Ruḍaw in Islamic-period sources

Ibn Isḥāq (d. 767)—the famed collector of lore about the prophet Mohammad, the nascent Muslim community, and pre-Islam—remarked on the existence of a pagan cult site called ruḍāʾ.Footnote 1

وكانت رضاء بيتا لبني ربيعة بن كعب بن سعد بن زيد مناة بن تميم، ولها يقول المستوغر بن ربيعة بن كعب بن سعد حين هدمها في الإسلام

ولقد شددت على رضاء شدّة * فتركتها قفْرا بقاع أسْحما

Ruḍāʾ was a temple belonging to Rabīʿah son of Kaʿb son of Saʿd son of Zayd-Manāt son of Tamīm and Al-Mustawġir son of Kaʿb son of Saʿd said concerning it when he destroyed it in the time of Islam:

‘I launched a mighty attack upon Ruḍāʾ and left it in ruin, charred black’

Ibn Hišām (d. 833) offers further details on the character of Ruḍāʾ's destroyer.Footnote 2

ويقال : إن المستوغر هذا عاش ثلاثمائة سنة وثلاثين سنة، وكان أطول مضر كلها عمرا، وهو الذي يقول

ولقد سئمت من الحياة وطولها * وعمرت من عدد السنين مئينا

مائة حدتها بعدها مائتان لي * وازددت من عدد الشهور سنينا

هل ما بقي إلا كما قد فاتنا * يوم يمر وليلة تحدونا

And it is said that this al-Mustawġir lived for three-hundred and thirty years and was the longest lived of all of Muḍar; he is the one who said:Footnote 3 ‘I have grown tired of life, spanning centuries. I saw two-hundred years, then one hundred more; and the months keep turning to years; but is there anything coming that hasn't already passed? Day goes by, always followed by night’

Ibn Al-Kalbī (d. 819) briefly mentions ruḍāʾ in his famous Kitāb al-ʾAṣnām ‘the Book of Idols’. His report is virtually identical to Ibn Isḥāq's account but expresses some uncertainty as to the exact identity of the figure. He notices that the name ruḍà رضى , this time given with an alif-maqṣūrah in the edition, occurs in theophoric names.

وقد كانت العرب تسمى بأسماء يعبدونها. لا أدري أعبدوها للأصنام أم لا؟ منها:

" عبد ياليل "و"عبد غنم " و"عبد كلال " و "عبد رضى "

And the Arabs were called after the names (of those) they worshipped; I do not know whether what they worshipped were (names) of idols or not; among them are:ʿabdu-yālīl and ʿabdu-ġanm and ʿabdu-kulāl and ʿabdu-ruḍà Footnote 4

The particular spelling ibn al-Kalbī gives in the edition, if it reflects the original manuscript and not an editorial choice, is in fact faithful to the most common pre-Islamic form of the divine name, as we shall see. While the form ruḍāʾ occurs in the quoted line of poetry attributed to al-Mustawġir, it is clearly metri causa, perhaps motivated by a merger of the alif-maqṣūrah /à/ and the alif-mamdūdah /āʾ/ in later forms of Arabic.Footnote 5

From the Islamic-period accounts, it is clear that a faint memory of ruḍà as an object of pagan reverence persisted but not much more. The survival of the name ʿabdu-ruḍà — if only as a component of genealogies—would have been enough to signal that ruḍà was the name of god, even if his worship had long ago ceased. Thus the line of poetry attributed to al-Mustawġir need not—and likely does not, considering his mythological nature—reflect a memory of an historical event but simply the use of the smashing idols topos to narrativise the passage from pre-Islam to Islam.Footnote 6

Ruḍaw in pre-Islamic sources and his place of origin

The pre-Islamic inscriptions justify ibn al-Kalbī's reservations regarding the interpretation of divine name as a bayt; Ruḍà was in fact one of the most widely worshipped deities in pre-Islamic North Arabia. The oldest datable attestation of Ruḍà is found in cuneiform transcription, in the Esarhaddon prism. The text recounts the conquest of the oasis of Dūmat by the Assyrian king Sennacherib (705–681 bc).Footnote 7 He carries off as booty a number of idols, including one called dru-ul-da-a-a-u.Footnote 8 The local North Arabian inscriptions from the area of Dūmat—the so-called Dumaitic inscriptions—attest the same divine name as rḍw, suggesting the pronunciation /ruḍaw/ = [ruṣ́aw].Footnote 9 Ruḍaw is in fact one of the most commonly invoked deities in several Ancient North Arabian corpora. He is frequently called upon in the Thamudic B inscriptions as well as in Safaitic. Curiously, however, he is absent in Hismaic, Dadanitic, and the Nabataean inscriptions, which share a partially overlapping geographical space.Footnote 10 In the inscription WTI 23, Ruḍaw is invoked besides nhy and ʿtrsm, both deities attested in the Esarhaddon prism.Footnote 11 The same formulaic invocation is attested in Thamudic B, Safaitic, and in Oasis North Arabian.Footnote 12

Dumaitic

WTI 23Footnote 13

h rḍw w-nhy w-ʿtrsm sʿd-n ʿl-wdd-y

‘O Rḍw and Nhy and ʿtrsm, help me in the matter of my desire’Footnote 14

Oasis North Arabian

Anon TayFootnote 15

h rḍw w ʿtrsm bġy bddh ḥywt

‘O Rḍw and ʿtrsm, may Bddh achieve (lit. reach) a long life’

Thamudic B

Mr.A 21

h rḍw sʿd bn ʿwn ʿl-wdd-h

‘O Ruḍaw, help Bn ʿwn in the matter of his desire’

Safaitic

KRS 2717Footnote 16

h rḍw sʿd ʾyb b-ḏ-wd

‘O Rḍw, help ʾyb with that which he desires’

A variant of Ruḍaw is attested in the Safaitic inscription as rḍy, presumably [roṣ́ay].Footnote 17 Incidentally, this corresponds in spelling with the form given by ibn al-Kalbī – رضى = rḍy. While there are many theories on the relationship between rḍw and the Safaitic form rḍy, I believe there is little doubt that the y-form is simply the result of a phonological/grammatical development in Safaitic, reflecting the tendency to merge III-w and III-y roots to the value of the latter.Footnote 18 This change anticipates the total merger of the two root classes in modern Arabic, a process already underway in Classical Arabic, giving rise to both رضى and رضا .Footnote 19 The prevalence of the form rḍw in Thamudic B and Dumaitic suggests that this development had not yet occurred in the middle of the first millennium bce.

Now, while it is clear that Ruḍaw was worshipped across North Arabia, stretching from Ḥāʾil to Dūmat, as far as the Syro-Jordanian Ḥarrah, there was until now no evidence as to where Ruḍaw's cult—for any period—was centered. A new Dumaitic inscription, published on OCIANA, may hold a clue.Footnote 20 The editio princeps gives the following reading and interpretation.

Transliteration

smʿ {l}-h / ʿtrsm / w rḍw / mkśd // l whb {r}ḍw / h-qrt / f smʿ l-h

Translation

{Whbrḍw} is on this black hillock and listen to him

Listen {to} him ʿtrsm and Rḍw Mkśd

Fig 1: al-Ǧawf Dum 1 (Courtesy OCIANA)

The editio princeps leaves the final word of the first line untranslated. It would appear to be a title of some sort, but the root kśd is not productive in Arabic or any other closely related language. Moreover, the m- before it would seem to suggest—if it is to be taken as a title—that it is a participle. Since it is modifying rḍw, the absence of the definite article is unexpected. I would like to suggest a new interpretation of this phrase: it should be parsed as two words: m- ‘from’ and kśd ‘Chaldea’.

This interpretation is supported by the m- + toponym pattern attested in both Safaitic and Nabataean. In a recent article, I have suggested that this title signifies the deity's cultic center or mythological residence, in contrast with the use of b- which signifies a local manifestation or cult.Footnote 21 Thus, in Nabataean the goddess Allāt is invoked based on her manifestation at regional cults, ʾltw dy b-ʾrm ‘Allāto who is at ʾIram”; ʾlt ʾlhtʾ d(y) b-bṣrʾ ‘Allāt the goddess who is at Bostra”,Footnote 22 but once she is called upon as ʾlt mn ʿmn{w} ‘Allāt from ʿmnw’. The same title is found in Safaitic, once as m-ʿmn (C 2446) and once as mn ʿmn; in the same inscription Dusares is also called upon as mn rqm ‘from Petra.’Footnote 23

The term Chaldea originally signified a group of West Semitic immigrants in southern Mesopotamia, which then became a geographic term referring to the southern extremity of Babylonia, the territories inhabited by these Chaldean tribes (see below). In the Bible, Chaldea is basically synonymous with Babylon—Nebuchadnezzar II is called both king of Babylon and king of the Chaldeans.Footnote 24 This, however, appears to be an exonym employed by biblical authors; the title ‘king of the Chaldeans’ is not employed by the “Chaldean dynasty” founded by Nabopolassar in cuneiform texts. Would, then, the Arabs have also employed this exonym? It is possible. Jeremiah mentions that Nebuchadnezzar II fought against Qaydar during his Levantine campaigns and so if the exonym “Chaldean” was employed in this period, it is possible that it had spread to Arabia as well.Footnote 25 In South Arabia, too, the term ks2d signified southern Mesopotamia, geographical Babylonia.Footnote 26 The appellative seems to survive into the late 1st millennium bce, where it is attested once in Safaitic.Footnote 27 The title king of Babylon, mlk bbl is attested in a number of Oasis North Arabian and Taymanitic inscriptions from the region of Taymāʾ, and so it would seem to be the case that the Arabian situation paralleled that of the Bible, where kśd and bbl were interchangeable.Footnote 28

Chaldea, as a geographic term, referred to the southern edge of Mesopotamia. Chaldean territories lay between Babylon and Uruk, extending as far as Nippur.Footnote 29 It may be significant then that in this same area, Arab settlements are reported in cuneiform sources. Eph'al makes note of several towns associated with Arabs in 8th c. bce Babylonia, all within Chaldean territory—in the territories of the tribes Bīt Dakkuri and Bīt Amukani.Footnote 30 He goes on to note that a number of Dispersed Oasis North Arabian inscriptions from these same areas have been discovered and/or exhibit a Mesopotamian style, pointing towards their original provenance, and further underscoring a link with the populations of North Arabia.

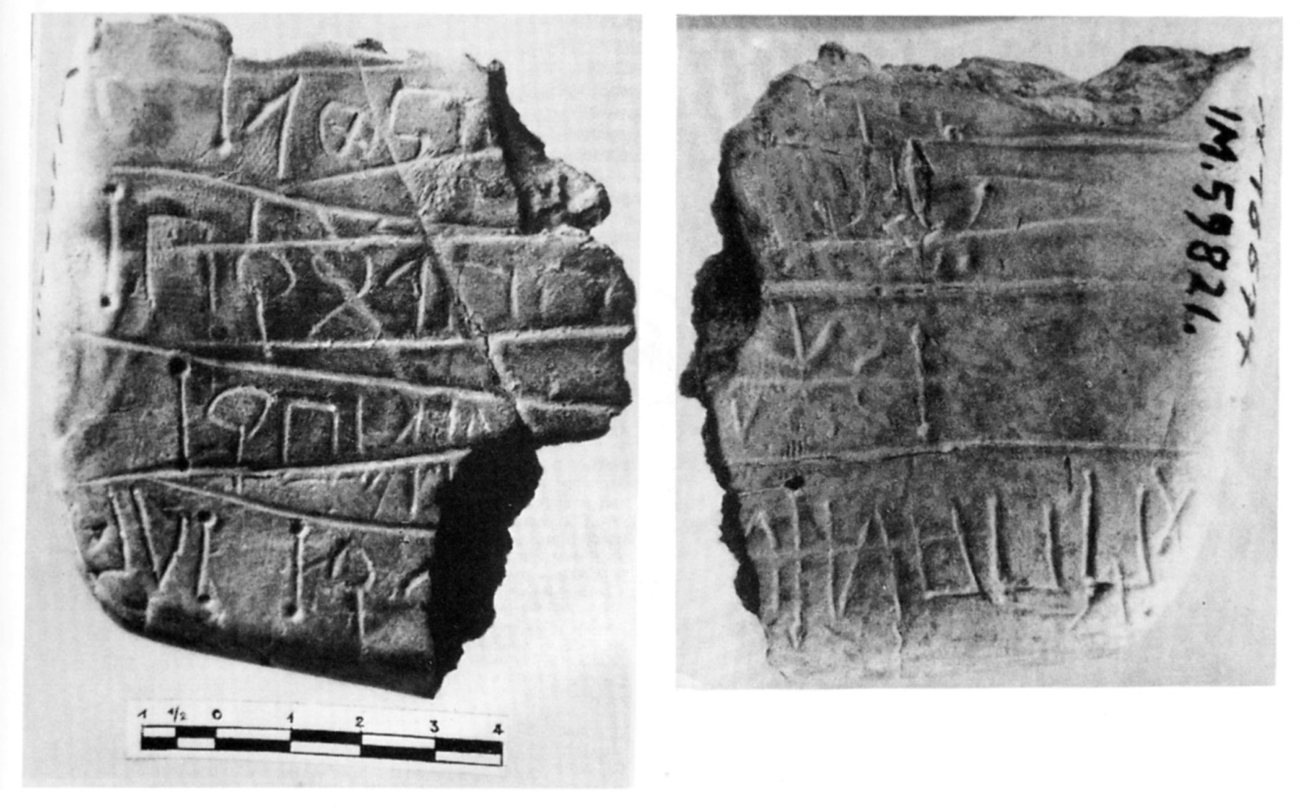

Fig 2: Seal, provenance unknown, likely to be from southern Mesopotamia (courtesy OCIANA)Footnote 31

Fig 3: Uruk Tablet (courtesy OCIANA)Footnote 32

These settlements appear to have remained in place into the early Achaemenid period. Documents from the archive of Nergal-iddin mention a place near Nippur called URU ša lúAr-ba-a-a, that is, ‘the city of the Arabs’, well within the traditional geographic boundaries of Chaldea.Footnote 33

While the evidence is extremely limited, the presence of groups called Aribi (with other allophonic variants), personal names of chieftains that have an Arabic etymology, and the presence of Dispersed Oasis North Arabian inscriptions concentrated in Chaldea together strongly suggest that the groups called “Arabs” in Akkadian sources were indeed connected to populations in North Arabia. In this light, the title m-kśd may suggest that a major cult site of Ruḍaw was located among these communities, to which North Arabians may have visited on pilgrimages. Or perhaps the phrase should be understood in terms similar to זֶה סִינַי ‘(he) of Sinai’ (Ps. 68:9; Judges 5:5), a title of God/Yahweh in the Bible, and also with the preposition mī: י ְ הוָה מִסִּינַי בָּא ‘Yahweh came from Sinai’; אֱל֙וֹהַ ֙ מִתֵּימָ֣ן יָב ֔ וֹא ‘God comes from Teman’.Footnote 34

Thus, Chaldea may have been considered the mythological residence of Ruḍaw. Only the discovery of new texts can help arbitrate between these two options. The absence of direct references to Ruḍaw in cuneiform Akkadian texts indicates that this divine name was used exclusively by Arabian communities, perhaps locally and certainly further away in the Peninsula.

Ruḍaw's place in the pantheon

There is a large literature on the identity of the deity ruḍà and what exactly s/he signified.Footnote 35 A clear understanding of this matter is challenged by the laconic nature of the inscriptions and uncertainties regarding their chronology. Ruḍaw is invoked in Ancient North Arabian inscription spanning from Central Arabia to the Syro-Jordanain Ḥarrah, perhaps over a span of a millennium. We cannot be sure – and indeed it may be unlikely—that these communities had a unified mythology of Ruḍaw, or any other deity they shared in common. With this in mind, the next paragraphs will be an experiment in the synthesis of the information we have from the pre-Islamic sources. I regard the conclusions I come to as tentative—merely possible—until better documentation comes forth.

The most popular opinion holds that Ruḍà was a female figure, but this, I think, is based on a misunderstanding of the evidence. The main arguments rest on the supposed use of feminine verbs with rḍw/y as the subject and the association of a drawing of a female figure with a nearby rock inscription mentioning rḍw/y.Footnote 36 I have explained elsewhere that neither of these claims can withstand scrutiny.Footnote 37 As Healey already points out, the connection between rḍw, which is just one of four gods invoked in C 4351, and the drawing on the same stone is not established. In fact, it is perhaps significant that there are no clear examples of the representation of deities mentioned in invocations in the rock art.Footnote 38 The second piece of evidence is the supposed feminine verb is ʿwdt ‘to grant a return’, followed by rḍw in C 5011.Footnote 39 One, however, is not required to interpret this form as a feminine verb; it could very well be an infinitive of command.Footnote 40 We can see clearly that -t augmented forms can accompany a male deity, where the “verb” should be taken either as an infinitive or a second person form – for example:

KJC 115Footnote 41

smʿt ḏśry l-zdn w-ʿṣb-h h lt l-ʾl kn

‘May Ḏśry give ear to Zdn and O Allāt, make him chief of the lineage of Kn’

A couple of Safaitic inscriptions may suggest that Ruḍaw was in fact male.

AWS 283Footnote 42

h ʾlt bnt rḍw flṭ m-snt h-ḥrb flṭʾl bn ḫzr bn ḫḏy bn wkyt

‘O Allāt daughter of Ruḍaw deliver Flṭʾl son of Ḫzr son of Ḫḏy son of Wkyt from the year of war’

AWS 291

h ʾlt bnt rḍw ġwṯ-h ḥld bn ḥḍrt bn ʾbrr w-l-h h-dr

‘O Allāt daughter of Rḍw, remove affliction from him, Ḥld son of Ḥḍrt son of ʾbrr, while here at this place’

That ʾAllāt is called the daughter of Ruḍaw suggests that the god is a male figure, as genealogies are always patrilineal in Safaitic (and Thamudic B). Now Ruḍaw's identity would seem to be linked to Allāt in the Safaitic tradition, if we may speak of such a thing. In North Arabia, the matter may be slightly different. Allāt is rather rare in the Thamudic B inscriptions and has not yet appeared in Dumaitic or the so-called dispersed Oasis North Arabian texts. Instead, there Ruḍaw appears alongside a different set of gods, each rare or unattested in Safaitic. In WTI 23, cited above, Ruḍaw is accompanied by Nuhay and ʿAttarsamē. The latter is clearly a manifestation of Venus, ʿAṯtar, followed by a reflex of the word for ‘sky’.Footnote 43 The loss of the interdental may reflect a local linguistic development, namely, regressive assimilation, ʿaṯtar > ʿattar, or it may indicate that the name was borrowed from Aramaic, where the change ṯ > t is regular. The astral signification of ʿAttarsamē may also imply that Ruḍaw and Nuhay were also astral.

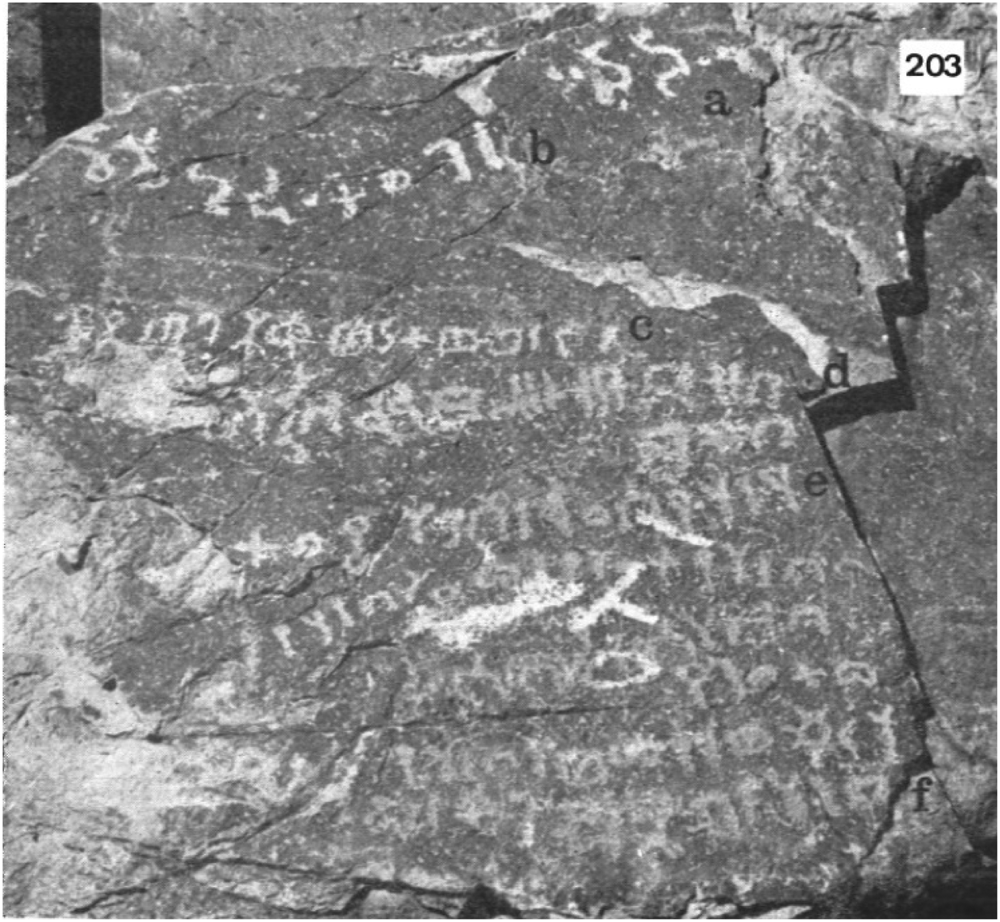

A Thamudic B inscription from Ḥāʾil presents Ruḍaw with Nuhay, and this time Shams.

Hu 789e

h nhy sʿd-n ʾlh ṯʿt

b-nhy tʿzy nm whbnhy

b-k hs{r}{r} śms

mtʿly

h rḍw nqm whbnhy

Translation

O Nuhay, help me, god of (my) salvation

Through Nuhay comes mercy for Wahbu-Nuhay

Through you comes satisfaction, O (divine) Sun

Ever-exalted

O Ruḍaw, avenge Wahbu-Nuhay!

Fig 4: Hu 789e (Photo courtesy OCIANA)Footnote 44

Returning to the matter of Allāt, many scholars have suggested that this deity corresponds to ʿAṯtar / Isthar.Footnote 45 This could be supported by the fact that ʿAttarsamē and ʾAllāt seem to have a complementary distribution in the inscriptions—Allāt is common in Safaitic, Nabataean, and Hismaic, where no reflex of ʿAṯtar is attested, while the opposite distribution is true of Thamudic B. Indeed, only a handful of texts invoking Allāt in this script type are known, and these limited exceptions may reflect a late diffusion of the western divine name to Thamudic B writers. Allāt is not attested in the Oasis North Arabian inscriptions, with the exception of a single Dadanitic text.Footnote 46

Healey presents three opinions on the identification of Allāt in her Nabataean context: the moon, Venus, and the sun.Footnote 47 Healey himself favors the identification with Venus, and presents the hypothesis that Allāt and Al-ʿUzzà were in fact the same deity, the latter being her epithet, ‘the mightiest’. Indeed, Herodotus explicitly identifies an Arabian goddess called αλιλατ, at least in some manuscripts, with Ourania, which Healey takes as a connection with Aphrodite.Footnote 48

A. Al-Manaser published an important invocation in Safaitic that provides the only known epithet of the goddess in that corpus:Footnote 49

MSSaf 6

h ʾlt mlkt ṯry sʿd bnʿm qsy bn zgr bn śrb w-rʿy bql w h rḍw mḥlt l-m-ʿwr

‘O Allāt, queen of abundance/fertility, help Bnʿm Qsy son of Zgr son of Śrb and he pastured on fresh herbage, and O Rḍw, may whosoever effaces (this writing) experience a dearth of pasture’

The title mlkt ṯry is difficult to interpret. A. Al-Manaser suggested a connection with the Arabic noun ṯarà, that is, ‘moisture’ or ‘moist earth’, or possibly ṯurayyā, the ‘Pleiades’.Footnote 50 We should, however, be mindful of the fact that roots with final y and w have more or less merged in Safaitic. This means that ṯry can correspond to the Classical Arabic root ṯ-r-w, which gives rise to the verb ṯarā ‘to become many, great in number, quantity; to increase’. This ‘abundance’ can easily be seen as an aspect of fertility, one of the core qualities of Inanna/Ishtar/Aphrodite. Thus, the title would seem to be compatible with the view of Allāt as a Venusian deity.

So then, if we accept the identification of Allāt with ʿAṯtar / Ishtar, and specifically ʿAttar-Samāyīn, following I. Rabinowitz,Footnote 51 then we can combine this with the Safaitic tradition, where Allāt is regarded as the daughter of Ruḍaw. If this mythological complex has an origin related to the Mesopotamian myths of Ishtar / Inanna—which could be supported given that Ruḍaw has a “Chaldean” center/origin—then, following Knauf, it is possible to view Ruḍaw as a lunar deity, the equivalent of Nanna / Sîn.Footnote 52 If this is correct, then it may lend further support for the reconstruction of an ancient Arabian astral myth, pairing the Moon and Venus. In Mesopotamia, and perhaps in North Arabia, the relationship was that of Father and Daughter, while in Ancient South Arabia, ʿAṯtar was the progenitor of the moon god.Footnote 53

Concluding Remarks

To conclude, I offer a new translation of Al-Ǧawf Dum 1. I will begin with the second line, as photographed.

Revised reading and translation

l whb{r}ḍw/h- qrt/f smʿ l-h

smʿ {l}-h/ʿtrsm/w rḍw/m-kśd

By Whbrḍw, (who is at) this rock, so may they (the gods) give ear to him

May ʿAttarsamē and Ruḍaw from Chaldea, give ear to him!

Coming back full circle to the account given by ibn Isḥāq of Ruḍà, we might now ask: was Ruḍà actually worshipped on the eve of Islam? It seems unlikely. The inscriptions of West Arabia dating to the centuries prior to the rise of Islam show no trace of Ruḍà, and he is not mentioned among the small number of named pagan deities in the Quran. The same is true in North Arabia and the Ḥarrah—there is nothing to suggest the survival of Ruḍà's worship past the 4th c. ce. In fact, there is so far no evidence for the worship of the old gods past the 5th c. ce in the epigraphy. The documentation we do have that dates to later centuries—although scarce—is completely monotheistic.Footnote 54 So then, how was Ruḍā remembered? It is of course possible that he remained venerated among marginal groups who did not produce inscriptions, or at least any we have discovered yet, but the uncertainties about his character and the absence of any memory of his person, supports Hawting's view, namely, that the stories of the destruction of the idols were literary tropes rather than records of actual events. This position is well supported by the epigraphic landscape of the 6th c. ce, at least at the current moment.

I would suggest that anthroponyms served as an important medium for the preservation of the knowledge of pagan deities. While such names may have fallen into disuse, or would have been less popular in monotheistic times, it is possible that names like ʿabdu-ruḍà survived in tribal genealogies and gave later generations a sense of what was worshipped in pagan times. Indeed, this is exactly how ibn al-Kalbī reasons that the name ruḍà must be of an object of worship. These divine names—preserved only in the opaque context of theophoric compounds—could be drawn on when crafting ‘smashing idols’ tales, whether in the early Islamic period or even earlier. This could explain how, while the names of the gods were remembered, their mythological and cultic context was completely lost, hence the uncertainties regarding what exactly Ruḍaw was.