When I was young it was a time when the Kangxi Vajra [Emperor] was ruler of China. In Central Tibet [T. Dbus gtsang], the ruler was the grandson of the Holder of the Teachings Dharma-king Güüshi Khan, Lhazang Chinggis Khan. And the king of Kökenuur was Güüshi's youngest son, the Noble Reverend Prince Dashibaatar. In Zungharia the ruler was the Mongol King Tsewang Rabtan. And, in Torghud country the ruler was Ayuuki. During their lifetimes, the philosophy and practice within the establishments of lamas and monks in all places were like the waxing moon, and the desired virtues and wealth of house-holders like a summer lake. Therefore, regarding the happiness [caused by] the benefits of religion and state, it was an auspicious time that rivalled the lands and inhabitants of the gods’ pure realms.

Sumba Kanbo Yeshe Baljor (1704-88)Footnote 1

Introduction

On 11 February 1724,Footnote 2 Nian Gengyao 年羹堯 (d. 1726), the governor-general of Shaanxi and Sichuan and General-in-Chief for the Pacification of Distant Lands, carried out a devastating attack on Gönlung Jampa Ling,Footnote 3 the largest and perhaps most influential Tibetan Buddhist monastery of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries in Amdo.Footnote 4 The monastery housed as many as 2,400 monksFootnote 5 and was the central authority in an extensive network of branch monasteries and subject populations north of the Xining River 西寧河 (also known as the Huangshui 湟水) and stretching north even beyond the snow-capped mountain ranges separating present-day Gansu and Qinghai Provinces. Significantly, the monastery also housed the remains of the late Dashibaatar (1632–1714), who was Güüshi Khan's youngest son and the ruler of the Khoshud Khanate in Kökenuur.Footnote 6 Dashibaatar's son, Lubsang-Danzin, had launched a series of attacks on his Khoshud rivals and on Qing forts along the Gansu-Kökenuur border. He rejected the titles that the Manchu Qing Court had bestowed on him and his fellow Khoshud nobility when they submitted to the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661-1722) in 1698.Footnote 7 The monks of Gönlung Monastery, which had been the beneficiary of Khoshud patronage since the Khoshud and their Zünghar allies first settled in Kökenuur in the 1630s, joined Lubsang-Danzin in attacking Qing frontier forts.

The Qing forces, led by Nian, were quick to respond. Nian directed over 8,000 troops to surround Gönlung and adjacent valleys.Footnote 8 In the course of that February day, more than 6,000 monks and other subjects of Gönlung were killed.Footnote 9 By all accounts the destruction was total and devastating. Sumba Kanbo Yeshe Baljor, who was a young lama studying in Central Tibet at the time, would later write, “monasteries became like crops hit by hail, and monks left their residences, becoming like the moon dancing on the water [i.e. they vanished like an illusion]. Chuzang RinpochéFootnote 10 and some twenty other dharma-kings and elderly monks were also offered to the fires. … … The monastics were like mice killed by a hawk [and] forced to scatter like a small hair carried by the wind”.Footnote 11 The Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723-35) had given his full support to Nian Gengyao's actions, responding to the insolence of the monks by remarking that “it would be a most happy and comforting affair were you in that distant land to oblige us by slaying them and properly managing the affair”.Footnote 12 Ironically, the emperor attributed the success of the imperial army to “the benevolence and protection of the gods” and “the manifestation of the Buddha and the gods”.Footnote 13

The destruction stretched to include most of the other important monasteries north of the Xining River, a region known in Tibetan as Pari (T. Dpa’ ris),Footnote 14 including Semnyi (T. Sems nyid dgon), Chuzang (T. Chu bzang), Serkhok (T. Gser khog dgon; Gönlung's erstwhile branch monastery that had come to rival Gönlung in size and influence) and many other monasteries.Footnote 15 Even the famed Kumbum Monastery (T. Sku ’bum dgon), which was located just across the Xining River, south of the Xining garrison, suffered the loss of several monks, although the monastery itself was left largely undamaged.Footnote 16

What followed was the first significant movement westward of the Sino-Tibetan frontier to occur in centuries. The rebellion also catalysed a new approach to how the Qing thought about and dealt with the Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and monastics in Gansu Province and beyond the mountain passes separating it from Kökenuur (Ch. Qinghai 青海; T. Mtsho sngon), the region surrounding the eponymous Lake Kökenuur.Footnote 17 This article reveals what happened to those Tibetan Buddhist monasteries implicated in the rebellion, changes that led the likes of Sumba Kanbo to wish for the days of old before his own monastery of Gönlung was incorporated into the expanding Qing Empire. While it has long been understood that 1724 marked a significant turning point for the Qing state's relationship with its Inner Asian frontier and, in particular, with what would eventually become Qinghai Province, only recently have scholars begun to consider the repercussions of this event for the powerful religious institutions of this region known as Amdo (T. A mdo).Footnote 18 This article utilises Tibetan-language materials and Chinese-language land deeds from the early eighteenth century to illustrate the drastic increase in imperial oversight and regulation of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Amdo, particularly in the Xining River watershed. More importantly, the policies and practices directed toward these monasteries and monastics were those traditionally employed for Chinese Buddhists of the empire's interior and thus drew Tibetan Buddhist monasteries into a more direct relationship with the Qing. Finally, the Qing's incorporation of Xining monasteries into its system of supervising and regulating the sangha established precedents for how the Qing would engage with monasteries and monastics elsewhere in Amdo in the following decades and centuries.

Imperial Relations with the Tibetan Borderlands in the Ming and early Qing

Unlike the Qing, the Ming Dynasty did not have an expansionist policity regarding Inner Asia. Instead, it developed a system contingent on local circumstances for ensuring stability.Footnote 19 Along its western and southwestern frontiers the Ming developed a system of entitling local leaders who were often referred to as tusi 土司, ‘indigenous chieftans’.Footnote 20 Where the Ming's Shaanxi Province met the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, certain Buddhist lamas were also given titles and seals such as ‘guoshi’ 國師 (State Preceptor) and ‘chanshi’ 禪師 (Meditation Master), which, like the titles and seals awarded the tusi around them, were inherited by their descendants (the nephews, disciples, or sons of the lama). In exchange, these local rulers were expected to maintain order among their own subjects, to muster troops when necessary, and to guard the mountain passes that separated the interior of Ming China from the Inner Asian peoples and polities that lay beyond Ming control.Footnote 21 Most of the lamas thus entitled resided at monasteries that answered to Ming garrisons at Taozhou, Hezhou and Minzhou or at monasteries southeast of the Xining Guard in what is today Minhe County.Footnote 22 There were also a few such lamas northwest of the Xining Guard.Footnote 23 Noticiably absent are lamas from the vicinity of Gönlung. This is because Gönlung and the other Geluk monasteries of Pari were much younger, having been established only in the first half of the seventeenth century.

The region thus protected from raids perpetrated by Mongols, Tibetans or others from beyond the pass is known in Chinese as Hehuang 河湟. It consists of the area between and watersheds of the Yellow, Xining, and Tao Rivers and corresponds to the eastern-most stretches of the geographic-cultural complex known as Amdo.Footnote 24 These guarded mountain passes represented the Shaanxi (and, after 1666, Gansu)Footnote 25 Provincial ‘border with the Fan’, that is, the ‘barbarians’ who were not subject to imperial civilian or military administration. Initially, the Qing inherited from the Ming this system of defending its western frontier and negotiating relations with those people beyond the passes. Kung Ling-wei has described in great detail how the early Qing simply exchanged old Ming titles and seals of lamas from Hehuang with new ones so as to allure these local elite into the nascent state.Footnote 26 Moreover, having just suppressed a major Hui Muslim rebellion in 1650, the Qing realised the ongoing need for local headmen and lamas to maintain the peace and security in the region.Footnote 27

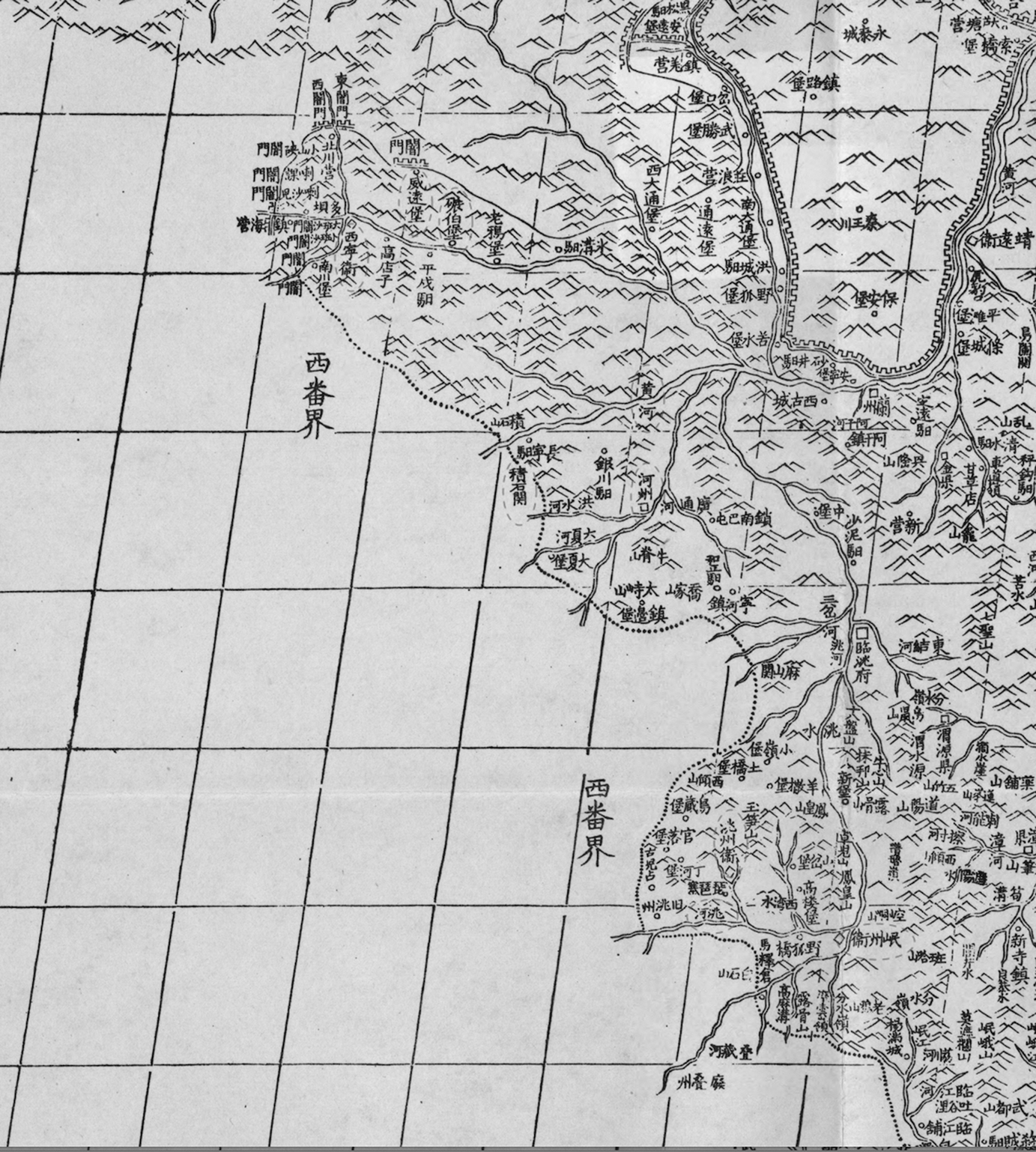

Map 1. Detail of the “Shensi (Kansu)” (Shaanxi/Gansu) map of the 1721 Huangyu quanlan tu 黃輿全覽圖 (the “Kangxi atlas”), showing the major rivers that make up the basin of Hehuang 河湟: the Xining River 西寧河 (also known as the Huangshui 湟水; unlabelled here), the Yellow River 黃河, and the Tao River 洮河. Alongside each of these rivers one finds, respectively (dotted circles have been added around them), Xining Guard 西寧衛, Weiyuan Fort 威遠堡, and Nianbai Fort 碾伯堡; the Jishi Pass 積石関 and Hezhou 河州; and, Taozhou Guard 洮州衛 and Minzhou Guard 岷州衛. As Max OidtmannFootnote 37 has observed, the long, dotted line running from northwest to southeast represents the border of Shaanxi/Gansu Province with the “western barbarians” 西畨界. Gönlung Monastery was located two valleys east of Weiyuan Fort. Chuzang Monastery was located up the valley from (to the north of) Weiyuan. Serkhok Monastery was located one valley west of Weiyuan. Dratsang Monastery was farther up the Xining River, west of Xining. Kumbum Monastery was located southwest of Xining, close to Nanchuan Fort 南川堡. The young Labrang Monastery was located along the Daxia River 大夏河, southwest of Hezhou and beyond the border. Similarly, Rongwo Monastery was beyond the Gansu-Kökenuur border, west of Jishi Pass. Source: Academia Sinica Center for Digital Cultures’ Reading Digital Atlas site, https://ascdc.sinica.edu.tw (accessed July 22, 2019).

Beginning as early as the 1660s, however, the Qing began to shift its attention westward to the domain of the Khoshud Khante.Footnote 28 Significantly, the Khoshud nobility maintained deep ties to much of the region around Xining. Gönlung Monastery, for instance, is said to have received “all of Pari” from the Khoshud ruler, Güüshi Khan, due to that monastery's role in shepherding the rise of the Geluk school and the establishment of the Khoshud Khanate in Kökenuur.Footnote 29 Likewise, later Tibetan sources explain that “up until the Sino-Oirat conflict of the Water-Hare year [1723], the Zünghar kings repeatedly sent envoysFootnote 30 and made donations of tea, cash disbursements, horses, salaries,Footnote 31 and so on” to the monastery.Footnote 32 At the same time, the Ming and the early Qing had maintained a system of forts in the Xining region that collaborated with the indigenous chieftans (tusi) and entitled lamas as described above. In other words, the Xining region was a zone of contested loyalties.

The Qing's recognition of the immense power of the Khoshud, of their strategic position between the interior of the Qing empire and its access to the rest of Inner Asia, and of the unique alliance between the Khoshud and the Dalai Lama's GelukFootnote 33 school, motivated the Qing Court to begin patronising and awarding titles to lamas from regions that were more closely associated with the Khoshud. The Second Changkya Khutugutu (1642–1714), for instance, was the first incarnate lama from Gönlung Monastery, who would eventually become the preceptor to the Kangxi Emperor and play a key diplomatic role in convincing the Khoshud to submit to Qing rule in 1698.Footnote 34 As a reward for his various services to the Qing, in 1705 Lcang skya was made a Meditation Master (chanshi) and then a State Preceptor (guoshi).Footnote 35 A few years later, in 1710, when Changkya Khutugtu left his now permanent residence at the Qing Court to pay a visit to his home monastery of Gönlung, he came laden with riches that he contributed to the construction of a new main assembly hall and other halls at the monastery. His visit also brought imperial patronage for the establishment of a Tantric College at the monastery.Footnote 36 At the same time that the Qing Court was showing favour to Gönlung Monastery, the heir to a monastery farther east in Minzhou was denied his request to inherit his predecessors’ title of State Preceptor. The Kangxi Emperor had decided to terminate the more-or-less automatic renewal of the title of State Preceptor.Footnote 38 Moreover, as Kung Ling-wei has argued, this reflected the Qing's devaluing of monasteries and lamas located farther east, and its pivot to Kökenuur and the domain of the Khoshud Khanate. More broadly, Kung has argued that this reflects the political nature of Qing relations with Tibetan Buddhists as opposed to the Ming's religious approach.Footnote 39

A New Order

The political nature of the Qing's approach to its relationship with Tibetan Buddhism becomes clearest in the aftermath of the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion. Both the rhetoric and the policies of the Qing changed, and attempts were made to incorporate the monasteries of Hehuang, including Xining, into the imperial system of regulating the sangha used in the interior of the empire. This happened concurrently with more strictly ‘political’ changes in this region, such as the creation in 1725 of new civil administrative jurisdictions such as Xining Prefecture 西寧府 and its Xining and Nianbai 碾伯 Counties, the placing of some of the lands of local headmen and lamas onto the tax roles of civil administrators (Ch. gaitu guiliu 改土歸流), and the establishment of a Xining amban's office to administer the now summarily defeated Khoshud.

Previously, Gönlung and other monasteries in the region could confidently rely upon two principal sources for its income: local parishioners and Khoshud patrons. “Formerly, each ‘barbarian clan’ [fan zu] belonged on the surface to the Qinghai Mongols and in actuality to the lamas of each of the monasteries. Annually they gave a grain tax [tianba 添巴]Footnote 40 [to the Mongols] and incense-grain [donations to the monasteries]”.Footnote 41 Now, the military and economic power of the Khoshud was eliminated,Footnote 42 and monasteries in the region had to turn eastward to the Qing Court and to potential patrons in Inner Mongolia for support. Xining was gradually and more fully incorporated into the empire, whereby it ceased being a significant military and political frontier of the Qing.Footnote 43

Numbers of “barbarian” households in the newly created Xining Prefecture were entered on the imperial tax rolls, although older forms of rule persisted, too (e.g. tusi still acted rather autonomously in collecting rents from subjects within their domain), creating a “meshwork of competing juristdictions”.Footnote 44 Annually the government was supposed to collect some 10,542 dan (over one million litres) of grain from these new subjects, although the Yongzheng and Qianlong Emperors both granted them regular and frequent tax breaks due to the harsh environmental constraints on production.Footnote 45 The emperors also encouraged the opening up and development of uncultivated lands in the regions around Xining.Footnote 46 The twentieth-century missionary and ethnologist Louis Schram writes about the immense changes unleashed by the influx of Chinese into the region: “only after 1723 did agriculture begin to develop and the region to flourish. From then on it may be assumed that many Chinese immigrated and settled in the country, engaging in both farming and commerce. …”Footnote 47

Still more changes took place in conjunction with this immigration. Civil service examination centres (gongyuan 貢院) were set up in Xining, Nianbai and other nearby places so as to facilitate the young men who wished to study for the examination but who hitherto had had to travel to Lintao 臨洮 or Liangzhou 凉州.Footnote 48 Schools (fuxue 府學, shexue 社學, and yixue 義學) were established to educate the children of the elite, and a public granary system (shecang 社) was instituted in places such as Xining and Nianbai.Footnote 49 Older Ming forts that had been abandoned were revived, and additional forts were built and garrisoned to maintain the new order. The Sino-Tibetan border had moved irrevocably westward, and with it came imperial policies and practices for administering the sangha more commonly associated with Chinese Buddhism.

Steles and Imperial Recognition

The loss of Gönlung was apparently felt far and wide, for shortly after its destruction, the Paṇchen Lama (1663–1737) sent a letter and numerous gifts to the Yongzheng Emperor. He reportedly wrote, “Gönlung and so forth are the foundation of the Teachings in Amdo, and so it is necessary to rebuild them”. The Seventh Dalai Lama (1708–57) also sent messengers. The young rebirth of the Second Changkya Khtugtu, Changkya III Rölpé Dorje (1717–86),Footnote 50 had been taken hostage by Nian Gengyao and dragged back to the Qing Court. Given the presence of these messengers, the plucky boy was inspired with courage, and he and the other Gönlung lamas who had been residing in Beijing composed a letter to the emperor. Thus in 1729, the emperor sent edicts to Gönlung, whereupon the monastery was reestablished, beginning with just three cloth tents.Footnote 51

A bilingual stele was erected in both Chinese and Tibetan, and in it we read the emperor's command:

… funds are to be sent [for reconstruction], workers are to be assembled, and an official is to be dispatched to direct this task. The structure of the monastery gateFootnote 52 and chapels are to be rectified,Footnote 53 and the monks residences, and assembly halls are to be exactly as before. It is ordered that up to two hundred monks may reside permanently to practice and promote the miraculous dharma. In the future it will also be an abode for the myriad Buddhists. The task [of reestablishing the monastery] is proclaimed accomplished, and because its old name was not elegant, a good name is decreed and established: the plaque that is bestowed [ci'e 賜額] reads “Youning si” 佑寧寺 [lit. Monastery that Protects the Peace]. Also, this record is to be carved in stone so that it may be known in perpetuity.Footnote 54

Although the language of this stele dates from the tenth year of the Yongzheng reign (1732), the monastery name plaque to which it makes reference may have actually been given as late as 1748, when Changkya III made his first trip back to the monastery from his residence in Beijing. “At that time”, Changkya's biographer writes,

the large and small monasteries of DoméFootnote 55 were harassed by bad Chinese rulers and their several inappropriate attendants who sought blame in the monasteries and so forth. [Changkya] therefore thought of immediately bringing benefit to [the monasteries] and thought that it would bring everlasting good to them were they to enter into the ranks of [places that] have received the emperor's gift of his mandate. Once, when he saw the emperor in person, [Changkya] strategically asked about the compassionate protection of an imperially mandated plaque [glegs bu], known as a “tsipen” [T. tsi pen, Ch. zibian 字匾] in Chinese, for Kumbum, Gönlung, and Tsenpo [Serkhok] Monasteries. The emperor was pleased and said, “I have been thinking about that”, and gave the imperial mandate of approval.Footnote 56

The significance of the issuing of an imperial plaque for these monasteries should not be underestimated. This system was fully implemented and institutionalised under the Song Dynasty.Footnote 57 As scholars of Chinese religions know well, the bestowal of plaques was one of the ways in which court authorities attempted to exercise influence over Buddhist clergy and institutions, along with the issuance of ordination certificates (Ch. dudie 度牒), the maintenance of national rosters for monasteries and for clergy and, finally, taxation.Footnote 58 Moreover, in China Proper the bestowal of imperial plaques was a way of converting ‘private’ institutions (Ch. zisun miao 子孙庙) into ‘public’ ones (Ch. shifang conglin 十方叢林) so that they might be ‘civilised’ to serve the social order rather than threaten it. As Song scholar Daniel Stevenson writes,

… from the outset we find an elemental distinction between institutions that were perceived to gravitate respectively toward private/local or state-appointed spheres, the dividing line itself devolving around certain normative—albeit not wholly transparent—notions of how Buddhist institutions should operate in the imperial enterprise and its civil society. The criterion that warranted unconditional acceptance and protection was possession of an imperially bestowed name plaque (chi'e), a token of imperial largesse that even the most virulently anti-Buddhist sovereign was obligated to respect.Footnote 59

Thus, by seeking imperial recognition for Gönlung, Changkya was situating himself and his monastery within a long, Chinese tradition of providing protection to monasteries within the empire. In the aftermath of the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion, Gönlung and the other monasteries implicated in the rebellion were now much more subject to the whims of the local Qing officials in Xining. It was immunity from such a state of affairs that Changkya sought for Gönlung when he asked the Qianlong Emperor for an imperial plaque. In addition, as Stevenson has pointed out for the Song, such imperial recognition appears to have always come at the request of the clergy rather than being the decision of court officials.Footnote 60 We see this, too, with Changya's request.

This system of granting imperial plaques to eligible monasteries and otherwise regulating the sangha had been reinvigorated under the Ming.Footnote 61 Numerous ‘protecting edicts’ (Ch. huchi 護敕) were issued in the Ming to monasteries, including Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Hezhou, Taozhou and Minzhou. For example, an edict of Ming Emperor Xuande (r. 1425-1435) reads:

Today I specially promulgate an edict for protecting and upholding [Min]zhou's Chaoding Monastery 朝定寺. The officials, military personnel and other offices there … [must] comply with this monastery's lama Jindunlingzhan [T. Dge ’dun rin chen] and so forth and the unencumbered religious practice of its monks. They are not to disrespect or mistreat them. No one is to seize or harass its assets, including all its dwellings, mountain lands, gardens, property and livestock. If one does not respect my mandate, disrespects the Three Jewels [of Buddhism], purposefully causes trouble, and disrespects and mistreats so as to terrorize their Teachings [i.e., Buddhism], they are to be convicted according to the law.Footnote 62

As for the Qing, the Timothy Brook suggests,

The Qing was content to repeat the paper regulations for monks and monasteries laid down in the Ming and take no further action. It did not revive the registry system, or impose quotas on monks, or limit monastic property. Considering the internal organizational weakness of Buddhism that the Ming zealously fostered, the Qing did not see a need to police the clergy as closely as Hongwu did. …Footnote 63

Although this laissez faire tendency may have been true for the Qing as a whole, there were periods marked by a concerted effort to document ‘genuine’ members of the Buddhist and Daoist clergies and to weed out any undesirable elements.Footnote 64 This is precisely what happened during the Yongzheng reign and especially the early Qianlong reign, as Vincent Goossaert has shown in his article on the 1736–9 census of clergy.Footnote 65 This census coincided with the increased imperial supervision of the monastic affairs of Xining monasteries in the aftermath of the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion.

To be sure, it is difficult to measure the effect that the placement of these steles and plaques at these Xining monasteries may have had on the operation of and life within the monasteries. Nonetheless, the Qing rhetoric and the precise terminology that it used reveals the new way in which the emperor and officials had begun to conceive of these monasteries as belonging to the same category of institution and potential problem as religious instutions in the interior. Gönlung's neighbour, Serkhok Monastery, was also given a new, ‘proper’ name on an imperial plaque: ‘Guanghui si’ 廣惠寺, literally ‘the monastery promoting benevolence’.Footnote 66 A stele was also erected at Serkhok to remind the monastics of their civic and religious duties. Significantly, the stele refers to Serkhok as “that which Buddhists call a Ten Directions Monastery [shifang yuan 十方院]”.Footnote 67 A “Ten Directions Monastery” (also shifang conglin) is a term found in Chinese Buddhism to refer to “public” monasteries, where monastic leadership theoretically was open to any qualified candidate and where the formation of new tonsure relationships was strictly prohibited.Footnote 68 Abbots at these institutions were to be chosen in consensus with the abbots of other major monasteries in the region and were to be approved by government officials (in some rare cases even the emperor himself).Footnote 69 “The appeal of the ‘public abbacy’”, writes Stevenson,

is not difficult to understand, insofar as it offered a corrective to the privatizing and centripetal tendencies of the “hereditary” cloister, while at the same time extending the reach of the imperial bureaucracy right into the abbot's chamber.Footnote 70

The reference to Serkhok as a “Ten Directions Monastery” and the imperial recognition given to it and other monasteries in the Xining region is also reflective of Qing approval and support of the Geluk school's own norms for administering its large-scale monasteries. Positions of authority within Geluk monasteries were supposed to be free from the taint of favouritism and partiality characteristic of hereditary monasteries. For instance, the 1737 charter for Gönlung Monastery, composed by a major lama from Central Tibet, states: “officers, with the lama as the lead, are not to indulge in favouritism, partisanship or sycophancy and must not bring private interests into a public [position]. This must be well enforced!”Footnote 71 In addition, the abbot was to be elected by a council of senior monks and lamas within the monastery. Again, the charter explains, “as for appointing the abbot, it is to be done based on the consultation of the old abbot, the cantor and disciplinarian, the general manager,Footnote 72 the ‘encampments’ and hermitages,Footnote 73 and the senior monks”.Footnote 74 Moreover, abbots and other monastic officers rotated every few years, not unlike the Qing's own system of rotating officials through its administrative and military posts throughout the empire. The average tenure of an abbot at Gönlung up until the monastery's final destruction in 1958 was four years.

Although the procedure for selecting the abbot at Gönlung that was codified in the monastery's charter does not specify a role for abbots from neighbouring monasteries nor imperial officials, there is evidence that such figures were consulted and may have exercised some influence on the process. A nineteenth-century history of Amdo describes the process of selecting Gungtang III Könchok Tenpé Drönmé (1762–1823),Footnote 75 a major incarnate lama from Labrang Monastery, to serve as Gönlung's abbot (r. 1795-7):

At this point [1795] numerous monks said, “it is important [to have] a lama [i.e., abbot] who truly can restore philosophical instruction and the rules and procedures [of the monastery]. So saying, they went to ask the Xining amban. After everyone consulted, a representative of Tuken Rinpoché, the amban's translator,Footnote 76 the head of the [monastery's] Tantric College, and other such monastic officers went to Labrang Tashi Khyil to present the invitation to the Mañjuśrī Lama Tenpé Drönmé. At this time he said, “due to the times, for one known as the “administrator-protector” [of a monastery, i.e, the abbot], it is difficult [for him] to give rise to a pure religious [practice] free from politics. Once one is connected to worldly things, the foundation of discussion and discourse [i.e. controversy] grows. Because one cannot avoid the circumstances of conflict and so on, it says in the Abhidharmakoṣa: “[Conditioned things] comprise time, the foundations of discourse [etc.]”.Footnote 77 Also, it says in the Actual Stages, “those who have the conception of ‘sentient beings’, their existence is in that conception”.Footnote 78 Because the former discourse has only just passed, there is nothing to rejoice about at this juncture. Since at this moment I am responsible for the throne of Trashi Khyil, and since both places [i.e. Labrang and Gönlung] are places of philosophical instruction, it would be extremely difficult to care for both. Although the power of the amban is great, there are still ways to excuse oneself. [However,] the lama [Tuken's] insistence is great; thus, as there is no custom for refusing or of equivocation, I must accept.Footnote 79

Here we have a clear record from a source close in time and space to the event in question that illustrates the steps taken by Gönlung in appointing a new abbot: some initial conferencing took place among the monks (probably senior monks and officers) at Gönlung. Then they went to the amban in Xining. Next, the amban's translator along with important representatives from Gönlung went to Labrang to make the request. Gungtang wagers that he could in theory decline the request were it coming from the amban alone; however, since the request is also coming from Tuken, Gungthang has no choice but to accept. Apart from this example, it is also clear that the major Gönlung lamas who were stationed in Bejing and who served the Qing court—specifically Tuken and Changkya—were regularly consulted and did attempt to make known their choices for abbot.Footnote 80

In the case of Serkhok Monastery, the term ‘shifang yuan’ does not necessarily imply that Serkhok was actually added to official rolls as a “Ten Directions Monastery”. Nonetheless, the use of the term bespeaks the new attitude that Qing officials had toward Serkhok and other monasteries such as Gönlung as well as the greater level of involvement by Qing officials in what had hitherto been (and what elsewhere on the Tibetan Plateau remained) a prerogative of the monastery and its local patrons: choosing the monastery's abbot. After the Qianlong emperor had agreed to Changkya's request to bestow imperial plaques on Serkhok, Gönlung and Kumbum Monasteries, Qianlong had the plaques sent ahead to the Gansu governor (T. zhun phu, Ch. xunfu 巡撫) in Lanzhou.Footnote 81 Changkya later arrived at Gönlung, and then “on an auspicious day” the governor went to the monastery as ordered, whereupon the plaque was installed above the entrance to the main assembly hall and a precious rosary was offered to the main image in the monastery's shrine hall: “The Lord Lama [Changkya] was seated in the center, and the jarghuchi Footnote 82 sent by the emperor and the governor sat on left and right. I [the author, Tuken III] led lamas in prostrating nine times …before the emperor's gifts in accordance with Chinese customs”.Footnote 83 The presence of the Qing officials at the installment of the imperial plaque as well as the Chinese method of venerating the emperor's giftsFootnote 84 show that these were much more than decorative knick-knacks for the monastery's corridors. Gönlung was henceforth part of an expanding system of regulation that had its origin in China Proper to the east.

The National and Local Systems for Regulating the Sangha

The Ming and Qing imperial systems of monastic officials were subsumed within the Bureau of Sacrifices under the Board of Rites (Li bu Ciji qingli si 禮部祠祭清吏司). At the top of the hierarchy sat the Office for Registering the Sangha (Senglu si 僧錄司), which was made up of eight members. Meanwhile, at the prefectural level were the Chief Controllers (dugang 都綱) and their corresponding Offices for Administering the Sangha (Senggang si 僧綱司). At the sub-prefectural level one finds the Rectifier of the Sangha (sengzheng 僧正) and his Office for Rectifying the Sangha (Sengzheng si 僧正司). And, finally, at District or County level one finds the Convener of the Sangha (senghui 僧會) and his Office for Convening the Sangha (Senghui si 僧會司).Footnote 85 The duties of these local regulators were to supervise the Buddhist monks under their jurisdiction, to propagate the correct Buddhist teachings, to report crimes committed by monks to civil officials, and to conduct public rites.Footnote 86 Timothy Brook, writing about the system in the Ming, says that these and other tasks “indicate that the registrar's function was to administer Buddhism on the state's rather than on Buddhism's behalf and, where the state's presence was weak, to embody public authority”.Footnote 87

It has been said that the system in the Ming became defunct shortly after its implementation largely due to the fact that the individuals who staffed the positions were locals, not disinterested outsiders, and were considered “functionaries” (yuan員) rather than “officials” (guan 官).Footnote 88 The individuals appointed to these positions along the Ming's frontier were certainly locals and not “disinterested outsiders”; however, the system persisted throughout the Ming and was renewed under the Qing.

Initially, the system for regulating the Tibetan Buddhist sangha may have been modelled on the system used for regulating Buddhists and Daoists in China Proper. We read in one source for the year 1389 (Ming Hongwu 22):

In such places as Xi[ning], Tao[zhou], and He[zhou], there are many cases in which an office for regulating the sangha has not been established. A Han monk and Tibetan monk should be dispatched according to the [national] Office for Registering Monks [Senglusi] to manage this. Officials of this Office [for Registering Monks] must select monks who are well-versed in the Buddha-dharma to come take exams, [after which] they are to be appointed and sent.Footnote 89

It is recorded that three years later, in 1392, a local Office for Administering the Sangha was established for Xining, and a certain Sangyé TashiFootnote 90 was made its Chief Controller (although Sangyé Tashi's monastery was actually located approximately 90 kilometres east-southeast of Xining).Footnote 91 Similar titles were awarded to individual lamas in Hezhou, Taozhou, Minzhou and Zhuanglang 莊浪 among other places in Hehuang.

In fact, these ‘offices’ are better understood as institutions or simply as titles affixed to specific lamas and their associated monasteries. Moreover, scholars of the Ming system of regulating monasteries along its frontier with Tibet have noted that it is best understood as a parallel system to the native chieftain (tusi) system, in which local headmen were allowed to continue to rule over the local populations in exchange for their loyalty and periodic tribute to the Ming court. The lamas who received titles from the Ming court—titles such as State Preceptor, Meditation Master, Chief Controller and Administrator of the Sangha (senggang 僧綱Footnote 92)—were similarly charged with ruling over the local populations, mustering troops and defending against Mongol attacks, and making periodic trips to the Ming court to pay tribute. Moreover, their positions were hereditary—Ming records are replete with instances of a nephew (or disciple) of an entitled lama requesting that the title of his recently deceased uncle (or master)Footnote 93 be awarded to him. These are some of the characteristics of the system for regulating Tibetan Buddhist monasteries that set it apart from the system in China Proper.Footnote 94

As discussed above, the Qing inherited this system from the Ming, although it soon made significant changes to it. In 1726, just two years after the Lubsang-Danzin rebellion, the Yongzheng Emperor banned the practice of lamas inheriting their forebears’ titles among other reforms.Footnote 95 His attempt appears to have been unsuccessful, for in 1747 the Qianlong Emperor, citing concern for the laxity that may occur when such positions were inherited and thus expected, banned the practice of inhering the title of State Preceptor, something his grandfather, the Kangxi Emperor, had already sought to do in 1710.Footnote 96 This was part of an ongoing effort by the Qing to replace prestigious religious titles of lamas on the Gansu-Kökenuur border (titles such as State Preceptor) with more political or administrative titles (such as Chief Controller or Administrator of the Sangha).Footnote 97 This also reflects the pattern of the Ming using of religious gifts and titles as part of its system of rule of the frontier versus the Qing's use of political ones.Footnote 98

In the eighth year of the Qianlong reign (1743), responsibility for supervising of affairs pertaining to Tibetan Buddhist monks was moved over to the Court of Colonial Affairs (Lifanyuan 理藩院), a powerful Qing institution created to deal with the Mongols.Footnote 99 Thus, later accounts of the regulation of the Tibetan Buddhist sangha in the Da Qing Huidian (Collected Statutes of the Great Qing), for instance, are found in the section for the Rear Office of the Mongolian Reception Bureau (Rouyuan qingli you hou si 柔遠清吏右後司) of the Court for Colonial Affairs. And it is here that we discover that, in 1747, the Qianlong Emperor vastly expanded the system of regulating the Tibetan Buddhist sangha by establishing (or, in a few cases, reestablishing) titles and imperial offices in 21 monasteries, most of which were farther west in the recently created Xining Prefecture:

Each of the monasteries [and] lamas in Gansu which has received the seals [of] State Preceptor and Meditation Master has since diligently maintained spiritual practice. Under them are all the monks, for whom each [congregation] is appointed an abbot. Nonetheless, their control [of the congregation] is not without laxity. Therefore, positions should be created based on the size of the area and the number of Tibetan Buddhist monks in order to bolster supervision.

In Hezhou, Pugang si 普綱寺, Lingqing si 靈慶寺, and Honghua si 宏化寺Footnote 100 are each to have a Chief Administrator [dugang] installed.

An Administrator of the Sangha [senggang] is to be installed [for each of the following]: Xining County's Xina si 西那寺,Footnote 101 Ta'er si 塔爾寺 [i.e., Kumbum], Zhacang si 扎藏寺,Footnote 102 Yuanjue si 元覺寺,Footnote 103 Shachong si 沙衝寺,Footnote 104 Xianmi si 仙密寺,Footnote 105 and Youning si 佑寜寺 [i.e., Gönlung]; Nianbai County's Qutan si 瞿曇寺,Footnote 106 Hongtong si 宏通寺,Footnote 107 Yangerguan si 羊爾貫寺,Footnote 108 Puhua si 普化寺;Footnote 109 Datong Fort's Guanghua si 廣化寺 [i.e. Serkhok];Footnote 110 Guide Sub-Prefecture's Erdiechan si 二疊闡寺, Chuiba si 垂巴寺, and Mani si 馬尼寺.

In Taozhou, a Rectifier of the Sangha [sengzheng] is to be installed for each [of the following]: Yanjia si 閻家寺; Longyuan si 龍元寺; Yuancheng si 圓成寺. Orders for all of these come through the Court of Colonial Affairs.Footnote 111

What is remarkable about this list is how many of these administrative positions are for monasteries where previously neither the Ming nor the Qing had exercised any kind of imperial oversight. This is true for the monasteries in the vicinity of the old Ming fort at Guide, which had sat dormant or was perhaps even non-existent prior to the time of the Yongzheng Emperor,Footnote 112 and it is also true for all of the monasteries located in Xining County and Datong with the exception of Xina (T. Zi na) Monastery.Footnote 113 Of course, on this list one finds Youning (Gönlung), Xianmi (Semnyi), Zhacang (Dratsang), Guanghua (Serkhok) Monasteries and Ta'er (Kumbum), which were all implicated in the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion and suffered the consequences. The other related reason that these monasteries had attracted the attention of the Qing is that they were all relatively new monasteries closely associated with the Dalai Lama's ascendant Geluk School and with the Khoshud nobility.

Even though the names of some of these positions were the same as those employed during the Ming and early Qing (e.g. dugang, senggang), there is a qualitative difference between them. As described above, the earlier “Chief Controllers”, “Administrators of the Sangha”, and so forth were titles granted to the lamas of hereditary temples who oversaw land and subjects and paid deference to the Ming and earlier Qing Courts by making periodic trips to Beijing to deliver tribute. These later administrative positions from the post-Lubsang-Danzin period were explicitly non-hereditary, and there is no evidence they ever had the duty (or privilege) of presenting tribute to the Court.Footnote 114 Moreover, this was not a case of awarding a title to some high-ranking lama whose authority was already a reality on the ground. Rather, these were imperial bureaucratic positions. This may explain why it is that there is almost no trace of these newly created positions in the historical record following their creation. As Goossaert writes regarding the system for regulating the sangha in China Proper,

Clerics chosen for such offices were symbolically assimilated to the civilian bureaucracy, but normally were not paid for this office. They were responsible for any violation of the law committed by the clerics within their jurisdiction, but had little leverage, especially under the Qing. This may be the reason why one actually rarely finds them mentioned in official documents. It is possible that the Senglu si and Daolu si [道錄司] kept extensive information about the clerics and the various institutions that housed them, but they did not publish documents, nor is there any evidence of their archives …Footnote 115

As their names suggest, the Senglu si and Daolu si were the national offices for registering Buddhists and Daoists, respectively. In the Qing they were theoretically in charge of all the temples, monks, and Daoists in China. They were responsible for ensuring that the monks and Daoists all understood the meaning of their respective scriptures and that they all observed ‘pure codes’. If such a monk or Daoist could pass muster, then each would be given a registration certificate (Ch. dudie度牒). These certificates were ultimately to be handed down to the local Offices for Administering the Sangha (or, for Daoists, the Offices for Overseeing Daoists, Daoji si 道紀司) for distribution.Footnote 116

The extent to which such ordination certificates were issued among Tibetan Buddhist monasteries is unclear, although the Qing certainly intended at times to implement the dudie system among Tibetan Buddhist monastics as it did among monks and priests in China Proper. The Xining fu xin zhi 西寧府新志 of 1746 (The New Gazetteer of Xining Prefecture) records,

the emperor decreed in the inaugural year of the Qianlong era [1736]: “Buddhist monks, Daoist priests, and lamas [should be] issued ordination certificates [dudie]. These monks and Daoist priests must maintain the Pure Codes [qinggui 清規], and they are only permitted to recruit one disciple”. This is at present obeyed. All official guardians of the territory [must] capably and sincerely undertake this task. They themselves [must] audit [the process], and they [must] not delegate it to a petty official or servant. They [must] not look upon this as ordinary [business]. [This] is the death of the [over-]proliferation of the two religions [ershi 二氏], and they can gradually be eliminated.Footnote 117

Writing about Mongol Buddhists, Charleux says that only a fraction ever received an ordination certificate despite the Qing's rather generous approach to issuing them there.Footnote 118 Western and Chinese scholars have both reported on ordination certificates issued to Tibetan Buddhist monks in Hezhou.Footnote 119 In addition, the Xining fu xin zhi records that the monks of the major Amdo monasteries of Jakyung (above, “Shachong”)Footnote 120 and Trotsang Tashi LhünpoFootnote 121 received registration certificates and vestments in 1738 in exchange for allowing the construction of a road to cross their territory. This road is said to have served the purpose of more efficient tax collection.Footnote 122

The Qinghai Tuzu shehui lishi diaocha (Research on the Social History of Qinghai Monguors) reports that Gönlung indeed had two senggang (written 僧岗) when researchers visited there in the 1950s,Footnote 123 and Kumbum Monastery, too, is said to have retained a ‘Sangha Official’ through the twentieth century.Footnote 124 At Gönlung they were incorporated into the monastery's hierarchy after the abbot's stewardFootnote 125 and the monastery's two disciplinarians (sengguan 僧官; Ch. dge skos). These two senggang are said to have been responsible for spending the donations that the monastery received and for taking care of all of the monastery's external relations. If ‘external relations’ means official relations with the state, then it would seem that this position created in the immediate aftermath of the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion persisted well into the twentieth century, with the local twist being the creation of an additional senggang above and beyond the one stipulated in the 1747 decree.Footnote 126

Gönlung Monastery's Land-holdings, Before and After

Qing officials, such as the Department Magistrate of Hezhou Wang Quanchen 王全臣, in his Hezhou zhi 河州志 (Gazetteer of Hezhou) of 1707, railed against the landholdings of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (as well as the tusi), and sought to render “fiscally legible populations”.Footnote 127 Wang decried the monasteries as a “scourge that damage the country and harm the people”.Footnote 128 Likewise, shortly after suppressing the Lubsang-Danzin rebellion, Nian Gengyao memorialised the throne, making 13 administrative recommendations for the newly conquered territory. Among them, he wrote,

regarding the lama temples of Qinghai, they ought to be routinely inspected. Investigating the lamas of each of the temples in Xining, each has as many as 2,000–3,000 and as few as 500–600. [The temples] have become places that accept and conceal evil. The Tibetan subjects pay the lamas taxes no different than offering tribute. … As for the Tibetan people's grain, it should all be given to the local [Qing] officials to manage. …Footnote 129

After the ‘impudent’ actions of many monasteries during the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion, proposals were made to ‘cut off the arms’ and ‘clip the wings’ of the monks and Mongol ‘barbarians’ in Amdo by completely remaking the political, social, and religious landscape of the region.Footnote 130 For instance, we read that in 1725 the following memorial was approved:

… It must be ordered that the tenants of each of the monasteries and clans [zu] reunite with China Proper [neidi 内地] and become [its] subjects. All imperial seals that have been given must be fully collected. [They] are not to be given orders to govern the barbarian settlements [fanluo 番落]. …Footnote 131

At the same time, a limited system for the financial support of these monasteries was put into effect. As Sumba Kanbo—the same figure who waxed poetic about the golden age of Buddhist patrons before the Qing's presence in Amdo—tells it,

The Second Paṇchen Lama sent a messenger, and the Changkya Emanation was in agreement [with him], making earnest requests on behalf of the monasteries and practice centres [of Amdo]. Thereupon, the Great Dharma King Yongzheng Emperor was pleased, and in the Earth-Bird year [1729] he repaired the monasteries and practice centres with [funds from the imperial] treasury. The taxpayers of the ‘divine communities’ [lha sde; i.e., subject communities]Footnote 132 were subsumed [by the Qing administration]. However, in their place the beneficent custom of conferring without interruption permanent allowances from the [imperial] treasury was well established. From that point forward, at those monasteries and practice centres, philosophical teachings flourished and the Victor's Teachings grew like a [summer] lake. Good discipline was established everywhere through Tsongön [Kökenuur], Amdo, and Kham.Footnote 133 [Thus] was there the marvellous spread of glorious happiness.Footnote 134

We even have some idea how much these imperial allowances were supposed to be. Archival records for the year 1761 specify that Xining County (where Gönlung was located) provided 1.6 ‘bushels’ (dan 石, hectolitres) of grain for each of 2,245 monks. The adjacent Nianbai County provided 1.07 bushels for each of 736 monks. Datong County 大通縣, where Serkhok was located, provided 2.75 bushels for each of 1,323 monks. Other subprefectures within Xining Prefecture also received specified allotments of grain.Footnote 135 These grains were to come from the very lands that the Qing administration had confiscated and now had on its tax roles.Footnote 136

It is impossible to ascertain the extent to which this system was implemented. Such allowances were no doubt inconsistent and insufficient for covering the needs of the monasteries and their monks. Thus, monasteries like Gönlung continued to make claims over lands and subjectsFootnote 137 and continued establishing priest-patron relatinoships with Mongol rulers and their communities in places such as Inner Mongolia.Footnote 138 Nonetheless, there were very real social and economic changes that began to take off in the years and decades following the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion. In describings the simultaneous effort by Qing officials in Hehuang to reduce the power and influence of tusi there—an incomplete but persistent effort—Wes Chaney writes, “just fifteen years before [i.e., before the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion], the [Xining River watershed] village would have had no connections to a county office; now runners, sub-bureaucratic tax agents, and officials entered the community”.Footnote 139

The same Qing officials who sought to register tusi landholdings and to collect additional taxes from them tried to do the same to the monasteries. The first Xining amban together with the regional commander memorialised in 1727, stating that the “barbarian clans originally administered” by the ennobled lamas of the region “are to return to the administration of the prefectures and counties. Originally [the lamas] collected incense and grain. [This land] is to return to the state and pay official taxes”.Footnote 140 At the same time, new duties were imposed by imperial authorities on monasteries such as Gönlung, which many monks begrudged. Sumba Kanbo, who served as abbot on three occasions during Gönlung's period of rebuilding, writes of his own efforts at meeting these obligations while abbot:

Every time it is required to do construction labour for the monastery,Footnote 141 to pay taxes to the [emperor's] officials [rgyal dpon], and to fawn on [high-ranking] travellers, [there are some small-minded monks] who are attached to material things and cannot bear to spend them. Regarding the common wealth as for the general manager alone, and not trying to find ways to delay one's own [responsibilities], my estate took principle responsibility [in paying and providing].Footnote 142

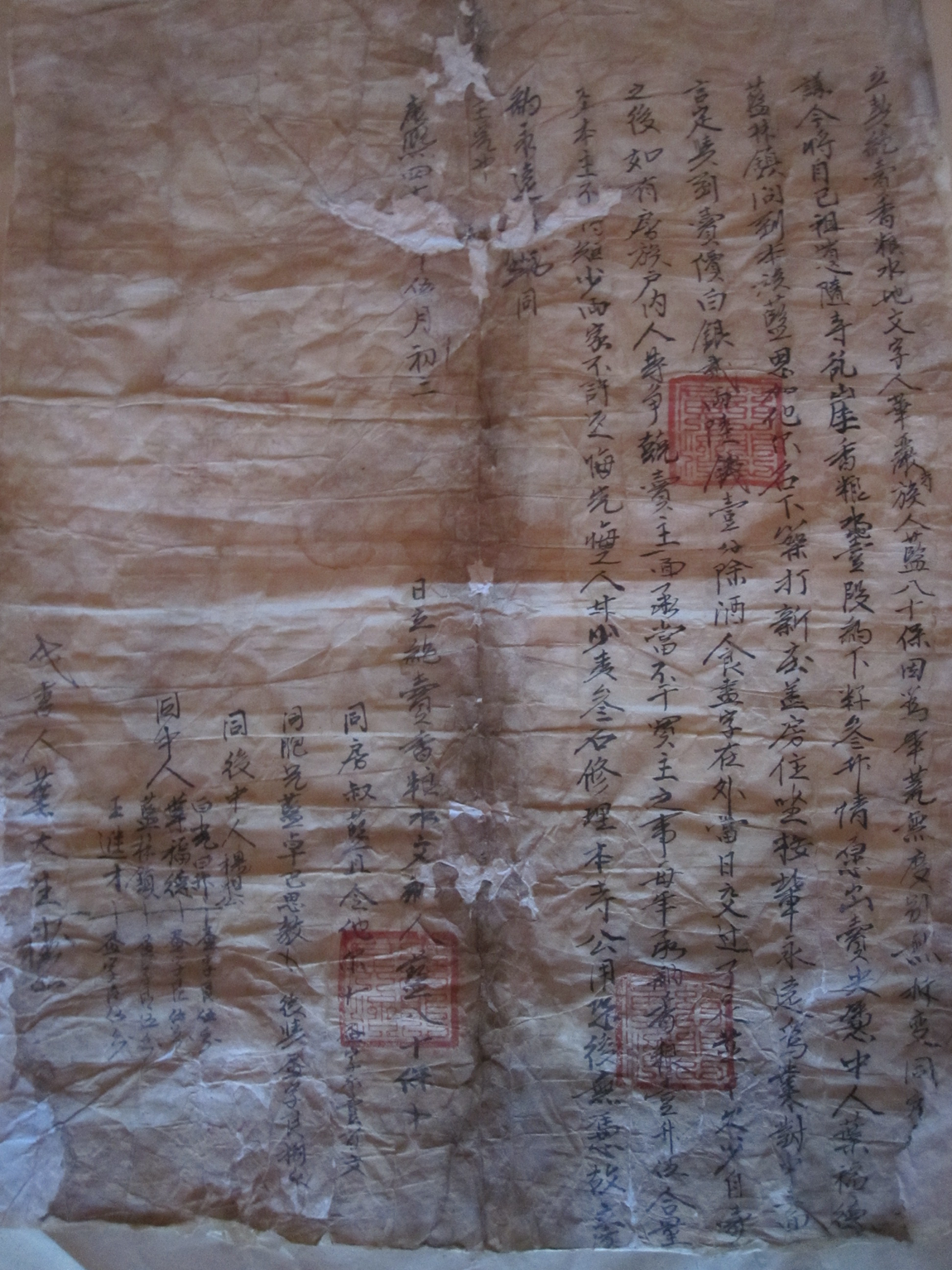

Rare land deeds dating from before and after the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion help to illustrate the changes in landownership and taxes that the monasteries had to confront. One land deed dating from the first decade of the eighteenth centuryFootnote 143 pertains to an “irrigated incense-grain” field, that is, land dedicated to supplying a monastery material support in the shape of incense, grain, and so forth.Footnote 144 In this case, the incense-grain land was required to annually pay a tax in kind to the monastery known as Huayan Monastery 華嚴寺, or Chözang Monastery, a subsidiary temple of Gönlung's, located just one valley to the east of Gönlung. The seller, probably a Monguor,Footnote 145 appears to have belonged to the estate of Chözang Monastery, since the contract refers to him as being a subject of the monastery's “feud” (zuren 族人). The contract reads that after the transaction is completed, "… each year one sheng 升five ge 合 of incense-grain [tribute] is to be collected [by the monastery]”, and that “the original owner shall not be concerned with any [future] shortage”. The transaction amount was two liang 兩 six qian 錢 and one fen 分 of silver. Another clause appears to say that whichever side first ‘regrets’ and reneges on the contract would be required to pay a fine of three ‘bushels’ (dan 石) of wheat and undertake repair of the monastery's roads (gongyong lu 公用路).Footnote 146

By contrast, a later set of land deeds tells a very different story. Significantly, these three deeds all date from the decades following the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion—specifically, the years 1739, 1742 and 1791.Footnote 147 In addition, all of them deal with parcels of non-irrigated land being sold to a monastic community, which illustrates how the monastery was (re-)growing its assets and doing so in a market economy. The monastery in question is Tratsang Monastery (above, Zhacang si), another subsidiary temple of Gönlung.Footnote 148 The deeds all describe the size of the land in terms of the amount of seed needed to sow the fields, and this is given in the local “market litres” (shisheng nei 市升內) unit of measurement. Similarly, the deeds give the amount of the transaction in terms of the “market value” (shijia 市價) of a specified amount of silver. In addition, the buyer henceforth was to become solely responsible for paying an annual tax in kind to the government's public granary (naguan liangcang 納官糧倉), the amount to be paid specified in terms of official “granary litres” (cangsheng 倉升).Footnote 149

Fig. 1. Contract of land sold from a subject of Huayan Monastery (also known as Huayuan si 花園寺; T. Chos bzang ri khrod bde chen chos gling) to another individual in the year Kangxi Forty-[something]. See note 143.

Fig. 2. Image of 1739 contract of land sold to the monastic community of Zhacang Monastery (T. Grwa tshang dgon). Image compiled by the National Qing History Project 国家清史编纂工程 in Beijing. See note 147, document number 463001-5-89-3-4

To be sure, these four deeds compose a small sample size, and it is possible that the differences between the earlier deed and the later deeds can be explained by the fact that they are dealing with different places, although both are within the Xining River watershed and both are Gönlung's branch monasteries.Footnote 150 Nevertheless, the differences between them are so striking that they do suggest that changes in time have played a role. In particular, the earlier deed clearly indicates that the parcel of land is near and somehow in the service of Chözang Monastery, requiring an annual ‘incense-grain’ contribution be made to the monastery. The latter deeds refer to land for which the new owner, Tratsang Monastery, is required to pay an annual tax to the government. It is also interesting that the official units of measurement are explicitly employed in all of the latter deeds but not in the earliest deed. This is no doubt because of the gradual integration of Gansu Province (including Xining Prefecture) markets into the empire that took place during the Qianlong reign.Footnote 151 In the post-Lubsang-Danzin period, monasteries of the Xining region were at least partially divested of their estates and thereafter operated within a social and economic framework that included Qing officialdom rather than one maintained by the monasteries and local rulers alone.

But just how much of these monasteries’ tax base was taken following the rebellion? Unless archival documents surface and become available to the public, it will be difficult to determine specific numbers. Güüshi Khan is said to have granted Gönlung “all the land in Pari” (T. Dpa’ ris)—an immense swath of land that encompasses present-day Datong, Huzhu and Ledu Counties, as well as Menyuan County and adjacent counties across the provincial border with Gansu. By the 1940s, however, Gönlung is said to have possessed no more than 3 per cent of the cultivated land in Huzhu County where the monastery is located.

Were Gönlung's estates actually confiscated, and if so, what did that mean for the economic situation at Gönlung? A key source for evaluating the economic status of Gönlung and other monasteries prior to the major reforms introduced by the Communist Party is the Qinghai Tuzu shehui lishi diaocha (Research on the Social History of Qinghai Monguors).Footnote 152 As the preface to the series explains, its findings were the result of research conducted in the 1950s and 1960s, although it was not written until after the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 153 Its accuracy in terms of local history prior to the twentieth century is suspect.Footnote 154 Nonetheless, this Qinghai Tuzu shehui lishi diaocha may be more reliable for the years closer to its composition. According to this source, Gönlung had 37,000 mu 畝 in what is now Huzhu County,Footnote 155 and it may have owned another 50 per cent more in surrounding counties.Footnote 156 Gönlung's landholdings in Huzhu are broken down as follows:

Tenants on the land of the monastery's monks (10,000 mu) were required to pay a substantial portion of their yields as rent. For instance, for a parcel of land sown with one “bushel” (dan 石) of seed (approx. 100 litres)Footnote 161—such land amounting to approximately 40 mu or 2.67 hectares, we are told—the tenant was required to pay five dou 斗, or 50 litres of grain as rent.Footnote 162 Given the frequent occurrence of natural disasters in the region, this no doubt amounted to a considerable burden for tenants. The monks who owned the land would have collected 1,250 dou, or 12,500 litres of grain upon each annual harvest, which is no small allowance.Footnote 163

That being said, it is important to note that what is now Huzhu County had some 1.16 million mu of cultivated land in the years leading up to the Communist takeover there.Footnote 164 That means that Gönlung, its lamas, and their subsidiary temples possessed no more than 3.2 per cent of the cultivated land in Huzhu.Footnote 165 Since there were only 290 monks at Gönlung at that time and perhaps another 250 monksFootnote 166 at its subsidiary temples, this means that monks made up less than 0.5 per cent of Huzhu's population of over 112,000 people.Footnote 167 Thus, while it does appear that the communist authors of our Qinghai Tuzu shehui lishi diaocha have some basis for their assertion that monks were better off than the “toiling masses”, nonetheless ownership of a mere 3 per cent of cultivated land pales in comparison with the dominion exercised by some medieval Christian monasteries and abbeys,Footnote 168 not to mention outright lordship over “all of Pari” with which Gönlung was allegedly endowed in the seventeenth century by Güüshi Khan.

In conclusion, it is clear that Gönlung was not deprived of all of its estates. Gönlung's major monastic charter, composed 13 years after Gönlung's destruction by Qing forces, specifies and demarcates Gönlung's pastures and rights to the trees and grass there.Footnote 169 In addition, it and other monastic charters from the period specify which local laity are required to finance the Great Prayer festival and other major ritual occasions of the monasteries. Likewise, we still see references to ‘divine communities’ (lha sde) belonging to these monasteries in the later sources.Footnote 170

At the same time, it is an oversimplification to say that the rules and restrictions set forth by the Qing authorities “were not implemented”.Footnote 171 As we have seen, Gönlung's landholdings in the early twentieth century appear to have been a mere fraction of its original endowment, and Gönlung, like its subsidiary temples, was burdened with new obligations like paying taxes and providing corvée for government officials (“high-ranking travellers,” which likely included Qing officials as well as Buddhist lamas). As Chaney has observed regarding the collection of taxes from lands and people that previously had not been on imperial rolls but on those of tusi: “the actual rates [of tax collection] were less important than the overall fact that this land began to be registered by civilian officials”.Footnote 172 Moreover, there was a clear shift from the Ming's exclusive focus on military defence vis-à-vis entitling local rulers and lamas to a much closer and more direct relationship between imperial authorities and Amdo monasteries that commenced in the Xining region.

Conclusion: Precedents and Persistence

How should we conceptualise the incorporation of the monasteries of the Xining River watershed into the Qing, and what are its implications for the rest of Kökenuur? It is clear that policy is not practice and that many of the imperial recommendations and policies for these monasteries were ignored or insufficiently implemented. For instance, among his list of 13 recommendations for restructuring the region following the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion, Nian Gengyao advised that monasteries be permitted “no more than two hundred dwellings and three hundred lamas”.Footnote 173 A similar number (200 monks) was given by the Yongzheng Emperor in the stele that he had prepared for Gönlung Monastery. However, Gönlung may have had a population of 2,000 in the late eighteenth century or even as many as 3,000 in the nineteenth century.Footnote 174 Likewise, to include Gönlung or other Amdo monasteries in the same category as the more directly controlled “imperial monasteries” of Inner Mongolia is misleading, although some have done so.Footnote 175 Records of the Court of Colonial Affairs (the Lifan yuan zeli) do not stipulate the types and numbers of monastic officials that are to staff monasteries in Amdo as these records do for “imperial monasteries”.Footnote 176 Nor do these records specify the amount of an allowance that is to be paid to such monasteries or set quotas for the types and numbers of monks allowed to reside there. As we have seen, most of these things are indeed mentioned elsewhere (e.g. the Yongzheng Emperor's issuing of the plaque for Gönlung; archival records indicating grain allowances for the monastics of the region), and Gönlung, for instance, was certainly on the radar of the Court of Colonial Affairs.Footnote 177 However, Gönlung's acquisition of these traits corresponding to an “imperial monastery” was a more piecemeal process, and its interactions with Qing officialdom seem to have been limited to authorities in Xining and Gansu and to its lamas in Beijing (such as Changkya).

Even if we cannot speak of Amdo monasteries as “imperial monasteries” nor of the complete and consistent application of imperial regulatory policies at monasteries in Amdo, nonetheless the reality is that the eighteenth century forever altered the place of these monasteries within the empire. It radically reoriented these monasteries’ attention away from its focus on Central Tibet and on its Kökenuur-based Khoshud patrons by effectively eliminating the latter. Monks from these monasteries were forced to look eastward to Inner Mongolia for potential patronsFootnote 178 and—as more and more high-level lamas were forced to reside in Beijing (the development of the so-called “Peking Lama” system is the full maturation of this process)—toward the Qing Court.

In the aftermath of the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion, the Qing emperors and officials drew on a repertoire of bureaucratic procedures more commonly associated with regulating the Chinese Buddhist sangha and applied those to the powerful monastic institutions of Xining and, in particular, Pari. These reforms represent the commencment of what Max Oidtmann has described as a broader, “gradual shift from a multi-centric legal order to a state-centered legal regime” in Amdo.Footnote 179 In various recent publications, Oidtmann has presented evidence from the hitherto unseen archives of the Xunhua Subprefect to demonstrate the process by which Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in AmdoFootnote 180 came to be enmeshed in and even thrive through the Qing legal and administrative apparatus in Gansu and Kökenuur. The cases he has reconstructed reveal how the Xunhua subprefect, the Xining prefect, and even the Xining amban and Shaanxi-Gansu governor-general were dragged into legal battles between Tibetan and Mongol contestants. These Qing courts became the sites of ‘legal politicking’, as lamas, monks, local rulers and ordinary subjects presented their claims vis-à-vis other contestants.

One of the earliest such cases surfaced in the 1770s and lasted for nearly two decades. In it, Labrang Monastery claimed the right to appoint the abbot of Tsö Monastery (T. Gtso dgon dga’ ldan chos gling) and thus to be the “mother” or “root” monastery of Tsö. The protracted legal battle resulted in several appeals and overturned decisions. Labrang ultimately lost in the later rulings and failed to assert its legitimate authority over Tsö. Nonetheless, Oidmtann has concluded, “if Labrang seems to have learned anything from this matter, it was that persistence might pay off, as would the strategic use of the entire scope of the Qing administrative system”.Footnote 181 Indeed, Oidtmann has even suggested that the massive estates of such monasteries as Labrang and Rongwo (T. Rong bo) and the major lamas connected with them came about not in spite of but because of their learning to effectively utilise the Qing officials of Gansu and Kökenuur.Footnote 182

Oidtmann calls the Labrang-Tsö lawsuit “unprecedented in Qing legal history” and describes how it had profound impacts on the subsequent jurisdiction of the Xunhua subprefect and the Qing administration of Amdo more generally. In short, the case had compelled leading Qing officials of Gansu and Kökenuur to propose that the Xining amban be given direct supervision of the Tibetans of Xunhua and neighbouring Guide Subprefectures alongside his supervision of the Khoshud of Kökenuur. The problem, as these officials saw it, was maintaining the separation of Tibetans and ‘Mongols’ (Ch. Meng 蒙) in Kökenuur. It was hoped that this administrative reform would make enforcement of this policy of separation more efficient and effective.Footnote 183 Of significance for our purposes is that the advocates of this reform explicitly drew on the proposals and reforms previously made by Nian Gengyao (as well as his onetime comrade in arms, Yue Zhongqi 岳鍾琪, 1686–1754).Footnote 184

Later suits would also echo the reforms introduced in Xining by Nian. For instance, Oidtmann has also reconstructed a case from 1875 involving Khagya (T. Kha gya) and Rong'ar Monasteries (T. Rong ngar mi ’gyur gsang sngags gling) over the ownership of certain estates. The plantiff in the case, the lama of Khagya, had complained to Qing officials that Rong'ar had confiscated three of its estates and that Rong'ar had been relentlessly attacking and killing people associated with Khagya. The Qing officials involved initially ruled in favor of Khagya, and, in addition, the governor-general awarded Khagya a plaque (bian'e 匾額) “further marking the [Khagya Monastery] communities’ privileged relation with the Qing”.Footnote 185 Later, when that plaque was partially burned in another Rong'ar raid, this was perceived as a “personal affront to the governor-general that officials could not and did not ignore”.Footnote 186

Qing forces ultimately responded with great force, executing leaders associated with Rong'ar. Part of the settlement entailed creating an entirely new administrative position, that of “general administrator” (Ch. zongguan 總管)Footnote 187 of Rong'ar, Khagya, and Terling (T. Gter lung) Monasteries, awarded to respected lama from a nearby monastery.Footnote 188 This appointment, moreover, was not merely the recognition of some status quo (i.e., it was not the entitlement of a local lama who already exercised authority over these three monasteries) but rather represented direct intervention into monastic affairs.Footnote 189 Thus, rhetoric and policies first articulated in the immediate aftermath of the Lubsang-Danzin Rebllion persisted and inspired later policies on the Qing Gansu-Kökenuur frontier,Footnote 190 and imperial practices introduced at Gönlung and other monasteries, such as the appointment of new administrative positions and the awarding of imperial plaques, continued to be carried out as the Qing frontier reached farther out onto the Tibetan Plateau.

Of course, this is not a case of the progressive incorporation of Amdo into Qing civil administration. Indeed, as Oidtmann has written of the administrative changes following the Labrang-Tsö lawsuit, if anything, those changes represented a reversal of such a process.Footnote 191 R. Kent Guy, too, has remarked on the fact that Gansu Province (together with Sichuan) is rather unique in exhibiting a trajectory away from civilian administration in the service of greater militarisation of the Qing frontier.Footnote 192 Instead, what resulted along the Gansu-Kökenuur frontier is what Oidtmann has referred to as a “pluralistic legal order” and Wes Chaney as “overlapping jurisdictions and multiple tax and landholding regimes”.Footnote 193 The 1737 monastic charter of Gönlung recognises this complex arrangement: while most infractions of monastic rules and norms are dealt with internally by the monastery's disciplinarians, “cases of capital punishment certainly are to be handed over to the Chinese and Oirat [sog po] judges [khrims bdag]”.Footnote 194 Schram appears to have taken great delight in reporting on the “plural legal culture” and “overlapping jurisdictions” of the people in the Xining River watershed, particularly when it came to cases involving lamas at the courts of Qing officials. While monasteries maintained their own courts and prisons, as did the indigenous chieftans (tusi)Footnote 195 decisions could be appealed or brought directly before Qing officials. These officials, according to Schram, took delight in providing the final word,Footnote 196 but not before enriching themselves by depleting the litigants of everything they owned:

Ch’ü-t'an [Qutan] sued the branch to vindicate its rights of proprietor of all the domains of Ch’ütan. The lawsuit was carried to the Court of Justice of the Subprefecture of Nienpei [Nianbai] and lasted for two years. The Chinese officials, lavishly bribed by both groups, finally sent the lawsuit to the Court of the Prefecture of Hsining [Xining] in order that their friends and superiors might have the opportunity to acquire some wealth and promote the cause of justice. Again, the lamas stubbornly spent their money for two years. Still unwilling to accept the verdict of the judges, the suit was sent to the Supreme Court of the capital of the province. Here the Chinese officials were very happy to meet the interested customers, and the gullible lamas started immediately to sow again, seeds of wealth and happiness in the gardens of the highest officials. For sixteen years the clever officials kept the wheels turning, encouraging both groups, exciting passions and stubbornness, promising to both sides a successful conclusion. The gullible lamas spent money, and the officials milked the meek cows dry. Finally, the wealth of the mother lamasery was exhausted first, so that the branch lamasery won the suit. …Footnote 197

Qing rule in Amdo was not a singular trajectory from loose, imperial rule to proto-nation-state, and Chaney had persuasively warned against flattening “the cragged local topographies” of individual lives and of specific times and places.Footnote 198 Qing rule in Amdo often consisted more of ad hoc responses on the ground to particular cases than to some grand and consistent strategy for incorporating the borderlands into the empire.Footnote 199 However, the religious policies and practices directed toward the lamas and monasteries of the Xining region in the immediate aftermath of the Lubsang-Rebellion represented a monumental shift in how the Qing conceived of and treated Tibetan Buddhist lamas and monasteries in Amdo, a shift from which the Qing would not retreat. These imperial policies and practices included the creation of new administrative positions that had real, lasting impact; the ‘benevolent’ awarding of plaques to these monasteries in exchange for their loyalty and the choosing of new names for those monasteries that demanded such loyalty; the insertion of itself into the appointment of abbots and into other monastic affairs; the confiscation of lands and subjects of monasteries and the registration of those on the imperial tax rolls; and the drawing of local antagonists into Qing legal courts to settle their disputes.

These policies and practices were tested first and most comprehensively on the lamas and monasteries of the Xining region and Pari in particular, a fact that helps to explain the different historical trajectory of the monasteries there and that of monasteries in the rest of Amdo. The monasteries of Xining and Pari are located much closer to the prefectural seat and to the major economic corridor between the Tibetan Plateau, Mongolia, and China than are regions to the south of Xining beyond the mountain passes. In addition, the monasteries of Xining were devasted during the Lubsang-Danzin Rebellion due to their ties with Khoshud nobility, and these monasteries were rebuilt entirely under the auspices of the Qing. The “Three Great Monasteries of the North [of Amdo]”, namely Kumbum, Serkhok, and Gönlung, never regained the status, fame, or influence that they had demanded in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.Footnote 200 The “southern monasteries” (south of the Xining River), such as Rongwo and Labrang, meanwhile, were not affected by such factors and were therefore in advantegous positions that allowed them to more gradually adapt to and even profit from the introduction of Qing reforms.Footnote 201