Background

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) is a small cetacean species obligatory to the tropical/subtropical estuarine and inshore waters ranging from south China in the east to the Bay of Bengal in the west (Jefferson & Curry, Reference Jefferson and Curry2015). Unlike other humpback dolphin species, the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin lacks a dorsal hump (as compared with the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin S. plumbea and the Atlantic humpback dolphin S. teuszii) and exhibits a particular colour pattern (as compared with the Australian humpback dolphin S. sahulensis) (Jefferson & Rosenbaum, Reference Jefferson and Rosenbaum2014). Even though the current taxonomy of humpback dolphins cannot fully address the spatial genetic pattern of the entire genus (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Sakornwimon, Lin, Zhang, Chantra, Dai, Aierken, Wu, Li, Kittiwattanawong and Wang2021), it is generally accepted that the humpback dolphins found along the Chinese coast represent a single species (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zhou, Porter, Chen and Wu2010; Mendez et al., Reference Mendez, Jefferson, Kolokotronis, Krützen, Parra, Collins, Minton, Baldwin, Berggren and Särnblad2013; Jefferson & Curry, Reference Jefferson and Curry2015).

In Chinese waters, the spatial distribution of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins is patchy. Several distinct populations have been described in the South- and East China Sea, including one in the Dafeng River estuary off Guangxi province (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Jefferson, Olson, Qin, Zhang, He and Yang2016; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zheng, Liu, Chen, Lin, Liu, Liu and Li2022), one large population extending from the Pearl River Estuary (Lingding Bay, Jefferson, Reference Jefferson2000) to Jiangmen waters (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Hung, Xu and Chen2019), with a linear distance of over 180 km (which was called Pearl River Delta region according to Karczmarski et al., Reference Karczmarski, Huang, Or, Gui, Chan, Lin, Porter, Wong, Zheng, Ho, Chui, Tiongson, Mo, Chang, Kwok, Tang, Lee, Yiu, Keith, Gailey and Wu2016) off mid-Guangdong province, one population off the east coast of Leizhou Peninsula (including both Leizhou Bay, Guangzhou Bay and the connecting waters, Xu et al., Reference Xu, Song, Zhang, Li, Yang and Zhou2015), two populations at both sides of Taiwan Strait (Xiamen Bay and the western Taiwan Coast, Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang, Fruet, Daura-Jorge and Secchi2012a; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Lin, Dai, Zhong, Wang and Zhu2020), and one off the west side of Hainan Island (Li et al., Reference Li, Lin, Xu, Xing, Zhang, Gozlan, Huang and Wang2016). Small populations (<20 individuals) were also reported off Shantou city (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Miao, Wu, Yan, Liu and Zhu2012b) and Ningde city (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zheng, Wang, Xu and Yang2012). In addition to these described populations, several by-catches and stranding were reported in the temperate region since the 1980s (including the Yellow Sea and the Yangtze River mouth, Han et al., Reference Han, Ma, Wang and Dong2003, Reference Han, Ma, Dong and Wang2004). However, because no live sightings were reported in the past two decades in these areas (Park et al., Reference Park, Kim and Zhang2007, Reference Park, Sohn, An, Kim and An2015; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Fan, Tang, Zhang, Wang, Li, Yu, Zhu, Dong, Zhou and Zhao2014; Zuo et al., Reference Zuo, Sun, Shi and Wang2018), these animals were considered to be stray individuals (Han et al., Reference Han, Ma, Wang and Dong2003).

Sighting description

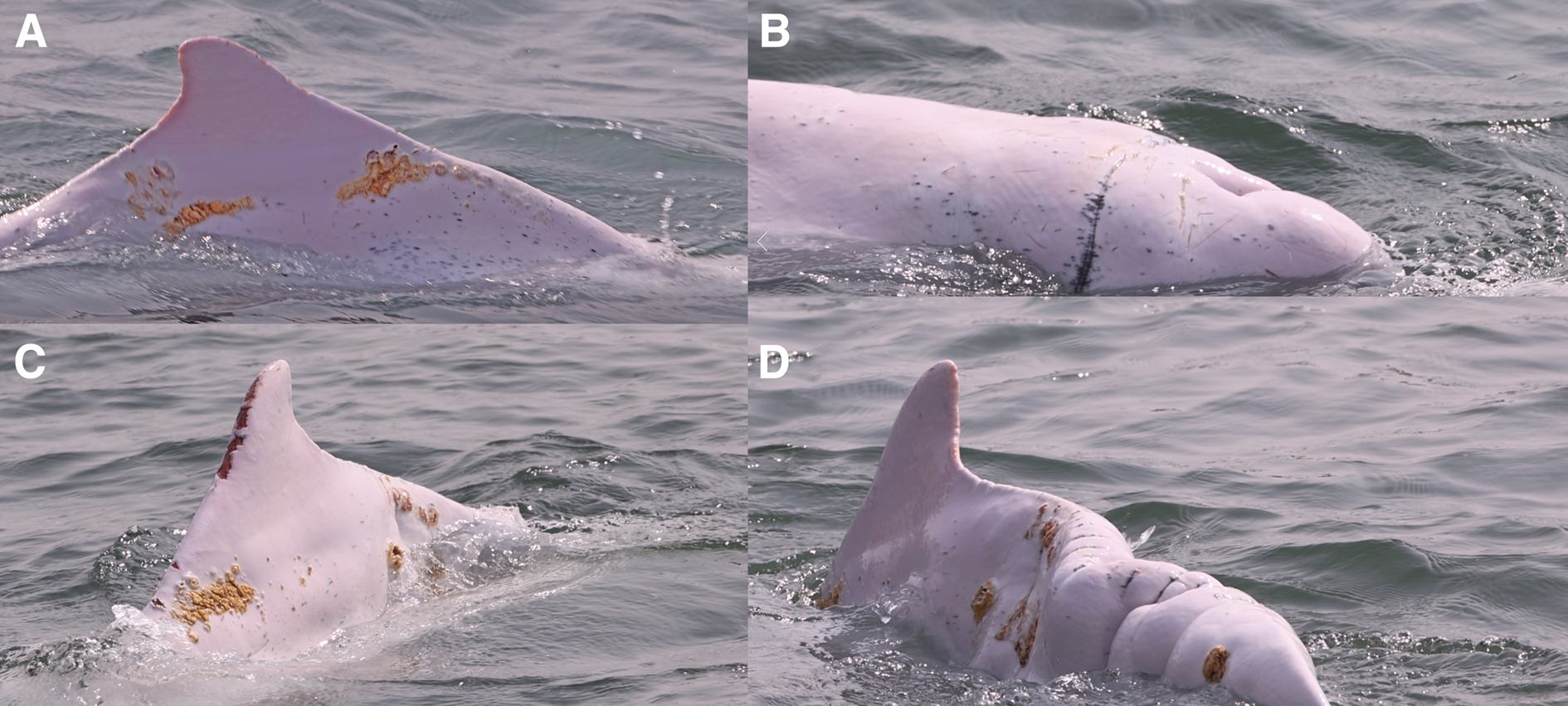

On 20 April 2021, an Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin was sighted swimming along the southern coast of Dachangshan Island off Dalian city (<10 m from the shore), Liaoning province, China (Figure 1). The individual presented a wide-based dorsal fin, white or light pink body colour with few dark spots scattered on its dorsal body region (Figure 2A). Dark spots were assembled on a vertical line behind the blowhole, forming a necklace-like dark belt (Figure 2B). These body features are typical of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in China (Jefferson, Reference Jefferson2000; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Lin, Zeng, Luo and Wu2020). The thickness of the individual's peduncle (Figure 2D) and the very low density of dark pigmentation indicate that the individual is aged (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Lin, Zeng, Luo and Wu2020).

Fig. 1. Locations of (A) currently known populations (yellow areas) and historic by-catch records in the temperate region since the 1980s (blue stars) of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in Chinese waters, and (B) historic by-catch (blue star) and recent live sightings (red stars) of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in the north of the Yellow Sea, which was found (C) travelling slowly along the coast of Dachangshan Island (photo courtesy of Mr Gang Yu). The warm and cool currents in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea are emphasized by red and blue arrows, respectively.

Fig. 2. External characteristics of the live Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin sighted in waters off Dachangshan Island, Liaoning province, China (photo courtesy of Mr Zhongmin Zhang).

The flank of the individual, with muscles/bones apparent, and the neck area that exhibited a concave curvature (Figure 2B) indicate a poor body/nutrient condition (Pugliares et al., Reference Pugliares, Bogomolni, Touhey, Herzig, Harry and Moore2007). Moreover, multiple irregular orange lesions were observed on the dorsal fin, flanks and peduncle (Figure 2A, C & D), with the latter ones looking ulcerative. In the behavioural perspective, the animal swam along the sea embankment within a distance <10 m from the shore and showed no reaction to the crowd taking photos of it. Its surfacing behaviour, although regular, was slow and lethargic.

Two apparent old traumas were also observed on this individual. First, a healed scar (~3 mm in width and depth with reference to the size of the blow hole), probably due to multifilament net entanglement, was found in its cervical region (Figure 2B). Second, the dolphin exhibited an obviously deformed peduncle (S shape peduncle and additional bumps and cavities, Figure 2D), a condition that has rarely been reported in cetaceans (Bertulli et al., Reference Bertulli, Galatius, Kinze, Rasmussen, Deaville, Jepson, Vedder, Sánchez Contreras, Sabin and Watson2015; Weir & Wang, Reference Weir and Wang2016). These two old injuries, although potentially affecting the individual's fitness to some extent, probably were not the cause of the observed emaciation (Eissa & Abu-Seida, Reference Eissa and Abu-Seida2015).

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin was guided to the offshore region by the local fishery enforcement but was re-sighted in a small river branch in Zhuanghe city on 23 April, with a linear distance ~70.1 km from its first sighting (Figure 1B).

Discussion

The ulcerative skin lesions and behaviour of the individual resembled those reported for emaciated humpback dolphins after a long period of starvation (Chan & Karczmarski, Reference Chan and Karczmarski2019). Malnutrition might cause disorientation of an animal or force it to leave its natural home range intentionally to avoid conspecific competition (Crespo-Picazo et al., Reference Crespo-Picazo, Rubio-Guerri, Jiménez, Aznar, Marco-Cabedo, Melero, Sánchez-Vizcaíno, Gozalbes and García-Párraga2021). However, the sighting of this individual may not indicate the presence of a local dolphin population, since this area is highly populated, and the presence of a resident dolphin population, if any, would have been noticed and reported in the past decades (Wang & Han, Reference Wang and Han1996; Han et al., Reference Han, Ma, Dong and Wang2004). Alternatively, two hypotheses can be made, that the animal could either be a migrant individual coming from a known population from the South China Sea or the East China Sea or be a member of an undescribed population located in the Yellow Sea, with completely different ecological meanings regarding the dispersing biology of the animal.

Distant travelling has rarely been reported in humpback dolphins of the genus Sousa, including S. chinensis in south China and S. sahulensis in north-western Australia (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Bejder, Cagnazzi, Parra and Allen2012). However, the ranging pattern of an animal results from both its dispersing ability and willingness, with the latter being largely determined by environmental features (e.g. the availability of prey, presence/absence of predator). In certain circumstances, dolphins may travel a relatively long distance to search for feeding opportunities, which was observed for Indian Ocean humpback dolphins found along the East African coast where a large estuarine or river system is absent (Karczmarski, Reference Karczmarski1999).

Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in China exhibit strong site fidelity and high residency. In the past three decades, the intense photo-identification survey efforts in the Lingding Bay (Porter, Reference Porter1998; Jefferson, Reference Jefferson2000; Chan & Karczmarski, Reference Chan and Karczmarski2017; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Lin, Zeng, Luo and Wu2020) has brought detailed information about the dispersing biology of the species. For instance, the individual home range was estimated to be 99.5 km2 for the Lingding Bay humpback dolphins (Hung & Jefferson, Reference Hung and Jefferson2004). If assuming a radial distribution, this estimate can be translated into a linear dispersing distance of only a few dozen kilometres, which were further supported by the field observation of multiple independent studies (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hung Samuel, Qiu, Jia and Jefferson Thomas2010; Chan, Reference Chan2019; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Lin, Zeng, Luo and Wu2020). However, unusual sightings were recorded in the North River in Qingyuan city, the East River in Huizhou city of Guangdong province and in the West River in Wuzhou city of Guangxi province on 29 March 2016, 12 November 2020 and 13 March 2021, respectively. These three individuals were identified as members of the population from Lingding Bay (based on a coordinated photo-identification database managed by Leszek Karczmarski and Wenzhi Lin), and the analysis suggested that animals travelled a minimum of 224.3, 191.9 and 368.0 km, respectively, if considering the shortest travelling routes from the centres of their home ranges and assuming that they were travelling along the main branch of the Pearl River system (Figure 3). A dispersing distance of 368 km is the longest record ever documented for an Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin in China and across the species range (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xu, Jefferson, Olson, Qin, Zhang, He and Yang2016; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wu, Chang, Hou, Chou and Zhu2016; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Lin, Karczmarski, Lin, Chan, Liu, Xue, Wu, Zhang and Li2021). Since travelling in the riverine system is expected to be more directional than travelling in the sea, we consider this distance to be the upper limit of the dispersal distance of the species.

Fig. 3. The longest travelling records of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins documented in the Pearl River water system. The Pearl River system is composed of three independent rivers, including the East River, the North River and the West River. The green and red dots represent the centres of the individuals' home range and the last sighting locations of each individual. The travelling routes (blue lines) were reconstructed by assuming the dolphins travelled along the main branches of the river system. The date of carcass recoveries and the distance of the putative travelling routes are indicated next to the stranding position.

The presented sighting occurred ~3000 km away from the closest known population in Ningde waters that was proposed as the northern-most distribution of the species (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zheng, Wang, Xu and Yang2012). This distance is substantially higher than the assumed species' dispersing ability mentioned above. In addition, we failed to match this individual to the existing photo-identification catalogues of populations from the Xiamen Bay, Lingding Bay, Leizhou Peninsula, Sanniang Cove and west Hainan populations (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wu, Chang, Hou, Chou and Zhu2016; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Lin, Karczmarski, Lin, Chan, Liu, Xue, Wu, Zhang and Li2021). Therefore, this individual was unlikely a migrant from one of the currently known populations from the south China waters (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zheng, Liu, Chen, Lin, Liu, Liu and Li2022). On the other hand, the presently reported sighting was very close (<50 km) to the location of the by-catch reported in 2003 (Figure 1B, Han et al., Reference Han, Ma, Dong and Wang2004). Re-occurrence of the same species, although 18 years apart, allows us to question the incidental stray hypothesis proposed by Han et al. (Reference Han, Ma, Dong and Wang2004).

The second hypothesis is that a previously undescribed population exists in the Yellow Sea. Temperature seems to be one of the key factors determining the habitat selection strategy of humpback dolphins (genus Sousa). For instance, humpback dolphins present relatively higher latitudinal distributions along the east coasts of Australia and Africa, which are subject to warm waters associated with the East Australian Current and Agulhas Current, than along the west coasts of these continents, which are heavily impacted by the cool West Australian and Benguela Currents (Parra et al., Reference Parra, Corkeron and Marsk2004; Jefferson & Curry, Reference Jefferson and Curry2015). Along the Asian coast, the East China Sea and the east Yellow Sea are both subject to the warm Kuroshio Current, resulting in a suitable niche for humpback dolphins that could therefore be found beyond the currently assumed species distribution range limited on the southern East China Sea.

If the hypothesis of a previously undescribed population is true, the status of this population and its location are still unclear. Following estimations of dispersing distance for other Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins, we suggest that the two individuals (2021 live sighting and 2003 by-catch) may come from a same population located in the northern Yellow Sea, probably less than a few hundred kilometres away from the live sighting. The Yalu River mouth (~183 km away from the first sighting presented here), which is the least disturbed area of the region as it is located on the administrative boundary between China and P.R. Korea (Figure 1B), seems to represent a suitable niche for the species.

Conclusions

We reported the first live sighting of an Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin in the Yellow Sea. In regard to the information gathered on these animals' dispersing distance, we suggest that this individual may not come from one of the known populations of the East China Sea or the South China Sea, but from a previously undescribed population in the Yellow Sea. The putative population may be one of the relict populations of species surviving the Last Glacial period (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zhou, Porter, Chen and Wu2010), which were generally very small in their population sizes (as the one in the Ningde waters which is <20 individuals) and highly susceptible to human development (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Karczmarski, Xia, Zhang, Yu and Wu2016, Reference Lin, Zheng, Liu, Chen, Lin, Liu, Liu and Li2022). An area, the Yalu River mouth, which is the largest river mouth and most likely the least disturbed area of the region, could be the most suitable niche of the species. Conducting field study in the Yalu River estuary may be difficult because of the political aspect of the area. Alternatively, a strong effort is recommended to collect fishermen's local ecological knowledge on dolphin occurrence in this region. If further confirmed, the information provided here is critical in understanding the habitat selection strategy of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin and the phylogeography of the species in the East Asian region.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Zhongmin Zhang and Gang Yu for providing the images and relative information of the sighting record used in the present study. We also thank Dr Xianyan Wang for providing the photo-identification catalogue of the Xiamen Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to this study.

Financial support

This study was funded by Alashan Society of Entrepreneurs and Ecology (SEE), Ocean Park Conservation Foundation Hong Kong (MM01.1920), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. 2018A030313870), and the ‘One Belt and One Road' Science and Technology Cooperation Special Program of the International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant number 183446KYSB20200016).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.