Introduction

Macrophytes are important ecosystem engineers in the marine environment. They commonly form extensive beds in coastal areas, thereby creating new habitats for a wide variety of organisms, including epiphytic algae as well as invertebrate and vertebrate animals. Living attached to or associated with these macrophytes, these animals benefit from access to food resources, protection from predators and natural environmental impacts, more stable abiotic conditions, or by using them as sites for reproduction and recruitment of larvae (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Norderhaug and Fredriksen2009; Thomaz & Cunha, Reference Thomaz and Cunha2010).

The malacofauna is one of the main invertebrate components of this fauna, and the gastropods are the most important, with high numbers of species and trophic diversity (Chemello & Milazzo, Reference Chemello and Milazzo2002; Rueda & Salas, Reference Rueda and Salas2003; Urra et al., Reference Urra, Ramírez, Marina, Salas, Gofas and Rueda2013). Macrophyte-associated gastropods have an important role in aquatic ecosystems as consumers or prey, constituting an important link between different trophic levels (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Crowder, Dumas and Burkholder1992; Heck et al., Reference Heck, Carruthers, Duarte, Hughes, Kendrick, Orth and Williams2008).

In the Brazilian coast, the brown algae Sargassum C. Agardh are among the most representative, especially in south-eastern Brazil (Széchy & Paula, Reference Széchy and Paula2000). With many different alien species registered in the region, such as Sargassum cymosum, Sargassum furcatum, Sargassum filipendula and Sargassum stenophyllum (Leite et al., Reference Leite, Tanaka and Gebara2007; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Grande, Filho and Jacobucci2018), this genus is marked by large fronds, high biomass and extensive branching, thus presenting a complex, highly variable morphology, with structural variations in frond size, number and size of stalks and branches, depending not only on species identity, but also on environmental variables, which generates intraspecific plasticity (Jacobucci & Leite, Reference Jacobucci and Leite2002; Leite et al., Reference Leite, Tanaka and Gebara2007). For the present study the sampled algae are collectively referred to hereafter as Sargassum.

Macrophyte-invertebrate associations are sensitive to human impacts, since contaminants can accumulate in these systems, resulting in a disequilibrium (Duarte, Reference Duarte2002; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Johnston and Poore2008; Waycott et al., Reference Waycott, Duarte, Carruthers, Orth, Dennison, Olyarnik, Calladine, Fourqurean, Heck, Hughes, Kendrick, Kenworthy, Short and Williams2009) with consequences for their many constituent species (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Johnston and Poore2008). Anthropogenic stress can directly affect individuals in molluscan assemblages, causing morphological and physiological alterations that may result in changes in population parameters (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Dunstan, Murdoch, Conroy, Roberts and Lake1994; Feldstein et al., Reference Feldstein, Kashman, Abelson, Fishelson, Mokady, Bresler and Erel2003), and also altering the species composition and community diversity (Sánchez-Moyano et al., Reference Sánchez-Moyano, Estacio, García-Adiego and García-Gómez2000; Terlizzi et al., Reference Terlizzi, Scuderi, Fraschetti and Anderson2005; Rumisha et al., Reference Rumisha, Elskens, Leermakers and Kochzius2012).

The present study aims to (1) characterize Gastropoda assemblages associated with Sargassum spp. beds at a historically impacted area in Brazil, highlighting the importance of these habitats for the establishment of gastropod juveniles, by illustrating the growth stages of the main species and (2) investigate the variation of gastropod densities, as well as macroalgae dry weight, at a small spatio-temporal scale, expecting that higher levels of gastropod densities will occur during the warmest months, and that macroalgae dry weight will positively influence the density of gastropods.

Materials and methods

Study area

The collections were performed at four sampling sites on the rocky shores of the Flamengo, Lamberto, Ribeira and Santa Rita beaches in Flamengo Bay (23°29′42″–23°31′30″S 045°05′–045°07′30″W), situated in the Ubatuba municipality, on the northern coast of the state of São Paulo, south-eastern Brazil (Figure 1). This bay is about 2.5 km in diameter and 18 km2 in surface area, with a maximum depth of 14 m, i.e. quite shallow. The bay is directly connected to the open sea in its southern part; it is a semi-confined system, dominated by coastal waters with moderate hydrodynamics (Lançone et al., Reference Lançone, Duleba and Mahiques2005). The Flamengo Bay is historically contaminated by differing types of pollutants, such as heavy metals and organic pollution, with a main source of contaminants located at the Saco da Ribeira (Figure 1), a highly impacted area of the bay with large state marinas and intense boating activity (CETESB, 2014, 2015, 2016).

Fig. 1. Flamengo Bay, with the locations of the four rocky shores where the algal fronds were collected. Inset (upper left) shows the position of the bay on the Brazilian coast, indicated by an arrow.

Sampling procedure

Sampling was performed monthly from March 2014 to February 2015 inclusive. In each month, six fronds of the brown alga Sargassum sp. were collected through snorkelling at each sampling site. The fronds were taken randomly from 1–4 m depth in order to avoid the effects of the tidal oscillation and placed in individual 0.2 mm mesh bags to prevent loss of the macrofauna. At each sampling site, the water temperature was also obtained at the time of sampling.

In the laboratory, the fronds were washed three times to remove all the associated fauna, which was then fixed in 70% ethanol. The fauna was sorted under a stereomicroscope, and the gastropods were separated to be identified at species levels (or best taxonomic resolution possible) and counted. For each species, all individuals were examined for the occurrence of different sizes, as growth series, which were photographed with a camera coupled to a Zeiss Discovery V8 stereomicroscope. Voucher specimens of these gastropod species are deposited in the Museum of Zoology of State University of Campinas (Unicamp).

During the washing process, other epibionts attached to the frond surfaces, including epiphytic algae, bryozoans and hydrozoans, were also removed. The Sargassum sp. fronds and these epibionts were dried separately at 70°C for 48 h and then weighed with a 0.001 g precision balance. The gastropod density was expressed in reference to the dry weight of the algae.

Data analysis

For the analysis in this study, months were divided into two main seasons, in accordance with climatic data from Ubatuba shore (Climate-data.org., 2016): a cool season, from May to October, and a warm season, from November to April.

Therefore, the densities and number of gastropod species, as well as the dry weight of Sargassum fronds and its epibionts, were compared among sites and seasons with a linear mixed effects model, considering two fixed factors: season (two levels: warm and cool) and area (four levels, corresponding to the Flamengo, Lamberto, Ribeira and Santa Rita shores), and as a random factor the months of sampling, that were nested in the season factor, in order to avoid temporal correlation of samples in each site and, thus, pseudoreplication (Pinheiro & Bates, Reference Pinheiro and Bates2000). The analysis was performed with the nlme package (Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Bates, DebRoy and Sarkar2018) and for significant results, a multicomparison a posteriori test was performed with the glht function of multcomp package (Hothorn et al., Reference Hothorn, Bretz and Westfall2008) in software R v3.2.3 (R Core Team, 2015). Data for gastropod densities, Sargassum and epibiont dry weights were transformed to log(x + 1).

A linear regression analysis was used to determine the relationship between Sargassum dry weights and gastropod abundances at each site, with gastropod abundance as the dependent variable. A Pearson linear correlation was used to investigate the relationship between gastropod densities and seawater temperature at each site during the year. All analyses were performed in software R v3.2.3 (R Core Team, 2015).

The homogeneity of variances and normality of data were checked by visual inspection of residuals.

Results

Macrophytes

Both Sargassum spp. and epibiont dry weights did not show any significant variation between warm and cool seasons, whereas Sargassum fronds presented a higher dry weight in Ribeira shore and a smaller one in Flamengo, with intermediate values in Lamberto and Santa Rita (Table 1: a, b, Figure 2). The variation of epibiont dry weight, despite being statistically significant for the interaction between season and site, did not show any significant differences in the a posteriori test (Table 1: a, b, Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Differences in gastropod densities (upper left), number of gastropod species (upper right), Sargassum spp. dry weight (lower left) and epibionts dry weight (lower right) among seasons and sites. Error bars indicate standard error. Bars of the same colour indicated by the same letter have mean values that are not significantly different among sites (P ≥ 0.05). Above the lines on top of pairs of bars with differente colours: ‘*’ indicates significant differences between seasons (P < 0.05) and ‘ns’ indicates lack of significant differences between seasons (P ≥ 0.05). Data transformation for gastropod density, Sargassum spp. dry weight and epibiont dry weight: log(x + 1).

Table 1. Linear mixed effects model results (a: Sargassum dry weight; b: epibiont dry weight; c: gastropod density; d: number of gastropod species)

Gastropods

A total of 142,996 individual gastropods were obtained, belonging to 68 species. The total gastropod abundance was highest at Ribeira, followed by Flamengo, Lamberto and Santa Rita in that order. The total number of species was higher at Flamengo (58 species), followed by Lamberto, Ribeira and Santa Rita, with 56, 53 and 43 species, respectively. The complete list of species and their total abundances at each site are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. List of gastropod species associated with Sargassum sp. and respective abundances at the four collecting sites

Gastropod densities varied between seasons and among sampling sites (Table 1: c; Figure 2), with the highest density values during the warm season for all sites except Flamengo, and with higher densities in Ribeira and Flamengo than in Lamberto and Santa Rita. The annual gastropod fluctuation showed the same pattern for all locations, with the highest densities primarily in March and April and between November and February, the periods with the highest seawater temperatures (Figure 3). At Flamengo Beach, the differences among months were less evident (Figure 3). At all sites, a significant and positive correlation was observed between gastropod density and water temperature, with a strong correlation at Lamberto, Ribeira and Santa Rita, and a weaker one at Flamengo (Pearson's correlation, Flamengo: t = 2.353, df = 10, P = 0.040, r = 0.597; Lamberto: t = 4.524, df = 10, P = 0.001, r = 0.820; Ribeira: t = 4.219, df = 10, P = 0.002, r = 0.800; Santa Rita: t = 3.100, df = 10, P = 0.011, r = 0.700).

Fig. 3. Left: annual fluctuations of seawater temperature and gastropod density (mean ± standard error). Right: total relative abundances of the four most abundant species at each collecting site.

A very similar pattern was observed for the number of species sampled at each site, with a higher mean number of species in Ribeira and Flamengo than in Lamberto and Santa Rita in both seasons. There was no significant variation in species number between seasons at any site (Table 1: d; Figure 2).

About 96% of the gastropods analysed in this study were from only six species, with Bittiolum varium as the most dominant at all sampling sites (Figure 3), followed in decreasing order of abundance by Caecum ryssotitum, Eulithidium affine, Mitrella dichroa, Alvania auberiana and Caecum brasilicum. The remaining 4% of the specimens were from the other 62 species, showing that this gastropod assemblage is composed of a few dominant and many rare species.

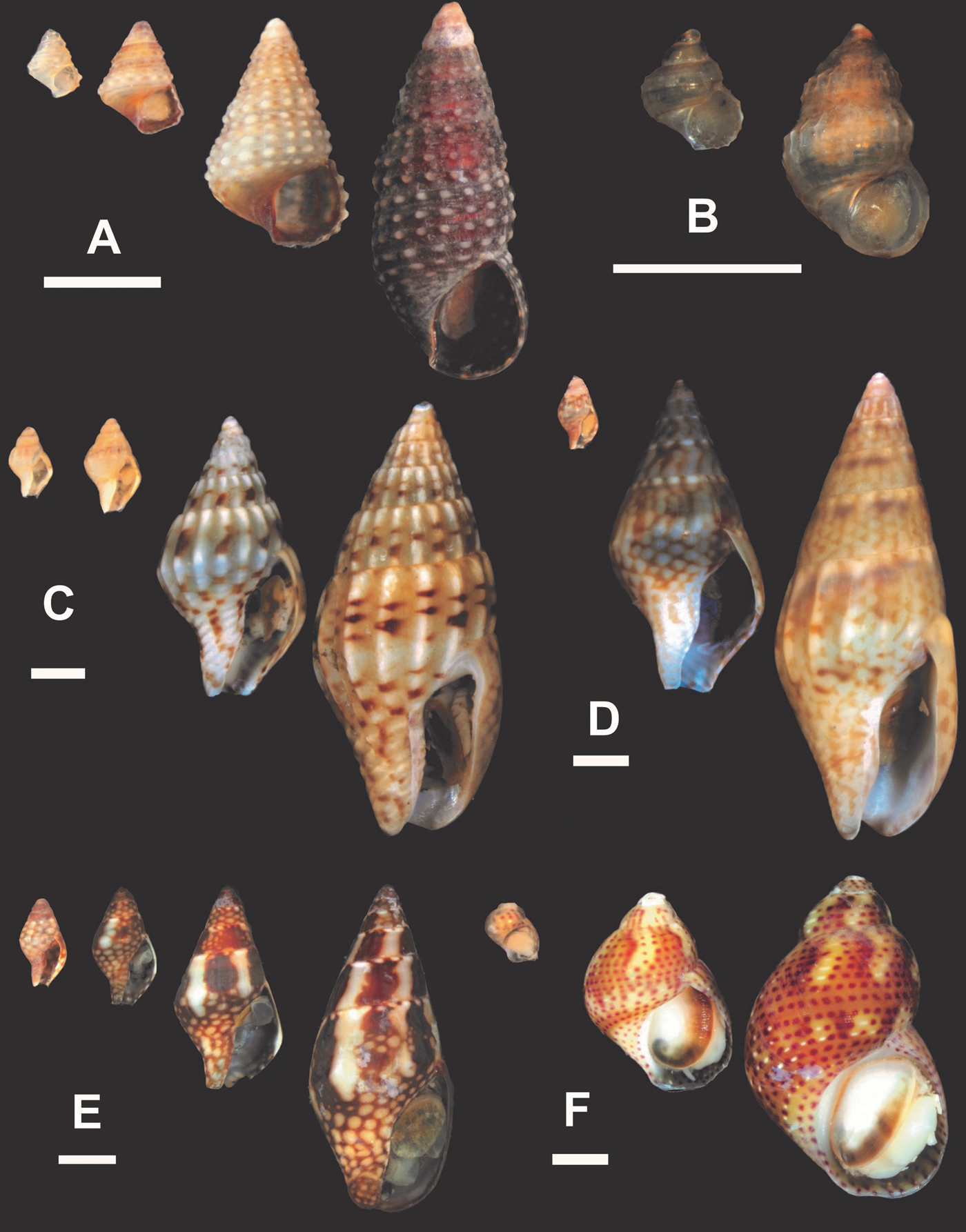

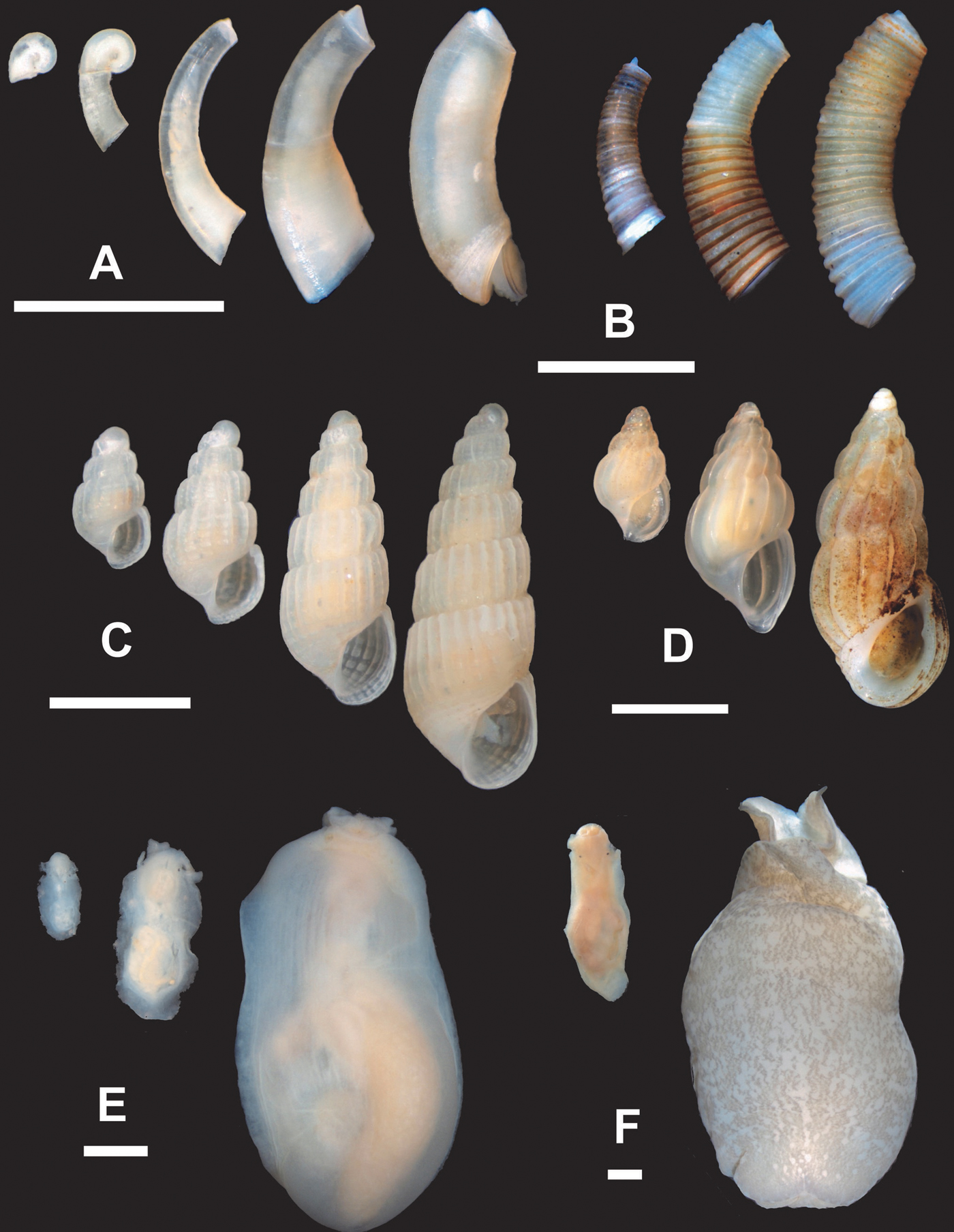

Both the common and rarer species showed high proportions of juveniles, as illustrated in the growth series in Figures 4, 5 and 6. For the most common species, Bittiolum varium, Caecum ryssotitum, Eulithidium affine and Mitrella dichroa, complete series were found, from the earliest juvenile stages to adults. For other species that are not typically found in these habitats, such as Stramonita brasiliensis and Leucozonia nassa, which are common on rocky shores, and Cerithium atratum, mostly found in soft bottoms, almost exclusively juvenile and sub-adult forms occurred.

Fig. 4. Species growth series. (A) Bittiolum varium; (B) Alvania uberiana; (C) Costoanachis sparsa; (D) Costoanachis sertulariarum; (E) Mitrella dichroa; (F) Eulithidium affine. Scale bar: 1 mm.

Fig. 5. Species growth series. (A) Caecum ryssotitum; (B) Caecum brasilicum; (C) Turbonilla multicostata; (D) Schwartziella bryerea; (E) Phyllaplysia engeli; (F) Navanax gemmatus. Scale bar: 1 mm.

Fig. 6. Species growth series. (A) Cerithium atratum; (B) Stramonita brasiliensis; (C) Fissurella rosea; (D) Nototriphora decorata; (E) Leucozonia nassa. Scale bar: 1 mm.

Another remarkable feature was the presence of gastropod species that are typically known as parasites, such as the Pyramidellidae (Wise, Reference Wise1996), with many species well represented in this study, i.e. Turbonilla multicostata, Boonea seminuda and Ioleae robertsoni. Those species could benefit from the other associated species found on these habitats acting as hosts (e.g. other molluscs, sedentary polychaetes, etc.), but that still remains unclear. Adult specimens of all pyramidellid species were rarely found.

Sargassum spp. dry weight and gastropod abundance were significantly and positively related at all sites, except Lamberto (Figure 7).

Fig. 7. Linear regressions between gastropod abundances and algal dry weight. Flamengo: y = 0.07x + 2.145, N = 72, F = 18.61, adjusted R 2 = 0.1987, P < 0.0001. Lamberto: y = 0.040x + 1.75, N = 72, F = 1.992, adjusted R 2 = 0.0138, P = 0.1626. Ribeira: y = 0.119x + 2.067, N = 72, F = 13.62, adjusted R 2 = 0.1509, P < 0.0001. Santa Rita: y = 0.060x + 1.434, N = 72, F = 4.283, adjusted R 2 = 0.0442, P = 0.0422.

Discussion

The gastropod fauna exhibited a clear temporal pattern of variation at all sampling sites in Flamengo Bay, with the highest densities during the warmest months of the year. Other studies of the gastropods associated with marine macrophytes have found temporal variations, and most recorded the highest abundances during the summer and/or spring periods (Leite & Turra, Reference Leite and Turra2003; Rueda & Sallas, Reference Rueda and Salas2003; Urra et al., Reference Urra, Ramírez, Marina, Salas, Gofas and Rueda2013).

The peak gastropod abundances during the warm season observed here were not influenced by the biomass of fronds in the Sargassum sp. beds, which did not show significant variation between the two seasons. This may be related to biotic factors, such as a higher recruitment rate during this period, as suggested by other studies on macrophyte-associated gastropod assemblages (Leite & Turra, Reference Leite and Turra2003; Arroyo et al., Reference Arroyo, Salas, Rueda and Gofas2006; Rueda et al., Reference Rueda, Urra and Salas2008), and reinforced here by a high presence of juveniles in this period (Longo, personal observation).

Furthermore, food sources for some species may increase during the warmer months. Organisms that form a biofilm on bottom surfaces grow faster in warmer temperatures (Villanueva et al., Reference Villanueva, Font, Schwartz and Romaní2011), which could benefit many gastropod populations associated with Sargassum spp. beds. Many of the gastropod species herein are microherbivores that feed on the biofilm established on the macrophyte fronds, including the most dominant species here, Bittiolum varium (Montfrans et al., Reference Montfrans, Orth and Vay1982) and, thus, those epiphytic diatoms and filamentous algal established on macroalgae surface may have an important role on gastropod assemblages (Amsler et al., Reference Amsler, Huang, Engl, McClintock and Amsler2015), that must be further investigated.

Differences were also observed in gastropod density and number of species among the four sampling sites in Flamengo Bay, with the higher values of both variables found in Ribeira and Flamengo. The Sargassum spp. populations from each site were morphologically different from each other (Longo, personal observation), possibly indicating different species, which could be influencing the variations on gastropod parameters. Distinct species identities, and thus distinct morphologies among Sargassum species, have already been related to differences in community parameters of amphipods (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Grande, Filho and Jacobucci2018) and molluscs (Veiga et al., Reference Veiga, Torres, Besteiro and Rubal2018). Even though the algal structure parameter in this study (algal dry weight) is probably not influencing the faunal differences found, since the two sites with the highest levels of gastropod density and number of species (Ribeira and Flamengo shores) had respectively the highest and lowest values of Sargassum dry weight, other unmeasured structural differences (e.g. number and size of branching) should be considered for an understanding of the importance of algal morphology and species identity on gastropod assemblages.

Also, other local differences of environmental parameters (e.g. hydrodynamic forces) could have an important role in the observed differences. Rubal et al. (Reference Rubal, Costa-Garcia, Besteiro, Souza-Pinto and Veiga2018), studying molluscan assemblages associated with the macroalga Asparagopsis armata in the Iberian Peninsula, raised the hypothesis that local differences found were due to environmental variables, and Tanaka & Leite (Reference Tanaka and Leite2003) have discussed the importance of the association of habitat complexity and physical conditions in the variations of gammarid assemblages living in Sargassum habitats at small spatial scales, while Jiménez-Ramos et al. (Reference Jiménez-Ramos, Egea, Vergara, Bouma and Brun2019) have experimentally demonstrated the importance of habitat structure and abiotic factors such as hydrodynamics, on the structuring of macrophyte ecosystems. Thus, the influence of environmental factors, in association with habitat complexity, may explain the differences found herein and should be further investigated in future studies.

Even though gastropod densities presented some variation throughout the four sampling sites, the dominance of B. varium in all sites of Flamengo Bay was remarkable. Although this species often occurs in association with macrophytes, such high dominance levels are unusual, both in studies with other macrophyte species (Leite et al., Reference Leite, Tambourgi and Cunha2009; Creed & Kinupp, Reference Creed and Kinupp2011; Barros & Rocha-Barreira, Reference Barros and Rocha-Barreira2013; Zamprogno et al., Reference Zamprogno, Costa, Barbiero, Ferreira and Souza2013; Queiroz & Dias, Reference Queiroz and Dias2014; Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Mota, Almeida, Pessanha, Christoffersen and Dias2015; García et al., Reference García, Bueno and Leite2015) and in studies with Sargassum sp. beds elsewhere on the Brazilian coast (Almeida, Reference Almeida2007; Jacobucci et al., Reference Jacobucci, Güth, Turra, Magalhães, Denadai, Chaves and Souza2006; Longo et al., Reference Longo, Fernandes, Leite and Passos2014).

A historical analysis of Flamengo Bay reveals that such high dominance levels of B. varium were not always observed. In an inventory of the gastropod species associated with Sargassum sp. beds in this area, Montouchet (Reference Montouchet1979) observed that other species such as Eulithidium affine and Astyris lunata showed the highest abundance levels, whereas B. varium comprised only 1.57% of the total ‘prosobranch’ gastropods. Later, Leite & Martins (Reference Leite and Martins1991), working in the same area, found a striking increase in B. varium dominance, with a 98% relative abundance. The time interval between these two studies was marked by anthropogenic modifications in this area, including a highway construction near the bay, the development of state marinas in the bay, and a regional increase in the human population (Buzato, Reference Buzato2012). The impact of these activities on Flamengo Bay may be affecting the local fauna, favouring the establishment and dominance of opportunistic species, such as the micrograzer B. varium.

The effects of anthropogenic impacts can frequently be observed in the diversity parameters of marine assemblages, resulting in lower evenness values and a higher dominance of one or a few species (Hillebrand et al., Reference Hillebrand, Bennett and Cadotte2008; Johnston & Roberts, Reference Johnston and Roberts2009). This pattern, associated with impacted areas, has been described for coastal molluscan assemblages (Terlizzi et al., Reference Terlizzi, Scuderi, Fraschetti and Anderson2005; Mendes et al., Reference Mendes, Soares-Gomes and Tavares2006; Amin et al., Reference Amin, Ismail, Arshad, Yap and Kamarudin2009) and could be observed in Flamengo Bay in recent decades, which indicates the effects of anthropogenic impacts in the area. The high dominance values of B. varium in this study suggest that these effects may have continued until the present time, an issue that is being further investigated (Longo et al., in prep.). Therefore, this result is in accordance with other studies that documented the vulnerability of gastropod–macrophyte systems under human-induced stress (Conti & Cecchetti, Reference Conti and Cecchetti2003; Terlizzi et al., Reference Terlizzi, Scuderi, Fraschetti and Anderson2005; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Johnston and Poore2008).

In Flamengo Bay, although a positive and significant relationship between the dry weight of Sargassum sp. fronds and gastropod abundance was observed in most periods, this relationship was weak. The importance of the macrophyte beds for the establishment and growth of their epifauna in general (e.g. Veiga et al., Reference Veiga, Rubal and Sousa-Pinto2014; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Veiga, Rubal and Souza-Pinto2015) and for gastropods specifically (e.g. Norton & Benson, Reference Norton and Benson1983; Vincent et al., Reference Vincent, Rioux and Harvey1991; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan, Liang and Wang2006) was demonstrated by the significant and highly positive relationship between the macrophyte biomass and the abundance of associated individuals. Veiga et al. (Reference Veiga, Torres, Besteiro and Rubal2018) demonstrated that, besides biomass, molluscan assemblages were also highly influenced by algal architecture, measured as the fractal area of each frond, a variable that could be included in future studies. Nevertheless, possibly other factors such as the anthropogenic impacts on Flamengo Bay (CETESB, 2014, 2015, 2016) may be limiting the occurrence of this fauna there, thus affecting the linear relationship between macrophytes and associated species. This hypothesis becomes stronger when we observe that in Lamberto Beach, the site closest to the polluted Saco da Ribeira, the Sargassum dry weight–gastropod abundance relationship was not significant.

The remarkable diversity of gastropods living in association with Sargassum spp. beds illustrated here, with a large occurrence of juvenile stages of the most common resident species as well as the less abundant species typical of other, nearby habitats, calls attention to the need to extend our knowledge of the biology and dynamics of these species, as well as to better understand the role performed by this macroalga in the establishment and development of the gastropod species, especially in impacted areas. Similar observations have already been made for molluscan assemblages associated to Cystoseira spp., another canopy-forming brown alga, from other localities (Pitacco et al., Reference Pitacco, Orlando-Bonaca, Mavrič, Popović and Lipej2014; Lolas et al., Reference Lolas, Antoniadou and Vafidis2018). Those numerous juvenile forms found could indicate that macroalgae such as Sargassum sp. provide a favourable environment for the development of gastropods, acting as a nursery, as has been well established for other invertebrate and vertebrate groups (Haywood et al., Reference Haywood, Vance and Loneragan1995; Perkins-Visser et al., Reference Perkins-Visser, Wolcott and Wolcott1996; Cocheret de la Morinière et al., Reference Cocheret de la Morinière, Pollux, Nagelkerken and Van der Velde2002; Heck et al., Reference Heck, Hays and Orth2003; Bulleri et al., Reference Bulleri, Airoldi, Branca and Abbiati2006). Further investigations are needed for gastropod assemblages, since most studies have focused on a few species, such as Strombus gigas (Stoner, Reference Stoner2003).

The generation of further information on the highly diverse gastropod assemblages associated with macrophyte habitats, their structure patterns in impacted areas such as Flamengo Bay, and the interactions between gastropods and macroalgae will enable the development and implementation of effective conservation measures for these ecologically important habitats formed by macrophyte beds in coastal regions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the northern Clarimundo de Jesus Research Base (Oceanographic Institute, University of São Paulo), as well as all the technicians, for their help and support during the collecting process; A. Mouro, A.P. Ferreira and M.B. Fernandes, for help with material processing and/or data analysis; A.L. Lorenço, V. Vicente and I. Capistrano for valuable help with material processing; members of the LICOMAR – Unicamp, for their help during collection, processing and discussions; D. Zaya, for helping with the photographs; P.V.F. Corrêa for designing the map; and C.M. Cunha and L. Souza for their help during the identification process.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).