Starting around 1898 and continuing throughout the first decade of the twentieth century, the Catalan textile industrialist Ruperto Regordosa recorded several dozen prominent musicians at his home in Barcelona using an Edison Suitcase Standard Phonograph. Regordosa’s efforts resulted in 358 wax cylinders (currently held at the Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona, as the Col·lecció Regordosa-Turull)Footnote 1 containing 260 individual musical performances.Footnote 2 The collection is without doubt one of the most significant for the study of the early history of recorded classical music, both in Spain and globally, not only because of the sheer volume of the recordings and the prominent performers they feature (including the pianist and composer Isaac Albéniz), but also because the recordings were made by Regordosa himself for his own private use and not for commercial purposes. This makes it one of the most substantial collections from this period of what we might call amateur recordings.Footnote 3 Julius Block, a Russian businessman and phonograph enthusiast, who recorded such luminaries as Anton Arensky, the young Jasha Heifetz, Paul Pabst and Sergey Taneyev at his home, left behind about 100 musical recordings,Footnote 4 and a similar number resulted from the efforts of Lionel Mapleson, a librarian at the Metropolitan Theatre in New York who recorded singers live on the Met stage for non-commercial purposes.Footnote 5

Public institutions in Spain currently hold three other collections that include amateur recordings (those of Vicente Miralles Segarra, Leandro Pérez and Pedro Aznar), but their numbers are very small in comparison with Regordosa’s.Footnote 6 Miralles Segarra’s collection, now held at the Museo de la Telecomunicación at the Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, amounts to about 20 amateur cylinders presumably recorded by Miralles Segarra himself and featuring family members and acquaintances singing (often unaccompanied), reciting or speaking.Footnote 7 This is indeed a valuable collection for the study of the culture surrounding home recording practices, but less significant as a document of historical performance practices on stage, since all the singers featured were amateurs. In the northern Spanish city of Huesca, the local businessman Pérez recorded in 1907 nine pieces played by the teenage violinist José (Pepito) Porta, who went on to teach in Lausanne and premièred the trio version of Stravinsky’s Histoire du soldat. Footnote 8 Aznar, a businessman from Barbastro in Aragon whose collection of commercial wax cylinders is now held at the Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid, also left a small number of cylinders he recorded himself, presumably of performances by non-professional musicians.Footnote 9 Regordosa’s collection therefore stands as significant both for its size and for the professional prominence of the performers it captures.

Despite its importance, though, Regordosa’s collection has not yet been the object of extended critical examination, and there might be several reasons why this is the case. The collection has only recently been digitized and made widely available to researchers,Footnote 10 and the lack of scholarly research about the early history of recording technologies in Spain and Catalonia can make these recordings difficult to situate.Footnote 11 To provide a detailed examination of every recording in the collection would be too ambitious an aim for this article, which restricts itself instead to a discussion of the ways in which the collection might transform our understanding of early music-recording practices in Spain and elsewhere. I argue that this potential is most obvious in two areas: the study of historical performance practices as documented in early recordings, and the study of the home recording culture that developed alongside commercial recording around 1900 in Spain and elsewhere. For reasons that are primarily of a practical nature, though, these two areas will not be given equal weight throughout this article. From a purely musicological point of view, the most immediate appeal of the collection might lie in what it reveals about vocal performing practices around 1900. The number of cylinders is rather substantial (they amount to about a fifth of the total surviving wax cylinders recorded in Spain)Footnote 12 and – as will be discussed below – they feature some of the most significant singers of their time, including some of whom no other recordings have survived. Nevertheless, a full examination of the performance practice issues latent in a collection of 260 recordings in disparate genres cannot be satisfactorily addressed without giving precedence to broader contextual and historical issues, from the commercial recording landscape in Spain and internationally to Regordosa’s own recording practices and ideas about recording. This contextualization work, though, should not be regarded as merely ancillary to research on performance practice. By itself, it can also substantially add to our understanding of early home and amateur recording practices, a crucial but understudied topic; there is no single study devoted to it, even though it is widely recognized that phonograph owners did engage in self-recording.Footnote 13 Studying these early practices can also help us better to understand the history of amateur recording or self-recording, of which there are numerous well-known examples in later periods. Indeed, some of these later practices have received more scholarly attention.Footnote 14 In this article I will draw on research on self-recording practices in later eras to explore how issues of affection, memory, self-expression, archiving and agency led Regordosa to adopt certain practices from commercial recording labels and to develop others of his own in order to turn the phonograph into a technology of reminiscence adapted to capture and reflect his own live music experience in Barcelona.

In studying the broader context surrounding early recordings in order to ascertain their value as documents of performance practice, I follow what is now a substantial tradition going back to Robert Philip’s pioneering study in changes in instrumental performance.Footnote 15 Implicitly or explicitly, studies within this tradition share an assumption that early recordings cannot be regarded as perfect representations of widespread performing practices on stage at a given moment in time, in a given context or even for a given performer. Instead, they argue (and, in many cases, demonstrate in practice) that the researcher must take a wealth of contextual information into account in order to ascertain the extent to which a particular recording might allow us to draw broader conclusions on performance practice. This often takes the researcher outside the realm of musicological or performance practice research, owing to the complexity of the contexts (technological-material, economic, cultural-aesthetic) in which early recording technologies emerged.Footnote 16

Although this article draws on a wide-ranging body of multidisciplinary research in order to expand on specific points, one set of concepts in particular is crucial to understanding how Regordosa might have conceived the recordings he made himself vis-à-vis his experiences of both listening to commercial recordings and attending live performances. These concepts relate to the cultural-historical mechanisms by means of which listeners come to accept a recording as a representation of reality, even though it is not such in strictly acoustic terms: it is rather, as Peter Johnson puts it, ‘a species of artistic illusion’.Footnote 17 Stefan Gauß writes that the phono-object ‘does not simply capture sound and then play it back again; rather, it replaces the captured acoustic reality with something new, with its own specific qualities’.Footnote 18 On the other hand, Feaster’s concept of ‘performative fidelity’ (that is, the fact that the recording, among a multiplicity of frames or options, ‘is accepted as doing whatever the original would have done in the same context’) highlights the socially constructed, evolving nature of the above-mentioned mechanisms.Footnote 19 It also follows from the above that the development of these mechanisms entails the participation (conscious or unconscious) of a range of agents (listeners, producers, performers, record companies); in this sense, Ashby argues that the early decades of commercial recording technologies were also a period in which ‘phonographic literacy’ developed, with successful performers being fully able to understand and respond to the notion of phonographic literacy shared by their contemporaries,Footnote 20 and Feaster reminds us that early audiences needed to be guided as to how they ‘should interpret the experience of hearing’.Footnote 21 Regordosa’s recordings provide a fascinating and rare example of how these concepts might have developed in practice, as we examine his extensive collection of recordings and ascertain how he might have adopted some of the practices introduced by the gabinetes to this effect while departing from or challenging others in order to make his cylinders more representative of his experience of live music.

Following the separation I have outlined above between the broader social, cultural and musical context on the one hand and issues of performance practice on the other, the main body of this article falls into two sections: ‘Outside sound’ and ‘Inside sound’. In the latter, rather than drawing conclusions about performance practice as reflected in Regordosa’s recordings, I examine broader issues concerning sound (that is, not only the music, but the spoken word as well); I consider how these expand or challenge our current understanding of early recordings as documents of performance practice, and how they advance new questions that can inform future research more decidedly focused on performance practices in Regordosa’s collections. At the same time, though, it is important to acknowledge that recorded sound and context cannot easily be dissociated, so there will be considerable interaction between the two sections. When discussing broader issues concerning the development of the collection and Regordosa’s motivations to assemble it, I will occasionally take detours concerning the musical content of some of the cylinders, as these can illuminate certain aspects of the recording process. Similarly, in my closer discussion of a selected number of recordings in the second section, I will refer back to aspects of the broader context when they are helpful in clarifying particular sonic aspects of the recordings.

An important caveat here is that, as with all digitized early recordings, transfer processes can significantly influence what we hear and thus lead us to draw wrong conclusions. With regard to the Regordosa collection specifically, Margarida Ullate i Estanyol, sound curator at the Biblioteca de Catalunya, notes two particular details that are relevant to the collection as a whole.Footnote 22 First, the transfers available at the Biblioteca de Catalunya contain no edits introduced during the transfer process, whereas commercial releases on CD of some of the collection’s cylinders were indeed edited (the processes used including, for example, equalization, cleaning and declicking). Secondly, since all cylinders were digitized as part of the same project, we can imagine that the large numbers provided engineers with a sufficiently solid frame of reference when choosing appropriate transfer speeds, as these can often only be decided by listening to multiple recordings by the same performer or made under the same conditions.Footnote 23 Such issues are clearly pertinent at the general level when considering the collection as a whole, and below I will reflect further on the extent to which the transfer may have been problematic when considering specific cylinders.

Outside sound: the mechanics of building a collection; the singers and their repertoire

The early development of commercial phonography in Spain provides a crucial frame of reference for understanding Regordosa’s recording practices. The Edison Spring Motor, Edison Home and Edison Standard phonographs were introduced in Spain in the years 1896–8. These new devices were more affordable and easier to operate than their predecessors and hence more appealing to domestic users,Footnote 24 and so it was around them that an indigenous recording industry developed, led by the so-called gabinetes fonográficos (phonographic cabinets) and not by Edison’s companies themselves, as was the case elsewhere.Footnote 25 There is evidence of at least 40 gabinetes operating independently of each other around this time in Spain.Footnote 26 Some were essentially one-man operations, whereas others functioned as sidelines for established opticians, pharmacists, scientific equipment sellers or electricians. They sold phonographs, accessories and a small number of recordings imported from the US and France, but what allowed the gabinetes to thrive were the recordings they produced and marketed themselves, mostly employing local musicians. From 1899, the gabinetes faced competition from gramophone multinationals (such as Gramophone, Odeon and Pathé) – which could, crucially, produce hundreds of copies from the same matrix; and by 1905 all gabinetes had either closed down or become resellers of gramophone discs.

More than a thousand recordings from this short-lived era have survived, testimony to one of the most important contributions that the gabinetes made to the history of recording technologies in Spain. Indeed, they turned sound recordings from scientific curiosities to aesthetic artefacts and commoditiesFootnote 27 and, in doing so, were key to the development of notions of phonographic literacy and performative fidelity in Spain. Gabinetes thereby operated in close connection with their own local context: they frequently recorded recently premièred successful operas and zarzuelas, as well as others from the repertoire with which potential customers would be familiar. They also recorded singers in roles for which they were known (although this was not always possible) and favoured certain ways of saying and communicating text expressively, especially in zarzuela recordings. In Madrid, many gabinetes were also located next door or in close proximity to opera and zarzuela theatres, making it likely that their customers would acquire recordings as mementos of the live music experience.

A second key contribution of the gabinetes was the introduction of amateur recording practices in domestic settings. Self-recording was a key part of the publicity strategies of the gabinetes, most of which consistently mentioned blank cylinders in their advertisements, and when the gramophone came along repeatedly argued that the phonograph was superior because of its self-recording capabilities.Footnote 28 The extent to which the strategy of the gabinetes was successful is difficult to ascertain (in Germany, for example, similar advertising techniques did not result in success),Footnote 29 but there is evidence that at least a handful of phonograph owners, such as Miralles Segarra, Pérez and Aznar, engaged in amateur recording practices. Others wrote to Valencia’s Boletín fonográfico seeking or offering advice on making home recordings.Footnote 30 While accounts suggest that these individuals were motivated mainly by an interest in technology and/or music, they also constitute an early example of the persona-building processes typically associated with the consumption of recordings at later stages in the history of recorded music, in an era when these processes were scarcely understood.Footnote 31 Indeed, with the gabinetes skilfully positioning themselves within discourses about science, technology, modernization and national identity, phonograph owners also signalled that they belonged to a technologically literate middle class that was contributing to the economic and social development of the country by stimulating foreign trade and importing new and culturally refined entertainment forms.Footnote 32 While such discourses have much in common with those that assisted the adoption of the phonograph elsewhere,Footnote 33 they also have uniquely Spanish traits, derived from Spain’s anxiety for renovation and Europeanization after the loss of its last colonies in 1898.

The mechanics of building a collection

Regordosa acquired his first phonograph relatively early in the gabinetes era, at some point between April 1898 and the end of 1899. We know this because the Edison Suitcase Standard Phonograph, model A, which he owned, was first launched on the former date, and because his flamenco recordings must have been made by the end of 1899, as these were recorded at the Fonda de Oriente in Cordoba, which was last active around that time.Footnote 34 It is possible that Regordosa acquired the device from a gabinete in Barcelona (where the first opened in April 1899),Footnote 35 but there is no evidence to support this suggestion, or to indicate whether he bought it elsewhere in Spain or imported it from abroad. Indeed, the only evidence of Regordosa’s connections with any of the gabinetes is a set of three cylinders from the Madrid-based Hugens y Acosta. Nevertheless, as I will argue throughout this and the next section, Regordosa’s recordings follow many of the conventions and practices introduced by gabinetes, suggesting that he was indeed more familiar with their recordings than his holdings indicate.

Regordosa’s background is in line with what trade magazines and advertising strategies reveal about phonograph buyers and users at the time in Spain. They were mostly men living in cities or sizeable towns, from a middle- or upper-class background and, in some cases, with a previous interest in or professional familiarity with applied science and technology. As a textile industrialist, Regordosa would have been familiar with technological innovations abroad. He was also active in a range of organizations representing the interests of business owners in Catalonia,Footnote 36 which suggests that he was sympathetic to some of the premisses of the nascent Catalan nationalism, particularly those regarding entrepreneurial activity as key to the economic development and modernization of the region. We can therefore imagine that the discourses of the gabinetes on technology, modernity and national identity would have resonated similarly with him.

Like many members of the Barcelona bourgeoisie, Regordosa was also engaged in philanthropic activities, particularly those concerning the Catholic Church,Footnote 37 and had a subscription to the Teatre del Liceu,Footnote 38 Barcelona’s opera theatre and a key centre of bourgeois sociability at the time. The Liceu was indeed key to Regordosa’s recording activities: most of the opera singers he recorded sang there between 1898 and Regordosa’s death in 1918 (see Table 1),Footnote 39 which suggests that he selected and perhaps contacted singers at the Liceu itself. As for zarzuela singers, the majority of them also appeared within these dates in zarzuela theatres in Barcelona.

TABLE 1 SINGERS NOT PERMANENTLY BASED IN BARCELONA WHO RECORDED FOR REGORDOSA

| Singer | Number of recordings |

Visits to Barcelona in the period

1898–1918 Footnote a |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pepita Alcácer | 6 | 1899, 1900, 1901, 1904, 1906, 1907 | |

| Lucio Aristi | 4 | 1901 | |

| Lina Cassandro | 2 | 1900 | |

| Concha Dahlander | 4 | 1901, 1903 | retired 1907 |

| Albany Debriege | 6 | 1903, 1910, 1913 | |

| Juan Delor | 2 | 1901, 1909 | |

| Ramona Galán | 12 | 1905, 1909, 1910, 1911, 1913 | |

| Edoardo Garbin | 2 | 1899, 1900, 1901, 1908, 1912, 1913 | |

| Marina Gurina | 19 | 1899, 1900, 1901, 1902, 1907 | |

| Josefina Huguet | 23 | 1898, 1900, 1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1907, 1908, 1910, 1911, 1914, 1915 | |

| Luis Iribarne | 15 | 1903, 1907, 1909 | |

| Rosalía (Rosalie?) Lambrecht | 2 | April–May 1899 | |

| Adriana Palermi | 6 | 1903, 1905 | |

| Andrés Perelló de Segurola | 8 | 1903, 1904, 1905, 1909 | |

| Amalia de Roma | 6 | 1900 | |

| Mario Sammarco | 6 | 1900, 1902, 1905, 1906 | |

| José Sigler | 4 | 1898, 1903 | died 1903 |

| Néstor de la Torre | 3 | 1903, 1904, 1905 | retired 1908 |

| José Torres de Luna | 5 | 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1908, 1910, 1914, 1916, 1918 |

a Data sourced from the theatre information section of the newspaper La vanguardia.

The cylinder cases themselves do not contain any indication of dates, but the Biblioteca de Catalunya has dated the cylinders themselves between 1898 and 1918, the year of Regordosa’s death. However, a cursory look at Table 1 suggests that Regordosa’s recording activities might have been concentrated in a shorter time span of 10 –12 years: indeed, few of the singers concerned visited Barcelona after 1910, and those who did were also in Barcelona before 1910. José Sigler’s recordings must date from before 1903, and those by Concha Dahlander and Néstor de la Torre from before 1907 and 1908 respectively, but there is no recording in the collection that was necessarily made after 1909 or 1910. There is other evidence: Regordosa recorded exclusively on two-minute brown wax cylinders, even though this often meant that he had to split longer numbers between two or more cylinders; four-minute wax cylinders would have proved more practical in those cases, but they were not introduced until 1908.Footnote 40 Moreover, in contrast with other contexts in which the gramophone and phonograph coexisted into the 1910s, in Spain the former replaced the latter almost completely after 1905, which might have made it difficult for Regordosa to source cylinders and other supplies.

The première dates of the works Regordosa recorded further confirm that his recording activities might not have extended into the 1910s, as the newest work he recorded dates from 1906.Footnote 41 Perhaps more significantly, they also offer insights into how Regordosa conceived of his recording enterprise. A significant number of the arias he recorded came from operas premièred at the Liceu between 1898 and 1902,Footnote 42 or from zarzuelas premièred at various theatres in Barcelona around the same dates.Footnote 43 We might imagine that some of those numbers would have been recorded relatively soon after their success on stage; this provides the first piece of evidence that Regordosa’s recording activities were inextricably linked to his experience of live music, using the phonograph as a technology of reminiscence in seeking to recreate and capture some aspects of the experience.Footnote 44 More evidence in support of this notion will be discussed in the course of the next two subsections.

The singers

Studying the singers’ names in Table 1 provides further insights into Regordosa’s unique recording practices. Indeed, whereas comparatively few singers at the top of the profession recorded for the gabinetes (owing to the inconsistent, often questionable quality of phonograph recordings and the laboriousness of recording sessions),Footnote 45 Regordosa consistently recorded performers of national and international fame. Regordosa’s bourgeois and industrial background probably incurred respectability in the eyes of performers. Similarly, the fact that the recordings were not to be released commercially would have dissipated any concerns about technical limitations or reputational damage. This is a first significant respect in which Regordosa’s collection departs from what we find in the catalogues of the gabinetes: it contains a few singers who never recorded commercially,Footnote 46 or who sang repertoire that they never recorded commercially. This opens up the array of recordings we have available for performance practice research, but at the same time requires us to be sensitive to the particularities and dynamics of home recording practices, as will be further discussed below.

The majority of Regordosa’s singers, though, did indeed record commercially: some for the gabinetes or for the Compagnie Française du Gramophone on its successive trips to Madrid and Barcelona from 1899 onwards,Footnote 47 others for the Milan-based label Fonotipia between 1904 and 1909.Footnote 48 This overlap opens up questions and provides some answers as to how singers might have acclimatized to and conceived of recording technologies in these early days – an issue that existing bibliography has sometimes highlighted. Answers are complicated by the fact that neither the gabinetes’ nor Regordosa’s cylinders are dated, and this makes it impossible, for example, to ascertain whether any given singer recorded for Regordosa first and then commercially, or vice versa.

The high technical standard of Regordosa’s cylinders, as well as his awareness of generic conventions, indicate that he was strongly concerned with quality, and he might have specifically targeted singers with studio experience or those who had proved to ‘record well’. However, it is also plausible that singers saw Regordosa’s home as a comparatively friendly setting in which they could acquire experience before offering their services to gabinetes or gramophone companies. A comparison of recordings by the same singers suggests that some indeed progressively learnt to adapt to the particularities of the recording medium,Footnote 49 suggesting that they came to Regordosa with comparatively little experience. For example, as recorded by Regordosa, Lucio Aristi’s Escamillo, Avelina Carrera’s Agathe, Juan Delor’s Fernando and Adriana Palermi’s Antonia come across as musically limited and poorly phrased: each of the beats is overly stressed, thus compromising legato and shaping.Footnote 50 There may be a technical reason for this: the difficulties in capturing lower frequencies in the earlier days of phonograph recordings often led pianists to overemphasize the beat in the left hand so that it would be audible.Footnote 51 It is therefore plausible that Regordosa’s accompanying pianist was doing precisely this, with singers initially following his lead and only later learning how to keep their phrasing intact while ignoring the piano. Support of this hypothesis is provided by the fact that other recordings by Aristi, Carrera and Delor, for example, show an improved sense of legato and phrasing, suggesting that they might eventually have become more comfortable with the recording process and learnt to ignore the particularities of the piano accompaniment, perhaps with directions from Regordosa himself.Footnote 52

The repertoires

Mapping out the genres and subgenres of the works represented in Regordosa’s collection offers further insight with regard to the way in which Regordosa might have conceived of his home recording activity. His collection mirrors, to a great extent, some of the choices and practices of the gabinetes, but it also extends them in significant respects probably connected with a desire to make the collection a memento of his live music experience. The two best-represented genres, opera (129 recordings of individual pieces) and género chico (31 recordings), are easily explicable: they were extensively represented in the gabinetes’ catalogues too, as these would be the preferred entertainment forms of their middle-class customer base, to which Regordosa also belonged.Footnote 53 Zarzuela grande (the full-length, ‘serious’ version of zarzuela, at its peak in the 1850s and 1860s and declining around 1900), however, numbered considerably fewer recordings in the catalogues of the gabinetes and only three in Regordosa’s collection. The operatic repertoire recorded is certainly in line with programming practices at the Liceu and the Teatro Real in Madrid at this time, and with both the gabinetes’ and Fonotipia’s catalogues. For example, Regordosa recorded only two Mozart arias (from Don Giovanni), but also recorded French grand operas which, though not completely obscure, are not often performed today, such as those by Ambroise Thomas and Giacomo Meyerbeer, and even Jules Massenet’s Manon. Bel canto from earlier in the nineteenth century is relatively well represented, but the main staple in Regordosa’s repertoire after French opera was verismo (including operas that have all but disappeared from the repertoire, such as Alberto Franchetti’s Germania), as well as Wagner and Verdi (two each of Ernani, Il trovatore, Aida and Otello – but no La traviata except for a clarinet fantasy composed on themes from the opera).Footnote 54

Several of the opera and zarzuela recordings were made by singers who sang the role on stage, and this provides further support to the notion that one of Regordosa’s motivations was to capture his own live music experience, and also helps further to refine the dating of the recordings. For example, Regordosa recorded Carrera on ten occasions, on one of which she sang ‘Leise, leise’ from Der Freischütz – which she was singing at the Liceu in May 1903.Footnote 55 This would indeed have been a rare occasion in Barcelona, as Der Freischütz had last been staged in 1886, and so Regordosa is likely to have seized the occasion to procure himself a memento of the performance. Further examples include Amelia González, who sang the title role of the successful operetta Miss Helyett in Barcelona in the spring and summer of 1901 and recorded it for Regordosa (perhaps around the same dates);Footnote 56 and Sigler, who was announced in the spoken introduction to his recording of La golfemia’s ‘Canción del abrigo’ as ‘creador de la parte’ (‘creator of the role’).Footnote 57

Next to those straightforward instances, though, we also find singers recording repertoire for Regordosa which they would not normally have sung on stage. This complicates the association that Regordosa (and his performers) saw between recording and live music, allowing us to expand our understanding of how the concept of performative fidelity worked in this context and connecting these recording sessions to domestic music-making practices with which Regordosa would have been familiar as a member of the bourgeoisie. Indeed, the live music experiences that Regordosa wanted to capture came not only from the stage, but also from more intimate settings.Footnote 58 Ramona Galán, an operatic lyric mezzo, and Gurina, commonly regarded as a good tiple with the vocal skills to perform demanding zarzuela grande roles, recorded the same aria, ‘Voi lo sapete’ from Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana. Galán self-consciously claimed in the spoken introduction that she would ‘try to sing it as best as I can’,Footnote 59 but Gurina’s recording reveals obvious vocal shortcomings, with high notes sounding particularly unstable.Footnote 60 Here again, as with the example above relating to Delor and others, we need to consider a multiplicity of possibilities: some recordings of the zarzuela repertoire, for example, in which Gurina would presumably have felt more at ease, display similar problems,Footnote 61 while others do not.Footnote 62 The ‘Voi lo sapete’ recording might therefore simply reflect Gurina’s efforts to adapt to the recording process; the difficulties of using wax cylinders in recording powerful voices such as Gurina’s;Footnote 63 or the problems inherent in making digital transfers of recordings.Footnote 64 So we should be cautious in drawing conclusions concerning timbre and vocal quality. What comes across in the recording rather unambiguously, though, is Gurina’s ability to deliver the text clearly and expressively. This was indeed one of the skills she would have been expected to display as a performer of zarzuela grande,Footnote 65 and so this recording can, at least indirectly, provide valuable information about performance habits in a genre that was at this time much more rarely recorded than opera.

A further example of a singer recording outside their usual repertoire comes from the tenor Ángel Constantí. Constantí, active in Barcelona and abroad, sang mostly lyric and spinto operatic roles on stage,Footnote 66 but he recorded Wagner both for RegordosaFootnote 67 and for the Barcelona gabinetes (Lohengrin’s duet for Manuel Moreno Cases and a passage from Die Walküre for the Sociedad Artístico-Fonográfica).Footnote 68 With the Liceu being a well-known Wagnerian hub, it is plausible that Constantí saw in recordings an opportunity to carve a niche for himself singing repertoire that he would not have performed on stage. Constantí ’s commercial Wagner recordings might also have led Regordosa to record him in that same repertoire, thus providing further evidence of Regordosa’s awareness of gabinete recording practices.

Other vocal genres in Regordosa’s collection are in line with the listening practices of the Spanish and Catalan bourgeoisie at the time and with the catalogues of the gabinetes. There are 12 Neapolitan songs (a genre that stayed popular in Fonotipia’s catalogue during the 1910s), but only one example of French- or German-language art song (Schubert’s Ständchen, by Josefina Huguet, discussed below). Flamenco, although indigenous to Andalusia, was by 1900 sufficiently popular outside its place of origin that it was widely recorded by gabinetes in Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia, and imported to cities throughout the country,Footnote 69 so it is not surprising that Regordosa recorded flamenco too.

There is one particular area, though, where Regordosa significantly deviated from practices of the gabinetes, and that is in his commitment to recording Catalan-language repertoire. There is no evidence that any gabinetes ever recorded vocal music in Catalan, and it is particularly surprising that those in Barcelona never did, considering the nascent movement among the local bourgeoisie to recover the Catalan language and culture. But the gabinetes industry in Barcelona was smaller, more fragmented and more precarious than that in Madrid, and in many respects lacked the leadership found in the capital, owners being less likely to innovate with respect to the choices that had proved popular in Madrid. Prejudice also existed with respect to the use of the Catalan language in a context that was as much technological as artistic. Indeed, while interest in Catalan-language literature and other cultural manifestations was reasonably widespread among the Catalan bourgeoisie, Spanish was still seen by many as the language in which to conduct business or research: the advertisements and other publicity of the Barcelona gabinetes were exclusively in Spanish, as were the spoken announcements at the beginning of the cylinders.Footnote 70

Regordosa’s collection thus provides us with a unique glimpse of the Catalan-language music movement that flourished in Barcelona in the early years of the twentieth century, including choral music sung by the Orfeó Catalá (of which more later) and solo songs (either traditional and arranged with piano accompaniment, or newly written by composers such as Josep Borrás de Palau, Anselm Maria Clavé, Lluís Millet and Pep Ventura). Soloists featured include not only Amparo Viñas and Emerenciana Wehrle (both connected with the Orfeó Catalá and known mostly for these types of repertoire), but also opera and zarzuela singers of Catalan or Valencian origin (Dahlander, Gurina, Huguet, Andrés Perelló de Segurola, Sigler) who spoke the language but rarely performed this repertoire in public.

The number of instrumental recordings in the collection (15) is minimal compared with the number of vocal ones, and this merits further examination. Scholars have repeatedly demonstrated that wax cylinders were more successful at recording voices than they were at recording instruments at this stage,Footnote 71 and that brass instruments were among the few that could be recorded to an acceptable standard: with brass-band music being also popular in Spain at the time, gabinetes recorded it extensively (almost a third of surviving commercial recordings are of brass bands). Symphonic, chamber and solo instrumental music was a different matter altogether, and recordings of these repertoires by gabinetes are extremely scarce, probably both because instruments such as the violin and the piano were particularly difficult to recordFootnote 72 and because it was opera and zarzuela, rather than instrumental music, that dominated the musical life of the Spanish bourgeoisie. Solo piano pieces in particular were often entrusted to the gabinete’s regular accompanist rather than professional concert pianists. Regordosa’s recordings depart in this respect from those of the gabinetes: he did not record any brass bands (perhaps because this would have required logistical arrangements beyond his reach), and although his collection of instrumental recordings is small, it shows a level of attention to these repertoires that goes beyond what was the norm for gabinetes, including a piano improvisation by AlbénizFootnote 73 and recordings by the Catalan pianists (prominent at the time) Joaquim MalatsFootnote 74 and Frank Marshall,Footnote 75 as well as the orchestral clarinettist Josep Nori.Footnote 76 It is likely that these can be further connected to Regordosa’s experience of domestic music-making.

A further instrumental genre that Regordosa never recorded is sardana – Catalan traditional music intended to accompany the dance of the same name. Sardana was extensively recorded by multinationals (Gramophone, Odeon, Pathé) from 1899, so it is surprising that Regordosa never recorded it. Reasons might include the fact that, being native to the Empordá area, sardana was only starting to spread to the rest of Catalonia in the years around 1900;Footnote 77 the technical difficulties involved in recording larger groups of instruments (sardana’s cobla features 11 instruments, combining brass, traditional shawms and a fipple flute); and/or Regordosa’s obvious interest in vocal rather than instrumental music.

Inside sound: announcements, phonographic form and performance practice

The discussion so far has demonstrated that, in seeking to achieve performative fidelity, Regordosa copied some of the practices of the gabinetes, yet also deviated from other widespread practices, perhaps partly in order to turn his recordings into mementos of his live music experience, both on stage and, more intriguingly, in the domestic sphere. In this section, I look more closely at the sound in those recordings in order to refine these tentative conclusions. I understand ‘sound’ here in a broad sense, not limited to performance practice issues, and indeed the next two subsections are concerned not with performance, but rather with questions about the broader organization of spoken and musical sound on the cylinders. These can be understood as part of what Feaster calls the ‘generic conventions’ of recordings, or ‘patterns of adaptation to technology in performance of early recordings’.Footnote 78 They include not only stylistic aspects of the performance, but also ways in which the performance itself is framed and presented.Footnote 79

I then go on to discuss performance practice issues in recordings by the singers Pepita Alcácer and Josefina Huguet and by the Orfeó Català choir. In these examples, I take into account my previous discussion of Regordosa’s unique way of understanding recordings as well as parameters that are by now well established in the study of early recordings as documents of performance practice: portamento,Footnote 80 vibrato,Footnote 81 large- and small-scale tempo changesFootnote 82 and ornamentation.Footnote 83 The very nature of musical performance dictates that the methodology of these and similar studies often involves close listening to and comparison of early recordings, with a view to ascertaining how these parameters were deployed for expressive purposes in a given context and what were, at a given place and time, the accepted conventions and boundaries for doing so (beyond individual style and preference). Here I expand our understanding of these conventions and boundaries by analysing this corpus of recordings; I also discuss examples of the possibilities presented by the Regordosa collection. Indeed, the collection allows us to hear performers, such as Alcácer, of whom there are no surviving commercial recordings, as well as pieces that were never recorded commercially on wax cylinders. But it also allows us to hear performers we know from commercial recordings, such as Huguet and the Orfeó Català, in a different context: in the relaxed atmosphere of Regordosa’s home rather than at the recording studio. Through careful comparison, this can help us not only further to understand the individual styles of specific performers and the ways in which these fit within the expressive code of their time, but also to expand our understanding of the recording processes of the time, both at home and in the studio, and how these might have affected the sounds we hear today; in turn, this can inform how we approach other recordings.

Announcements and the spoken word

Commercial cylinder recordings, in Spain and elsewhere, were typically preceded by a spoken announcement. This would normally include, as a minimum, the title of the piece, the name(s) of the performer(s) and the recording label.Footnote 84 The overwhelming majority of Regordosa’s recordings follow this convention, and a significant number (though not all) replace the information about the recording label with words to the effect that the cylinder was ‘pressed for Ruperto Regordosa’. This suggests, again, that Regordosa was familiar with the conventions of commercial recordings. Most cylinders also feature applause at the end, and often some bravos too – as did many recordings by gabinetes. Regordosa further followed the conventions of the gabinetes by putting on an Andalusian accent in the announcements of flamenco recordings.Footnote 85 In other respects he adapted the announcements to the particularities of his own practice. When a piece of music was split between two or more cylinders, the announcement was repeated at the beginning of each one, and in Catalan-language recordings the announcement was made in Catalan, which was certainly unheard of in gabinete cylinders.Footnote 86

A further trait that aligns Regordosa’s cylinders with generic conventions of commercial recordings (while distancing them from other amateur recordings, such as those of Pérez) is the fact that between the initial announcement and the final applause no sound other than the music itself is to be heard. There is no background noise or chatter, even though, as will be discussed shortly, other aspects of the recordings suggest that they would have been made in a relaxed atmosphere. This further confirms that Regordosa was consciously trying to produce recordings on a par with commercial cylinders, and it can also provide insights into the role that such announcements might have played in recordings from this era more generally. Feaster has convincingly argued that announcements did not simply serve a practical function, but were an integral part of the phonogenic enactment,Footnote 87 and he provides several explanations as to which function announcements might have served in this regard. Of these, two resonate particularly with Regordosa’s practice. The first of Feaster’s hypotheses is that announcements might have been intended as proof that the medium could handle the human voice.Footnote 88 In the case of Regordosa, we might add that the announcement proved that the recording was indeed being made in his home and not at a gabinete, as it was he, his wife or a friend (one of a small number of them, probably regulars in these sessions) who made the announcement.Footnote 89 This is not incompatible with the second hypothesis advanced by Feaster that is relevant here: that in those cases where cylinders were announced by the singer themselves, this would have worked as a sort of autograph.Footnote 90 In this case, though, the autograph would have been from Regordosa himself, not from the singer.

Notwithstanding Regordosa’s obvious efforts systematically to follow gabinete conventions with regard to the way in which he organized sound while at the same time providing evidence of his own contribution, his approach to the recording process was probably flexible, and a few of the recordings do indeed reveal that they were made in a relaxed, friendly atmosphere typical of domestic music-making. In Aristi and González’s recording of Miss Helyett, a group of friends is heard conversing after the music has finished; one of them recites a poem in a mocking tone, and the others subsequently congratulate him. Some singers (Aristi, Constantí, Gurina) introduced their own recordings, whereas Galán exchanged pleasantries with Regordosa at the beginning of her recording of Carmen’s seguidilla.Footnote 91 While we should not lose sight of the fact that some of these might be deliberately crafted to produce an impression of spontaneity that was indeed crucial for the generic conventions of the recording to work (as actually happened in some gabinete recordings), the overall effect is one of a relaxed atmosphere, less intimidating than the recording studio, where performance could easily be influenced by the performers’ disposition.Footnote 92 We must therefore consider the possibility that some of the differences we hear between Regordosa’s recordings and those by gabinetes of the same singer might be caused by differences in the environment, and by drawing on comparisons as well as written sources (as I shall do below), we must evaluate the extent to which each of these might reflect how the singer would have sounded on stage.

Cuts and edits

Even though the playable length of two-minute cylinders could be extended by slowing down the playing speed, a significant number of opera and zarzuela pieces would still be too long to fit onto a single cylinder, so cuts were a widespread commercial practice. Moreover, duets were often transformed into solos by extracting several substantial phrases from one of the duet partners and recording them one after the other. All this influenced how listeners engaged with recordings. Roland Gelatt claims that audiences in France, Germany and the US were put off by these practices and instead turned to the ‘less exacting entertainments’.Footnote 93 The short length of cylinders may have influenced performance as well, although the evidence is less conclusive here.Footnote 94

Regordosa’s collection can provide further insight into how these cuts and edits might have worked as generic conventions. Regordosa systematically cut arias and romanzas and transformed duos into solo pieces, sometimes making exactly the same edits as can be heard in commercial recordings, suggesting that he was familiar with those too. Nevertheless, he also departed from the practices of the gabinetes in choosing to divide long numbers between two or more cylinders.Footnote 95 Even though the gabinetes never explicitly explained why they avoided this practice, it is likely that splitting up a number would have been seen as impractical (it would have been more expensive for customers, and the cylinders would need to be kept together), as well as being disruptive of the illusion of performative fidelity. Regordosa’s choice, however, helps to present some of the repertoire in a new light, while suggesting that even though the practice of speeding up tempos might not have been widespread, it might have been used on some occasions. For example, when the soprano Amalia Campos recorded the drinking song ‘Es este Burdeos’ from Manuel Fernández Caballero’s zarzuela Chateau Margaux, she did so in a rather fast tempo, with little space for expressive changes in speed; the romanza thus comes across as rather mechanical.Footnote 96 Regordosa, nevertheless, made the decision to record Señora Pastor de Hernández singing the romanza over two cylinders. This allowed the singer extensive use of rubato and flexible tempo changes, probably making the recording more akin to what would have been regarded as a good expressive performance on stage.Footnote 97

Analysis of recordings, 1: género chico

One key strength of Regordosa’s collection is the potential it holds for the largely unexplored field of zarzuela performance practice: Footnote 98 indeed, since the genre was little recorded outside Spain at that time, Regordosa’s recordings constitute a small but significant percentage (almost 15%) of all surviving phonograph recordings of the genre. The question of how zarzuela (especially género chico) recordings positioned themselves with respect to, and came to evoke, aspects of the live music experience is particularly relevant here, further developing notions of performative fidelity in genres other than opera and classical music. Indeed, while wax cylinders could (to some extent) capture singing abilities, these were not the only measure by which a performer was judged by audiences and critics. Being able to deliver text expressively, both in the dialogues and in the singing, mattered at least as much as did acting and dancing skills:Footnote 99 recordings of género chico are indeed among the clearest demonstrations of the erasure of valuable information used by audiences to make sense of live performances.Footnote 100 Even though a systematic study of this question is yet to be undertaken, a cursory examination of available evidence suggests that the gabinetes took steps towards trying to bridge this gap. For example, recordings tend to emphasize clear and expressive delivery of the text, which would be key on stage as well. This could be achieved in several ways: by slightly shortening or elongating vowels to imitate the cadence of spoken speech;Footnote 101 by sacrificing vibrato or favouring quasi-parlato ways of singing; or by emphasizing stresses and pauses.

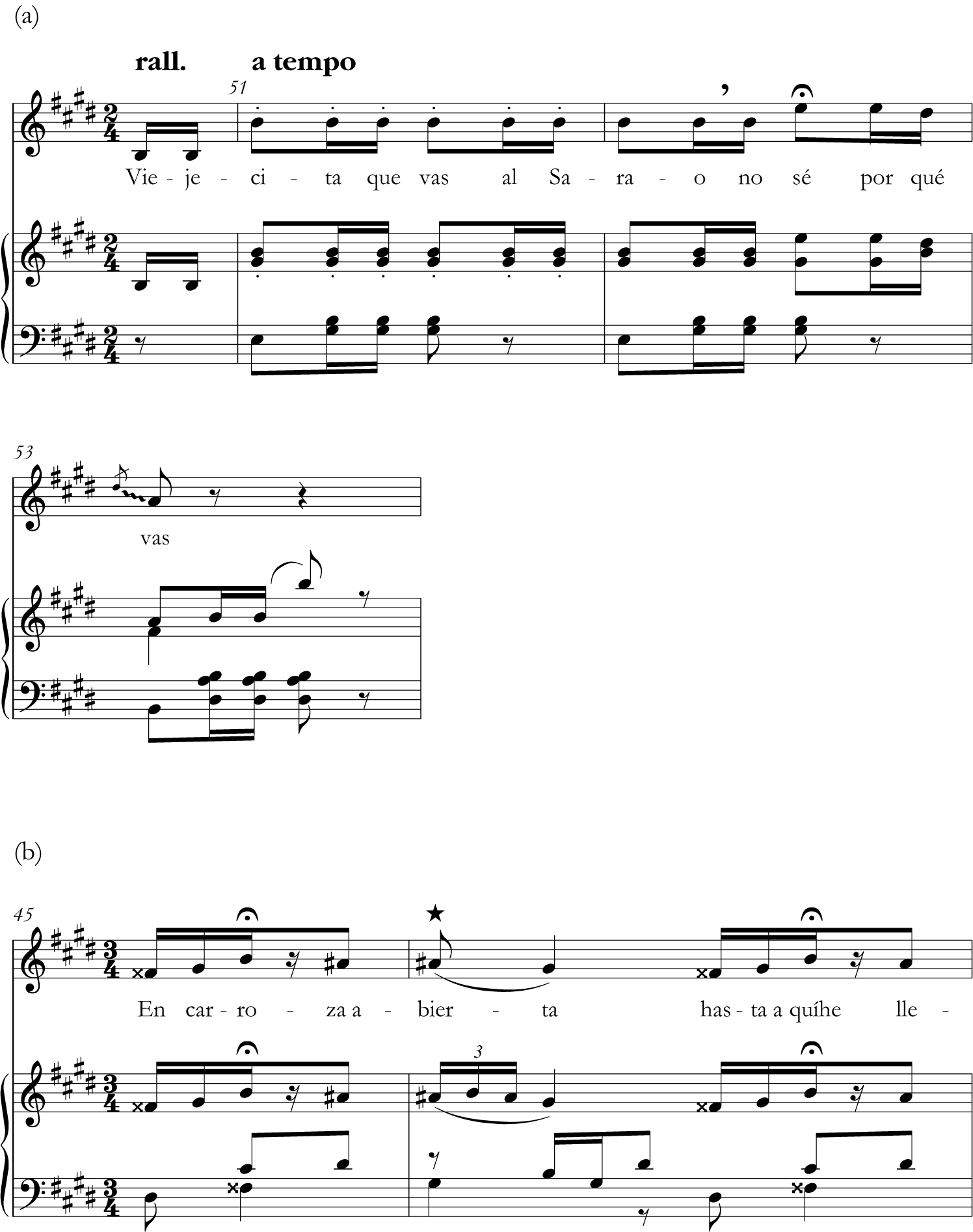

Alcácer’s recording of ‘Canción del espejo’, from Fernández Caballero’s La viejecita,Footnote 102 certainly falls within the practices and conventions of commercial recordings, and further confirms Regordosa’s commitment both to achieving professional standards and to providing singers with a relaxed atmosphere in which they could perform. Alcácer comes across as a singer with an excellent sense of text delivery, and her singing becomes almost recitative-like in the Andante gracioso (the second section) of the romanza (see Example 1a). She also generally shows an impeccable sense of where the pauses fall in the text and emphasizes them accordingly. Her musical decisions in the Andante mosso can also be connected with a search for expressiveness. The four initial lines of the text are sung rubato, seeking the natural cadence of speech; in the subsequent four lines, the third syllable of each (which is also the highest note in each of the phrases) is prolonged, which similarly gives the passage a speech-like quality (see Example 1b). These decisions, as well as the rather obvious tempo contrast between the Andante mosso and the Andante gracioso (♩. = 50 and ♩ = 33 respectively), are also in line with expressive devices we find in many recordings by gabinetes. In particular, the fact that large-scale tempo contrasts tend to be more pronounced than those observed in gramophone recordings suggests that this might have been a strategy used by gabinetes in order to compensate for some of the limitations that wax cylinders put on expressiveness (for example, the lack of dynamic ranges, or the issues with recording certain pitches).

Example 1 ‘Canción del espejo’ from Manuel Fernández Caballero’s La viejecita (piano-vocal score, Madrid: Casa Romero, 1897): (a) bars 51–3; (b) bars 45–9. In Example 1(a), the comma and fermata in bar 52 and the portamento in bar 53 are not in the original score and have been added to reflect Alcácer’s performing decisions in ‘Cuplé de La Viejecita, por la distinguida artista Srta. Alcácer’, Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona, CIL-361. The same applies to the fermatas and the simplification of triplets into quavers (marked with an asterisk) in Example 1b.

Our next step in trying to make sense of Alcácer’s recording might be to situate it with respect to written sources about her singing in an attempt to establish on the one hand whether the recording might be representative of her stage practice and on the other how her singing and text delivery were understood and appraised by género chico audiences and critics. We know that Alcácer was popular with audiences in Barcelona,Footnote 103 but she never rose to the level of successful primeras tiples in the Madrid theatres, who commanded high salaries and could make or break a new première. Like many jobbing singers at the time, Alcácer combined main roles in provincial theatresFootnote 104 with supporting roles and summer appearances in Madrid.Footnote 105 Reviews of such singers’ performances on stage tend to be scarce and unspecific, often offering generic praise without much detail. This makes it difficult to draw conclusions as to whether or not what we hear on the cylinder might be an accurate representation of singing on stage, and whether or not it might have been regarded as a good performance by contemporaries. A review early in Alcácer’s career conceded that she had a nice voice and could recite and move ‘like a true actress’, but sang ‘in a mediocre fashion’.Footnote 106 Similarly, the fact that other reviews highlighted her acting but did not mention her singing could be interpreted to mean that the latter was not deemed worthy of mention.Footnote 107 Other published reviews did highlight Alcácer’s singing, although in rather generic terms and without discussing her purely vocal skills; those reviewers might have thus appreciated her ability to deliver text expressively when singing, rather than the beauty or technique of her voice.Footnote 108

Alcácer’s limited singing abilities are confirmed, to an extent, by some aspects of the recording: she avoids interpolating high notes in suitable places, for instance, which at least one other contemporary recording of the same romanza does.Footnote 109 As recorded on the cylinder, the lower register does not seem to have been a strength of hers either, as her voice below G4 becomes breathy and out of tune. If we compare Alcácer’s recording with Lucrecia Arana’s in 1908 for Gramophone,Footnote 110 the differences are obvious, even taking into account the improvements in technology: Arana – the first to sing the role of Carlos on stage – takes a similar approach to expressiveness, making some of the same decisions as Alcácer, but her voice is more consistent in timbre and tuning.

One conclusion to draw from Alcácer’s recording, her reviews and comparison with other recordings from the period is that what audiences, critics and singers regarded as ‘good singing’ in género chico was not always synonymous with having a beautiful, well-ranged or trained voice. Instead, different singers would have had different combinations of skills, with several of those being regarded as acceptable within the parameters and tastes of the genre; among these, though, the ability to deliver text expressively was probably seen as crucial. At this early stage, commercial recordings mirrored and accommodated this multiplicity of approaches, as is obvious from the fact that singers as different as Alcácer, Arana and Blanca del Carmen recording the title role of La viejecita. Footnote 111 Regordosa’s collection suggests that the Barcelona recordist was keen to copy conventions from gabinetes and to put expressive text delivery at the centre of his practice; his recordings can thus be used and compared with commercial ones to ascertain further how género chico singing practices could vary from singer to singer.

Analysis of recordings, 2: Josefina Huguet

With 23 recordings to her name, the soprano Josefina Huguet is the best-represented performer in Regordosa’s collection. Most of her cylinders are of light lyric coloratura arias from French grand opera, bel canto and Verdi (Vêpres siciliennes, Un ballo in maschera), which were the roles on which Huguet, born in Barcelona in 1871, built her international career. Huguet also recorded rather extensively for gabinetes and for multinational companies. This makes her a particularly interesting case study, in that comparisons between recordings allow us not only to draw conclusions about her singing, but also better to understand the differences between commercial recordings and those made by Regordosa. For example, we might observe that Huguet’s timbre does not sound dissimilar in her recordings of ‘O luce di quest’anima’ (from Donizetti’s Linda di Chamounix) for G&T in 1902–3,Footnote 112 Victor in 1907Footnote 113 (both on disc) and Regordosa,Footnote 114 which might confirm (with some caveats) perceptions that Regordosa was indeed recording to high standards. Huguet’s coloratura becomes blurry below G4 in the Regordosa recording, and there are at least two possible explanations why this might be the case. The first has to do with the phonograph’s limitations in recording lower frequencies: this is the most plausible one, since these weaknesses are not obvious in Huguet’s Gramophone recordings. But there is also a possibility that this is indeed an accurate representation of Huguet’s voice: in coloratura sopranos such as Huguet, the stereotypical ‘white’, open, virginal timbre and developed flute register that we hear in their recordings often came at the expense of thinning the middle area of their voices.Footnote 115 Other than that, though, coloratura sopranos tended to record particularly well (in comparison with, for example, other varieties of sopranos with brighter voices),Footnote 116 and it is likely that both Huguet and Regordosa were well aware of her advantages: cuts and edits in Huguet’s repertoire are normally made in such a way as to maximize opportunities to display her coloratura abilities and high range, often including a generous interpolation of cadenzas. Huguet’s recording of ‘Ombra leggera’, for example, starts from the last Tempo primo and consists of a mere 16 bars of texted music before it goes into come scritto coloratura, which Huguet tops up with an extended cadenza at the end that takes her to a high E♭6.Footnote 117 Cuts, on the other hand, are roughly similar to those on her commercial recordings for Gramophone on discFootnote 118 and for Hugens y Acosta on cylinder,Footnote 119 suggesting further connections between commercial practices and Regordosa’s recordings in terms of how cuts were integrated into generic conventions.

A further area in which comparisons between commercial and Regordosa recordings are illuminating concerns cadenzas. In each of the three recordings of ‘O luce di quest’anima’, Huguet interpolates a cadenza; these show notable similarities, but are by no means completely identical (see Examples 2a–c). At a basic level, this proves that, in the early years of recording technologies, cadenzas were not yet standardized to the extent that they later came to be. With cadenzas being regarded as a locus for extended solo expression, these would be composed from stock patterns to suit the performer’s range.Footnote 120 Studying closely the similarities and differences between Huguet’s cadenzas can also shed light on her preferred patterns and tentatively refine chronology further. Indeed, among the examples below, the G&T and Victor cadenzas (Examples 2a and 2c respectively) are the least similar, while the Regordosa one has elements of both. This could suggest that the Regordosa recording was made in the years between the G&T and the Victor ones (1902–3 and 1907 respectively), with Huguet replacing certain stock patterns with others in the intervening years.

Example 2 ‘Ah! Tardai troppo’ from Gaetano Donizetti’s Linda di Chamounix, ed. Gabriele Dotto and Roger Parker (Milan: Casa Ricordi, 2007), bars 120–1, as transcribed by Eva Moreda Rodríguez from three recorded performances of Josefina Huguet: (a) ‘Linda di Chamounix: O luce di quest’anima’ (Barcelona: G&T, 1902–3; 53141 7241F); (b) ‘Allegro del primer acto de la Linda de Chamounix, cantado por la eminente diva Josefina Huguet’, Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona, CIL-328; (c) ‘O luce di quest’anima’ (Milan: Victor, 1907; 52529).

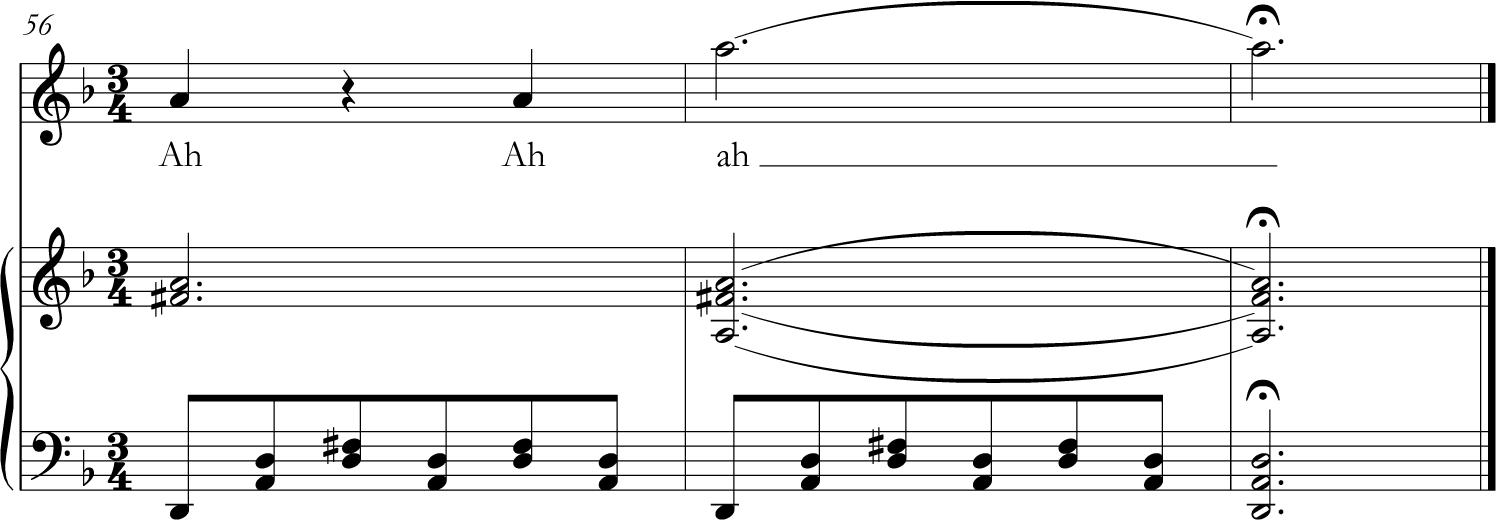

Of all the recordings Huguet made for Regordosa, the most unusual is that of Schubert’s Ständchen (introduced as ‘Serenata’ and sung in Spanish, even though the text is not clearly intelligible).Footnote 121 Huguet never recorded lieder commercially; neither has any gabinete recording of the genre survived. Gramophone and other multinationals, though, did start to record some of the best-known examples of the genre around these years, including Ständchen. Huguet’s is certainly very different from what we might consider a good performance today – but also, for example, different from Julia Culp’s 1914 recording for Victor,Footnote 122 one of the earliest to be documented. Huguet sings the song considerably slower (♩ = 55, compared with Culp’s ♩ = 73), which forces her to skip the repetition. Even accounting for potential difficulties with the technology, her middle–low and middle–high registers are uneven in tone, and her F5 in bar 23 sounds out of tune. Nevertheless, as in Gurina’s recording of ‘Voi lo sapete’, Huguet clearly attempts to be expressive by adopting strategies she used in coloratura repertoire – subtle ornaments, portamento (especially at the ends of phrases) and, in the opening phrase, a generous use of tempo rubato. Perhaps most surprisingly, she sings bars 50–2 an octave higher than written and interpolates an A5 in the last two bars (see Example 3). The recording is, ultimately, a rarity, but further helps to refine understanding of aspects of the collection. As with other examples of singers recording outside their repertoire, it points towards a relaxed atmosphere of domestic music-making and (as in the case of Gurina’s ‘Voi lo sapete’) helps us to see Huguet’s vocal habits in action – understood here, as defined by Plack, as ‘habituated patterns of behaviours which form the substance of one’s singing’ and that ‘become the substance of one’s style’.Footnote 123 It is not surprising that, when asked to record unusual repertoire in a relaxed setting, Huguet resorted to the habits she routinely used on stage for her preferred repertoire. The Ständchen recording is therefore not particularly valuable when it comes to investigating early twentieth-century lieder performance, but it might be useful in setting out what a singer like Huguet would have regarded as her usual palette of expressive devices and how she might have displayed them in recordings.

Example 3 Franz Schubert, Ständchen, from Schwanengesang, D.889, in Schubert’s Werke, Serie XX: Sämtliche einstimmige Lieder und Gesänge, ix, ed. Eusebius Mandyczewski (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1895), bars 56–8, transcribed by Eva Moreda Rodríguez from ‘Serenata de Schubert, cantada por la eminente diva Josefina Huguet’, Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona, CIL-346.

Analysis of recordings, 3: Orfeó Català

Apart from its role as a cultural hub for the promotion of Catalan culture, the Orfeó Catalá choir attained international renown for its performances of the canonic choral-symphonic repertoire. It was recorded by Gramophone as early as 1899 on its first visit to Barcelona,Footnote 124 and then again regularly during the following years, with a full batch of recordings in Catalan released in 1916,Footnote 125 as well as forays into the standard repertoire, such as Beethoven’s Missa solemnis in 1927 for Victor.Footnote 126 Regordosa himself recorded the Orfeó Català on five occasions. The choir was, however, never recorded by gabinetes, who rarely recorded choral music other than opera and zarzuela choruses with piano accompaniment. Regordosa’s recordings are therefore interesting in that they not only document a Catalan-language vocal tradition never captured on the phonograph before, but also help us understand the difficulties the phonograph posed when recording choirs, and the ways in which Regordosa tried to solve those difficulties in order to create the illusion of performative fidelity.

Regordosa’s recordings of the Orfeó Català show that he must indeed have struggled, and the results are, overall, among the least satisfactory in his collection. A cursory listen to any of his choral recordings reveals that he did not record the whole choir, which in those days counted a membership of about a hundred, but a much smaller number of singers – though not as small as the recordings by gabinetes of opera and zarzuela choruses, which were often made with no more than five or six performers. With these relatively high numbers, the four-part texture comes across as rather indistinct in Regordosa’s recordings, with the text being practically unintelligible. Nevertheless, if we compare Regordosa’s recordings of Clément Janequin’s Le chant des oyseaux (translated here as L’aucellada)Footnote 127 and the Catalan-language song El cant de la Senyera by Lluís Millet,Footnote 128 we can hypothesize that Regordosa might have improved his techniques in recording choirs progressively, probably by means of trial and error. In L’aucellada, the dynamics and tempo are kept steady. In particular, the last section, where each of the parts imitates different types of birdsong, is of limited effectiveness: it would probably have necessitated the articulation to be bolder, the consonants sharper, for it to achieve the effect it would have had on stage. L’aucellada was indeed one of the Orfeó Català’s most popular pieces at the time. El cant de la Senyera, however, even though the cylinder has now considerably deteriorated, shows an attempt at recording dynamics that might come across as rudimentary but is still significant for this era, including an effective piano subito before the last phrase, considerably improving expressiveness.Footnote 129

Conclusion

I return to my original questions. What does Regordosa’s collection reveal about home recording practices in the era of the phonograph? And how should these practices inform future research into the collection specifically focused on performance practice issues? This conclusion needs to reiterate two caveats. First, sources, both aural and written, for the study of this culture are scarce, which makes it difficult conclusively to reject or confirm any hypothesis. Secondly, there are reasons to think that Regordosa might have been an outstanding recordist – in terms both of the sheer number of cylinders he produced and of the technical and artistic attention he put into his recordings. Hence, the conclusions we might draw from his recordings might not always be easily applicable to Miralles Segarra, Pérez or Aznar, and it is likely that they are not applicable also to the multiplicity of amateur recordists operating in Spain and elsewhere at the time.

One initial observation we might draw from Regordosa’s collection is the rather surprising rapidity with which generic conventions implemented by gabinetes might have been adopted by some amateur recordists. None of Regordosa’s recordings suggests that he might have experimented with less formalized, more rudimentary ways of presenting and organizing sound typical of earlier, non-commercial experiments. Instead, they all follow (to the extent I have described above) the generic conventions used by the gabinetes, with the caveat that Regordosa captured and reflected his experience of live music not only on stage but also in the privacy of his home, as was the norm with individuals from his social class at the time. This introduces nuance to the processes of phonographic literacy and performative fidelity that dominated the early years of recorded sound history, suggesting that once improvements to the phonograph had made it appropriate to the domestic sphere, the commercial and cultural changes that accompanied it and that gave rise to the recording as an aesthetic product and commercial artefact unfolded relatively quickly. This makes Regordosa’s recordings both easy and difficult to read at the same time. They are easy to read in so far as we can assume that Regordosa’s recording practices were part of more widespread processes by means of which recording labels, performers and audiences active in the early years of recording technologies developed recording practices that crystallized into a certain notion of performative fidelity. But they can also be difficult to read to the extent that while we know that each of Regordosa’s recordings would have called upon these processes, we often do not know exactly how each of them did so or what role each played in his experiments.

Specific sonic features in the recordings must thus be discussed and contextualized within what we know about recording practice in Spain and elsewhere, and also within Regordosa’s collection as a whole, with the caveat that, as suggested above, the lack of evidence in some respects might make it difficult to confirm or refute hypotheses. We must bear in mind that each of these recordings was unique, having been shaped and affected by the multiplicity of factors discussed here, and each recording must therefore be discussed individually. Nonetheless, I wish to conclude this article with three general lessons drawn from my analyses above, capturing some of the respects in which Regordosa’s collection (and, perhaps, other amateur recordings) differed from commercial recordings of his time. First, we must consider how the different types of setting (the recording studio versus a private household) might have influenced a performer’s disposition, and whether on this basis some recordings can be regarded as more representative than others in capturing a performer’s abilities as heard on the stage. Secondly, a private setting such as Regordosa’s might have made performers more likely to record pieces outside their normal repertoire. While we must be cautious in using these factors to draw conclusions about stage performance, they can be invaluably helpful in further understanding issues of individual style and habits, and the ways in which performers developed a palette of expressive possibilities upon which they could draw according to the context. Thirdly, Regordosa’s collection gives us a rare glimpse into a specific recordist’s strengths and weaknesses, and (even in the absence of precise dates) how these might have changed over time. This can help us to understand the learning processes of other recordists, professional or amateur, and how these might have influenced, for better or worse, what we hear in specific recordings.