India has strong spiritual, philosophical, and religious traditions which have an affinity with asceticism. Many images of wise men, hermits, ascetics, dervishes, and other sadhus are shown in Indian miniatures. Mutatis mutandis, when depicting hermits, both Rajput and Mughal artists use the same iconography. The mysticism so prevalent in Indian society, whether Jain, Hindu, or Muslim, is evident in countless illustrations as well as in the refuges—monasteries, ashrams, and madrasas—occupied by wise men or “renouncers” (sannyasins), alone or in groups, in faraway places, cut off from the everyday world. Sometimes the practice of rigorous self-discipline, the disconcerting exercises or postures (asanas) of hatha-yoga, as described in the treatise Bahr al-Hayat (Life's Ocean),Footnote 1 are taken so far as to appear too extreme, even ostentatious.Footnote 2

Much rarer are evocations of women hermits or yoginis and, perhaps owing to a natural delicacy, they are not shown as being under the influence of drugs.Footnote 3 On the contrary, there are many scenes of cenobites preparing bhang, a cannabis-based drink which, if taken too liberally, can transform communities of yogis into raving addicts.Footnote 4 However, there are few such images of women ascetics, who are more modest both in their demeanour and their clothing.

Indian and Persian literature contains many descriptions of heroes, facing up to the ordeal of exile or living in isolation, which have inspired paintings. For instance, the Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar wrote the biography of Rabia al-Adawiyya, a famous mystic woman, often shown with an assistant.Footnote 5 In Layla and Majnun, one of the five poems in the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami, Majunn, madly in love, half naked and thin as a rake, surrounded by wild beasts, is described on his own in the desert.Footnote 6 Similarly, the Ramayana, the epic poem of Valmiki, tells of the 14 long years in exile of Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana, their wanderings in the Dandaka forest, and their encounters with the sage Matanga and with other rishis leading ascetic lives in their remote hermitages.Footnote 7

Indeed, the theme of the “visit to the ascetic”—paying homage to a particular sage, yogi, mullah, or fakir—is a frequent occurrence in the history of Indian sovereigns and princes, particularly Mughal emperors, rajahs, and maharajahs. There is the example of Babur, who in 1519 went to the sanctuary of Gor Khatri near Begram, although his Memoirs suggest that his visit to the hermitage in the centre of a colony of Nath yogis, which is illustrated in miniatures,Footnote 8 could have been motivated by curiosity rather than by a reverence for Hindu asceticism.Footnote 9 Quite different was Akbar who in his youth had encountered the dervish Baba BilasFootnote 10 and went on to promote the idea of a synthesis between the Muslim and Hindu religions. Later he made the pilgrimage to Ajmer where he visited the tomb of Khwaja Muinud-Din Chishti, and met Salim Chishti, a holy Sufi living near Agra, who foretold that he soon would have a son. He also called on the celebrated sannyasin Gosain Jadrup whom he found living in an almost inaccessible grotto.Footnote 11 Years later, his son, Jahangir, who shared his father's respect for the holy man, went to consult Jadrup on several occasions:Footnote 12 the very first encounter of Jahangir with the ascetic was recorded in a well-known miniature.Footnote 13

Then, the eldest son of Shah Jahan, the aesthete, mystic, and philosopher Prince Dara Shikoh, desired to bring Muslims and Hindus together, just like his great-grandfather, Akbar. Devoted to religion, he enjoyed posing questions to wise yogis and wrote down their answers,Footnote 14 and, helped by pundits, translated Hindu texts, notably about 50 Upanishads, into Persian. The transcription of these ancient writings into Latin by A. H. Anquetil Duperron (1731–1805) caused a great stir in Europe. As a disciple of Mian Mir, Prince Dara is often portrayed respectfully on his knees, gazing towards his guru, Mullah Shah. He is also shown attending long discussions (mehfil), seated among the shaykhs or pirs.Footnote 15 The strength of his desire for syncretism is wonderfully captured in a large miniature which is divided in two.Footnote 16 On one part there are portraits of all the most distinguished Sufis and doctors of Islamic law, past and present, belonging to the confraternities of Chishtiyya and Qadiriyya, linked, as it were, in a chain of spirituality (silsila). Represented on the other part are 12 yogis and holy men, founders of more-or-less orthodox Hindu sects, proficient in Shaivism or in Vaishnavism. Among them we can identify Kabir, the personification of Hindu-Muslim syncretism; Jadrup, seated next to Gorakhnath, the famous yogi of the Nath school; and Baba Lal Das, a Hindu reformer.

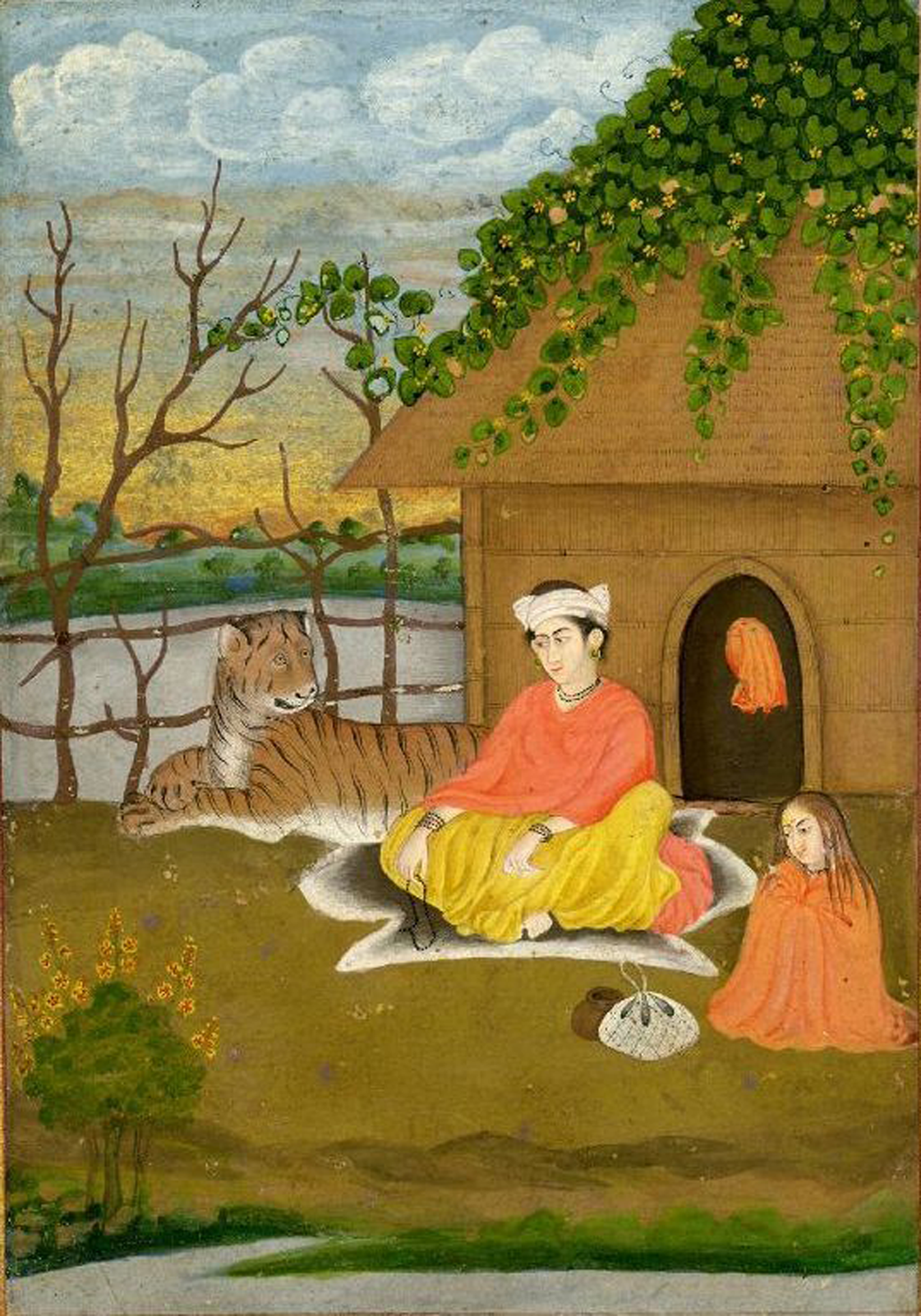

A small mid-seventeenth century Mughal miniature in the Rietberg MuseumFootnote 17 depicts an old woman (see Figure 1), with emaciated features, sitting in front of a thatched hut (kuti). At first glance, her heavy, round earrings might indicate that she is a yogini kanphata (“split eared”), signifying membership of the Shivaite sect Nath Sampradaya founded by Gorakhnath (twelfth century).Footnote 18 However, as they do not pass through the cartilage of the ears but through the lobes, which is a much less painful process, she must therefore be a penitent, retired from the world, which at this time was an unusual subject for painters to represent. The deference of the young acolyte (chola or shishya) kneeling in front of her in the respectful pose of “the visit to the ascetic” is the leitmotif characteristic of Mughal miniatures, and the counterpart to the traditional (guru-shishya) confrontation scene in Rajput painting. This excellent work has been surrounded by a motley collection of Persian calligraphy and included in a well-known border (hashiya) of motifs executed in gold reserved on paper to enhance the importance of the miniatures.Footnote 19

Figure 1. Ascetic with Devotee, Mughal workshop, circa 1650. Source: Courtesy of Museum Rietberg, Zürich. © Photo: Rainer Wolsberger.

The two ascetics are on their own in a landscape, enclosed on the left by a screen of moringas trees (Moringa oleifera) with finely drawn leaves believed to have medicinal properties. On the right stands a thatched hut with sloping roof mostly covered by a climbing plant with round leaves and little yellow flowers known as Cucurbita pepo. Footnote 20 It produced courgettes and when ready to eat we can imagine that it could have served as a larder. This vegetable seems to grow abundantly in Bengal (see Figures 2 and 3), especially on thatched roof tops, and can be easily recognised thriving on the cabins of anchorites depicted in some miniatures.Footnote 21 Then, in the foreground of Figure 1, two egrets play happily in a stream and a slender looking shrub stands out elegantly on the right. Such a precise depiction of flora and fauna evokes the style of Ustad Mansur, the celebrated court painter of Jahangir.Footnote 22 Certainly, the flight of birds flying across the partly golden sky glowing in the twilight could have come from his studio.

Figure 2. Yogi Shivaïte by Nihal Singh, circa 1770. Source: © Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Figure 3. Bangala Ragini, Murshidabad, circa 1790. Source: British Library, London.

The elder of the two yoginis, her grey hair surmounted by a turban, is clad in a chadar of the same colour, originally saffron yellow, traditionally assigned to yogis but which has turned a shade of rose after years of exposure to the blazing sun and bad weather. She sits on an antelope skin (ajina), her back turned away from the arched entrance to the hut, with two earthenware pitchers nearby, kept cool under a thin linen cover. Both hands clutch an exceptionally long rudraksha mala composed of the sacred and auspicious number of 108 prayer beads or achenes. Her crossed feet emerge from a wide white cotton skirt, and close by there is a rare example of a gadrooned bronze ewer (kamandalu or aftaba) made in the Deccan.Footnote 23 Her young companion is dressed in a fine mousseline tunic which clings to her figure beneath the rose-coloured chadar hanging from her shoulders. Her long plaited and matted hair is drawn up onto the crown like a chignon or jata-mukuta, which is associated with ascetics, and therefore demonstrates her indifference to worldly things, while the sectarian sign of Shiva (tripundra) is painted on her brow. She places her right hand on her knees, and gestures with the left as she converses with her guru. In contrast to the humble linen bundle beside her, pearl earrings, rings on her finger, a golden belt, and morchhal, or flywhisk, made from peacock feathers indicate that she has not yet attained the ultimate spiritual goal.

An eighteenth-century copy of this image (see Figure 4), of almost identical measurements,Footnote 24 repeats the composition but not the quality. The two protagonists are shown in exactly the same way, and so is their modest paraphernalia, the vegetation flourishing on the roof of the thatched hut, the two egrets in the foreground, and the elegant shrub which encloses the scene on the right. It is the colours that make the difference, for they are livelier and more luminous than the original. Both the small flight of birds in the blue sky lightly streaked with red in the manner of the painter Dip Chand, and the delicately drawn moringa leaves have disappeared. As he presumably relied on a tracing paper to make his copy, the artist, who had never seen the original, had no recollection of these minor details, and the colouring was left to his imagination. He has painted the ground spring green and reversed the colours of the clothes worn by the older yogini—the chadar is now white and the tunic is pink.

Figure 4. A Yogini and her Young Disciple, Provincial Mughal, eighteenth century. Source: Private collection.

The success of this topos could be due to the unusual presence of the two women anchorites. Some time ago a third version, from the Antoine Polier collection (see Figure 5), came up for auction,Footnote 25 although this provenance was not cited in the catalogue. However, the inscription on the mount “48. Fakinis Indiennes”, which is in his own hand, is easily recognisable as is the wide decorative border. It is a very free copy, in which the details differ markedly from the original and so was probably taken from another version without resorting to a stencil or a tracing (charba). The two women are seated on a long straw-coloured mat, in the same postures, in front of a shelter similarly surrounded by vegetation. On the right, the much older yogini, now looking younger and still seated on an antelope skin, holds her rudraksha mala in both hands, but only her left foot can be seen below her skirt. As for the disciple, the colours of her clothing are inverted, and her chignon is covered by a turban. In the space between the two, the painter has added fruits and various accessories: a lota (water jug), a sruk (ladle for offering an oblation), a pandan (box containing pans),Footnote 26 a zafar takief (aid to meditation), and a pothi (oblong shaped manuscript). Last of all, a green mossy lawn has taken the place of the egrets and the stream of water.

Figure 5. Fakinis Indiennes, provincial Mughal, circa 1780. Source: Courtesy of Christie's, London.

Antoine Polier (1741–1795), a Swiss engineer and architect, and adviser to the nawab of Oudh, belonged to a group of cultivated Europeans stationed in Bengal and Bihar in the last third of the eighteenth century. Composed of linguists, connoisseurs, and collectors of Indian painting, they must have regarded each other as rivals. We know that they often borrowed or exchanged paintings with each other. Polier found himself competing for manuscripts and miniatures, in a friendly way, with Jean-Baptiste Gentil (1726–1799), also employed by the nawab, Shuja-ud Daula, and he requested loans of miniatures in order to have them copied.

In 1770 their contemporary, the scholar and antiquary Richard Johnson (1753–1807) arrived in Bengal, first residing at Lucknow before leaving later for Hyderabad. He was supported by Warren Hastings, governor of Bengal, and was a friend of William Jones, the eminent scholar who founded the Asiatick Society in 1784. A great collector of paintings, Johnson had a passion for Ragamala (garland of Ragas) series, which during the eighteenth century were frequently painted by artists from Rajasthan and provincial Mughal schools. Johnson acquired up to 14 albums on this subject, most of them complete, as well as separate sheets, now in the British Library.Footnote 27 In traditional Indian music, the Raga, like poetry, evokes particular atmospheres (wind, storm, rain), sentiments (joy, anticipation, sadness), and emotions (rasa), through musical compositions and rhythms which vary according to the hours of day and night. These different themes and variations were personified and transposed into painting following a rigorously codified iconography. Most Ragamalas adopt an arrangement in which they are composed of 36 illustrations: that is, of six masculine Ragas, each associated with five feminine Raginis. Music, combined with prayer and devotion, was an important element of Indian religious life.Footnote 28 Guru Nanak is traditionally represented with his companion Mardana, who played the rabab,Footnote 29 and a musician can often be seen among groups of fakirs and yogis.Footnote 30 Then in Kedara Ragini or Setmalar Ragini a sadhu is either listening to a disciple playing the vina or is making his own music.Footnote 31 Certainly, numerous compositions are dedicated to the eremitical life in the Ragamalas.

One of Johnson's Ragamalas, acquired at Lucknow in 1782, is a rare album composed entirely of almost transparent charba (tracings made on paper thin buck-skin). These tracings were often used by artists in the studios to make copies of the original works of their masters. Judging from the number of stains, splits, and crumpled buck-skin in the Johnson series, they were used frequently for this purpose. But what a surprise to find among them our old yogini (see Figure 6) without the disciple, whose place is now occupied by a mild-looking tiger!Footnote 32 It is an illustration of the Bengali Ragini; in the Ragamalas that follow what is known as the “Painters System” is placed within the Megha Raga family.Footnote 33 The charba must have been taken directly from the original as most of the details are identical: the old woman with emaciated features seated on the skin of a gazelle, the foot emerging from the folds of the skirt, the long undulating rudraksha mala held in both hands, the masses of vegetation on the top of the hut, the high spout of the ewer, and the shrub to the right in the foreground. However, the entire left-hand side of the composition has been omitted. The disciple (chola) has disappeared, supplanted (or “swallowed up”) by a tiger seated nonchalantly before the hedge of leafless branches of trees which enclose the scene. It is mostly drawn in bistre ink, with a few colours represented by light touches of watercolour.

Figure 6. ‘Charba’ of Bangali Ragini, circa 1778–1780. Source: British Library, London.

Encountered so frequently one might wonder at the staying power of this worn-out figure. Perhaps it was the slightly bent attitude exuding humility, her serene and intense expression (sometimes she closes her eyes), which beguiled those artists who illustrated the Bengali Ragini (the name derives from the province of Bengal). Furthermore, the symbolism of a “great cat”, the quintessential savage beast, lying so peacefully beside a yogini must also have appealed. No fewer than 14 representations of the Bengali Ragini are in the British Library collection. In some, there is a lion or a leopard in the place of the tiger, and indeed the ascetic might even be shown seated on a tiger skin.Footnote 34 Further examples of the solitary ascetic appear in other Raginis, such as Kamoda or Devgandhar, and may be mistaken for the Bengali Ragini, which are subject to stylistic differences according to particular regions and schools of painting.Footnote 35

It is incontestable that a miniature from the Berlin Museum (see Figure 7) must have been painted using a charba or a pounced designFootnote 36 taken from the Johnson Albums, around 1780, when Johnson was based in Lucknow.Footnote 37 This miniature, which has been through many vicissitudes, is one of the Ragamalas from the Antoine Polier collection.Footnote 38

Figure 7. Bangali Ragini, Lucknow, circa 1780. Source: Courtesy of the Staatliche Museum zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin. © Photo: Jörg von Bruchhausen.

The great collector William Beckford was able to buy part of the collection thanks to the help of Brandoin, a Swiss painter who knew Polier and was nicknamed “the Rajah” or “the Indian of Lausanne” after his return to his native city.Footnote 39 Thus, the famous library of Beckford was further enriched by the addition of this series of miniatures. Inherited in 1844 by his daughter Susan, married to the tenth Duke of Hamilton, they were then transferred to her Scottish home, Hamilton Palace. When they were dispersed in London by Sotheby's at the Beckford-Hamilton sale of 1882, 20 albums were bought by the Kupferstichkabinett of Berlin. The miniatures were then distributed between the Islamische Kunstabteilung and the Museum für Volkerkunde. The latter acquired Volume I 5062 of this Ragamala (which included Figure 7), which disappeared from Berlin during the Second World War, surfaced again in England in 1968, and was finally returned to Germany thanks to the efforts of Robert Skelton.Footnote 40

As in all the pages of this Ragamala, the miniature gleams with bright colours and is surrounded by the wide border of varicoloured flowers characteristic of the Polier collection. The yogini, her features emaciated, self contained and withdrawn from the world, is seated on the ground, but is otherwise identical to the original, with the beads of her rudraksha mala slipping through her hands and her possessions limited to a miserable bundle and a kamandalu (waterpot). The tiger stretched out close by, looks up at her and blocks the entrance to the hut with his long tail. Above, in the cloudless blue sky, four birds fly towards the left and six smaller ones can be seen in the distance. The two egrets have disappeared from the foreground, but the finely drawn grass, stones, and shrub are still there.

Another example (see Figure 8) belonged to Jean-Baptiste Gentil, himself a member of this circle of dedicated collectors based in Lucknow. We can deduce from the awkward result that the painter who produced it for him must have used a charba in such poor condition that little remained of the original.Footnote 41 On this composition, executed in nim-qalam, heightened with watercolour, the hermit is seated on the ground, clad in an entirely rose-coloured tunic, but the earring has gone and there are bracelets on the wrists. In addition to the same things—rudraksha mala, kamandalu, and the bundle—a zafartakieh (a crutch which aids meditation) has been added. The companion, a rather sad-looking tiger, wears a string of large pearls round his neck. The setting remains the same: the hut (kuti) with sloping roof, profuse vegetation, the shrub on the right, and on the left, the simple fence of leafless branches and the four birds—but here they are not so far away. The big surprise is the Persian inscription “baba kabir” at the bottom of the gold border which means we are no longer looking at a yogini illustrating the Bengali Ragini.

Figure 8. Bengali Ragini, ‘pseudo Kabir’, Faizabad, circa 1770. Source: © Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

It could be that the slight shadow on the cheek of the ascetic led the writer of the inscription to assume that it was a representation of the holy man, Baba Kabir, traditionally shown seated before a loom, and who, centuries before Mahatma Gandhi, promoted the causes of manual labour and peace between the different faiths. Unlike Johnson, Gentil was hardly interested in Ragamalas, so if his important collection does contain any images on that subject, it would be only by chance. His overwhelming interest was centred on Mughal history, the civilisation of India, its geography, coinage, and people. He probably acquired the “pseudo” Kabir in the belief that it was portrait of this Indian historical personality.

The Ragamala of Album 32,Footnote 42 like the Ragamala of charbas (or Album 31), dates from the time Richard Johnson was living in Lucknow, up until 1782. In this album we discover the single old yogini again, since it is about a new version of the Bengali Ragini where the tiger has replaced the disciple (chola) (see Figure 9). The design tallies with the corresponding charba, as in the group of the other Ragas and Raginis from the same volume, to the point where in 1962, it was thought that Johnson himself had painted all 36 copies.Footnote 43 However, this hypothesis cannot be proven. In this album the Ragas and the Raginis are depicted as family groups, six on each page, surrounded by narrow gold borders, linked together by garlands of flowers. This decorative scheme, executed in gouache with colour, is similar to that of the charba album in black ink. The quality of the images, which are drawn entirely in graphite and with slight touches of different colours, is so much better that they could be earlier than those from the Ragamala of charbas. Nor do they seem to have come from the same hand. Some architectural details indicate a knowledge of European handling of perspective whereas others show a superior understanding of nature and plant life. Since these drawings have been glued into the pages of the album, it is difficult to scrutinise them closely, yet we have the impression that at least some of the figures are perforated by tiny pounced holes. This is the case for the general form of both the ascetic and the tiger as well as for their precisely drawn heads and limbs. The sombre, even sfumato, appearance of several compositions is probably also due to the use of pounces with powdered charcoal. This method certainly could explain the quality of the drawing of the drapery and the supple folds of the chadar of the ascetic, which can be compared closely with the original model in the Rietberg Museum: in addition, the head of the tiger lying beside him is by far the best of all the variants of the subject.

Figure 9. Bengali Ragini, Lucknow, circa 1780–1782. Source: British Library, London.

In 1783 Richard Johnson was sent into the Deccan where he resided at Hyderabad, and acquired a new Ragamala album, which was probably made to his order in 1784–1785.Footnote 44 The 36 compositions surrounded by an almond green border are presented in the same way, six on each sheet, each miniature being linked to the others by broad golden fillets and garlands of flowers. Most of the 36 compositions of this Ragamala derive from the Ragas and Raginis in the Johnson Albums nos. 31 and 32. Although some of scenes are the same as in the original, others are inverted, clearly demonstrating the use of pounced transfers and charbas. Concerning the Bengali Ragini, the composition (see Figure 10) derives from the same model, in the same manner as the four preceding examples, but has been simplified. The clump of grass and stones in the foreground have been eliminated, while the small shrub on the right and the leaves of the Cucurbita pepo covering the straw roof are now highly stylised, as is typical of the treatment of vegetation in the Deccan school of painting. In this fifth representation of the yogini on her own without a disciple, her looks have changed, for she seems much younger, and, in addition, the contrasting colours are brighter. Seated on the grass near the tiger, with a turban on her head, clad in a rose-lilac-coloured skirt and a beige chadar which echoes the straw covered hut, she holds a rudraksha mala in both hands. There is a bright red bundle close beside her, and also a Deccan-style black-and-white ewer with a handle, which is probably an inlaid silver bidri.Footnote 45

Figure 10. Bengali Ragini, Hyderabad, circa 1784–1785. Source: British Library, London.

Up to this point the eight versions considered were more or less of the same size. Another example, in the British Museum,Footnote 46 which is almost double that, follows the same topos (see Figure 11). The thatched hut, the Cucurbita pepo with little yellow flowers growing on the roof, are all there, and to the left a hedge of leafless branches encloses the space which extends over to the other side of the stream. A handsome tiger reclines, paws crossed, and the yogini is again seated on the skin of an antelope (ajina) and, as before, holds a rudraksha mala, though in one hand only. The chief difference is that on the right a young ascetic has come back! This long-haired young woman disciple, completely covered by her rose-coloured chadar, is crouched on the ground, beside a bundle and a lota. To conclude, the appearance of the elegant shrub situated on the extreme right has been transformed on the left by the addition of clusters of flowers.

Figure 11. Religious Mendicant with a Female Disciple and Tiger, Mughal style, circa eighteenth century. Source: © The Trustees of the British Museum, London.

The final variation of this theme is provided by a large-scale ersatz copy,Footnote 47 in which we can recognise the yogini seated in front of a hut, with her two hands holding a rudraksha mala, and ashen-faced, signifying devotion to Shiva (see Figure 12). Close by a leopard reclines, near a fence composed of leafless branches. Water pots are placed on the ground, but the vegetation which was the charm of the original Mughal composition has gone, and only the egrets in the foreground and a few birds in the sky are left to animate the scene. Of course, there may well be others in addition to the Rietberg Museum's model. For example, there is a variant miniature with Dara Shikoh visiting the ascetic Baba Lal Das,Footnote 48 where we can point out the leimotif of a hut with thatched slooping roof covered of climbing Cucurbita pepo.

Figure 12. A Hermit with a Leopard, Provincial Mughal, eighteenth century. Source: Courtesy of Christie's, London.

Among the variations, three of them belonged to Richard Johnson, two to Antoine Polier, and another to Jean-Baptiste Gentil. We might imagine that other members of the European colony resident in Oudh at the end of the eighteenth century—such as the collectors Warren Hastings, Claude Martin, Elijah Impey, John Baillie, William Fullerton, Archibald Swinton, Richard Plowden—could also have owned copies. Each of these examples demonstrates the fascinating destiny of works of art and the mysterious paths they follow across the centuries. Moreover, on the one hand, they provide evidence of the permanence of mysticism in Indian thought, of the transmission of the spiritual tradition, and of the disciple's reverence for his guru; on the other, they show how the repertory of the great masters was perpetuated in the studios, and renewed by the copies made over long periods. These should not be regarded as plagiarism, but as part of the Indian pictorial tradition, exemplifying the respectful and admiring homage paid by the painters to their predecessors.