INTRODUCTION

Amiantis umbonella is an edible bivalve mollusc that inhabits sandy–muddy intertidal zones throughout the north-west and south-east of the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman (Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, Dance, Moolenbeek and Oliver1995). The shell is ovate or ovate–triangular in shape (Al-Mohanna et al., Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2003) and varies in colour from white to mauve. This species has been introduced to the global markets as a commercial edible clam from the Iranian coast of the Persian Gulf. There are significant studies on growth and reproduction of venerid and donacid clams in different countries (Arneri et al., Reference Arneri, Giannetti and Antolini1998; Gasper et al., Reference Gasper, Ferreira and Monterio1999; Laudien et al., Reference Laudien, Brey and Arnttz2002; Zeichen et al., Reference Zeichen, Agnesi, Mariani, Maccaroni and Ardizzone2002), yet there are a few studies on A. umbonella. Spermatogenesis, oogenesis and the biology of A. umbonella have been studied in Kuwait and Qatar (Al-Mohanna et al., Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2001, Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2003; Al-Khayat & Al-Mohannadi, Reference Al-Khayat and Al-Mohannadi2006). Al-Mohanna et al. (Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2003) reported this species as a gonochoric species in Kuwait. Al-Khayat & Al-Mohannadi (Reference Al-Khayat and Al-Mohannadi2006) worked on biomass and annual abundance of A. umbonella in Qatar. This study provides the first estimate of reproduction, growth rate and production in Iran. The study area is characterized by high temperatures in summer and mild temperatures in winter (annual range 16–45°C). Seasonal winds, current regimes and high concentration of nutrients in this area provide a suitable place for benthic animals. It is known that changes in air and sea temperature influence macro-benthic community reproduction and production, but the effects of large fluctuations in temperature have not been studied to date. Considered a favourite food, the animals have been over-fished by local fishermen. For this reason, correct management to conserve this population is vital. This study contributes to the body of knowledge on reproduction, growth and production which should facilitate better management and conservation of the species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites and sampling

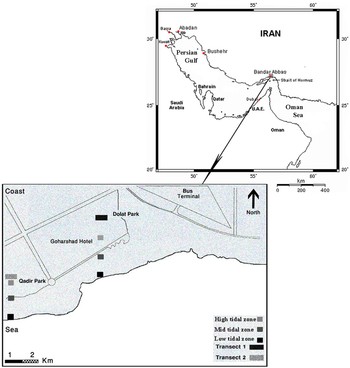

Specimens of A. umbonella were collected monthly from April 2007 to March 2008 at Park-e-Dolat 56°21′E 27°12′N and Park-e-Qadir 56°20′E 27°11′N, on the Golshahr coast in Bandar Abbas (Figure 1). Two transects (annual tidal range –0.1–3.88 m) were used and specimens were collected by hand from stations at low, mid and high tide zones. Three replicates at each of these stations were taken using 0.5 m2 quadrates. All specimens were fixed in 10% formaldehyde before transfer to the laboratory.

Fig. 1. Study area of Amiantis umbonella, Bandar Abbas coast, northern Persian Gulf. Insert shows the sampling sites at ‘Park-e-Dolat’ and ‘Park-e-Qadir’.

DATA ANALYSIS

Reproductive cycle and temperature

Two hundred and forty specimens (20 per month), ranging from 15 to 60 mm in total length, were prepared for histological examination. The gonad of this species is located in the visceral mass above the foot and ventral to the hepatopancreas (Al-Mohanna et al., Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2003). A small section of the gonad (2 mm) was removed. It was then fixed in Bouin's fixative for 24 hours, preserved in 70% alcohol, dehydrated in an ethanol series and infiltrated with paraffin. Sections 5–7 µm were stained with haematoxylin–eosin as per the method of Darriba et al. (Reference Darriba, Sanjuan and Guerra2004). Sex and different stages of gametogenesis development were determined by observation of gonadal smears under a compound binocular microscope. A gonadal condition index was determined using the formula: GCI = gonad fresh weight/valve dry weight (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Sanjuan and Guerra2004). Sex-ratio was determined by counting males and females. The length at first maturity was determined using the Logistic program. Sea surface temperature was recorded monthly to the nearest 0.1°C. The correlation between GCI and sea surface temperature was tested using the Pearson coefficient at 95% confidence limits.

Biometry and growth

Three morphometric characters were measured. These were the anterio-posterior length of the right valve (length), the dorso-ventral length of the right valve (width), and the distance between the two valves (height). Clams were measured to the nearest 0.1 mm with Vernier calipers. Five weight measurements were used; total weight (TW), wet weight of the soft parts (SPW), dry weight of shell free soft parts (SFDW) obtained by drying in 80°C for 24 hours as per the method of Sejr et al. (Reference Sejr, Sand, Jensen, Peterson, Christensen and Rysgard2002), dry weight of both valves (VW) obtained by drying valves in 60°C for 3 hours as per the method of Darriba et al. (Reference Darriba, Sanjuan and Guerra2004) and the gonad weight (GW). A digital balance was used for weighing specimens to the nearest 0.1 mg. Parameters of the relationship between length and the total weight were estimated using regression analysis (Park & Oh, Reference Park and Oh2002). The mean value of the allometric coefficient (b) (from April 2007 to March 2008) was tested by the Student's t-test at the 95% confidence limit.

The Von Bertalanffy growth was used to estimate growth parameters using the FISAT program (Baron et al., Reference Baron, Real, Ciocco and Re2004):

The method of Pauly (Reference Pauly1979) was used to determine t0:

Biomass and production

Total annual production was determined by the weight-specific growth rate method (Sejr et al., Reference Sejr, Sand, Jensen, Peterson, Christensen and Rysgard2002). The method utilizes pooled length–frequency samples, the VBG function and the length–weight relationship:

And Gi is the weight-specific growth rate yr−1 calculated by:

The mean annual biomass was calculated as follows:

The annual P/B ratio of all specimens was determined. Correlation between mean annual abundance and mean annual biomass was tested using the Pearson coefficient at the 99% confidence limit.

RESULTS

Biology of reproduction

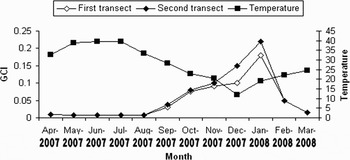

The sex-ratio of the animals was determined from 185 specimens. Ninety-nine clams (57.6%) were male and eighty-six (42.4%) were female. There was no significant difference to the 1:1 sex-ratio (χ 2 = 1.98; df = 1; P > 0.05). The animals showed synchronous gametogenic development and gonadal condition index (Figure 2), and there was no size difference between sexes. From the graph it can be seen that the minimum value of GCI (0.0069) was recorded in June, the period of sexual rest and the maximum value (0.22) was in January, the period of sexual ripeness. The GCI increased steadily from August to January peaking in late January when a major spawning event occurred. The GCI in the first transect was marginally higher than in the second transect during the year.

Fig. 2. Variation of gonadal condition index (GCI) for both sexes in Amiantis umbonella (mean±SE).

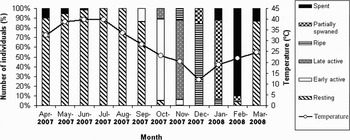

Gametogenic development began in September 2007 (autumn) and most of specimens (84%) were in the early active stage of development in October. In November 82% of individuals were observed to be in the late active stage. Most of clams (85%) were ripe in December and a major spawning event (75%) was observed in January. Ninety per cent of individuals were spent by late February. Eighty-seven per cent of clams were entered to the resting stage in March (early spring) (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Different stages of gametogenic cycle in male and female Amiantis umbonella and monthly sea surface temperature.

Temperature and gametogenic development were negatively correlated as shown in Figure 3 (Pearson coefficient; P < 0.05), the animals reaching maximum sexual activity when the temperature falls below 20°C.

Length at first maturity for both sexes was found to be at 22 mm (r2 = 0.53).

Histological studies indicated that there were six stages of gametogenic development. The stages are described as follows:

Stage 0 (resting stage)

The gonads were empty and sexes were indistinguishable. Connective tissue was present. At the macroscopic level, the gonads appeared small and wrinkled (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Photomicrograph showing the resting stage (Stage 0) in Amiantis umbonella. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Stage I (early active)

Miotic activity had commenced. Gonad volume was increased and thick walled follicles were present. In males, spermatocytes, spermatids and a few spermatogonia were observed. In females, a few oogonia and some previtellogenic oocytes were observed on the follicular walls. At the macroscopic level, because the gonads had increased in volume, no wrinkles were observed (Figures 5A & 6A).

Fig. 5. Photomicrographs showing stages in the development of male gonad in Amiantis umbonella: (A) Stage І; (B) Stage ІІ; (C) Stage ІІІ; (D) Stage ІV; (E) Stage V. Scale bar: 100 µm in (A, B & E), 50 µm in (C & D).

Fig. 6. Photomicrographs showing stages in the development of female gonad in Amiantis umbonella: (A) Stage І; (B) Stage ІІ; (C) Stage ІІІ; (D) Stage ІV; (E) Stage V. Scale bar: 100 µm in (C & E), 50 µm in (A, B & D).

Stage II (late active)

The follicles were enlarged and full of gametes. In males, spermatids and spermatocytes were abundant and a few spermatozoa were arranged radially in the centre of the follicles. In females, follicles were full of polygonal previtellogenic and vitellogenic oocytes. Previtellogenic oocytes were attached to the follicles walls by thin stalks whereas mature oocytes were freely present in the middle of follicles. Macroscopically, gonads covered the digestive glands and had increased in size (Figures 5B & 6B).

Stage III (ripe)

The greatly expanded follicles had thin walls and were located closely together. In males, a few spermatids were present. Spermatozoa were abundant with the tails pointed towards the centre of follicles. In females, the follicles contained abundant vitellogenic oocytes, although a few previtellogenic oocytes were also observed. At the macroscopic level, the gonads completely covered the digestive gland and the connective tissue had decreased (Figures 5C & 6C).

Stage IV (partially spawned)

Empty spaces were observed between follicles. Some follicles were completely empty. In males, a few spermatocytes were present and spermatozoa were decreased in number in contrast to the previous stage. In females, a few previtellogenic and vitellogenic oocytes were present and follicle volume was decreased. Macroscopically, the gonads were observed to have contracted (Figures 5D & 6D).

Stage V (spent)

After the major spawning, the follicles were small and completely empty. The connective tissues had been resorbed. A few mature spermatocytes and oocytes remained in follicles and some of the follicle walls were contracted. Macroscopically, the gonads were smaller and mainly empty (Figures 5E & 6E).

BIOMETRIC ANALYSIS, LENGTH–FREQUENCY DISTRIBIUTION AND GROWTH

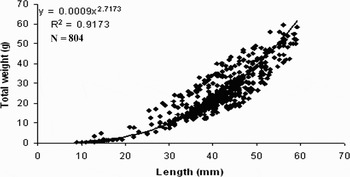

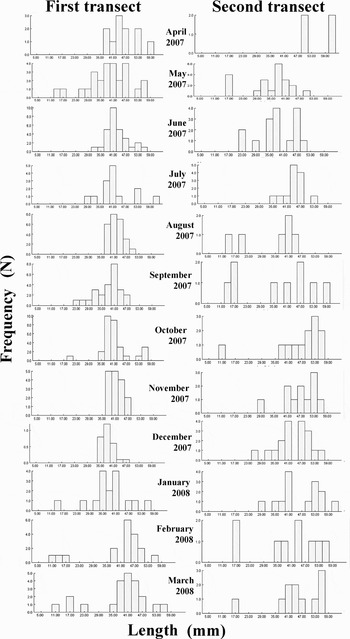

A total of 893 specimens were collected by hand during the twelve month study. More clams were found at the mid tide zone compared to high and low tide zones. The average anterior–posterior length of specimens in the first and the second transects were 39.64±7.27 mm and 40.15±11 mm, respectively. The largest clam was 60 mm and the smallest was 9 mm in anterior–posterior length. The average total weight was 22.47±9.84 in the first transect and 24.21±13.6 g in the second transect. The relationship between length and total weight of all specimens is W = 0.0009 L2.7173 (Figure 7). The mean allometric coefficient (b) was 2.65±0.27 during the study period (this value calculated for each month separately). The Student's t-test showed that the length–weight relationship was significantly different from b = 3 (t = 64; df = 11; P < 0.05). The growth pattern of A. umbonella was thus determined to be negatively allometric.

Fig. 7. Relationship between length and total weight in Amiantis umbonella for both transects.

The length–frequency distribution from monthly sampling indicated that there were 3 cohorts and that one recruitment occurred between February and March (Figure 8). The pooled length distribution is shown in Figure 9 and showed a unimodal pattern. The most abundant size-group was 38–44 mm in length and the growth rate for the sample was 5–7 mm/year. The Von Bertalanffy growth function parameters were calculated for both transects and there was no significant difference between the two sites (Student's t-test, P > 0.05). The values were found to be 58–62 mm for L∞, 0.28–0.29 yr−1 for K and –0.48 to –0.47 for t0.

Fig. 8. Length–frequency distributions of Amiantis umbonella. The frequency scale is the number of individuals in each 3 mm length-class.

Fig. 9. Pooled size–frequency distribution of Amiantis umbonella (3 mm size-classes).

Biomass and production

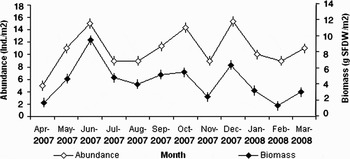

The mean annual clam abundance was calculated to be 10 individuals m−2. The relationship between length and shell free dry weight (determined for 360 specimens) was W = 0.006 L2.5 (g SFDW). Dry weight ranged from 0.002 to 2.1 g. This relationship was then used to estimate production. The mean annual biomass and production was 5.7 g SFDW m−2 and 0.49 g SFDW m−2 yr−1, respectively. The annual production/biomass ratio (P/B) was 0.086 yr−1. The mean annual abundance and biomass is shown in Figure 10 and there was a positive correlation between them (Pearson coefficient, P < 0.05). The maximum and minimum values of mean annual abundance were 15 ind m−2 in December and 5 ind m−2 in April, respectively. The maximum and minimum values of mean annual biomass were 9.9 g SFDW m−2 in June and 2.1 g SFDW m−2 in February, respectively.

Fig. 10. Abundance and biomass in Amiantis umbonella (mean±SE).

DISCUSSION

Biology of reproduction

This is the first study of reproduction and growth in A. umbonella in Iran. A few studies of spermatogenesis, oogenesis and the ecology of A. umbonella have been conducted in Kuwait and Qatar (Al-Mohanna et al., Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2001, Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2003; Al-Khayat & Al-Mohannadi, Reference Al-Khayat and Al-Mohannadi2006). In these studies, A. umbonella reached first maturity in the second year of life when the animals were approximately 22 mm in length. For Donax serra on Namibian sandy beaches length at first maturity was found to be 18.39 mm; however, the life span of this species is shorter than for A. umbonella (Laudien et al., Reference Laudien, Brey and Arnttz2002). Darriba et al. (Reference Darriba, Sanjuan and Guerra2004) used gonadal condition index in a study of reproduction in Ensis arquatus and reported an evolution of gonad condition with time similar to those in this study. Studies by Darriba et al. (Reference Darriba, Sanjuan and Guerra2004) and Remacha & Anadon (Reference Remacha and Anadon2006) on gametogenic development also reported that increased sexual activity was highly correlated to lower winter temperatures and it appears that decrease in temperature may be a stimulus for many clam species. In this study, six different reproductive stages could be identified. However, a study of Amiantis purpurata in Argentina (Morsan & Kroeck, Reference Morsan and Kroeck2005), reported only 5 stages (there being no stage of sexual rest). However, the timing of oogenesis and spermatogenesis for Amiantis purpurata was similar to that for A. umbonella in Iran. Al-Mohanna et al. (Reference Al-Mohanna, Al-Rukhais and Meakins2001) found that sexual development of A. umbonella in Kuwait commenced in early November when the water temperature was 24°C. In the Iran study, sexual development commenced much earlier, in September, when the sea surface temperature was around 27°C. However, both studies found that the animals undergo a sexual resting stage in summer.

LENGTH–FREQUENCY DISTRIBIUTION AND GROWTH

The length–total weight relationship for A. umbonella in Iran was significant (r2 = 0.91), and replicated the finding for A. umbonella in Qatar (r2 = 0.85; Al-Khyat & Al-Mohannadi, 2006). However, the mean allometric coefficient (b = 2.65±0.27) for this study indicated a negative allometric growth pattern which differed from the findings of the Qatar study, where the growth pattern was recorded as isometric (Al-Khayat & Al-Mohannadi, 2006). In other species of the Veneroidae, namely Ruditepes philipinarum and Cyclina sinesis, b values of 3.04 and 3.06 have been recorded, indicating again an isometric growth pattern (Park & Oh, Reference Park and Oh2002). Clearly, growth patterns can be variable and are probably linked to numerous biological and physical parameters. The length–shell free dry weight relationship was similar for both the Iran and Qatar studies (correlations of r2 = 0.67 and r2 = 0.65, respectively). In this study a growth rate of 5–7 mm/year was observed for the first year but this rate decreased sharply after the second year. Only one recruitment was observed in the year of this study and it occurred during February and March. Unimodal recruitment has been observed in Donax trunculus (Zeichen et al., 2003) and Tagelus plebeius (Holland & Dean, Reference Holland and Dean1977) as well as A. umbonella. A literature search of growth and production parameters for different clams (summarized in Table 1) showed that the information available is limited. The annual growth rate of A. umbonella is similar to that for Venus verrucosa (Veneridae) in the Adriatic (Arneri et al., Reference Arneri, Giannetti and Antolini1998) but A. umbonella reached a larger maximum size. In the same study area in Iran, Solen dactylus showed a similar annual growth rate to A. umbonella (Saeedi et al., in press). This suggests that the geographical and climatic conditions in addition to availability of nutrients in this area are the important factors in the clams' growth. The lowest growth rate was found in Hiatella arctica in Greenland (Sejr et al., 2002). Differences are likely to be related to latitudes and genetic disposition (Sejr et al., 2002).

Table 1. Parameters of Von Bertalanffy growth function, annual abundance biomass and production of different species of clams in different countries.

K, growth coefficient; L∞, asymptotic shell length; t0, age at length zero.

Biomass and production

In this study, the maximum biomass (9.9 g SFDW m−2) was found to occur in late June during summer; Wang & Hui (Reference Wang and Hui2008) reported phytoplankton blooms and unusually high water temperatures after cyclone Gonu in the Oman Sea, and these phenomena may have contributed to this finding. The minimum value of biomass (2.1 g SFDW m−2) was observed in February when water temperature had decreased. The biomass of A. umbonella in Qatar was also highest in summer decreasing to a minimum in April (Al-Khayat & Al-Mohannadi, Reference Al-Khayat and Al-Mohannadi2006). Abundance and biomass values were correlated for each month of the study period. This linked relationship has also been reported for A. umbonella in Qatar (Al-Khayat & Al-Mohannadi, Reference Al-Khayat and Al-Mohannadi2006), although the monthly biomass in Iran exceeded that for Qatar. The length spread for specimens in Iran (9–62 mm) was larger than for specimens in Qatar (10–45 mm), and this may account for the larger mean annual biomass and production. Sejr et al. (2002) have reported that biomass and production for Hiatella arctica varies at differing water depths. Biomass and production for this species at 40 m reaches the same value that A. umbonella reaches at 5–7 m (in mid and low tidal zones). This study has contributed to the knowledge on the biology of A. umbonella, and added to the information available for its shell fishery management.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to E. Kamaly and K. Jokar and other workers at the Fishery Research Laboratory of Bandar Abbas, The Persian Gulf and Oman Sea Ecology Research Center. Special thanks to Dr J. Kallie and Dr M.G. King for their critical reviews of this manuscript.