INTRODUCTION

Biological responses to Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are highly variable among fish taxa (Claudet et al., Reference Claudet, Pelletier, Jouvenel, Bachet and Galzin2006) but, in general, species targeted by exploitation benefit more than non-targeted species (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Mosqueira and Reynolds2001), even for recreationally fished species (Westera et al., Reference Westera, Lavery and Hyndes2003). Reserve establishment has benefited these species through increases in mean sizes and abundance (Harmelin, Reference Harmelin1987; García-Rubiés & Zabala, Reference García-Rubiés and Zabala1990; Roberts & Polunin, Reference Roberts and Polunin1991; Francour, Reference Francour1994; Bohnsack, Reference Bohnsack1998; Reñones et al., Reference Reñones, Goñi, Pozo, Deudero and Moranta1999; Macpherson et al., Reference Macpherson, Gordoa and García-Rubiés2002), whereas most non-target species appear to either show no response to protection (Rakitin & Kramer, Reference Rakitin and Kramer1996) or respond negatively with reduced abundances (McClanahan et al., Reference McClanahan, Muthiga, Kamukuru, Machano and Kimbo1999). Moreover, the establishment of MPAs might eventually cause ecosystem-wide effects (Sala et al., Reference Sala, Ribes, Hereu, Zabala, Alvà, Coma and Garrabou1998; Guidetti, Reference Guidetti2006). In the Caribbean, Mumby et al. (Reference Mumby, Dahlgren, Harborne, Kappel, Micheli, Brumbaugh, Holmes, Mendes, Broad, Sanchirico, Buch, Box, Stoffle and Gill2006) and Hoegh-Guldberg (Reference Hoegh-Guldberg2006) have shown that protecting large parrotfish (Scarus spp. and Sparisoma spp.) with MPAs resulted in a greater biomass of these species in these areas. This enhancement was associated with a net doubling of grazing on seaweed and, consequently, promoting coral reef resilience and recovery.

In the north-western Mediterranean Sea, during the last decade, an important number of marine reserves were established in order to protect the Mediterranean endemic seagrass, Posidonia oceanica. This seagrass is steadily declining due to increasing human activities along this coast (Duarte, Reference Duarte2002). It remains unknown how protection might alter certain ecosystem processes such as herbivory. In the Mediterranean Sea, the herbivorous fish Sarpa salpa (Linnaeus) plays a key ecological role as the primary vertebrate grazer of P. oceanica, consuming in some meadows more than half of the primary production (Alcoverro et al., Reference Alcoverro, Duarte and Romero1997; Tomas et al., Reference Tomas, Turon and Romero2005; Prado et al., Reference Prado, Tomas, Alcoverro and Romero2007). The species forms crowded schools with several hundred individuals (Weingberg, Reference Weinberg1992) of relatively homogeneous size (Verlaque, Reference Verlaque1990) in shallow waters, rocky bottoms or seagrass beds. Schools of S. salpa usually feed together over the phytobenthos with repetitive bites focused on a small area (Verlaque, Reference Verlaque1990) causing intense grazing (Laborel-Deguen & Laborel, Reference Laborel-Deguen and Laborel1977; Tomas et al., Reference Tomas, Turon and Romero2005). MPAs alleviate the fishing pressure on S. salpa, which is primarily caused by amateur spearfishermen and, occasionally, by professional fishermen (personal observation). As a result of this protection, the resulting increases in S. salpa populations can substantially modify herbivory pressure in these seagrass meadows. In order to test this end, we compared population parameters, feeding behaviour and grazing rates of S. salpa in nine seagrass meadows (three inside an MPA and six outside) with similar habitat characteristics. All three protected meadows have greatly reduced fishing pressure: spearfishing is permitted in none of the three MPAs and only in one is recreational angling allowed; the number of S. salpa captured is extremely low. The six unprotected meadows are sites where tourism (yachting, anchoring, and spearfishing) and fishing pressure is high due to the proximity of large urban centres.

More specifically, the present paper aims: (1) to assess whether alleviated fishing pressure inside protected P. oceanica meadows creates differences in population parameters (e.g. size of schools, length and biomass of the individuals) of S. salpa; and (2) to compare the herbivory pressure (seagrass surface grazed by S. salpa) among protected and unprotected meadows.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

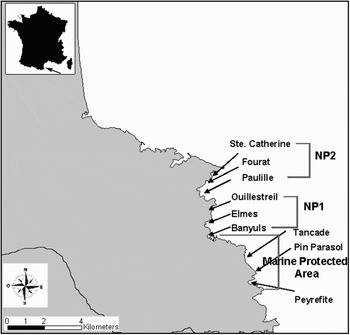

Differences in population parameters and behaviour of S. salpa were quantified during the summer of 2003 along the Albères coast at 9 seagrass meadows (north-western Mediterranean Sea; Figure 1). Total linear distance between all meadows was less than 25 km. Three meadows were located inside the Marine Natural Reserve of Cerbère and Banyuls, a MPA established more than 20 years ago in 1985 and the other six meadows were located in non-protected areas. Previous to site selection, several dives were performed along different areas in order to select meadows presenting similar characteristics, with a comparable coverage. They present similar environmental and physical features and are situated at a sufficient distance from the protected areas in order to ensure no migration of fish among them.

Fig. 1. Simplified nautical chart of Posidonia oceanica seagrass meadows from the Albères coast. The Marine Natural Reserve of Cerbère and Banyuls is placed between L'IIle Grosse and the Cap Peyrefitte, spread over 650 ha with a total shore distance of 6.5 km.

Data collection

At each meadow, 3 random sites were selected and the total area of each was surveyed and videoed 7 times by SCUBA diving. Direct estimations of measured variables and 378 films recorded between 3 and 12 m depth were obtained: 189 general and 189 specialist; the general and specialist films were 10 and 5 minutes in length respectively. General images were used to support data on the number of fish and their size, whereas the specialist images were used to evaluate fish behaviour. This method was considered to be the most appropriate because S. salpa commonly forms large schools of 500–1000 individuals (Faggianelli & Cook, Reference Faggianelli and Cook1981). The estimation of the number of fish in such a school is difficult to evaluate. The human eye is unable to immediately count clusters of more than four objects (Ifrah, Reference Ifrah1994), and above 50 fish errors become significant and the number is usually underestimated (Harmelin-Vivien et al., Reference Harmelin-Vivien, Harmelin, Chauvet, Duval, Galzin, Lejeune, Barnabé, Blanc, Chevalier, Duclerc and Lasserre1985). Overall, the data provided a relative measure that can be used to compare parameters between areas.

The number of fish per minute was estimated across the whole site (meadow) from both direct surveillance (visual census) and with the aid of the 21 generalist films in order to improve the accuracy of fish abundance estimates. The length of the film (10 minutes) gives a relative measure of the number of fish observed per minute at each site. Fish size was estimated directly to the nearest cm with the aid of a graded plate (2 cm × 2 cm) following a similar methodology as that described by Mantyka & Bellwood (Reference Mantyka and Bellwood2007). In order to minimize errors in fish size and number estimations, the graded plate and the fish were filmed at the same time to confirm the data estimated from direct surveys. Data on abundance and fish size were averaged at each site for each of the 21 recorded films.

Total fish biomass at each meadow was derived from abundance and fish size data following a weight–length relationship obtained from commercial fisheries in the area (weight = 0.034; size = 2.73; R2 = 0.9).

Data on behaviour were quantified from the 189 specialist films. The percentage of time devoted to each activity: eating algae, eating P. oceanica, and time spent in the water column was quantified. During the filming, the diver focused first on one randomly selected fish for as long as it remained in view, then a second randomly selected fish was substituted for this first one, and so on. These results were formulated as a percentage of the sum of the three activities equal to 100%. These 5 minute long films also provided an estimate of the number of bites per minute per individual. We obtained an average value for the variables measured for each of the 21 films recorded per meadow.

In order to calculate the mean surface eaten per S. salpa and per bite, mouth surface area was regressed on total fish length for individuals obtained from markets. Although the surface area removed per bite is likely to be slightly smaller than total mouth area, this measure is still a good indicator of the amount of seagrass eaten.

Statistical analyses

Univariate data were analysed using asymmetrical analysis of variance (ANOVA). The model consisted of 3 factors: protection (fixed, with 1 protected and 2 unprotected locations); meadow (3 levels, random and nested in location); and site (3 levels, random and nested in meadow nested in location), with N = 21 observations per combination of factor levels. As the number of protected meadows is less than the number of perturbed meadows, this is an asymmetrical design (Glasby, Reference Glasby1997; Underwood, Reference Underwood1997). First, the data from all the 3 locations were analysed using a fully orthogonal design, then a second analysis was carried out on only those data associated with the non-protected locations. The asymmetrical components were thus calculated by subtracting the sums of squares of the second analysis from those of the first.

The homogeneity of variances was tested using a Cochran's test and, whenever necessary, data were transformed. If transformations did not produce homogeneous variances, ANOVA was nevertheless used after setting α = 0.01 in order to compensate for the increased likelihood of Type I error (Underwood, Reference Underwood1997).

RESULTS

Differences in population parameters

Asymmetrical ANOVAs detected significant differences in the mean number of fish (occurring per minute of video recording) among protected and unprotected areas (P < 0.01). Mean number of fish was higher in the protected meadows than in the unprotected ones: 35±1.9 fish per minute versus 3±0.2 fish per minute (Table 1; Figure 2A).

Fig. 2. Characteristics of Sarpa salpa (A) mean number of individuals per minute; (B) mean length (cm); (C) mean biomass (kg). Error bars represent standard errors. Box represents protected sites. Data obtained from 21 generalist films at each meadow.

Table 1. Summary of asymmetrical ANOVA testing differences among Sarpa salpa populations between protected and control areas. Only tests relevant to our hypothesis are reported. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Moreover, asymmetrical ANOVAs also detected significant differences in the mean size of fish among protected and unprotected areas (P < 0.01). Mean size was higher in the protected meadows than in the unprotected ones: 40±0.7 cm versus 23±0.9 cm (Table 1; Figure 2B). As fish were more abundant and larger in protected areas, fish biomass was higher in the protected meadows than in the unprotected ones (Table 1; Figure 2C). Results from asymmetrical ANOVAs provide significant differences among these data (P < 0.01).

Differences in population behaviour

Asymmetrical ANOVAs detected significant differences in fish behaviour among protected and unprotected areas (P < 0.01). Time devoted to grazing P. oceanica is highest inside the preserved areas whereas it is lowest in the unprotected meadows. In contrast, fish devote none of their time to grazing algae at any of the 3 meadows inside the protected areas. Similarly, time spent in the column of water is higher at unprotected locations compared to protected ones (Figure 3; Table 1).

Fig. 3. Mean percentages of time devoted to grazing on algae (black), grazing on Posidonia oceanica (shaded) and swimming (white). Box represents protected sites. Data obtained from 21 specific films at each meadow.

The number of bites on P. oceanica observed per minute is higher in unprotected locations, with a mean of 16.4±0.5 bites per minute in comparison with a mean of 12.1±0.5 bites per minute inside the protected meadows (P < 0.01; Figure 4A; Table 1). However, the total surface eaten with each bite is higher in protected locations (P < 0.01) with values of 28.2 cm2/minute in comparison to a mean of 14.2 cm2/minute in unprotected locations (Figure 4B). This apparent incongruence resulted from the relationship between total fish length and mouth surface area (Figure 5)

Fig. 4. Feeding behaviour (A) mean number of bites per minute; (B) mean leaf surface area removed per fish (Sarpa salpa) during one minute. Error bars represent standard errors. Data obtained from 21 specific films at each meadow.

Fig. 5. Linear regression between total length of fish and maximal Posidonia oceanica leaf surface removed per bite (cm2) (y = 0.08 x−0.97; R2 = 0.98).

DISCUSSION

We found significant differences in S. salpa population parameters as well as their feeding behaviour between protected and unprotected areas. Inside protected locations, the total number of fish, their length and biomass is higher than outside and the time devoted to grazing on P. oceanica is longer. Moreover, no algae is eaten inside protected locations and time spent in the column of water after human disturbance is shorter.

The higher number of S. salpa found inside protected locations contradict somewhat previous results. In an extensive review of data from Mediterranean reserves, Guidetti & Sala (Reference Guidetti and Sala2007) have found that. S. sarpa did not respond significantly to protection. However, it should be noted that most of their data on fish densities were obtained in zones with predominantly rocky habitats, which is not the preferential habitat for the herbivorous fish S. sarpa. In our study, we compare abundances of individuals only among Posidonia meadows, and in this case, our results are in accordance with the previous general finding that overall relative abundance of fish species tend to increase when some kind of protection measure is enforced (Harmelin, Reference Harmelin1987; García Rubiés & Zabala, Reference García-Rubiés and Zabala1990; Francour, Reference Francour1994; Dufour et al., Reference Dufour, Jouvenel and Galzin1995; McClanahan et al., Reference McClanahan, Muthiga, Kamukuru, Machano and Kimbo1999; Jennings, Reference Jennings2001; Côté et al., Reference Côté, Mosqueira and Reynolds2001; Macpherson et al., Reference Macpherson, Gordoa and García-Rubiés2002; Claudet et al., Reference Claudet, Pelletier, Jouvenel, Bachet and Galzin2006). However, this effect could not be extrapolated to the level of family or species. Species targeted by exploitation are affected in a more positive way than non-targeted species (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Mosqueira and Reynolds2001), even in the case of recreationally fished species (Westera et al., Reference Westera, Lavery and Hyndes2003). Although S. salpa is not a targeted species, it is regularly fished by spearfisherman and more often by shore-anglers (Morales-Nin et al., Reference Morales-Nin, Moranta, García, Tugores, Grau, Riera and Cerdà2005), and also is used as a ‘training’ species for inexperienced spearfishermen (personal observation). Spearfishing is a largely recreational activity, occurring mostly during the warm season (June to September) in shallow inshore waters in the Mediterranean Sea (Jouvenel & Pollard, Reference Jouvenel and Pollard2001). The presence of larger individuals and thus larger biomass in the protected locations is explained by a reduction in fish mortality (Lenfant, Reference Lenfant2003). A higher proportion of larger individuals in protected areas has already been found for various fish species in this same protected area (Banyuls and Cerbère) (Bell, Reference Bell1983), and in other Mediterranean marine reserves (García-Rubiés & Zabala, Reference García-Rubiés and Zabala1990; Harmelin et al., Reference Harmelin, Bachet and García1995; Reñones et al., Reference Reñones, Moranta, Coll and Morales-Nin1997).

Differences in behaviour attributable to protection effects can arise, among others, from two main sources: a differential feeding preference (as a function of fish size) and a differential response to human disturbance. Clearly different behaviours were observed between protected and unprotected sites. Inside the protected areas fish are observed to eat only on seagrass leaves. Outside the MPA fish tend to divide their feeding time between seagrass leaves and algae. This trend can be explained by the ontogeny in feeding described for this species. According to Verlaque (Reference Verlaque1990), young individuals, less than 2.5 cm, are carnivores feeding mainly on crustaceans (Christensen Reference Christensen1978; Anato & Ktari, Reference Anato and Ktari1983; Verlaque, Reference Verlaque1985) as is common for Sparidae (Lenfant & Olive, Reference Lenfant and Olive1998) whereas adult individuals become herbivorous. Verlaque (Reference Verlaque1990) also indicated that S. salpa larger than 30 cm only contain fragments of P. oceanica and its epiphytes in their digestive tube. Such observations may explain the absence of feeding on algae in the protected meadows as only fish larger than 30 cm in length are found within the Marine Reserves. However, a difference in algal composition inside versus outside protected areas may also explain such a result. Although this hypothesis cannot be tested at present, the sites were selected under a criterion of similarity, therefore it is unlikely that an unpalatable species of algae was only present inside the protected sites. Nevertheless, future studies should be carried out in order to test this possibility.

Fish outside MPAs spend more time in the water column compared to inside protected areas: when one grazing school is disturbed (by yachts, fishing, etc), all the individuals swim up in the water column at the same time, where they remain before resuming normal feeding behaviour (Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2006). Feeding differences between protected and unprotected locations may arise from the shorter recovery period observed inside protected areas (20 seconds to 1 minute) compared to outside reserves (2 to 5 minutes) probably due to a lower perception of risk (Ferrari, personal observation).

Schools inside the protected meadows are formed by a high number of relatively large individuals (Francour, Reference Francour1994; Harmelin et al., Reference Harmelin, Bachet and García1995) that may come into contact with each other during feeding. When such a situation occurs, one of the individuals displaces itself in order to find a less crowded area in which to feed (Ferrari, personal observation). This would explain the lower number of bites per minute recorded inside regulated areas, which is being compensated for by the larger leaf surface removed per bite.

Examples of changes in fish behaviour within marine reserves have previously been mentioned (Cole, Reference Cole1994; Willis et al., Reference Willis, Millar and Babcock2000). These authors have pointed out that fish can be habituated to divers and, moreover, attracted in response to hand feeding. These results, together with the ones presented in this study, show that the lower perception of risk behaviour displayed inside protected locations is an important factor that should be considered when management measures are enforced.

In conclusion, the establishment of protection measures in areas where P. oceanica meadows are present has measurable effects on the associated herbivorous fish community. Whether or not these differences represent a benefit for the meadow is unclear and needs to be established. However, our results indicate that the impacts of MPAs on key ecosystem processes have to be considered if we are to improve the success and use of MPAs as a potential management tool (Hoegh-Guldberg, Reference Hoegh-Guldberg2006).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank T. Alcoverro for her statistical assistance and helpful comments during the preparation of the text. We gratefully acknowledge two anonymous referees for their constructive criticism of the manuscript. This research was funded by the Conseil Général of Pyrénés Orientales. We also thank S. Mills for her help with editing the manuscript.