INTRODUCTION

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents host highly productive communities fuelled primarily by chemosynthetic microbial production and characterized by low species richness but high proportion of endemic species, and a large biomass in contrast with the surrounding deep-sea floor. The limited lifespan of vent sites, related to sea-floor spreading rate and frequent volcanic eruptions, leads to the creation of transient habitats, patchily distributed around vent sites separated from 10s of metres to 100s of kilometres. Within a single vent site, the high spatio-temporal variability of environmental conditions in terms of temperature, pH, and concentrations of oxygen, sulphide and metals (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Childress, Beehler and Sakamoto-Arnold1994; Sarradin et al., Reference Sarradin, Caprais, Briand, Gaill, Shillito and Desbruyères1998; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003, 2006b) produces a mosaic of habitats with contrasted biological characteristics (Sarrazin et al., Reference Sarrazin, Robigou, Juniper and Delaney1997; Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998; Sarrazin & Juniper, Reference Sarrazin and Juniper1999). Organisms are distributed in different assemblages around the vent, and their composition varies in space and time in relation with the decreasing gradient of fluid exposure, the physical structure of the mineral substrate and the temporal dynamics of vent colonization (Sarrazin et al., Reference Sarrazin, Robigou, Juniper and Delaney1997; Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998). On the East Pacific Rise (EPR), 4 main megafaunal assemblages have been described: (i) alvinellid polychaete colonies restricted to the most active areas of chimney walls with high-temperature emissions; (ii) vestimentiferan tubeworm assemblages in recent and active diffuse flow areas; (iii) bivalve assemblages in moderate and older diffuse flow areas; and (iv) suspension-feeder assemblages dominated by serpulid polychaetes and barnacles at the periphery of vents in seawater with little or no hydrothermal influence (Jollivet, Reference Jollivet1996; Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998).

The influence of environmental factors in shaping hydrothermal communities appears quite complex, and some non-exclusive hypotheses are still debated. According to the correspondence between physico-chemical gradients and faunal zonation, several ecological studies have related the variability of faunal composition in space and time to changes in environmental conditions, putting much emphasis on physiological tolerances and nutritional requirements of organisms (Sarrazin et al., Reference Sarrazin, Robigou, Juniper and Delaney1997; Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998). In this context, two physico-chemical parameters were commonly referred to as potentially determinant: temperature (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Tunnicliffe and Lee2005; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Mullineaux and Tyler2007), and sulphide which is both a major electron donor for chemoautotrophic microbes and a potent poison for aerobic organisms (Childress & Fisher, Reference Childress and Fisher1992). However, more than total sulphide concentration, it was pointed out that differences in chemical speciation of sulphide among habitats may be a key-factor driving the distribution of species (Luther et al., Reference Luther, Rozan, Martial, Nuzzio, Di Meo, Shank, Lutz and Cary2001). Although total acid-volatile sulphide concentrations (H2S+HS−+FeS(aq)) were shown to be at least 5 times higher in an Alvinella pompejana colony than in a Riftia pachyptila clump, these authors found that FeS(aq) was the dominant sulphide phase in the former habitat while free sulphide (H2S+HS−) was the major form in the latter. FeS formation was therefore proposed to act as a sulphide detoxification mechanism in Alvinella colonies. The importance of this process depends largely on the dissolved iron to sulphide ratio which is known to be highly variable among habitats (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Govenar, Le Gall and Fisher2006a; Le Bris & Gaill, Reference Le Bris and Gaill2007), resulting from end-member fluid composition variability in space and time (Von Damm & Lilley, Reference Von Damm, Lilley, Wilcock, DeLong, Kelley, Baross and Cary2004). Conversely, Govenar et al. (Reference Govenar, Le Bris, Gollner, Glanville, Aperghis, Hourdez and Fisher2005) showed that the structure and composition of the epifaunal community associated with different R. pachyptila clumps were remarkably similar between sites and independent of sulphide and iron concentrations. Likewise, Mullineaux et al. (Reference Mullineaux, Fisher, Peterson and Schaeffer2000) suggested that the settlement of the two vestimentiferan species, R. pachyptila and Oasisia alvinae, was independent of tolerances to physico-chemical conditions but rather facilitated by the occurrence of Tevnia jerichonana. While biotic interactions between organisms (i.e. facilitation, competition and predation) could be major determinants of community structure (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Peterson, Mullineaux, Fisher, Mills, Sancho, Johnson and Lenihan2002), they were shown to vary along the gradient of flow intensity with facilitation processes occurring at the periphery of vents, where animal density is lower, and inhibition processes occurring in the high diffuse vent flow areas (Mullineaux et al., Reference Mullineaux, Peterson, Micheli and Mills2003). More recently, Mills et al. (Reference Mills, Mullineaux and Tyler2007) suggested that most hydrothermal gastropod species are not exclusive to a specific megafaunal zone as they may occupy specific microhabitats.

In other respects, physico-chemical conditions could also play a significant role in population dynamics of deep-sea hydrothermal species (e.g. growth, survivorship and reproduction) although very few studies addressed directly these questions (Mullineaux et al., Reference Mullineaux, Mills and Goldman1998; Copley et al., Reference Copley, Tyler, Van Dover and Philip2003; Kelly & Metaxas, Reference Kelly and Metaxas2007). While reproductive cycles of lepetodrilids were described to be quasi-continuous within females and asynchronous among females (Pendlebury, Reference Pendlebury2004), Kelly & Metaxas (Reference Kelly and Metaxas2007) reported that the rate of gametogenesis of Lepetodrilus fucensis could vary between habitat types. By controlling the abundance and the turnover of local populations, one can expect that these spatial variations in biological features may affect the intensity of biological interactions and the structure of benthic communities.

On hydrothermal vents of the East Pacific Rise, the alvinellid polychaetes A. pompejana and A. caudata inhabit the surface of active sulphide structures, presumably in the most hypoxic and toxic conditions found in these environments (Le Bris & Gaill, Reference Le Bris and Gaill2007), and are known as the very first macrofaunal colonizers of new chimney habitats (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Wirsen and Gaill1999; Pradillon et al., Reference Pradillon, Zbinden, Mullineaux and Gaill2005b). In these extreme environmental conditions, biological adaptations and community structure are expected to be mostly driven by biogeochemical processes (Luther et al., Reference Luther, Rozan, Martial, Nuzzio, Di Meo, Shank, Lutz and Cary2001). However, most studies on processes involved in hydrothermal community structure were conducted on mussel beds or vestimentiferan clumps (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Peterson, Mullineaux, Fisher, Mills, Sancho, Johnson and Lenihan2002; Mullineaux et al., Reference Mullineaux, Peterson, Micheli and Mills2003; Tsurimi & Tunnicliffe, Reference Tsurimi and Tunnicliffe2003; Van Dover, Reference Van Dover2003; Govenar et al., Reference Govenar, Freeman, Bergquist, Johnson and Fisher2004; Dreyer et al., Reference Dreyer, Knick, Flickinger and Van Dover2005) and faunal distribution in Alvinella colonies remains poorly known (Desbruyères et al., 1998). Focusing on gastropods, which represent a major part of vent fauna in terms of density and diversity in different habitats (Jollivet, Reference Jollivet1996; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Mullineaux and Tyler2007), the aims of the present study were: (1) to better characterize the physico-chemical variability of habitats at the surface of A. pompejana colonies from the 13°N-EPR vent field, from the assessment of, both, fine scale temperature ranges and correlations of temperature with chemical factors that were measured in situ; pH, sulphide and iron concentration ranges were thus determined over spatial scales as relevant as possible to the conditions experienced by gastropods; (2) to relate these environmental ranges to the variability in the composition of faunal assemblages at different scales; and (3) to assess the relationships between population biology and environmental conditions with Lepetodrilus elevatus as an example. This species was chosen as it displayed a wide distribution in hydrothermal habitats (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Mullineaux and Tyler2007) and was reported to be a highly competitive species in hydrothermal faunal assemblages (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Peterson, Mullineaux, Fisher, Mills, Sancho, Johnson and Lenihan2002). Additional samples from R. pachyptila clumps were also analysed for comparison with Alvinella habitats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites

All physico-chemical and biological data were collected using the ROV ‘Victor 6000’ during the PHARE cruise carried out in May 2002 on the 13°N vent field along the East Pacific Rise (EPR). A hierarchical sampling method involving three spatial scales was undertaken for biological sampling (Table 1): (1) three vent sites, Genesis, Parigo and Elsa located at a depth of ~2620 m and spaced by 100s of metres; (2) two active sulphide structures (here referred to as ‘vents’) within each site at a scale of 10s of metres; and (3) one to six samples within each structure at a scale of metres. On the Genesis site, the PP12 vent is a small diffuser colonized by dense colonies of Alvinella pompejana at the top and Riftia pachyptila clumps around. On the opposite, the Hot 2 vent consisted in a large diffuse flow area on the side of a cliff with dense colonies of R. pachyptila and no A. pompejana colony present. The Parigo site was composed of three sulphide edifices including two small diffusers and one tall chimney. The PP-Ph05(1) diffuser is covered by dense A. pompejana colonies largely mixed with R. pachyptila tubes while the PP-Ph05(2) vent is a high chimney with large colonies of A. pompejana or uncolonized surfaces on the upper half and R. pachyptila clumps on its basis. On the Elsa site, PP-Ph01 vent is a massive black smoker inhabited by large colonies of A. pompejana, at the top and intermediate height, and the occurrence of large uncolonized surfaces. The Hot 3 vent is a 3 m diameter white smoker with dense colonies of A. pompejana at the top and R. pachyptila clumps around (Pradillon et al., Reference Pradillon, Le Bris, Shillito, Young and Gaill2005a).

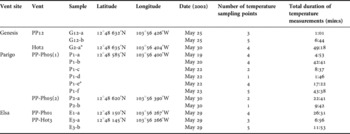

Table 1. Location of the study sites and biological samples. For each sample, the number of temperature sampling points and the duration of temperature measurements used to characterize the physico-chemical habitat are given. *indicates samples collected in Riftia clumps.

Chemical analysis and definition of environmental parameters

In a first step, extensive in situ measurements of temperature, pH, total sulphide and reduced iron in the environment surrounding the gastropods, were conducted for each vent during different dives, using the submersible flow analyser Alchimist (AnaLyseur CHIMIque In SiTu) combined with temperature and pH probes (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin, Birot and Alayse-Danet2000). Colorimetric flow injection analysis (FIA) methods were used to detect the most labile fraction of acid volatile sulphide S(-II) and labile forms of ferrous iron, Fe(II). S(-II) includes free sulphide forms, aqueous iron sulphide forms and freshly precipitated iron sulphide colloids (i.e. HS−, H2S, FeS(aq), Fe(HS)+ and FeS(am)) (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003). In situ pH measurements were made using an autonomous deep-sea sensor (MICREL, France) equipped with a combined glass electrode and a miniaturized thermocouple that was specifically designed for these hydrothermal environments (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Pennec2001). Due to logistical constraints, no chemical data were available for the Riftia zone at Genesis Hot 2 vent which was therefore excluded from the analysis on the relationships between biological and environmental data.

For each vent, this first step allowed to assess the relationships between temperature and sulphide, iron, and pH respectively, assuming the conservative mixing of a local hydrothermal fluid and seawater for a single alvinellid aggregation. This conservative mixing assumption was shown to be consistent for the water layer at the surface of an alvinellid colony in the vicinity of a local source (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005). Hence, iron and sulphide concentrations could be estimated for each sample using the linear correlations established for the corresponding hydrothermal structure. Similarly, pH was estimated from empirical logarithmic correlations. In a second step, just before biological sampling, time-series measurements of temperature over duration ranging from 1 to 50 minutes were performed at 1 to 5 sampling locations in the biological sampling area using the Pt100 temperature probe of the ROV ‘Victor 6000’ (Table 1). To ensure that they are representative of the micro-habitats surrounding the organisms, time-series were selected from the close-up video imagery acquired simultaneously, and only data corresponding to a probe position ~0–2 cm above the surface of the Alvinella colony were retained. For each biological sample, mean, maximum and minimum temperature were then defined while mean, minimal and maximal values of pH, sulphide and iron were calculated from the correlations previously established for each vent.

Biological samples collection

All biological samples were obtained from Alvinella pompejana colonies, except two of them which corresponded to the collection of Riftia pachyptila clumps. Fauna was collected using the hydraulic arm of the ROV, occasionally completed with the ROV suction device, on an area from ~400 to 700 cm2. On board, samples were washed on a 1 mm mesh sieve and fixed with 10% neutral formalin in seawater. In the laboratory, all gastropod specimens were sorted, identified to the species level when possible and then transferred to 70° ethanol.

Analysis of community structure

Multivariate analyses were performed with the software PRIMER v.5 in order to group the samples according to their faunal composition using the Bray–Curtis similarity index calculated from standardized and square-root transformed species-abundance data. The initial standardization consists in calculating the relative abundance of each species by dividing each count by the total abundance of all individuals in the sample, and consequently removes any effect due to differences in sample volumes (Clarke & Warwick, Reference Clarke and Warwick2001). Data were presented using two complementary graphic approaches: cluster using group-average linking, and non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). For each faunal assemblage, species-effort accumulation curves with 95% confidence intervals were generated from species-abundance data using EstimateS v.7.5 (Colwell, Reference Colwell2005) to compare biodiversity distribution from samples of very different size.

In order to assess the environmental influence on the community structure, faunal data were linked to environmental factors using the BIO-ENV procedure within the PRIMER program (Clarke & Ainsworth, Reference Clarke and Ainsworth1993). The different steps of this procedure are as follows. A biotic matrix based on Bray–Curtis similarity index from faunal data and abiotic matrices based on the Euclidean distance from environmental factors are established. While the among-samples similarity matrix was calculated once, the equivalent matrix on abiotic data was computed many times at different levels of complexity (i.e. k variables at a time, where k = 1, 2, 3 … . , N). The best matches of biological and environmental matrices at increasing levels of complexity were measured using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρω). Minimal values of temperature, S(-II) and Fe(II), and maximal pH were excluded from the analysis as they were assumed to not be significant for organism distribution. The natural turbulence of the environment and the difficulties for precise positioning of probes restricted the reliable definition of these extrema at the organism-scale. It can be reasonably assumed that they should represent surrounding seawater conditions, as shown in other vent habitats where background seawater conditions are recovered within a few centimetres from invertebrate aggregations (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Childress, Hessler, Sakamoto-Arnold and Beehler1988; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Rodier, Sarradin and Le Gall2006b). To ensure that colinearity among the 8 remaining environmental variables (i.e. mean and maximal values of temperature, S(-II) and Fe(II), and mean and minimal pH) did not affect results, 2 of them which have mutual correlations above 0.75 were excluded from the analysis: minimal pH and mean temperature.

Population biology of Lepetodrilus elevatus

The demographic population structure of Lepetodrilus elevatus was analysed for the Genesis site and the Parigo PP-Ph05(1) vent where this species was in sufficient number (i.e. >100 individuals). The curvilinear shell length (Lcurv), defined as the total length from the anterior edge of the shell to the lip of the protoconch, was used as a size index (Sadosky et al., Reference Sadosky, Thiébaut, Jollivet and Shillito2002). Measurements were conducted under the ‘Image tool’ image analysis software (University of Texas, http://www.uthscsa.edu/dig/download/html) with an error fixed at 0.14 mm. All specimens in a sample were measured except for the two very large samples from the collection of Riftia pachyptila clumps for which a random subsample of ~500 individuals was used. Size–frequency histograms were constructed using a size-class of 0.4 mm according to three criteria (Jollivet et al., Reference Jollivet, Empis, Baker, Hourdez, Comtet, Jouin-Toulmond, Desbruyères and Tyler2000): (1) most size-classes must contain at least 5 individuals; (2) the number of empty adjacent classes must be minimized; and (3) the size-class interval has to be much greater than the error of measurement. Size–frequency distributions were compared among samples using a Kruskal–Wallis multi-sample test (Zar, Reference Zar1999).

All previously measured individuals with a curvilinear length >3 mm were sexed to determine the sex-ratio which was compared to a theoretical sex-ratio 1:1 with a χ2 goodness-of-fit test. Males were identified by the presence of a large penis, modified from the left cephalic tentacle. In addition, sexual maturity of females was assessed from histological examination of gonads (Pendlebury, Reference Pendlebury2004; Kelly & Metaxas, Reference Kelly and Metaxas2007). Depending on the sample size, 1 to 11 females per vent were analysed. Bodies of females stored in 70° ethanol were removed from their shell, dehydrated in 100° ethanol for at least 6 hours, cleared in xylene for 6 hours and embedded in paraffin wax in a 70°C oven for approximately 12 hours. Individuals were then set in wax blocks and 2 to 3 serial sections of 7 µm thickness were obtained with a microtome. Sections were stained using the picro indigo carmin method which stains nucleus in brown and cytoplasm in green (Gabe, Reference Gabe1968). For each female, 14 to 229 oocytes, in which the nuclei were visible, were measured from images captured under a microscope. As packing of the oocytes can severely distort the oocyte shape, Feret diameter was calculated from the measure of the oocyte area using the Lucia software (Laboratory Imaging Ltd.). Intra- and intersample synchrony of female reproductive development was determined using a Kruskal–Wallis multi-sample test to compare the oocyte size–frequency distributions. When significant differences occurred, a multiple range test using the Dunn–Nemenyi procedure was performed (Zar, Reference Zar1999).

RESULTS

Physico-chemical environment

At the surface of alvinellid colonies, the mean temperature varied from 6 to 32°C among samples (Table 2). It was globally higher for the Genesis PP12 samples, varying between 25 and 32°C, and lower for the Parigo samples, ranging between 7 and 12°C at PP-Ph05(1), and 15 and 16°C at PP-Ph05(2). At the Elsa site, large differences in mean temperature were observed between the samples from the two vents. While it did not exceed 6°C at PP-Ph01, it reached 24 and 20°C respectively for the 2 samples from PP-Hot3. The range of temperature oscillations was highly variable but tended to be wider as the average temperature increased. Thus, for the Genesis PP12 vent, which displayed the highest mean value, the temperature fluctuated between 5 and 69°C over a few minutes. Likewise, at the Elsa PP-Hot3 vent, temperature variations could reach 45°C whereas they did not exceed 27°C for the Parigo site samples. As discussed in Le Bris & Gaill (Reference Le Bris and Gaill2007), such dispersion of temperature data can be easily explained by, both, turbulent mixing of hot fluid and cold seawater above the openings of Alvinella tubes and weak instabilities in the position of the probe within the steep gradients characterizing these habitats. Note that temperature variations recorded in the present study were independent of time series duration (R2 = 0.0629; N = 14; P = 0.3872).

Table 2. Temperature (mean±SD) and chemical parameters (mean) of the different samples from the 13°N/EPR hydrothermal vent field. Range values are given in parentheses. For each sample, temperature was measured at different sampling points (see Table 1) while chemical parameters were calculated from geochemical modelling. See text for explanation. nd, not determined; *indicates samples collected in Riftia clumps.

Estimated mean pH corresponding to samples were lower than regular seawater pH with acidic to slightly acidic values (i.e. 6.0–6.6) at the Genesis PP12 and Elsa PP-Hot3 vents and near-neutral to alkaline values (i.e.7.4–7.8) at the Parigo site and the Elsa PP-Ph01 vent (Table 2). Estimated mean sulphide concentrations ranged from 164 to 406 µmol l−1 with the highest values corresponding to samples of Parigo PP-Ph05(2), Genesis PP12 and Elsa PP-Hot3 vents. Reflecting temperature variability, large sulphide ranges were defined for each sample (e.g. ranging between 24 and 927 μmol l−1 for the sample E3-b). Iron concentrations greatly differed among sites with a large contrast between the Genesis–Parigo sites and the Elsa site. While iron was strongly depleted in the habitat sampled at Genesis (below the level of detection of our in situ analysis method) and displayed only moderate concentration in the environment of Parigo (less than 29 µmol l−1), this compound reached much higher concentrations at the Elsa PP-Hot 3 vent (between 270 and 339 µmol l−1). At Elsa PP-Ph01, the estimated average concentration revealed to be low but the large range of iron content indicated that it could be found punctually at high concentrations. Rather than an iron-depleted fluid such as observed at Genesis, the low mean iron level in this case reflected a weak contribution of the hydrothermal fluid to the environment, on average, as indicated by a low mean temperature.

As compared to the large variability of physico-chemical conditions encountered when considering the whole architecture of the alvinellid aggregation (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005), the variability of physico-chemical parameters was quite low within a vent at the surface of the alvinellid zone. Conversely, substantial variability in habitat physico-chemical conditions could be observed among different vents within a site. As an example, two types of habitat were considered at the Parigo and Elsa sites: one with lower temperature, near neutral pH and moderate sulphide concentrations (PP-Ph05-1 and PP-Ph01) versus one with higher temperature, slightly acidic pH and higher sulphide concentrations (PP-Ph05-2 and PP-Hot3). Major differences among sites were due to variations in iron concentrations.

In Riftia clumps, if the sample from Genesis Hot 2 displayed the lowest mean value of temperature, the thermal range in sample P1-e from the Parigo site did not differ from neighbouring samples collected in Alvinella colonies on the same vent (Table 2). According to our model assuming that temperature correlation with chemical parameters is conserved at site scale, similar chemical features for these two environments at Parigo were inferred from similar temperatures.

Faunal composition

A total of 11 gastropod species were identified in the 14 samples (Table 3). Five species (i.e. Lepetodrilus elevatus, L. pustulosus, Nodopelta heminoda, N. subnoda and Peltospira operculata) were found in 9 to 13 samples and represented between 87 and 100% of the total number of individuals in each sample. By contrast, only 2 species (i.e. Pachydermia laevis and Hirtopelta hirta) were found in only one sample.

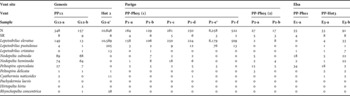

Table 3. Number of individuals (N), species richness (SR) and species-abundance list of gastropods collected in the different samples from the 13°N/EPR hydrothermal vent field. *indicates samples collected in Riftia clumps.

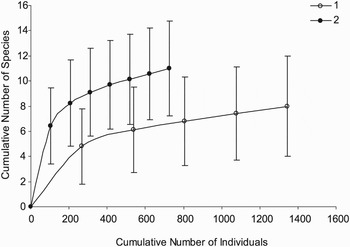

The cluster analysis showing the percentage similarity of faunal composition for each sample is given on Figure 1A. Samples separated into two well-defined faunal groups. The cluster 1 included all the samples from the Parigo PP-Ph05(1) vent as well as the G2-a sample collected in a Riftia clump and exhibited high internal similarity. It was largely dominated by L. elevatus which accounted for more than 80% of individuals. The cluster 2 was composed of samples from Genesis-PP12, Parigo PP-Ph05(2) and Elsa vent sites, which displayed a large proportion of peltospirid gastropods (i.e. P. operculata, N. subnoda and N. heminoda). However, the low internal similarity between samples of this cluster, just over 50%, testified to a high heterogeneity of faunal composition. For example, the samples P2-a, E1-a and E3-a were characterized by a high proportion of P. operculata (54.5 to 61.8% of individuals) and the presence of N. subnoda (15.2 to 32.7% of individuals) while the samples G12-a, G12-b, P2-b and E3-b were mainly composed of a mixture of both species of Nodopelta (23.5 to 84.1% of individuals) and L. elevatus (8.3 to 47.1% of individuals). Species-effort curves suggested that habitats related to group 2, characterized by a large proportion of peltospirids, have higher species richness than habitats related to group 1, largely dominated by L. elevatus (Figure 2). Nevertheless one can note that no species-effort curve had reached the asymptote.

Fig. 1. Bray–Curtis similarity among the 14 gastropod samples collected in Alvinella colonies and Riftia clumps at 13°N/EPR hydrothermal vent field. Abundance data were standardized to number of individuals in the sample and square-root transformed. (A) Group average sorting dendrogram; (B) non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). Relationships between the 2 major faunal groups identified by the cluster analysis and physico-chemical variables were reported on the NMDS plots. Size of the bubbles is proportional to the value of the physico-chemical parameters for each sample (see Table 2). *on the group average sorting dendrogram indicates samples collected in Riftia clumps.

Fig. 2. Species-effort curves with 95% confidence intervals generated with the EstimateS v.7.5. software from species abundance data of each faunal assemblage identified by the group average sorting dendrogram. These curves provide an estimate of expected species richness for random subsets sampled in the total species pool of a faunal assemblage.

The BIO-ENV procedure provided the best matching of faunal groups to physico-chemical patterns by considering combinations of environmental variables at increasing levels of complexity. When only one variable was considered, mean sulphide concentration appeared to be the most explanatory variable with a ρw of 0.373. The next best variables were mean pH (ρw = 0.358) and maximal temperature (ρw = 0.233). The overall optimum combination involved these 3 variables (ρw = 0.401). Superimposing these environmental data onto the NMDS performed on faunal composition highlighted the influence of these physico-chemical variables in shaping gastropod communities (Figure 1B). Cluster 1 was associated with lower sulphide concentrations and maximal temperatures, and a higher pH. In contrast, cluster 2 tended to be generally associated with higher maximal temperatures and sulphide concentrations and a lower pH. Nevertheless, a large disparity in physico-chemical conditions occurred within this cluster. As an example, the highest and the lowest mean sulphide concentrations reported in the data set (406 and 53 µmol l−1) were observed for two samples from this cluster, E3-a and E1-a respectively (Table 2).

Biology of Lepetodrilus elevatus

The population structure of L. elevatus was analysed on only 8 samples from 3 vents (i.e. Parigo PP-Ph05(1), Genesis PP12, Genesis Hot2) for which individuals were in sufficient number (Figure 3). The curvilinear shell length ranged from 1.09 to 11.27 mm. Size–frequency distributions were highly variable among samples (Kruskal–Wallis H statistic = 430.61, df = 7, P < 10−3). Multiple range tests using the Dunn–Nemenyi procedure identified 4 groups of samples: (i) G12-a; (ii) G2-a; (iii) P1-b, P1-c, P1-d and P1-f; and (iv) P1-a and P1-e. These latter samples differed from the other Parigo samples by a higher abundance of larger individuals (>7 mm). Furthermore, the G12-a sample was distinguishable from other samples by a dominance of small individuals. The proportion of individuals <5 mm reached 85.8 % in G12-a while it varied between 14.7 and 48.6% in other samples.

Fig. 3. Size–frequency distributions of the curvilinear shell length of Lepetodrilus elevatus for different samples collected in Alvinella colonies and Riftia clumps from the 13°N/EPR hydrothermal vent field. N, number of measured individuals; *indicates samples collected in Riftia clumps.

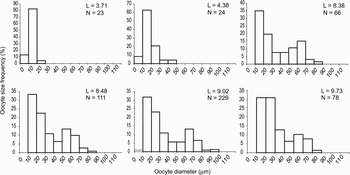

For all samples the sex-ratio did not differ significantly from the theoretical balanced 1:1 sex-ratio (χ2 goodness-of-fit test; P >0.05). In the gonad, oocyte diameter ranged from 7.3 to 113.9 µm. Two types of germinal cells were observed: (1) small oogonies and previtellogenic oocytes with a large nucleus, a basophilic cytoplasm and a size <40 µm; and (2) vitellogenic oocytes with a large cytoplasm containing yolk granules and a size >40 µm. Most females exhibited a common pattern in oocyte size distributions with a first major peak of oogonia and previtellogenic oocytes and a second minor peak of vitellogenic oocytes (Figure 4). However, oocyte size–frequency distributions differed significantly at the different spatial scales analysed in this study, suggesting asynchronous reproduction among vents and among females within each vent (Figure 5). Among vents, significant differences in size distributions (Kruskal–Wallis H statistic = 246.28, df = 4, P < 10−3) were mainly due to the individuals from the Genesis PP12 vent which exhibited a smaller mean oocyte size than individuals from the other vents (P < 0.05). This result could be explained by the animal size as the 7 individuals from the Genesis PP12 vent were the smallest individuals analysed in this study (i.e. curvilinear shell length ranging from 3.71 to 5.48 µm) and were mainly characterized by a large dominance of previtellogenic oocytes (Figure 4). Indeed, while there was a significant correlation between the curvilinear shell length and the percentage of vitellogenic oocytes per female when all females were considered (R2 = 0.2564, N = 72, P < 10−3), the correlation became non-significant when the individuals from the Genesis PP12 vent site were removed (R2 = 0.0578, N = 65, P = 0.054). Significant differences in oocyte size distributions were also reported among samples within a vent on the example of Parigo PP-Ph05(1) vent (Kruskal–Wallis H statistic = 62.79, df = 5, P < 10−3) and among females within a sample (sample P1-a: Kruskal–Wallis H statistic = 70.97, df = 10, P < 10−3; sample P1-d: Kruskal–Wallis H statistic = 51.61, df = 9, P < 10−3; sample P1-f: Kruskal–Wallis H statistic = 150.36, df = 10, P < 10−3). However, multiple range tests using the Dunn–Nemenyi procedure indicated that 54 to 60% of the females examined in each sample showed no significant difference in oocyte size–frequency distributions.

Fig. 4. Oocyte size–frequency distributions for Lepetodrilus elevatus from different vents and sizes. L, curvilinear shell length; N, number of measured oocytes.

Fig. 5. Mean oocyte Feret diameter (±95% confidence limits) (μm) of Lepetodrilus elevatus at different spatial scales. (A) Between vents; (B) between samples from the Parigo PP-Ph05(1) vent; (C, D & E) between females from samples P1-a, P1-d and P1-f respectively. Numbers near the mean give the number of individuals and measured oocytes respectively used to calculate mean oocyte diameter. Similar letters indicate no statistical difference among oocyte size distributions (P > 0.05) calculated from the multiple range test using the Dunn–Nemenyi procedure. *indicates samples collected in Riftia clumps.

DISCUSSION

At the scale of a biological sample, a large variability of physico-chemical conditions was reported, consistently with the steep chemical gradients already described over scales of centimetres and seconds to hours in hydrothermal habitats (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Childress, Hessler, Sakamoto-Arnold and Beehler1988; Chevaldonné et al., Reference Chevaldonné, Desbruyères and Le Haître1991; Sarradin et al., Reference Sarradin, Caprais, Briand, Gaill, Shillito and Desbruyères1998; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005). From this observation it was suggested that animals would occasionally deal with high temperature, high sulphide concentrations and low pH. However, the estimated amplitude of thermal and chemical ranges at the surface of the alvinellid colony where the gastropods are located are still substantially lower than depicted for the general Alvinella pompejana environment (Sarradin et al., Reference Sarradin, Caprais, Briand, Gaill, Shillito and Desbruyères1998; Luther et al., Reference Luther, Rozan, Martial, Nuzzio, Di Meo, Shank, Lutz and Cary2001; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003, 2005). This is consistent with the synthesis of temperature ranges reported for this environment in Le Bris & Gaill (Reference Le Bris and Gaill2007) that underlined much milder conditions at the surface of the colony than among the tubes of Alvinella spp. that composed the interface between the chimney wall and seawater. Still, close-up video recordings confirmed that organisms sometimes bathed in turbulent shimmering water, where they can alternately experience, in few seconds, conditions that only slightly depart from seawater and conditions with a more significant hydrothermal influence. Considering the similar temperature ranges, no large variation in the range of physico-chemical conditions was expected among samples in the Alvinella habitat, within a single vent, suggesting that the habitat sampled was quite homogeneous. Within a single Alvinella aggregation, Le Bris et al. (Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005) highlighted substantial discrepancies at small-scale but they were mostly reported when comparing different microenvironments in the matrix surrounding Alvinella tubes and the interior of the tubes. Comparatively, measurements from the water layer overlying the surface of the colony, where gastropods live, appear more consistent with the conservative mixing model, at least in the vicinity of venting sources (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005). Larger environmental differences were documented among samples from different vents within a site. Thus, at the Parigo and Elsa sites, one vent was characterized by lower temperature and sulphide concentrations, and higher pH than the other one. Among sites, the most significant result in terms of spatial variations in habitat chemistry regarded iron which distinguished the iron-rich Elsa site from the iron-depleted Genesis and Parigo sites. Such variations in the Fe:S ratio which mainly depends on the end-member vent fluid composition have been already highlighted for the 13°N/EPR hydrothermal vent field (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003, Le Bris & Gaill, Reference Le Bris and Gaill2007).

While thermal conditions are commonly reported to be strongly contrasted in different hydrothermal habitats (Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998; Luther et al., Reference Luther, Rozan, Martial, Nuzzio, Di Meo, Shank, Lutz and Cary2001; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003), no difference in temperature was observed between the sole Riftia-dominated sample and Alvinella-dominated samples at Parigo PP-Ph05(1) vent. Again, this is not so surprising considering that the surface of Alvinella tube aggregation displays a much more limited thermal range than the bulk of the colony. The chemical conditions could however be much more contrasted than assumed here between these habitats as the consistency of the temperature correlation with sulphide, iron and pH may only be valid when comparing alvinellid environments. Large discrepancies in the sulphide–temperature correlation have been observed between alvinellid and Riftia aggregations located less than 1 m apart (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Govenar, Le Gall and Fisher2006a).

Similarly to environmental conditions, gastropod community structure was mainly similar among samples from a single vent but variable among vents and sites, being either dominated by peltospirids (i.e. Peltospira operculata, Nodopelta heminoda and N. subnoda) at Elsa, Genesis-PP12 and Parigo PP-Ph05(2) or lepetodrilids (i.e. Lepetodrilus elevatus) at Parigo PP-Ph05(1) and Genesis-Hot 2. Nevertheless, within the peltospirids-dominated vents, the relative proportion of P. operculata and Nodopelta spp. as well as the abundance of L. elevatus could be highly variable among samples. While numerous studies have already highlighted changes in habitat temperature and chemistry as primary driving forces for changes in hydrothermal community composition at the site or vent field-scale (Sarrazin et al., Reference Sarrazin, Robigou, Juniper and Delaney1997; Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998; Sarrazin & Juniper, Reference Sarrazin and Juniper1999), our study showed that for gastropods the most explanatory environmental variable considered alone was the mean sulphide concentration followed by the mean pH and maximal temperature. If the best matching of faunal composition to environment involved these 3 physico-chemical variables, the addition of pH and temperature improved only slightly the link between environmental data and gastropod distribution patterns.

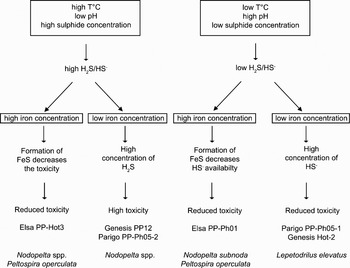

The role of these 3 environmental variables on species distribution may be related to physiological adaptations and nutritional requirements as generally suggested for hydrothermal fauna. Sulphide is thought to be the primary energy source for chemosynthetic bacterial primary production in these environments (Childress & Fisher, Reference Childress and Fisher1992) but is also known to be deleterious to all aerobic organisms (Visman, Reference Visman1991). Hydrothermal animals thus have to deal with conflicting constraints related to this compound. Likewise, temperature can act directly on vent fauna according to their thermal tolerance. Lee (Reference Lee2003) experimentally showed that Lepetodrilus fucensis and Depressigyra globulus, 2 common gastropods in alvinellid colonies at the Juan de Fuca Ridge (north-east Pacific), could not stand short exposure to temperature exceeding 30–35°C and 35–40°C respectively. Moreover, Bates et al. (Reference Bates, Tunnicliffe and Lee2005) suggested from field observations and experiments that temperature had a significant influence on the distribution patterns of 3 gastropod species (i.e. L. fucensis, D. globulus and Provanna variabilis) from the Juan de Fuca Ridge. While the former two species occupied near-vent habitats with a temperature between 5 and 13°C, the latter one was reported in areas with significantly lower temperature from 4 to 11°C. Although the direct influence of pH on vent fauna physiology is less documented, this parameter is highly relevant to assess the impact of habitat condition on vent communities as it mainly affects the distribution of sulphide in different chemical forms of contrasted biological effects (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003). The sulphide toxicity and bioavailability mostly depends on the relative proportions of the free sulphide and iron-associated forms (Luther et al., Reference Luther, Rozan, Martial, Nuzzio, Di Meo, Shank, Lutz and Cary2001; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003). According to their iron concentration and pH range, the quality of the habitats sampled in this study could be classified in terms of relative toxicity. At low to negligible iron concentrations, free sulphide forms (H2S and HS−) constitute the dominant sulphide species. The acidity constant (pKa) of H2S being close to 7, sulphide should be mostly present as the most toxic neutral species, H2S, in the higher temperature and more acidic habitat (i.e. Genesis PP-12) while it would be mostly present as the less toxic anionic species, HS−, in the lower temperature and less acidic habitat (i.e. Parigo PP-Ph05(1)). Conversely, the high iron concentrations observed at Elsa site would decrease sulphide environmental toxicity, even in this acidic habitat by the formation of FeS.

A first assumption to explain the differential distribution between peltospirids and lepetodrilids species at 13°N could be their different thermal tolerance. Such assumption is in accordance with recent observations performed at 9°50′N which showed different thermal boundaries between lepetodrilids mainly associated with the vestimentiferan habitat and peltospirids confined to alvinellids habitat (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Mullineaux and Tyler2007). However, if L. elevatus was abundant (more than 50% of individuals) in samples with maximal temperature not exceeding 29°C, it was also reported in samples where maximal temperature reached 69°C, suggesting that this species could be subject to short-term exposures to high temperature. The better tolerance of Nodopelta spp. and P. operculata to sulphide toxicity, as compared to L. elevatus might provide another explanation for the distribution observed. In this case, the former species will be favoured in habitats characterized by higher sulphide concentrations and temperature, and more acidic conditions. However, gastropod community structure in the presumably more toxic environment, Genesis-PP12, did not highly differ from the structure reported in samples from sulphide-rich but less toxic environment such as Elsa PP-Hot3 and Parigo PP-Ph05(2) vents. Govenar et al. (Reference Govenar, Le Bris, Gollner, Glanville, Aperghis, Hourdez and Fisher2005) also highlighted high similarity in epifaunal community structure including lepetodrilids in Riftia pachyptila clumps of contrasted sulphide and iron ranges.

Despite heuristic and conceptual interest, the BIO-ENV procedure mainly remains an exploratory tool to assess the relationship between multivariate community structure and environmental variables (Clarke & Warwick, Reference Clarke and Warwick2001). Even if conclusions cannot be supported by significance tests given the lack of model assumptions underlying the procedure, the low values of ρw ranging from 0.373 to 0.401 suggested that chemical variables as measured in this study only poorly explained gastropod distribution patterns. Two non-exclusive hypotheses could be proposed: (1) limitations in the ability to discriminate habitats in terms of physico-chemical conditions experienced by organisms; and (2) a more complex interplay between abiotic factors impact and biological interactions.

Chemical parameters were not measured simultaneously with temperature prior to animal collections, but were extrapolated from temperature measurements assuming a conservative behaviour in the mixing interface between the source fluid and ambient seawater at the scale of a single vent edifice. These limitations may have reduced the validity of our extrapolations as some discrepancies in the temperature relationship with chemical factors have been reported at site scale for various types of hydrothermal habitats (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Childress, Hessler, Sakamoto-Arnold and Beehler1988; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin, Birot and Alayse-Danet2000, 2005, 2006b). Indeed, several processes can alter the relationships between temperature and chemical parameters including biological consumption of sulphides in mussel beds and Riftia clumps (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Childress, Beehler and Sakamoto-Arnold1994; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Rodier, Sarradin and Le Gall2006b) and conductive thermal exchanges in Alvinella colonies (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005). Over similar temperature ranges, highly different sulphide contents may indeed characterize adjacent Riftia clumps and Alvinella colonies on a single chimney (Luther et al., Reference Luther, Rozan, Martial, Nuzzio, Di Meo, Shank, Lutz and Cary2001; Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003, 2006b), and the lack of chemical differences supposed at Parigo PP-Ph05(1) vent between both habitats may be erroneous in the present study. In the Alvinella habitat, if temperature is not a relevant tracer of fluid mixing, the processes involved vary among distinct micro-environments (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005). In the inner-tube environment, the unexpected combination of a high temperature and a high pH is mostly explained by a conductive heating of a seawater-dominated mix through the tube walls whereas, in the medium surrounding the tubes, a conductive cooling of the warm and low pH fluid occurs when it passes through the thickness of the worm colony. By contrast, at the surface of the colonies, a detailed analysis of the relationship between temperature and pH, considered as a reliable tracer of the vent fluid contribution, suggested that the conservative mixing hypothesis is acceptable in a first approximation (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005). For this peculiar environment on which most of the present study focused, the use of empirical correlations between temperature and chemical parameters could be assumed to have greatly improved the general characterization of habitats, as compared to those only based on temperature measurements. On the other hand, even if close-up video imagery was used to ensure that ranges and mean values described the environment of gastropods at the surface of Alvinella colonies, the measurement strategy used for this study did not allow us to characterize fine-scale temperature variability in micro-niches at the individual scale (i.e. cm) as reported in Di Meo-Savoie et al. (2004), Bates et al. (Reference Bates, Tunnicliffe and Lee2005) and Le Bris et al. (Reference Le Bris, Zbinden and Gaill2005). Indeed, some hydrothermal gastropods may occupy microhabitats that differ from the general surrounding physico-chemical environment at the surface of Alvinella colonies (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Mullineaux and Tyler2007).

A better assessment of temporal variability would be also required to appreciate the factors that could influence species distribution. Temperature in vent habitats fluctuates at different time scales, in response to turbulent mixing of hydrothermal fluid and ambient seawater which produces rapid pulsations and brief spikes at second to minute scales, to tidal motion at hour to day scales, and to variations in bottom currents and hydrothermal emissions at longer scale (Chevaldonné et al., Reference Chevaldonné, Desbruyères and Le Haître1991; Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998; Tivey et al., Reference Tivey, Bradleyb, Joyce and Kadkod2002). In the present study, time series measurements of temperature performed only at short timescale, from about 1 to 50 minutes, could imperfectly describe thermal conditions encountered by organisms. A continuous record of temperature over a week on an A. pompejana colony at Elsa PP-Hot3 vent showed that temperature mostly ranged between 10 and 20°C but could display peaks of temperature reaching 25–27°C for a duration of several hours (Pradillon et al., Reference Pradillon, Le Bris, Shillito, Young and Gaill2005a). Nevertheless, measurements carried out at different dates at Parigo PP-Ph05(1) vent in the present study provided comparable range of temperature variations and no significant relationship occurred between temperature fluctuations and time series duration, suggesting some stability over time. Likewise, the Fe:S ratio in end-member fluid which is largely modulated by subsurface processes, was also reported to be highly variable in time in relation to variations in fluid emission, mainly at monthly to yearly scales (Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998; Von Damm & Lilley, Reference Von Damm, Lilley, Wilcock, DeLong, Kelley, Baross and Cary2004). The distinction between the iron-rich Elsa site and the iron-depleted Genesis and Parigo sites depicted in the present study has already been mentioned by Le Bris et al. (Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003) from measurements performed 3 years before (Le Bris et al., Reference Le Bris, Sarradin and Caprais2003). Thus, for mobile species such as gastropods which can actively respond to long-term variations in the physico-chemical environment, we can expect that our data are sufficiently representative of the global range of environmental parameters actually experienced by the organisms at scales ranging at least from minutes to weeks.

In addition to the organism's physiological tolerances to the physico-chemical environment, the gastropod community structure could also rely on biological interactions between species, including predation and competition for a limiting food and space resource. Over a limited range of environmental conditions, the relative dominance of one species would in part depend on its abilities to outcompete other species according to its reproductive and growth potential. In this context, the most striking result of the present study is the lower species richness in the lower temperature and sulphide concentrations vent (Parigo PP-Ph05(1)), because of the overwhelming dominance of L. elevatus in Alvinella-dominated as well as Riftia-dominated habitats. In the Riftia habitat, manipulative field-experiments already showed that L. elevatus could strongly modify the community structure, and exert negative influences on sessile and mobile colonists by physically dislodging their recruits (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Peterson, Mullineaux, Fisher, Mills, Sancho, Johnson and Lenihan2002; Mullineaux et al., Reference Mullineaux, Peterson, Micheli and Mills2003). Different results on the demography and reproduction of L. elevatus in relation to physico-chemical conditions may support the hypothesis that this species might well develop in a less extreme environment and influence peltospirid populations.

The significant variation of size–frequency distributions of L. elevatus among vents could result from numerous factors including: (i) sampling bias related to small sample size; (ii) spatial and temporal variations in larval supply (Metaxas, Reference Metaxas2004); (iii) site- and size-specific growth rate (Mullineaux et al., Reference Mullineaux, Mills and Goldman1998); or (iv) site-and size-specific mortality rate. Nevertheless, the main difference was due to the only sample collected in a high temperature and high sulphide toxicity environment at Genesis PP12 vent which differed significantly from all other samples by a very small proportion of large individuals. Furthermore, Mullineaux et al. (Reference Mullineaux, Mills and Goldman1998) or Sadosky et al. (Reference Sadosky, Thiébaut, Jollivet and Shillito2002) have shown that recruitment of this species is generally coherent at the vent field scale. Thus, even if the factors mentioned above cannot be ruled out, this pattern may suggest that physico-chemical conditions could alter the demography of L. elevatus. The very high proportion of small individuals at Genesis PP12 vent may result from broader physiological tolerances and higher survivorship of juveniles than adults in marginal habitat as already reported by Mullineaux et al. (Reference Mullineaux, Mills and Goldman1998). In terms of reproduction, heterogeneous size–frequency distributions of oocytes among mature females confirmed that gametogenesis was asynchronous at vent as well as at sample scale (Pendlebury, Reference Pendlebury2004), and seemed independent of the physico-chemical environment. However, the positive relationship between the animal size and its sexual maturity, defined as the proportion of vitellogenic oocytes, indicated that most individuals from the Genesis PP12 vent were immature and did not participate in the local reproductive effort. Along the Juan de Fuca Ridge, Kelly & Metaxas (Reference Kelly and Metaxas2007) observed that L. fucensis gametogenic maturity did not vary between actively venting habitats but was significantly lower in senescent areas according to variation in energy supply. Here, while the environment at the Genesis site may constitute the upper limit for L. elevatus to develop, the cooler habitats seem to be optimal, so that the females can maximize their reproductive output. While the lack of replicate in the most toxic habitat impedes a global statistical analysis over the range of physico-chemical conditions encountered in the present study, those results suggest that L. elevatus may be highly competitive in the lower temperature and less toxic environmental conditions. Even if peltospirid gastropods may probably survive in lower temperature, as at Elsa PP-Ph01 vent, habitat colonization by L. elevatus could exclude them since environmental conditions are favourable to the development of this latter species in Alvinella- as well as in Riftia-dominated habitat.

In describing the different hydrothermal communities structure and diversity patterns, only a few studies to date have included locally defined chemical parameters of ecological relevance to identify processes governing the observed patterns (Sarrazin et al., Reference Sarrazin, Robigou, Juniper and Delaney1997; Shank et al., Reference Shank, Fornari, Von Damm, Lilley, Haymon and Lutz1998; Sarrazin & Juniper, Reference Sarrazin and Juniper1999; Govenar et al., Reference Govenar, Le Bris, Gollner, Glanville, Aperghis, Hourdez and Fisher2005). Despite the inabilities to actually perform quantitative samples in the high-temperature hydrothermal environment, the present study reported for the first time the influence of environmental chemistry on epifaunal assemblages in different alvinellid colonies at vents along the East Pacific Rise, focusing on gastropods. The main physico-chemical parameters governing the habitat quality and consequently the community structure were, in a decreasing order of importance, mean sulphide concentration, mean pH and maximal temperature. Peltospirid gastropods (i.e. Nodopelta spp. and P. operculata) were then dominant in the more acidic, higher temperature and richer sulphide vents than lepetodrilid gastropods (i.e. Lepetodrilus elevatus) (Figure 6). Although this pattern could result from different specific physiological tolerances and nutritional requirements, the occurrence of all common species over a wide range of physico-chemical conditions as well as the low correlation between biological community structure and physico-chemical parameters suggests that other factors may be responsible for community composition in Alvinella colonies. In particular, the lower richness resulting from the dominance of L. elevatus in the lower temperature and sulphide concentrations habitat suggests that the latter species may outcompete other species in such environmental conditions. Thus, in these conditions, gastropod community structure did not differ between Alvinella colonies and Riftia clumps. If field samples remain essential to describe patterns and make assumptions about processes involved, further experimental manipulative shipboard and field studies should be necessary to identify the ways of biogeochemical processes on community structure and separate unambiguously the relative contributions of physiological tolerance, nutritional requirement and biological interactions.

Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the influence of physico-chemical variables on the gastropod community structure for the different vents from the 13°N/EPR hydrothermal vent field. Toxicity of the different habitats was determined from the interactions between total sulphide concentrations, pH, and iron concentrations. For each habitat, dominant gastropod species are indicated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the captain and crew of the NO ‘L'Atalante’ and the team of the ROV ‘Victor 6000’ for their helpful collaboration at sea. We also acknowledge P.-M. Sarradin, C. Le Divenah, C. Le Gall and P. Rodier for their support in the implementation of in situ chemical analysis and collection devices. We are grateful to S. Hourdez for the English proofreading and to two anonymous referees for their valuable comments on a first draft of the manuscript. This work was financially supported by Ifremer and the French Dorsales program (INSU, Ifremer, CNRS). It is also a contribution to the GDR Ecchis and the ANR ‘Deep Oases’ project (ANR-06-BDIV-005).