INTRODUCTION

Most of the known marine bacteria-associated nematodes fall into two disparate taxa, Stilbonematinae with external prokaryotes and Astomonematinae with internal symbiotic prokaryotes.

Species of Stilbonematinae (Desmodorida: Desmodoridae) are very long thread-like nematodes which are especially numerous in carbonate sands of tropical shallow-water environments. They can be quickly identified even at low magnification of a binocular microscope owing to their very long and thread-like body with some swollen anterior end, and often bright snow-white appearance in reflected light. The symbiotic prokaryotes are incorporated in the slime film produced by sensory-glandular organs. These symbionts are chemolithoautotroph sulphur-oxidizing organisms which build up organic compounds by using chemical-bond energy which is released during sulphide oxidation (Ott & Novak, Reference Ott, Novak, Ryland and Tyler1989; Ott et al., Reference Ott, Novak, Schiemer, Hentschel, Nebelsick and Polz1991). Evidently, the stilbonematines live at the expense of primary chemosynthetic bacterial production, like hydrothermal tube worms (vestimentiferans) and vesicomyid bivalves. Usually, the stilbonematines live in sheltered intertidal and subtidal sediments where these nematodes are concentrated at the interface between the surface oxidized layer and the deeper anoxic sediment zone. The nematodes migrate between the upper oxygenated layer and the deeper sulphidic sediment, thus permitting the bacteria to obtain alternately the sulphur compounds (e.g. hydrogen sulphide) as electron-donor and the oxygen as electron-acceptor (Hentschel et al., Reference Hentschel, Berger, Bright, Felbeck and Ott1999). Until recently, the stilbonematines were unknown from the deep sea except for the observation by Van Gaever et al. (Reference Van Gaever, Moodley, de Beer and Vanreusel2006).

Species of Astomonematinae (Monhysterida: Siphonolaimidae) are also extremely long and slender, but in contrast to stilbonematines, they do not possess ecto- but endosymbiotic bacteria located within the body (Ott et al., Reference Ott, Rieger and Enderes1982; Giere et al., Reference Giere, Windoffer and Southward1995). Dependence of astomonematines on their prokaryote symbionts is even more obvious because these nematodes lack a mouth, and their pharynx is vestigial—hence food uptake via the mouth is precluded. Like stilbonematines, the astomonematines are usually associated with reduced conditions such as intertidal subsurface sulphide-enriched sediment layers (Ott et al., Reference Ott, Rieger and Enderes1982) or sublittoral methane seepages (Austen et al., Reference Austen, Warwick and Ryan1993). Very recently astomonematines have been reported from the deep-sea, in canyons along the continental margin of the western north-east Atlantic (Ingels et al., Reference Ingels, Kiriakoulakis, Wolff and Vanreusel2009, Reference Ingels, Tchesunov and Vanreusel2011a, Reference Ingels, Billett, Wolff, Kiriakoulakis and Vanreuselb). According to 16S rRNA-based analysis, the ectosymbionts of the stilbonematines Laxus oneistus, and Robbea spp., together with the endosymbionts of astomonematines Astomonema sp. (Bahamas) form a cluster with known sulphur-oxidizing internal bacterial symbionts of the marine gutless oligochaetes Inanidrilus and Olavius spp. (Musat et al., Reference Musat, Giere, Gieseke, Thiermann, Amann and Dubilier2007; Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Heindl, Rinke, Lücker, Ott and Bulgheresi2009). All the astomonematine species hitherto known were not recorded beyond shelf seas.

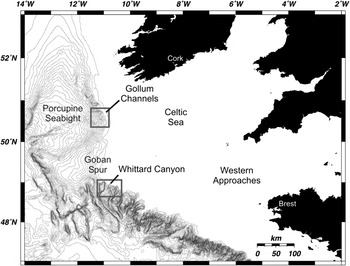

Two bacteria-carrying nematode species of two families were discovered in relatively large quantities in an unusual habitat, bathyal soft sediments of the Gollum Channels and Whittard Canyon, which incise the continental slopes of the Celtic Sea, north-eastern Atlantic (Figure 1). Canyons and channels are pervasive hydrogeological structures crossing continental and island margins in all oceans (De Leo et al., Reference De Leo, Smith, Rowden, Bowden and Clark2010; Harris & Whiteway, Reference Harris and Whiteway2011) and represent conduits for the transport of sediments and organic matter from shelf areas to the abyssal plains through entrainment by various hydrodynamic and sedimentary processes. At the same time, canyons and channels are often sites of enhanced organic matter accumulation with high rates of localized sediment deposition and subsequent degradation of organic matter. In addition to high, but possibly patchy productivity, heterogeneity and disturbance may act to increase total biodiversity observed in canyon and channel systems (McClain & Barry, Reference McClain and Barry2010). Generally, population density, biomass, and metabolic activity of meiobenthos are positively correlated with levels and lability of organic matter reaching the sea floor (Soltwedel, Reference Soltwedel2000; Mokievsky et al., Reference Mokievsky, Udalov and Azovskii2007). The great amounts and quality of bio-available organic matter in canyons compared to the adjacent slopes therefore translates in high nematode abundance and may result in increased diversity (Ingels et al., Reference Ingels, Kiriakoulakis, Wolff and Vanreusel2009, Reference Ingels, Tchesunov and Vanreusel2011a).

Fig. 1. North-east Atlantic, continental slope canyons and localities of bacteria-associated nematodes.

Both canyon/channel systems are situated at the Celtic Margin, a highly productive area where surface primary production supplies deep-sea sediments with significant levels of organic matter (Lampitt et al., Reference Lampitt, Raine, Billett and Rice1995; Longhurst et al., Reference Longhurst, Sathyendranath, Platt and Caverhill1995). Both the Gollum Channels and Whittard Canyon are characterized by relatively high meiofauna abundance (1054–1426 ind. 10−2 cm) and very high nematode diversity (181 genera in total) (Ingels et al., Reference Ingels, Tchesunov and Vanreusel2011a). Biogeochemical patterns in the sediment and the presence of nematodes associated with symbiotic bacteria suggest the presence of localized reduced nematode biomes in these ecosystems.

In this study, we taxonomically describe two disparate bacteria-associated nematode species abundant in the Gollum Channels and Whittard Canyon. One of these species is new for science and presents a new genus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Meiofauna samples were taken in the Gollum Channel system and Whittard Canyon (Figure 1), two bathyal canyon/channel areas along the Celtic Margin in the north-east Atlantic during the ‘Belgica’ cruise 2006/13, June 23–29 2006 (Ingels et al., Reference Ingels, Van Rooij and Vanreusel2006). The samples were taken with a Bowers and Connely Midicorer allowing the collection of sediment cores with intact stratification and an undisturbed sediment–water interface. Stations were sampled at 755 m and 1090 m depth in the Gollum Channels (G700, G1000, respectively), and at 762 m and 1160 m depth in the Whittard Canyon (WH700, WH1000, respectively). For exact coordinates and further ecological information about the sampling sites, we refer to Ingels et al. (Reference Ingels, Van Rooij and Vanreusel2006) and Ingels et al. (Reference Ingels, Tchesunov and Vanreusel2011a). Sediment samples were fixed with 4% buffered formalin and then sifted through sieves with mesh size 1000 and 32 µm and stained with Bengal pink. Meiofauna was elutriated by LUDOX centrifugation (Heip et al., Reference Heip, Vincx and Vranken1985; Vincx, Reference Vincx and Hall1996).

Nematodes were transferred using the formalin–ethanol–glycerin technique (Vincx, Reference Vincx and Hall1996) and mounted on permanent glycerin slides with paraffin ring. Identification, measurements, photography, and drawings were conducted with a compound microscope Olympus BX51 equipped with DIC. Specimens chosen for scanning electron microscopy were processed with a critical point dryer, covered with a mixture of platinum and palladium and studied with the scanning microscope Hitachi S-405A (Tokyo, Japan) at 15 kV voltage.

Abbreviations used:

a, body length divided by maximum body diameter;

am.w., width of the amphideal fovea, in μm;

am.w., %, width of the amphideal fovea, expressed as a percentage of the corresponding body diameter, in %;

b, body length divided by pharyngeal length;

c, body length divided by tail length;

c', tail length, expressed in anal diameters;

c.b.d., corresponding body diameter;

CV, coefficient of variation, in %;

diam.am., body diameter at the level of amphids, in μm;

diam.ani, anal body diameter, in μm;

diam.ca., body diameter at the level of cardia, in μm;

diam.c.s., body diameter at the level of cephalic setae, in μm;

diam.midb., midbody diameter, in μm;

diam.n.r., body diameter at the level of nerve ring, in μm;

dis.am., distance from the cephalic apex to the anterior rim of the amphideal fovea, in μm;

gub.ap., length of the dorso-caudal apophysis of the gubernaculum, in μm;

gub.l., length of the gubernaculum measured along the spiculum, in μm;

L, body length, in μm;

SD, standard deviation;

spic.arc, spicule's length along the arch, in μm;

spic.ch., spicule's length along the chord, in μm;

V, distance of vulva from anterior end as percentage of body length, in %

A comprehensive taxonomic review of Stilbonematinae will be done separately (Tchesunov, unpublished data).

Genus Parabostrichus Tchesunov, Ingels & Popova gen. nov.

DIAGNOSIS

Stilbonematinae. Cuticle with very faint or sometimes even indiscernible annulations. Head cuticle not thickened and not modified, annulations of the cuticle starts from the apex. Amphideal fovea situated laterally, large, spirally coiled, but obscure because its cuticular margin is smoothed. Buccal cavity not developed. Anterior region of the pharynx slightly widened and not separated distinctly from the narrow median region; small posterior bulb. No thorn-like setae on the anterior and posterior body. Gubernaculum with a dorso-caudal apophysis. In males, short conical projections with apical papillae on the tail. Body covered with elongate symbiotic bacteria.

TYPE SPECIES

Parabostrichus bathyalis sp. nov.; present paper. No other species.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Parabostrichus gen. nov. is related to the genus Eubostrichus Greeff, 1869 in body shape, position and shape of the amphideal fovea, absence of a differentiated buccal cavity, and similar shape of the pharynx with an anterior muscular part of the pharynx gradually turning to the narrow median part and even in having similar-shaped elongate crescent-like ectosymbionts. However, Parabostrichus differs from Eubostrichus by the presence of well-developed dorso-caudal apophyses of the gubernaculum, elongate–conical tail with attenuated distal portion and papilloid hillocks with minute apical papillae.

Parabostrichus bathyalis sp. nov. differs from Eubostrichus species by lacking strong, paired, thorn-like setae in the pre- and post-cloacal region that are referred to as porids by Hopper & Cefalu (Reference Hopper and Cefalu1973) (porids are tubular setae functioning as outlets for glands as defined by Cobb, Reference Cobb1925). Instead of porids, Parabostrichus bathyalis exhibits three pairs of conical hillocks with small papillae in the post- and precloacal region of males. Only the males of Eubostrichus parasitiferus sensu Gerlach (Reference Gerlach1963) are reported to have one pre- and two postanal papillae with short apical setae on an elevated base, resembling the structures found on P. bathyalis sp. nov. However, E. parasitiferus sensu Gerlach (Reference Gerlach1963) also exhibits terminal porids, and its tail is shorter, ending bluntly and not tapered at the posterior end compared to P. bathyalis sp. nov.

Within Stilbonematinae, there are three other genera that exhibit dorso-caudal apophyses of gubernaculum, i.e. Adelphos Ott, 1997, Catanema Cobb, 1920 and Robbea Gerlach, 1956. Parabostrichus is distinguished from Adelphos by absence of prominent cervical thorn-like setae and thorn-like caudal setae; from Catanema by large lateral amphideal fovea and muscular procorpus of the pharynx gradually turning in the narrow median isthmus, and absence of strong thorn-like setae on the tail; from Robbea by gradual transition from anterior muscular procorpus to the median narrow isthmus and longer tail with narrow terminal part.

ETYMOLOGY

The generic name is formed of Para- (near) and –bostrichus (grammatical root of ‘Eubostrichus’) and refers to related genus Eubostrichus.

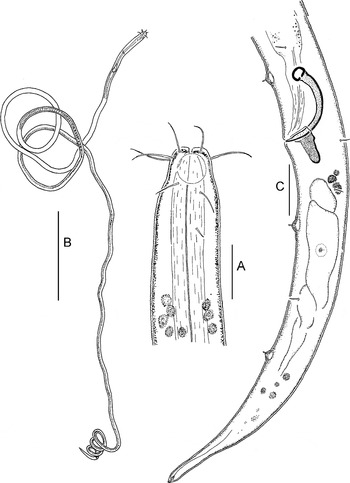

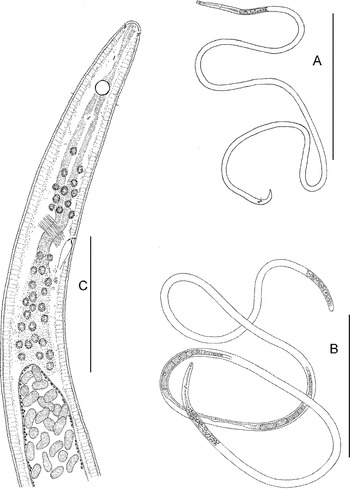

Fig. 2. Parabostrichus bathyalis gen. nov., sp. nov, holotype male: (A) cephalic end; (B) entire; (C) tail. Scale bars: A & C, 10 µm; B, 200 µm.

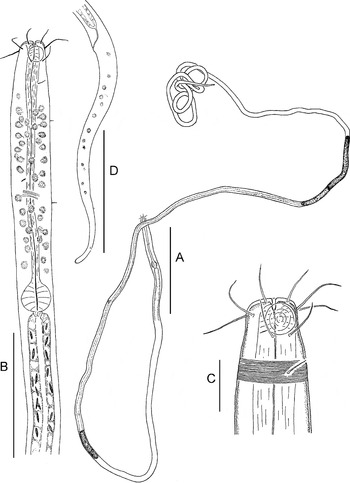

Fig. 3. Parabostrichus bathyalis gen. nov., sp. nov., paratype female. (A) entire; (B) anterior body; (C) cephalic end; (D) tail. Scale bars: A, 200 µm; B & D, 50 µm; C, 10 µm.

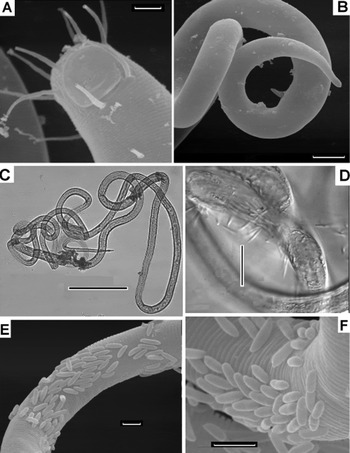

Fig. 4. Parabostrichus bathyalis gen. nov., sp. nov., scanning electon microscopy (A, B, E & F) and optical microscopy (C & D) pictures: (A) cephalic end; (B) male tail; (C) female, entire; (D–F) parts of body with bacteria. Scale bars: A, E & F, 3 µm; B, 10 µm; C, 200 µm.

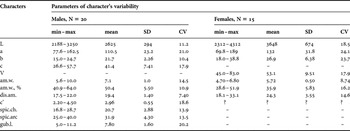

Table 1. Morphometrics of Parabostrichus bathyalis sp. nov.

min, minimum; max, maximum.

ETYMOLOGY

The specific epithet is derived from the Greek bathos, meaning deep, and refers to the depths at which the species was found.

TYPE MATERIAL

Holotype male, one paratype male and four paratype females collected in the Gollum Channels; nine paratype males and three paratype females collected in Whittard Canyon.

Holotype male (inventory No. UGMD 104115), paratype male and paratype female (inventory No. UGMD 104116) are deposited in Ghent University's Museum voor Dierkunde, Ghent, Belgium. Other paratype specimens are deposited in the Nematological collection of the Center of Parasitology of A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia.

TYPE LOCALITY

North-east Atlantic Ocean, continental slope Celtic Margin, Gollum Channels at 1085–1094 m depth (50°43.8′N and 11°15.5′W).

DESCRIPTION

Body extremely long and slim, truly filiform, as a very thin thread. The anterior-most body is slightly swollen and a bit wider than the body posteriad. Cuticle very thin and slightly refractory. Very fine transversal annulation throughout the body, barely discernible in some regions. The anterior head cuticle seems to be smooth from the apex to the posterior margin of the amphideal fovea.

Somatic cuticle slightly widened apically. Mouth opening small. Inner labial and outer labial sensilla not seen. Four thin and relatively long cephalic setae inserted around the apex edge. There are four slightly longer subcephalic setae: two subdorsal and two subventral setae nearly at the same circular position of the four cephalic setae but slightly posterior to them. Two lateral post-amphideal setae are situated immediately after the posterior edge of the amphideal fovea. One or two lateral cervical setae are disposed further posterior to the amphideal fovea. A few small somatic setae are distributed in the pharyngeal region and even more sparsely further along the body. In males, cephalic setae 6–7 µm, subcephalic setae 7.5–10 µm, postamphideal setae about 8 µm, cervical setae 3–4 µm, somatic setae 1–2 µm long. The same setae in females measure 6–8 µm, 9–10 µm, 7–11 µm, 3–4 µm and 1–2 µm, respectively.

Amphideal fovea or corpus gelatum hardly or not visible as such because of an indistinct cuticular rim. Large round amphideal fovea situated close to the cephalic apex; ventral spiralization not evident but very fine circular discontinuous striation visible. In males, the rim of the amphideal fovea is too obscure to report exact dimensions, fovea's width is approximately 5–6 µm (60–70% c.b.d). In females, width of the amphideal fovea is 6.5 µm (65% c.b.d.), situated 1.5 µm posterior to the apex.

Apical cuticle is thickened around the mouth opening. Cheilostom tiny, without any visible indication of rugae. Pharyngostom minute, conical, with slightly sclerotized walls, without any armament. Pharynx relatively very short, wide in the cephalic region, then gradually narrowing towards the longer, slim median region, terminating in a small and compact spherical posterior bulb. Interior cuticular lining well discernible along the entire pharynx; transversal muscular striation well pronounced in the bulb. Nerve ring in the middle of the slim median region of the pharynx. Cardia obscure. Midgut with more or less visible internal lumen, empty in all specimens. Anterior pregonadal midgut contains homogene fusiform bodies (inclusions?) about 4 × 1 µm in size, seemingly located in the lumen as well as inside the intestinal cells.

Female reproductive system didelphic, consisting of two antidromously reflected gonads. Vulva is positioned significantly anterior to the midbody.

Male gonad single, anterior, its position relative to the midgut hardly determinable. Spicules equal, short, strongly arched, with rounded knob at anterior end and sharp posterior tip. Gubernaculum with paired, wide, weakly sclerotized, dorso-caudal apophyses. Three subventral pairs of conical hillocks with small apical papillae on the posterior body, one pair preanal and two pairs postanal.

In males, tail elongate and conical, of which posterior ~15% is tapered. There is a small conical spinneret at the tail tip and caudal glands are present within the tail. There are quite a few small preanal and postanal setae.

In females, tail long, slim, elongate conical. Somewhat like a terminal spinneret present on the tail tip, but no caudal glands within the tail discernible.

SYMBIONTS

The body is covered by a very friable layer (aggregations) of rod-shaped, slightly curved bacterial cells 5–13 µm long. On the host cuticle, the elongate cells are mostly arranged along the axis of the host's body. Some cells are in state of division. The bacterial cells are weakly attached to the host's cuticle and fall off very easily; bacteria are almost absent on some nematode specimens, possibly because of loss during sample processing.

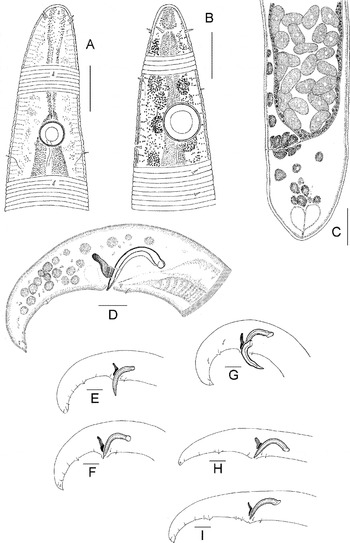

Fig. 5. Astomonema southwardorum, entire and anterior body: (A) male, entire; (B) female, entire; (C) anterior body of a female. Scale bars: A & B, 500 µm; C, 50 µm.

Fig. 6. Astomonema southwardorum, details: (A) cephalic end of a female; (B) cephalic end of a male; (C) healed rupture (stump) of the posterior body end of a female; (D) male tail; (E–I) position of papillae on male tails. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Fig. 7. Astomonema southwardorum, younger juvenile stage (possible J1): (A) entire; (B) anterior body; (C) cephalic end; (D) posterior body. Scale bars: A, 200 µm; B, 50 µm; C & D, 10 µm.

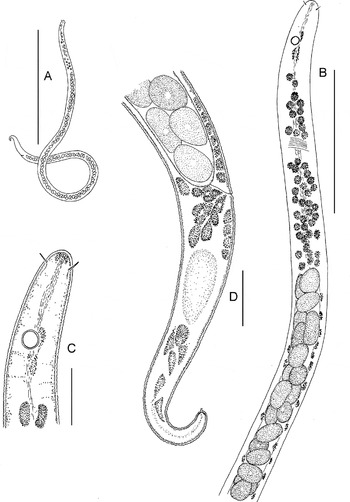

Fig. 8. Astomonema southwardorum, scanning electron microscopy (A–D & F) and optical microscopy (E) pictures: (A) cephalic end; (B) apical region; (C & D) broken body with endosymbiotic cells jutted out; (E) part of body filled with endosymbionts; (F) stump of the posterior body end. Scale bar: 3 µm.

Table 2. Morphometrics of Astomonema southwardorum.

min, minimum; max, maximum.

MATERIAL

Forty-four specimens from Whittard Canyon (17 males + 12 females + 15 juveniles) and six specimens from Gollum Channel (three males +three females) were observed microscopically and measured. Since populations from the two sites did not show any differences from one another, all the specimens were treated together (Table 2). All the specimens depicted on Figures 5–8 were collected in the Whittard Canyon.

ADULTS

Body very long, slender, cylindrical thread-like. Cuticle distinctly annulated; annulations start at the level of the cephalic setae and continue to the tail tip. The annules are wider in the anterior body down to the beginning of the intestine (6–7 annules per 10 µm), then narrower further posteriad in the middle and posterior body (up to 15 annules per 10 µm), where they can become less clear and discernible. Cuticle is thicker anteriorly, from the cervical region to the anterior third of the intestinal region (1.5 µm), and becomes thinner further posteriad in the middle and posterior body (~0.8 µm). No lateral differentiation of the cuticle.

No indication of mouth opening apically. Pattern of anterior sensilla 0 + 6 + 4. No inner labial sensilla. Both outer labial and cephalic sensilla comprise short conical setae 1–1.3 µm long. Lateral setae are a bit shorter and situated slightly anterior to the lateromedian setae of the outer labial sensilla.

Amphideal fovea perfectly round, with slightly discernible circular central spot and distinct cuticular rim. Amphideal nerve runs out from under the amphideal fovea postero-dorsally. Amphideal fovea is slightly bigger in males than in females.

There are a few lateral and submedian, small (<1 µm long) conical papillae in the cervical region. Somatic papillae are very sparse and hardly found in the intestinal region.

Anterior pharynx is an indistinctly shaped string without muscular striation, but the internal lumen may be discernible in some specimens. Middle pharynx in the region of the nerve ring is more definite, slightly narrowed and curved; internal lumen may be visible in some specimens. Postneural pharynx is obscure, particularly because it is surrounded by numerous cell bodies. Cardia not seen.

Midgut with thin stretched walls and voluminous internal lumen filled densely with prokaryote symbionts. Ventral pore and ampula at the level of the nerve ring are visible in some specimens; body of the ventral gland cell is not clear.

Ovaries paired, outstretched, can be situated at either left or right side of the intestine. There are no females with fertilized eggs in the uteri in the collection. A chamber within the proximal female branch contains numerous oval spermatozoa 3–4 × 2–3 µm with small nuclei densely stained with Bengal pink.

Male gonads are paired, slender; anterior outstretched testis is longer, posterior reflected testis is notably smaller. Position of the testes relative to the intestine: both anterior and posterior gonads to the right (three males) or to the left (two males); anterior gonad to the left and posterior gonad to the right (one male); anterior gonad to the right and posterior gonad to the left (one male). In some specimens both testes are very difficult to discern. Vas deferens with coarse granular walls, uniform throughout its length. There are two visible ejaculatory gland cell bodies at both lateral sides.

Spicules relatively short, arcuate, distally beak-like pointed, proximally widened and slightly knobbed. Gubernaculum with paired dorso-caudal apophyses rising from basal sclerotized trough; thin plates coming down from the troughs engulfing spicules laterally.

Male tail conical and ventrally bent. Caudal glands are not seen as such, but a thin internal duct can be visible within the small terminus. Male posterior region is equipped with a set of sensilla: (1) one short midventral preanal seta; (2) one pair of small lateroventral preanal papillae; (3) five to eight pairs of subventral postanal papillae; one of them more prominent, situated in the middle of tail is resting on a convex hillock; and (4) two pairs of small subterminal papillae: one pair subventral and another subdorsal.

There are no adult females with normal conical tail found in the collection. Posterior body ends of all the females are blunted anterior to the original anus.

JUVENILES

The youngest juveniles, less than 1 mm in body length, are characterized by a relatively short and stout cylindrical body, only four cephalic setae which are relatively longer and thinner than those of the adults, the apparent absence of other anterior and somatic setae/papillae, and a relatively longer conical tail with a terminal spinneret. Mouth opening is absent, and pharynx comprises an unclear string unlikely to differ significantly from that of adults.

SYMBIONTS

Cells of the bacterial symbionts in adult nematodes are very large (sized 7–10 × 3–5 µm) and shaped from spherical over ovoid to elongate sausage-like. Content of the cells is very finely granular with minute transparent vacuoles and a light homogeneous area in the centre. The cells have filled the gut lumen very densely, without any regular arrangement. No cell divisions are detected.

In younger juveniles, the bacterial symbionts are even bigger reaching 15 × 6 µm in size and arranged in two rows in the lumen of the thinner gut.

REMARKS ON TAXONOMY OF ASTOMONEMATINAE

Two genera of mouthless nematodes, Astomonema Ott et al. Reference Ott, Rieger and Enderes1982 and Parastomonema Kito Reference Kito1989 have been established in the subfamily Astomonematinae Kito & Aryuthaka Reference Kito and Aryuthaka2006 within the family Siphonolaimidae Filipjev 1918 (see Kito & Aryuthaka, Reference Kito and Aryuthaka2006). The taxon Astomonematinae is characterized by lack of mouth opening and vestigial pharynx and the presence of a modified midgut, which is transformed into a repository of extracellular prokaryote microorganisms (intracellular prokaryote symbionts in the case of Astomonema jenneri (Giere et al., Reference Giere, Windoffer and Southward1995)). Differences between Astomonema and Parastomonema are not evident. Kito (Reference Kito1989) originally distinguished Parastomonema from Astomonema based on different patterns of anterior sensilla (0 + 0 + 4 versus 0 + 6 + 4) and paired versus unpaired male gonads. Later, Kito & Aryuthaka (Reference Kito and Aryuthaka2006) described Parastomonema papillosum with an anterior sensilla pattern of 0 + 6 + 4 and paired testes, thus having reduced the difference between the two genera to the number of male gonads: one testis in Astomonema and two testes in Parastomonema (Kito & Aryuthaka, Reference Kito and Aryuthaka2006). Furthermore, according to our observations (see above), pattern of anterior sensilla 0 + 0 + 4 in juveniles precedes to 0 + 6 + 4 in adults of Astomonema southwardorum. Further, the number of male gonads is often very difficult to determine. In our deep-sea specimens from the canyon/channel areas, the smaller posterior testis is not discernible in all specimens and is often poorly visible under the light microscope. These observations render the number of male gonads unreliable as a diagnostic feature for discriminating between these two genera. Our deep-sea species conforms to Astomonema southwardorum Austen et al. Reference Austen, Warwick and Ryan1993 in the metric parameters as well as in the pattern of male pericloacal sensilla. However, Austen et al. (Reference Austen, Warwick and Ryan1993) reported the presence of only the anterior outstretched testis. Considering the dubious nature of male gonad morphology as a diagnostic feature, the validity of the genus Parastomonema within the subfamily Astomonematinae is to be questioned and type specimens need to be re-investigated for diagnostic characteristics. The subfamily Astomonematinae and both Astomonema and Parastomonema are therefore in need of revision (Tchesunov et al., in preparation).

ECOLOGY OF PARABOSTRICHUS BATHYALIS SP. NOV. AND ASTOMONEMA SOUTHWARDORUM

Most stilbonematine species are known as hosts of ectosymbiotic chemoautotrophic sulphur-oxidizing bacteria. The symbionts utilize energy obtained from oxidation of reduced sulphur compounds (usually sulphides) for fixation of CO2 and synthesizing organic compounds (Ott et al., Reference Ott, Bright and Bulgheresi2004a, Reference Ott, Bright and Bulgheresib). These organic compounds end up in the host nematode, but the pathway by which this occurs is not fully understood. Since the stilbonematine nematodes are provided with a small mouth opening and a normal alimentary tract consisting of pharynx, midgut and rectum, it is believed that the nematodes can receive the bacterial organic matter by scraping away and swallowing bacterial cells from their cuticle (e.g. ingested bacteria were documented by Riemann et al., Reference Riemann, Thiermann and Bock2003 for species of Leptonemella). However, we failed to find symbiotic cells in the intestine lumen of Parabostrichus bathyalis. It may be possible that the host nematode can obtain nutrients as dissolved metabolic products and not by direct consumption of the ectosymbiotic bacterial cells. Hentschel et al. (Reference Hentschel, Berger, Bright, Felbeck and Ott1999) suggested that the bacterial coat may also function as a protective layer against toxic hydrogen sulphide.

Most stilbonematine species live in sheltered intertidal and upper subtidal sulphide sediments, and particularly at the interface between the surface oxidized layer and the deeper anoxic sediment, where the stilbonematines migrate around the oxic/sulphidic chemocline thus using both microbiotopes, like other thiobiotic bacteria-symbiotic worms (Giere, Reference Giere2009). The symbiotic bacteria can attain reduced sulphur compounds whilst residing in the sulphidic layer and gain energy from the oxidation of the reduced sulphur when their host nematode brings them into the oxic layer, where they have access to oxygen as electron acceptor (Schiemer et al., Reference Schiemer, Novak and Ott1990). Their long filiform body may help in covering the distance between oxygenated and sulphidic sediment layers—both oxygen and sulphide compounds are needed to maintain the metabolic activities of the symbiotic bacteria.

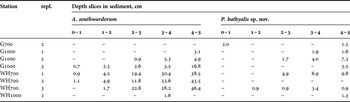

Higher diversity and abundance of stilbonematines have been encountered in shallow tropical and subtropical calcareous sediments characterized by spatial complexity of the interface between oxidized and reduced layers (Ott & Novak, Reference Ott, Novak, Ryland and Tyler1989). The first observation of stilbonematine genera in the deep sea was reported recently by Van Gaever et al. (Reference Van Gaever, Moodley, de Beer and Vanreusel2006), whereby the genera Leptonemella, Eubostrichus and Catanema, characterized by ectosymbionts, were dominant in subsurface sediments at the Darwin Mounds (north-east Atlantic) suggesting the presence of anoxic micro-environments. The related species Desmodora masira (Desmodoridae: Desmodorinae), also housing ectosymbiotic bacteria, was found abundant in a reduced biotope in the deep sea off California (Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Buck, Farmer and Bowser2000). An understanding of the precise environmental conditions and biogeochemical patterns in the sediments home to Parabostrichus bathyalis gen. nov., sp. nov. in the canyon/channel systems in the north-east Atlantic is incomplete and empirical investigations of the reduced conditions in these systems are ongoing. The occurrence of P. bathyalis sp. nov. mainly in the deeper layers (Table 3) confirms the general assumption of reduced oxygen content and increased sulphide concentrations with increasing sediment depth.

Table 3. Percentage contribution of Astomonema southwardorum and Parabostrichus bathyalis sp. nov. to the nematode community in various sites and depths in sediment columns. For more detailed station information, we refer to Ingels et al. (Reference Ingels, Tchesunov and Vanreusel2011a). ‘-’ indicates absence; repl. means number of replicated deployment.

Astomonema species lack a mouth opening and a normally functioning intestine and evidently feed at the expense of their symbiotic bacteria (ultrastructural aspects documented by Giere et al., Reference Giere, Windoffer and Southward1995). Clarification of the phylogenetic interrelations and detection of the gene aprA, typical for sulphur-oxidizing bacteria, indicate that symbionts of Astomonema species use reduced sulphur-compounds as a source of energy for their hosts (Musat et al., Reference Musat, Giere, Gieseke, Thiermann, Amann and Dubilier2007). Astomonema and Parastomonema species are consequently well known with respect to their ecology and their association with various reduced conditions: Astomonema southwardorum recovered from a methane seep pockmark at 150–170 m water depth in the North Sea (Austen et al., Reference Austen, Warwick and Ryan1993); Astomonema jenneri dwells in oxygen-deficient sediment-layers in the intertidal zone of North Carolina (Ott et al., Reference Ott, Rieger and Enderes1982); Astomonema sp. lives in subsurface layers of intertidal sandy sediments of the Bahamas (Musat et al., Reference Musat, Giere, Gieseke, Thiermann, Amann and Dubilier2007); and Parastomonema papillosum has been found in sandy subsurface layers in mangroves of Thailand and Vietnam (Kito & Aryuthaka, Reference Kito and Aryuthaka2006; own data). In the deep sea, astomonematines have only recently been discovered, in canyons along the north-east Atlantic Margin (Ingels et al., Reference Ingels, Kiriakoulakis, Wolff and Vanreusel2009, Reference Ingels, Tchesunov and Vanreusel2011a, Reference Ingels, Billett, Wolff, Kiriakoulakis and Vanreuselb). As suggested for stilbonematine species, their long filiform habitus may facilitate covering the distance between oxidized and sulphidic sediment layers. Like for Parabostrichus bathyalis sp. nov., A. southwardorum occurs in higher densities deeper in the sediment (up to 46.4% of the deep-sediment community: Table 3).

High population densities of Astomonema southwardorum and Parabostrichus bathyalis sp. nov. both associated with prokaryotic symbionts suggests the presence of reduced conditions in localized, and very likely patchy, areas in the Gollum Channels and Whittard Canyon in the north-east Atlantic (Table 3)—caused either by accumulation and burial of dead organic matter collected in the canyon's channels or even seep activity. The prevalence of Parabostrichus, Astomomonema and other genera associated with symbiotic prokaryotes in sediments not recognized as chemosynthetic environments suggest a substantial ecological role for chemoautotrophic fauna in non-seep sediments, but further biogeochemical and faunal investigations of the environment are required to establish the precise nature of these sediments and the biogeochemical processes that occur there.

LOSS OF THE HINDBODY IN ASTOMONEMA SOUTHWARDORUM

Bodies of all adult females and many elder juveniles of Astomonema southwardorum are shortened because the hind part of the body is lost (Figure 5B). None of the adult females possess a normal conical tail terminating with a spinneret and caudal glands; only few specimens have an anal opening with a rectum (or their substitutes). Rupture of the body can be found at any point between anus and vulva, which translates in an abnormally wide range of variability and high mean CV of the body length and the relative position of the vulva. If rupture occurred just behind the vulva, then the posterior ovary was lacking while the anterior ovary was developed normally—these females had become monodelphic.

There were specimens at various stages of forming a new cuticle around the wounds or ruptures in the collection indicating a healing process. Bodies of freshly damaged specimens were merely torn: fringes of wounds were rough, somatic cuticle was ragged, and cytoplasm with its inclusions squeezed out from broken cells. In a next stage, the wound had shrunk strongly leading to a small opening, if one at all and the somatic cuticle were pulled together by radial folds (Figure 8E). A last stage of wound healing was represented by the presence of a convex, rounded stump covered with newly formed cuticle (Figure 6C). This cuticle is relatively thick, transparent and looks quite homogeneous (i.e. stratification not pronounced) under light microscope and the external surface of this cuticle is smooth. The intestine is closed at this stage, also as a stump. In some specimens, a thin string or duct descends from the gut stump; representing a substitute for the rectum.

Reasons for this phenomenon are unclear, but a plausible explanation may be that specimens have survived an attack of an unknown predator which was contented with a torn hind body from the prey nematode. Accidental predation by means of megafaunal deposit-feeding processes are unlikely to cause the hindbody loss—the whole animal would be consumed because of the lack of feeding selectivity directed at nematode preys—but targeted macrofaunal predation may be possible. Unfortunately, there is no information available on macrofauna communities in the study areas. The most likely explanatory scenario, however, is that of large nematodes preying on the Astomonema individuals. Based on data from Ingels et al. (Reference Ingels, Tchesunov and Vanreusel2011a), the most prevalent predator nematodes are Syringolaimus, Halichoanolaimus and Metasphaerolaimus. Occasional sightings of Metasphaerolaimus buccal structures in the guts of Metasphaerolaimus individuals reveal their predator nature (Ingels, personal observation), but only extensive and time-consuming gut content analysis for Astomonema body parts may offer an answer to this question. In the case of an unsuccessful attack, a female cannot only survive but also reproduce as indicated by the leftover anterior female gonad branch which looks normal and contains ripe oocytes and spermatozoa. The observation that the cuticle seems thinner and more fragile in the hind body region compared to the anterior part may facilitate lesion and increase chances of a predator escape. However, we found no males with broken and healed posterior body.

Loss of body parts and healing of wounds have been mentioned several times for Astomonematinae (Ott et al., Reference Ott, Rieger and Enderes1982; Austen et al., Reference Austen, Warwick and Ryan1993; Kito & Aryuthaka, Reference Kito and Aryuthaka2006) and Siphonolaimus (e.g. Vitiello, Reference Vitiello1970; Ott, Reference Ott1972) as well as within the family Linhomoeidae, which is related to the Siphonolaimidae. Juvenile stages of some Megadesmolaimus species possess a normal tail with terminal swelling and spinneret while the tail of adult females shows rupture more or less at the tip, thus turning into a malformed stump whereby the spinneret has disappeared (Tchesunov, Reference Tchesunov1986). This process has been recognized and sequenced in one of the Paralinhomoeus species: in juvenile stages, the tail consists of an anterior conical part and distinctly cylindrical-shaped posterior part, while in adults the slender cylindrical portion had fallen off precisely at the point of constriction between both parts (Hendelberg, Reference Hendelberg1977). In the case of A. southwardorum, however, a considerable fragment of the hind body had disappeared, not only part of the tail.

It is known that somatic cells of nematodes almost do not divide, at least in adults (Bird & Bird, Reference Bird and Bird1991). This relates to the commonly assumed inability of nematodes to regenerate lost body parts and wound healing. However, wound healing and regeneration may be possible to an extent for certain species. Korotkova & Agafonova (Reference Korotkova and Agafonova1976) have shown that cell mitoses commence in the epithelium in the case of damaged midguts of Pontonema vulgare (Oncholaimidae), whereby the intestine regenerates within six days after injury if the body wall had not broken. There are even some fragmentary observations of a recovery of the body wall after rupture. Bongers (Reference Bongers1983) reported on an extraordinary case of wound healing in Leptosomatum bacillatum (Leptosomatidae). A newly hatched juvenile had lost about 60% of hind body; wounds of the intestine and body wall healed and were perfectly closed again.

Common loss of the hind body and wound healing to the extent found in Astomonema southwardorum is a phenomenon with possibly important ecological implications and requires further investigation at the histological/ultrastructural and if possible molecular level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A.V.T. and E.V.P. would like to thank the Russian Fund for Basic Research (grant No. 09-04-01212). J.I. acknowledges financial support from the EC FP7 HERMIONE project (grant No. 226354) and Professor A Vanreusel and Professor M. Vincx for the use of research facilities. We are indebted to the commander and crew of the RV ‘Belgica' for sampling operations during the ‘Belgica’ 2006/13 cruise. We are very grateful to both anonymous referees and also specially to Maria Miljutina (German Centre for Marine Biodiversity Research, Senckenberg am Meer, Wilhelmshaven, Germany) for valuable remarks on the manuscript.