INTRODUCTION

The family Bopyridae is composed of numerous subfamilies whose members are branchial or abdominal parasites of Crustacea (Markham, Reference Markham, Gore and Heck1986). The life cycle of the bopyrids typically includes the epicaridium larva, which is ectoparasite of calanoid copepods and undergoes two larval stages known as microniscus and cryptoniscus. The latter larval stage leaves the copepod in search of a decapod crustacean. The first larva reaching the branchial chamber develops as a female and the next one arriving develops as a male, which remains attached to uropods of the female (Beck, Reference Beck1980).

The interaction between bopyrids and galatheids is widely known, with the latter being the most ancient crustacean hosts as evidenced by the fossil record (Markham, Reference Markham, Gore and Heck1986). There are about 60 species of galatheids acting as hosts for bopyrids. Pseudione and ten other genera of the subfamily Pseudioninae are ectoparasites of the members of genus Munida (Román-Contreras & Boyko, Reference Román-Contreras and Bokyo2007). Prevalences of infestation with bopyrids have been reported for many squat lobsters such as M. rugosa (Fabricius, 1775) (Bourdon, Reference Bourdon1968), M. tenuimana Sars, 1872 (Mori et al., Reference Mori, Orecchia and Biagi1999), M. intermedia A. Milne-Edwards and Bouvier, 1899 (Gramito & Froglia, Reference Gramito and Froglia1998), M. longipes A. Milne-Edwards, 1880, M. iris iris A. Milne-Edwards, 1830 and M. microphtalma Milne-Edwards, 1880 (Lewis-Wenner & Windsor, Reference Lewis-Wenner and Windsor1979).

The infestation of Munida gregaria (Fabricius, 1973) by Pseudione galacanthae (Hansen, 1897) has been reported by Rayner (Reference Rayner1935). Later, it has been mentioned in various localities along the Argentine coast such as the Beagle Channel, Puerto Deseado (Miranda-Vargas & Roccatagliata, Reference Miranda-Vargas and Roccatagliata2004) and Puerto San Julián (Varisco, unpublished). Rayner (Reference Rayner1935) reported a single prevalence value for a large region in the Argentine Sea not including San Jorge Gulf. Prevalence may be affected by local conditions and seasonal variations linked to the life cycle and biology of both parasite and host (Muñoz & George-Nascimento, Reference Muñoz and George-Nascimento1999; Cañete et al., Reference Cañete, Cárdenas, Oyarzún, Plana, Palacios and Santana2008). In particular, there are no data on the prevalence of P. galacanthae in the squat lobster population in San Jorge Gulf.

Bopyrid infestation may play an important role in the regulation of some decapod populations. González & Acuña (Reference González and Acuña2004) points out that the bopyrid P. humboldtensis Pardo, Guisado, and Acuña, Reference Pardo, Guisado and Acuña1998 has a remarkable impact on commercially exploited populations of Pleuroncodes monodon (Milne-Edwards, 1837) and Cervimunida johni Porter, 1903 from northern Chile. The deleterious effects of parasite infestation on a population are reflected in high prevalence and mortality rates and in a reduction in the reproductive potential of the host (Reinhard, Reference Reinhard1956; Beck, Reference Beck1980; Astete-Espinoza & Cáceres, Reference Astete-Espinoza and Cáceres2000). Females are usually more affected than males because they have a higher reproductive investment; parasitism usually causes ovarian dysfunction and, in some decapod species, a decrease in the size of pleopods (Bourdon, Reference Bourdon1968; Mori et al., Reference Mori, Orecchia and Biagi1999). In males, parasites most often induce modifications in secondary sex characters (Reinhard, Reference Reinhard1956).

In this study, the impact of the parasite P. galacanthae on the M. gregaria population in San Jorge Gulf is investigated. For this purpose, the prevalence of the parasite was analysed in relation to sex, host size, season and water depth. The effect of infestation on the reproductive potential of the squat lobster and the relationship between host size and size and degree of development of the parasite were also analysed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and field sampling

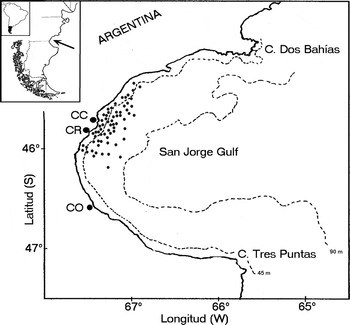

The study area encompassed the inner central shelf of San Jorge Gulf, which is the widest sea entrance along the Patagonian Atlantic coast. The gulf extends from Cape Dos Bahías in the north to Cape Tres Puntas in the south (Figure 1) with a maximum depth of approximately 100 m (Vinuesa, Reference Vinuesa2005). The convergence of sub-Antarctic waters of the Malvinas Current and warm temperate waters from the north-east result in a large ecotone of considerable biogeographical importance, lining the Patagonian coasts from 42° to 47°S approximately. Along the coastal patagonic waters was observed a minimum of salinities (S < 33.6) that represents the Patagonian current (Brandhorst & Castello, Reference Brandhorst and Castello1971), resulting from low salinity waters flow from the Magallanes Strait and Tierra del Fuego, with lateral mixing and warming of the pure sub-Antarctic waters. No coastal ‘fronts’ were described for inner waters of San Jorge Gulf (Guerrero & Piola, Reference Guerrero, Piola and Boschi1997), but no detailed studies were conducted here. Stratifications were observed in several parts of the Argentine continental platform during summer, but are unlikely to happen in the coastal area, due to the existence of macrotides and high frequency of strong winds. The coastal area off the localities of Comodoro Rivadavia and Caleta Córdova shows soft bottoms with a gentle slope. It becomes steeper at 45–55 m depth, reaching depths less than 80 m at a distance of 10 km to the coast.

Fig. 1. San Jorge Gulf, Argentina, south-western Atlantic Ocean. CR, Comodoro Rivadavia; CC, Caleta Córdova; CO, Caleta Olivia.

The squat lobsters were sporadically sampled between 1997 and 2009. They were obtained from vessels involved in the fisheries of hake, Merluccius hubbsi Marini, 1933, the southern king crab Lithodes santolla (Molina, 1782) and the Argentine red shrimp Pleoticus muelleri (Bate, 1888), operating from the harbours of Comodoro Rivadavia, Caleta Olivia and Caleta Córdova. The geographical position and depth of capture were recorded each time. Pelagic juvenile specimens were collected using a 300-μm mesh plankton net with 0.7 m of diameter of mouth from a vessel, from tidal pools and alive recently stranded on the beach in 2009. The samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde until further analysis.

Laboratory analysis

In the laboratory, adult specimens were sexed and their caparace length (CL) measured to the nearest 0.01 mm with a digital caliper. Carapace length was the distance between the posterior orbital margin and the posterior median margin. Juveniles were measured with a graduated eyepiece under a stereoscopic microscope, but only those larger than 10 mm CL were sexed. The branchial chambers of each squat lobster were examined under a stereoscopic microscope to search for bopyrids. To evaluate the effect of parasitism on male reproductive potential, the right cheliped length was measured and the gonadal development was evaluated under a stereoscopic microscope. The presence of eggs in infested females was recorded, and these were measured to the nearest 0.1 mm using a graduated eyepiece in a stereoscopic microscope.The pleopods III–V of parasitized females were measured to evaluate the effect on secondary sex characteristic. Fecundity was also determined, following the procedures described in an earlier work (Vinuesa, Reference Vinuesa2007). These procedures were repeated with a similar number of uninfested males and females.

The parasites recovered were measured. The total length (TL) was measured from the anterior margin of cephalon to the posterior margin of uropods for females, and from the anterior margin of cephalon to the posterior margin of pleotelson for males. In addition, the maturity status of females was assessed according to the criteria of Roccatagliata & Torres Jordá (Reference Roccatagliata and Torres Jordá2002) with minor modifications.

Statistical analysis

The non-parametric Chi-square test with Yates correction (Sokal & Rohlf, Reference Sokal and Rohlf1995) was applied for the comparison of prevalence between individuals caught below and above 45 m depth. At this depth there is a change in the slope of the sea bottom off Comodoro Rivadavia and Caleta Córdova. Specimens recently stranded on the beach were not included in this analysis. Differences in prevalence among seasons were tested with an exact test. The exact test is a generalization of the Fisher procedure and calculates an exact probability value for the relationship between two variables in larger tables (Agresti, Reference Agresti1992). Carapace length values were grouped into eight size-classes. An exact test was used to determine independence between prevalence and host size, followed by Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons. For each size-class, the Fisher's exact test was used to test independence between sexes.

The Chi-square test with Yates correction was employed to determine whether infestation caused the castration of females. A comparison was made between the prevalence of ovigerous and non-ovigerous squat lobsters larger than 13 mm CL, which is the size at which all females are mature (Vinuesa, Reference Vinuesa2007). To evaluate the effect of parasitism on egg size, eggs of parasitized and non-parasitized lobsters were compared using one-way analysis of variance. Normality and homogeneity of variances were tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Cochran tests, respectively. Covariance analysis was used to test for differences in the development of chelipeds in males and pleopods in females. The assumption of homogeneity of slopes was previously tested.

To determine the relationship between host size and parasite size, regression analyes were performed in males and females separately. The determination coeficient was estimated too.

RESULTS

Characterization of the host population

A total of 21,519 squat lobsters from San Jorge Gulf were captured between 1997 and 2009. The CL ranged between 3.6 and 32.4 mm in non-infested and between 8.3 and 26.3 mm in infested squat lobsters. The male:female proportion was 1.37:1 for specimens >10 mm CL, but there were seasonal and local variations. Juvenile squat lobsters (<10 mm CL) were collected during summer and early autumn. Specimens of the morphotype gregaria were found in waters of San Jorge Gulf in 2008 (N = 13) and 2009 (N = 1220). In previous years only squat lobster of the subrugosa morphotype were collected. Despite the small number of gregaria specimens captured, both morphs were found parasitized.

Bopyrid infestation

The parasitized squat lobsters (N = 69) exhibited a gross bulge on the side where the parasite was found. The parasite was present in all specimens with distorted carapace. In all cases the parasite occupied the right branchial chamber (Figure 2). The female bopyrid was found with its head pointing toward the host's abdomen and its dorsal surface in contact with the gills, which were slightly flattened in fixed specimens. Branchial filaments had no visible lesions and no evidence of multiple infestations was observed in any of the squat lobsters infested.

Fig. 2. Specimen of Munida gregaria (carapace length = 18.5 mm) showing the carapace bulge caused by the bopyrid Pseudione galacanthae in San Jorge Gulf, Argentina.

Prevalence

The prevalence of P. galacanthae in M. gregaria was very low throughout the study, with a mean value of 0.34% (90% confidence interval limit: 0.27–0.41). The highest prevalence obtained in a sample was 1.43% (Table 1). No significant differences in prevalence were found between specimens collected below and above 45 m depth (χ Yates correction = 1.00; P = 0.31) (Table 2) and among seasons (χ = 4.04; df = 3; P = 0.25) (Table 3). The prevalence differed significantly among size-classes (P = 0.010). The a posteriori test revealed that this difference was due to higher prevalences in the size-class 7.0–9.9 mm CL (χ Yates corrected = 10.69, P = 0.001). There were no significant differences in prevalence between sexes in each size-class (Table 4).

Table 1. Prevalence of Pseudione galacanthae in Munida gregaria, in the central area of San Jorge Gulf, Argentina.

Table 2. Prevalence of the bopyrid Pseudione galacanthae in Munida gregaria specimens collected below and above 45 m depth; 95% confidence interval limit with continuity correction in parentheses. Specimens stranded on the beach were not included in the analysis.

Table 3. Prevalence of the bopyrid Pseudione galacanthae in Munida gregaria by season; 95% confidence interval limit with continuity correction in parentheses.

Table 4. Prevalence of the bopyrid Munida gregaria in Pseudione galacanthae by host size-class (carapace length in mm). For each size-class, the P value in the last column indicates the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis of independence between infestation and sex.

N, number of specimens; P, probability.

Bopyrid effect on host reproductive potential

In males, the presence of the parasite had no effect on the propodite of the first pair of pereiopods (ANCOVA df = 1; f = 2.82; P = 0.098). In addition, developed testes and distended deferent ducts were observed in parasitized males during the reproductive season.

Seven parasitized ovigerous females were collected, with complete broods and recently spawned eggs. There was no significant difference in prevalence between non-ovigerous and ovigerous females (>13 mm CL) (χ Yates corrected = 1.80, P = 0.17) (Table 5). No differences were found in the size of pleopods III–V between infested and uninfested females (Table 6). The egg size of parasitized females was significantly lower (ANOVA, df = 1; f = 5.85; P = 0.03) than that of non-parasitized females. Infested and non-infested ovigerous females had similar fecundity values, but statistical comparisons were not made due to the small number of the former.

Table 5. Prevalence of the bopyrid Pseudione galacanthae in ovigerous and non–ovigerous females of Munida gregaria >13 mm carapace length; 95% confidence interval limit with continuity correction in parentheses.

Table 6. Covariance analysis to test the efect of parasitism on secondary sex characters in females of Munida gregaria.

df, degree of freedom; F, F ratio; P, probability values associated with F values.

Relationship between bopyrid and host size

Bopyrid females were always present in squat lobsters showing distorted carapaces. Only one dwarf male was found on the female abdomen. Although males were missing in some of the parasitized hosts, the arrangement of the female's pleopods provided evidence of their earlier presence. The size of bopyrid females was directly related to host size (P = 0.000, N = 53). The male size was also directly related to host size (P = 0.000; N = 33) (Figure 3). In addition, a postmoult squat lobster had a parasite with soft carapace.

Fig. 3. Relationship between carapace length (CL, mm) of the Munida gregaria and total length (TL, mm) of the parasite Pseudione galacanthae. Equation for the regression of bopyrid females and probability value: TL = 1.58 + 0.608 CL (P = 0.000) (R2 = 0.90). Equation for the regression of bopyrid males and probability value: TL = 0.79 + 0.148 CL (P = 0.000) (R2 = 0.69).

Squat lobsters in the size-class 7–10 mm CL harboured immature females with cryptoniscii larvae. One of these lobsters had five larvae attached to the pleon of the parasitic female. The larvae and early stages of the parasite were found during summer, simultaneously with a higher abundance of the host juvenile stages. No larvae were detected in specimens <7 mm CL. Immature females of P. galacanthae were found in squat lobsters >7 and <10 mm CL during summer and early autumm. The specimens in the remaining size-classes were infested with mature females (Figure 4). Ovigerous bopyrid females were observed in hosts between 10 and 26.3 mm CL all year round.

Fig. 4. Relationship between developmental stages of Pseudione galacanthae females and Munida gregaria carapace length.

DISCUSSION

Bopyrid infestation

The preference for one branchial chamber is common in the subfamily Pseudioninae (Markham, Reference Markham, Gore and Heck1986). There may be a link between the exclusive presence of the parasite in the right branchial chamber and the absence of multiple infestations. A similar behaviour has been observed for bopyrids parasitizing other sub-Antarctic anomurans, such as Lithodes santolla (Vinuesa, Reference Vinuesa1989; Cañete et al., Reference Cañete, Cárdenas, Oyarzún, Plana, Palacios and Santana2008) and Paralomis granulosa (Jacquinot, 1847) (Vinuesa, Reference Vinuesa1989; Roccatagliata & Lovrich, Reference Roccatagliata and Lovrich1999). Rayner (Reference Rayner1935) in the south-west Atlantic Ocean reported a preference of 92% for the right branchial chamber and double infestation in 3.3% in Munida gregaria.

In contrast to other host–parasite interactions described in the literature, Pseudione galacanthae was always found in lobsters from San Jorge Gulf with carapace swelling. This suggests that infested individuals cannot remove the parasite through successive moults. Some authors indicate that bopyrids missing in decapods with signs of a former infestation (carapace with bulge) had been removed by the hosts (Sommers & Kirkwood, Reference Sommers and Kirkwood1991; Cash & Bauer, Reference Cash and Bauer1993; Roccatagliata & Lovrich, Reference Roccatagliata and Lovrich1999).

Prevalence

The species of genus Munida usually have low prevalence values of bopyrid infestation. The prevalence of Anuropodione carolinesis Markham, 1973 in the squat lobster Munida iris iris from the north-western Atlantic Ocean was found to range between 2 and 5% (Lewis-Wenner & Windsor, Reference Lewis-Wenner and Windsor1979). Prevalences of 0.06 and 0.6% were reported for Munida tenuimana and Munida intermedia respectively (Gramito & Froglia, Reference Gramito and Froglia1998; Mori et al., Reference Mori, Orecchia and Biagi1999). The highest prevalences recorded for Munida longipes and Munida microphtalma were about 5% (Lewis-Wenner & Windsor, Reference Lewis-Wenner and Windsor1979) and a prevalence of about 1–2% was reported for Munida rugosa (Bourdon, Reference Bourdon1968). The infestation of M. gregaria by P. galacanthae in the Argentine continental shelf showed a prevalence of 7.4% in the subrugosa morphotype and 3.7% in the gregaria morphotype (Rayner, Reference Rayner1935). The low prevalences found in the present study are in agreement with the results obtained for other species of the genus, but lower than that observed by Rayner (Reference Rayner1935). This difference may be related to the local conditions in the central area of San Jorge Gulf.

Environmental conditions play a major role in the prevalence of bopyrid infestation among decapod populations. High prevalences of P. tuberculata in the southern king crab Lithodes santolla from the Magellan Strait were attributed to a reduction in the water flow due to the presence of Macrocystis pyrifera, (L) Agardh 1820, forests (Cañete et al., Reference Cañete, Cárdenas, Oyarzún, Plana, Palacios and Santana2008). Muñoz & George-Nascimento (Reference Muñoz and George-Nascimento1999) found that the prevalence of Ionella agassizi Bonnier, 1900 parasitizing the ghost shrimp Neotrypaea uncinata (H. Milne-Edwards, 1837) was higher in estuaries than on open coasts. Pseudione humboldtensis Pardo, Guisado & Acuña, Reference Pardo, Guisado and Acuña1998 has been reported parasitizing the galatheids Cervimunida johni and Pleuroncodes monodon with variable values at different localities along the Chilean coast (Pardo et al., Reference Pardo, Guisado and Acuña1998; González & Acuña, Reference González and Acuña2004). It has been suggested that the high prevalence of the parasitic barnacle Briarosaccus callosus Boschma, 1930 in the golden king crab Lithodes aequispina (Benedict, 1894) is related to high larval retention, as commonly observed in fjords (Sloan, Reference Sloan1985). These findings suggest that prevalences are higher in areas with low water circulation, even if the life cycle of the parasite includes an intermediate host, as is the case with bopyrids. In the central area of the San Jorge Gulf, M. gregaria occurs mainly on coastal soft bottoms (Vinuesa, Reference Vinuesa2005). The low prevalence values obtained for specimens from the coastal area (<45 m) and deeper waters (>45 m) may be explained by the lack of benthic algae and bottom irregularities which could reduce currents flow and promote larval retention.

Differences in the prevalences between sexes are related to the higher energetic cost of reproduction for female (Astete-Espinoza & Cáceres, 2000). No difference in bopyrid prevalence was found between males and females of M. iris iris (Lewis-Wenner & Windsor, Reference Lewis-Wenner and Windsor1979), M. intermedia (Gramito & Froglia, Reference Gramito and Froglia1998) and Cervimunida johni (González & Acuña, Reference González and Acuña2004). Likewise, in San Jorge Gulf squat lobsters of both sexes did not differ in prevalence, independently of their size. This would be related to a minor negative effect of parasitism on females. The relationship among prevalence, season and host size is discussed below.

Effect on host reproductive potential

A negative effect of bopyrid parasitism on reproduction (e.g. reduced gonads and poor development of secondary sexual characteristics) has been reported in several species (Beck, Reference Beck1980; Schuldt & Rodrigues-Capítulo, Reference Schuldt and Rodrigues-Capítulo1985; Muñoz & George-Nascimento, Reference Muñoz and George-Nascimento1999; Roccatagliata & Torres Jordá, Reference Roccatagliata and Torres Jordá2002). Reinhard (Reference Reinhard1956) states that parasites may affect adversely the secondary sex characters of males. Many authors have reported feminization in parasitized males (Reinhard, Reference Reinhard1956; Beck, Reference Beck1980; Muñoz & George-Nascimento, Reference Muñoz and George-Nascimento1999) and no effect on testis development (Beck, Reference Beck1980; Schuldt & Rodrigues-Capítulo, Reference Schuldt and Rodrigues-Capítulo1985; Muñoz & George-Nascimento, Reference Muñoz and George-Nascimento1999). In San Jorge Gulf, the bopyrid affected neither the testis development nor secondary sex characters of infested males, indicating no negative impact on their reproductive function. However, variations in sperm production and behaviour of infested males should not be ruled out.

According to Reinhard (Reference Reinhard1956), gonadal development is more affected than the secondary sex characters in females parasitized by epicaridean isopods. However, a decrease in the length of the last three pleopods has been observed in parasitized specimens of M. tenuimana (Zariquiey Alvarez, Reference Zariquiey Alvarez1958; Bourdon, Reference Bourdon1968). The parasitized females of M. gregaria from San Jorge Gulf showed normal secondary sex characters. Moreover, the similar prevalence of P. galacanthae in ovigerous and non-ovigerous females suggests the absence of parasite-induced castration. The lack of significant effect on egg size suggests a low parental investment related to the energetic cost of parasitism. Fecundity did not seem to be affected by the bopyrid, but this issue is worthy of more detailed investigation. These results together suggest that the reproductive potential of M. gregaria in San Jorge Gulf would not be reduced by the parasitic infestation.

Relationship between bopyrid and host size

In other Anomura, prevalence decreases as size increases, with the highest values being recorded at early development stages (Rocattaglatia & Lovrich, 1999; González & Acuña, Reference González and Acuña2004). A reduction in the prevalence of P. humboldtensis in the squat lobsters Cervimunida johni and Pleuroncodes monodon from Chile has been attributed to the removal of the parasite (González & Acuña, Reference González and Acuña2004). However, this is not likely the case in the parasite–host interaction studied here.

The prevalence was significantly higher in the size-class 7–9.99 mm CL than in the remaining ones. Infestation may occur in this size-class as suggested by the presence of immature females and cryptoniscii larvae. A substantial decrease in the prevalence coincided with the onset of sexual maturity in the bopyrid females. The ovarian maturation of the parasitic female may exert additional pressure on the host caused by increased energetic demand; this would lead to an increase in mortality, and ultimately, to a decrease in the prevalence of larger size intervals. The stabilization of the prevalence at larger sizes may reflect low parasite-induced host mortality (Roccatagliata & Lovrich, Reference Roccatagliata and Lovrich1999). The early stages of the parasite observed during summer and at the beginning of autumn occurred simultaneously with an increase in the number of M. gregaria juveniles. This developmental synchrony between host and bopyrid has been mentioned for other anomurans such as Munida iris iris (Lewis-Wenner & Windsor, Reference Lewis-Wenner and Windsor1979), Paralomis granulosa (Roccatagliata & Lovrich, Reference Roccatagliata and Lovrich1999) and Petrolisthes armatus Gibbes, 1850 (Oliveira & Masunari, Reference Oliveira and Masunari2006). Roccatagliata & Lovrich (Reference Roccatagliata and Lovrich1999) suggested that the presence of mature females of the bopyrids at early host stages reveals an early infestation. Also, a linear relationship between host body size and parasite size would be evidence of an early infestation, parallel growth and moulting synchronicity of host and parasite. Furthermore, this relationship between parasite and host size and larger infested squat lobster suggests a life-long relationship.

The wide size-range of ovigerous females of P. galacanthae may indicate that it undergoes multiple spawnings during its lifetime. Some bopyrid species are known to spawn four or five times over their lifespan (Pike, Reference Pike1960). Bopyrids occurring at low latitudes are expected to exhibit prolonged reproductive periods (Román-Contreras & Romero-Rodríguez, Reference Román-Contreras and Romero-Rodríguez2005; Oliveira & Masunari, Reference Oliveira and Masunari2006). An interruption in the reproductive activity in winter time has been documented in Petrolisthes armatus at mid-latitudes (Oliveira & Masunari, Reference Oliveira and Masunari2006) and in Uca uruguayensis Nobili, 1901 (Torres Jordá & Roccatagliata, Reference Torres Jordá and Roccatagliata2002). In this work, ovigerous females of Pseudione galacanthae occurred throughout the year. Their wide temporal distribution was inconsistent with the short infestation period in juvenile squat lobsters. A continuous reproduction with an infestation period of six months has been reported by McDermott (Reference McDermott1991) for the bopyrid Leidya bimini Pearse, 1951. In order to explain this behaviour, Torres Jordá & Roccatagliata (Reference Torres Jordá and Roccatagliata2002) suggested that epicaridium larvae would remain for a longer time in the intermediate copepod host until environmental conditions become favourable. Other factors related with epicaridium–copepod interaction and physical dynamics of water column may influence the infestation period.

Effect on squat lobster population

Finally, the prevalence of P. galacanthae in the natural M. gregaria population from San Jorge Gulf was found to be related to host size but not to depth, season or host sex. The temporal distribution of juvenile lobsters would be the major regulating factor of infestation. The parasite seems to have a minor impact on the M. gregaria population because of the low and similar prevalences in males and females, absence of castration and little influence on the reproductive potential. This is also supported by the absence of multiple infestations. Therefore, P. galacanthae plays a minor role in regulating the M. gregaria population in San Jorge Gulf.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks are due to Prefectura Naval Argentina and the fishermen Gabriel Gianotta, Luis Badia and Ernesto Silva for collecting the squat lobsters; to Dr Daniel Roccatagliata for his collaboration in the identification of Pseudione galacanthae; and to Lic Héctor Zaixso for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This work was partially funded by the Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco (UNPSJB) and the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) of Argentina.