Introduction

Mantis shrimps or stomatopods (Crustacea: Malacostraca) are predatory marine crustaceans, which are found mainly in tropical and subtropical coastal waters and are characterized by the remarkably developed second maxilliped that has been modified as a powerful raptorial appendage (Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Chan and Liao2008). Almost 500 species of stomatopods are known and divided into 17 families within seven superfamilies (Ahyong & Harling, Reference Ahyong and Harling2000; Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Chan and Liao2008; Van Der Wal & Ahyong, Reference Van Der Wal and Ahyong2017; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Ahyong and Kim2019; WoRMS, 2021). The life history of stomatopods involves a series of larval stages consisting of short propelagic and long pelagic phases. The last-stage larval metamorphosizes into a post-larva and settles into the adult benthic habitat after a single moult (Pyrne, Reference Pyne1972; Feller et al., Reference Feller, Cronin, Ahyong and Porter2013). Larval forms of stomatopods are highly specialized among crustacean larvae as they possess a remarkable set of morphological characteristics such as large, fully functional raptorial second maxillipeds and often large body size that can be up to 50 mm in total length (Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Haug, Haug, Martin, Olesen and Høeg2014; Wiethase et al., Reference Wiethase, Haug and Haug2020). Stomatopods can exhibit a greater variety of ecological adaptations in larvae than in adults due to their distinct larval forms (Haug et al., Reference Haug, Ahyong, Wiethase, Olesen and Haug2016).

While all stages of the stomatopod larvae can be clearly recognized from other crustacean larvae, identifying them to the species level based on their morphological characters is still difficult. Only around 10% of known species could be identified in their larval stages (Diaz, Reference Diaz1998; Haug et al., Reference Haug, Ahyong, Wiethase, Olesen and Haug2016). Traditionally, the identification of stomatopod larvae has been performed either by hatching larvae from a known adult or by cultivating wild-caught larvae to adulthood; however, these laboratory methods are time-consuming and extremely challenging (Provenzano & Manning, Reference Provenzano and Manning1978; Diaz, Reference Diaz1998; Feller et al., Reference Feller, Cronin, Ahyong and Porter2013). Descriptions of the entire series of larval stages using those two methods exist for five of the 500 extant species: (1) Neogonodactylus oerstedii (Hansen, 1895) (as Gonodactylus oerstedii) (Manning & Provenzano, Reference Manning and Provenzano1963; Provenzano & Manning, Reference Provenzano and Manning1978), (2) Neogonodactylus wennerae Manning & Heard, 1997 (as Gonodactylus bredini Manning, 1969) (Morgan & Goy, Reference Morgan and Goy1987), (3) Pterygosquilla schizodontia (Richardson, 1953) (as Squilla armata H. Milne Edwards, 1837) (Pyne, Reference Pyne1972), (4) Heterosquilla tricarinata (Claus, 1871) (Greenwood & Williams, Reference Greenwood and Williams1984) and (5) Oratosquilla oratoria (De Haan, Reference De Haan1833–1850) (Hamano & Matsuura, Reference Hamano and Matsuura1987). Even partial larval series are known only for a restricted number of species (Gurney, Reference Gurney1946; Alikunhi, Reference Alikunhi1967; Michel, Reference Michel1968, Reference Michel1970; Michel & Manning, Reference Michel and Manning1972; Shanbhogue, Reference Shanbhogue1975; Rodrigues & Manning, Reference Rodrigues and Manning1992; Ahyong, Reference Ahyong2002; Veena & Kaladharan, Reference Veena and Kaladharan2010; Feller et al., Reference Feller, Cronin, Ahyong and Porter2013; Cházaro-Olvera et al., Reference Cházaro-Olvera, Ortiz, Winfield, Robles and Torres-Cabrera2018). Therefore, a scarcity of information linking larvae to adult forms clearly exists. To overcome the obstacles and complexities of traditional taxonomic methods, particularly for groups of species with multiple developmental stages, DNA barcoding as a taxonomic method has been applied for the early life stages (Abinawanto et al., Reference Abinawanto, Intan, Wardhana and Bowolaksono2019).

DNA barcoding, proposed by Hebert et al. (Reference Hebert, Ratnasingham and De Waard2003), is one of the molecular identification methods that is intensely applied in taxonomic study of groups and an effective tool for linking larvae with their adults. DNA barcoding was originally performed by analysing the short nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene from taxonomically unidentified specimens and comparing them with the known sequences stored in public databases, such as the GenBank database and Barcode of Life database. Nowadays, diverse gene regions are successfully used for DNA barcoding in a wide range of both aquatic and terrestrial animal taxa (Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Penton, Burns, Janzen and Hallwachs2004a, Reference Hebert, Stoeckle, Zemlak and Francis2004b; Hajibabaei et al., Reference Hajibabaei, Janzen, Burns, Hallwachs and Hebert2006; Wakabayashi et al., Reference Wakabayashi, Suzuki, Sakai, Ichii and Chow2006, 2017; Hubert et al., Reference Hubert, Hanner, Holm, Mandrak, Taylor, Burridge, Watkinson, Dumont, Curry, Bentzen and Zhang2008; De Grave et al., Reference De Grave, Chan, Chu, Yang and Landeira2015; Carreton et al., Reference Carreton, Planella, Heras, García-Marín, Agulló, Clavel-Henry, Rotllant, Dos Santos and Roldán2019). A DNA barcode is also useful to identify larvae collected from the field into species by matching with the available sequences from GenBank. Such methods have already been applied to crabs, barnacle larvae, fish larvae and stomatopods (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yau and Ng2010; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Høeg and Chan2013; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Loh, Ng, Ooi, Konishi, Huang and Chong2019; Li et al., Reference Li, Shih, Ho and Jiang2019; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Gu, Liu, Lin, Lee, Wai, Lam, Yan and Leung2021; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021). In addition, DNA barcoding as a method for identifying stomatopod larvae has been used not only for taxonomy (Barber & Erdmann, Reference Barber and Erdmann2000; Feller et al., Reference Feller, Cronin, Ahyong and Porter2013) but also for experimental (Feller & Cronin, Reference Feller and Cronin2014; Feller et al., Reference Feller, Wilby, Jacucci, Vignolini, Mantell, Wardill, Cronin and Roberts2019) and diversity or distribution studies (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Moosa and Palumbi2002; Barber & Boyce, Reference Barber and Boyce2006; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yau and Ng2010; Abinawanto et al., Reference Abinawanto, Intan, Wardhana and Bowolaksono2019). Although this method has been utilized effectively for stomatopod identification, it is still in the early stages of development since the DNA sequences available for barcoding stomatopods (such as COI and 16S rRNA genes) are limited (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yau and Ng2010). Therefore, as demonstrated in the current study, the assignment of larval specimens to the species level may need the addition of more sequences from the adult specimens with verified morphological identification.

Although the diagnostic morphologies of stomatopod larvae are scarce, the late-stage larvae are easily classified into at least the superfamily level using the morphological characters of carapace, abdomen, uropods and telson (Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Haug, Haug, Martin, Olesen and Høeg2014). The larvae of the superfamily Squilloidea can be distinguished from those of the other superfamilies based on a flatter carapace and a slender abdomen (Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Haug, Haug, Martin, Olesen and Høeg2014). In Japan, 25 out of 70 recorded species are classified in the Squilloidea (Ahyong, Reference Ahyong2012; Osawa & Fujita, Reference Osawa and Fujita2016; Nakajima et al., Reference Nakajima, Osawa and Naruse2020) and among them, late-stage larvae have been described in 12 squilloid species (Alikunhi, Reference Alikunhi1944, Reference Alikunhi1952, Reference Alikunhi1975; Manning, Reference Manning1962; Hamano & Matsuura, Reference Hamano and Matsuura1987; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Li, Yang, Zheng, Cai and He2006; Veena & Kaladharan, Reference Veena and Kaladharan2010; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021). During our recent cruise in the Seto Inland Sea of Japan, late-stage larvae with a pair of large orange spots on the basal part of the fifth pleopods were found. Such larvae have not been described until now. In this paper, we document a detailed morphological description of the squilloid larvae, which were confirmed as Levisquilla inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965) via a DNA barcoding technique using an adult specimen found at the same location on the same day.

Materials and methods

Sampling

The larval specimens were sorted from plankton samples collected by an Ocean Research Institute (ORI) net (Omori, Reference Omori1965; Omori et al., Reference Omori, Marumo and Aizawa1965) with a diameter of 160 cm and mesh size of 0.33 mm that was operated by the crew of the training and research vessel ‘TOYOSHIO MARU’, Hiroshima University. The net was towed in the Seto Inland Sea (33°49′59″N 132°23′41″E) at a depth of 30–40 m on 29 October 2020. The adult specimen was found in sediment that was dredged from a depth of 70 m at the same location on the same day. Both live larval and adult specimens were photographed (Figure 1) and then preserved in 99% ethanol for subsequent morphological and molecular analyses.

Fig. 1. Levisquilla inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965), live: (A) larva (ventral); (B) adult (dorsal). Scale bars: A, 1 mm; B, 5 mm.

Morphological observation

The larval specimens were observed and dissected under a stereomicroscope (SZX-9, Olympus). The stereomicroscope was also used for morphometric characteristics, including the total length (TL) from the tip of the rostrum to the apex of the submedian tooth on the telson, the rostrum length (RL) from the tip to the base of the rostrum, the carapace length (CL) as the distance from the base of the anterolateral spine to the base of the posterolateral spine on the carapace, and the carapace width (CW) as the maximum distance across the carapace. The dissected appendages were preserved in 70% ethanol or mounted on glass slides using a mounting agent (CMCP-10 high-viscosity mountant; Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA), and then observed under a compound microscope (BX-51, Olympus). The developmental stage of the larval specimens was determined according to Hamano & Matsuura (Reference Hamano and Matsuura1987). They hatched larvae from females of the Japanese mantis shrimp and illustrated the entire sequence of larval stages in detail.

Illustrations for larval and adult specimens were created with the aid of the camera lucida attachment (U-DA, Olympus). The terminology of the body structure followed the structures of Hamano & Mantsuura (Reference Hamano and Matsuura1987), Ahyong (Reference Ahyong2001) and Feller et al. (Reference Feller, Cronin, Ahyong and Porter2013).

An adult male mantis shrimp was also included for the gene analysis to confirm larval identity. This specimen was morphologically identified as Levisquilla inermis based on the dactylus claw with six teeth (Figure 2A), the fifth thoracic somite with short, anteriorly recurved spine (Figure 2B), the absence of supplementary carinae on the dorsolateral surface of the telson (Figure 2C), and the absence of a post-anal carina. The total length measured from the tip of the rostral plate to the apices of the submedian teeth of the telson was 25.4 mm, and carapace length measured along the dorsal midline excluding the rostral plate was 6.1 mm.

Fig. 2. Levisquilla inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965), adult male: (A) right raptorial claw (lateral); (B) lateral processes of fifth, sixth and seventh thoracic somites; (C) last abdominal somite and telson (dorsal). Scale bars: A–C, 1 mm.

Both larval (NSMT-Cr 29221, 29222) and adult (NSMT-Cr 29223) specimens were deposited in the crustacean collections of the National Museum of Nature and Science, Tsukuba, Japan (NSMT).

Molecular analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from one pleopod with some pleon muscles of both larval and adult specimens using NucleoSpin® Tissue XS (Cat. no. 740901.50, Machery-Nagel, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify the partial sequence of the mitochondrial large subunit ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene in 50 μl of reaction volume using the following primers: (1) 1471 and (2) 1472 (Crandall & Fitzpatrick, Reference Crandall and Fitzpatrick1996).

The PCR reaction mixture contained 50–100 ng DNA template, 0.2 μM of each primer, 5 μl of 10 × polymerase buffer, 0.2 mM of dNTPs and 1.25 unit of Taq polymerase. PCR was performed using a thermal cycler (Thermal Cycler Dice ® Touch, TaKaRa, Japan) under the following temperature conditions: (1) initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, (2) followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, (3) annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, (4) extension at 72 °C for 1 min and (5) a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel to confirm the size and quality and then purified using the Qiaquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Cycle sequencing for the PCR products was performed using BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) under the following temperature regimes: (1) denaturation at 96 °C for 30 s, (2) annealing at 50 °C for 15 s, and (3) extension at 60 °C for 4 min. These steps were repeated for 25 cycles. Nucleotide sequences of the amplified fragments were post-purified and then evaluated with capillary electrophoresis using an ABI PRISM 3130 xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) at the Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development, Hiroshima University. All sequences were checked on the Sequence Scanner Software v2.0 (Applied Biosystems). Bases expressing ‘N’ were visually checked with the original waveforms. The nucleotide sequences of the studied species were deposited under OK575769–OK575771 through the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, USA.

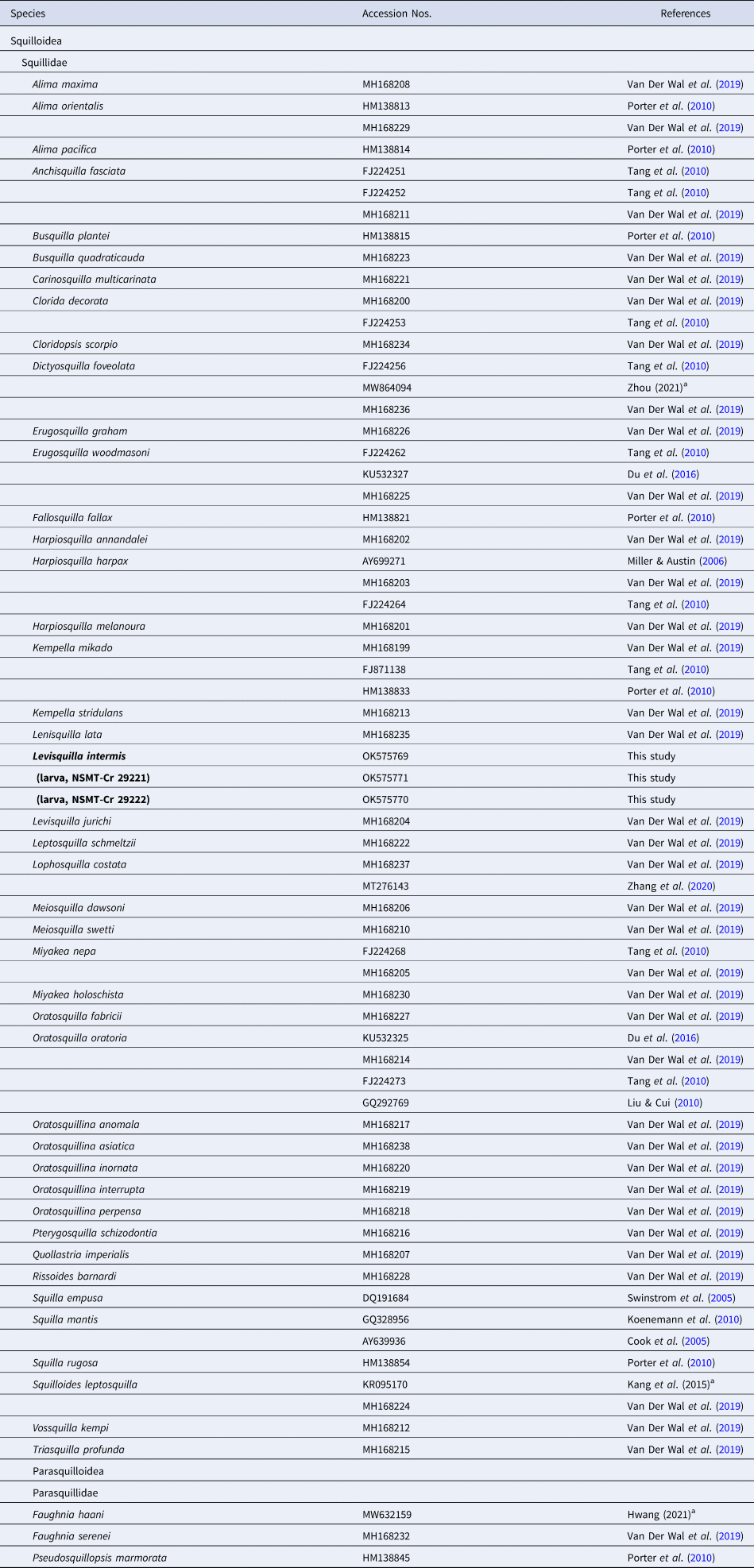

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE (Edgar, Reference Edgar2004) on MEGA 7 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016). Gblocks v.0.91b (Castresana, Reference Castresana2000) was used to eliminate divergent regions and inadequately aligned positions in the dataset; 306 positions in total were used in the final dataset. Neighbour-joining (NJ) tree with bootstrap analysis (10,000 replications) was constructed based on the Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) model (Kimura, Reference Kimura1980) using MEGA 7. The 16S rRNA gene sequences resulting from the 44 squilloid species are currently available from the GenBank, and 42 species among them were acquired for the molecular analysis (Belosquilla laevis [KR153534] formed a long branch, Cloridina moluccensis [MH168209] completely matched with Busquilla quadraticauda [MH168223]) as shown in Table 1. Up to three sequences were selected to represent a species when several different sequences were available within a species (applied to 12 species in total) in which those sequences derived from the different studies were clustered for all 12 species; thus, the terminal branch of each species was compressed in the final tree (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure S1). Three species from the superfamily Parasquilloidea were selected as the outgroups because of their close relationship to Squilloidea (Van Der Wal et al., Reference Van Der Wal, Ahyong, Ho and Lo2017, Reference Van Der Wal, Ahyong, Ho, Lins and Lo2019). The analysis involved 67 nucleotide sequences from 46 species of mantis shrimp.

Fig. 3. Neighbour-joining tree of 16S rRNA sequences of squilloid stomatopods. Branch length represents the Kimura 2-parameter distance. The terminal branches of the same species are compressed from the original tree (see Supplementary Figure S1). Bootstrap values are shown on the nodes when >50. Arrow indicates the position of the larvae examined.

Table 1. Stomatopod species and the sequence references of 16S rRNA gene used in this study

a Direct submission to GenBank.

Results

Molecular identification of stomatopod larvae

The K2P genetic distances of the 16S rRNA gene were 1% or below within species (Supplementary Table S1) except for the distances in Alima orientalis and Oratosquilla oratoria (3.7% and 0.3–1.3%, respectively) in which the greater sequence divergences were indicated (Du et al., Reference Du, Cai, Yu, Jiang, Lin, Gao and Han2016; Cheng & Sha, Reference Cheng and Sha2017; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021).

The constructed phylogenetic tree (Figure 3) placed the two larval individuals with the adult sequence of Levisquilla inermis. The sequences from the two larval individuals were identical, and only one out of 306 base positions was different from the adult L. inermis specimen. The K2P genetic distance was below 0.1% among the three sequences. The larval and adult L. inermis shared the most common ancestor with Levisquilla jurichi (Makarov, Reference Makarov1979) with the K2P genetic distance of 3.4%.

Taxonomic account

SYSTEMATICS

Order STOMATOPODA Latreille, Reference Latreille1817

Suborder UNIPELTATA Latreille, 1825

Superfamily SQUILLOIDEA Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Family SQUILLIDAE Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Genus Levisquilla Manning, Reference Manning1977

Levisquilla inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965)

(Japanese name: Subesube-shako)

(Figures 1, 4, 5)

Material examined. Last larval stage, NSMT Cr-29221, 15.95 mm in TL, Seto Inland Sea, Japan, 30–40 m, 29 October 2020.

Fig. 4. Levisquilla inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965), last-stage larva: (A) body (ventral); (B) carapace (dorsal); (C) ventral view of carapace (left); (D) left antennule (dorsal); (E) left antenna (dorsal); (F) left mandible (ventral); (G) left maxillule (ventral); (H) left maxilla (ventral); (I) telson (dorsal). Scale bars: A, 5 mm; B, C, I, 1 mm; D–H, 200 μm.

Fig. 5. Levisquilla inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965), last-stage larva: (A) left first maxilliped with enlarged portion of its distal end; (B) left second maxilliped; (C) left third maxilliped; (D) left first pereiopod; (E) left first pleopod with enlarged cincinnuli; (F) left uropod (ventral). Scale bars: A, E, F, 1 mm; B, C, 0.5 mm; enlarged distal end, 300 μm; enlarged cincinnuli, 40 μm.

Description

Carapace (Figure 4A–C). Elongated; 3.83 mm in CL, 1.90 mm in CW, 3.30 mm in RL, ventral armed with 6 spinules; armed with 2 anterolateral spines extending to the base of the eyestalk, 2 posterolateral spines extending to the second pleomere, and 1 median spine on posterior margin. Posterior margin of carapace reaching thoracic somite 7.

Antennule (Figure 4D). Antennular stalk 3-segmented. First stalk segment with 4 setae, the second segment with 6 setae, and the third segment with 1 seta. Antennule with 3 setaceous flagella. Inner flagellum 9-segmented with 1 long seta on the first segment, many short setae on all segments ending with 3 terminal setae. The median flagellum 5-segmented, and end with 1 long seta. Outer flagellum with 17 aesthetascs arranged in 3-3-3-3-3-2 on inner margin.

Antenna (Figure 4E). Antennal scale with 40 plumose setae. Flagellum of antenna partially or completely divided into 14 segments.

Mandible (Figure 4F). Incisor process with 6 teeth; molar process finely serrated.

Maxillule (Figure 4G). Basal endite holding 2 sharp spines and one seta. Coxal endite with 14 marginal spines and 4 mesial spines. Apex with 2 setae.

Maxilla (Figure 4H). Partially or completely divided into 4 segments bearing 47 marginal setae and 7 mesial setae, 3-lobed endite.

First maxilliped (Figure 5A). 5-segmented with dactylus bearing 6 plumose setae and 4–5 spines; propodus holding 24 hooked setae arranged in 3 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 1 + 1, 2 mesial setae and 8 terminal setae; carpus with 21 marginal plumose setae; merus bearing 1 distal plumose seta.

Second maxilliped (Figure 5B). 5-segmented, with dactylus bearing 4 teeth on occlusal margin; propodus with 48 denticles and 3 proximal large spines on the inner margin.

Third maxilliped (Figure 4C). 5-segmented, with dactylus bearing 3 short setae; propodus with 8–9 short setae and 5 spines; carpus with 2 spines and 9 short setae.

Fourth maxilliped. 5-segmented, with dactylus bearing 2 short setae; propodus with 14 short setae and 5–6 spines; carpus with 2 spines and 7 short setae.

Fifth maxilliped. 5-segmented, dactyl with 2 short setae; propodus with 2 spines and 7–9 short setae; carpus with 2 spines and 4 short setae.

Pereiopod I (Figure 5D). Pereopods 1–3, biramous unequally; endopod unsegmented, shorter than exopod; exopod partially two segmented.

Pleopod I (Figure 5E). Biramous; endopod with 31 plumose setae, appendix interna with approximately 10 cincinnuli; exopod with 30 plumose setae; 6 gill buds.

Pleopod II. Biramous; endopod with 39 plumose setae, appendix interna with ~10 cincinnuli; exopod with 39 plumose setae; 7 gill buds.

Pleopod III. Biramous; endopod with 40 plumose setae, appendix interna with ~10 cincinnuli; exopod with 39 plumose setae; 7 gill buds.

Pleopod IV. Biramous; endopod with 45 plumose setae, appendix interna with ~10 cincinnuli; exopod with 41 plumose setae; 9 gill buds.

Pleopod V. Biramous; endopod with 38 plumose setae, appendix interna with ~14 cincinnuli; exopod with 32 plumose setae; 7 gill buds.

Uropod (Figure 5F). Protopodite terminating in 2 sharp spines, inner longer; endopodite with 10 plumose setae on distal margin; exopodite slightly longer than endopodite, basal segment of exopodite with 5–6 marginal spines and apical segment with 20 plumose setae on distal margin. Distal margin of exopod reaches over lateral tooth on telson.

Telson (Figure 4I). Well-developed with 1 submedian, 1 intermedian and 1 lateral tooth located on each side; 40 submedian denticles, 9 intermedian denticles and 1 lateral denticles.

Colouration. The whole body, except for the retinal tissue, was observed as transparent in life. Dark yellow to orange chromatophores were noticed on the mouthparts and a spot (each of which has a combination of dark yellow to orange and dark red chromatophores) was observed on each side of the basal part of the fifth pleopods. The entire specimen turned white when preserved in ethanol.

Remarks. The propodus of the second maxilliped with three basal spines; all five pleopods possessing an appendix interna with cincinnuli; the exopod of uropod longer than endopod; the telson with nine intermediate denticles.

Discussion

The K2P distance of the nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA and/or COI genes have been proposed as one of the indicators for species identification of stomatopods (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yau and Ng2010; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021). The distances to be found within the species are considered below 2–2.4% for the COI gene and below 0.91–2.1% for the 16S rRNA gene (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yau and Ng2010; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021). The present study also demonstrates that the K2P distance of 16S rRNA gene can be considered 1% or lower within the species of Squilloidea. Based on this indicator, our molecular analysis successfully assigned the two larval individuals to Levisquilla inermis with <0.1% K2P distance. The closest relative of the L. inermis clade was a congeneric species, L. jurichi, which was 3.4% K2P distance from L. inermis. The K2P distance was sufficient to conclude that the two larval individuals are different species from L. jurichi.

There are three known species in the genus Levisquilla, namely L. inermis, L. jurichi and Levisquilla minor (Jurich, Reference Jurich1904). Of these, L. inermis is the only species reported to be from Japan, including the Seto Inland Sea (Hamano, Reference Hamano1989, Reference Hamano2005; Ahyong, Reference Ahyong2012). This species is also distributed in the other East Asian countries, such as Korea and Taiwan (Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Chan and Liao2008; Hwang, Reference Hwang2019; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Ahyong and Kim2019) while L. jurichi has also been shown to occur in Korea (Hwang, Reference Hwang2019; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Ahyong and Kim2019), and a L. jurichi post-larva was recently described as the first record from Taiwan (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021). These recent records remind us of a possible appearance of L. jurichi larvae in Japanese waters even though adults of the species are not yet recorded there. However, sequences useful for DNA barcoding were available in GenBank only for L. jurichi within the genus. The addition of the sequence obtained from the adult specimen, which morphologically strongly agreed with the previous studies of L. inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965; Ahyong, Reference Ahyong2001; Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Chan and Liao2008; Ariyama et al., Reference Ariyama, Omi, Tsujimura, Wada and Kashio2014) was the key factor to clearly solving the assignment of the larvae into this species. At the same time, our results support the assignment of the Taiwanese post-larva to a group other than L. inermis even though L. inermis is the only species from which the adult phase is known in Taiwan (Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Chan and Liao2008; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021). The K2P distance between L. inermis and L. jurichi was confirmed as 3.4% in the current study, which is much greater than the distance of 1.6% (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Tsao, Tsai, Hsieh, Li, Machida and Chan2021) between their post-larva and the same sequence of L. jurichi used for the analysis in this study.

Squilloid species have a propelagic stage with four pairs of pleopods prior to entering the planktonic form of stomatopod larva known as ‘alima’ with five pairs of pleopods (Manning, Reference Manning1968; Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Haug, Haug, Martin, Olesen and Høeg2014). Some of the larvae pass through the two propelagic stages before reaching the first pelagic stage (Morgan & Provenzano, Reference Morgan and Provenzano1979). The alima is unique to Squilloidea and is characterized by a telson with four or more intermediate denticles, a propodus from the second maxilliped with three basal spines, a long eyestalk, and the exopod of the uropod longer than the endopod (Gurney, Reference Gurney1942, Reference Gurney1946; Morgan & Provenzano, Reference Morgan and Provenzano1979; Ahyong et al., Reference Ahyong, Haug, Haug, Martin, Olesen and Høeg2014; Cházaro-Olvera et al., Reference Cházaro-Olvera, Ortiz, Winfield, Robles and Torres-Cabrera2018). Studies of pelagic larvae require not only the identification of the species but also the identification of the developmental stages, which makes the process so complicated that the progress of larval biology is hampered. Indeed, the larval duration of stomatopods in the wild is not exactly known, and the number of stages for wild-caught larvae of any provided species is approximate (Pyne, Reference Pyne1972). Our descriptions reveal that several diagnostic features characterize the larvae: (1) well-developed pereiopod characterized by the exopod partially or completely 2-segmented, (2) maxilla partially or completely divided into 3 to 4 segments with a 3-lobed endite, (3) apex of maxillule elongated and holding two setae, and (4) well-developed uropod and distal margin of exopod extend over lateral tooth on the telson. Those features matched closely with the last larval stage of Oratosquilla oratoria described by Hamano & Matsuura (Reference Hamano and Matsuura1987). Thus, our larvae were assigned to the last stage.

The Seto Inland Sea, which is a semi-enclosed coastal sea in Japan, has various marine ecosystems that support a high level of meroplankton diversity. The stomatopods, which constitute one of the meroplankton communities in the Seto Inland Sea, may play a role in maintaining the pelagic food chain. It is also known that most stomatopod larvae inhabit coral reefs, and they serve as predators of small reef fishes and invertebrates in addition to serving as prey for predatory fishes, which reveal the contribution of stomatopod larvae in maintaining coral reef communities (Reaka et al., Reference Reaka, Rodgers and Kudla2008; Abinawanto et al., Reference Abinawanto, Intan, Wardhana and Bowolaksono2019). Besides that, larvae of the stomatopods provide an alternative life stage to study biodiversity. Descriptions of 12 adult stomatopods from the Seto Inland Sea have been well documented by numerous researchers (Ariyama, Reference Ariyama1997, Reference Ariyama2001, Reference Ariyama2004; Hamano, Reference Hamano2005; Ariyama et al., Reference Ariyama, Omi, Tsujimura, Wada and Kashio2014): (1) Lysiosquillina maculata (Fabricius, Reference Fabricius1793); (2) Cloridopsis scorpio (Latreille, Reference Latreille1828); (3) Anchisquilla fasciata De Haan, (Reference De Haan1833–1850); (4) Harpiosquilla harpax (De Haan (Reference De Haan1833–1850)); (5) Lophosquilla costata De Haan, (Reference De Haan1833–1850); (6) Oratosquilla oratoria De Haan, (Reference De Haan1833–1850); (7) Acanthosquilla multifasciata (Wood-Mason, Reference Wood-Mason1895); (8) Erugosquilla woodmasoni (Kemp, Reference Kemp1911); (9) Oratosquillina perpensa (Kemp, Reference Kemp1911); (10) Levisquilla inermis (Manning, Reference Manning1965); (11) Harpiosquilla melanoura Manning, Reference Manning1968; and (12) Clorida japonica (Manning, Reference Manning1978). The study of stomatopod larvae from the Seto Inland Sea has been restricted due to the lack of information for accurate taxonomic identification. The larvae of many species are yet to be identified, and the majority of work in this area has been done on the commercial Japanese mantis shrimp, Oratosquilla oratoria. Stomatopod larval life cycles usually involve several developmental stages, which are complicated to identify without extensive morphological descriptions. This study has demonstrated the capability of matching one developmental stage of our unknown larvae, obtained from the Seto Inland Sea to species with a high degree of confidence by matching their DNA sequences with the DNA barcodes of the identified adult. The results using this technique enable rapid species identification of stomatopod larvae and may encourage further studies on stomatopod larval communities from the Seto Inland Sea for which information is relatively inadequate. Furthermore, we provide some insights into the ecology of L. inermis since we found both adult and larval specimens at the same location at the same time, a finding that indicates that the Seto Inland Sea is one of the main habitats of species settlement.

In conclusion, our data strongly link the larvae to their species and confirm the occurrence of L. inermis in the Seto Inland Sea. In addition, this study demonstrates the validity of the DNA barcoding method using the 16S rRNA gene for stomatopod larvae identification from the Seto Inland Sea. Our study also reveals that morphological identification should be supported with molecular confirmation to accomplish a more accurate and legitimate result. Such a combination may encourage further taxonomic and ecological studies on stomatopod larvae.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531542100076X

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the captain and crew of the ‘TOYOSHIO MARU’ (School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University) for specimen collection, to Mr Kenta Suzuki (Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life, Hiroshima University) for his courtesy of photographing the live materials during the cruise, and Ms Chiho Hidaka (School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University) for her assistance in drawing and molecular work. Sequencing analysis was performed at the Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development, Hiroshima University.

Author contributions

AEAF was responsible for the conceptualization of the study, conceived and designed the experiments; performed the molecular work and drawing; molecular and morphological analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. SY and KW designed the collection of the specimens using the training and research vessel. SY made records of collection. KW was responsible for the conceptualization of the study, molecular analysis, supervision, wrote the manuscript, and research funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of it.

Financial support

This work was partly supported by the Promotion of Joint International Research (Fostering Joint International Research) (KAKENHI no. 17KK0157) awarded to KW.