Introduction

Coastal zones are transitional areas located between the continent and the ocean, which encompass high levels of biodiversity and include some of the most productive and vulnerable ecosystems on Earth (Yunis, Reference Yunis2001). These zones are also among the marine environments most accessible to humans (Amaral et al., Reference Amaral, Corte, Rosa Filho, Denadai, Colling, Borzone, Veloso, Omena, Zalmon, Rocha-Barreira, Souza, Rosa and Almeida2016), and given these characteristics, they sustain the economies of many urban centres and communities around the world (de Ruyck et al., Reference de Ruyck, Soares and Mclachlan1995; Orams, Reference Orams2003; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Osleeb and Viola2004). Coastal population growth exerts strong pressure on biotic and abiotic resources, which demands a constant assessment of the health of the environment, and careful management (Crain et al., Reference Crain, Halpern, Beck and Kappel2009).

A range of artificial structures are constructed in coastal regions with a variety of functions, including coastal protection (Dugan et al., Reference Dugan, Airoldi and Chapman2011; Nordstrom, Reference Nordstrom2014), the generation of renewable energy (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hutchison, Macleod, Burrows, Cook, Last and Wilson2013), recreational activities (Connell & Glasby, Reference Connell and Glasby1999; Connell, Reference Connell2000), aquaculture (Giles, Reference Giles2008; McKindsey et al., Reference McKindsey, Archambault, Callier and Olivier2011) and the extraction of natural resources (Kingston, Reference Kingston1992; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Kennicutt II, Green, Montagna, Donald, Harper, Powell and Roscigno1996; Wilson & Heath, Reference Wilson and Heath2001). These structures provide substrates for colonization by both native and alien species and can affect a diversity of the coastal biota at a regional level (Airoldi et al., Reference Airoldi, Abbiati, Beck, Hawkins, Jonsson, Martin, Moschella, Sundelöf, Thompson and Åberg2005). Fixed structures can also modify local hydrodynamic patterns, such as the wave field and currents, leading to scouring or increasing sedimentation, and changes in sand ripple patterns and the grain size of the sediment of soft-bottom habitats (Davis et al., Reference Davis, VanBlaricom and Dayton1982; Wilding, Reference Wilding2006; Al-Bouraee, Reference Al-Bouraee2013). These changes can influence the species composition, abundance, biotic interactions and trophic structure of the benthic invertebrate assemblages, in particular the infauna (Davis et al., Reference Davis, VanBlaricom and Dayton1982; Caine, Reference Caine1987; Kneib, Reference Kneib1991; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Bertasi, Colangelo, de Vries, Frost, Hawkins, Macpherson, Moschella, Satta, Thompson and Ceccherelli2005; Firth et al., Reference Firth, Grant, Crowe, Ellis, Wiler, Convery and O'Connor2017; Heery et al., Reference Heery, Bishop, Critchley, Bugnot, Airoldi, Mayer-Pinto, Sheehan, Coleman, Loke, Johnston, Komyakova, Morris, Strain, Naylor and Dafforn2017).

Artisanal fisheries are typically local fleets that use mechanical or manual fishing techniques (Berkes et al., Reference Berkes, Mahon, McConney, Pollnac and Pomeroy2001). These operations are run by the vast majority of the world's fishers and provide over half the world's wild-caught seafood (Berkes et al., Reference Berkes, Mahon, McConney, Pollnac and Pomeroy2001; Chuenpagdee et al., Reference Chuenpagdee, Liguori, Palomares and Pauly2006). Artisanal fisheries are widespread throughout the world (Munro, Reference Munro1974). On the Brazilian coast, these fisheries employ an enormous variety of techniques and equipment, with the fish weir being one of the most popular strategies used. These weirs (Figure 1B) are fixed traps for the capture of fish, which are typically constructed of lines of stakes driven into the substrate to form a fence-like structure aligned with the direction of the local tidal currents (Piorsk et al., Reference Piorsk, Serpa and Nunes2009). Weirs are particularly common on the Brazilian coast, where tidal amplitudes exceed 2 m (Mai et al., Reference Mai, Silva, Legat and Loebmann2012), and in northern Brazil (the Amazon region), weirs account for almost half of fishery productivity in coastal and inland waters (Paiva, Reference Paiva1997).

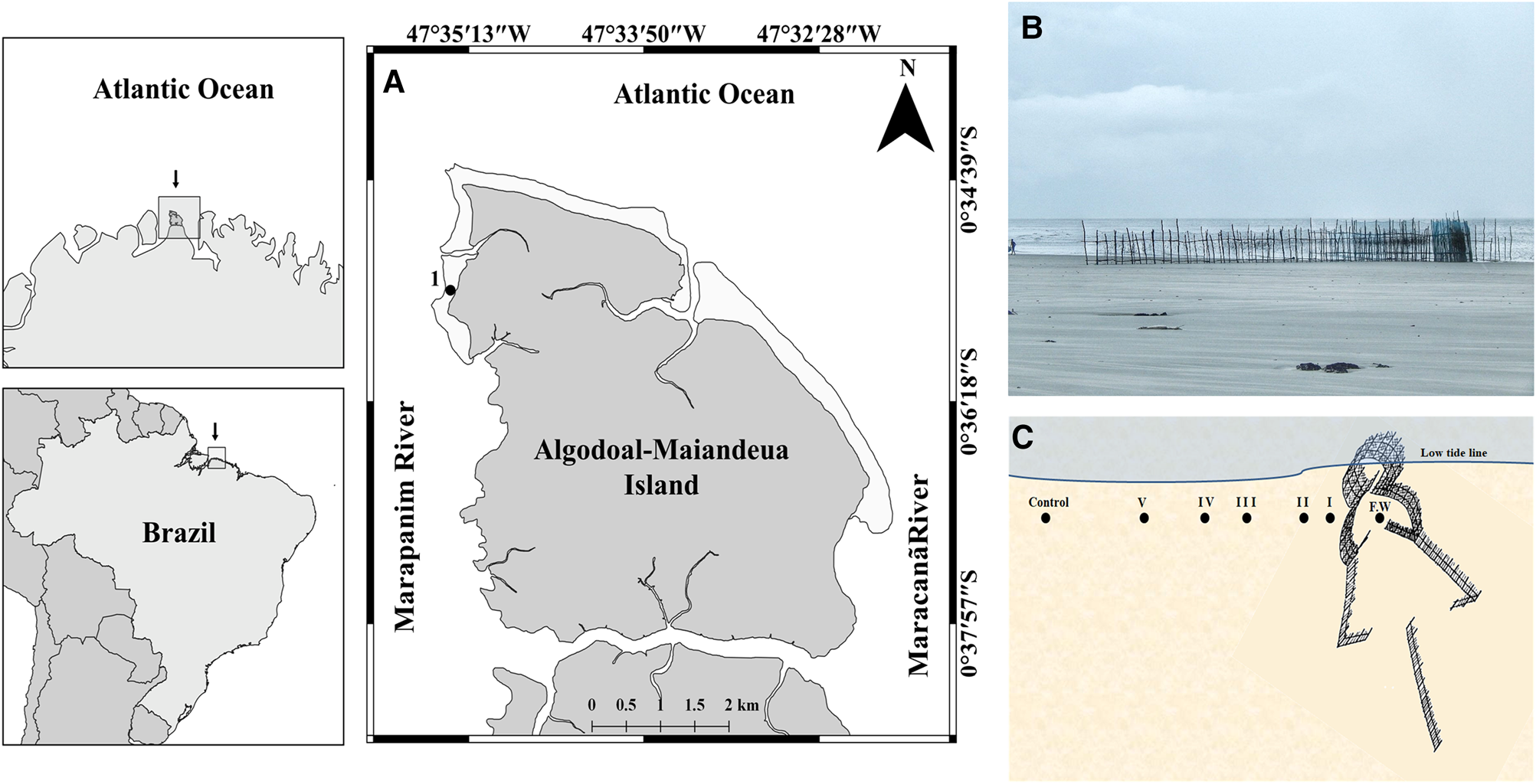

Fig. 1. Map of Algodoal-Maiandeua Island showing the study area (A); the fish weir (B) and the sampling layout (C): F.W = Inside the fish weir; I = 10 cm from the weir; II = 50 cm; III = 1 m; IV = 2 m; V = 5 m; and Control area = 50 m from the weir.

While a number of studies have focused on the influence of large man-made structures on the macrobenthic fauna (see Heery et al., Reference Heery, Bishop, Critchley, Bugnot, Airoldi, Mayer-Pinto, Sheehan, Coleman, Loke, Johnston, Komyakova, Morris, Strain, Naylor and Dafforn2017 for a review), little attention has been paid to the impact of the structures installed by artisanal fisheries on habitats and benthic community structure (Pranovi et al., Reference Pranovi, Raicevich, Franceschini, Torricelli and Giovanardi2001; Gaspar et al., Reference Gaspar, Leitão, Santos, Chícharo, Dias and Monteiro2003; Lokrantz et al., Reference Lokrantz, Nyström, Norström, Folke and Cinner2009; Batista et al., Reference Batista, Fabre, Malhado and Ladle2014). In Brazil, only David et al. (Reference David, Silva, Nascimento and Maia2015) has evaluated the influence of fish weirs on the soft habitats of a sandy beach. That study was conducted in north-eastern Brazil, and compared the macrofauna in the weir with that from external areas, up to a distance of 10 m. Although no significant spatial variation was found in the faunal richness or abundance, the composition of the mollusc assemblage did shift between the areas.

The present study describes the influence of a fish weir on the macrobenthic fauna of a macrotidal sandy beach on the Amazon coast. The following hypotheses were tested: (i) the presence of the fish weir contributes to the establishment of a distinct macrobenthic assemblage in comparison with that of the surrounding sediments; and (ii) the structure of the benthic macrofauna varies according to the distance (on a scale of centimetres to metres) from the fish weir.

Materials and methods

Study area

The island of Algodoal-Maiandeua is located on the northern coast of Brazil (0°34′45″–0°37′30″S 47°32′05″–47°34′12″W) and is surrounded on three sides by rivers and estuarine channels (Figure 1A). The region is dominated by semi-diurnal macrotides, with an amplitude of 4–7 m (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Pereira, Gorayeb, Vila-Concejo, Sousa, Asp and Costa2011). The local climate is humid tropical, with a mean annual temperature of 27.7 ± 1.1°C (Martorano et al., Reference Martorano, Pereira, César and Pereira1993) and mean annual precipitation (30-year records) of 2200–2800 mm (Moraes et al., Reference Moraes, Costa, Costa and Costa2005). Precipitation varies considerably over the course of the year, however, with a well-defined rainy season from January to July (total rainfall ~1700 mm), and a dry season from August to December, with total rainfall of ~500 mm (Moraes et al., Reference Moraes, Costa, Costa and Costa2005).

Algodoal-Maiandeua Island has 35 km of sandy beaches, which have sandy and sand-muddy substrates, and vary considerably in their slope, extension, width and their exposure to wave action (Mendes, Reference Mendes and Fernandes2005). The study beach, Caixa d’Água, is located on the western margin of the island, which is bathed by the Marapanim River and is a low-tide terrace sheltered beach with a wide intertidal zone (400–500 m) composed mainly of fine sand (Rosa-Filho et al., Reference Rosa-Filho, Gomes, Almeida and Silva2011). Fishing weirs are abundant in the intertidal zone of this beach.

Sampling and processing

Samples were collected in August 2017 (dry season) from within the central portion of a fish weir of ~20 m in length located in the low intertidal zone of the Caixa d’água beach (Figure 1B) and from five points located at increasing distances from the external part of the weir, i.e. 10 cm, 50 cm, 1 m, 2 m, 5 m and 50 m, which was used as the control point (Figure 1C). Five samples were collected at each point using cylindrical cores (0.0079 m2, 20 cm deep). The samples were washed through a 0.3 mm mesh screen, and the material retained in this filter was fixed in 4% formalin saline. Simultaneously to the biological sampling, three sediment samples were collected from each point using the same core sampler for granulometric analyses. The temperature of the sediment was determined from three random replicates taken with a soil thermometer at each sampling point.

In the laboratory, the biological samples were examined under a stereoscopic microscope, and the organisms observed were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level and counted. The granulometric analysis was conducted by sieving out the coarse sediments and pipetting the fine sediments, as proposed by Suguio (Reference Suguio1973). The textural parameters (mean grain size, sorting, sand and percentage gravel) were calculated using the equations of Folk & Ward (Reference Folk and Ward1957). Grain sizes were determined by sieving the sediment in an automatic shaker and classifying the grains on the Wentworth scale (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan, Holme and McIntyre1984). Water content was estimated as water loss after drying the sediment for 24 h at 60°C. The dried samples were combusted at 550°C for 4 h to determine their organic content (Dean, Reference Dean1974).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the richness (total number of taxa) and density (ind. m−2) of each biological sample. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov procedure was applied to test the assumption of normality, and the Levene test, to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. Whenever necessary, the data were log (x + 1) transformed for analysis. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the faunal and sediment descriptors among the points located at different distances from the fish weir (weir, 10 cm, 50 cm, 1 m, 2 m, 5 m, control). When the ANOVA detected significant variation, Tukey's a posteriori test was applied to identify the significant pairwise differences.

The environmental data, once log (x + 1) transformed and normalized, were analysed using a principal components analysis (PCA) based on Euclidian distance. A principal coordinates analysis (PCoA), run on a Bray–Curtis similarity matrix of the fourth root-transformed species mean abundance data, was used to assess the effects of the fish weir on the macrofauna and validate our distance grouping hypothesis. To identify the most common species at each distance, species that correlated (Spearman's coefficient) more than 60% with one of the first two axes were plotted in each PCoA. A similarity matrix (from fourth root-transformed species abundance data) was analysed using a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), using the same configuration as the ANOVA. The P-values were corrected through Monte Carlo random draws from the asymptotic permutation distribution, due to the possible permutations number not being large (Anderson & Robinson, Reference Anderson and Robinson2003). The contribution of each taxon to the similarity and dissimilarity found among the groups was assessed using the SIMPER (similarity percentage) routine. A 5% level was considered significant in all analyses.

Results

Environmental parameters

A list of the environmental parameters and the results of ANOVAs are given in Table 1. Overall, sediment temperatures increase from the fish weir to the control area, with significantly higher values at 5 m and 50 m (control) from the trap. By contrast, the organic matter and water content of the substrate decreased with increasing distance from the weir, and the percentage of organic matter was significantly higher in the weir in comparison with all other sites.

Table 1. Environmental characteristics (mean density ± SE) of the study area

Sil, silt; VFS, very fine sand; FS, fine sand; MS, moderate sorted.

Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Tukey's tests; P < 0.05). Textural classification based on Wentworth scale.

In general, the sediments in and near (10 and 50 cm) the fish weir were finer grained (Table 1). The substrate in and adjacent (10 cm) to the weir was made up of coarse silt moderately sorted sediments, whereas all other points (50 cm, 1 m, 2 m, 5 m, control) had very fine sand moderately sorted sediments. The mean grain size did not vary significantly among points, although the percentage of fine grains was significantly higher in the weir and at 10 cm, while the percentage of sand was higher at 5 m and in the control area.

Based on these environmental parameters, the first two principal components (PC) explained 78% of the variation among the sites (Figure 2). On axis 1, which explained 59.3% of the variation in the data, the samples from the fish weir are clearly separated from the external samples. In and near the weir (at distances of up to 50 cm), the sediments had a higher water and organic matter content and were muddier. By contrast, the sites furthest from the weir had sediments with larger grain sizes (more sand) and higher temperatures. Axis 2, which explained only 18.7% of the variation in the data, was more closely associated with sorting and organic matter content. The samples from the weir had the highest values of organic matter and the lowest for sorting.

Fig. 2. Results of the principal component analysis (PCA) of the environmental data collected at different distances from the fish weir.

Macrofauna community

Twenty-eight macrobenthic taxa were recorded during the present study, of which the polychaetes Mediomastus californiensis (Hartman, 1944) and Capitella capitata (Fabricius, 1780) and the molluscs Leukoma pectorina (Lamarck, 1818), Hiatella arctica (Linnaeus, 1767) and Austromacoma costricta (Brugière, 1792) were found exclusively in the fish weir and at the adjacent (10 cm) sampling point, whereas the polychaete Glycera sp. was found exclusively in the control area (Table 2). The Annelida was the phylum represented by the largest number of taxa (16), and it was the most abundant group at all sites (Figure 3A). The polychaete Magelona sp. (23.46% of the total abundance) was the most abundant taxon in the study area, but it was found only inside the weir and next to it (10 and 50 cm). Arthropods were absent in the internal site and increased in density from the 10 cm site to the control area. Molluscs were recorded at higher densities in and next to (10 cm) the weir (Figure 3A). Although deposit feeders were numerically dominant at practically all points, their abundance declined with increasing distance from the weir (Figure 3B). By contrast, predators were more abundant at the points further from the weir (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. Relative abundance (%) of taxonomic (A), feeding groups (B), mean density (ind. m−2 ± SD) (C) and taxon richness (D) of the macrobenthic fauna for each distance from the fish weir. Different letters indicate significant differences between sites (Tukey's tests; P < 0.05).

Table 2. Mean density (ind. m−2 ± SE) of the benthic macrofauna of the fish weir and the distances with their trophic group

Taxa: P, Polychaeta; B, Bivalvia; C, Crustacea. Feeding mode: Dep: deposit feeder (ingests sediment or ingests particular matter only); Sus, suspension/filter feeder (strains particles from the water); Pre, Predator (eats live animals); On, omnivorous.

The mean macrobenthos densities (df = 6; F (1.27) = 3.09; P = 0.01) and total number of taxa (df = 6; F (1.27) = 2.46; P = 0.04) varied significantly among sites. In both cases, the highest mean values (3012.7 ± 424.4 ind. m−2; 11 taxa) were recorded in the fish weir and at a distance of 10 cm (2177.2 ± 224.3 ind. m−2; 14 taxa), while the lowest means were recorded at the 1 m (632.9 ± 169.3 ind. m−2; 7 taxa) point (Figure 3C). The principal pairwise differences (Tukey's test) were recorded between the weir and adjacent points (10 and 50 cm) and the 1 m point (Figure 3D). Density and richness tended to decrease between the weir and 1 m, with values increasing at greater distances.

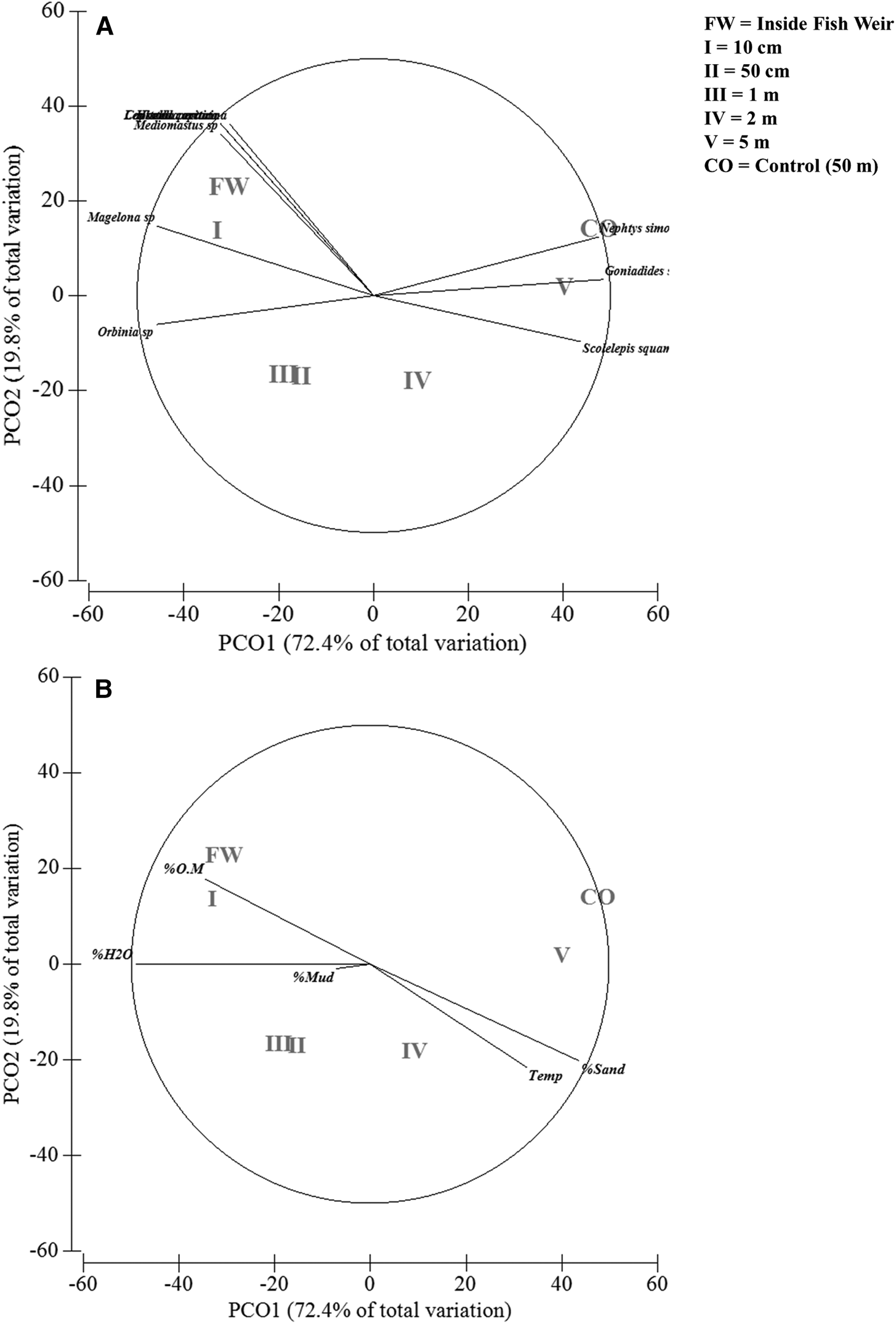

The PCoA plot distinguished the macrofauna samples at the different distances from the fish weir (Figure 4). Axis 1 explained 72.4% of the variation in the data and was responsible for separating the distances. On the negative side of this axis, the best-correlated taxa were more abundant from the weir to 50 cm. These taxa included the polychaetes Capitela capitata, Mediomastus californiensis, Orbinia sp. and Magelona sp., the molluscs Hiatella arctica and Leukoma pectorina, and the Nemertea. These species were associated with the highest proportions of organic matter and the finer sediments. On the positive side of axis 1, in turn, the polychaetes Nephtys simoni (Perkins, 1980), Scolelepis squamata (Müller, 1806) and Goniadides sp. were most closely associated with the control area and the distances of 2 and 5 m from the weir (Figure 4A). The percentage of sand and high sediment temperatures were the environmental variables most closely associated with these species (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4. Results of the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the samples of the macrobenthic fauna collected at different distances from the fish weir. The vectors represent species that correlate by more than 50% (based on the Spearman correlation coefficient) with one of the first two PCoA axes.

The PERMANOVA confirmed the spatial configuration of the PCO, with significant differences among the sites (Pseudo-F = 4.2749; P (perm) = 0.001; P (Monte Carlo) = 0.001). The faunistic structure of the fish weir was similar to that found at the adjacent point (10 cm), and these two points were distinct from all the others (Supplementary Material 1). Community structure was also similar between the distances of 50 cm and 1–2 m from the weir, while the control site was different from all other points, except for that located at 5 m from the weir (Supplementary Material 1).

The SIMPER analysis indicated that dissimilarity increased with increasing distance from the weir to the control point (Supplementary Material 2), and most of the species highlighted by the SIMPER were those that correlated most closely with the PCoA axes. Most of the species indicated by the SIMPER were more abundant in the weir.

Discussion

The installation of artificial structures, such as breakwaters and sea walls, on sedimentary shorelines is known to alter hydrodynamic conditions, sediment transport, bottom profiles, the production of detritus (Heery et al., Reference Heery, Bishop, Critchley, Bugnot, Airoldi, Mayer-Pinto, Sheehan, Coleman, Loke, Johnston, Komyakova, Morris, Strain, Naylor and Dafforn2017), and sediment granulometry and chemistry (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Bertasi, Colangelo, de Vries, Frost, Hawkins, Macpherson, Moschella, Satta, Thompson and Ceccherelli2005; Bertasi et al., Reference Bertasi, Colangelo, Abbiati and Ceccherelli2007; Munari et al., Reference Munari, Corbau, Simeoni and Mistri2011; Morley et al., Reference Morley, Toft and Hanson2012; Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Raymond, McBride, Toft, Cordell, Ogston, Heerhartz and Berry2016). These structures may also affect the structure of local biotic communities, due to modifications to the flux of spatial resources (Dugan et al., Reference Dugan, Hubbard, Rodil, Revell and Schroeter2008; Heerhartz et al., Reference Heerhartz, Dethier, Toft, Cordell and Ogston2014), the availability of surfaces for attachment, ecological connectivity (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Mayer-Pinto, Airoldi, Firth, Morris, Loke, Hawkins, Naylor, Coleman, Chee and Dafforn2017), foraging behaviour (Munsch et al., Reference Munsch, Cordell, Toft and Morgan2014) and a range of other ecological processes (reviewed by Heery et al., Reference Heery, Bishop, Critchley, Bugnot, Airoldi, Mayer-Pinto, Sheehan, Coleman, Loke, Johnston, Komyakova, Morris, Strain, Naylor and Dafforn2017).

On Algodoal-Maiandeua Island, fish weirs are a common feature of the low intertidal zone of the local beaches. Our results indicate that these weirs alter associated sedimentary habitats, primarily by increasing the amount of fine-grained sediment and organic matter. This is probably related to the protection of the substrate from the action of waves and currents. Any type of man-made structure installed on the seabed will interact immediately with the local hydrodynamics, and may modify the current regime, accelerate or baffle the flow of water around the structure, contribute to the establishment of various types of vortices and turbulence, and alter wave breaking patterns (Al-Bouraee, Reference Al-Bouraee2013; Wilding, Reference Wilding2014). These modifications of flow patterns may result in considerable changes in the granulometric characteristics of the associated sediments. While increased scouring and a reduction in fine material around the structure, such as artificial reefs, have been reported in some cases (Davis et al., Reference Davis, VanBlaricom and Dayton1982; Barros et al., Reference Barros, Underwood and Lindegarth2001), in general, the reduction in flow caused by the structure results in an increase in fine sediments and organic matter in the vicinity of the structure (Fricke et al., Reference Fricke, Koop and Cliff1986; Danovaro et al., Reference Danovaro, Gambi, Danovaro, Gambi, Mazzola and Mirto2002; Zanuttigh et al., Reference Zanuttigh, Martinelli, Lamberti, Moschella, Hawkins, Marzetti and Ceccherelli2005; Wilding, Reference Wilding2006; Al-Bouraee, Reference Al-Bouraee2013; Heery et al., Reference Heery, Bishop, Critchley, Bugnot, Airoldi, Mayer-Pinto, Sheehan, Coleman, Loke, Johnston, Komyakova, Morris, Strain, Naylor and Dafforn2017).

The results of the present study indicated significant variation in the features of the sediment among sampling points at scales of a few centimetres to several metres. At the centimetre scale, the same predominance of finer sediments (silt and clay) was found inside the weir and at a distance of 50 cm. However, the gradual decrease in fine grains, water content and organic matter indicates that the effects on the sediment persist up to at least 1–2 m from the weir. The sediment in the study area was typical of the intertidal zone of Caixa d’Água beach (i.e. 83–98% sand, with a mean grain size of 1.1–3.3 mm diameter; Rosa-Filho et al., Reference Rosa-Filho, Gomes, Almeida and Silva2011) at distances of more than 2 m from the weir. Man-made structures and hydrodynamic changes are known to impact sedimentary patterns on moderate (several metres) and small (centimetres to metres) spatial scales (see Heery et al., Reference Heery, Bishop, Critchley, Bugnot, Airoldi, Mayer-Pinto, Sheehan, Coleman, Loke, Johnston, Komyakova, Morris, Strain, Naylor and Dafforn2017 for a review).

The macrobenthic fauna in the present study area was dominated by polychaete worms and the typically marine and estuarine taxa found on Caixa d’Água beach and other intertidal habitats of the Amazon coast (Rosa-Filho et al., Reference Rosa-Filho, Busman, Viana, Gregório and Oliveira2006, Reference Rosa-Filho, Almeida and Aviz2009; Beasley et al., Reference Beasley, Fernandes, Figueira, Sampaio, Melo, Barros, Saint-Paul and Schneider2010; Braga et al., Reference Braga, Monteiro, Rosa-Filho and Beasley2011; Reference Braga, Silva, Rosa-Filho and Beasley2013; Rosa-Filho et al., Reference Rosa-Filho, Gomes, Almeida and Silva2011; Morais & Lee, Reference Morais and Lee2013; Santos & Aviz, Reference Santos and Aviz2018). The presence of fish weirs on the beach nevertheless permits the establishment of a more diverse and abundant macrobenthic community. The assemblages from the weir and adjacent points (up to 50 cm distant) were composed of species found primarily in muddy environments (e.g. mudflats, mangroves and saltmarsh), such as the polychaetes Magelona sp., Mediomastus sp. and Capitella capitata, and the molluscs Macoma sp. and Leukoma pectorina (Beasley et al., Reference Beasley, Fernandes, Figueira, Sampaio, Melo, Barros, Saint-Paul and Schneider2010). Conversely, the fauna at distances of 1 m or more from the weir was composed mainly of species found typically on sandy Amazonian beaches, such as the polychaetes Nephtys simoni, Scolelepis squamata and Goniadides sp., and the amphipod Phoxocephalidae sp. (Rosa-Filho et al., Reference Rosa-Filho, Almeida and Aviz2009, Reference Rosa-Filho, Gomes, Almeida and Silva2011).

The distribution of trophic groups in the study area can also be explained by the proximity of the fish weir and the variation in sediment texture. Fine, organically rich muds tend to contain more burrowing deposit feeders, whereas coarser sediments typically harbour more mobile animals, predators and suspension feeders (Pearson & Rosenberg, Reference Pearson and Rosenberg1978). A similar pattern was found in the present study, where the deposit feeders were more abundant in and adjacent to the weir, while predators increased toward the control area. The higher infaunal density in the weir was related principally to the greater abundance of the polychaete Magelona sp., which was present only up to 50 cm from the structure. The magelonids are surface deposit feeders, which are common in the muddy sand substrates of intertidal zones and continental shelves (Hartman, Reference Hartman1971; Fauchald & Jumars, Reference Fauchald and Jumars1979).

The structure of the infaunal assemblage also varied significantly with increasing distance from the study weir. Taxon richness and density were both higher in the weir and decreased to a distance of 1 m before increasing again toward the control area. Species composition varied significantly and consistently from the points adjacent to the weir to those furthest away. The granulometry and organic content of the sediment are known to influence benthic communities (Snelgrove & Butman, Reference Snelgrove and Butman1994) and have been highlighted in many studies as the probable mechanism through which artificial structures alter the composition of soft-sediment benthic communities (Ambrose & Anderson, Reference Ambrose and Anderson1990; Barros et al., Reference Barros, Underwood and Lindegarth2001). In general, finer sediments are associated with greater organic content and macrobenthic diversity, abundance and biomass, but this may change if the organic load is excessive and reduces the availability of oxygen (Wilding, Reference Wilding2014).

The reduction of quantitative descriptors of macrofauna with increasing distance from the weir may be related to the biological interactions linked to food availability. The decrease of the organic matter content should result in greater competition between surface deposit feeders. Furthermore, the increasing presence of predators at the sites further from the fish weir may also have contributed to the decrease in the infauna. Infaunal predators have been shown to have a significant negative effect on infaunal densities and species diversity, as well as affecting the spatial and temporal distribution of their prey (Posey & Hines, Reference Posey and Hines1991). The principal predator species in the study area was the polychaete N. simoni, which prefers fine to medium sand (Lana, Reference Lana1986; Rosa-Filho et al., Reference Rosa-Filho, Gomes, Almeida and Silva2011), and gradually increased in density at greater distances from the fish weir. Several Nephtys species are known for their role as predators of benthic macrofauna, and will reduce abundance of their prey, which are primarily other infaunal polychaetes (Schubert & Reise, Reference Schubert and Reise1986; Benvenuti, Reference Benvenuti1994; Arndt-Sullivan & Schiedek, Reference Arndt-Sullivan and Schiedek1997).

In the present study, the lowest taxon richness and density were recorded at the point located 1 m from the fish weir, which appears to represent a transitional environment in relation to the influence of this structure on the sediment and the associated macrobenthic community. At this point, the sediment shifted from predominantly muddy to sandy and the infaunal community was formed by taxa present at all other sampling points, including Orbinia sp., N. simoni and Laeonereis culveri (Webster, 1879), as well as species typical of muddier sites, such as Sigambra grubii (Müller, 1858), Paraonis sp. and Lumbrinereis sp. Negative responses of the infauna in contact zones between substrate types are well known to occur in subtidal and intertidal bottoms in the vicinity of natural structures (Cusson & Bourget, Reference Cusson and Bourget1997; Barros et al., Reference Barros, Underwood and Lindegarth2001; Gusmao-Junior & Lana, Reference Gusmao-Junior and Lana2015), as well as man-made structures, such as bulkheads and sea walls (Spalding & Jackson, Reference Spalding and Jackson2001) and artificial reefs (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Fleeger and Carney1993; Barros et al., Reference Barros, Underwood and Archambault2004). The negative response to the proximity of harder substrates is generally attributed to the interaction between organisms, such as predation and competition (Dahlgren et al., Reference Dahlgren, Posey and Hulbert1999; Langlois et al., Reference Langlois, Anderson and Babcock2005; Galván et al., Reference Galván, Parma and Iribarne2008), or to variations in sediment texture (Ambrose & Anderson, Reference Ambrose and Anderson1990; Gusmao-Junior & Lana, Reference Gusmao-Junior and Lana2015). Transitional environments are also often described as being more variable and unstable than neighbouring ecological systems (Farina, Reference Farina and Farina2010).

Despite its limitations, the results of the present study supported the hypothesis that the presence of fish weirs modifies significantly the characteristics of the associated macrobenthic infauna. This conclusion would obviously be reinforced by a broader sample, which would include a larger number of weirs and sites, as well as different configurations of weirs. The findings of this study indicate that the weir exerts an influence on a micro-scale, ranging from a few centimetres to 1–2 metres. While these findings provide important preliminary insights, a more systematic understanding of the effects of these man-made structures on hydrodynamic patterns, substrate characteristics and the structure of faunal assemblages will require a much broader research approach.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315419001231.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Gabriel Souza for his assistance in the field and Fábia Nascimento and João Antônio Veloso for their help with the processing of the samples. We would also like to thank Stephen Ferrari for the language revision of the manuscript. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which helped us to improve the manuscript.

Financial support

No funding was received specifically for the project presented here.