INTRODUCTION

The land crab Cardisoma guanhumi Latreille, 1828 (Decapoda: Gecarcinidae) has nocturnal habits (Melo, Reference Melo1996), with a circumequatorial distribution in the western Atlantic occurring in all the estuaries from Caribbean, Central America and South America (Burggren & McMahon, Reference Burggren and McMahon1988), while in the United States, its distribution is limited only to the Gulf of Mexico and Florida (Hill, Reference Hill2001). The extent of its distribution is limited by temperature, the larvae survival is compromised in areas where the temperature falls below 20°C (Hill, Reference Hill2001).

Cardisoma guanhumi is an important fishery resource from Florida to Brazil (Bozada & Chávez, Reference Bozada, Chávez, Bozada and Páez1986; Shinozaki-Mendes, 2011a), including the Caribbean and Bahamas (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2001), Puerto Rico (Feliciano, Reference Feliciano1962) and Venezuela (Taissoun, Reference Taissoun1974). In Brazil it has a high commercial value, costing up to U$10 (an adult male specimen) in some restaurants (personal observation), thus, it is a fishery resource of great socio-economic importance. One of the important parameters to ensure the sustainability of any exploited fish stocks is the size of first sexual maturity in which 50% of the population is able to reproduce. Based on that, it is common to establish, the minimum catch size, in order to ensure the proper reproduction and subsequent recruitment.

The proportion of germ cells found in each ovary or testis, in addition to the somatic components, determines the stages of body development, providing understanding of the reproductive cycle of the species (Shinozaki-Mendes et al., 2011b). Thus, the study of gonadal maturation, based on histological analysis of gonads is an important method for determining stages of gonadal development and maturity.

The studies on the maturity of this species, which is suffering greatly from anthropogenic impacts, both by the excessive capture of crabs, as well as the destruction of their ecosystems, become extremely relevant since the results can be used to protect the population, which ultimately aims to ensure the sustainability of its exploitation. This species has been listed in the ‘National list of species of aquatic invertebrates and fish over exploited or threatened with overexploitation’, published by the Brazilian Ministry of Environment (MMA–IBAMA, on Normative No. 5, 21 May 2004).

Despite its great ecological and socio-economic relevance, few studies have been carried out on the reproduction of C. guanhumi. In south-eastern Brazil, Silva & Oshiro (Reference Silva and Oshiro2002) evaluated the reproductive aspects of C. guanhumi based on macroscopic analysis of female gonads, while in north-eastern Brazil, Botelho et al. (Reference Botelho, Santos and Souza2001) analysed population aspects and Abrunhosa et al. (Reference Abrunhosa, Mendes, Lima, Yamamoto and Ogawa2000) developed the cultivation from the egg to juvenile. Gifford (Reference Gifford1962) studied the general biology of C. guanhumi, in Florida, United States, and Taissoun (Reference Taissoun1974) highlighted general aspects of the species in Venezuela. Giménez & Acevedo (Reference Giménez and Acevedo1991), in turn, studied the morphometric relationships and size at first maturity in Cuba, while Rivera (Reference Rivera2005) conducted tests in terms of the species as a fishing resource in Mexico.

In this study, the reproductive cycle of C. guanhumi, is described from the analysis carried out based on seasonal variation of gonadal maturation stages, determining the size of the first morphological and physiological maturity for both sexes; as well studies on some aspects of sexual dimorphism in the population were also carried out.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

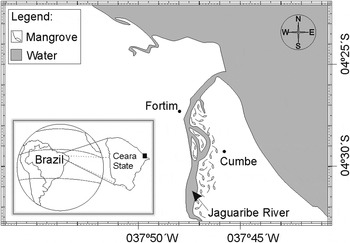

The individuals were sampled in the mangrove estuary of the Jaguaribe River (04°26′S to 04°32′S and 037°46′W to 037°48′W), on the Cumbe community, east coast of Ceara State, north-eastern Brazil (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Geographical location (east coast of Ceara State, north-eastern Brazil) of the sampling area of Cardisoma guanhumi.

In the period between December 2006 and November 2007, 353 individuals were sampled, totalling to an average monthly sampling size of 30 specimens. All the animals were caught with artisanal traps, made by the local collectors. The specimens of Cardisoma guanhumi build individual burrows to inhabit, called holes. The choice of holes in which the traps were left was randomized, with no preference for burrows entrance with greater or smaller diameter.

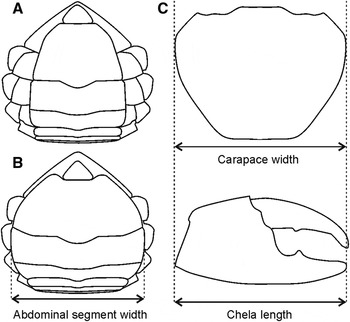

Prior to dissection, the specimens were refrigerated to −10°C (but not frozen) until immobilization (~15 minutes). The individuals were measured in carapace width (CW), length (ML) of the major chela (the first right or left pereiopod) and width of the 5th (W5) abdominal segment using a caliper (precision: 0.01 cm) (Figure 2). The individuals which had the smaller size chela, indicating the regeneration process, were excluded from the analysis.

Fig. 2. Schematic drawing of the abdomen of immature (A) and mature (B) females indicating the width of 5th abdominal segment and the measures of the carapace width and chela length for the classifications of males of Cardisoma guanhumi.

Although not mentioned in the literature, after several visual observations, the following classification for males and females was applied: juvenile female—the abdomen not covering all thoracic esternites; adult female—abdomen covering all thoracic esternites (at the basis of coxa); juvenile male—the chela length is inferior to the carapace width; and adult male—the chela length exceeds the carapace width (Figure 2).

The animals were dissected, slicing up the shell laterally, to allow the removal of reproductive tract. The material collected was fixed in Davidson's solution for 24 hours before transferring and being kept in a 70% alcohol solution. Fragments of the reproductive tract were then dehydrated in increasing alcohol series, diaphanized in xylene and impregnated and included in paraffin at 60°C. Each block containing biological material was serial sectioned at 5 µm, with the slides being stained by the methods of Alcian Blue/Periodic Acid Schiff (adapted from Junqueira & Junqueira, Reference Junqueira and Junqueira1983) and Gomori's trichrome (adapted from Tolosa et al. Reference Tolosa, Rodrigues, Behemer and Freitas-Neto2003).

The microscopic analyses of the gonads stages were classified following the scale of gonadal maturation of C. guanhumi as proposed by Shinozaki-Mendes et al. (Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011a, Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva, Sousa and Hazin2011b) for males and females (see Table 1).

Table 1. Main characteristics of the classification scale of maturation used in this study, suggested by Shinozaki-Mendes et al. (Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva and Hazin2011a, Reference Shinozaki-Mendes, Silva, Sousa and Hazinb), based on the description of macro and microscopic characteristics of the gonads.

The absolute frequency of males and females was analysed for the CW classes and monthly. To examine whether the proportion between males and females showed statistical differences, the Chi-square test (P < 0.05) (Zar, Reference Zar1984) was used for the period of 12 consecutive months.

To determine the size of the first gonadal and morphometric maturations, the size in which 50% of individuals are able to reproduce, the percentage of individuals which has already begun the reproductive cycle (M) for each class of the CW, was estimated through the logistic model: M = 1/(1 + exp(β0+ β1CW)) (see Mendes, Reference Mendes1999). Also the size in which the pubertal moult occurs was determined by the inflexion point on the curve in the CW × W5 and CW × ML relation to females and males, respectively. These measures were chosen because they showed greater variation in growth for each sex. The ‘w’ statistical test (P < 0.05) was used to compare the models. This test uses the maximum likelihood and the Chi-square distribution (Mendes, Reference Mendes1999), and is based on comparison between linear and angular coefficients of the models.

To correlate the possible influences of abiotic factors during the reproductive period, pluviometry data were obtained from the Cearense Foundation of Meteorology and Water Management (FUNCEME, 2008) for the period between December 2006 and November 2007 at the meteorological station near the collection site.

RESULTS

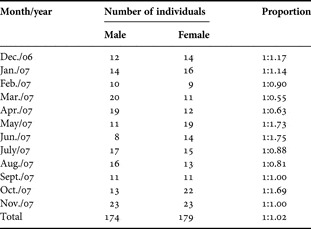

From the 353 Cardisoma guanhumi specimens examined, 179 were females, and 174 were males. The monthly sex-ratio varied from 1:0.55 to 1:1.75 (male:female) (Table 2), with average proportion of 1:1.02. There were no statistically significant differences between the number of males and females (P ≥ 0.05) along the different months, indicating there is no seasonality in the proportion of individuals of different sexes. The CW of the females ranged from 4.34 to 8.56 cm with a modal class between 5.0 and 7.0 cm. Males showed greater width, ranging from 2.84 to 9.22 cm with a mode between 5.0 and 6.5 cm (Figure 3). Note that the smallest and largest classes showed the predominance of males.

Fig. 3. Distribution of absolute frequency of carapace width (CW) for males (in black) and females (in grey) of Cardisoma guanhumi caught between December 2006 and November 2007 in north-eastern Brazil. The values of CW indicate the initial size of the class.

Table 2. Number of individuals of Cardisoma guanhumi monthly sampled in the period between December 2006 and November 2007 in north-eastern Brazil.

The females were observed into five stages of maturation: immature, maturing, mature, spawning and resting (Figure 4). The distribution of maturational stages during the year (Figure 5) indicates that the period in which female gonad maturation starts is from August to February, with higher frequency of mature females in the months of November and December. Spawning females were frequent from December to March, and in May and July three specimens in this stage were also observed. Ovigerous females were found from November to February (N = 6). The males were classified as immature, maturing or mature (Figure 4). Meanwhile there was no seasonal variation observed in this proportion, all stages being randomly distributed among months.

Fig. 4. Photomicrographs of ovaries (from A to E) and posterior vas deferens (from F to H) of Cardisoma guanhumi in different stages of maturation: (A, F) immature; (B, G) maturing; (C, H) mature; (D) spawning; (E) resting. The white arrows indicate the germinative zone and the black arrows indicate the maturation zone. The short arrows indicate: oogonia (OO); pre-vitellogenic oocytes (PVO); vitellogenic oocytes (VO); mature oocytes (MO); atretic oocytes (AO); follicular cells (FC). The double arrows indicate the spermatophores. Staining: Alcian Blue/Periodic Acid Schiff (A, B, C, D, E, G, H) and Gomori's trichrome (F). Scale bars: 200 µm (A,B, C, D) and 100 µm (E, F, G, H).

Fig. 5. Reproductive cycle of females of Cardisoma guanhumi based on microscopic analysis of gonadal stages: maturing (light grey bars), mature (black bars), spawning (dark grey bars), and resting (white bars), caught between December 2006 and November 2007 in north-eastern Brazil. The upper numbers indicate the sample size.

Pluviometry data in the sampling area (Table 3) indicated that the rainy season starts in December (rainfall of 42 mm) and ends in June (rainfall of 80 mm). The period between July and November shows very much reduced rainfall activity. February to May, when the rains are most intense, also coincides with the decrease of the reproductive period. After June, when the rainy season ends, the female's gonads start to mature.

Table 3. Pluviometry measured in the meteorological station from Aracati region in the period between December 2006 and November 2007 and the average of the last five years. Source: Cearense Foundation of Meteorology and Water Management.

Estimates on the first maturation size (CW50) based on gonadal maturity (physiology) for females and males, respectively, using a logistic model (Table 4) were equal to: CW50 = 5.87 cm and CW50 = 6.22 cm (Figure 6). The size of the first morphometric maturity is based on the abdomen width and chela length. Secondary characters, were also determined based on the logistic model (Figure 6; Table 4), with values of CW50 = 6.12 cm (female) and CW50 = 6.91 cm (male).

Fig. 6. Percentage of individuals of Cardisoma guanhumi able to reproduction per carapace width (CW) classes, caught in the period between December 2006 and November 2007 in north-eastern Brazil. Males in black and females in grey. Continuous line and circles (•) indicate physiological maturity and dotted line and triangles (▴) indicate morphometric maturity. The values of CW indicate the initial size of the class.

Table 4. First maturity size for males and females of Cardisoma guanhumi, based on three different tests: inflexion point on the curve, relevant character and histological analysis. R2, reliability coefficient; MS, first maturity size (carapace width) in cm; J, juvenile; A, adult; W5, width of 5th abdominal segment; CW, carapace width; ML, length of the major chela; M, fraction of individuals able to reproduce.

Once the sigmoid functions for the determination of maturity are estimated, it is possible to estimate the maximum maturation size (CW99) based on the CW, with size of CW99 = 6.91 cm and CW99 = 8.39 cm for females and males, and based on physiology, the CW99 is 7.18 cm and 7.56 cm for females and males, respectively.

Based on the inflexion point on the curve in the CW × W5 and CW × ML relation (Figure 7; Table 4), females presented 6.40 cm as the first maturation size and males presented 7.10 cm indicating the carapace average width in which the pubertal moult would occur.

Fig. 7. Relationship between carapace width (CW) (cm) and the 5th abdominal segment width of females (in grey) and chela length of males (in black) of Cardisoma guanhumi, caught in the period between December 2006 and November 2007 in north-eastern Brazil. Continuous line and circles (•) indicate juvenile and dotted line and triangles (▴) indicate adult, based on the point of maximum inflexion of the curve. The values of CW indicate the initial size of the class.

By analysing the percentage and size-range of individuals in each stage (Table 5), it is noted that the highest percentage of juveniles occurred, during the analysis of the inflection point, achieving 70.4% of females and 84.5% of males. However, the measure individual-to-individual (not the mean value measured in the analysis of the inflection point), indicated that the maturation of the gonads and pubertal moult already occurred in 60.9% of females and 23.0% of males (Table 5).

Table 5. Percentage of individuals and size of the largest and smallest specimens in each stage of maturation, based on three different tests: inflexion point on the curve, relevant character and histological analysis, in females and males of Cardisoma guanhumi sampled in the period between December 2006 and November 2007 in north-eastern Brazil.

CW, carapace width; W5, width of 5th abdominal segment; ML, length of the major chela.

DISCUSSION

A population with balanced annual sex-ratio (1:1) has also been found for Cardisoma guanhumi in Mexico (Bozada & Chávez, Reference Bozada, Chávez, Bozada and Páez1986) and in south-eastern Brazil (Silva & Oshiro, Reference Silva and Oshiro2002). Thus, this feature seems to be common for this species. Masunari et al. (Reference Masunari, Dissenha and Falcão2005) mentioned that this proportion is also observed for species of the genus Uca.

The frequency distribution of the CW indicates that females are more numerous in the most abundant modal class (5.5 to 6.0 cm), not being present in the peripheral classes, while the males are present in all classes. Peripheral classes represented by only one sex may indicate different sizes or rates of recruitment and mortality.

Males of C. guanhumi with larger size in relation to females were also confirmed by Rivera (Reference Rivera2005) for the same species in Cuba (6.5 to 10.5 cm for males, and from 7.0 to 9.0 cm for females), by Bozada & Chávez (Reference Bozada, Chávez, Bozada and Páez1986) for the population in Mexico (2.7 to 10.5 cm for males, and from 4.2 to 7.9 cm for females) and by Silva & Oshiro (Reference Silva and Oshiro2002) in Brazil (2.7 to 8.5 cm for males, and 3.1 to 8.3 for females). Such results suggest that this is an intrinsic feature of populations of C. guanhumi, regardless of location. Although the males and females did not differ in the body size, the males have, statistically, more developed chelae than the females. An accelerated chela growth in mature individuals is associated with territory protection and competition among males for females, which occur for most decapods (Hartnoll, Reference Hartnoll1978).

Under normal circumstances, the males, after reaching maturation, will always have spermatozoa reserves present (Duffy & Thiel, Reference Duffy and Thiel2007). This is the main reason why description of the reproductive cycle is always based on the female's gonadal development, also because the male's maturity is only related to their size, whatever the season. The reproductive period of C. guanhumi based on the female cycle suggested by several authors always occurs in summer and spring and sometimes in the autumn (Table 6).

Table 6. Reproductive period and first maturity size (MS, in cm) of Cardisoma guanhumi found by various authors and in the existing laws (*) of several countries. ♀, females; ♂, males; Sp, spring; S, summer; F, autumn; W, winter.

The termination of reproductive activities in the month in which the rains are most intensified has the benefit of limiting desiccation stress (Hartnoll et al., Reference Hartnoll, Broderick, Godley, Musick, Pearson, Stroud and Saunders2010). Based on our results, we suggest that gonadal development occurs mainly in the dry season; the start of rainfall is a trigger for the end of the maturation and probably the trigger for the beginning of the spawning period.

The first maturity size can vary depending on the geographical distribution of the population (Burggren & McMahon, Reference Burggren and McMahon1988), and the character measured. This feature can vary within the same species as a function of different environmental factors such as salinity, temperature and luminosity (Hines, Reference Hines1989), and can also vary among populations in the same geographical region in response to harvesting, vegetation, leaf-litter standing stock and leaf-litter consumption (Rodríguez-Fourquet & Sabat, Reference Rodríguez-Fourquet and Sabat2009). Thus, it is subjective to compare the size at first maturity between localities due to its peculiarities.

Hartnoll (Reference Hartnoll, Bliss and Abele1982) reported that although the pubertal moults may not coincide with the gonads maturation, it invariably indicates that the individual entered to the maturity stage (size obtained after a certain number of moults) in which sexual activity begins; however, the individual is able to reproduce only after completing all the necessary changes. The gonads maturation seems to occur before the pubertal moult in C. guanhumi, which is reflected in the morphometric measurements. From total females sampled, only 25.7% had immature gonads, while 39.1% were found below the first morphometric maturity size. For this reason, the first maturity size to be considered must be that in which the animal is completely able to reproduce, i.e. when the morphological maturation occurs. The same trend was observed for males.

The small number of ovigerous females obtained in the samples (N = 6, less than 4% of the females collected) may underestimate the spawning period, since females were observed spawning in May and June, although in small numbers. The scarcity of ovigerous females may be linked to the fact that they rarely leave theirs holes, with the purpose of saving energy and avoiding predators (Kennelly & Watkins, Reference Kennelly and Watkins1994), although any decrease in the proportion between males and females during reproduction has not been observed. In addition, Rivera (Reference Rivera2005), while studying the same species in Quintana Roo, observed a segregation of the population, with ovigerous females found in a different mangrove region. Rivera (Reference Rivera2005) also cited a lower density of ovigerous females, having found 5.6 ind./100 m2 (ovigerous) in contrast to 45.8 ind./100 m2 (non-ovigerous). In our study, however, spatial segregation does not seem to occur since males and females were observed in various maturation stages in all the locations sampled.

There are some discrepancies when the non-fishing season established by governmental law and reproductive periods cited by several authors are compared. In south-eastern Brazil, for example, the month that the closed season ends is also the start of the reproductive period (Silva & Oshiro, Reference Silva and Oshiro2002). In north-eastern Brazil, the period suggested by Botelho et al. (Reference Botelho, Santos and Souza2001) to be inserted into the period specified in the legislation, although the ban is unnecessary in March, is further supported based on this research.

In Mexico, the reproductive season coincides with the period suggested by the legislation, according to Rivera (Reference Rivera2005). Meanwhile only half of the period is coincidental in the research of Chavez & Bozada (1986). In Florida, Hill (Reference Hill2001) and Gifford (1962) included the months of November and December during the breeding seasons, however, the legislation ends the closure in October. These results indicated a clear disconnection between the management measures taken and scientific information about the species.

This is the first time that the reproductive cycle of C. guanhumi is analysed using microscopic observation and size at first maturity is estimated based on different methods. The main importance of developing research on population dynamics, with emphasis on reproductive biology of a species is to provide relevant scientific information to the appropriate agencies to encourage laws and fishery management standards in order to ensure the sustainable use of natural resources. The current law in north-eastern Brazil (IBAMA Normative No. 90, 2 February 2006) stipulates that the minimum size of capture for males in the States of Ceara, Rio Grande do Norte, Paraiba, Pernambuco, Alagoas and Sergipe is 6.00 cm (CW), although the size of the first sexual maturation found for males in the population analysed in this study was equal to 6.91 cm.

High catches of juveniles, smaller than the size at first maturity, can result in overfishing, which can bring serious damage to this important stock, compromising their sustainability. Finally, we highlighted the importance of environmental education to spread the knowledge that juvenile males can be identified by their chelae length being shorter than their carapace width and juvenile females by their abdomens not covering all their thoracic sternites.