Introduction

Edwardsiidae is one of the most speciose families within order Actiniaria (Williams, Reference Williams1981; Fautin et al., Reference Fautin, Zelenchuck and Raveendran2007; Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008; Fautin, Reference Fautin2013) including nine genera and ~75 species of burrowing sea anemones. Despite the broad distribution of its representatives, occurring from polar to tropical zones in all depths, including hypersaline environments (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Perissinotto, Laird, Dyer and Todaro2012) and Antarctic ice (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Rack and Zook2013; Sanamyan et al., Reference Sanamyan, Sanamyan and Schories2015), the number of edwardsiids recorded for the South Atlantic remains small and probably does not represent the true diversity of the group in the region. Only three species of Edwardsiidae have been recorded in South Atlantic waters: Edwardsia sanctaehelenae Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1941 in Santa Helena island (Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1941); Nematostella vectensis Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935, in the port area of Recife, in north-east Brazil (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Lima, Perez and Gomes2010); and Edwardsia migottoi Gusmão, Brandão & Daly, Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016 in south-east Brazil (Gusmão et al., Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016). Two other species, Scolanthus intermedius (McMurrich, Reference McMurrich1893) and Edwardsia inachi Sanamyan, Sanamyan & Schories, Reference Sanamyan, Sanamyan and Schories2015 occur in the Atlantic portion of the Southern Ocean, in the King George Island (Carlgren, Reference Carlgren and Odhner1927; Sanamyan et al., Reference Sanamyan, Sanamyan and Schories2015).

The low number of species of Edwardsiidae in Brazil is possibly the result of a historical small number of sea anemone specialists in the region and anatomical characteristics of the group (i.e. small size and burrowing habits) that make them hard to collect and identify. In addition, the external morphology of edwardsiids resembles that of other animal phyla, such as Priapulida and Sipuncula, often leading to misidentifications by non-experts. Thus, most species of sea anemones recorded to Brazil correspond to large individuals inhabiting hard-bottom environments, such as coral reefs and intertidal pools in rocky shores (Corrêa, Reference Corrêa1964; Dube, Reference Dube1974; Pires et al., Reference Pires, Castro, Migotto and Marques1992; Gomes & Mayal, Reference Gomes and Mayal1997; Zamponi et al., Reference Zamponi, Belém, Schlenz and Acuña1998), leaving the diversity of Actiniaria of soft-bottoms under-studied. Although the presence of edwardsiids in Brazil is known since at least 1967 (Tommasi, Reference Tommasi1967), most reports have not included proper descriptions (e.g. Capitoli & Bemvenuti, Reference Capıtoli and Bemvenuti2004; Pagliosa, Reference Pagliosa2006; Pires-Vanin et al., Reference Pires-Vanin, Arasaki and Muniz2013), preventing specific identification and comparison to other valid species (Gusmão et al., Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016). Hence, a detailed taxonomic study focusing on family Edwardsiidae is imperative to advance our understanding of the diversity of the group, and to inform future inventories and ecological studies of burrowing sea anemones in Brazil.

Materials and methods

Specimens examined

The descriptions of the taxa examined in the present study are based on unidentified specimens stored at the Marine Invertebrate Collections of the Museu Oceanográfico da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (MOPE), the Museu Nacional da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (MNRJ) and Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo (MZUSP).

Anatomical and microanatomical observations

We followed, whenever possible, the identification procedure proposed by Häussermann (Reference Häusserman2004). Formalin-fixed specimens were initially separated in morphotypes and examined whole, dissected and as serial sections. At least two whole individuals of each species examined were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin, cut in histological sections, 6–10 µm thick, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (Humason, Reference Humason1962). The cnidom of each species was determined from squash preparations of tentacles, column (and nemathybomes when present), actinopharynx and filaments. Cnidae capsules of at least two individuals per taxa were identified and 20 undischarged capsules of each type found were measured, whenever possible. Due to small size and small number of individuals, and because individuals are partially destroyed during cnidae sampling, we limited to three the number of individuals used for cnidom. For general cnidae terminology, we use a combination of classifications to better capture the underlying variation in cnidae morphology: the classification of Weill (Reference Weill1934) modified by Carlgren (Reference Carlgren1940) is combined with that of Schmidt (Reference Schmidt1969, Reference Schmidt1972, Reference Schmidt1974) thus we differentiate ‘basitrichs’ from ‘b-mastigophores’ but also capture the underlying variation seen in ‘rhabdoids’. In addition, we used England (Reference England1987) to differentiate nematocysts in the nemathybomes (i.e. pterotrichs from basitrichs). Photographs of each type of nematocyst were included to allow reliable comparison across terminologies and taxa (see Fautin, Reference Fautin1988). Higher classification of Actiniaria follows Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Barbeitos, Brugler, Crowley, Grajales, Gusmão, Hausserman, Reft and Daly2014).

Results

Here we describe a new genus with two new species and a new species of the previously described genus Scolanthus. Isoscolanthus gen. nov. includes two new species: Isoscolanthus iemanjae sp. nov. and Isoscolanthus janainae sp. nov. Scolanthus crypticus sp. nov. is the first species of the genus recorded for the South-western Atlantic, expanding the range of the genus to the tropical South-western Atlantic. In addition, we expand the distribution of Edwardsia migottoi, previously known only from the South-east coast of Brazil (Gusmão et al., Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016), to include the North-east coast of Brazil (Pernambuco state). The distribution of Nematostella vectensis Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935, recorded only from the north-east coast of Brazil (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Lima, Perez and Gomes2010), is also expanded to include the south coast of Brazil (Paraná state) (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Map showing the distribution of species of Edwardsiidae recorded from Brazil. Different symbols represent different species.

SYSTEMATICS

Order ACTINIARIA Hertwig, Reference Hertwig1882

Suborder ANENTHEMONAE Rodríguez & Daly in Rodríguez et al., 2014

Superfamily EDWARDSIOIDEA Andres, Reference Andres1881

Family EDWARDSIIDAE Andres, Reference Andres1881

Diagnosis (adapted from Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1949 with modifications from Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008; modifications in bold). Anenthemonae with elongate, vermiform body usually divisible into two or more regions: between long scapus provided with periderm and short capitulum may be short scapulus that lacks periderm and epidermal specializations. Proximal end rounded, without basilar muscles, may be differentiated into a physa. Single weak siphonoglyph. No sphincter muscle or acontia. Mesenteries divisible into macro- and microcnemes; always eight macrocnemes and at least four microcnemes. Macrocnemes comprise two pairs of directives and four lateral mesenteries, two on each side, whose retractors face sulcar (=ventral) directives. Retractors restricted, diffuse to strongly circumscript; parietal muscles always distinct.

Cnidom: Spirocysts, basitrichs, b-mastigophores, p-mastigophores A, pterotrichs, t-mastigophores.

Type species Edwardsia beautempsii de Quatrefages, Reference de Quatrefages1842 designated by Carlgren (Reference Carlgren1949).

Remarks. We modified the familial diagnosis to reflect recent changes in higher-level classification of Actiniaria (i.e. Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Barbeitos, Daly, Gusmão and Häussermann2012, Reference Rodríguez, Barbeitos, Brugler, Crowley, Grajales, Gusmão, Hausserman, Reft and Daly2014) and the combination of nematocyst terminology used in this study. These modifications have been made in all other diagnoses included in this study.

Isoscolanthus gen. nov.

Edwardsiidae with column divided in a distinct proximal end, scapus, scapulus and capitulum. Scapus and proximal end with periderm and scattered nemathybomes. Nemathybomes with pterotrichs. Eight macrocnemes span body length; four microcnemes present only in capitulum. Tentacles 12 in adults arranged in two cycles; all of same size or outer longer than inner ones. Retractor muscles well developed, circumscribed; parietal muscle well developed, symmetrical. Cnidom: spirocysts, basitrichs, pterotrichs and p-mastigophores A.

Type species. Isoscolanthus iemanjae sp. nov.

Etymology. The genus was named Isoscolanthus (from Greek isos ‘equal’ + Scolanthus ‘a genus of sea anemones’) due to its morphological similarity with Scolanthus Gosse, Reference Gosse1853. Gender: Masculine.

Remarks. Isoscolanthus gen. nov. is differentiated from other edwardsiids based on external morphology and cnidom. The presence of nemathybomes in members of Isoscolanthus gen. nov. differentiates the genus from species of Nematostella, Drillactis Verrill, Reference Verrill1922, Edwardsiella Andres, 1883, Paraedwardsia Carlgren in Nordgaard, Reference Nordgaard1905, and Synhalcampella Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1921, all of which lack this columnar specialization. All remaining genera within Edwardsiidae (i.e. Scolanthus, Edwardsia, Edwardsianthus England, Reference England1987 and Halcampogeton Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1937) present nemathybomes on the column as well. The presence of periderm and nemathybomes on proximal end differentiates Isoscolanthus gen. nov. from Edwardsia, Edwardsianthus and Halcampogeton. Isoscolanthus gen. nov. is differentiated from Scolanthus by the number of microcnemes (four in Isoscolanthus gen. nov.; at least eight in Scolanthus) and, consequently, by the number of tentacles (12 in Isoscolanthus gen. nov.; 16 or more in Scolanthus). The type of nematocyst in nemathybomes further differentiates Isoscolanthus gen. nov. from Scolanthus (pterotrichs in Isoscolanthus gen. nov; basitrichs in Scolanthus).

Despite the presence of a distinct proximal end in Isoscolanthus gen. nov., the epidermis of the region is not thickened and well differentiated from the scapus as seen in species with true physa sensu Carlgren & Stephenson (Reference Carlgren and Stephenson1928) (e.g. Edwardsia and Nematostella Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935). Instead, the proximal end of Isoscolanthus gen. nov. has a narrower mesoglea compared to the scapus and, in some specimens, a slight constriction separating scapus from proximal end; this may also be observed in species of Scolanthus (e.g. S. callimorphus: Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1979).

Isoscolanthus iemanjae sp. nov.

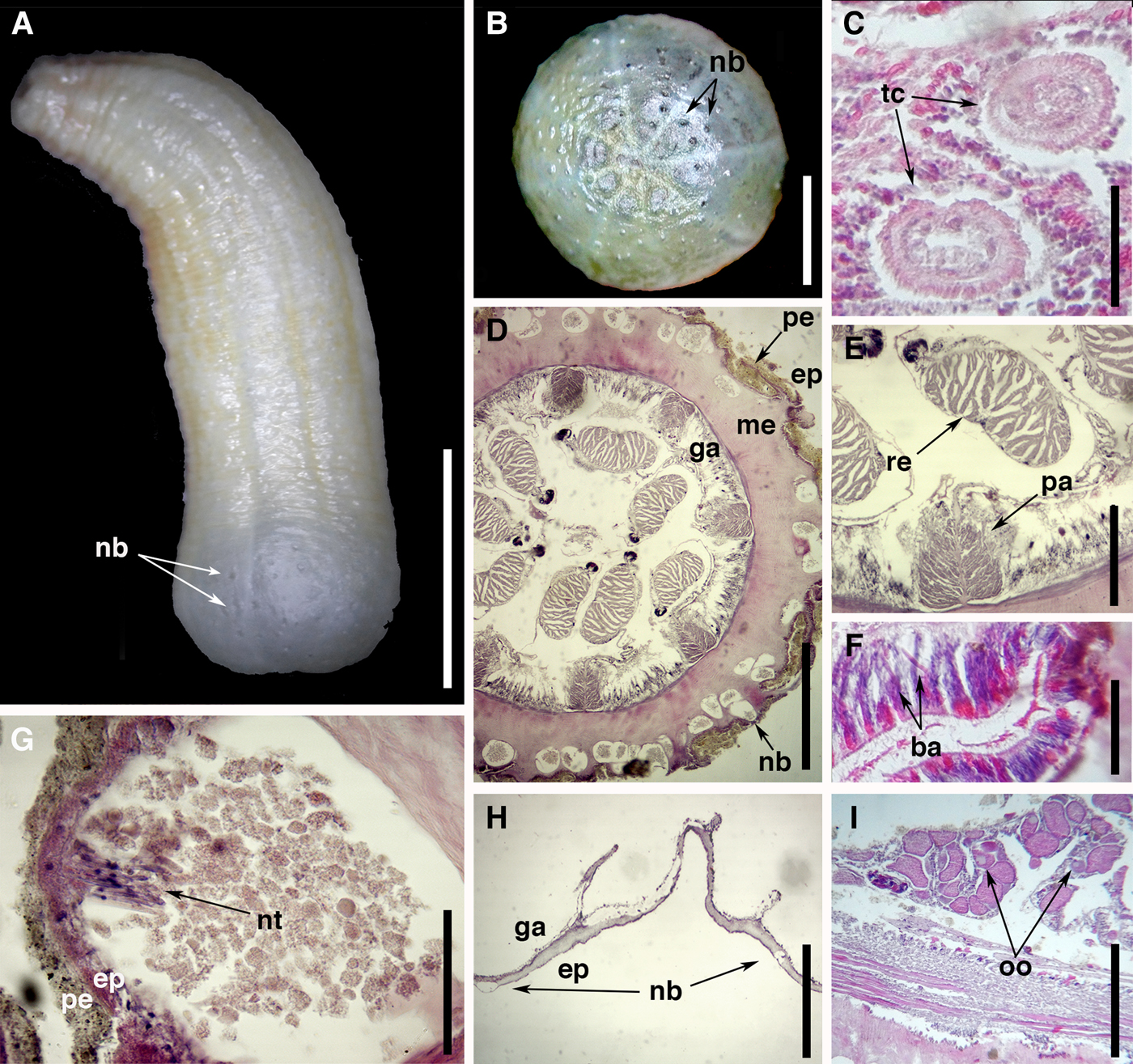

(Figures 2–3, Table 1)

TYPE MATERIAL (6 specimens)

Holotype: MZUSP 2723, 1 adult specimen, 902 m depth, Bacia de Campos (22°42′S 40°10′W), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, sample date unknown.

Fig. 2. External anatomy and microanatomy of Isoscolanthus iemanjae gen. et sp. nov.: (A) general view of a preserved specimen showing proximal rounded end with nemathybomes (arrows); (B) detail of proximal rounded end with several nemathybomes (arrows); (C) cross-section of two tentacles (arrows); (D) cross-section through mid-column showing several nemathybomes distributed in mesoglea of column and pairs of macrocnemes; (E) cross-section through mid-column showing a macrocneme with parietal and retractor muscle; (F) detail of actinopharynx showing large basitrichs (arrows); (G) detail of a nemathybome with pterotrichs (arrow); (H) detail of rounded proximal end with nemathybomes (arrows); (I) cross-section through mid-column showing gametogenic tissue of a macrocneme with oocytes (arrow). Abbreviations: ba, basitrich; ep, epidermis; ga, gastrodermis; me, mesoglea; nb, nemathybomes; nt, nematocysts; oo, oocytes; pa, parietal muscle; pe, periderm; re, retractor muscle; tc, tentacle. Scale bars: A, 20.0; B, 3.0; C, 0.17; D, 0.7; E, 0.4; F, 0.12; G, 0.04; H, 0.3; I, 0.2 mm.

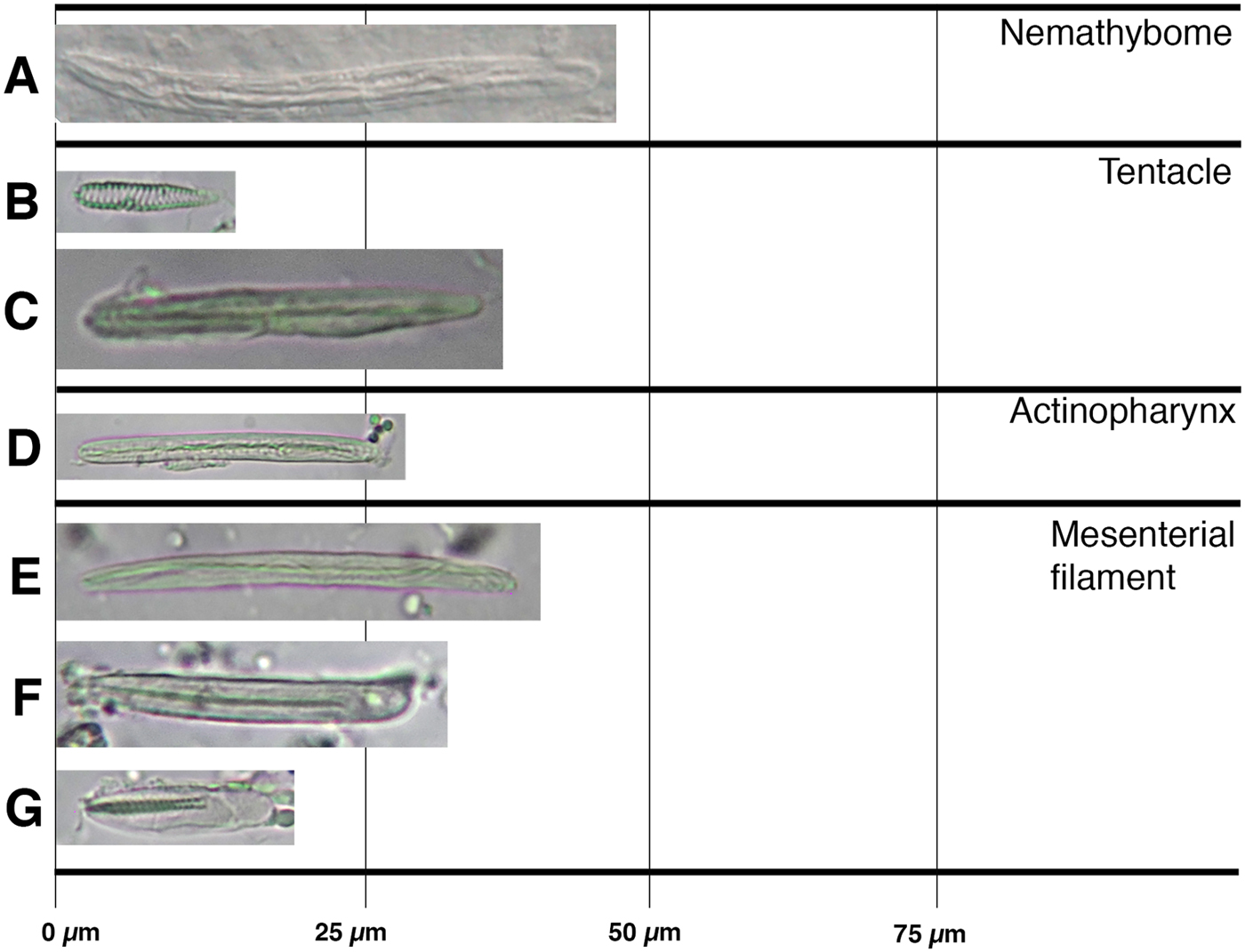

Fig. 3. Cnidom of Isoscolanthus iemanjae sp. nov.: (A) pterotrich; (B) spirocyst; (C) basitrich; (D) basitrich I; (E) basitrich II; (F) basitrich I; (G) basitrich II; (H) p-mastigophore A; (I) holotrich I; (J) holotrich II. *Nematocysts present possibly due to contamination.

Table 1. Size ranges of the cnidae of Isoscolanthus iemanjae gen. nov. et sp. nov.

![]() $\bar{X}$, mean; SD, standard deviation; S, proportion of specimens in which each cnidae was found; N, Total number of capsules measured.

$\bar{X}$, mean; SD, standard deviation; S, proportion of specimens in which each cnidae was found; N, Total number of capsules measured.

a Cnidae present probably due to contamination (see species remarks).

Paratypes: MZUSP 2713, 1 adult specimen, 212 m depth, Bacia de Campos (22°41′S 40°37′ W), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, sample date unknown. MZUSP 2715, 1 adult specimen, 212 m depth, Bacia de Campos (22°41′S 40°37′ W), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, sample date unknown. MZUSP 2717, 1 adult specimen, 902 m depth, Bacia de Campos (21°08′S 40°10′W), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, sample date unknown; MZUSP 2718, 1 adult specimen, 902 m depth, Bacia de Campos (21°08′S 40°10′W), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, sample date unknown. MZUSP 2724, 1 adult specimen, 902 m depth, Bacia de Campos (21°08′ S 40°10′W), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, sample date unknown.

DIAGNOSIS

Isoscolanthus with column mesoglea thicker distally than proximally. Retractor muscle without pennon. Parietal muscle strong, well developed and ~ two-thirds the size of retractor muscle. Actinopharynx with a very long category of basitrichs (50.7–100.1 × 3.6–5.1 µm).

DESCRIPTION

External anatomy

Proximal end rounded, externally differentiated from rest of column but not true physa (Figure 2A); no central pore present. Column robust, length 15–20 mm and diameter 6–9 mm; wider proximally than distally; divided in four regions: well delimited proximal end, scapus, scapulus and capitulum. All examined specimens with distal portion of column retracted, including part of scapus, scapulus and capitulum. Periderm fine-grained, tightly adherent, covering whole column from distal scapus to proximal end (Figure 2A, B). Nemathybomes single, conspicuous, scattered on column from distal scapus to proximal end; sparser on scapus (Figure 2A), but more aggregated on proximal end (Figure 2A, B). Tentacles small, always 12 in adults, arranged in two cycles, presumably all of same size (Figure 2C).

Internal anatomy and microanatomy

Mesenterial arrangement typical for Edwardsiidae: eight macrocnemes span length of body (Figure 2D), four microcnemes only in capitulum at base of tentacles. Retractor muscle of macrocnemes relatively weak, circumscribed (Figure 2D), without proximal pennon (Figure 2E). Retractor with few muscle processes (15 in average) variable in height, with low degree of ramification, more branched closer to body wall (Figure 2E). Parietal muscle large, almost same size as retractor, well developed, symmetrical, ovoid, with 12–14 processes, most branched closer to body wall; central lamella of equal thickness, forming peduncle of 0.01 mm (Figure 2E). Actinopharynx thick, with long basitrichs present (Figure 2F). Mesoglea thicker distally at actinopharynx level (0.3 mm) than at gastrovascular cavity level (0.06 mm). Nemathybomes conspicuous, sunken into mesoglea, most below epidermis but some protruding into it; filled with grain-like particles and pterotrichs (Figure 2G). Nemathybomes on proximal end generally smaller than those in scapus (Figure 2H). Gametogenic tissue occurs right below actinopharynx where filaments are very reduced. Gonochoric; all examined specimens with oocytes (Figure 2I).

Cnidom

Spirocysts, basitrichs, pterotrichs and p-mastigophores A. See Figure 3 and Table 1 for size and distribution.

Distribution

The species is known from three collection sites in the type locality of Bacia de Campos, off the coast of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between 202–902 m depth.

Etymology

Species named after the water deity Yemoja from the Yoruba religion. In Brazil, Iemanjá (as it is written in Portuguese) is known as ‘The Queen of the Ocean’ and worshipped by followers of Candomblé and Umbanda.

Remarks

We did not include the holotrichs found in filaments of I. iemanjae sp. nov. in the cnidom of the genus (or the species) as these nematocysts were found in only one specimen. We believe it is a case of contamination by feeding similar to the one described for E. migottoi (see Gusmão et al., Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016).

TYPE MATERIAL (11 specimens)

Holotype: MNRJ 8688, 1 adult specimen, 295–300 m depth, offshore Rio de Janeiro (21°31′S 40°08′W), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (St. 56 CB96), coll. 1987 by TAAF.

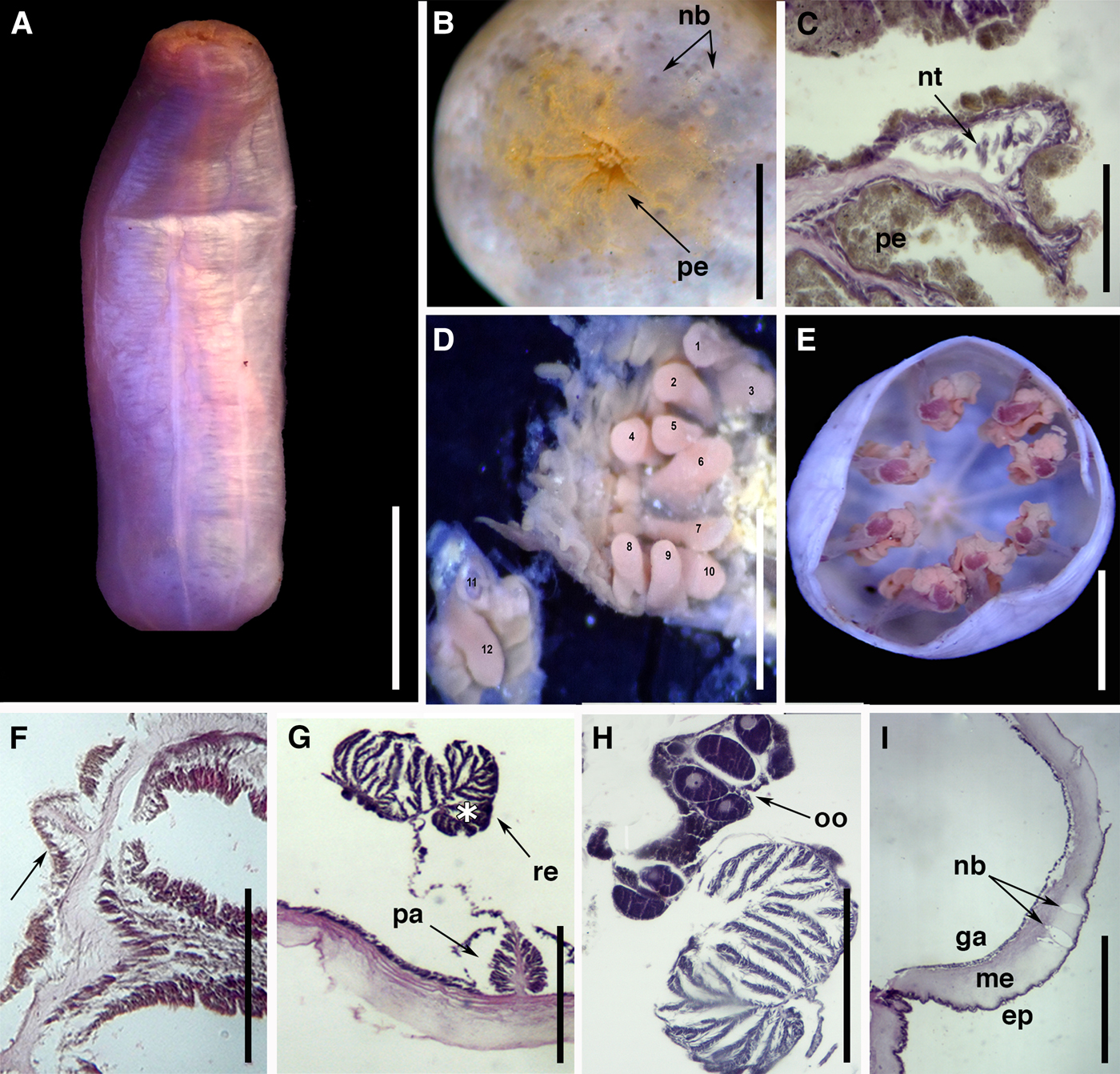

Fig. 4. External anatomy and microanatomy of Isoscolanthus janainae sp. nov.: (A) Lateral view of a preserved specimen; (B) detail of proximal rounded end with sparse periderm and several nemathybomes (arrows); (C) detail of a nemathybome with nematocysts; note the periderm; (D) detail of distal column showing the 12 tentacles; (E) cross-section through mid-column showing eight macrocnemes; (F) cross-section through capitulum showing a microcneme at the base of tentacles (arrow); (G) detail of a macrocneme showing parietal and retractor muscle with a pennon (asterisk); (H) detail of retractor with large pennon and gametogenic tissue with oocytes; (I) longitudinal section through column showing nemathybomes in mesoglea (arrows). Abbreviations: ep, epidermis; ga, gastrodermis; me, mesoglea; nb, nemathybomes; nt, nematocysts; oo, oocytes; pa, parietal muscle; pe, periderm; re, retractor muscle. Scale bars: A, 10.0; B, 3.0; C, D, 0.1; E, 3.0; F, 0.6; G, 0.25; H, 0.20; I, 0.5 mm.

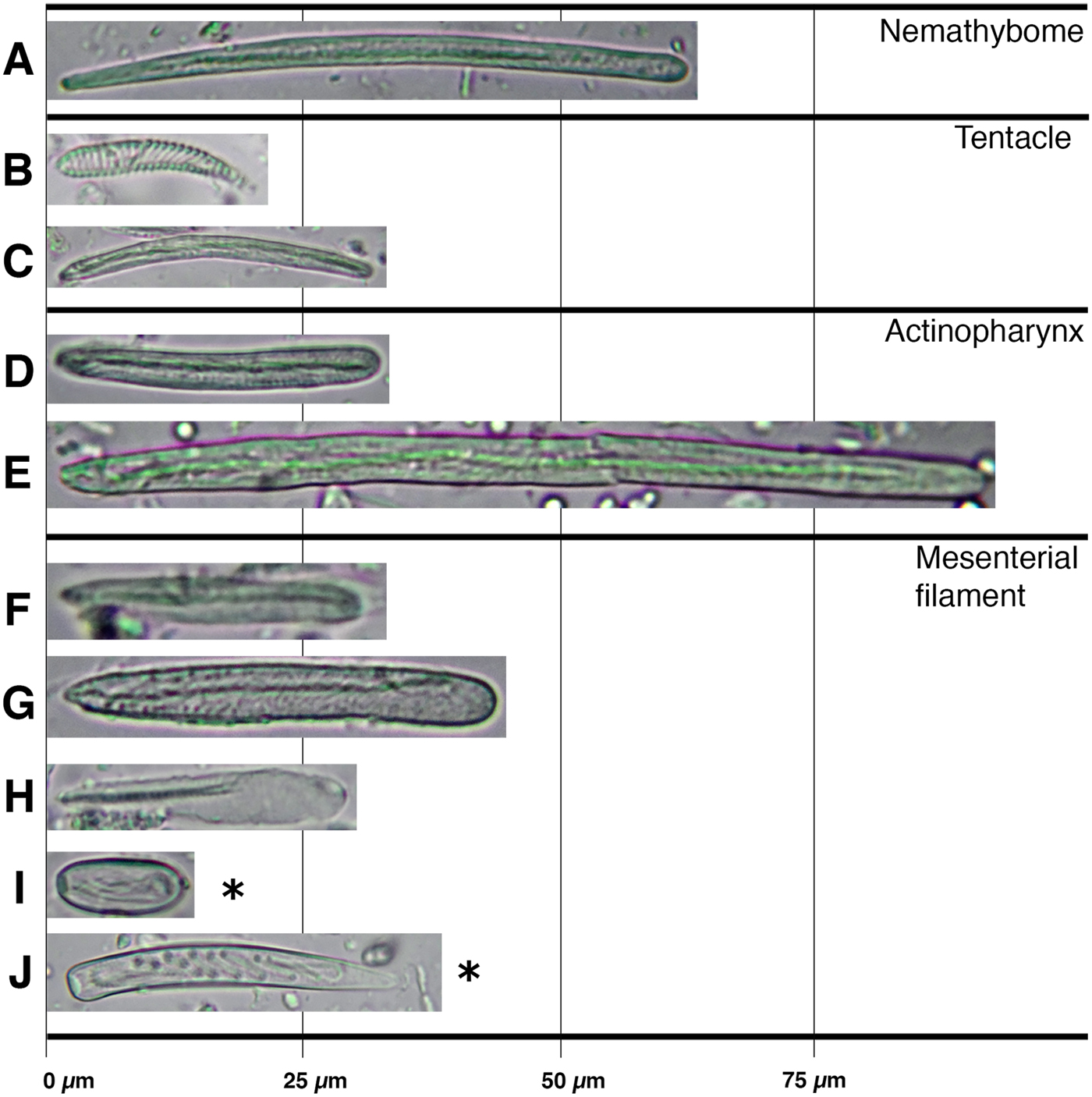

Fig. 5. Cnidom of Isoscolanthus janainae sp. nov.: (A) pterotrich; (B) spirocyst; (C) basitrich; (D) basitrich; (E) basitrich I (F) basitrich II; (G) p-mastigophore A.

Table 2. Size ranges of the cnidae of Isoscolanthus janainae gen. nov. et sp. nov.

![]() $\bar{X}$, mean; SD, standard deviation; S, proportion of specimens in which each cnidae was found; N, Total number of capsules measured.

$\bar{X}$, mean; SD, standard deviation; S, proportion of specimens in which each cnidae was found; N, Total number of capsules measured.

Paratypes: MZUSP 2729, 10 specimens, sampled at same site and point of the holotype. Additional material: MZUSP 7937, 105 specimens, Rio de Janeiro (21°31′S 40°08′W), Brazil, coll. 31/v/1987 by TAAF.

DIAGNOSIS

Isoscolanthus with retractor muscle with pennon. Parietal muscle at least one-third the size of retractor muscle. Small category of basitrichs in actinopharynx (26.7–46.2 × 3.0–4.9 µm).

DESCRIPTION

External anatomy

Proximal end rounded, differentiated from rest of column but not true physa (Figure 4A); no central pore present. Column delicate, length 8–20 mm and diameter 3–7 mm, divided in four regions: well delimited proximal end, scapus, scapulus and very short capitulum. Periderm thin, not adherent, deciduous, covering whole column from distal scapus to proximal end (Figure 4B, C); most specimens did not have periderm on scapus or proximal end. Nemathybomes single (Figure 4C), inconspicuous, scattered on column from distal scapus to proximal end; larger on scapus (Figure 4C) than in proximal end (Figure 4B). Nemathybomes arranged in longitudinal rows between insertions of macrocnemes (Figure 4A). Tentacles 12 in adults, arranged in two cycles with outer ones presumably longer than inner ones (Figure 4D).

Internal anatomy and microanatomy

Mesenterial arrangement typical for Edwardsiidae: eight macrocnemes span length of body (Figure 4E), four microcnemes only in capitulum at base of tentacles (Figure 4F). Retractor muscle of macrocnemes strong, circumscribed, with easily recognizable pennon (Figure 4G, H). Retractor with relatively numerous processes (14–20) and few ramifications, more branched at the pennon (Figure 4G, H). Parietal muscle small, symmetrical, ovoid, with 16–19 lateral processes relatively unbranched; central lamella forming peduncle 0.015 mm wide closer to body wall (Figure 4G). Mesoglea thicker distally at the actinopharynx level (0.27 mm) than at gastrovascular cavity level (0.06–0.13 mm). Nemathybomes single, inconspicuous, sunken into mesoglea, most below epidermis (Figure 4I) but some protruding into it (Figure 4C); with only pterotrichs. Proximal end with small invagination but no terminal pore (Figure 4I). Gonochoric; all examined specimens with oocytes (Figure 4H).

Cnidom

Spirocysts, basitrichs, pterotrichs and p-mastigophores A. See Figure 5 and Table 2 for size and distribution.

Distribution

The species is known from a single collection site in the type locality (21°31′S 40°08′W), off the coast of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between 295–300 m depth.

Etymology

Species also named after water deity Yemoja from the Yoruba religion which receives different names in Brazil, one of which is Janaína.

Remarks

Due to the poor preservation state of the material, only a few specimens exhibited preserved nemathybomes and these exhibited a reduced number of undischarged nematocysts.

Despite the uniformity in external and internal anatomy and cnidom seen in members of Isoscolanthus gen. nov., the two species of the genus can be differentiated by microanatomical features and cnidae: mesenteries have retractors much larger and with a pennon and parietal muscles larger and more branched in Isocolanthus iemanjae sp. nov. than in Isoscolanthus janainae sp. nov.; although pterotrichs in the nemathybomes partially overlap in their lower range, I. iemanjae sp. nov. has much longer pterotrichs (32.6–71.5 × 2.8–4.0 µm) compared with I. janainae sp. nov. (40.0–47.0 × 3.2–4.0 µm). Likewise, nematocyst sizes are generally larger in other tissues of I. iemanjae sp. nov. than in I. janainae sp. nov. (e.g. basitrichs in tentacles, p-mastigophores A in filaments), with a category of basitrichs in I. iemanjae sp. nov. not found in I janainae sp. nov. Although both species co-occur in Bacia de Campos, Rio de Janeiro, I. iemanjae sp. nov. has a broader bathymetric range (212–902 m) only overlapping in shallower depths with I. janainae sp. nov. (i.e. 295–300 m).

Genus Scolanthus Gosse, Reference Gosse1853

Diagnosis

(Adapted from Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008 and Manuel, Reference Manuel1981a, Reference Manuel1981b; additions in italics) Edwardsiidae with body divisible into scapus and scapulus. Proximal region of body rounded, provided with nemathybomes and periderm; nemathybomes scattered or forming several longitudinal rows on scapus. Nemathybomes with basitrichs. At least eight microcnemes. Tentacles at least 16 in adults, arranged octamerously; inner ones shorter than outer ones. Retractor muscles relatively large, well developed, diffuse to circumscript; parietal muscles distinct, symmetrical, well-developed. Cnidom: spirocysts, basitrichs, b-mastigophores and p-mastigophores A.

Type species

Scolanthus callimorphus Gosse, Reference Gosse1853 by monotypy

Remarks

We have included in the diagnosis of Scolanthus the presence of periderm in the proximal end as this character can help differentiate species of this genus from other edwardsiid genera. Although we acknowledge most Scolanthus species have imperfectly known cnidom (Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008) and the distinction between basitrichs and pterotrichs can be difficult without observation of discharged capsules (Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008), all species of Scolanthus described have nemathybomes with basitrichs. This includes the recently described species Scolanthus triangulus Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008 and Scolanthus scamiti Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008, which undoubtedly have basitrichs in the nemathybomes (e.g. Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008). This information is included in the diagnosis pending a revision of the genus.

TYPE MATERIAL (41 specimens)

Holotype: MNRJ 8687, 1 Adult specimen, 40 m depth offshore São Sebastião (23°50′S 45°10′W), São Paulo, Brazil. coll. 19/iv/1986.

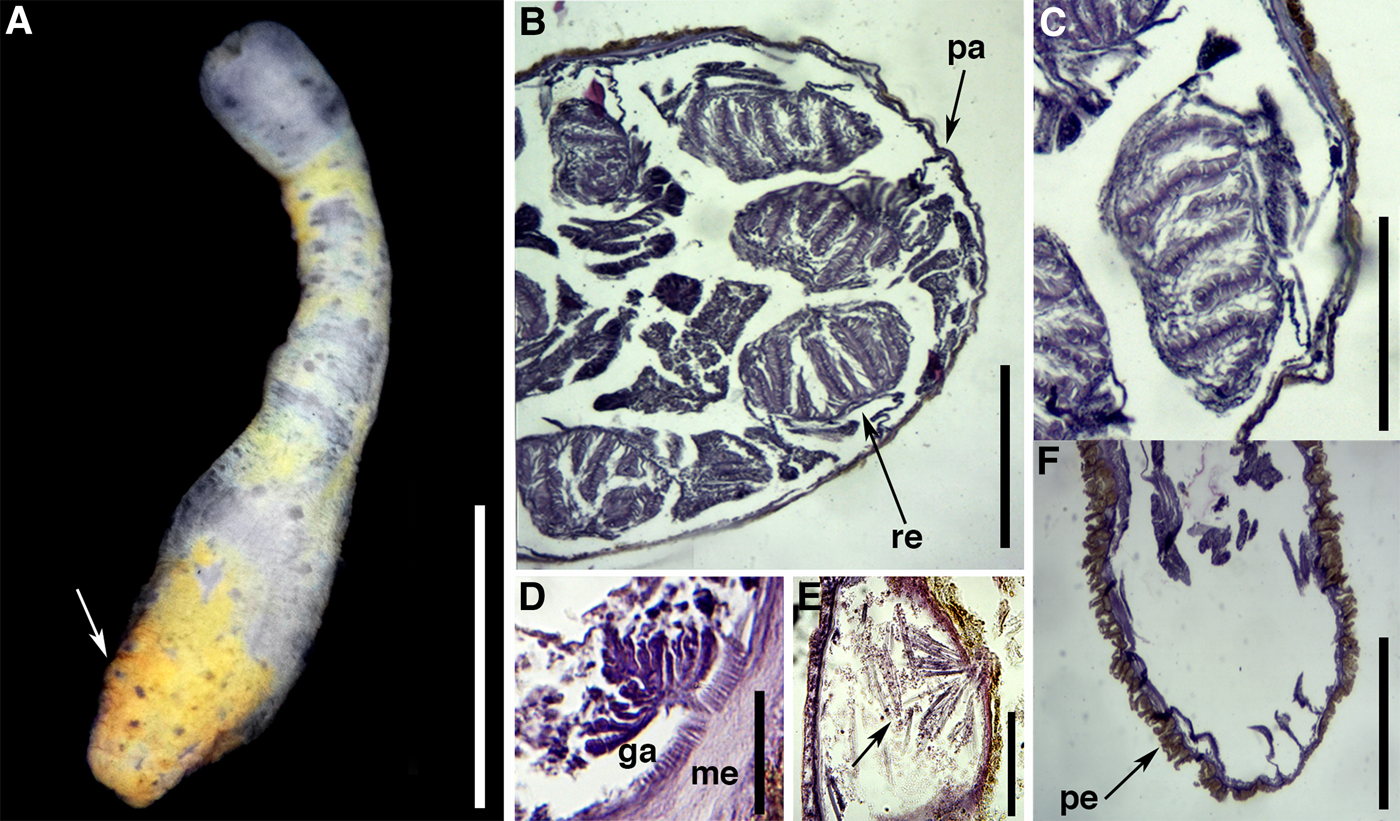

Fig. 6. External anatomy and microanatomy of Scolanthus crypticus sp. nov.: (A) general view of a preserved specimen showing proximal rounded end with periderm and nemathybomes (arrow); (B) cross-section through mid-column showing pairs of macrocnemes; (C) detail of a macrocneme showing poorly developed retractor muscle; (D) detail of small parietal muscle; (E) detail of a nemathybome with nematocysts; (F) longitudinal section through proximal end showing periderm. Abbreviations: ga, gastrodermis; me, mesoglea; pa, parietal muscle; pe, periderm; re, retractor. Scale bars: A, 5; B, 0.4; C, 0.15; D, 0.06; E, 0.05; F, 0.5 mm.

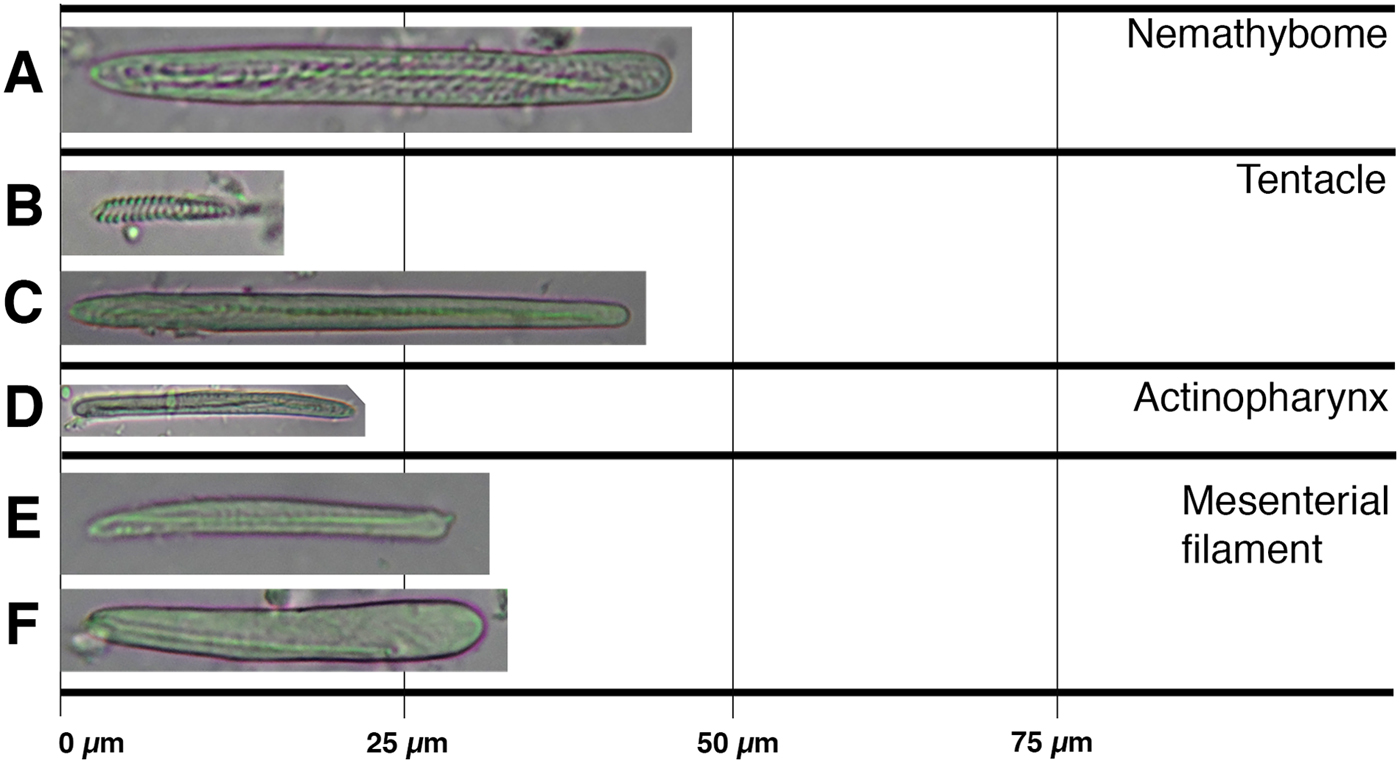

Fig. 7. Cnidom of Scolanthus crypticus sp. nov.: (A) basitrich; (B) spirocyst; (C) basitrich; (D) basitrich; (E) basitrich; (F) basitrich.

Table 3. Size ranges of the cnidae of Scolanthus crypticus sp. nov.

![]() $\bar{X}$, mean; SD, standard deviation; S, proportion of specimens in which each cnidae was found; N, Total number of capsules measured.

$\bar{X}$, mean; SD, standard deviation; S, proportion of specimens in which each cnidae was found; N, Total number of capsules measured.

Paratypes: MNRJ 8686, 10 adult specimens, sampled with the type; MOPE 0873, 6 adult specimens, 35 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°39′S 44°53′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 20/iv/1986. MOPE 0874, 6 adult specimens, 47 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°38′S 44°49′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 22/i/1986. MOPE 0875, adult 4 specimens, 35 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°40′S 44°59′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 20/iv/1986. MNRJ 8684, 7 adult specimens, 45 m depth offshore Ubatuba (23°44′S 45°00′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 20/i/1986. MNRJ 8685, 8 adult specimens, 40 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23° 34′S 44°48′ W) São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 22/i/1986.

DIAGNOSIS

Scolanthus with inconspicuous nemathybomes arranged in longitudinal rows between macrocnemes; thick periderm present. Tentacles with long basitrichs (26.9–56.5 × 2.5–4.2 µm). Nemathybome nematocysts shorter than 60 µm (24.3–56.3 × 3.9–5.5 µm). Length of whole animal in contraction to 15 mm, diameter 2.0–4.0 mm.

DESCRIPTION

External anatomy

Most specimens examined with proximal end damaged. Proximal end rounded, not differentiated in true physa (Figure 6A). Column delicate, slender, length 10.0–15.0 mm and diameter 2.0–4.0 mm, divided in two regions: scapus and scapulus. Periderm thick, adherent, orange, composed of fine mud grains, covering scapus (Figure 6A). Nemathybomes single, inconspicuous, in longitudinal rows between insertions of macrocnemes from distal scapus to proximal scapus (Figure 6A). Tentacles up to 16 in adults; presumably arranged in two cycles.

Internal anatomy and microanatomy

Eight macrocnemes span length of body, eight microcnemes only in scapulus at the base of tentacles. Retractor muscle of macrocnemes poorly developed, circumscribed, without proximal pennon (Figure 6B, C). Retractor muscle with 5–7 processes of similar height and low degree of ramification (Figure 6C). Parietal muscle small, poorly developed, asymmetrical, triangular; central lamella forming peduncle no more than 0.003 mm wide (Figure 6B, D). Mesoglea of column thicker distally (0.03 mm) than proximally (0.006 mm). Nemathybomes relatively small, inconspicuous, sunken into mesoglea, distributed in longitudinal rows between macrocneme insertions (Figure 6E), most protruding into epidermis (Figure 6E). Proximal region of body with thick periderm, nemathybomes and mesogleal projections (Figure 6F). All examined individuals sterile.

Distribution and natural history

This species is known from its type locality (23°50′S 45°10′W) and five collection sites off the coast of São Paulo between São Sebastião and Ubatuba, Brazil, between 35–47 m depth.

Etymology

The species was always found among specimens of E. migottoi and at first glance they looked very alike. Therefore it was named ‘crypticus’, the latin term for ‘cryptic’.

Remarks

Species within Scolanthus are differentiated mainly by geographic distribution, nemathybome arrangement and cnidom. Scolanthus crypticus sp. nov. is the first species of the genus recorded for the South-western Atlantic Ocean, the other species being from the North Atlantic Ocean (S. callimorphus Gosse, Reference Gosse1853; Scolanthus ingolfi (Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1921); Scolanthus curacaoensis (Pax, 1924); Scolanthus nidarosiensis (Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1942)), Atlantic portion of the Southern Ocean (S. intermedius), and Pacific Ocean (Scolanthus ignotus (Carlgren, 1922), Scolanthus armatus (Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1931), S. triangulus, S. scamiti). In addition, Scolanthus crypticus sp. nov. belongs to a group of species within Scolanthus lacking p-mastigophores A (together with the type species S. callimorphus, S. armatus, S. ingolfi, S. ignotus and S. triangulus). Of those species, only S. crypticus sp. nov. and S. callimorphus have nemathybomes arranged in longitudinal rows, all other species have them scattered on scapus and proximal end. These two species can be further differentiated based on the non-overlapping size range of basitrichs in nemathybomes (24.28–56.33 × 3.93–5.54 µm in S. crypticus sp. nov.; 62.4–87.0 × 3.0–4.8 µm in S. callimorphus), and geographic distribution (S. crypticus sp. nov. in South-western Atlantic; S. callimorphus in North-east Atlantic). Regarding microanatomical traits, S. crypticus sp. nov. resembles S. triangulus as both have weak retractors with few muscle processes. However, these two species can be differentiated by length of basitrichs in nemathybomes (50–60 µm in S. crypticus sp. nov.; 63–89 µm in S. triangulus), non-overlapping geographic distribution (S. crypticus sp. nov. in Atlantic; S. triangulus in Pacific) and disjunct bathymetry (S. crypticus sp. nov. collected up to 47 m; S. triangulus collected from 85 m to 271 m).

All individuals of S. crypticus sp. nov. were collected together with specimens of E. migottoi indicating a pattern of sympatry commonly found between species of Edwardsia and Scolanthus (see Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008).

Genus Nematostella Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935

Diagnosis

See Stephenson (Reference Stephenson1935)

Type species

Nematostella vectensis Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935 by original designation.

Nematostella vectensis Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935

(Figure 8A)

Nematostella vectensis: Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935; Pax, Reference Pax1936; Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1945; Hand, Reference Hand1957; Sanders, Mangelsdorf & Hampson, Reference Sanders, Mangelsdorf and Hampson1965; Williams, Reference Williams1973; Manuel, Reference Manuel1981a, Reference Manuel1981b; Hand & Uhlinger, Reference Hand and Uhlinger1994; Williams, Reference Williams2003; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Lima, Perez and Gomes2010.

Fig. 8. External anatomy and microanatomy of Nematostella vectensis Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935 and Edwardsia migottoi Gusmão, Brandão & Daly, Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016 (A) general view of a preserved specimen of Nematostella vectensis; note the column without any specialization; (B) general view of a preserved specimen of Edwardsia migottoi showing longitudinal rows of nemathybomes with periderm and physa without periderm. Scale bars: A, 2.0; B, 10 mm.

Nematostella pelucida: Crowell, Reference Crowell1946; Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1949.

DIAGNOSIS

See Williams (Reference Williams1975)

Examined material (19 individuals)

MOPE 0876, 6 individuals, 0–2 m, depth, Baía de Guaratuba (25°52′S 48°42′W), Paraná, Brazil, coll. iii/2012; MOPE 0877, 7 individuals, 0–2 m depth, Baía de Guaratuba (25°51′S 48°38′W), Paraná, Brazil, coll. x/2012; MOPE 0878, 6 individuals, 0–2 m depth, Baía de Guaratuba (25°51′S 48°38′W), Paraná, Brazil, coll.xi/2012.

Distribution

Nematostella vectensis was originally described from England, off the coast of Isle of Wight (Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1935), with its current distribution now including other localities around the English coast (Reitzel et al., Reference Reitzel, Darling, Sullivan and Finnerty2008), the east and west coasts of the USA (Reitzel et al., Reference Reitzel, Darling, Sullivan and Finnerty2008) and the north-east of Brazil (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Lima, Perez and Gomes2010). Here we extend the distribution of the species in Brazil to include the state of Paraná in the south coast of Brazil, between 0–2 m depth.

Remarks

All specimens examined were stained with Rose Bengal by the collector (Gisele Morais, Federal University of Paraná) which hindered detailed examination of external anatomical characters. Additionally, given the small size of individuals we could not examine the cnidae from actinopharynx with the precision necessary to avoid contamination. Microanatomical and cnidae features of the specimens examined, however, closely agree with those given by Williams (Reference Williams1975). Here we recorded the occurrence of N. vectensis for the state of Paraná in the south coast of Brazil in a harbour environment similar to the one described by Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Lima, Perez and Gomes2010) for the Port of Recife more than 3000 km away. Because it is not possible to confirm the presence of the species in Paraná before the study of Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Lima, Perez and Gomes2010), we cannot establish whether N. vectensis is spreading along the Brazilian coast.

Genus Edwardsia de Quatrefages, Reference de Quatrefages1842

Diagnosis

See Daly & Ljubenkov (Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008)

Type species

Edwardsia beautempsii de Quatrefages, Reference de Quatrefages1842 by subsequent designation (Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1949).

Edwardsia migottoi Gusmão, Brandão & Daly, Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016

(Figure 8B)

DIAGNOSIS

Very small individuals, length 1.7–6.3 mm; scapus covered by deciduous ferruginous periderm; eight longitudinal rows of tubercles with nemathybomes with two types of nematocysts: t-mastigophores (42.9–75.8 × 2.4–4.2 µm) and pterotrichs (59.8–119.1 × 3.9–7.1 µm).

Examined material

(32 individuals) MOPE 0867, 10 adult specimens, 44 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°34′S 44°48′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 22/i/1986; MOPE 0868 , 4 adult specimens, 20 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°43′S 45°13′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 21/i/1986; MOPE 0869, 6 specimens, 47 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°47′S 45°49′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 22/i/1986; MOPE 0870, 6 specimens, 46 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°45′S 45°00′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 26/x/1985; MOPE 08671, 1 specimen, 40 m depth, offshore Ubatuba (23°50′S 45°10′W), São Paulo, Brazil, coll. 27/x/1985; MOPE 0879, 5 specimens, 1 m depth, offshore Cabo de Santo Agostinho (8°25′S 34°57′W), Pernambuco, Brazil, coll. 14/xii/2015.

Distribution

Edwardsia migottoi is previously known only from its type locality in Praia do Araçá, São Sebastião (São Paulo). Here we extended the distribution of the species to include Ubatuba which is also located in the state of São Paulo, ~80 km from the type locality. In addition, the species has been collected in Cabo de Santo Agostinho in the state of Pernambuco, extending the distribution of the species to include the north-eastern coast of Brazil.

Remarks

Edwardsia migottoi is the only species of the genus known from Brazil. The specimens examined here closely agree with the description of Gusmão et al. (Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016). Unlike Gusmão et al. (Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016), however, we did not find holotrichs in the filament and did not observe a terminal pore in the physa. This small discrepancy does not compromise our identification as the presence of holotrichs in the filament of E. migottoi is hypothesized by Gusmão et al. (Reference Gusmão, Brandão and Daly2016) to result from contamination by feeding. In addition, the presence of a terminal pore can be difficult to observe in histological sections and is not considered a highly informative character for the systematics of the group.

Discussion

The importance of some traits to the circumscription of Isoscolanthus gen. nov.

Among other characters, mesentery and tentacle arrangement have often been used to distinguish species and genera within Actiniaria (Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1921; Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1949). In edwardsiids, the overall number of microcnemes and their location, which is directly related to number of tentacles, has been regarded as a character of generic importance. Edwardsianthus, for example, was erected by England (Reference England1987) to include species of Edwardsia with six pairs of microcnemes in the second cycle resulting in 20 tentacles as opposed to microcnemes developing in lateral and ventral exocoels resulting in the 12–36 tentacles seen in most species of Edwardsia. The phylogenetic analyses of Daly (Reference Daly2002) recovered Edwardsianthus as a distinct group more closely related to members of Scolanthus than Edwardsia, corroborating England's (Reference England1987) hypothesis that mesentery development and resulting microcneme arrangement may be a trait of systematic and taxonomic value. Both species of Isoscolanthus gen. nov. have four microcnemes and 12 tentacles which is a combination present in only seven species of Edwardsia (e.g. Daly et al., Reference Daly, Perissinotto, Laird, Dyer and Todaro2012) and no species of Scolanthus (England, Reference England1987). Based on our finds, we agree with previous authors that different modes of mesentery and tentacle development may be an important feature for the taxonomy and systematics of Edwardsiidae.

Isoscolanthus gen. nov. is the second genus of Edwardsiidae to have pterotrichs in its cnidom. Although England (Reference England1987) was the first to define pterotrichs, this nematocyst had been previously noted in nemathybomes of Edwardsia tuberculata by Düben & Koren (Reference Düben and Koren1847) and later in Edwardsia hantuensis by England (Reference England1987). Based on drawings by Manuel (Reference Manuel1977), England (Reference England1987) also inferred the presence of pterotrichs in Edwardsia timida de Quatrefages, Reference de Quatrefages1842 and Edwardsia beautempsi de Quatrefages, Reference de Quatrefages1842. An undischarged pterotrich capsule incorporates features of nematocysts without shaft (i.e. haplonemes) and those with a shaft (i.e. mastigophores) (England, Reference England1987). Pterotrichs have been identified as b-mastigophores by Carlgren (Reference Carlgren1940) and Manuel (Reference Manuel1977) but unlike b-mastigophores which have a homogeneous shaft, pterotrichs have a shaft divided in four regions: a basal part folded with few large pointed spines arranged spirally followed by a heavily armed region with thick close-set spines not arranged spirally, similar to the feathers of an arrow, and a distal-most region armed with small spirally arranged spines (England, Reference England1987). Pterotrichs were, until now, exclusive to some members of Edwardsia, usually co-occurring with t-mastigophores in nemathybomes of certain species (e.g. Edwardsia beautempsi, Edwardsia californica) (see England, Reference England1987 and Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008). In members of Isoscolanthus gen. nov., however, only pterotrichs are found in nemathybomes. Although the distinction between pterotrichs and b-mastigophores or basitrichs sensu Weill (Reference Weill1934) modified by Carlgren (Reference Carlgren1940) is not always straightforward based on undischarged capsules, the folded region in the proximal part of the capsule and its shape (i.e. thinner becoming broader distally) can help differentiate these nematocysts. We cannot comment on morphological differences between pterotrichs found in Edwardsia or Isoscolanthus gen. nov. as we did not observe discharged capsules, however the undischarged capsules are very similar.

The status of Scolanthus and the importance of cnidae in its circumscription

Scolanthus has a convoluted taxonomic history. Being first considered a synonymy of Edwardsia (Gosse, Reference Gosse1860), it was later resurrected by Manuel (Reference Manuel1981a, Reference Manuel1981b), who also synonymized Isoedwardsia Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1921 and Alfredus Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1979 under Scolanthus based on the presence of nemathybomes on the proximal end and absence of p-mastigophores A in their cnidom. The uncertainty regarding the presence of p-mastigophores A in Scolanthus has made its circumscription difficult, leading Manuel (Reference Manuel1981a, Reference Manuel1981b) to doubt membership of S. nidarosiensis and S. curacaoensis (former species of Isoedwardsia which have p-mastigophores A) within Scolanthus. Given that presence or absence of a type of nematocyst has been regarded as of generic importance (England, Reference England1987), Manuel's hesitation is understandable. The phylogenetic analyses by Daly (Reference Daly2002) recovered two species of Scolanthus without p-mastigophores A (S. armatus and S. callimorphus) in a monophyletic clade sister to a species of Edwardsia without p-mastigophores A (E. intermedia). Thus, Daly (Reference Daly2002) proposed to broaden the circumscription of Scolanthus to include E. intermedia (currently S. intermedius) and all other species with nemathybomes on proximal end whether or not they have p-mastigophores A. We agree with the circumscription of Scolanthus given by Daly & Ljubenkov (Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008) pending a revision of all species in the genus.

The presence of b-mastigophores in species of Scolanthus remains controversial. The only species which undoubtedly has b-mastigophores in addition to basitrichs in its cnidom is S. nidarosiensis (Carlgren, Reference Carlgren1942). Given that basitrichs can exhibit dense spines on the proximal tubule that may look like a rigid thickened shaft and, thus, be easily mistaken for a shaft of b-mastigophores (Cutress, Reference Cutress1955; Reft, Reference Reft2012), the absence of b-mastigophores in other Scolanthus could be explained by difficulties involved in distinguishing undischarged capsules of these nematocysts. Similarly, b-mastigophores may exhibit a very gradual change between shaft and terminal tubule, even as small as 0.1 µm, or the gradual change can be completely absent (Östman, Reference Östman, Bouillon, Boero, Cigogna and Cornelius1987, Reference Östman2000; Cutress, Reference Cutress1955), in which case no clear distinction exists between basitrichs and b-mastigophores. The nematocyst seen in the filaments of S. crypticus sp. nov. (Figure 7F) exemplifies this predicament. Although we identify these nematocysts as basitrichs, the shape of the capsule and size and morphology of the proximal tubule resembles aphyllonemes of Reft (Reference Reft2012) which are only known from filaments of family Actiniidae Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815. The size of undischarged capsules of aphyllonemes (32.8–36.6 × 2.5–3.6 µm; see Reft, Reference Reft2012) coincides with the nematocysts in filaments of S. crypticus sp. nov., except the latter were generally wider (30.5–35.6 × 3.9–6.0 µm). This is the first time aphyllonemes are hypothesized to occur in superfamily Edwardsioidea, but nematocysts seen in filaments of I. iemanjae sp. nov. (Figure 3G), Edwardsia juliae and Edwardsia olguini (Figures 5O and 7M respectively: see Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008) and actinopharynx of S. triangulus are also possibly aphyllonemes (see Figure 11H: Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008).

Alternatively, the use of different nematocyst nomenclatures might explain the presence of b-mastigophores in the diagnosis of Scolanthus in studies that use Schmidt's (Reference Schmidt1969, Reference Schmidt1972, Reference Schmidt1974) nomenclature which does not distinguish basitrichs from b-mastigophores (e.g. Manuel, Reference Manuel1981a, Reference Manuel1981b; Daly, Reference Daly2002; Daly & Ljubenkov, Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008). Given that all nominal species of Scolanthus have imperfectly known cnidom (England, Reference England1987) and no pictures or drawings of the nematocysts are included in descriptions, we left b-mastigophores in the diagnosis of the genus as presented by Daly & Ljubenkov (Reference Daly and Ljubenkov2008), pending a proper revision of all species of the genus, including the type S. callimorphus.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank A. Morandini from the University of São Paulo (IB/USP), P. Lana and G. Morais from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR) and A. Souto from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) for making material present in their laboratories available. We also thank Aline Beneti and Katia Christol dos Santos from the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo (MZUSP) and Débora Pires from the Museu Nacional (MNRJ) for helping with accession of material, museum loan and for room for RAB during his visit to the MZUSP and MNRJ collections, respectively. We would like to thank L. Manzzoni, D. Pires and C. Perez for their contributions and suggestions on the initial version of the manuscript.

Financial support

RAB received financial support through a master's scholarship from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). PBG and RAB received financial support from CNPq (PROTAX 2010-562320/2010-5 and BIOREEF 408934/2013-1). LCG was supported by E. Rodríguez and Janine Luke. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001).