The manuscript is a brilliant reflection of not only sixteenth-century court life in Herat and Bukhara but also the complicated ideological situation in Mawarannahr and its territories, now known as Afghanistan, during the period of political turmoil when the three main powers in the region—the Safavids, the Shaybanids, and the Mughals—were fighting for dominance. This glimpse of history is revealed through a touching story of personal relationships: the friendship between a poet, Badr al-Din Hilali (b. Astarabad circa 1470, d. Herat 1529) and a calligrapher, Mir ‘Ali al-Husayni Haravi (b. Herat 1465, d. Bukhara 1544) and their dependence on a vengeful ruler. All of them were illustrious celebrities of their time.

Later the manuscript travelled to India where it had a complete facelift of its decorative programme, acquiring new margins with a wide variety of images and colour schemes: from elaborate geometric and floral patterns, to the extremely rich range of real and fantastical birds and beasts.

For both the poet and the calligrapher, the most crucial point in their lives and careers was the conquest of Herat by Shaybanid (Abu'l-Khayrid)Footnote 2 Sultan ‘Ubaydullah in 1529. The poet was executed by ‘Ubaydullah on the main square of Herat right after its conquest, and the calligrapher lost his home, having been moved from his native Herat to Bukhara as part of the Sultan's intellectual booty.Footnote 3 The imperial ambitions of ‘Ubaydullah played a formative role in the establishment of the Bukhara atelier in Mawarannahr, especially after the decline of Samarqand, both as a capital and as an artistic centre of Central Asia. Due to the efforts of the Uzbek rulers, Bukhara inherited artisans and craftsmen from Herat, among whom were Shaykhzada Mahmud muzahhib (fl. 1500–60), the most able pupil of Bihzad (d. 1536), ‘Abdullah Bukhari, and Shaykham b. Mulla Yusuf.Footnote 4 The rivalry between the three courts of the Safavids, the Shaybanids, and later the Mughals was not only military and political but also artistic as ateliers were the best showcase of their success and superiority. It was in Bukhara that Mir ‘Ali, who appears to have become increasingly homesick, produced this collection of poetry in memory of his executed friend.

The Cambridge manuscript is the earliest known copy of Hilali's poetry. It is known as a Divan (collected poetic works);Footnote 5 however, it is only a substantial selection, not a complete collection of his poetry, when compared with the known printed editions.Footnote 6 Compared with Sa‘id Nafisi's edition it contains only 147 ghazals out of 417,Footnote 7 four qit‘as out of ten, and nine ruba‘i out of 35. The missing front page must have contained at least one or two ghazals and possibly a ruba‘i as the average number of poems on a page is between one and three, depending on their length, which is rather random (i.e. between two and nine bayts).

The selection was made by Mir ‘Ali himself, who was not only a famous calligrapher but a bilingual poet in his own right. Not surprisingly he was particularly interested in composing chronograms (mostly to be used in colophons), ciphered poems, and witty riddles (mu‘amma’).Footnote 8

How two of Mir ‘Ali's manuscripts helped Akimushkin to date ‘Ubaydullah's siege of Herat

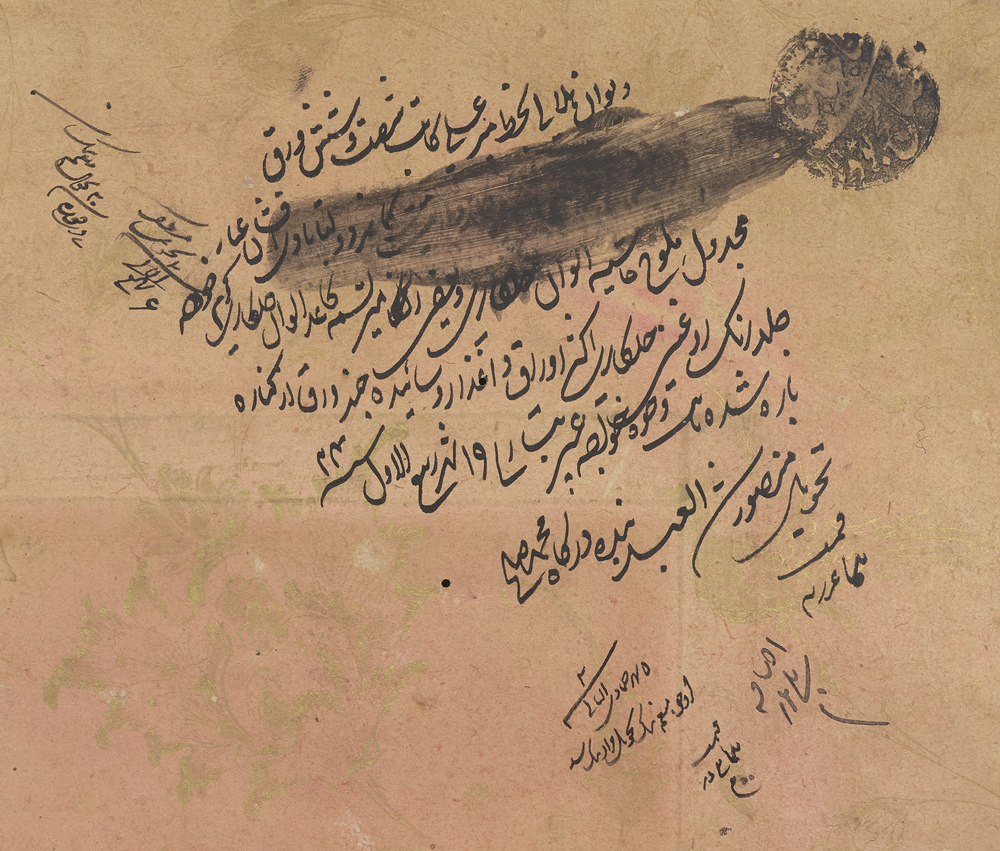

The colophon of the Cambridge manuscript contains the date but not the place (see Figure 2).

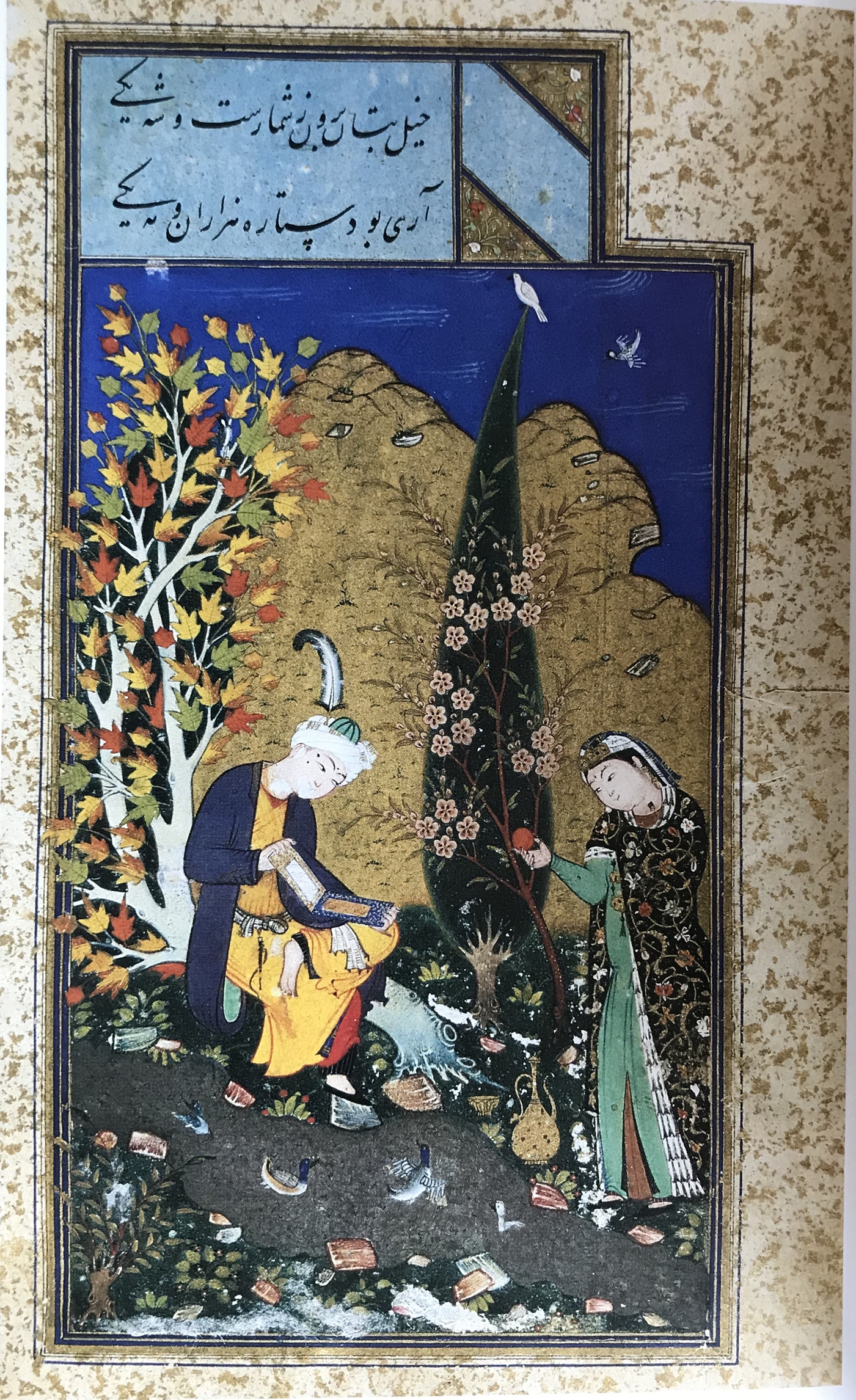

Figure 1. Two male youths reading poetry in the blossoming garden, Anthology of Persian poets, calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, Bukhara, Dhu'l-Qa‘da 935/July–August 1529, C-860, f. 9r. Source: © Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, St Petersburg.

Figure 2. Colophon, Divan by Hilali, calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, 938/1531–32 [in Bukhara], Ms Kings Pote 186, f. 133r. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

Two other contemporaneous manuscripts, written by Mir ‘Ali around this time, help to identify this important information. Both were studied and brought together by my university professor Oleg Akimushkin in his 1962 publication.Footnote 9 The first one is the most crucial for my main argument. It is now kept in the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM) in St Petersburg. It is a jung (i.e. Anthology of Persian poets (C-860)). According to its colophon (f. 56r), it was completed in Dhu'l-Qa‘da 935/July–August 1529 in Bukhara (see Figure 3).Footnote 10

Figure 3. Colophon, Anthology of Persian poets, calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, Bukhara, Dhu'l-Qa'da 935/July–August 1529 C-860, f. 56r. Source: © Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, St Petersburg.

The second manuscript—Mahmud ‘Arifi's Guy-u Chawgan dated 934/1527–28, now in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin—is the latest known codex that Mir ‘Ali wrote while still in Herat before being moved to Bukhara (see Figure 4).Footnote 11

Figure 4. Colophon, Guy-u Chawgan by Mahmud ‘Arifi, calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, Herat, 934/1527–28, Per 194, f. 24r. Source: © Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.

Akimushkin's chronological and geographical comparison of the two manuscripts allowed him to establish a more precise date for the siege of Herat by ‘Ubaydullah Sultan, namely between the beginning of 1528 and mid-1529. This was an exciting discovery as the dates for this crucial event varied drastically, ranging within two decades (1515–39),Footnote 12 even in more or less contemporaneous historical sources, which led to further confusion and misattribution. For example, E. G. Browne,Footnote 13 who mentioned Hilali's Divan in his Catalogue, suggested that it was ‘copied during Hilali's life-time’ as, in his opinion, ‘Ubaydullah besieged Herat in 939/1532–33. Browne also misread the date in the colophon: he mentions 937/1530 (instead of 938/1531–32), which enhanced the chances of Hilali being alive when both he and Mir ‘Ali were still in Herat. In that case, Mir ‘Ali was copying his poems not in memory of, but in collaboration with, the author.Footnote 14 The range of the dates for the siege, and even some extraordinary information about Mir ‘Ali going from Herat not to Bukhara but to Kashmir and dying there several years later (Vaqi‘at-i Kashmir by Muhammad A‘zam), led some scholars to believe that there were two Mir ‘Alis, an idea that was later rejected.Footnote 15

Why did ‘Ubaydullah have the poet executed?

Mawlana Badr al-Din, or Nur al-Din Hilali Astarabadi Chaghata'i (b. Astarabad circa 1470, d. Herat 1529), a prominent bilingual poet of Turkic origin was writing mainly in Persian but also in Chaghatay. In his native Astarabad he received a good education and at the age of about 20, he moved to Herat, where he became a nadim of ‘Ali Shir Nava'i (1441–1501) and joined the circle of Sulṭan Ḥusayn Bayqara (1438–1506). Hilali is famous for his exceptionally beautiful lyrics, collected in the Divan, and three masnavi poems: Layli va Majnun (‘Layli and Majnun’), Shah-u Gada (‘The King and the Beggar’), and Sifat al-‘Ashiqin (‘Disposition of Lovers’). He was also close to ‘Abd al-Rahman Jami (1414–92), the last great classic of the Golden Age of Persian poetry, whom he accompanied on Hajj. The royal patronage of the young Safavid Prince Abu'l-Nasr Sam (1517–66), the son of Shah Isma‘il I and the younger brother of Shah Tahmasp,Footnote 16 perhaps played a tragic role in his career and life. This particular association is often mentioned as the cause of Hilali's execution: it was this closeness to the Shi‘i court of Sam Mirza that made the chroniclers assume that he was also a Shi‘i, which ‘Ubaydullah Sultan used as a pretext to put him to death.Footnote 17 However, Sam Mirza thought of Hilali as a Sunni among the Shi‘is,Footnote 18 although in the introduction to his most famous Shah-u Gada he praises ‘Ali b. Abu Talib.Footnote 19 Hilali stayed in Herat during the turbulent period when the city was claimed by the two rising powers, the Shi‘i Persians and the Sunni Uzbeks. The population of these regions, and especially the urban centres, had to suffer the constant changes of power which used religious affiliations as an easy pretext for political purges. In some cases, religion was used for personal slander at court, which made confessional peculiarities rather fluid. Hilali's case was probably one of them, although with a definitively tragic end, when ‘Ubaydullah had the poet executed at the Chahar Su square of Herat, right after he entered the city,Footnote 20 followed by the total confiscation of all his possessions.

However, some sources give more literary interpretations of the reason of the poet's death, which is his hajv (invective) on the Sultan, in which he was allegedly accusing him of being an improper Muslim who undermined the pillars of the religion by being nasty to Muslim orphans.Footnote 21 Such an insult could obviously not be forgiven by the ruler, who justified his conquests by fighting for the true faith.

The image of ‘Ubaydullah Khan Shaybani (1487–1540) has been reinterpreted drastically depending on the agenda of the source and varies accordingly: from a nomadic savage to the most sophisticated enlightener, patron of arts, and even a mystic poet, having received his name and blessing from Nasir al-Din ‘Ubaydullah Ahrar, known as Khwaja Ahrar (1404–1490).Footnote 22

‘Ubaydullah Khan—enlightened tyrant

‘Ubaydullah received a very good education, which allowed him to write prose and poetry in three languages: his native Turki, Persian, and Arabic. His Divan-i ‘Ubaydi in Turki was copied by the best calligrapher of his time Sultan ‘Ali Mashhadi and is now in the British Library.Footnote 23 After the death of his father Mahmud Sultan (1454–1505) he was de facto ruler of Bukhara. From 1533 until his death in 1540, ‘Ubaydullah was the supreme Khan of the Uzbek Shaybanid state. The conquest of Herat was important for him not only as a political aim. He had it as some sort of an obsessive dream of ‘cultural appropriation’. In one of his poems in Turki, he revealed his only unfulfilled wish: to stay in Herat for at least a month.Footnote 24

For an ‘enlightened patron’ of arts and a poet himself,Footnote 25 especially being almost 20 years younger than the mature poet, to order him to be executed was quite a radical measure, which meant that the poet's fault had to be exceptional.

The satire on ‘Ubaydullah, ascribed to Hilali, is often identified as intentional slander by his court rivals—Baqa'i and Shams al-Din Muhammad Kuhistani. According to a rather pro-‘Ubaydullah version, Hilali did write the hajv on the Sultan, possibly to inspire his compatriots to fight the invaders,Footnote 26 but the noble ruler forgave him because of his talent and offered him a place at his court. According to another legend, ‘Ubaydullah repented having put the poet to death, after he realised that malicious courtiers had slandered the poor poet out of jealousy, but it was too late.Footnote 27 It is quite possible that the hajv story appeared as a later apocrypha added to the legends about Hilali and ‘Ubaydullah. For example, in the ruba‘i, mentioned in the treatise by Darvish ‘Ali Changi (d. 1620s), the poet gives ‘Ubaydullah the title ‘Khan’, which he only obtained after Hilali's death.

Later apocryphal mythology associated with Hilali's death

According to another version by ‘Ali Changi, Hilali was under pressure from Shah Tahmasp, who demanded evidence of Hilali's loyalty following an incident that had taken place in the past. When ‘Ubaydullah was besieging Herat, he requested that the Herati poets send him their specimens, presumably of panegyric nature, as a sign of their surrender. Hilali, believing that ‘Ubaydullah would never succeed, composed a derogatory poem and sent it to the Sultan. When ‘Ubaydullah entered Herat, Hilali was executed despite the most beautiful ‘rehabilitation’ ode he had produced glorifying ‘Ubaydullah's victory.Footnote 28 Changi also mentions that the crucial bayt in that qasida was misinterpreted by his enemies. In revenge, Shah Tahmasp ordered the capture of ‘Ubaydullah's close nadim, Najm al-Din Kawkabi, his favourite poet, musician, and astrologist, who was on his way from Mashhad to Bukhara. ‘He achieved the rank of martyr’ (ba daraja-yi shahadat rasanid), even being dismembered: his head went to Tabriz, while his body was sent to Bukhara.Footnote 29

As a result of caravans of migrants, especially courtiers and intellectuals, moving across the constantly changing borders between the Safavid and Shaybanid territorial possessions, religious affiliation seems to have been a serious, and curiously fluid, issue. This could be the reason why the matter of ‘proper’ piety for ‘Ubaydullah was particularly sensitive, and why the poem could have been treated as a serious insult worthy of the most severe and immediate punishment. Confiscating the poet's properties could have been interpreted as his reaction to the verse about the poor robbed orphans: this had to show that he was, in fact, fairly confiscating the possessions of a rich and successful courtier who hardly qualified as a poor orphan, with the aim of distributing his wealth among the poor orphans. Such fluidity could have caused another legend according to which the invective was originally ascribed to Hilali but ‘dedicated’ to Safavid Shah Tahmasp, ‘Ubaydullah's main rival.Footnote 30

Mir ‘Ali al-Mashhadi-Haravi-Bukhari, a royal calligrapher

In the colophon of the Cambridge manuscript of Hilali's Divan, the calligrapher signed his name Mir ‘Ali al-katib al-sultani (‘the royal scribe’), which was not unusual.Footnote 31 At the same time he also called himself ‘humble’ (al-faqir), which was even more common. However, to have both in one signature is quite rare. This may indicate that he was hoping to keep this copy for himself, but was not sure that he would be able to do so and mentioned both signatures just in case.

Mir ‘Ali Haravi, or Mir ‘Ali Husayni Haravi, or Mir-Jan (1465–1544), could have had as his nisba Mashhadi-Haravi-Bukhari as he lived and worked in all three cities. He was famous as an outstanding calligrapher and the teacher of nasta‘liq script throughout the sixteenth-century Persian-speaking world, from Mughal India to Ottoman Turkey, known for being second only to Mir ‘Imad (1554–1615) of Qazvin. He, like Mir ‘Ali Tabrizi, had a strong influence on later generations of calligraphers. There are quite a few large-scale codices surviving that are signed by him. However, by the time he reached the peak of his career he was specialising mainly in album leaves that were executed with meticulous perfection.

Mir ‘Ali, a Herati in Bukhara

Mir ‘Ali was born to a Seyyid family in Herat, where he studied calligraphy with Zayn al-Din Muhammad who was a student of Sultan ‘Ali Mashhadi. At the age of nine he moved with his family to Mashhad, but soon after, he returned to Herat, where he was employed by the governor of Herat as a personal scribe. This brought him to the court of Sultan-Husayn Bayqara who awarded him a special title katib al-sultan, and treated him benevolently. After the Sultan's death, Mir ‘Ali lived between Mashhad and Herat. When Shah Isma‘il captured Herat in 1512, he entered under the patronage of Karim al-Din Habibullah Savaji, his vazir.Footnote 32 When Habibullah was assassinated in the dispute between the Qizilbash amirs, it was Sam Mirza Safavi, the younger brother of Shah Tahmasp, who became the governor of Khurasan,Footnote 33 and whose favours Mir ‘Ali thoroughly enjoyed for three years in Herat until 1528–29, when ‘Ubaydullah besieged the city. As a result, Mir ‘Ali was brought to Bukhara together with several other talented artists and craftsmen. In Bukhara he was also treated with great respect, being appointed the Head of the Royal Chancellory and the tutor for ‘Ubaydullah's son and heir Abu'l-Ghazi ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Khan. Mir ‘Ali stayed in Bukhara for another 16 years, until his death at the age of 70 in 1544.Footnote 34

There is a later date mentioned for his death, based mainly on the information in the manuscript which is considered to be the last known codex signed by Mir ‘Ali, and written for ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Khan in Bukhara in 956/1549. This manuscript, which contains three romantic poems in Persian: Si-nama (‘Thirty Epistles’) by Mir Husayn, Dah-nama (‘Ten Epistles’), and Rawzat al-Muhibbin (‘Garden of Lovers’), is now in Hyderabad, in the Salar Jung Museum.Footnote 35

There are about 50 surviving manuscripts ascribed to Mir ‘Ali's qalam, 20 of which were produced by him in Bukhara. Among the most important of them are Sa‘di's Bustan and the Gulshan muraqqa‘, now in the Golestan Palace Library.Footnote 36 This album was compiled between 1605 and 1629 and includes about 90 of Mir ‘Ali's signed works, which were produced between 1533 and 1544. Such productivity could be explained by the fact that he established his own school in Bukhara and even allowed his pupils to sign his own works. Quite a few anecdotes are known that mention his students signing their pieces with his name, either with his permission or even out of malice.Footnote 37

One of his pupils, Khwaja Mahmud b. Khwaja Ishaq al-Shahabi Siyavushani, was known for signing his calligraphy with his teacher's name and arrogantly saying that he used it only to sign his worst works.Footnote 38 Siyavushani's father was a wealthy merchant who was also brought by ‘Ubaydullah to Bukhara with all his family and possessions, where Mir ‘Ali accepted young Mahmud as his pupil. Having quite a commercial mind, he managed to save enough money to leave Bukhara for Balkh, where he did not have to earn his living by calligraphy. Here he produced pieces for pleasure, as souvenirs for his high-ranking friends, whom, as he was also a good musician, he loved entertaining.Footnote 39 Maybe his student's success story added frustration to Mir ‘Ali's situation when he could not afford to escape from the Bukhara court and had to work hard for the rest of his life. In the following verse Mir ‘Ali complains how he became a victim of his own art:

…That all the kings of the world sought me out, whereas

In Bukhara for means of existence, my liver is steeped in blood

My entrails have been burnt up by sorrow. What am I to do?

How shall I manage?

For I have no way out of this town,

This misfortune has fallen on to my head for the beauty of my writing,

Alas! Mastery in calligraphy has become a chain on my feet of this demented one.Footnote 40

He started to produce lots of separate album pages and samples for sale, trying to save money for his Hajj trip and old age.Footnote 41 Despite their large quantity, especially given that some of them were not genuine Mir ‘Ali's works, they were already all treasured as expensive collectables during his lifetime. Budaq Munshi and ‘Ali Efendi mentioned the prices for the calligraphic specimens produced by Mir ‘Ali Haravi and Sultan ‘Ali Mashhadi. According to their evidence, Mir ‘Ali's works were more expensive: Sultan ‘Ali's qit‘a, consisting of two bayts would cost 400–500 Ottoman akche, while a similar piece by Mir ‘Ali would go for 500–600 (‘Ali Efendi), although when Mir ‘Ali was still alive one could buy his calligraphic qit‘a for one khani. After his death such pieces were on offer for two shahis (Budaq Munshi).Footnote 42

There could be another reason why Mir ‘Ali was not feeling absolutely comfortable in his new environment in Bukhara, although he was trying to be loyal to ‘Ubaydullah by dedicating poems to him in Persian and in Chaghatay and calling him the man ‘of heavenly justice and with an ocean-like heart’.Footnote 43 On the grounds of his name, Ebadollah Bahari concluded that Mir ‘Ali was Shi‘i;Footnote 44 Stuart Cary Welch called Mir ‘Ali a ‘devout Shiite’,Footnote 45 while A.-M. Schimmel mentions elegant chronograms which he designed for the decoration of the Imam Riza shrine in Mashhad,Footnote 46 which suggests his position at the Shaybanid court could have been rather awkward. Mir ‘Ali did not join the entourage of the teenage Sam Mirza and his laleh (‘tutor’), the actual governor of Herat Husayn Khan Shamlu, when they fled to Tabriz with the most talented members of the kitabkhana. It is not known if he refused to join Sam Mirza or was left behind; if he willingly went to Bukhara with ‘Ubaydullah and then bitterly regretted it or was taken there by force. We only know that Mir ‘Ali was deeply depressed in Bukhara, despite his high position and recognition of his talent and work, especially during the reign of ‘Ubaydullah's son and his pupil ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Khan, when he was appointed Malik al-kuttab (‘King of the scribes’).Footnote 47

Whether the reasons for Mir ‘Ali's depression were of an ideological, religious, financial, or personal nature, the fact was that he was chronically homesick, longing for his beloved Herat and friends there, like the unfortunate Hilali, whose poetry resonated so perfectly well with his own devastating nostalgia for his ‘paradise lost’—and that was probably the reason why he decided to produce Hilali's Divan.

Hilali as Hafiz

The ghazal that Mir ‘Ali put on the current opening page, which was originally the second,Footnote 48 is the one that emulates the ghazal that is the first in Hafiz's Divan, but listed as the thirty-fifth in Sa‘id Nafisi's edition.

Its explicit is as follows:

A-lā yā ayyuhā s-sāqī adir ka'san wa-nāwilhā

ki ‘ishq āsān nimūd avval valī uftād mushkilhā.

Ho, saki, haste, the beaker bring,

Fill up, and pass it round the ring;

Love seemed at first an easy thing—

But ah! the hard awakening.Footnote 49

And was borrowed from Hafiz who himself had borrowed it from his predecessors.Footnote 50

It is known that Hafiz's Divan was compiled after his death by his devoted disciples. The first ghazal was chosen without consideration for alphabetical order and placed in the front as a type of fatiha, introducing the poet's credo and his whole philosophical legacy. By bringing the Hafiz-reminiscent ghazal closer to the front of Hilali's Divan, Mir ‘Ali was probably establishing a link between Hafiz and Hilali, and between Hafiz's disciples and himself, after the death of his friend.

Mir ‘Ali as the editor of Hilali's selection of poetry

Mir ‘Ali's approach to Hilali's poetry was truly imaginative and selective, as his version has only about one-third of his friend's poetic legacy compared with the known editions of his Divan.Footnote 51

The calligrapher very seldom reproduced the poems in full. Much more often he would omit between one and three bays in the middle before the final bayt containing the takhallus (poet's signature). Ghazals, qit‘as, and ruba‘is are not organised in any obvious order, certainly not alphabetically. One page can have all three forms, although the last four pages contain only ruba'is. Mir ‘Ali might have been reducing the size of the poems deliberately to fit at least two of them on a page which would allow him to use his way to paginate the manuscript.

How Mir ‘Ali used Hilali's poetry to paginate his manuscript

It is possible that Mir ‘Ali deliberately used a very witty trick to link the two subsequent pages as he was all-too-familiar with the work in the atelier and was probably expecting that the manuscript would be rebound at some stage and its pages would be trimmed together with coustods—the catchwords indicated in the bottom left corner of each verso page. After this traditional pagination was cut off, Hilali's method had been the way to follow and restore the order of the pages if disturbed. The system he introduced in his manuscript is based on dividing the poems between the two pages. Very often he put the first bayt of the next ghazal as the last one on the previous page.

The marginal decorations are also extremely helpful for checking the sequence of the pages, as they were specially designed to match both sides of each double page opening. For example, such an arrangement helped to identify that the order of the pages which are now f. 6v and f. 63r had been disturbed. This is evident from the text of the qit‘a (No. 10 in Nafisi's edition), which happened to be separated as well as the symmetrical marginal decoration on both sides of the double page opening (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Poem divided between two subsequent pages with matching marginal decoration. Divan by Hilali, Ms King's Pote 186, f. 6v, Bukhara 938/1531-32. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

Figure 6. Poem divided between two subsequent pages with matching marginal decoration. Divan by Hilali, Ms King's Pote 186, f. 63r, Bukhara 938/1531-32. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

Travels of Hilali's Divan from Bukhara to Cambridge via Delhi and its previous owners: Shah Jahan, Antoine Polier, and Ephraim Pote

The manuscript travelled from Bukhara to India where it entered the Imperial library. Shah Jahan was particularly fond of Mir ‘Ali's works. His sons, Princes Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb and, later, Prince Shuja‘, were taught calligraphy using his patterns.Footnote 52

The manuscript could have been acquired by or for Shah Jahan immediately after he became the emperor, or even earlier, which could have happened right after the death of Mir ‘Ali, or ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, as, according to Stuart Cary Welch, the calligrapher's children and disciples, including the most talented of them, left Bukhara and went in different directions. Ahmad Mashhadi went back to Mashhad and several headed off to India. In the Bodleian Anthology of the poets of Jahangir Shah by Qati‘ Haravi,Footnote 53 Khwaja Mahmud Ishaq Siyavushani and Mir Kulangi are mentioned among those who went to India and became the royal scribes at the court of Akbar.Footnote 54 Among the owners of the manuscript we can be sure of three: Shah Jahan, Antoine Polier, and Ephraim Pote.

It was thanks to Pote that Cambridge received Hilali's Divan, which happened to be among a large acquisition of manuscripts—550 boxes that used to belong to Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier. A Swiss engineer, Polier (1741–1795)Footnote 55 ended his military career as Lieutenant-Colonel of the East India Company. He was also the chief architect of Nawab Shuja‘ al-Dawla in the kingdom of Awadh.

Polier accumulated enormous wealth during his 30-year stay in India, which included a significant collection of Persian and Indian book art, most of which he brought with him to Europe. Unfortunately, he was robbed and murdered in France in January 1791, only four years after he married Anne-Rose-Louise Berthoud, the daughter of Baron van Berchem, possibly on the pretext of his pro-Robespierre leanings.Footnote 56 Polier's collections are now dispersed between Paris, London, Berlin, Lausanne, and Cambridge.

The evidence of Polier's ownership of the Cambridge Divan can be seen on the flyleaves of the manuscript with the imprints of his first seal dated 1181/1767, his rank Mayjur (Major), and his honorific title Bahādur Arslān-i Jang.Footnote 57 This shows that the Divan was among the earliest of Polier's acquisitions. Altogether Polier subsequently had four seals commissioned in India between 1767 and 1782. The fifth and the last one Polier ordered in France and is dated 1793–94, i.e. the second year of the French “République” (see Figure 7).Footnote 58

Figure 7. Imprint of the seal of Antoine Polier (Mayjur Antuan Polye Bahadur Arslan-i Jang 1181), Divan by Hilali, Ms King's Pote 186, Bukhara, 938/1531–32, f. 45r. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

In 1788 Polier had to leave India in haste and was physically unable to take all his possessions to Europe, and he left some of them with his old friend Claud Martin. Those 550 boxes of his manuscriptsFootnote 59 happened to be acquired by Edward Ephraim Pote (1750–1832),Footnote 60 a British civil servant in Patna, who shipped them to England, to his two alma mater colleges: Eton and King's.

The circumstances that allowed Pote, a son of the bookseller, to acquire Polier's manuscripts are not obvious. It is possible that Pote ‘acquired’ what Polier had to leave behind at the last minute. This is how it was explained in the correspondence between the Cambridge scholars Henry Bradshaw of King's and Henry Palmer of St John's who were dealing with the King's collection 76 years after the manuscripts had arrived in Cambridge:Footnote 61 “…There seems no doubt that the collection acquired by Mr Pote in 1788 contains a large portion of Polier's library as he left it” (emphasis mine).Footnote 62

When the manuscripts arrived in England they were only accompanied by the alphabetically organised handlists with no explanatory notes. Pote shipped the manuscripts in eight containers, which he ordered to be divided more or less mechanically (in alphabetical order) into halves, with one half of the collection to be sent to King's College, Cambridge (chests A, B, C, D) and the second half to Eton (chests E, F, G, H)Footnote 63 “to show his gratitude to… those institutions he was indebted for his education”.Footnote 64 Now both parts of the Polier-Pote collection are reunited in the Main Library of Cambridge University.

Although it is known that Hilali's Divan arrived as part of that huge collection, there is no sign of Pote's ownership in the manuscript. It is possible that he himself never saw the manuscripts, or even had a chance to inspect each of them personally, let alone to read and study, sign, or imprint them with his seal.

Seals and inscriptions on the flyleaves

The flyleaves contain very important information about the provenance and the decorative programme of the manuscript, including the missing two folia with the miniature paintings which are mentioned twice by two different librarians.

Some dates are mentioned using Persian names of the months until the time when the emperor abandoned them. Some information and especially the numbers are in siyaq.Footnote 65

Of particular interest are several following inscriptions.

One is a short note in large nasta‘liq script where the total number of folia in the manuscript is mentioned as 66 (now the manuscript has only 63), two of which should have contained paintings (tasvir), mentioned in the inscription. The note could be related to ‘Abd al-Haqq Amanat Khan (d. 1054–55/1644–45)Footnote 66 as the inscription is the closest to his personal seal imprint. It is of special importance as this is the first mention of ‘Abd al-Haqq when he had just been awarded the title ‘Amanat Khan’: Yaft ‘Abd al-Haqq khatab-i Amanat Khan chun kamyab ast az Shah Jahan (‘Abd al-Haqq was addressed as Amanat Khan as he achieves success from Shah Jahan) (see Figure 8). ‘Abd al-Haqq b. Qasim Shirazi (d. 1054–55/1644–45), received this title on 18 Urdibihisht 1041/8 May 1632. He was one of the Persians who had moved to India with his father and entered the Royal Court. Apart from his librarianship, he is also known for his involvement in the decoration of the Taj Mahal in Agra.

Figure 8. Imprint of the seal of ‘Abd al-Haqq Amanat Khan, Divan by Hilali, Ms King's Pote 186, Bukhara, 938/1531–32, f. 69v. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

Two other seal imprints with his name were made before and after his promotion. One reads: ‘Abd al-Haqq b. Qasim Shirazi [in the year] 1037/1627–28, and the other: Amanat Khan-i Shah Jahani, [regnal] year 5, year 1042 (1633). According to Manijeh Bayani, the impression of this seal has never been witnessed elsewhere.

Two extensive notes contain extremely valuable information.

One is anonymous, which mentions two illustrated folia; the other was signed by Muhammad Salih, who witnessed the transfer of the manuscript from Khwajah ‘Anbar to Mansur on 19 Rabi‘ I, the [regnal] year 24, i.e. on 12 March 1651. Although he does not mention any paintings inside the manuscript, he still registers the total number of folia as 66, which compared with the present number 63, means that three leaves are missing.

It is possible that it was the same Khwajah ‘Anbar who registered the acquisition by the same library of another manuscript under the supervision of Muhammad Mu'min [the superintendent] in 1628. The manuscript was a poetic Anthology also penned by Mir ‘Ali formerly in the collection of Oliver Hoare.Footnote 67

The first detailed description of the manuscript is neither signed nor dated and it is partly smudged; however, it contains very important information about its condition, as well as exterior and interior decoration:

The Divan of Hilali, large (kalan) vaziri size, margins in polychrome attached (vasli), bound with straps (tasma), in naskh-i ta‘liq (nasta‘liq), the name of the scribe is Mulla Mir ‘Ali, written diagonally (chalipa), ruled smoothly (mulavvah), binding of ornamented lacquer (rang-i rawghani) in polychrome (abru), composite (vassali), illuminated lacquer dubloures (astar rangi rawghani), paints peeled off (rang-rikhta), separated from gutter (az shiraza va-shuda), most leaves blemished (aksar kaghaz daghdar), with two illustrations (ma‘a du safha tasvir), 66 folia, price (qaymat) 300 [in siyaq] (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Librarian's note, witnessing that the manuscript used to have 66 folia, including two illustrations, lacquer binding, painted inside and outside, both leaves and binding in state of restoration. Divan by Hilali, Ms King's Pote 186, Bukhara, 938/1531–32, f. 64r. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

The second note was written by Amanat Khan's successor, Muhammad Salih on 12 March 1651:

The Divan of Hilali in the hand of Mir ‘Ali the calligrapher, sixty-six folios … dawlatabadi paper with gold speckles (zar-afshan-i ghubar), ruled smoothly (mulavvah), margins with polychrome illuminations and coloured paper with polychrome illumination, worm-eaten (kirm khurda), illuminated lacquer binding, most leaves blemished and stained (aksari awraq daghdar rasanida), several folia have their corners torn (chand varaq dar kinara para shuda). It was transferred from the custody of Khwajah ‘Anbar to Mansur on the 19th of the month of Rabi‘ I, the [regnal] year 24 (12 March 1651). The servant of the Court, Muhammad Salih, valued 300 (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Note signed by Muhammad Salih about the transfer of the manuscript from Khwajah ‘Anbar to Mansur on 12 March 1651, Divan by Hilali, Ms King's Pote 186, Bukhara, 938/1531–32. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

The same Khwajah ‘Anbar who registered the entry of the manuscript to the kitabkhana is mentioned in another note: dakhil… 4 mah-i Bahman sana 4 az vujuh… tahvil-i Khwaja ‘Anbar shud, qaymat 301, mujallad—‘It entered … from … being passed to Khwajah ‘Anbar on the 4th of the month of bahman (?) the [regnal] year 6 (24 January 1633), price 301 [rupees], bound’.

It is more likely that both inscriptions with the name of Khwaja ‘Anbar mention the same person who was the librarian of Shah Jahan, not the one who served in ‘Alamgir's royal atelier.

It is notable that another indication of a price of 303 [rupees?] is mentioned at the end of a much later note: ‘It was handed over to Murad Beg from the custody of Mun'im Beg on 5 Jumadi II, the [regnal] year 3’, which, according to Manijeh Bayani, refers to one of the rulers after Muhammad Shah (1702–48). This could serve as a proof of the minimal level of inflation in the book market during this period.

Muhammad Salih's inscription could be related to the imprint of a round seal with the name Salih: Salih bud banda-yi Shah Jahan 1056—‘It was Salih, the servant of Shah Jahan 1056/1646–47’. The same person could be mentioned in the seal impressions with the dates: 5 Sha‘ban 1060/3 August 1650, 1056/1646–47, and perhaps under the name Hakim Salih in the other seal dated 1053/1643–44.

According to Manijeh Bayani, this Muhammad Salih could be the inspector (mushrif) whose hand can be identified in at least 34 similar notes in various manuscripts. It is unlikely that it is Muhammad Salih [Kamboh Lahori] (d. circa 1675) who was meant here—the author of Shah Jahan's biography, which he had already finished when the emperor was dethroned by his third son Aurangzeb and kept under house arrest in Agra Fort. It is not impossible that the deposed emperor could have taken Hilali's lyrics produced by his favourite Mir ‘Ali with him in exile.

Another inspector called Muzaffar left a note on 6 Rabi‘ II, the [regnal] year 7. It is not obvious whose reign he meant here, which makes it difficult to identify the date. There is another note mentioning that the manuscript was placed in the custody of Muzaffar with the date of the first day of Shawwal [regnal] year 8, which could be 6 February 1666. If both notes refer to the same Muzaffar, they belong to the post-Shah Jahan period.

The next note could belong to the later ruler, also called Muhammad Shah, who reigned for 30 years: ‘It was put in the custody of Mun'im Beg on 7 Dhi qa‘dah (sic) of the [regnal] year 20’, which could mean 16 February 1739.

Margins

It is uncertain how the original margins looked. However, if both Mir ‘Ali's manuscripts—the Cambridge Divan and the St Petersburg Jung—followed the same fashion and had a similar decorative pattern, the margins of Hilali's Divan could have had the same simple decoration of gold speckles over thick creamy paper—similar to the main text panels as witnessed in the notes by the Mughal librarian in the seventeenth century.

It is quite possible that some original margins of plain ivory background covered with gold speckles could have been recycled to produce the margins for album leaves, like the one which is now in the Library of Congress: the dimensions of the folia in both Washington and Cambridge are identical.Footnote 68

The bayts on the Washington folia were inserted inside the frame and also signed by Mir ‘Ali and his very close pupil, Sultan Bayazid (d. 1578). His name is indicated under the fragment ascribed to Hilali, although none of those bayts could be found in his Divan. Another poem composed as tarjī‘band dedicated to a king (‘Ubaydallah or his son?), wishing him glory and health, is signed by Mir ‘Ali.Footnote 69

As is evident from the librarians’ witnesses, the margins of the manuscript when it arrived in the royal kitabkhana were in rather poor state: worm eaten, torn, badly stained, and generally seriously damaged. It seems that they were already handsomely illuminated. Its bad condition prompted its urgent restoration which was performed by replacing the margins. It is also possible that the binding was also restored. The new (current) margins were trimmed to fit the renovated binding as most likely they were made deliberately wider to be cut according to the final size of the binding (see Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11. Divan by Hilali, marginal illuminations, Ms King's Pote 186, Bukhara, 938/1531-32, f. 7r. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

Figure 12. Divan by Hilali, marginal illuminations, Ms King's Pote 186, Bukhara, 938/1531-32, f. 55v. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

At present Mir ‘Ali's manuscript of Hilali's Divan has striking wide margins, richly decorated with floral and geometrical arabesque patterns, as well as images of animals and birds, real and fantastic in polychrome. Both the margins and the lacquer binding have similar imagery, skilfully emulating Safavid motifs produced not only on paper,Footnote 70 but other media as well: lacquer bindings, ceramics of the mid-sixteenth to seventeenth centuries, and Kashan silk carpets, the closest of which would be the silk ‘Animal’ carpet from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see Figures 13, 14 and 15)Footnote 71 and the ‘Animals Fighting’ carpet from the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum.Footnote 72

Figure 13. Silk ‘Animal’ carpet, second half of the sixteenth century, Iran, Kashan (?), Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913, 14.40.721. Source: © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 14. Detail, Silk ‘Animal’ carpet, second half of the sixteenth century, Iran, Kashan (?), Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913, 14.40.721. Source: © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 15. Detail, Silk ‘Animal’ carpet, second half of the sixteenth century, Iran, Kashan (?), Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913, 14.40.721. Source: © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This fashion was still popular in Herat several decades later, as was the tinted paper, which can be seen in the Hermitage Layli va Majnun by Hatifi calligraphed by Mahmud Nishapuri in 1562 (VP-995), or in the Gulistan by Sa‘di, now in Kuwait in al-Sabah collection.Footnote 73 Of particular importance is the resemblance of the animals in the Cambridge manuscript to those from another Gulistan manuscript copied in Herat by Sultan ‘Ali Mashhadi in 1468–69,Footnote 74 such as cheetahs, lions, and gazelles, and especially the fantastic Chinoiserie dragons, qilins, phoenixes, and some sort of felines with flaming wings.Footnote 75

The decorative programme of the ‘new’ margins combines two styles: exquisite arabesque ornament in gold over a monochrome (black, deep and light green, dark blue) background on thick high-quality Oriental paper. Alternatively, the pattern of marginal and flyleaf illumination could have been based on a large floral designFootnote 76 drawn with liquid gold by a thin brush over tinted monochrome (dark blue, green, and greyish-turquoise) paper.

The second style has a very impressive range of various birds and animals, organised in groups and depicted in rather ‘realistic’ and humorous scenes: bears and monkeys fighting with maces in their paws; foxes watching the lions attacking a deer and bulls; birds of various kinds, floating in the sky; and supernatural creatures (dragons with flaming gold wings and splendid simurghs with long fluffy Chinese tails). Despite a variety of types of birds and animals populating the manuscript margins, they were obviously drawn using a particular set of cliched patterns, stencilled or pounced on tinted paper, reproduced and repeated in various combinations of composition and colour scheme.

Missing illustrations

It is also possible that the two (and only) illustrations now missing from the Divan could have been of the same nature as those two paintings that are still present in the St Petersburg manuscript, as in both manuscripts they would reflect the same generic idea of love reflected in the text.

Both of the paintings (see Figures 1 and 16) in the St Petersburg Anthology symbolise the universal idea of love and friendship with no difference to one's gender. Both depict loving couples reading poetry and drinking wine in a paradisiacal garden—one depicts it in spring, the other in autumn.

Figure 16. Anthology of Persian poets, calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, Bukhara, Dhu'l-Qa‘da 935/July–August 1529, C-860, A young man and a lady in the garden, f. 41v. Source: © Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, St Petersburg.

The protagonist, a young prince or poet, himself reads to his companion poetry from a safina (a miniature album of a characteristic oblong shape), which has calligraphically executed poetic specimens interspersed with pen drawings and paintings in polychrome, all framed by wide decorative margins in gold on tinted paper.

In the first miniature (see Figure 1) two young men are sitting by a shimmering stream under a cypress tree, a standard trope of a handsome and slender beloved. Their costumes are very similar in style—long sleeved underdress with a short-sleeved cardigan on top of contrasting colours with black collars. The companion in yellow and orange, overwhelmed by the beauty of the poetry and nature around, is offering a cup of wine to his friend. His belt is made of a long shawl while the ‘poet's’ belt is a very delicate thin metal chain with the gold joints of floral design. To emphasise that he has a strong connection with poetry, he is shown with two qalams hanging from his belt.

The second painting (see Figure 16) depicts another couple, this time the protagonist is the companion from the previous picture, and he is entertaining a young lady. The young man is dressed in the same red and orange underdress with a long yellow shirt on top, the belt made of a white shawl and a green hat under his turban. He has some additional elements in his costume this time: his turban is decorated with a large heron feather and it is he who now has a qalam hanging from his belt. He is sitting on a bending plane tree which looks rather autumnal, with its bright red and yellow leaves. He is showing his album to the girl whose dress is fully covered with gold and silk embroidery. She is offering him a large red fruit, most likely a pomegranate, which is often a metaphor for round, firm breasts. She is standing in front of him under the same cypress tree, resembling her slim, elegant figure, and a blossoming cherry symbolises her tender rosy cheeks, by the stream of running water full of ducks—as an allegory of gaiety and the flamboyance of carefree youth. The opening pages of the safina he is showing to the girl have a piece of calligraphy on one side and an ink drawing on the opposite, which might also mean a contrast between the two sides of the painting—spring cherry blossom behind the girl and an autumnal plane tree behind the man. The two paintings together would mean that love and friendship are eternal and universal, and it is very possible that they would be similar to those that are now missing in the Cambridge Hilali.

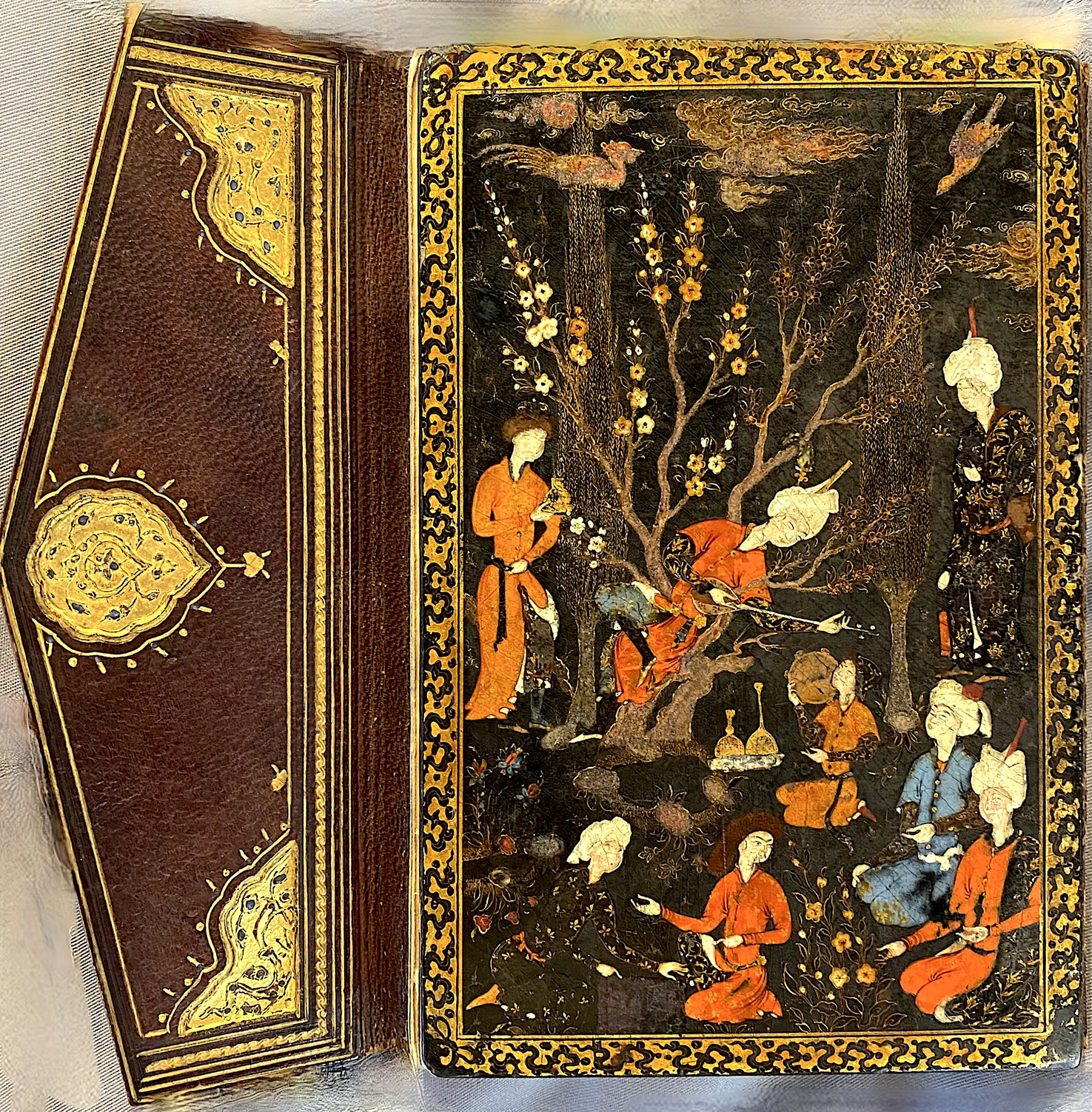

Binding

The binding is quite a mysterious concoction, which was most likely identified with a term ‘composite’ (see Figures 17 and 18).

Figure 17. Divan by Hilali, upper cover of Ms King's Pote 186, calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, Bukhara, 938/1531-32. Source: © King’s College, Cambridge.

Figure 18. Divan by Hilali, lower cover of Ms King's Pote 186, calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, Bukhara, 938/1531-32. Source: © King’s College, Cambridge.

The front outer cover depicts four pairs of animals engaged in a fight: a simurgh and a dragon, a qilin chased by a cheetah with a rock in its paws, and a cheetah-like qilin attacking the onager-like creature, both with fluffy tails. The scene is observed by two foxes or jackals and birds hiding among the leaves of the trees, with some large blossoms. The back outer cover has a similarly crowded scene of several pairs of animals engaged in the action: the upper central part is occupied by a group of two simurghs: one, carrying a hare, is trying to protect its prey from another, who is turning round ready for an attack. In the middle register two quoins are entering into a confrontation—they are very similar to those on the front cover: one looks like a cheetah and the other one like an onager, both with fluffy tails and fiery wings. In the bottom, a dragon and an onager-like qilin are already locked in a fierce fight. A startled fox, a hare running away, a bear, a bird hiding in the tree, and a stork flying away add more details to the visual narrative and an already quite a busy composition (see Figure 19).

Figure 19. Divan by Hilali, front doublure of the binding, Ms King's Pote 186, Bukhara, 938/1531–32. Source: © King's College, Cambridge.

The inner covers are produced with a similar technique and colour scheme, although this is more restrained in palette and action (see Figure 19). The composition imitates the traditional decor of leather bindings with a large central almond-shaped medallion, smaller ones below and above, and corner triangles with the frame of the same floral ornament. However, the space around the medallions is filled not only by the flowers springing out of the rocks but by the animals similar to those depicted on the outer panels; however, none of them are fantastic, they are all real cheetahs, onagers, and hares. Of particular interest is the pair where a cheetah is getting ready to attack an onager—the composition is identical to the one on the back outer cover, but the animals do not have wings and fluffy tails.

It is certain that in India, at least by 1662, it already had an illuminated lacquer binding as stated in the accompanying inscriptions. Perhaps it was similar to the lacquer binding which the Chester Beatty manuscript still has (see Figure 20).

Figure 20. Upper lacquer cover with embossed gilded leather flap of Guy-u Chawgan by Mahmud ‘Arifi, Herat, 934/1527–28, Per 194, binding. Source: © Chester Beatty Library.

This means that the original binding would be quite different to Mir ‘Ali's Jung from St Petersburg (C-680), which is covered with gilt embossed leather and has elaborate multicoloured leather and paper filigree doublures (see Figures 21 and 22).

Figure 21. Front cover of the binding, Anthology of Persian poets, Bukhara, Dhu'l-Qa'da, 935/July–August 1529. Source: © Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, St Petersburg.

Figure 22. Doublure of front cover of the binding, Anthology of Persian poets, Bukhara, Dhu'l-Qa'da, 935/July–August 1529. Source: © Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, St Petersburg.

Possibly, the difference was due to the size and layout of the manuscripts. The St Petersburg jung was designed to be used as it is shown on the two paintings illustrating its text: as a portable ‘pocket-size’ safina to entertain intimate friends, for example, in a garden. Its size is 22.8 × 12.5 cm (text 13.3 × 5.5 cm), which is much smaller than the Cambridge Divan: 33 × 20.6 cm (with margins), 17.5 × 9.6 cm (text).

When the manuscript was remargined its binding could be also restored. At the moment its outer covers are in a considerably poor state, worn with scratches and losses; however, its doublures are almost immaculate. Both sides of the covers are executed in the same technique of under-lacquer, almost monochrome gentle painting, produced by a very thin brush in various tints of gold ochre over the black background. Both have similar animalistic motifs.

It seems that the binding, namely its lacquer covers, are older than the margins. The similarity between the imagery on the covers and on the margins is striking. This could mean that the images from its covers were replicated to produce the new decorated margins.

It is possible that the covers of the original lacquer binding were split in half; in between the surfaces of the covers were inserted the panels made of leather, not of the usual papier-mâché, which is why such binding was called vassali (i.e. assembled, or composite).

It is also possible that originally the upper covers used to be inside and the inner ones were outside, but this is not certain, although the binding of the Cambridge manuscript looks very similar to that of Sa‘di's Gulistan, now in the Al-Sabah Collection. Gulistan's outer covers were ‘painted and lacquered, and the doublures were made up of the outer boards of another binding’.Footnote 77 The design of both outer covers of the Gulistan has similar imagery but with more energetic compositions.

Most likely the Divan was rebound for the last time already in Polier's atelier, when the manuscript lost its three folia with the paintings and the ‘unvan. There is still a question why the margins were made so large if they were specially produced to fit the refurbished binding: they were trimmed so drastically that they lost not only some fragments of the gazelles, qilins, simurghs, or dragons, but the pagination catchwords, if they ever were reinserted.

Why was the illumination of Mir ‘Ali's Divan of Hilali never finished?

In the colophon Mir ‘Ali mentions that his copy of Hilali's Divan is only a draft (taswid), although, according to the original design, the manuscript was supposed to have spaces allocated for illuminations. However, they are only found on the opening and the final pages. It is possible that Mir ‘Ali originally intended it to be of presentational quality but changed his mind, perhaps to avoid some risky associations with the executed poet, and added the note about its ‘draft’ state to be able to keep it for his own personal use. It is possible that from the very beginning the manuscript was planned to be sort of a ‘dry run’ to design the layout of a clean copy, which, however, has not survived, or was never produced.

Conclusion

The comparison between the three manuscripts written by Mir ‘Ali, which are now in Cambridge, St Petersburg, and Dublin, allow us to establish not only the fact that the Cambridge Divan of Hilali was produced in Bukhara, after the execution of its author, but also allows us to attribute the date of the siege of Herat by the Shaybanid Sultan ‘Ubaydullah more precisely: between the end of 1528 and mid-1529, which in medieval chronicles is sometimes reported with a disparity of up to two decades.

It also helps to establish the fact that Mir ‘Ali created his manuscript, which is the earliest surviving Divan of Hilali, not in collaboration with but in memory of his perished friend. Hence it determines that it was Mir ‘Ali's selection of his favourite poems by Hilali: his version contains only about one-third of the total number of poems (ghazals, ruba‘is, and qit‘as) compared with the critical edition published by Sa‘id Nafisi. Mir ‘Ali's selection would have had nostalgic associations with their beloved Herat and its milieu, lost for the calligrapher for the rest of his life in Bukhara. Although perhaps intended as a royal atelier production, it was later kept by Mir ‘Ali for his personal use, probably to avoid the risk of reminding the ruler of his unjust execution of the poet. However, his manuscript might possibly be the one that made ‘Ubaydullah repent.

It is possible that the Cambridge Hilali originally had its decoration programme similar to the Mir ‘Ali Anthology, which is now in St Petersburg, with two miniature paintings that are now missing in the Cambridge manuscript. They depict a loving couple, symbolising the generic idea of love and friendship. Although the illustrations were taken out of Hilali's Divan, they are mentioned in the notes on the flyleaves of the manuscript by the librarians of Shah Jahan's kitabkhana. By the time the manuscript entered Shah Jahan's atelier, it already had richly illuminated margins which, however, were seriously damaged. It is very likely that they were replaced by those with a number of clichéd images of real and supernatural beasts and birds.

It is possible that the imagery for the margins was borrowed from the binding, which seems to be an earlier production, or that the binding was contemporaneous with the manuscript, which prompted the decoration programme of the new margins, inspired by the imagery on the binding as well as different objects produced in other media of the same period.

Each double page opening has its unique marginal decoration which helps to identify any disturbance of the page order. Mir ‘Ali also used another way to determine the page order by dividing one poem between the two pages, which could be the result of his life-long experience of working in a court atelier, anticipating that the manuscript could be rebound and the leaves would lose the catchwords.

Most likely the Divan lost its illustrations when it was rebound for the last time in Polier's workshop in the middle of the eighteenth century before it arrived in Cambridge as part of Pote's donation.

At present the manuscript looks as it was described almost 400 years ago: the outer covers of the lacquer binding are seriously scratched, the folia are detached from the gutter in several places, and the text blocks of some leaves are falling out of the margins in places along the jadval rulings. It is time for another restoration of this important monument of the shared cultural history of Central Asia, Persia, and India. Such treatment, using contemporary equipment with a proper conservation survey such as was undertaken by a group of colleagues for the St Andrew's Qur'an,Footnote 78 revealing its Indo-Persian history, would be the best way to solve the remaining enigmas of the Cambridge Hilali.