in several other tenors of the period, such as Eugenio Galli (1862–1910), Gino Martinez-Patti (1866–1925) and Mario Guardabassi (1867–1952), all a few years older than Caruso. All these singers displayed some of the characteristics that were attributed to Caruso’s singing, which this article will consider in detail. For instance, in Guardabassi’s recording of Mascagni’s Siciliana (from Cavalleria rusticana), some of his repeated A♭4s show the full-bodied tone quality of the mature Caruso – while the middle range (C3–F4) remains rather light and bright, a characteristic inherited from previous styles of singing, as we shall see. Similar observations could be made of Martinez-Patti’s recording of the same solo and Galli’s recording of the Miserere from Verdi’s Il trovatore. Footnote 11

The fact that at this early stage of Caruso’s career we cannot rely on any recorded evidence makes it difficult not only to reconstruct his early technical development but also to reconcile what we read in reviews, memories, biographies with what we can hear in Caruso’s very first recordings from a few years later. Many interesting hints about Caruso’s technical evolution before the advent of recording are contained in Pietro Gargano and Gianni Cesarini’s biography (see above, note 6), where unfortunately the authors rarely give sources for their quotations. For instance, we are told that during the rehearsals of Fedora in November 1898, Caruso seemed to have exclaimed ‘Aggio truvato!’ (‘I have found it!’) while singing his solo ‘Amor ti vieta’, in which the tenor line lies mostly around the passaggio (that critical area of the vocal compass where the singer has to negotiate the transition between registers).Footnote 12 We can infer that he ‘found’ a way of blending the sounds of the middle range (the fifth A3–E4 in this specific aria) with the high G4s and the climactic A4, given that the solo’s tessitura moves constantly around this area of the voice. A testimony that could support this assumption comes from the soprano Luisa Tetrazzini, who met Caruso on stage for the first time at the end of 1898 in the imperial theatre of St Petersburg, where they were both singing in Puccini’s La bohème. She tells us:

As a youth of twenty years […] I recall the difficulty he had even with such ordinary notes as G or A. He always stumbled over these, and it annoyed him so that he even threatened to change over to […] baritone […] During an opera season in St Petersburg, I sang with him for the first time […] I saw what progress he had made […] The impertinenza with which he lavishly poured forth those rich, round notes. It was the open voce napolitana, yet it had the soft caress of the voce della campagna toscana […] I placed him there and then as an extraordinary and unique tenor. From top to bottom his register[s] [were] without defect.Footnote 13

The ‘impertinent’, ‘rich, round’ notes that were detected by Tetrazzini in 1898 had to wait four years (until April 1902) to leave a verifiable trace in the first ten wax discs recorded by Caruso in a hotel room in Milan. Among the ‘round’ pitches that can indeed be heard in these tracks, the contemporary ear is struck by too many notes that sound ‘whitened’ and excessively ‘open’ (two terms which critics indifferently associated with a colourless quality of the vocal sound, and that will be defined below in relation to the lexicon), such as those present in the starting phrases of the Siciliana from Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana and in several passages of ‘Una furtiva lagrima’ from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore. Footnote 14 In other words, these sounds are not yet completely developed, as Nellie Melba underlined in her memoir:

Though his singing was spontaneous and natural, I do not think that in those days [1902] he was so fine an artist as later on, when perhaps his voice was not so wonderful. It makes me sad to think that the culmination of his art should not have coincided with the greatest years of his voice.Footnote 15

The repeatedly expressed opinion that Caruso’s singing was ‘natural’, at a time when he was still dependent on heady tones and light vocal production, may seem puzzling to us, and can be explained only through a comparison of his singing with that of contemporary tenors.Footnote 16 For instance, the use that Borgatti made of falsetto, fioriture (ornamentation) and mezze voci (half voice) in the verismo part of Osaka (one of Mascagni’s more exacting roles) was considered perfectly appropriate in that context by the critic of Il mondo artistico, Nino Creso, who praised the singing of the young tenor enthusiastically.Footnote 17 Notwithstanding the repeated references by critics to the falsettos of Borgatti, his first recordings from a few years later (1905) display a rather muscular approach to the upper range, comparable to that of Giovanni Cesarani in his 1900 recording of Puccini’s ‘Tra voi belle’ (from Manon Lescaut) and to that of Fiorello Giraud in his 1904 recording of ‘La fleur’ from Bizet’s Carmen. Footnote 18 In all these recordings, the similarities with some features of Caruso’s middle-period vocalism are evident. However, as argued in the final section of this article, the extent to which these singers embraced heavier models of vocalism was tempered by their loyalty to the long-established tradition of bel canto.

The opinion expressed by Creso in relation to Borgatti’s Osaka is not surprising if one considers that in the decades immediately preceding those under discussion here even Adelina Patti’s singing, so profoundly different from that of Caruso, was described as ‘natural’ by critics and audiences alike.Footnote 19 This fact reminds us that terms such as ‘natural’ and ‘spontaneous’ are value-laden and not simply descriptive, and therefore change their meaning as the tastes and values of a culture change. According to the tastes of a nineteenth-century audience, the singing voice was judged to be ‘natural’ if the vocal production was perceived as light and effortless. That perceptions of ‘naturalness’ were shifting in the period under consideration is also revealed by the opinions that American critics expressed in relation to Caruso’s vocalism at his Metropolitan Opera début (1903). For Richard Aldrich, the critic of the New York Times, Caruso’s performance in the role of the Duke from Verdi’s Rigoletto

made a highly favorable impression […] His voice is purely a tenor in its quality of high range, and of large power, but [it is] inclined to take on a ‘white’ quality in its upper range when he lets it forth. In mezza voce it has expressiveness and flexibility, and when so used its beauty is most apparent.Footnote 20

William James Henderson, from The Sun, wrote:

Caruso, the new tenor, made a thoroughly favorable impression […] He has a pure voice, without the typical Italian bleat. Caruso has a natural and free delivery and his voice carries well without forcing […] His clear and pealing high notes set the bravos wild with delight, but connoisseurs of singing saw more promise for the season in his mezza voce and his manliness.Footnote 21

Even allowing for the subjectivity which inevitably colours the act of criticism, such views provide evidence of a widespread and increasing approval of ‘chesty’ and full-bodied sounds. In this context a ‘white’ quality in the upper range, as it can be heard in many of Caruso’s early recordings, was regarded as displeasing, while ‘pealing high notes’ evoked a welcome impression of ‘manliness’ – the more dark and ‘virile’ the sound, the better. It is also worth noticing that critics allowed for national differences in the perception and appreciation of vocal quality. In a ‘pre-performance essay’, Aldrich discussed Caruso’s critical and public reception at the Metropolitan Opera House over the singer’s first two seasons in that theatre (1903/4 and 1904/5):

And is it not time to raise some sober-minded queries about the way Mr. Caruso is using his voice and the kind of art and expression he is employing in these days? It was noticed at his first appearances here two seasons ago that he showed sometimes a tendency to use the ‘open’ or ‘white’ voice that is beloved of Italian tenors and admired by Italian listeners. But it was not a fixed characteristic of his singing, and he very soon proved that he could produce tones in the purer and better way that lovers of singing hereabout prefer. And how lovely they are when he so produces them!Footnote 22

Only when comparing Caruso’s first discs (April 1902) with his later recordings of the same material are we able to appreciate the long and continuous technical evolution he underwent. Caruso spent approximately 11 years (1895–1906) on the elaboration of his passaggio to the upper range.Footnote 23 This process (and its result) not only shaped his vocalism and style, but also informed those ideas of ‘naturalness’, ‘spontaneity’, ‘modernity’ and ‘manliness’ which, as the evidence demonstrates, were attributed to Caruso’s singing. In order to understand this important vocal evolution from a more analytical perspective, I will refer to a number of selected passages from Caruso’s recordings. Because this discussion needs a specialized lexicon, I need now to introduce the reader to some key technical terms. This task has a more than merely taxonomic interest; it reveals the existence of widely shared tenets of good singing among vocal pedagogues in fin-de-siècle Italy.

The vocal registers and the strategies for uniting them in turn-of-the-century pedagogical writing

At the time of Caruso, there was widespread agreement that male voices consist of two registers: the ‘chest’ and the ‘medium’ (also variously named ‘mixed’, ‘second’ or even, as in the case of Manuel García II, ‘falsetto’).Footnote 24 Voice teachers of the period generally assert that when a singer passes from one register to another the timbral quality of their voice changes. The numerous treatises that I surveyed (more than 70 volumes) are adamant in this respect, and the idea that trained singers could preserve a seamless tone colour from the top to the bottom of their vocal compass is decisively excluded. The transition between registers must of course be even, and in the series of around three or four notes that constitute the border between registers (the passaggio) any possible break must be artfully smoothed over; nevertheless, a change in tone colour will inevitably occur at some point while the singer ascends the scale. There are numerous examples of voice teachers preaching this fundamental tenet of vocal technique, but it is Francesco Lamperti who most clearly explained the different qualities of the sounds of different registers. Under the title ‘The Various Registers of the Voice’ in his practical method (set out in the form of a dialogue between teacher and pupil) he gives his view:

Q. Are all the notes of the voice of the same quality?

A. No; only those which belong to the same register; the others, no matter how even the voice may be, differ from each other, as does the mechanism of the throat in producing them.Footnote 25

Lamperti noticeably associates the term ‘register’ with a ‘mechanism of the throat’, clearly drawing from the work of Manuel García II, the pre-eminent vocal teacher of the nineteenth century, whose writings on vocal physiology and singing pedagogy (prolifically produced and revised over a period of approximately 60 years, from 1841 onwards) constituted part of the basic shared knowledge of voice teachers by the latter part of the nineteenth century. It was García who famously first associated the definition of ‘register’ with a physiological action in a treatise of vocal technique (A Complete Treatise on the Art of Singing, 1841):

By the word register, we understand a series of consecutive and homogeneous tones going from low to high, produced by the development of the same mechanical principle, and whose nature differs essentially from another series of tones equally consecutive and homogeneous produced by another mechanical principle. All the tones belonging to the same register are consequently of the same nature, whatever may be the modifications of timbre or of force to which one subjects them.Footnote 26

The ‘mechanical principle’ is central to García’s definition, and was the determining factor in what David C. Taylor identified as the ‘mechanical’ turn of vocal pedagogy in the mid-nineteenth century, when scientific knowledge of the vocal organs and their workings rapidly became the foundation of any method of instruction.Footnote 27 The importance of this ‘turn’ did not escape the attention of post-García voice teachers, some of whom consistently acknowledged in their writings the groundbreaking contributions of the great Spanish pedagogue. For instance, Beniamino Carelli, one of Italy’s most respected singing teachers, claimed that García ‘dared to make a science out of the art of singing’.Footnote 28 The adjustments of the vocal cords throughout the compass of the voice were established as the primary causes of vocal production and register formation.Footnote 29 Modern voice science has explained these physiological mechanisms with some degree of accuracy.Footnote 30 The pitch of a note produced by the voice is ‘determined by the tension (that is, the elasticity) and the thickness (the vibrating mass) of the vocal folds […] thus, when a low-pitched sound is produced, the vocal folds are relaxed, thick and short. For high-pitched sounds they are tense, thin and long’.Footnote 31 The pitch thus depends ultimately on the tension and thickness of the vocal folds, and the registers of the voice originate from the different ways in which vocal folds vibrate on a particular note. Referring to the results of investigations carried out in 1970,Footnote 32 Johan Sundberg explains that the terms ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ for classifying the several vocal registers were justified on the basis of the different behaviours in the functioning of the laryngeal muscles when producing different registers.Footnote 33 In her study on register transition, Natalie Henrich Bernardoni describes in detail the different actions of the vocal folds in the several registers. The multilayered structure of the folds – they consist of a cover (mucosa, epithelium and superficial layer of vocal folds), a transitional layer (intermediate and deep layers of the vocal ligaments) and the main body (vocal ligaments) – is observed to vary as follows:

[In heavier registers] the vocal folds are thick and they vibrate over their whole length […] Vibrating mass and amplitude are important. The vocal fold body is stiffer than the cover and transition. Vocalis muscular activity is dominant over cricothyroid. Both activities increase with pitch. Closed phase is often longer than open phase [… In lighter registers, instead,] the vibrating mass and amplitude are reduced […] All the vocal fold layers are stretched, and the collagenous fibres in the vocal ligament are the stiffest of all the layers. Cricothyroid muscular activity is dominant over vocalis. The open phase is always longer than the closed phase.Footnote 34

To put it simply, when a singer shifts from a heavy to a lighter register, not only does the thickness of the cords diminish but also a reduction of the overall laryngeal muscular activity is always evident. Because some of the pitches of the singer’s compass are common to both registers (the notes of the passaggio area), they can be produced with either the heavy (chest) or the lighter (medium) register, extending the heavy system of vocal production of the lower sounds upwards to the higher notes (and vice versa). Therefore, the balancing and joining of registers can be achieved according to systems of heavier or lighter registration – where by the word ‘registration’ I mean the actual manoeuvre of uniting and balancing the registers. García’s pivotal strategy for extending the heavier system of registration upwards is the technique he termed (in French) sombre (dark) timbre. In this technique, singers increase the roundness of the vowels as they ascend a scale and reverse this mechanism when descending it:

The apparent equality of the notes in the scale will be the result of actual but well-graduated inequality of the vowel sound. Without this manoeuvre, the round vowels which are suitable to the higher notes would extinguish the ringing of the middle and lower notes, and the open vowels which give éclat to the lower would make the higher notes harsh and shrill.Footnote 35

The sombre timbre is as an essential pedagogical aid which affects (and modifies) the shape of the pharynx, a tube-shaped section of the vocal apparatus extending from above the larynx up to the oral cavity. The pharynx,

being able to elongate or to shorten itself, to broaden or to narrow itself, to take the form of a slight curve or to break into a right angle, and finally to maintain any of the numerous intermediary forms, fulfils wonderfully the functions of a reflector or a megaphone.Footnote 36

If the singer rounds a vowel when ascending the scale, the pharyngeal tube becomes lengthened and (to use García’s language) ‘right-angle shaped’, with a dropped larynx and a raised soft palate, resulting in the sombre timbre. The tube can assume many other shapes which allow for the different vocal timbres to be produced, but it is the bright (clair) one that, produced by a ‘curvilinear form’ with a higher laryngeal position than that described for the sombre timbre and a dropped soft palate, constitutes the other main timbre of the voice.

Much confusion has arisen from the fact that the original French term clair used by García in his École de Garcia: Traité complet de l’art du chant (1847) has been translated into English as ‘open’. The adjective ‘open’ generally has a positive connotation for English-speaking voice teachers, who in current practice describe an open sound as characterized by a raised soft palate and a lowered larynx, creating an ‘open’ space at the back of the mouth.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, a vocal tract so shaped corresponds to what García defined as the dark (or sombre) timbre. To add uncertainty to the linguistic issue, the use that some English-speaking critics historically made of the word ‘open’, as we saw above, confirms that far from signifying an open space at the back of the mouth, they were, in fact indicating quite the opposite. In the critical context, moreover, the term ‘white’ was frequently treated as synonymous with ‘open’. Likewise, in Italian pedagogical and critical language, an open (aperto) timbre describes a raised larynx in a flat soft palate. I follow this latter usage when I analyse the recordings which are presented later in this article.

To summarize, while the vowel modification determines a progressive darkening of the voice as it ascends the scale, the dark (sombre) timbre which is obtained in this way elongates the vocal tract (lowered larynx and raised soft palate). In addition to these general rules, which can potentially be applied to the training of any singer, each voice presents a particular potential to be ‘registered’ in specific ways. This depends on a number of factors, including the weight of the voice (dramatic, lyric or light) and specific characteristics of the physical vocal apparatus. Moreover, the interaction between innate and cultivated elements of vocal registration produces what is perceived as a singer’s individual colour and can produce a wide variety of results. A heavy voice could therefore yield a dark colour because the singer consistently resorts to procedures of ‘covering’ (a term which I use as synonymous with García’s ‘darkening’) or because that is the natural colour of that particular voice, or a combination of the two. If the singer deploys less intensive covering, the voice will keep its weight, but will sound brighter. The same applies to light voices, which can also possess an innate dark colour, a quality which may or may not be enhanced by specific registral choices.

In García’s view, the dark timbre is only one of the possible colours to which the singer can resort for ensuring variety of expression in the musical phrase.Footnote 38 Consistently with this line of thinking, post-Garcían voice teachers also discuss other timbres of the voice, such as the rotondo-chiaro (bright-rounded) and rotondo-scuro (dark-rounded), considering the different lengths in which the vocal tract can be elongated by creating each of these timbres. Such different elongations depend, in turn, on the diverse degree by which the larynx is lowered and the soft palate is correspondingly raised.Footnote 39 The preference that vocal pedagogues express for systems of lighter registration is understandable when one considers the greater effort the singer must make when supporting the voice in the heavier registration. It is, therefore, not surprising that voice teachers would exhort the singer not to draw the heavy register (chest) continuously upwards (through procedures of laryngeal lowering and vowel modification), but rather to ‘carry down’ the lighter one (medium). Both Lamperti and Shakespeare suggest that male voices switch to the second register on relatively low pitches, and the same procedure is also recommended by Beniamino Carelli and Alessandro Guagni-Benvenuti.Footnote 40

However, the different colours in the two registers which the application of this procedure would yield – and with them the impression that the light-weighted upper tones might lack manliness – are not perceived as an issue. Considered as physiological phenomena, unavoidable and immanent within the tonal nature of each register mechanism, timbral differences between registers were perceived as a resource which allowed the skilful singer to access a wider palette of colours. The comparative reading of late nineteenth-century vocal treatises shows that singing teachers’ primary aim was the cultivation of a ‘pure’ tone quality, where ‘pure’ stands for the proper character of a pitch produced only through the mechanism of the register to which it belongs. Moreover, the striving for this purity would reveal the unique tonal quality embodied in the physical and psychological makeup of a particular singer. This was rooted in the aesthetic belief that expressivity was indissolubly linked to the ‘true’ nature of the individual vocal sound. The voice is the expression of a person, not of a type. As Doria Lena Levine, one of the last pupils of Lamperti, underlines, the great Italian teacher

first of all […] stood for purity of tone, and for never sacrificing quality for quantity […] He believed that if modern music demands that tonal beauty shall become a secondary consideration, that it makes of singing a hybrid, inconsistent, degenerate art, and that the sooner we come down to plain speech the better.Footnote 41

In an age when the conceptualization of the vocal sound was not yet firmly tied up with rigid expectations of its gendered qualities, singers had greater freedom with respect to ways of registering the voice, which allowed for a lesser degree of standardization. In this sense, Homer’s remarks on the voice of Caruso, quoted at the beginning of this article, might signal the starting point of a process in which voices began to coalesce around a ‘model’. This is not to say that after Caruso, tenors’ voices were any less individual or distinct in sound, as their innate vocal timbre would of course distinguish them from each other; but it might suggest that at the level of voice production, the dominance of the Caruso model exerted a levelling or homogenizing effect on the individual vocal personality of the twentieth-century tenor, as compared with his historical predecessors.

With these basic terms defined, I turn now to the discussion of specific elements of the recorded performance. There are two essential points to be made at this stage. First, all recordings of the early Caruso (up to 1905) attest to the habit of producing the two registers with different colours, endorsing the content and recommendations contained in pedagogical writing.Footnote 42 Secondly, the working out of an aesthetic of total timbral consistency which progressively erased previous practices seems to have been a conscious choice, which one can trace through a long process of trial and error, as the comments of the most attentive critics also indirectly confirm.

Overcoming timbral inconsistencies: how ‘modern’ singing was born

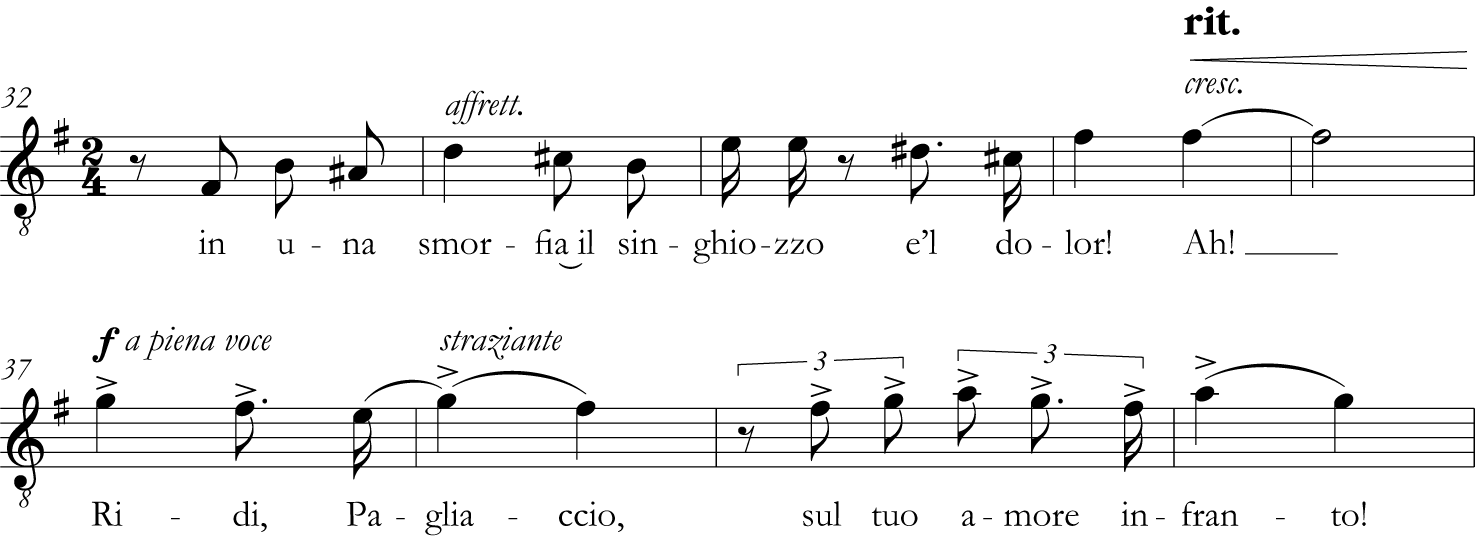

Caruso’s 1902 recording of ‘Una furtiva lagrima’ from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, a lyric role that the tenor performed until the end of his career, reveals that the tone quality of the notes below the passaggio is generally much darker and fuller than that of the passaggio notes and above.Footnote 43 In some sections this is strikingly evident, such as at bars 20–2 (see Example 1), where the B♭3 and the D♭4 are considerably darker than the long F4s.Footnote 44 Moreover, the quality of these F4s changes throughout. The first F4 on the word ‘vo’ is attacked with a rather ‘open’ and light sound which is progressively modified as Caruso approaches the end of the note. It could be suggested that this adjustment is produced through a procedure of slight vowel modification which extends to the first syllable of the subsequent word ‘M’a-ma’. Again, the same effect of tonal divide is audible at ‘I palpiti’ (F4–C4) in the second verse, where the C4s are much darker than the F4s (see Example 2).Footnote 45

Example 1 Gaetano Donizetti, L’elisir d’amore, melodramma in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani, vocal score (Milan: Ricordi, 2005). Romanza, ‘Una furtiva lagrima’, Act 2, bars 20–2 (vocal part only).

Example 2 Donizetti, ‘Una furtiva lagrima’, bars 34–6 (vocal part only).

In the 1904 recording of ‘E lucevan le stelle’ from Puccini’s Tosca, a similar approach to the passaggio notes is displayed.Footnote 46 On the phrase ‘Oh! dolci baci, o languide carezze’ (see Example 3), Caruso does not even attempt to cover the E4–F♯4, but he releases the voice on the flow of the lighter registration, avoiding any elongation of the vocal tract.Footnote 47 Where the ‘sweet kisses and languid caresses’ are – to use Aldrich’s expression quoted above – ‘white’, Caruso attempts the two ascents to the top A4s in a muscular fashion (see Examples 4 and 5).Footnote 48 It seems that he was seeking a way of releasing more vocal power, but without success. In 1904, Caruso the singer fails to match the intentions of Caruso the creative interpreter, as he approached the top notes with a relatively lowered larynx but without elongating the vocal tract to its full capacity.Footnote 49

Example 3 Giacomo Puccini, Tosca, melodramma in three acts, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, vocal score based on the editon by Roger Parker (Milan: Ricordi, 1995). ‘E lucevan le stelle’, Act 3, bars 196–7 (vocal part only).

Example 4 Puccini, ‘E lucevan le stelle’, bars 198–200 (vocal part only).

Example 5 Puccini, ‘E lucevan le stelle’, bars 208–9 (vocal part only).

This observation is confirmed when the 1904 recording of ‘E lucevan le stelle’ is compared with that made in 1909.Footnote 50 Here, Caruso seems finally to have found a homogeneous sombre timbre for his rising phrases moving across the passaggio. The first ascent to the F♯4 (Example 3) is now executed by progressively darkening the D4, E4 and F♯4 through a skilful recourse to well-graduated vowel modification, while drawing the weight of the heavier register upwards.Footnote 51 The runs to the top A4s (Examples 4 and 5) are assertively covered, stretching the vocal tract to its maximum. With the vocal tract fully elongated and widened, Caruso is now able to produce well-rounded, powerful and ringing A4s, where variations in vocal colour between the registers are effectively eliminated.Footnote 52 This total vocal consistency is revealed even more clearly when Caruso leaves the top notes. From these impressively wide A4s, which fill the acoustic space like huge pillars of air, his descending sounds preserve the same ringing quality and ample resonance, sustained by a firm column of breath.Footnote 53 Homogeneous timbre, though, comes at a cost – the loss, or at least the greater attenuation, of nuanced singing with all its variety of phrasing and shading. For example, the messa di voce on the first A4 of ‘E lucevan le stelle’, which Caruso attempts in the recording of 1904, is lost in 1909, when the tenor’s top note is straightforwardly forte.

This achievement took more than 15 years of experimentation with laryngeal heights and breathing techniques.Footnote 54 Caruso’s long process of trial and error was punctuated by alternate phases of progress and drawbacks, as an attentive reading of American reviews also reveals. In his article on the 1905 Met production of La sonnambula Aldrich wrote:

But it cannot be denied that he has recently done much to give his discriminating admirers uneasiness. He has been prone to let his voice fall into a throaty quality; his tones have sometimes sounded pinched. There has been more than suspicion of the ‘bleat’ that is generally associated with the idea of the Italian tenor of the lesser sort. In seeking for those exaggerated effects of pathos and tears and superhuman passion, he has not infrequently, and more frequently than he used to, cast to the winds all thought of tonal beauty, of that smoothness, purity, translucent clearness and warmth that are truly the distinguishing marks of his wonderful voice.Footnote 55

And Henderson’s verdict on Caruso’s Enzo in Ponchielli’s La Gioconda was that, ‘The white voice is not a grace of song when it is overused, nor is a throaty quality of tone at any time desirable. Caruso is guilty of much whiteness and occasional throatiness.’Footnote 56 These criticisms might be explained in the light of Caruso’s thorough-going exploration of a heavier system of vocal production. The ‘throatiness’ to which critics refer might depend on the progressive search for lower laryngeal positions, while his swapping between the extremes of ‘white’ voice, pinched sound and bleat might well be the result of faulty balances as he was experimenting along the way.

Caruso’s journey towards ‘total timbral consistency’ continued despite setbacks and uncertainties. His issues with the high notes (recalled above by both Tetrazzini and Melba, but also discussed in critics’ reviews) could easily have been overcome by sticking to the traditional rule of ‘carrying down’ the light register. Nevertheless, if it is true that – notwithstanding the timbral inequalities in his voice – his singing was considered more ‘natural’ and ‘spontaneous’ than that of both Borgatti and De Lucia, it is difficult to resist the impression that he decided to embark on a different path.

Why did Caruso sound more natural and spontaneous? The answer is a complex one. In line with changing tastes during this dynamic era of transforming operatic style, timbral differences between registers were apparently still acceptable as part of the idea of ‘spontaneous singing’. On the other hand, the abuse of falsetto was criticized. The most plausible hypothesis is that Caruso was struggling with the issue of extending the quality of his rather weighty first tenth to the passaggio and upper notes, arousing impressions of a ‘bodily’ singing in tune with the characteristics of the new verismo roles which populated the lyric stage of his time. The progressive erosion of timbral inconsistencies prompted by this process elicited those new evaluations of such long-standing terms of critical discourse as ‘natural’ and ‘spontaneous’. As was the rule in his era, Caruso was singing a contemporary repertoire (the older operas in which he sang dated back at most 70 years), including roles that he created on several occasions. He clearly had the right voice for this repertoire: his morbidezza, the full-rounded, dark timbre of the middle range and the mellow and suave delicacy of the mezze voci all gave his singing the ‘carnal’ quality of a sensual and masculine type which so much appealed to the taste of his contemporaries. But, ultimately, it was only by abandoning the aesthetics of a timbral divide between registers that a ‘modern’ conceptualization of the operatic voice could emerge.

Verismo and ‘modern’ singing

Why would singers make the effort to conceive a ‘new’ vocal sound? The short answer is: because of the rise of verismo opera. To define this operatic movement has proved a difficult task, as is demonstrated by the intense scepticism with which scholars have treated verismo opera and the very possibility of transferring the characteristics of literary verismo to music. ‘Operatic verismo’, wrote the musicologist Matteo Sansone, is a ‘misleading expression’, as it encompasses too large a variety of operas.Footnote 57 Jay Nicolaisen drew the borders of a vast territory that spans ‘the musically primitive Cavalleria rusticana (1890), a one-act opera based on a violent play by Giovanni Verga, [to] the musically sophisticated Turandot (1924), a four-act opera based on an exotic fairy tale by the eighteenth-century Italian Carlo Gozzi’.Footnote 58 Carl Dahlhaus asks whether musical verismo has anything to do with its literary counterpart, given that ‘the differences between them are so glaring that one can doubt whether […] it is meaningful at all to speak of verismo in opera’, a question echoed rhetorically by Adriana Guarneri Corazzol, David Kimbell and Hans-Joachim Wagner.Footnote 59 These scholars instanced the absence of social criticism, the sensationalistic treatment of the characters and their lack of psychological development, and the incompatibility between the principle of impersonality (elimination of the authorial voice from the text) and the theatricality of verismo operas as important elements which highlight the profound disjunction between literary and musical verismo.

In recent years, Andreas Giger, building on the wider perspective of late nineteenth-century criticism, has proposed an entirely new view of musical verismo, advocating its existential ‘autonomy’ as a long-term movement which promoted a complete renovation of Italian opera through its departure from the structures of Romantic melodramma. Footnote 60 From the 1860s, literary and art criticism linked the term verismo with the introduction of new subject matters (low-life, vulgar, trivial subjects, whose representation in artistic forms had traditionally been rejected), to which veristi were in no way exclusively committed, and a consequent renewal of linguistic styles. More importantly, the representation of both contemporary subjects and historical ones must be the expression of a methodological or ‘concrete’ observation of reality, which is the result of an attentive depiction of the environment in which the recounted stories take place.Footnote 61 With these categories in mind, critics might well have applied the term verismo to the operatic context. The breezy dismissal of any link between literary and operatic forms of verismo that music historians have traditionally expressed seems less plausible once we adopt this historiographical approach to literary criticism.

In opera as well as in literature and the fine arts, verismo prompted a gradual process of renovation: renovation of structures, forms, language and subject matter which within the span of several decades (from the 1860s to the 1890s) changed the face of Italian opera. One of the most striking elements of friction with the previous conventions of the Romantic melodramma was a search for dramatic continuity, although many other ingredients contributed to this process: the harmonic texture of the ‘new’ operas, their quasi-symphonic traits (so fiercely criticized by, among others, Verdi), a gradual reconsideration of the lexicon and syntactic structures of librettos and a new shape and articulation of the vocal line.

The renewal of dramaturgy was a direct effect of the interaction with French opera that reached its peak in the last decades of the nineteenth century, when first the works of Meyerbeer, Gounod and Thomas (in the 1870s) and later those of Bizet and Massenet (in the 1880s) became a steady and consistent part of Italian theatrical seasons.Footnote 62 Their impact on verismo composers was considerable, especially with regard to psychological characterization and rhythmic articulation. A focus on individual characterization was shared by many of the French operas of the period: Bizet’s Mireille (1863) and Carmen (1875), Massenet’s Manon (1884) and Werther (completed in 1887, although its Viennese première – in a German translation – did not take place until 1892), to name only a few examples. French composers working along the lines of the character’s psychological development created a musical dramaturgy in which ‘natural’ dramatic continuity was met by self-contained moments of melodic-harmonic expressivity. And this was the legacy that Puccini, for instance, inherited from Massenet.

When psychology broke into the operatic world, the rigid formulas of melodramma were put in question. In that system, the possible interaction between characters was already predetermined by their archetypal functions: the hero, the rival, the villain, the victim and so forth. Their unambiguous and predictable behaviour gave life to a dramaturgy which, in turn, justified a standard set of solos and ensembles all conveniently articulated in the ‘cantabile–cabaletta’ formula. When characters began to develop individual psychological traits, however, the traditional structures of Romantic opera with its quintets, sextets and concertatos broke down and eventually turned into a series of extended dialogues for the purpose of achieving dramatic realism. Verdi’s Otello (1887) marked a significant move in this direction, and even more so Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci (1892), which displays throughout an almost unbroken sequence of dialogical exchanges and confrontations. In Cavalleria rusticana the closed form of ‘onstage music’ (drinking songs, serenades and stornellos) is interwoven with what Dahlhaus called the ‘arie d’urlo’, where the formalism of traditional melodramma is broken in favour of dramatic continuity.Footnote 63

As the psychological individualization of operatic personages was growing in complexity, Italian composers increasingly asked their librettists to emulate the fluidity of French poetic metre, as this was better suited to following the emotional volatility of the new characters who populated the operas of the last part of the century. From Massenet’s Manon, who moves between voluptuousness and naivety, to Bizet’s Carmen, who sparks flashes of wildness and sexual power, the French language subtly highlights their temporary and changing states of mind. By contrast, Italian, with its heavier accent and the symmetrical organization of its librettos, shows a sort of rigidity and stiffness once the florid style of singing is abandoned. Verdi was closely implicated in this search for rhythmical variety, and he burdened his long-suffering librettist Antonio Ghislanzoni with endless requests on this topic.Footnote 64 Arrigo Boito, who supplied the librettos for Verdi’s last two operas (Otello and Falstaff), was to play a significant role in the modernization of Italian prosody in terms of both versification and renovation of the operatic vocabulary. All his librettos display this aspiration to escape ‘the unbearable boredom of cantilena and symmetry […] of Italian prosody, which almost inevitably generates poverty of rhythm within the musical’.Footnote 65 Puccini’s obsession with metrical variety is well known. His need for a fluid musical phrase that only the casual rhymed or unrhymed mixture of irregular line lengths – quinari, senari, settenari, ottonari, decasillabi and endecasillabi – could allow induced his librettist, Luigi Illica, to create the illicasillabi, a word coined by Giuseppe Giacosa, Puccini’s other librettist, as a joke.Footnote 66

The renovation of the operatic libretto also involved a gradual transformation of the language, although this aspect was not an immediate consequence of the new character types portrayed on stage, as one might expect. The peasants in Cavalleria rusticana, for instance, do not necessarily speak in everyday language. In the stanzas of the opening chorus, high-brow vocabulary is used throughout. The women, for example, sing that ‘gli aranci olezzano sui verdi margini’ (‘the scent of oranges spread throughout the green borders’, where the archaic olezzano – smell or perfume – replaces profumano) and ‘cessin le rustiche opre’ (‘let’s cease the rustic work’, where opre is the archaic form of opera, and rustiche is similarly outdated). Turiddu’s sentence ‘Invan tenti sopire / Il giusto sdegno con la tua pietà’ (‘In vain do you endeavour / My righteous anger thus to subdue’) still presents the markers of an elevated and stylized construction, whereas Santuzza’s ‘quella cattiva femmina’ (‘that bad woman’), although lowbrow, is milder than the reiterated epithets thrown at Nedda by Tonio and Canio in Pagliacci: ‘sgualdrina’ and ‘meretrice abbietta’ (both variants of ‘slut’).

Where the high-flown jargon of conventional librettos seems to be largely overcome is in Puccini’s La bohème (1896). The simple phrase ‘che m’ami … dì …’ – ‘Tell me that you love me!’ – with which Rodolfo sweetly commands Mimì represents the truncated version of the elaborate, rhymed lyrics finely sung by tenors of a previous age. For instance, the troubadour Manrico in Verdi’s Il trovatore links the spasms of death with the ecstasy of love in his cantabile ‘Ah sì ben mio’, and even for Otello the ideas of immense love and immense fury in battle are still closely associated. But many examples in La bohème attest to the complete renovation of operatic vocabulary – from the incidental episodes of light-hearted bohemian life to the most tragic moment of the drama, the death of Mimì: ‘Sono andati? Fingevo di dormire / […] ho tante cose che ti voglio dire, / o una sola ma grande come il mare / […] sei il mio amor … e tutta la mia vita’ (‘Have they gone? I pretended to sleep / […] I’ve so many things to tell you, / or just one thing – huge as the sea / […] You are my love and my whole life’). Mimì’s simple language echoes the simple (and realistic) dynamics of human relationships on which the drama is built.

The highly ornamented vocal lines of bel canto are clearly out of place in such a context. The declamatory style, whose predominance in the ‘melodramatic system’ Lamperti had feared, finally ‘despoiled [the vocal line] of agility of any kind’.Footnote 67 This result was to be blamed on the harmonic texture of the ‘modern’ operas, as the vocal pedagogues defined them when debating their terrible flaws and negative effects on the cultivation of healthy and long-lasting voices. In the opinion of the prominent baritone and influential voice teacher Leone Giraldoni, ‘modern’ composers, stuck between past and future, attempted to find a way forward by emulating foreign musical languages. ‘Let composers write as they used to in the past, taking advantage from the harmonic science, not to substitute for the melodic expression, but only to add valuable devices.’Footnote 68 This invective, as well as many others of the period, was directed against the operas (and theoretical works) of Wagner, whose well-known controversial reception in post-unification Italy did not diminish the enormous influence of the German’s complex harmonic language on young Italian composers.

The erosion of florid singing and the concomitant rise in declamatory style, bigger orchestras and dense harmonic textures all had their effects on the idea of vocalism. The elaboration of this new vocal aesthetic could not possibly be limited to a simple quest for vocal power, as the advent of a realist theatre required that the ‘modern’ singer search for a new sound, with naturalistic timbral connotations. The purity of tone so patiently cultivated by the older Italian singing teachers was exchanged for the ‘carnal’ sound that singers born during the 1870s, such as Caruso, Titta Ruffo and Eugenia Burzio, were pursuing.

The stylized tone quality of bel canto roles suits the ideal world in which such characters live and love. Even their voice types are stylized and not naturalistic. The Rossinian contraltos, Bellini’s very high tenors and Donizetti’s mad coloratura sopranos do not belong to the real world, as their vocal identities bear no relation to the common voices of everyday life. Verdi got rid of some of these types (very high tenors), progressively relegated others to secondary roles (basses and contraltos), kept other types for a long period (high soprano voices) and created new ones (the high baritone, completely distinct from the bass-baritone). Moreover, with the advent of verismo opera, political and moral themes such as Risorgimento and religion, which had exerted a prominent developmental force on Romantic opera, were replaced by the pervasive subject of love, a tendency which was obviously reinforced by the sheer influence of French bourgeois and sentimental dramas. The ‘love’ of Mascagni or Puccini, though, bears a feeble relation to that ideal and inspiring sentiment exalted in the operas of Romantic composers, as veristi tended to exploit love in its sensual or even overtly sexual aspects. In terms of vocalism, this choice translated into vocal lines centred on the medium voice range. As Rodolfo Celletti insightfully underlined:

Sensuality is especially expressed in the ‘medium’ range of the voice, and tends to dark colours. This explains both the shortening of the upper range of the voice and the tendency to centre the tessituras around the middle range. This was a general phenomenon.Footnote 69

The middle range of the voice offers a wide array of possibilities to the actor-singer, as in this area they can transform, with a certain degree of spontaneity, the flow of singing into sobbing utterance, shouts or whispers. The other element considered in the above quotation is the lowering of the upper limit of the vocal range. This procedure, as Celletti himself pointed out, does not, however, make the singer’s life easier. On the contrary, the tessitura gravitates around the high-middle range, which corresponds to the area of the passaggio critical to the production of top notes.Footnote 70 This poignant observation was corroborated by a generalization added by Fedele D’Amico:

Personally I have always believed not only that veristi had always been keen on this procedure [insistence on the passaggio from the medium to the upper range] […] but also that it represents the specifically ‘veristic’ feature of their style, in short that the musical verismo is defined by this procedure […] Indeed, that insistence on an area of the voice which is less natural and more problematic demands an effort, a tension which turns singing towards a ‘directly’ passionate expression, similar to the excitement of a spoken language.Footnote 71

While Celletti principally refers to Mascagni’s roles in his essay, D’Amico posits a question with which he also launches a kind of credo (‘Personally I have always believed …’) as to what characterizes verismo style. If the passaggio becomes the focal area of verismo tessituras, as D’Amico suggests, the effort of sustaining the voice around this area evokes the tension of that sexual excitement which can be heard in the singing of characters as different as the peasant Turiddu (in Cavalleria rusticana) and the aristocratic Loris (in Giordano’s Fedora). Although nineteenth-century writings had referred to the masculinity of spinto tenor voices in particular, the idea of an overt exploitation of the singing voice’s erotic characteristics was not entertained. Discussing the various types of tenors, the voice teacher Heinrich Panofka repeatedly associated the tenore di forza with notions of ‘masculine power’ as well as ‘heroic’ or ‘chivalrous’ sentiments and defined its chief quality as a ‘noble temperament, capable of loving in a tender, but worthy manner’.Footnote 72

The new form of verismo vocal aesthetic was also elicited by the highly tense phrasing characteristic of the new operas. The ‘pure’ tonal quality of the old school was perceived as somehow passive when confronted with the nervous energy of the new characters. In Pagliacci, Canio’s sorrow, as expressed in one of the best-known verismo arias, ‘Vesti la giubba’, is not the intimate outpouring of his betrayed heart, but a furious and bitter burst of torment (‘ridi del duol che t’avvelena il cor’) so acutely painful that he – an elemental man moved by his basic instincts – has no idea how to deal with it. This neurotic intensity, in order for the audience to believe it and empathize with it, needed that visceral sound that was epitomized by Caruso. In the concluding part of this discussion, the comparison of Caruso’s recordings with those of two other tenors of the era should heighten their rather different ideas of tonal quality and (consequently) vocal phrasing. The following analysis should put in sharp relief those elements which, displayed in a scattered and incompletely developed manner by some of his predecessors and contemporaries, were brought together by Caruso in order to shape a highly characterized type of vocalism.

Giovanni Zenatello and Alessandro Bonci: late bel canto systems of uniting and balancing the vocal registers

I begin with a comparative analysis of Zenatello’s and Caruso’s recordings of ‘Vesti la giubba’ (from Pagliacci) made in 1905 and 1907 respectively.Footnote 73 These two renditions exemplify the heavy (Caruso) and lighter (Zenatello) strategies for achieving vocal registration (the equalization of registers). Zenatello approached the passaggio and upper notes within the traditional rules of the bel canto school; thus, his way of blending the various registers was based much more on the principle of ‘pulling down’ the medium register than on that of ‘drawing up’ the chest.

In Zenatello’s recordings, his tonal quality is similar to that which can be heard in recordings made by the robust tenor voices of the previous generations, such as Francesco Tamagno or Francesco Marconi, both born in the 1850s. These tenors achieved an even registration across the range by keeping the whole area around the passaggio light and bright. They were extremely careful whenever singing in this range because high notes occurred far more abundantly in pre-verismo scores. Therefore, in that repertoire, exemplified by the operas of Verdi and Meyerbeer, they had to focus on keeping their weighty voices as light and bright as possible in order to be ready for the sudden and frequent jumps to the upper range.Footnote 74

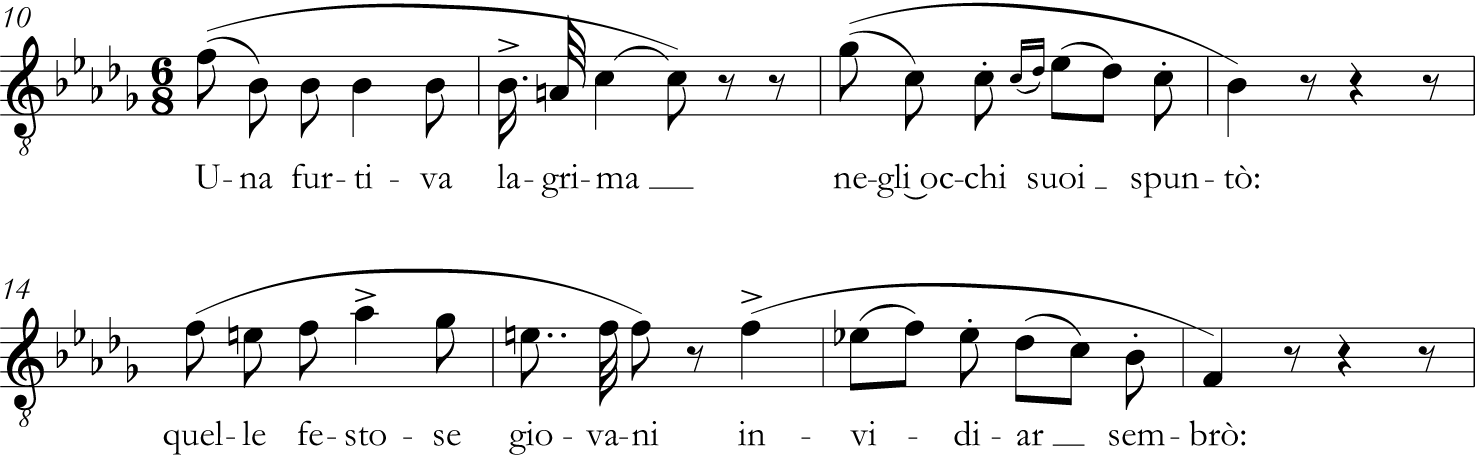

This is exactly what happens with Zenatello when he is singing in the passaggio. The held F♯4 which precedes the passage ‘Ridi, Pagliaccio’ (see Example 6) is sung with lighter registration and bright timbre. Caruso, on the other hand, covers his F♯4 by drawing up the heavier registration.Footnote 75 In the remaining part of the phrase – with the insertion of a ritual double acciaccatura between the exclamation ‘Ah!’ and the first syllable of ‘Ri-di’ – the step F♯4–G4 is completely smoothed over by Caruso, giving the listener an impression almost of singing in slow motion.Footnote 76 The difference in Zenatello’s registration choices is again clearly audible in the way in which he projects the G4 and the A4 of the following bar; here I would suggest that his pealing top notes spring out from a vocal tract which is less elongated than that of Caruso. Owing to the dramatic weight of his voice – Zenatello first trained as a baritone and then switched to tenor (1899) – he is capable of obtaining a convincing tone quality.Footnote 77

Example 6 Ruggero Leoncavallo, Pagliacci, dramma in two acts, libretto by Leoncavallo, vocal score, ed. Giacomo Zani (Milan: Sonzogno, 1981). ‘Vesti la giubba’, Act 1, scene iv, bars 32–40 (vocal part only).

Nevertheless, his struggle with the breath, clearly audible both at the end of every phrase and on each in-breath, is eloquent; it highlights the fact that a tense long-legato line which moves within the middle–high range but avoids the extreme top reaches of the voice, is not ideal for a singer who relies on a lighter type of registration. This bel canto-like approach to vocal registration (with a bright and ringing quality) works extremely well with tenor roles of the heroic type such as Verdi’s Manrico (in Il trovatore), as Zenatello’s recordings demonstrate, but is less suitable for the sensual, dark, passional, erotic and even sometimes degenerate characters of verismo. The aptness of lighter systems of vocal registration to Verdian roles can be appreciated also by listening to Giraud’s recording of ‘Quando le sere al placido’ from Verdi’s Luisa Miller. Here Giraud approaches the top notes in the fashion of Zenatello with a partially elongated vocal tract, as I have just attempted to define it. The same procedure is audible in Borgatti’s rendition of ‘E lucevan le stelle’, where he similarly ascends to the top A4s.Footnote 78

One singer who seems to have had no recourse to the bright (clair) timbre is Alessandro Bonci. He was three years older than Caruso, and the two tenors shared a similar repertoire, particularly in the first phase of their careers, a fact that encouraged the press to foster the antagonism between the two.Footnote 79 While Bonci retained his roles and the typical traits of his vocalism consistently over the years, Caruso started his transformation into a dramatic tenor from 1907/8 onwards. Ultimately, this process allowed him to cope with heavy roles, such as Samson in Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila (1915), Flammen in Mascagni’s Lodoletta (1917), Jean in Meyerbeer’s Le prophète (1918) and Eléazar in Halévy’s La Juive (1919).

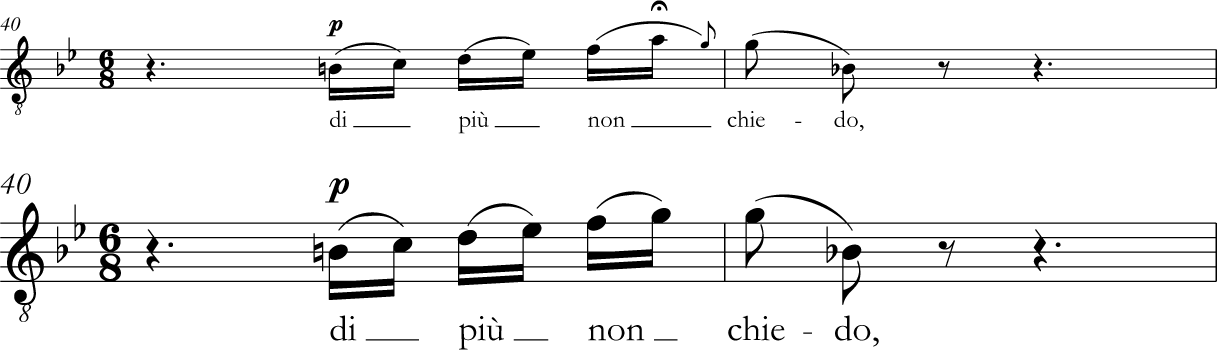

In his 1912 recording of ‘Una furtiva lagrima’, Bonci sings the first two phrases of both the first and second verse in a real mezza voce. Footnote 80 Avoiding recourse to the lighter registration, Bonci achieves his piano effects through breath pressure alone, and seems to follow the route of consistently covering the passaggio. Bonci’s characteristic vibrato makes it harder for the listener to follow clearly how he manages the leaps to the A♭4 of ‘festose’ (see Example 7) or the A♮4 of ‘di più non chiedo’, which he adds to the score (see Example 8).Footnote 81 However, I would suggest that what we hear at these points is another example of the bel canto approach to vocal registration, with a vocal tract which is not completely elongated and expanded (that is, with a partially lowered larynx in a not fully raised soft palate). Whatever opinion one decides to adopt about Bonci’s way of balancing and uniting the registers, his phrasing and rubato, not to mention his use of fioriture and his diction, are certainly not an example of ‘modern’ singing. The idea of flexible tempos is so inextricably part of Bonci’s phrasing that the initial attacks of Nemorino’s introspective solo are held as if a fermata were written above them. While in the first two phrases the basic rhythmic pulse is almost completely slackened, from the third phrase (‘quelle festose giovani’) Bonci speeds up the tempo, as the very concept of rubato suggests. Nevertheless, here he modifies the note values at will, to the point of introducing sounds where rests are written: ‘giovani’ is restricted to the note value of a crotchet and the attack on the following ‘in-’ of ‘invidiar’ is anticipated in the last quaver of the first beat (where the syllable ‘-ni’ of the word ‘giova-ni’ is written), while the tempo is slowed down again in a big allargando.

Example 7 Donizetti, ‘Una furtiva lagrima’, bars 10–17 (vocal part only).

Example 8 Donizetti, ‘Una furtiva lagrima’, bars 40–1 (vocal part only).

Compared with the liquid phrasing of this 1912 Bonci recording of Nemorino’s aria, Caruso’s recording of 1902 seems to have been conceived in a relatively strict tempo. If Caruso occasionally adds some fioriture or makes use of some heady mezze voci, his idea of tempo is nevertheless more rigorous, and the many concessions he makes to rhythmic flexibility do not obscure the perception of a basic rhythmic pulse.Footnote 82 Far from embarking on an exploration of these stylistic gestures per se, a task already brilliantly carried out by several scholars, I consider them in the singing of Bonci and Caruso in order to establish the extent to which these elements of style were determined by the changing aesthetics of tonal production.Footnote 83 In other words, the specific manner in which pre-verismo singers conceived rubato, portamento, diction and coloratura was bound to be transformed and progressively disappear, because verismo singers – Caruso above all – were working out how to achieve total timbral consistency.

This new notion was completely at odds with the older style, with its extremely flexible tempos, frequent fioriture, endless diminuendos on high heady tones and neat vowel articulation. The complete equalization of the vocal compass within a heavy system of voice production implied an inevitable loss of both timbral variety and flexibility of the vocal mechanism. Reaching the top notes is harder from the elongated vocal tract favoured by Caruso than from the comparatively higher laryngeal position of (for example) Zenatello. Moreover, with the erosion of timbral inconsistencies the idea of a ‘pure’ tone quality progressively lost its grip on singers’ imagination, and the highly individualized voices of the past gave way to the more standardized types of the present. Trained within traditional schools that shared several fundamentals of bel canto (costal-diaphragmatic breathing, timbral register divide, preference accorded to lighter types of registration, ‘pure’ and ‘true’ vocal colour, pure and neat legato line ensured through the scrupulous study of portamento, messa di voce and a massive diet of graded exercises and solfeggi), turn-of-the-century singers built up their new set of vocal technical skills from a common background.Footnote 84 From this perspective, the acknowledgement of some sort of continuity between the vocal tradition of bel canto and the nascent verismo singing is hardly questionable. In line with the above-mentioned hypothesis of Giger, who interprets verismo as a progressive renovation of the forms and structures of the Romantic melodramma, the evolution of a ‘modern’ vocalism also results from a progressive revisitation of bel canto concepts, such as timbral divide and ‘pure’ tonal quality.

An essential driver of this entire process is represented by the appearance on stage of the new verismo characters, which with their sheer erotic energy called for a gendered, carnal, earthy vocal sound. With their vocal lines centred on the critical area at the junction of the registers (the passaggio), a strain was put on the singer which evoked that of sexual arousal. The sparse use of top notes and the general avoidance of the most extreme high pitches also favoured systems of heavier registration, bringing the elongation of the vocal tract to its utmost limit. The substance of ‘modernity’ lies, therefore, in this new way of uniting and balancing the vocal registers, which in turn depended on a profound reconceptualization of the vocal sound. The process that I have reconstructed here in relation to the example of Caruso defined a ‘modern’ type of vocalism. This type has since then set the bar of the international standard in mainstream operatic repertoire, with a longevity probably unequalled in the history of Western classical art song.