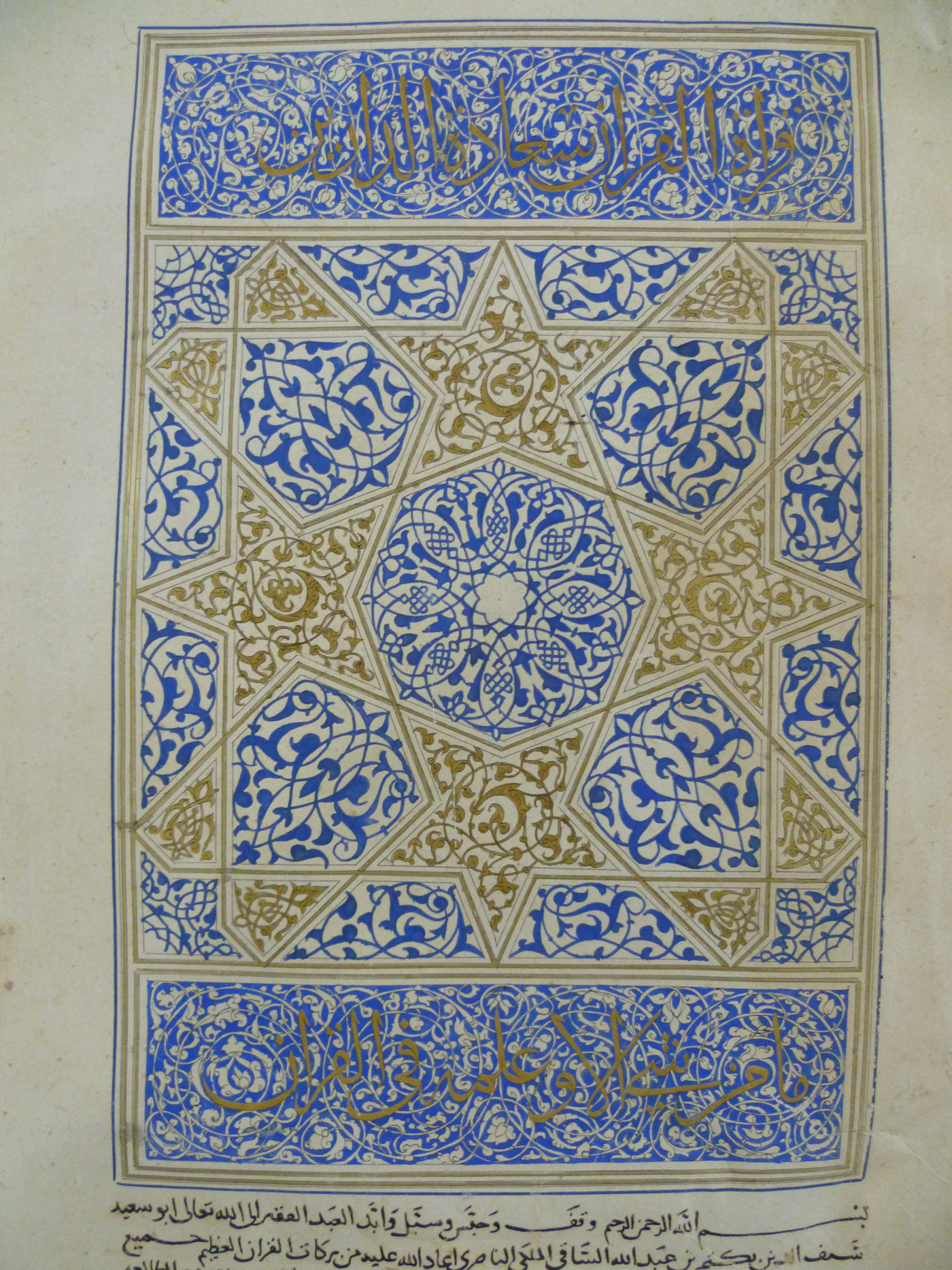

The Hamadan Qur'an copied for the Ilkhanid Sultan Öljaytü (1304–1316) in the Dar al-Kutub in Cairo is well-known for its exquisite illumination distinguished by a distinct palette of blue, gold, black, and white; masterful calligraphy; and large burnished sheets of fine paper (Figure 1).Footnote 2

Figure 1. DAK Rasid 72, Juz’ 2, fol. 2a.

The illumination of the Hamadan Qur'an has been discussed in several publications, most extensively by David James in his seminal work on the illumination of Qur'ans of the Bahri Mamluk period (1250–1382). However, its bindings have not received the same attention.Footnote 3 Ettinghausen published a rubbing of the roundel from the flap of one of the volumes of the Hamadan Qur'an in 1954, but since then the bindings of the 30 volumes (juz’, singular; ajzā, plural) of this remarkable Qur'an, along with the bindings of other Ilkhanid manuscripts, have attracted little scholarly attention.Footnote 4 This article aims to discuss the bindings of this manuscript and explore its relationship with contemporary Mamluk and Ilkhanid examples.

The Hamadan Qur'an is generally associated with three other Qur'an manuscripts that form an important group of Ilkhanid imperial commissions. The first is known as the ‘Anonymous Baghdad Qur'an’ because there is no commissioning certificate indicating the identity of the patron. David James speculated that it may have been commissioned by the Ilkhanid vizier Rashid al-Din (1247–1318), or for the Ilkhanid sultan Ghazan Khan (1271–1304).Footnote 5 It was copied by Ahmed ibn Al-Suhrawardi al-Bakri and illuminated by Ibn Aybak. Al-Suhrawardi was one of the pupils of Yaqut al-Mustasimi (d. 1298), responsible for categorising the six scripts and, according to Qadi Ahmed, the seventeenth-century chronicler of painters, for most of the texts inscribed on the buildings of Baghdad, although none have survived.Footnote 6

The second, now known as the Baghdad Qur'an, was copied in Baghdad between 1306–1311Footnote 7 for Öljaytü's funerary complex in his new capital at Sultaniyya, begun in 1305 and completed in 1314.Footnote 8 The scribe is generally believed to be Ahmed ibn al-Suhrawardi al-Bakri as he only signs himself as ‘the poor slave in need of God's mercy’, and the illuminator was Ibn Aybak, who signed his name in Juz’ 7.Footnote 9 The third was copied in Mosul, commissioned in 1306, and completed in 1311 for Öljaytü. The colophons at the end of each volume provide the name of the scribe ‘Ali ibn Muhammad ibn Zayd Al-Husayni who was most probably also the illuminator. However, there is no indication in the manuscript that this was destined for the mausoleum at Sultaniyya.Footnote 10

These manuscripts were the productions of workshops that were initially founded during the reign of Öljaytü's brother Ghazan Khan at Baghdad and Tabriz; later Öljaytü established others at Sultaniyya, Hamadan, and Yazd.Footnote 11 However, many of the 30 volumes of the ‘Anonymous Baghdad’, Baghdad, and Mosul Qur'ans are now dispersed between collections in Iran, London, New York, Istanbul, Dresden, and Copenhagen, often with folios bound together haphazardly and placed within new bindings, having suffered troubled existences. Given that the Hamadan Qur'an remains complete and relatively unscathed, it offers a unique insight into understanding aspects of manuscript production during the Ilkhanid period.Footnote 12

The Hamadan Qur'an was copied in rayḥan, a smaller version of the muḥaqqaq script which was used for the other imperial commissions, in black, gold, and blue ink in Jumādā I 713/September 1313 by cAbdallah bin Muhammad bin Mahmud al-Hamadhani. We know little of Hamadhani other than that he must have been employed in the scriptorium that had been established by Rashid al-Din, as the colophon states that he worked in the Dār al-Khayrāt al-Rashīdiyya in Hamadan (Figure 2).

Figure 2. DAK Rasid 72, Juz’ 30, fol. 42b.

Translation of the colophon:

This Qur'an was written and illuminated in conformity with the one who propagandises for his kingdom from the bottom of his heart, with complete sincerity who aspires for the indulgence of the Eternal, the meanest of slaves, cAbdallāh bin Muḥammad bin Maḥmūd al-Ḥamadhānī, may God forgive him, in Jumādā 1 713 of the Hijrah of the Prophet, blessings be upon him, in Dār al-Khayrāt al-Rashīdiyya in Hamadan, may God protect it from harm. Footnote 13

Another Qur'an of 30 parts, now in the King ‘Abdul Aziz Library in Medina, is also signed by him with a completion date of 1310 and has the same style of illumination, with frontispieces in various geometrical designs in the same palette of blue, gold, and black at the beginning of each juz’.Footnote 14

Nothing is known of the history of the manuscript between its date of completion in 1313 and its subsequent arrival in Cairo when it was bequeathed in 1326 to the newly founded khānqāh of Amir Sayf al-Din Baktamur who was a brother-in-law of Sultan Nasir Muhammad (first reign 1293–1294, second reign 1299–1309, third reign 1310–1314) and the atābak al-jaysh (Commander-in-Chief) (Figure 3).Footnote 15

Figure 3. DAK Rasid 72, Juz’ 10, fol. 1b-2a.

On that occasion, a waqf (endowment) inscription was added in the name of Amir Sayf al-Din Baktamur to all the volumes (Figure 3), and the name of Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad replaced that of Öljaytü in the original certificate of commissioning, suggesting that the manuscript was first in possession of the Sultan and then presented to his son-in-law, Sayf al-Din Baktamur, as a gift on the foundation of his khānqāh.

Michael Rogers suggested that it was taken out of Iran during the negotiations between the Ilkhanids and Mamluks before 1326, and David James put forward that it might have been sent as a gift from the Ilkhanid Sultan Abu Sa'id (1305–1335) to the Mamluk Sultan in the course of the peace negotiations of 1324.Footnote 16 We know, however, that it must have been valued and admired in Cairo as Ibn Iyas records its removal to the complex of Sultan Al-Ghuri (r. 1501–1516) on its completion in late 1504 along with sacred relics of the Prophet and the Qur'an of Uthman. He also mentions in his account that Baktamur acquired the Qur'an for a thousand dinars, suggesting that Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad may have sold it to Baktamur.Footnote 17 The volumes in the Dar al-Kutub record their entry into the Khedival Library, which later became the National Library of Egypt, on 3 April 1880.

Each of the volumes opens with two pages of illumination with a geometrical design in the cool, stark colours of cobalt blue, ultramarine, turquoise, white, and black (Figure 4). The panels appear as if they are floating on the page but the addition of the waqf to Baktamur's khānqāh inserted below the panel on the first page of each volume unsettles the intended effect. On some of the frontispieces, verses from the Qur'an or sayings are placed in the upper and lower panels while others are left plain (Figure 4). For example, the upper and lower panels of the opening page (fol. 1b) from Juz' 25 says: ‘Reading the Qur'an brings happiness in the two abodes here and the hereafter as there is only knowledge in the Qur'an’.

Figure 4. DAK Rasid 72, Juz’ 25, fol. 1b.

The stark nature of the text pages is characterised by the absence of verse (āyah) markers. It is copied with five lines to a page in rayḥan script set within a panel which was added after the copying of the text.

However, on close examination, it is curious that the illumination of several sūrah headings appears unfinished throughout the volumes, and in some cases the letters have only been outlined, standing in striking contrast to others within the same volume that have been completed (Figure 5).

Figure 5. DAK Rasid 72, Juz’ 28, fol. 37a.

It is also surprising that this remained unnoticed as the Qur'an was certainly corrected after copying, as in this example from Juz’ 3 where the calligrapher has mistakenly repeated lines of verse 261 of Sūrah al-Baqarah (Figure 6) and they have been crossed out.

Figure 6. DAK Rasid 72, Juz’ 3, fol. 16b.

Also, in the final juz’, several additions have been made to the illumination in a Mamluk style, including bright red backgrounds and the use of red combined with gold scrollwork, entirely out of keeping with the palette of the manuscript and most likely added in Cairo (Figure 7).

Figure 7. DAK Rasid 72, Juz’ 30, fol. 19a.

However, it seems this was not the only manuscript commissioned by Öljaytü to be left unfinished. Boris Liebrenz has pointed out that certain folios of what was once part of the Baghdad Qur'an of Öljaytü, commissioned in 1307 and exhibited in his funerary complex in Sultaniyya, now in the Royal Library in Copenhagen (two leaves) and the Sächsische Staats-und Landesbibliothek in Dresden, were left unfinished and were not completed sequentially.Footnote 18 Liebrenz notes that the Dresden volume is only fully executed until folio 16 after which the illumination is discontinued, while the script at the end of the Dresden volume is incomplete, with only its outlines drawn.Footnote 19 In addition, Liebrenz points to the non-linear approach to the work, as Juz’ 28 remains unfinished while Juz’ 29 is complete. James also alludes to this in his discussion of the completion dates of various juz’ of the Mosul Qur'an whereby Juz’ 1–Juz’ 15 were completed in one year in 1307, but the copying of Juz’ 16 commenced three years later in 1310.Footnote 20 Likewise, Sheila Blair, in her article on the Maragha Qur'an written between 1338 and 1339, has also shown that the illumination was unfinished and that the volumes of the Qur'an were not decorated sequentially.Footnote 21 In the Hamadan Qur'an, the only parts of the manuscript that can be considered complete are the text, illuminated frontispieces, the certificates of commissioning, and the colophons. In seeking explanations for this haphazard approach, one can only surmise that although Hamadhani is named in the colophon as having both written and illuminated it, many of the tasks may have been carried out by a team who were not overseen in an organised fashion.Footnote 22 Also, as the colophons were obscured during the Mamluk period and only Juz’ 30 has been uncovered, we cannot ascertain if there are individual dates of completion for each juz’.

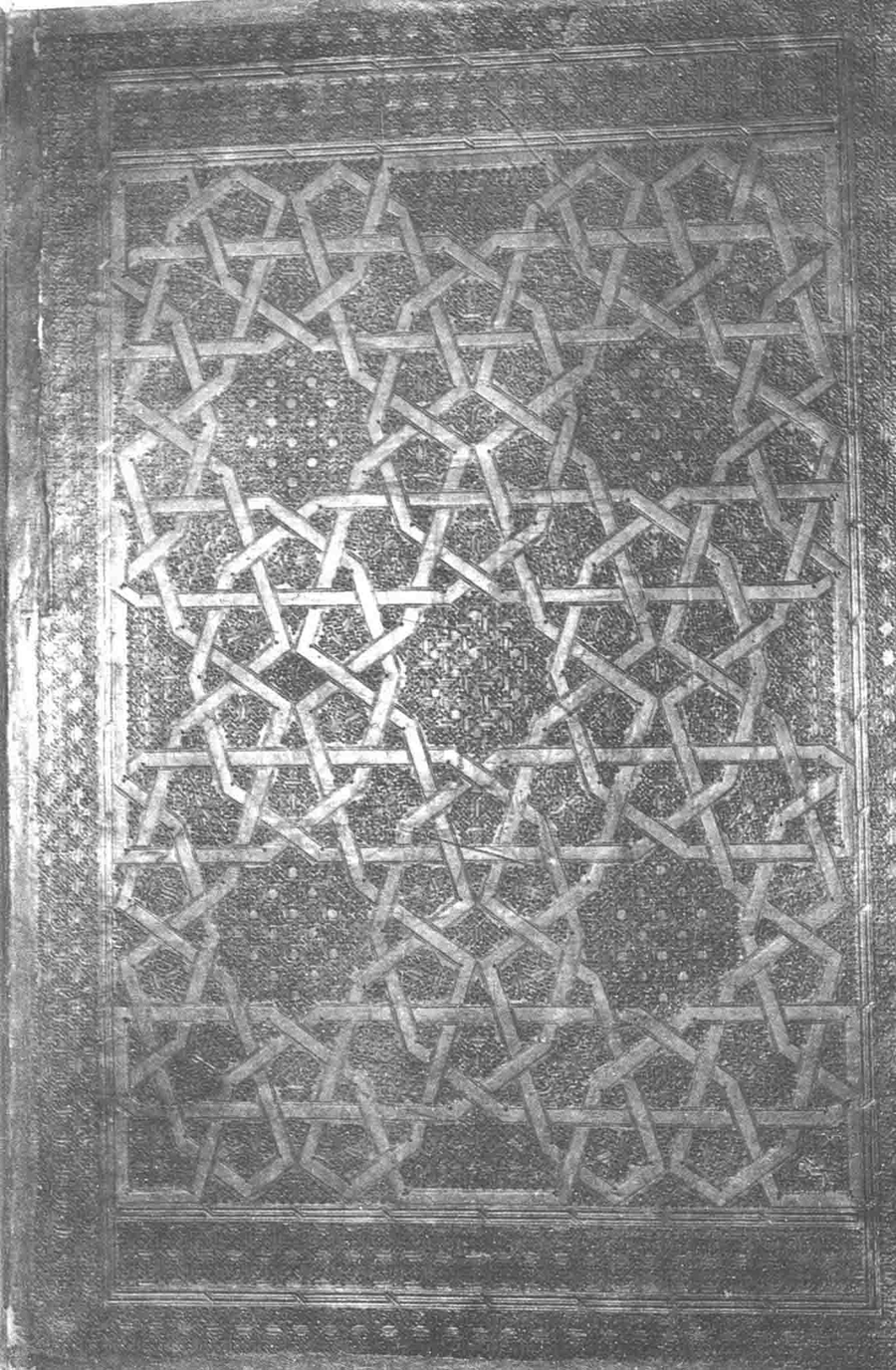

However, in the light of these anomalies outlined in the discussion above, the questions arise of why the volumes were bound unfinished and whether they were bound before or after their arrival in Cairo. This question was also addressed by Richard Ettinghausen and Basil Gray but not for the reasons outlined above. Ettinghausen rejected the possibility of an Egyptian origin because ‘Egyptian bindings would show more complex design and dazzling execution’ and Gray because ‘it is inconceivable that such great books should have travelled to Egypt unbound or required rebinding soon after their arrival’ (Figure 8).Footnote 23

Figure 8. DAK Rasid 72, lower cover, Juz’ 2, 56 x 41 cm.

The binding of each juz’ is decorated in exactly the same manner, which very probably indicates they were all bound at the same time and by the same binder. Each volume is provided with the same block-pressed leather doublures with floral leafy designs. The upper and lower covers are tooled with a central roundel with a ten-pointed star at the centre of which is a ten-petalled rosette whose arms interweave with a decagon (Figure 9).

Figure 9. DAK Rasid 72, detail of the cover.

The polygonal cells created by the geometrical pattern in the central roundel are tooled with small five-armed swastikas with green punches at their centres and gilt ones marking the design. The narrow borders of the central panel are decorated with a cable pattern with gilt punches at the corners, and knotted projections extend into the central field from the upper and lower borders. The roundel is repeated on the flap, but in this case, an eight-pointed star is used in conjunction with an octagon set within a medallion (Figure 10).

Figure 10. DAK Rasid 72, Detail of flap of Juz’ 2.

The first points of interest are the green punches of what may be small leather onlays at the centre of the swastikas, which in several cases have fallen off.Footnote 24 On a few of the covers, they are also placed in the corners of the outer border of the binding. This use of coloured leather to highlight aspects of the decoration is unusual and has not been noted on any other Ilkhanid binding to date (Figure 11).

Figure 11. DAK Rasid 72, detail of green leather punch at the centre of the swastikas of Juz’ 2.

Furthermore, the tooling style employed on the binding of the Hamadan Qur'an differs substantially from the bindings of the three other imperial Ilkhanid Qur'ans. Each is decorated using small tools of arcs, punches, and pallets to create a densely hatched surface with little or no use of gold. The thick borders around the central panel feature the same densely hatched surfaces. The tooling style is typical of many Islamic bindings of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries found in North Africa, Egypt, and Syria.Footnote 25 Rosettes, stars or squares placed at the centre of the cover were filled with dense tooling, or the field was covered with geometrical patterns emanating from a central star using thick strapwork. Ben Azzouna also records this tooling method on other Ilkhanid bindings of the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.Footnote 26

The binding of the ‘Anonymous Baghdad Qur'an’, for example, is decorated with an elongated cloud collar profile and segmented borders filled with densely tooled hatchwork with small gilded punches and reserved squares appearing as part of the textured pattern. Several of the juz’ and fragments of folios are scattered in various collections but the Topkapı Palace Library (TSK) contains three volumes that retain their original bindings: Juz’ 2 dated Ramadan 702/April 1303 (TSK.EH. 250); Juz’ 4 which is undated (TSK.EH. 247), and Juz’ 13 dated Rabi’ I 705/November 1305 (TSK.EH. 249).Footnote 27 The binding of Juz’4 is stamped with the name of cAbd al-Rahman in small diapers in the border (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Upper cover of Juz’ 4, of the ‘Anonymous Baghdad Qur'an’ copied in Baghdad 701–707/1302–1308, TSK.EH. 247, 52 x 37cm. After Tanındı, “Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Kütüphanesi'nde Ortaçağ İslam Ciltleri”, fig. 18.

The second of this group, now known as the Baghdad Qur'an, was copied between 1306–1311Footnote 28 for Öljaytü's funerary complex in his new capital at Sultaniyya (Figure 13).Footnote 29 The cover of Juz’ 7 (TSK.EH. 243) is decorated with an interlace repeat pattern of ten-pointed stars with broadly tooled strapwork and the same technique of reserving small squares is found in the tooling of the borders and the interstices of the strap work.

Figure 13. Upper cover of Juz’ 20 of a Qur'an copied in Baghdad between 706–8/1306–1308, TSK.EH. 245, 71 x 49.5cm. After Tanındı, “Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Kütüphanesi'nde Ortaçağ İslam Ciltleri”, fig. 16.

The third comparative imperial Qur'an was copied in Mosul, commissioned in 1306, and completed in 1311.Footnote 30 The parts are also scattered in various collections. Some volumes retain their original bindings, which are all the same: two in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts (TIEM 539, 540) and one volume in the Topkapı Palace Library (TSK.EH. 232).Footnote 31 The bindings of the Qur'an have a large eight-armed geometrical rosette or star polygons contained within a central panel by tooled multiple borders (Figure 14a and b). The tooling is again made up of arcs and pallets which produced a textured surface with small, reserved squares.

Figure 14a. Upper cover, TIEM 540, Juz’ 2, copied in Mosul between 705–10/1306–1311, 57 x 40 cm. 14b. Detail of tooling of upper cover.

In returning to the Hamadan Qur'an, the tooling is mainly defined by line without the creation of densely hatched leather for parts of the design and the thin borders are made up of impressions of single tools to create a braided pattern. The ten-pointed star with the decagon and use of small five-armed swastikas and five-fold knots are a more sophisticated, complicated combination. It is also found on later Ilkhanid examples such as the binding of a Qur'an manuscript copied in 30 volumes in Maragha between 1338–1339Footnote 32 (Figure 15), another dated 1365,Footnote 33 and the covers of a Jalayirid binding dated by manuscript to 1373–1374.Footnote 34 Other examples of this geometrical configuration also appear on bindings in the Mamluk realm and are dateable to the middle of the fourteenth century.Footnote 35

Figure 15. Front cover of Juz’ 13 of Qur'an, Maragha, 738–739/1338–1339, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 29.58, 33 x 24cm. Source: Image Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Figure 16a. DAK Rasid 60, Juz’ 1, upper cover, 30 x 38 cm. 16b. Detail of upper cover.

The Hamadan and Maragha bindings appear to represent a different style of tooling when compared to the other three imperial commissions relying on more complex geometrical configurations and a combination of single tools for borders achieving a lighter, more elegant effect. It is decorated in a more delicate fashion, with the incorporation of spidery swastikas and five-fold knots representing the emergence of a new style. As a firm comparison can be drawn between the Hamadan Qur'an and the other comparative Ilkhanid bindings of the fourteenth century, it must be assumed that the Qur'an was most probably bound in Hamadan.

Other examples of this geometrical configuration also appear on bindings in the Mamluk realm and are dateable to the middle of the fourteenth century.Footnote 36 These two Qur'ans—DAK Rasid 60 and Rasid 61—originally of 30 parts use the same geometrical combination of a ten-pointed star combined with a decagon (except Juz’ 1 and 30 of Rasid 60).

Both these Qur'an manuscripts contain waqf endowments to the madrasa of the Amir Sirghatmish dated Jumādā I 757/16 May 1356.Footnote 37 Rasid 60 consists of 29 volumes, as volume 14 is missing, and was copied in fine muḥaqqaq script by Mubarak Shah cAbdullah whose name appears on fol. 54a of Juz’ 30. David James has suggested he was trained in Baghdad as his hand bears a striking resemblance to that of Ibn al- Suhrawardi (d. 1320–1321) who copied the ‘Anonymous Baghdad Qur'an’. Based on the style of the illumination and calligraphy he has attributed this Qur'an to the first quarter of the fourteenth century and place of copying to Tabriz or Baghdad.Footnote 38 The illumination of the Qur'an has many Ilkhanid elements and so one might assume that this Qur'an was copied and illuminated in Persia. Abou-Khatwa has also pointed to the striking resemblance of the illumination to other Ilkhanid manuscripts; she has suggested two possibilities for this: either these volumes were an Ilkhanid gift to the Amir or they were produced in Cairo by Persian craftsmen as Sirghatmish had many in his service.Footnote 39 She notes the addition of several peculiar marginal medallions in a different hand, suggesting that they were added in Cairo.

The first and last juz’ of Rasid 60, however, differ from the others in terms of their binding decoration. They are decorated with large rosettes whose centres are tooled in a complex geometrical configuration with five-armed swastikas and five-fold knots (Figure 15).

The borders also contain tooled five-armed swastikas, and knotted projections extend into the central panel (as on the Hamadan Qur'an) and are quite unlike any bindings produced in Mamluk Cairo. The similarity with the Hamadan Qur'an in the use of swastikas and knotted finials projecting into the central field would indicate that the covers of Rasid 60 (Juz’ 1 and 30) were most probably bound in Iran.Footnote 40 Abou-Khatwa refers to Sirghatmish as the ‘Master of Reuse’ so, given that the lower cover of Juz’ 30 is today badly damaged, one might surmise that Sirghatmish commissioned the remaining volumes to be rebound in a Persian style (perhaps using the design of the Hamadan Qur'an as inspiration), while leaving the covers of Juz’ 1 and 30 as a reference to the original binding.Footnote 41 The other volumes are all bound in the same manner, with a central roundel in which a ten-pointed star overlays a decagon. The borders have the same type of cable design as those of the Hamadan Qur'an, also with projections into the central field from the upper and lower borders of the central panel. The extant flaps of the bindings are tooled with a roundel with a six-pointed star at the centre whose tips extend, creating triangles meeting the perimeter of the circle. The compartments created by the design include five-armed swastikas and knots (Figure 17a and b). The use of a small reserved square in the tooling of the knotted projections into the central field can be clearly seen.Footnote 42 These bindings incorporate so many of the elements found on the Hamadan Qur'an that they must have been bound in Persia or by a Persian binder in Cairo.

Figure 17a. DAK Rasid 60, Juz’ 2, upper cover, DAK Rasid 60, 27 x 38 cm. 17b. Detail of upper cover.

The illumination of Rasid 61 also has several Ilkhanid features, but Abou-Khatwa has pointed out that it was most probably done by illuminators in Cairo. The bindings of Rasid 61 are also decorated with a roundel which contains a ten-pointed star/decagon combination, but the decoration of the compartments is composed of hatched arcs without any swastikas. Knotted finials float above and below the roundel, and the borders of Rasid 61 are made up of a segmented square tool with a central punch, a pattern which is found on several other Mamluk bindings of the period and is a clear indication that Rasid 61 was bound in Cairo (Figure18a and 18b).Footnote 43

Figure 18a. DAK Rasid 61, upper cover, 29 x 38.4. 18b. Detail of upper cover.

In 1985, in his discussion of the relationship between Mamluk and Ilkhanid bindings, Basil Gray suggested that the geometrical patterns found on Ilkhanid bindings were transferred into Mamluk Egypt. He notes that they appear first on architectural decoration and then, in the fourteenth century, make their appearance on Mamluk bindings.Footnote 44 Gray's comments were a spirited response to those of Richard Ettinghausen who, some 30 years earlier, compared the Hamadan and Maragha Qur'ans, which have been discussed above, to a Mamluk Qur'anFootnote 45 which is dateable to the end of the fourteenth century. He declared ‘None of the Persian examples of this century, so far discovered, has a field which is completely covered with geometric configuration.’Footnote 46 This was not a fair comparison as the Mamluk Qur'an was bound at least 70 years after the two Persian examples he chose for comparison. However, the central rosette of this binding includes an octagon with two overlapping squares which carries a clear resonance to its Ilkhanid forebears, which Ettinghausen chose not to acknowledge.

Ilkhanid bindings and those of the Hamadan Qur'an represent the vestiges of this vibrant geometrical tradition which was discarded by Persian binders in the middle of the fourteenth century in favour of a new aesthetic derived from Chinese art with the particular employment of the cloud-collar motif.Footnote 47 Why these configurations were wholeheartedly rejected for binding decoration but maintained in architecture, one can only guess. It may be that the development of stamps sometime in the middle of the fourteenth century facilitated this change as stamps based on cloud-collar profiles could be easily produced to decorate bindings without any need for time-consuming hand tooling. Complex geometrical designs needed to be conceived to fit different sizes of covers and then tooled by hand, with each element drawn to fit the pattern. Mamluk binders continued to employ these complex designs, creating a storehouse of geometrical patterns which were also reflected in the architectural decoration and woodwork of the period. However, the aesthetic that had attracted Persian binders from the middle of the fourteenth century soon found its way into the repertoire of the designs of Mamluk binders in the middle of the fifteenth century and subsequently spread to Ottoman Turkey, India, and Southeast Asia, dominating Islamic binding decoration to the present day.