INTRODUCTION

The family Trochochaetidae Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1963, is a small family of spioniform polychaetes known for a single genus Trochochaeta Levinsen, 1883. It included, up to now, eight nominal species and one species, from the northern Gulf of Mexico, described but not formally named, and only known as Trochochaeta sp. A Gilbert, Reference Gilbert, Uebelacker and Johnson1984. The trochochaetids constitute a small and relatively unknown group of polychaetes that, in addition to carrying capillary chaetae, also possess, in the posterior part of the body, the most remarkable eversible spines originally held within sacs; once everted, the process is irreversible and the spines form a wheel-like array that inspired the name of the taxon (Rouse, Reference Rouse, Rouse and Pleijel2001). According to Fauchald & Rouse (Reference Fauchald and Rouse1997), the uniramous parapodia (notopodia missing) in a series of chaetigers in mid-body (Orrhage, Reference Orrhage1964) constitute the evidence for the monophyly in the family.

The organisms now included in the family Trochochaetidae were originally included in the family named Disomidae by Mesnil (Reference Mesnil1897) and later renamed Disomididae by Chamberlin (Reference Chamberlin1919). Initially, the family included the genera Disoma Örsted, Reference Örsted1843 and Poecilochaetus Claparède, 1875, until Hanners (Reference Hanners1956) analysed the larvae and separated Poecilochaetus into a new family, Poecilochaetidae. Later, Pettibone (Reference Pettibone1963) replaced Disoma, since this name was preoccupied by a protozoan, with Trochochaeta Levinsen, 1883, and consequently changed the family name to Trochochaetidae.

The Trochochaetidae have consistently been placed in the group Spionida (Fauchald & Rouse, Reference Fauchald and Rouse1997; Rouse, Reference Rouse, Rouse and Pleijel2001). Blake & Arnofsky (Reference Blake and Arnofsky1999), in their phylogenetic analysis using Cossuridae and Paraonidae as outgroups, concluded that Trochochaeta fell within the Spionidae, along with other until then non-Spionidae, such as Heterospio, Poecilochaetus and Uncispionidae.

The trochochaetids have been recorded in the northern hemisphere only, at depths ranging from 2 m to more than 3700 m (Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976). They build fragile tubes lined with fibrous secretions and sediment particles (Wilson, Reference Wilson, Beesley, Ross and Glasby2000). These polychaetes continuously grow in length and add branches to their tubes, sometimes forming dense mats; they are considered selective bottom deposit-feeders (Fauchald & Jumars, Reference Fauchald and Jumars1979).

In the American littorals, six species have been found: T. carica (Birula, Reference Birula1897), T. pettiboneae Dean, Reference Dean1987 and T. watsoni Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976, all of them on the north-eastern coasts of the USA (Fauvel, Reference Fauvel1916; Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976; Dean, Reference Dean1987; Buzhinskaja & Jørgensen, Reference Buzhinskaja and Jørgensen1997); the unnamed species Trochochaeta sp. A, from the northern Gulf of Mexico (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert, Uebelacker and Johnson1984); T. multisetosa (Örsted, Reference Örsted1843) from the north-eastern coasts of the USA and Canada (Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976) and from San Francisco Bay in the Pacific Ocean (Hartman, Reference Hartman1947); and finally, T. kirkegaardi Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976, the only species recorded previously from the tropical eastern Pacific, collected in the subtidal zone of the Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica (Dean, Reference Dean1996). Before the present study, the family had not been reported from the Mexican Pacific, in the Mexican Biogeographic Province as defined by Hastings (Reference Hastings2000).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study is based on new material collected from the southern Mexican Pacific, on board the RV ‘El Puma’ from the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (ICMyL), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), during the oceanographic expedition ‘Sedimento 1’ from 15–28 November 1996. The positions of the stations were determined by Global Positioning System (GPS) and the samples were collected with a Smith–McIntyre grab (0.1 m2). The biological material was fixed in 4% formaldehyde and preserved in 70% ethanol. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) photographs were taken with the JEOL JSM6360LV equipment following standard methods.

The holotype and paratypes are deposited respectively at the National Polychaete Collection located in the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNP-ICML, UNAM; DFE.IN.061.0598), and the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History (LACM-AHF POLY), USA.

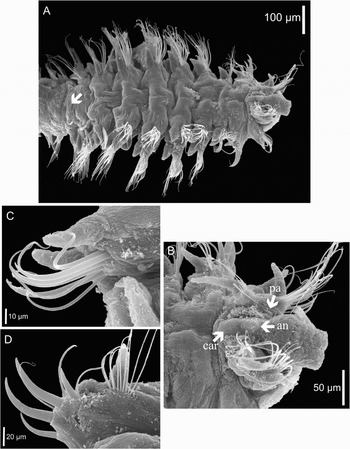

Fig. 1. Scanning electron microscopy micrographs of Trochochaeta mexicana sp. nov. (A) anterior and mid-body region, dorsal view, the arrow points to transition between thorax and abdomen; (B) prostomium and first parapodium, dorsal view, arrows point to position of palp (pa), antenna (an) and caruncle (car); (C) second parapodium, anterior view; (D) third parapodium, anterior view.

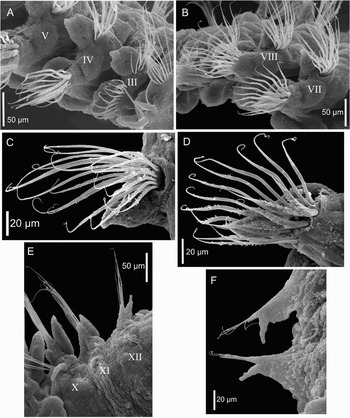

Fig. 2. Scanning electron microscopy micrographs of Trochochaeta mexicana sp. nov. (A) parapodia 3–5, lateral view, roman numerals = number of chaetiger; (B) parapodia 7–8, lateral view, roman numerals = number of chaetiger; (C) posterior thoracic notopodium, anterior view; (D) posterior thoracic neuropodium, anterior view; (E) parapodia 10–12, dorsal view, roman numerals = number of chaetiger; (F) anterior abdominal parapodia, dorsal view.

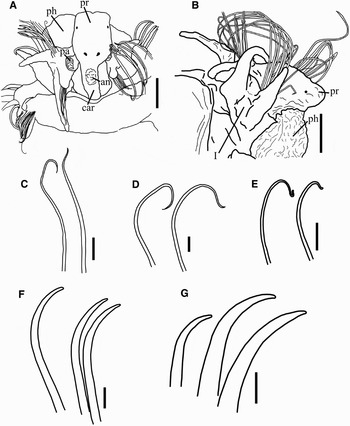

Fig. 3. (A) Anterior end, dorsal view, prostomium (pr), palp (pa), antenna (an), caruncle (car) and partially everted pharynx (ph); (B) prostomium and first parapodium, lateral view, prostomium (pr), pharynx partially everted (ph) and first chaetiger (I); (C) smooth capillaries from thoracic notopodia; (D) smooth capillaries from neuropodium 2; (E) smooth capillaries from notopodium 3; (F) acicular spines from neuropodium 2; (G) acicular spines from neuropodium 3. Scale bars: A, B, 50 µm; C, D, F, 10 µm; E, G, µm.

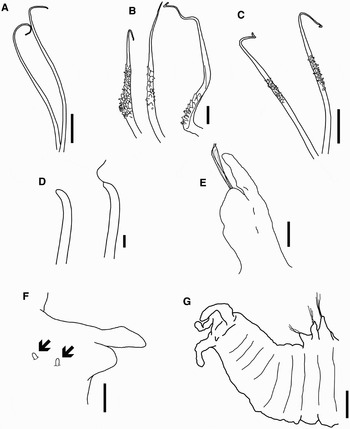

Fig. 4. (A) Smooth capillaries from posterior thoracic neuropodium; (B) capillaries with short, hair-like projections near their basal section; (C) capillaries with short, hair-like projections near their distal margin; (D) abdominal acicular chaetae with or without a terminal sheath projection; (E) anterior abdominal neuropodia; (F) posterior abdominal parapodium, showing tips of spines on dorsum (neurochaetae not drawn); (G) posterior end and pygidium. Scale bars: A, C, 20 µm; B, E, 10 µm; D, 2 µm; F, 2.5 µm; G, 5 µm.

TYPE MATERIAL

Holotype: expedition ‘Sedimento 1’, Station 76, Guerrero coast; coordinates: 16° 16.3′N 98° 36.0′W; water depth: 40 m) (CP-ICML: POH–11–001). Collected by P. Hernández-Alcántara, 19 November 1996.

Paratypes: expedition ‘Sedimento 1’, Station 76, Guerrero coast; coordinates: 16° 16.3′N 98° 36.0′W; water depth: 40 m) (CP-ICML: POP–11–001, 3 paratypes, one of them coated with gold for SEM studies) (LACM-AHF POLY 2468, 2 paratypes). Collected by P. Hernández-Alcántara, 19 November 1996.

DIAGNOSIS

Body slender, thorax with 11 chaetigers. Prostomium elongate with a small knob-like antenna and a nuchal crest projecting through chaetiger 1; two pairs of minute eyes. Second parapodia biramous but without notochaetae. Acicular spines on neuropodia 2 and 3, those form third chaetiger clearly heavier. Postchaetal lobes broad and subcylindrical (sometimes referred to as dorsal and ventral cirri) with margins entire. Anterior abdomen lacks notopodia, which reappear at the end of the posterior abdominal region as low mounds with a few pointed acicular spines. A few posterior chaetigers cylindrical and achaetous; pygidium with two pairs of short cirri.

DESCRIPTION

Holotype complete with 41 chaetigers: 3.13 mm long and 0.38 mm wide (at its greatest width in the thoracic region, not including chaetae). All paratypes incomplete with up to 24 chaetigers (posterior segments missing): 1.25 to 2.38 mm long and 0.35 to 0.63 mm wide. Body slender, divided into a short dorsally flattened anterior thoracic region (4 first chaetigers) and 6 chaetigers representing the posterior thoracic region; the body becomes thinner at chaetiger 11, marking the transition to the abdominal region (Figure 1A). In all the specimens analysed, the abdomen begins at chaetiger 12 (Figure 2E); the anterior abdomen lacks notopodia (Figure 2F); abdominal neuropodia with slender capillaries and stouter acicular chaetae with and without a terminal sheath projection resembling a fine thread (Figure 4D). Notopodia reappear at the end of the posterior abdominal region as low mounds with a bundle of few, pointed acicular spines; in the specimens analysed the acicular spines are withdrawn and only in a few chaetigers the tips of the spines are projected (Figure 4F). Fixed specimens are dull throughout the body. Prostomium elongate, wide and slightly bilobed anteriorly, with a more or less well developed median crest extending posteriorly as a narrow caruncle, down to the posterior margin of the first chaetiger; with a small knob-like median antenna on the anterior region of the crest (Figures 1B & 3A). Two pairs of minute eyes embedded: first pair in the median-posterior region of the prostomium and second pair in antero-lateral position (Figure 3A, B). Tentacular palps cylindrical, with longitudinal ciliated groove along inner side, deciduous, but oval bases were observed between the prostomium and the parapodia of first chaetiger (Figure 1B). Mouth on ventral side of the peristomial ring; pharynx eversible, unarmed, looks like a ciliated lobulated pouch (Figure 3B).

Anterior four chaetigers of thoracic region with biramous parapodia, each one differing considerably from the other (Figure 1A). All anterior thoracic notopodia, except at chaetiger 2, with fan-shaped bundles of large and smooth capillaries (Figure 3C, E). The first, or buccal segment, enlarged ventrally, enclosing the large triangular mouth; with biramous parapodia shifted dorsally and projecting anteriorly (Figure 3B); bundles of smooth capillary notochaetae (Figure 3C), and longer smooth capillary neurochaetae (Figures 1B & 3B). Notopodial and neuropodial chaetal lobes indistinct. Notochaetae relatively few (about 8); neurochaetae numerous, forming fan-shaped spreading bundles of two types: the largest and stoutest are in the posterior edge of the bundle (Figure 1B). Notopodial and neuropodial postchaetal lobes subconical, elongate, subulate and wider basally (Figure 3A).

Second chaetiger closely apposed to the first (Figure 1A); parapodia biramous but without notochaetae (Figure 1C); neuropodial chaetal lobe low and wide. Neuro- and notopodial postchaetal lobes subconical, similar to those of the first chaetiger (Figure 2C). Two kinds of chaetae found in neuropodia: a posterior row with large smooth capillaries (Figure 3D) and an anterior row with curved, thicker acicular spines ending in sharp tips (Figure 3F).

The following two chaetigers (3 and 4) with lateral parapodia, somewhat modified relative to the more posterior thoracic ones; notopodial chaetal lobes low and neuropodial chaetal lobes wide and low (Figure 2A). The third chaetiger with postchaetal lobes subconical in both parapodial branches (Figure 1D). Notopodia with large capillaries (Figure 3E). Neuropodia with few smooth capillaries distributed in a posterior row, and 4–5 brown, smooth, stout, curved acicular spines placed in an anterior row (Figure 1D), clearly heavier than acicular spines from second chaetiger (Figure 3G).

Fourth chaetiger with lateral parapodia and chaetal lobes low and rounded. Postchaetal lobes similar to those of the following chaetigers; they are broad and subcylindrical with borders entire, tapering distally to digitiform tips, which are broader and more flattened on the neuropodia (Figure 2A). Notochaetae smooth, very large capillaries ending in curved fine tips (Figure 4A), arranged in two rows. Neuropodia also with fan-shaped bundles of very large capillaries, but of two kinds: those on the anterior row with numerous and very fine, short, hair-like projections on the exterior margin near their basal section (Figure 4B); those on the posterior row also with short, hair-like projections on one side, but located near their distal margin (Figure 4C).

On the remaining thoracic region, chaetigers 5 to 10 are similar, with lateral biramous parapodia (Figure 2B). Notopodial chaetal lobes low, rounded, with capillaries arranged in two rows (Figure 2C), decreasing in number towards the posterior thorax: chaetae in the anterior row with very fine, short, hair-like projections near their basal margin similar to those of chaetiger 4 (Figure 4B); chaetae in the posterior row also with short, hair-like projections, but near their distal margin (Figure 4C). Notochaetae similar to neurochaetae but clearly smaller (Figure 2C, D). Neuropodial chaetal lobes subcylindrical, with bundles of neurochaetae of two kinds: a posterior row with smooth and very long capillaries, and an anterior row with capillaries similar to the ones observed on chaetiger 4, that also exhibit somewhat frayed sheaths which appear as hair-like projections (Figure 2D). In this case, they are distributed along most of the chaetal shaft.

Parapodial postchaetal lobes are initially similar, but larger and stouter than those observed on parapodium 4 (Figure 2B); notopodial postchaetal lobes wide and subconical, becoming gradually slender, small, and digitiform on posterior thoracic chaetigers (Figure 2E); neuropodial lobes subcylindrical with borders entire. From chaetiger 5, muscular pads present below ventral edges of neuropodia (Figure 2B), gradually reducing in size to finally disappear at chaetiger 12 (first chaetiger of abdominal region).

At the transitional region (chaetiger 11), the body becomes markedly thinner, and both notopodia and notochaetae practically disappear, only represented by a small papilla (Figure 2E). Neuropodial lobes become smaller, with subconical postchaetal lobes and a few smooth, slender capillary neurochaetae.

Anterior abdominal region begins at chaetiger 12; it is long and slender, without notopodia or notochaetae (Figure 2F). Neuropodial chaetal lobes small and rounded, with a few slender, smooth capillaries, and 1–3 stouter acicular chaetae with and without a terminal sheath projection as fine thread (Figure 4D). Postchaetal neuropodial lobes elongate, broader basally, becoming smaller towards posterior parapodia (Figure 4E). Posterior abdominal chaetigers with embedded notopodial spines, without notopodial lobes; most of the notopodial spines are withdrawn, except for some tips visible on few chaetigers (4F). A few posterior segments cylindrical and achaetous. Pygidium with two pairs of short cirri (4G).

REMARKS

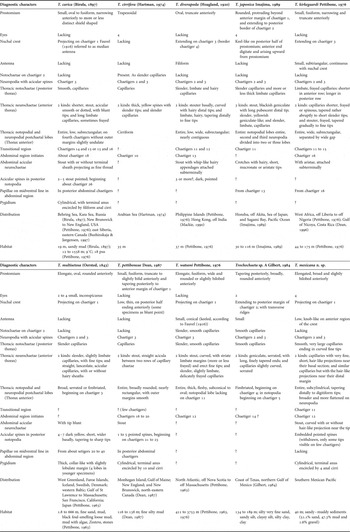

Some morphological characteristics of the specimens from the Mexican Pacific do not agree with any trochochaetid known to date: a number of remarkable differences were observed. First, all the species in this family can be divided into two groups: those with noto- and neurochaetae present in all thoracic parapodia (Trochochaeta watsoni Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976; T. cirrifera (Hartman, Reference Hartman1947); T. sp. A) and those without notochaetae in chaetiger 2 (Table 1). Trochochaeta mexicana sp. nov. belongs to this second group and, in addition, resembles T. multisetosa (Örsted, Reference Örsted1843), T. diverapoda (H oagland, 1920), T. japonica Imajima, Reference Imajima1989 and T. kirkegaardi Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976, in having stout acicular neurochaetae on chaetigers 2 and 3. In contrast, T. carica and T. pettiboneae display stout acicular neurochaetae on chaetiger 2 only.

Table 1. Comparison among Trochochaeta species.

The above-mentioned four established species with acicular neurochaetae on chaetigers 2 and 3 have previously been recorded in the Pacific Ocean (Figure 5). Trochocheta multisetosa, having noto- and neuropodial serrated postchaetal lobes on some anterior chaetigers, can be separated from the other trochochaetids that carry postchaetal lobes with their border entire.

Fig. 5. World distribution of described Trochochaeta species.

Trochochaeta mexicana sp. nov., however, can be separated from T. japonica by the presence of a small knob-like antenna in the former, absent in the latter and in that in the former, the median crest projects on chaetiger 1 instead of arising upwards from the prostomium. Finally, T. diverapoda and T. kirkegaardi are different from T. mexicana sp. nov., not only because of the distinct shape of their prostomium, and their lack of eyes, but because their median crest is longer (extending to chaetiger 3), and also because they carry stout and curved modified neurochaetae, tapered to slender fine tips, from chaetiger 5.

ETYMOLOGY

The new species is named after the type locality, in the southern Mexican Pacific.

TYPE LOCALITY

Guerrero coast, southern Mexican Pacific (Mexican Biogeographic Region).

HABITAT

The specimens of T. mexicana sp. nov. are rare in the Mexican Pacific coasts; they were found at 40 m depth and in bottoms with sandy–muddy sediments (51.1% sand, 47.3% mud and 1.6% gravel).

DISCUSSION

Pettibone (Reference Pettibone1963, 1976), in her careful review of most of the species described until then, and having examined all available type material, concluded that only six of the ten species described were valid. Later, Mackie (Reference Mackie and Morton1990) examined specimens of one of those six species from Hong Kong and the syntypes from the Philippine Islands (T. orissae) and agreed with Pettibone's (1976) decision to synonymize it with T. diverapoda. However, although Pettibone (Reference Pettibone1976) overlooked T. cirrifera described from the Arabian Sea (Hartman, Reference Hartman1974), this species could be considered valid because of its evident differences from other trochochaetid species: it is the only species with cirriform instead of subconical notopodial postchaetal lobes in the fourth chaetiger. Finally, Dean (Reference Dean1987) and Imajima (Reference Imajima1989) described two more species which, together with Trochochaeta sp. A (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert, Uebelacker and Johnson1984), add up to the nine species currently accepted (Table 1). No other species from this family were described in the intervening twenty years, until this study of the continental shelf of the southern Mexican Pacific.

The number of species described so far in this family (nine) is very small (Table 1). The detailed review made by Pettibone (Reference Pettibone1963, Reference Pettibone1976) and the more recent studies carried out by Dean (Reference Dean1987), Imajima (Reference Imajima1989), Mackie (Reference Mackie and Morton1990), and Buzhinskaja & Jørgensen (Reference Buzhinskaja and Jørgensen1997) provided additional data to supplement the descriptions of previously identified species, and allowed the correct identification of specimens erroneously assigned to other species. Those studies increased our taxonomic knowledge of the family and usefully support the present discussion about the new species.

In this sense, before the description of T. mexicana sp. nov., only two species had been recorded from the eastern Pacific (Figure 5): (1) T. multisetosa from San Francisco, California, also widely recorded from temperate and cold waters from the north-eastern USA, West Greenland, Faroe Islands and Iceland, as well as in Swedish and Danish waters, the western Baltic and northern Japan (Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1963); and (2) T. kirkegaardi, collected from the Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica (Maurer & Vargas, Reference Maurer and Vargas1984; Maurer et al., Reference Maurer, Vargas and Dean1988; Dean, Reference Dean1996), which is the trochochaetid found closest to the Equator, and which was originally recorded from Liberia and Nigeria coasts (eastern Atlantic) (Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976). All the species distributed in the American Pacific clearly differ among themselves: the temperate–cold species T. multisetosa has no antenna, and it is the only trochochaetid with serrated thoracic postchaetal lobes, whereas the tropical species T. kirkegaardi and T. mexicana sp. nov. both bear a small antenna but, in the latter, a pair of eyes are present and its median crest is shorter, extending only to the first chaetiger (Table 1).

Members of the Trochochaetidae occur rarely in the world seas (Figure 5). The north-eastern USA and the western littorals of the Pacific Ocean are the regions where most trochochaetids have been recorded (four species in each region), and this can be partly due to the fact that it is there where the studies on this family have been most numerous (Örsted, Reference Örsted1843; Birula, Reference Birula1897; Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1963, Reference Pettibone1976; Dean, Reference Dean1987; Imajima, Reference Imajima1989; Mackie, Reference Mackie and Morton1990).

Although T. japonica, T. cirrifera, T. sp. A and the newly described species T. mexicana have been recorded only from their type locality the other species of this family were reported from at least two oceans of the world. Moreover, the trochochaetids are mainly distributed in the temperate–cold regions of the northern hemisphere. Trochochaeta carica and T. multisetosa are the species with the widest distribution, since they were recorded in the northern Atlantic and Pacific. In contrast, T. kirkegaardi, T. diverapoda, T. cirrifera and T. mexicana have been recorded only in warm waters between the Tropic of Cancer and the Equator although, as mentioned above, the last two have been found only in their type locality (Figure 5).

Finally, given the irregular distribution of this particular family of polychaetes around the world, their scarce presence, and the record of only three species on the coasts of the eastern Pacific, we think that there may be many more undiscovered trochochaetids in this American region.

KEY TO THE SPECIES OF TROCHOCHAETA

1. With noto- and neurochaetae in all thoracic parapodia . . . . . . . 2

– Without notochaetae in chaetiger 2 . 4

2. Postchaetal lobes thick and subconical . 3

– Postchaetal lobes cirriform. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . T. cirrifera (Hartman, Reference Hartman1974)

3. Postchaetal lobes serrated or fimbriated . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . T. sp. A Gilbert 1984

– Postchaetal lobes entire, not serrated or fimbriated T. watsoni Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976

4. Stout acicular neurochaetae on chaetiger 2. . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

– Stout acicular neurochaetae on chaetigers 2 and 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

5. 13–15 thoracic chaetigers; 4–8 filiform anal cirri . . . . . . . . T. carica (Birula, Reference Birula1897)

– 15–19 thoracic chaetigers; 10 digitate anal cirri . . . . . T. pettiboneae Dean, Reference Dean1987

6. Postchaetal lobes serrated or fimbriated . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . T. multisetosa (Örsted, Reference Örsted1843)

– Postchaetal lobes entire, not serrated or fimbriated . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

7. Prostomium without antenna; median crest projects on chaetiger 1 T. japonica Imajima, 1989

– Prostomium with antenna; median crest arising upwards from the prostomium. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

8. Prostomium with nuchal crest extending on chaetiger 1; with four eyes; without modified neurochaetae . . . . . . . . . . Trochochaeta mexicana sp. nov.

– Prostomium with nuchal crest extending on chaetiger 3; without eyes; with stout and curved modified neurochaetae, tapered to slender fine tips, from chaetiger 5 . . . . . . 9

9. Prostomium with filiform antenna . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . T. diverapoda (Hoagland, Reference Hoagland1920)

– Prostomium with small subtriangular antenna, continuous with nuchal crest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . T. kirkegaardi Pettibone, Reference Pettibone1976

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank very specially Juan Pérez Torrijos for his help in the identification process, Yolanda Hornelas Orozco for her valuable help with the SEM photographs, and Arturo Carranza Edwards, head of the project ‘Sedimento’, for inviting us to participate and collect the material used here.