Introduction

Malaysia is a quintessential ‘Little Tiger’, a member of a select group of Southeast Asian nations whose social and economic reality has been transformed. From 1961 to 2011, Malaysia's economy grew an average of 6.4% p.a. and its GDP per capita increased from USD 847 to USD 5,345, enabling it to enter the ranks of upper-middle income nations.Footnote 1

Malaysia's long-standing commitment to macro-economic stability, in particular avoiding high inflation and currency over-valuation, has been crucial.Footnote 2 Beyond this, the state played a key role in attacking rural poverty through large-scale agricultural development schemes to boost productivity in the rubber and rice sectors. Subsequently, the state began to promote export-oriented industrialisation through investments in infrastructure and marketing, as well as providing tax incentives.Footnote 3

Such feats are not easy to engineer, requiring considerable levels of state capacity to process information, identify policy needs, garner support from key allies, and successfully implement chosen measures. How, then, did the Malaysian state acquire capacity of this level?

A body of scholarship argues that the genesis of the Malaysia's strong and capable state lies in its colonial past – when it was known as Malaya.Footnote 4 During their rule, the British created a professional administrative bureaucracy that enjoyed great prestige and drew its ranks from the most educated in the country. A concerted transition to independence bequeathed the country with state structures characterised by rules-based procedures and a high degree of cohesiveness that its new leaders could then use.Footnote 5

Following independence, Malaysia's state was staffed by “well-educated” and “highly-legitimate” civil servants and had substantial extractive capacity to mobilise resources and penetrative capacity that extended throughout the national territory.Footnote 6 Relative to the colonial period, it retained its “stability, discipline, and impressive capacity to contribute to system maintenance and thus to perform routine public services predictably and effectively”.Footnote 7

This institutional legacy is not the sole explanation for Malaysia's subsequent developmental outcomes. Rather, it was an important institutional pre-condition that allowed the country's post-independence leaders to pursue their goals. Indeed, immediately following independence, Malaysia's leadership used the bureaucracy to pursue different policy objectives from the British, placing greater emphasis on economic growth, rural development, and expanded social services.Footnote 8

More recent comparative historical work nuances this argument. Lange argues that it is not British colonisation per se that accounts for the Malaysian state's high levels of capacity, but rather a specific type of colonisation. He draws a key distinction between “direct” and “indirect” rule.

Direct rule was the initial approach used by Great Britain in its colonies. Lange defines it as “the construction of a complete system of colonial domination in which both local and central institutions are well integrated and governed by the same authority and organisational principles”.Footnote 9 This entailed installing a centralised administrative apparatus of similar capacity and structure to that found in the metropolis, as well as a legal system, police force, and education system. The bureaucracy resembled the Weberian legal-rational ideal, with high levels of cohesiveness rooted in its professional cadres, meritocratic recruitment and promotion, and long-term careers. It was staffed with a large number of expatriates in key positions, and local people in ancillary positions. State control extended to include all aspects of the territory, displacing pre-existing power structures.

Following the 1857 Indian Rebellion, indirect rule was preferred by the British, due to its perceived inclusiveness and respect for the culture of colonised areas as well as its lower personnel costs. This form of rule, defined as “domination via collaborative relations between a dominant colonial centre and several regionally-based indigenous institutions” was established in newly-claimed territories in Asia, the Pacific, and Africa.Footnote 10

This form of control differed from direct rule in three aspects. First, the administrative structures set up by the British were much smaller, restricted to the capital, and had very little direct contact with the population. Second, indirect rule involved utilising existing power structures to gain control. Third, instead of displacing them, this form of rule actually involved strengthening specific traditional institutions, using existing rulers such as chiefs or sultans.

As a result, indirect rule was quicker to establish, cheaper to maintain, and allowed a small number of expatriates to have influence over large territories. Traditional rulers were allowed to maintain political and legal power in their territorial domains – particularly in the administration of customary law and religion – in exchange for taxation revenue and regular reporting. This resulted in a bifurcated state, with one smaller aspect controlled by the British, and a larger, more territorially extensive one controlled by traditional rulers. Often, these locally-controlled states were patrimonial in nature, with legitimacy based in tradition and state structures staffed with the rulers’ relatives and retinue. This led to minimal democratisation and reinforced traditional elements of pre-colonial society, thus preserving numerous patrimonial kingdoms.

These significant differences were accentuated in the run-up to independence, when major institutional changes were made. In areas under direct rule, the British enacted significant reforms to prepare them for independence, including investing significantly in health and education systems and sponsoring local government elections. In contrast, in areas under indirect rule, little or no preparations were made, and alliances were often cemented with more traditional, albeit powerful, social elements. At independence, these small capital city-based bureaucracies were often unprepared to govern.

Thus, Lange posits that direct rule provided colonised territories with more cohesive bureaucracies that had more effective implementation capacity as well as more inclusive relations with societal actors. Conversely, indirect rule left weak, patrimonial bureaucracies with little implementation capacity and limited relationships with wider society. These state structures and state-society relations then substantially affected these countries’ post-independence trajectories as, while they underwent significant change, it was in a path-dependent fashion that reinforced pre-existing institutional characteristics.

However, Malaysia's place within this schema requires some modifications – as it is an amalgam of areas that were ruled directly as well as indirectly. “When taken as a whole”, Lange asserts that the direct form of rule predominated in Malaysia. In addition to the greater proportion of the territory under direct rule, the British pursued a number of policies from the early 1900s onwards that centralised control in Malaya, such as: reforming land tenure patterns; creating new centres of administrative power that competed with royal courts; expanding the bureaucracy; and increasing state involvement in health and education.Footnote 11

Following the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), the British proceeded to centralise administrative control and expand the reach of the state, partly in response to a communist insurgency. A smooth colonial transition in 1957 meant that this institutional endowment survived intact, and independent Malaya inherited a large, territorially-extensive, and professional bureaucracy.Footnote 12

However, while the Malaysian state's organisational characteristics and capacity may derive from direct rule, an analysis of the origins of independence-era leaders offers an interesting counter-point to this argument.

The bulk of Malaya's independence leaders, who were themselves Malay, came from the higher ranks of the government bureaucracy. During the colonial period, the British pursued a “pro-Malay” policy in recruitment for government positions, in keeping with their position that the Malays were the territory's original inhabitants and other communities were there temporarily. English-educated Malays, many from the aristocracy linked to the sultans, then came to occupy the bureaucracy as well as higher levels of command of the police and military.Footnote 13

Following the return of the British in the wake of the Japanese Occupation, this elite developed a political party to protect their interests and push for independence – the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). While its party base was drawn from the rural areas, particularly village leaders and landowners as well as lower-level government employees, the party's leadership came from the upper levels of the public service. Some 80 percent of senior UMNO members were English educated, and approximately 50 percent had pursued further education in the United Kingdom. About half of its leaders were public servants, with almost 30 percent in senior positions in the civil service.Footnote 14

Later forming a coalition with other ethnically-based political parties in the early 1950s, UMNO remained the “senior partner” in the run-up to independence, due to the predominantly Malay composition of the electorate.Footnote 15

One would expect, then, most of the country's leaders to come from those areas formerly under direct rule, namely: the Federated Malay States of Selangor, Perak, Negri Sembilan, Pahang; as well as the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca. These areas were the wealthiest parts of Malaya, were under British rule the longest and, consequently, would have had the largest, most cohesive, and rules-based bureaucracies from which to draw leaders.

Furthermore, in the Federated Malay States (FMS), there was an elaborate structure to nurture local administrators for senior positions. Needing to legitimate their “tutelage” of the various sultanates, reduce personnel costs and fill personnel shortages, the British moved to create a new class of “English-educated modern Malay administrators”. In 1905, the British established: an exclusive secondary school based on the British public school model, the Malay College Kuala Kangsar, to provide high-quality English education to promising students; and, in 1910, the Malay Administrative Service (MAS). Although largely clerical in nature, this corps allowed a select number of its members to be promoted to the elite Malayan Civil Service – comprised largely of British officials of European descent.Footnote 16

From the 1920s onwards, the British began to recruit more Malays into lower and higher levels of the bureaucracy. By 1938, there were an estimated 1,700 Malay government employees in the FMS, of which some 340 were clerks in the federal and state services.Footnote 17 At the highest level, the number of MAS and MCS officers represented an additional 90 and 20 officers, respectively.Footnote 18

However, while Malay College Kuala Kangsar and the Malayan Administrative Service did groom a number of independence-era figures, a disproportionate number of leaders came from Johor. Contrary to the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States, Johor was an Unfederated Malay State and governed indirectly by the British. For much of its history, it was of little strategic or economic interest and, when colonial control was eventually extended to the territory, it was circumscribed by a range of institutions and organisations that had developed endogenously. Despite this, Johor was the only state to dominate both national political positions and senior party positions within UMNO.

With regard to national leadership positions, Onn Jaafar, the founder of UMNO and first post-war leader of national stature came from Johor. Other notable leaders include: Hussein Onn, the third Prime Minister; Ismail Abdul Rahman, the second Deputy Prime Minister; Abdul Rahman Yassin, the first President of the Senate; Mohamad Noah bin Omar, the first Speaker of the Lower House; and Awang Hassan, Deputy Speaker of the House. Furthermore, Johor, along with another indirectly-ruled state, Kedah, contributed six out of the ten UMNO members of Malaya's first cabinet, formed in 1955.Footnote 19

Within UMNO itself, the influence of Johorean leaders is equally marked. In the pre-independence period (1946–1956), the state contributed 15 out of 61 Supreme Council members – a quarter of the total and more than any other state.Footnote 20 In addition to the central leadership, Johoreans dominated the Youth and Women's sections of the party. The first and third Presidents of UMNO Youth and the second, third, and fourth Presidents of the Women's section [Kaum Ibu] were from Johor, leading these organisations up until the mid-1960s and early 1970s, respectively.Footnote 21

Conversely, areas formerly under direct rule contributed relatively few national-level politicians. Selangor, given its history, would logically have been a source of senior administrators and political leaders. Its capital, Kuala Lumpur, was – along with Singapore – the nerve centre of the colonial bureaucracy, housing the headquarters of many government agencies, such as Posts & Telegraphs, Mines, and Railways. Furthermore, Kuala Lumpur had been the capital of the Federated Malay States since 1896, hosting additional layers of federal bureaucracy. Yet, only a modest number of Supreme Council members (seven) and no cabinet members came from Selangor.

Perak was another directly-ruled state and, while it contributed a substantial number of members to UMNO's Supreme Council (12), it only had one member in the first cabinet. Penang, another directly-ruled area, also supplied a substantial number of UMNO's Supreme Council members (10), but no national leaders. Conversely, Pahang supplied a mere two people to the Supreme Council, but they both were cabinet members and one – Abdul Razak – would go on to become Prime Minister.

Other areas formerly under indirect rule, such as Perlis, Terengganu, and Kelantan did not figure prominently in either national or party leadership terms. The sole exception is Kedah which, while providing three cabinet members, supplied a mere four UMNO Supreme Council members in the crucial first decade of the party.

Using colonial-era staff directories, annual reports, and intelligence reports from the late 1930s and World War II period, this article will explore whether there is an underlying causal factor that can explain the predominance of Johor in the independence period. More specifically, it will seek to ascertain whether – like the rules-based state apparatus it transferred to the country's new leaders – the origin of Malaya's first generation of “bureaucrats-turned-politicians” is itself a result of the different models of colonisation used by the British.

Thus, this article seeks to explore the underlying structural reasons for the predominance of Malay leaders from Johor in the immediate pre- and post-independence period in Malaya. In doing so, it does not negate the agency of individual Malay leaders. Rather, it aims to set out the context within which such actors played a role.Footnote 22

To this end, this article will be structured as follows. The second will compare and contrast the different state structures the British established in Malaya, with a focus on those areas under direct rule (the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States) and Johor, which was under indirect rule. Where relevant, information pertaining to other areas under indirect rule will be brought in. The time period will be 1935–41, when British colonial rule was at its height and state structures were mature. The third section will explore the effects of the Second World War and the Japanese Occupation on the nature and composition of Malaya's collection of state structures. The fourth section will analyse the effects that this uneven process of state-building had in the immediate post-war period. The fifth section will conclude.

The State(s) in British Malaya (1935–41)

Images of the post-independence Malaysian state often centre on its cohesive, centralised bureaucracy epitomised by the powerful Office of the Prime Minister or the technocratic Economic Planning Unit. However, its colonial, pre-war equivalent was substantially different, as the state was a multi-facetted entity with separate centres of power and distinct forms in different parts of the territory. However, before analysing data from this time period, a brief explanation of the various governance arrangements and state structures the British created in Malaya is necessary.

The Expansion of British Control in Malaya

As with India, the British colonisation of Malaya occurred in phases. The Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca, and Singapore were the earliest territories claimed by the Crown. Established in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries by the East India Company, these port-cities were chosen for their strategic location on international trade routes. Following their incorporation into the British Empire as colonies in 1867, the Settlements came to have their own constitution, government, and legal system. The Settlements were ruled by a Governor, based in Singapore, who answered directly to the Secretary of State for Colonies.Footnote 23

Although characterised by patronage and intermediate levels of professionalism in its early years, by the end of the nineteenth century, the bureaucracy was staffed by highly-trained professionals recruited and trained in the same manner as their counterparts in the United Kingdom.Footnote 24 A network of District Officers ensured a state presence throughout urban and rural areas, and colonial policy stressed consistent spending on: infrastructure; basic social services; the police; and prisons.Footnote 25

In line with their focus on trade, the Settlements had an open immigration policy. As such, their ethnic composition changed, as they came to house important number of Chinese migrants, engaged in trade, finance, or commercial agriculture.Footnote 26

Thus, British colonisation of the Straits Settlements was carried out early and entailed the creation of a strong state with extensive geographic reach, staffed by highly-trained administrators. This constitutes an example of direct rule par excellence.

British expansion into other parts of Malaya took place later and for different motives. From the 1840s, business interests in the Straits Settlements began to push for greater British involvement in the Malayan peninsula due to unrest in the sultanates of Perak and Selangor related to tin mining.Footnote 27

From the 1870s onwards, the British began to consider active involvement and control in these territories. However, the British Empire was expanding quickly, resulting in severe personnel shortages. And, unlike Penang and Singapore, which were initially sparsely settled, these territories had substantial populations as well as existing institutions of governance. Perceptions of colonial rule had evolved in the United Kingdom, with the Colonial Office and Parliament reluctant to assume administrative responsibility for large swathes of territory.Footnote 28

Thus, treaties that enabled control to be established by the British were seen as “a cheap and non-committal alternative to annexation”.Footnote 29 Taking inspiration from the Residential system used in India, existing governance mechanisms were used and strengthened. Thus, from 1874 until 1888, the British negotiated and signed treaties with the Sultans of Selangor, Perak, Negri Sembilan, and Pahang. The treaties stipulated that a British Resident would be posted to each sultanate to oversee financial management and overall administration. The sultanates became protected states under the Crown, with formal sovereignty regarding internal matters, particularly those associated with religion and local custom, remaining with the sultans.Footnote 30

However, this sovereignty was largely theoretical and, in short order, the Residents were carrying out a wide range of tasks. “Advice” was given liberally by the British and, outside of matters of religion and custom, sultans were treaty-bound to accept it.Footnote 31 In addition, British influence was accentuated by the creation of many new institutions of government. In 1895, the four sultanates were federated, placed under an additional layer of British bureaucracy, and had their civil services melded into one.Footnote 32

Thus, the Residents came to head a number of governments that were staffed, at the administrative and technical levels, by a large number of British civil servants recruited and trained in the same manner as their Straits Settlements counterparts. In the 1890s, the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay State Civil Service were amalgamated, becoming separate branches of what would later be called the Malayan Civil Service.Footnote 33 And, as in the Straits Settlements, a network of District Officers extended British control over such matters as law enforcement, land use, and public works to the remotest parts of the FMS.Footnote 34 As with the Settlements, the ethnic composition of the FMS changed, as large numbers of Chinese and Indian migrants came to work in commercial agricultural and mining operations.

The government apparatus of the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States was also fused in certain areas. Thus, in the FMS, the supervision of the civil service and the four Residents was handled by a Resident-General, but overall authority was exercised by the Governor of Singapore, who was simultaneously the High Commissioner to the Malay States.Footnote 35 As will be seen, certain governmental functions such as agriculture, education, and public works were also melded, with headquarters in either Singapore or Kuala Lumpur. Thus, the FMS were, for all intents and purposes, under direct rule.

Despite the legal similarities in status with the Federated Malay States, the situation in the Unfederated Malay States (UMS) of Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu, and Johor was significantly different.

First, these five states came under British control later. The first four states were transferred from the Siamese in 1909 and subsequently signed treaties that accepted British Advisors.Footnote 36 Johor, for its part, accepted an Advisor in 1910, but only relinquished substantial powers to him in 1914. Second, the British did not have the same pressing economic concerns in these areas. The relative penury of tin in the UMS meant that British presence was modest and grew gradually. Third, from the 1870s to the turn of the century, British opinions of colonial administration had evolved significantly, with greater awareness of and sympathy for local cultural institutions.Footnote 37

In addition, the situation in the UMS themselves was also different. Their later incorporation into the British sphere of influence meant that local government organisations grew endogenously, often on the basis of ideas copied from either the Straits Settlements or Federated Malay States. In contrast to the FMS, where the state bureaucracies had to be built from scratch, the British arrived in the UMS to find councils of senior notables as well as existing civil services.Footnote 38 For example, by 1893, Johor had a government with more than 300 employees in 23 agencies, including a: treasury; audit office; police force; postal service; and public works department.Footnote 39 Given their formal advisory capacity, the British Advisers could not ignore the procedures developed in these organisations.

And, perhaps most importantly, the sultans in the UMS had exposure to the British through agents, and had also witnessed the changes that external control had brought to the FMS. They were wary of losing sovereignty, resisting overt reductions in their prestige or attempts to federate government services in Kuala Lumpur.Footnote 40 This led the UMS sultans to oppose a decentralisation plan put forward in the 1930s. Proposed by the High Commissioner, Clementi, the plan proposed incorporating all Sultanates on an equal footing in a looser federation. However, the UMS sultans feared a loss of autonomy and the Colonial Office contended that it would increase inefficiency.Footnote 41

Thus, the shorter period of British rule, lighter presence on the ground, and greater influence retained by the sultans means that the colonisation model applied to the Unfederated Malay States more closely approximates indirect rule.

State Structures in British Malaya (1935–41)

The gradual and piece-meal fashion in which the British expanded their control over Malaya gave rise to a complex, multi-centred group of state structures with different political hierarchies and staffed by British and local civil servants in differing proportions.

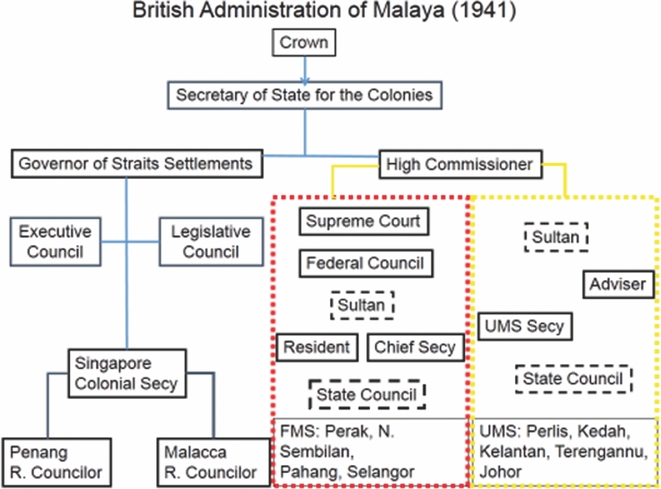

Figure One sets out the political structures of the three types of territories in the Peninsula: Straits Settlements; Federated Malay States; and Unfederated Malay States. The Straits Settlements were directly incorporated into the British political system, with a chain of command running from the Colonial Secretary in Singapore and the Resident Councillors in Penang and Malacca all the way to the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London.

Figure 1 *Headquarters in Kuala Lumpur. Source: compiled from: Directory of Malaya 1941 (Singapore, 1941); Malayan Establishment Staff List as on 1st July, 1941 (Singapore, 1941).

Figure 2 *Headquarters in Kuala Lumpur. Source: compiled from: Directory of Malaya 1941 (Singapore, 1941); Malayan Establishment Staff List as on 1st July, 1941 (Singapore, 1941).

The FMS and UMS were not actual colonies, but rather protectorates. As such, they reported to a High Commissioner, rather than a Governor. However, this was a theoretical distinction, as the posts of Governor and High Commissioner were occupied by the same person. Beyond this, the political structure of the two groups differed in important ways. The Sultans in the UMS were the paramount formal authority in their respective territories. They presided over State Councils which enacted legislation for the territory, and each Sultanate had its own Supreme Court.

In contrast, the Sultans in the FMS were beholden to a federated Supreme Court, which issued edicts for the four sultanates. Responsibility for legislation had also been moved to a Federal Council, which rendered the separate State Councils powerless. And, the FMS Sultans were a layer removed from their UMS counterparts, with their concerns channelled through a Resident to a federal administrator – variously named Resident-General, Chief Secretary, and Federal Secretary – before reaching the High Commissioner.

In functional terms, the situation was equally complex, as government services were organised in four different ways across the various territories.

The first-order functions necessary for securing territory and managing it profitably and sustainably were centrally decided for Malayan territories. Thus military policy was decided in Singapore, as were labour and Chinese Affairs. Posts and Telegraphs were also handled uniformly for the various territories, but the headquarters were located in Kuala Lumpur.

The largest proportion of government functions were handled jointly for the Settlements and FMS, and separately for each UMS. These functions included public services provided by governments to ensure a minimal level of well-being and provide the necessary infrastructure for economic activity. Thus, health and education, drainage and irrigation, as well as public works were organised this way. Reflecting the economic structure of the FMS, functions associated with agriculture and forestry were managed from Kuala Lumpur, with the rest being supervised from Singapore. Following this logic, management of mines and railways was also undertaken from Kuala Lumpur.

A final group of responsibilities was decentralised to: the Settlements; Federated Malay States; and each Unfederated Malay State. Printing of government decrees and documents; the management of police forces; and immigration were handled in this way. The different economic structures of the Settlements on one hand and the Federated Malay States on the other required different types of labour-power and, consequently, immigration policies. As far as the Unfederated Malay States were concerned, the Sultans wanted to retain control over their immigration policies to preclude large-scale immigration as seen elsewhere on the peninsula.

As can be seen, the state(s) in British Malaya was an asymmetric and overlapping series of organisations that had distinct forms in different parts of the territory. Furthermore, while overall policy for many aspects of public life was decided centrally, in practice the different Settlements and States had varying levels of public spending and, consequently, services. Under British colonial policy, services were provided to the extent a particular territory could afford them.Footnote 42 Revenue levels were, in turn, dependent on factors such as a given territory's physical environment, economic conditions, and political structure and culture.Footnote 43

Table One sets out the average level of revenue per capita for 1935–38 for the Straits Settlements, Federated Malay States, and each of the Unfederated Malay States. Those areas under direct rule, the SS and FMS, had relatively high levels of revenue, approximately SSD 35 per head, reflecting their more lucrative pursuits of trade and export commodity production, respectively. In contrast, the UMS governments had noticeably lower revenue levels, reflecting their subsistence agriculture economies. Thus, the economies of Kedah, Terengganu, and Perlis yielded between SSD 13–17 per head, and of Kelantan a mere SSD 7.50 per head. The outlier of this group was Johor, which was able to generate SSD 31 per capita.

Table 1 Revenue and Expenditure Figures by Territory

Sources: Statistics Department of the SS and FMS, Malayan Year Book (Singapore, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939).

As regards expenditure, the British were committed to fiscal prudence, with spending levels just below revenue levels. Consequently, the pattern across the various territories is the same, with those areas under direct rule having significantly higher levels than their UMS counterparts. Residents of the FMS enjoyed the highest spending levels of SSD 35 per capita, and their Straits Settlements counterparts received some SSD 30 per capita. Barring Johor, the other UMS had less than half the per capita spending levels of their directly ruled counterparts.

Johor's substantial revenue and expenditure levels are explained by its economic structure. The state's tracts of flat, fertile land and proximity to Singapore meant that it had long been a source of commodities such as pepper, gambier, and sugar. However, it was the development of the rubber sector in Johor, coupled with British financial management that allowed the state's revenue base to expand four-fold from 1911 to 1939.Footnote 44 As a result, Johor was far richer and enjoyed higher expenditure levels for longer than did the other UMS.

This economic boom also had ensuing social implications, as coupled with the Sultanate's migration policy, its population grew some 250 percent from 1911 to 1938 and Johor became the most populous Unfederated Malay State. Notwithstanding this, its revenue levels outpaced its population increase, allowing an expansion of social services, with the state coming to have the largest education system in those areas under indirect rule.Footnote 45

These economic differences and ensuing British policies also influenced the size and composition of the various state structures, as they came to house with larger or smaller numbers of British officers, as well as differing proportions of European and local civil servants.

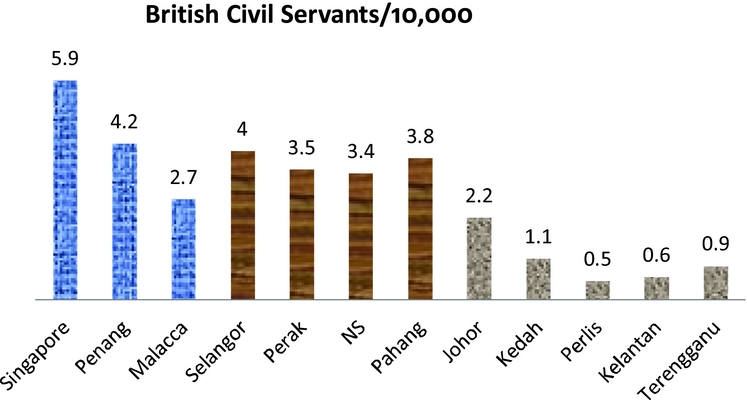

Figure Three displays the ratio of British Civil Servants per 10,000 inhabitants across the various States and Settlements in 1940/1941. As with the revenue and expenditure levels, the differences across those areas under direct and indirect rule is visible, with those in the former category having greater number of British officials involved in administration and daily matters.

Figure 3 Source: Calculated from The Malayan Establishment Staff List as on 1st July, 1941 (Singapore, 1941). These figures refer to: positions, not people and the territory they are ascribed to, rather than physical locations. The ratio for each territory is a composite of: the ratio of British civil servants ascribed to the territory itself; the ratio of British civil servants assigned to administer the respective sub-group of states (SS, FMS, UMS); and the ratio of British civil servants assigned to Malaya.

With regard to the SS, Singapore had the highest ratio of civil servants by far. This is not reflective of the concentration of headquarters in the Settlement, but rather the number of specialist institutions such as museums, colleges, and hospitals. In contrast, Malacca, the smallest Settlement, had the lowest ratio. The various FMS have a relatively similar ratio, with between 3.4 and 4 European civil servants per 10,000 residents. This is also broadly in line with the ratio for Penang, another Straits Settlement.

The UMS had a markedly lower presence of British officials, at around or below one civil servant per 10,000. This is reflective of these states’ relatively under-developed economies, lower revenue levels, and consequently smaller state structures. As before, Johor stands out as the exception, with a ratio more than twice as large – 2.2 British civil servants per 10,000 residents – as the other UMS. However, despite its high income levels, this ratio is not at par with those areas under direct rule, reflecting a qualitative difference in the nature of indirect rule.

The varying extent of British presence in these areas had an effect on the staffing of the different state structures. In the Straits Settlements, the manning of the highest administrative and technical positions was almost exclusively British. Table Two sets out the various ranks of the Malayan Civil Service and their ethnic composition in the Straits Settlements in 1936. As can be seen, a full 100 percent of MCS officials stationed in the SS were British. While people of all races could apply to clerical and mid-ranking positions in the Straits Settlements, the civil service was reserved exclusively for British citizens of European descent. The official reason was that it was important for MCS officials to be deployed everywhere but that the Sultans were reluctant to have non-Europeans seconded to their states.Footnote 46

Table 2 Civil Service Appointments in the Straits Settlements (1936)

Source: Straits Settlements Establishments, 1936 (Singapore, 1936).

Table 3 Civil Service Appointments in Malaya (1941)

Source: The Malayan Establishment Staff List as on 1st July, 1941 (Singapore, 1941).

Leaders from non-European communities in the Settlements began to press for the MCS to be opened to all races. In 1933, the Governor created the Straits Settlements Civil Service for non-Europeans, comprised of certain mid-ranking posts such as Assistant District Officers, Assistant Magistrates, and Registrars. However, unlike the MAS, this service did not offer its members a pathway into the MCS.Footnote 47 Because of this, the scheme was not popular and, of the four positions available in 1936, only three had been occupied.Footnote 48

In the FMS, there was marginally more participation of non-Europeans – specifically Malays – in the top tiers of government. In 1910, the Malayan Administrative Service (MAS) was created in response to calls to open positions of higher responsibility to members of the Malay community from the Federated Malay States. The scheme developed slowly and, in 1929, only eight MAS officers had been incorporated into the Malayan Civil Service.Footnote 49 However, by 1941, there were 20 Malay members of the MCS, albeit in the lower ranks of the hierarchy. Relative to all MCS officers in Malaya, they constituted 11 percent of the total. As a proportion of the MCS stationed in the FMS, Malay MCS officers would have constituted 14 percent of the total.Footnote 50

In both the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States, the participation of non-Europeans lagged in comparison to other parts of the British Empire. In India, the British opened the ranks of the elite Indian Civil Service to Indians after the First World War and, in 1922, candidates were allowed to take the entrance exam in India, rather than London. By 1939, approximately half of the members of the Indian Civil Service were non-Europeans.Footnote 51

The situation in the UMS was very different. Because of the endogenous development of their civil services, and the more limited influence of British control, the upper levels of their governments were more open to Malays than in their federated counterparts.Footnote 52

Even among the UMS, Johor was exceptionally independent and jealous of its sovereignty. Led by entrepreneurial traditional rulers, and fuelled by a well-developed plantation economy, the state was eager to demonstrate a record of enlightened rule.Footnote 53 At the end of the nineteenth century, Johor was able to sustain a large and relatively well-developed local bureaucracy, an army, and a quasi-diplomatic body in London to promote its interests.Footnote 54 In turn, the British were prepared to tolerate this situation as they did not want to intervene in what was initially a desolate and lowly-populated hinterland.

Following its emergence as a populous territory with considerable potential for modern cash crops, British interests changed. While Johor formally came under British influence in 1914, it was able to secure a number of important provisos unique among the UMS. They included stipulations that: only Europeans would be seconded to Johor; seconded officials could be dismissed at the Sultan's discretion; Malay and English would be the languages of government and all civil servants would be treated equally; and disagreements between the British-appointed Adviser and the Sultan would bypass Kuala Lumpur and be referred directly to the Governor in Singapore.Footnote 55

This gave rise to a low-level battle for influence between the Sultan and the British-appointed General Advisor over the next three decades. In seeking to establish control over the state apparatus, the British sought to secure key administrative positions and control recruitment into the civil service.

Thus, the British sought to, and obtained consent to, bring in, a steadily increasing number of European civil servants in administrative and technical capacities. In 1915, there were seven British officials in Johor and this number had increased to more than 160 by 1940.Footnote 56 However, while control over the top positions in departments such as Education, Health, and Public Works was gradually ceded to the British, the apex governmental organisations of the Sultan's Office, Chief Minister's Office, State Secretariat, religious department, and army remained under the control of the Sultan for the entire period.Footnote 57

The British also split the government into two services, administrative and clerical. Recruitment and promotions in the administrative service were formally the Sultan's prerogative, and the British secured control over the clerical division under the guise of needing to secure clerks with requisite linguistic competencies. Following this, the British then created a corresponding scheme for administrative staff, the Malay Officers Scheme (MOS). Entry into this corps was then restricted to graduates from the clerical scheme, which the British controlled. Notwithstanding this, the overwhelming majority of recruits into the MOS had kinship links to the Sultan, the existing bureaucratic elite, or the religious hierarchy.Footnote 58

The end-result was a large well-trained local administrative elite with close ties to the Sultan at all levels of the state government. Table Four sets out the number of Malayan Civil Service officers serving in Johor in 1940, alongside their Malay Officer Scheme counterparts. In contrast to the FMS and SS, where more than 90 percent of the highest administrative positions were occupied by British officials, the proportions are reversed in Johor. In this case, there were more than 150 local members of the MOS and only 16 British MCS officers in Johor. Furthermore, unlike in the FMS, where almost all members of the Malay Administrative Service were concentrated in the lower echelons of the bureaucracy, the members of the MOS were found right across the spectrum, including the positions of: Chief Minister [Mentri Besar]; State Secretary; and State Treasurer.Footnote 59

Table 4 Administrative Service Appointments in Johor (1940)

Source: Johore, List of Establishments 1940 (Johore Bahru, 1940).

From a distance, the various state structures of British Malaya may have resembled each other, as they were organised similarly and implemented similar policies. However, direct and indirect rule translated into very different realities on the ground. Direct rule as it was practiced in Malaya entailed the construction of legal-rational state structures staffed with highly-trained officials. However, the composition of these state organisations, particularly at their apex, was almost entirely European. Despite requests to allow non-Europeans to assume positions of responsibility, the number of Malays in the FMS and non-Europeans in the SS in higher level civil-service positions was negligible. Relative to other parts of the British Emprise, progress in this regard lagged very significantly. The situation in areas under indirect rule was very different, as Malays occupied apex positions to a much greater degree. The analysis of Johor, in particular, shows that Malay civil servants attained and retained the highest administrative positions in the state.

The Japanese Occupation and Its Impact on Malaya's State Structures (1942–1945)

In spite of being a short interregnum in the British rule of Malaya, the Japanese Occupation was to have far-reaching political and social effects. During the three and half years it lasted, the machinery of government was completely restructured, inter-ethnic relations changed dramatically, and the territory's relationship with its erstwhile colonisers transformed. Although they would not immediately realise it, the British were to return to a dramatically different reality.

Due to the realities of war, limited available personnel and the objective of winning the support of the local population, the Japanese policy with regard to administering Malaya was that “existing government organisations shall be utilised as much as possible, with due respect for past organisation structure and native practices”.Footnote 60 While this was pursued to a certain extent, very important changes were made to the composition and structure of Malaya's governments, which exposed the underlying differences between direct and indirect rule.

After the fall of Singapore on February 15th, 1942, the Japanese 25th Army established the Malayan Military Administration on March 2nd, 1942. Responsible for Sumatra, Malaya, and Singapore, it had its headquarters in the latter.Footnote 61 The structure of the Administration, unlike its British pre-war counterpart, was very centralised. Under the supervision of the Director-General, there were a number of functional bureaux (Finance, Industry, and Transport inter alia), each responsible for all of Malaya and Singapore. Beneath this central structure, were the various States and Settlements, which were made co-equal. Thus, the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States were disbanded, with their component units made into separate provinces or, in the case of Singapore, a municipality. In October 1943, the provinces of Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah and Perlis were transferred to Thailand.Footnote 62

Regarding the inhabitants of Occupied Malaya, the Japanese implemented a multi-facetted approach to the various ethnic communities. First, they aimed to “liberate” Malaya from its colonial past by eradicating, as much as possible, British influence. The Malays, for their part, were cultivated as allies, as the Japanese wanted them to be the “principal racial group” in the territory. Indians were also approached as potential partners for the Japanese campaign against the British in India. In contrast, Japanese policy towards the Chinese was initially punitive, due to support from the diaspora against its rule in Manchuria. However, policies towards the Chinese softened from mid-1943 onwards.Footnote 63

Regarding recruitment and staffing, the Japanese issued edicts requiring all civil servants to register and those in vital services to return to work.Footnote 64 However, this did not apply to European civilians from Allied nations, who were all to be interned. Between 80–90 percent of all MCS officers were kept at Changi as either prisoners or detainees.Footnote 65 This had a differing impact across British Malaya, as the bureaucracies of the states and settlements were staffed by European civil servants to varying degrees.

Penang, a Straits Settlement, was essentially left without a government, as the entirety of its European population was evacuated prior to the arrival of the Japanese. The only representatives of the government remaining were three non-European civil servants prevented from evacuating.Footnote 66 The implications in Singapore were similar, with the sole exception that, as its civil servants were not evacuated, a more orderly hand-over of functions took place.Footnote 67

The situation in the Federated Malay States was comparable, as their government structures were similarly dependent on British civil servants. For the first few months, the Japanese placed an emphasis on maintaining law and order as well as restoring basic public amenities.Footnote 68 From about mid-1942, civil servants were brought in from Korea, Taiwan, and Manchuria to staff central and provincial governments.Footnote 69 Evidence from Selangor, the centre of the FMS, indicates that local civilians were re-hired and government organisations restructured only from late May onwards.Footnote 70 Advisory Councils were created in the various provinces towards the end of 1943.Footnote 71

The situation in Johor was markedly different. First, the departure of the British had a numerically negligible effect, as only 10 percent of the state's apex positions were held by Europeans. Second, the ethnic composition of the Johor government was compatible with Japanese policy, which was to provide favoured treatment for Malays with regards to promotion and training opportunities.Footnote 72 Therefore, unlike in the SS and FMS where the administrative core of the state had to be reconstructed, the Japanese had an existing structure to work with in Johor.

Relative to elsewhere in the peninsula, work restructuring the Johor government proceeded much more rapidly. A Consultative Council was established within the first two weeks of the Occupation. Its salaried members were the most-senior political and administrative personalities in the state, including the Chief Minister, Deputy Chief Minister, and State Secretary.Footnote 73 This pre-dated the establishment of Advisory Councils by some 18 months, and was a departure from the standard practice of simply eliminating the position of Mentri Besar. Thus, from the beginning, the Japanese had access to the highest level civil servants, which they could utilise to restructure the government in line with their needs.

The first re-deployments of local Johor government officers began on the 16th of February, the day after the fall of Singapore. By the end of March, a full two-thirds of all government departments had been restructured, including Police, Prisons, and Health, as well as newly-created departments such as General Affairs, Propaganda, and Food Control. By the end of April, the restructuring was essentially complete – more than a month before it began elsewhere in Malaya.

The Japanese also sought to decrease the overall size of the state for budgetary reasons, and to free up labour-power to grow food. Salaries were reduced on a sliding scale, and a new administrative hierarchy was introduced.Footnote 74 Thus, the Johor government's headcount was reduced by one third and its personnel budget cut by more than 50 percent. However, the nucleus of the pre-war state, and particularly the Malay Officers’ Scheme was essentially left intact – with 90 percent of its members in 1940 traceable in 1943, at the height of the Japanese occupation.Footnote 75 While the MOS itself was superseded by the new Japanese staffing hierarchy, due to their knowledge of administrative procedures as well as their command of Malay and English, these cadres were natural choices for senior administrative positions. Indeed, despite official invectives to conduct the business of government in Japanese, the majority of government correspondence was still in English and Malay.Footnote 76

Table Five depicts the departments with the highest number of MOS officials before and during the war. As can be seen, the MOS were present in all key government agencies and were, in effect, still occupying senior roles from Customs to District Offices, and from Finance to Policy. While some departments such as the State Secretariat were eliminated, personnel from these administrative positions were deployed elsewhere. The Secretary of State became a member of the Consultative Council, and the Deputy State Secretary became the Officer-in-Charge of the General Affairs Bureau – the Japanese functional equivalent.

Table 5 MOS Officials by Department (Top Ten)

Sources: Johore, List of Establishments 1940; Johore, Establishment Lists 2603.

Thus, the Japanese Occupation was an intense and traumatic juncture for the Malayan state(s) and society. For the first time, the territory operated under a centralised and uniform political and functional structure. Collective entities such as the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States were undone, and all provinces subsumed under a central authority.

In addition to this large-scale restructuring, the Japanese Occupation and, in particular, its policy to intern all European civilians from Allied nations uncovered the differing composition of the various state structures in Malaya. In areas under direct rule, the apex level of the various state structures had to be rebuilt, due to their essentially British composition. In contrast, in Johor, the essentially Malay nature of its bureaucracy and Japanese policies meant that the highest administrative cadres survived largely intact.

Johor as a Breeding Ground for Leaders in the Post-war Period

After the Second World War, the British returned to a changed political reality. Their initial defeat led to a loss of prestige, permanently changing their relationship with the territory's local inhabitants. In addition, Japanese policy had fostered ethno-nationalism, through: encouraging political activity among the Malays; providing positions of greater responsibility to locals in government; and by altering the relationships between the various ethnic groups.Footnote 77

These underlying changes were accentuated by British policies in the first months following their return. Disillusioned with what they perceived as collaboration between the Malay elite and the Japanese and wanting to incorporate Malaya's other communities, the British temporarily abandoned their “pro-Malay” policy. Furthermore, they wanted to seize the opportunity to rationalise the various governance structures in existence. This was for efficiency's sake as well as to create an effective state able to re-start the economy and prepare for the transition to independence.Footnote 78

The Malayan Union, a unitary government for all Malaya minus Singapore, was to be the new governing structure for the territory. The various states and settlements were to be brought under one central government under the British Crown – as opposed to the authority of the sultans. While the sultanates would still exist, the formal authority of the sultans and the various state and settlement governments would be in name only. All power and responsibility at the state level would shift to a federal government centred in Kuala Lumpur, and the civil service would be open to members of all races. This was also to be accompanied by liberal citizenship laws that incorporated the country's Chinese and Indians on equal terms with the Malays.Footnote 79

The British sought, and obtained, consent from the sultans for this legal change in the last quarter of 1945. Hammered out in secret, these negotiations were not without a considerable dose of coercion, as the envoy, Harold MacMichael, was also charged with evaluating the degree of collaboration of each sultan with the Japanese.Footnote 80

Local opposition to the Union began to build in late 1945 and gathered steam when the details were made public the following January. Two aspects were particularly contentious – that Malay public opinion was not consulted, and the British did not envisage any modifications to the policy. Footnote 81

The declaration of the Union resulted in the first visible manifestation of Malay ethno-nationalism. Fearing the loss of their status as the indigenous inhabitants of the country, the Union was stridently opposed by the Malays. This was exacerbated by a new political climate where restrictions on the establishment of societies and unions were relaxed and censorship of the press was rolled back, as the British sought to encourage a moderate form of nationalism with the aim of fostering a new, multi-ethnic national identity.Footnote 82

In the first period of opposition to the Malayan Union, a large number of Malay groups were established or revived. By February 1946, there were some 44 Malay associations, of which 30 were explicitly political.Footnote 83 Beyond their opposition to the Malayan Union, these groups spanned the political spectrum, ranging from state-based associations led by the Malay elite to pan-Malayan movements of a more anti-colonial and ethno-nationalist bent, such as the Malayan Nationalist Party.Footnote 84

However, the Malay aristocracy had emerged strengthened, in relative terms, from the Japanese Occupation.Footnote 85 The greater career and training opportunities available during the Occupation, as well as their work in front-line positions in government, had put them in much closer contact with rural Malays.Footnote 86 Thus, this group was the best equipped to step into the vacuum of leadership created by the sultans, whose dependence on external recognition had been exposed during the Japanese Occupation and their subsequent capitulation to British demands.Footnote 87

It was in this context that Johor provided the most favourable seed-bed for leaders to emerge. Relative to the FMS, whose state structures were largely staffed by British officers before the war and only had a small number of senior Malay public servants, Johor's bureaucracy had survived the war relatively intact and had an important number of experienced Malay administrators.

Furthermore, unlike the FMS, where the local aristocracy owed their rise within the federal government machinery to the British, the elite from the Unfederated Malay States now had the most to lose from the proposed Union. Onn Jaafar, who became Chief Minister of Johor in 1946, resented the implications of the Union, which would reduce his position to that of a “records officer with no executive power”.Footnote 88

The other UMS also emerged from the war with relatively intact state structures, which had been preserved to a large extent under Thai rule. However, their smaller size yielded a smaller pool of potential leaders. In 1947, Johor had some 740,000 inhabitants, versus Kedah and Kelantan's 550,000 and 450,000, respectively. Its proactive education policies also yielded a more literate population than elsewhere in the UMS.Footnote 89 And, its higher income levels had also allowed the development of a larger civil service. In 1947, Johor had some 3,250 people employed in government, almost twice the number as Kedah (1,700), and significantly more than the other three UMS.Footnote 90

Table Six depicts the career trajectories of 17 senior UMNO members from Johor (either Supreme Council members and/or senior parliamentarians) in the pre-war period, through the Japanese Occupation, and then in the immediate post-war period. Several patterns emerge. First, the majority of these figures (13) were public servants employed in the Johor Government before or during the war. Second, of the public servants, a majority (8) were members of the Malay Officers’ Scheme who occupied senior administrative positions in the Johor government. Third, the entire pre-war cohort of civil servants remained in the government through the war, even absorbing two additional recruits.Footnote 91 As argued above, the MOS remained the nerve centre for the government under the Japanese, despite extensive restructuring.

Table 6 Career Trajectories of Senior UMNO Figures (1946–56) from Johor

Sources: The list of names is compiled from Funston, Malay Politics (UMNO National Executive/Supreme Council members) and Times of Malaya, 5 August 1955 (Cabinet Members). Political and administrative details are from: Stockwell, British Policy and Malay Politics; Manderson, Women, Politics, and Change; Funston, Malay Politics; Johore, List of Establishments 1940; Johore, Establishment Lists 2603; Arriful Ahmadi, Wira Bangsa Dalam Kenangan; Ooi, The Reluctant Politician, and J.V. Morais, The Who's Who in Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur, 1963).

In the promising political context that post-war Johor provided, this core of senior administrative figures was well-placed to assume leadership positions. This was not a linear process, as the political situation in the Malay community was fractious in late 1945 and early 1946. However, this cohort established itself at the head of various state-based associations that were influential in the months preceding the founding of UMNO.

Thus, members of this group founded or led three important grassroots political organisations: Onn Jaafar, Mohd Noah Omar, and Hussein Onn were the founders of the Peninsular Malay Movement, Johore; Abdul Rahman Yassin, Suleiman Abdul Rahman, Hassan Yunos, and Khadijah Sidek were leaders of the Johore Malay Union; and Sardon Jubir was President of the Singapore Malay Union.

Onn Jaafar, a well-known journalist and member of the Johor aristocracy, earned a reputation as a fair and able administrator during the war in his capacities as Food Controller and, subsequently, District Officer. In January 1946, he founded the Peninsular Malay Movement, Johore [Pergerakan Melayu Semenanjong, Johore] and within two months had a large membership in urban areas across Johor and in Malacca. First as District Officer and then as Mentri Besar, he used his office and support staff to carry out his political activities.Footnote 92

Concurrently, a group of senior civil servants leading the Johore Malay Union [Persatuan Melayu Johore] organised a protest and called for the removal of the Sultan of Johor. Led by Abdul Rahman Yassin, a long-standing Johor civil servant, the Union argued that the Sultan, in agreeing to the Malayan Union, had violated the territory's constitution, which expressly forbade its ruler from ceding any part of the state to a foreign power. The Sultan later retracted his support for the Malayan Union, and public debate then focused on opposing the Union itself. While the Johore Malay Union did not become an UMNO affiliate, several of its leaders joined UMNO in its early days – notably Abdul Rahman who became the party's treasurer. However his sons, Suleiman and Ismail, did not join UMNO until 1951.Footnote 93

Sardon Jubir, for his part, spent the immediate post-war period in Singapore, where, in March 1946, he was elected to the Executive Council of the Singapore Malay Union. The Singapore Malayan Union then became one of UMNO's affiliate members and nominated Sardon for the UMNO Executive Council. Sardon was subsequently President of the Singapore Malay Union from 1947–51, after which he moved back to Johor.Footnote 94

In addition to these three “feeder” associations, Johor civil servants were also active in other organisations. Only the second Malay woman to attend an English school, Zain Suleiman founded the first Malay women's association in Malaya in Johor in 1929. A Superintendent of Girls’ Schools in the Johor Department of Education prior to the war, she continued to work in the Department during the Japanese Occupation. While her association was disbanded by the Japanese, she ran an informal women's group throughout the war. In the post-war period, Zain was involved in literacy and empowerment campaigns for women in Johor.Footnote 95

Another group of Johor civil servants founded the Board of Malay Unity, Johore [Lembaga Kesatuan Melayu Johore]. Haji Mohd Taib and his son Abdullah were well-known MOS officials; and Taib's other son, Hamzah, had been an assistant medical officer with the Johor government in the pre-war period.Footnote 96 Lembaga was a founding UMNO affiliate, however their more radical tendencies resulted in them leaving UMNO to join the left-wing Malay Nationalist Party in 1947.Footnote 97

In the early part of 1946, Onn Jaafar emerged as the most viable leader for the Malays at the national level. This was, in part, due to his charisma, his vision in making an early call for a pan-state organisation for Malays, as well as his effective campaigning.Footnote 98 In addition to travelling extensively, he used local leaders such as village headmen and school teachers to set up grass-roots organisations. His own organisation grew rapidly, reaching an estimated 125,000 by March 1946.Footnote 99

In March and May 1946, Onn, along with other Malay leaders, organised two conferences in order to: establish a national organisation to promote Malay rights; and plan their response to the Malayan Union. At the second congress in May, UMNO was created as an umbrella organisation that brought together 41 Malay Associations with Onn as President and its headquarters in Johor Bahru.Footnote 100

Onn's leadership of the Peninsular Malay Movement, Johore, with its large membership base was vital in cementing the state as a key centre of the party. As UMNO President, Onn surrounded himself with members of the English-educated elite, particularly senior bureaucrats and members of the aristocracy.Footnote 101 Onn's approach, which was shared by his “inner circle”, was not aggressively anti-colonial. Rather, beyond repealing the Malayan Union, he sought to widen educational opportunities for Malays and gradually move towards independence.Footnote 102 Over time, the more radical and left-leaning organisations began to leave UMNO, reinforcing its conservative outlook.

However, it is also important to note that the various groups from Johor were not united. There had been serious differences between Onn and the Johor Malay Union over the deposition of the Sultan of Johor.Footnote 103 There were also differences over the approach to negotiations with the British between Onn and Sardon Jubir, and between Sardon Jubir and Hussein Onn over the leadership of UMNO Youth.Footnote 104 And, despite Zain Suleiman's impeccable track record in promoting women's rights, Onn initially supported a leader from Perak to assume the leadership of the Women's Wing.Footnote 105 In addition, the members of Lembaga were particularly harsh critics of Onn, subsequently leaving the party.Footnote 106 Rather, it was the crucial mass of public servants with administrative experience that allowed Johor to dominate the party during its first decade – regardless of their internal disagreements.

Following UMNO's establishment and success in persuading the sultans to boycott the inauguration of the Malayan Union, the British agreed to consider alternative governance arrangements for the territory. Scared by the more left-wing and nationalistic groups active at that time, the British appointed UMNO as the representative of the Malays in the Working Committee to determine the country's new governance structure, and eventually established the Federation of Malaya in 1948.Footnote 107 This cemented the fledgling party's reputation and helped ensure its survival in the new political context.Footnote 108

During this period, Kedah could have rivalled Johor for influence within UMNO. While considerably less wealthy and possessing a smaller civil service, the state had emerged relatively unscathed from the Japanese occupation and, like Johor, had a tradition of fierce independence. However, beyond its smaller pool of potential leaders, the state's influence at the highest levels of UMNO in the 1940s was further mitigated due to political reasons.Footnote 109 It was only upon Onn's resignation from UMNO in 1951 and the appointment of Tunku Abdul Rahman as its President that this began to change. However, the influence of Johor continued to loom large. The UMNO's headquarters remained in Johore Bahru until 1955, and the Tunku's initial success at helming the party was due to the support of the Johor-based Malay Graduates Association, which drew its members from the Johore Malay Union and joined UMNO only after the departure of Onn.Footnote 110

Over the 1946–57 period, the British worked hard to create a powerful central government, overseeing the transfer of personnel and key government functions such as health and education from the state to the federal government. In parallel, they trained substantial numbers of Malays as senior administrators. The size of the government also grew almost three-fold in an effort to combat a communist insurgency.Footnote 111 The British organised a series of local, state, and ultimately national elections before independence, in order to select the country's eventual leaders as well as inculcate familiarity with election processes.

Thus, the British did follow many of the tenets of direct rule in the run-up to independence, tilting Malaysia's legacy more towards direct than indirect rule. However, for a crucial and finite period of time, Johor, due to its population base, large well-developed education system and, most importantly, intact civil service meant that it had a range of experienced administrators that were able to assume leadership roles in the Malay community in the immediate post-war period.

Conclusion

Recent comparative historical work has argued persuasively that areas under British direct rule have had better long-term developmental outcomes. This model of colonisation entailed the creation of a large, rules-based state structure staffed by meritocratically-recruited and -trained administrators that extended their control to all parts of the national territory. This “institutional legacy” then enabled the country's leaders to pursue developmental goals in the post-independence period. Conversely, those countries that were colonised indirectly inherited weaker, more patrimonial and, hence, less capable states. This legacy then translated into less positive post-independence developmental outcomes.

This article has scrutinised the size and composition of the various state structures in Malaya, which encompassed territories that were ruled directly and indirectly. In so doing, it has shed light on one of the contradictions of direct rule. At least as far as Malaya was concerned, those territories that were ruled directly – the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay State – did have large, capable, and meritocratic state structures. However, the composition of their bureaucracies was overwhelmingly British, leaving scarce room for local civil servants to acquire administrative skills and experience. In contrast, those areas under indirect rule had states that were, to a much larger extent, run by local elites. In the case of Johor, the largest and richest territory under indirect rule, more than 90 percent of its apex administrative positions were held by locals.

This finding therefore calls for questions of leadership to be explored more fully, particularly as countries transition to independence. While direct rule may have been better at developing structures and processes, because of its reliance on British officials, it appears to have “crowded out” potential local leaders. This paradox was made evident through the Japanese occupation, which stripped off the layer of British control, thus exposing the layer of underlying local bureaucracies.

Through studying the contours of the Malayan state(s) in the pre-war period in greater depth, this article has shed light on some of these dynamics. From today's perspective, state construction efforts undertaken by the British in post-war Malaya loom large. In particular, the further opening of the Malayan Civil Service to locals and the subsequent Malayanisation campaign left the newly-independent country with a large, powerful federal government, and a generation of senior bureaucrats that had been trained by the British. However, many of the country's leaders, who were also bureaucrats, had emerged a decade earlier, in the crucial 1946–48 period, when the future of the country and its government system were under debate. In this particular period, it was those areas under indirect rule that provided the critical mass of local senior administrators that had the skills to lead and the incentives to fight to preserve their prerogatives.