INTRODUCTION

The bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) is a species that is widespread all over the world, inhabiting a wide variety of habitats, from coastal zones to offshore areas (Wells & Scott, Reference Wells, Scott, Ridgway and Harrison1999; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Wells and Eide2000). In the ACCOBAMS (Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and contiguous Atlantic area) region, only the coastal form is present (Notarbartolo di Sciara, Reference Notarbartolo di Sciara2002). Tursiops truncatus is protected by laws and international conventions for the conservation of species and habitats (Azzolin, Reference Azzolin2008).

The bottlenose dolphin has recently been classified as ‘Vulnerable’ (VU A2cde) in the Mediterranean (Bearzi & Fortuna, Reference Bearzi, Fortuna, Reeves and Notarbartolo di Sciara2006; Reeves & Notarbartolo Di Sciara, Reference Reeves and Notarbartolo Di Sciara2006). This species has to deal with many problems including disease caused by pollution (Borrel et al., Reference Borrel, Cantos, Pastor and Aguilar2001; Wafo et al., Reference Wafo, Sarrazin, Diana, Dhermain, Schembri, Lagadec, Pecchia and Rebouillon2005), loss of habitat (Aguilar et al., Reference Aguilar, Forcada, Borrell, Silvani, Grau, Gazo, Calzada, Pastor, Badosa, Arderiu and Samaranch1994; Simmonds & Nunny, Reference Simmonds, Nunny and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002), fishery resources degradation (Bearzi, Reference Bearzi and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002), interaction with commercial fisheries (Bearzi, Reference Bearzi and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002) and physical and acoustic disturbance (Roussel, Reference Roussel and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002) caused by human activities, particularly increased boat traffic in areas with high levels of marine tourism.

The effects of sea traffic on animals can be described by considering both short- and/or long-term reactions. Short-term reactions are indicated by changes in behaviour and spatial movement away from the area of interaction (Nowacek et al., Reference Nowacek, Wells and Solow2001; Lusseau, Reference Lusseau2003b). Dolphin response has been suggested as being related to noise (Bejder et al., Reference Bejder, Dawson and Harraway1999) or a reaction to visual impact, or a combination of both (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Greene, Malme and Thomson1995; David, Reference David and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002). The presence of a concentrated food source, represented by fishing boats during their activity, can also lead the animals to exhibit changes in behaviour.

In the Mediterranean Sea, only a few studies have focused on behavioural changes related to boat traffic (David, Reference David and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002), with the exception of Underhill (Reference Underhill2006) who reported modifications in diving pattern of Tursiops truncatus in Sardinian waters.

In the Sicily Strait, and particularly on the African platform on which Lampedusa lies, Tursiops truncatus is one of the most common species (Notarbartolo di Sciara & Demma, Reference Notarbartolo di Sciara and Demma1994). Lampedusa, which is part of the Pelagie Archipelago, has one of the highest sighting frequencies for the species in the Mediterranean Sea. During the period 2003–2006 the mean sighting frequency (sea-based) was 0.72 sightings per hour (standard deviation (SD): 0.82) and the encounter rate was 0.05 sightings per km (SD: 0.03) (Azzolin et al., Reference Azzolin, Celoni, Galante, Giacoma and La Manna2007). Almost all other estimates of mean sighting frequency in the Mediterranean are lower: 0.43 sightings per hour in the North Adriatic Sea (Bearzi et al., Reference Bearzi, Di Sciara and Politi1997), 0.06 sightings per hour in the Ligurian Sea (Gnone et al., Reference Gnone, Caltavuturo, Ferrando and Fossa2003) and an encounter rate between 0.004 and 0.1 in different localities in the Alboran area (Canãdas et al., Reference Canãdas, Sagarminaga, De Stephanis, Urquiola and Hammond2005). The locality with a mean encounter rate of 0.1 is also situated near the coasts of an island (Alboran Island).

In Lampedusa the main human activities are fishing and tourism. Tourist pressure has dramatically increased over the last 10 years, leading to a high proliferation of boat traffic. From 2000 to 2006, charter flights increased from 44 to 544 per year, with tourist numbers rising from 6496 to 50,387 per year (official data from the Sicilian Region Tourism Sector, Communication and Transportation: http://www.regione.sicilia.it/turismo/trasporti/). Moreover, according to La Manna et al. (Reference La Manna, Clò, Papale and Sarà2010) for at least three months a year (from July to September) boat traffic is intensive and regular.

In 2003, a Marine Protected Area (MPA) was created to manage the natural resources of the Pelagie Archipelago and to improve the development of sustainable activities, such as dolphin-watching. If conducted responsibly with the support and awareness of the local population, dolphin-watching may represent a sustainable way of improving the local economy (Beaubrun, Reference Beaubrun and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002). In order to investigate the effects of boat traffic on Mediterranean bottlenose dolphins and provide guidelines for managing tourist activities inside the newly created MPA and the surrounding waters, a research project was carried out in Lampedusa waters under the Life Project ‘Del.ta.’ (NAT/IT/000163) to describe: (i) the dolphins' reaction in relation to vessel distance (within and over 200 m) and boat type; and (ii) changes in sub-sequences or frequencies of behaviour in relation to boat absence, presence within 200 m from the dolphins, and after departure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

During the summer of 2006, land-based surveys were carried out at Lampedusa, one of the Islands of the Pelagie Archipelago (Figure 1), located at latitude 35°30′N and longitude 12°36'E, over the continental African platform.

Fig. 1. Survey localities selected in Lampedusa.

Interactions between dolphins and boats were studied from land, to avoid the dolphins' behaviour being affected by a research vessel (David, Reference David and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002). Surveys were conducted from the following 6 locations: Cala Francese (south-east 9 m, 70° of sea sector open view); Cala Pulcino (south-west 67 m, 140° of open view); Albero Sole (north-west 133 m, 240° of open view); Punta Taccio Vecchio (north-west 72 m, 150° of open view); Punta Alaimo (north-east 50 m, 130° of open view); and Capo Grecale (north-east 52 m, 170° of open view). Tabaccara (south 53 m, 103° of open view) was added in 2008 because of the high number of tourists and dolphin presence in this area (Figure 1).

Data collection

Data collection started on the 1 July and ended on 30 September in 2006 and continued from 24 July to 30 September 2008. Surveys were conducted during standard weather conditions: wind intensity of no more than 3 on the Beaufort scale, sea state of no more than 3 on the Douglas scale, and visibility of 2 km or over.

Two observers conducted surveys concurrently, at set hours in the morning (8:00–11:00) and before sunset (17:00–20:00). Continuous horizon scans were performed, both with the naked eye and using binoculars (7 × 50). During monitoring, data on environmental variables (sea state, wind force and cloud cover) and boat presence were collected every 15 minutes. When dolphins were sighted the observers started ‘focal group sampling’ of selected behaviours (Altmann, Reference Altmann1974; Mann, Reference Mann1999). Data were included in the analysis only when correlation between the two concurrent observers was higher than 95%.

An ethogram of behavioural ‘states’ and ‘events’ was used to describe dolphin behaviour, in accordance with Muller et al. (Reference Muller, Boutiere, Weaver and Candelon1998). Frequency of events and the frequency and duration of each ‘state’ were recorded. The behaviours considered for data collection are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Recorded behaviours during sightings.

‘Catching’ behaviour was only recorded when dolphins were sighted with a fish in their mouth. Since it was not always possible to record the beginning and the end of a dive, we introduced the ‘non-quantified dive’ behaviour.

According to David (Reference David and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002), short-term behavioural reactions to the presence of a vessel can be categorized as positive (animals stop their current activity to approach the boat), negative (animals change their behaviour moving away from the source of disturbance) and neutral (animals continue their surface activity or their route without notable change).

Boats were divided into four categories: fishing boats; sailing boats (wind propelled); powered engine boats; and large vessels (e.g. ferries).

Data analysis

To assess the impact of boat traffic on dolphin behaviour, duration and frequency of state and frequency of events were examined in situations where boats were within 200 m from the animals. The distance of 200 m was chosen in accordance with Liret (Reference Liret2001), who reported that small odontocetes react to boats at a distance of 150–300 m, and with David (Reference David and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002) who studied dolphin–boat interactions in the Mediterranean Sea.

Behavioural occurrence and sighting duration, as a function of the distance between boat and dolphins, were evaluated according to boat type and tested by statistical analyses (Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis and Tukey).

In order to describe behavioural variation when animals were approached the within 200 m by a boat, the sequences of states and events were analysed using Markovian chains. A Markovian chain quantifies the dependence of an event on the previous one (Guttorp, Reference Guttorp1995; Caswell, Reference Caswell2001). The first order chains were analysed to enable a linear analysis of behavioural sequences (Lusseau, Reference Lusseau2003a). A randomization test applied to the frequencies of transitions determined the degree of stereotypy of the sequences performed when boats were absent (pre), during the presence of boats (with boat) and after the boats departed (post). The test enabled the assessment of the likelihood of the observed probability, through thousands of possible recombinations of behavioural sequences into sequences of the same length as those recorded. If the transition between each behaviour was found to occur fewer times than the observed transitions, with a minimum level of 10% (up to 100 of times), the observed transition was assumed to be significantly related and considered to be stereotyped.

RESULTS

In order to describe the variation in behaviour caused by boats approaching dolphins at a short distance (200 m), 204 surveys were carried out, for a total of 559 hours of monitoring and 83 sightings recorded, with a minimum of one and a maximum of 10 observed individuals per school (mean 3.02; SD 1.65).

Table 2 shows the distribution of monitoring effort during the 3 months of surveys of 2006 and 2008.

Table 2. Distribution of monitoring effort during summer 2006 and 2008.

Considering all scans performed every 15 minutes, boats were detected a total of 17,626 times: 61.25% of recordings were powered engine boats, 35.72% were fishing boats and only 3.03% consisted of sailing boats. During both years the ratio of the presence of powered engine vessels versus fishing boats is nearly four times in July, decreasing to nearly three in August and just below one in September.

In 2006, the presence of sailing and powered engine vessels did not differ between the months (Kruskal–Wallis test N = 18, df = 2, χ2 = 2.694, P = 0.260, and N = 18, df = 2, χ2 = 3.509, P = 0.173 respectively), whereas in 2008 the number of powered engine boats recorded in September was significantly lower (Kruskal–Wallis test N = 21, df = 2, χ2 = 10.805, P = 0.005).

Fishing boat presence increased during the summer: a significantly higher occurrence of fishing boats was recorded in September 2006 (Kruskal–Wallis test, N = 18, df = 2, χ2 = 9.906 P = 0.007) and in both August and September 2008 (Kruskal–Wallis test, N = 21, df = 2, χ2 = 11.896, P = 0.003).

To assess the mean sighting frequency for the season, the data recorded in July 2006 were only included in the dataset from 25 July, because one of the observers working during this month underestimated dolphin presence (due to a ‘perception bias’: Aragones et al., Reference Aragones, Jefferson and Marsh1997; Giacoma et al., unpublished observations). From 25 July to 30 September 2006 the mean sighting frequency was 0.29.

While surveying for dolphins, 117 behavioural sequences made up of 22 behaviours were recorded during 36.93 hours.

Statistical analysis did not reveal significant differences in sighting frequency between morning and afternoon surveys (2006 Mann–Whitney test N = 65, Z = –0.204, P = 0.84; 2008 Mann–Whitney test N = 111, Z = –0.243, P = 0.80) (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison between morning and afternoon sightings.

sight., sightings.

Mean sighting duration was significantly shorter in 2008 (25.87 minutes in 2006 and 13.94 minutes in 2008) (Mann–Whitney test N = 117, Z = –2.820, P = 0.005) and increased significantly between July, August and September 2008 (8.8 minutes; 12.12 minutes; 18.17 minutes) (Kruskal–Wallis test N = 69, df = 2, χ2 = 6.582, P = 0.037).

Dolphin presence and behaviour were analysed in relation to boat traffic, evaluating the following aspects of interaction:

(a) dolphins' reaction to vessel presence/absence within 200 m according to boat type;

(b) changes in behaviour frequency in relation to pre-boat interaction, boat presence within 200 m and post-boat departure; and

(c) variation of behavioural sub-sequences in relation to pre-boat interaction, boat presence within 200 m and post-boat departure.

We assessed whether there would have been any differences in the dolphins due to daily variations in habitat use and found that the dolphins did not exhibit any significant differences in behaviour throughout the day in the absence of boats (Mann–Whitney test N = 66; normal swim: Z = 0.268, P = 0.789; fast swim: Z = –0.085, P = 0.932; long dive: Z = 0.263, P = 0.792; short dive: Z = 1.795, P = 0.073; aerial behaviour: Z = –0.858, P = 0.391; surface finning: Z = 0.971, P = 0.332; change direction: Z = –0.429, P = 0.668; non-quantified dive: Z = 0.769, P = 0.442; resting: Z = 1.660, P = 0.097; milling: Z = –0.198, P = 0.843)

Dolphins' reaction to vessel presence/absence within 200 m according to boat type

The mean sighting time of 12 minutes in the presence of boats was significantly lower than the 24.6 minutes recorded in their absence (Mann–Whitney test N = 104; Z = –2.741; P = 0.006).

When boats moved very fast (minimum of 20 knots) towards the sighted dolphins (N = 10), without changing their speed and direction, the animals interrupted their activities in 100% of cases, irrespective of the type of approaching boat. In the presence of these fast boats dolphins either moved away horizontally, with ‘departing swim’ behaviour (30% alone and 10% with leaps), or vertically with ‘non-quantified dive’ behaviour (30% alone and 10% with leaps) or they disappeared (30%).

Sailing boats did not have any contact with the animals within 200 m and beyond this distance interactions were always neutral. In the presence of any other type of boat within 200 m, the interactions exhibited by dolphins were negative in 69.81% of cases, neutral in 16.98% and positive in 13.21%.

We separately analysed reactions towards fishing and powered engine boats, the two categories that interact most frequently with bottlenose dolphins (Table 4). Most of the dolphins' negative reactions to both powered engine boats (67%) and fishing (64%) occurred when the boat was within 200 m. Differences in the occurrences of the dolphins' positive, neutral or negative reactions in response to powered engine and fishing boats within 200 m was close to significant level (χ2-test df = 2; χ2 = 5.74; 0.05 < P < 0.1) (Figure 2). Interactions over 200 m were predominantly negative for powered engine boats and neutral for fishing boats (χ2-test df = 2; χ2 = 16.14; P < 0.001) (Figure 3). A notable behavioural difference between the two boat types was the more frequent positive reaction towards fishing boats. The positive reaction occurred in 9.4% of cases when the boats were within 200 m and 12.4% when over 200 m away.

Fig. 2. Interaction in relation to different types of boats approaching within 200 m.

Fig. 3. Interaction in relation to different types of boats approaching over 200 m away.

Table 4. Occurrence of positive, negative or neutral interactions with fishing and powered engine boats within and over 200 m.

Changes in behaviour frequency in relation to pre-boat interaction, boat presence within 200 m and post-boat departure

The dolphins showed clear differences in frequency of behaviour when boats were within 200 m: the animals did not exhibit ‘surface finning’ and ‘resting’ behaviour (Figures 4 & 5). Duration of ‘normal swim’ behaviour was significantly shorter (Tukey post-hoc test P < 0.05) and the highest mean frequency was recorded for ‘non-quantified dive’ (Tukey post-hoc test P < 0.05) and ‘change of direction’ behaviour (Tukey post-hoc test P > 0.05, not significant (ns)). The sum of all the ‘aerial behaviours’ (E/F/G/I/L/Q/S/T/U/V/Z) increased in the presence of the boats and reached the highest frequency after boat departure (Tukey post-hoc test P > 0.05, ns). Milling was also more frequent in the presence of boats within 200 m and after their departure, but not statistically significant (Tukey post-hoc test P > 0.05 ns). The decrease in ‘short dive’ was also not significant (Tukey post-hoc test P > 0.05, ns) (Figures 4 & 5).

Fig. 4. Mean frequencies recorded before boat approach, during boat presence and after boat departure.

Fig. 5. Mean frequencies recorded before boat approach, during boat presence and after boat departure.

Variation of behavioural sub-sequences in relation to pre-boat interaction, boat presence within 200 m and post-boat departure

Mean duration of the 70 sequences recorded before the boat came within 200 m was 21.62 minutes (SD = 20.90); 12.00 minutes (SD = 14.41) for the 32 sequences with boats; and 20.04 minutes (SD = 17.38) for the 15 sequences post-boat departure.

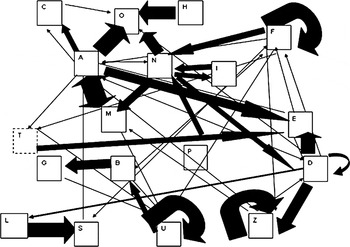

Dolphin behaviour showed a high degree of stereotypy. The highest number of different stereotyped sub-sequences of behaviours was exhibited in the absence of boats (Figures 6 & 8). Common sub-sequences made up of behaviours related to feeding activity, were exhibited by animals in the absence of boats: ANM (‘normal swim’, ‘non-quantified dive’, ‘change of direction’ and ‘normal swim’ again) and BNM (‘fast swim’, ‘non-quantified dive’, ‘change of direction’ and ‘fast swim’ again). In the presence of boats (Figure 7) the ANM sequence often continued with a ‘departing swim’ (R) or was interrupted, ‘end of sighting’ (O). Transitions to ‘end of sighting’ (O), were also frequent after boat departure. Another frequent transition consisted of the ANM continuing with H (‘surface finning’) before ‘end of sighting’ (O) in the pre-boat period. The transition to ‘surface finning’ did not take place during boat presence, and only part of the sub-sequence (the transition HO) was restored after boat departure.

Fig. 6. Markovian chain process of behaviour exhibited before the boats approach (pre). Observed transitions are denoted by arrows linking behaviours, represented by their letter code. Arrow sizes indicate transitions, identified by means of a randomization test, considered to be stereotyped rather than random: the thicker the arrow the less random the observed sequence.

Fig. 7. Markovian chain process of behaviour exhibited when boats were within 200 m. Observed transitions are denoted by arrows linking behaviours, represented by their letter code. Arrow sizes indicate transitions, identified by means of a randomization test, considered to be stereotyped rather than random: the thicker the arrow the less random the observed sequence.

Fig. 8. Markovian chain process of behaviour exhibited after boat departure. Observed transitions are denoted by arrows linking behaviours, represented by their letter code. Arrow sizes indicate transitions, identified by means of a randomization test, considered to be stereotyped rather than random: the thicker the arrow the less random the observed sequence.

In the presence of a boat, the BNM sub-sequence (‘fast swim’, ‘non-quantified dive’, ‘change of direction’) was also often interrupted by ‘departing swim’ (R) and decreased further when the boat departed.

Furthermore, the probability of a ‘long dive’ (C) being followed by another ‘long dive’ was disrupted by boat presence.

Before the boats arrival ‘short dive’ (D) had a high probability of being followed by another ‘short dive’ or by a ‘breach’ (E) (a social behaviour). When boats were within 200 m the probability of the ‘short dive’ being followed by repetition of a ‘spy hop’ (Z), considered to be information-gathering behaviour (Martinez & Klinghammer, Reference Martinez and Klinghammer1978) increased. When the boats left, ‘short dive’ continued to be interrupted by ‘spy hop’, but the probability of exhibiting a breach (E) remained high.

A highly repetitive aerial behaviour (‘leap’—F), associated with the sub-sequence of ‘normal swim’–‘non-quantified dive’–‘change of direction’ (ANM), decreased during boat presence and was re-established after departure. Another highly repetitive aerial behaviour (the ‘vertical leap’—S) decreased in the presence of boats.

After boats departed the probability of ‘vertical leap’ being associated with ‘chin slap’ (L) increased. Moreover, the sub-sequence starting with ‘lateral breach’ (U) had a very high probability of consisting of a series of ‘lateral breach’, followed by ‘fast swim’ (B) and ‘tail slap’ (G).

DISCUSSION

This study revealed strong short-term reactions from bottlenose dolphins according to the type of boat and the distance between the animals and the boats.

When a group was approached by large vessels that do not modify their speed and direction, such as fast ferries, dolphins left the source of disturbance behind them, as also reported by other authors (Polacheck & Thorpe, Reference Polacheck and Thorpe1990; Evans, Reference Evans1992; Lütkebohle, Reference Lütkebohle1996; Nowacek et al., Reference Nowacek, Wells and Solow2001; Constantine et al., Reference Constantine, Brunton and Dennis2004; Mattson et al., Reference Mattson, Thomas and St Aubin2005; Lemon et al., Reference Lemon, Lynch, Cato and Harcourt2006).

When the two most common boat types, fishing and powered engine boats, were within 200 m they caused avoidance behaviour in 70% of situations. Occasional exceptions consisted of positive interactions with bottom trawling fishing boats followed by dolphins (Celoni et al., Reference Celoni, Azzolin, Galante and Giacoma2009). In the presence of powered engine and fishing boats within 200 m, dolphins reduced their behaviour repertoire and the number of sub-sequences commonly shown in a relaxed, social and feeding context. When boats were within 200 m, resting behaviour was absent and behaviours such as normal swim and long dive were less frequent; on the other hand, the highest frequency of fast swim and change direction occurred in the presence of boats within 200 m. Other authors (David, Reference David and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002; Notarbartolo Di Sciara et al., Reference Notarbartolo di Sciara, Jahoda, Biassoni and Lafortuna1996) have also reported dolphins reacting to disturbances by moving fast, either in a straight line or zigzag. When boats follow them for a long period, navigating directly towards the group and across it, they often disappear. Short-term reactions to boats, in terms of changes in activity, have been documented for bottlenose dolphins of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans (Lütkebohle, Reference Lütkebohle1996; Mattson et al., Reference Mattson, St Aubin and Thomas1999, Reference Mattson, Thomas and St Aubin2005; Nowacek et al., Reference Nowacek, Wells and Solow2001; Lusseau, Reference Lusseau2003a, Reference Lusseaub; Constantine et al., Reference Constantine, Brunton and Dennis2004; Sini et al., Reference Sini, Canning, Stockin and Pierce2005; Lemon et al., Reference Lemon, Lynch, Cato and Harcourt2006). Underhill (Reference Underhill2006) noticed changes in diving patterns and a dominant travelling behaviour in the presence of tourist boats in the Mediterranean region. However, short-term responses to boat traffic are extremely variable and are not maintained over time, varying at both species- and individual-specific level (David, Reference David and Notarbartolo di Sciara2002).

In general, our research showed that dolphins in the presence of boats not only reduced the variety of exhibited behaviours, but also changed and interrupted the usual sub-sequences related to feeding, social context and rest, and increased sub-sequences indicating stress (avoidance and slaps: Frohoff & Dudzinski, Reference Frohoff and Dudzinski2001). Information-gathering and noisy behaviours appeared during boat presence and continued after boat departure.

With regard to feeding related behaviours, ‘catching’ frequency was undoubtedly underestimated by our survey because it was only noted when dolphins were spotted with a fish in their mouth, therefore we cannot conclude, as Underhill (Reference Underhill2006) did, that there is a reduction in feeding in the presence of boats. Nevertheless, behaviours typical of a feeding context such as normal swim, changing in direction (Bailey & Thompson, Reference Bailey and Thompson2006, Arcangeli & Crosti, 2009) and non-quantified dive are shown in the ANM and BNM sub-sequences.

The circularity of the sub-sequences characterizing dolphin behaviour in the absence of boats, like ‘normal swim–deep dive–change direction–normal swim’, was disrupted by boats approaching the dolphins within 200 m. This is consistent with the effect described in Atlantic areas where Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Solangi and Kuczaj2008) noticed a decrease in time spent foraging immediately following the presence of a high-speed personal watercraft.

The effect of the boats was also evident after their departure: increasing trend in the frequency of ‘aerial behaviours’ and ‘milling behaviour’ and the decreasing trend in ‘short dive’ behaviour persisted, while behaviours related to moving, such as normal swim and non-quantified dive returned to pre-boat levels. Animals rarely restarted their previous activity once a boat had left.

The mean sighting duration decreased, in the presence of boats within 200 m, from 24.6 to 12.0 minutes. In 2008, the lower mean sighting duration of 13–14 minutes may have been caused by the higher presence of powered engine boats (powered engine boats frequency = 76.71 versus 50.90 in 2006). During 2008, the maximum duration of sightings was observed in September when the presence of powered engine boats was lower. These data therefore appear to indicate the possibility that, in Lampedusa waters, bottlenose dolphins do not become habituated to boats and point to a potential negative long-term impact of the recent increase in boat traffic.

Last year monitoring of the Lampedusa area showed that many bottlenose dolphins are emaciated (La Manna G., personal observation), however, the causal relationship between the recorded behavioural changes found by this research and the long-term consequences will need further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study indicate that sailing boats rarely interacted with dolphins and when they were in proximity they did not cause any negative impacts. The reactions to large vessels that do not modify their speed could not be analysed in detail because of the low number of recorded sightings, but fast boats had a big impact on the bottlenose dolphins' behaviour. However, these fast boats were the less frequent type of boats occurring within 2 km from the Lampedusa coasts: as a consequence their overall impact on the population may be low. Fishing boats can elicit positive behaviour related to feeding in a limited group of dolphins, but, in general, both fishing and powered engine boats negatively affected bottlenose dolphins when they approached within 200 m. No evidence of dolphin habituation to boat traffic documented in other areas of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans were found (Acevedo, Reference Acevedo1991). Costal tourism is continuously changing in the Mediterranean Sea over the course of the year and is highly concentrated in space and time. As shown by Srebreva et al. (Reference Srebreva, Colmenares, Fortuna and Canadas2009) this fact can affect dolphins differently. Still, regarding these results, to avoid that reactions analysed during this study will become a potential negative effect for animals, a possibility may be minimizing disturbance and implementing ACCOBAMS guidelines as suggested by the Action Plan for the Pelagie (Azzolin et al., Reference Azzolin, Celoni, Galante, Giacoma and La Manna2007). The most applicable rules are: (i) dolphin watching must be conducted from a distance of at least 200 m; (ii) the number of boats and the most frequent routes together with dolphins' behaviour should be monitored regularly; and (iii) public awareness raising programmes should be implemented during seasonal peaks in tourist presence. The regulations for boats, proposed in the Action Plan (Azzolin et al., Reference Azzolin, Celoni, Galante, Giacoma and La Manna2007), should also be distributed to the public and observed by vessel operators.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The LIFE project ‘Del.Ta.’ (NAT/IT/000163) was financed by the European Commission. The authors would like to thank the Director of the Marine Protected Area of the Pelagie Islands Giuseppe Sorrentino for his cooperation, all the Centro Turistico Studentesco (CTS) Environment staff for their support and cooperation during the project (particularly: Simona Clò, Irene Galante and Gabriella La Manna); Sergio Castellano for his statistical support; Mauro Miceli for the collaboration in the 2008 data analysis; Andrea Summa, Stefania Milazzo, Marco Regoli and all the other CTS volunteers who participated in the fieldwork. The authors also thank Marc Lammers, Dominic Currie and an anonymous referee for their constructive criticism that improved the paper.