Introduction

Black scorpionfish (Scorpaena porcus Linnaeus, 1758) (Osteichthyes: Scorpaenidae) is widely distributed in the Eastern Atlantic, from the southern British Isles to Morocco, including the Azores, Canary Islands, Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea (de Sola et al., Reference de Sola, Herrera, Keskin, de Morais, Smith-Vaniz, Carpenter and de Bruyne2015). It is a commercially and ecologically important species and has been regarded as a delicacy in some areas due to its rough and white meat (Ferri et al., Reference Ferri, Stagličić and Matić-Skoko2012; Çulha et al., Reference Çulha, Yabanlı, Baki and Yozukmaz2016). The total Turkish landings of S. porcus from the Black Sea, Sea of Marmara and the Aegean Sea, Mediterranean Sea were 201.9, 143.2 and 138.6 tonnes in 2014, 2015 and 2016, respectively (TÜİK, 2016, 2017). Reported landings in 2017 increased to 306 t (TÜİK, 2018).

Several studies have been carried out on S. porcus in recent years, including age, reproductive biology and dietary composition in the Mediterranean Sea (Bradai & Bouain, Reference Bradai and Bouain1988, Reference Bradai and Bouain1991; Rafrafi-Nouira et al., Reference Rafrafi-Nouira, El Kamel-Moutalibi, Boumaïza, Reynaud and Capapé2016), Adriatic Sea (Pallaoro & Jardas, Reference Pallaoro and Jardas1991; Jardas & Pallaoro, Reference Jardas and Pallaoro1992), Tyrrhenian Sea (Arculeo et al., Reference Arculeo, Froglia and Riggio1993) and Black Sea (Bilgin & Çelik, Reference Bilgin and Çelik2009; Roşca & Arteni, Reference Roşca and Arteni2010; Kuzminova et al., Reference Kuzminova, Rudneva, Salekhova, Shevchenko and Oven2011).

The age, growth and reproduction aspects of S. porcus are relatively well documented, whereas its diet composition from the Turkish Black Sea is restricted to the studies of Demirhan & Can (Reference Demirhan and Can2009) and Başçınar & Sağlam (Reference Başçınar and Sağlam2009). The former study reported Carcinus mediterraneus, Crangon crangon and crab species (unidentified) as important prey species while the latter reported red mullet (Mullus barbatus) in winter and harbour crab (Liocarcinus depurator) in summer as the main diet component of S. porcus. However, neither of these studies evaluated the full seasonality of feeding habits.

The main objective of this study was to thoroughly assess the diet composition of S. porcus in the Turkish Black Sea. The feeding habits of S. porcus were investigated during winter, spring, summer and autumn to trace any seasonal shifts in the diet. Furthermore, the impact of predator size on their diets was also noted.

Materials and methods

Sampling activities

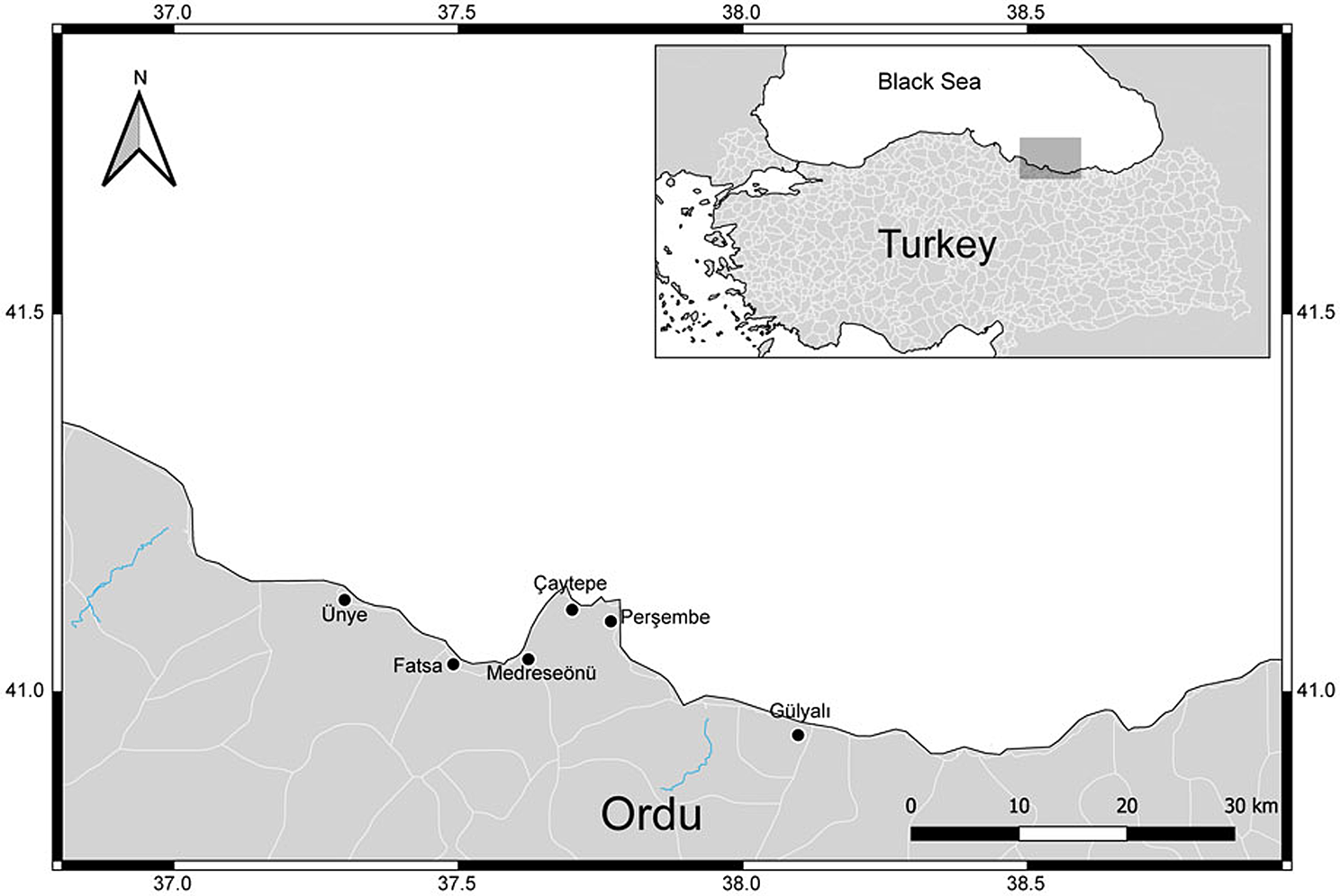

Individuals of Scorpaena porcus were collected from a coastal study area of the South-Eastern Black Sea, extending for 2.5 km between the towns of Ünye and Gülyalı (Figure 1). The samples were taken at depths of 5–40 m using trammel net (inner-panel mesh sizes of 44, 50, 56 and 60 mm). Bimonthly sampling of S. porcus was undertaken from December 2015 to November 2016 covering four seasons. Sampled specimens were transported to the laboratory in an ice box for stomach contents analysis.

Fig. 1. Map of the study area.

Laboratory analysis

Prior to dissection, each fish was weighed (to the nearest 0.1 g) and total length measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. They were categorized into three different length groups (9.0–13.9 cm, 14.0–18.9 cm and ≥19.0 cm). The stomachs were removed and their contents examined on a Petri dish. Prey items were identified to the lowest possible taxon using a stereomicroscope and then counted and weighed.

Stomach fullness and dietary analysis

Visual estimates of stomach fullness were made according to Kitsos et al. (Reference Kitsos, Tzomos, Anagnostopoulou and Koukouras2008) and were categorized as empty (0%), moderately full (25%), half full (50%), quite full (75%) and very full (100%). Furthermore, the degree of stomach fullness of S. porcus was also determined using the stomach content index (Battaglia et al., Reference Battaglia, Andaloro, Esposito, Granata, Guglielmo, Guglielmo, Musolino, Romeo and Zagami2016):

$${\rm SCI}\,\lpar \% \rpar \,= \,\displaystyle{{{\rm Wet\;weight\;of\;stomach\;content}} \over {{\rm Fish\;body\;wet\;weight}}} \times 100$$

$${\rm SCI}\,\lpar \% \rpar \,= \,\displaystyle{{{\rm Wet\;weight\;of\;stomach\;content}} \over {{\rm Fish\;body\;wet\;weight}}} \times 100$$The contribution of each prey taxon found in the stomachs of S. porcus was determined by the following dietary indices (Hyslop, Reference Hyslop1980); empty stomachs were not included in these analyses.

Frequency of percentage occurrence:

$$\% F_i = \displaystyle{{F_i} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n F_i}} \times 100$$

$$\% F_i = \displaystyle{{F_i} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n F_i}} \times 100$$Percentage numerical abundance:

$$\% N_i = \displaystyle{{N_i} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n N_i}} \times 100$$

$$\% N_i = \displaystyle{{N_i} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n N_i}} \times 100$$Percentage weight:

$$\% W_i = \displaystyle{{W_i} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n W_i}} \times 100$$

$$\% W_i = \displaystyle{{W_i} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n W_i}} \times 100$$where n is the total number of prey taxa, Fi is the number of stomachs containing prey i, Ni and Wi are the total number and wet weight (same prey species were weighed together) of prey i, respectively.

The index of relative importance (IRI) was then estimated combining %F, %N and %W into a single estimate of the relative importance of prey types (Pinkas, Reference Pinkas1971):

$${\rm IRI}\,= \,\% F\,\lpar N\% + W\% \rpar \,\Rightarrow \,\% {\rm IRI}\,= \,100 \times \;{\rm IR}{\rm I}_i\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^n {\rm IR}{\rm I}_i$$

$${\rm IRI}\,= \,\% F\,\lpar N\% + W\% \rpar \,\Rightarrow \,\% {\rm IRI}\,= \,100 \times \;{\rm IR}{\rm I}_i\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^n {\rm IR}{\rm I}_i$$The feeding strategy of S. porcus was evaluated by the modified Costello plot (Costello, Reference Costello1990; Amundsen et al., Reference Amundsen, Gabler and Staldvik1996), which is based on a 2-dimensional representation of frequency of percentage occurrence (x-axis) and prey-specific abundance (y-axis) of the different prey items found in the stomachs of a predator. The prey-specific abundance was calculated as follows:

$$\rho _i = \displaystyle{{\sum S_i} \over {\sum S_{ti}}} \times 100$$

$$\rho _i = \displaystyle{{\sum S_i} \over {\sum S_{ti}}} \times 100$$where ρi is the prey-specific abundance of prey i, Si is the stomach content (by mass in this study) of prey i, and Sti is the total stomach content in only those individuals with prey i in their stomach.

Seasonal and ontogenetic changes in feeding habits

The similarities or dissimilarities in the diet composition of S. porcus during different seasons were depicted by dendrogram. The contribution of major prey groups in the diet of S. porcus was determined through principal component analysis (PCA). The results of the PCA (only components 1 and 2) were presented as vector and sample map. Also, the diversity of prey species in the diet of different sizes of S. porcus during different seasons were displayed by a diversity profile plot. These analyses were conducted using %IRI values (log-transformed). The dendrogram was constructed using PRIMER 6 software (Clarke & Gorley, Reference Clarke and Gorley2006), PCA in R v3.4.4 (R Core Team, 2017) and a diversity profile plot by PAST v2.15 (Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001).

Results

Diet compositions

Overall species diversity and abundance

A total of 621 individuals (ranging from 9.7–32.3 cm and 12.79–765.5 g) were analysed to trace dietary information of S. porcus during winter, spring, summer and autumn. The frequency distribution showed the 13.0–13.5 cm and 15.5 cm size classes were more abundant, with fewer specimens >20 cm (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Size (TL cm) frequency distribution of specimens of black scorpion fish (Scorpaena porcus) from the SE Black Sea region of Turkey.

Only 52.8% stomachs had food, of which 40.3% stomachs were moderately full, 7.7% half full, 3.2% quite full, and only 1.6% were very full (Figure 3A). Based on SCI (%) values, the stomach fullness ranged from 3.93 ± 0.70 (mean ± SE; range = 0.10–17.47%) in winter, 3.33 ± 0.31 (0.04–13.71%) in spring, 2.38 ± 0.22 (0.04–12.38%) in summer and 3.96 ± 0.42 (0.22–18.33%) in autumn (Figure 3B). The values of SCI (%) of S. porcus were not significantly different among different seasons (one-way ANOVA; F 3,324 = 1.95; P = 0.12).

Fig. 3. Stomach fullness ratio (A) and stomach content index (B) of black scorpion fish (Scorpaena porcus) from the SE Black Sea region of Turkey. The dashed line (----) shows mean value.

A total of 29 prey species belonging to four phyla was observed in the diet of S. porcus (Table 1). Overall, the main prey taxon was Idotea balthica, which constituted 52.8%IRI of the total diet composition. This was followed by decapods (46.5%IRI) and teleosts (8.7%IRI). The most abundant species were Idotea balthica (Isopoda), Upogebia pusilla, Pilumnus hirtellus and Xantho poressa (Decapoda) and Mullus barbatus and Trachurus mediterraneus (Teleostei).

Table 1. Diet composition of black scorpion fish (Scorpaena porcus) for season and different length classes (TL cm) in SE Black Sea region, (Ordu) Turkey

Temporal variation of species diversity and abundance

The prey diversity was higher in summer in the 14.0–18.9 cm size class, followed by 16 prey types by the same size group in autumn (Figure 4). The least diversity was observed in ≥19.0 cm size class with only two prey types during spring followed by four to six prey types in the 9.0–13.9 and ≥19.0 cm groups in winter. Furthermore, the most predominant prey groups during the spring and summer were decapods (78.4–100%IRI) in all sizes, except the largest size S. porcus whose diet contained 69.6%IRI of decapods and 29.3%IRI of teleosts in the summer (Table 1). In autumn, isopods became the most predominant prey group contributing to 85.6–87.5%IRI in the diets of all sizes of S. porcus. Furthermore, in winter, the major prey group observed in the diet composition of S. porcus were teleosts. In terms of teleosts, Trachurus mediterraneus was the dominant prey species and constituted 77.4–83.8%IRI of the diets in 9.0–13.9 and 14.0–18.9 cm sizes of S. porcus. The largest size S. porcus had the largest diversity of fishes, consisting of T. mediterraneus (40.4%IRI), Mullus barbatus (29.7%IRI) and Syngnathus acus (9.4%IRI).

Fig. 4. Plot of diversity profile depicting the number of different prey items found in the stomachs of black scorpion fish (Scorpaena porcus) sampled from the SE Black Sea region of Turkey.

The population of S. porcus can be considered as a specialized predator during winter, spring and autumn where most of the prey points positioned close to the upper left corner of the modified Costello plot (Figure 5). However, a generalized feeding strategy of S. porcus was also observed in summer, where some of the prey points positioned to the lower part of the graph. In each season most of the prey points positioned to the left corner of the Costello plot reflecting that each prey category was consumed by only a limited fraction of S. porcus.

Fig. 5. Costello graph using frequency of percentage occurrence and prey-specific abundance (% mass) for black scorpion fish (Scorpaena porcus) from the SE Black Sea region of Turkey.

Similarities in diet compositions

The PCA explained 42.7 and 34.2% of the variance of the data on the first and second axis respectively. Their cumulative contribution was 76.9% indicating most of the information was represented by the two principal components. PCA clearly separated the dietary preferences of S. porcus during different seasons into three groups (Figure 6B). The spring and summer samples clustered together and separated from the autumn and winter (Figure 6A). This cluster was mainly explained by decapods, indicating this prey group as the dominant prey group in these two seasons (Figure 6A, B). The winter and autumn did not make any cluster indicating different dietary preferences of S. porcus during these seasons. Furthermore, PCA indicated teleosts in winter, and Isopoda in autumn as important prey taxa (Figure 6A, B).

Fig. 6. Principal component analysis (PCA) scores plot for different prey groups retrieved from the stomachs of black scorpion fish (Scorpaena porcus) from the SE Black Sea region of Turkey. Sample distributions (A), variable vector distributions (B).

The dendrogram showed the diets of the 9.0–13.9 and 14.0–18.9 cm sizes of S. porcus to be relatively similar for all seasons (Figure 7). The dendrogram also revealed 77% similarity in autumn, 67% in summer, 58% in winter and 54% in spring. In summer, the largest size group was separated from the other two size groups with 63% dissimilarity, while in winter, the largest group shared up to 54% similarity with the 9.0–13.9 and 14.0–18.9 groups. Overall, the largest size S. porcus had the least amount of similarity with the other groups.

Fig. 7. Dendrogram (based on %IRI values) showing the similarity in composition of diet of black scorpion fish (Scorpaena porcus) sampled from the SE Black Sea region of Turkey during different seasons.

Discussion

Diet composition and feeding strategy

Combinations of dietary analysis and modelling of gastric evacuation are important components to be included in studies designed to assess the impacts of predatory fish on their prey under different sets of environmental conditions (Hislop et al., Reference Hislop, Robb, Bell and Armstrong1991; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Seyhan, Başçinar and Başçinar2016; Andreasen et al., Reference Andreasen, Ross, Siebert, Andersen, Ronnenberg and Gilles2017; Khan & Seyhan, Reference Khan and Seyhan2019). The dietary analysis of S. porcus showed isopod and decapod crustaceans as main food items contributing to 91.3%IRI of the overall diet, whereas the contribution of teleosts to the overall diet was 8.7%IRI. In the present study, seasonal shifts in diet were observed in all sizes of S. porcus, feeding largely on isopods in autumn (>85.6%IRI), teleosts in winter (>77%IRI) and decapods (>78.4%IRI) in spring and summer. A similar trend of seasonal shifts in the diets of S. porcus along the Adriatic coast was observed by Pallaoro & Jardas (Reference Pallaoro and Jardas1991) in winter, spring and summer. Pallaoro & Jardas (Reference Pallaoro and Jardas1991) found decapods to be a predominant prey group in the stomach contents of S. porcus in autumn, contrary to the present study. Furthermore, Harmelin-Vivien et al. (Reference Harmelin-Vivien, Kaim-Malka, Ledoyer and Jacob-Abraham1989) reported teleosts from the Posidonia seagrass beds in the Marseilles area to be a major prey item of S. porcus during summer and autumn (43.9 and 39.5% of prey weight), whose proportion decreased to 13.8% during winter. These findings are in contrast to the results of the present study. Başçınar & Sağlam (Reference Başçınar and Sağlam2009) also investigated the feeding habits of S. porcus in the south-eastern Black Sea region of Turkey, but covering only two seasons: summer and winter. They found decapods in summer and teleosts in winter to be the major food of S. porcus which is in line with the findings of the present study. In their study, mud shrimp (Upogebia pusilla) was the main diet component in the summer, whereas in the present study this prey item was found during spring as the main component in the diet of the 9.0–13.9 cm size class (75%IRI) and with a relatively lower quantity (37% IRI) in S. porcus individuals ranging from 14.0–18.9 cm in size, while in summer, it appeared only in the stomach contents of the >19.0 size S. porcus as accessory prey (3.7%IRI). Contrary to the present study, Başçınar & Sağlam (Reference Başçınar and Sağlam2009) found sea horse, Hippocampus sp. as a main diet component for larger size S. porcus in winter.

The results of this study demonstrated the specialized feeding behaviour of S. porcus in the SE Black Sea which was also observed in the central and north-east Adriatic Sea by Castriota et al. (Reference Castriota, Falautano, Finoia, Consoli, Pedà, Esposito, Battaglia and Andaloro2012) and Compaire et al. (Reference Compaire, Cabrera, Gómez-Cama and Soriguer2016). However, some previous studies identified S. porcus as a generalist predator in the south and the central Tyrrhenian Sea (Arculeo et al., Reference Arculeo, Froglia and Riggio1993; Carpentieri et al., Reference Carpentieri, Colloca, Belluscio and Ardizzone2001), western Mediterranean Sea (Morte et al., Reference Morte, Redon and Sanz-Brau2001), south-eastern Black Sea region of Turkey (Demirhan & Can, Reference Demirhan and Can2009) and Romanian Black Sea (Roşca & Arteni, Reference Roşca and Arteni2010). In the present study, a transition from specialist to generalist feeding strategy in summer was exhibited by only a limited fraction of S. porcus population.

In conclusion, the present study confirmed the specialist feeding strategy of S. porcus which has been reported previously by Castriota et al. (Reference Castriota, Falautano, Finoia, Consoli, Pedà, Esposito, Battaglia and Andaloro2012) and Compaire et al. (Reference Compaire, Cabrera, Gómez-Cama and Soriguer2016). A limited fraction of S. porcus also exhibited a shift to a generalistic feeding strategy during summer, which is an important finding. The results of this study can help evaluate the dietary overlap and food partitioning among Scorpaena porcus and other predatory fish such as Scorpaena notata and Scorpaena scrofa found in the Black Sea.

Financial support

This study was supported by Ordu University Research Fund Project No. AR-1655.