Introduction

With no hardened, waterproof carapace on its fleshy abdomen, an intertidal hermit crab must find external protection to survive against predators and this harsh environment (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981); thus appropriate choice of a domicile is critical to the individual's survival. Most species of hermit crabs inhabit shells of deceased gastropods to protect against predation, desiccation, temperature and salinity stresses (Reese, Reference Reese1969). While nutrient availability is rarely a limiting factor for hermit crabs (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981), appropriate shells often are (Bollay, Reference Bollay1964; Vance, Reference Vance1972; Mantelatto & de Meireles, Reference Mantelatto and de Meireles2004). Because the probability of finding a shell of proper size and quality is low, the cost of relying on these sporadic resources is high (Rotjan et al., Reference Rotjan, Chabot and Lewis2010).

Different shell species, with their varied shell morphologies and maximum sizes, vary in the levels of protection that they provide (Alcaraz et al., Reference Alcaraz, Chávez-Solís and Kruesi2015). While high-spired shells can reduce thermal stress for hermit crabs due to increased surface area, low-spired, heavy shells can reduce threats from shell-crushing predators and provide hydrodynamic advantages in wave-exposed areas (Bertness, Reference Bertness1982; Hahn, Reference Hahn1998; Arce & Alcaraz, Reference Arce and Alcaraz2012). Heavy shells with thick-lipped apertures can resist predation by generalized crushers (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981), while lighter shells can permit more rapid movements and growth of the hermit crab (Alcaraz et al., Reference Alcaraz, Chávez-Solís and Kruesi2015). Therefore, selecting the correct shell has strong ecological and evolutionary significance for hermit crabs (Reese, Reference Reese1969), and differences in tidal regimes and predation pressures can result in different shell preferences (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Reverdy and Cooke1998, as well as references earlier in this paragraph).

Hermit crabs usually occupy and select a distinct subset of the available species of gastropod shells (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981). Availability of high quality, empty shells is affected by both shell abundance and inter- and intraspecific competition between hermit crabs (Reese, Reference Reese1969; Balazy et al., Reference Balazy, Kuklinski, Włodarska-Kowalczuk, Barnes, Kędra, Legeżyńska and Węsławski2015). Because hermit crabs cannot secrete calcium carbonate, they can neither repair, reinforce nor grow new shell length, so the crabs need to constantly search for new, structurally rigorous shells of larger sizes. Shells can be damaged and weakened by predation attempts, wave action and acidity of the marine waters. In the intertidal of California, available shells deteriorate to the extent that they are not habitable by hermit crabs in fewer than 9 months (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981). Additionally, unoccupied shells can quickly become buried, exported to the subtidal by strong currents or colonized by epibionts (Conover, Reference Conover1975; Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a; Laidre, Reference Laidre2011). Therefore, hermit crabs must frequently place themselves strategically in the zones where most gastropods reside to obtain empty shells before they are unusable or out of reach (Conover, Reference Conover1975; Laidre, Reference Laidre2011).

The rocky low-intertidal zones of sites on San Juan Island, WA, USA are dominated by two hermit crab species, Pagurus beringanus (Benedict, 1892) and Pagurus granosimanus (Stimpson, 1859). While both of these species inhabit shells of a variety of gastropods, they exhibit very similar shell preferences (Vance, Reference Vance1972; Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a). Despite this, Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) stated that interspecific competition between these species was insignificant compared with intraspecific competition, largely because they utilized different microhabitats: P. beringanus existed in the shallow subtidal, rarely venturing into the lower intertidal, while P. granosimanus existed in the mid- to lower intertidal. However, our preliminary observations found substantial numbers of both species in the low intertidal. Based on these observations, we surmised that ecological parameters may have shifted since Abrams’ (Reference Abrams1987a) work to promote more frequent interactions, and perhaps competition, between these two species.

Previous studies of our two species of interest were largely conducted in the 1970s and 1980s. Since that time, environmental change has occurred in both the terrestrial and marine environments of the San Juan Islands. Climate change impacts can alter interactions between species as well as change the physiology and survival of individuals (Helmuth et al., Reference Helmuth, Babij, Duffy, Fauquier, Graham, Hollowed, Howard, Hutchins, Jewett, Knowlton, Kristiansen, Griffis and Howard2013). Elevated CO2 and reduced seawater pH can disrupt resource assessment and decision-making processes of hermit crabs, as well as elevate metabolic load and impair performance capacities (de la Haye et al., Reference de la Haye, Spicer, Widdicombe and Briffa2011; Briffa et al., Reference Briffa, de la Haye and Munday2012). Animals living in tide pools might be at higher risk of pH-induced alterations due to reduced water flow allowing larger acidity fluxes across tide cycles. Additionally, hypoxia (also more likely in warming tide pools) can cause hermit crabs to favour smaller, lighter shells (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Reverdy and Cooke1998). Taken together, recent environmental changes may have caused hermit crab populations on San Juan Island to shift their shell preferences and microhabitat distributions over the past 40 years, possibly affecting competitive interactions among species. Furthermore, preferred shell characteristics may differ across sites, and even within a site, if individuals tend to remain within a particular microhabitat based on amount of wave exposure and water flow (Bertness, Reference Bertness1982). These possibilities suggest that a re-evaluation of the habitat overlap and use of shells of these sympatric hermit crabs is of current interest.

For these reasons, we examined the distribution and shell use of two sympatric species of hermit crabs (Pagurus granosimanus and Pagurus beringanus) in the field at five locations around San Juan Island, Washington state, examining two different intertidal microhabitats at each site: the more exposed fore-shore area and the more protected area with tide pools and tidal channels. We sought to determine whether the two species of hermit crabs were truly sympatric at this microhabitat level, and whether they inhabited the same array of host shells in the same proportions. We predicted that the two hermit crab species would differ in terms of the microhabitat predominantly utilized at each location, which would reduce interspecific competition. Additionally, due to the different amount of wave action in these two microhabitats, we predicted that the hermit crab species would differ in shell species utilized. However, because individual hermit crabs can potentially move between protected and exposed areas even if there is a general species-level disjunct micro-distribution, we predicted that the most-used species of shell would be the same within a hermit crab species regardless of the microhabitat in which the animal was collected.

Materials and methods

Hermit crab shell use

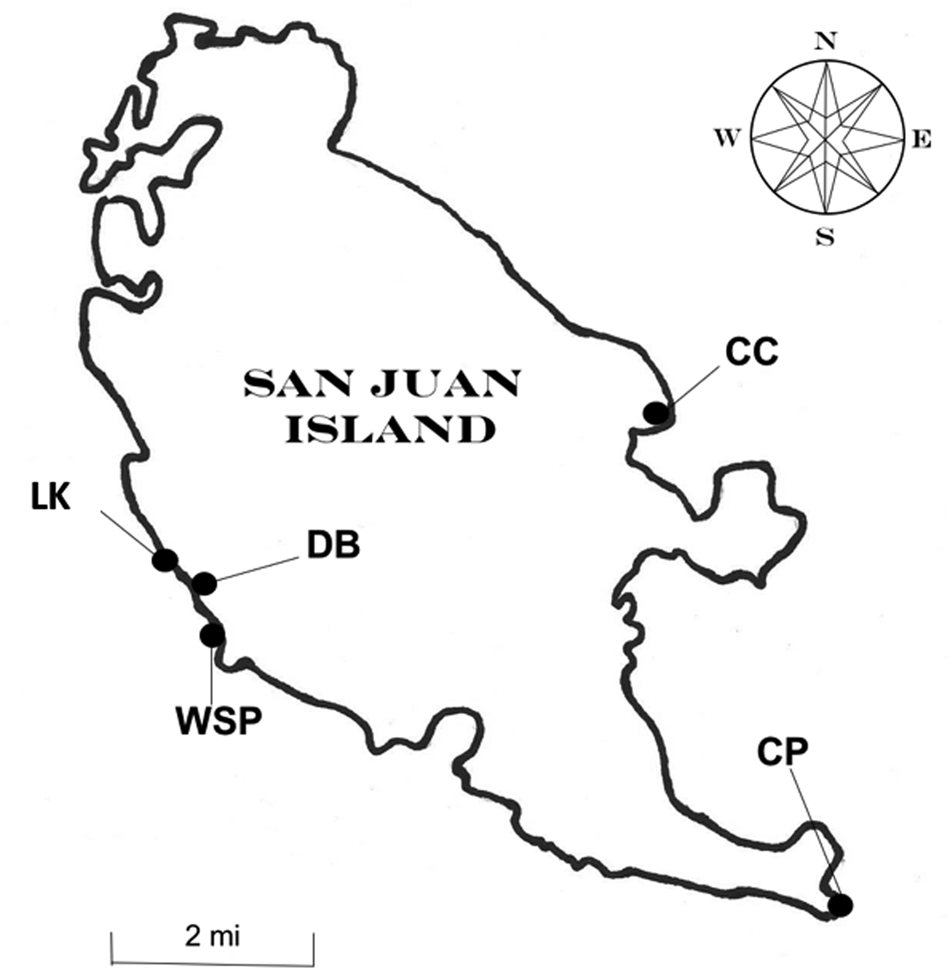

We conducted hermit crab population surveys on San Juan Island, Washington state at five sites (Figure 1), one site per day, in June 2017. We examined and compared shell use by two hermit crab species: Pagurus beringanus and Pagurus granosimanus. The sites examined included Cattle Point (48°45′06″N 122°96′33″W), Westside Scenic Preserve (48°30′19″N 123°8′28″W), Deadman Bay (48°30′47″N 123°8′49″W), and Lime Kiln (48°30′57″N 123°9′6″W) on the west side of the island, and Colin's Cove (48°33′4″N, 123°0′20″) on the east side of the island (site acronyms provided in Table 1), with daily minimum low tide levels ranging from −0.86 to −0.5 m MLLW. While we did not explicitly quantify wave exposure, observations of wave action and macroalgal species present indicated varying levels of wave exposure at each site. Colin's Cove was most protected from waves. Our survey location within Deadman Bay receives less wave action than the other west-side sites. While Westside Scenic Preserve, Lime Kiln and Cattle Point receive largely comparable overall levels of wave action, our study areas at these sites differed due to local topography. Westside Scenic Preserve, due to largely subtidal rocks paralleling the shore, was more protected than Lime Kiln, while Cattle Point typically was the most exposed of the three.

Fig. 1. A map of San Juan Island with labels indicating the five collection sites (CP, Cattle Point; WSP, Westside Scenic Preserve; DB, Deadman Bay; LK, Lime Kiln; CC, Colin's Cove).

Table 1. A list of the acronyms used in the paper

Field sites are listed in the order of lowest to highest amount of wave exposure.

Each of these five sites is dominated by rock benches and large boulders, with occasional small cobble fields interspersed. Across sites, we collected from intertidal zones containing the same dominant sessile species to match emersion time. Our highest tide pools were below the Semibalanus cariosus (Pallas, 1788) zone and our lowest tide pools and exposed collections were at the intersection of the lowest extent of sea cabbage, Hedophyllum sessile (C.Agardh) Setchell, 1901, and the highest extent of Laminaria spp. Lamouroux, 1813. At Colin's Cove there was no Hedophyllum sessile, so we surveyed at the lower extent of Ulva/Ulvaria spp. Linnaeus, 1753/Ruprecht, 1850. While the exact tidal height of the organisms we used as delineating markers may change among locations and even over time, the upper zonal limits often track physical factors such as temperature stress (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Attrill, Jennings, Thomas, Barnes, Brierley, Hiddink, Kaartokallio, Polunin and Raffaelli2011) which likely also impact the hermit crabs, so biotic markers, rather than set tidal heights, were deemed as better indicators of relevant habitat for the hermit crabs.

Within the mid- to low-intertidal zones, even contiguous protected and exposed microhabitats can vary dramatically in terms of stresses on the local organisms. For instance, water in a protected microhabitat (such as a tide pool) typically attains a progressively higher temperature and lower oxygen level during the low tide period than does an area with constant water exchange. Therefore, at each site we distinguished between two microhabitats within the same range of tidal heights: protected and exposed areas. We defined ‘protected areas’ as tide pools, areas behind elevated rock ledges, and tidal channels with rocky sides high enough and positioned at angles to the shore that substantial turbulent water exchange with incoming waves was precluded. We defined ‘exposed areas’ as small channels and bedrock ledges positioned such that they were inundated by the turbulence of incoming waves. While the protected microhabitats were typically at a slightly higher elevation than the exposed microhabitat areas, the difference in elevation was not dramatic, and likely resulted in less than an hour's emersion-time difference each tidal cycle.

Walking along a belt transect that was at least 10 m in length in each of the two microhabitats, we collected all the shells that were uninhabited or contained hermit crabs (exclusive of the species Pagurus hirsutiusculus (Dana, 1851), which was rare in our transects due to the tidal height) that were at least one centimetre in length. The term ‘shell’, for the rest of this article, will be used to indicate either an empty shell or one occupied by a hermit crab. We designated this minimum shell size because we doubted that we could collect an accurate representation of individuals smaller than one centimetre in length due to their ability to shelter deep in crevices and underneath rocks. However, we observed very few individuals smaller than 1 cm in length in our sample areas, so we do not think this minimum size requirement affected our conclusions for patterns of adult hermit crab shell use.

To collect ~100 total individuals, we continued searching beyond the transect if necessary, remaining within the same tidal height and microhabitat. If one of the species was in low abundance, we searched for at least an additional 30 min beyond the time spent on the original transect line before terminating our search. Therefore, our search time at each site was typically between 45 and 90 min in each microhabitat, as dictated by the tidal regime and number of hermit crabs present. Thus, the exact number of animals collected at each site varied due to natural variations in density, but this variability should not skew our results because our data analyses considered relative proportions rather than absolute densities. However, this variability does preclude direct comparisons of densities of the same species of hermit crab across different microhabitats within a site or across sites, as areas with lower densities received longer search times across greater distances in an effort to attain additional specimens.

In the laboratory, we identified the species and length of each shell, determined whether it was empty or inhabited, and determined the species of hermit crab inhabitant (names and acronyms for each as denoted in Table 1). While we also recorded the weights of the shells and hermit crab inhabitants (both together and separately) for a subset of the animals collected at each site, those data are not presented in this manuscript. All hermit crabs and uninhabited shells, except those used in experiments reported elsewhere, were returned to their respective collection sites after measuring.

Statistical analyses

Separate multinomial analyses were conducted on each site*microhabitat*hermit crab species combination to determine whether certain species of shells were used more often than others. A Monte Carlo function using the function xmonte() from the XNomial package (Engels, Reference Engelsn.d.) in RStudio (version 1.4.1106) was used in place of the basic multinomial analysis because of its ability to handle large numbers while still working within a multinomial distribution. Following the finding of a significant deviation from a random distribution, post hoc tests were performed to determine whether the shell with the largest outlier was, indeed, used to a degree that was statistically significantly different from expected when all other shell types were combined. If the outlier was significant, pairwise comparisons were then performed between the outlier and its closest-ranked shell. If these two choices were not significantly different from one another, the next closest ranked shell was compared with the top outlier in a pairwise comparison. This pattern of pairwise comparisons continued until a shell species was significantly different from the largest outlier species. The shell found to be significantly different from the largest outlier was then statistically compared with the shell ranked just above it to determine whether these two shells differed significantly. This iterative process allowed us to determine which shells were used to a disproportionate amount, allowing us to determine if multiple shell types (rather than simply the largest outlying species) were preferentially selected for or against, compared with a random expectation. If fewer than 15 crabs of one species were collected at a site, we did not include that species in statistical tests. For all multinomial analyses, we used a null hypothesis of assumed equal proportions across categories.

Additionally, separate chi-square tests-of-independence were calculated using data from each site*microhabitat*hermit crab species combination to determine whether the proportional distribution of the two hermit crabs differed between habitats within a site. If there were fewer than 10 of any shell type collected, that shell was not included in statistical calculations. We used P < 0.05 as the threshold for significance for all statistical analyses.

Unfortunately, due to the fact that we did not collect hermit crabs from a set, pre-determined quadrat nor for an exact standard amount of time, we cannot calculate statistical analyses of the relative proportion of the populations of one species across microhabitats, nor compare their population densities across sites. However, because our sampling was conducted on sequential days and we were limited by the available time of emersion for the search area, we typically searched for relatively comparable times at each site, and made an effort to do so across microhabitats within a site as well. Therefore, large discrepancies in the number collected are suggestive of true density differences in the field and may be informative as to what abiotic factors influence these density differences.

Results

Empty shells may sometimes be a limited resource

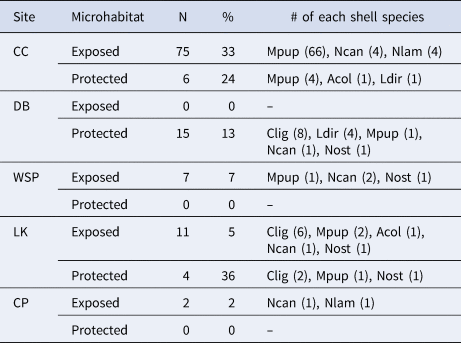

Often few empty shells were collected within each microhabitat*site location (<10% of the shells collected at six of the 10 locations were empty; Table 1, Table 2), but some locations had a large number of empty shells (Table 2). In both microhabitats at Colin's Cove and in the protected microhabitat at Deadman Bay, the most common species of empty shells correlated well with the most commonly inhabited shells of hermit crabs (Table 3): M. pupillus at Colin's Cove and C. ligatum for Pagurus beringanus at Deadman Bay. Almost all of the empty shells at Colin's Cove were found interstitially on a cobble beach, which was the only cobble beach surveyed in our collections. These shells typically lay on the benthos such that they could be accessed and moved by hermit crabs, and rarely possessed epibionts or other encrustations that would preclude inhabitation by a hermit crab, so the shells represented potential domiciles.

Table 2. Empty shells found in the collections, separated by microhabitat*site and listed in order of decreasing frequency

% = [(# of empty shells)/(# of empty shells + # of hermit-inhabited shells)] × 100. See Table 1 for an explanation of the abbreviations.

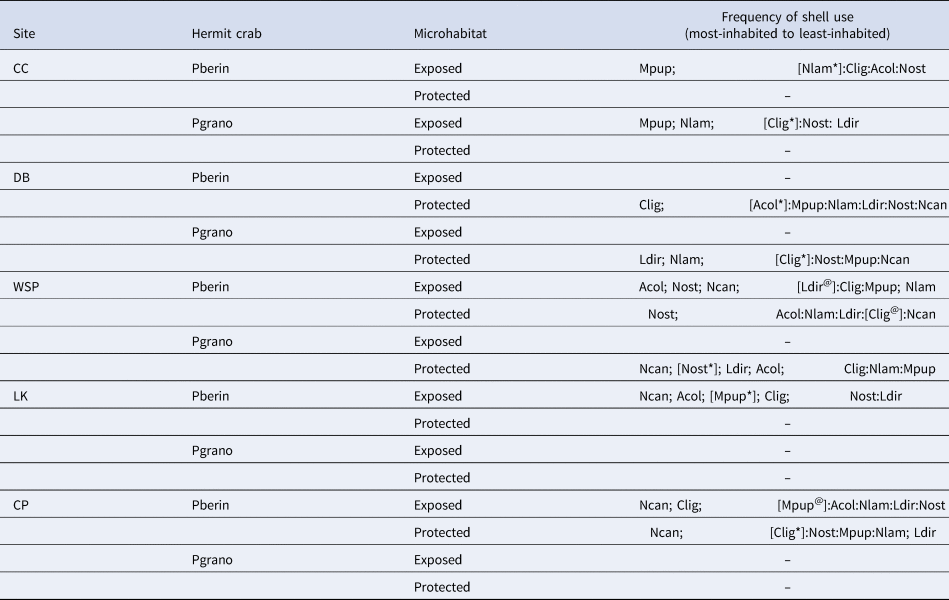

Table 3. Species rankinga based on the relative frequency of occupancy by hermit crabs (P. beringanus and P. granosimanus)

Spacing within ‘Frequency of shell use’ indicates the termination of sequential elimination of the most-used species that were significantly different from the remaining gross aggregate collection. Significant differences from the remaining group of species are separated by semi-colons (;), insignificant differences by colons (:). A bracket ([ ]) indicates the species it envelops was significantly different from the most-used species. An asterisk (*) indicates that species was significantly different from the next-highest ranked species (the species to its left), @ indicates no significant difference. Sites are ordered to reflect increasing levels of wave exposure. See Table 1 for an explanation of the abbreviations. – = not enough of that hermit crab was found to calculate statistical analyses

a Due to statistical sequential step-wise elimination of categories, ranked items may not have raw numbers varying greatly from contiguous rankings which is why additional pair-wise statistics were calculated and reported herein as * or @.

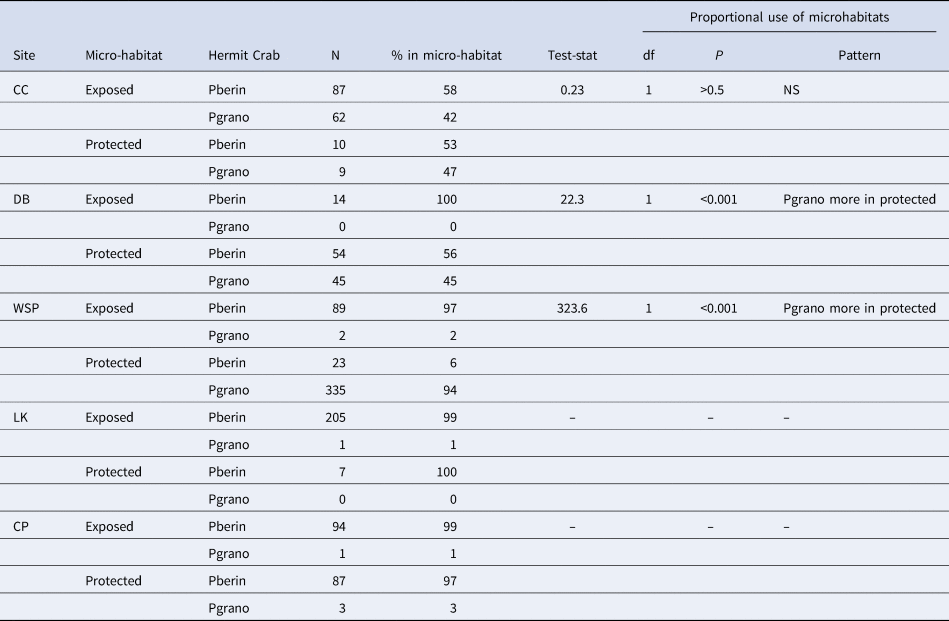

Distribution of the hermit crab species among sites

Pagurus granosimanus was almost completely absent from our two most wave-exposed sites (only five crabs of this species were collected from both Cattle Point and Lime Kiln combined; see N in Table 4). Further, the only time we found this species in appreciable numbers (>3 individuals) in the exposed microhabitat was at Colin's Cove, our most protected site (Table 4). Pagurus beringanus, on the other hand, was found in all exposed and protected microhabitats (see N in Table 4). Pagurus granosimanus, when compared with the relative prevalence of P. beringanus across the microhabitats, were found at two sites (Deadman Bay and Westside Scenic Preserve) to reside disproportionately more in the protected microhabitats, although at Colin's Cove there was no significant difference in the way the two species apportioned themselves across microhabitats (these were the only sites with large enough numbers to evaluate this question statistically; Table 4).

Table 4. Examining niche separation

We compared the relative frequency between microhabitats of the two hermit crab species, using separate χ2-tests of independence at each site. N = the number of individuals collected. % in microhabitat = (N of species A/[N of species A + N of species B]) in that microhabitat. NS = no significant difference. df = degrees of freedom. Sites are ordered to reflect increasing amount of wave exposure. – = expected values were too small to allow statistical comparisons. See Table 1 for further explanation of abbreviations.

Shell use by P. beringanus

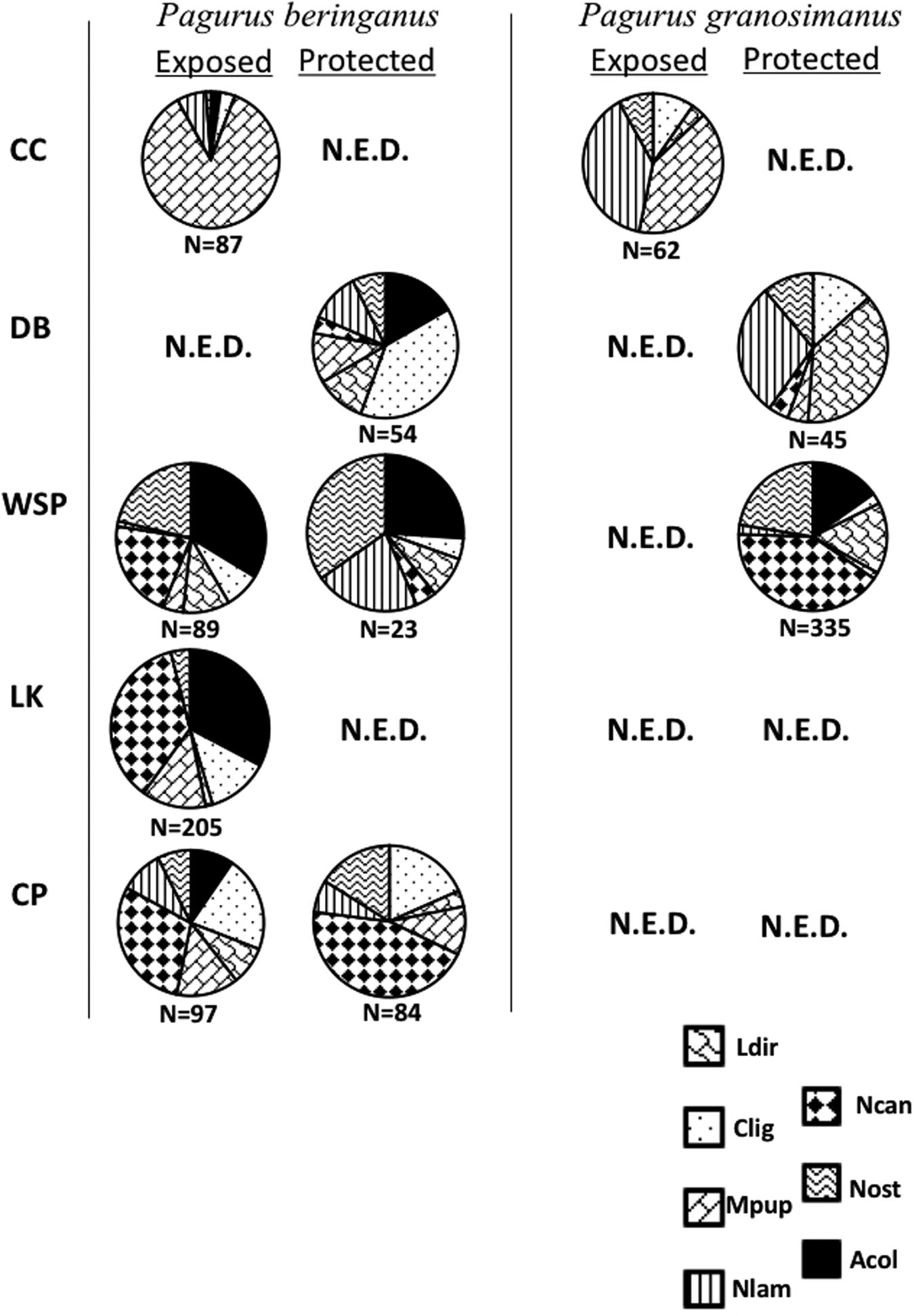

While the same seven species of shells were utilized across the five sites, and typically a few species of shells were used much more often than others, P. beringanus did not show a consistent pattern of shell use across sites*microhabitats. However, there was a clear dichotomy between the shells utilized in the exposed sites (Cattle Point, Lime Kiln and the exposed microhabitat at Westside Scenic Preserve) compared with the more protected sites (Figure 2, Table 3). Nucella canaliculata was often used as a domicile in areas of higher wave action. It was the most-used type of shell at Cattle Point and Lime Kiln (P < 0.0001 for each of exposed and protected microhabitats at CP and exposed microhabitat at LK), and was not significantly different from the most-used shell in the exposed microhabitat at Westside Scenic Preserve. In contrast, there was no consistently used type of shell in the more protected sites. Calliostoma ligatum was the most-used shell at Deadman Bay (P < 0.0001; Figure 2, Table 3), while M. pupillus dominated domiciles at Colin's Cove (P < 0.0001). In the protected microhabitat at Westside Scenic Preserve, N. ostrina was used significantly more than any other shell type (P = 0.042; Figure 2, Table 3) and while two other shell types were common, N. canaliculata was not among them. Interestingly, N. ostrina was used to a substantial extent in both microhabitats and by both species of hermit crabs at Westside Scenic Preserve, but mostly absent as domiciles at all other sites.

Fig. 2. Relative frequencies of shells used at the five sites (see Figure 1 for site acronyms) by both species of hermit crabs (P. beringanus and P. granosimanus) in both microhabitats (exposed and protected). N.E.D. = not enough data; fewer than 15 crabs of one species were collected in that specific microhabitat, so statistical analyses could not be calculated and a chart was not created. Shell abbreviations as noted in Table 1. See Table 3 for statistical results.

Amphissa columbiana was often used as a host shell by P. beringanus except at Colin's Cove and in the protected microhabitat at Cattle Point. In the exposed microhabitat at Cattle Point, unlike the other sites where A. columbiana shells were utilized, this species was not in the top two shells used.

Shell use by P. granosimanus

Unfortunately, there were only three sites where P. granosimanus was found in significant numbers and no site encompassed P. granosimanus at both microhabitats (Figure 2, Table 3). Similar to P. beringanus, P. granosimanus in the exposed microhabitat at Colin's Cove inhabited M. pupillus significantly more than the other shells (P < 0.0001). However, this crab also often utilized N. lamellosa (P < 0.0001). Additionally, in the protected microhabitat at Deadman Bay, P. granosimanus inhabited L. dirum and N. lamellosa significantly more than the other shells (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.001, respectively) rather than using C. ligatum as P. beringanus did. Westside Scenic Preserve was the most exposed site in which we found sufficient numbers of P. granosimanus to conduct analyses, albeit only in the protected microhabitat at this site. Similar to the pattern demonstrated by P. beringanus in the exposed microhabitat (but not in the protected habitat) at this site of greater wave exposure, N. canaliculata was the shell most commonly used (P < 0.0001) by P. granosimanus.

Comparative use of shells between the hermit crabs

The two species of hermit crabs co-occurred in large numbers in one microhabitat at each of our three sites with the lower amounts of wave exposure: Colin's Cove, Deadman Bay and Westside Scenic Preserve. Unfortunately, statistical tests of independence were largely precluded due to overly small expected values. Pagurus beringanus were also collected in adequate numbers for analyses in four other microhabitat*site locations where too few P. granosimanus were collected, but P. granosimanus were never collected in abundance in locations with a dearth of P. beringanus.

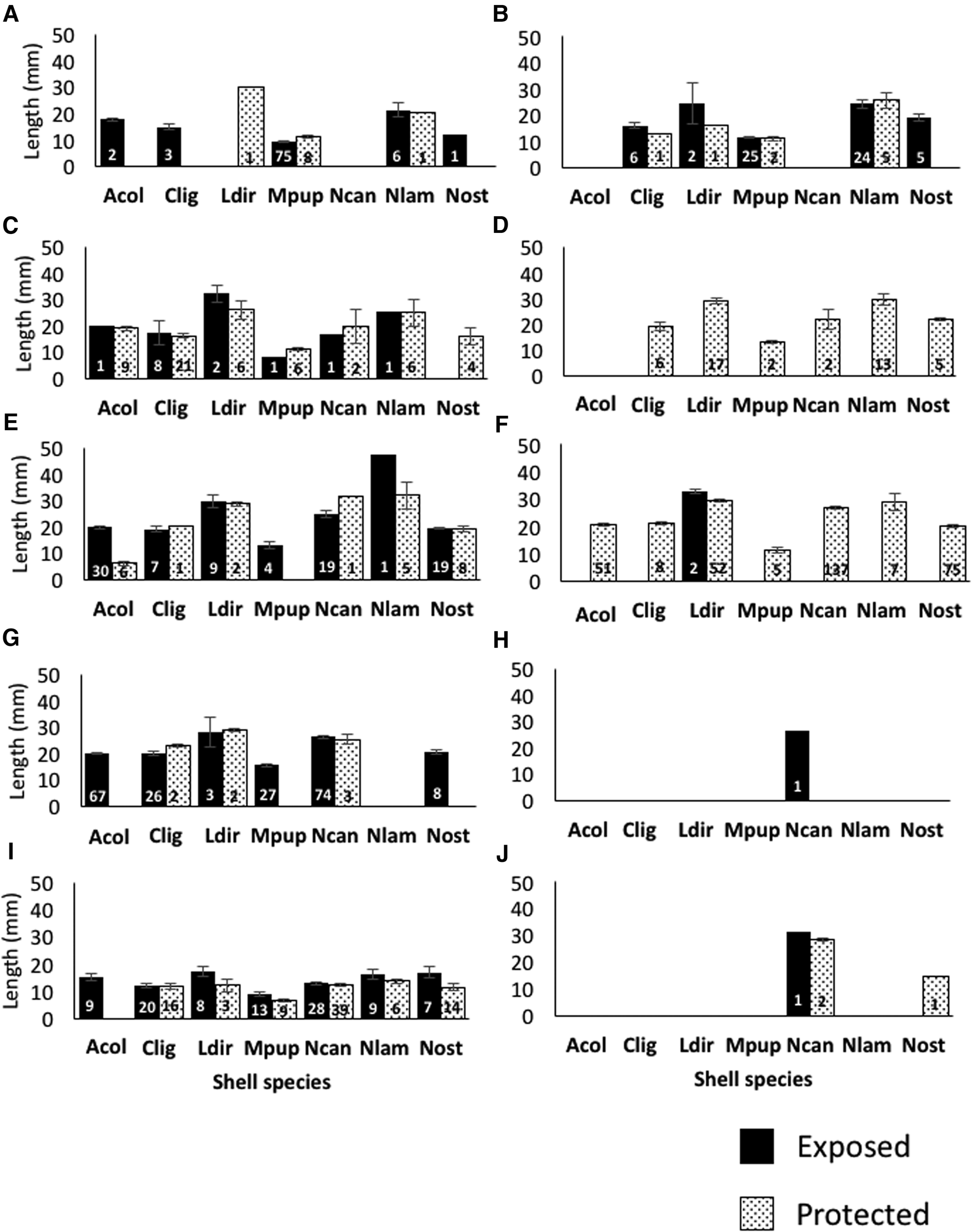

For each of the three possible microhabitat*site comparisons, there was a significant difference between the two hermit crab species in the lengths of shells inhabited: in the exposed microhabitat at Colin's Cove (P < 0.0001), protected microhabitat at Deadman Bay (P < 0.0001), and protected microhabitat at Westside Scenic Preserve (P = 0.028). The lengths also differed across shell species (P < 0.0001, for all three tests). Within a site, visually examining the data on each type of shell separately, in all but one of the eight individual comparisons, P. beringanus inhabited significantly shorter shells than did P. granosimanus (Figure 3; comparisons included the exposed microhabitat at Colin's Cove: M. pupillus and N. lamellosa; the protected microhabitat at Deadman Bay: C. ligatum, L. dirum and N. lamellosa; and the protected microhabitat at Westside Scenic Preserve: A. columbiana and N. ostrina, with N. lamellosa here as the exception). Unfortunately, no more statistical comparisons of this type could be conducted due to a lack of samples for at least one of the species*microhabitats. While so few comparisons were possible that it didn't warrant statistical analyses, both species of hermit crabs tended to use similarly sized shells for each shell species across microhabitats (Figure 3). Additionally, typically the variance of the data for each species of shell within a microhabitat*site was small (see error bars in Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Average length (±1 SE) of each type of shell in each microhabitat, separated by sites and the species of hermit crab inhabitant. Numbers within the bars indicate sample size. Hermit crabs are reported in columns, sites are reported in rows. Shells of P. beringanus are reported in A, C, E, G and I. Shells of P. granosimanus are reported in B, D, F, H and J. CC is A and B; DB is C and D; WSP is E and F; LK is G and H; CP is I and J. Abbreviations as noted in Table 1.

Discussion

Pagurus beringanus and P. granosimanus tended to overlap in distribution significantly at our sites with lower wave action, in contrast to the findings of past researchers that these hermit crab species have large spatial differences in habitat use (Nyblade, Reference Nyblade1974; Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a). Yet, in agreement with previous researchers (Vance, Reference Vance1972; Nyblade, Reference Nyblade1974; Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a), these two species of hermit crabs still largely used similarly sized shells of the same general suite of species across all sites. The increased overlap in populations of P. beringanus and P. granosimanus found in our present studies suggests that interspecific competition may have increased compared with that reported by previous authors almost 50 years ago, and studies of the co-occurrence of these species at other locations within their biogeographic range would be of interest. While shell use differed significantly from an even distribution in all collections, only in one collection (P. beringanus in the exposed microhabitat at Colin's Cove) was a single shell type (M. pupillus) the almost-exclusive domicile, and there was an unusual number of empty shells, mostly of this species, found at this site. Thus, typically, multiple species of shells were utilized to a large extent by both species of hermit crabs, and these shells differed greatly in length:width aspect ratio and shell thickness, suggesting that abiotic stresses exerted by levels of wave-exposure (heat, oxygen-stress and drag forces) did not directly determine the shells used.

Empty shells may sometimes, but not always, be a limited resource

Our results at many intertidal locations on San Juan Island agreed with those of Vance (Reference Vance1972): there were few uninhabited empty shells of appreciable size, suggesting that empty acceptable shells can be a limiting resource for each of our study species. However, there were some unexpected hot spots of empty shells. In the protected microhabitat at Lime Kiln, this was likely due to the few shells collected overall. However, at Colin's Cove, our most protected site, there was a large number of empty M. pupillus shells. This was the only site where shell use by both species of hermit crabs was dominated by a single species of shell: M. pupillus (Table 3). Most of these empty shells were collected on the cobble beach section of the exposed microhabitat. Thus, while largely unimpeded waves encountered this beach, and therefore met our criteria of wave-exposed microhabitat, the shells themselves likely experienced low wave action, and low rates of export from the intertidal, as they were protected by the boundary layer of the surrounding cobble. These findings suggest that hermit crabs at this site that display a moderate amount of lateral movement within the same tidal height might access a fair number of uninhabited shells, in stark contrast to our other study sites which had no close obvious source of uninhabited shells.

Localized hot spots that trap high numbers of empty shells might represent key local resources for hermit crabs. Our searches revealed individual cracks or crevices, especially shoreward on level rock benches, with aberrantly large numbers of empty shells. Vance (Reference Vance1972) also noted that shell-limitation was not universal across sites, and posited that increased habitat complexity decreased shell loss, supporting increased numbers of hermit crabs. Furthermore, while M. pupillus was a common snail in the intertidal at Colin's Cove, they were not as disproportionately dominant compared with the other species of snails as suggested by the use of their shells by the hermit crabs (unpublished data). Perhaps subtidal shells may augment those from the intertidal and increase availability of domiciles for hermit crabs, as this snail species is also common on shallow subtidal kelp at this site (Iyengar, personal observations). The extent of such augmentation and whether hermit crabs can learn where to exploit resource-rich empty shell patches, or merely serendipitously encounter them, would be of interest but is currently unknown.

Interestingly, the majority of shells at Cattle Point (our most wave-exposed site) were catastrophically damaged by durophagous predators, a trend that was not obvious at our other sites. Concurrently, we observed a much higher number of Cancer productus Randall, 1840 at this site than our other locations (personal observations). The activity of the predators substantially broke the shell at the aperture such that often the entire body whorl was missing although the columella remained. This damage resulted in the hermit crabs inhabiting areas of the shell that were smaller in whorl diameter than the original aperture, and the vestiges of the columella increased the shell weight, such that the shells were now proportionally heavier for the smaller crab inhabitants. Despite this apparent shift in proportional weight, the shell most often used at this site was the same species as used at Lime Kiln (the next-most-exposed site, where the shells did not have such severe damage), rather than lighter-shelled species such as L. dirum or M. pupillus. Therefore, contrary to our initial hypotheses that hermit crabs in wave-exposed areas would inhabit heavier shells than used at more protected sites, it appears that the weight of the shell is not a major determining factor of its use.

Distribution of the hermit crab species among sites

Pagurus granosimanus was almost completely absent from both Cattle Point and Lime Kiln, our most exposed sites, and found only in the protected microhabitat at Westside Scenic Preserve (Figure 2). In contrast, our studies found P. beringanus at every site. These findings suggest that P. granosimanus is less tolerant of wave action than is P. beringanus. However, our research examined only five sites, and this small a sample size prevents the ability to draw strong conclusions as to the impact of wave exposure. Furthermore, our protected microhabitat areas tended to be slightly higher in tidal elevation and P. granosimanus inhabits higher intertidal heights than does P. beringanus (Vance, Reference Vance1972; Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a). Therefore, any potential pattern of differential wave exposure tolerance should be viewed conservatively, as it might be confounded by emersion time tolerance. It is possible that our collection areas at Cattle Point and Lime Kiln were just deeper than the tidal height typically inhabited by P. granosimanus, as we performed our collections on days with some of the lowest tides of the year, with their lowest points attaining depths of −0.86 to −0.5 m MLLW. Vance (Reference Vance1972) reported that P. granosimanus occurred to about −0.3 m MLLW and occasionally in the shallow subtidal at Cattle Point and Deadman Bay, while P. beringanus was primarily a subtidal species. However, because all of our collections were conducted within a few days of each other, and we made strong attempts to match tidal heights surveyed by matching surrounding biotic species, it is unlikely that tidal height alone drove the density differences of P. granosimanus among our sites. Additionally, at Deadman Bay and Westside Scenic Preserve P. granosimanus had a proportionally greater representation in the protected microhabitat, but not at Colin's Cove, the only other site where it was possible to statistically test this comparison (Table 4). While future studies involving vertical transects at each of our sites to replicate the previous methods of Vance (Reference Vance1972; at Cattle Point and Deadman Bay only) would be of interest, it appears that P. granosimanus is less tolerant of wave action than is P. beringanus.

Even if (perhaps especially if) our collections occurred at lower intertidal levels than previous authors reported as the typical range for P. granosimanus, our collections at our three sites with less wave exposure found many more co-occurring individuals of the two hermit crab species than did Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a), who recorded a >30:1 P. granosimanus to P. beringanus. This co-occurrence suggests that a shift in microhabitat distribution has occurred, with either P. granosimanus moving into deeper areas of the intertidal or P. beringanus moving its maximum range higher into the intertidal zone. We deem it more likely that P. granosimanus is inhabiting lower tidal heights given other reports of shifts in mean depth distribution and the possible elevated vulnerability of mid-intertidal species to rising air and water temperatures (Sagarin et al., Reference Sagarin, Barry, Gilman and Baxter1999; Harley et al., Reference Harley, Hughes, Hultgren, Miner, Sorte, Thornber, Rodriguez, Tomanek and Williams2006). While we hypothesize that increasing temperatures are contributing to a shift in the distribution of P. granosimanus, other factors including modifications of the local habitat or human use of the area may be the causative factor. However, our collections consistently found much higher proportions of co-occurrence of these two species than reported by Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) and others. Previous work has concluded that habitat partitioning occurring with both P. granosimanus and P. beringanus promoted their coexistence (Vance, Reference Vance1972), while our work finds these species co-existing across sites within the same microhabitat. Future studies in the shallow subtidal would be of interest to determine whether P. granosimanus has now extended its range to deeper than the intertidal zone.

Shell use by the hermit crabs

While past researchers working on San Juan Island have consistently found that P. beringanus and P. granosimanus use largely the same shells to the same degree, their specific claims as to which shells are disproportionately used have differed, and unfortunately they typically reported groupings of often-used and less-used shells, rather than proposing a ranked hierarchy. Vance (Reference Vance1972) found that both of our study species occurred principally in shells of N. lamellosa, N. canaliculata and L. dirum, with P. granosimanus also commonly inhabiting shells of N. ostrina and P. beringanus also often occupying A. columbiana and C. ligatum. Spight (Reference Spight1977), working at Colin's Cove, noted that hermit crabs rarely used available shells of L. dirum, hypothesizing that perhaps the hermit crabs avoid the thin shells. Instead, the hermit crabs tended to inhabit N. lamellosa and N. ostrina shells, with P. beringanus moving into monitored shells of only N. lamellosa (Spight, Reference Spight1977). In contrast, Vance (Reference Vance1972) found that L. dirum was a preferred shell of both P. beringanus and P. granosimanus. Vance's (Reference Vance1972) choice experiments with shell-less hermit crabs indicated that P. beringanus chose (from among our shell species) principally A. columbiana, L. dirum, N. canaliculata and N. lamellosa, while P. granosimanus selected mainly L. dirum, N. ostrina and N. lamellosa, and neither species of hermit crab utilized C. ligatum or M. pupillus to any great extent.

In contrast to both of these previous authors, we found that neither N. lamellosa nor L. dira was typically one of the most-used shells at any site. However, all of the shells mentioned by these authors were used at least occasionally in our studies. Similar to the previous studies just noted above, we found that both species were inhabiting similar shells. While there were typically significant differences in the proportionate use of shells, there was no clear shell that dominated shell use across all sites, which surprised us. While we predicted that shells with certain length:width aspect ratios or shell thicknesses/relative weights would be disproportionately used by hermit crabs in concert with the level of wave-exposure across microhabitats or sites, this pattern was not manifested. The identity of the most-used shells was largely congruent across the microhabitats within a particular site. While certain types of shell were significantly greater-utilized at each site, across sites the identity of those shells varied, and that variation did not match a reliable pattern according to wave-exposure levels. Lighter shells (such as L. dirum or M. pupillus) were not disproportionately used where there was less wave action, nor heavier shells (such as N. lamellosa) utilized in areas of heavier wave exposure. However, it is notable that N. canaliculata emerged as one of the most often-used shells across the three most wave-exposed sites, with this shell type barely appearing as a hermit crab domicile at Deadman Bay (yet used by both species), and not at all for either species at Colin's Cove. However, it is unlikely that this pattern is driven by the decreasing benefit of thicker shells at more wave-protected sites because N. lamellosa was one of the dominant shell types utilized at Colin's Cove by P. granosimanus. While it is intriguing that P. granosimanus used N. lamellosa at the two sites of low wave exposure and not at Westside Scenic Preserve, we only had large enough collections of this crab species at three sites and so cannot draw conclusions about patterns from these limited observations.

Lirabuccinum dirum was typically used to a low extent across sites, with the notable exception being at Deadman Bay where it was one of the most-used shells for P. granosimanus, and Westside Scenic Preserve where it was used to a moderate amount by both species. Similarly, M. pupillus and C. ligatum were typically used to a low extent across the sites, but again, in one site (Colin's Cove and Deadman Bay, respectively) these shells were most-used species. These site-specific notable differences may account for the apparent contrast in the findings of Vance (Reference Vance1972), Spight (Reference Spight1977) and our own. Indeed, while Spight (Reference Spight1977) found that P. beringanus at Colin's Cove inhabited exclusively shells of N. lamellosa, we found in our collections that M. pupillus was used more often as a domicile. Whether this shift away from the dominant use of N. lamellosa (as Vance, Reference Vance1972 also noted high use of this shell) represents an evolutionary shift in response to climate change or to alterations of predator densities (e.g. a recent outbreak of seastar wasting disease) or is merely an artefact of hermit crab shell choice being very variable across, and perhaps even within, sites, would be of interest for future study. Indeed, Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) noted that while field-collected smaller individuals of P. granosimanus preferred A. columbiana and L. dirum, larger individuals did not demonstrate significant differences in use among shell species (Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a). Across researchers, the conclusions as to which shells are used most often differ notably, perhaps driven by site-to-site variability that is difficult to recognize if only one or two sites are utilized by researchers and the animals show clear significantly disproportionate use, as they do here.

While live snails of A. columbiana do occur in the lower intertidal, the ideal habitat for this species is subtidal hard substrata, and it is locally abundant subtidally (Stone, Reference Stone1976). Still, this shell appeared in substantial numbers at all our intertidal sites except for Colin's Cove. Even more surprising, at Westside Scenic Preserve, a substantial portion of P. granosimanus inhabited shells of A. columbiana. This finding may suggest not only that individuals of P. beringanus move between the subtidal and intertidal depths, but they do so often enough to represent a source of this shell for their potential competitors that are more restricted to higher tidal heights, either by switching shells (voluntarily or as the result of lost battles) or perishing in the intertidal. Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) found in laboratory preference experiments that both P. beringanus and P. granosimanus preferred A. columbiana to L. dira to C. ligatum. Subtidal field surveys conducted by Abrams et al. (Reference Abrams, Nyblade and Sheldon1986) noted that the second-most used shell of Pagurus beringanus (after N. lamellosa) was A. columbiana. Perhaps P. beringanus may be moving perpendicular to the shoreline, crossing tidal zones (as Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981 notes for other species), and bringing Amphissa shells from the subtidal into the intertidal, which may even represent a source of this shell for P. granosimanus (such as at Westside Scenic Preserve). Alternatively, there may be substantial import of empty shells of this type to the intertidal, but this is unlikely given the lack of empty shells we found at these sites.

Increased competition likely between the hermit crab species

While the large overlap in species of shells used by Pagurus granosimanus and Pagurus beringanus suggests that inter-specific competition might be important, Vance (Reference Vance1972) concluded that partitioning of the physical habitat may be largely responsible for the co-existence of P. beringanus and P. granosimanus despite their similar shell preferences. Similarly, Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) concluded that interspecific competition, compared with intraspecific competition, of P. beringanus with P. granosimanus was insignificant. However, our findings suggest that there might be more inter-specific competition now, especially at sites of low wave action. We collected higher numbers of P. beringanus than did either Vance (Reference Vance1972) or Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) on a single collection. While this raw number might be due to our sampling at deeper tidal heights or for a longer time, we also collected a more even proportion of the two species of hermit crabs: while we found 41.6% P. granosimanus at Colin's Cove (of 149 total animals of the two species), Spight (Reference Spight1977) found 86.3% P. granosimanus at the neighbouring site Shady Cove (of 855 total individuals of our two study species). At Deadman Bay, we found 45.5% P. granosimanus (of 99 total), whereas Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) found exclusively P. beringanus at −0.7 m MLLW (of 12 total, although he found 88.5% P. granosimanus of 26 total at −0.3 m MLLW; our collections were close to −0.6 m MLLW), and Vance (Reference Vance1972) found only 5% P. granosimanus (of 19 total of our two study species) in deep tidepools in the lower intertidal at Deadman Bay. Pagurus granosimanus was collected sympatrically with P. beringanus in three of the seven locations. At the same time, we found that the two species of hermit crabs largely inhabited the same species and size ranges of shells (as also reported by Vance, Reference Vance1972). These findings imply that these two species of hermit crabs likely overlap more in their niches than previously reported.

The two species of hermit crabs largely utilized similar types of shells at each given site, even in terms of rank order (as presented herein) rather than reported as a cluster of often-used species (as reported by previous authors). Despite subtidal tendencies of P. beringanus and the pattern that shells of some snails, such as N. lamellosa, tend to be larger subtidally than in the intertidal (Iyengar, personal observations), P. granosimanus inhabited shells that were significantly longer than those of P. beringanus, although the absolute differences were slight (Figure 3). Not only was there no notable difference in the size of shells used between the two microhabitats, the variance of shell length within any shell species was surprisingly small. While P. beringanus is reported to reach sexual maturity in one year (Nyblade, Reference Nyblade1974), whether benthic P. granosimanus mirror that life history is unknown, although the two species develop through zoeal and megalope stages at similar rates (Nyblade, Reference Nyblade1974). While the maximum lifespan of our study species of hermit crabs appears unknown, other hermit crab species, including a congener, have been reported to live between 18 months and 5 years (Branco et al., Reference Branco, Turra and Souto2002; Mantelatto et al., Reference Mantelatto, Christofoletti and Valenti2005; Frameschi et al., Reference Frameschi, Andrade, Alencar, Teixeira, Fransozo, Fernandes-Góes and Fransozo2015). Therefore, it is likely that our collections contained multiple age classes. The relatively small variance in size of shells used (small error bars in Figure 3) suggest that either the hermit crabs grow rapidly enough in one year to attain close to their maximum size, or else young of the year are significantly smaller than one centimetre in length (our collection minimum size, although we did not see many at all that were smaller than this size) while 2-year-olds have attained the maximum size. Taken together, these findings suggest that the species of hermit crabs are likely competing for the same available shells; they cannot rely on ontogenetic stages necessitating different size-classes of shell to ameliorate competitive interactions.

Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a), studying the fate of released shells at Deadman Bay and Cattle Point, concluded that competition for shells is a spatially localized process, largely restricted to sheltered sites where empty shells aggregate and hermit crabs congregate. Vance (Reference Vance1972) found that habitat partitioning may be largely responsible for the co-existence of P. beringanus and P. granosimanus and for the evolution of their very similar shell preferences. Almost 50 years later, habitat partitioning between these two species appears to be shrinking as P. granosimanus is found more frequently in the low intertidal in overlapping microhabitats with P. beringanus, suggesting that interspecific competition may be rising. It is interesting that while P. granosimanus used N. canaliculata to a great extent in the protected microhabitat of Westside Scenic Preserve and P. beringanus often used this shell in the exposed microhabitat at this site, P. beringanus used this shell to only a small degree in the protected microhabitat, which may indicate localized competition (unfortunately statistical tests of independence for shell use across hermit crab species within a microhabitat were precluded due to overly small expected values). However, Pagurus beringanus occurs widely in the subtidal, and the population density of P. granosimanus in our studies was still greater higher in the intertidal than the level of the lowest low tides. Therefore, it is unclear whether the increased overlap recorded herein of these two species at the limits of their tidal distributions will exert effects large enough to drive alterations in the populations as a whole. Indeed, Nyblade (Reference Nyblade1974) experimentally removed P. granosimanus at sites on the outer coast of Washington to monitor whether zonation patterns of the other hermits would shift and they did not. But our observations of increased overlap in distribution occurred at our more protected sites, and all of our sites are much more protected than the outer coast sites utilized in Nyblade's (Reference Nyblade1974) studies. If the factors causing increased distributional overlaps continue, and occur throughout the biogeographic range, competition between P. beringanus and P. granosimanus may become important at sites with low amounts of wave action. Whether the increased sympatry is due to environmental alterations, evolutionary change, moderation of the local habitat, or some other factor, is unknown and warrants further investigation.

Because Spight (Reference Spight1977) noted extreme differences in hermit crab populations at one site across years, and Abrams (Reference Abrams1987a) documented a switch in relative proportion of P. granosimanus to a preponderance of P. beringanus at a tidal height close to that of our collections, we would advocate returning to resample and confirm that these patterns persist across years. A vertical elevational sampling regime at each of these sites would be best to elucidate whether P. granosimanus is widening its depth gradient, or merely shifting itself to lower levels, or whether P. beringanus is moving into higher tidal heights (which we think is unlikely, yet still possible).

Conclusion

These two species of hermit crabs are still utilizing the same species of shells at sites as noted by previous authors more than 30 years ago (e.g. Vance, Reference Vance1972; Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a). However, while there were significant differences in proportional use of shells at each site, there was almost never one clearly preferred type of shell used as a domicile, and the most-used species varied across sites. The different species of shells used at different sites did not accord well with our predictions based solely on wave exposure. The fact that the most-used shell varied across sites likely explains the conflicting statements of previous authors as to whether shells such as L. dirum are desired domiciles for these hermit crabs. Within a site, however, there was congruence, although not exact agreement, between the two microhabitats and the two species of hermit crabs in terms of the relative proportions used of the different types of shells.

Our findings suggest that P. granosimanus is expanding its range to slightly deeper areas, increasing its likelihood to reside sympatrically with P. beringanus more regularly. While previous authors (Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a) decided that interspecific competition paled in comparison with intraspecific competition, the reasoning for this was largely that the two species did not overlap much in their distribution within a site (Abrams, Reference Abrams1987a; although the study therein included sites where hermit crab population sizes were orders of magnitude greater than at any San Juan Island location). Our results indicate that there is now greater overlap between these two species than reported previously in the very low intertidal of less-wave-exposed sites with hard substrata. Abrams (Reference Abrams1987b) noted variation among sites in the proportion of shell competition that P. beringanus experienced from P. granosimanus, with a much lower proportion of inter-specific competition on San Juan Island as opposed to an outer coast site, which Abrams ascribed to an increased segregation of the species in the San Juan Islands. Our findings suggest that segregation may be decreasing, so a concomitant amount of inter-specific competition might be increasing and natural selection pressures may be shifting in this system.

While it is not clear from our data whether P. granosimanus has expanded its range deeper into the low intertidal or P. beringanus has moved its typically subtidal range higher in elevation, the former possibility seems more parsimonious given other reports of shifts in mean depth distribution and the possible elevated vulnerability of mid-intertidal, compared with subtidal, species to rising temperatures (Sagarin et al., Reference Sagarin, Barry, Gilman and Baxter1999; Harley et al., Reference Harley, Hughes, Hultgren, Miner, Sorte, Thornber, Rodriguez, Tomanek and Williams2006). These distributional shifts do not appear to have resulted in character displacement in shell species preference yet, as both species tend to use the same types of shells. Even species showing typical habitat separation can still have interspecific shell exchanges occurring at such high rates that shell resource partitioning is nullified and any low competition estimates that assumed minimal inter-habitat exchange would be invalidated (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett1981). Thus, interspecific conflict has likely elevated due to the increased sympatry of the two species. We think that such competitive interactions are occurring, although we are not sure if the interspecific competitive interactions are direct, interference competitive interactions that involve high amounts of shell exchanges, or are indirect, exploitative competitive interactions for the rare resources of empty shells. Future experiments specifically aimed at determining whether the shell use we documented in wild populations matches the preference of individual hermit crabs under conditions of excess resources or whether the hermit crabs are utilizing the only shells available would be of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the San Juan County Land Bank and Friday Harbor Laboratories for site access, James Russell for statistical advice, and Peter Abrams, Kathleen Conn and an anonymous reviewer for comments on the manuscript.

Financial support

We would like to thank the Crist Family Student Research Award in Biology Fund of Muhlenberg College and the Blinks-NSF REU-BEACON program of Friday Harbor Laboratories (grant number DBI-1262239) for financial support.