Introduction

The vacant shells of molluscs (mainly gastropods) are often used as shelters by diverse animal taxa, including hermit crabs (Reese, Reference Reese1969), tanaids (Kakui, Reference Kakui2019), polychaetes (Hylleberg, Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975), sipunculans (Cutler, Reference Cutler1994) and fishes (Bose et al., Reference Bose, Windorfer, Böhm, Ronco, Indermaur, Salzburger and Jordan2020). In addition, the shells used by hermit crabs and sipunculans are known to be inhabited by a variety of symbiotic animals (Gage, Reference Gage1968, Reference Gage1979; Kristensen, Reference Kristensen1970; Williams & McDermott, Reference Williams and McDermott2004; Goto et al., Reference Goto, Hamamura and Kato2007; Igawa et al., Reference Igawa, Hata and Kato2017; Yoshikawa et al., Reference Yoshikawa, Goto and Asakura2018; Jimi et al., Reference Jimi, Hookabe, Moritaki, Kimura and Imura2021; Herrán et al., Reference Herrán, Narayan, Doo, Klicpera, Freiwald and Westphal2022). The vacant shells are thus considered to play an important role in engineering the ecosystem and maintaining the biodiversity in the sea bottoms, as suggested in Gutiérrez et al. (Reference Gutiérrez, Jones, Strayer and Iribarne2003). However, despite the importance of the role of the vacant shells, studies of their ecological aspects remain scarce, except for hermit crabs (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1966, Reference Hazlett1972; Wada et al., Reference Wada, Ishizaki, Kitaoka and Goshima1999).

Sipunculans are a group of marine worms commonly included in Annelida based on molecular phylogenetic and phylogenetic analyses (e.g. Struck et al., Reference Struck, Schult, Kusen, Hickman, Bleidorn, McHugh and Halanych2007, Reference Struck, Paul, Hill, Hartmann, Hösel, Kube, Lieb, Meyer, Tiedemann, Purschke and Bleidorn2011; Weigert et al., Reference Weigert, Helm, Meyer, Nickel, Arendt, Hausdorf, Santos, Halanych, Purschke, Bleidorn and Struck2014; Rouse et al., Reference Rouse, Pleijel and Tilic2022). They comprise about 160 species in 16 genera and six families (Kawauchi et al., Reference Kawauchi, Sharma and Giribet2012; Schulze & Kawauchi, Reference Schulze and Kawauchi2021) and are morphologically characterized by an unsegmented body trunk, an anterior retractable introvert and the lack of the chaetae (Schulze & Kawauchi, Reference Schulze and Kawauchi2021). Most sipunculans inhabit burrows in soft sediments or live in crevices in hard substrata (e.g. rocks, shells, corals and woods) (Cutler, Reference Cutler1994; Ferrero-Vicente et al., Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Rubio-Portillo and Ramos-Esplá2016; Schulze & Kawauchi, Reference Schulze and Kawauchi2021), whereas some of them are known to dwell in the vacant shells of gastropods or scaphopods (Hylleberg, Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Piraino and Reichardt1983; Cutler, Reference Cutler1994; Ferrero-Vicente et al., Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Loya-Fernández, Marco–Méndez, Martínez–García and Sánchez-Lizaso2011, Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Loya-Fernández, Marco-Méndez, Martínez-García, Saiz-Salinas and Sánchez-Lizaso2012, Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Marco-Méndez, Loya-Fernández and Sánchez-Lizaso2013; Maiorova & Adrianov, Reference Maiorova and Adrianov2013; Schulze & Kawauchi, Reference Schulze and Kawauchi2021).

Shell-dwelling sipunculans are known from four genera; Phascolion (~20 spp., 5 subgen., 0–6000 m depth; Golfingiidae), Nephasoma (~23 spp., 3 subgen., 0–5000 m depth; Golfingiidae), Apionsoma (~5 spp., 2 subgen., 0–4000 m depth; Phascolosomatidae), and Aspidosiphon (~19 spp., 3 subgen., 0–200 m depth; Aspidosiphonidae) (Cutler, Reference Cutler1994).

Shell utilization pattern of sipunculans has been relatively well studied in species in the Atlantic Ocean. In the western coast of Sweden, Phascolion (Phascolion) strombus strombus (Montagu 1804) used more frequently the shells of the gastropods Littorina littorea (Linnaeus 1758) and Turritella communis (Risso 1826) and the scaphopod Dentalium entalis (Linnaeus 1758) than other shells (Hylleberg, Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975). In addition, a significant positive linear correlation was detected between the body weight of P. strombus strombus and the length of the shells used by them (Hylleberg, Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975). Hylleberg (Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975) suggested by laboratory experiment data that P. strombus strombus swap shells when in those too small for them. In the Indian River Lagoon of Florida, Phascolion (Lesenka) cryptum Hendrix, 1975 were commonly found in shells of five species of gastropods and most frequently in shells of Cerithium muscarum Say, 1832 (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Piraino and Reichardt1983). Furthermore, P. cryptum was observed to always move to intact shells when their original shells were artificially reduced in size by being partially broken (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Piraino and Reichardt1983). In the western Mediterranean Sea, five species of sipunculans were identified as shell-dwelling species (Pancucci-Papadopoulou et al., Reference Pancucci-Papadopoulou, Murina and Zenetos1999; Coll et al., Reference Coll, Piroddi, Steenbeek, Kaschner, Ben Rais Lasram, Aguzzi, Ballesteros, Bianchi, Corbera, Dailianis, Danovaro, Estrada, Froglia, Galil, Gasol, Gertwagen, Gil, Guilhaumon, Kesner-Reyes, Kitsos, Koukouras, Lampadariou, Laxamana, López-Fé de la Cuadra, Lotze, Martin, Mouillot, Oro, Raicevich, Rius-Barile, Saiz-Salinas, San Vicente, Somot, Templado, Turon, Vafidis, Villanueva and Voultsiadou2010). Among them, Aspidosiphon (Aspidosiphon) muelleri (Diesing 1851), P. strombus strombus and Phascolion (Phascolion) caupo (Hendrix 1975) used both gastropod shells and empty polychaete tubes as shelters (Ferrero-Vicente et al., Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Loya-Fernández, Marco–Méndez, Martínez–García and Sánchez-Lizaso2011, Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Loya-Fernández, Marco-Méndez, Martínez-García, Saiz-Salinas and Sánchez-Lizaso2012, Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Marco-Méndez, Loya-Fernández and Sánchez-Lizaso2013). In addition, a significant linear correlation was detected between the trunk width of A. muelleri and the inner diameter of the tube used as the shelter (Ferrero-Vicente et al., Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Marco-Méndez, Loya-Fernández and Sánchez-Lizaso2013). However, to understand the shell utilization patterns of sipunculans in more detail, a further quantitative study, especially in species in other geographic localities and sea depths, is needed.

In this study, we investigated shell utilization patterns of sipunculans collected from 57–800 m depth at three localities along the Pacific coast of Japan. Then, we examined the relationship between the shell size and body size of sipunculans and also the shell shapes preferred by species of the genus of Phascolion.

Materials and methods

Sampling

We collected shell-dwelling sipunculans from 14 stations of the following three study sites along the Pacific coast of Japan by dredge or beam trawl: (1) Shimoda (Station 1, off Shimoda, Shizuoka Prefecture, 200 m depth) (2) Kumanonada (Stations 2, 6–11, Kumano Sea, Mie Prefecture, 57–289 m depth) and (3) Tanabe (Stations 3–5, 12–14, off Tanabe Bay, Wakayama, Prefecture, 87–800 m depth) (Figure 1; Table 1). In three stations of Tanabe site (Stations 12–14), we collected not only the shells occupied by sipunculans, but also those occupied by other animals and unoccupied vacant shells. All the specimens were fixed with 99.5% ethanol and deposited in Seto Marine Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University.

Fig. 1. Sampling localities. Circles indicate sampling stations: (A) Japanese Archipelago; (B) Kii Peninsula, Japan. Shimoda (Station 1), Kumanonada (Stations 2, 6–11), Tanabe (Stations 3–5, 12–14).

Table 1. Sampling information

Observation and measurements

Sipunculans

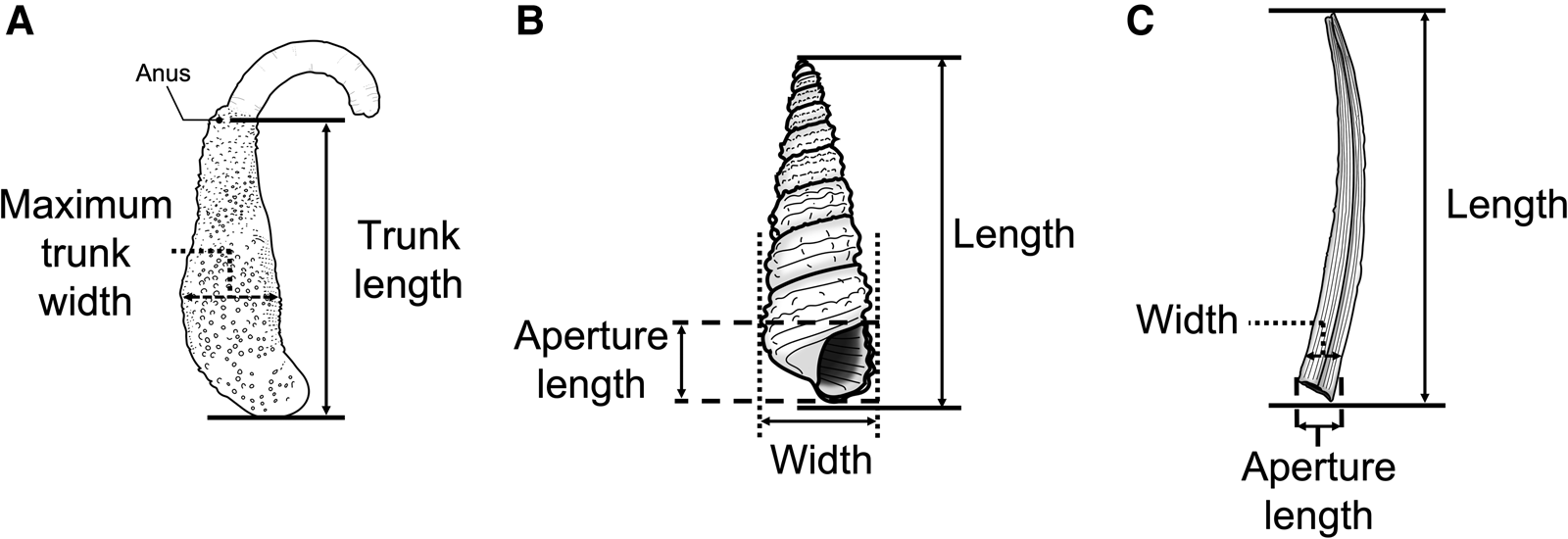

We removed the ethanol-fixed specimens of sipunculans from the shells by breaking them open with a small vise and then measured the following parameters of sipunculans with a calliper: trunk length (TL) and maximum trunk width (TW) (Figure 2A). The specimens were photographed after measurement. It was difficult to identify most sipunculan specimens to the species level or subgenus level because the internal structures that are diagnostic characters were substantially shrunken due to the fixation by ethanol. Thus, we used only genus-level identification for the analysis in this study. The identification was basically based on the keys described in Cutler (Reference Cutler1994).

Fig. 2. Size measurements of shell/tube-dwelling sipunculans and their snail shells: (A) Sipuncula, (B) Gastropoda, (C) Scaphopoda.

Vacant shells of gastropods and scaphopods

All the shells were photographed and most of them were identified to the genus level. However, some shells were highly degraded and thus difficult to identify to the genus level. The following parameters of the shells were measured with a caliper: shell length (SL), shell width (SW) and shell aperture length (SA) (Figure 2B, C).

Statistical analyses

Size correlation between sipunculans and their shells

We used Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient (r) to check whether there is a significant relationship between the shell size and the body size of the sipunculans. This test was conducted using the ‘cor.test’ function of R ver. 3.5.3 (R Core Team, 2019).

Preference for gastropod shell shape in Phascolion

To determine which shell characteristics can influence the shell selection by Phascolion spp., we performed generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) analyses. In this analysis, the presence of Phascolion individual (presence = 1, absence = 0) was used as the response variable, and the following three factors were incorporated as factorial explanatory variables: (1) shell length, (2) shell width and (3) shell aperture length. Then, the family of shells was selected as a random factor. We used the specimens collected from three stations (Stations 12–14) of Tanabe site for the analyses.

Shells collected from these stations belonged to 23 gastropod families and were utilized by individuals of sipunculans (Phascolion spp. and Aspidosiphon spp.), hermit crabs (Catapagurus sp.) and other crustaceans (Bubocorophium sp.) (Figure S1). Among shell dwellers, Phascolion spp. were most abundant (Figure S1). In these stations, the sipunculans with scaphopod shells were scarce (N = 2) and thus not included in the analysis.

GLMM analyses were conducted using the glmmML function of R ver. 3.5.3. After the maximum-likelihood estimation, the parametric values that maximized likelihoods were obtained by using the glmmML function. Then, the AIC value between each model was compared using the dredge function of the statistical package R. The model with the lowest AIC value was adopted and the factor that affects the shell selection of the species of Phascolion discussed. Also, we performed logistic regression for each of the explanatory variables used in GLMM analyses to evaluate correlations between them and thereby facilitate the interpretation of the results.

Results

Composition of sipunculans genera among shells

A total of 302 individuals of sipunculans, including 273 individuals of Phascolion and 29 individuals of Aspidosiphon, were collected (Figure 3). Each sipunculan individual was solitary. Phascolion was more abundant than Aspidoshion in all three study sites at all depths except for the 200–300 m depth range at the Kumanonada site (Figure 4).

Fig. 3. Shell-dwelling sipunculans. Sipunculans belonging to Phascolion (A, B) and Aspidosiphon (C, D). (A, C) Individuals inhabiting shells. (B, D) Individuals removed from their dwelling shells. Each panel shows a different individual. Scale bars = 4 mm.

Fig. 4. The ratios of Phascolion to Aspidosiphon in each sampling site and depth. Black = Phascolion; Stripe = Aspidosiphon: (A) Each sampling locality, (B) Each sampling depth.

Diversity of molluscan shells used by sipunculans

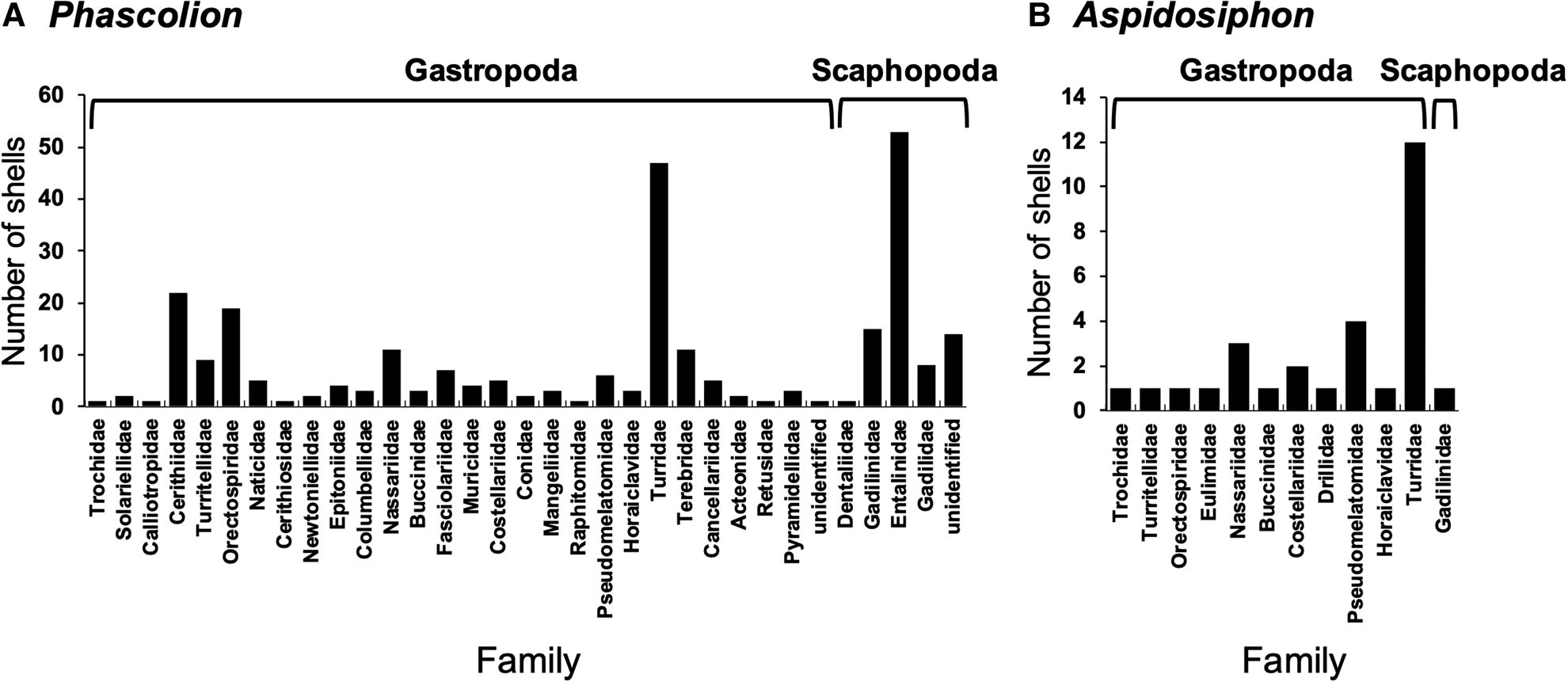

The vacant shells used by Phascolion species contained 38 gastropod genera of 27 families and six scaphopod genera of four families (Table S1; Figure 5). On the other hand, the vacant shells used by Aspidosiphon species contained 11 gastropod genera of 11 families and one scaphopod genus (Table S2; Figure 5). The gastropod shells most frequently used by Phascolion species were those of Turridae (N = 47), Cerithiidae (N = 22) and Orectospiridae (N = 19), whereas the scaphopod shells most frequently used by Phascolion species were those of Entalinidae (N = 51), Gadilinidae (N = 15) and Gadilidae (N = 8) (Table S1; Figures 5, 6A–F). The gastropod shells most frequently used by Aspidosiphon species were those of Turridae (N = 12), Pseudomelatomidae (N = 4) and Nassariidae (N = 3), whereas the scaphopod shells used by Aspidosiphon species were only that of Gadlinidae (N = 1) (Table S2; Figures 5, 6G–J).

Fig. 5. Total number of individuals of shell families used by Phascolion and Aspidosiphon species. (A) Phascolion, (B) Aspidosiphon.

Fig. 6. Vacant shells most frequently used by species of Phascolion (A–F) and Aspidosiphon (G–J): (A) Turridae, (B) Cerithiidae, (C) Orectospiridae, (D) Entalinidae, (E) Gadilinidae, (F) Gadilidae, (G) Turridae, (H) Pseudomelatomidae, (I) Nassariidae, (J) Gadilinidae. Scale bars = 4 mm.

The gastropod shells most frequently used by Phascolion species were those of Cerithiidae (N = 2) at Shimoda, Turridae (N = 29) at Kumanonada and Orectospiridae (N = 18) at Tanabe (Table S1; Figure 7), whereas the scaphopod shells most frequently used by them were those of Entalinidae (N = 25) at Kumanonada and Entalinidae (N = 26) at Tanabe (Table S1; Figure 7). At Shimoda, scaphopod vacant shells used by shell-dwelling sipunculans were not found.

Fig. 7. Number of individuals of shell families used by Phascolion and Aspidosiphon species at each sampling locality. Black bars = Phascolion, Stripe bars = Aspidosiphon. (A) Shimoda, Shizuoka, Japan, (B) Kumanonada, Mie, Japan, (C) Tanabe, Wakayama, Japan.

On the other hand, the gastropod shells most frequently used by Aspidosiphon species were those of Turridae at Kumanonada (N = 7) and at Tanabe (N = 5), whereas the scaphopod shell most frequently used by them was those of Gadilinidae (N = 1) at Kumanonada (Table S2; Figure 7). Aspidosiphon species with scaphopod vacant shells were not found at Tanabe (Figure 7C). Aspidosiphon species was not collected at Shimoda (Figure 7A).

Relationship of size between sipunculans and their shells

There was positive linear correlation between the body size of Phascolion individuals and the size of gastropod vacant shells collected at Shimoda, Tanabe and Kumanonada (Tables S3 and S4; Figure 8). Except for Shimoda, where no scaphopod shells occupied by sipunculans were found, there were positive linear correlations between the body size of Phascolion individuals and the size of scaphopod vacant shell collected at Tanabe and Kumanonada (Tables S3 and S4; Figure 9).

Fig. 8. Correlation equations between the body size of Phascolion species and their gastropod shell size: (A) trunk length and shell length, (B) trunk length and shell width, (C) trunk length and shell aperture length, (D) trunk width and shell length, (E) trunk width and shell width, (F) trunk width and shell aperture length.

Fig. 9. Correlation equations between the body size of Phascolion species and their scaphopod shell size: (A) trunk length and shell length, (B) trunk length and shell width, (C) trunk length and shell aperture length, (D) trunk width and shell length, (E) trunk width and shell width, (F) trunk width and shell aperture length.

There were positive linear correlations between the body size of Aspidosiphon species and the size of gastropod vacant shell collected at Kumanonada (Tables S5 and S6; Figure 10).

Fig. 10. Correlation coefficient and regression line between the body size of Aspidosiphon species and gastropod shell size: (A) Trunk length and shell length, (B) Trunk length and shell width, (C) Trunk length and shell aperture length, (D) Trunk width and shell length, (E) Trunk width and shell width, (F) Trunk width and shell aperture length.

Shell-shape preference of Phascolion

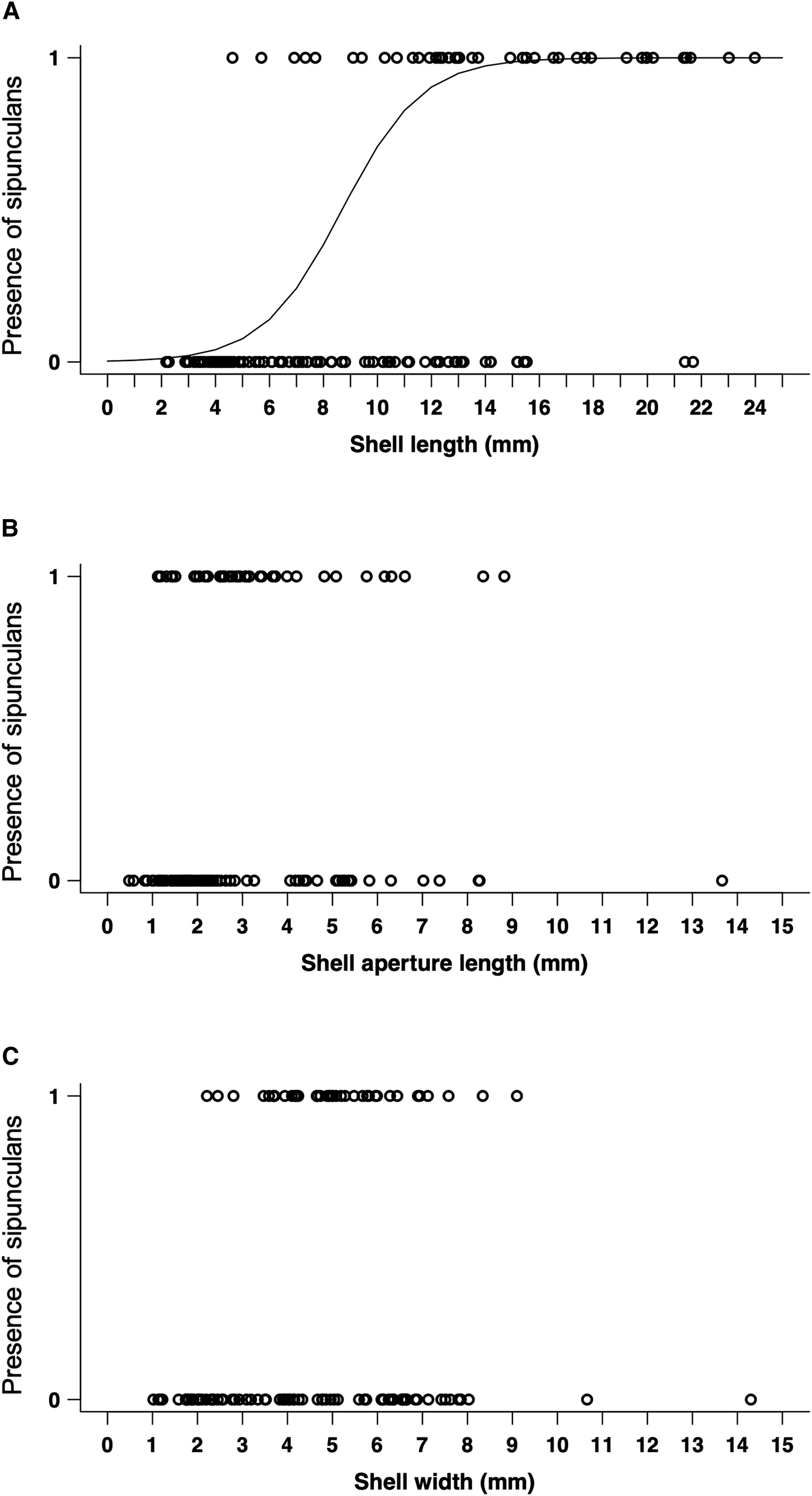

The results of GLMM analysis are shown in Table 2. The best fitted model with the lowest AIC was the one that includes ‘shell length’ and ‘shell width’ as factorial explanatory variables (AIC = 73.2) (Tables 2 and 3). The other selected models were summarized in Table 2. Among the explanatory variables, only the shell length was suggested to be significant (Table 3; Figure 11).

Fig. 11. Logistic regression for each factor. Scatter diagram and correlation matrix diagram of each factorial explanatory variable: (A) Shell length, (B) Shell width, (C) Shell aperture length.

Table 2. Results of each model of the generalized linear mixed model analysis with AIC value ordered by decreasing AIC

Table 3. Results of a generalized linear mixed model for the shell-shape preference of Phascolion species

Discussion

Generic composition of sipunculans

The species of Phascolion and Aspidosiphon were found to occur sympatrically across a wide range of depth from 57–800 m along the Pacific coast in this study, and shells utilized by Phascolion species were more abundant than those shells utilized by Aspidosiphon species in all sampling sites and depths, except at a depth of 200–300 m in Kumanonada. However, dominance of Aspidosiphon species among shell-dwelling sipunculans was also reported in other sea areas. For example, A. muelleri is known to be dominant in the western Mediterranean Sea among shell-dwelling sipunculans (Açik et al., Reference Açik, Murina, Çinar and Ergen2005; Ferrero-Vicente et al., Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Loya-Fernández, Marco–Méndez, Martínez–García and Sánchez-Lizaso2011, Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Marco-Méndez, Loya-Fernández and Sánchez-Lizaso2013). Various factors, such as habitat preference, geographic region, depth and interspecific competition, likely play a role of determining the dominant shell-dwelling sipunculan species (or genus) and their community structure, although they remain not well studied. The studies in the Mediterranean Sea were mainly conducted in shallow water depth (6–45 m) of the Atlantic Sea, whereas the present study was carried out in the deeper area of the Pacific. Such differences in the geographic region and sea depth may be associated with differences in the community structure of shell-dwelling sipunculans.

It has been reported that the demand for shells by hermit crabs often exceeds the supply by snails (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981), and thus they rob shells used by other individuals to obtain shells that fit their body size better (Asakura, Reference Asakura1984). This is probably the case with the shell-dwelling sipunculans. If such competition occurs, the abundance of the less competitive species is expected to be smaller than the other. This may be the reason why Phascolion spp. are more dominant than Aspidosiphon spp. in almost all the study sites. However, it remains unclear whether shell-dwelling sipunculans deprive other individuals of the shells. A further experimental verification may be necessary to clarify this.

Diversity of molluscan shells used by sipunculans

The species of Phascolion used a wide range of gastropod and scaphopod shells as shelters in this study. In the western coast of Sweden, P. strombus strombus used all the shells available in the study area (Hylleberg, Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975). Similarly, in the Indian River Lagoon of Florida, P. cryptum was also found in all of the most commonly occurring shells (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Piraino and Reichardt1983). Furthermore, it is known that Phascolion in the Mediterranean Sea used not only the gastropod shells but also the tube of the polychaete Ditrupa arietina (Müller 1776) (Ferrero-Vicente et al., Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Loya-Fernández, Marco–Méndez, Martínez–García and Sánchez-Lizaso2011, Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Loya-Fernández, Marco-Méndez, Martínez-García, Saiz-Salinas and Sánchez-Lizaso2012, Reference Ferrero-Vicente, Marco-Méndez, Loya-Fernández and Sánchez-Lizaso2013). Taken together, these results suggested that Phascolion species could potentially utilize a wide range of sea shells and also morphologically shell-like shelters.

The species of Aspidosiphon also used a wide range of gastropod and scaphopod shells as shelters in this study. However, the number of gastropod and scaphopod families of the shells used by Aspidosiphon species were fewer than those of Phascolion species. Although this result may be simply due to the collection of more specimens of Phascolion species, it is possible that Aspidosiphon species have a more strict shell preference than Phascolion species.

Turridae is the only family whose shells were collected at all sampling sites and frequently used by both Phascolion and Aspidosiphon spp. The results may imply that Phascolion and Aspidosiphon spp. prefer to use the shells of Turridae, although they are apparently able to utilize a wide variety of shells as mentioned above. In this study, the identification of shell-dwelling sipunculans was limited to the genus level. Therefore, identification at the subgenus or species level may lead to different views or clearer tendencies in terms of shell preferences.

Relationship of size between sipunculans and their shells

The result of linear regression in this study indicates that, as shell size increases, so does the size of Phascolion in the shell. Two hypotheses can explain the correlation detected in this study. The first hypothesis is that sipunculans do not move across shells and that the size of the shells that the sipunculans first settle on determines the upper limit of their growth. In this case, small individuals of Phascolion species in large shells are supposed to be observed. However, such individuals were not found in this study. Thus, this hypothesis is unlikely to explain the findings of the present study. The second hypothesis is that sipunculans move across shells as they grow, like hermit crabs. Hylleberg (Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975) conducted an experiment in the laboratory to determine whether P. strombus strombus performed a shell-exchanging behaviour. In his experiment, P. strombus strombus was kept in a 1 ml syringe and the free space in the syringe was reduced by 0.05 ml every other day. As a result, when it filled out the space of the syringe, P. strombus strombus left the syringe and entered the vacant shell of Turritella. Rice et al. (Reference Rice, Piraino and Reichardt1983) observed in the field that immature juveniles and adults of P. cryptum were found in smaller and larger shells, respectively. Furthermore, their laboratory experiments showed that P. cryptum move to intact shells when their original shells are partially broken and artificially decreased in size. These results suggest that the species of Phascolion can exchange the shells as they grow. If Phascolion species in our study also exchange their shells as they grow, it can explain the positive correlation of size between sipunculans and their shells.

Shell shape preference of Phascolion

Although Phascolion were collected from a wide range of gastropods, GLMM analysis suggested that they tend to use long and narrow shells. Especially, the shell length was suggested to be the most significant factor in the shell selection of Phascolion spp.

Phascolion species in this study often used the vertically long shells of Turridae. Similarly, the gastropod shells of Cerithiidae and Orectospiridae, which were most frequently used by Phascolion species at Shimoda and Kumanonada, respectively, are also long vertically. The body of sipunculans, including Phascolion, is slender and anteroposteriorly long (Cutler, Reference Cutler1994). Thus, long shells apparently can fit the sipunculan body better and provide them ample inner space inside the shells to escape when they encounter predators.

The reason why Phascolion species use narrow shells may also due to their morphological characteristics. Phascolion species have a small thorn-like structure (namely, holdfast papillae) on the trunk, which are thought to prevent their body from being pulled out of the shell (Hylleberg, Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975; Cutler, Reference Cutler1994). For this structure to function effectively, sipunculans need to live in shells with an inner diameter close to the width of the trunk. In an experiment, P. strombus strombus given a glass tube as a shelter did not use the tube if its inner diameter was larger than its own body width, but stayed inside the tube if it was slightly smaller or equal in size (Hylleberg, Reference Hylleberg, Rice and Todorovic1975).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315422000297

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Y. Maekawa, T. Nakamura and the other crew of TRV Seisui-maru (Mie University), S. Ohtsuka (Hiroshima University), M. Shimomura (Seto Marine Biological Laboratory (SMBL), Kyoto University), and the other participants in the joint survey for benthic organisms conducted around Kumanonada on 27–30 November 2018 (the research cruise No. 1828), H. Nakano, T. Sato, J. Takano, D. Shibata and T. Kodaka (Shimoda Marine Research Center, University of Tsukuba), H. Kohtsuka (Misaki Marine Biological Station, the University of Tokyo), and all participants in the 13th Japanese Association for Marine Biology (JAMBIO) Coastal Organism Joint Survey conducted at Shimoda on 25–26 October 2017 for their support during sampling and field survey; T. Kimura and S. Kimura (Mie University) for permission to use the samples collected in the survey for benthic organisms conducted around Kumanonada by TRV ‘Seisui-maru’ (Mie University) on 7–14 November 2017 (research cruise No. 1722); T. Takano (Meguro Parasitological Museum, Japan) for helping with the identification of the shell specimens; K. Harada, M. Kawamura, H. Yamauchi, K. Yamamoto (SMBL) for helping us to collect the specimens used in this study; R. Nakayama for his advice and support; and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge all the members of SMBL for their encouragement for this study.

Financial support

This study was financially supported by the Research Institute of Marine Invertebrates.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.