INTRODUCTION

The Continuous Plankton Recorder (CPR) Survey started in the North Sea in 1931 and has been used for regular monitoring of the near-surface waters of the North Atlantic and North Sea for many decades (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Colebrook, Matthews and Aiken2003). Sampling in the North Pacific Ocean started with trial tows from California to Alaska in 1997 and regular sampling off the western coast of North America and between Vancouver and Japan started in 2000.

The routine analysis of samples includes identification of some taxa, e.g. most calanoid copepods, to specific level and even developmental stage (e.g. Batten et al., Reference Batten, Welch and Jonas2003; Batten & Welch, Reference Batten and Welch2004). However, many groups including the decapod Crustacea are identified only to higher taxonomic levels. Analyses of the decapods in CPR samples to finer taxonomic resolution (species level where possible) have been carried out for the survey of the North Sea only by Rees (Reference Rees1952, Reference Rees1955) and Lindley et al. (Reference Lindley, Williams and Hunt1993) and for the north-east Atlantic and North Sea by Lindley (Reference Lindley1987). There are descriptions of larvae of most of the species occurring in these areas but in the north-eastern Pacific a much smaller proportion are described. Puls (Reference Puls and Shanks2001) lists 170 species from southern Alaska to northern California but provides descriptions or references for the identification of only about one-third of them. Re-examination of the CPR samples in which Decapoda were recorded has inevitably provided material of un-described or incompletely described larvae. Although the specimens are damaged by the sampling mechanism (Batten et al., Reference Batten, Welch and Jonas2003) and are not suitable for comprehensive morphological descriptions, some characteristics of previously un-described larvae have been recorded which will be of use to researchers in the future.

The distributions and seasonal cycles of the Decapoda in the Pacific CPR survey are described here. The results are examined to determine whether the occurrence of meroplankton derived from neritic populations in offshore locations, in combination with other components of the plankton, can provide useful information on transport in the anticyclonic eddies originating in the archipelagos off British Columbia and Alaska.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

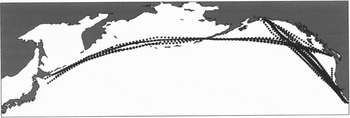

The CPR and methods of collection and analysis of the samples are described by Batten et al. (Reference Batten, Welch and Jonas2003). Sampling in the Pacific started with trial tows between California and Alaska (AC route) in July–August 1997. Regular sampling started in 2000 with tows on the AC route in March and each month from May to August and a tow in late June to early July from Vancouver to Japan (VJ route). Figure 1 shows the distribution of processed samples. Table 1 gives the numbers of samples and decapods identified by calendar month. Sampling was most intensive in June but sparse from November to March. The samples and specimens are held in the CPR sample archive at Plymouth, UK.

Fig. 1. Positions of all processed samples collected between 2000 and 2003.

Table 1. Continuous Plankton Recorder sampling in the North Pacific. Monthly numbers of samples and number of decapods recorded.

The samples in which Decapoda had been recorded were re-examined at the SAHFOS laboratory in Plymouth. Decapods were extracted and examined under stereomicroscopes. These were identified to the finest practicable taxonomic level and development stage. Where possible carapace length with and without the rostrum, total length, in the case of Brachyura length from the tip of the rostrum to the tip of the dorsal spine and in some cases individual spine lengths were measured using an ocular micrometer. The measurements were to a resolution of 0.1 mm as more precise measurements could be spurious because of distortion of the specimens.

Photomicrographs of specimens were taken with a Nikon Coolpix digital camera through CPR traversing microscopes (Watson Bactil or Micro-Instruments custom-built microscope) or a Wild M5 stereomicroscope.

Identification of larvae was by reference to Puls (Reference Puls and Shanks2001) and references therein and other works, particularly Gurney & Lebour (Reference Gurney and Lebour1940); Kurata (1963); Bousquette (Reference Bousquette1980); Haynes (Reference Haynes1980, Reference Haynes1984, Reference Haynes1993); Knight & Omori (Reference Knight and Omori1982); and Saski & Mihara (Reference Sasaki and Mihara1993). Although many larvae could not be referred to species on the basis of published descriptions, it was possible to refer some previously un-described larvae to species on the basis of descriptions of congeneric species and the known species distributions. These are listed and brief descriptions are given below with some notes on morphological variation of a zoea from the existing description. The developmental stages of some, but not all, Cancer species from the area have been described. However, due to the similarity of the larvae, and the absence of some descriptions, the larvae are described here as Cancer spp. but additional information is given for a few specimens referred with certainty to C. magister Dana, 1852 and C. productus Randall, 1840. Most specimens of Chionoecetes were tentatively referred to C. bairdii Rathbun, 1893 or C. opilio (O. Fabricius, 1780) on the basis of descriptions by Wencker et al. (Reference Wencker, Incze, Armstrong and Maltell1982). There is the possibility of the presence of C. angulatus Rathbun, 1893, C. japonicus Rathbun, 1932 and C. tanneri Rathbun, 1893 and hybrids can occur (e.g. Johnson, Reference Johnson1976), so all are reported as Chionoecetes spp. in this paper. Zoeas of the pinnotherid brachyuran Pinnixa spp. were distinguished from the similar stages of Fabia subquadrata Dana, 1851 according to the criteria of Bousquette (1960). Hsueh (Reference Hseuh1991) was able to identify four types of Pinnixa larvae and refer two of these to P. franciscana Rathbun, 1918 and P. weymouthi Rathbun, 1918. The specimens and records of observations were subsequently lost in an earthquake (Hseuh, P.-W., personal communication) so the criteria for distinguishing these types are not known.

RESULTS

Identification of un-described larvae

Petalidium suspiriosum Burkenroad, 1937

Only one species of Petalidium, P. suspiriosum (Dendrobranchiata: Sergestidae) is recorded from this part of the Pacific Ocean according to Pérez-Farfante & Kensley (Reference Pérez-Farfante and Kensley1997).

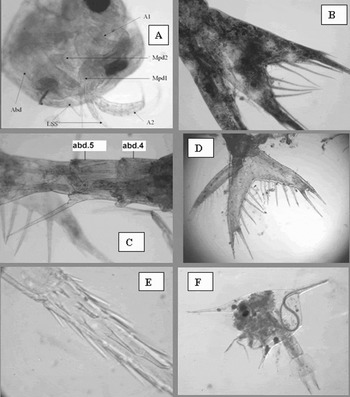

A protozoea Stage I was taken in sample 93AC 9 (38°30′N 124°21′W, 8 September 2003). The specimen is very similar, except for slightly smaller size, to the same stage of the southern hemisphere species P. foliaceum Bate, 1881 described by Vera & Bacardit (Reference Vera and Bacardit1987). The carapace length is 1.1 mm (cf. 1.3 mm) and total length 1.5 mm (cf. 1.7 mm). Gurney (Reference Gurney1924) described specimens that he attributed to P. foliaceum but his ‘Stage I’ was 2.7 mm in length and the eyes were free in contrast with the sessile eyes of the present specimen and the protozoea I of Vera & Bacardit. The body of the present specimen is curled around so that the pleon is completely covered by the carapace (Figure 2A) as described by Gurney (Reference Gurney1924).

A zoea Stage I (ZI) occurred in sample 1AC 9 (40°53′N 127°08′W, 22 August 1997). This was similar to Petalidium foliaceum ‘Stage IV’ of Gurney (Reference Gurney1924) (his first three stages are the protozoea stages). The carapace length of the current specimen was 2.0 mm including rostrum, 1.8 mm excluding rostrum and total length 5.3 mm. This compares with a length of 6.8 mm given by Gurney but he does refer to a specimen of 5.8 mm. The present specimen has a strong median dorsal spine on pleon somite 6, and a smaller spine on somite 5. Due to damage at the junction of somites 4 and 5 it was not possible to comment on the presence or absence of a spine on somite 4. The endopodite of P3 is large, as described for P. foliaceum by Gurney (Reference Gurney1924).

Munida spp. zoeas

Two types of Munida (Anomura: Galatheidae) zoea were recorded, separable from each other on the basis of size, characteristics of the telson and the number of dorsal denticles and length of posterolateral processes on the pleon somites. One specimen of each zoeal stage of the smaller type was taken in the area around 50°N and one of each of Stages ZII and ZIII of the larger form from near 38°40′N. Puls (Reference Puls and Shanks2001) lists two species from the north-west Pacific, Munida quadrispina Benedict 1902 and Munida hispida Benedict 1902. According to Wicksten (Reference Wicksten1989) the distribution of the former is from Alaska to Baja California, Mexico and the latter ranges from Monterey Bay, California to the Galapagos. The type of zoea with the more northern distribution is most likely to be M. quadrispina and specimens from further south are probably M. hispida.

An example of each zoeal stage of Munida quadrispina (?) was identified.

Zoea I (sample 1VJ 15, 50°11.6′N 130°1.7′W, June 2000). The carapace length (excluding rostrum) was 0.8 mm. The pleon was missing.

Zoea II (sample 53AC15, 49°39.1′N 127°56.1′W, June 2002). The carapace length was 1.7 mm (0.9 mm without rostrum), and the total length (tip of rostrum to tip of telson fork) 3.5 mm. Posterolateral processes on pleon somite 4 were <1/4 somite 5, on those on somite 5 <1/2 somite 6. Two pairs of robust dorsal denticles were present on pleon somites 2–5. There were six spines between outer telson forks; outside these was one small lateral spine.

Zoea III (sample 1VJ 19, 50°29.6′N 130°57.5′W, June 2000). Carapace length was 2.2 mm (0.9 mm without rostrum) and total length 4.3 mm. There were two pairs of robust dorsal denticles on pleon somites 2–5, the mid-pair distinctly more robust than the outer pair. Posterolateral processes on pleon somite 4 were <1/3 somite 5, on somite 5 <1/2 somite 6. Somite 6 had a strong mid-dorsal spine. The telson had four pairs of spines between longest with two lateral pairs of spines plus a seta outside these.

Zoea IV (sample 53AC19, 50°4.5′N, 128°53.8′W, June 2002). The carapace length was 3.3 mm (1.7 mm without rostrum) and total length 6.0 mm. Posterolateral processes on pleon somite 4 were <1/5 somite 5, those on somite 5 <1/4 somite 6. Two pairs of robust dorsal denticles were present on somites 2–5. Somite 6 had a median dorsal spine. There were four spines and one seta between longest telson spines and two lateral spines plus one seta outside these (Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. (A) Petalidium suspiriosum protozoea I. Carapace length 1.1 mm. A1, first antenna; A2, second antenna; Mpd1, first maxilliped; Mpd2, second maxilliped; abd, abdomen (pleon); LSS, large spinous seta; (B) Munida quadrispina (?) ZIV telson (total length of specimen 6.0 mm); (C) Munida hispida (?) ZII (total length 5.0 mm); pleon somites 4 and 5 (abd 4 and 5) showing posterolateral spines (that on abd 4 is bent beneath abd 5); (D) Munida hispida ZIII (total length 5.7 mm), telson; (E) Pleuroncodes planipes ZV, junction between unornamented part of rostrum and spinose distal zone. Image width 200 µm; and (F) Pinnixa sp. ZIV (carapace length 2.0 mm) from Continuous Plankton Recorder sample 53AC3 containing parasitic nematode.

Only two specimens of Munida hispida (?) were taken, a ZII and a ZIII.

Zoea II (sample 81AC 5, 33°41.4′N 119°52.5′W, May 2003). The total length was estimated as 5.0 mm. The posterolateral processes on pleon somite 4 were ~1/2 somite 5 and those on somite 5 were longer than the somite, all were sparsely denticulate (Figure 2C). There were four small dorsal denticles on the posterior margins of pleon somites 3 and 4, six on somite 5. There were six spines between telson forks.

Zoea III (sample 27AC1, 33°38.6′N 118°45.3′N, August 2000). The carapace length was 3.0 mm (without rostrum 1.9 mm) and total length 5.7 mm. The proximal half of rostrum was strongly denticulate but on the distal part denticles were barely visible. Posterolateral processes on pleon somite 4 were <1/2 somite length, those on somite 5 approximately equal to the somite length, both pairs were sparsely denticulate. There were four small dorsal denticles on the posterior margin of somite 4 (the margin of somite 3 was obscured by damage) and numerous (>10) denticles on the posterior margin of somite 5. There were 6 + 5 spines between longest telson spines and the outermost lateral spine was almost as long as the longest with a spine and a seta in between (Figure 2D).

Pleuroncodes planipes Stimpson 1860

Boyd (Reference Boyd1960) described the larval stages of Pleuroncodes planipes (Anomura: Galatheidae) but a ZV taken in sample 17AC13 (36°24.5′N 123°05′W) differed from his description of the same stage. The carapace length was 5.1 mm (2.8 mm excluding rostrum) and the total length was 10.8 mm (cf. 7.2–7.8 mm). The rostrum had lateral denticulations for >1/2 length at proximal end, a short section was unornamented, then the distal part had denticulations over the whole circumference in a zone clearly delimited by a slight constriction (Figure 2E). Distal ornamentation is shown in Boyd's figures of ZI–ZIII but not in ZIV and ZV. The posterolateral processes on pleon somites 4 and 5 are longer than those shown by Boyd, the spine on somite 4 >1/3 somite 5, that on somite 5 1/3 > 1/2 somite 6. The dorsal spine on the last somite is longer than shown by Boyd.

Scyra acutifrons Dana, 1851

Both zoeal Stages (I and II) and the megalopa of larvae similar to those of S. compressipes Stimpson, 1857 (Brachyura: Majidae) described by Kim & Hong (Reference Kim and Hong1999) were found in the Gulf of Alaska and the Unimak Island area. As S. compressipes is not known from the eastern North Pacific, these were referred to S. acutifrons which is widespread from Alaska to California (Garth, Reference Garth1958). The present larvae differed in size from the laboratory-reared specimens of Kim & Hong (Reference Kim and Hong1999), the values given in parentheses below refer to their results.

Zoea I (samples 3VJ45, 54°24.4′N 165°4.5′W, June 2000; 10VJ7, 48°38.3′N 125°18.7′W, June 2001); 45VJ7, 54°23.4′N 166°32.0′W, June 2003). The carapace lengths were 0.8–1.0 mm (cf. 0.7 mm) and from tip of the rostrum to tip of dorsal spine (T–T) 1.3–1.7 mm (cf. 1.3 mm). Rostral spine measured 0.32 mm (cf. 0.39 mm) and the dorsal spine 0.83 mm (cf. 0.56 mm).

Zoea II (samples 10VJ3, 54°17.6′N 165°52.1′W, June 2001; 51AC13, 33°55.9′N 120°41.4′W, May 2002; 45VJ7—see above), the carapace lengths were 0.9–1.1 mm (cf. 0.8 mm), T–T 2.2–2.9 mm (cf. 1.4 mm).

Megalopa (sample 10VJ3, see above). The carapace length was 1.5 mm and total length 2.9 mm (cf. 1.04 mm, 1.9 mm respectively).

Species distributions and seasonal cycles

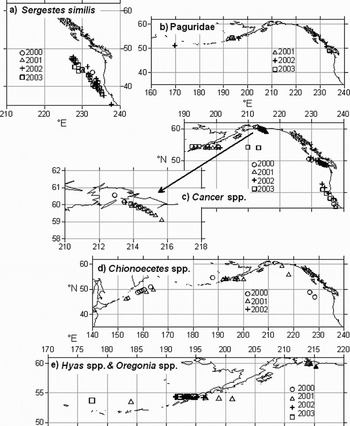

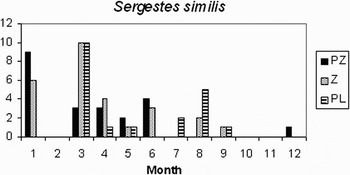

In Table 2 the taxa identified in this study are listed. The month and coordinates of records of those which were taken from a few samples are given in the Table, but the geographical distributions of six more abundant taxa are shown in Figure 3 and the seasonal cycles of records of Sergestes similis and Cancer spp. are shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively.

Fig. 3. Distributions of Decapoda in CPR samples from the North Pacific Ocean, 1997 and 2000–2003. (A) Sergestes similes; (B) Paguridae; (C) Cancer spp.; (D) Chionoecetes spp.; and (E) Hyas spp. (open symbols) and Oregonia spp. larvae (filled symbols). Longitudes >180°E represent [180- (n-180)]°W.

Fig. 4. Sergestes similis numbers of protozoea (PZ), zoea (Z) and post larval stages in each calendar month.

Fig. 5. Cancer spp. Relative abundance (%) of five zoeal stages and megalopa stages in each calendar month in four areas of the Pacific CPR survey.

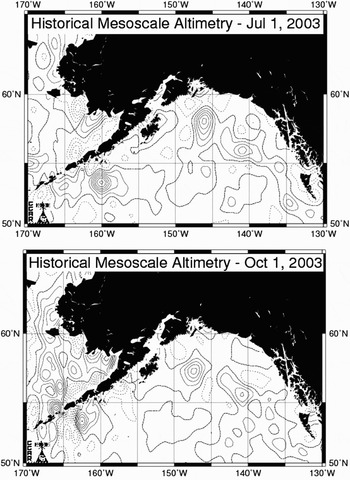

Fig. 6. Sea surface height anomalies (Colorado Centre for Astrodynamics Research) in the Gulf of Alaska on 1 June and 1 October 2003.

Table 2. Decapoda taken in the Continuous Plankton Recorder, 1997 and 2000–2003. Identity and date and location of records. Details of distributions of abundant taxa are shown in Figure 3 and seasonal cycles of Sergestes similis and Cancer spp. are shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Sergestes similis was the most widespread and abundant oceanic species (Figure 3A). Protozoea, zoea and mastigopus (decapodid) stages occurred on the AC routes south of 52°N in most months of the year. However, the frequency of occurrence of the different stages (Figure 4) indicated that reproduction occurred mainly in the period December to June. Petalidium suspiriosum was the only other sergestid in the samples.

Few caridean larvae were taken in the samples. The most frequently recorded species was Paracrangon echinata.

Paguridae were recorded in 11 samples, the locations of which are shown in Figure 3B. Four species were identified and the details of these records are given in Table 2. All the records were in June except for the most westerly record which was in October 2002 (Table 2).

The most abundant decapod larvae in the samples were those of the genus Cancer which occurred in 56 samples and accounted for 48% of the decapods taken. The distribution of these is shown in Figure 3C and the percentage of each development stage found in the samples, in each month, in each of four areas is shown in Figure 5. The records were from March to October. The two March records were from the area south of 41°N in 2000 and 2003 and there were further records from this area in April 2002, June 2000, and in August 2001 and 2003. There was one record between 41° and 45°N in April 2002 and this is grouped with those from 41°N in Figure 5. There was no obvious seasonal pattern to the frequency of developmental stages. In the region between 45° and 50°N, off the Juan de Fuca Straits and Vancouver Island, Cancer zoeas were recorded in June of each year from 2000 to 2003 and in April 2003. The specimens identified as C. magister and C. productus were recorded in this area (Table 2). There is some evidence in the stage frequency that there was a shift towards later developmental stages in June. Cancer larvae were found in the area around the Unimak Passage where the VJ route passes through the Aleutians in June 2001 and 2003, and October 2002. There were two records of Cancer from the VJ route in the central Gulf of Alaska (54°4.0′N 146°43.2′W and 54°11.4′N 150°6.8′W) in September 2003 and these are plotted in Figure 5 with the Aleutian records, as they are at similar latitudes. Zoea Stages I–V were present in June, with the early stages dominant, but in September and October only megalopas were recorded, indicating a principal period of spawning in late spring/early summer. In Alaskan waters there were records from June 2001, July 2000 and 2002 and August 2000. Early zoeas were more numerous in June than in July when ZIV and ZV stages were dominant and only the megalopa stage was recorded in August. These results indicate a short breeding season in these waters. The megalopas found in the central Gulf of Alaska in September 2003 may indicate the water originating on the shelf. There were no other examples of meroplankton evident in the samples but Pseudocalanus spp. occurred in the samples on that route only between 54°5.1′N 147°51.0′W and the more westerly of the two samples in which Cancer was recorded (54°11′N 150°07′W). Mackas & Galbraith (Reference Mackas and Galbraith2002) found that P. mimus Frost, 1989, were more abundant in an eddy containing water of shelf origin than in non-eddy water in the Gulf.

The commercially exploited Chionoecetes spp. (snow crabs and tanner crabs) also occurred regularly in the samples. Their distribution is shown in Figure 3D. All records were in June except for 45 specimens taken between 48°0.5′N 156°1.26′E and 50°58.3′N 163°1.2′E in early July 2000. These were among the most westerly records of these larvae in the CPR samples. The records most distant from the shelf edge at 46°56′N 131°37′W and 48°50′N 133°38′W, in June 2000 and 56°2.6′N 142°2.2′W in June 2001 could be interpreted as an indication of shelf water in the open ocean. However, there were no other typically neritic components of the plankton recorded in these samples. Other Oregoninae in the samples were Hyas spp., mainly H. lyratus Dana, 1851 and Oregonia spp. The distribution of these is shown in Figure 3E & F. All records were in June except for one occurrence of Hyas lyratus in May in Alaskan waters.

Most of the records of other Brachyura were in June or July except for H. oregonensis which was taken in October 2002 and an unidentified Pisinae found in a sample from April 2002.

One ZIV of 12 Pinnixa zoeas taken in June 2002 at 48°34′N 125°25.4′W contained a nematode (Figure 2F), the only record of a metazoan parasite in the material studied here.

DISCUSSION

According to Williamson (Reference Williamson and Bliss1982) there are three protozoea (elaphocaris) stages and two zoea (acanthosoma) stages in the development of the Sergestidae. If the Petalidium foliaceum ‘Stage I’ of Gurney (Reference Gurney1924) is actually the protozoea II, as indicated by the comparison with the descriptions by Vera & Baccardit (1987) and the specimen described here, then there are four protozoea stages. It is possible that Gurney's specimens were not the same species as those of Vera & Baccardit but there is no obvious alternative from species distributions given in Pérez-Farfante & Kensley (Reference Pérez-Farfante and Kensley1997). The Stage V of Gurney (Reference Gurney1924) has setose pleopods and therefore must be regarded as a decapodid (postlarva or mastigopus) in which case the ZI is the only true zoea stage in contrast with two stages in Sergestes.

The interpretation of the results of the first few years of the CPR survey in the North Pacific must take into account the seasonal variations in sampling intensity. In particular, the VJ route was towed only once in June to early July in 2000 and 2001 and the sampling in the following two years included tows in June. The numbers of decapod larvae taken in June (Table 1) represent nearly 1 per sample, more than in any other month. In 2002 and 2003 relatively small numbers of larvae were taken in April and September/October and a restricted seasonal cycle in Alaskan waters (AC route) is consistent with a ‘short burst’ of decapod larva production in Aleutian and Alaskan waters.

Sergestes similis is known from further north than the records presented here (http://www.iobis.org/; Pérez-Farfante & Kensley, Reference Pérez-Farfante and Kensley1997). However, the geographical distribution of records here may indicate the usual northern limits of spawning in the eastern North Pacific in which case the more northerly occurrences are of expatriates which have migrated or been advected outside the breeding range. The seasonal cycle indicates an early start to the breeding season, with protozoeas in December and January, in contrast with the close sibling S. arcticus in the north-east Atlantic where Lindley (Reference Lindley1987) found no larvae until February and zoeas were absent after July.

Meroplanktonic species were particularly abundant off Juan de Fuca, in Prince William Sound and around the Unimak Passage but less abundant further west where the VJ route passed though the Aleutians at about 170°E. The large area of continental shelf off the Alaskan Peninsula and the eastern Aleutians, in contrast with the restricted band of shallow water on the line of the archipelago further west may be the reason for this difference. In these northern waters there was a short early summer peak of abundance of decapod larvae which contrasts with the late summer peak in the North Sea (Rees, Reference Rees1952; Lindley, Reference Lindley1987). It also contrasts with the longer productive season further south, off California. In this area there are several Cancer spp. with differing seasonal cycles of larval production. One of the most abundant species is C. gracilis Dana, 1852, larvae of which occur throughout the year in the area (http://www.swrcb.ca.gov/rwqcb3/Facilities/DukeEnergy/CancerCrabs.pdf). The restricted larval period for the Oregoninae are interesting in comparison with the short larval period for Hyas spp. in the north-east Atlantic (Rees, Reference Rees1952, Reference Rees1955; Lindley, Reference Lindley1987; Lindley et al., Reference Lindley, Williams and Hunt1993; Martin, Reference Martin2001). There are diapause or diapause-like periods in the embryonic development of Hyas spp. and Chionoecetes opilio (Wear, Reference Wear1974; Moriyasu & Lanteigne, Reference Moriyasu and Lanteigne1998) which may co-ordinate the time of hatching with a short season of planktonic food production in high latitudes (Petersen & Anger, Reference Petersen and Anger1997). It may be that this is a feature of all the Oregoninae.

The records of Cancer spp. in the central Gulf of Alaska together with the presence of Pseudocalanus in the same area may indicate the influence of water originating on the continental shelf. However, there was no sea surface height (SSH) anomaly in the area at the time so the samples were not in an existing eddy but this does not preclude the possibility of transport from the shelf in an eddy. At 10°C, the sea surface temperature in the area in early summer, (http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/sci/osap/data/sstarchive_e.htm), the duration of the zoeal stages of Cancer magister is 69.7 days (Sulkin & McKeen, Reference Sulkin and McKeen1989), and that of Cancer irroratus Say, 1817 (a West Atlantic species) is 62.2 days (Sastry, 1976). The duration of the megalopal stage at this temperature according to Sastry was 42.1 days so the megalopas found in the plankton would have been in the plankton for at least two months and possibly over three months. The SSH anomalies for 1 July 2003 (three months prior to the sample collection) show two eddies close to the Alaskan shelf; one east of the Aleutian Islands and one south of Prince William Sound (PWS) (Figure 6). Sea surface height anomalies were extracted from an Internet site of the Colorado Center for Astrodynamics Research at the University of Colorado, Boulder (CCAR, R. Leben, personal communication, 2002). Okkonen et al. (Reference Okkonen, Weingartner, Danielson, Musgrave and Schmidt2003) show a wide swirl of high chlorophyll water around the outer edge of an eddy in the western Gulf of Alaska in 2000 (their figure 1) as do Crawford et al. (Reference Crawford, Brickley, Peterson and Thomas2005) for eddies in the eastern Gulf of Alaska suggesting that shelf water was entrained and swirled around the outer edges. It is possible that the larvae were entrained in an eddy while it was close to the shelf, subsequently swirled around the outer rim and carried offshore. The larvae would at some point leave the eddy through its decay process, possibly enhanced by vertical migration, and would then be subjected to the surface currents. Given that the 1 October SSH anomaly map (Figure 6) shows the PWS eddy to have moved south and slightly west this is the more likely candidate for the origin of the Cancer larvae. The location of the samples containing the larvae from 1 October is not near to an eddy, however, we do not know how currents and the organism's behaviour may have influenced their drift if they left the eddy some weeks earlier. The records are close to the Patton Seamount but there are no records in OBIS (http://www.iobis.org/) of Cancer spp. in seamounts in the area and Hoff & Stevens (Reference Hoff and Stevens2005) did not mention the genus in the results of their survey of the seamount. Whatever their origin, the only locations where the megalopas could settle and continue development at the young crab stage in suitable depths for further development would be on a seamount.

The records of Chionoecetes most distant from the shelf could potentially indicate water of neritic origin. Typically neritic components of the plankton were absent from these samples and C. angulatus and C. tanneri are known from depths as great as 3330 m and 1944 m respectively (Wicksten, Reference Wicksten1989). It is possible that these records were of these deep-water species rather than the more typically neritic C. bairdi or C. opilio. The specific identity of these larvae and of the Cancer spp. could be determined by molecular methods. Although formalin fixation has been thought to preclude DNA analysis, this has been achieved for CPR material (Kirby & Reid, Reference Kirby and Reid2001; Kirby & Lindley, Reference Kirby and Lindley2005; Kirby et al., Reference Kirby, Johns and Lindley2006).

The presence of a nematode parasite in a Pinnixa sp. zoea is notable as there is little information on such parasites in decapod larval stages. Lindley (Reference Lindley1992) recorded a nematode infecting a zoea of the porcellanid Pisidia longicornis. In Figure 2F it can be seen that the nematode in Pinnixa was blocking the dorsal spine just as Lindley (Reference Lindley1992) described the tail of the nematode blocking one of the posterior carapace spines of Pisidia. Pinnixa spp. are symbionts of other invertebrates (Zmarzly, Reference Zmarzley1992) which may be the host to other stages in the parasite's life cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the North Pacific Research Board (projects R0302, and 536) and the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council (projects 020624, 030624 and 040624). We are grateful to the officers and crews of the ‘Polar Alaska’ and the ‘Skaubryn’ and to Polar and Seaboard International for their voluntary participation in the CPR survey. This is NPRB paper 112.