Introduction

Planoceridae Stimpson, 1857 is one of the 10 families of acotylean polyclads belonging to the superfamily Stylochoidea Stimpson, 1857 (Faubel, Reference Faubel1983, Reference Faubel1984; Dittmann et al., Reference Dittmann, Cuadrado, Aguado, Noreña and Egger2019). Members of Planoceridae are characterized by possession of eversible cirri armed with hard structures (e.g. spines, thorns or teeth) in the male copulatory apparatus. Some planocerids also have cuticularized tissue in their female copulatory apparatus (e.g. Hyman, Reference Hyman1953), part of which can take the form of spines in the vagina (cf. Kato, Reference Kato1944).

To date, seven genera have been assigned to Planoceridae (Faubel, Reference Faubel1983; Bulnes, Reference Bulnes2010). These genera are distinguished from each other by the presence or absence of the following structures: nuchal tentacles; a muscular bulb surrounding the cirrus; a seminal vesicle and accessory organs in the male genital complex; and a Lang's vesicle and bursa copulatrix in the female reproductive organs.

In the present paper, we establish a new genus of Planoceridae based on a new species collected offshore of the Izu Peninsula, West Pacific, Japan. We provide a partial sequence of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene as a DNA barcode for this new species. Furthermore, we estimate the phylogenetic position of the genus within Planoceridae using partial sequences of COI and 16S, 18S, and 28S ribosomal DNA (rDNA). Finally, based on our findings, we discuss the evolutionary history of the cuticularized structures in the vagina of Planoceridae as well as the function of accessory organs in the male copulatory apparatus.

Materials and methods

During the 18th Japanese Association for Marine Biology (JAMBIO) Coastal Organism Joint Survey, two marine worm specimens were collected from a depth of 245 m by dredging off the coast of the Izu Peninsula on the West Pacific side of Japan. The worms were anaesthetized in a MgCl2 solution (prepared with tap water to have the same salinity as the seawater) and then photographed following the method of Oya & Kajihara (Reference Oya and Kajihara2019). For DNA extraction, a piece of the body margin (lateral to pharynx) was cut away from each specimen and fixed in 100% ethanol. The rest of the body was fixed in Bouin's solution for 24 h, preserved in 70% ethanol, and then cut into two pieces (anterior and posterior). The anterior piece was dehydrated in an ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and observed under a Nikon SMZ 1500 stereomicroscope; this piece was preserved in 70% ethanol after observation. The posterior piece was used for histological observations, which were conducted according to the protocol of Oya & Kajihara (Reference Oya and Kajihara2019). Type specimens have been deposited in the Invertebrate Collection of the Hokkaido University Museum (ICHUM), Sapporo, Japan.

Total DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The partial sequences of 16S (438 bp), 18S (1736 bp) and 28S rDNA (1038 bp) (hereafter referred to simply as 16S, 18S and 28S) as well as that of COI (712 bp) were sequenced from one specimen following the methods of Oya & Kajihara (Reference Oya and Kajihara2020). The COI sequence was also determined from another specimen. In addition, the same markers from Paraplanocera oligoglena (Schmarda, 1859) were also determined for the purposes of phylogenetic analyses following the protocol by Oya & Kajihara (Reference Oya and Kajihara2020). Sequences were checked and edited using MEGA ver. 7.0 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016), and the genetic distances were calculated (also via MEGA ver. 7.0). All sequences determined in this study have been deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases with the accession numbers LC545561–LC545569.

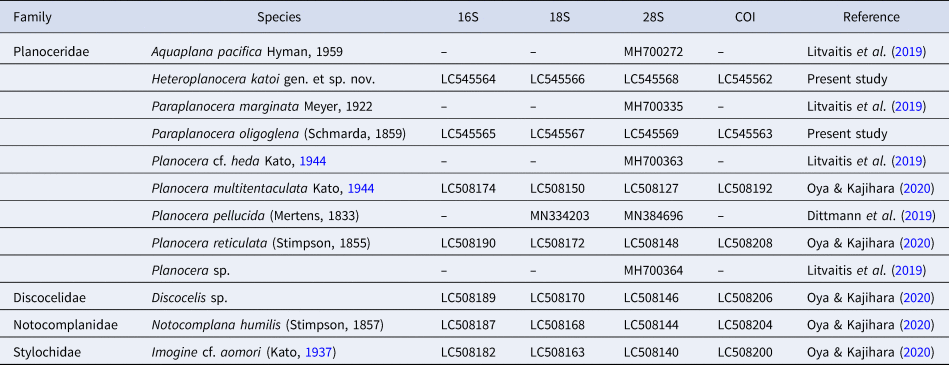

Additional sequences of Planoceridae and outgroup species were downloaded from GenBank. The outgroup taxa comprised three acotylean species: Discocelis sp., Imogine cf. aomori (Kato, Reference Kato1937) and Notocomplana humilis (Stimpson, 1857) (Table 1). The 16S, 18S and 28S sequences were aligned using MAFFT ver. 7 (Katoh & Standley, Reference Katoh and Standley2013), with the L-INS-i strategy selected by the ‘Auto’ option. Ambiguous sites were removed with Gblocks ver. 0.91b (Castresana, Reference Castresana2002) using a more stringent selection. The COI sequences were aligned manually using MEGA ver. 7.0. The concatenated dataset from the four genes was 3708 bp long and contained 12 terminal taxa.

Table 1. List of species included in the molecular phylogenetic analysis and the respective GenBank accession numbers

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using (i) the maximum likelihood (ML) method executed in IQtree ver. 1.6 (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Schmidt, von Haeseler and Minh2015) under a partition model (Chernomor et al., Reference Chernomor, von Haeseler and Minh2016) and (ii) Bayesian inference (BI) executed in MrBayes ver. 3.2.2 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck, Reference Ronquist and Huelsenbeck2003). The optimal substitution models for the ML analysis, which were selected with PartitionFinder ver. 2.1.1 (Lanfear et al., Reference Lanfear, Frandsen, Wright, Senfeld and Calcott2016) under the Akaike information criterion (Akaike, Reference Akaike1974) using the greedy algorithm (Lanfear et al., Reference Lanfear, Calcott, Ho and Guindon2012), were GTR + G (16S), GTR + I (18S), GTR + I + G (28S, first codon position in COI), TIM + G (third codon position in COI), and TVM + I + G (second codon position in COI); the corresponding models for BI were GTR + G (16S, third codon position in COI), GTR + I (18S, second codon position in COI), and GTR + I + G (28S, first codon positions in COI). Nodal support within the ML tree was assessed by analyses of 1000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates. For BI, the Markov chain Monte Carlo process used random starting trees and involved four chains run for 1,000,000 generations with the first 25% of trees discarded as burn-in. We considered posterior probability (PP) values ≥0.90 and ML bootstrap (BS) values ≥70% to indicate clade support; in the text, combined nodal support is represented as PP/BS.

Results

Systematics

Family PLANOCERIDAE Stimpson, 1857

Genus Heteroplanocera gen. nov.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:4289C802-A09E-436F-ADCB-45E9BE6DB405

Type species

Heteroplanocera katoi sp. nov., fixed by original designation.

Diagnosis

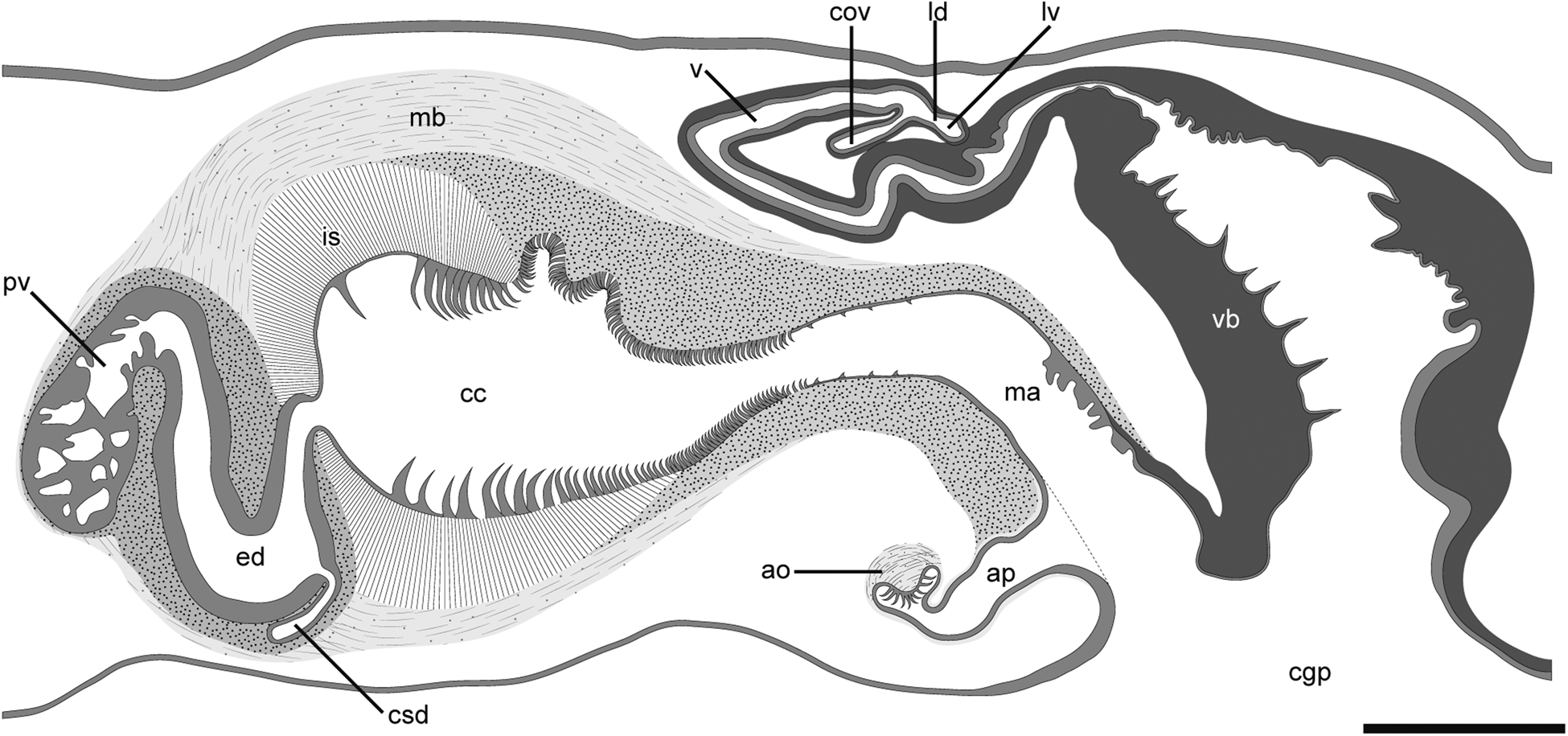

Planoceridae with oval body, nuchal tentacles, pair of spermiducal bulbs, free prostatic vesicle with tubular folded epithelium, ejaculatory duct with prostatic-like epithelium, cirrus with numerous teeth enclosed by muscular bulb, pair of accessory organs with eosinophilic glands and teeth, rudimentary Lang's vesicle, vagina bulbosa with cuticularized epithelium, common gonopore, and without bursa copulatrix (Figures 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. Heteroplanocera katoi gen. et sp. nov. (ICHUM 6081, holotype), photographs taken in life (A, B, D) and in preserved state cleared with xylene (C): (A) dorsal view; (B) ventral view; (C) eyespots; (D) sperm ducts and oviducts observed from ventral view. Abbreviations: ce, cerebral eyespot; cgp, common gonopore; o, ovary; ov, oviduct; ph, pharynx; sb, spermiducal bulb; sd, sperm duct; t, tentacle; te, tentacular eyespot. Scale bars: A, B, 5 mm; C, D, 1 mm.

Fig. 2. Schematic diagram of copulatory apparatuses in Heteroplanocera katoi gen. et sp. nov. (ICHUM 6081, holotype): Abbreviations: ao, accessory organ; ap, accessory pouch; cc, cirrus cavity; cgp, common gonopore; cov, common oviduct; csd, common sperm duct; ed, ejaculatory duct; is, intermuscular space; ld, Lang's-vesicle duct; lv, Lang's vesicle; ma, male atrium; mb, muscular bulb; pv, prostatic vesicle; v, vagina; vb, vagina bulbosa. Scale bar: 300 μm.

Etymology

The new generic name is feminine in gender, formed by the combination of the prefix hetero (meaning ‘other, another, different’) and the existing genus name Planocera Blainville, 1828, indicating the close taxonomic proximity of the new genus to the existing genus.

Heteroplanocera katoi sp. nov.

(Figures 1–4)

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:F26761F2-9BE9-48F2-A4AD-37914FE11872

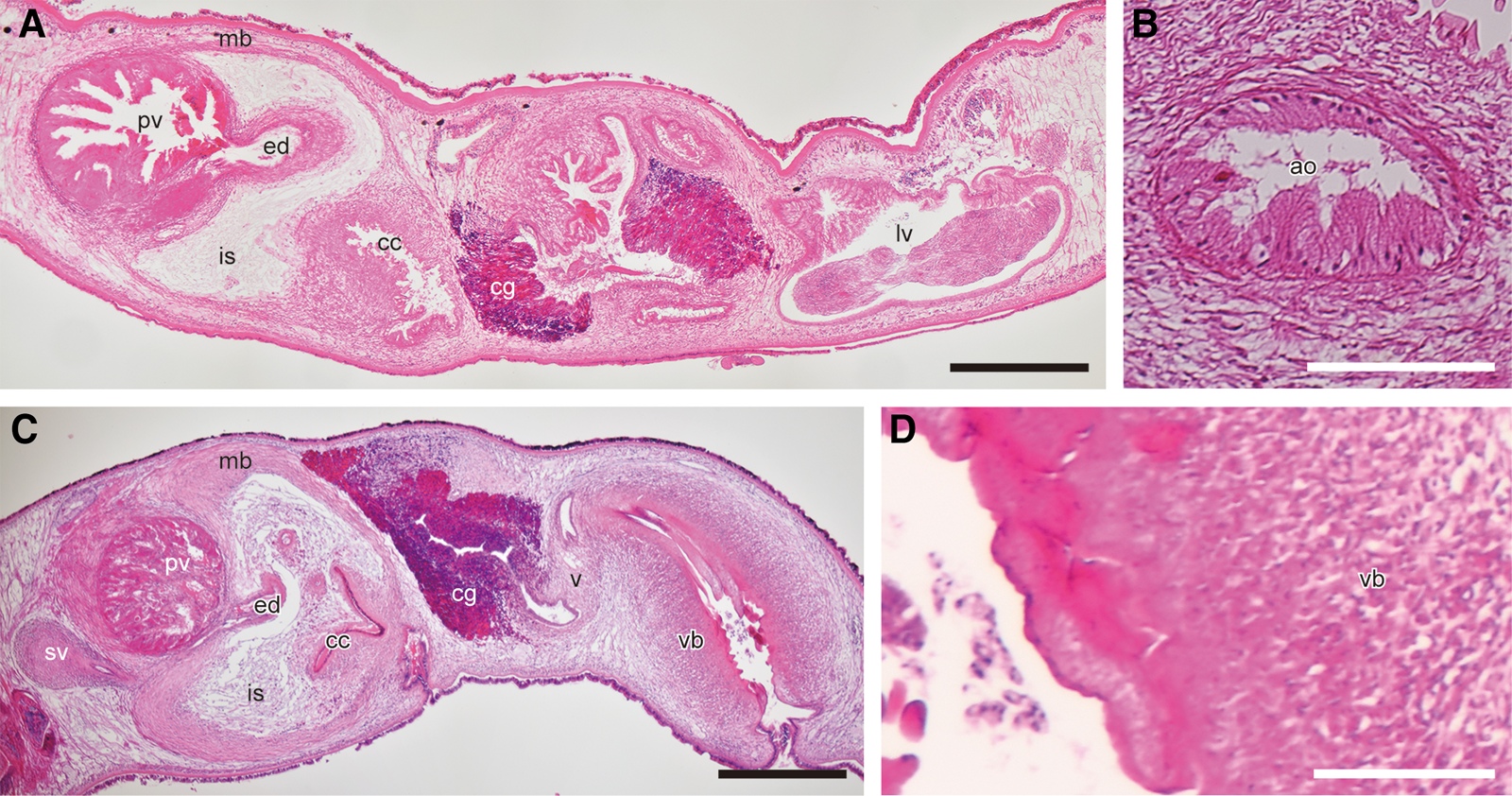

Fig. 3. Photomicrographs of sagittal sections of Heteroplanocera katoi gen. et sp. nov. (ICHUM 6081, holotype): (A, B) Male and female copulatory apparatuses; (C–F) running of sperm duct. Abbreviations: ao, accessory organ; ap, accessory pouch; cc, cirrus cavity; cg, cement glands; cgp, common gonopore; cov, common oviduct; csd, common sperm duct; ed, ejaculatory duct; is, intermuscular space; ma, male atrium; mb, muscular bulb; pv, prostatic vesicle; sb, spermiducal bulb; sd, sperm duct; v, vagina; vb, vagina bulbosa. Scale bars: A, 500 μm; B–F, 300 μm.

Fig. 4. Photomicrographs of sagittal sections of Heteroplanocera katoi gen. et sp. nov. (ICHUM 6081, holotype): (A, C, D) Teeth in cirrus; (B) cross view of large tooth; (E) accessory organ; (F) Lang's vesicle; (G) spines of vagina bulbosa. Abbreviations: ao, accessory organ; ap, accessory pouch; cc, cirrus cavity; is, intermuscular space; ld, Lang's-vesicle duct; lv, Lang's vesicle; mb, muscular bulb; s, spine; vb, vagina bulbosa. Scale bars: A, C, D, F, 50 μm; B, 10 μm; E, G, 100 μm.

Etymology

The specific name is a noun in the genitive case honouring Dr Kojiro Kato (1906–1981), who studied Japanese polyclads.

Type material

Holotype: ICHUM 6081, one-third of body from anterior end preserved in 70% ethanol and sagittal sections of remaining body, 22 slides; off the coast of the Izu Peninsula, Shizuoka, Japan (34°39′11″N 138°43′12″E to 34°39′15″N 138°43′21″E; 245 m depth); coll. Y. Oya, 12 December 2018.

Paratype: ICHUM 6082, one-third of body from anterior end preserved in 70% ethanol and sagittal sections of remaining body, 20 slides; hereafter, same data as holotype.

Comparative material examined

Paraplanocera oligoglena (Schmarda, 1859). Non-type: ICHUM 6083, sagittal sections of 20 slides; Bonomisaki, Kagoshima, Japan (31°15′15″N 130°12′54″E; subtidal); coll. Y. Oya, 26 July 2018.

Planocera reticulata (Stimpson, 1855). Non-type: ICHUM 6018, sagittal sections of 16 slides; hereafter, same data as ICHUM 6083.

Description

Live specimens 18–21 mm (18 mm in holotype) in length, 12–14 mm (12 mm in holotype) in maximum width. Body oval (Figure 1A, B). Ground body colour translucent to opaque whitish (Figure 1A). Pair of nuchal tentacles located about three-tenths of body length (5.4–5.9 mm; 5.4 mm in holotype) from anterior end (Figure 1A). Tentacular eye clusters congregated in bases of each tentacle and containing 10–14 eyespots (11 in right cluster, 14 in left cluster in holotype; Figure 1C). Pair of cerebral eye clusters, each consisting of 4–6 eyespots (4 in right cluster, 5 in left cluster in holotype; Figure 1C), arranged near median line and congregated anterior to tentacular eyespots. Pharynx whitish, ruffled in shape, occupying about two-ninths of body length (4.1–4.9 mm in length; 4.1 mm in holotype), located at centre of body (Figure 1B). Intestine not anastomosed, spreading throughout body except margin. Mouth opening at near centre of pharynx. Ovary distributed around pharynx. Common gonopore opening at about three-tenths (5.1–6.6 mm; 5.1 mm in holotype) from posterior end of body (Figure 1D).

Male copulatory apparatus located posterior to pharynx, consisting of pair of spermiducal bulbs, free prostatic vesicle, cirrus, and pair of accessory organs; seminal vesicle lacking (Figures 2 and 3A–F). Sperm ducts running anteriorly, then turning medially at point posterior to pharynx, forming spermiducal bulbs (Figures 1D and 3C). Distal end of spermiducal bulbs connecting to distal section of sperm duct (Figure 3D), latter running anteriorly (Figure 3E), then forming common sperm duct (Figure 3F). Common sperm duct entering middle section of ejaculatory duct from ventral side. Ejaculatory duct lined with smooth, prostatic-like glandular epithelium (Figure 3A, F). Prostatic vesicle elongated, oval-shaped, possessing tubular folded epithelium, connecting proximal end of ejaculatory duct (Figures 2 and 3A, E). Prostatic vesicle and ejaculatory duct coated with thick muscular wall (Figure 3A, F). Distal end of ejaculatory duct opening to cirrus cavity. Inner epithelium of cirrus possessing three types of teeth. Teeth in proximal section of cirrus hook-shaped, large, becoming smaller and denser in distal part (Figure 4A); base of tooth grooved (Figure 4B), becoming smooth toward tip. Teeth in middle section of cirrus same shape and size as small ones in proximal section, densely distributed (Figure 4C). Teeth in distal section of cirrus curved hook-shaped, small, sparsely distributed (Figure 4D). Cirrus, prostatic vesicle and ejaculatory duct enclosed by muscular bulb. Distal section of cirrus connecting to male atrium, latter opening at common gonopore (Figure 3A). Ventral surface of male atrium smooth, lined with ciliated epithelium. Proximal dorsal surface of male atrium folded, lined with ciliated epithelium (Figure 3E). Distal dorsal surface of male atrium smooth, lined with cuticularized epithelium, connecting to that of vagina bulbosa (Figure 3A). Pair of accessory pouches, lined with ciliated epithelium, opening to ventral side of male atrium (Figures 3A and 4E). Accessory organs located at end of each accessory pouch, consisting of eosinophilic glands, developed muscle, and several hook-shaped teeth (Figure 4E).

Pair of oviducts forming common oviduct, latter running postero-dorsally to enter vagina. From this point, short Lang's-vesicle duct running postero-ventrally to connect to Lang's vesicle (Figure 4F). Lang's vesicle rudimentary, spherical, lined with epithelium similar to that in Lang's-vesicle duct (Figure 4F). Vagina curving antero-ventrally, running posteriorly, connecting to vagina bulbosa (Figure 3A); vagina lined with smooth, ciliated epithelium, coated with thick muscular wall. Proximal section of vagina surrounded by cement glands. Vagina bulbosa with cuticularized epithelium possessing several spines, surrounded by developed muscular wall, exiting common gonopore (Figures 3A and 4G). Bursa copulatrix absent. Mass of sperm-like structure observed in atrium of vagina bulbosa and male atrium (Figure 3A).

Habitat

Judging from the nature of the dredged material, the species' habitat is likely to be mud-type sediment.

COI sequence

The partial COI sequences (712 bp) of the two specimens (LC545561 and LC545562) were almost identical. The uncorrected P-distance between the specimens was 0.004.

Molecular phylogeny

The BI and ML trees were identical in their topology; only the BI tree is shown (Figure 5). Within the Planoceridae clade, Heteroplanocea katoi gen. et sp. nov. was a sister to the Planocera clade with high support (0.99/91).

Fig. 5. Bayesian phylogenetic tree based on sequences from four genes (16S, 18S and 28S ribosomal DNA; cytochrome c oxidase subunit I; concatenated length 3708 bp). Numbers near nodes represent posterior probability and bootstrap values, respectively.

Discussion

Genus-level identification

Among the seven existing genera in Planoceridae sensu Faubel (Reference Faubel1983), Heteroplanocera is morphologically similar to Paraplanocera Laidlaw, 1903 and Planocera Blainville, 1828. It shares the following traits with these two genera: a (i) pair of nuchal tentacles, (ii) muscular bulb surrounding the cirrus, (iii) free prostatic vesicle and (iv) Lang's vesicle (Figure 6A, C; Table 2). In addition, Heteroplanocera resembles Paraplanocera as it possesses (i) a pair of spermiducal bulbs instead of a seminal vesicle and (ii) a pair of accessory organs on the ventral side of the male atrium (Figure 6B). However, Heteroplanocera also shows resemblance to Planocera in that it has a rudimentary Lang's vesicle and a developed vagina bulbosa with a cuticularized epithelium (Figure 6D).

Fig. 6. Photomicrographs of sagittal sections of Paraplanocera oligoglena (Schmarda, 1859) (A, B; ICHUM 6083) and Planocera reticulata (Stimpson, 1855) (C, D; ICHUM 6018): (A, C) copulatory apparatuses; (B) accessory organ; (D) cuticle of vagina bulbosa. Abbreviations: ao, accessory organ; cc, cirrus cavity; cg, cement glands; ed, ejaculatory duct; is, intermuscular space; lv, Lang's vesicle; mb, muscular bulb; pv, prostatic vesicle; sv, seminal vesicle; v, vagina; vb, vagina bulbosa. Scale bars: A, C, 500 μm; B, D, 100 μm.

Table 2. Comparison of morphological characteristics between genera in Planoceridae sensu Faubel (Reference Faubel1983)

a Aquaplana should be treated as an invalid taxon because Faubel (Reference Faubel1983) has transferred Aquaplana oceanica Hyman, Reference Hyman1953, the type species of Aquaplana, to Paraplanocera. It is therefore included in this table for comparison purposes only.

b Prudhoe (Reference Prudhoe1985) classified these genera into Gnesiocerotidae Marcus & Marcus, 1966.

Heteroplanocera differs from Paraplanocera as its accessory organ has several teeth, whereas that of Paraplanocera is glandular and unarmed (Figure 6B). In addition, unlike Paraplanocera, Heteroplanocera lacks a bursa copulatrix and developed Lang's vesicle. Heteroplanocera is distinguished from Planocera as it lacks a seminal vesicle and has the accessory organs in the male genital complex (Figure 6C, D). Moreover, among Planoceridae, a common gonopore is observed only in Heteroplanocera (Figure 3A). Furthermore, Heteroplanocera is phylogenetically separated from Paraplanocera and Planocera (Figure 5). Thus, establishing Heteroplanocera as a new genus is justified.

Cuticularized structure in vagina bulbosa

The cuticularized epithelium of the vagina bulbosa in H. katoi is likely a result of co-evolution between the male and female copulatory apparatuses. In some insects with armed male copulatory apparatuses, the inner surface of the female tract tends be thickened or sclerotized (e.g. Rönn et al., Reference Rönn, Katvala and Arnqvist2007; Kamimura, Reference Kamimura2012). This ‘hardening’ of the copulatory apparatuses in both sexes is one of the trends observed in male–female co-evolution related to traumatic mating (Lange et al., Reference Lange, Reinhardt, Michiels and Anthes2013). Polyclad flatworms employ three methods for sperm transfer: direct copulation, dermal impregnation and hypodermic insemination (Rawlinson et al., Reference Rawlinson, Marcela Bolaños, Liana and Litvaitis2008). Lang (Reference Lang1884, p. 307) presumed that polyclads possessing hard structures (penis stylet or teeth) in the intromittent organ and a vagina bulbosa (‘bursa copulatrix’ in Lang Reference Lang1884) in the female copulatory apparatus employed direct copulation. Although the copulatory behaviour of H. katoi has not yet been observed, we speculate that the present species also perform a direct copulation, with the cuticle on the vagina bulbosa acting as protection against the numerous teeth on the male genitalia.

Significantly, our phylogenetic analysis showed that the spines on the vagina bulbosa evolved at least twice within the Heteroplanocera + Planocera clade. Among the species we included in our analyses, only Planocera multitentaculata Kato, Reference Kato1944, other than H. katoi, has distinct spines on the vagina bulbosa; whether these are also present in the Planocera sp. identified by Litvaitis et al. (Reference Litvaitis, Bolaños and Quiroga2019) is unknown. We postulate that the vagina bulbosa was lined with cuticularized tissue in the last common ancestor of the Heteroplanocera + Planocera clade, and then the spines evolved independently in each lineage of Heteroplanocera and P. multitentaculata (Figure 7). Among the Planocera species not included in the present analysis, similar spines have also been described in P. gilchristi Jacubowa, 1906 and P. uncinata Palombi, Reference Palombi1939 (Jacubowa, Reference Jacubowa1907; Palombi, Reference Palombi1939). Including these species in future studies should fully elucidate the evolution of these ‘female spines’ among planocerids.

Fig. 7. Hypothesis for the evolution of spines in the vagina bulbosa based on the tree topology obtained from the molecular phylogenetic analysis in the present study.

Accessory organs

The accessory organs and their surrounding structure in H. katoi suggest that the organs are everted along with the cirrus during the course of mating. These organs possess hook-shaped teeth and a developed muscular part (Figure 4E). The muscle likely supports the eversion of the organs and the teeth likely assist in holding the mating partner during copulation; perhaps the teeth also injure the female tract. In future research, behavioural observation will improve our understanding of the function of these organs, as is also the case with the cuticularized tissue in the vagina bulbosa.

The homology of the accessory organ in Planoceridae is unclear. The components of the organ differ between Heteroplanocera and Paraplanocera (Figures 4E and 6B; see above). Planocerids in the genus Neoplanocera Yeri & Kaburaki, Reference Yeri and Kaburaki1918 have a structure similar to the accessory organ. In Neoplanocera, this structure has a developed muscle similar to that in the accessory organ of H. katoi; however, it is papilla-like in shape and does not exist in a pair (Yeri & Kaburaki, Reference Yeri and Kaburaki1918, text-figure 18; Kato, Reference Kato1937, text-figure 14, plate 14, figure 8). Given that the phylogenetic position of Neoplanocera has yet to be tested by molecular analyses, it is possible that this genus is not even encompassed in Planoceridae because its external morphology (e.g. body shape and the formation of eye clusters) is more similar to that of leptoplanoids than that of planocerids (Yeri & Kaburaki, Reference Yeri and Kaburaki1918, text-figure 17, plate 2, figure 4; Kato, Reference Kato1937, text-figures 11 and 12). In order to evaluate the homology of the accessory organs among planocerids, it will be necessary in future studies to conduct not only detailed morphological and phylogenetic examinations but also developmental observations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Daisuke Shibata (University of Tsukuba), Mr Hisanori Kohtsuka (the University of Tokyo), Dr Hiroaki Nakano and staff of the Shimoda Marine Research Center (University of Tsukuba), and all participants in the 18th Japanese Association for Marine Biology (JAMBIO) Coastal Organism Joint Survey conducted at Shimoda for the assistance in collecting specimens; Dr Daisuke Uyeno and Ms Midori Matsuoka (Kagoshima University), Dr Naoto Jimi (National Institute of Polar Research) and Ms Aoi Tsuyuki (Hokkaido University) for helping in sampling in Kagoshima.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Japanese Association for Marine Biology (JAMBIO) and the Research Institute of Marine Invertebrates (No. 2017 IKU-3).