Introduction

The family Flabelligeridae de Saint-Joseph, Reference de Saint-Joseph1894, consisting of 25 genera and about 130 species, is characterized by unique morphological features compared with other polychaete taxa: the chaetae are wider and longer in relation to the size of the body, the nephridia are found as a single paired organ, the gonads are permanent and in many genera they converge in one or two gonopodial papillae located in the anterior chaetigers; moreover, the species of the genera Trophoniella Hartman, Reference Hartman1959, Piromis Kinberg, Reference Kinberg1867 and Pycnoderma Grube, Reference Grube1877 have a very thick cuticle referred to as a tunic (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo, de León-González, Bastida-Zavala, Carrera-Parra, García-Garza, Salazar-Vallejo, Solís-Weiss and Tovar-Hernández2021). Flabelligerid worms are also characterized by the presence of the cephalic cage and by a fusiform to anteriorly truncate body; their tunic is covered by papillae that are often heavily encrusted with sediment (Fauchald, Reference Fauchald1977; Hutchings, Reference Hutchings, Beesley, Ross and Glasby2000; Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo, Purschke, Böggemann and Westheide2019). Although this family is characterized by unique features, its biology and its physiology have been little investigated; for instance, the anterior extremity of these species is retractable (prostomium, peristomium and the first one/two segments) and rarely exposed (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012, Reference Salazar-Vallejo, de León-González, Bastida-Zavala, Carrera-Parra, García-Garza, Salazar-Vallejo, Solís-Weiss and Tovar-Hernández2021), preventing a thorough understanding of important morphological traits. Further studies are warranted to clearly define the systematics of this taxon (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2011, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012, Reference Salazar-Vallejo, de León-González, Bastida-Zavala, Carrera-Parra, García-Garza, Salazar-Vallejo, Solís-Weiss and Tovar-Hernández2021; Chaibi et al., Reference Chaibi, Antit, Bouhedi, Meca, Gillet, Azzouna and Martin2019; Worms, 2022).

The family is cosmopolitan, and their members are mostly burrowing worms but knowledge about their ecology is still limited (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo, Purschke, Böggemann and Westheide2019). Flabelligerid polychaetes are considered deposit feeders (Day, Reference Day1967; Fauchald & Jumars, Reference Fauchald and Jumars1979) and several species inhabit hard, muddy or sandy substrates from the intertidal to abyssal depths (Rouse & Pleijel, Reference Rouse and Pleijel2001; Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo, Purschke, Böggemann and Westheide2019).

Along the European coasts, 21 species, belonging to seven genera, were reported: Brada Stimpson, Reference Stimpson1853, Diplocirrus Haase, Reference Haase1915, Flabelligera Sars, Reference Sars1829, Ilyphagus Chamberlin, Reference Chamberlin1919, Pherusa Oken, Reference Oken1807, Piromis Kinberg, Reference Kinberg1867 and Therochaeta Chamberlin, Reference Chamberlin1919 (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Emblow and White2001). In the Italian waters, only six genera and eight species are currently reported (Castelli et al., Reference Castelli, Bianchi, Cantone, Çinar, Gambi, Giangrande, Iraci Sareri, Lanera, Licciano, Musco, Sanfilippo and Simonini2008): Bradabyssa villosa (Rathke, Reference Rathke1843), Diplocirrus glaucus (Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1867), Flabelligera affinis Sars, Reference Sars1829, F. diplochaitus (Otto, Reference Otto1820), Pherusa plumosa (Müller, Reference Müller1776), Piromis eruca (Claparède, Reference Claparède1869), Stylarioides moniliferus Delle Chiaje, Reference Delle Chiaje1841 and Therochaeta flabellata (Sars in Sars, Reference Sars1872).

Within the family Flabelligeridae, the genus Trophoniella Hartman, Reference Hartman1959, revised by Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012), is closely related to genera Piromis Kinberg, Reference Kinberg1867 and Pycnoderma Grube, Reference Grube1877: species belonging to these genera are all characterized by a thick tunic, often covered with sediment grains, their notochaetae are multiarticulated at least in anterior or median chaetigers and possess a projected tongue-shaped branchial membrane with abundant sessile branchial filaments (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012; Chaibi et al., Reference Chaibi, Antit, Bouhedi, Meca, Gillet, Azzouna and Martin2019). The three genera can be discriminated based on the neurochaetae morphology, particularly those associated with posterior chaetigers. The genus Trophoniella includes species that have entire median or posterior neurochaetae with short, anchylosed articles and bifid or bidentate tips. Piromis is characterized by multiarticulate bidentate neurohooks with long- or medium-sized articles in median and posterior chaetigers, whereas Pycnoderma does not show bidentate neurochaetae and its articles are few and well-defined. Moreover, the species belonging in Trophoniella were further classified into two groups based on the start of anchylosed neurohooks on the body (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012); in Group 1, anchylosed neurohooks are present from chaetiger 10, while in Group 2 they start from median or posterior chaetigers. Within the two groups, instead, the species differ mainly on the characteristics of the sediment cover (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012). The genus Trophoniella is also characterized by (i) clavate to tapering body covered by papillae, (ii) the presence of long parapodial papillae often arranged in dorsal longitudinal rows and (iii) a well-developed cephalic cage (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo, de León-González, Bastida-Zavala, Carrera-Parra, García-Garza, Salazar-Vallejo, Solís-Weiss and Tovar-Hernández2021).

Currently, Trophoniella comprises 29 species, five of which were reported for European waters: T. incerta (Augener, Reference Augener1918), T. fernandensis (Augener, Reference Augener1918), T. enigmatica Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012, T. fauveli Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012 and T. radesiensis (Chaibi et al., Reference Chaibi, Antit, Bouhedi, Meca, Gillet, Azzouna and Martin2019) which was recently described from Tunisian waters (Chaibi et al., Reference Chaibi, Antit, Bouhedi, Meca, Gillet, Azzouna and Martin2019). To date, no species belonging to the genus Trophoniella were reported in Italian waters. In the present work a new species, Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov., is described from shallow-water Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile 1813 beds off the coast of Civitavecchia (central Tyrrhenian Sea). Some specimens of Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. were found in association with the polychaetes Ophelia roscoffensis Augener, Reference Augener1910, Goniadella bobrezkii (Annenkova, Reference Annenkova1929) and Acromegalomma messapicum (Giangrande & Licciano, Reference Giangrande and Licciano2008) and with the isopod Mesanthura sp.; all these species were recently reported, for the first time in the Northern Tyrrhenian Sea, in the same P. oceanica meadow (Tiralongo et al., Reference Tiralongo, Paladini De Mendoza and Mancini2017; Giangrande et al., Reference Giangrande, Mancini, Tiralongo and Licciano2018; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Tiralongo, Ventura and Bonifazi2019a, Reference Mancini, Tiralongo, Ventura and Bonifazi2019b).

Materials and methods

Sampling

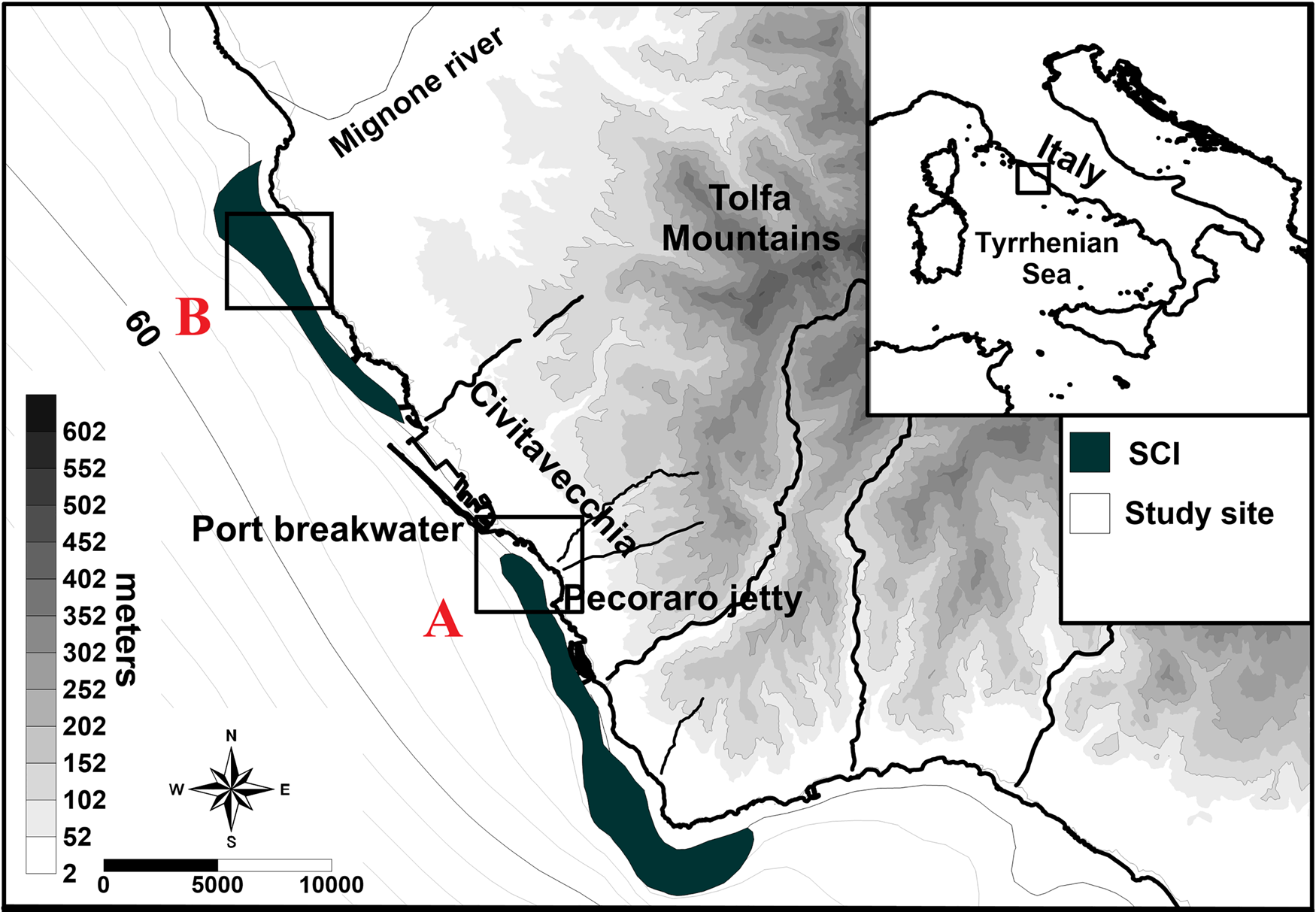

The specimens of Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. were collected in two different areas located off the coast of Civitavecchia (northern Tyrrhenian Sea, Central Mediterranean Sea) (Figure 1): six specimens were collected during scuba surveys performed in 2015 and 2016, in sandy bottoms, located at a depth of about 7 m on a Posidonia oceanica bed (42.0844°N 11.7990°E) (Figure 1A); eight specimens were collected by scuba surveys in July 2019 in sandy pools, located at a depth of about 5 m, on a P. oceanica bed covered by Caulerpa cylindracea Sonder, Reference Sonder1845 (42.1476°N 11.7423°E) (Figure 1B). All samples were collected by corers. Following Gambi et al. (Reference Gambi, Conti and Bremec1998) and Buia et al. (Reference Buia, Gambi and Dappiano2003), each PVC tube corer was 10 cm in diameter and 25 cm in length (surface area = 78.5 cm2) with a 0.4 mm mesh net on top. Corers were plunged into the sediment to a depth of 20 cm. At each sampling site, five replicates were collected and sieved with a mesh size of 0.5 mm. The retained fraction of sediment was subsequently preserved in 4% buffered formalin. In the laboratory, all organisms were sorted and identified to the highest taxonomic level possible (i.e. species) and subsequently preserved in 75% ethanol.

Fig. 1. Map of study area with location of sampling points (SCI: Site of Community Importance ‘Posidonia oceanica meadows’).

Environmental characteristics

The study area extends from the Sant'Agostino to Capo Linaro coastal zones in the northern Tyrrhenian Sea (Italy) (Figure 1). This coastal sector is characterized by the presence of several anthropogenic activities such as the Port of Civitavecchia, one of the most important ports in the Mediterranean Sea due to the intense ship traffic related to commercial and cruise activities. In this coastal area two Sites of Community Importance (SCI) were established, IT6000005 and IT6000006. These SCIs were established specifically for the presence of P. oceanica meadows and are located southerly and northerly of the port, respectively (Figure 1). In the Civitavecchia coastal sector, P. oceanica meadows extend between depths of 0.5–25 m and are located on sandy, rocky or mixed bottoms (Gnisci et al., Reference Gnisci, de Martiis, Belmonte, Micheli, Piermattei, Bonamano and Marcelli2020; Bonamano et al., Reference Bonamano, Piazzolla, Scanu, Mancini, Madonia, Piermattei and Marcelli2021). The structure and localization of the P. oceanica meadows reflect the heterogeneity of the local environments and are influenced by the presence of several coastal human activities. For these reasons their distribution is discontinuous, and the structural and functional descriptors show high variability. The meadows are characterized by high variability of coverage (ranging from 6–98%, coefficient of variation of 72.4%) and show a high fragmentation (Gnisci et al., Reference Gnisci, de Martiis, Belmonte, Micheli, Piermattei, Bonamano and Marcelli2020). Moreover, their density is influenced by the architecture of the meadows, and they show an average of 141.7 ± 62.9 shoots m−2 (Bonamano et al., Reference Bonamano, Paladini de Mendoza, Piermattei, Martellucci, Madonia, Gnisci, Mancini, Fersini, Burgio, Marcelli and Zappala2015, Reference Bonamano, Piazzolla, Scanu, Mancini, Madonia, Piermattei and Marcelli2021; Gnisci et al., Reference Gnisci, de Martiis, Belmonte, Micheli, Piermattei, Bonamano and Marcelli2020).

In sampling site A (Figure 1) the P. oceanica bed extends along 3–18 m water depth and its architecture shows a fragmented seascape. The bed is characterized by the presence of several circular sandy patches (1–6 m in diameter) and mixed rocks. The seabed is covered by live P. oceanica (69%), coarse sand (17%) and small rocks (14%) (de Mendoza et al., Reference de Mendoza, Fontolan, Mancini, Scanu, Scanu, Bonamano and Marcelli2018). The P. oceanica density remains quite constant throughout the year and shows a value of 260 ± 312 shoots m−2 (de Mendoza et al., Reference de Mendoza, Fontolan, Mancini, Scanu, Scanu, Bonamano and Marcelli2018). The sandy patched sediments are composed of gravelly coarse sand and the gravel fraction (19–60%) mainly consists of bioclasts, such as skeletal fragments and shells (de Mendoza et al., Reference de Mendoza, Fontolan, Mancini, Scanu, Scanu, Bonamano and Marcelli2018).

In sampling site B (Figure 1) the P. oceanica bed occurs between 1 m and about 25 m. This area is characterized by infralittoral rocks colonized by some photophilic algae, P. oceanica and Caulerpa cylindracea. In the sampling period, the percentage of surface cover of C. cylindracea was 87.5% (Miccoli et al., Reference Miccoli, Mancini, Boschi, Provenza, Lelli, Tiralongo and Marcelli2021). Also, in this area the P. oceanica meadow is characterized by a high fragmentation, has a coverage of 36% and a shoot density of 281 ± 45.3 shoots m−2 (Gnisci et al., Reference Gnisci, de Martiis, Belmonte, Micheli, Piermattei, Bonamano and Marcelli2020). The bed sediments show a predominantly sandy fraction enriched with a large gravel component and the greater size granules are mostly composed of bioclast by carbonate skeletal and shell fragments (Bonamano et al., Reference Bonamano, Piazzolla, Scanu, Mancini, Madonia, Piermattei and Marcelli2021).

Morphological analysis

Specimens were observed, measured, and photographed using a Nikon DS-Ri2 camera mounted on a Nikon Eclipse e100 microscope and Nikon SMZ18 stereo microscope. The holotype and paratypes were deposited in the Natural History Museum of London.

Results

Systematics

Family FLABELLIGERIDAE de Saint-Joseph, Reference de Saint-Joseph1894

Genus Trophoniella Hartman, Reference Hartman1959

Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. (Figures 2 & 3).

Fig. 2. Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov., holotype, 25 mm (A) lateral view of the whole animal; (B) head; (C) pygidium; (D) distribution of papillae; (E) mamillated papillae.

Fig. 3. Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov., holotype, 25 mm (A) chaetigers 2 and 3; (B) neurochaetae from anterior chaetiger (inset: tips); (C) neurochaetae from a posterior chaetiger; (D) notochaetae, (insets: chaetal basal and distal sections); (E) chaetiger 67, anchylosed hooks; (F) chaetiger 78, anchylosed hooks.

Material examined

All the specimens were collected in two P. oceanica beds located in the coastal area of Civitavecchia, northern Tyrrhenian Sea: six specimens were collected in the SCI IT6000005 (42.1476°N 11.7423°E). Eight specimens were collected in SCI IT6000006 (42.0844°N 11.7990°E).

Holotype (ANEA 2022.794), Tyrrhenian Sea, A1, (42.1476°N 11.7423°E), July 2019, −7 m P. oceanica, coll. Emanuele Mancini.

Paratypes 1 (ANEA 2022.795) Tyrrhenian Sea, A1, (42.1476°N 11.7423°E), July 2019, −7 m P. oceanica, coll. Emanuele Mancini.

Paratypes 2 (ANEA 2022.796) Tyrrhenian Sea, A1, (42.0844°N 11.7990°E), May 2015, −7 m P. oceanica, coll. Emanuele Mancini.

Additional material: 11 individuals from the coastal area of Civitavecchia.

Description

Holotype (ANEA 2022.794) 25 mm long, 4 mm wide, cephalic cage 5 mm long, 80 chaetigers.

Paratype (ANEA 2022.795) 14 mm long, 2 mm wide, cephalic cage 2 mm long, 38 chaetigers.

Paratype (ANEA 2022.796) 8 mm long, 1 mm wide, cephalic cage 0.7 mm long, 20 chaetigers.

Holotype: body yellowish, first 4–5 segments rusty red, chaetae long, abundant, with dense tiny papillae basally covered by fine sediment particles, denser along chaetigers 1–5 (Figure 2A); tunic heavily papillose in the middle and posterior part (Figure 2A). Papillae not arranged in longitudinal rows, irregularly distributed (Figure 2A, D). Papillae mostly small, thin, distally swollen, looking mamillated after sediment load (Figure 2E), abundant all over the body, some papillae longer, clavate in chaetal lobes (Figure 3B, C).

Cephalic hood not exposed (Figure 2B), observed by dissection of paratype. Branchiae cirriform, arising on tongue-like protuberance, in two lateral groups, each with branchial filaments arranged in about 4 longitudinal bands, each band with about 40 filaments. Nephridial lobes not seen.

Cephalic cage chaetae as long as first 5 chaetigers, slightly longer than body width (Figure 2B). Chaetiger 1 involved in cephalic cage (Figure 2B); chaetiger 2 with chaetae longer than following chaetigers, but not contributing to cage; chaetiger 1 with chaetae arranged in short dorsolateral row, neurochaetal lobe almost fused to notochaetal lobe; about 6 notochaetae and 4 neurochaetae per bundle.

Anterior dorsal margin of chaetiger 1 not projecting anteriorly. Chaetigers 1–6 mostly smooth, without long papillae (Figure 3A, B); two tiny papillae in transverse depressions slightly ahead of, and behind notopodial lobes. Chaetigers 1–3 becoming progressively longer, then following segments of similar length, more papillose. Gonopodial lobes not seen.

Parapodia poorly developed (Figures 2B–D & 3A), low rounded dorsal lobes in anterior chaetigers (2–7), reduced posteriorly (Figure 2A, B). Noto- and neuropodia with long postchaetal capitate papillae (Figure 3B, C); notopodia with 6 papillae, longest about 1/3–2/5 as long as notochaetae, neuropodia with 3 papillae. After the 7th chaetiger, postchaetal papillae progressively reduced until no longer present.

Notochaetae arranged in a row, with 3–4 chaetae per bundle until chaetiger 8 (Figure 3A), increasing to 4–5 in median and posterior chaetigers; each notochaeta half as long as body width, as thick as, or thicker than, neurochaetae; all notochaetae multiarticulate capillaries with short articles, terminal article longer (Figure 3D).

Neurochaetae multiarticulate bidentate hooks from chaetiger 2 (Figure 3A), with 3–4 neurohooks in anterior chaetigers (Figure 3B), increasing to 4–5 in posterior chaetigers (Figure 3C). Each neurohook with short articles basally, then fewer articles, becoming progressively shorter, with very long distal articles. Tips of neurohooks curved, bidentate, accessory tooth not surpassing the fang (Figure 3B, C). Anchylosed hooks from chaetiger 65 to body end (Figure 3E, F) arranged in an oblique series, each with four per bundle. Anchylosed hooks with no basal constriction, fang curved, accessory tooth laminar. Posterior end conical; pygidium contracted, anus terminal, without anal cirri (Figure 2C).

Remarks

Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. differs from the other species of this genus and from the other five Mediterranean species mainly by the distribution of the sediment granules on the body and on the first appearance of the anchylosed neurohooks on the body. In T. cucullata sp. nov. the sediment grains are concentrated above in the anterior parts of the body, generating a kind of ‘hood’ on the first 4–5 segments. The chaetigers with the sediment granules are characterized by a different colour pattern compared with the rest of the body: while the chaetigers of the ‘hood’ are reddish, the following ones are pale-yellow and are characterized by a relative scarcity of sediment particles. Such a distribution of the sediment granules on the body has not been observed in any other species belonging to this genus and the other five Mediterranean species show a different pattern of granule distribution: T. incerta and T. fernandensis lack sediments grains on their tunics while T. enigmatica, T. fauveli and T. radesiensis have tunics with sediment grains on both dorsal and ventral surfaces (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012; Chaibi et al., Reference Chaibi, Antit, Bouhedi, Meca, Gillet, Azzouna and Martin2019). A further important diagnostic character of the Trophoniella genus is the mid-body and posterior neurochaetae: anchylosed neurohooks in T. cucullata sp. nov. are only present in the posterior part of the body and they first appear on chaetiger 65. Such a character places T. cucullata sp. nov. in group 2, according to Salazar-Vallejo's classification (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012). Group 2 is composed of 16 other species, but none has anchylosed neurohooks starting at chaetiger 65. With respect to the other five Mediterranean species, anchylosed neurohooks start at chaetiger 6 (T. incerta), 20 (T. radensis) or 30–45 (T. fernandensis, T. enigmatica and T. fauveli).

Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. resembles T. fernandensis because both have papillae looking mamillated after sediment load and they show a similar pattern of distribution of neuro- and notochaetae over the body; however, Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. differs from both Augener's original description of 1918 and from T. fernandensis sensu Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012 based on distribution of papillae and sediment granules on the body and morphology of chaetae.

In T. cucullata sp. nov. the sediment grains are present only on the first 4–5 chaetigers whereas in Augener's specimen they are present all over the body. In T. cucullata sp. nov. the papillae are more abundant in the central and posterior part of the body while in Augener's specimen they are distributed irregularly throughout the body. Augener's specimen has 8 transverse rows of papillae between the parapodia while T. cucullata sp. nov. entirely lacks papillae rows. In T. cucullata sp. nov. the longest clavate papillae are present only in chaetal lobes whereas in Augener's specimen these papillae are mostly located in the anterior part of the body and around the cephalic cage. With regards to chaetae, in T. cucullata sp. nov. the basal region of the notochaetae is long while in Augener's specimen it is shorter; further, in the articulated neurochaetae of Augener's specimen the distal article is more falcate than in T. cucullata sp. nov. The anchylosed neurochaetae of T. cucullata sp. nov. do not show basal constriction, whereas those in Augener's specimen are markedly constricted at the base, more expanded, and their distal articles are more falcate.

The main differences between T. cucullata sp. nov. and T. fernandensis sensu Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) related to the distribution of sediment granules and papillae on the body and the numbers of the noto- and neurochaetae. T. fernandensis sensu Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) lacks sediment particles on the tunic and the papillae are arranged in 15 transverse rows on the median segments while in T. cucullata sp. nov. the sediment granules are more abundant on the first 5 chaetigers and the papillae are not arranged in rows on the body. In T. cucullata sp. nov. the notochaetae are 3–4 per bundle until chaetiger 8, increasing to 4–5 in median and posterior chaetigers, whereas in T. fernandensis sensu Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) they are 4–5 anteriorly and 5–7 posteriorly. In T. fernandensis sensu Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) the number of posteriorly bidentate hooks (2–3) are lesser than in T. cucullata sp. nov. (4–5). Furthermore, in T. cucullata sp. nov. the anchylosed neurohooks start from chaetiger 65, while in T. fernandensis sensu Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) they start from about chaetiger 45. It is important to underline that the redescription of T. fernandensis conducted by Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) was based on specimens collected in the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea and the eastern tropical Atlantic. The author pointed out that this distribution might include more than one species, but that to separate them as distinct species it was necessary to analyse better specimens. Indeed, Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) analysed non-topotypical material and redescribed a single species due to the non-optimal state of conservation of the different individuals analysed. Furthermore, the author noted the presence of differences in their relative sizes of the notochaetae articles: they were shorter in West African specimens and medium- or long-sized in those of the Mediterranean Sea.

Distribution

Know only from type locality, Civitavecchia, Italy, Northern Tyrrhenian Sea.

Ecological notes

All specimens were collected in sandy patches located in two coastal P. oceanica meadows where sediments were composed of gravelly coarse sand with bioclasts. In site B some individuals were also collected in sediment patches colonized by C. cylindracea. The analysis of the macrozoobenthic community sampled in site A revealed that polychaetes were the dominant taxon, mostly represented by the onuphid Aponuphis brementi (Fauvel, Reference Fauvel1916) and the phyllodocid Pseudomystides limbata (de Saint-Joseph, Reference de Saint-Joseph1888). In addition, the amphipods Gammarella fucicola (Leach, Reference Leach and Brewster1814) and Melita palmata (Montagu, Reference Montagu1804) were also well represented in the benthic community. The most abundant macrozoobenthic species sampled in site B were the amphipods Elasmopus brasiliensis (Dana, Reference Dana1853), Microdeutopus chelifer (Bate, Reference Bate1862) and Phtisica marina Slabber, Reference Slabber1769, and the gastropod Haminoea navicula (da Costa, Reference da Costa1778).

Etymology

The species name ‘cucullata’ is inspired by the different colour of the first chaetigers that generates a sort of ‘hood’ on the first 4–5 segments.

Discussion and conclusion

The description of Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. represents the discovery of the 21st species of Trophoniella worldwide, the 22nd species of flabelligerid reported in European waters and the ninth species belonging to this family, as well as the first report of the genus Trophoniella from Italian waters.

The identification of species belonging to the family Flabelligeridae is recognized as being difficult and complex, and above all the distinction between the genera Trophoniella, Piromis and Pycnoderma has been defined as somewhat problematic (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012). In fact, these three genera share several morphological characteristics and can be distinguished mainly in terms of the type of neurochaetae of the median and posterior segments (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012); for these reasons, many species were originally misclassified, and Salazar-Vallejo (Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012) proposed a redefinition and revision of both type and non-type material of the genus Trophoniella. In the last years, very few studies have reported the presence of Trophoniella spp. in Mediterranean waters, with generally low individual abundances (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012; Chaibi et al., Reference Chaibi, Antit, Bouhedi, Gillet and Azzouna2018, Reference Chaibi, Antit, Bouhedi, Meca, Gillet, Azzouna and Martin2019). The complex identification of the flabelligerid polychaetes, the low number of species belonging to the genus Trophoniella in the Mediterranean Sea and the descriptions of only one species in recent years in this basin could justify the lack of reports of the genus Trophoniella along the Italian coasts.

The morphological features of Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. are exclusive to this species and easily distinguish it from other species belonging to the genus. Indeed, the distribution of the sediment grains, which covers only the first 4–5 chaetigers as well as the starting point of the anchylosed neurohooks have never been observed or described in any other species. Although T. cucullata sp. nov. resembles Augener's original description of T. fernandensis, the two species differ both in terms of distribution of the papillae on the body and in chaetal morphology.

All Trophoniella species thrive in superficial sediments and especially in muddy, sandy and mixed substrates of tropical and temperate regions (Salazar-Vallejo, Reference Salazar-Vallejo2012). To date, no Trophoniella species were in association with P. oceanica and C. cylindracea, but it may be interesting to note that an unidentified species of Trophoniella was sampled in Peru from substrates colonized by Caulerpa filiformis (Suhr) Hering, Reference Hering1841 (Pariona Icochea, Reference Pariona Icochea2018). Trophoniella cucullata sp. nov. represents the first species of Trophoniella reported in association with P. oceanica and the first species sampled from gravelly coarse sand with bioclasts. Moreover, some specimens of T. cucullata sp. nov. were collected in a macrozoobenthic community characterized by the presence of species recently recorded for the first time in the Northern Tyrrhenian Sea (Tiralongo et al., Reference Tiralongo, Paladini De Mendoza and Mancini2017; Giangrande et al., Reference Giangrande, Mancini, Tiralongo and Licciano2018; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Tiralongo, Ventura and Bonifazi2019a, Reference Mancini, Tiralongo, Ventura and Bonifazi2019b) highlighting the key role of the marine phanerogam meadows as a biodiversity hotspot.

Acknowledgements

We are particularly grateful to Dr Sergio I. Salazar-Vallejo for his support and contribution in the description of our new species. We also thank the Reviewers for having provided valuable comments that have improved the quality of the manuscript. We are thankful to Dr Francesco Paladini De Mendoza for his support during sampling operations and for his contribution in the analysis and description of the environmental characteristics of the study area.

Author contributions

E.M. collected (scuba diver), analysed and described the specimens and wrote the manuscript. M.L. analysed, described, and photographed the specimens at stereo and optical microscope and wrote the manuscript. A.B. examined the specimens and revised the manuscript. F.T. prepared the map, wrote, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or no-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.