Until 1854, the date of publication of Westergaard's Zendavesta,Footnote 4 Europe was unacquainted with the Iranian recension of the Xorde Avesta. In his edition Westergaard was able to make use of three Sāde manuscripts for the first time, which he himself acquired during his stay in Persa between 1841 and 1844: 6115 (K36 [= M1]) (IrXA Sāde) from 1724, 6870 (K37 [= M2]) (IrXA Sāde in NP script + Faroxšī) from the 19th century, 3100 (K38 [= M3]) (Faroxšī, very close to 3095 [Suppl.persan1191]) from 1814.Footnote 5 This material was not much enlarged in the Geldner edition published three decades later. Besides the IrXA Pahl. mss. 7075 (F2) and 7085 (L12) Geldner added the following Sāde manuscripts to the three Westergaard ones: ms. 6095 (MF3) (IrXA Sāde + Faroxšī) from 1700 (of which 6090 [MF51] is a copy) and Wilson's mss. 6195 (W1) (IrXA Sāde) from the beginning of the 19th century and 6297 (W3) (IrXA Sāde + Faroxšī), an Iranian ms. written in India in the 19th century,Footnote 6 and finally the fragmentary ms. 6220 (Lb16) (< 1835). Besides these manuscripts used by Westergaard and Geldner, we have knowledge of some other Iranian manuscripts and their contents through the catalogues: the IrXA Sādes 6110 (MF29) from 1704; the IrXA Sāde + Faroxšī (?) Katrak90 from 1718; the ms. Katrak165 from 1791; the undated ms. Katrak166 which contents indicate its Iranian origin.Footnote 7 Of Iranian origin is probably also 6145 (MF26 = MF1) and the fragments 6291 (Ethé1943) and 6295 (MF40). Quite numerous are the XA Sāde manuscripts written in NP script which were, however, besides K37 never used in editorial work: the Sammelhandschrift Katrak96abc (1735+1789); 6855 (MF43) from 1797, written in India with traces of Indian reworking; 6860 (MF75) from 1807; 6865 (IOL CCXXI) in two parts from 1827; Katrak563 and Katrak683, designated as “very old” and “old” by Katrak; 6875 (R25) and 6880 (MF76) of unknown date. Even more numerous are the Iranian Faroxšī manuscripts. Some of them were recently described by Andrés-Toledo,Footnote 8 among them ms. 3055 (Yazd3973) with colophons pointing to the years 1607 and 1717 ce, and ms. 3060 (ML15286) from 1697 or 1717 ce written by Rostom Goštāsp Erdašīr. His name appears also in the first colophon of 3080 (MF16 = MF1) which gives a date 1721 ce. The Iranian Faroxšī manuscripts, produced until the middle of the 19th century, include mostly the Faroxšī text only, and only very few manuscripts combine these texts with other liturgies (mostly Nērangs). The most extensive manuscripts are K38 and (the closely related) Suppl.persan1191, ML15286, MF16.

In general, we can see that the production of Iranian manuscripts other than the Faroxšī ones belongs to two strata: firstly the manuscripts of the early 18th century which were nearly all written by Rostom Goštāsp Erdašīr; secondly, the manuscripts from the beginning of the 19th century. Thanks to A. Cantera and his pupils, over the last ten years more XA materials from Iran have come to light. Two of the most comprehensive IrXA Sāde manuscripts are the IrXA Sāde ms. 6135 (YL2-17) from 1723 and the IrXA Sāde + Faroxšī ms. 6187 (MZK6) from 1803. While YL2-17 is valuable because of its age, content, and its scribe Rostom Goštāsp Erdašīr, MZK6 is extremely important since it is one of the very few examples of an extensive IrXA Sāde from the early 19th century that at present can be examined. MZK6 will be used to answer two questions: a) to what extent does the Iranian composition of an XA Sāde depend on the scribe and his time or on general conventions? b) to what extent does the quality of an Avestan text of the early 19th century correspond to that of the early 18th century?

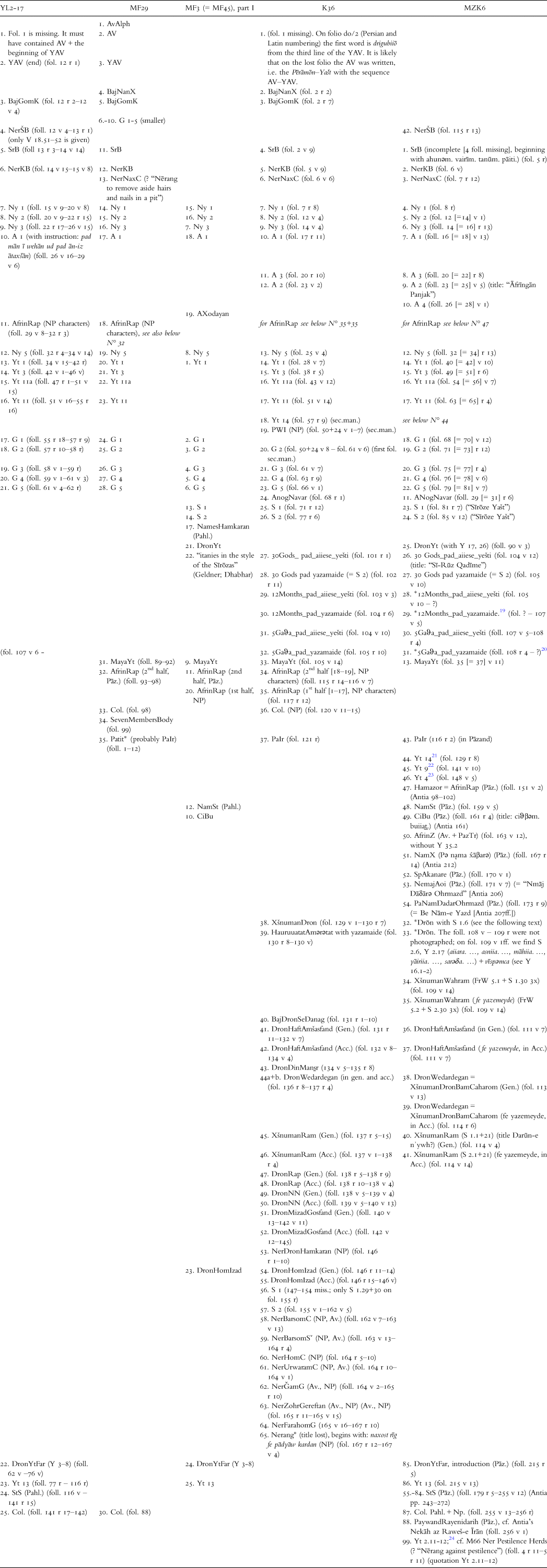

Table 1. Overview of the mss. of the IrXA Sāde

*

The ms. 6135 (YL2-17–02233) from the Yegānegi Library Tehran was written in 1723 ce (1072 + 20 Y) by Rostom Goštāsp Erdašīr.Footnote 9 It consists of 142 foll. of 16–17 ll. each. The old part is written in a very pleasant Avestan script, partly in NP, the page has a framed type area. There are some NP writing on the margin. Fol. 45 v seems to be damaged by water. The folios that once contained Yt 11a 3–8 are missing. Fol. 46 r is partly restored, the text supplied by a second hand; on fol. 46 v the text is lost because of this restoration. Fol. 2 r has a note in NP, on fol. 3 r Y 0.1 is written in a very unpleasant script. Then follow some blank folios. On fol. 9 r Y 4.23 is written, again in a very unpleasant script. YL2-17 has the same text sequence as MF29 (see below), but at the end a Faroxši is appended.

The colophon is in Pahlavi (foll. 141 r 17–142) and gives at first the date of writing and the name of the scribe.Footnote 10 The scribe, Rostom Goštāsp Erdašīr, adds some pious formulas which resembles those of the first col. of Ms. B [Dēnkard]. As in colophon 1a of the Dēnkard ms. B (B 641.5-11) the creed (ʾstwbʾnyh) is designated as that of ʾstwbʾnyh pṯ' ʾpyck wyhdyn' mẕdysnʾn ʾpl ʾšt<k>yh <y> ʾhlwb' plwʾhl zltwšt' y spytʾmʾn' lʾst' psʾcšnyh ʾtwr'pʾt' y mhr'spndʾn'Footnote 11 (āstawānīh pad abēzag weh-dēn ī māzdēsnān abar aštagīh ī ahlaw frawahr Zarduxšt ī Spitāmān rāst passāzišnīh ī Ādurbād ī Mahraspandān) of the Good Religion according to the message of Zardušt and of the right canon of Ādurbād Mahraspand.

Ms. 6187 (MZK6_XwAIsf1) was written in 1803 ce (1172 Y) and is today part of the collection of the Muze-ye Zartoštiyāne in Kermān. The colophon on fol. 255 r is written in (a faulty) Pahlavi and gives a date Šahrewar/Wahman/1172 Y; the appended NP colophon gives Šahrewar/Wahman of the “old year” 1173. In the Pahlavi colophon the designation “<era of> Yazdegird” is enlarged by the expression nāfag (nʾpkFootnote 12) be ō ī Husraw šāhān šāh Ohrmazddān “the grandson to Husraw (II), king of kings, son of Hormizd (IV)”. The writer is Esfandyār Nūšīrwān Erdašīr Esfandyār Sīstānīg who is known also from some manuscripts belonging to the complex of the Long Liturgy. A manuscript closely related to ms. 6187 is the ms. 6190 (RR3) from the Rostami collection. This manuscript is complete in the beginning (Alphabet; AV + YAV; SrB). After Yt 13 it appends about 50 further folios which contain Nērangs (such as the Barsom Cīdan [fol. 225 v 10]), the ceremony for the dead ones, the Yašt Gāhān (on foll. 254 v − 273 r 10, finished with the year number 1298 <Y>), the Paδuuaṇt Rainīdārə (on foll. 273 r 11 − 275 r), Yt 2.11-12 (on fol. <275 r>, at the end of the ms.), and the yātu.zī. zaraθuštra., i.e., the Nērang against pestilence (cf. M66). The Paδuuaṇt and the yātu.zī. are appended in ms. 6187 after the colophon.

Pahlavi colophon: plcpt pṯ' ŠRM W šʾtyh W plhwyh <W> lʾmšn' pṯ’ nywk’ yhšn’ W hwp mwlwʾk hwʾstkFootnote 13 dlstk’ lwcgʾl ʾpstʾg hwwlsFootnote 14 (?) lstk ycšnykFootnote 15 dʾtw <b>lFootnote 16 dyn’ bwndk dstwbl yspnyʾl nwšylwn' (w)ʾlšyl (w) yspnyʾl systʾnyk npštwm prʾc *ŠBKWNštwmFootnote 17 pṯ' dʾtwl(ʾ) ʾwhrnzd pṯ' plhwyh pylwc YWM štrwl BYRA whwmn’ ŠNT’ bl 1000 W 100 hptʾt W 2 yzkrt' MLKA(y)ʾn’ MLKA’ nʾpk BRA OL y hwslwby MLKAʾn’ MLKA ʾwhrnzddʾn’ pṯ' yẕdʾn’ kʾmk’ YHWWNʾt’

New Persian colophon: newešte šod be-xaṭ-e faqīr-ḥaqīr-kam<t>arīn dastūr Esfandyār dastūr Nūšīrwān dastūr Esfandyār dastūr Erdašīr dastūr Ādarbād Sīstānī neweštom, ferāǧ-heštom fe ašāye (ʾšʾyh) fīrūzgare xorrame andar rūz-e rāmešn-gare rūz Šahrīwar o Bahman-māh qadīm sane 1173 fe yazdān o amšasfandān kāme bād

*

In the following the contents of YL2-17 and MZK6 are given in comparison with Rostom Goštāsp's manuscripts MF29, MF3 and K36. While YL2-17 resembles especially MF29,Footnote 18 MZK6 is similar to K36. The overview shows that Iranian XA manuscripts not only follow a more or less stable textual sequence (the same is true for Indian manuscripts), but that the manuscripts belong to different types (see below) which do not always have a correspondence in the Indian tradition.

Table 2. Detailed overview of the contents of Iranian Xorde Avesta Sāde mss

With the edition of Geldner and the Avesta translation made by Wolff on the basis of the Altiranisches Wörterbuch, the following order of Xorde Avesta text classes was established:

Introductory prayers – Niyāyišns – Gāhs – Yašts – Sirozes – Āfrīngāns

A comparison of all manuscripts of the XA proper—i.e. of those XA manuscripts that are not unstructured anthologies and that do not belong to the TXA class—that are available at present or at least well described in catalogues (currently: Sāde 12 Ir. / 20 Ind. mss.; PahlTr 3 Ir. / 24 Ind. mss.; NPTr 3 Ir. / 8 Ind. mss.; SkrTr 14 mss.; GujTr 23 mss.) shows that Geldner's order is not arbitrary. With the exception of the two Sīrōzes which seem to be intruders from a part of the XA manuscripts that belong to the Iranian Sāde tradition (and to the oldest Indian manuscripts) but that became lost in the later Indian Sāde tradition (since the 18th century),Footnote 25 Geldner's order is in accordance with the order of the manuscripts, in particular with the Indian ones (see the position of the Āfrīnagān):

Table 3. Sequence of text classes in the Iranian and Indian Xorde Avesta

This general order is reflected in the Iranian Sāde manuscripts. As we can see in our table, the manuscripts of this group comprise five sections:

Table 4. General overview of contents of Iranian Xorde Avesta Sāde mss

It is only section I that was a regular part of any Iranian manuscripts except in the Faroxšī ones. In reverse to XA manuscripts that consist of the Farẓiyāt plus one or more other liturgical section, the Faroxšī class integrates only texts from section II, III, V (most important are the mss. MF16Footnote 26 and K38Footnote 27). It is also section I that is constitutive for all classes of XA manuscripts with translation and for the Indian XA in general. If we leave aside the TXA manuscripts (this class is attested only in India) which can include in its later parts the Xšnūman liturgies, the Indian XA was restructured as follows:

a) The Drōn and the Faroxšī became part of a separate manuscript transmission;

b) from the Sīrōze litanies only the litany Sīrōze Yašt (known as Sīrōze 1+2) was adopted in some mss.;

c) the Mayā Yašt appears in the formation “Niyāyišn 4” and became part of the text class “Niyāyišn”;

d) although PaIr is not totally absent in Indian mss. (it is part of some Sāde mss.), Indian mss. include often three other Patits: PaAd, PaRo, PaXw. These Patits occur often together with the two Āśīrwāds (Pāzand and Sanskrit). The Indian mss. include many other smaller texts/liturgies (mostly Pāzand or Pāzand with Avestan quotations) that are unknown in Iran: Āfrīns, Nērangs (charms), smaller prayers.

It is striking that MZK6 comprises all five sections. Thus, the impression arises that MZK6 is an attempt to create a comprehensive Iranian XA.

*

A remarkable point in MZK6 is its extensive use of Pāzand (Avestan script used for non-Avestan texts). The probably oldest attestation of Pāzand in Iranian manuscripts is ms. T30, the original ms. of the so-called Rewāyat of Kāma Bohra (= Kāma Asa Khambayeti) from the year 896 Y (1527 ce). While its second part is written in New Persian, its first part, the first 99 folios, has a Pāzand notation. Pāzand was used in T30 because of its purpose; written by Šahriyār Erdašīr Eraj Rostom Eraj in conversation (hamporsagī) with Gīw,Footnote 28 it was sent to the Indian community. We have no indication that also MZK6 was written for the Parsis. Instances of the use of Pāzand in Iran in the early 18th century are extremely rare. One example is the StS on foll. 57 v – 110 r in the Faroxšī ms. ML15286Footnote 29 of Rostom Goštāsp Erdašīr from the year 1716/1717 ce; another example can be found in Rostom Goštāsp Erdašīr's MF3, in which the second half of AfrinRap (part I of the ms.) is in Pāzand, while the first half is in NP (StS [part II of the ms.] is given in Pahlavi in MF3). But in general, Iranian manuscripts produced for use in Iran prefer New Persian or Pahlavi, see, for instance, the Iranian XA transmission of the NamSt:

Table 5. Attestations of the Nām Stāyišn in Iranian Xorde Avesta mss

While the use of Pāzand is the common practice of the Parsis for adapting texts from Iran (Pāzand being the only alphabet both Zoroastrian communities were acquainted with) or to compose new liturgical texts, the liturgical use of Pāzand in Iran is a break with convention. It seems that it was provoked not by a practical, but by an aesthetic, consideration: that all texts of a liturgical manuscript should appear in dēn dibīrīh.Footnote 30

*

Among the non-Avestan texts included in MZK6, the NamSt is a text widely attested. The reason for the numerous attestations of the NamSt is its connection to the daily prayer obligations described in Dk 3.81 (ms. B from 1659), which chapter gives the text of the NamSt completely (B 59.10-60.12) (the liturgical frame, however, is missing). Unfortunately, neither MF3 nor MF28 or MF16 are available by photo. However, MF3 was used by Dhabhar (as “Mf4”), so that we have at least its readings in the apparatus.Footnote 31 For the Iranian tradition of the NamSt our best attestations besides MZK6 are:

a) the text of the NamSt given in Dk 3.81 (Ms. B)

b) the Pāzand version in the Kāme Bohre Ms. (T30).

Among the manuscripts used by Dhabhar, the Iranian Pahlavi tradition is reflected also in 7183 (U1) and in 9170 (E = J58). Dhabhar's information on a ms. “MF3” is very short.Footnote 32 It is, in fact, the ms. 6295 (MF40)Footnote 33 which consists of three parts: I) NamSt (Pahl.); II) StS (Pahl.); III) (an incomplete) XA (upto Ny 1).

IndXA manuscripts include the NamSt more frequently than Iranian manuscripts. The oldest attestations of the text are the two Pāzand versions given at the beginning and end of 6550 (F1)Footnote 34 which are more or less identical with each other and close to the text given in Antia's Pāzand Texts.Footnote 35 Dhabhar used five later Indian manuscripts: 7125 (MR = T10) (1844 ce); 7180 (A = T11) (after 1844 ce); 7183-5 (U1-3) of unknown date. Two questions arise concerning the Pāzand version of the NamSt in MZK6:

1) Is the Pāzand used by Esfandyār Nūšīrwān different from the Pāzand used in Indian manuscripts?

2) What is the relation of the NamSt in MZK6 to the Iranian and Indian transmission in general?

Regarding (1): Besides the fact, that the Pāzand used in Indian manuscripts is always difficult to read because of its numerous examples of wrong punctuation, its confusing vocalism, and the misreadings of Pahlavi words, there are at least two particular conventions in the Indian Pāzand transcription of Pahlavi: Pahl. -yh → Pāz. -š and Pahl. u-š (APš) → Pāz. azaš. / ajaš. Both conventions are absent in the NamSt MZK6, and they are also absent in T30. In general, we can observe that the Pāzand in MZK6 (and in T30) shows far less orthographic unsteadiness than the Indian manuscripts. Regarding (2): The comparison of the NamSt text given in MZK6 with the Iranian and Indian transmission (Pahlavi and Pāzand) proves its affiliation to the Iranian branch. It is known that Dhabhar created a hybrid “Pahlavi Xorde Avesta”. He not only put together Pahlavi translations and texts that were never part of one and the same tradition, but his critical text is an arbitrary mixture of Iranian and Indian readings. As long as important Iranian manuscripts are hidden from our view, we have to work with the critical apparatus of Dhabhar's edition and use it as a tool for restoring the Iranian text. When we do this, we see that the Pahlavi text of the NamSt transmitted in the IrXA agrees more or less completely with that of Dēnkard 3.81. Since we know that the Pāzand text of the NamSt in T30 was written in Iran, we can expect its closeness to that in ms. B or MF3. For the Indian side, we have, as mentioned above, the two Pāzand attestations of the NamSt in F1 from 1591 and the Pahlavi attestations (which are all late):

Table 6. Text critical overview of the Nām Stāyišn in the Xorde Avesta mss

The comparison of the readings shows that the Indian tradition of the NamSt – F1, IndPahlXA, later Pāzand mansucripts—and the Iranian tradition, Dk 3, IrPahlXA, T30—form two branches of transmission. MZK6 clearly belongs to the Iranian branch. Because of the attestation of mą̇θraspəṇd. in §4 in T30, an Indian contamination of MZK6 can be excluded.Footnote 42 If Dk 3.81 frahangān frahang should not be a mistake for original *frahangān frahang mahraspand*, §4 points to a common text of the NamSt which is younger than that of Dk 3 and the common point of the Iranian and Indian Branch (“x”). Within the Iranian branch it seems likely that the text of MZK6 is a transcription of an Iranian Pahlavi version:

*

nēk jahišn ud xūb murwāg bawād