1. Introduction

The present article is a contribution to the description of Balochi (Bal.) dialects.Footnote 1 We will present results of our research about Balochi varieties spoken by the population of African origin on the coast of Iranian Balochistan, a variety that we will call “Coastal Afro-Balochi” (CAB). The emphasis of this article will be on discussing the position of Iranian Coastal Balochi as spoken by the Afro-Baloch in comparison with other Balochi dialects; and we will specifically discuss morphosyntactic properties which distinguish CAB from other Balochi dialects of Iran on the one hand and Coastal dialects of Pakistan on the other.

Our material consists of folktales, life stories and procedural texts (e.g. how to produce various milk products) recorded from male and female informants of different ages and different social backgrounds and from different towns and villages on the coast of Iranian Balochistan (see Map 2) in 2010 and 2014.

1.1 Baloch in Africa and Africans in Balochistan

While it may seem surprising to find people of African descent in Balochistan, contacts between the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa date back a long time. The presence of Baloch communities in the Gulf States is particularly well known, and since the nineteenth century,Footnote 2 some Baloch have also gone to East Africa and settled there. These migration patterns will not be discussed in this article.

Conversely, people from East Africa have come (or rather: been brought) to Iran and other regions along the coast of the Indian Ocean for many centuries,Footnote 3 and the African origin of some Balochi speakers is obvious. They will henceforth be referred to as “Afro-Baloch”.Footnote 4

In Iran, slavery was abolished in the early twentieth century, but people of African descent still constitute a marginalised group of Iranian society and in the more remote regions, they have continued to live in very poor conditions. In Iranian Balochistan, people of African descent are sometimes described as “Black” by others, though they do not see themselves as such. Also, they are often referred to as golām (cf. Persian ġolām ‘slave’) both by others and by themselves (as opposed to balōč referring to the non-Black members of society). Since Baloch society continues to place importance on tribal affiliation, terms like golām and nōkar ‘servant’ are even used as “tribe names” for the Afro-Baloch in light of them not belonging to any traditional Baloch tribe. The Afro-Baloch themselves do not trace their origins to Africa, and from their point of view, they are ethnically no different to the Baloch population of their respective region. However, Balochi speakers of non-African descent see them as a distinct group, do not intermarry with them and place them at the bottom of the social hierarchy; this bitter and at times brutal reality is reflected in some of our recordings.Footnote 5

1.2 Afro-Balochi

To our knowledge, there is as yet no description of the speech of any group of the Afro-Baloch. The first question that arises is whether there might be traces of African (presumably, East African) languages in the speech of the Afro-Baloch. In our data, we have not found any such traces. Farrell (Reference Farrell2003), pp. 169, 173, studying influences on the Balochi of Karachi and mentioning the possibility of influence from African languages, was only able to find one item, na ‘and’, which according to Farrell (Reference Farrell2003), p. 184 is “used to conjoin nouns, especially names” and might be connected to Swahili na. The lexemes of possible African origin that BurtonFootnote 6 collected from the Afro-Baloch in Karachi, at least some of which are clearly from Swahili (na is not on Burton's list), are no longer in use according to Farrell's investigations. However, it might perhaps be worthwhile to double-check these findings, as Farrell's observations may refer to possible African elements in the speech of the non-African Baloch in Karachi.

Conversely, there seem to be traditions that are specific to the Afro-Baloch, particularly healing ceremonies.Footnote 7 We have been told that Swahili is used in such ceremonies, and it is confirmed by Farhat Sultana, who notes that gwāt spirit healers on the coast of Pakistani Balochistan “speak a dialect which is a mix of Swahili and Balochi”.Footnote 8 However, we have not witnessed this ourselves yet.

An investigation of the speech of the Afro-Baloch is interesting also for reasons of their status as a distinct social group; moreover, owing to their marginalisation and limited access to education etc., their speech might present features that are less seen in other sectors of Baloch society. In Bahukalat and Pishin, some Baloch who are not of African origin told us that the Afro-Baloch “talk differently” (concerning the pronunciation). Given that our data does not show such differences, it seems to us that the impression conveyed to us may reflect the social reality of the Afro-Baloch, who are seen as a distinct group by others, rather than a linguistic reality.

The term “Afro-Balochi” is thus neither meant to presuppose the existence of a set of dialectal features common to all Afro-Baloch, nor of differences between the dialects spoken by them and those spoken by the Baloch of non-African descent living in the same regions. The term “Coastal Afro-Balochi”, chosen for this article for the reasons of brevity, should thus be understood in the sense “Coastal Balochi as spoken by the Afro-Baloch”, reflecting the social background of the speakers consulted for this project.

This said, we think that Afro-Balochi might be slightly more conservative linguistically, owing to marginalisation and limited access to education etc. Also, we made it a point to record chiefly (but not only) female informants. Given the traditional nature of Baloch society, male linguists have not had access to women, and to our knowledge, Balochi data and published texts have so far nearly exclusively been from male informants.Footnote 9 It is thus possible that some of the archaic features noted below may also be due to Afro-Baloch women's particularly low exposure to other dialects and languages.

1.3 Iranian Coastal Balochi

The dialects spoken on the coast of Iranian Balochistan have not been very well documented yet, although a number of works have mentioned various specific features.Footnote 10 It is generally assumedFootnote 11 that they correspond by and large to those spoken on the Pakistani coast and belong to the “Coastal Balochi” group of Southern Balochi (cf. Map 1).Footnote 12 On the other hand, studies on Balochi dialects spoken in IranFootnote 13 published in recent decades have highlighted marked influence from standard Persian, particularly in the nominal system and the case marking and types of alignment that follow from it, rendering these dialects quite different from Pakistani Coastal Balochi. But most studies of Iranian Balochi focus on dialects spoken in the northern and central parts of the province Sistan-va-Baluchestan, so what kind of pattern an Iranian variety of Coastal Balochi (or: a coastal variety of Iranian Balochi) would show is not quite well known.

Map 1. Approximate location of Balochi dialects

Map 2. Region where Afro-Baloch communities are living in Iran (underlined: CAB data)

It needs to be stressed that Coastal Balochi of Iran is not a uniform dialect, and the same is true for its varieties spoken by the Afro-Baloch. As is the case for other parts of Balochi society, there are notable dialectal differences; these will be noted below where appropriate.

1.4 Transcription and other technicals

As is common for Balochi dialects in Iran independent of their belonging to the Western or Southern group, the pronunciation of the vowels is adapted to that of Persian, so that the short vowels (/a/, /i/, /u/ in other dialects) are pronounced as /a/, /e/, /o/ in CAB, and thus noted here. Nasal vowels are noted as such where we hear them; this does not imply that nasal vowels are phonemic in CAB (they probably do not contrast with vowel + n).

Examples from our recordings and from published sources are slightly phonemicised, and examples quoted from other sources have been adapted to the system used here, some glosses are added. The CAB examples specify the place where the recording was made with the initials of the informant, the text number of this informant and the sentence number.

2. Nominal system

2.1 General points

Historically, Balochi shows a split-alignment system with nominative-accusative alignment in clauses whose verb forms are based on the present (prs) stem (intransitive subject and transitive agent in the direct case, objects in the oblique case), and ergative-absolutive alignment for those based on the past (pst) stem (agent in the oblique, subject and direct object in the direct case). The pronominal clitics (enclitic pronouns, pc) are used in the historical functions of the oblique case (i.e. for direct and indirect objects, for the agent in the pst domain and for possession). Many Balochi dialects have diverged from this system, though, and all types of alignment (nominative, ergative, neutral, tripartite) are found in some dialect or the other.Footnote 14 Balochi also shows differential object marking (DOM), which means that only definite direct objects are marked as such in the prs domain while indefinite ones are unmarked (thus appear in the direct case).

2.2 Nouns

2.2.1 Case systemFootnote 15

One point in which Balochi dialects diverge considerably is the nominal system. The nominal system of Pakistani Coastal Balochi comprises a direct (dir), oblique (obl), object (obj) and genitive (gen) case (Table 1), the obj case showing an element -rā which is affixed to the form already marked by the obl ending.Footnote 16

Table 1. Case system of nouns in Pakistani Coastal Balochi

Conversely, many Iranian Balochi dialects exhibit a major refashioning of the case system (probably under the influence of Persian), viz. a coalescence of the direct and the oblique case to yield what may be called a nominative case (Table 2), and to a certain extent also a substitution of the eżāfe constructionFootnote 17 for the genitive case.Footnote 18

Table 2. Case system of Iranian Balochi

The case system shown by our CAB data diverges considerably from both of these systems. The suffix -rā does not occur on nouns at all. The plural ending -ānā or -ānrā is not found either. This means that CAB differs from Pakistani Coastal Balochi in not having a separate object case; instead, it has a system of only three cases (Table 3).Footnote 19

Table 3. Case system of nouns in Coastal Afro-Balochi from Iran

2.2.2 A locative case?

There are some instances of an oblique case ending affixed to a genitive (1)-(3).

This looks like the “locative” case of Afghanistan and Turkmenistan Balochi (4):Footnote 20

In an earlier article, I argued that in Afghanistan Balochi, the locative occurs more or less exclusively on nouns and pronouns with reference to humans,Footnote 21 as in the instructive example (5), which opposes the oblique gis-ā “to the house” to the locative āǰizag-ayā “to (that) woman”:

I also argued that the way the “locative” is employed in Afghanistan Balochi shows an earlier situation vs. the more general use seen in Turkmenistan Balochi, and that the motivation for the rise of the locative may be seen in the context of a typological constraint as to the possibility to apply local deixis to persons.Footnote 22 The locative marker, being the oblique case marker suffixed to that of the genitive, literally means ‘at [the place] of’ and is thus a periphrasis similar to English and French (6).

The “locative” pattern occurs only in some rare cases in our CAB data; it seems to be limited to humans, and not systematic even there (usually one would say, e.g., X-ī lōg-ā ‘at X's house’). From the isolated examples, it is questionable whether the pattern should be called a separate case; the occurrences might be better analysed as free combinations of the adverbial obl ending on a noun already marked as genitive. If so, the pattern found in CAB could be the protoform of the more regular use seen in Afghanistan and Turkmenistan.

The remaining instances of word-final -īya appear to be the combination of the clitic marking specificity (often called “indefinite article”) =ē plus oblique ending,Footnote 23 assimilated to īya, as in (7).

2.2.3 The clitic = o

There are (rare) instances in our data of a clitic = o occurring on a definite noun (8), (32).

The status of this element is as yet unclear, but it seems to us that it might be connected to the various markers of definiteness, specificity and referentiality appearing in forms such as -ak(a), -ū etc. in other Iranian languages.Footnote 25 For Koroshi, a suffix -ok has been noted, which “contributes to a definite singular interpretation of the word to which it is attached”;Footnote 26 there is also a suffix -o that “sometimes” attaches to adjectives and seems to retain more of the probably originally diminutive semantics since it is particularly found with kas(s)ān ‘small’.Footnote 27

Given that the CAB clitic is rather rare, it is unlikely to be a definite article (unlike parallel elements in some of Kurdish). Just as Dolatkhah, Csató and Karakoç (Reference Dolatkhah, Csató, Karakoç, Csató, Johanson, Róna-Tas and Utas2016), p. 285, observe for Koroshi -ok, the instances we found of the CAB clitic occur on the first noun phrase of the sentence, which renders it a likely candidate for being a topic marker.

2.3 Personal pronouns

2.3.1 Full pronouns

Agreeing with the case system of nouns (Table 1 and 2), the personal pronouns show four cases in Pakistani Coastal Balochi (Table 4)Footnote 28 and a reconfiguring of the case system in many dialects of Iran (Table 5).Footnote 29

Table 4. Case system of personal pronouns in Pakistani Coastal Balochi

Table 5. Case system of personal pronouns in Iranian Balochi

Although nouns do not use the marker -rā in CAB (Table 3), it does occur on personal pronouns (9)-(11).

The corresponding form of the 1sg is mana/ā (12)-(13):

The forms marking core arguments and their functions occurring in our data are summarised in Table 6, where “prs” and “pst” refer to the nominative and ergative domains, respectively, and “nominative subject” includes subjects in the prs domain and intransitive subjects in both domains. Particularly noteworthy forms are in bold.

Table 6. Functions of pronominal forms in Coastal Afro-Balochi from Iran

The general picture here is that the inherited forms man (dialectally also ma), taw (also to and ta) as well as mā and š(o)mā Footnote 30 have the functions of the dir and obl cases insofar as the encoding of subject and agent and the use of these forms with prepositions is concerned. Object marking is twofold, however: CAB largely agrees with Pakistani Southern Balochi in showing the clearly innovated forms manā, tarā etc. for direct and indirect objects in the prs and pst domains, thus producing a split in the pst domain in that pronominal direct objects show a dedicated object case while nouns are consistently found in the dir case (thus unmarked).Footnote 31

Interestingly, some of the older function of the inherited forms survives in the (rare) use of man and mā for objects in the pst domain, as in (14), where ma is in a pragmatically emphasised position. This is a marked difference from contemporary Southern Balochi of Pakistan, where the 1st and 2nd person pronouns in object function need to be in the innovated oblique or object case, and yields the system in Table 7.

Table 7. Case system of personal pronouns in Coastal Afro-Balochi from Iran

2.3.2 Pronominal clitics

The pronominal clitics found in our texts are those listed in Table 8 (arranging variants by frequency). Second person pronominal clitics are not found in our data for lack of sufficient context in which they might occur.Footnote 32

Table 8. Pronominal clitics in Coastal Afro-Balochi from Iran

The pronominal clitics again indicate an intermediate position between Pakistani Southern Balochi (which uses only 3rd person pronominal clitics) and Iranian Balochi dialects, which make large use of them, particularly in those dialects that have lost the distinction of the inherited direct and oblique case (cf. Table 2).

2.4 Demonstratives

Like the personal pronouns, the inflexion of demonstratives in Pakistani Coastal Balochi shows four cases (Table 9).Footnote 33

Table 9. Case system of demonstratives in Pakistani Coastal Balochi

The demonstratives are not always treated in detail in the published sources of Iranian Balochi (this applies to the actual forms as well as to the distribution of the various stems); the available data yield the system in Table 10.Footnote 34

Table 10. Case system of demonstratives in Iranian Balochi

The various forms of the CAB demonstrative pronouns occur in the functions shown in Table 11. Isolated instances that seem questionable are marked with ⁑.

Table 11. Functions of demonstrative forms in Coastal Afro-Balochi from Iran

As in other dialects, the demonstratives are frequently found with (originally emphasizing) ham- “this/that very…” (also shortened to m-), but this element has become so common that it can hardly be said to still have emphasizing function.

No instance of a (substantival) demonstrative after a preposition is found in our data, nor is the oblique plural. Indeed, demonstratives are particularly frequent in attributive position (preceding the noun), where they are uninflected (just as they would be in other Balochi dialects).

However, two remarkable phenomena not noted for other Balochi dialects (yet) are found. One is the position of a demonstrative after the noun (15).

Just like the nouns, but unlike the personal pronouns, the demonstratives do not use -rā. Conversely, the form āī appears to be used for the genitive and the oblique case, as in pakat šmā āī košōk bey “but you will be his killer” in (32). This wider function of the form āī has also been noted for other dialects, specifically from the Western Balochi dialect group.Footnote 35 It might mirror an older situation with a general oblique that also includes the genitive (and the use with postposition), as is the function of the oblique case in Middle Iranian.Footnote 36 Besides āī, an oblique form āīā occurs, but only for the oblique functions other than the genitive.

The form of the proximal demonstrative corresponding in function to the form āī is ēšī. It seems to be the oblique of ēš insofar as simple ēš is not found in oblique functions such as the ergative agent and direct or indirect objects, but ēšī is found also in roles where one would expect the direct case (Table 12), so it is used even more widely than āī.Footnote 37

Table 12. Case system of demonstratives in Coastal Afro-Balochi from Iran

The single occurrence of a genitive ēīē appears to be based on the oblique *ēī to which the genitive ending is affixed.

The pronominal system of CAB is not particularly similar to the demonstrative system in other Iranian Balochi dialects. Instead, the CAB system goes more with Pakistani Coastal Balochi, more specifically with the system presented by Collett 1983, who has ē / ēš- for the proximal demonstrative.

2.5 Conclusion

Omitting some minor variations and the prefix (ha)m-, the nominal forms of CAB can be summarised as in Table 13.

Table 13. Case systems of nominals in Coastal Afro-Balochi from Iran

2.5.1 Nouns and personal pronouns

CAB seems to confirm assumptions on the development of the Balochi case system suggested previously. For instance, it substantiates the view advanced by various authorsFootnote 38 of the Balochi case system as being two-layered, with two markers -ā / -rā. The first one is the -ā in the obl of nouns and the obj of the 1sg pronoun, and -rā on the other pronouns of the 1st and 2nd persons; it is shared by CAB (Tables 3, 7). The second one (presumably a later addition to the system) is the -ā or -rā shown by the object case of nouns (Table 1) and the additional -rā in the object case of the SG pronouns (Table 4) in some dialects, but not in CAB.

This appears to underline the assumption that the object case started out in the personal pronouns, presumably for reasons of the higher position that the pronouns occupy on the animacy scale, favouring more specific marking of participants with high status, notably the discourse participants.

The system found in CAB is more archaic than the nominal system found in other Southern Balochi varieties. This is particularly noteworthy as the system in Table 1 is even shared by the oldest Balochi manuscript (from around 1820)Footnote 39 and by other nineteenth century sources such as Mockler (Reference Mockler1877). So far as the personal pronouns are concerned, CAB differs again from the other Southern Balochi varieties including the 1820 manuscript, but here, it is rather close to the system shown by other Balochi dialects of Iran (Table 5).

Overall, the comparatively archaic system of the inflection of nouns and personal pronouns corresponds to stages 3–4 which were suggested in Korn (Reference Korn and Schweiger2005), pp. 299f. as hypothetical steps to account for the development of the Balochi case system as a whole.

2.5.2 Demonstratives

The system of demonstrative pronouns, not discussed in Korn (Reference Korn and Schweiger2005), in CAB is noteworthy in not showing -rā either. Also, forms with the ending -ā occur besides those without (oblēšī(ā), āī(ā)), suggesting that the forms with ī (ēšī, āī) are the general oblique forms including the gen function (see Section 2.4). Forms with ī thus seem to predate the introduction of the marker -ā at least for the demonstratives, and the forms with -ā seem to be later formations, presumably modelled on the oblique of nouns.

Another interesting point is the distribution of the stems found for the demonstrative pronouns. The proximal deixis shows a paradigm composed of the stems ē and ēš. The former is employed in the direct case and in attributive position (preceding a noun), where nominals are not inflected. One might thus say that the pronoun ē is generally uninflected, while the inflected forms are provided by the stem ēš.Footnote 40

Perhaps it was an analogy motivated by the distal pronoun showing the stem ā throughout the paradigm that motivated the spread of the stem ēš into the direct case, including even the original obl form ēšī, thereby changing a previously suppletive paradigm with an uninflected ē combined with ēšī (cf. āī) as its general obl.

The co-occurrence of ē and ēš in what originally seems to have been a suppletive paradigm is reminiscent of suppletive paradigms found in other Iranian languages: it is rather typical for pronominal paradigms to show two unrelated stems (originally one for the nominative and one for the remaining cases). Such suppletivism in the pronouns is inherited from Proto-Indo-European. The main demonstratives in Old Iranian are the stems i/ay- vs. a- for the proximal and hau-/hāw- vs. awa- for the distal deixis,Footnote 41 plus (in Avestan) ha/ta- vs. aita- for a neutral one. Sogdian has a three-way system, too, adding to its proximal i/ai- and distal hau- vs. awa- the combination of the stems *aiša- vs. *ta-,Footnote 42 and showing that the inherited stems may be recombined in the individual later languages.Footnote 43

From a phonological point of view, the most straightforward derivation of ē and ēš would be from the stems ai- and aiša-, respectively.Footnote 44 Potentially likewise relevant is the fact that ē and ēš also occur as personal clitics in some Balochi dialects (though only =ē in CAB, Table 8): here, =ē is the 3sg clitic and =ēš the 3pl one.Footnote 45 One possible origin would be the Old Ir. independent pronoun gen.sgahya, gen.plaišām.Footnote 46 These forms account well for the forms of the Balochi clitics, and also agree with the fact that the personal pronouns are derived from the Old Iranian genitive (this is particularly obvious for the 1sg pronoun man, which can only derive from the Old Iranian genmana).Footnote 47 Obviously the pronominal clitics provide no motivation for the distribution of stems in the suppletive paradigm of the proximal demonstrative, but the presence of matching forms in the demonstrative and the clitic system might have reinforced each other.

3. Alignment

3.1 Ergativity

The changes in the case system shown by other Iranian Balochi dialects (cf. Section 2.2) have important consequences for alignment patterns. Besides the nominative/accusative vs. ergative split historially found in Balochi (cf. Section 2.1), patterning as shown in Table 14a-b, several Iranian Balochi dialects show a system of argument marking known as “neutral”, i.e. intransitive subject, transitive agent and object all marked identically in the pst domain (Table 14c).Footnote 48

Table 14. Case marking patterns in Balochi dialects (selection)

Agreeing with the absence of the reduction in the case system seen in Iranian Balochi (see Sections 2.2.1 and 2.3), CAB does not follow the neutral pattern in the pst domain found in other Iranian Balochi dialects. Instead, it systematically exhibits split ergativity as does Pakistani Coastal Balochi. This includes the marking of the plurality of an object with the 3rd plural ending -an(t) / -ã as is the tradition for “canonical” ergativity in Balochi, cf. (48), (50), (51), (65).

However, there are also examples where one might wonder whether the 3pl marker could refer to the indirect object. Our examples include (16)-(20):

In some instances, the direct objects could be seen as plural, thus the verbal ending could refer to the work in (16) and the food in (17). However, (18) hardly permits such an interpretation, and (16) could also be seen as parallel to the complex predicates in examples (19)-(20). In (20), it appears that the reference must be to the relatives, who in this episode asked to be shown the grave of a woman whom the Hots had carried off (cf. example 10 above).

Agreement of a verb in the pst (ergative) domain with an indirect object has not been noted for Balochi so far, but it has been observed for several other Iranian languages: This construction, which philologists have called ‘indirect affectee’ construction, is found occasionally in Middle PersianFootnote 49 (21) and SogdianFootnote 50 as well as in some New Iranian languages, cf. (22)-(23), which incidentally also use ‘give’ and ‘show’.

For Bactrian, agreement of the verb with the indirect object is regular for sentences such as (24), where the direct object is inanimate and the indirect object a 1st or 2nd person, i.e. “to give / send / … something (an object) to someone”.

This pattern is quite parallel to the Balochi examples in (16)-(20). As noted by Sims-Williams (Reference Sims-Williams2011), the Bactrian construction is an instance of differential object marking: the indirect object is marked on the verb if it is a person while such marking does not occur if the entity that something is given to is inanimate.

Indeed, in all examples of the “indirect affectee construction” that we have seen, the indirect affectee is animate, and in most cases either human or at least quasi-human as in the mythological figures in some Middle Persian examples. So the construction would be an example of differential object marking not only in Bactrian, but also in the other Iranian languages including Balochi, marking as it does the animate indirect object while the direct object (typically inanimate in constructions with verbs such as ‘give’) is marked neither by case nor on the verb.

4. Mood, tense and aspect

While the overall system of TAM forms in CAB agrees with patterns known from other Balochi dialects, our data show some forms not noted from other dialects so far.

4.1 Progressives and ingressives

Progressives are widely used in Balochi, but the forms actually found vary considerably between the dialects, and even within our data. Ingressives are not particularly frequent.

Verbal nouns used in these patterns include the present participle (prs-ān), the agent noun (prs-ōk), the infinitive, which in CAB is formed by suffixing -ag to the present stem (as in other Southern Balochi dialects, but different from Bal. dialects that have an infinitive pst-in) and the gerundive, which is derived from the infinitive by the suffix -ī.Footnote 52

4.1.1 The infinitive

Many Balochi dialects show the infinitive in the obl combined with the copula in a pattern that can be interpreted as a locational construction “be in [the position / situation of] doing something”, thus not unlike the English “continuous form”Footnote 53I am going, at the same time agreeing with the typologially common pattern of locational constructions yielding progressives.Footnote 54

While this system has been grammaticalised in Balochi dialects of Pakistan, and is used in several tenses, only a few instances occur in our CAB data. They are all in the present, and may even be limited to a certain number of common verbs. In (25), the implication clearly is ‘to be in the process of doing X just now, coming from a person witnessing the scene.

In addition to this pattern, the bare infinitive is also found (28)-(29). This pattern has not been reported for Southern Balochi dialects yet, but has been noted in Eastern Balochi.Footnote 55 In (27), the contrast between “now as the sun is rising” (progressive) and “[and] yet Hawrok is not at work” (simple present) is interesting.

Our data also show infinitives in habitual function (29), indicating a further step of grammaticalisation of this construction.

The ingressive construction with lagg- ‘start’ and the infinitive in the oblique case ‘begin to do something’ found in dialects as different and far from each other as Karachi and Turkmenistan Balochi is also attested in our data.

4.1.2 The present participle

The present participle, occurring quite infrequently in CAB, is found in (30), which is noteworthy because, unlike the patterns discussed until here, it is not a combination with the copula, but with the verb ‘do’. This construction has to our knowledge not been noted for Balochi yet.

4.1.3 The agent noun

In descriptions of other dialects, the agent noun in -ōk (formed from the prs stem), even called “present participle” by some authors, is noted as being combined with the copula to express habitual action / event, but also for one going on right now.Footnote 56

In our data, instances that come close to a progressive include (31) while other examples seem closer to agent nouns such as the two instances in (13'). (31) is also noteworthy in combining the agent noun with the verb ‘do’ instead of ‘be, become’.

It seems that the use of the agent noun is less regularised in CAB than in some other Balochi dialects.

4.1.4 The gerundive

The gerundive conveys necessity: when referring to a person, it usually means “someone who should do something”, and with an object “something that needs to be done”. Like the agent noun, the gerundive is rare in our data.Footnote 57

To a certain extent, the uses of the gerundive border those of the agent noun in that both describe a feature of the agent rather than of the action / event. The proximity of the two formations is illustrated by (32).

4.1.5 Action noun with copula

Another progressive construction, not noted for any Balochi dialect so far, involves an action noun in the oblique case with the copula. It seems that action nouns used in this way are such as also enter complex predicates, e.g. kār (34), which is otherwise used in kār kan- ‘work (lit. work do)’, or gap (33) as in gap kan- ‘talk (lit. talk do)’, etc., while the nominal element of complex predicates is in the direct case.

Maybe this pattern is based on the progressive pattern employing the infinitive discussed in 4.1.1.

4.2 Mood

4.2.1 The clitic a

There is also an interesting modal formation in our CAB data. It concerns the use of a clitic a. One might expect that this element is identical to the so-called “verbal element” a known from other dialects. In some Balochi dialects (chiefly Western Bal. from Iran, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan, but also elsewhere), this element is very common and is employed like the Persian prefix mī- (35), so that it has been described as marker of imperfective aspect.Footnote 58

In CAB, a is enclitic to the preceding word (as in a number of Western Balochi dialects, not proclitic to the following one as in some other dialects). In a number of instances, it is used in contexts describing habitual action, cf. (29), (64), (69). However, it is rather rare in our data and, unlike in Sarawani or Turkmenistan Balochi, it is clearly not a grammaticalised marker of imperfective aspect.

Moreover, it seems to have modal function in several examples, as in (36) and (38) and the second parts of (39) and (15),Footnote 59 where it occurs in contexts that in Persian would show the subjunctive.

It is not quite clear whether one should assume that the morpheme a as found in CAB is the same element as the imperfective aspect marker found in other Balochi dialects. If it is the same element, a potential semantic bridge might be found in the fact that habitual or durative and modal forms overlap in many languages, as e.g. shown by Vydrin Reference Vydrin2011 (with examples from various Iranian languages).Footnote 60 Somewhat similarly, a sentence like English Every night, I would read this book. allows a modal and a habitual reading as well. The verbal element a is found in habitual uses also in other Balochi dialects (40)-(41):

One might also compare the past subjunctive, which has both iterative and irrealis uses (42)-(43):Footnote 61

4.2.2 Permissive

Our data show several examples of a construction with bel-, i.e. the imperative of (h)el(l)- ‘let, leave’ in meanings that seem to border a permissive.Footnote 62 In (44)-(45), the literal meaning is more present, but in (46)-(47), no active ‘letting’ is involved. Other instances suggest a reading of bel as permissive, or when combined with a negated verb, prohibitive (48).

The only author (to our knowledge) who notes such a use of the verb ‘let’ is Mockler (Reference Mockler1877), p. 54, who states that imperatives for other persons than the 2nd “are expressed by using the 2nd person Imperative (with ﺑ b prefixed) of the Verb ﮛ ilag ‘to permit’” with the present tense, and sometimes with “the connective particle” ki (49).Footnote 64

4.3 Multiple verb constructions

Quite frequently, combinations of several verbs are met with that appear to refer to a single event. While the phenomenon has been noted occasionally,Footnote 65 the position of these patterns within the grammatical system of the language, and the distribution in the various Balochi dialects, is a hitherto unstudied topic.

For the vector verb and the converb patterns mentioned in this section,Footnote 66 influence from Indo-Aryan has been suggested. Such influence may surely play a role in strengthening the position of the patterns in Balochi dialects of Pakistan, but their presence in Balochi of Iran, and in Iranian languages outside the Indo-Aryan sphere, suggests that such an influence is not a necessary condition.

4.3.1 Vector verb constructions

In (50), the sequence of šoda zedag referring to fetching goat milk is reminiscent of French aller chercher (lit. ‘go look.for’, but lexicalised in the meaning ‘fetch’). Even more similar is German holen gehen (‘go fetch’) vs. simple holen ‘fetch’, which refer to the same action, but the addition of gehen contributes a nuance of ‘setting out now’.

Such patterns are very common, and occur with and without o ‘and’ in our data (51).

For other Balochi dialects, such patterns have been noted for combinations of two verbs joined by o ‘and’ such as (52); in Eastern Balochi, they employ a form called “conjunctive participle” (descriptively the pst stem with suffix -o or -au),Footnote 67 as in (53), where there is clearly no act of ‘going’ or ‘giving’ involved, thus the reference is to a single event.

It seems that such combinations contain a lexical verb in combination with a verb of movement (‘go’, ‘come’) or physical transfer (‘bring’, ‘seize’). Following Bashir (Reference Bashir2008), pp. 65-75, we use the term “vector verbs” for such verbs. As noted by Bashir (Reference Bashir2008), p. 74, “the second (vector) verb contributes aktionsart or aspectual meanings”.Footnote 69 In Eastern Balochi the inventory of vector verbs (including ‘throw’ and ‘rise’) is exactly parallel to that found in Indo-Aryan.Footnote 70

Interestingly, the case marking of the subject in (53b) and (54) is the one required by the vector verb and not the one for the main verb. This corresponds to periphrastic constructions such as the continuous form and the potential construction, where the transitivity feature of the auxiliary (‘be’ and ‘do’, respectively) cause the construction to pattern nominatively or ergatively, independent of the transitivity of the main verb.Footnote 71

Verbs of movement used as vector verbs appear to contribute nuances referring to the phase of an action, such as ‘go’ (53) and ‘come (out)’ (54) implying the beginning of an action. Verbs of physical transferral could perhaps be seen to imply directionality, thus ‘bring’ in (51) and ‘seize’ in (55).

These patterns may be particularly common with pst or prf forms but, as already seen in (55), they are not excluded from the prs system either. Vector verbs also occur in imperative contexts. In (56), ‘let's sell him’ would seem the most adequate interpretation, and the straightforward reading of (15) would be ‘Now let's kill the lion and govern ourselves’ (there is no going or coming involved in either context). In (57), an interpretation ‘I'll have a look’ would seem quite viable. To some extent, this is reminiscent of French Allez, which is generalised for commands, e.g. Allez, viens ! ‘Come here! (lit. go.2pl, come.2sg)’ (used e.g. when addressing a child or a dog), or to English Come on, ...

4.3.2 Converb constructions

A related pattern is the combination of two verbs for what likewise appears to be a single action, but without the type of semantic bleaching seen in the case of “vector verbs”. Instead, the meaning contributed by one of the verbs approaches that of an adverb of manner, as hakalet ‘moved’ in (58), the lifting of the eyes in (59) (brides are supposed to keep their eyes downcast) and the jumping and running of the schoolchildren in (60).

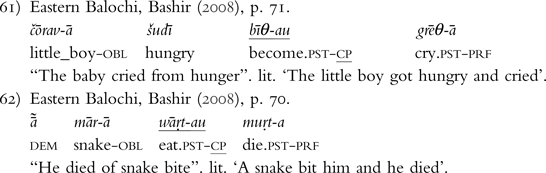

This phenomenon has likewise been noted by Bashir (Reference Bashir2008), p. 68, for the Eastern Balochi “conjunctive participle” mentioned in Section 4.3.1, which “can function as an adverbial in a monoclausal sentence”, as in (61). This pattern is possible in Eastern Balochi even with different grammatical subjects (62), which is a noteworthy difference from the otherwise quite parallel Indo-Aryan “conjunctive participle”.Footnote 72

The verb contributing the semantics of manner has the form of the pst or the prf stem, identical with the 3sg. As noted by Farrell (Reference Farrell2003), pp. 200–204, for Karachi Balochi, the non-final verb of a series could be interpreted along the lines of an Indo-Aryan “conjunctive participle” (or a Turkic converb, for that matter), particularly if they show signs of being somewhat less than finite e.g. when the subject does not show the case marking normally required by the verb in question; this is seen e.g. for bīθ-au in (61) and wāṛt-au in (62).

As pointed out by Bashir (Reference Bashir2008), p. 66, there is not necessarily a strict borderline between instances that can be analysed as combinations with converbs or vector verbs and other verb pairs; rather, these “constitute a continuum of grammaticization of verbal conceptions” ranging from less to more closely bound verbs. So there is some fluidity between expressions of several events and those that refer to a single event.

4.3.3 Repetition

Quite frequently informants use a verb form several times in a row to describe a single event rather than several separate actions, in order to express either the duration of an action or its being iterative. In (63),Footnote 73 the repetition of šot ‘went’ contributes the meaning of the passing time rather than describing a series of separate actions. In (64), a nuance of intensity may be present in addition to the duration, and in (65), the duration of the cooking could be seen to be associated to the amount of fish.

A slightly different case is present in instances where a speaker resumes a preceding sentence after having been interrupted, as in (66); this is not a real instance of a repeated verb.Footnote 74

4.3.4 Additional copula

Quite commonly the 3rd singular copula is suffixed to a finite verb form of the 3rd person present. This is most frequent with hast (exist.prs3sg) and its negated form nēst (thus hast=ẽ, nēst=ẽ and, for the pst, hast-at exist-cop.pst3sg), and particularly so (but not entirely systematically) at the opening of a tale for ‘There was a…’ (67), but also occurs on other verbs (and not only on forms of the 3sg) and inside a tale (68) or a procedural text (69). The frequency of this phenomenon is subject to dialectal differences within our data.

The phenomenon has been discussed by Farrell (Reference Farrell2003), pp. 190–193, who notes its existence “in Coastal dialects along the Makran” also into Iran. He does not make a decision about the identity of the element “ē̃” and treats it as a different phenomenon than ast ē̃, which shows inflexion insofar as it has a plural ast-ā̃, while the element “ē̃” is uninflected and suffixed to sg and pl forms.

Following Jahani and Korn (Reference Jahani and Korn2009), p. 685, we assume that the element is indeed the 3rd singular copula. One might explain the fact that it inflects only when affixed to (h)ast and nēst by suggesting that the 3sg copula is on its way of becoming a fossilised grammaticalised element.

Farrell (ibid.) mentions the interpretation by Sayad Hashmi, who said the form is a “distant future”, but concludes that this does not hold for his data (nor does it for ours, see the examples above). Its being comparatively frequent at the beginning of tales might suggest that it introduces new material, but this does not seem to fit all instances. Nevertheless, the additional copula might perhaps be a discourse related phenomenon.

5. Summary

5.1 In this article, we describe some elements of the grammar of Coastal Afro-Balochi (CAB) of Iran, i.e. the dialects spoken by the Baloch of African origin living in the Coastal area of Iranian Balochistan. In doing so, we are in no way claiming the existence of a difference between the varieties spoken by the Baloch of African and other origins.Footnote 75 In this sense, there is no “Afro-Balochi” as opposed to the varieties spoken by other members of Baloch society in the same region. Nevertheless, we argue that, as the speech of a marginalised faction of the community, and potentially with a lower degree of social and geographic mobility, the speech of the Afro-Baloch might have been less exposed to influences from other dialects and languages and might have preserved archaic characteristics, as it is often the case with geographically or socially isolated communities.

5.2 It has generally been assumed that the Balochi spoken on the coast of Iranian Balochistan corresponds to that spoken in Pakistani Balochistan. This is surely largely correct. However, there are some notable differences, and our data show a number of phenomena that are synchronically and diachronically noteworthy.

These include the CAB case system for nouns and demonstrative pronuns, which is composed of only three cases (direct, oblique, genitive) and does not have the object case attested all throughout Pakistani Balochi (Southern, Western and Eastern dialects). Here, Coastal Afro-Balochi brings new precision to previously suggested lines of development and highlights some steps in the chronology of the case system.

The occasional addition of the oblique marker to a genitive ending, not noted for Southern Balochi so far, is reminiscent of the locative case in some Western Balochi dialects. Our data shows only a few instances, all of which refer to humans. This recalls the situation in Afghanistan Balochi (while Turkmenistan Balochi has extended the use to all categories of nouns), but seems to be even more limited than the latter.

The 1st and 2nd singular personal pronouns, on the other hand, do have an object case, but still reveal a stage which preceded the system of Pakistani Coastal Balochi in not having generalised the distinction of direct vs. oblique case.

Correspondingly, CAB does not show the animacy split noted for other dialects of Southern Balochi, which have nominative alignment also in the past (ergative) domain for pronouns of the 1st and 2nd persons. Ergativity is thus more “canonical” in CAB than in Southern Balochi dialects across the border (and than in other Balochi dialects of Iran).

Noted for other Ir. languages, but not for Balochi so far, is the so-called “indirect affectee construction” in the pst domain, i.e. the marking of the indirect object (rather than the direct object) on the verb. In accordance with what is seen in other Ir. languages, the available instances feature verbs such as ‘give’, for which the indirect object is regularly animate while the direct object is inanimate, so that it is the object higher in animacy that is indexed on the verb.

5.3 Phenomena in the verb system not noted yet for Balochi (or at least not for Southern Balochi) include the use of the clitic a (“verbal element”) to indicate mood, and durative constructions using the bare infinitive or a verbal noun.

In addition, certain auxiliaries and light verbs occur in our data in patterns not previously noted. The verb ‘do’, which is otherwise employed in complex predicates and in the potential, is found combined with the present participle and with the agent noun to express progressive semantics. A phenomenon hardly described for Balochi (and for Iranian in general) is the combination of several verbs describing a single event (as frequently found in, and noted for, Indo-Aryan languages). The “vector verbs” employed include verbs of motion (which are otherwise employed for forming passives and complex predicates); these appear to contribute nuances referring to the phase of an action. Likewise used are verbs of physical transfer (‘bring’, ‘seize’), which seem to add notions of directionality.

It seems that ‘go’ is also used in a hortative pattern (translatable as ‘Let's…’), and (h)el(l)- ‘release, let’ is an auxiliary for a permissive construction. Here as well, the combination with a finite verb form in the subjunctive amounts to two verbs describing a single event or action.

The latter also applies in the rather common instances of repetition of a verb form indicating repetition or duration of an action.

Potentially discourse-related phenomena, which would require further investigation, include a clitic = o, to some extent parallel to markers of specificity etc. in other Ir. languages, and a copula added to finite verb forms.

5.4 In conclusion, the study of Coastal Afro-Balochi adds a number of morphosyntactic patterns to those already described for Balochi. It remains to be studied whether these features are also present in any coastal dialect of Pakistan. At the present state of knowledge, CAB appears to be more archaic than both Coastal Balochi of Pakistan and the Balochi dialects of Iran spoken further away from the coast.

Afro-Balochi varieties are no more uniform than those spoken by other sectors of Baloch society. In line with the dialect landscape of Balochi dialects in general, dialectal differences are seen on all levels of grammar; in our case particularly in the pronominal system and in modal and aktionsart patterns. Since important parts of the landscape of Balochi dialects in Iran yet remain to be described, the present study also hopes to contribute to our knowlege in this field.

Abbreviations and glosses:Footnote 76

- agn

agent noun

- attr

attribute marker

- CAB

Coastal Afro-Balochi

- cp

conjunctive participle (see 4.3)

- dir

direct case

- dO

direct Object

- ez

ezāfe

- idO

indirect object

- obj

object case

- obl

oblique case

- pc

pronominal clitic

- pn

name

- prs

present stem; prs (nominative) domain (see 2.1, 3.1)

- pst

past stem; pst (ergative) domain (see 2.1, 3.1)

- spc

specificity marker (see 2.2)

- sub

subordinator

- v.el

verbal element (see 4.3)