I only began thinking about furniture in Gandhāran art after seeing carved architectural pieces by the roadsides in Pakistan. It was in the mid-1980s; I was in Islamabad and Swat. Pakistanis were at that time transforming or exchanging their traditional masjids (mosques), fronted by colonnades of intricately carved pillars for concrete or brick exteriors. In some cases wooden mosques were demolished and replaced by structures using more efficient load bearing materials; in other cases, exposure to moisture rendered wooden roofs and pillars unstable and as a result wooden pillars rested on Islamabad's sidewalks ready to tempt prospective buyers; their decorative intricacy and appeal was immediate.

It was not difficult to think of the ancient past when great forest wealth existed in the mountains of northern Pakistan. In antiquity until more recent deforestation, the northern mountain system, including the forests in the Hindukush, the Himalayas and the Karakoram, provided rich material for making architectural sections and furniture. Himalayan cedar was and still is popular. For legs of chairs, stools and beds—the subject of this essay—“the harder woods of evergreen oak and olive” were also used.Footnote 1 In the 80s when I was involved in analyses of contemporary textile patterns and their possible historical antecedents, I made a mental note to explore the possible relationship between ancient and modern woodcarving designs as well.

The theme of this paper was thus conceived decades ago. I made a preliminary much abbreviated report in 2014, at the Stockholm meeting of the European Association for South Asian Art and ArchaeologyFootnote 2 but in the meantime I had analyzed and published several papers on Gandhāran textilesFootnote 3 and suspected that patterns and forms in woodcraft would likewise indicate an indigenous craft. Without divulging particulars that follow, shapes and designs of textiles are more indigenous, whereas I have found that wooden legs attached to chairs, stools and bedsteads relate more to foreign types.

Illustrations of Gandhāran textiles are mainly in Buddhist narratives where they occur as carpets. There is thus no way of knowing if carpets were employed by local folk in antiquity, but given the cold winters in mountainous regions, woollen blankets, coverings and carpets were most probably is daily use.Footnote 4 Likewise ordinary households in antiquity could have had rudimentary furniture (though I am uncertain about its decorative nature). Dense wooded regions of the Hindukush, Himalayas and the Karakoram offered the possibility of producing wooden home furnishings, especially in Swat and regions throughout the Hindukush, and the long winters would allow ample time indoors to carve furniture.Footnote 5 Today, traditional Swati households are filled with carved chairs and beds, chests, stools etc. (a situation quite unlike other Eastern lands where activities such as sitting and sleeping can be done on the floor). In Kuṣāṇa times, furniture depicted in Gandhāran royal and Buddhist art was, it will be shown, heavily dependent upon complex foreign shapes and motifs. It would seem that there was a dearth of intricately carved, heraldic motifs, in the local Northwestern culture to draw from.

The current paper is my second study on Gandhāran furniture; the first, published in 2006, provided a discussion of the two main forms of furniture legs and the basic design of each form. The origin of these forms and their decorative variations has not yet been investigated. This is the topic of the present paper. The aim is to trace the origins of the shapes and the decorations mainly of Kuṣāṇa wooden legs attached to chairs, stools and beds as seen in Gandhāran sculpture. Thereby this is the first assessment of the different sources and shapes accounting for a selection of early Gandhāran furniture as well as their subsequent impact on regions beyond. That is, where it is possible to broadly indicate subsequent furniture designs influenced by models shown in Gandhāran art, the post-Kuṣāṇa examples will be mentioned.

I. Defining Two Types of Decorated Furniture Legs

The two distinct forms of Gandhāran furniture legs dating to the Kuṣāṇa Period are: 1) the Figurative Type and 2) the Geometric Type. The Figurative Type features anthropomorphic and theriomorphic forms. Geometric Type features rings, cylinders, globes and hemispheres arranged in sequentially numerous ways, seemingly impervious to a chronological rationale.Footnote 6 Even though these types have been outlined in the previous 2006 work, for the sake of a smooth transition into the subject of the present work, the characteristics of each will be outlined anew below.

A. The Geometric, lathe-turned, type of Furniture Leg.

A clear example of this Type is illustrated by the throne legs in a scene depicting a kneeling man in front of an enthroned ruler (Fig. 1). The greenish grey schist relief (14 x 30 x 5.5 cm) is in the Peshawar University Museum; Footnote 7 it comes from Charg Pate, Dir and dates c. second or third century ce. An orderly sequence of the geometric shapes on this throne leg can be easily followed: starting from the top, ring, globe, hemisphere, cylinder and ring. The shapes establish a neat vertical outline; only the hemisphere extends slightly beyond the invisible vertical line (causing some to call this form “bell-shaped”), and the cylinder is narrower, being thin and tube-like.

Fig. 1. Regal Scene. Gandhāra. Photo, after Gandhāra. Buddhist Heritage. Cat. No. 115.

I have purposely chosen this example in order to illustrate the noticeable resemblance of the Gandhāra legs to those on a reconstructed free-standing bronze palanquin (or litter), [based on ancient representations of litters] which is both illustrated and described in a catalogue of ancient sculptures in Rome (Fig. 2).Footnote 8 The Catalogue compares this object, including the feet, to a “bronze couch or bed of Graeco-Roman type” (seen in plates 62 and 63 of the Catalogue) probably of “Graeco-Asiatic origin”. The Catalogue states that the legs of the couch suggest “turned wood-work. The bronze castings are hollow and had a wooden core”. The Graeco-Roman legs of the bronze palanquin have the following sequence, again starting from the top: larger ring, smaller ring, compressed globe, two rings, narrow cylinder, hemisphere extending slightly, tapered cylinder on base ring. The Roman palanquin is assigned to the period of Augustus; it was found on the Esquiline. Other South and Central Asian examples and comparisons to the Geometric Type are discussed in Sections III - V.

Fig. 2. Reconstruction of an ancient representation of a Roman Palanquin. Drawing after A Catalogue of Ancient Sculptures Preserved in the Municipal Collection of Rome (see fn 8); Plate 64.

B. The Figurative Type

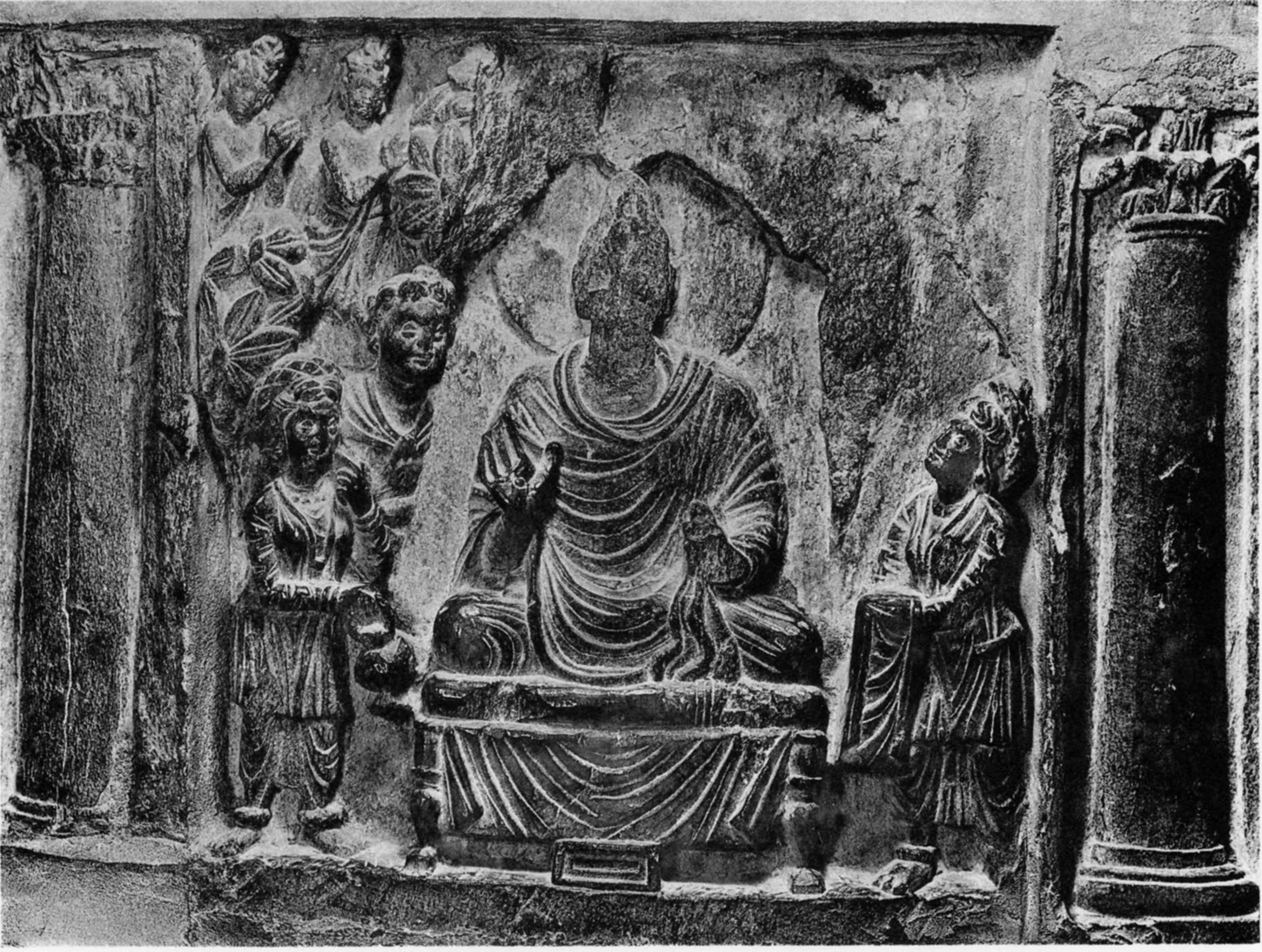

This type of leg is carved, not lathe-turned. Initially two animals, or parts thereof, dominate: the lion and the elephant. Martina Stoye's study of the tripod in Gandhāran scenes of Siddhārtha's First Bath demonstrates the use of figurative types in the table's three legs. The lion predominates. A simple tripod shows the three legs in the shape of the lion's paw. An unusual combination of lion's paw topped by the lion's head appears as a more ornate type of leg in some scenes of the First Bath (Fig. 3). Stoye is able to show that the source for this particular type of furniture leg is Rome. Basing her findings on a previous work, a dissertation on Roman Marble Tables, she concludes: “It must have been shortly before the first half of the first century bce that a table leg with a lion's paw and protome was developed, probably in neo-Attic workshops”.Footnote 9 [This gives a good terminus a quo for the earliest possible date of Fig. 3]. A different combination, namely the lion's paw and the elephant's protome is seen in a Parinirvāṇa representation that comes from Swat (Fig. 4).Footnote 10 This relief is now in the Peshawar Museum (Inv. No. PM 2826).The Buddha's bedstead is supported by legs with this composite whose sculptural quality was probably achieved by the hand of a probable Swati carver. A cube with floral design rests on top; it probably contained the mortise joints affixing the entire ‘order’ to the bed's plank. The lion's paw/elephant's head leg may also reflect Roman influence. The British Museum displays a Roman bronze leg of a couch dating to c. first century ce (Fig. 5; GR 1896.5 - 18.28). This furniture leg (7.5 inches ht.) has elements seen in Gandhāran art and beyond. The lion's paw is the base; the elephant's head accentuates the eyes; the skin of the trunk hangs loose between the tusks; large ears are rendered on this example, and a kind of netting covers the front. This sort of netting is seen on other Roman elephants dating to this early period. By the second and third century, elephants are common on Roman sarcophagi due to the cult of Dionysos.Footnote 11

Fig. 3. First Bath of the Buddha – to – Be. Photo after Ingholt, No. 16.

Fig. 4. Parinirvāṇa, Guides’ Mess. Peshawar Museum No.1084. Photo after Srinivasan, “Local Crafts”, Fig. 11.

Fig. 5. Roman elephant couch leg; bronze. c. 1st century ad. British Museum No. GR 1896.5–18.28. Photo courtesy of The British Museum.

How did Roman conventions succeed in surfacing in Gandhāran furniture?

II. A Brief Account of the Penetration of Western Influences into Gandhāra

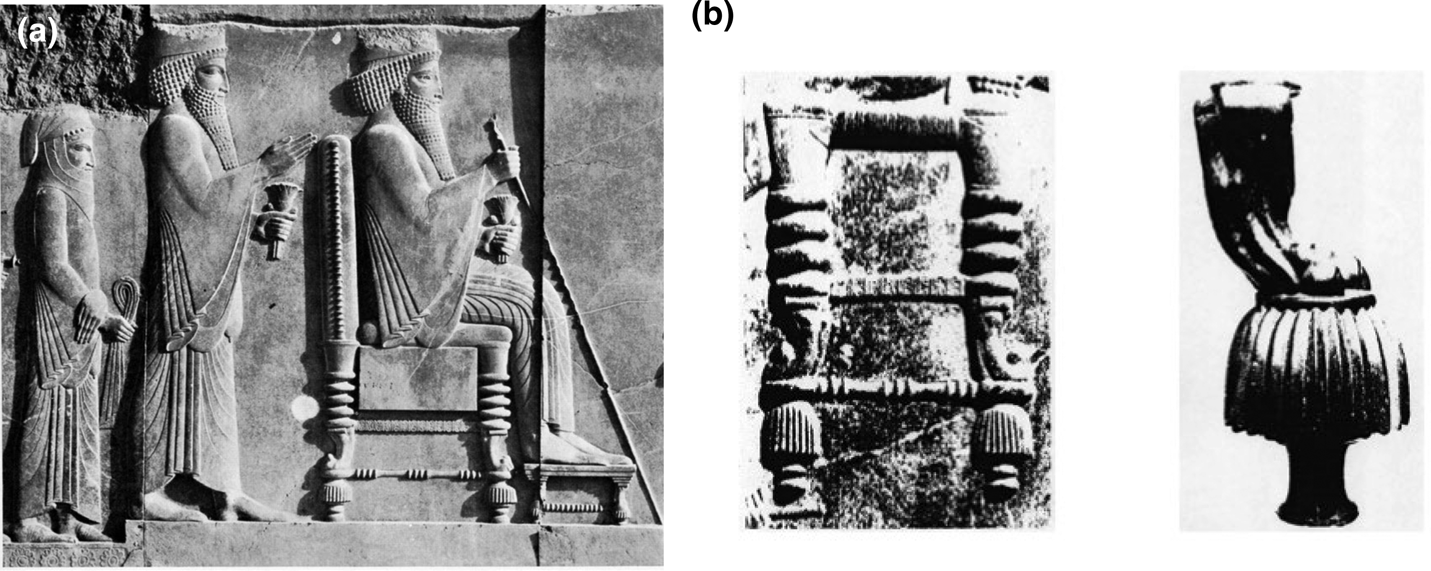

Actually, the Romans themselves may not have been the original source of the lion's paw at the base of furniture legs. How this shape eventually came to the northern regions of Pakistan and appeared in Gandhāran furniture necessitates tracing the region's long exposure to foreigners coming through its western borders. The paw was already prominent in Persian royal furniture. Reliefs on the Apadana at Persepolis, capital of the Achemenians sixth to fifth century bce), depict a throne and stool legs with a lion's paw between rings and cylinders on top and falling leaves (Fig. 6a and b). Achemenid furnishings communicated status and might, thus influencing regions they conquered. According to Paspalas, who made an extensive analysis of Achemenid throne legs and their transmissions,Footnote 12 the Persians made Gandhāra a satrapy of their Achemenian Empire but there's no record of furniture that early in Pakistan. After the Persians, Alexander ventured into Greater Gandhāra in the fourth century bce and established cities to the north of Gandhāra proper. Alexander's Eastern successors, the Seleucids, continued the Greek influence in the northern regions. In the region called Bactria in antiquity (northern Afghanistan today), excavations at Aï Khanoum uncovered a Greek town, probably a frontier town. It had seceded from the Seleucids and became a kingdom in c. 250 bce. Aï Khanoum revealed many characteristics of Hellenistic art and culture, some pertinent to our discussion and to be described below. When Aï Khanoum was overrun by Central Asian nomads in about 145 bce, the Greeks and the philhellenic population of Bactria fled southward to Gandhāra. Some settled in Sirkap which became the Indo-Greek city at Taxila, below the Hindu Kush, founded in the second century bce. Excavations unearthed Hellenistic affinities with important implications for furniture styles. After Sirkap, Taxila continued to flourish during the Kuṣāṇa Period due in part to its location on major pathways. Taxila lay on the important trade route, the Uttarāpatha, which connected the Northwest to Gangetic India; Taxila also was connected to the Karakoram route going from the North (i.e., Bactria, Gilgit) to the South; an overland route went East to West, from Persia via Taxila toward the subcontinent. The Parthians came from the latter direction in the mid-first century ce and within the same century there came the Kuṣāṇas, slowly conquering their way into the subcontinent. These foreigners were responsive to furniture models expressing authority. Movement also occurred between Gangetic India, especially from Mathurā, and the northern area. Active trade existed between Gandhāra and Mathurā.

To this influx of peoples, and their influences, can be added the Romans whose contact with South Asia was via trade. Roman influence could have come from two different directions. A Roman treasure was found at Begram in present-day Afghanistan. Begram is on an overland route connecting with the Uttarāpatha; alternately a sea route passing through the Red and Arabian Seas and then connecting with the Uttarāpatha could continue Northward to Begram.

The date of the Begram treasure was based on analysis of glass remains.Footnote 13 The study concluded that Roman decorative arts at Begram probably date from between the first and early second century ce, coinciding with a period when Gandhāran art was flourishing. The other way that Roman objects would have sporadically reached the Northwest was via Northern India. Roman trade could have reached ancient seaports on India's western coast. Barygaza (in present Gujarat) and Muziris in Kerala were major Indian ports. From there, traders could have brought or sent objects farther North and ultimately to the Northwest or Gandhāra. The fact that a Roman amphora handle was found in an excavation at Ambarish Tiḷā, Mathurā, signifies that the Roman wine trade went North into the Doab, and we know that goods travelling on the Uttarāpatha linked Mathurā and the Gandhāran region.

In sum, many different entry points existed for foreign designs to enter Gandhāra and influence the repertoire of local craftsmen.

III. Entrance of the Geometric Type of Furniture Leg into South and Central Asia

A. Gandhāra, Pakistan and Greater Gandhāra including Afghanistan and Turkmenistan

It is not hard to explain the appearance of a throne with Geometric Type legs on a Bactrian coin in the second century bce (Fig. 7). Agathocles, king of Bactria, c. 170 bce issued this coin commemorating Alexander the Great, who called himself the son of Zeus. The reverse of the coin shows Zeus seated on a throne whose legs have multiple ring mouldings, tapering globes and cylinders (British Museum No. 1880, 0501, 2). Alexander came from Macedonia which was affected by Persian contact including the Persian Wars. Paspalas reports on a royal excavation at Pella, Macedonia which yielded three kline furniture leg casings probably made in the Achemenian empire. Kline is a Greek term for a certain form of a couch. Romans continued to make and use the kline. The legs (dating to end of fourth or early third century bce), show elements of a geometric sequence, namely concave and convex ring mouldings above a drooping wreath of leaves (Fig. 8).Footnote 14 In essence, a leg form influenced by the Persian style came to Greece, wherefrom, in turn, the style could have been reintroduced in the East when the Greeks, the successors of Alexander's conquests, settled in Aï Khanoum. [This historical development may explain another furniture motif; please see VI. A.4]. Actual segments of an ivory throne were found during the excavation at Aï Khanoum (Fig. 9). When the segments of the leg were reconstructed, it resembled the classical Greek type of leg but somewhat more elaborate. Likewise, ivory throne legs resembling the Aï Khanoum ones were found during excavations at Nisa (early capital of the Parthians, in Turkmenistan today); see Fig. 9. The excavators date the Nisa findings to c. second century bce. Both the Nisa and Aï Khanoum legs display a lower form above the base having a bell-shaped moulding, which may be imitative of the drooping leaves, on the bottom of an Achemenian throne chair. A very similar foot was also found in an excavation of the Parthian Period at Frehat En-Nufegi. Such bell-shaped mouldings are also attested in both Hellenistic Greece and Rome.

Fig. 7. Bactrian Coin of Agathocles; reverse with Zeus on throne. Photo, after Gandhāra. Buddhist Heritage; Cat. No. 4, p. 88.

Fig. 8. Kline Furniture Leg; Pella; photo after Paspalas, Fig. 1.

Fig. 9. Ivory Furniture legs from Nisa and Aï Khanoum photo, after Bernard, ”Sièges”, Figs, 1, 2 and 7.

Sirkap absorbed the eastern expressions of Hellenism and adopted the fancy footwork that developed in Bactria (Aï Khanoum) and Parthia (Nisa).Footnote 15 A slender version in ivory of a throne leg was excavated at Sirkap (Fig. 10). Its globular form shows the trace of acanthus leaves which can also be discerned on the Parthian Nisa ivory legs of both the Geometric and Figurative Types (Fig. 10 for the Figurative example). The geometric order is likewise on Sirkap toilet trays. A good example represents a personage reclining on a kline in a banquet scene (Fig. 11). It is from the Karachi Museum (No. 195/1932-33). The kline is raised on legs composed of an arrangement of geometric forms: ring-shaped mouldings, bell-shaped hemispheres and tapered cylinders.

Fig. 10. Ivory throne leg from Sirkap; photo after Marshall, Taxila, Pl. 210h. It is compared with Nisa ivory throne legs shown in Bernard, “Sièges”, Fig. 3.

Fig. 11. Geometric type furniture legs on Sirkap toilet tray; photo after Ingholt, Gandhāran Art in Pakistan, No. 488.

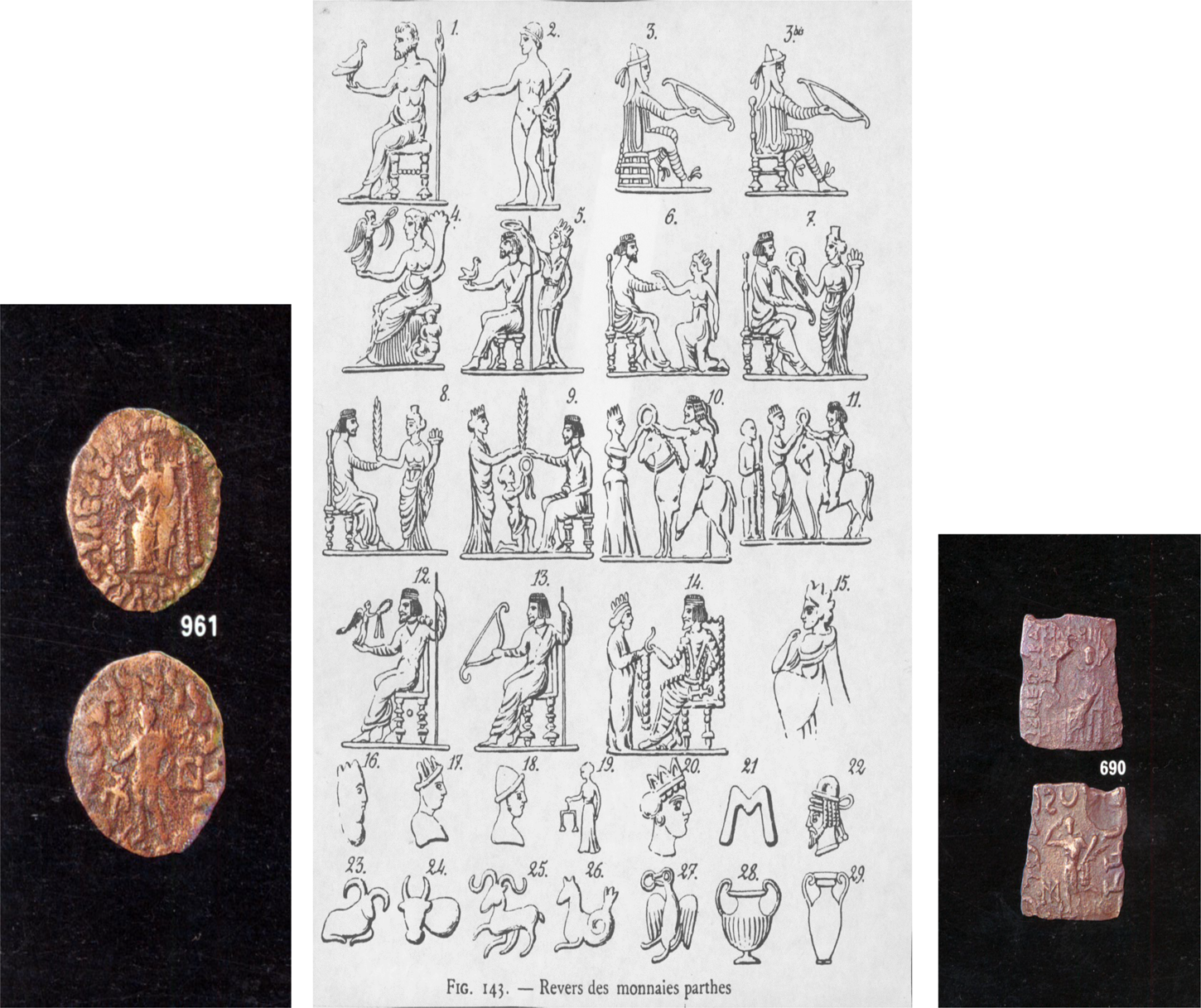

Beginning in the first century bce (on a Maues coin; Fig. 12 # 690) through to the early-first century ce (on an Azes II coin; Fig.12 # 961) Indo-Scythian coins showed, on the obverse, a sturdy geometric leg in enthronement scenes. On a coin of Maues, Zeus is seated on such a throne, and on the Azes II coin the City Goddess is seated on such a throne. Around the same time, Parthian coins have this sort of throne leg (Fig. 12, in the centre - chart 143, Nos. 6, 8,9,12 - 14). A type of furniture more often appearing on Parthian sculpture is the Kline or banquet couch. This type of couch is common in funerary banquet scenes, for example at Palmyra. The couch or bedstead upon which the deceased reclines is supported on legs composed of geometric forms; by the second and third century ce, they have elaborate modifications. Instead of thin cylinders, the legs include tapered V-shapes and nearly all the geometric components are completely covered with a petal design.Footnote 16 These elaborations probably reflect the prevailing Roman taste of the time. The reason to take note of Palmyrene decorations on bedsteads in funerary banquet scenes is because we know, from previous studies, that Parthian developments, as seen in Palmyrene funerary reliefs, had an impact on Gandhāra representations. Parthian funerary reliefs were a source affecting Buddhist iconography in Parinirvāṇa scenes.Footnote 17

Fig. 12. Maues Coin Photo 690 and Azes II Coin Photo 961 after Bopearachchi and ur Rahman, Pre-Kushana Coins in Pakistan, 1995; pp. 166 and 196. Parthian Coins after Jacques de Morgan, Manuel de Numismatique Orientale de L'Antiquité et du Moyen Âge, Obol International, Chicago (1979) (1923), Fig. 143.

Parthian banquet scenes do not seem to have had an impact on Buddhist Parinirvāṇa scenes to the South, in what is now India proper.

B. India

Bhārhut and Amarāvatī exhibit lathe-turned legs on thrones and bedsteads, but it is generally agreed that these neither had influence upon, nor came from, Gandhāra. Legs that have some resemblance to the Northern Geometric Type seem to appear first at Mathurā, to judge from one Kuṣāṇa Parinirvāṇa example, although Sāñchī Stūpa does depict a throne with lathe–turned legs but they do not directly resemble the Gandhāran geometric style.Footnote 18 It is quite clear that the legs have neither the variety, decorative originality, nor execution of those from the North. However, two throne legs, on two different scenes on a balustrade from Mathurā's Bhūteśvar Stūpa, indicate a simplified type of lathe-turned geometric leg as found in pre-Kuṣāṇa Gandhāra (and reflecting Graeco-Parthian influences). The type seen on the Mathurā balustrade may possibly have come into the Gangetic valley from the North.Footnote 19

C. Advent of the Kuṣāṇa Geometric Type throne leg

Finally, we can date the implantation of the lathe–turned leg with its distinctive assemblage of geometric forms—rings, hemisphere, cylinder, globe—by the second century ce (if not before). On the double dinar issued by emperor Vima Kadphises (assumed to be c. 120 ce), the third emperor of the Kuṣāṇa dynasty sits on a high throne supported by legs of the Geometric Order and rests his feet on a footstool (Fig. 13).Footnote 20 The importance of this numismatic image is twofold: it provides a useful relative date for the circulation of the geometric style leg in the North; it also marks the Geometric Type of leg as an appropriate support for a royal throne. Buddhist iconography, when portraying the life of the Buddha, had need of decoration that signified a field of honour, a royal zone, and we may suppose that the elements comprising a Kuṣāṇa royal throne would inspire some sort of adoption into Buddhist imagery.

Fig. 13. Double Dinar. Obv. Vima Kadphises seated on throne. Photo after Gandhāra. Buddhist Heritage; Catalogue No. 88, p.149.

The connection between royalty and the Buddha is so well known that it barely needs repeating: entering his mother's womb in the form of a six-tusked elephant; born into a petty royal family; taking seven steps upon birth to proclaim spiritual sovereignty over all the worlds, enjoying the privileges of royalty prior to renunciation, requesting burial fit for a cakravartin or Great Ruler. Each of these events (and there are others), is tinged with evocations of royal status and power. Verardi Footnote 21 concentrating on just one of the storied events in the Buddha's last life on earth—his descent into the womb of his mother—itemises the many ways in which the elephant is a symbol of royalty: it is one of the seven treasures of a cakravartin; Indra, king of the gods has the elephant Airāvata as his mount. White, Verardi claims, is a royal colour and Trautmann adds that the white elephant “had immense value among Buddhist kingdoms”. Footnote 22 The six tusks of the elephant may further underscore dominion over phenomenal regions, as I agree with Verardi that six can refer to the directions of space, when the zenith and nadir are added to the four terrestrial directions.Footnote 23 It is hard to know whether indeed the six tusks—or white—were imbued with those meanings in the Kuṣāṇa age. But the need to introduce royal symbols into the imagery pertaining to the Buddha's life seems indisputable.

The fact, then, that a Kuṣāṇa emperor's throne features the Geometric Type of leg could have influenced the use of that type of leg in Gandhāra's illustrations of the life of Buddha, a spiritual king.

And it did.

Buddhist art seems to differentiate between the furniture of those participating in the life of the Buddha and ordinary people. One comparison will need to suffice because there are so few examples of the latter in Kuṣāṇa Buddhist art. Butkara I depicts a plain bedstead on which lies a corpse in a scene representing the Bodhisattva's first experience with death (Fig. 14). In contradistinction, note the way the bedstead of Buddha is depicted in the Swat representation of his Parinirvāṇa (Fig. 4) which shows the ornate Figurative Type of furniture leg, and (Fig. 15) a third century Gandhāran relief of the Parinirvāṇa showing the Geometric Type. Parinirvāṇa scenes in the Butkara I volumes, some of which are in poor condition, show ornate rather than plain legs for the Buddha's bedstead.Footnote 24

Fig. 14. Siddhārtha's First Experience with Death. Photo after Butkara I, II.2, Pl.CCLXXXIV.

Fig. 15. Parinirvāṇa. c. 3rd century ce. Photo courtesy Asian Art Museum, Berlin (Acc. No. I 80).

To push the evidence from Butkara I further, the reliefs from this site give a good preview of the themes in the life of the Buddha employing a royal throne, seat or bedstead and the legs on such furnishing; they include the bridal palanquin, with geometric moulded legs, carrying Yaśodharā to prince Siddhārtha (Pl. LXI Inv. No. 4016); Asita's prediction given to Queen Māyā and King Śuddhodana seated on a throne, with Geometric Type moulded legs (Plate LXIII Inv. No. 4276); the Great Renunciation, featuring Yaśodharā and Siddhārtha on a bed with (rather crudely delineated) Geometric Type moulded legs (Plate CDLX Inv. No.V.56);Footnote 25 Adoration of the Buddha seated on a throne with Geometric Type legs (Pl. CD Inv. V. 203); Adoration of the Buddha's Relics, placed on a throne with Geometric Type moulded legs (Pl. CCCXCVII Inv. No. 87; see a).

I do not wish to imply that at Butkara I, or elsewhere, ornate legs always appear in a narrative on the life of the Buddha. Quite a number of examples exist where the Buddha is seated on a plain low based throne at Butkara I, but here they may be formulaic renderings of the Buddha surrounded by worshippers; also these types of legs can occur in themes only indirectly related to the Buddha.Footnote 26

A general survey follows giving the contexts for the moulded Geometric Type leg in Gandhāran art. This survey is meant to be an indicator only. After having consulted over ten excavation reports and major catalogues for Gandhāran art, it has become evident to me that the contexts for the Geometric Type leg are circumscribed, rather well-defined, and in well-known contexts. [Already many have been noticed in Butkara I, above]. I therefore deem it better to list one example for each context rather than attempt some sort of near—comprehensiveness for a given context—which seems to me laboriously impractical, and nearly unfeasible. Examples seldom reproduced are illustrated. Below, in footnote number 27 are listed the volumes consulted for the survey.Footnote 27 In addition, I comment whether or not I see any correlation between a given example's legs and J. Ebert's Chronological Table for the Progressive Development of the Geometric Type (Fig. 4, p. 96 in her Parinirvāṇa). Ebert's Table tries to establish a stylistic and chronological development for the geometric type furniture leg. My findings (below) are at variance with most of the progressions shown in this Table. The reasons may be twofold. For one, Ebert postulates a linear stylistic progression. For another, the chronology of Gandhāran art may need to be viewed from a different—and new—perspective. A recent paper by Juhyung Rhi argues convincingly what I too am beginning to suspect, namely that Gandhāran art (he limits his analysis to Gandhāran Buddhas), probably developed in different regions along different trends, and the art probably did not develop in a single linear fashion.Footnote 28

IV. Overview of Selected Reliefs showing Gandhāran Furniture with Geometric Type legs

1. Māyā's Dream (British Museum OA1932.7 -9. 1; see Zwalf # 141). The bed's legs are turned: 3 rings are on top and below are lion's paws. This design is not noticed in Ebert's Table A. It seems to be related to combinations seen in Achemenian types (see Fig. 6). For other examples of legs with rings on top and lion's paw below see Gandhāra Catalogue, curated by Jansen and Luczanits: Fig. 3 detail of # 131 p. 167, and Fig. 1 detail of # 219, p. 180.

2. Interpretation of Māyā's Dream (Peshawar Museum No. 2067; see Ingholt: # 12). Legs of the king's throne are a little like Ebert's “Dekadenz-Zeit” (which is in a wrong timeframe since the relief is earlier).

3. Pleasures of the harem. Fig. 16 (Islamabad Museum. No. CL

Fig. 16. Pleasures of the Harem. Islamabad Museum. Photo after Gandhāra. Buddhist Heritage. Catalogue No.154.

07 IG 0903 Gandhāra Catalogue, Jansen and Luczanits No.154, p. 221). Buddha and companion are seated on high chair with geometric legs, unlike any in Ebert's Table.

4. Palace Life (The Seattle Art Museum, Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection 39.34; Kurita 124, p. 62). Bodhisattva and wife seated on throne in upper relief. Geometric legs unlike any in Ebert; legs on royal couch in lower relief somewhat like Ebert's “Dekadenz-Zeit”.

5. Great Departure – middle scene. Fig. 17. (From Russek, p. 44, # 39). Yaśodharā reclines and the Bodhisattva sits on a draped bedstead with Geometric Type legs having some resemblance to Ebert's last group “Verfalls-Zeit” which, to my mind, conflicts with the accomplished carving.

Fig. 17. The Great Departure; middle scene. Photo after Russek, Gandhāra. Cat. No. 39.

6. The Bodhisattva between Brahmā and Indra; (British Museum OA 1890.11–16.1. see Zwalf # 172). The Bodhisattva sits on a low throne whose legs are like those noted in No. 1, Māyā's Dream.

7. Pensive Bodhisattva. Pānṛ 718. (Fig. 18). He sits on a dais whose leg could approximate Ebert's Reife-Zeit ‘e’ or ‘f’.

Fig. 18. Pensive Bodhisattva. Pānṛ No. 718. Photo courtesy of the Museo della Civilta – Museo d'Arte Orientale, Rome.

8. Taming of the white dog that Barked at the Buddha. Nimogram, Gandhāra, Dt. Swat. NG 412 Part of UW - Madison digital library collection. (Fig. 19). Photograph and copyright: Joan A. Raducha. Dog is on raised platform having Geometric Type legs. (For the same theme, see Foucher, L'Art Greco-Bouddhique, Fig. 257b)

Fig. 19. Taming of the White Dog that barked at the Buddha. Nimogram (NG 412). Part of UW –Madison digital library collection. Photo and copyright: Joan A. Raducha.

9. Buddha Preaching in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven (Lahore Museum, the Sikri Stūpa; see Ingholt:# 104). Buddha sits on low support having legs not like any in Ebert's Table, (although they could be a modification of her “Frühzeit” which would be chronologically accurate).

10. Worship of the Buddha's Turban (Peshawar Museum No. 2064; see Ingholt # 50). Legs of the turban's throne are like Ebert's “Frühzeit” which seems right. See also Kurita, Nos. 169, 170, 172, pp. 92 - 93 for same theme on throne with Geometric Type legs.

11. King Udayana Presents the Buddha Image to the Buddha. Fig. 20. (Peshawar Museum No. 1534). The teaching Buddha sits on a low throne whose legs, of four rings each thicker than the preceding, are unlike any in Ebert.

Fig. 20. King Udayana Presents the Buddha Image to the Buddha. Peshawar Museum No. 1543. Photo after Ingholt, No. 125.

12. Buddha and Female Worshippers. (Karachi Museum, No. 320; see Ingholt #189). Legs are unlike any in Ebert's Table.

13. Courtesan Āmrapālī presents the Buddha with a Mango Grove. Fig. 21. (Lahore Museum, Sikri Stūpa). Legs of the Buddha's low throne are of different thickness and not like any in Ebert's Table).

Fig. 21. Courtesan Āmrapālī presents the Buddha with a Mango Grove. Sikri Stūpa. Lahore Museum. Photo after Ingholt, No. 136.

14. Parinirvāṇa (see Fig. 15).

15. Monks surrounding the Buddha's Coffin raised on a cushioned platform placed on a base. Fig. 22 (Private Japanese Collection). Throne legs are unlike any in Ebert's Table.

Fig. 22. Buddha's Coffin. Private Japanese Collection. Photo after Kurita, Gandhāran Art I, p. 235.

16. Guarding Buddha's ashes in an urn on a throne. (Peshawar Museum, No. 1319 C; see Ingholt # 158). Legs of the throne are unlike any leg in Ebert's Table, although they could be a modification of her “Frühzeit” which seems incorrect because the modelling of the relief seems later.

17. Distribution of the Relics (British Museum OA1966.10–17.1; see Zwalf:#232).The sacred stand has legs composed of all the geometric shapes (ring, broad cylinder, vase shape, flattened globe tube-like cylinder), yet the sequence is not in Ebert's Table, though perhaps closest to her “Reife-Zeit”.

18. Worship of the Buddha's Bowl (Chandigarh Museum Catalogue No.2225, page 111. Bowl is on a stand with Geometric shaped legs, but unclear photo.

19. Maitreya in the Tushita Heaven Fig. 23. Private Collection (From Russek: p. 72, No. 79). Maitreya sits on draped low throne with Geometric Type legs that are hard to liken to Ebert's examples. Victoria & Albert Museum No. 340- 1907, has Maitreya on Cushioned Dais with elaborate textile and Geometric style legs.

Fig. 23. Maitreya in the Tusita Heaven. Private Collection. Photo after Russek Gandhāra Cat. No. 79.

The overarching appearance of the Geometric Type legs on furniture in Gandhāran reliefs points to narrative scenes in the life of the Buddha and the Future Buddha. One may speculate that they help to establish the exalted space for those persons or items associated with the Buddhist legend. Kuṣāṇa coins indicate that thrones of other deities retained the Geometric Type of legs as well. Ardoxsho seated on such a throne may be found on the dinar of Vāsiṣka c. 3rd c. BM 1993.5.6.31 (see No. 55.p. 111 in Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan), and the dinar issued by Vāsudeva II, c. 280 ce, BM 1894.5,6,110 (see No. 56 .p. 111 in Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan).

V. The Geometric Model Beyond Gandhāra

A. Gandhāran Influence Southward: Gupta coins

Samudragupta's Scepter coins feature a goddess on the reverse seated on a throne. The goddess and the throne with the Geometric Type of legs are derived from the previous Kuṣāṇa coins as seen on the aforementioned Vāsiṣka and Vāsudeva II coins. However, the goddess is unlikely to be Ardoxsho in the Gupta context. Far more likely for a Gupta royal issue is the appearance of Śrī-Lakṣmī and this identification has already been offered by several scholars, in addition to myself.Footnote 29 Śrī-Lakṣmī enthroned on a seat with the Geometric style legs can also be seen on Samudragupta's Archer Type coins and some of the succeeding Archer Type coins minted by his son, Candragupta II. However, there is a gradual substitution away from the northwestern throne to the more Indian lotus seat which started already in Samudragupta's Battle-axe coins and became the norm in Candragupta II second class of Archer coins.Footnote 30

B. Gandhāran influence Eastward: Central Asia

1. Some of the Kidarite Huns minted coins which have on the reverse a goddess seated on a throne whose legs exhibit the (debased?) Geometric style. See for example the fourth century debased dinar from Gandhāra (BM 1850.3.5.20 2).Footnote 31

A recent paper by Joe Cribb describes a heretofore unrecorded Kidarite type (his Type 2) that shows a goddess, seated on the throne with Geometric Type legs, holding a cornucopia in the left hand and a lotus in the right.Footnote 32 The same goddess, holding the same attributes, may also be seated on a lion. Cribb's difficulty in identifying the goddess can be easily overcome with perusal of my studies on the attributes Lakṣmī adopted from the Northwest (cited in footnotes; 29, 30, and 33 below).Footnote 33 Actually, just looking at the reproduction of coins, attributed to the late Kuṣāṇas and the Kidarites, in von Mitterwallner's book shows how prevalent was this image of Śrī-Lakṣmī seated on a throne whose legs exhibit the (debased?) Geometric style.Footnote 34

The Kidarites ruled in ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan during the fourth and fifth centuries ce. The throne type which appears so prominently on their coinage can be seen subsequently in Central Asia.

2. Two wooden fragments that may be lathe-turned furniture legs found at Kizil have recently been further analyzed. They, together with other wooden furniture objects, had initially been published by Chhaya Bhattacharya.Footnote 35 Bhattacharya neither dated the two objects (nos. 247 and 248 in her 1977 book) nor assigned them to a particular site. Giuseppe Vignato made some clarifications and analytic advancements (Fig. 24).Footnote 36 Quoting from the notes of Grünwedel of the third German Turfan Expedition (1905), Vignato surmises that the two wooden furniture legs were found in Cave 76 at Kizil, but may well have been placed in that cave only for safe-keeping; in actuality they may have belonged to another cave at that site. The wooden lathe-turned legs consist of a series of geometric shapes: rings, globular forms, ‘bell’ shaped forms and attenuated ‘vase’ shaped form becoming cylindrical towards the bottom where rings serve as base. In other words, the wooden legs from Kizil look like first cousins of the Gandhāran Geometric Type. Fittingly, Vignato suggests that they may have been part of a palanquin.Footnote 37 This is a welcome suggestion of course, considering it is already determined that as early as Butkara I, Yaśodharā's bridal palanquin is outfitted with Geometric shaped legs (see above).

Fig. 24. Two wooden lathe-turned furniture legs. Kizil. Photograph after G. Vignato, “Monastic Fingerprints”, 2016-17; Fig. 10. Right insert is photograph B 0798 copyright of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst.

In time it is quite possible that more examples from other sites may yield legs related to the Geometric Type. I propose this possibility because the second type of Gandhāran decorated furniture leg, the Figurative Type, travels and transfigures elsewhere in Central Asia, indicating that there were other sites influenced by Gandhāra.

VI. The Figurative Type of Furniture Leg.

The Figurative Type is complex. Composed of anthropomorphic and theriomorphic shapes, it is not at all clear to me the sequence in which the different figural parts combined to form the several combinatory types.

There are far fewer examples from which to draw conclusions. Those mentioned below probably represent the majority of examples; I found them scanning the same bibliography (cited in fn. 27) as for the Geometric Type. It may be best therefore to describe the different Gandhāran Figural Type legs, going from the simplest to the more elaborate examples. In so doing, a chronological development is not implied; rather ease of comprehension is aspired to.

A. Hand–crafted Gandhāran Figurative Types

(Examples in materials other that wood or ivory, as for example stone reliefs, are assumed to copy the hand-crafted prototypes).

1. Leg composed of a single theriomorphic form

On the reverse of a Kuṣāṇa bronze dinar of Huviṣka, the Iranian god Manaobago is depicted seated on a couch equipped with lion legs; not just the paw but the whole lower and elegantly curved lion's leg causes the dais to be sufficiently raised so that the god rests his feet not on the ground but on a footstool (Fig. 25).

Fig. 25. Manaobago seated on couch. Huviṣka Dinar. British Museum Coin No. 1894,0506,46. Photo after Gandhāra. Catalogue, No. 95.

The lion's leg can be topped by that animal's head. On some tripods in scenes of the First Bath of the Buddha-to-be, Stoye notices this combination and describes them well: “… the lion's foot ends just above the knee joint with a lion protome, so that the leg's projection becomes both the thigh of the lion leg and the chest of the beast of prey”. Footnote 38 This description emphasizes the swelling, a seemingly organic curve, between the head and the paw which threads through various other combinations of the theriomorphic type, as noticed below.

2. Leg composed of two different animal forms

The Parinirvāṇa formerly at the Guides Mess, Mardan, and now in the Peshawar Museum (Fig. 4) has an elephant's head above the lion's leg. The elephant has a prominent projecting trunk. As mentioned before, the legs support the Buddha's bedstead. Attention to the treatment of the elephant's brow reveals the form of the brow. It is conceived in two parts, an upper and lower part; the segments are separated by a band bound tightly around the middle of the forehead. The constriction emphasizes the bulging upper part. [The aforementioned floral designed cube above the bulge, probably contained the mortise joints affixing the supports to the bed's plank.] A first-century ivory furniture leg, 27 cm, found in Begram, Afghanistan (Fig. 26; No. MK 04.1.34 National Museum of Afghanistan) already exhibits the double protuberance on the elephant's upper brow. Indeed, the entire leg, carved in high relief, is in the shape of the head and trunk of an elephant; it is thus a furniture leg only of the elephant. Its relevance at this point in the analysis is that stylistically the Begram leg appears to bridge the way the features of the elephant on the Roman bronze couch leg (Fig. 5) and on the Gandhāran Parinirvāṇa relief from Swat (Fig. 4) are represented. The Roman oval outlines around the eyes are evident on the Begram ivory furniture leg as also the trunk's loose skin. The brow's division and double protuberance is noted only in the Begram leg. Another ivory elephant chair leg, though probably dated to the later Kuṣāṇa age, keeps two conventions noticed in the Begram and Swati legs—namely the band dividing upper and lower parts of the elephant's brow and the insistence of the bulbous nature of the upper part (Fig. 27; No. 75. 103; The Cleveland Museum of Art).Footnote 39 Of additional interest for the present analysis is the careful rendering of acanthus leaves above the bulbous section. The tabouret leg (43.8 cm), remarkably intact and intricately decorated with vine and grape leaves as they appear in Gandhāran art is made out of an elephant's tusk whose curve governs the shape of the leg. The lion's foot at the bottom is made from a separate piece of ivory.

Fig. 26. Ivory Furniture Leg. Begram, Afghanistan. C. 1st c. ad. Photo courtesy, National Museum of Afghanistan; No. MK 04.1.34.

Fig. 27. Ivory Furniture Leg. Late–to–post Kuṣāṇa. Gandhāra. c. 4th century. The Cleveland Museum of Art. The Severance and Greta Milikin Purchase Fund No. 75.103. Photo after Czuma, Kushan Sculpture.1985.

A Kuṣāṇa relief from Sikri, Taxila continues to show a furniture leg composed of two theriomorphic forms but the top portion of the elephant has been transposed (Fig. 28). The elephant is now the second figure; the lower section of the head is emitted from a lion's gaping mouth and the elephant's trunk protrudes, glides, descends and curls around the lion's paw at the bottom.Footnote 40 Still, two protuberances can be noticed, only in this relief they could be interpreted as belonging to the elephant's brow or the bulging cheeks of the lion's maw. In the Gandhāra Parinirvāṇa relief at the Victoria and Albert Museum (No. I.M. 247–1927), the same sequence is carved on the legs of the Buddha's bedstead but here, the lion's wide open maw emits the entire elephant head, thus showing a band separating the elephant's brow and two—near spherical—bulges of his upper brow. There are two swellings below the cord.Footnote 41 Insistence on noticing these swellings is to suggest that this feature may not necessarily be a stylistic trait but rather have conceptual significance. The bulges occur on two other examples known to me that represent the mid-section of a furniture leg. At present they are the only others I know that show a lion's mouth emitting an elephant head with bulbous brow. Both these examples, a schist furniture fragment, Ht. 13.5 cm., in a Swiss Private CollectionFootnote 42 (Fig. 29), and a beautifully carved Buddhist pedestal, heretofore unpublished, with lateral composite throne legs framing a worshipful scene with a Bodhisattva (Museum of the University of Missouri, Columbia; Ht. 0.177 m x L. 0.690 m; No. 84. 67. Fig. 30) show the same round swellings sculpted as soft globes suggestive of female breasts The Missouri pedestal warrants further analysis under a third heading.

Fig. 28. Bodhisattva on Throne. Sikri, Taxila; Chandigarh Museum. Author's photograph.

Fig. 29. Schist Furniture Fragment. Gandhāra. Swiss Private Collection. Photo courtesy of the Collector.

Fig. 30. Buddhist Pedestal with throne legs. University of Missouri, Museum of Art and Archaeology, Columbia (No. 84.67). Photo courtesy of the Museum.

3. Leg composed of theriomorphic and anthropomorphic forms

The schist Missouri base (Fig. 30), has a row of figures on either side of a turbaned personage seated on a throne. This central figure is haloed and holds a lotus in the left hand. The scene is bracketed by the Figurative Type of legs. The description is based on the right leg as the left side is in a broken state. The new element—under both the lion's open mouth and the elephant with the bulbous brow and projecting trunk—is a seated cross-legged male wearing a turban. His body is turned towards the enthroned personage, paying him reverence with folded hands. On either side of the reverential male parts of the lion's paws are sketched. Other noteworthy features are flame-like striations that surround the entire Figurative Type Leg and the parallel grooves that refer to the elephant's ear. Unfortunately there is no trace of the form surmounting the pedestal.

Another leg support exhibiting animal and anthropomorphic forms has been published once, in 2004.Footnote 43 It is of considerable interest that this Figurative Type of leg in the Collection of David R. Nalin has some aspects that are similar to the Missouri pedestal legs, yet it also has two elements not found there, nor elsewhere in legs thus far described (Fig. 31). The similarities are confined to the top part—a lion seen without lower jaw, suggestive of the lion's open, gaping mouth. On the bottom there sits a cross-legged male, supported on two (possibly) round, cushion-like objects. His face and head gear are broken therefore no further comparisons can be made to the Missouri seated male. There is no elephant below the lion's open mouth; instead we see the bust of a female holding a flat tray on which are displayed five ‘cakes’. On either side of the female are bulbous forms. She herself is ensconced within acanthus foliage. The reasons for combining these figurative forms need to be worked out. However, formal analogies to the tray-carrying female amid acanthus leaves may be offered. The excavation report Butkara I, Part 3, Plate DLVII (Inv. No. 286) shows a female bust amid two rows of acanthus leaves on the main face of a Corinthian capital from a pilaster.Footnote 44 Another Buddhist architectural sculpture shows a significant detail: the bust of a female holding a tray of stacked round ‘cakes’. This image occurs on a stone bracket sculpture from Taxila's Dharmarājikā monastery court.Footnote 45 It can be concluded that a buxom female, who may hold a tray, is not so unusual in a Buddhist monument. It is tempting, based on Ebert's analyses, to consider the bulbous forms on either side of the female on the leg of the Nalin Collection (Fig. 31), as stylised depictions of breasts. If this conjecture is accepted, then the middle portion of the Nalin throne leg (Fig. 31) effectively highlights two feminine forms: there is the bust of the female and the (possibly) multiple surrounding breasts. The Nalin throne support, accordingly, introduces the fourth Figurative Type.

Fig. 31. Probable Throne Leg. Gandhāra. Late Kuṣāṇa. Photograph, courtesy David R. Nalin. Fleming Museum of Art, University of Vermont, Gift of Dr David and Dr Richard Nalin. 2010.6.5.

4. Leg composed of theriomorphic forms and (possibly) a partial female (i.e. anthropomorphic) form

Much to the credit of Jorinde Ebert, the bulbous globes on numerous Gandhāran furniture legs can conceivably be unscrambled. On a relief, she noticed that a pedestal framed on either side by legs with the lion's upper jaw and paws has between them globes punctuated with raised dots. Evidently, she concluded, these projections (with their outer rings) are meant to be nipples on breasts.Footnote 46

The pedestal in question is in the State Museum Lucknow (G. 270). N. P. Joshi, one author of that Museum's catalogue on Gandhāra art, noticed these raised dots but, I believe that he completely misinterpreted them.Footnote 47 I notice another Buddhist pedestal—not heretofore brought into this context—which has the same three elements (i.e jaw, globes, paws). Markings seem to be in the middle of some of the globes, thus, providing another possible example of ‘breasts’ according to Ebert's astute observation.Footnote 48

A remarkable polychrome figure does much to uphold Ebert's observation; it proves that a female, or feminine part, has an appropriate presence in certain Figurative Type furniture legs. The figure also suggests that in antiquity a close relationship should have been promulgated between the female and the elephant. The figure in question represents the metamorphosis of the elephant-cum-lion leg into a female as elephant bust (Fig. 32). The Kizil dried clay image dating c. 700 ce (Ht. 63.5 cm) is in the Berlin Museum (MIK III 8206) and was last on exhibit in Paris where M. Yaldiz wrote the entry in the Catalogue.Footnote 49 Incredibly, she considers this figure to be half-male, half-animal. The image has an asexual face, wears a choker and has hair held in place by a band and some indistinct mass, possibly a headdress. The torso is a visual pun. It resembles both an elephant's head and a female's chest; the elephant's two protuberances are now breasts; seemingly, eyes peer from beneath the breasts/protuberances (associated with the elephant's brow). The elephant's bulging trunk curls around the chest and reappears near the female's waist. Her torso has elephant ears instead of arms; the ears imitate the parallel grooves marking the elephant's floppy ears (cf. Fig. 30). Terminating the figure which Yaldiz calls a part of a throne is a design loosely and schematically rendering a lion's paw. The bust of the Kizil female as elephant (or vice versa) is due to the elephant's upper protuberances on the brow; frequently noticed in this paper, they apparently fostered an analogy with feminine breasts. In Sanskrit literature the comparison between a woman's breasts and an elephant's frontal swellings is a common simile. The Pañcatantra (I.224) contains such a literary comparison; the simile occurs in The Saundaryalahirī (vs. 72) and in The Dhvanyāloka of Ānandavardhana, with Locana of Abhinavagupta (2. 27b L), even in a Tamil text, the Tirukkural (1087).Footnote 50 I propose that a plastic object can exhibit the same comparison; it is thus the visual equivalent of the literary conceit. The throne and couch legs under discussion illustrate this phenomenon. The Kizil metamorphic female is a rarity no doubt, but its form may have antecedents.

Fig. 32. Female as Elephant Support. Terracotta. Kizil. C. 700. Asian Art Museum (Acc. No. MIK III 8206), Photo after Sérinde, Terre de Bouddha, (Grand Palais, 1996), p. 135.

Half-female, half-animal precedents exist and they come from Parthian Nisa in Central Asia's Turkmenistan and Aï Khanoum in Northeast Afghanistan (Fig. 33). Invernizzi suggests that the Nisa sculptures could be of sirens (Greek mythological winged women).Footnote 51 The exaggerated curve in the mid-section of one Nisa image calls to mind the bulge of the elephant's trunk in Gandhāra as it descends to connect to the lion's paw. In addition, a woman's head and lion paws or claws could suggest sphinx-like affinities. Invernizzi thinks the Aï Khanoum sphinx-like female is earlier than the Nisa examples. Perhaps both mythic motifs—the sphinx and the siren came eastward under Achemenian and Hellenic influences. Nearly 50 years ago the excavator of Aï Khanoum Paul Bernard had the same opinion. He closed his paper on “Sièges” (see fn. 14) with the observation that the Achemenian lion paw survived and became Hellenised not only in Central Asia (e.g. Aï Khanoum) but also in the Hellenised West. He cites Greek furniture legs adding to the lion's claws strange forms such as human or animal busts, or the protome of a sphinx or siren. Further, he opines that the Seleucid Orient influenced the creation of such forms during the Hellenic Period. This is a fruitful theory to pursue for understanding more about the origins for unusual composite forms in Central Asia.

Fig. 33. Sirens and Sphinx-like creatures. Aï Khanoum and Nisa. Photos after Antonio Invernizzi, Acta Iranica. Cultura greca e cultura iranica in Partia. Troisième Serie, Vol. XXI, (Lovanii, 1999); Fig. 31 and Tav. 11 e and f.

There are quite a number of Gandhāran Figurative Type throne legs which include globes—or shall we say breasts:

Some Bodhisattva Maitreyas sit on pedestals with these features:

a) Teaching Maitreya with flask on the plinth. c. fourth century PeshawarMuseum (Inv. No. PM3000 [old: 1435].Footnote 52

b) Seated Image of Maitreya from Shotorak. Kabul Museum.Footnote 53

Several Buddha narratives and single icons have a base with this version:

a) Seated Buddha teaching, another seated Bodhisattva.Footnote 54

b) Throne with reliquary on the base of a standing Buddha. Central Museum, Lahore (Inv. No. G-381 [old: 740]).Footnote 55

c) Legs on Yaśodharā's bedstead in the Great Departure. Musée de Lahore. Footnote 56

d) The Ordination of Nanda. Musée de Lahore.Footnote 57

B. The Figurative Type Beyond Gandhāra

To date, I have not found the Figurative Type in ancient representations of furniture in the Indian subcontinent. Nor do Sasanian texts, or actual furniture specimens, indicate the lion paw combining with the elephant, even though the lion remains a viable feature in Sasanian art. The elephant is not recorded, although many other zoomorphic throne legs are used in the Sasanian and early Islamic Periods.Footnote 58

The Figurative Type with all its creative variations seems to have been developed by the craftsmen of Gandhāra. Throne legs featuring figurative forms in Central Asia in post-Kuṣāṇa Periods would seem to confirm that the Type is (and remained) a northern phenomenon.

1. Evidence from a Central Asia text

The Luoyang Qielanji, dated c. 547 contains a description of the Hephthalite court which provides a most interesting detail. “In the country of Heda /Yeda” begins the entry about the king's wives. Then there is the following observation: “When the king's wives go out they ride in chariots and indoors they sit on bench-thrones made in the form of six-tusked white elephants and four lions …”.Footnote 59 The description is of the Hephthalite court in Tocharistan. A bench throne is likely to be a seat without a backrest. That the throne incorporates the form of six-tusked white elephants strongly suggests knowledge of the importance of the elephant with six tusks in Buddhism. Describing the throne in the form of elephants and lions recalls the various Gandhāran throne supports with these two theriomorphic forms. Of course, we do not know how these Central Asian thrones looked, nor how these animals were depicted on thrones. To the best of my knowledge there is no reasonably intact example available. There are two seventh-century wooden lion fragments, probably part of a throne, providing a possible clue.Footnote 60 They were found in Achik–ilek near Kirish (in the area of Kucha and Kizil). Broken below the chest, it is not possible to determine whether these lions combined with another animal. Nevertheless, both the lion fragments and the text suggest that some aspects of the Gandhāran Figurative Type may have been preserved. Historically, this is possible since by the early sixth century, at the time the monk Song Yun visited the Hephthalite king, the second or third Hephthalite king was ruling in Gandhāra.Footnote 61

2. A Second possible female/elephant transformation from Kizil

Kizil (Cave 10) may provide a possible second example of a female/elephant metamorphosis. The wooden fragment is in the Berlin Asian Art Museum (MIK III 8139), and is dated c. sixth to seventh century.Footnote 62 The fragment has no (anthropomorphic?) head, or perhaps it was broken off Härtel speculates that the fragment's “flat top clearly indicates that the” [elephant's?] “head was originally an architectural element”.Footnote 63 What remains is the brow of the elephant and part of the elephant's trunk, right tusk and ear. The ear is rendered in the same fashion as that of the Kizil woman-cum-elephant (Fig. 32), that is, with parallel grooves. The small section of the trunk that remains indicates that it enters into a twist. The brow bulges and the ‘eyes’—underneath the bulges—are small. The brow is decorated with trappings. Two adorned bands cross the front of the upper head meet at the centre (between the ‘eyes’), where rests a large six-petal rosette in a medallion. However, it is quite possible to read the elephant's brow plus trunk as the chest of a female. Specifically, clay Devatas dating c. seventh or eighth century according to Härtel's Catalogue, and coming from Shorchuk, are portrayed with quite similar ornamental cross-shoulder bands having a large central medallion resting below the bosoms on the naked chest. Footnote 64 Viewed from this perspective, the bulges of the Kizil wooden fragment could be ‘read’ as the breasts; the ‘eyes’ as the nipples and the ear in the place where—as Fig. 32 the female's arms would be. As such, the fragment could be another woman/elephant merger—to which might belong the lower part of a wooden elephant leg also found in the same Kizil Cave 10 according to Bhattacharya.Footnote 65

3. Khotan

Along the southern part of the Silk Route there is hardly any comparative material. Stein's explorations at Khotan however uncovered wooden legs exhibiting a tangential similarity to numerous Gandhāran furniture legs surveyed above. The Khotanese legs come from the site of Niya. Stein describes one set of chairs as having the head of a lion, the leg of a horse and possibly a winged body (Fig. 34).Two legs of another chair show male and female protomes; whereas the busts are human, the parts below the waist, he notes, are bird-like and the leg is that of a horse.Footnote 66 These descriptions are not close to the forms noted on Gandhāran legs—except for one aspect, easily seen in Fig. 34. The Khotanese legs show a pronounced curve in the mid-section; such a curve, noted in the description of Fig. 3, can be seen in other Figurative legs where a pronounced curve is achieved by the elephant's trunk (see Figs. 4, 28, 30, 31). It may be that Stein incorrectly identified the one leg as having the head of a lion. This creature (Fig. 34, right) could be a fenghuang. Indeed the same Luoyang Qielanji, section 5 as mentioned above, states that the Hephthalite king sits on a “golden bench-throne with four golden phoenixes as its feet”. Ching Chao–jung has stated in a personal communicated dated 9/18/2017 that “phoenixes” in this entry, which was copied from Jenner's translation, is the conventional English translation for the Chinese word fenghuang 鳳凰.

Fig. 34. Wooden Legs from Niya, Khotān. Photo after Sir Aurel Stein, Ancient Khotan, Vol. I. Text. Reissued 1975 by Hacker Art Books; page 336, and Plate LXX. (N. xii, 3).

VII. Conclusion

It may surprise some that a region of South Asia exposed to two imperial dynasties of its own—the Mauryan and Kuṣāṇa—should have been strongly influenced by foreign imperial designs. A fairly recent interview given by a prize winning Mumbai architect allows us to extrapolate why a lacuna in prestigious furnishings may have existed in antiquity. Bijoy Jain spoke to the Wall Street Journal in April 19-20, 2014. “Furniture”, he said, “ is very foreign in India …The most common piece of furniture we have is the charpai, a four-legged bed made of wood with a woven net or rope mesh. It's for sitting on during the day and sleeping on at night”. If this observation can be made in 2014, it should assuredly have a kernel of validity for antiquity. Foreign-inspired furnishings expressing prestige, especially royal prestige, are unlikely to have shunted aside local prestigious furnishings. The lion throne as a royal seat was introduced by the series of incoming foreigners for whom the lion was the symbol of power par excellence.Footnote 67 The leonine motif meshed well with India's conceptual leonine associations and the lion became the animal most frequently represented as part of a throne.Footnote 68 Buddhist literature portrays both the Buddha's nature and doctrine via leonine similes. Born into a petty royal kingdom, the Śākyas, he was called the lion (siṃha) of the Śākyas. His declaration of the Buddhist dharma is described in the Sutta Nipātta 3.11: “As with a kingly lion's roar [he] shall start truth's wheel”.Footnote 69

The Geometric Type probably had neither more nor less status than the full lion throne. In the same Taxila relief, Geometric Type legs on the Buddha's bedstead are shown in a scene directly adjacent to the scene of Maitreya on a lion throne.Footnote 70 So too, the same emperor, Vima, can sit on a throne with Geometric Type legs (as on the double dinar, Fig. 13) as well as on the lion throne, in the well-known Mathurā sculpture.Footnote 71

The elephant used as the first-century Roman bronze leg of a couch (Fig. 5) may represent a foundational type that developed further in Gandhāran furniture, and this despite notable iconographic differences. The Roman bronze elephant has a flat brow, not the Gandhāran twin domed brow indented in the middle. The difference can be easily explained: the Romans rendered the African elephant's characteristic head formation with which they were familiar through their conquests, whereas the Gandhārans depicted the Asian elephant, with which, of course, they were familiar. Roman furniture could make it to the subcontinent as a result of trade. Ease of adopting the elephant as part of a throne support is due (to some extent) to the elephant's royal associations in pan-Indic, including Buddhist, contexts. Some associations have already been noted, but two more can be added, namely the elephant's connection to the installation of kingship (i.e. the royal consecration ceremony abhiṣeka). I say this because elephants are the sprinklers of the water over Lakṣmī when installing in her the power of sovereignty.Footnote 72 In addition, the elephant is the king's royal mount. Trautmann takes this storied image and projects it into reality. “The performance of kingship from an elephant's back, in essence the association of the war elephant with kingship, gives the animal a symbolic power that spreads to other spheres of life, notably religion”.Footnote 73 From Trautmann's investigations it can be argued that the royal elephant from the time of the Mauryas may have come to represent the Buddhist virtue of non-violence.Footnote 74

However the way the elephant is combined with the lion in the Gandhāran Figurative Type is highly creative and probably original to Gandhāra. It has not been possible to find antecedents for the distinctive way the animal's parts are reconfigured so that the elephant's trunk curls around the lion's lower leg and paw. Nor are precedents known to me to account for a design displaying an elephant's head jutting out from a lion's upper jaw. The appearance of breasts and/or a buxom female can, at this writing, be perhaps explained by the analogy cited in Indian literature between the soft protuberances on the elephant's brow and female breasts—and Pregnant Māyā as pictured in Gandhāra art (see end of conclusion).

Cultural explanations for the distinctions between thin, straight legs and the more decorative and curved legs, noticed at the beginning of this essay, lie hidden in an architectural treatise on dwellings. Though coming about a millennium after the Gandhāran reliefs, the text yields information that appears not only useful but characteristically ‘Brahmanical’. It relates differences in shapes to rank and status (thus caste) differences. I quote from the Mayamata, originating from South India; the text is dated between the early-ninth and late-twelfth century.Footnote 75 Chapter 32 discusses Beds and Seats. Under ‘Beds’, the feet/legs of a divan are specified according to the class of its user:

“A tiger-foot or gazelle-foot bed is reserved for brahmins and kings and the third type (with straight feet) is perfect for the two other classes” (32.10a).Footnote 76

Rank, in other words, defines whether legs supporting beds and divans should be richly carved or plain and thin.

The shape of throne seats, according to the Mayamata, also responds to the rank of the associated personage. Chapter 32 10b – 13a discusses ‘Seats’. After providing measurements for straight legs (etc.), the texts turns to āsana “provided (with legs in the shape of) lions, elephants, dwarves or bulls, when it is for the gods as well as when for brahmins and kings; according to whether it is provided with (legs of) lions or of elephants it is designated by the corresponding name (lion throne or elephant throne)”.Footnote 77 In the very next section (32. 13b), the text emphasizes that the lion throne is meant for gods and kings.

The oft-noticed curvature of Figurative legs in Gandhāran Buddhist reliefs may be clarified to some extent by Vinaypiṭaka II 149, 15–17. The text comments on the type of bed and seat that monks may have.Footnote 78 The text says:

anujānāmi bhikkhave ku īrapādakaṃ mañcam …ku īrapādakaṃ pīṭhaṃ

“…ich erlaube, ihr Monche, ein Bett mit Krabbenfüssen …ein Sitz mit Krabbenfüssen. ˮ

“with curved legs” (I. B. Horner,The Book of the Discipline, Vol. II, 1940, S 240).

Of course, it must be remembered that the Geometric Type of leg appearing far more frequently in Kuṣāṇa reliefs than the Figurative Type was not curved. But, significantly, it was also not plain.

Besides differences in shapes and designs, there are not too many differences between the two types. It is difficult to find a chronological difference between the use of the Figurative Type vs. the Geometric Type. Fewer examples of the Figurative Type in reliefs may be due to the type requiring greater carving dexterity and investment of time, and/or it may be due to the accident of fewer archaeological findings. Further, no clean separation of usage between the two Types can be established. Both can be used in similar contexts and the two Types can even meld, as seen in a scene among third-century scenes of the Buddha's Life (Inv. No. G –109 [old:1139 ]; here the Buddha's throne legs have lion paws surmounted by a series of geometric rings.Footnote 79 Precedence exists for this melding among royal Persian furniture legs which add falling leaves.

To conclude, shapes, designs and usages of chairs (most often thrones), bedsteads and stools cohere along historical, sociological and religious lines. The origins of the elephant and lion forms come mainly from the West; they are applied mainly to personages of rank, specifically the king. Kingship is the overriding symbol inherent in both the lion and the elephant as has been indicated throughout this paper. The Buddha as, the universal ruler, a spiritual king of kings, obviously, personifies the rank that allows for the display of a lion, leonine parts, and elephant on his throne, bedstead and stool. Interestingly, when carved together, the way the lion and elephant are mingled suggests they are not in combat, but rather harmoniously allied. Both animals relate to positive virtues in Buddhism and both appear as well with Bodhisattvas. Beyond the possible prototypes already alluded to, one further explanation for the presence of a female element, especially in the Buddhist context may be proposed. Gandhāra conceptualised Māyā as pregnant with the future Buddha fitted unto her body as the elephant (Fig. 35). This image, though extraordinary for there are hardly any depictions of pregnant females in Kuṣāṇa art, is based not only on the Buddhist legend, but also on the literary conceit; additionally it can be seen as the visual forerunner of the Kizil metamorphic female.Footnote 80 But perhaps one ought not search so assiduously for meaning to explain ancient furniture designs. There is nothing to suggest that furniture legs ought to carry a religious or hierarchic message. After all, no Buddhist themes or social strictures can be found in textiles covering the Gandhāran Buddhist seats and bedsteads; they seem to arise from the folk tradition.Footnote 81

Fig. 35. Gandhāran Buddhist relief. Pregnant Māyā first–third century ad. Schist, 33.5 x 41 x 10 cm. Private Collection. Photo after, Srinivasan, “Māyā: Gandhāra's Grieving Mother”.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the Mattoo Center for India Studies of SUNY – Stony Brook for partially supporting a conference trip to Budapest where some information herein was gathered. I am pleased to acknowledge the extensive assistance F. Jason Torre, Associate Librarian, Stony Brook University Libraries, provided in editing this paper to the required format.