Introduction

The natural characteristics of sandy beaches attract large numbers of people, subjecting them to increasing anthropogenic exploitation and disturbance (Hardiman & Burgin, Reference Hardiman and Burgin2010; Afghan et al., Reference Afghan, Cerrano, Luzi, Calcinai, Puce, Pulido Mantas, Roveta and Di Camillo2020). Tourism is considered a significant form of human impact on sandy beaches worldwide (Davenport & Davenport, Reference Davenport and Davenport2006; Thompson & Schlacher, Reference Thompson and Schlacher2008; Schlacher et al., Reference Schlacher, Richardson and McLean2008a, Reference Schlacher, Thompson and Walker2008b, Reference Schlacher, Schoeman, Dugan, Lastra, Jones, Scapini and Mclachlan2008c) and involves a wide range of activities (McLachlan & Defeo, Reference McLachlan and Defeo2017a). This intensive beach use has been recognized to negatively affect the natural physical characteristics of the beaches through compaction, rutting and disturbance to the sand matrix, (Anders & Leatherman, Reference Anders and Leatherman1987; Priskin, Reference Priskin2003) which cause changes in beach morphology and granulometric characteristics.

These changes are particularly troublesome for the benthic community, which is controlled primarily by the physical environment, with ecosystem functioning, zonation and community structure being mainly linked to beach morphological state (see McLachlan & Defeo, Reference McLachlan and Defeo2017a). Thus, changes in physical features can alter species distribution patterns, which can result in a significant loss of biodiversity (Defeo et al., Reference Defeo, McLachlan, Schoeman, Schlacher, Dugan, Jones, Lastra and Scapini2009). Several studies have shown that sand compactness in sandy beaches can be affected by the intensity of several recreative activities, including the traffic of a high number of vehicles (van der Merwe & van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe and van der Merwe1991; Schlacher & Thompson, Reference Schlacher and Thompson2007) and human trampling (Schlacher & Thompson, Reference Schlacher and Thompson2012; Reyes-Martínez et al., Reference Reyes-Martínez, Ruíz-Delgado, Sánchez-Moyano and García-García2015; Machado et al., Reference Machado, Suciu, Costa, Tavares and Zalmon2017). Thus, sites with high compaction, reflecting firmer substrates, may be unfavourable to a wide range of benthic organisms (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a), affecting the communities directly (e.g. by removing individuals) and/or indirectly (e.g. by affecting biological interactions) (Brosnan & Crumrine, Reference Brosnan and Crumrine1994; Brown & Taylor, Reference Brown and Taylor1999).

Macrobenthic communities on sandy beaches are represented by most invertebrate phyla and play a major role in sandy beach ecosystem functioning (McLachlan & Defeo, Reference McLachlan and Defeo2017a), as they are involved in nutrient regeneration (Cisneros et al., Reference Cisneros, Smit, Laudien and Schoeman2011) and are trophic links between marine and terrestrial systems (Dugan, Reference Dugan1999; Lercari et al., Reference Lercari, Bergamino and Defeo2010). They are also a pivotal economic asset (Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Miller, Weston and Young2011) in many traditional communities, where artisanal fisheries have important socioeconomic relevance (McLachlan & Defeo, Reference McLachlan and Defeo2017a). Moreover, some taxa are considered good bioindicators of beach ecological condition due to their intrinsic relationship with the sediment, including taxonomic diversity, abundance and range of physiological tolerance to stress (Veloso et al., Reference Veloso, Neves, Lozano, Perez-Hurtado, Gago, Hortas and Garcia2008). Also, as most of the species generally occupy the sand matrix of the intertidal zone, they are subject to different types of mechanical impacts, such as trampling (Machado et al., Reference Machado, Suciu, Costa, Tavares and Zalmon2017; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Madureira and Zalmon2018) and vehicle traffic (Schlacher & Thompson, Reference Schlacher and Thompson2007, Reference Schlacher and Thompson2008; Schlacher et al., Reference Schlacher, Thompson and Price2007, Reference Schlacher, Richardson and McLean2008a, Reference Schlacher, Thompson and Walker2008b).

The effects of recreational activities on faunal communities have been evaluated in different coastal environments worldwide (Rodgers & Cox, Reference Rodgers and Cox2003; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Forster, Montserrat, Ponti, Terlizzi, Ysebaert and Middelburg2007; Ferreira & Rosso, Reference Ferreira and Rosso2009; Mendez et al., Reference Mendez, Livore, Calcagno and Bigatti2017). On sandy beaches, this issue has been tackled from different perspectives (Reyes-Martinez et al., Reference Reyes-Martínez, Ruíz-Delgado, Sánchez-Moyano and García-García2015). In general, most studies assessed the effect of these activities at the population level of some taxa of supralittoral macrofauna, such as Talitridae (Weslawski et al., Reference Weslawski, Stanek, Siewert and Beer2000; Ugolini et al., Reference Ugolini, Ungherese, Somigli, Galanti, Baroni, Borghini, Cipriani, Nebbiai, Passaponti and Focardi2008; Veloso et al., Reference Veloso, Neves, Lozano, Perez-Hurtado, Gago, Hortas and Garcia2008, Reference Veloso, Sallorenzo, Ferreira and Souza2009; Bessa et al., Reference Bessa, Scapini, Cabrini and Cardoso2017), Ocypodidae (Barros, Reference Barros2001; Neves & Bemvenuti, Reference Neves and Bemvenuti2006; Lucrezi et al., Reference Lucrezi, Schlacher and Robinson2009; Schlacher et al., Reference Schlacher, Lucrezi, Connolly, Peterson, Gilby, Maslo, Olds, Walker, Leon, Huijbers, Weston, Turra, Hyndes, Holt and Schoeman2016; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Madureira and Zalmon2018, Reference Costa, Secco, Arueira and Zalmon2020a) and Cirolanidae (Veloso et al., Reference Veloso, Neves and Almeida Capper2011). However, the effects of these activities were also assessed at the community level (Schlacher & Thompson, Reference Schlacher and Thompson2012; Reyes-Martinez et al., Reference Reyes-Martínez, Ruíz-Delgado, Sánchez-Moyano and García-García2015; Machado et al., Reference Machado, Suciu, Costa, Tavares and Zalmon2017; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zou, Zhong, Yu, Li and Wang2018; Bom & Colling, Reference Bom and Colling2020), and the results of the available studies showed a general negative effect of recreational activities on abundance, diversity and composition of the macrobenthic community.

The sandy beaches of the Brazilian Amazon coast are distributed along a 3900 km coastline (Klein & Short, Reference Klein, Short, Short and Klein2016) and have considerable potential for the tourism industry (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Vila-Concejo, Short, Short and Klein2016a, Reference Pereira, Trindade, Silva, Vila-Concejo, Short, Short and Klein2016b). Recreational activities observed on Amazonian beaches can be classified as pulse disturbances (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a) as they are strongly concentrated in short periods. In fact, some of these beaches are overcrowded during vacation periods and extended holidays (Sousa-Felix et al., Reference Sousa-Felix, Pereira, Trindade, Souza, Costa and Jimenez2017), and subject to an increasing exploration (Szlafstein, Reference Szlafstein2012), resulting in a range of anthropogenic hazards (e.g. bacteriological contamination from sewage outfalls, litter pollution) (Sousa-Felix et al., Reference Sousa-Felix, Pereira, Trindade, Souza, Costa and Jimenez2017; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Sousa-Felix, Costa and Jimenez2018). Another emerging environmental problem on many Amazonian beaches is the presence of multiple motor vehicles (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Sousa-Felix, Costa and Jimenez2018; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a). In fact, during vacation periods, multiple vehicles are driven onto some of the touristic beaches and serious problems have been recorded, including accidents and traffic jams (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Pereira, Vila-Concejo, Gorayeb, Sousa, Asp and Costa2011; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Sousa-Felix, Costa and Jimenez2018). In addition, especially during vacation periods, vehicles parking on the intertidal zone, are often trapped by the rapid rise of the tide (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Pereira, Vila-Concejo, Gorayeb, Sousa, Asp and Costa2011; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Sousa-Felix, Costa and Jimenez2018).

The Amazon region has been undergoing rapid economic and urban growth in recent decades (Becker, Reference Becker2005), and despite its singular environmental characteristics and high economic and ecological importance, anthropogenic impacts on the benthic fauna have been poorly studied (Paula et al., Reference Paula, Rosa Filho, Souza and Aviz2007; Morais et al., Reference Morais, Sarti, Chelazzi, Cincinelli, Giarrizzo and Martinelli Filho2020; Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Costa, Pinheiro, Lima, Aviz and Lima2020; Ribeiro-Brasil et al., Reference Ribeiro-Brasil, Castro, Petracco, Batista, Brasil, Ferreira, Borba, Rollnic, Fillmann and Amado2021), and studies that evaluate the effect of recreational activities on Amazonian sandy beaches are even more scarce (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a). In this context, the present study evaluated, for the first time, the impact of recreational activities on macrobenthic fauna structure and composition of three Amazonian sandy beaches with different levels of recreational activity intensity (high, intermediate and low), before, during and after a period with high tourist occupancy (July – scholar vacation). The following hypothesis was tested: high intensity of recreational activities (human trampling and vehicle traffic) causes changes in macrobenthic community structure and composition, reducing species richness and density, particularly during the vacation period in the beaches with high tourist occupancy where sediment compaction is higher.

Materials and methods

Study area

The selected beaches are located in the Atlantic coastal sector of north Brazil, one of the most densely populated areas of the Amazonian region (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Pereira, Silva, Oliveira, Pinto and Costa2011) with a total of 433,302 inhabitants (IBGE, 2020). The coastline is highly irregular and indented (Souza-Filho et al., Reference Souza-Filho, Paradella and Silveira2005), being formed by several tide-dominated estuarine and oceanic sandy beaches (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Vila-Concejo, Short, Short and Klein2016a), and includes the oceanic beaches most visited by tourists in the region (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Sousa-Felix, Dias, Pessoa and Silva2021). This coast has semidiurnal macrotides (4–6 m) with moderated wave energy (Hs <2 m during high tides) and strong tidal currents (up to 2 m s−1) (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Oliveira, Costa, Costa and Vila-Concejo2013). Local climate is equatorial humid with annual mean temperature of 26–27°C and rainfall up to 3000 mm (Martorano et al., Reference Martorano, Pereira, Cezar and Pereira1993; INMET, 2009; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Oliveira, Costa, Costa and Vila-Concejo2013). The trade winds blow from the north-east in the dry and south-east in the rainy season, respectively (Klein & Short, Reference Klein, Short, Short and Klein2016; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Vila-Concejo, Short, Short and Klein2016a).

This study was conducted in Salinópolis city on the northern Brazilian coast (0°36′49″S 47°21′22″W) (Figure 1). Salinópolis has ~40,000 residents and its economy is based on fishing and tourism, receiving >280,000 beachgoers during July vacation (IBGE, 2020). Sampling was performed on three beaches with a variable anthropogenic pressure gradient. The Atalaia beach (considered as the Urban area) has a high level of urban development (e.g. restaurants and hotels) and high human occupancy during the summer season. The backshore is partially occupied by construction and tourism infrastructure, which have destroyed the vegetation cover and dune system (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a). In contrast, Corvinas beach (considered as the Protected area) is a pristine sector with a low level of disturbance and a well-preserved dune system and mangrove vegetation in the backshore area (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Mehlig, dos Santos and Menezes2010). This beach can only be reached on foot (Martinelli Filho & Monteiro, Reference Martinelli Filho and Monteiro2019).

Fig. 1. Map showing the location of Salinópolis and the three sandy beaches studied (1: Corvinas – Protected area; 2: Farol-Velho – Intermediate area; 3: Atalaia – Urban area).

The Farol-Velho beach is an intermediate sector located in the transitional area between Atalaia and Corvinas. Farol-Velho is partially urbanized with a lower level of tourism occupancy and the backshore includes construction and low tourism infrastructure (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a). Vehicles are only allowed on Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches; however, the highest influx occurs on Atalaia beach. The beaches have similar sedimentological and morphodynamic characteristics: dissipative exposed state, gentle slope, spilling waves, and sediment comprised mainly of fine to very-fine sand (Ranieri & El-Robrini, Reference Ranieiri and El-Robrini2015, Reference Ranieiri and El-Robrini2016). The main hydrodynamic features are macrotides, strong coastal currents (up to 1.5 m s−1) and wave energy modulated by wave attenuation on sand banks during low tide (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Pereira and Oliveira2009; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Ribeiro, Monteiro and Asp2009; Klein & Short, Reference Klein, Short, Short and Klein2016).

Sampling procedures

To evaluate the effects of tourism-related activities on macrofauna, four sampling campaigns were conducted on each beach (Atalaia, Farol-Velho and Corvinas) during spring tides: June 2017 – Before Vacation; July 2017 – Vacation; August 2017 – After 1 (one month after vacation); and September 2017 – After 2 (two months after vacation). Macrofauna was sampled in the intertidal zone of each beach along two across-shore transects (100 m distant from each other). Seven equidistant sampling levels (SL) were established 50 m apart from each other at each transect, from the high tide mark to the swash zone. Four samples were collected at each sampling station with a cylindrical corer (10 cm diameter and 20 cm height). After collection, samples were sieved through a 0.3 mm mesh screen and preserved in 70% ethanol stained with rose bengal. Simultaneously, sediment samples were collected from each sampling station for granulometric and organic matter content analyses using the same corer used for biological samples. Sediment compaction was determined at each station using a manual penetrometer (data in centimetres penetrated using 20 kgf cm−2) with a modification of a method described by McLachlan & Defeo (Reference McLachlan and Defeo2017a, Reference McLachlan, Defeo, McLachlan and Defeo2017b).

Levels of surface disturbance were estimated using the number of vehicles and beachgoers observed on each beach. For this purpose, four campaigns were conducted (one per month on each beach) along with biological sampling procedures. In each campaign, vehicles and beachgoers were counted in an area between two across-shore transects (100 m × 350 m) along the intertidal zone for 10 min every 30 min within a 4 h period (a total of 8 counts/beach/sampling campaign).

Laboratory procedures

Biological samples were examined under a stereoscopic microscope, and organisms were counted and identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible. Granulometric analysis was conducted by sieving the coarse sediments and pipetting the fine sediments, as proposed by Suguio (Reference Suguio1973). Textural parameters (mean grain size, sorting, percentage of sand and gravel) were calculated using the equations of Folk & Ward (Reference Folk and Ward1957). Grain sizes were determined by sieving the sediment in an automatic shaker and classifying the grains according to the Wentworth scale (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan, Holme and McIntyre1984). Dried samples were combusted at 550°C for 4 h to determine organic content (O.M.) (Dean, Reference Dean1974).

Statistical analysis

The potential impact of recreational activities on the composition and structure of the macrofaunal community was evaluated using a modified Before/During/After/Control/Impact (BDACI) method comparing the beach that was heavily impacted by recreation with the less impacted beaches before, during and after the impact. For each biological sample, the richness (total of taxa) and density (ind. m−2) were analysed using a three-way nested ANOVA (months: ‘Before’, ‘Vacation’, ‘After 1’ and ‘After 2’; Beaches: Atalaia, Farol-Velho and Corvinas; and Sampling levels: A–G nested in beaches) after checking normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and homogeneity of variance Levene's tests. When necessary, data were fourth root transformed. When ANOVA results were significant, the Tukey's test was used for pairwise comparisons.

A non-metric multidimensional scaling ordination (nMDS) of ‘beach × month’ interaction was performed (based on Bray–Curtis similarity) to visualize differences in macrofauna structure. The contribution of each taxon to the dissimilarity (>50%) found among groups was evaluated using the SIMPER (similarity percentage) routine. Simultaneously, the similarity matrix was analysed using a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), using the same configuration as in the ANOVA. When the PERMANOVA detected a significant difference, Tukey's a posteriori test was applied to identify significant pairwise differences. A 5% significance level was considered in all analyses.

The mean number of beachgoers and vehicles obtained on each beach was used to determine the intensity of sediment disturbance caused by recreational activities in each month and the differences between beaches and months were analysed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). To detect changes in abiotic variables (grain size, sorting, % sand and % fines, % O.M., and sand compaction) a three-way nested ANOVA (months: ‘Before’, ‘Vacation’, ‘After 1’ and ‘After 2’; Beaches: Atalaia, Farol-Velho and Corvinas; and Sampling levels: A–G nested in beaches) was performed. When ANOVA results were significant, the Tukey's test was used for pairwise comparisons. Abiotic variables were also analysed using multivariate methods (Clarke & Gorley, Reference Clarke and Gorley2006). Multiple regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship between human beach use (number of beachgoers and vehicles) and sediment parameters, and the relationship of human beach use and sediment parameters with changes in macrobenthic density and richness.

Results

Environmental parameters and human beach use

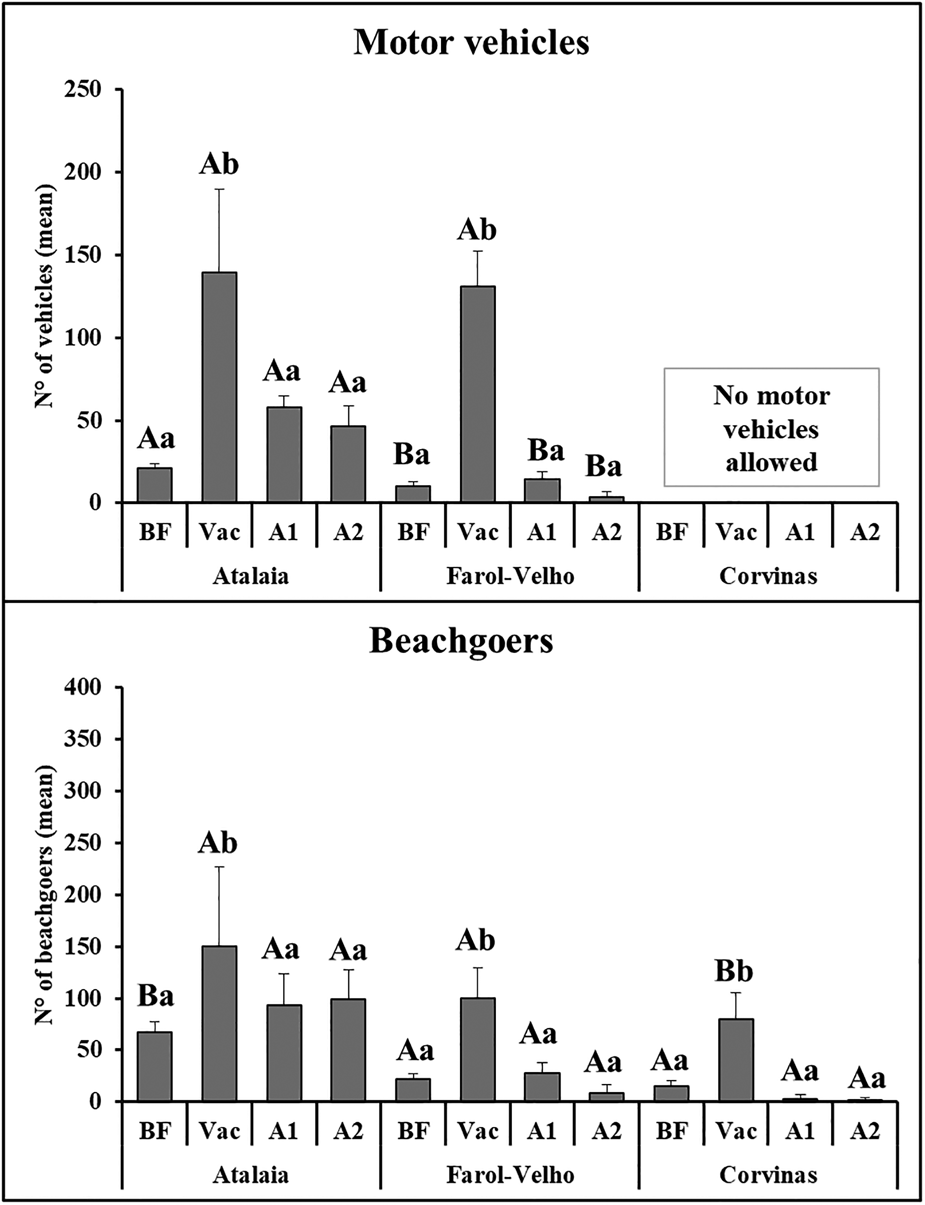

In general, the number of vehicles and beachgoers was higher during Vacation in all beaches compared with the other months (beach × month). Both Atalaia and Farol-Velho showed significant differences compared with Corvinas during Vacation (F (1.84) = 6.38; P < 0.05) with higher numbers of vehicles and beachgoers on both beaches compared with Corvinas; however, differences were not detected between Corvinas and Farol-Velho in the other months. All beaches showed the same monthly pattern, with significant differences found only between Vacation and other months (Figure 2). Data for all environmental parameters are shown in Supplementary Material 1.

Fig. 2. Number of vehicles (A) and beachgoers (B) counted (mean ± SE) in each area in the different study periods (BF, Before vacation; Vac, during Vacation; A1, After vacation 1; and A2, After vacation 2). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05); uppercase letters (A≠B) indicate differences between beaches among months and lowercase letters (a ≠ b) indicate differences between months on each beach.

Overall, the studied beaches were characterized by well-sorted fine to very-fine sand (Supplementary Material 1) with fine sand representing more than 65% of sediment composition in all beaches (Figure 3A). Sediment characteristics (mean grain size, sorting and O.M.) did not differ among the beaches over the months (Table 1). However, some differences were found in sediment sorting and O.M. between months and beaches, with higher values of sorting found in Atalaia during vacation whereas higher values of O.M. were found in Corvinas beach (Supplementary Material 1). Overall, higher sand compactness was found during vacation (Figure 3B) but it differed significantly only from the values obtained in before vacation (Table 1). Atalaia beach sand was always more compacted than sand in the other beaches (Figure 3B). The multiple regression analysis showed negative correlation between recreational activities (number of beachgoers and vehicles) and sediment characteristics; however, only sediment compaction had significant correlations (Table 2).

Fig. 3. Granulometric composition (%) of the sediments (A) and sediment compaction (B) in each area in the different study periods (Before, Vacation, After 1 and 2). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05); uppercase letters (A ≠ B) indicate differences between beaches among months and lowercase letters (a ≠ b) indicate differences between months on each beach.

Table 1. ANOVA analysis results highlighting significance differences in the environmental parameters of the study areas

*P < 0.05; ** P < 0.001.

Table 2. Multiple regression results showing the correlations and levels of significance for each significant predictor environmental variable used for modelling sandy beach community attributes

**P < 0.05; β – standardized coefficients.

Macrobenthic community

A total of 46 taxa were recorded (Table 3). Annelida (mainly Polychaeta) was the most diverse phylum (18 species), followed by Crustacea (16 species) and Mollusca (five species). Relative abundances of the major taxa in each beach in different months are shown in Figure 4. Before vacation, polychaeta and Bivalvia were dominant in all beaches except for Corvinas beach, where Bivalvia had lower abundance. During the vacation month, polychaetes dominated in all beaches, followed by bivalves and crustaceans in the Atalaia and insects in the Farol-Velho beach. After vacation, the abundance of crustaceans and insects increased in the Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches. Concerning the Corvinas beach, the relative abundances of the major taxa were constant over time.

Fig. 4. Relative abundance (%) of macrobenthic community in the study beaches in the different sampling months (Before vacation, Vacation, After vacation 1 and 2).

Table 3. ANOVA analysis and pairwise test regarding the significance of differences in descriptors of macrofaunal community of the study beaches

Mean densities significantly varied among treatments (Table 4) with differences mostly between Vacation and the other months (Before Vacation and After 1 and 2) in the Atalaia and Farol-Velho. Overall, higher density values occurred at Corvinas beach in all months. Regarding months, a marked decrease in density occurred in the Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches during Vacation, when the lowest densities were recorded. In the After-vacation months (1 and 2), density increased in all beaches and the values were similar to those found before vacation (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. Mean density (ind. m−2 ± SE) (A) and richness (±SE) (B) of macrobenthic community in the study beaches in the different sampling months (Before vacation, during Vacation, After vacation 1 and 2). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05); uppercase letters (A≠B) indicate differences between beaches among months and lowercase letters (a ≠ b) indicate differences between months on each beach.

Table 4. Mean density (ind. m−² ± SE) of the benthic macrofauna at the study area

B, Before; V, Vacation; A1, After 1; A2, After 2.

Richness also presented significant differences among treatments (Table 4). Overall, a similar macrofaunal composition was found among beaches, although higher richness was found in Corvinas beach in all months and lower richness was found during Vacation in Atalaia beach. Regarding months, a marked decrease in richness occurred in the Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches. In the After-vacation months (1 and 2), richness increased in all beaches and the values were similar to the values found before vacation (Figure 5B).

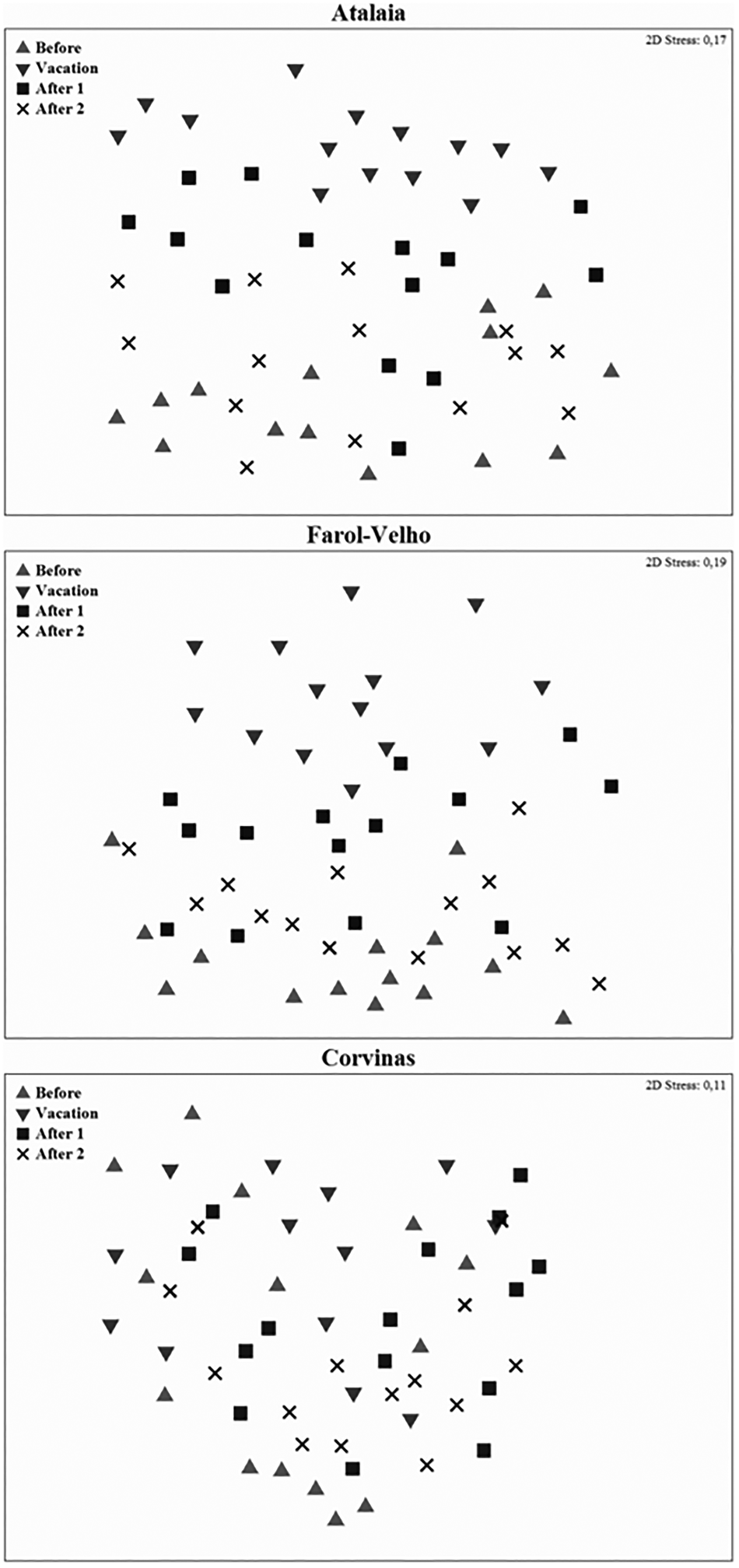

The PERMANOVA analysis showed significant differences in the macrobenthic community structure among months and beaches (Table 5). The pairwise comparisons indicated that these differences occurred especially between Before Vacation and Vacation in Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches (Table 5). The nMDS ordination showed that samples grouped according to month. It is possible to identify in nMDS plots that Atalaia and Farol-Velho, and the Corvinas were different over time (Figure 6). In Atalaia and Farol-Velho, it is possible to identify a group of samples from Before Vacation and After 2 months, and a second group of samples from Vacation and After 1 months.

Fig. 6. nMDS for month × beach combinations for macrobenthic community in the study beaches.

Table 5. Results of PERMANOVA analysis and pairwise test regarding macrobenthic community structures of the study beaches

The SIMPER test showed a high level of dissimilarity in the communities among all months in all beaches (Table 6). Overall, most taxa were more abundant in the Before and After vacation. Concerning beaches, higher dissimilarities occurred mostly during vacation in Atalaia and Farol-Velho, due to low abundance of the polychaetes Thoracophellia papillata, Scolelepis squamata and Paraonis sp. The multiple regression analysis showed that macrobenthic density and richness had significant negative correlations with sediment compaction and human beach use (beachgoers and vehicles) (Table 7).

Table 6. Multiple regression results showing correlations and levels of significance of each significant predictor environmental variable used for modelling sandy beach community attributes

*P < 0.05; β – standardized coefficients.

Table 7. The results of the SIMPER analysis, showing the mean abundances (ind. m−2 ± SE) and similarity of the species that most contributed to the samples between study beaches and months

Discussion

Macrofaunal density and richness showed different patterns among the studied months. The Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches followed the same temporal pattern. This pattern was characterized by a sharp reduction in density and richness with significant change in community structure before and during the disturbance period (vacation month), followed by an increase of the community descriptors (density and richness) in the After-vacation months. Conversely, on Corvinas beach the macrobenthic communities were very stable, with no significant temporal changes in structure even during the Vacation month. Consequently, we consider that touristic use, in the form of beachgoers and vehicle traffic is the major source of variability that affected macrofaunal community in our study. This observation is supported by the negative correlation between the number of beach users and community structure descriptors in the study areas. In addition, the pattern found here is similar to the results found in studies evaluating the effect of vehicle traffic and human trampling on macrofauna of sandy beaches worldwide (Wolcott & Wolcott, Reference Wolcott and Wolcott1984; Veloso et al., Reference Veloso, Silva, Caetano and Cardoso2006; Schlacher & Thompson, Reference Schlacher and Thompson2012; Fanini et al., Reference Fanini, Zampicinini and Pafilis2014; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zou, Zhong, Yu, Li and Wang2018; Bom & Colling, Reference Bom and Colling2020; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Zalmon, Fanini and Defeo2020b).

With exception for the sediment compaction, the other environmental parameters described here (e.g. sediment size, sorting and O.M.) did not markedly differ among beaches and remained constant over the months. In fact, higher sediment compaction values were found in the Vacation month (July) in all studied beaches, especially at Atalaia and Farol-Velho where most of the beachgoers and vehicles were found. In several Amazon beaches the number of beachgoers increases dramatically during the school vacation month (July) (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Sousa-Felix, Costa and Jimenez2018), and consequently also increases the number of motor vehicles (e.g. cars, buses, motorcycles, off-road vehicles and trucks) on the beaches.

Considering our results and lack of significant differences at Corvinas beach even during the vacation month, we can attribute faunal differences to the distribution of physical impacts caused by recreational activities. The severity of these impacts was mainly dependent on the compactness of the sand since the lowest faunal densities were found at high compaction values (>20 kgf cm−2): Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches during Vacation. It is known that recreational activity has a negative effect on several beach organisms, once these activities may increase the sediment compaction (Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Forster, Montserrat, Ponti, Terlizzi, Ysebaert and Middelburg2007; Ugolini et al., Reference Ugolini, Ungherese, Somigli, Galanti, Baroni, Borghini, Cipriani, Nebbiai, Passaponti and Focardi2008; Schlacher et al., Reference Schlacher, Richardson and McLean2008a, Reference Schlacher, Thompson and Walker2008b, Reference Schlacher, Schoeman, Dugan, Lastra, Jones, Scapini and Mclachlan2008c, Reference Thompson and Schlacher2014; McLachlan & Defeo, Reference McLachlan and Defeo2017a). Also, invertebrates can be killed through direct crushing by a high presence of vehicle traffic and human trampling (Wolcott & Wolcott, Reference Wolcott and Wolcott1984; van der Merwe & van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe and van der Merwe1991; Schlacher et al., Reference Schlacher, Richardson and McLean2008a, Reference Schlacher, Thompson and Walker2008b, Reference Schlacher, Schoeman, Dugan, Lastra, Jones, Scapini and Mclachlan2008c; Bom & Colling, Reference Bom and Colling2020). Therefore, the lower density found at Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches might be linked to sediment compaction in these areas, a consequence of the high number of vehicles and beachgoers present during vacation.

The macrobenthic community composition in the studied beaches was similar and comprised 46 taxa with a dominance of Polychaeta. In fact, the studied beaches were expected to have similar compositions, as they are located close to each other and have similar morphodynamic characteristics and granulometry (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a). However, only Corvinas beach had all taxa occurring throughout the study period. Beaches with fewer recreational activities in general are more complex, organized, mature and active environments than urbanized beaches (Reyes-Martínez et al., Reference Reyes-Martínez, Lercari, Ruíz-Delgado, Sanchez-Moyano, Jimenez-Rodríguez, Perez-Hurtado and García-García2014). In our study all macrobenthic taxa were affected by the recreational activities, however, their responses varied according to beach and month and these differences were found mainly in Atalaia and Farol-Velho, where sharp decreases in the richness occurred. In fact, recreational activities in Amazonian beaches are likely to have higher impacts during the vacation periods in the benthic fauna, as shown by a previous study (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a). In that study Santos et al. (Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a) showed that the meiofauna community is sensitive to recreational activities, and these impacts may be related to changes in substrate characteristics, especially to compaction.

The macrobenthic fauna of the present study was dominated by polychaetes. The dominance of polychaetes is a general pattern in intertidal habitats of the Amazonian coast (Rosa Filho et al., Reference Rosa Filho, Busman, Viana, Gregório and Oliveira2006, Reference Rosa Filho, Almeida and Aviz2009, Reference Rosa Filho, Gomes, Almeida and Silva2011; Beasley et al., Reference Beasley, Fernandes, Figueira, Sampaio, Melo, Barros, Saint-Paul and Schineider2010; Braga et al., Reference Braga, Monteiro, Rosa-Filho and Beasley2011, Reference Braga, Silva, Rosa-Filho and Beasley2013; Morais & Lee, Reference Morais and Lee2013; Santos & Aviz, Reference Santos and Aviz2018, Reference Santos and Aviz2020, Reference Santos and Aviz2021; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Rabelo, Beasley and Braga2020, Reference Santos, Almeida, Aviz and Rosa Filho2021b, Reference Santos, Almeida, Aviz and Rosa Filho2021). Thus, the impact of recreational activities in this study was mainly evidenced by changes in density and taxonomic composition of Polychaeta assemblages. In fact, the use of Polychaeta as indicators of human impact has intensified, due to their significant presence, both in quantitative and qualitative terms, when compared with other benthic fauna organisms (Amaral et al., Reference Amaral, Morgado and Salvador1998, Feres et al., Reference Feres, Santos and Tagori-Martins2008).

In the present study, a sharp reduction in polychaete densities was observed in the beaches with high compaction (>20 kgf cm−2) during vacation. It has been shown that recreational activity has a negative effect on beach communities probably due to sediment compaction, which might hamper burrowing and thus reduce the probability of survival of organisms (Ugolini et al., Reference Ugolini, Ungherese, Somigli, Galanti, Baroni, Borghini, Cipriani, Nebbiai, Passaponti and Focardi2008). Therefore, sites with high compaction, reflecting firmer substrates, may be unfavourable to a wide range of small-sized burrowers and sessile and semi-sessile infaunal polychaetes, because compaction increases the energy costs of burrowing (Brown & Trueman, Reference Brown and Trueman1991; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Chen and Hsieh2009; Che & Dorgan, Reference Che and Dorgan2010; Dorgan, Reference Dorgan2015). Considering this fact, the presence of a high abundance of polychaetes might be indicative of less-compacted sediments.

Some polychaete species, such as Thoracophelia papillata, Scolelepis squamata and Paraonis sp., seem to be rather sensitive to high values of sediment compaction caused by recreational activities, as indicated by their relatively higher abundance at Corvinas beach compared with the other beaches. Furthermore, they also had changes in density throughout the study months, reflecting changes in impact intensity. T. papillata, S. squamata and Paraonis sp. are probably more vulnerable to trampling and vehicle traffic because they are shallow burrowers and have no hard structures such as shells and carapaces as protection against physical disturbance (MacCord & Amaral, Reference MacCord and Amaral2005). The decline in these taxa was more evident at Atalaia and Farol-Velho beaches, where their densities were minimal or even absent. Similar results were found in the highly urbanized sectors of sandy beaches of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) by Machado et al. (Reference Machado, Suciu, Costa, Tavares and Zalmon2017), who observed that the impact occurred especially on soft-bodied organisms, such as Nemertea and the polychaete Hemipodia californiensis (Hartman, 1938), a species that is usually abundant in that region. Also, similar to the results obtained for Thoracophelia furcifera (Ehlers, 1897) on two urbanized beaches of the south coast of Brazil (Vieira et al., Reference Vieira, Borzone, Lorenzi and Carvalho2012), the low density of T. papillata found in our study suggests that this species does not tolerate great intensity of trampling and vehicle traffic, even if these only occur during a restricted period of the year in the Amazon region.

Recreational activities observed on Amazonian beaches can be classified as pulse disturbances (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a), however, pulse disturbances can produce either a pulse or a press response in the community (Glasby & Underwood, Reference Glasby and Underwood1996; Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Márquez, Marzinelli, Mendez and Bigatti2015). Recreational activities on Amazonian sandy beaches caused a discrete pulse disturbance affecting the macrobenthic community during the Vacation month, but the communities returned to density and richness values similar to their initial condition (before period) in the second month after the Vacation (i.e., After 2 period). A similar pattern was found in a previous study in the same Amazonian beaches where the meiofauna community density and richness values returned to similar conditions soon after the Vacation ended (within a month) (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Petracco and Venekey2021a). Thus, although the macrobenthic fauna showed high susceptibility to recreational activities, they also showed high resilience. However, the consequence of intensive use by beach visitors in urbanized areas could result in a long-term loss of biodiversity which might become irreversible (Reyes-Martínez et al., Reference Reyes-Martínez, Ruíz-Delgado, Sánchez-Moyano and García-García2015).

Conclusions

The results reported in this pioneer study evaluating the effect of recreational activities in macrobenthic community of Amazonian macrotidal sandy beaches showed a similar pattern to those found in previous studies on other sandy beaches worldwide. Thus, the hypothesis that recreational activities trigger changes in benthic macrofaunal structure and composition, reducing species diversity, richness and abundance in the community was confirmed. Furthermore, the vulnerability of some taxa studied here, particularly the polychaetes T. papillata, S. squamata and Paraonis sp., indicates that they may be potential indicators of recreational activity impacts, and can be used as tools to investigate impacts associated with recreational activities (trampling and vehicle traffic).

The beaches studied here along the Amazonian coast are attractive recreational sites that are intensively visited every vacation period and holidays. This study shows that on these beaches, recreational activities may have adverse effects on intertidal benthic assemblages. Long-term studies are required to determine the status of communities under the influence of tourism disturbances. This study also highlights the importance of establishing and implementing effective management actions to mitigate the consequences of recreational activities on sandy beaches. Management plans and conservation strategies should include: (1) the development of protected areas with restricted access and use; (2) control of number of visitors and their decentralization (Machado et al., Reference Machado, Suciu, Costa, Tavares and Zalmon2017). The above-mentioned actions, together with the prohibition of vehicles in the intertidal zone, should be implemented on Amazonian sandy beaches.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315422000480.

Data

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brazil (CAPES) –Finance Code 001. The first author is grateful for the CAPES postgraduate research studentship (Brazil). The authors are grateful to Adrielle Lopes, Afonso Quaresma, Ana Paula Danin, Diego Garcia, Felipe Souza, Gabriel Soares, Keuli Campelo, Leonardo Morais, Mary Aguiar and Roseanne Figueira for their assistance in the field.

Authors' contributions

Santos T.M.T: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Petracco M: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Venekey V: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.