INTRODUCTION

Coastal ecosystems are under constant pressure from anthropogenic contaminants originating from various sources located at the catchment regions or more distant places (Kumar Gupta & Singh, Reference Kumar Gupta and Singh2011; Sanz-Lázaro et al., Reference Sanz-Lázaro, Malea, Apostolaki, Kalantzi, Marín and Karakassis2012). The contamination of aquatic ecosystems by potentially toxic elements (PTE) is a major concern because of their toxicity and bioaccumulative nature (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Shi, He, Liu, Liang and Jiang2004; Ghrefat & Yusuf, Reference Ghrefat and Yusuf2006; Nemati et al., Reference Nemati, Abu Bakar, Abas and Sobhanzadeh2011). In recent years, increasing consideration has been extended to the relationship between the concentration of PTE in the environment and their impact on aquatic organisms (Kumar Gupta & Singh, Reference Kumar Gupta and Singh2011). Marine biota have the capacity to accumulate PTE from the surrounding abiotic and/or biotic environment (Conti et al., Reference Conti, Tudino, Muse and Cecchetti2002; Gray, Reference Gray2002; Pereira Majer et al., Reference Pereira Majer, Varella Petti, Navajas Corbisier, Portella Ribeiro, Sawamura Theophilo, de Lima Ferreira and Lopes Figueira2014). The bioaccumulation and biomagnification of PTE in aquatic food webs not only threatens biodiversity, but may impact humans as well – through the consumption of contaminated seafood (Jitar et al., Reference Jitar, Teodosiu, Oros, Plavan and Nicoara2015).

The use of marine animals and plants as bioindicators for coastal zone PTE pollution is very frequent and widespread (Nicolaidou & Nott, Reference Nicolaidou and Nott1998; Campanella et al., Reference Campanella, Conti, Cubadda and Sucapane2001; Conti & Cecchetti, Reference Conti and Cecchetti2003; Ravera et al., Reference Ravera, Cenci, Beone, Dantas and Lodigiani2003; Khristoforova & Chernova, Reference Khristoforova and Chernova2005; Ali & Bream, Reference Ali and Bream2010; Al-Busaidi et al., Reference Al-Busaidi, Yesudhason, Al-Waili, Al-Rahbi, Al-Harthy, Al-Mazrooei and Al-Habsi2013; Duysak & Ersoy, Reference Duysak and Ersoy2014; Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Bagher Nabavi, Pazooki and Parsa2014; Pereira Majer et al., Reference Pereira Majer, Varella Petti, Navajas Corbisier, Portella Ribeiro, Sawamura Theophilo, de Lima Ferreira and Lopes Figueira2014). Various groups of marine organisms can be used as bioindicators, mainly those characterized by a wide geographic distribution, sessile or sedentary nature, year-round availability, and ease of identification and sampling (Cubadda et al., Reference Cubadda, Conti and Campanella2001; Conti et al., Reference Conti, Tudino, Muse and Cecchetti2002; Kumar Gupta & Singh, Reference Kumar Gupta and Singh2011). Molluscs, macroalgae and seagrasses are some of the most commonly used species for this purpose (Conti et al., Reference Conti, Bocca, Iacobucci, Finoia, Mecozzi, Pino and Alimonti2010; Thangaradjou et al., Reference Thangaradjou, Nobi, Dilipan, Sivakumar and Susila2010; Llagostera et al., Reference Llagostera, Perez and Romero2011; Jitar et al., Reference Jitar, Teodosiu, Oros, Plavan and Nicoara2015).

Since chemical contaminants have been repeatedly identified as one of the major threats to the biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea (Tornero & Ribera d'Alcalà, Reference Tornero and Ribera d'Alcalà2014), chemical pollution in the marine environment has been placed as a top priority within the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD 2008/56/EC). Accordingly, two out of the 11 MSFD qualitative descriptors for determining Good Environmental Status (GEnS) by 2020 are linked to the contamination of the environment and biota (seafood).

The accumulation of PTE in the tissues of living organisms is species-dependent and is related to the mechanisms of detoxification and metabolism (Jakimska et al., Reference Jakimska, Konieczka, Skóra and Namieśnik2011; Kumar Gupta & Singh, Reference Kumar Gupta and Singh2011). As a consequence, different levels of PTE can be found in a variety of organisms from the same environment (Conti et al., Reference Conti, Bocca, Iacobucci, Finoia, Mecozzi, Pino and Alimonti2010; Jakimska et al., Reference Jakimska, Konieczka, Skóra and Namieśnik2011). The bioaccumulation of PTE in higher trophic organisms is also affected by the number of passages of the PTE through the trophic chain (Conti & Cecchetti, Reference Conti and Cecchetti2003; Jakimska et al., Reference Jakimska, Konieczka, Skóra and Namieśnik2011; Ergűl & Aksan, Reference Ergűl and Aksan2013; Jitar et al., Reference Jitar, Teodosiu, Oros, Plavan and Nicoara2015; Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Bagher Nabavi, Pazooki and Parsa2014; Pereira Majer et al., Reference Pereira Majer, Varella Petti, Navajas Corbisier, Portella Ribeiro, Sawamura Theophilo, de Lima Ferreira and Lopes Figueira2014).

Currently, few studies are available regarding the concentrations of PTE in the various organisms of the Adriatic Sea (Gavrilović et al., Reference Gavrilović, Srebočan, Petrinec, Pompe-Gotal and Prevendar-Crnić2004; Kljaković-Gašpić et al., Reference Kljaković-Gašpić, Antolić, Zvonarić and Barić2004, Reference Kljaković-Gašpić, Ujević, Zvonarić and Barić2007; Bogdanović et al., Reference Bogdanović, Ujević, Sedak, Listeš, Šimat, Petričević and Poljak2014; Bille et al., Reference Bille, Binato, Cappa, Toson, Pozza, Arcangeli, Ricci, Angeletti and Piro2015; Ujević et al., Reference Ujević, Vuletić, Lušić, Nazlić and Kušpilić2015). Our recent papers (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Rogan Šmuc, Lojen, Kniewald, Matešić, Lambaša Belak and Dolenec2014, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Lojen, Lambaša Belak, Kniewald and Rogan Šmucb) mainly focused on PTE accumulation and their speciation in recent marine sediments in Makirina Bay (Central Adriatic). The results of the enrichment factors (EF) and sequential leaching procedure indicated the human-induced introduction of arsenic (As), copper (Cu) and lead (Pb) into the sediments. The introduction of As and Cu is mainly a result of agricultural activity in the surrounding area, while the presence of Pb is primarily related to traffic (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a).

The present study focuses on the contamination with PTE of two other major coastal ecosystem components: seawater and the biota comprising the Lesser Neptune grass Cymodocea nodosa (Ucria) Ascherson, 1870; the green alga Cladophora echinus (Biasoletto) Kützing, 1849; the red alga Gelidiella lubrica (Kützing) Feldmann and G. Hamel, 1934; the marine topshell Phorcus turbinatus Born, 1778 and the littoral crab Carcinus aestuarii Nardo, 1847. The overall purpose of this study was to evaluate the quality of the coastal ecosystem in Makirina Bay in relation to PTE contamination. Moreover, the assessment of the bioaccumulation rates of the five selected species enabled the evaluation of their possible use as bioindicators in a future monitoring programme for PTE pollution in the Adriatic Sea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

Makirina Bay, situated in Northern Dalmatia (Croatia), is a cove with a north-to-south extension and represents the southern part of Pirovac Bay (Figure 1). Its wider area is composed mostly of Cretaceous carbonate rocks and Quaternary sediments (Šparica et al., Reference Šparica, Koch, Belak, Miko, Šparica-Miko, Viličić, Dolenec, Bergant, Lojen, Vreča, Dolenec, Ogrinc and Ibrahimpašić2005). The area surrounding the bay is cultivated (gardens, olives, orchards and vineyards) and sparsely populated. The only larger village nearby is Pirovac, with ~2000 inhabitants. The depth of the sea barely exceeds 0.5 m in the southern part of the bay and increases seawards to a depth of 4.5 m. The bottom of Makirina Bay is covered by a sediment body (up to 3 m thick), overgrown mostly by the seagrass C. nodosa (Šparica et al., Reference Šparica, Koch, Belak, Miko, Šparica-Miko, Viličić, Dolenec, Bergant, Lojen, Vreča, Dolenec, Ogrinc and Ibrahimpašić2005; Vreča & Dolenec, Reference Vreča and Dolenec2005; Miko et al., Reference Miko, Koch, Mesić, Šparica-Miko, Šparica, Čepelak, Bačani, Vreča, Dolenec and Bergant2008; Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Rogan Šmuc, Lojen, Kniewald, Matešić, Lambaša Belak and Dolenec2014, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Lojen, Lambaša Belak, Kniewald and Rogan Šmucb). The rocks in the upper-infralittoral belt of the bay are covered by macroalgae. The sediment of Makirina Bay has been extensively studied since it is frequently used for therapeutic and/or cosmetic treatments (Šparica et al., Reference Šparica, Koch, Belak, Miko, Šparica-Miko, Viličić, Dolenec, Bergant, Lojen, Vreča, Dolenec, Ogrinc and Ibrahimpašić2005; Vreča & Dolenec, Reference Vreča and Dolenec2005; Miko et al., Reference Miko, Koch, Mesić, Šparica-Miko, Šparica, Čepelak, Bačani, Vreča, Dolenec and Bergant2008; Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Rogan Šmuc, Lojen, Kniewald, Matešić, Lambaša Belak and Dolenec2014, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Lojen, Lambaša Belak, Kniewald and Rogan Šmucb).

Fig. 1. Location of Makirina Bay with sampling sites (Digital Orthophoto 1:5000, State Geodetic Directorate, Croatia).

Sampling and sample preparation

Samples of C. nodosa, C. echinus and G. lubrica were handpicked in the central part of the bay in May 2013 (Figure 1), washed in seawater, refrigerated and transported to the laboratory. The sampling site was the same as that for the previous sampling of sediments (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Rogan Šmuc, Lojen, Kniewald, Matešić, Lambaša Belak and Dolenec2014, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Lojen, Lambaša Belak, Kniewald and Rogan Šmucb). Specimens of P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii were collected in the tidal zone. Only individuals of similar size were selected. The shell size of P. turbinatus ranged from 15 to 20 mm in height, while individuals of C. aestuarii were around 40 mm in width (across the carapace). The organisms were immediately packed into PET bags, saved in a cool box and afterward deep-frozen.

The physicochemical properties of the seawater (T, pH and Eh) were recorded in the field with a pH-Eh meter Mettler Toledo. A combined glass electrode was used for pH and an InLab Redox micro-electrode for Eh measurements. Seawater samples were filtered (0.45 µm, Sartorius Minisart), acidified with suprapure HNO3 and kept in acid-washed HDPE bottles in a cooling box (<4°C) until further analysis. Seawater samples for particulate organic matter (POM) analyses were also collected in the central part of the bay. Five to 10 litres of water were filtered through 1.2 µm Whatman glass fibre microfilters. The filters were air-dried and kept dry-protected from light for later isotopic analyses.

In the laboratory, seagrass and algal samples were rinsed in distilled water. Sediments and epiphytes were carefully removed from grass leaves and algal thalli with a nylon brush. Seagrass shoots were separated into two parts: below- and aboveground. Plant samples were dried to a constant weight and then ground in an agate mill to obtain a homogeneous powder. Specimens of P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii were sectioned. The soft parts were taken out of the exoskeleton (shell) using a plastic tool to avoid PTE contamination. Subsequently, the samples were freeze-dried for at least 72 h until a constant weight was reached. Before further analyses, the dried samples were homogenized and crushed to a powder in an agate mill.

Analytical procedures

Samples of biota (flora and fauna) were chosen to be analysed quantitatively for the presence of several PTE and to determine their nitrogen stable isotopic composition (δ 15N).

PTE DETERMINATION

The geochemical composition of the biota was determined using the certified commercial Activation Laboratories (Canada) by HR ICP-MS and MW-digestion. Dry, ashed samples were dissolved in aqua regia solution. The quality of the analysis was controlled using NIST 1575a standard material and duplicate measurements of the samples. The analytical precision and accuracy were within ±10% for all analysed elements. The detection limits (DL) for biota analysis were (in ng g−1): 5 (As), 0.1 (Cd), 0.5 (Co), 10 (Cr), 20 (Cu), 10 (Mn), 1 (Mo), 100 (Ni), 10 (Pb) and 200 (Zn).

The geochemical analysis of seawater samples was carried out using ICP-MS and ICP-OES methods. The quality of the analyses was assessed by blank samples, duplicate measurements and standard materials (NIST 1643e, SLRS-5). The analytical precision and accuracy were better than ±10%. The DL for seawater analysis were (in μg l−1): 0.03 (As), 0.01 (Cd), 0.005 (Co), 0.5 (Cr), 0.2 (Cu), 0.1 (Mn), 0.1 (Mo), 0.3 (Ni), 0.01 (Pb) and 0.5 (Zn).

BIOTA-SEDIMENT ACCUMULATION FACTOR (BSAF)

In order to evaluate the proportion in which PTE occurs in the organisms and in the associated sediment, BSAF were calculated for selected PTE in the organisms according to the following formula: BSAF = C x/C s, where C x and C s are the mean PTE contents in the different tissues of the organisms and associated sediment (Szefer et al., Reference Szefer, Ali, Ba-Haroon, Rajeh, Gełdon and Nabrzyski1999; Lafabrie et al., Reference Lafabrie, Pergent, Kantin, Pergent-Martini and Gonzales2007; Yap & Cheng, Reference Yap and Cheng2013). The organisms’ tissues can be defined as macroconcentrators (BSAF > 2), microconcentrators (1 < BSAF < 2) or deconcentrators (BSAF < 1) (Dallinger, Reference Dallinger, Dallinger and Rainbow1993).

CONCENTRATION FACTOR (CF)

The CF is the ratio between the PTE content in the organisms (algae, molluscs, crustaceans, etc.) and the surrounding seawater (Conti et al., Reference Conti, Tudino, Muse and Cecchetti2002). The CF can be used to measure the bioaccumulation ability of each species, to monitor the ecosystem state or to estimate its state of conservation (Conti & Cecchetti, Reference Conti and Cecchetti2003).

STABLE ISOTOPE RATIOS

The nitrogen stable isotope compositions of the POM, C. nodosa, C. echinus and C. aestuarii were measured with a mass spectrometer (Europa 20-20, ANCA-SL preparation module). The results are expressed in ‰ (per mil) as relative δ according to the following equation: δ 15N = ((R vz−R st)/R st) × 103, where R represents the 15N/14N ratio of the sample and the standard (atmospheric nitrogen). Positive δ 15N values reveal enrichment with the heavy isotope 15N, while negative values show its depletion. All samples were analysed in duplicate; if the standard deviation was greater than 0.3‰, analyses were repeated until the STD was within the required limits. USGS25, USGS26 and IAEA-NO3 certified reference materials were used to calibrate the measurements.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed by multivariate methods using the statistical software program Statistica 10. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed – the most accepted multivariate statistical method applied in environmental studies (Kortatsi et al., Reference Kortatsi, Anku and Anornu2009; Shakeri et al., Reference Shakeri, Shakeri and Mehrabi2015). Values <DL were replaced with LOD/√2, since this substitution produces the smallest error (Verbovšek, Reference Verbovšek2011).

RESULTS

Water analyses

The T of the seawater measured in the field was 20°C, its pH 8 and Eh 120 mV. The PTE concentrations in the Makirina Bay seawater samples are presented in Table 1, and decrease as follows: Zn > Ni > Mo > Cu > Mn > Co > Pb > Cd > As = Cr.

Table 1. PTE concentrations (μg l−1) in seawater samples from Makirina Bay in the Central Adriatic Sea.

DL, Detection limit. CCC, Criteria Continuous Concentration; CMC, Criteria Maximum Concentration.

a Cr(VI).

Concentrations of PTE in plant samples

The PTE concentrations in C. nodosa above-ground biomass were ordered in the following sequence: Mn > Cr > Zn > Ni > Cu > Pb > Mo > Co > As > Cd, while the sequence in its below-ground biomass was: Mn > Zn > Cr > Cu > Ni > Mo > Pb = As > Co > Cd (Table 2). The contents of the majority of the PTE analysed are higher in the above-ground biomass of C. nodosa.

Table 2. PTE concentrations (μg g−1) in biota (flora and fauna) of Makirina Bay.

The PTE concentrations in the thalli of C. echinus and G. lubrica showed a similar ranking order: Mn > Cr > Zn > Ni > Cu > Pb > As > Co > Mo > Cd and Mn > Zn > Cr > As > Ni > Cu > Pb > Co > Mo > Cd, respectively (Table 2). The concentrations of PTE in green and red algae were greater than their respective concentrations in seagrass tissues.

According to the PTE concentrations in sediments, only the concentrations of Mn in C. nodosa above-ground biomass, C. echinus and G. lubrica exceed their corresponding concentrations in sediment.

The calculated BSAF for As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb and Zn in C. nodosa, C. echinus and G. lubrica are shown in Table 3. Table 4 reports the calculated CF for the species examined. The highest BSAF for plants in Makirina Bay was observed for Mn (Table 3). All three plant species in Makirina Bay can be classified as macroconcentrators of Mn. The strongest accumulator of Mn proved to be G. lubrica, with a BSAF value = 3.3 (Table 3). The same applies for the calculated CF values – the highest CF for plants in Makirina Bay was calculated for Mn, with the highest value observed for G. lubrica (Table 4).

Table 3. Biota-sediment accumulation factor (BSAF) values in biota (flora and fauna) of Makirina Bay.

Table 4. CF values (CF × 103) in biota (flora and fauna) of Makirina Bay.

Concentrations of PTE in animal samples

The PTE contents in the exoskeletons of P. turbinatus decreased in order Cr > Ni > Mn > Zn > Cu > Co > Mo > Pb > Cd > As, while in its soft tissues the ordering was Cu > Zn > Cr > As > Mn > Ni > Mo = Pb > Co > Cd (Table 2). The concentrations of PTE in soft tissues were higher than those in exoskeletons (Table 2).

The PTE concentrations in C. aestuarii soft tissues were ordered in the following sequence: Cu > As > Mn > Zn > Cr > Ni > Pb > Co > Mo > Cd, while in its shells the ordering was Mn > Cu > Zn > As > Cr > Ni > Pb > Co > Mo > Cd (Table 2). The concentrations of all the PTE analysed are higher in C. aestuarii soft tissues (Table 2).

The contents of the majority of the PTE were greater in C. aestuarii than their respective concentrations in P. turbinatus.

The calculated BSAF and CF for As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb and Zn in P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The highest BSAF in P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii were observed for Cu, As, Zn and Cd, showing their tendency to accumulate those PTE to a similar extent to the PTE concentrations in sediments. According to the calculated BSAF values, P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii soft tissues can be classified as microconcentrators of Cd and Zn and macroconcentrators of As and Cu. The littoral crab C. aestuarii also accumulated PTE in its shells, i.e. As (as a macroconcentrator) and Cu (as a microconcentrator).

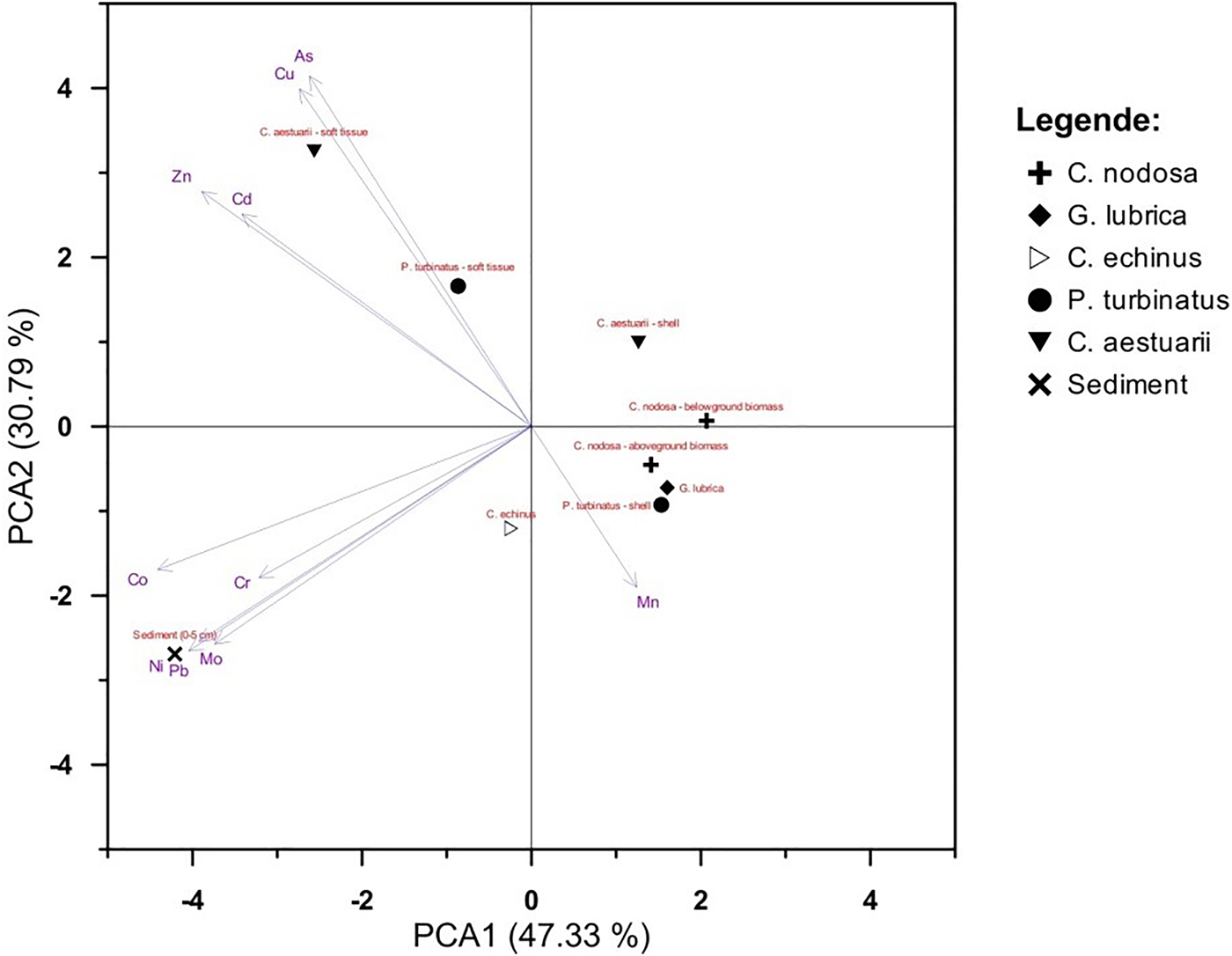

PCA

The PCA analyses yielded diagrams showing the main pattern of variation in PTE concentrations as accounted for by different biological tissues (Figure 2). The first two PCs accounted for 78.12% of the total variance in the dataset (Figure 2). From these results the following conclusions can be drawn: (i) soft tissues of P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii have higher As and Cu levels than other species and (ii) sediments are associated with high Cr, Co, Ni, Pb and Mo levels. The first PC explains 47.33% of the total variance and exhibits two groups with negative loadings. The highly negative loadings reveal an association among Cd, Co, Cr, Mo, Ni, Pb and Zn, suggesting their common, most probably terrigenous origin. Another group of PTE (As and Cu) also has negative but not high loadings, meaning that those PTE are only partly associated with terrigenous sources. In the first component, Mn is positively loaded. The second PC represents 30.79% of the total variance. As and Cu have similar positive loadings, highlighting their common origin.

Fig. 2. PCA diagram for overall dataset.

Stable isotope composition

The δ 15N values in the particulate organic matter (POM) and C. nodosa, C. echinus and C. aestuarii tissues from Makirina Bay ranged from 3.7 to 7.4‰ (Table 5). The lowest δ 15N values were estimated in POM, C. nodosa and C. echinus tissues, while the highest were obtained for tissues of the littoral crab C. aestuarii.

Table 5. Stable isotope values (δ15N) in biota (flora and fauna) of Makirina Bay.

DISCUSSION

Concentrations of PTE in seawater samples

The data obtained from seawater analyses should be interpreted carefully, because of high variability of PTE contents in seawater (Conti & Cecchetti, Reference Conti and Cecchetti2003).

The PTE contents in seawater of Makirina Bay are similar to those in marine sediments; as reported in our previous studies (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Rogan Šmuc, Lojen, Kniewald, Matešić, Lambaša Belak and Dolenec2014, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Lojen, Lambaša Belak, Kniewald and Rogan Šmucb), the concentrations in surficial (0–5 cm) sediments are (in mg kg−1): 14.47 (As), 0.27 (Cd), 7.05 (Co), 82.1 (Cr), 27.64 (Cu), 200 (Mn), 13.82 (Mo), 26.51 (Ni), 23.74 (Pb) and 47.67 (Zn), and decrease in the order: Mn > Cr > Zn > Cu > Ni > Pb > As > Mo > Co > Cd (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Rogan Šmuc, Lojen, Kniewald, Matešić, Lambaša Belak and Dolenec2014, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Lojen, Lambaša Belak, Kniewald and Rogan Šmucb). Only the concentrations of chromium (Cr) stand out – the concentrations of Cr are very high in the sediments, whereas in the seawater they are below the DL. This is due to the nature of Cr, as it is very quickly removed from seawater, mainly because of its adsorption tendency on iron oxides and/or complexation with organic matter (Oana, Reference Oana2006). The content of organic carbon in the sediment is very high (5 wt.%) and it is mainly related to the accumulation of organic material associated with the decay of seagrasses and macroalgae, which are very abundant in Makirina Bay (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Rogan Šmuc, Lojen, Kniewald, Matešić, Lambaša Belak and Dolenec2014, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a, Reference Komar, Dolenec, Dolenec, Vrhovnik, Lojen, Lambaša Belak, Kniewald and Rogan Šmucb).

The PTE concentrations in Makirina Bay seawater were compared with the Criteria Continuous Concentration (CCC) and Criteria Maximum Concentration (CMC). CCC and CMC aim to assess the impact of long- and short-term pollution on aquatic organisms (US EPA, 1999). The results showed that Cu and Zn concentrations in Makirina Bay seawater exceeded the CCC and CMC values. This may be owing to surface run-off caused by the spring and autumn heavy rains typical for this area, which magnifies the PTE concentrations of seawater by washing down agricultural wastewater: Cu and Zn are commonly present PTE in fertilizers, which are widely used in agricultural activities (Bradl, Reference Bradl2005).

Concentrations of PTE in plant samples

Plants in polluted areas tend to have higher concentrations of PTE than in unpolluted areas, although the differences are not always significant (Nicolaidou & Nott, Reference Nicolaidou and Nott1998).

The concentrations of the majority of the PTE analysed in C. nodosa from Makirina Bay are higher in its above-ground biomass. This finding agrees with those of other studies (Catsiki & Panayotidis, Reference Catsiki and Panayotidis1993; Malea & Haritonidis, Reference Malea and Haritonidis1999; Llagostera et al., Reference Llagostera, Perez and Romero2011) and is associated with the higher metabolic activity of above-ground tissues (Catsiki & Panayotidis, Reference Catsiki and Panayotidis1993).

Algae represent the first link in the food chain (Jitar et al., Reference Jitar, Teodosiu, Oros, Plavan and Nicoara2015). The green algae were characterized by having higher proportions of Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn, while the red species had higher levels of As and Mn. As seen from our results, the concentrations of PTE in green and red algae were greater than their respective concentrations in seagrass tissues. Algae have significant reserves of polysaccharides, which bind PTE to form insoluble complexes (Khristoforova & Chernova, Reference Khristoforova and Chernova2005). In seagrasses, this percentage is lower, and therefore so is their ability to accumulate PTE (Khristoforova & Chernova, Reference Khristoforova and Chernova2005).

The concentrations of PTE in the plant samples were compared with the PTE concentrations in the sediments. The results showed that the sediments concentrated more PTE, with the exception of Mn, than the analysed biota. Similar findings have also been made by other authors (Nicolaidou & Nott, Reference Nicolaidou and Nott1998; Malea & Haritonidis, Reference Malea and Haritonidis1999). Mn is a redox-sensitive PTE – it can be released from sediments to the overlying seawater under reducing conditions, and accumulate in the leaves of seagrasses (Nicolaidou & Nott, Reference Nicolaidou and Nott1998; Malea & Haritonidis, Reference Malea and Haritonidis1999). In our previous study (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a), the results of Eh measurement showed a highly reductive sedimentary environment at the sediment-seawater interface, associated with the decay of sedimentary organic matter (Komar et al., Reference Komar, Dolenec, Lambaša Belak, Matešić, Lojen, Kniewald, Vrhovnik, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2015a).

The highest BSAF and CF for plant species in Makirina Bay were observed for Mn. Manganese in an aquatic environment can be considerably bioconcentrated in aquatic organisms at lower trophic levels (WHO, 2004). In general, lower organisms such as algae have larger CF than higher organisms (WHO, 2004). Mn plays an essential role in the bodies of hydrobionts, but above a certain concentration this PTE has a toxic effect on hydroecosystems (Atanasov et al., Reference Atanasov, Valkova, Kostadinova, Petkov, Yablanski, Valkova and Dermendjieva2013).

The total PTE content in C. nodosa found in the present work matches with those found in the literature (Nicolaidou & Nott, Reference Nicolaidou and Nott1998; Li & Huang, Reference Li and Huang2012; El-Din & El-Sherif, Reference El-Din and El-Sherif2013; Malea & Kevrekidis, Reference Malea and Kevrekidis2013). For C. nodosa from Makirina Bay the mean PTE concentrations of Mn were higher than those reported in the existing literature from various geographic areas (Table 6). In contrast, the levels of some PTE detected in C. nodosa from Makirina Bay rank generally quite low compared with other Mediterranean areas (Table 6).

Table 6. Potentially toxic elements (PTE) concentrations (in μg g−1 dry wt) in seagrass C. nodosa – literature data from various geographic areas; empty spaces – information not accessible.

a Thessaloniki Gulf, Greece.

b Larymna, Greece.

c Egypt.

d Xincun Bay, Hainan Island, China.

Concentrations of PTE in animal samples

Aquatic molluscs are known to accumulate high concentrations of PTE in their tissues (Gundacker, Reference Gundacker2000; Ali & Bream Reference Ali and Bream2010). The PTE contents in gastropods may reflect the concentrations of PTE in surrounding seawater and sediments, and can be used as an indicator of the surrounding environment quality (Kumar Gupta & Singh, Reference Kumar Gupta and Singh2011; Yap & Cheng, Reference Yap and Cheng2013).

The concentrations of PTE in soft tissues of animals were generally higher than those in shells. The shell and soft tissues of the mussel usually differ in their chemical composition (Ravera et al., Reference Ravera, Beone, Trincherini and Riccardi2007). It is generally known that the animals’ soft tissues accumulate higher PTE concentrations than the exoskeleton (Cravo et al., Reference Cravo, Bebianno and Foster2004).

The concentrations of PTE are higher in C. aestuarii, as a result of the position it occupies in the food chain. The only exceptions are Cr and Ni, with higher concentrations in the gastropod P. turbinatus.

The calculated BSAF values were highest for As, Cd, Cu and Zn. Cu and Zn are essential PTE and are important in the cell metabolism, growth and survival of most animals, including molluscs and crustaceans (Jakimska et al., Reference Jakimska, Konieczka, Skóra and Namieśnik2011; Duysak & Ersoy, Reference Duysak and Ersoy2014). Marine gastropods and crustaceans normally store Cu and use it in the synthesis of a blood pigment, i.e. haemocyanin (Jakimska et al., Reference Jakimska, Konieczka, Skóra and Namieśnik2011; Yap & Cheng, Reference Yap and Cheng2013). Cu and Zn are parts of metalloenzymes, enzymes and respiratory pigments (Jakimska et al., Reference Jakimska, Konieczka, Skóra and Namieśnik2011; Yap & Cheng, Reference Yap and Cheng2013). Hence, the accumulation of Cu and Zn in the soft tissues of P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii can be attributed to their essentiality.

It is generally recognized that marine organisms contain much higher concentrations of As and Cd than freshwater and terrestrial species (Maher & Butler, Reference Maher and Butler1988; Avelar et al., Reference Avelar, Mantelatto, Tomazelli, Silva, Shuhama and Lopes2000; Ventura-Lima et al., Reference Ventura-Lima, Fattorini, Notti, Monserrat, Regoli, Gosselin and Fancher2009; Ponnusamy et al., Reference Ponnusamy, Sivaperumal, Suresh, Arularasan, Munilkumar and Pal2014). Cd is actively accumulated by marine organisms, particularly by molluscs, and some species of molluscs can accumulate large quantities of Cd from contaminated environments with no apparent damage; this is a well known detoxification strategy of marine invertebrates which involves the binding of some PTE, including Cd, to so-called metallothioneins, having a protective effect against the toxicity of Cd and other PTE (Engel & Fowler, Reference Engel and Fowler1979; Bustamante et al., Reference Bustamante, Cosson, Gallien, Caurant and Miramand2002; Kumar Gupta & Singh, Reference Kumar Gupta and Singh2011). In aquatic environments, inorganic As dominates in sediments and seawater, while the organisms generally accumulate As as organic non-toxic compounds (Neff, Reference Neff and Neff2002; Ventura-Lima et al., Reference Ventura-Lima, Fattorini, Notti, Monserrat, Regoli, Gosselin and Fancher2009). Organic non-toxic As represents up to 90% of the total content in the tissues of several aquatic organisms (Neff, Reference Neff and Neff2002; Ventura-Lima et al., Reference Ventura-Lima, Fattorini, Notti, Monserrat, Regoli, Gosselin and Fancher2009).

Compared with uncontaminated sites in Mediterranean areas, where the mean concentrations of Cd, Cu and Zn in P. turbinatus soft tissues were (in μg g−1 dry wt): 1.44, 10.9 and 31 (Favignana Island, Sicily, Italy) and 1.09, 20.18 and 55.4 (Linosa Island, Sicily, Italy), respectively (Campanella et al., Reference Campanella, Conti, Cubadda and Sucapane2001; Conti et al., Reference Conti, Bocca, Iacobucci, Finoia, Mecozzi, Pino and Alimonti2010), significantly higher concentrations of Cu occur in P. turbinatus from Makirina Bay. This could be a consequence of the leaching of Cu from agricultural land by surface runoff during spring, which increases the PTE content in the coastal ecosystem.

Nitrogen stable isotope composition

Stable nitrogen isotopes have been widely used to differentiate the natural and anthropogenic nitrogen sources in the environment; POM, benthic, benthic-feeding animals and all other organisms from waste-impacted areas, have shown different δ 15N values from those at unaffected sites (Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Vokal and Dolenec2005, Reference Dolenec, Lojen, Lambaša and Dolenec2006, Reference Dolenec, Žvab, Mihelčić, Lambaša Belak, Lojen, Kniewald, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2011).

POM, C. nodosa and C. echinus represent the first trophic level and thus exhibit the lowest δ 15N values. POM is generally a mix of detrital material of marine and terrestrial origin, zoo- and phytoplankton and particulate effluents from various sources (Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Žvab, Mihelčić, Lambaša Belak, Lojen, Kniewald, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2011). POM in the seawater of Makirina Bay (Table 5) exhibits similar δ 15N values to POM from pristine offshore locations in the central Adriatic Sea (Reef Flat Lumbarda), i.e. up to 3.2‰, and is subject only to natural seasonal variability (Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Žvab, Mihelčić, Lambaša Belak, Lojen, Kniewald, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2011). The δ 15N values of POM in the seawater of Pirovac Bay, with a history of direct inputs of anthropogenic sewage wastes, tend to have more positive δ 15N values, i.e. 6.1–6.7‰ (Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Žvab, Mihelčić, Lambaša Belak, Lojen, Kniewald, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2011).

In seagrasses, the δ 15N values normally vary from −2 to +12.3‰, but the most frequently recorded values are 0–8‰, depending on the seagrass ecosystem (Lepoint et al., Reference Lepoint, Dauby and Gobert2004 and references therein). δ 15N values are associated with inorganic N incorporation by seagrasses and with sediment and column-water geochemistry (Lepoint et al., Reference Lepoint, Dauby and Gobert2004 and references therein). The mean δ 15N of the seagrasses (Posidonia oceanica) at the unaffected reference site in the central Adriatic (Reef Flat Lumbarda) was 2.5 ± 0.4‰ (Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Lojen, Lambaša and Dolenec2006), whereas near Pirovac Bay it was between 4.2 ± 0.4 and 4.7 ± 0.3‰ (Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Lojen, Lambaša and Dolenec2006).

The highest δ 15N values in Makirina Bay were observed in the littoral crab C. aestuarii (Table 5). δ 15N values generally increase with trophic position, but 15N enrichment is changeable – it varies between animal groups, depending upon the availability of food and the age of the organisms, or is diet-related (Fry, Reference Fry1988; McCutchan et al., Reference McCutchan, Lewis, Kendall and MacGrath2003; Lepoint et al., Reference Lepoint, Dauby and Gobert2004; Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Žvab, Mihelčić, Lambaša Belak, Lojen, Kniewald, Dolenec and Rogan Šmuc2011; Pereira Majer et al., Reference Pereira Majer, Varella Petti, Navajas Corbisier, Portella Ribeiro, Sawamura Theophilo, de Lima Ferreira and Lopes Figueira2014). Additional stable nitrogen isotope composition of marine animals is also season-dependent; the δ 15N values of Arca noae muscle tissue on the southside of Pašman Island (central Adriatic sea) ranged from 4.5–6.7‰, and were highest in the spring (May), and the lowest in the winter (January) (Župan et al., Reference Župan, Peharda, Dolenec, Dolenec, Žvab Rožič, Lojen, Ezgeta-Balić and Arapov2014). Seasonal variability in the δ15N of the POM and marine organisms in affected areas is generally smaller than at unaffected sites due to the inputs of effluents with more or less constant δ15N values (Lojen et al., Reference Lojen, Spanier, Tsemel, Katz, Eden and Angel2005; Dolenec et al., Reference Dolenec, Lojen, Kniewald, Dolenec and Rogan2007).

The low δ 15N values in Makirina Bay indicate an environment not affected by anthropogenic discharges – this is also reflected in the Makirina Bay organisms.

CONCLUSIONS

The five examined species in Makirina Bay, C. nodosa, C. echinus, G. lubrica, P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii, behaved differently as bioindicators of PTE. The BSAF and CF values varied among these species, and moreover, within the same species, differences between shells and soft tissues were detected. During the present study, C. nodosa, C. echinus and G. lubrica proved to be the strongest accumulators of Mn, while P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii confirmed their high capacity to accumulate As, Cd, Cu and Zn.

An organism will reflect the degree of environmental contamination if it has the ability to take up PTE proportionally to the pollution in the living environment. The soft tissues of P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii could be considered appropriate for the evaluation of the As, Cd, Cu and Zn concentrations, since the PTE values in these tissues proved to exceed the environmental concentrations, which indicates a bioaccumulation process. The current results show the capability of these species to act as bioaccumulators. Since these benthic species are known to inhabit a wide area for investigation, thus allowing comparison between areas, they can be considered as good ecological indicators, being sensitive to certain chemical stresses, the responses to which are measurable (sensu Noss, Reference Noss1990). The recent MSFD requires that European Member States develop monitoring programmes for the assessment of the GEnS at least every 6 years. According to the requirements of the MSFD, C. nodosa, C. echinus, G. lubrica, P. turbinatus and C. aestuarii could be among the biological indicators to be taken into consideration and to be used for regular monitoring programmes along Adriatic coasts and other Mediterranean areas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Very many thanks go to Mr Boris Paškvalin, director of BTP, d.d., Betina (Croatia).

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This research was financially supported by the Geoexp, d.o.o. – Company for Scientific Research and Developement in the Field of Geology, Geochemistry and Environmental Protection (Tržič, Slovenia) and ARRS Slovenia (contract number 1000-11-310206).