Introduction

In the Ystoria Mongalorum quos nos Tartaros apellamus, which John of Plano Carpini drew from direct observations he made during his trip to the Mongol court in 1245–1247, the fifth chapter stands out from all the others, in that it traces the history of the Mongols, the rise of Chinggis Khan, his conquests and those of his successors. This chapter is therefore not based on the direct testimony of the Franciscan monk, but on the statements of Russian clerics, “or other persons who have remained among the Tartars for a long time”, who have reportedly served as intermediaries at the Mongol court, as its author has repeatedly indicated.Footnote 1 This narrative mixes fabulous elements with historical events, identifiable from other sources.Footnote 2 As already noted many times, these elements seem to be for many of them borrowed from the Alexander Romance of the Pseudo-Callisthenes.Footnote 3

However, these are not additions by Plano Carpini himself: undoubtedly, the story told in the fifth chapter is of Mongol origin.Footnote 4 This can easily be seen from the text parallel to the Ystoria Mongalorum, the Hystoria Tartarorum, composed in 1247 by the Franciscan monk from Silesia C. de Bridia, based on a first version of Plano Carpini's work to which he added information gleaned orally from Benedict the Pole and Ceslaus (or Stephen) of Bohemia, Plano Carpini's companions in his journey to the Mongol court.Footnote 5 Indeed, C. de Bridia, unlike Plano Carpini, systematically gives the original names of the marvelous peoples allegedly encountered or the imaginary countries supposedly crossed by the Mongols, and provides Turko-Mongolian etymologies that prove to be perfectly correct.Footnote 6 Benedict the Pole spoke directly to the Russian interpreters, before translating into Latin for Plano Carpini: his story, transmitted to C. de Bridia, was therefore, in all likelihood, closer to the original Mongol story. Michèle Guéret-Laferté even hypothesizes that the informants of the Franciscan monks were themselves Mongols, Plano Carpini having replaced them in his text by Russian clerics, and therefore Christians, in order to better guarantee the truth of his statements.Footnote 7 The fifth chapter of the Ystoria Mongalorum, and its counterpart in the Hystoria Tartarorum, would therefore correspond to a “Chinggis Romance”Footnote 8 composed in a Mongol environmentFootnote 9 from Turkish, Mongol and Chinese legends, and elements usually presented as drawn from the Alexander Romance.Footnote 10

Within this “Chinggis Romance”, however, Plano Carpini reports a curious episode that takes place in the early days of Chinggis Khan's career:

The Mongols on their return to their own country prepared for war against the Kitayans, and moving camp they entered their territory. When this came to the ears of the Emperor of the Kitayans he went to meet them with his army, and a hard battle was fought in which the Mongols were defeated and all the Mongol nobles in that army were killed with the exception of seven. This gives rise to the fact that, when anyone threatens them saying “If you invade that country you will be killed, for a vast number of people live there and they are men skilled in the art of fighting”, they still give answer, “Once upon a time indeed we were killed and but seven of us were left, and now we have increased to a great multitude, so we are not afraid of such men.”

Chingis however and the others who were left fled back to their own country and after a short rest Chingis again prepared for battle and set out to make war against the land of the Uighurs.Footnote 11

Mongali autem, in terram eorum revertentes, se contra Kytaos ad praelium preparaverunt; qui, castra moventes, terram Kytaorum intraverunt. Imperator autem Kytaorum hoc audiens venit cum suo exercitu contra eos, et commissum est prelium durum, in quo prelio Mongali fuerunt devicti, et omnes nobiles Mongalorum qui erant in predicto exercitu fuerunt occisi, usque ad septem. Unde adhuc quando aliquis eos minatur dicens : « Occidemini si in illam iveritis terram, quoniam populi multido ibidem moratur et sunt homines ad prelium apti », respondent : « Quondam etiam fuimus occisi et non remansimus nisi septem, et modo crevimus in multitudinem magnam, quare de talibus non terremur ».

Chingis vero et alii qui remanserunt in terram suam fugerunt, et cum aliquantulum quievisset Chingis predictus, preparavit se rursum ad prelium et contra terram Huyrorum processit ad bellum.

We find this same episode, in more or less similar terms, with some variations, in C. de Bridia's Hystoria Tartarorum:

Soon afterward Chingis collected a still more powerful force and entered the eastern country called Esurscakita, the natives of which call themselves Kitai, to whom the Mongols, and the other three provinces speaking their language, had formerly paid tribute. This country is large, very extensive, and was then extremely rich, having a powerful and energetic Emperor who, hearing the news and violently enraged, met Chingis and his army with a numerous multitude in a certain vast desert, inflicting such a slaughter on the Mongols that only seven survived, though a larger number of other nationalities succeeded in escaping […]. Chingis, however, fled unnoticed to his own country and for a short time abated his wickedness.Footnote 12

Deinde Cingis mox fortitudine grauiori collecta adijt terram orientalem nomine Esurscakita. Homines vero appellant se Kitai, quibus Mongali et relique tres prouincie lingue eorum quondam fuerant tributarij. Hec terra est magna et spaciosa valde, et erat opulentissima, habens imperatorem strenuum et potentem, qui huiusmodi perceptis rumoribus indignatus uehementer occurrit Cingis et exercuitui eius cum multitudine copiosa in quadam uasta solitudine, et tanta strages facta est Mongalorum, quod de viris Mongalis tantummodo septem remanserunt, aliarum tamen nacionum plures homines euaserunt […]. Cingis vero clam in terram fugiens per temporis modicum sue malicie pacem dedit.

Without a doubt, the term “Kitai” refers here, as in all the texts of Plano Carpini and Bridia, to the inhabitants of Northern China; the one who is called their emperor is the emperor from the Jin dynasty, of Jürchen origin.Footnote 13 However, no other source mentions a defeat of Chinggis Khan against the Jürchen-Jin, let alone of such magnitude. The two campaigns conducted during the Mongol conqueror's lifetime in northern China were, according to our sources, nothing more than a series of brilliant victories.

Thomas Tanase indeed notes that “this campaign cannot be identified”.Footnote 14 If it is not a complete invention, then what can we say about the story of this defeat which is a priori a true hapax in the literature on Chinggisid conquests? It may be recalled that the Secret History of the Mongols reports that Chinggis Khan was defeated in the battle of Dalan Baljut, shortly after his election as khan, around 1187, but by his anda (“sworn friend”) and rival, Jamuqa, and not by the Jin.Footnote 15 Rashīd ad-Dīn and the Shengwu Qinzheng Lu 聖武親征錄 also mention the event, but attribute the victory to Chinggis Khan.Footnote 16 For Ratchnevsky, there is no doubt that he was indeed defeated, but it is not so certain that we must follow the version of the Secret History.Footnote 17 Now this battle is followed, in our sources, by what Paul Ratchnevsky calls “a gap in Temuchin's life history”, which he attributes to a taboo placed on certain events in Chinggis Khan's life, which would have damaged his prestige.Footnote 18 This documentary void corresponds to a ten-year period, from the battle of Dalan Baljut to the joint campaign with the Kereyids and the Jin against the Tatars in 1196, during which period Chinggis Khan probably had to take refuge in Jin territory.Footnote 19 As Ratchnevsky notes, this reinforces the words of the Song envoy, Zhao Gong, who writes that Chinggis Khan was a slave of the Jin for ten years.Footnote 20

Another battle could lie behind this strange episode: George D. Painter, in his translation of the Hystoria Tartarorum, suggested that it might be a distorted depiction of the battle of Qalqaljid Elet against the Ong Khan of the Kereyids, which was followed by a strategic withdrawal, if not a sorry retreat, of Chinggis Khan and his men, and by the famous “Baljuna Covenant”, when Chinggis Khan and his few followers who remained with him were reduced to drinking the troubled water of the lake, or the river, Baljuna and vowed to “share the sweet and the bitter”.Footnote 21 I will come back to this hypothesis at the end of this article, but the bottom line is that the two texts we have to deal with here are the result of confusion on the part of their authors, or which perhaps occured during the transmission of the story.Footnote 22

Moreover, this passage by Plano Carpini is reminiscent of an episode in the legend of Sariq Khan, a ruler of the Kereyids, as reported by Rashīd ad-Dīn, according to which the Tatars inflicted such a defeat on Sariq Khan that, of the forty tümed (four hundred thousand men) in his army, he could only flee with forty survivors.Footnote 23 Should we therefore think that Plano Carpini, consciously or unconsciously, has mixed up several elements including, among others, the legendary account of Sariq Khan's catastrophic defeat on the one hand and Chinggis Khan's defeat against Jamuqa or the Ong Khan on the other hand? From authentic elements gleaned from the Mongol court, it would seem, as we may believe, that an episode created from scratch by the Franciscan monk and taken up by his Silesian colleague would emerge.

For Igor de Rachewiltz, it is an episode invented by Russian intermediaries, out of hatred of their new Mongol masters.Footnote 24 Alexander Yurchenko is not convinced by this explanation, but notes that “it remains unclear how it came about that veterans of Chinggis Khan's campaigns, who sat at the campfire in the evening, wrote legends about the campaigns of their Mongol masters, when in those legends the Mongol army suffered complete defeats”, and he does not include the episode in his reconstruction of the “Chinggis Romance”.Footnote 25 For Michèle Guéret-Laferté, the invention is attributable to the Franciscans themselves, this crushing defeat being part of “pure and simple additions of imaginary events”, and serves to justify the election of Chinggis Khan as emperor, once the emperor of the Kitai had been defeated.Footnote 26 Paolo Daffinà proposed, in his notes to the Italian translation of the Ystoria Mongalorum, to see in this passage a confusion of the Kitai with the Tangut-Xi Xia.Footnote 27 Faced with the difficulty of identifying the origin of this passage, most of the researchers who have studied the subject therefore agree that it is either a pure and simple invention or the result of confusion. This seems to me too easy a solution, and I will try to show here that it is neither one nor the other.

Jūzjānī and the structure of the myth

Indeed, two other sources present a story parallel to that of Plano Carpini and C. de Bridia, although to my knowledge, no comparison between these different texts has ever been proposed. The first is La Flor des Estoires de la Terre d'Orient, dictated in French at the beginning of the 14th century by the Armenian monk Hayton, who had most of his information about the Mongols from his uncle, the King of Little Armenia Hethum I, who went to Möngke in Qaraqorum in 1254. Hayton tells how the seven nations of the Mongols, who lived under the yoke of their neighbours, were unified and liberated by Chinggis Khan, how he was defeated by a large number of enemies and owed his salvation only to a bush that served as his hiding place,Footnote 28 then defeated those same enemies, and how, finally, after that, Chinggis Khan led his people by sea into a vast and fertile land in the West.Footnote 29 There are certain common points: the essential one of the lost battle, the refuge from which the Mongols then set out again in their conquests, and the seven nations, which echo the seven survivors of Plano Carpini and C. de Bridia.Footnote 30

The second one offers an even more striking parallel. It is one of the most important that we have at our disposal about Mongol history, and it also evokes a crushing defeat of Chinggis Khan, in a passage hitherto neglected, again because of its appearance, at first sight confusing and contradictory to what can be reconstructed with certainty from the beginnings of Chinggis Khan's career. However, its comparison with Plano Carpini's text reveals a similarity that is too obvious to be the result of chance. It is the Ṭabaqāt-i Nāṣirī of Jūzjānī, written in the 1260s, and more particularly an extract from the first pages devoted to Mongol conquests:

When the father of Chingīz Khān went to hell, and the chieftainship devolved on Chingīz Khān, he began to become recalcitrant [to the authority of Altūn Khān] and to desobey, and broke out into rebellion. A squadron was detached from the following of the Altūn Khan to lay waste and exterminate the Mongol groups [qabā’īl قبایل ]. Many of them were massacred, so much so that only a few remained. The survivors who had escaped the sword's blade gathered together, and left these lands. They headed north of Turkestan, and found refuge in such an impenetrable position that, from any direction, there was no road leading to it, except for a single pass. All this expanse was surrounded by huge mountains, and this place and this meadow, they call them Kelurān [k.l.rān کلران ]. They also say that in the midst of these pastures there is a spring of a fairly considerable size, the name of which is Balīq Jāq; and, in this pastures, they took up their abode, and dwelt there for a long period. In the course of time, their offspring and progeny multiplied greatly, and among that body a great number of men reached manhood.Footnote 31

چون پدر چنگیز خان بدوزخ رفت و مهتری به چنگیز خان رسید تمرد و گردن کشی آغاز نهاد، و عصیان ظاهر کرد، و فوجی از حشم التون خان به نهب و قمع قبایل مغل نامزد شدند و بیشتر را از ایشان به قتل رسانید چنانچه اندك عدد بماندند، جماعتی که از زیر تیغ باقی به مانده بودند باهم جمع شدند و از آن بلاد بطرف شمال ترکستان، بموضع حصین پناه جستد، چنانچه از هیچ طرف راهی نداشت . الا یك دره، و جملۀ آن موضع بجبال را سیات محفوف بود و آن موضع و چراخور را کلران گویند، در میان این مرغزار چشمه ایست بس بزرگ نام آن بلیق جاق در میان آن مرغزار جایهای باشش ساختند و آنجا مدتها مقام کردند، و به مرور ایام توالد و تناسل بسیار شد ودر میان ایشان مرد بسیار رسید.

This is followed by a council of all men, which makes the decision to take revenge on the Altūn Khan. To do this, Chinggis Khan is appointed amīr, and after three days of rituals, he leads an army of 300,000 men to conquer the kingdom of the Altūn Khan.Footnote 32

This Altūn Khan, or Altan Khan, i. e. the “Golden King”, is undoubtedly the same “Kitai Emperor” mentioned by Plano Carpini, since it is a common designation of the Jin Emperor, which can be found in the Secret History for example.Footnote 33 In addition, shortly before the passage cited, Jūzjānī describes Altūn Khan as the ruler of Tamghāj, a name that regularly refers to North China among Arabo-Persian authors, and is derived from Tabgach, the original name of the Tuoba-Wei, a dynasty of nomadic origin which ruled on Northern China from 386 to 534.Footnote 34 The author makes him the suzerain of the Mongols, to whom they owed a tribute,Footnote 35 just like C. de Bridia in the passage already mentioned.

So we have here, as in the Ystoria Mongalorum and the Hystoria Tartarorum, an account of a terrible defeat suffered by Chinggis Khan and inflicted by the Jin Emperor; only a few survivors escape the massacre; this is followed for a time by a retreat to a remote place before the conquest resume. Jūzjānī, however, provides much more details about the place of the survivors’ retreat. On this subject his translator in English, H. G. Raverty, notes: “The flight of Ḳaiān and Nagūz into Irgānah Ḳūn, is here, evidently meant”.Footnote 36 Raverty refers here to the origin myth of the Mongols, as first reported by Rashīd ad-Dīn in his Jāmi' at-tavārīkh, whose text corresponds indeed to that of Jūzjānī, and which deserves to be quoted extensively:

The group [qowm قوم ] that has been called Mongol since ancient times started a dispute with other Turkish groups [aqvām اقوام ] that turned into outright hostility and war two thousand years ago, more or less.

It is related by trustworthy sources that the other groups [aqvām اقوام ] overcame the group [qowm قوم ] of the Mongols and so slaughtered them that no more than two men and two women survived. Fleeing from their enemies, those two couples arrived in a wild place surrounded by mountains and forests, with only one narrow, rugged road leading in on every side, which made access very difficult. In the midst of those mountains was a rich grassy plain called Ergene Qūn; qūn means “mountain flank”, and ergene means “wall”, so Ergene Qūn means a “wall-like cliff”.

The two men were named Nüküz and Qiyan. They and their descendants remained there for years. They multiplied through intermariage, and each branch of them became known by a specific name and epithet, and became an obāq [oboq]. The obāq is what comes from a specific bone and lineage. These obāq also branched out. And at this time it is said among Mongol groups [aqvām اقوام ] that all those who came from these branches are more closely related to each other, and they are the Dürlükin Mongols.

The word Mongol was originally broken down into mong ol, which means “weary” and “simpleton”. In the Mongolian language qiyan refers to a strong torrent that tumbles down from a mountain to the ground and is swift, fast and powerful. Since Qiyan was a courageous warrior and very bold, this word was made his name. Qiyat is the plural of qiyan. His closest descendants in the direct line were called Qiyat in ancient times. When this group became numerous in those mountains and forests, and the land was constraining them, they took counsel with each other to figure out how to get out ot that narrow prison.

They found a place in the mountains where there was an iron mine, where they always used to smelt iron. They gathered together and brought loads of kindling anc charcoal from the forest. Then they killed seventy horses and oxen, skinned them, and made ironsmiths’ bellows from their skins. They placed the huge amount of kindling and charcoal at the base of the cliff and so arranged it that they could cause the seventy large bellows to blow at once, and thus the cliff was melted, producing immeasurable quantities of iron and opening a road, through which they moved out. From that stricture they emerged into a spacious plain.Footnote 37

و آن قوم را که در قدیم ایشان را مغول گفته اند به کما بیش دوهزار سال پیش از این با دیگر اقوام اتراک مخاصمتی و معاندتی افتاده، و به مکاوحت و محاربت انجامیده.

روایتی است از معتبران معتمدالقول که دیگر اقوام بر اقوام مغول غالب آمدند و ایشان را چنان به قتل آورده اند که دو مرد و دو زن زیادت نماندند. و آن دو خانه از بیم خصم گریخته به موضعی صعب رفتند که پیرامن آن همه کوهها و بیشه بود و از همه جوانب جز یک راه باریک صعب که به دشواری و مشقّت تمام در آنجا توان رفت نبوده . و در میان آن کوهها صحرایی نزه پرعلف بوده نام آن موضع ارگنه قون . معنی قون کمر کوه باشد و ارگنه تند، یعنی کمری تند.

و نام آن دو کس نکوز و قیان بود، سالها ایشان و ذریّت ایشان در آنجا مانده اند؛ و به واسطۀ امتزاج و ازدواج بسیار شده، و هر شعبه ای از ایشان به نامی و لقبی معیّن مشهور گشته و اوباقی شده . و اوباق آنست که از استخوان و نسلی معیّن باشد . و آن اوباقها دیگرباره منشعب گشته . و این زمان پیش اقوام مغول چنان مقرّر است که آنچه از این شعبه ها پدید آمده اند، ایشان به یکدیگر نسبت خویشی بیشتر دارند، و مغول درلکین ایشان اند.

و لفظ مغول در اصل مونگ اول بود، یعنی فرومانده و ساده دل . و در لغت مغول، قیان سیل قوی باشد که از بالای کوه به نشیب زمین روان شود و تند و تیز و قوی باشد. و چون قیان، بهادر و شجاع و بغایت دلاور بوده، این لفظ نام وی نهاده اند. و قیات جمع قیان است . آنچه از آن نسل به اصل او نزدیکتراند ایشان را در قدیم قیات گفته اند. و چون در میان آن کوه و بیشه آن گروه انبوه شده اند و فسحت عرصه بر ایشان تنگ و دشوار گشته، با یکدیگر کنگاچ کرده اند که به حسن تدبیر و رای مشکل گشای از آن در بند سخت و درغالۀ تنگ چون بیرون آیند.

موضعی را در آن یافته اند که کان آهن بود و همواره از آنجا آهن می گداخته اند. باتّفاق جمع شده اند و از بیشه هیمۀ بسیار و انگشت به خروار گرد کرده، و هفتاد سر گاو و اسب کشته و پوست درست از آن کشیده و دم های آهنگران ساخته، و هیمه و انگشت فراوان در آن بن کمر نهاده و موضع چنان ترتیب کرده که بدان هفتاد دم بزرگ بیکبار می دمیده اند، تا آن کمر گداخته گشته و آهن بی اندازه از آن حاصل شده و راهی بادید آمده، و ایشان به جمعیّت کؤچ کرده اند و از آن تنگنای به فراخ جای صحرا آمده.

Several pages later, Rashīd ad-Dīn adds about the Ergene Qūn:

And among all those who came out from there, there was an important commander who was the leader and lord of some groups [aqwām اقوام ], named Bōrteh Chīna [Börte Chino].Footnote 38

و از آن جمله از آنجا بیرون آمدند امیری معتبر بوده مقدّم و سرور بعضی اقوام، بورته چینه نام.

The Chinggisid khan of Khiva and historian Abū'l-Ghāzī Bahādur Khān (1603–1663) gives a much more detailed version of this myth, with some variations.Footnote 39 He thus indicates that it was a blacksmith who discovered the iron vein through which a passage was possible, and that

At that time, the king who ruled over the Mongols was Bōrteh Chīna [Börte Chino], a descendant of Qiyān from the Qōrulās branch [ūrūq].Footnote 40

اول وتدا مغولنینك پادشاهی برته چنه قیان نسلی و قورلاس اوروقیندین ایردی

This Börte Chino, “Blue Wolf” in Mongolian, is none other than the ancestor of Chinggis Khan according to the genealogy that opens the Secret History of the Mongols;Footnote 41 I will come back to this later. In both of these very closed versions of the myth we find, here again, a terrible defeat to which very few survive, the escape of the survivors to a place of refuge, almost enclosed and extremely difficult to access, where they gradually gain in number and strength, before finally emerging.Footnote 42

Raverty's note to the translation of the Ṭabaqāt-i Nāṣirī implies that Jūzjānī misunderstood or misremembered this legend, and inadvertently integrated it into the body of Chinggis Khan's story; this is at least the opinion held by most researchers who, probably misled by Raverty's comment, saw it only as a distortion of the original myth.Footnote 43 However, in view of the easily traceable parallel between the text of Jūzjānī on the one hand, and those of Plano Carpini and C. de Bridia on the other, this seems quite impossible to me. Both Jūzjānī and Plano Carpini (and C. de Bridia) report the authentic story of a legendary episode of Chinggis Khan's life, forged at the Mongol court, whose plot follows the myth of the Ergene Qūn as it has reached us through Rashīd ad-Dīn and Abū'l-Ghāzī. It remains to be seen why this myth has been taken up in this form.

We can try to solve the enigma first by comparing these texts with other Turko-Mongol myths. Several other founding myths, next to that of the Ergene Qūn, are indeed known to us.Footnote 44 Thus the origin myth of the Kimeks, which is transmitted to us by Gardīzī in the 11th century:

[As for the Kimeks] their origin was this, that the ruler of the Tatars died leaving two sons. The elder son seized the kingship and the younger son became envious of his brother. The name of that younger brother was Shad. He intented to kill his older brother, but was unable to do so. [After which] he became afraid for his life. This Shad had a young girl, who was his lover. He took away this young girl and fled from before his brother. He arrived to a place where there was a great river, many trees and abundant game. He got off his horse and pitched his tent there. Every day that man and young girl, both of them, would go hunting and they would eat the flesh of the game and they would make garnments of skins of sable, grey squirel, and ermine, until seven men from among the clients [muvalidān مولدان ] of the Tatars came to them. The first was Imī; the second, Imāk; the third, Tatār; the fourth, *Bayāndur [B.lānd.r بلاندر ]; the fifth, Qifchāq; the sixth, Laniqāz; the seventh, Ajlād. These were a party [qowmī قومی ] who had taken their masters’ horses to graze, but where the horses were there was no pasturage left and sot hey had gone in search of grass in the direction where Shad was. When the young girl saw them she came out and said “ertish”, which means “dismount yourselves” for which reason this river has been named Ertish [Irtysh].

When the party recognized that young girl, they all dismounted and put up their tents. When Shad returned, he brought much game and entertained them, [so that] they stayed there until winter. When the snow came they were unable to go back, but there was abundant grass in that place. They stayed there all winter, and when the world became fair [again] and the snow went away, they sent a person to the camp of the Tatars, that he might bring them news of that party. But when he arrived, he saw that the entire place had become desolate and devoid of people, for the enemy had come and plundered and killed the whole nation [hama qawm همه قوم ], except for that remnant which had been left and came forward towards him from the foot of the mountain. [These] he told of Shad [ḥal-i Shad حال شد recte khāli shod خالی شد ] and his own comrades, and all that folk set out for the Ertish. When they arrived there they greeted Shad as their chief and held him in awe. Then other folk [qawm قوم ] who heard this news began to come, until seven hundred people gathered and stayed a long time in Shad's service. Afterwards, when they became [more] numerous they spread out over those mountains and became seven groups [qabīla قبیله ], named after those seven persons we have mentioned.Footnote 45

اصل ایشان آن بود. است که مهتر تتاران بمرد، و او را دو پسر ماند. مهتر پسر پادشاهی بگرفت، کهتر پسر از برادر حسد کرد. و این کهتر را شد نام بود، و قصد کرد که برادر مهتر را بکشد، نتوانست . برخویشتن بترسید، و کنیزکی بود این شد را، عشیقۀ او بود، و آن کنیزك برداشت، و از پسش برادر بگریخت، و بجایی شد که آنجا آب بزرگ بود و درختان بسیار، و صید فراوان، و آنجا خرگاه بزد و فرود آمد، و هر روز این مرد و کنیزك هر دو تن صید کردندی، و از آن گوشت صید همی خوردندی، و جامه از پوست سمور و سنجاب و قاقم همی کردندی، تاهفت تن از مولدان تتار بنزدیك ایشان یکی ایمی، دو دیگر ایماك، و سه دیگر تتار، و چهارم بلاندر، و پنجم خفچاق، و ششم لنقاز، و هفتم اجلاد. و این قومی بودند که ستوران خداوندان بچرا آورده بودند، و آنجا که ستور بود، چراخور نمانده بود. پس بر آن جانب شدند که شد بود بطلب گیاه . و چون کنیزك ایشان را بدید بیرون آمد و گفت : ارتش یعنی فرود آیید، و آن آب را بدین سبب ارتش نام کردند

و چون این قوم آن کنیزك را بدانستند همه فرود آمدند، و خرگاهها بزدند. و چون شد فراز رسید، صید فراوان آورد و ایشان را مهمان داشت، آن آنجا بماند تا زمستان . و چون برف بیامد نتوانستند بازگشت، و آنجا گیاه فراوان بود. همه زمستان آنجا ببودند، و چون جهان خوش گشت و برف برخاست، یکتن را به بنگاه تتاران فرستادند تا خبر آن قوم بیارد . چون آنجا رسید، همه جایگاه را ویران گشته دید و از مردم خالی شده . از آنچه دشمن آمده بود، و همه قوم را غارت کرده بود و بکشته، و آن باقی که مانده بودند، از کوه پایها سوی او آمدند، و این مرد خالی شد، و با یاران خویش بگفت . آن همه مردمان روی سوی ارتش نهادند. و چون آنجا رسیدند، برشد بریاست سلام کردند، و او را بزرگ داشتند، و دیگر قوم که این خبر بشنیدند، به آمدن گرفتند، تا هفتصد تن گرد آمدند، و روزگار دراز اندر خدمت شد بماندند . پس چون انبوه شدند، اندران کوهها بپراگندند، و هفت قبیله شدند به نام این هفت تن که یاد کردیم.

A significant number of salient elements of this myth can be found in the account reported by Ibn ad-Dawādārī, a 14th century Mamluk writer, who claims to have received his informations from a book held in great respect by Mongols and Qipchaqs, the Ulū Khan Atā Bitigi or “The Book of the Great Father King”. According to Ibn ad-Dawādārī, a woman from Tibet gave birth to a son who was quickly carried into the sky by an eagle to a forest at the foot of Mount Qara Tagh, near a lake where game was abundant, and where he was raised by wild animals. One day, a group of seven Tatars fleeing the destruction of their people went astray in the forest, and was saved by the young boy, who took a wife among them. From the wild boy and the tatar girl was born the ancestor of the Mongols, called Tatar Khan, whose lineage continues to Chinggis Khan, while

the descendants [of the group] reproduced and multiplied on this land and they spread out around the lake.Footnote 46

و توالدوا، و کثر نسلهم فی تلك الاُرض، و تفرقوا حول تلك البحیرة

After several generations, these new Tatars came into contact with the “Turks” of the Alṭūn Khan, and submitted to him.Footnote 47

All these texts contain the same narrative schema, which can be summarized as follows:

1- a defeat against a neighbouring people leads to the extermination of the nation.

2- only a handful of survivors escapes the massacre.

3- they find refuge in a remote place that is difficult to access or even completely enclosed.

4- the group of refugees is growing in strength and number.

5- the group chooses a leader.

6- the group, which has become powerful enough, leaves the refuge.

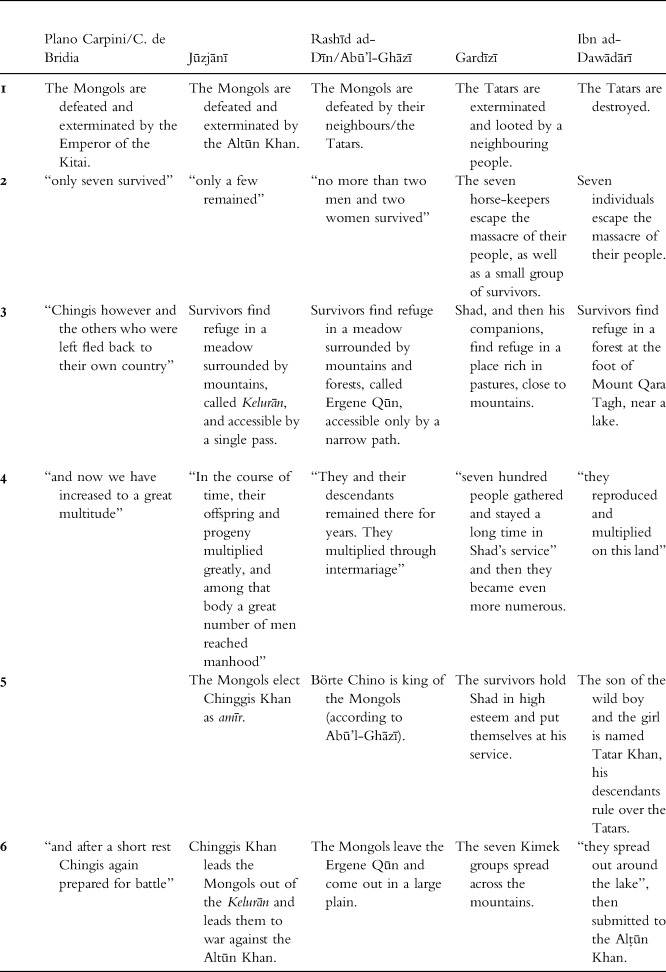

The recurrence of these elements is particularly visible when a comparative table is drawn up between these different sources:

The common structure between these founding myths, on the one hand, and the obviously legendary account of Chinggis Khan's rise told by Plano Carpini and Jūzjānī, on the other hand, is very clear. However, the way by which the founding myth passed to a legend that is part of the succession of historical events leading to the formation of the Mongol Empire remains obscure for the time being.

Legend and propaganda: the Türk case:

To better understand, it is probably necessary to take a detour through the origin myth of the Türks. This one is transmitted to us by two Chinese sources in generally similar versions, with some variations: the Zhoushu 周書 and the Beishi 北史. I quote here the Beishi version, slightly more detailed:

The ancestors of the Türks lived to the west of the Western Sea. They constituted an independant group [buluo 部落]. No doubt they are a detached branch of the Xiongnu. They wore the surname [xing 姓] of the Ashina family [shi 氏]. Later they were defeated by a neighboring State, which completely exterminate their lineage [zu 族]. There was a boy, who was about ten years old. The soldiers, in view of his youth, could not bring themselves to kill him. So they cut off his feet and arms, and left him in a marsh. There lived a she-wolf who fed him with meat. When he grew up he had sexual intercourse with her, and she became pregnant. The king learned that this boy was still alive, and dispatched someone to kill him. The envoy saw the she-wolf with the boy and wanted to kill her as well. But then it was as if a spirit had suddenly transported the wolf east of the Western Sea. She landed on a mountain northwest of Gaochang. In the mountain there was a cave, and in the cave there was a plain covered with rich vegetation, stretching over several hundreds of li, surrounded on all four sides by mountains. The wolf took refuge inside and later gave birth to ten boys. The boys grew up and took wives from the outside. Each of the descendants took a surname, and one called himself Ashina. He was the cleverest among them and he became their ruler. At the entrance to the camp they [the Türks] place a wolf-headed banner to show that they have not forgotten their origins. Little by little they constituted several hundred families. Several generations later a certain Axian-she [Axian shad] led the group [buluo 部落] out of the cave and submitted to the Ruanruan [Rouran].Footnote 48

突厥者,其先居西海之右,獨為部落,蓋匈奴之別種也。姓阿史那氏。後為隣國所破,盡滅其族。有一兒,年且十歲,兵人見其小,不忍殺之,乃刖足斷其臂,棄草澤中。有牝狼以肉餌之,及長,與狼交合,遂有孕焉。彼王聞此兒尚在,重遣殺之。使者見在狼側,并欲殺狼。於時若有神物,投狼於西海之東,落高昌國西北山。山有洞穴,穴內有平壤茂草,周廻數百里,四面俱山。狼匿其中,遂生十男。十男長,外託妻孕,其後各為一姓,阿史那即其一也,最賢,遂為君長。故牙門建狼頭纛,示不忘本也。漸至數百家,經數世,有阿賢設者,率部落出於穴中,臣於蠕蠕。

We find again the same structure as for the other stories:

1- The Türks suffer a crushing defeat and are massacred.

2- Only a ten-year-old boy survives and is fed by a she-wolf with whom he has sexual relations (which acts as the primary couple from whom the race can be reborn).

3- The pregnant wolf finds refuge in a cave, in which there is a plain surrounded by mountains.

4- The she-wolf gives birth to ten boys; they grow up, get married, and several generations follow one another.

5- The group living in the cave elects Ashina as its leader.

6- The group leaves the cave with Axian shad at its head.Footnote 49

The filiation between the original myth of the Türks and that of the Ergene Qūn has been noted several times since Pelliot.Footnote 50 It was denied by Denis Sinor, who sought to historicize the Türk myth and saw no historical basis in the Mongol one,Footnote 51 and was particularly studied and established by Devin DeWeese, who correctly showed how the Türk myth was linked to a matrix common to the steppe peoples, from which the Mongol myth in its many variants also derived, as well as the Kimek one.Footnote 52 Nevertheless, I think that not everything that can be drawn from the comparison between these different sets of myths has yet been exhausted. So far we have confined ourselves to comparing stories that present themselves to us as founding myths, without taking into account others, who share their structure and characteristics, such as the passages of Plano Carpini and Jūzjānī that we are discussing here. Another fundamental source for the history of the Türks was thus over looked, whereas it is indeed a foundation tale and includes some passages directly modelled on the founding myth, in this case that of the Türks: that is namely the Orkhon inscriptions.

The eastern side of the Kül Tegin inscription, commissioned by Bilge Khagan (716–734) in 732, tells the story of Qutlugh Elterish Khagan's revolt against the Chinese, leading to the founding of the Second Türk Empire (682–742):

[The Turkish people] were about to be annihilated. But the Turkish Tengri above and the Turkish holy earth and water [spirits below] acted in the following way: in order that the Turkish people would not go to ruin and in order that it would be an [independant] nation again, they held my father Elterish Khagan, and my mother El Bilge Khatum, at the top of heaven and raised them upwards. My father, the kaghan, went off with seventeen men. Having heard the news that [Elterish] was marching off, those who were in towns went up mountains and those who were on mountains came down; thus they gathered and numbered to seventy men. Due to the fact that Tengri granted [them] strength, the soldiers of my father, the kaghan, were like wolves, and his enemies were like sheep. Having gone on campaigns forward and backward, he gathered together and collected men; they all numbered seven hundred men. After they had numbered seven hundred men, [my father, the kaghan] organized and ordered the people who had lost their state and their kaghan, the people who had turned slaves and servants, the people who had lost the Turkish institutions, in accordance with the rules of my ancestors.Footnote 53

yoqadu barÏ̄r ärmis üzä türük täŋrisī, türük ïduq yirī subi anča etmis: türük bodun toq bolmazun tiyin, bodun bolčun tiyin, qaŋïm il-teris qaγanïγ, ögüm il-bilgä qatunuγ täŋrï töpüsīntā tutup yüg(g)ärü kötürmis ärinč. qaŋïm qaγan yiti yegirmi ärin tašïqmis. tašra yorïyūr tiyin kü äsidip balïqdaqï taγïqmis, taγdaqï inmis, tirilip yetmis är bolmis. tänŋrï küč birtük üčün qaŋïm qaγan süsī böri täg ärmis, yaγÏ̄sī qoń täg ärmis. ilgärtü qurïγaru süläp ti[r]m[iš], [q]amaγī yeti yüz är bolmis. yeti yüz är bolup elsirämis qaγansïramis bodunuγ, küŋädmis quladmis bodunuγ, türük törǖsīn ičγïnmis bodunuγ äčūm apām törǖsīncä yaratmis bošγurmis.

The inscription then passes to the reign of Qapaghan Khagan who succeeds his brother Elterish, during which Bilge was a shad,Footnote 54 to reach the enthronement of the latter, who inherits a difficult situation and launches a series of military campaigns “in order to nourish the people”, “who had gone [in almost all directions]” and “came back utterly exhausted, without horses and without clothes”.Footnote 55

At first glance, there is little proximity to the origin myth mentioned above. This is without taking into account another part of the legend which, in the Zhoushu, is reported immediately after the first:

Some also tell that the ancestors of the Türks originally lived in the country of Suo, north of the Xiongnu. The prince of this community [buluo 部落] was named Abangbu, and he had seventeen brothers. One of them was called Yizhini-shidu [Yizhini shad], and he was born from a wolf. Bangbu and his brothers were all stupid, and their state was destroyed. Ni-shidu [(Yizhi)ni shad] stood out because, touched by fortune, he had the power to control the wind and the rain. He married two women said to be the daughters of, respectively, the Spirit of the Summer and the Spirit of the Winter. One of them became pregnant and gave birth to four sons. One of them changed into a swan, another established a state between the rivers Afu and Jian, called Qigu [Kirghiz]. Another fouded a state along the Chuzhe river. The fourth dwelled on the mount Jiansi-Chuzhe-shi, and he was the eldest. On this mountain lived also a group from the race of Abangbu and, as they were destitute, they suffered greatly from the cold. The eldest made fire for them, warm them up and kept them all alive. Then they collectively submitted to the eldest, they elected him ruler, and they called him Türk. It was Naduliu-she [Naduliu shad]. Naduliu had ten wives. Their sons adopted the surnames of their [respective] mothers. Ashina was the son of one of the secondary wives. Naduliu died, and the sons of the ten mothers wanted to choose one of themselves to ascend the throne. So they gathered under a great tree, and all agreed on a rule: to jump to [the top of] the tree, and whoever would jump the highest, they would make him king. The son of Ashina [i.e. of the secondary wife named like this] was young, so he jumped higher, and they took him as ruler. They called him Axian-she [Axian shad].Footnote 56

或云突厥之先出於索國,在匈奴之北。其部落大人曰阿謗步,兄弟十七人。其一曰伊質泥師都,狼所生也。謗步等性竝愚癡,國遂被滅。泥師都既別感異氣,能徵召風雨。娶二妻,云是夏神、冬神之女也。一孕而生四男。其一變為白鴻;其一國於阿輔水、劍水之間,號為契骨;其一國於處折水;其一居踐斯處折施山,即其大兒也。山上仍有阿謗步種類,竝多寒露。大兒為出火溫養之,咸得全濟。遂共奉大兒為主,號為突厥,即訥都六設也。訥都六有十妻,所生子皆以母族為姓,阿史那是其小妻之子也。訥都六死,十母子內欲擇立一人,乃相率於大樹下,共為約曰,向樹跳躍,能最高者,即推立之。阿史那子年幼而跳最高者,諸子遂奉以為主,號阿賢設。

For Sinor, this is a tradition not only distinct from the one I have already mentioned, but also “which may originally have been hostile” to the previous one, which he believes would probably have been the most widespread among the Türks.Footnote 57 I would tend to think the opposite: in my opinion, these two passages reflect the same mythical whole.Footnote 58 Certainly, they show significant variations from each other. But more than as two distinct legends, these stories appear to me as two versions of the same myth, which also corresponds to different levels of the latter, hence their apparent disparity. The transmission of these two distorted variants by perhaps different informants would have made them two distinct traditions under the pen of the author of the Zhoushu.Footnote 59

With this in mind, let us compare the Orkhon inscriptions with the origin myth of the Türks. The Kül Tegin inscription tell us that the “Turkish people were about to be annihilated”, in the same way as in the myth, where the ancestors of the Türks are exterminated except for a young boy; the second account, according to which Abangbu and his brothers were stupid, and that consequently their state was destroyed, finds an echo in the previous lines of the inscription, where it is written that to the first glorious khagan of the First Türk Empire of the 6th century succeeded “unwise” and “bad khagans”, and that “their buyruqs, too, were unwise and bad”, leading to the ruin of the empire and submission to China.Footnote 60 Elterish Khagan and his wife El Bilge Khatum, protected by Heaven (Tengri) and earthly geniuses, appear as the primordial couple from whom the people are reborn.Footnote 61 Elterish, who rises up with seventeen men, is likened to Yizhini shad and his seventeen brothers.Footnote 62 This initial group of seventeen supporters grew gradually by adding partisans, passing to seventy men, then to seven hundred, just as in the myth the group grew over the generations.Footnote 63

We can try to take the comparison even further. If Elterish is assimilated to Yizhini shad, then his successor, Qapaghan, should be identified with Yizhini's successor, Naduliu shad, who makes fire and thus saves the cold the group of destitute people from Abangu’s race. The inscription says:

After my uncle, the kaghan [Qapaghan], succeeded to the throne, he organized and nourished the Turkish people anew. He made the poor rich and the few numerous.Footnote 64

äčim kaγan olurupan türük bodunuγ yičä itdin igit(t)i. čiγńïγ bay qïltï, azïγ üküš qïltï.

The expression, however, is not specific to Qapaghan: it is found in a few lines below, and this time Bilge applies it to himself, while after inheriting a difficult situation and the Türk people are once again powerless, he finally rectifies the situation after several military campaigns.Footnote 65 Perhaps Naduliu's role as a saviour is shared in the inscriptions by the uncle and nephew, but all in all, this identification is not very conclusive.

Now it can be argued more convincingly that Bilge, who is both the sponsor, the speaker, and the main protagonist of the Orkhon inscriptions, is identified with a character who was perhaps the most important figure in the Turkish origin myth, or was at least sufficiently important to appear in both versions transmitted by Chinese sources: Axian shad.

Peter Golden notes that in the name of Axian shad 阿賢設, the character xian 賢, “wise”, is the same as the one used in the Shiji 史記 about the “Wise Kings of the Left and of the Right”, zuo you xian wang 左右賢王, being the rank immediately lower than that, supreme, of chanyu 单于 in the administrative and political hierarchy of the Xiongnu, and he makes the connection with the Turkish bilge, “wise”.Footnote 66 Therefore, Axian-she could be not the phonetic transcription into Chinese of an approaching Turkish name, but a translation:Footnote 67 moreover, if in addition, the character a 阿 is assumed to be an abbreviation of the surname AshinaFootnote 68 阿史那, Axian-she can be translated by Ashina Bilge shad, “the wise Ashina shad”.Footnote 69 Bilge is not a name, it is a regnal title, just like Axian, since the second story tells us that Ashina was so styled after he became king; it is constantly found in the royal onomastic of Türks and the Uighurs, insofar as wisdom is, not surprisingly, associated with the ability to govern in the steppic tradition, beginning with the Orkhon inscriptions. As a result, Bilge Khagan, about whom Chinese sources tell us that before his enthronement his name was Mojilian 默棘連,Footnote 70 did not choose his regnal name because of Axian shad, or at least not only. Nevertheless, if xian 賢 indeed translates Bilge, the homonymy with this mythical character has certainly served the khagan in the assertion of his power, contested for a time. The ascent to the throne of Bilge is not, in fact, the immediate and smooth ascent described in the inscriptions: at the death of Qapaghan, Chinese sources tell us, it was first his son Bögö (Fuju 匐俱)/Inäl (Yinie 移涅) Khagan, whom his father had previously made small khagan, who succeeded him; Kül Tegin revolted, took the lead of an army, killed Bögö, had his supporters massacred, and installed his elder brother, Bilge, at the head of the empire.Footnote 71 By subtly asserting himself as a new Axian shad, Bilge certainly intended to claim a legitimacy equal to that of the mythical hero: that of a sovereign chosen by his people according to his merit.

For the comparison to be complete, the element of the cave, or at least the inaccessible refuge, present in the myth, is still missing from the inscriptions. However, the entire southern face of Kül Tegin's inscription is dedicated to praising the merits of the Ötüken mountains, the only place from which the Türks can be ruled, and out of which death awaits.Footnote 72 I think that the Ötüken mountains, at the foot of which is the Orkhon Valley, represent in the inscriptions the refuge from which the mythical ancestors of the Turk came out. This association of Ötüken with the ancestral place dates back to the First Turkish Empire. We read in the Zhoushu:

The khagan usually dwells in the Yudujin [Ötüken] mountains. His tent palace is open to the east, because it is in this direction that rises the sun, which they [the Türks] worship. Every year, he leads all his nobles into a grotto to offer a sacrifice to their ancestors.Footnote 73

可汗恆處於都斤山,牙帳東開,蓋敬日之所出也。每歲率諸貴人,祭其先窟。

One can perhaps infer that the cave in question was in the Ötüken.Footnote 74 From that time onwards, the Ötüken would therefore have been symbolically associated with the ancestral residence of the Turks, the grotto mentioned in the Zhoushu representing the mythical cave of the origins.Footnote 75 In the Kül Tegin inscription, Bilge also calls the Türks the “people of the sacred Ötükän mountains”.Footnote 76

That the Orkhon inscriptions do indeed follow the pattern of the origin myth seems to me, moreover, to be proved by the striking similarity that exists between the already mentioned passage on the eastern side of the Kül Tegin inscription and the origin myth of the Kimeks. Probably the latter derives from the original form of the Türk myth, to which we have access only by distorted versions, through Chinese sources, whereas the original form is the one that inspires the Orkhon inscriptions.Footnote 77

Furthermore Étienne de la Vaissière convincingly demonstrated how the discourse carried by the inscriptions on the value of the Ötüken was in fact pure rhetoric, aimed at masking a much less flattering reality, namely that the Türks of the Second Empire, formerly centred on the Yinshan Mountains and the Hohhot Valley (the Choghay Mountains and the Tögültün Valley of the inscriptions), had to retreat north of the Gobi Desert under Chinese pressure in 708.Footnote 78 The same is true of the reminder of the foundation of the First Empire by the two brothers Bumïn and Ishtemi, in whose footsteps the other two brothers Bilge et Kül Tegin seek to follow.Footnote 79 The implicit call to the legend of origins is part of the same logic of imperial propaganda, presenting the creation of the Second Turkish Empire and the enthronement of Bilge Khagan as events with a founding power as strong for the community as the mythical birth of the first Ashina and the exit of their mountain refuge.

The construction of a mythical Chinggis Khan:

The Türk case of a transposition of the original myth into the political narrative of the foundation of the Second Türk Empire makes it possible to understand what the passages of Plano Carpini's Ystoria Mongalorum or Jūzjānī's Ṭabaqāt-i Nāṣirī are. They are not vague echoes distorted to the point of no longer being related to historical reality. The intermediaries from whom these authors gleaned their information were well informed and had this curious account of Chinggis Khan's defeat from Mongol sources. It is simply not about history, as we understand it. To study these excerpts, we can indeed apply Devin DeWeese's statement about Ötemish Ḥājjī’s account of Özbek Khan's conversion to Islam: “Underlying the supposition that some ‘historical core’ underlies a ‘legendary’ account such as that of Ötemish Ḥājjī is the assumption that individuals and communities are inclined to organize and remember their experience first and foremost as history”.Footnote 80

The constitution of the Mongol Empire by Chinggis Khan, as well as that of the Second Türk Empire by Elterish, Qapaghan and Bilge, was a major event that was not only recorded in historical sources in the form of a chronicle, such as the Secret History or the Jāmi‘ at-tavārīkh, based on accounts of what may have actually happened according to witnesses, but has also been translated into narratives using the material of the myth to reflect the meaning and significance of this event for the community of the nomadic subjects of the empire: that of a new foundation, equal in its meaning to the very origin of the community that the myth tells. As I have already stated above, the passages in question by Plano Carpini, C. de Bridia and Jūzjānī reflect a legend about the life and conquests of Chinggis Khan, forged at the Mongol court, at the latest in the interregnum following the death of Ögödei (1241) and preceding the enthronement of Güyük (1246), and this for political purposes. While perhaps masking an obscure, and obviously not very glorious, episode of the Mongol conqueror's career, it serves to strengthen his legitimacy and that of his lineage by using the sacred repertoire of the myth to describe his rise. It is anchored in a real geography, since in the same way that the Türks had assimilated the Ötüken to the vast plain located in the cave of their ancestors, the Ergene Qūn is transposed into the sacred heart of the Mongol Empire, the Kerülen Valley, easily recognizable behind the metathetized form Kelurān of Jūzjānī’s text.Footnote 81

Just as the Orkhon inscriptions probably identify Bilge with his ancestor Axian shad, this legendary narrative first assimilates Chinggis Khan to his ancestor, Börte Chino.Footnote 82 We have already seen that Rashīd ad-Dīn mentions this character as an “important commander” among those who left the Ergene Qūn. Moreover Abū'l-Ghāzī makes him the king of the Mongols when they leave the Ergene Qūn.Footnote 83 He therefore clearly occupies a function parallel to that of Axian shad in the Türk myth, that of the sovereign leading his people outside the enclosed refuge to their new home. Now Jūzjānī writes that the Mongols who took refuge in the Kelurān elected Chinggis Khan commander (amīr) (though he was already leading the revolt against Altūn Khan at the time of their crushing defeat) so that he would lead them to victory. The circumstances of the latter take the parallel between this story and the myth of the Ergene Qūn even further: Concerned about the growing strength of the Mongols, Altūn Khan had the only pass leading to the Kelurān guarded by an army of 300,000 riders, which Chinggis Khan and the Mongols bypassed by going through a traverse path,Footnote 84 as well as in the myth the Mongols, prisoners of their refuge, end up coming out of it with a trick, by “a passage just wide enough to pass a loaded camel”, as Abū'l-Ghāzī says.Footnote 85

The nature, lupine or human, of Börte Chino, “Blue Wolf”, is a subject of debate.Footnote 86 Among Muslim authors, such as Rashīd ad-Dīn and his followings, he is undoubtedly a human being, as well as in the later Mongol sources of the 16th and 17th centuries, which link him to the lineage of the legendary Buddhist kings of India and Tibet;Footnote 87 but this is probably a later humanization, in order to make the tradition compatible with Islam or Tibetan Buddhism.Footnote 88 Indeed the Secret History is more ambiguous. This is because Börte Chino is probably both wolf and human: as Roberte Hamayon elegantly puts it, “the founder of the tribe, […] is animal by essence but human by fonction, inasmuch as he begets the forefathers of the clan. He originates from the animal part of the supernatural world and takes place above the ancestors in the human part of it”.Footnote 89

The Secret Story begins by telling that Börte Chino and his wife Qo'a Maral, “Fallow Doe”, settled on the Burqan Qaldun after crossing the sea, and from there gave birth to the line leading to Chinggis Khan.Footnote 90 This account of a migration, coupled with the role of leader, i. e. of guide, of the Mongols in their exit from the Ergene Qūn according to the myth, suggests that the blue wolf Börte Chino as well as his wife the fallow doe were originally guiding animals, as found elsewhere in various nomadic traditions: in the Oghuz Nāma written in Uighur from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, a grey wolf guides Oghuz Khagan's always victorious armies;Footnote 91 Michael the Syrian says in his Chronicle that the Oghuz emigrated from their mountains – called “the Breasts of the Earth” and into which one could only enter or leave through two doors – led by “a kind of animal similar to a dog, which walked before them”, and which indicated when they had to move by saying to them “gūš!”, “Stand up!” (Turkish -göč/köč: “to migrate”, “to move a camp”), and when to stop;Footnote 92 Jordanes, quoting Priscus, says that the Huns found a way out of the marshes where they had been relegated towards Scythia, following a deer that appeared to hunters;Footnote 93 while during their migration the Tuoba wanted to settle in a deep and mountainous valley that was hard to reach, an animal spirit which was shaped like a horse and bellowed like an ox appeared and led them further south for several years before disappearing;Footnote 94 at the end of Juvaynī's excursus on Buqu Khagan, it is said that the Uighurs settled in Beshbalik after hearing the cries of horses, camels, dogs, cattle and birds in which they recognized the expression “köch, köch !”, pushing them to emigrate;Footnote 95 some “Tartars” reported to Riccoldo of Monte Croce that God took them out of their original lands, sending them as messengers “a beast and a bird of the desert ̶ namely a hare and an owl”, which indicated to a hunter a passage through the mountains.Footnote 96

In addition, the crossing of the sea by Börte Chino and Qo'a Maral can be compared to the crossing of the Western Sea by the ancestral wolf of the Türks, which highlights the relationship between Mongol tradition and the Türk myth, but also suggests that the wolf in question was also initially intended to be a guiding animal.Footnote 97 That Chinggis Khan was indeed assimilated to Börte Chino is confirmed to us by another source, the account of Hayton that I mentioned above, which refers to a similar crossing of the sea by Chinggis Khan at the head of his people: it is said that the Mongols spent a night in prayer before the sea at the foot of the Mount Belgian, and that in the morning God had made the sea withdraw over a width of nine feet, giving the Mongols a passage toward a rich plain.Footnote 98 The Armenian monk gives this legend a Mosaic glaze, in order to link the Mongols to the Christian history of salvation, but its background is, as we have seen, quite Central Asian.Footnote 99

The guiding animal is a being belonging to the supernatural world, sent by Heaven. Börte Chino is said by the Secret History to be “born with his destiny ordained by Heaven Above”,Footnote 100 and his blue colour (börte : “blue, blue-grey”) expresses its heavenly character. The implicit assimilation of Chinggis Khan to Börte Chino in turn implies the divine character of the person and mission of the conqueror as the guide and sovereign of the Mongol people. It is therefore perfectly articulated with all the imperial Chinggisid propaganda, which constantly insists on the protection of Heaven, Tengri, enjoyed by Chinggis Khan and his lineage, who are the agents on Earth of the heavenly will.Footnote 101

This narrative then assimilates Chinggis Khan to the blacksmith, a character absent from the version of the myth given by Rashīd ad-Dīn, but very present in that of Abū'l-Ghāzī, in which it is he who discovers the iron mine, and who probably inspires the way to make it melt.Footnote 102 This assimilation is made explicit by Hayton, who writes that Chinggis Khan was indeed a blacksmith: “povre home fevre, qui avoit non Canguis”.Footnote 103 Hayton is not, however, the only one to echo a tradition that makes the great Mongol conqueror a blacksmith, since on the contrary it can be found in various sources, independent of each other: in the Franciscan William of Rubruck,Footnote 104 the Byzantine chronicler Georgios Pachymeres,Footnote 105 the Mamluk historians an-Nuwayrī, aṣ-Ṣafadī and Ibn ad-Dawādārī,Footnote 106 and finally in the traveler Ibn Baṭṭūṭa.Footnote 107 Perhaps here again in the same way as in the Türk case, with the homonymy between Bilge Khagan and Axian shad, such assimilation has undoubtedly been facilitated by Chinggis Khan's birth name, Temüjin: this name is unquestionably built on the Turko-Mongolian root temür, “iron”, followed by the suffix -jin, former allomorph of -či(n) used to designate vocation names, which makes it the equivalent of the Turko-Mongolian temürčin/tämürči, “blacksmith”.Footnote 108

Chinggis Khan's identification with a blacksmith is therefore not without foundation, as it has long been believed,Footnote 109 nor does it come from a popular etymology, since it is ultimately based on a deliberate match between the myth of the Ergene Qūn and Chinggis Khan's rising to power.Footnote 110 It overlaps with the identification to Börte Chino, again making Chinggis Khan the one who ensures the exit of his people from their borders to a greater destiny. But there is more. Indeed, there are many traditions among the nomads of Central Asia to link the blacksmith to the shaman: like him, the blacksmith, by his mastery of iron and fire, is endowed with supernatural powers and has part with the spirit world.Footnote 111 To make Chinggis Khan a blacksmith is therefore to endow him with a sacred royalty whose power extends beyond the political sphere to the fields of magic and religion.Footnote 112

The religious nature of the sovereign's power in connection with metallurgy can be detected from the description given by Rashīd ad-Dīn, immediately following the passage on the Ergene Qūn, of a metallurgical ritual specific to the Chinggisid family:

During the night before the new year, it is tradition and custom within Chinggīz Khān's uruq [family] to prepare ironsmiths’ bellows, a furnace and charcoal, then to bring a piece of iron to the red, which they strike on an anvil with a hammer to give it an elongated shape. After which they give thanks.Footnote 113

و در آن شب که سر سال نو باشد رسم و عادت اوروغ چنگگیز خان آنست که دم آهنگران و کوره و فحم ترتیب کنند، و قدری آهن را بتابند و بر سندان نهاده به مطرقه بزنند و دراز کنند و شکرانه گزارند.

The description of this same ritual can be found in Abū'l-Ghāzī where it appears even more explicitly as a commemoration of the exit from the Ergene Qūn:

[The Mongols] noted the time of the day and the month, and went outside. Since then, the Mongols have been celebrating this date: they throw a piece of iron into the fire and bring it to the red; first the khan takes the iron with pincers, puts it on an anvil and hits it with a hammer, then it is the turn of the begs. They venerate this day with fervour, explaining that it was then that they came out of the confinement and returned to their homeland.Footnote 114

کون نینك آی نینك ساعتین قراب تاشقاری چیفدی لار آندین بری مغول نینك رسمی تورور شول کون نی عید قیلورلار بیر پاره تیمورنی اوتغه سالب قیزل قیلورلار اوّل خان انبور بیرلان تیمورنی توتوب سندان اوستندا قویوب چوکوج بیرلان اورار آندین سونك بیك لار اول کونی عجایب عزبز توتارلار قبال دین چیقیب آتا یورتینه کیلکان کون تورور تیب

So we see that kings and nobles of the Chinggis Khan family became blacksmiths themselves every year for a night, and that it was a sacred performance. This ceremony finds parallels in the shamanic initiation rituals of contemporary times.Footnote 115 It is also reminiscent of the one described by the Zhoushu, led by the Türk khagan and gathering the nobility in the ancestral grotto, although the details are not known. There is no question of iron in the Türk myth, as reported to us by the various Chinese sources. However the Zhoushu says that after leaving the cave, the Türks “settled on the southern slope of the Jinshan [the Altai], and served as blacksmiths for the Ruru [Rouran]” 居金山之陽,為茹茹鐵工.Footnote 116 It can therefore be assumed that the metallurgical element was also present.

From this tradition comes undoubtedly, as Roux had suggested,Footnote 117 the strange passage found in Ṭabaqāt-i Nāṣirī of Jūzjānī, again, in which Chinggis Khan is depicted as a friend of demons, a practitionner of magic and scapulomancy, and being able to immerse himself in states of trance during which he predicted his victories. Which fits perfectly with the description of a shaman.Footnote 118 From this sacred nature of the royalty of the conqueror who is identified with a blacksmith also stems, I think, the misperception on the part of some Muslim authors of Chinggis Khan as the prophet of the Mongols. This idea can be found first in the Mamluk historian Ibn Wāṣil, then in the famous Damascene cleric Ibn Taymiyya, but also in the Persian historian Vaṣṣāf, who reports that the Jewish vizier of the Ilkhan Arghun (1284–1291), Sa‘ad ad-Dowla, encouraged him to found a new religion, by trying to convince him that he had inherited the gift of prophecy from his ancestor Chinggis Khan.Footnote 119

The blacksmith is also in a symbolic way the one who forges the new community, and binds its members together. Taken in this way, the enclosed place is therefore a matrix,Footnote 120 and more particularly a furnace or a forge where this new community is shaped, and of which the blacksmith is in a way the birthing man.Footnote 121 We can also see in the fusion of the Ergene Qūn's iron mine by means of the seventy bellows, and of which the blacksmith is the great organiser, both a magical operation which occupies the entire community in the collection of fuels,Footnote 122 and thus serves to symbolically weld it, and a ritual for the dedication of the group called Mongol, whose emergence outside the mountains marks the birth. It is clearly this creative role that, through the figure of the blacksmith, is attributed to Chinggis Khan, whose conquests give birth to a new society.

The founding event: Baljuna

The legend of Chinggis Khan thus constructed tells the mythical origin of the new community that is the Mongol Empire. Following Painter's intuition, it can be said that it is in fact based on a proven event of the Mongol history: the battle of Qalaqaljid Elet and the Baljuna Covenant. In my opinion it is even possible to discern the transition from this historical event to legend.

In his long study on Baljuna, Francis W. Cleaves established less the reality of the facts that took place there than the indisputable importance that the event had for the generations that followed the foundation of the Mongol Empire.Footnote 123 Though this does not necessarily appear at first glance: the Shengwu Qingzheng Lu and the first chapter of the Yuanshi, which deals with the reign of Chinggis Khan, are relatively simple in their descriptions, and finally rather laconic as to what happened then.Footnote 124 And if the Secret History describes the battle of Qalaqaljid Elet, the Baljuna Covenant is absent of it. Other sources, however, provide a somewhat different picture.Footnote 125 The biography of Ja‘far Khwāja included in the Yuanshi reads as follows:

Taizu [Chinggis Khan] had a rift with Wang Han [Ong Qan] of the Kelie [Kereyids]. One evening Wang Han came, moving his troops surreptitiously. Taken by surprise and being unprepared, the army [of the Mongols] was completely routed. Taizu straightway withdrew and fled. Those who went with him were only nineteen, and Jabaer [Ja‘far] was included. When they reached the Banzhuni [Baljuni] River, their provisions were entirely exhausted and, since the place was desolate and remote, there was no way to obtain food. It happened that a wild horse came northward. The prince Haja'er [Qajar, ie Jochi Qasar] shot it and killed it. Thereupon they cut the hide open so it mays serve as a cauldron, and they produced fire by means of stones. They drew water of the River, boiled it, and they consume them.Footnote 126 Taizu raised his hands and looking up at Heaven swore, saying: “If I am able to achieve the Great Work [i.e. to found the empire], I shall share with you men the sweet and the bitter. If I break this word, may I become as the water of the River.” Among officiers and soldiers there was none who was not moved to tears.Footnote 127

太祖與克烈汪罕有隙。一夕,汪罕潛兵來,倉卒不為備,眾軍大潰。太祖遽引去,從行者僅十九人,札八兒與焉。至班朱尼河,餱糧俱盡,荒遠無所得食。會一野馬北來,諸王哈札兒射之,殪。遂刳革為釜,出火于石,汲河水煑而啖之。太祖舉手仰天而誓曰:「使我克定大業,當與諸人同甘苦,苟渝此言,有如河水。」將士莫不感泣。

Rashīd ad-Dīn, who differs here from his common source with the Shengwu Qingzheng Lu, also tells :

This battle is well known and quite famous among the Mongols and they still tell of it as the Battle of Qalāljīt Elet. The ground is on the frontier of Khitayan territory, and because of their [the Kereyids’] multitude, Chinggīz Khān was unable to stay there and he retreated. When he withdrew, most of the army deserted him. He went to Baljuna, a place where there were a few small springs, insufficient for them and their animals. Therefore they squeezed water from the mud to drink. After that they emerged from there and went to places that will be mentioned. The group that was with Chinggīz Khān at that time in Baljuna were few, and they are known as the Baljunatu, meaning that they were there with him and did not desert him. Their rights were therefore firm, and they held precedence over the others. When they emerged from there, some of the army and groups regrouped around him.Footnote 128

و آن جنگ پیش اقوم مغول معروف و مشهور است و هنوز به حکایات باز گویند که جنگ قلالجیت الت . و آن زمین به حدود ولایت ختای است، و به سبب کثرت ایشان چنگگیز خان نتوانست ایستادن، [باز گشت ]. و چون مراجعت نمود، اکثر لشکر از او جدا شدند و او به جانب بالجونه رفت . و آن موضعی بود که در آن چند چشمۀ آب اندک بوده، و جهت ایشان و چهارپایان کفاف نه ؛ بدان سبب آب از گل می فشرده اند و می جورده . و بعد از آن از آنجا بیرون آمده و به مواضعی که ذکر آن می آید رفته . و جماعتی که در آن وقت با چینگگیز خان بهم در بالجونه بوده اند اندک بودند، و ایشان را بالجونتو گویند، یعنی در آن مقام با او بوده اند و از او جدا نشده، و حقوق ثابت دارند و از دیگران ممتاز باشند . و چون از آنجا بیرون آمده، باز بعضی از لشکر و اقوم بر او جمع شده اند […].

There are several points of the legend, including a military defeat, forcing a retreat with a small group of survivors to a remote place and in each case crossed by a watercourse, which had not been mentioned until then,Footnote 129 and where the group is restoring its forces. Rashīd ad-Dīn goes as far as to mention the “emergence” (bīrūn āmada بیرون آمده ) outside the place and the growth of the group gathered around Chinggis Khan. Similarly, the providential arrival of a wild horse that allows the group not to starve to death is most certainly not a historical element: it is in fact the motif of the sustantation of the hungry group already found in Plano Carpini – who tells that during the return from a campaign the Mongols, as they ran out of food, were able to survive by discovering by chance the entrails of an animal which they ateFootnote 130 – but which is also present in both versions of the Türk myth, in the Kimek myth, as well as in Ibn ad-Dawādārī.Footnote 131 The borrowing in these two passages of elements of the mythical structure testifies, in my opinion, to the process of transformation of the events of Qalaqaljid Elet and Baljuna into the founding moment of the Mongol Empire.

Like Rashīd ad-Dīn, in the passage just mentioned above, Juvaynī and the Yuanshi tell us that the names of those who participated in the Baljuna Covenant were listed, and that they enjoyed a special status.Footnote 132 Rashīd ad-Dīn does write that in his time this confrontation against the Ong Khan “is well known and quite famous among the Mongols and they still tell of it as the Battle of Qalāljīt Elet”. But there are also a number of indications that this episode was considered a posteriori as being at the very origin of the Chinggisid imperial construction. We can see, for example in the biography of Ja‘far Khwāja that this is the moment when Chinggis Khan conceived his “Great Work”. In the second biography of Sübe'edei of Yuanshi, it is said that it is in Baljuna that Chinggis Khan establishes “his rising capital”, xing du 興都.Footnote 133 In an epitaph written by Xu Youren 許有壬 (1287–1364) the event is called “[The most marvelous] achievement in the world! The founding of the empire thereby began” 代工開天伊始.Footnote 134 We can also mention a poem by Ke Jiusi 柯九思 (m. 1365) evoking Qubilai, who had referred himself to the Baljuna episode,Footnote 135 and in which we read:

The Heihe [“Black River”, i.e. the Baljuna] – the limitless, continuous desert – Shizu [Qubilai] was deeply mindful of the difficulties [there experienced] in the founding of the empire.Footnote 136

黑河萬里連沙漠,世祖深思創業難。

Perceived as a founding event, the Baljuna Covenant and the vicissitudes surrounding it thus took the form of the founding myth, to become in their turn the legend of the symbolic origins of the Mongol Empire. The battle against the Ong Khan, of undecided engagement or half victory, has become a clear defeat, and it is not insignificant that the only sources telling us that the Mongols were defeated at Qalaqaljid Elet are precisely those that borrow other elements from the mythical structure. The location of the battlefield on the border with northern China, according to Rashīd ad-Dīn, probably helped to transform the clash into a campaign against the Kitai and their emperor, a more unifying enemy, including for the Kereyid themselves who were now an integral part of the empire. The swamps of the Baljuna lake, which probably evoked the mythological motif of the marsh already present in the Türk myth, have become a refuge similar to the Ergene Qūn. And the story of the empire's origins blended with the narrative of the origins at all.

Proof that Painter was not mistaken in his hypothesis, although it seems he had thought it was only a distortion in Plano Carpini's account, and that this legend of Chinggis Khan's beginnings and the origins of the Mongol Empire indeed reflects the episode of Baljuna, is provided by a passage from a funeral inscription written by Yu Ji 虞集 (1272–1348):

As Emperor Taizu began to rise like a Dragon, all the people in his army were subjected to a violent attack. At nightfall, with seven of his men, he arrived at the cliff of a great rock, he loosened his belt and passed it around his neck as a ritual, and he prayed: “As Heaven has created me, when I am faced with the risk of perishing,Footnote 137 there are always signs that He is helping me.” Immediately nineteen men rushed forward to him and asked to put their forces at his service. It was the family of Niegutai [Negüdai]. The people of Niegutai were divided into four lines: the Bo'erzhuwu [*Borju'ud?], the Ezhiwu [*Eji'ud?], the Tuohuolawu [Toqora'ud], and the Saha'ertu [*Saqartud?]. Jingzhou is thus a descendant of the Bo'erzhuwu.Footnote 138

太祖皇帝龍興初,一旅之眾嘗遇侵暴。夜與從者七人,至于大石之崖,解束帶加諸領以為禮,而禱曰:「天生我面曼之命,必有來助之兆焉。」俄有十九人者,鼓行以前,請自效,是為捏古台氏。捏古台之人,其族四:曰播而祝吾,曰厄知吾,曰脱和剌吾,曰撒哈兒秃。靖州,則播而祝吾之裔也。

The seven survivors of Plano Carpini are mingled here with the nineteen followers from the biography of Ja‘far Khwāja in one and the same legend.Footnote 139

Conclusion

It has so far been difficult to explain these passages that I have tried to study here: Plano Carpini's account referred to an unidentifiable military campaign, Jūzjānī's must have been a distortion of the myth of the Ergene Qūn. In my opinion, there are two main reasons for this. The first is the erroneous conception that has prevailed until now of what the myth of origin among nomads is, namely that it tells the story of the origin of a people, that it is the story of an ethnogenesis. Compared to the myth of the wolf and the cave, or the myth of the Ergene Qūn, which were supposed to tell the ethnogenesis of the Türk people or of the Mongol people, the story told in the Orkhon inscriptions or the legend of Chinggis Khan seemed different in their very nature. However, the myth does not tell the story of the origin of a people but of a political community. In this respect, the legendary stories around Chinggis Khan are completely equivalent to the myth of the Ergene Qūn. I will come back to this point in a forthcoming study.Footnote 140

Our difficulty in understanding these various stories then came, I think, from the very fact that neither Plano Carpini, nor Jūzjānī nor Hayton, nor any other Latin ambassador, Arab traveller or intellectual from Mamluk Egypt who heard and transcribed that Chinggis Khan had been a blacksmith, for example, must have been fully aware of the meaning of these traditions, which they transmitted to us nolens volens for what they were not: a detailed description of the facts as they had taken place, that is history. Being foreign to their context of enunciation, these authors could not grasp the full meaning of these narratives, which researchers were soon to qualify as apocrypha, to think of them as the result of popular etymologies and games of assonance, confusions and successive distortions. In other words, to consider them either false or unfounded. In fact, beyond the necessary contingencies of oral transmission, the statements reported by our various sources were accurate; it is their context that we lack to give them a sense.

We can try, and this is what I have sought to do here, to reconstruct this context by cross-checking the bits of information we have at our disposal: this context is that of the longue durée that links the entire Eurasian steppe from the Türks, at least, to the Mongols. It is made up of a “savoir partagé”,Footnote 141 composed of myths whose filiation with each other is obvious, a sacred repertoire, traditions and rituals common to periods and socio-political groups, allowing the expression of an alternative narrative to the historical one, which operates by allusions and understatements well understood by its recipients but unintelligible for an outsider.Footnote 142

This narrative has a political purpose and an immediate efficacy, which makes me think that it is not a popular tradition, but rather a construction coming from the high spheres of the Mongol Empire. It aims to give an understandable meaning to the Mongol conquest initiated by Chinggis Khan not only to the Mongols themselves, but also to all the nomadic subjects of the empire, and thus, by drawing on a common repertoire, to unify them within a pan-nomadic empire, in an effort parallel to that developed by traditional historiography to bring the Turks and the Mongols back to a common root.Footnote 143 Hence the coexistence of such a narrative of the symbolic origins of the Mongol Empire alongside an official history – since, from the Secret History to the Yuanshi, via the Persian historiography (with the notable exception of Jūzjānī, who wrote from his refuge in India), the vast majority of the sources on which we rely to reconstruct the birth of the Mongol Empire are to varying degrees the work of court historians. The latter was for an elite, or even only for the imperial clan. The former was addressed to all the nomads of the empire in the colourful language of their beliefs, of their mental universe, which they had shared for centuries.