Introduction

The Strait of Sicily is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea and connects the eastern and the western basins. Thanks to its geographic position, it represents a crossroads between the two basins for range expanding species coming from the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar as well as for Lessepsian species (i.e. species immigrating from the Red Sea through the Suez Canal) (Guidetti et al., Reference Guidetti, Giardina and Azzurro2010), although only few of the latter have crossed the Strait of Sicily entering the western basin (Falautano et al., Reference Falautano, Castriota and Andaloro2006). The two most important archipelagos of the Strait of Sicily are the Maltese Islands and the Pelagie Islands that, for their typical biogeographic and hydrodynamic features, are strategic observation outposts for the monitoring of non-indigenous species (Azzurro et al., Reference Azzurro, Ben Souissi, Boughedir, Castriota, Deidun, Falautano, Ghanem, Zammit-Mangion and Andaloro2014a). Among these species we can count the Atlantic Seriola carpenteri (Pizzicori et al., Reference Pizzicori, Castriota, Marino and Andaloro2000), Seriola rivoliana (Castriota et al., Reference Castriota, Greco, Marino and Andaloro2002), Cephalopholis taeniops (Guidetti et al., Reference Guidetti, Giardina and Azzurro2010), as well as the Lessepsian Siganus luridus (Azzurro & Andaloro, Reference Azzurro and Andaloro2004), Hemiramphus far (Falautano et al., Reference Falautano, Castriota, Battaglia, Romeo and Andaloro2014), Etrumeus golanii (Falautano et al., Reference Falautano, Castriota and Andaloro2006 as E. teres) and Lagocephalus sceleratus (Azzurro et al., Reference Azzurro, Castriota, Falautano, Giardina and Andaloro2014b). Recently, findings of species not recorded before in the Strait of Sicily became more frequent thanks to the cooperation of fishermen who promptly inform researchers if they capture organisms that they have never fished before. This happened also for the finding of the African sailfin flying fish Parexocoetus mento, caught for the first time in Italian waters near Lampedusa Island (Strait of Sicily), in November 2017. According to Froese & Pauly (Reference Froese and Pauly2020), three species belong to the genus Parexocoetus Bleeker, 1865, but they have long been confused with each other in the literature. However, based on the more recent descriptions of such species, P. mento can be distinguished from the other two species by defined characteristics, as discussed below. Parexocoetus mento is a Lessepsian immigrant that has a wide natural distribution range, occurring in the Indian and Pacific Oceans from East Africa, including the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, to southern Japan, Marshall Islands, Fiji Islands and Queensland (Australia) (Parin, Reference Parin1996).

Parexocoetus mento is a tropical epipelagic schooling species inhabiting neritic and inshore areas and more rarely surface waters of the open ocean, being capable of leaping out of the water and gliding over a long distance (Golani et al., Reference Golani, Orsi-Relini, Massuti and Quignard2002). Its diet is based on zooplanktonic organisms, mostly copepods (Tsukahara & Shiokawa, Reference Tsukahara and Shiokawa1957), while the larger specimens also feed on small fishes (Parin, Reference Parin1996). This species becomes sexually mature at 93.3–104.7 mm standard length (SL) (98–110 mm fork length (FL) for males and females respectively) and reaches a maximum size of 122.1 mm SL (123–130 mm FL for males and females respectively) (Tsukahara & Shiokawa, Reference Tsukahara and Shiokawa1957; Dasilao et al., Reference Dasilao, Rossiter and Yamaoka2002). Like other flying fishes, it is caught accidentally in purse seines, driftnets and pelagic trawls, and has no commercial value.

The present paper documents the first record of P. mento in the Strait of Sicily as well as for Italian waters. Furthermore, mapping and monitoring the distribution of invasive species is crucial to understand their spread, potential establishment, and then to manage the invasion process. Therefore, occurrences of P. mento in the Mediterranean are analysed in order to provide an overview of spatial distribution and to identify directional trends of spread.

Materials and methods

Data collection and species identification

On 25 November 2017, a specimen of flying fish was caught in the coastal waters of Lampedusa Island, Strait of Sicily (35°29′49.15″N 12°35′28.99″E). The specimen was fished in the early morning, at a depth of 15 m, together with several individuals of Belone sp. (weighing in total 20 kg), by a small surrounding net without purse line targeting needlefish (Belonidae), locally called ‘agugliara’. The fisherman, who had never seen a fish like this, took a photo (Figure 1) and preserved the specimen by freezing it. The specimen was identified as the African sailfin flying fish Parexocoetus mento (Valenciennes, 1846) according to the more recent descriptions from the literature (Parin, Reference Parin1996; Reference Parin, Carpenter and Niem1999; Reference Parin and Carpenter2003; Parin & Shakhovskoy, Reference Parin, Shakhovskoy, Carpenter and De Angelis2016; Collette et al., Reference Collette, Bemis, Parin and Shakhovskoy2019). The specimen was measured considering total length (TL), standard length (SL), fork length (FL) and sizes related to head length (HL). Measurements were taken by fish measuring board to the millimetre below, except for HL and referred measures that were taken by calliper to the lowest 0.1 mm. As for meristic counts, the number of rays for the dorsal, pectoral, ventral and anal fins as well as the predorsal scales were recorded. Morphometric and meristic data were then compared with those reported in the literature for this species (Day, Reference Day1878; Schultz et al., Reference Schultz, Herald, Lachner, Welander and Woods1953; Tsukahara & Shiokawa, Reference Tsukahara and Shiokawa1957; Avsar & Cicek, Reference Avsar and Cicek2000; Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Rath and Dash2010).

Fig. 1. Specimen of Parexocoetus mento from Lampedusa Island.

The specimen collected was preserved in 80% alcohol and stored in the ichthyological collection of the Museum of Zoology ‘P. Doderlein’ of Palermo, under the code PL391-MZPA.

In order to verify the status of the first record of this species in Italian waters, according to the recommendations of Bello et al. (Reference Bello, Causse, Lipej and Dulčić2014), the most updated alien species datasets (Servello et al., Reference Servello, Andaloro, Azzurro, Castriota, Catra, Chiarore, Crocetta, D'Alessandro, Denitto, Froglia, Gravili, Langer, Lo Brutto, Mastrototaro, Petrocelli, Pipitone, Piraino, Relini, Serio, Xentidis and Zenetos2019; Tsiamis et al., Reference Tsiamis, Palialexis, Stefanova, Ničević Gladan, Skejić, Despalatović, Cvitković, Dragičević, Dulčić, Vidjak, Bojanić, Žuljević, Aplikioti, Argyrou, Josephides, Michailidis, Jakobsen, Staehr, Ojaveer, Lehtiniemig, Massé, Zenetos, Castriota, Livi, Mazziotti, Schembri, Evans, Bartolo, Kabuta, Smolders, Knegtering, Gittenberger, Gruszkas, Kraśniewski, Bartilotti, Tuaty-Guerra, Canning-Clode, Costa, Parente, Botelho, Micael, Miodonski, Carreira, Lopes, Chainho, Barberá, Naddafi, Florin, Barry, Stebbing and Cardoso2019) as well as the species lists of the Italian museums' ichthyological collections available online have been consulted.

Measuring P. mento geographic distribution in the Mediterranean Sea by GIS-based spatial statistics

In order to understand the spreading of P. mento in the Mediterranean, a spatial and temporal distribution analysis was carried out. Parexocoetus mento occurrences data were obtained from the literature, also including the present record. The spatial data and their attributes were carried out under Geographic Information Systems (GIS) using ArcGIS 10.3 ESRI and its extensions.

According to Lipej et al. (Reference Lipej, Mavric and Paliska2013), the dataset was processed using the year of first record within a 0.5 degree Lat/Long grid, since considering subsequent records in the same grid cell can lead to an error for distribution modelling (Gabrosek & Cressie, Reference Gabrosek and Cressie2002).

GIS-based analysis was focused on the following aspects: (i) analysing distribution patterns and identifying species direction spread and settled areas; (ii) describing and modelling P. mento spatial and temporal distribution. All these analyses were carried out using ArcGIS Spatial Statistics tools, an important set of exploratory techniques for understanding the spatial and temporal occurrence distribution of P. mento.

GIS-based spatial statistics allowed us to: assess overall patterns of clustering or dispersion; recognize aggregation patterns and statistically significant spatial structures; identify groups of features with similar characteristics based on year of occurrence; and summarize the distribution key characteristics for each group identified (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2005; Scott & Janikas, Reference Scott, Janikas, Fischer and Getis2010).

In order to study the aggregation patterns and the spatial structure of the occurrences, spatial autocorrelation through Global Moran's I, GMI and cluster and outlier analysis through Anselin local Moran's I, AMI were carried out. The GMI statistic method works on feature ‘locations’ and feature value ‘year’ simultaneously, evaluating if distribution patterns are clustered, dispersed or random. High spatial autocorrelation occurs when Moran's Index is close to + 1 (Anselin, Reference Anselin1995). AMI, with the search threshold for neighbours within 300 km, was also analysed to identify statistically significant spatial clusters of high and low values (groups of similar occurrences positioned closely together) or outlier records (a high value enclosed within low values and vice versa).

In order to describe distribution key characteristics and track their changes over time and space, grouping analysis based on the attribute ‘year’ was made to identify occurrences with similar characteristics. Subsequently the indicators of Central Tendency, species Spatial Dispersion, Directional Dispersion and Directional Trend were calculated on the identified time groups using the Measuring Geographic Distributions toolset in ArcGIS Spatial Statistics (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2005; Scott & Janikas, Reference Scott, Janikas, Fischer and Getis2010).

These spatial indicators allowed the following ecological questions to be addressed:

– Where is the species concentration? Do these locations change over time?

Changes in Central Tendency reflect variations in P. mento distribution over time and/or space. This indicator was calculated such as the Mean Centre (arithmetic average of the coordinates) and the Median Centre geographic points (middle value of the longitudes and the latitudes) (Desktop ESRI ArcGIS, 2011).

– Is species distribution dispersed or compact?

The Spatial Dispersion shows if records are spatially concentrated or dispersed around the geometric Mean Centre: the shorter the Standard Distance (i.e. the radius of the generated circumference), the more concentrated the distribution (Desktop ESRI ArcGIS, 2011).

– Is distribution elongated? In which direction does it extend?

Two spatial indicators, directional dispersion and directional trends, allow to understand the shape in X and Y directions and orientation of distribution. The first is the standard distance of x- and y-coordinates, calculated separately in the x- and y-directions (Standard Deviational Ellipse). The last represents the rotation of the ellipse long axis, measured clockwise from noon (Desktop ESRI ArcGIS, 2011).

Results

Description and identification

The fresh specimen exhibited the following characters: body elongated, compressed, bluish dorsally and silvery ventrally; eyes large and upper jaw protrusible; dorsal fin in rear position, almost opposite to anal fin, scarcely reaching the insertion of the upper caudal fin lobe, showing pale base and broad black pigmentation in its terminal part; pectoral fins greyish and very long, reaching about the first third of the anal fin base; anal fin transparent; caudal fin forked with dark lower lobe longer than upper lobe that, conversely, is transparent (Figure 1).

The specimen measured 137 mm TL; all morphometric and meristic characters are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Morphometric data and meristic characters of the African sailfin flying fish Parexocoetus mento caught in Italian waters off Lampedusa Island in November 2017

Data ranges drawn from literature (Day, Reference Day1878; Schultz et al., Reference Schultz, Herald, Lachner, Welander and Woods1953; Tsukahara & Shiokawa, Reference Tsukahara and Shiokawa1957; Parin, Reference Parin, Whitehead, Bauchot, Hureau, Nielsen and Tortonese1986; Avsar & Cicek, Reference Avsar and Cicek2000; Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Rath and Dash2010).

GIS-based spatial and temporal distribution of P. mento in Mediterranean Sea

The first record of the African sailfin flying fish in the Mediterranean Sea occurred off Palestine (Bruun, Reference Bruun1935), and it has since been recorded from Greece (Kosswig, Reference Kosswig, Von Jordans and Peus1950; Ben-Tuvia, Reference Ben-Tuvia1966; Papaconstantinou, Reference Papaconstantinou1987; Zachariou-Mamalinga, Reference Zachariou-Mamalinga1990) and elsewhere in the Aegean Sea (Zaitsev & Ozturk, Reference Zaitsev and Ozturk2001), Israel (Ben-Tuvia, Reference Ben-Tuvia1966), Libya (Ben-Tuvia, Reference Ben-Tuvia1966; Elbaraasi et al., Reference Elbaraasi, Elabar, Elaabidi, Bashir, Elsilini, Shakman and Azzurro2019), Lebanon (George & Athanassiou, Reference George and Athanassiou1967; Bariche et al., Reference Bariche, Sadek, Al-Zein and El-Fadel2007), Syria (Saad, Reference Saad2005), Turkey (Avsar & Cicek, Reference Avsar and Cicek2000; Meric et al., Reference Meric, Eryilmaz and Oezulug2007; EastMed, Reference EastMed2010), Albania (Parin, Reference Parin, Whitehead, Bauchot, Hureau, Nielsen and Tortonese1986), Cyprus (EastMed, Reference EastMed2010), Egypt (El Sayed, Reference El Sayed1994; El-Haweet, Reference El-Haweet2001) and Tunisia (Ben Souissi et al., Reference Ben Souissi, Zaouali, Bradai and Quignard2004; Bradai et al., Reference Bradai, Quignard, Bouain, Jarboui, Ouannes-Ghorbel, Ben Abdallah, Zaouali and Ben Salem2004). After this record no specimen has been detected in this area between the coasts of North Africa and the southern Sicily.

Spatial global autocorrelation of the P. mento records in the Mediterranean Sea (at global spatial scale) was found (GMI = 0.32, z = 3.72). The positive value of GMI indicates that the set of data (year of first records within the 0.5 degree grid) showed a cluster model. The distribution of records at nearby locations is not random and there is a spatial grouping of values. However, the spatial autocorrelation for the entire study area was weak indicating a change in the spatial pattern of P. mento records over time. Figure 2 provides an overview of AMI. At a local spatial scale, an area along the coasts of the eastern basin showed a statistically significant clustering of low values (corresponding to the first records of P. mento in the Mediterranean Sea). The other records had non-significant index values, and no high cluster areas or spatial data outliers were detected.

Fig. 2. Anselin local Moran's I – Cluster and Outlier Analysis identifying areas with statistically significant spatial clustering of records of Parexocoetus mento in Mediterranean Sea. No spatial Outliers or High Cluster areas are detected. The first occurrence (1935) and the last (2017), in Italian waters off Lampedusa Island, are also reported.

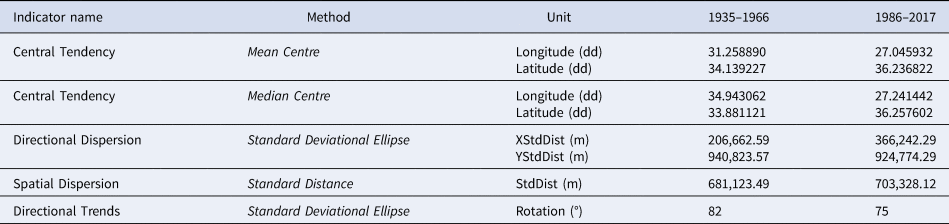

Grouping analysis identified two groups of similar features: 1935–1966 and 1986–2017 time periods. The Central Tendency (such as Mean Centre and Median Centre), Spatial Dispersion, Directional Dispersion and Trends were therefore calculated and mapped for the two intervals previously reported. The values of these indicators are shown in Table 2 and in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Distribution key characteristics of Parexocetus mento in the Mediterranean Sea. The central tendency, such as Mean and Median Centre, Spatial Dispersion, Directional Dispersion and trends, was calculated for every interval, indicating distribution changing in spatial and time. The first occurrence (1935) and the last (2017), in Italian waters off Lampedusa Island, are also reported.

Table 2. Values of the spatial indicators of Parexocoetus mento records distribution in the Mediterranean Sea calculated per time period: Central Tendency (Mean and Median Centre), Spatial Dispersion, Directional Dispersion, Directional Trends

From 1935, i.e. the year of the first record in the Mediterranean, to 1966 the Central Tendency, measured as Mean Centre, was in the middle of Levantine Basin, while the Median Centre was along the east coast, where the greatest number of records were concentrated. In this case the Median Centre was a more representative measure of Central Tendency than the Mean Centre, since the algorithm for the Median Centre tool was less influenced by distant and isolated records than the Mean Centre. In the 1986–2017 period, the Central Tendency point was localized near the coast of Turkey; both Median and Mean Centres were in close proximity. The Spatial Dispersion indicator was similar in both periods, but showed a change over time and space: the dispersion circumference of distribution in the second period moved westward.

Also, the shape of distributions in X and Y directions (Directional Dispersion) and the orientation (Directional Trends), showed a change over the two periods. Both ellipses were elongated from east to west and their direction extended southward, towards the centre of the Mediterranean Sea (Strait of Sicily).

However, in the 1986–2017 period, the X Standard Deviation was greater than that of the 1935–1966 period, due to the major dispersion of occurrences in the latter period.

Discussion

In the Mediterranean, the family Exocoetidae is represented by seven recognized genera (Cheilopogon Lowe, 1841; Cypselurus Swainson, 1838; Exocoetus Linnaeus, 1758; Fodiator Jordan & Meek, 1885; Hirundichthys Breder, 1928; Parexocoetus Bleeker, 1865; Prognichthys Breder, 1928). The genus Parexocoetus can be distinguished from all the other genera by the protrusible upper jaw, the snout shorter than eye diameter, the length of the pectoral fin not reaching beyond the posterior part of the anal fin. This genus includes three species – P. brachypterus (Richardson, 1846), P. hillianus (Gosse, 1851) and P. mento (Valenciennes, 1847). However, the differences between the first two species are so fine that P. hillianus has been frequently synonymized/misidentified with, or considered as a subspecies of P. brachypterus (Fowler, Reference Fowler1944; Collette et al., Reference Collette, McGowen, Parin, Mito, Moser, Richards, Cohen, Fahay, Kendall and Richardson1984, Parin, Reference Parin and Carpenter2003; Parin & Shakhovskoy, Reference Parin, Shakhovskoy, Carpenter and De Angelis2016). According to the more recent descriptions of these species (Parin, Reference Parin1996, Reference Parin, Carpenter and Niem1999, Reference Parin and Carpenter2003; Parin & Shakhovskoy, Reference Parin, Shakhovskoy, Carpenter and De Angelis2016; Collette et al., Reference Collette, Bemis, Parin and Shakhovskoy2019), P. mento can be distinguished from the other two species for the following characters: dorsal fin with much black pigment, the longest rays scarcely reaching the origin of the upper caudal lobe (basally pale and distally black in the other two species, the longest rays reaching beyond the base of caudal fin); pectoral fin greyish (transparent in the other two species, except the very upper portion which is grey), lower caudal lobe greyish (transparent in the other two species). As for meristic characters, the three species are not always distinguishable because of overlapping values, although P. mento, compared with the other two species, generally shows a lower number of dorsal (9–12 vs 11–14) and anal (10–12 vs 12–15) rays, as well as of predorsal scales (16–21 vs 19–25), and a higher number of pectoral rays (13–15 vs 11–13). The specimen examined in the present paper showed the morphological features of P. mento and the size (i.e. 110 mm SL, 116 mm FL) was comparable to that of an adult individual. Both the morphometric and meristic characters of the specimen corresponded with those reported in the literature for this species, except for snout length (preorbital distance) and eye diameter (% head length) that resulted slightly higher. However, this result reflects the ontogenetic changes that this species undergoes during development from the juvenile to adult stage in the shape of the head and body, the elongation of the snout and the shortening of the head being some of these substantial changes (Dasilao et al., Reference Dasilao, Rossiter and Yamaoka2002).

Parexocoetus mento is listed among invasive species (Karachle et al., Reference Karachle, Corsini Foka, Crocetta, Dulčić, Dzhembekova, Galanidi, Ivanova, Shenkar, Skolka, Stefanova, Stefanova, Surugiu, Uysal, Verlaque and Zenetos2017) although its ecological and economic impacts are unknown. This finding represents the first record of this species in Italian waters as well as in the Strait of Sicily where, unlike in the Levant Basin, it has not established self-sustainable populations.

The GIS-based analysis of spatial and temporal distribution of the records of P. mento in the Mediterranean Sea allowed us to identify significant dispersion/clustering spatial areas of this species and changes over time in spatial pattern, as confirmed by the weak global spatial autocorrelation recorded. The separation of the occurrences in two groups with similar characteristics was predictable, given that no occurrences were reported in the Mediterranean for a long intervening period of time (from 1967 to 1985). At a local scale, the statistically significant clustering of earlier records represented the direction of spread along the eastern Mediterranean coast in the three decades after the very first record in 1935. Such an earlier spread direction was also recorded for another Lessepsian fish, i.e. Fistularia commersonii, for which a western distribution shift along the southern Mediterranean coast has also been reported (Azzurro et al., Reference Azzurro, Soto, Garofalo and Maynou2013). Whilst this second trend was not evidenced for P. mento, this was probably due to the scarcity of documented records in that area, and so cannot be discounted.

A settlement area of P. mento has been identified in the south-east Aegean Sea where the species has become more constantly present over time and potentially established, according to Lipej et al. (Reference Lipej, Mavric and Paliska2013). Otherwise, the occurrences along the north African coast, from Egypt to Tunisia, should be considered as casual since they are dispersed in space and time. A westward spread of P. mento towards the Strait of Sicily has been detected, as confirmed by the directional dispersion ellipses which indicated a spatial trend over time. Such a trend suggests the possibility of P. mento becoming established in the Strait of Sicily, considering that it has been recorded several times in neighbouring areas along the Tunisian and Libyan coasts. In this case, according to the pattern of spread recorded for other Lessepsian species (Azzurro et al., Reference Azzurro, Soto, Garofalo and Maynou2013), it is not excluded that the species could also spread to the western Mediterranean basin in the future.

The study stressed the importance of recording invasive species occurrences in new areas as well as subsequent records in the same area, in order to better detail the invasion process and to identify new areas of spread and establishment. Considering the rapid diffusion and potential impacts of invasive species on the biodiversity of the Mediterranean, the application of distribution studies may support the processes of management and risk prevention.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the fisherman Giovanni Billeci for providing the specimen.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.